I love the Cincinnati Art Museum. I go there a half dozen times a year to see what’s new and to revisit familiar works that feel like old friends. I’ll typically fit in a trip as a reward to myself for finishing up a project, or to clear my head when I’m overworked or hit a dead end. Since my writing usually involves Dylan these days, that means that my mind is typically filled with thoughts of him as I wander through the galleries. I’ll be looking at a painting or sculpture and find my thoughts drifting Dylanward.

Rather than resisting this impulse, I’ve decided to indulge it in a new series for Shadow Chasing called “Dylan + Art.” I would describe myself as an amateur art lover. I’m not an artist or an art history scholar. I’ve never even taken an art class. But I’m capable of responding to art, deeply and subjectively, and I bet you are, too. I’m not setting out with a specific plan or agenda other than periodically sharing great art from my hometown and putting it in conversation with Dylan’s work. Every now and then I’ll take a trip to a local museum, imagining the reader virtually at my side, and look at art through Dylan-tinted glasses.

The Burghers of Calais

My first installment focuses on Auguste Rodin’s The Burghers of Calais. This special exhibit is on display at the Cincinnati Art Museum from November 2023 through June 2024. According to the museum’s website,

In spring 2024, the museum will serve as a research platform, hosting contemporary working artists, students, faculty, and invited guests from and beyond the University of Cincinnati’s Fine Arts program to access and respond to Rodin’s singular accomplishment, his workshop practice, and the complex history of France and its colonies at the turn of the century. This activity will culminate in the exhibition Rodin | Response, opening in mid-June.

When I think of Rodin, I think of The Thinker. Frankly, I didn’t know anything about The Burghers of Calais until I randomly wandered into galleries 104 and 105 on a recent trip to the museum. Fortunately, this exhibit is designed with folks like me in mind, and the curators do an excellent job of succinctly providing background context for understanding these magnificent, haunting, inspiring sculptures. Follow me in and let’s take a look.

The original sculptures were commissioned by city officials in 1884 and cast in bronze in 1895. They remain on public display in front of the Hôtel de Ville in Calais. Several later casts have been made. The sculptures on display in Cincinnati are on loan from the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. Rather than grouping them together, as in Calais, the individual figures are presented separately in two adjacent galleries. Cincinnati has casts of four of the six burghers: Jean D’Aire, the brothers Pierre and Jacques de Wissant, and Eustache de St. Pierre. According to the museum label,

The civic monument The Burghers of Calais is among the most revered and recognizable works by French sculptor Auguste Rodin (1840-1917). Conceived in the mid-1880s, the sculpture group commemorates six leading citizens of Calais who offered to sacrifice their lives to save their city during the Hundred Years War in the mid-1300s. It is both a pinnacle of European figural art and a radical break with the standards of monumental sculpture of the time. Rodin’s shift in focus from triumphant glory to human suffering forever changed what forms and meanings a public monument could take. The figures are barefoot and wear sackcloth; their anguished faces and strained bodies express the suffering of war and their stoic bravery.

Bravery and dignity in the face of physical decay and human suffering. I’ve been thinking about these themes a lot lately in relation to the Rough and Rowdy Ways tour, which made its latest stop in Cincinnati in October 2023. Dylan has been addressing these subjects with increasing urgency and eloquence throughout his 21st century work. My faint sense of a kinship between late Dylan and Rodin’s sculpture grew stronger as I made my way through the galleries. I’ve continued to ponder these interconnections since my museum visit in early December 2023. The more I reflect, research, and write about these two great artists in juxtaposition, the more light and shadows they cast upon each other’s work.

Before getting into specifics about the burghers, it’s worth foregrounding some broader issues raised by comparing sculpture to music. Consider the relationship between stillness and movement. These bronze sculptures are solid, motionless, and unchanging. That’s the nature of the medium. And yet, like a lot of the most interesting modern artists, Rodin pushes against the limitations of his form. He might have fixed his subject at any moment, but he chooses to depict them in the act of walking out of Calais and into the arms of the enemy, which is to say walking through their decimated city, past scenes of abject suffering, knowingly and willingly headed toward their deaths. [Or so they assumed. The English King Edward III spared the lives of the six would-be martyrs at the request of his wife Queen Philippa.] How do you communicate movement through the spatial medium of sculpture? That’s an essential challenge Rodin takes up in this project.

Dylan works primarily in the medium of song, which is a temporal medium of movement: one note follows the next, one word follows the next, one song follows the next, one concert follows the next, etc. Furthermore, the mercurial Dylan has been animated his whole career by constant movement and change—don’t look back—he not busy being born is busy dying. And yet, particularly in late Dylan, we find him grappling with stasis. “I know it looks like I’m moving, but I’m standing still,” as he sings in “Not Dark Yet.” How do you communicate stillness within the propulsive forward momentum of song? Let’s have a look at Rodin and have a listen to Dylan to find out.

