Dylan + Art: The Gaze

Part 1, Bodies

I’ve been enjoying Ray Padgett’s latest series on Flagging Down the Double E’s covering each concert from Bob Dylan and The Band’s Tour ’74 on its 50th anniversary. Check it out if you haven’t already. I especially loved his piece on the concerts in Landover, Maryland, January 15-16, 1974, because he focuses on Dylan’s daytrip to The Phillips Collection in Washington, D.C. It’s interesting to see Dylan contemplating these great paintings, especially when we know that he would embark upon his own intensive painting classes only a few months later.

Gazing at these pictures, I thought how distracting it must have been to have a photographer snapping shots while you’re trying to have a private moment with a painting. It must be impossible to lose yourself in art when you’re pulled out of that experience to be put on display yourself.

Dylan has wrestled with this dilemma his entire adult life as a stage performer. During his 1997 London press conference, he mused, “When you’re up on stage and you’re looking at a crowd and you see them looking back at you, you can’t help but feel like you’re in a burlesque show” (1201). Even when he’s offstage, he’s still under a spotlight, subject to relentless public scrutiny, object of the gaze of a million dark eyes. Reading Ray’s piece and looking at Dylan looking at these paintings, it got me to thinking about larger issues of perception in art—the dynamics of looking and being looked at—ideas packed into that loaded term “the gaze.”

These thoughts motivated me to put on my heaviest winter coat and trek to the Cincinnati Art Museum in search of works that incorporate their looked-at-ness into the art in interesting ways. I found so many examples that I’m going to split my written reflections into two parts. Part 1 will focus on bodies as the object of the gaze, and Part 2 will focus on subjects doing the gazing within works of art.

It’s hard to talk about the gaze without starting with Laura Mulvey. She famously defined “the male gaze” in her groundbreaking essay, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” originally published in Screen in 1975, and frequently anthologized many times since then. Mulvey analyzes fetishized depictions of women’s bodies in mainstream films. Though her vocabulary may have been novel at the time, the concepts are ancient and applicable to other art forms, including the painting and sculptures we’ll be looking at.

Here is the heart of Mulvey’s explanation of the male gaze:

In a world ordered by sexual imbalance, pleasure in looking has been split between active/male and passive/female. The determining male gaze projects its phantasy on to the female figure which is styled accordingly. In their traditional exhibitionist role women are simultaneously looked at and displayed, with their appearance coded for strong visual and erotic impact so that they can be said to connote to-be-looked-at-ness. Woman displayed as sexual object is the leit-motif of erotic spectacle: from pin-ups to strip-tease, from Ziegfeld to Busby Berkeley, she holds the look, plays to and signifies male desire. (11)

Eve Hearing the Voice by Moses Jacob Ezekiel

If you want an ideal example of the male gaze that predates Mulvey’s essay by almost a hundred years, then feast your eyes on Moses Jacob Ezekiel’s statue Eve Hearing the Voice, a large bronze sculpture modeled 1876, cast 1904, and residing in the Cincinnati Art Museum.

The title refers to the aftermath of the Fall in the Garden of Eden. As the story goes, Eve was tempted by the serpent to eat the forbidden fruit from the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil, which she also gave to Adam. “And the eyes of them both were opened, and they knew that they were naked” (Genesis 3:7). God seeks out Adam and interrogates him, but Adam deflects blame onto Eve. Ezekiel captures the moment when Eve hears the voice of God’s stern rebuke:

And the Lord God called unto Adam, and said unto him, Where art thou? / And he said, I heard thy voice in the garden, and I was afraid, because I was naked; and I hid myself. / And he said, Who told thee that thou wast naked? Hast thou eaten of the tree, whereof I commanded thee that thou shouldst not eat? / And the man said, The woman whom thou gavest to be with me, she gave me of the tree, and I did eat. / And the Lord God said unto the woman, What is this that thou has done? And the woman said, The serpent beguiled me, and I did eat. (Genesis 3:9-14)

That last verse is the moment Ezekiel dramatizes in his sculpture, with the snake still sneaking around beneath Eve’s feet.

Ezekiel captures an abject moment of fear and shame. The word “captures” is exactly right, because there’s something very predatory about the gaze invited by this statue. Eve is prey to the all-seeing eye of God, the harshest of all “male gazes.”

Eve is also exposed and ensnared by the gaze of the male artist who sculpted the female model. Furthermore, she is put on display in the Cincinnati Art Museum for the visual pleasure of the spectator, who is permitted to gaze upon her with curiosity and impunity, feeding the appetites of every passerby who pauses for a free look. The power dynamic of male dominance described by Mulvey in film is pounded into bronze by Ezekiel in his sculpture of the nakedly objectified Eve.

The museum label provides this interesting information about the sculptor.

Moses Jacob Ezekiel embraced biblical subjects to express his Jewish faith. He recalled, “I was modeling a seated statue of Eve after the Fall, representing Eve when she hears the voice of God in the garden and is ashamed. I wanted to make her like a fallen Titaness (female giant) and perfectly human.”

Ezekiel was from Richmond, Virginia. He and his family relocated to Cincinnati after the Civil War, then later moved to Berlin and finally Rome. According to the museum label, “He moved so naturally in the international spheres of art, politics, and religion that three European monarchs knighted him.”

