Laura Tenschert explores Dylan’s recent preoccupation with time in “‘Today and Tomorrow and Yesterday Too’: Time in Bob Dylan’s Work of the 2020s.” She rightly observes, “Although Bob Dylan has always cultivated the reputation of an artist whose feet ‘point away from the past’ [‘Restless Farewell’], his recent work suggests that he is getting more comfortable with the idea of looking back” (174). Laura dates this impulse back to Dylan’s 2016 Nobel Prize in Literature, prompting him to reckon with his legacy. She traces examples of his engagement with time in Rough and Rowdy Ways (2020), Shadow Kingdom (2021), and his exhibition Retrospectrum (2021). “These are not merely nostalgic enterprises, but rather opportunities for Dylan to examine his own past through the lens of the present with an eye on the future, bringing them all on ‘the same level’” (174). That last phrase is plucked from his 1978 interview with Randy Anderson. Asked if he was at peace with his past, he replied, “I try to be, yeah. I always try to keep my past and my present and my future all on the same level” (qtd. Tenschert 174).

In 1978, Dylan gave multiple interviews in which he credited his art instructor Norman Raeben with teaching him a different understanding of time, where the multiple perspectives of past, present, and future can simultaneously occupy the same plane. His painting classes in the spring of 1974 broke a creative logjam, resulting in the major albums that followed: Blood on the Tracks (1975), Desire (1976), and Street-Legal (1978). These lessons weren’t confined to his songwriting, nor did they end in the seventies. Dylan’s return to painting during the pandemic seems to have reanimated Raeben’s influence in his post-pandemic work.

How timely, then, that the first major exhibition of Norman Raeben’s art was recently held at the Venice Jewish Museum (November 24, 2024 – January 14, 2025). I wasn’t able to see it in person, but I did read the wonderful catalogue, Norman Raeben (1901-1978): The Wandering Painting (Sillabe, 2024). Curator Fabio Fantuzzi gathered dozens of Raeben’s dispersed works, displayed them to the public, and edited an enlightening book of images and essays by several art critics and a former student. These essays illuminate dark corners in the artist’s life, career, principles, and techniques. Raeben taught Dylan even more than I realized, and The Wandering Painting has a lot to teach us about shared concerns in their work.

Background

Some readers of Shadow Chasing will already be familiar with Raeben, but I bet others have never heard of him. So let me begin by summarizing what we already knew about the brief but influential intersection between Raeben and Dylan. Almost every scrap of information comes from a handful of sources: Dylan’s 1978 interviews with Jonathan Cott of Rolling Stone and Pete Oppel of the Dallas Morning News; his 1985 interviews with Cameron Crowe for the Biograph box set and Bill Flanagan for his book Written in My Soul: Conversations with Rock’s Great Songwriters; and a profile piece for The Telegraph by Bert Cartwright called “The Mysterious Norman Raeben.”

Numa Rabinowitz (aka Norman Raeben) was born in Kyiv, Ukraine, in 1901, and emigrated to New York City in 1914. He was the son of Solomon Rabinowitz (pen name Sholem Aleichem), the prominent Yiddish writer whose works form the basis of Fiddler on the Roof.

Dylan first heard about Raeben from friends of Sara. He told Pete Oppel, “They were talking about truth and love and beauty and all these words I had heard for years, and they had ’em all defined. I couldn’t believe it. I asked them, ‘Where do you come up with all those definitions?’ and they told me about this teacher” (qtd. Cartwright 85). He went to visit Raeben at his studio on the eleventh floor of Carnegie Hall and decided to enroll in his class. “Five days a week I used to go up there, and I’d just think about it the other two days of the week. I used to be up there from eight o’clock to four. That’s all I did for two months” (qtd. Cartwright 86).

Dylan admitted to Oppel that his art classes drove a wedge between him and Sara: “It changed me. I went home after that and my wife never did understand me ever since that day. That’s when our marriage started breaking up. She never knew what I was talking about, what I was thinking about. And I couldn’t possibly explain it” (qtd. Cartwright 86). Nevertheless, he persisted because of the positive impact these classes had on his art.

Dylan confided to Jonathan Cott that, prior to meeting Raeben, he had lost his creative spark.