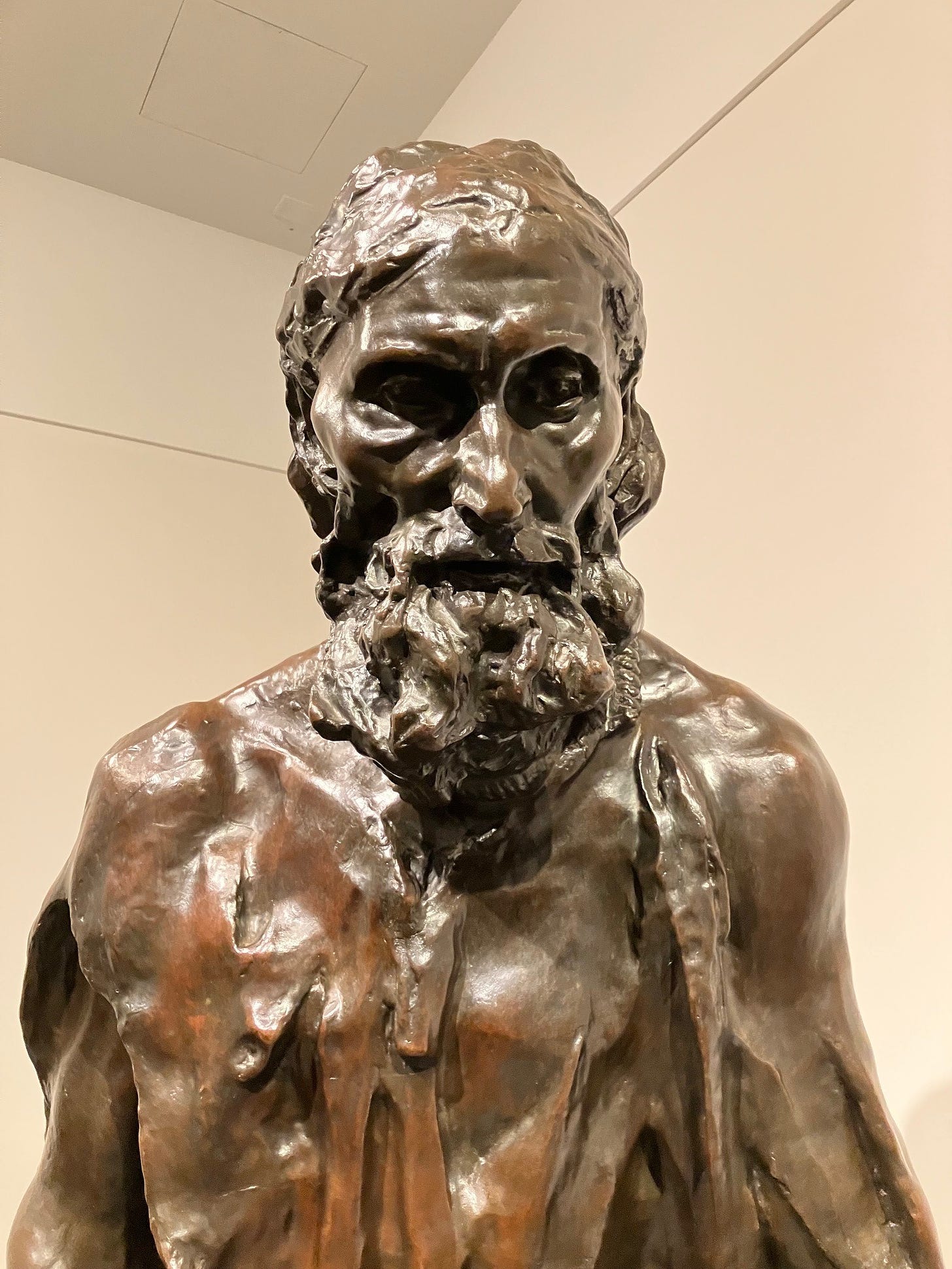

Jean d’Aire

The first figure I encountered was a nude study of Jean d’Aire. I didn’t realize it at the time, but the statue on display in Calais differs markedly from the cast in the Cincinnati exhibit. In Calais, as well as other casts like this one at the National Gallery in Washington, D.C., d’Aire is fully clothed in a long robe:

However, the cast in Cincinnati is a preliminary study that strips the subject bare. The museum label explains,

By the 1880s, the practice of using live models to sculpt preliminary studies—often at a smaller scale—had long been promoted by European art academies. This tradition directs the artist to come to terms with body structure and balance of pose before the figures is “dressed” with costume and props. Rodin’s initial small nude study for Jean d’Aire resulted in such a successful, powerful composition that he had it enlarged and authorized casts to be made on the monumental scale.

The disrobed d’Aire looks rather odd. You sort of wish he’d put something on. His torso seems disproportionately elongated. His arms are unusually stretched out, as if he is straining to carry heavy but invisible weights. His pose strikes me as somewhere between a gymnast on the rings and Lucky carrying Pozzo’s bags in Waiting for Godot.

Nakedness suggests exposure and vulnerability, but it also communicates unadorned candor—the naked truth. I think of King Lear’s first impression of Poor Tom out in the storm. The king looks upon this wretch and has an epiphany about the basic human condition: “Is man no more that this? Consider him well,” counsels Lear. “Thou art the thing itself. Unaccommodated man is no more but such a poor, bare, forked animal as thou art” (3.4.101, 104-6). Lear knows the feeling, having given away his kingdom and been evicted from his daughters’ houses out into the storm. Dylan translates this sentiment into sixties hipsterism in “Like a Rolling Stone,” where the rich debutante Miss Lonely has been reduced to a homeless wretch. The singer scolds her at first, but ultimately he consoles her with the reassurance that she might be better off stripped of her pomp and illusions: “When you ain’t got nothing, you got nothing to lose / You’re invisible now, you got no secrets to conceal.”

