“Murder Most Foul” was released on March 27, 2020, during the dark days of lockdown. A 17-minute song about the Kennedy assassination may not seem the best antidote for the Covid blues. But in his message accompanying the release, Dylan framed the song as a gift:

Enough listeners opened that gift to make “Murder Most Foul” Dylan’s first song to hit No. 1 on the Billboard chart.

Why put out a song about the Kennedy assassination almost sixty years after the fact? As Dylan surveyed the contemporary landscape of disease, despair, political strife, social inequality, and rampant corruption, he must have sensed parallels with the tumultuous 1960s. These forces gained a definitive upper hand in Dallas on November 22, 1963. It’s as if a seal of the apocalypse was broken and a curse spread out across the blighted land.

At the beginning of Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex, Thebes is a wasteland. King Oedipus consults the Oracle at Delphi to find out what is wrong and what might set it right. Creon returns with revelations from Apollo:

CREON: The god commands us to expel from the land of Thebes

An old defilement we are sheltering.

It is a deathly thing, beyond cure;

We must not let it feed upon us longer.

OEDIPUS: What defilement? How shall we rid ourselves of it?

CREON: By exile or death, blood for blood. It was

Murder that brought the plague-wind on the city. (Sophocles 9)

The previous King Laïos was murdered, and Apollo decrees that whoever was responsible must be exposed and punished in order to lift the curse. Likewise, Dylan approaches “Murder Most Foul” as an American bard initiating an overdue reckoning for the murder of a king.

Song of Innocence & Experience

The first time I listened to “Murder Most Foul,” I was underwhelmed by the early verses. My students felt the same. Last fall, on the anniversary of the assassination, I played the first five minutes to my Dylan class and asked them what they thought. Roz Thompson’s hand shot up. “Is it possible to lose your Nobel Prize for writing such bad poetry?” Ouch! Maybe I should have played them the final 6 ½ minutes of the song instead, by far my favorite, where Dylan finally and completely wins me over with his ticker-tape thought associations and spellbinding dream consciousness. We’ll get to that final section later, but first let’s consider what Dylan is doing with the early verses.

The accompanying message said, “This is an unreleased song we recorded a while back that you might find interesting.” Dylan writing about the Kennedy assassination? Oh, we’re interested, Bob! But as I was first listening, I was thinking, “Yeah, I can hear why he hesitated to release this.” The lyrics in the opening section initially struck me as amateurish and unfocused, below the standards of the most celebrated and sophisticated songwriter of his era.

My friend Andrew Muir notes these shortcomings, too, but he offers an insightful defense of this writing style. In a new afterword to the 2020 updated edition of The True Performing of It, Andy acknowledges the “recurring, intentional banality” and “wince-inducing rhymes and double entendres” of “Murder Most Foul” (363). Rather than simply dismissing this as bad poetry, however, he associates it with William Blake’s Songs of Innocence.

Dylan invokes Blake directly in the album’s opening song, “I Contain Multitudes,” and Andy persuasively argues that he returns to the Romantic poet as a model for the album closer. Blake imitated childish verse as the vehicle best suited for depicting innocence. Andy thinks Dylan is up to the same thing in “Murder Most Foul”: “Perhaps, then, we are being presented with an approach that mixes that of the Blake of ‘Songs’ and what we have come to see as a recognisable late style for artists from all fields from Shakespeare to Beethoven. That is, a viewing of complexity through the prism of seeming primitivism, or simplicity, carelessness even” (364).

Dylan views the Kennedy assassination as a pivotal moment in American history, and he elevates it to the level of national myth. The catastrophe represents a fall from grace and the end of childish innocence. Dylan regards the killing in archetypal terms as a primal crime so diabolical that it splintered reality. This foul murder shook our faith in sacred principles that America once championed but has since routinely betrayed. (As we’ll soon see, the U.S. government was already routinely betraying those principles long before 1963, but that’s history—this is myth.) Dylan reinforces these views stylistically in “Murder Most Foul” through disjointed verses written from the juvenile perspective of a damaged child. After blissful innocence comes traumatic experience.

In his 1988 interview with Rolling Stone, Don DeLillo was asked about the lingering impact of the Kennedy assassination. His response resonates strongly with “Murder Most Foul”:

As the years have flowed away from that point, I think we’ve all come to feel that what’s been missing over these past twenty-five years is a sense of manageable reality. Much of that feeling can be traced to that one moment in Dallas. We seem much more aware of elements like randomness and ambiguity and chaos since then. (DeCurtis 56, emphasis added)

“Murder Most Foul” reflects the randomness, ambiguity, and chaos of the Kennedy assassination. I’m tempted to call the song a murder ballad expanded to the epic scale, except that, after the first verse, Dylan abandons the traditional linear narrative of the ballad form. What follows is not straightforward storytelling with a beginning, middle, and end; and the moral of the tale is anyone’s guess. It’s not quite historical chronicle either: if there are lessons taught by these events, we still haven’t properly learned them. Dylan is no history professor. He approaches the subject as a purveyor and consumer of pop culture. The song is fragmentary because it is pieced together from shards after the shattering events in Dallas, November 1963. Randomness, ambiguity, and chaos serve as both content and form in “Murder Most Foul.”