Right through Blonde on Blonde I was doing it unconsciously. Then one day I was half-stepping, and the lights went out. And since that point, I more or less had amnesia. Now you can take that statement as literally or metaphysically as you need to, but that’s what happened to me. It took me a long time to get to do consciously what I used to be able to do unconsciously. (Cott 672)

Raeben reignited the spark and gave Dylan new tools for making art again: “I was convinced I wasn’t going to do anything else, and I had the good fortune to meet a man in New York City who taught me how to see. He put my mind and my hand and my eye together in a way that allowed me to do consciously what I unconsciously felt” (Cott 672).

Guided by Raeben, Dylan began to reconceptualize time in relation to his songs. Painting is a spatial art form (the whole thing is there all at once), and song is a temporal art form (unfolding over time, note after note, line after line, verse after verse). Dylan’s immersion in painting led him to approach songs differently, introducing a spatial dimension that accommodated multiple perspectives in time. Here’s how he described it to Cott:

I didn’t know how to pull it off. I wasn’t sure it could be done in songs because I’d never written a song like that. But when I started doing it, the first album I made was Blood on the Tracks. Everybody agrees that that was pretty different, and what’s different about it is that there’s a code in the lyrics and also there’s no sense of time. There’s no respect for it: you’ve got yesterday, today and tomorrow all in the same room, and there’s very little that you can’t imagine not happening. (Cott 672)

For example, Dylan applied this painterly approach in the album’s opening song, “Tangled Up in Blue.” In his discussion with Cameron Crowe for Biograph, he explained,

I was just trying to make it like a painting where you can see the different parts but then you also see the whole of it. With that particular song, that’s what I was trying to do with the concept of time, and the way the characters change from the first person to the third person, and you’re never quite sure if the third person is talking or the first person is talking. But as you look at the whole thing, it really doesn’t matter. (qtd. Cartwright 89)

Elaborating upon his songwriting experiments for Blood on the Tracks, Dylan told Bill Flanagan:

See, what I was trying to do had nothing to do with the characters or what was going on. I was trying to do something that I don’t know if I was prepared to do. I wanted to defy time, so that the story took place in the present and past at the same time. When you look at a painting, you can see any part of it or see all of it together. I wanted that song [“Tangled Up in Blue”] to be like a painting. (833)

Raeben the Artist

Raeben’s role as the wiseman behind Dylan’s seventies renaissance has long been known, but very few of the artist’s own works have been available until now. His lack of recognition had nothing to do with his talent. According to his son, Jay Raeben, “he was very poor at the business of art, of promoting himself” (Pappas 21). He was also exceedingly unlucky. After a productive trip abroad in the 1920s, all of his paintings were stolen during the return trip to America. Years later, a catastrophic fire at his Connecticut studio destroyed the majority of life’s work (Pappas 29n3).

Struggling to support himself as an artist, Raeben turned to teaching, beginning his famous art classes at Carnegie Hall in the late forties and continuing through the end of his life in 1978. As Andrea Pappas notes in her essay “Locating Norman Raeben in American Art,” “The more hours an artist spends teaching, the fewer they have for their own art production, and Raeben’s son notes that over the years, teaching took up an increasingly large share of the artist’s time” (22). Given the transformative influence he had as a teacher, we can hardly wish it otherwise. But we’ll never know the sacrifices Raeben made in terms of unrealized potential while he was devoting forty hours a week for three decades to making other artists better.

Despite all these obstacles and setbacks, Raeben remained committed to making art for his entire life, and scores of his works survive among family members and various private collections. The Wandering Painting secures his legacy as a highly accomplished artist in a variety of media and styles. Fabio Fantuzzi situates Raeben in multiple contexts, beginning with his earliest years in the United States:

There he joined the flourishing Jewish artistic milieu of New York City and studied with exponents of the American realist movement of the Ashcan School, being influenced by Robert Henri, John Sloan, George Luks, and Max Weber. These first collaborations led to a full-time painting career in the 1920s and 1930s, marked by long journeys in North African and Europe, where he refined his style, complementing his early realist approach with influences derived from the European tradition and especially the School of Paris. (12)

These various affiliations are visible like tree rings in The Wandering Painting, charting Raeben’s development from realist to avant-garde artist, though he moved freely back and forth between them. He painted and sketched a wide range of subjects, from still life and city scenes to landscapes and nudes. For the sake of consolidation, I’ll concentrate chiefly on his portraits.