It’s worth remembering that, though Rodin captures these figures at the most distressed moment of their lives, they once were prosperous dignitaries. They are Les Bourgeois de Calais, to use the French title, which is to say they are members of Calais’s wealthy bourgeoisie. After months of relentless siege, however, the burghers were diminished, financially and physically, by starvation. Once upon a time they dressed so fine, but now, stripped of their former status, they are left scrounging for their next meal.

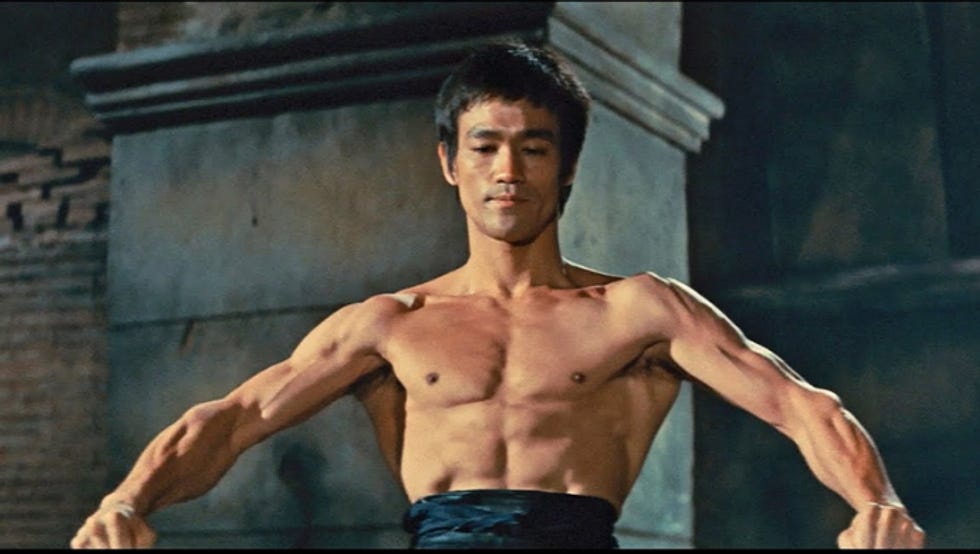

In order to save their fellow citizens from further deprivation and degradation, they offer up their lives to save the city. Jean d’Aire doesn’t have much meat left on his bones, but this unaccommodated man has screwed his courage to the sticking place. He carries himself more rigidly than the other burghers. His spine, like his arms, is stiff and straight, as if he’s bracing for a fight and determined not to yield. He volunteered to die for the city, but he won’t be led to the slaughter like a meek lamb. Mess with this martyr and he’ll go Bruce Lee on your ass! He will sacrifice his life, but not his dignity. Just try him. I d’Aire you.

The museum label gets it right: “While other of the burghers seem to express inward emotions, Jean d’Aire is defiance personified. A resolute attitude seems to determine his posture and expression.” Agreed. I associate this same sense of defiance with Dylan. Rather than waning with the years, his pugnacious resolve only gets stronger. For Dylan as for d’Aire, there is weariness and woe on the journey through a decimated world. But they do not go gentle into that good night. They rage against the dying of the light. (As another Dylan put it.)

Pierre de Wissant

Directly across from Jean d’Aire stands Pierre de Wissant. Major contrast. His body is lithe and sinewy, with a torqued pose that suggests movement. Is he looking back at Calais for the last time, as he leaves his hometown and this earthly life behind? Pierre de Wissant’s fate is frozen on his face, like he just lost a staring contest with Medusa.

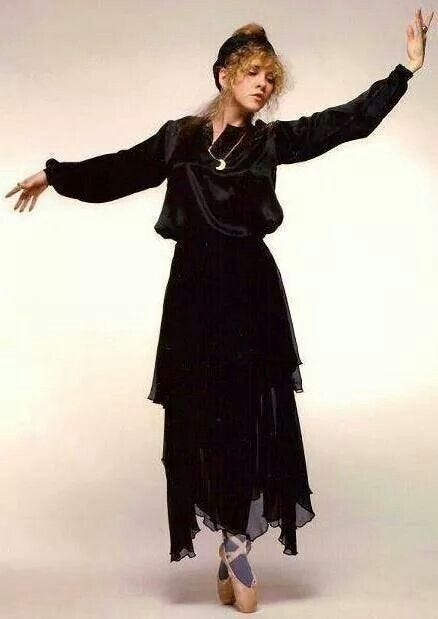

But his body sends different signals. The twisting hip, the swishing garment, the flared-out hand—he doesn’t belong in a museum, he belongs on a dancefloor with Madonna or on a stage beside Stevie Nicks. Jean d’Aire stares down death; Pierre de Wissant dances with it. In their separate but compatible ways, these statues face mortality with vitality.

The museum label includes a fascinating reflection from Rainer Maria Rilke. While working on this piece, I looked up the original source, which comes from Rilke’s monograph on Rodin. Not only was the Austrian poet a great admirer of the French sculptor, but for a time Rilke moved to Paris and served as Rodin’s personal secretary.