Conspiracy Theories & the Zapruder Film

Dylan weaves the tangled web of “Murder Most Foul” from various conspiracy theories about the Kennedy assassination. The first verse depicts the murder as a coup d’état. Kennedy’s trip to Dallas is described as “Being led to the slaughter like a sacrificial lamb.” The singer conspicuously uses plural pronouns to refer to the killers, suggesting that Oswald was not the lone assassin:

Then they blew off his head when he was still in the car

Shot down like a dog in broad daylight

’Twas a matter of timing and the timing was right

You got unpaid debts and we’ve come to collect

We’re gon’ kill you with hatred and without any respect

We’ll mock you and shock you, we’ll grin in your face

We’ve already got someone here to take your place

The implication is that shadowy forces within the government, intelligence services, and/or military-industrial complex conspired to murder the president and replace him with an executive more amenable to their agendas.

Does Dylan actually believe that a successful coup was executed in America in November 1963? Possibly, but who really knows? What we can say is that “Murder Most Foul” is narrated by someone who believes it. Furthermore, the song was released into a climate that was again seething with conspiracy theories.

The consequences of the Kennedy assassination extend well beyond politics. “Murder Most Foul” portrays the bloodletting in Dallas as an assault on reality itself, a crime of metaphysical and theological proportions. “What is the truth and where did it go / Ask Oswald and Ruby – they oughta know.” The singer describes Dealey Plaza as “the place where Faith, Hope and Charity died.” Someone tells him, “The Age of the Anti-Christ has just only begun.” He agrees: “I said the soul of a nation been torn away / It’s beginning to go down into a slow decay / And that it’s thirty-six hours past Judgment Day.” These doomsday prophecies aren’t ripped from the headlines so much as ripped from the Book of Revelation.

And then there’s the Zapruder film:

Zapruder’s film, I’ve seen that before

Seen it thirty-three times, maybe more

It’s vile and deceitful – it’s cruel and it’s mean

Ugliest thing that you ever have seen

You don’t have to read dozens of books or troll the dark web to familiarize yourself with the alleged conspiracy to kill Kennedy. You can get up to speed in less than thirty seconds: just watch the Zapruder film.

The best visual evidence of the Kennedy assassination was accidentally captured by a bystander with his home-movie camera. Still frames of the footage were first published in Life magazine only a week after the murder, and the film became a centerpiece of Warren Commission’s postmortem investigation.

This simple footage shot by a guileless amateur with no artistic technique or political agenda is the cinematic equivalent of Blake’s innocent style in Songs of Innocence and Dylan’s similar technique in “Murder Most Foul.” With apologies to Citizen Kane, the Zapruder film is the most important American film of the 20th century.

Abraham Zapruder was a Jewish immigrant from the Russian empire (in modern-day Ukraine) who fled hardship and persecution to seek fresh opportunity in America, just like Dylan’s own ancestors. Abe (same name as Dylan’s dad) first settled in Brooklyn and eventually relocated to Dallas. In 1963 he ran a children’s clothing line, Jennifer Juniors, with offices located across the street from the Texas School Book Depository.

Zapruder was haunted by what he witnessed in Dealey Plaza. At one point during his testimony to the Warren Commission, he was overcome with emotion and broke down in tears. Asked about the film, he told the interviewer, “I have seen it so many times. In fact, I used to have nightmares. The thing would come every night—I wake up and see this.” Dylan describes JFK as “Shot down like a dog in broad daylight,” and I suspect that vivid description comes from Zapruder’s testimony:

Well, I am ashamed of myself. I didn’t know I was going to break down and for a man to—but it was a tragic thing, and when you started asking me that, and I saw the thing all over again, and it was an awful thing—I know very few people who had seen it like that—it was an awful thing and I loved the President, and to see that happen before my eyes—his head just opened up and shot down like a dog—it leaves a very, very, deep sentimental impression with you; it’s terrible.

The Zapruder film was kept from the public for years, though bootleg copies leaked out. Now all it takes a quick internet search to view the video. Personally, I didn’t see the footage until Oliver Stone showed it repeatedly in his incendiary movie JFK. “Back and to the left. Back and to the left. Back and to the left.” Hit the play button, then brace yourself for the blow:

I was stunned and disturbed when I saw the Zapruder film, but also livid. It’s hard to watch that footage and not instinctively conclude that the fatal headshot was delivered from the front, in the vicinity of the grassy knoll on Dealey Plaza, not from behind, in the direction of the Texas School Book Depository. More than one shooter would mean the Warren Report got it wrong. More than one shooter would mean there was a conspiracy. I share DeLillo’s gut reaction to the Zapruder film:

There’s a bolt of revelation. Because the head shot is the most direct kind of statement that the lethal bullet was fired from the front. Whatever the physical possibilities concerning impact and reflex, you look at this thing and wonder what’s going on. Are you seeing some distortion inherent in the film medium, or in your own perception of things? Are you the willing victim of some enormous lie of the state—a lie, a wish, a dream? Or, did the shot simply come from the front, as every cell in your body tells you it did? (Begley 104-5)

Every frame has been subjected to endless analysis and debate. And yet there remains profound disagreement about what we see when we look at the Zapruder film. In DeLillo’s 1993 interview with The Paris Review, Adam Begley noted, “It’s one of the great ironies that, despite the existence of the film, we don’t know what happened.” DeLillo agreed: “We’re still in the dark. What we finally have are patches and shadows. It’s still a mystery. There’s still an element of dream-terror” (Begley 104).