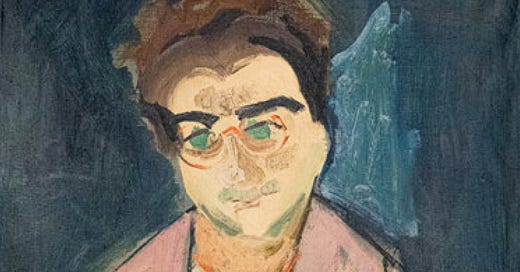

You can see his Ashcan influence on clear display in early portraits like this 1926 painting of his nephew Sherwin Kaufman:

The hand of the artist is palpable through the visible brushstrokes, but the primary focus remains on reproducing appearances realistically. Raeben was commissioned to paint several portraits of friends and supporters like the Adler family. Here is his portrait from the late thirties of the famous acting teacher Stella Adler.

When she wasn’t conducting her own classes for the likes of Marlon Brando, Adler was frequently a student in Raeben’s studio. This portrait hangs in the Stella Adler Studio of Acting.

You can begin to see Raeben’s movement away from realism in his 1942 portrait of Diana Adler.

Raeben switches materials, from oil on canvas to pastel on paper, but the most recognizable shift is in perspective. This painting draws as much attention to the artist’s attitude toward his subject as to Diana Adler herself. He takes enough care with the details of her face to make her recognizable, but the rest of the portrait seems hastily improvised, sketched with rough speed and communicating a sense of frenetic energy.

The Diana Adler portrait illustrates one of the hallmarks of modern art: a defiant refusal to accept the supposed limitations of one’s chosen form. Dylan works in the temporal form of song, but after studying with Raeben he sought ways to exceed those bounds by suspending or transcending time, or by interjecting a spatial dimension into his songs. For his part, you can see Raeben disturbing the stillness of his spatial form by introducing a sense of movement in time, putting the frozen face of Diana Adler in a cocktail shaker like he’s mixing a martini.

By the late sixties, the demands of the form had almost completely subsumed the residual content. Take a look at Raeben’s 1969 self-portrait:

The barrier between subject and object is always porous in a self-portrait, but this is particularly true for paintings unmoored from photographic realism. The point here isn’t to replicate what Norman Raeben looks like on the outside. This painting is all about feelings. Raeben paints himself from the colors of the city, staging a dramatic clash between flesh tones and drab industrial green, corroded rust, and smoggy gray, with contrasting hints of nature in the rosy dawn and blue sky breaking through. The severe brush strokes look like Raeben was trying to schmear his face into the canvas. That face registers discomfort. Maybe the pain comes from having his head twisted so far on his neck, as if forced to look away from the viewer, though his dark eyes still stare back at us. And what a neck it is, like a giraffe from the Bronx Zoo. Spend a lifetime sticking your neck out for others and see where it gets you. Fit to be hanged, though never in the Museum of Modern Art.

Of all the portraits in The Wandering Painting, the one I’ve stared at most is this untitled painting of a child that dates from the 1970s.

I find this image haunting. The girl’s smiling face is painted in vivid detail, with a bright white that practically glows through the gray shadows. The girl’s body, by contrast, is insubstantial, barely discernible at all. The angular lines and blotches provide some semblance of a torso and wardrobe, but I can’t even be sure that’s what I’m seeing. It could just as well be a separate abstract painting in its own right, with the girl’s delighted but spectral face materializing out of the darkness like the spirit of someone’s dead daughter at a séance.

Remember how Dylan described his painterly aspirations in composing “Tangled Up in Blue”: “I wanted to defy time, so that the story took place in the present and past at the same time. When you look at a painting, you can see any part of it or see all of it together” (Flanagan 833). Raeben seems motivated here by similar aims. The free-floating face can be appreciated discretely as distinct from her shadowy body. Furthermore, the face seems like something Ashcan Raeben could have painted in his youth, while the rest of the painting seems more Expressionist like his later paintings. It’s as if the past and the present are simultaneously occupying the same canvas, the very phenomenon Dylan was going for in Blood on the Tracks.