He responds with great sensitivity and intelligence to Rodin’s entire body of work, but some of his most perceptive observations come in the section on The Burghers of Calais. Rilke was particularly inspired by the sculpture of Pierre de Wissant. From the poet’s perspective, this figure is letting go of life before crossing over into death:

It is a parting from all uncertainty, from a happiness not yet realized, from a sorrow that now will wait in vain, from people who live somewhere, and whom he might have met at some point, from all the possibilities of tomorrow and the days to come, and also from a notion of death as something distant, gentle and silent, something that would come only after a very long time. This figure, placed by itself in a dark, forgotten garden, would make a fitting monument for all who have died young. (100-01)

I especially love that last observation, which would never have occurred to me, but now strikes me as spot-on. I feel the same way about this hawk-eyed insight: “He walks along, but then turns back one last time, not to see the town, nor those who are weeping or those walking with him. He turns around, back to himself, his right arm is raised, bent ambivalently at the elbow; his hand opens in the air and releases something, as if he were setting a bird free” (100).

Check out this photo I took of Pierre de Wissant:

Look at the shadows cast on the wall behind the statue. His hand looks like a bird, right? Who knows what lurks in the heart of Pierre de Wissant? Rilke knows.

And Dylan knows. I think again of “Not Dark Yet”: “Shadows are falling, and I’ve been here all day.” It’s the condition of being stuck, more monument than man, on constant display under the dark eyes of public scrutiny, trapped on the threshold between no longer and not yet, between the overexamined life and unwelcome death. You don’t have to be a statue in a museum to know what that feels like. You could also be an aging rock legend.

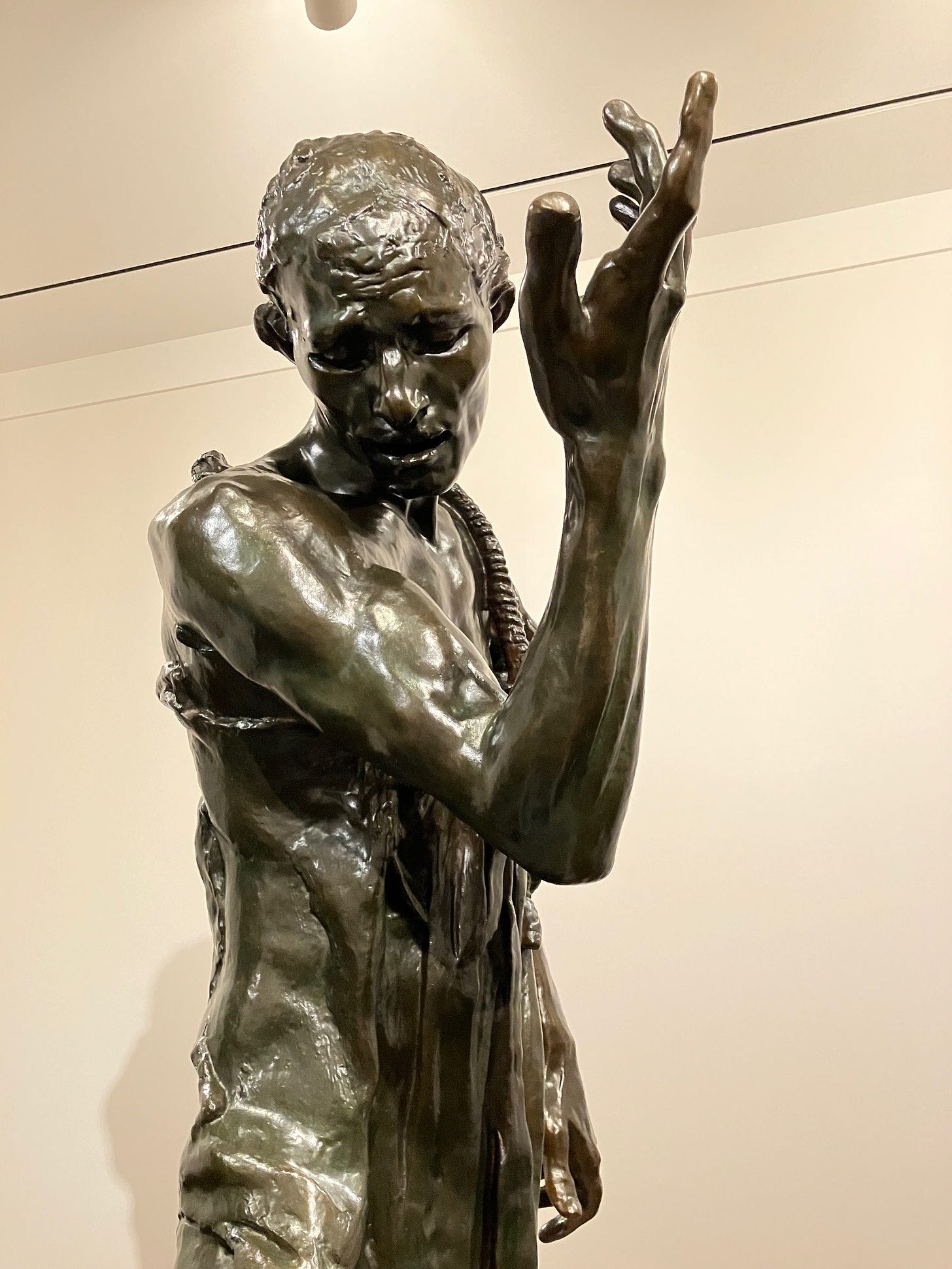

Jacques de Wissant

Pierre’s brother is housed in the gallery next door. Despite this physical separation, I think of these brothers as dance partners. Jacques is John Travolta to Pierre’s Uma Thurman in the Calais danse macabre.