Dylan describes the Zapruder film as “vile and deceitful.” The vileness is obvious, but in what sense is it deceitful? It seems to expose a huge lie—but which lie?

Someone other than Oswald killed Kennedy. There was a sinister conspiracy to assassinate the President of the United States, followed by a vast coverup to conceal the plot with impunity. The killers got away with an enormous history-changing crime and are in effect still getting away with it. The conspirators seized control of the country and the post-1963 world order, which is all built upon a monstrous lie.

Our eyes deceive us. Ballistic science can explain the movement of Kennedy’s head in response to the fatal head-shot. The Warren Commission got it right: Oswald acted alone. There was no deep-state conspiracy—it’s our own faulty perception and flawed interpretation of reality that betrays us.

What is pinned wriggling to the celluloid is unresolved mystery and epistemological crisis. In Shooting Kennedy: JFK and the Culture of Images, David Lubin considers the Zapruder film as an object lesson in the Heisenberg uncertainty principle, which holds that the act of observation displaces or distorts the very thing being observed. As Lubin puts it,

Optically enhanced, digitized, computerized, holographed, and even examined by scientists at Los Alamos, the Zapruder film repeatedly fails to divulge the truth. Or, to the contrary, divulges so many “objective” truths, so many “indisputable” proofs, so many “authoritative” interpretations of who fired the bullets and from where that anyone who is not a die-hard believer of one particular theory or another faces an array of conclusions so bewildering that choosing among them seems all but impossible. Richard Stolley, the shrewd journalist who bought Zapruder’s home movie for Life, said of the film clip: “Depending on your point of view, it proves almost anything you want it to prove.” (172-73)

Lubin effectively sums it up this way: “the Zapruder film proved to be less a Rosetta stone than a Rorschach test—less an objective key to reality than an ink blot lending itself to infinitely variable subjective interpretation” (173-74). “Murder Most Foul” similarly drifts unmoored through randomness, ambiguity, and chaos, like a musical adaptation of the Zapruder film.

Radio Dreams

Dylan makes fascinating use of radio in “Murder Most Foul.” His first oblique reference comes at the end of the first verse: “Wolfman, oh wolfman, oh wolfman, howl / Rub a dub dub – it’s murder most foul.” Although there are multiple wolfmen he could have in mind, he spells it out in the long final section of the song: “Wolfman Jack, he’s speaking in tongues / He’s going on and on at the top of his lungs / Play me a song, Mr. Wolfman Jack.” Dylan comes close to self-allusion: “Hey! Mr. Tambourine Man, play a song for me / In the jingle jangle morning I’ll come followin’ you.” Except in “Murder Most Foul,” the singer and listener aren’t headed into the new morning of hope but rather into the dark night of the American soul.

Dylan told Douglas Brinkley that he never met the legendary radio disc jockey, but Wolfman Jack nevertheless made a strong impression on him: “His voice was very caustic. Unusual in a unique way. Raw and grating. But every disc jockey back then had their own personality, and that was his. His whole being was wrapped up in the songs that he played on the radio. I think he had the perfect voice for the Industrial Age” (587). Dylan amplified these same qualities as a DJ on his iconoclastic Theme Time Radio Hour (2006-2009).

I wonder if Dylan is aware that fans sometimes refer to his own voice as “The Wolfman.” In a piece cleverly titled “Play Me a Song, Mr. Wolfman Bob,” Ray Padgett writes: “The Wolfman is fairly self-explanatory. You could also call it The Cookie Monster or The Tom Waits Impersonator. Those vocals on Tempest and Christmas in the Heart? Classic Wolfman. Singing the Sinatra songs smoothed his voice back out, thankfully, but he was in that guttural-growl mode for a while before that.”

Wolfman Jack was born Robert Weston Smith in 1938. Bobby Smith grew up in Brooklyn listening to the same music as Bobby Zimmerman in Hibbing. Bob Smith apprenticed his way through various DJ jobs. His big break came when he moved south of the U.S./Mexico border to the 250,000-watt XERF, the most powerful commercial radio signal in the world. As far as I can tell, Smith debuted his Wolfman Jack persona on air in December 1963, which would mean that the timeline in “Murder Most Foul” is a bit off. But again, Dylan isn’t fact-checking history so much as burnishing myths.

In his biography Have Mercy! Confessions of the Original Rock ’n’ Roll Animal, Wolfman Jack explicitly compares his metamorphosis with Dylan’s self-mythology: “I became my own invention: my invention became me. Just like Samuel Langhorne Clemens gradually became Mark Twain or Robert Zimmerman became Bob Dylan” (209).

Interesting as the links are between the two Bobs, I’m more intrigued by the DJ’s artistic function within “Murder Most Foul.” Dylan is surely attracted to the werewolf figure, a liminal shape-changer who switches back and forth between man and beast. The song also creates a doppelganger dynamic between two Jacks, the President and the Wolfman.