Raeben the Teacher

Out there in the larger art world, The Wandering Painting is important for rescuing a largely forgotten artist who deserves more recognition. But here in Dylan world, Raeben is still most important as a teacher. We learn a lot more about his teaching from Roz Jacobs.

Today she is a successful artist who splits her time between New York and France. When she was only 17 years-old, she began studying with Raeben in his Carnegie Hall studio. In her essay “Norman Raeben: Art Telescopes Time,” Jacobs concedes that he could be tough on his students, but he was also encouraging.

His methodology constantly challenged us to see beyond what we knew. Norman taught his students to accept that we were both geniuses and idiots, so we were free to try anything and everything—to triumph sometimes, to fail dismally other times, and to extract lessons from it all. He inspired us with the ideas of others including his own teacher Robert Henri, who said: “The object isn’t to make art, it’s to be in that wonderful state which makes art inevitable.” (57)

I love that advice from Henri, which extends to Dylan’s talent for “being in the moment” as a performer, shutting out distractions and opening up his receptors to inspiration and spontaneity.

In Dylan’s foreword to the exhibition catalogue for The Drawn Blank Series at London’s Halcyon Gallery, he reflected on his first art teacher at Hibbing High:

My drawing instructor in high school lectured and demonstrated continuously to “draw only what you can see” so that if you were at a loss for words, something could be explained, and even more importantly not misunderstood. Rather than fantasize, be real and draw it only if it is in front of you, and if it’s not there, put it there and by making the lines connect, we can get at something other than the world we know.

It’s interesting that Dylan highlighted this lesson from his first drawing instructor—“draw only what you can see”—because his most influential art teacher taught him the exact opposite lesson.

In an unpublished portion of Dylan’s interview with Jonathan Cott, he colorfully describes his first impressions upon meeting Raeben:

He says, “You wanna paint?” So I said, “Well, I was thinking about it, you know.” He said, “Well, I don’t know if you even deserve to be here. Let me see what you can do.” So he put this vase in front of me, and he says, “You see this vase?” And he put it there for 30 seconds or so, and then he took it away and he said, “Draw it.” Well, I mean, I started drawing it and I couldn’t remember shit about this vase—I’d looked at it but I didn’t see it. And he took a look at what I drew and he said, “OK, you can be up here.” And he told me 13 paints to get. Well, I hadn’t gone up there to paint, I’d just gone up there to see what was going on. I wound up staying there for maybe two months. This guy was amazing. (qtd. Cartwright 85-86)

It might seem at first like Raeben was testing Dylan’s memory, but I don’t think that was the point of this entrance exam. He was teaching a different lesson.

As we have seen, Raeben was trained in both American realism and European avant-garde. He was fully capable of painting proficiently in the realist mode, but he gradually became less interested in the verisimilitude of exact replicas. Raeben wasn’t evaluating Dylan’s ability to precisely recall and faithfully mirror the vase placed before him. You’ve already got the vase, what do you need a painting of it for?

Don’t draw the vase—that’s Raeben’s lesson. What matters is the artist’s unique perception of the vase in the moment of creation. The vase is the key for unlocking the artist’s vision. We don’t know what Dylan drew that day. All we know is that Raeben saw potential and so admitted the expert songwriter but novice painter into his class.

Just to be clear, I’m not suggesting that Raeben was solely interested in subjectivity. It’s the encounter between the artist’s inner perspective and the external world that interested him, and which animates Dylan’s own art as well. It’s the nexus between inner and outer, where subject merges with or acts upon the object—that’s the genesis of art.

Like Dylan, Raeben privileged feeling over intellect. According to Jacobs,

His emphasis was that “feeling is the core of art,” as opposed to the notion that concept and ideas are the core. In Norman’s studio the “percept preceded and took precedence over the concept.” That is not to say that we avoided the concept or abstraction. In our training, abstraction was an integral part of the creative process, but perception was the springboard for the imagination. By perception I mean experiencing the world through a co-mingling of our senses, mind and heart. (57-58)

Apply these same core beliefs to the medium of song, and what you get is the singer-songwriter movement that flourished in the seventies, with Dylan’s most Raebenical album Blood on the Tracks as a cutting-edge example.