The museum label offers this interpretation:

Jacques de Wissant’s raised right hand allies him with his brother Pierre (displayed in the adjacent gallery), whose hand is similarly posed. Perhaps a gesture of aversion or shielding, it balances the figure’s trailing left leg and throws into question whether he is starting to move or has just come to a halt.

Again, Rodin has managed to interject a sense of movement and drama into this immobile hunk of bronze.

The other notable feature of Jacques de Wissant’s sculpture is the giant key to the city that he carries in his left hand.

This serves as a reminder of the city’s defeat, since Edward III demanded the key to the city, along with the six burghers, as the price for ending the siege of Calais and lifting the food embargo that had starved the city’s residents for weeks.

You know who Jacques de Wissant looks like? Derroll Adams.

Dylan fans know who I’m talking about. As former musical partner of Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, Adams earned an invitation to the notorious party at the Savoy Hotel in 1965 captured in Dont Look Back. You know the one—“Who threw that glass!” A pissed (American etymology) Dylan confronts a pissed (British etymology) partygoer and accuses him of breaking a glass in the street. Derroll Adams etches his role into Dylan lore by trying to play peacemaker.

“Boys. Boys. Can we have a drink over here?” Cheers, mate! Give me just one drink from your loving cup, Derroll (aka Jacques).

Eustache de St. Pierre

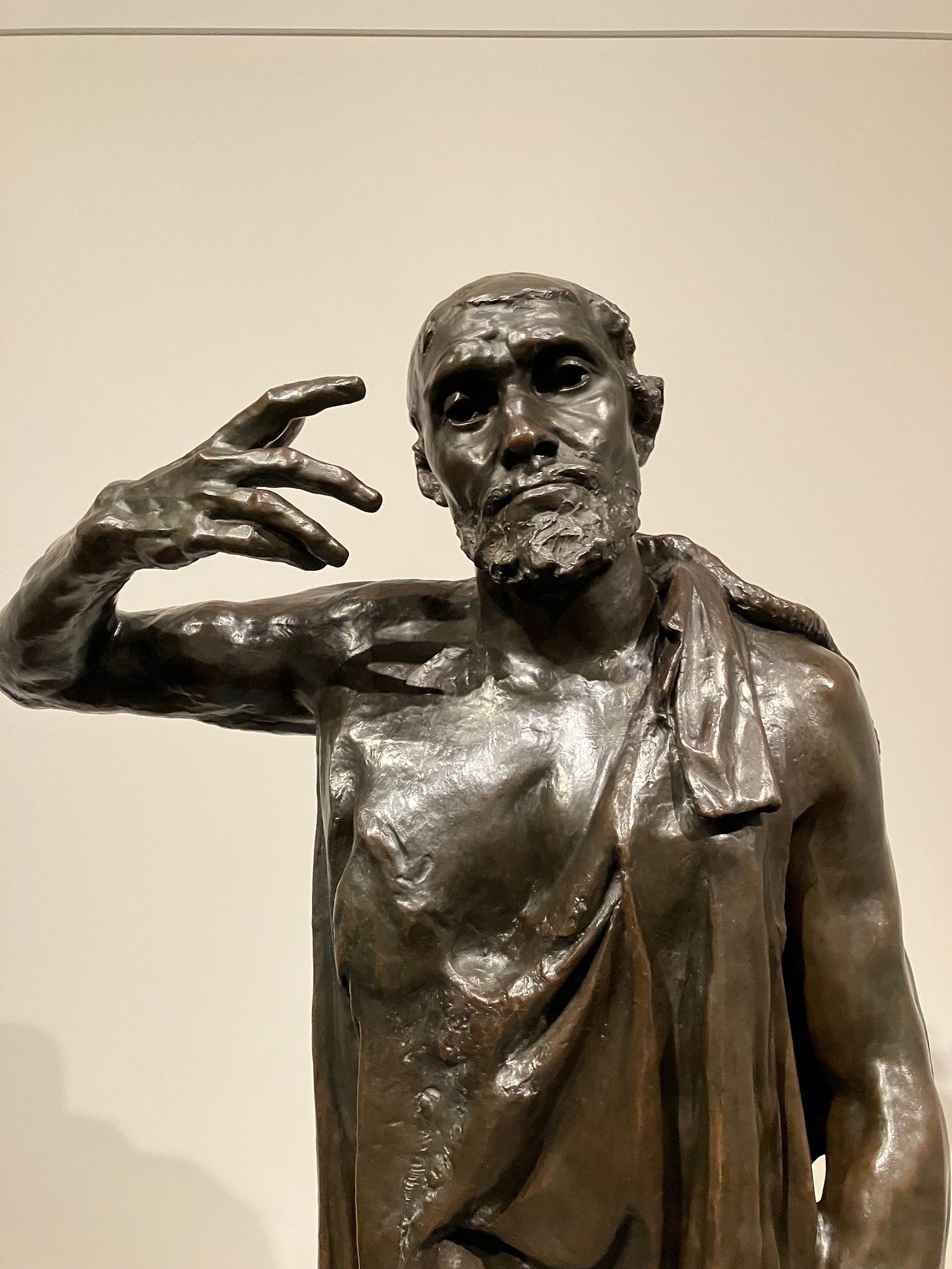

Eustache de St. Pierre looks to me like a figure who walked straight out of myth, or out of a Dylan song. He is the epitome of the perpetual wanderer.