The final section consists largely of requests for Wolfman Jack. Who is making these requests? According to Greil Marcus, “you’re listening in to John F. Kennedy’s brain after the president-for-five-more-seconds has first been hit but before he’s killed, arguing with his assassins as if there’s still time to talk them out of it” (227). That’s one valid interpretation, but there are others.

Andrew Muir suggests multiples sources for the various “disembodied voices” haunting “Murder Most Foul”: “These emanate from the radio, from the ghost of the President, from the soul of the nation and even from a ‘werewolf’ figure in the spirit of DJ Wolfman Jack who is called upon to play the song choices requested by an amalgam of Kennedy’s ghost, America’s past, Dylan’s audience and Dylan himself” (368).

In her excellent Definitely Dylan podcast on “Murder Most Foul,” posted only twelve days after the single’s release, my good friend Laura Tenschert recognizes the central importance of the DJ: “Wolfman Jack really is a pivotal figure here. He is the figure that really ties all the pop cultural references together. He’s the one who is called on to play all the artists and songs that the singer requests in a long list that runs through verse four and five until the end of the song.” She also compiled a Spotify playlist with over eighty songs referenced in “Murder Most Foul.”

Laura’s understanding of Wolfman Jack, as the figure who ties the song together, tracks with George Lucas’s memorable use of the DJ in his film American Graffiti. An early direction in the script establishes his pivotal role:

In the background, we hear the Wolfman howling with the music. The record ends and a barrage of humor begins from Wolfman Jack. The Wolfman is an unseen companion to all the kids. Witty and knowledgeable about the trivia that counts, he’s their best friend, confidant, and guardian angel. (3)

That’s essentially the role Dylan scripts for him as well in “Murder Most Foul.” As Wolfman Jack put it in his biography,

His [George Lucas’s] idea was to have a disc jockey who is a shadowy, mysterious figure. Because he came through all their car radios, spouting patter and being kind of the unseen life of the party, the DJ was involved with all the characters in the story. So he wanted me to be the needle and thread that sewed everything together. (222)

Dating back to his youth in Minnesota, Dylan imbues radio with mystical qualities. The signal is transmitted in waves, coming from everywhere and nowhere, invisible like the air we breathe. The music moves through the radio and through the listener. In Sam Shepard’s True Dylan (billed as “a one-act play, as it really happened one afternoon in California”), Sam asks Bob if he dreamt about music growing up. Bob muses on the intimate relationship of radio and dreams:

Sometimes I’d even be there in the dreams myself. Radio-station dreams. You know how, when you’re a kid, you stay up late in bed, listening to the radio, and you sort of dream off the radio into sleep. That’s how you used to fall asleep. That’s when disc jockeys played whatever they felt like.

Bob adds, “Just sorta dream off into the radio. Like you were inside the radio kinda.” You are the radio and the radio is you: it’s broadcasting your thoughts, desires, and dreams. This approach to radio, as a mind-merge with the listener and outlet for dream consciousness, provides the blueprint for the Wolfman Jack section of “Murder Most Foul.”

Laura Tenschert offers a Pentecostal interpretation of the line “Wolfman Jack, he’s speaking in tongues.” She explains:

Speaking in tongues is, for example in the Pentecostal Church, seen as receiving a message through the Holy Spirit. Perhaps this suggests that Wolfman Jack has access to a truth that is otherwise obscured. But ultimately, it isn’t Wolfman Jack himself who is speaking this truth and who needs to be heard. It is the songs that he has the power to play.

Laura tunes into a spiritual frequency for her reading of “Murder Most Foul.” Through the ritualistic litany of songs in the final section, she argues, “Dylan is showing us where the soul of America can still be found. The soul of America, he seems to be saying, can be found in art, in music, in movies, in plays—in culture old and new. This kind of makes me wonder if we could consider ‘Murder Most Foul’ as a sort of dark ‘American Pie’ of our times.” If November 22, 1963, is Dylan’s “day the music died,” then perhaps music can also be the pathway for resurrecting America and saving its soul.

Radio Nightmares

There may be a longing for spiritual redemption in “Murder Most Foul,” but the song also picks up sinister signals transmitted by dark forces—radio nightmares. Dylan drew positive inspiration from radio growing up. However, as a student of American history, he must also be aware how the masters of war have exploited radio as a tool for propaganda and as a weapon for regime change.