Jacobs recalls Raeben’s “absolute presence,” a state of being that accommodated the commingling of past, present, and future. According to Jacobs, “Norman’s ability to transport us to another time was partly due to his absolute presence while painting. He used to say ‘Art telescopes time.’ The past and the future are in the present moment in which art is created” (58). Raeben tried to instill this same approach in his students. As Jacobs attests, “His teaching methodology was a dynamic force of changing ideas inspired by what he was seeing and thinking in that moment” (58).

If a painter or performing artist fully inhabits the current moment, they can re-create things from the past out of fresh feelings from the present. For example, Jacobs recalls, “While teaching and demonstrating on a canvas, the particular gray of a chair might trigger a memory from his childhood. He would try to paint the feeling of what that gray evoked rather than the local color of that chair” (58).

The vase or the face, the chair or the bird, those are the triggers. The artist’s feelings and perceptions—that’s the shot. In her essay “‘Ways of Seeing and Being Seen’: Norman Raeben in Paris,” Stefania Portinari connects Raeben’s philosophies with those of Gertrude Stein. In Stein’s study of Picasso, she declares, “In the nineteenth century painters discovered the need of always having a model in front of them, in the twentieth century they discovered that they must never look at a model” (3). Portinari observes,

This same lesson is what Raeben taught his students in the 1970s, the very same one he passed on to Bob Dylan: do not focus on the real object as if in an academic life-drawing session, do not think of the “correct” form it should take, do not try to depict a vase as a subject in itself, but first evoke a suggestion of it, let the perception of a certain theme emerge, and then act on the impulse.” (34; emphasis added)

I emphasize that last phrase because I think it perfectly epitomizes Dylan’s approach to live performance. So many of Dylan’s interview comments about Raeben’s influence focused on the immediate impact of these lessons on his songwriting. However, I think the more lasting legacy of Raeben can be felt in Dylan’s approach to performance from the mid-seventies onward.

We tend to credit fellow musicians for inspiring this approach, from jazz improvisers like Miles Davis to rock improvisers like The Grateful Dead, and indeed those were important guides. But now I’m beginning to realize that Raeben was an important guide, too. His artistic and pedagogical lessons helped reorient Dylan’s approach to all forms of art. As a performer, Dylan stages fresh encounters with songs in much the same way that Raeben taught him.

Don’t draw the vase. Don’t aim for fidelity to a pre-existing form. Instead, in Portinari’s words, “let the perception of a certain theme emerge, and then act on the impulse” (34). Don’t play “Tangled Up in Blue.” Don’t try to reproduce the song that you recorded in Minneapolis and released on Blood on the Tracks. Instead, perceive it afresh and act on impulse. Shatter the old vase and replace it with tonight’s new, unique, unprecedented, unreproducible artistic expression. If you want to hear what this re-creative process sounds like in performance, check out Ray Padgett’s case study on the evolution of “Tangled Up in Blue” in concert over the years.

Here’s one more fascinating insight from Roz Jacobs. She reports that Raeben spent time working on a book about his aesthetic principles called Behind the Veil. He never completed it, but Jacobs helped with transcriptions and retained her notes. She shares this passage from the unfinished manuscript of Behind the Veil:

In our dreams at night we move on the tide of our emotions. We are musicians. Creatures of pure subjectivity. We fantasize. When we open our eyes, we become architects. We build the structure of the objective world. Between these two states there is a never-never land of tremendous flux. When we are not yet awake and no longer asleep. When the musician changes places with the architect. (qtd. Jacobs 59)

This passage instantly reminded me of Dylan’s credo from Chronicles: “A song is like a dream, and you try to make it come true” (165). Jacobs says that Raeben taught his students to regard feelings as the core of art. Here he associates feelings with the pure subjectivity of dreams. But dreams are also completely internal. In order to translate those inner perceptions and project them outward, the dreaming musician must enter into a bargain with the waking architect. Raeben privileged feeling over intellect, yes, but both are needed to create art. He discovered art in the flux where these two states converge, where “the musician changes places with the architect.” That confluence is also where you’ll find Dylan’s art.

The Poet with No Hands

I’ve focused on Raben’s impact on Dylan’s art, but we also have one striking example of Dylan’s impact on Raeben’s art. Perhaps you’ve seen it at the Bob Dylan Center in Tulsa:

Although the title doesn’t say it explicitly, Fantuzzi identifies the painting as a “portrait of Bob Dylan.” You can definitely see the resemblance.