Jean d’Aire stands his ground; Pierre de Wissant corkscrews so that he’s turned both forward and backward; and Jacques de Wissant is caught somewhere between starting and stopping. Eustache de St. Pierre is the one figure that is all forward momentum, unequivocal and unwavering, marching toward his destiny with eyes wide open. He stares at the road ahead, but there is also an inwardness to his gaze, as if a deeper journey is taking place within him. This is bedrock Dylan.

I wasn’t aware of it when I took the shot, but there’s an intriguing effect in the profile photo of Eustache de St. Pierre. Because of the position of two spotlights pointed at different angles, the figure’s shadows are projected on the wall behind him to both the left and the right. It’s as if Eustache is trailed by his former self; cf. “Every Grain of Sand”: “Sometimes I turn, there’s someone there, other times it’s only me.” But it’s also as if Eustache is pursuing his future self; cf. the line from “Mr. Tambourine Man” where my newsletter gets its name: “It’s just a shadow you’re seeing that he’s chasing.”

The road is long and the journey is exhausting, but the predominant feelings communicated by Eustache de St. Pierre are courage, strength, and endurance. He is equal to the task before him, a task for which he volunteered and is determined to see through to the end. It should come as no surprise that the subject of this sculpture was the very first volunteer to sacrifice himself for the city. As the museum label notes, “Eustache steps forward, his weight on his left foot, leading the group to its fate. He bows his head in resignation, and his powerful but gaunt body seems to bear a great burden.” The load is heavy, but he bears it with grace. You can see again why he reminds me of late Dylan.

The ones who walk away from Calais: dead men walking. According to Rilke, Rodin’s first stroke of genius in The Burghers of Calais was his decision to concentrate upon what each man carries within him as he leaves the city to face his death.

He turned his complete attention to the moment of their departure. He saw how these men began to walk. He felt how each of them was filled with the whole life they had lived, how each one stood there, weighted with his past and ready to carry it out of the city. Six men appeared before him, of whom no two were alike. […] But each one of these men had come to a decision and lived through this last hour in his own way, rejoicing in spirit and suffering in body, which still clung to life. (99)

If you wanted to write that out in verse, you might begin, “You must leave now, take what you need you think will last / But whatever you wish to keep, you better grab it fast.” And you might end, “Leave your stepping stones behind, something calls for you / Forget the dead you’ve left, they will not follow you.”

In their separate but comparable ways, Rodin and Dylan set their work at the decisive moment of departure, leaving the past behind, taking what you need to get you through the journey, and following your inner calling wherever it leads, all the way down the line, to the last outback at the world’s end.

Late Dylan

The journey motif is important throughout Dylan’s work, but the pathway becomes particularly dark and rubble-strewn in his later work, beginning with Time Out of Mind. The walking theme is manic right from the start of that album. “I’m walking through streets that are dead,” the singer declares in the first line of “Love Sick.”

The first three songs each refer explicitly to walking in their opening lines, and all the songs on TOOM involve difficult journeys of one sort or another. The singer’s dreamlike wanderings work on multiple levels, from predatory stalking in the tradition of murder ballads, to religious pilgrimage in search of redemption and salvation, to the elusive pursuit of freedom in African American history. But you can read all my thoughts on those subjects in my book on TOOM. I’ve already confessed, no need to confess again.

The journey theme continues in “Love and Theft,” though it is less insistent. The best example is the closing song “Sugar Baby.” The singer walks a hard road from the start:

I got my back to the sun ’cause the light is too intense

I can see what everybody in the world is up against

You can’t turn back—you can’t come back, sometimes we push too far

One day you’ll open up your eyes and you’ll see where you are

We don’t know precisely where the singer is, but we know he never stays anywhere long. His life consists of the forward march, never turning back, moving away from the light and into the darkness. On the individual level, he appears to have been set wandering by the rejection of his lost lover. But like so many late Dylan songs, the singer is archetypal. He’s an Everyman on the road of life, traveling from birth to death. He is an allegory for humanity itself, traveling from creation to apocalypse. His back may be toward the sun, but his journey also leads toward the Son, the second coming of Christ on Judgement Day, as the song acknowledges in the final verse: “Just as sure as we’re living, just as sure as you’re born / Look up, look up—seek your Maker—’fore Gabriel blows his horn.”

Five years later on Modern Times, Dylan picks up where he left off in “Sugar Baby” with the opening track “Thunder on the Mountain”: “Thunder on the mountain, fires on the moon / There’s a ruckus in the alley and the sun will be here soon/ Today’s the day, gonna grab my trombone and blow.” Apparently we begin this album on Judgment Day, and here comes the Son. The sun/Son of the dawn keeps rising throughout Modern Times.

In “Rollin’ and Tumblin’,” it sounds like the singer may be the risen Son on the morning of the rapture: “The night’s filled with shadows, the years are filled with early doom / I’ve been conjuring up all these long dead souls from their crumblin’ tombs.” Dylan isn’t done invoking Jesus. In “When the Deal Goes Down,” he asserts, “We all wear the same thorny crown.”