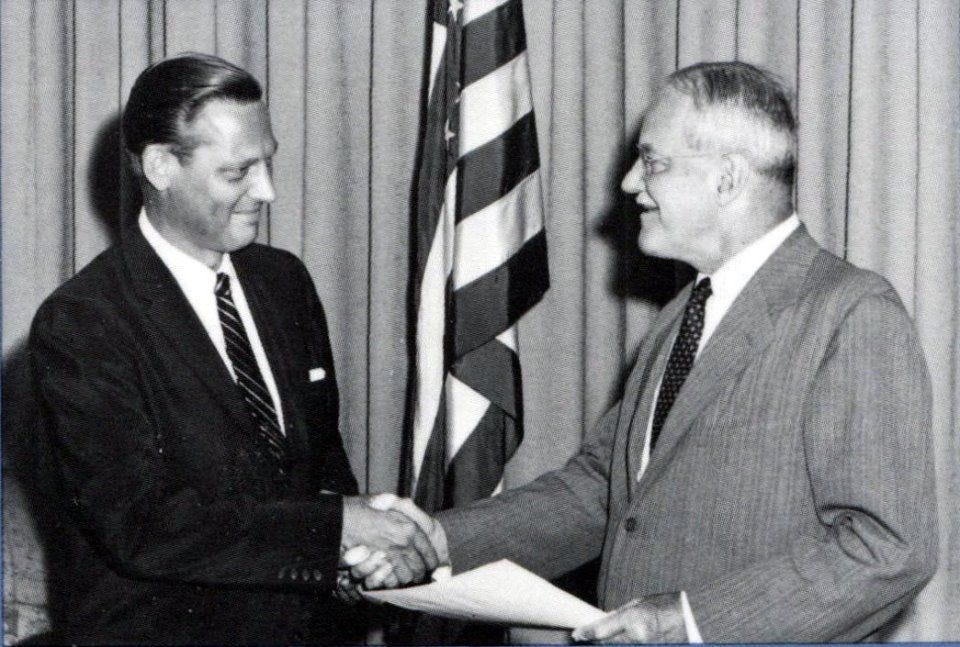

For instance, radio played a crucial part in the 1954 Guatemalan coup orchestrated by the CIA. When the democratically-elected President of Guatemala, Jacobo Árbenz, began implementing land reforms that threatened the interests of the United Fruit Company, corporate leaders appealed to President Eisenhower to intervene. Secretary of State John Foster Dulles and his brother, Director of Central Intelligence Allen Dulles, had both worked as lawyers for the United Fruit Company before entering government. The Dulles brothers collaborated with Eisenhower and the National Security Agency to devise a plan for overthrowing Árbenz.

The CIA set up a pirate radio station called “La Voz de la Liberación” [“Voice of Liberation”] to foment rebellion and engage in psychological warfare against the local population. David Atlee Phillips, a former actor, was hired to direct the station. [Phillips was later interrogated, but never charged, with involvement in the Kennedy assassination.]

Reading the history of the 1954 Guatemala coup is like watching Barry Levinson’s Wag the Dog or hearing stories about the panic caused by Orson Welles’s War of the Worlds. Phillips and three Guatemalan accomplices carefully scripted and broadcast an elaborate disinformation campaign out of their pirate radio station. They faked a widespread popular uprising, created fictional coverage supporting the rebellion, and pulled the performance off so convincingly that the Guatemalan people and even President Árbenz believed that a massive revolution was under way. Convinced he was under siege by thousands of rebels (there were never more than a few hundred), Árbenz resigned his office and fled Guatemala. The phantom broadcasts by “Voice of Liberation” played a vital role in overthrowing the government, turning fantasy into reality.

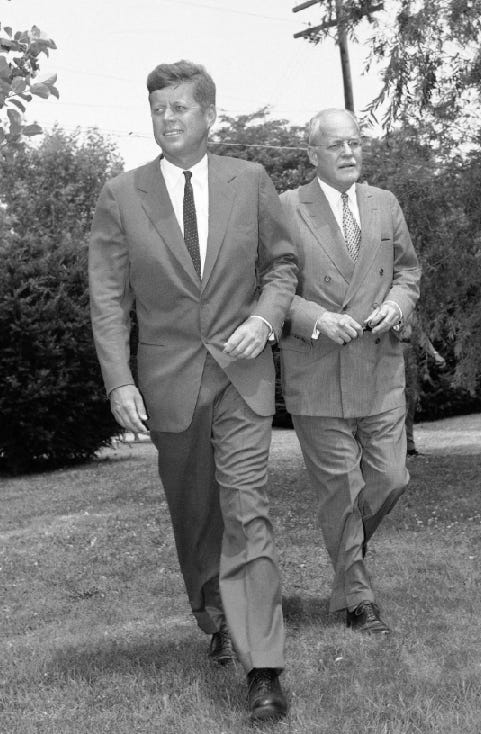

Emboldened by their success in Guatemala, the CIA employed the same techniques in an attempt to overthrow Castro’s regime in Cuba. The plan was set into motion during the final months of the Eisenhower administration and inherited by Kennedy. The CIA set up a pirate radio station called Radio Swan on Swan Island in Honduras. This station broadcast anti-Castro propaganda to the Cuban people, and it delivered coded messages to the rebel forces during the Bay of Pigs invasion. However, the attempted coup in Cuba was a total failure and public disgrace. As a result, President Kennedy fired Dulles as Director of Central Intelligence in November 1961. Two years later, President Johnson appointed Dulles to serve on the Warren Commission investigating JFK’s assassination.

The term “pirate radio” simply means operating a station without a license. Pirate radio broadcasts can be perfectly benign. Consider, for instance, Radio Caroline, one of the top rock stations in England in the 1960s. Dylan makes positive references to pirate radio in “Key West (Philosopher Pirate),” the song before “Murder Most Foul” on Rough and Rowdy Ways.