I especially like the eyes in Raeben’s 1974 portrait. A year before Joan Baez sang “As I remember your eyes were bluer than robin’s eggs,” the painter already perceives them that way. Bluer than Raeben’s eggs.

It’s difficult to ignore the harsh critique implied by the title The Poet with No Hands. Dylan said that Raeben “put my mind and my hand and my eye together in a way that allowed me to do consciously what I unconsciously felt” (Cott 672). Maybe so, but apparently the teacher was unimpressed by the poet’s handiwork in his classes. Sean Wilentz relays this anecdote from classmate John Amato:

Manic, brusque, and unsparing, Raeben would dress down his pupils as a means to help instruct them, sometimes revising students’ work right on the canvas in his loose rapid style, to show them how it was done. According to the artist John Amato, another student of Raeben’s at the time, Dylan was one day painting a still life of a vase—the quintessential artistic effort to stop time—and was working heavily in blue, a favorite pigment of novice students, when Raeben looked at the canvas dismissively, telling Dylan that he was all tangled up in blue. A few days later, Amato recalls, Dylan astonished his fellow students by bringing in lyrics of an unknown song with that title. (140)

In this particular case, the lesson wasn’t “don’t draw the vase” so much as “don’t paint the vase so incompetently.”

But we don’t have to rely on second-hand accounts. The handless poet freely admitted to Pete Oppel that Raeben thought he was a lousy painter:

He talked all the time, from eight-thirty to four, and he talked in seven languages. He would tell me about myself when I was doing something, drawing something. I couldn’t paint. I thought I could. I couldn’t draw. I don’t even remember 90 per cent of the stuff he drove into me. (qtd. Cartwright 86)

I was startled by a passing comment from Fantuzzi about Raeben’s portrait of Dylan: “Entitled The Poet with No Hands, the oil painting also tells an intriguing story: according to various students, it is a demonstrative work that Raeben created a few days before the singer-songwriter’s arrival, which, by a curious coincidence, closely resembles Dylan” (54). Hold on: Raeben painted the picture before Dylan became his student? Do we in fact know that this is a portrait of Dylan and not just “a curious coincidence” of resemblance?

If Dylan’s version of their meeting is accurate (which we can never take for granted), then Raeben had already laid eyes on his prospective student before their first class together. If so, then Raeben was essentially following his own advice. Don’t paint the poet. Paint your artistic vision of him: “let the perception of a certain theme emerge, and then act on the impulse” (Portinari 34). However, if this chronology is correct, then Raeben wasn’t yet in a position to judge Dylan’s talent, or lack thereof, as the title suggests.

There’s another more mystical way of seeing it. Raeben was so revered by some of his students that they saw him as more than a teacher. He was their rabbi, their guru, an enlightened sage and prophetic seer. Roz Jacobs views Raeben this way. She recalls a memorable morning when she was cleaning the studio and Raeben walked in:

Norman suddenly, and uncharacteristically, launched into a premonition he was having right then and there. He looked at me almost mystically and said “I’m seeing something about you—it’s in the future. You’ll always be painting, but you’re going to be doing something different, something very important. I don’t know what it is, and it will involve painting but also some other media, film and something we don’t know about yet.” Then just as suddenly as he had launched into that premonition, he kind of snapped out of it as if it had been a spell that had broken, and he went on with his day. (59)

Jacobs firmly maintains that his premonition came true 27 years later with The Memory Project, her multimedia project to promote social justice through art and remembrance of her family’s traumatic past in the Holocaust.

I’m not as mystically minded myself, but I am intrigued by this notion of Raeben’s artistic perceptions not being confined to the past and present, but also encompassing premonitions of the future. If such a thing is possible, then maybe Raeben was looking 50 years down the road and foreseeing another artist embodying the shape-shifting powers of his star pupil.