You don’t have to read the singer literally as Christ, however. The larger point is that Jesus’s journey on the road to Calvary and his sacrificial crucifixion is allegorical. It represents the path we all tread in life from birth to death, the same emblematic journey depicted by Rodin in The Burghers of Calais. The singer’s words in “When the Deal Goes Down” could just as well be spoken by one burgher to another on their trek:

My bewildering brain toils in vain

Through the darkness on the pathways of life

Each invisible prayer is like a cloud in the air

Tomorrow keeps turning around

We live and we die, we know not why

But I’ll be with you when the deal goes down

The album is titled Modern Times, but it taps into ancient themes. “Workingman’s Blues #2” makes for an especially interesting companion piece to The Burghers of Calais. Several military references in this song suggest that the singer is a war veteran who struggles to make a living after his return home. The album came out in 2006, so Dylan could be thinking of soldiers from America’s wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. But the phenomenon he describes is universal and timeless. For instance, Richard Thomas points out that some lines from the song are taken from Ovid in Roman antiquity. Dylan might just as well be singing about the Hundred Years’ War between England and France.

I could well imagine one of the burghers saying farewell to his son or daughter using Dylan’s words (in French of course):

My cruel weapons been laid back on the shelf

Come and sit down on my knee

You are dearer to me than myself

As you yourself can see

I could also imagine one of the martyrs turning to the others at their departure and saying something akin to Dylan’s refrain:

Meet me at the bottom don’t lag behind

Bring me my boots and shoes

You can hang back or fight your best on the front line

Sing a little bit of these workingman’s blues

If I had to pick one late Dylan song as the soundtrack for The Burghers of Calais, it would be “Ain’t Talkin’.” Dylan writes this song in the tradition of Dante’s Inferno and T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land. It is a guided tour through a hellscape of pain and ruin. The journey is simultaneously personal and allegorical, external and internal, physical and spiritual. Here’s a representative verse from Dylan’s song that could serve effectively as an epigraph for Rodin’s sculptures, in both its suffering and its defiance:

Now I’m all worn down by weepin’

My eyes are filled with tears, my lips are dry

If I catch my opponents ever sleepin’

I’ll just slaughter them where they lie

Ain’t talkin, just walkin’

Through a world mysterious and vague

Heart burnin’, still yearnin’

Walkin’ through the cities of the plague

Each of the burghers is motivated by certain shared values, like those expressed in “Ain’t Talkin’”: “All my loyal and my much-loved companions / They approve of me and share my code.” But those companions are dropping by the wayside, and their old code is crumbling in these modern times: “I practice a faith that’s been long abandoned / Ain’t no altars on this long and lonesome road.” One can still appeal to the heavens for deliverance, but the old gods don’t seem to be taking requests anymore:

They say prayer has the power to heal, so pray for me, mother

In the human heart an evil spirit can dwell

I’m tryin’ to love my neighbor and do good unto others

But oh, mother, things ain’t goin’ well

If you were holding out hope for redemption or salvation at the end of Modern Times, then you’re going to be disappointed. The Everyman singer on his journey through life doesn’t make it to Heaven, at least no Heaven you’d recognize or aspire to inhabit. The Garden has been evacuated, and Eden is burning.

As I walked out in the mystic garden

On a hot summer day, a hot summer lawn

Excuse me, ma’am, I beg your pardon

There’s no one here, the gardener is gone

The song and the album end on a desolate note:

Ain’t talkin’, just walkin’

Up the road around the bend

Heart burnin’, still yearnin’

In the last outback at the world’s end

Late Style

One of the best presentations I heard at the 2023 World of Bob Dylan conference in Tulsa was delivered by Nina Goss. I’m lucky to count Nina as a friend and fellow basher on the Million $ Bash Roundtable at Jim Salvucci’s The Dylantantes. I consider her one of the most insightful and thought-provoking writers working on Dylan today. In her Tulsa paper (now published in the journal Aktualitet) she places late Dylan within the larger field of late style studies, a critical genealogy she traces from Theodor Adorno’s essay on Beethoven’s late style, through Edward Said’s On Late Style: Music and Literature Against the Grain, and beyond. I find her ideas about late Dylan very useful for clarifying his relationship to The Burghers of Calais.

Late Dylan has lasted so long that we have to start subdividing into smaller units. Nina writes about his “early late style” (1997-2001), characterized by “compulsive movement in stalled time” operating “on both the subjective and historical levels” (Goss 7). She notes that, “throughout late Dylan, we meet a persona who exhausts himself, mind and body, while bemoaning his self-imposed imprisonment in static temporalities” (7). The “self-willed alienation and repetition” that characterizes Dylan’s early late style gradually moves past solipsism toward increasingly allusive works beyond the confines of the self. “As the late work progresses, Dylan masters inhabiting landscapes that seem timeless or folkloric, yet are minefields sharded with history: events, voices, texts, figures” (7). Microsoft Word puts a red squiggly line beneath “sharded” because it doesn’t recognize that verb. But I think it’s precisely the right word to describe the bricolage technique of the most recent late Dylan works.

No Dylan song is more densely sharded with history than “Murder Most Foul,” first released as a single during the pandemic and then repurposed as the epilogue of Rough and Rowdy Ways.