I’m searchin’ for love and inspiration

On that pirate radio station

It’s comin’ out of Luxembourg and Budapest

Radio signal clear as can be

I’m so deep in love I can hardly see

Down in the flatlands – way down in Key West

In this song, pirate radio is a catalyst for love and inspiration, not deceit and insurrection. But something happens between “Key West” and “Murder Most Foul.” The signals get crossed. Randomness, ambiguity, and chaos bleed into the transmission. Radio becomes deranged.

A character in DeLillo’s Libra recalls being stranded at the Bay of Pigs and listening to the senseless stream of coded messages coming from Radio Swan: “this gibberish had the sound of a mind unraveling” (127). That’s what I hear in “Murder Most Foul”—the sound of a mind unraveling. Radio can provide the soundtrack for the American dream, but it can also disseminate the diabolical babble of the American nightmare.

Hamlet

As you probably know by now, the title “Murder Most Foul” comes from Shakespeare’s tragedy Hamlet. Dylan isn’t the first artist to make this association. In Oliver Stone’s JFK, Jim Garrison (played by Kevin Costner) tells the jury, “We have all become Hamlets in our country—children of a slain father-leader whose killers still possess the throne. The ghost of John F. Kennedy confronts us with the secret murder at the heart of the American dream.”

Dylan compares the Kennedy assassination to Claudius murdering his brother King Hamlet to usurp his throne. The ghost of the slain king visits his son, Prince Hamlet, informing him about the murder and demanding revenge.

GHOST: List, list, O list,

If thou didst ever thy dear father love—

HAMLET: O God!

GHOST: —Revenge his foul and most unnatural murder!

HAMLET: Murder!

GHOST: Murder most foul—as in the best it is—

But this most foul, strange and unnatural. (1.5.22-28, emphasis added)

Let’s untangle this analogy. If JFK stands in for King Hamlet, then that makes LBJ the traitorous brother Claudius. The line “We’ve already got someone here to take your place” implies that the Vice President was in on the plot to kill and replace the President.

But then who is Hamlet in this analogy? You might guess that Dylan himself takes the place of Hamlet, but I don’t think so. The singer adopts multiple guises over the course of the song, sometimes speaking as an omniscient narrator, sometimes as a conspiracy theorist, sometimes as one of the conspirators, sometimes as dying Kennedy. Dylan functions more like Shakespeare, a dramatic wizard conjuring up these crimes through different voices and perspectives.

I think Hamlet’s role is filled by us, the song’s listeners. We are the ones haunted by the ghost of Kennedy. We are the ones exhorted to “list, list, o list” to the bloody tale of this “murder most foul.” We are the ones who must decide what, if anything, to do about it.

Pause to consider how strange the king’s murder is in Hamlet. According to the ghost, old Hamlet was napping in his orchard when Claudius snuck up with a vial of poison, “And in the porches of my ears did pour / The leperous distilment” (1.5.63-64). The echoes from the Garden of Eden are unmistakable: brother kills brother, like Cain killed Abel; and the dirty deed is accomplished by pouring poison in the victim’s ear, like the serpent wickedly whispering in Eve’s ear to disobey God.

Can the ghost be trusted? Is it telling the truth? Or does it have malicious intent? Let’s dig deeper into these critical questions about Hamlet because I think they pertain to “Murder Most Foul” as well.

When the watchmen first see the ghost, it disappears at dawn, suggesting that, like an evil creature, it flees from God’s holy light. When Hamlet encounters the ghost a few scenes later, he wonders if it is a divine spirit or a demon:

Angels and ministers of grace defend us!

Be thou a spirit of health or goblin damned,

Bring with thee airs from heaven or blasts from hell,

Be thy intents wicked or charitable,

Thou com’st in such a questionable shape

That I will speak to thee. (1.4.39-44)

The ghost beckons Hamlet for a private conversation, but his friends urge him to resist. They are convinced that this spirit is setting a trap. Horatio warns,

What if it tempt you toward the flood, my lord,

Or to the dreadful summit of the cliff

That beetles o’er his base into the sea,

And there assume some other horrible form

Which might deprive your sovereignty of reason

And draw you into madness? (1.4.69-74)

Horatio is afraid that the ghost is an agent of the devil who has come to drive Hamlet toward madness and death. And that’s exactly what ends up happening. Over the course of the next four acts, Hamlet gradually loses his mind and ultimately dies as a victim of poisoning. But maybe what really killed him was listening to the ghost in the first place, who was essentially pouring poison in his ear.

“Got blood in my eyes, got blood in my ear,” sings Dylan. We’ve got blood in our ears, too, from listening to “Murder Most Foul.”

The song’s final request is self-referential: “Play ‘Murder Most Foul.’” We reach the end of the 17-minute song, and the singer asks that we play it all over again. This circular repetition mirrors the psychodynamics of trauma. Since the Kennedy assassination has never been fully understood, it cannot be adequately processed into a stable narrative memory of the past. Whenever something triggers the old trauma, the event is reenacted in the present as if unfolding right now for the first time.