One of those students who exalted Norman Raeben as far more than an art instructor was Bob Dylan. I’ll give him the final word:

I had met magicians, but this guy is more powerful than any magician I’ve ever met. He looked into you and told you what you were. And he didn’t play games about it. If you were interested in coming out of that, you could stay there and force yourself to come out of it. You yourself did all the work. He was just some kind of guide, or something like that. (qtd. Cartwright 86-87)

Works Cited

Cartwright, Bert. “The Mysterious Norman Raeben.” Wanted Man: In Search of Bob Dylan. Ed. John Bauldie. Citadel Press, 1990, 85-90.

Cott, Jonathan. “Bob Dylan as Filmmaker: ‘I’m Sure of My Dream Self. I Live in My Dreams.” Rolling Stone (26 January 1978). Rpt. in Every Mind Polluting Word: Assorted Bob Dylan Utterances. Ed. Artur Jarosinski. Don’t Ya Tell Henry, 2006, 556-69.

Crowe, Cameron. Interview with Bob Dylan. Biograph. Columbia, 1985.

Dylan, Bob. Chronicles, Volume One. Simon & Schuster, 2004.

Flanagan, Bill. Interview with Bob Dylan (March 1985). Rpt. in Every Mind Polluting Word: Assorted Bob Dylan Utterances. Ed. Artur Jarosinski. Don’t Ya Tell Henry, 2006, 831-40.

Fantuzzi, Fabio. Introduction. Norman Raeben (1901-1978): The Wandering Painting. Ed. Fabio Fantuzzi. Sillabe, 2024. 11-19.

---. “Portraits of Wandering: An Artistic Journey from Sholem Aleichem to Bob Dylan.” Norman Raeben (1901-1978): The Wandering Painting. Ed. Fabio Fantuzzi. Sillabe, 2024. 47-55.

Jacobs, Roz. “Norman Raeben: Art Telescopes Time.” Norman Raeben (1901-1978): The Wandering Painting. Ed. Fabio Fantuzzi. Sillabe, 2024. 57-61.

Mossinger, Ingrid and Kerstin Drechsel, eds. Bob Dylan: The Drawn Blank Series. Prestel, 2008.

Oppel, Pete. “Enter the Tambourine Man,” Dallas Morning News (22 November 1978).

Padgett, Ray. “Now It Goes Like This: ‘Tangled Up in Blue.’” Flagging Down the Double E’s (25 January 2025),

Pappas, Andrea. “Locating Raeben in American Art.” Norman Raeben (1901-1978): The Wandering Painting. Ed. Fabio Fantuzzi. Sillabe, 2024. 21-30.

Portinari, Stefania. “‘Ways of Seeing and Being Seen’: Norman Raeben in Paris.” Norman Raeben (1901-1978): The Wandering Painting. Ed. Fabio Fantuzzi. Sillabe, 2024. 30-39.

Stein, Gertrude. Gertrude Stein on Picasso. Liveright, 1970.

Tenschert, Laura. “‘Today and Tomorrow and Yesterday Too’: Time in Bob Dylan’s Work of the 2020s.” The Politics and Power of Bob Dylan’s Live Performances: Play a Song for Me. Eds. Erin C. Callhan and Court Carney. Routledge, 2024.

Wilentz, Sean. Bob Dylan in America. Doubleday, 2010.

Great to have this important relationship, Dylan and Raeben, better documented and then explored by someone with the critical knowledge of Dylan's art. The essay is a key reference point, but also a doorway to more deeply understanding Dylan. When I looked at the poet with no hands and thought of Raeben's advice--don't paint the vase--I wondered whether the painting contemplates the pain of someone with artistic visions but no way to get them down on paper (no hands--the student whose just walked in the door). The pain we've heard about before: And there's something on yer mind you wanna be saying, That somebody someplace oughta be hearin', But it's trapped on yer tongue and sealed in yer head, And it bothers you badly when your layin' in bed...And the poet and the painter far behind his rightful time...tolling for the tongues with no place to bring their thoughts...i saw 10,000 talkers whose tongues were all broken...i went to tell everybody but i could not get across...I have a head full of ideas and they're driving me insane... AND speaking of hands, we have Dylan's constant scribbling in A Complete Unknown, his many manuscripts on hotel stationary and napkins at the Dylan Center and finally "I'd dance with you, Maria, but my hands are on fire". This poet has hands, but, the poet standing before Raeben had not yet learned to paint.

I'm curious if anyone ever interviewed Raeben about Dylan?