The word “play” appears 61 times in the span of 17 minutes, most often in the form of song requests. However, Nina summons up a different sense of the word “play”: “a fish playing a line is when the fish is caught on a hook and helplessly thrashing and exhausting itself against its capture” (Goss 10). This image communicates something fundamental about Dylan’s late style:

I think this play figures the condition of subjectivity Dylan has mastered in his late work—the only “now” is the song in play, the historical past is in a constant rotation of new stories and new meanings, yet American history is always caught on its own violence, atrocity, and injustice. Progress itself feels like no more than flailing against undying dark history. The song ends, play murder most foul—play the song we are hearing, play more conspiratorial, unanswered lethal violence (which is what King Hamlet cries out for when he uses this phrase)—this stuckness is more American than we may want to admit. (Goss 10)

In place of historical progress—the engine driving the civil rights movement from which young Dylan emerged as so-called “voice of his generation”—late Dylan offers instead variations on stuckness, like a fish squirming vigorously but helplessly on the hook. Nina returns to this concept of stuckness in her conclusion, arguing that late Dylan is incompatible with faith in historical progress: “If we really dig into his harlequinade of history and memory and its never-conclusive ethics and dig into the fact that his static urgency is hard to reconcile with political optimism, then we find ourselves in the quandary of late style” (Goss 14).

I find this argument compelling, and I’m especially captivated by Nina’s evocative image of a fish “playing” on the hook. A similar impulse draws me to The Burghers of Calais in relation to late Dylan. Each figure is galvanized with a sense of movement, like that thrashing fish, yet the movement leads nowhere: these solid bronze statues are stuckness personifed.

If you look up Rodin’s original placement of the figures at the town square in Calais, you’ll find them arranged in a rough circle. The sculptor imbues these solid bronze statues with a sense of movement and yet confines them to doing laps around the city center, forever commencing their departure but never leaving Calais.

Rodin was commissioned to produce the monument in 1884, but when Calais officials saw his preliminary casts, some balked because the figures failed to conform to heroic ideals of sculpture that prevailed at the time. The sculptor fervidly defended his approach and ultimately persuaded the committee to move forward with the installation, which was completed in 1895.

Rodin insisted upon depicting the emaciated bodies of the burghers on artistic, historical, and moral grounds:

I did not hesitate to make them as thin and weak as possible. If, in order to respect some academic convention or other, I had tried to show bodies that were still agreeable to look at, I would have betrayed my subject. These people, having passed through the privations of a long siege, no longer have anything but skin on their bones. The more frightful my representation of them, the more people should praise me for knowing how to show the truth of history. (qtd. Elsen and Jamison 81)

Rodin refused on principle to deify the burghers as infallible superhumans. They were brave, yes, but they were also subject to mortal fear, weakness, and doubt like the rest of us.

I have not shown them grouped in a triumphant apotheosis; such a glorification of their heroism would not have corresponded to anything real. On the contrary, I have, as it were, threaded them one behind the other, because in the indecision of the last inner combat which ensues, between their devotion to their cause and their fear of dying, each of them is isolated in front of his conscience. They are still questioning themselves to know if they have the strength to accomplish the supreme sacrifice—their soul pushes them onward, but their feet refuse to walk. (qtd. Elsen and Jamison 81)

“Their soul pushes them onward, but their feet refuse to walk” would make a great song lyric. The sculptor’s reflections on The Burghers of Calais sit comfortably alongside Nina’s reading of late style Dylan, and both reinforce my sense of artistic kinship between Dylan and Rodin.

The Calais committee was expecting uncomplicated images of larger-than-life immortal heroes. Rodin instead presented the suffering, vulnerability, and uncertainty of true-to-life mortal humans. Nina argues that some Dylan fans still cling to an image of Dylan as idealistic champion of progressive causes. But in his late work Dylan instead presents images of history as sharded and stalled.

This is what happens when you go to the museum with a head full of ideas about one great artist, and then encounter fascinating work by another great artist working on similar subjects in a different medium. You find yourself, like those poor lost burghers, stuck in Cincinnati with the Calais blues again.

Works Cited

“Auguste Rodin’s Burghers of Calais (November 14-June 2, 2024).” Cincinnati Art Museum. https://www.cincinnatiartmuseum.org/art/exhibitions/special-features/rodin/#:~:text=November%2014%E2%80%93June%202%2C%202024&text=Conceived%20in%20the%20mid%2D1880s,England%20in%20the%20mid%2D1300s.

Dylan, Bob. Official Song Lyrics. The Official Bob Dylan Website.

https://www.bobdylan.com/.

Elsen, Albert E. and Rosalyn Frankel Jamison. Rodin’s Art: The Rodin Collection of Iris and B. Gerald Cantor Center of Visual Arts at Stanford University. Oxford University Press, 2003.

Goss, Nina. “Today and Tomorrow and Yesterday, Too: Rough and Rowdy Ways / ‘Murder Most Foul (2020), Bob Dylan, and Late Style Studies.” Aktualitet: Litteratur, Kultur og Medier 17.3 (2023): 4-15. https://tidsskrift.dk/aktualitet/article/view/141617/185402.

Rilke, Rainer Maria. Auguste Rodin. Parkstone International, 2011.

Rodin, Auguste. The Burghers of Calais, modeled 1884-95, cast 1985, bronze, 82 ½ x 94 x 95 in., Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Iris and B. Gerald Cantor, 1989.

Shakespeare, William. King Lear. Arden Shakespeare Third Series. Ed. R. A. Foakes. Bloomsbury, 1997.

Thomas, Dylan. “Do not go gentle into that good night.” Poets.org. https://poets.org/poem/do-not-go-gentle-good-night.

Thomas, Richard F. Why Bob Dylan Matters. Dey Street Books, 2017.

Great piece. At what point did that last line occur to you?