It’s worth noting that this repetition-compulsion isn’t just psychological, it’s performative. Long before modern psychology gave us clinical vocabulary to describe the circularity of traumatic experience, Shakespeare expressed it in the language of theater. As Prince Hamlet dies in his friend Horatio’s arms, he makes one last request:

If thou didst ever hold me in thy heart

Absent thee from felicity awhile

And in this harsh world draw thy breath in pain

To tell my story. (5.2.330-33)

Horatio does as his friend asks. When the victorious Fortinbras arrives at Elsinore Castle, Horatio charges him to

give order that these bodies

High on a stage be placed to view,

And let me speak to th’ yet unknowing world

How these things came about. (5.2.361-64)

Put them on stage and we’ll tell their story (again). Hamlet’s last request is to play Hamlet, just as Dylan’s last request is to play “Murder Most Foul.”

In the 2020 New York Times interview, Douglas Brinkley asked, “Was ‘Murder Most Foul’ written as a nostalgic eulogy for a long-lost time?” Dylan flatly rejected that characterization: “To me it’s not nostalgic. I don’t think of ‘Murder Most Foul’ as a glorification of the past or some kind of send-off to a lost age. It speaks to me in the moment.”

The randomness, ambiguity, and chaos surrounding the Kennedy assassination felt all too timely in 2020 amid the lunatic howls of another DJ—Donald John Trump, Mad King Donald. And just like in Hamlet, the poison that started in the ear and moved to the brain has seeped out into the nation at large. Something is rotten in the state of America. Add a novel coronavirus to the toxic mixture and suddenly the infection began spreading rapidly across the entire globe.

Dylan dispenses no cures for these ills, and personally I don’t hear much consolation in “Murder Most Foul.” But one of his enduring gifts as an artist is to make unexpected connections between disparate things that you wouldn’t have thought to put together. Like you, I was brooding on a lot of things during the early days of lockdown, but the Kennedy assassination wasn’t one of them. Not until March 27, 2020.

Ever since the release of “Murder Most Foul,” I’ve been fascinated by the links between the Kennedy assassination, Dylan’s art, and the troubled times of both the 1960s and 2020s. As has so often been the case, Dylan pointed me down paths of history, music, literature, and myth that I would never have explored without his prompting and guidance. It has been a journey through dark heat, but I hope you’ve found it illuminating. Call it appreciation, call it obsession, or call it repetition-compulsion, I can’t get enough of this ominous song.

Play it again, Bob. Play “Murder Most Foul.”

Works Cited

American Graffiti. Directed by George Lucas. Universal Pictures, 1973.

Begley, Adam. “The Art of Fiction CXXXV: Don DeLillo.” 1993. Conversations with Don DeLillo. Ed. Thomas DePietro. University of Mississippi Press, 2005, 86-108.

Blake, William. Songs of Innocence and of Experience. Project Gutenberg, https://www.gutenberg.org/files/1934/1934-h/1934-h.htm.

“Brief History of Radio Swan.” Cuban Information Archives. https://cuban-exile.com/doc_226-250/doc0241.html.

Brinkley, Douglas. “Bob Dylan Has a Lot on His Mind.” The New York Times (12 June 2020), https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/12/arts/music/bob-dylan-rough-and-rowdy-ways.html.

---. “Epilogue: Our Wells Are Deep.” Bob Dylan: Mixing Up the Medicine. Mark Davidson and Parker Fishel. Callaway, 2023, 583-88.

DeCurtis, Anthony. “‘An Outsider in This Society’: An Interview with Don DeLillo.” 1988. Conversations with Don DeLillo. Ed. Thomas DePietro. University of Mississippi Press, 2005, 52-74.

DeLillo, Don. Libra. New York: Penguin, 1988.

Dylan, Bob. Official Lyrics. The Official Bob Dylan Website.

https://www.bobdylan.com/.

JFK. Directed by Oliver Stone. Warner Brothers, 1991.

Lubin, David M. Shooting Kennedy: JFK and the Culture of Images. University of California Press, 2003.

Marcus, Greil. Folk Music: A Bob Dylan Biography in Seven Songs. Yale University Press, 2022.

Muir, Andrew. The True Performing of It: Bob Dylan & William Shakespeare, updated edition. Red Planet Books, 2020.

Padgett, Ray. “Play Me a Song, Mr. Wolfman Bob.” Flagging Down the Double E’s (21 November 2024),

.

Schlesinger, Stephen, and Stephen Kinzer. Bitter Fruit: The Story of the American Coup in Guatemala, revised and expanded edition. Harvard University Press, 2005.

Shakespeare, William. Hamlet. Second Quarto. Arden Shakespeare Third Series. Eds. Ann Thompson and Neil Taylor. Bloomsbury, 2006.

Shepard, Sam. True Dylan. Esquire (1 July 1987). https://classic.esquire.com/article/1987/7/1/true-dylan.

Sophocles. Oedipus Rex. Trans. Dudley Fitts and Robert Fitzgerald. The Oedipus Cycle. Harcourt, Brace & World, 1949.

Tenschert, Laura. “Bob Dylan’s ‘Murder Most Foul’: JFK, Conspiracy Theories, and the Soul of America.” Definitely Dylan (1 April 2020), https://www.definitelydylan.com/listen/2020/4/1/special-episode-murder-most-foul.

The Warren Commission Report. JFK Assassination Records. National Archives. https://www.archives.gov/research/jfk/warren-commission-report/toc.

Wolfman Jack with Byron Laursen. Have Mercy! Confessions of the Original Rock ’n’ Roll Animal. Warner Books, 1995.

Yoder, Andrew. Pirate Radio Stations: Tuning in to Underground Broadcasts in the Air and Online, third edition. McGraw-Hill, 2002.

This is a brilliant trilogy of essays on Dylan and JFK. I was knocked out by the research, imagination and scholarly insight, which culminates in what is surely the best account of “Murder Most Foul” I have read. I was 16 in 1963 so have some vivid memories of that dark day in Dallas. In suburban Wembley where I grew up, there was an American family on the corner of our road and my mother insisted on visiting that evening to extend her condolences. Stunned would be the simplest word to sum up the days after 22 November.

I was impressed by the way you explored the twisted skeins of empathy that led Dylan to talk about his identification with Lee Harvey Oswald at the ECLC fiasco. You point out Kennedy was so angry after the failure of the Bay of Pigs invasion that he sacked Allen Dulles as Director of the CIA in November 1961. But JFK and his brother Robert were still ardent Cold Warriors and they continued to support covert attempts to sabotage Cuba and kill Castro. Suze Rotolo, who led a trip to Cuba in 1964, would have been very aware of that.

There is, I think, one error in your first essay which puzzled me. You write: “The most artistically ambitious song on Dylan’s sophomore album is ‘A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall’, inspired by the Cuban Missile Crisis. In October 1962, spy plane photos revealed that the Soviets had placed missiles in Cuba, giving the rival superpower easy striking capacity against the United States. Kennedy shared the news in an address to the American people, and a terrifying standoff ensued for several days.”

But surely Dylan first performed “A Hard Rain” on 22 September 1962 at an all-star hootenanny at Carnegie Hall. (Clinton Heylin, “A Life in Stolen Moments: Day by Day 1941-1995”, p. 33) This is exactly a month before the Cuban Missile Crisis began on 22 October 1962 when President Kennedy went on national television to announce Soviet missiles had been discovered on the island of Cuba.

Dylan has encouraged the idea that “A Hard Rain” was born out of the Cuban Missile Crisis. In Nat Hentoff’s sleeve notes on the back of the Freewheelin’ album, Dylan says: “Every line in it is actually the start of a whole new song. But when I wrote it, I thought I wouldn’t have enough time alive to write all those songs so I put all I could into this one.”

The astonishing truth is that Dylan somehow anticipated the event. He conjured up the lyrical and musical and imaginative resources to create a work that captured the closest the world had come to nuclear Armageddon—before it happened.

Interesting you preface your third essay with Bruegel’s The Triumph of Death. That is the image that haunts DeLillo’s Underworld and (almost) ties the book together. Congratulations on a fine series of essays.

What an excellent way to round off this astonishing trilogy, my head is still spinning from some of the connections you’ve made. “Whenever something triggers the old trauma, the event is reenacted in the present as if unfolding right now for the first time.” – this in relation to Hamlet’s circular nature, is such a brilliant observation that could have somehow only come from you. It’s this kind of stuff that makes you one of the best writers on Dylan at the moment. And I’m not just saying that because you occasionally (and kindly) refer to my work.

I also want to add that my latest podcast was influenced by the first two parts of this series, though in ways that, while completely obvious to me when I started, I can’t fully recall now. Something about assassinations (Lincoln in the case of the episode) and Dylan’s long epic songs about disasters that might serve as analogies for our time? And of course, as you pointed out in your comment, Shakespeare. But I’ll stop trying to grasp at straws now.

I’ve always wondered about the message that accompanied Murder Most Foul, and I think I just realised what it is – it’s that he hoped we’d find the song “interesting”. Not “I hope you enjoy it”, or “I hope you like it”, instead, “you might find it interesting. It makes sense, because it’s not exactly a story you might “enjoy” (which reminds me Dylan taking a shot at people who say they “enjoy” Blood of the Tracks – “people enjoying that type of pain”).

I’m especially stuck on his wish to “stay observant” because “observe” has such a curious double meaning. Written at the beginning of the pandemic, did he mean for us to stay observant of COVID rules and regulations? Or did he mean “observant” in the sense of someone who is paying attention, another way of saying “be aware of what is happening”, or even, as one might have done before the backlash set in, “stay woke”?? In other words, observing those in power means what exactly? Obedience or Skepticism? But even if we settle on the definition of "observe" as "watch", the Zapruder film is a prime example that a consensus on what is being observed cannot always be reached. The irony is that Dylan couldn’t have known that he was writing this message at a pivotal moment when the divide between perceived realities among the US population was about to widen into a chasm. I can only once again recommend the Contrapoints YouTube video on Conspiracy, which I think you’ll love, and I’ll leave you with a joke I came across in the comment section to that video:

A JFK conspiracy theorist dies and goes to heaven.

When he arrives at the Pearly Gates, God is there to receive him. "Welcome. You are permitted to ask me one question, which I will answer truthfully."

Without hesitating, the conspiracy theorist asks,

"Who really shot Kennedy?"

God replies, "Lee Harvey Oswald shot him from sixth floor of the Texas School Book Depository. There were no accomplices. He acted alone"

The conspiracy theorist pauses, thinks to himself, then says "Shit! This goes higher up than I thought.."