This brief bio might leave you with the impression that Ezekiel’s work has enjoyed universal acclaim. But I’ve done some research since my trip to the museum and discovered otherwise. The native Virginian was the first Jewish cadet ever to graduate from the Virginia Military Institute. The curators mention that Ezekiel moved to Cincinnati after the Civil War, but they neglect to mention that he was busy during the war fighting for the Confederacy.

Ezekiel remained faithful to the “Lost Cause” ideology of the Confederacy for the rest of his life, producing several statues to commemorate the fallen heroes (as he saw them) of that cause. One notable example is his statue of General Stonewall Jackson that stood on the campus of his VMI alma mater from 1912 until its removal in 2020. Jackson was a professor at VMI before the Civil War, and he was one of the most prominent Confederate generals during the conflict. For the first century that the statue stood on the VMI campus, cadets were required to salute it whenever they passed by.

Ezekiel’s most infamous monument is the Confederate Memorial at Arlington National Cemetery. This elaborate 32-foot statue was commissioned by the United Daughters of the Confederacy and approved in 1906 by Secretary of War William Howard Taft (a native of Cincinnati), later to become President of the United States and later still Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. Ezekiel built the statue in Rome and shipped it to Arlington, where it was dedicated in 1914 (on the birthday of Jefferson Davis, the President of the Confederacy) by U.S. President Woodrow Wilson (a fellow Virginian). Ezekiel died in 1917 and had to be buried in Rome because transportation of his body was impossible during the First World War. After the war, his request was honored to be reinterred at the base of the Confederate Memorial in Arlington. There he remains, but not his monument. After years of protest over its romanticized and racist portrayal of the Lost Cause, the monument was finally removed just last month.

Perhaps none of this background information is strictly relevant to Eve Hearing the Voice. Nevertheless, the image of a figure trying to shield herself from view, combined with the issues this artwork raises about what we choose to confront directly and what we choose to hide from, will make me look differently at this provocative yet troubling statue the next time I return to the Cincinnati Art Museum.

The Sacred Hour by Ferdinand Hodler

On my regular trips to the museum, I always pause over this arresting canvas by the Swiss painter Ferdinand Hodler. The two women represent a different sense of looked-at-ness than Ezekiel’s Eve. Hodler’s enigmatic figures relish the gaze. Are their writhing bodies meant to be seductive? Maybe. But that’s not really what comes across to me. Their faces are impassive and impenetrable. They aren’t mere playthings for the spectator’s gaze. They know more than we do, but they aren’t telling, at least not directly. They’re signaling something in a sign language only they understand, daring us to decode the message, like a dream sequence from Twin Peaks.

The museum label provides additional context for interpreting this painting: “Like many nineteenth-century European artists, Ferdinand Hodler was interested in the pictorial expression of inner realities. This subjective approach to art is known as Symbolism. Hodler’s characteristic works are timeless allegories—often on a monumental scale—that feature stately groups of flat, stylized figures composed into a rhythmic and repetitive pattern.” The curator adds that “Compositions such as this illustrate Hodler’s self-devised philosophy of Parallelism, a principle of repetition that he saw as the foundation of all human experience.”

It seems significant that there are two figures in the painting. They remind me of the doubles Freud associates with experiences of the uncanny. Whether viewing these mysterious doubles through the lens of psychology or parallelism, they recall the dualism in several Dylan songs, where the Gemini songwriter puts rival twins and oppositional pairs into animated tension (e.g., the Joker & the Thief, Tweedle Dee & Tweedle Dum).

Hodler envisioned his doubles working together in concert. As the museum label puts it,

The simple costumes and ritualistic gestures of these solemn and enigmatic figures identify them as Eurythmic dancers. Eurythmic dancing was an improvisational style in which emotions and ideas were translated into rhythmic body movements, requiring intense concentration. This translation of inner feelings into external gestures appealed to Hodler, who attempted to express in his paintings the underlying unity and harmony of the universe.

Hodler’s interiority may help explain why the women on display in his painting seem to deflect the male gaze rather than indulging it like Ezekiel’s Eve. The women in Hodler are dream symbols. They are manifestations of an inscrutable inner vision—“Where nothing comes up to the top / Everything stays down where it’s wounded / And comes to a permanent stop,” as Dylan sings in “Series of Dreams”—frozen in eurythmic sway to a secret inner rhythm.

Hodler produced several paintings based upon these same dream figures. Commenting upon the series, art critic Paul Müller finds in The Sacred Hour

an outstanding example of the role of the body in Hodler’s late Symbolist works. To the extent the figures abandon any role connected to activity, the body as a medium of expression becomes the focus. The contours of the body take on ornamental qualities as a result of the beauty of their lines, as is true of the composition as a whole. (64)

Hodler draws attention to bodies, yes, but not as commodities of desire to be consumed by the viewer. His figures conceal more than they reveal. What comes through most emphatically are aesthetic sensations: shape, line, torque, color, texture. This is figural painting, but it anticipates later developments in abstraction, where the interplay of gestures and patterns express emotion viscerally, rather than communicating meaning intellectually.

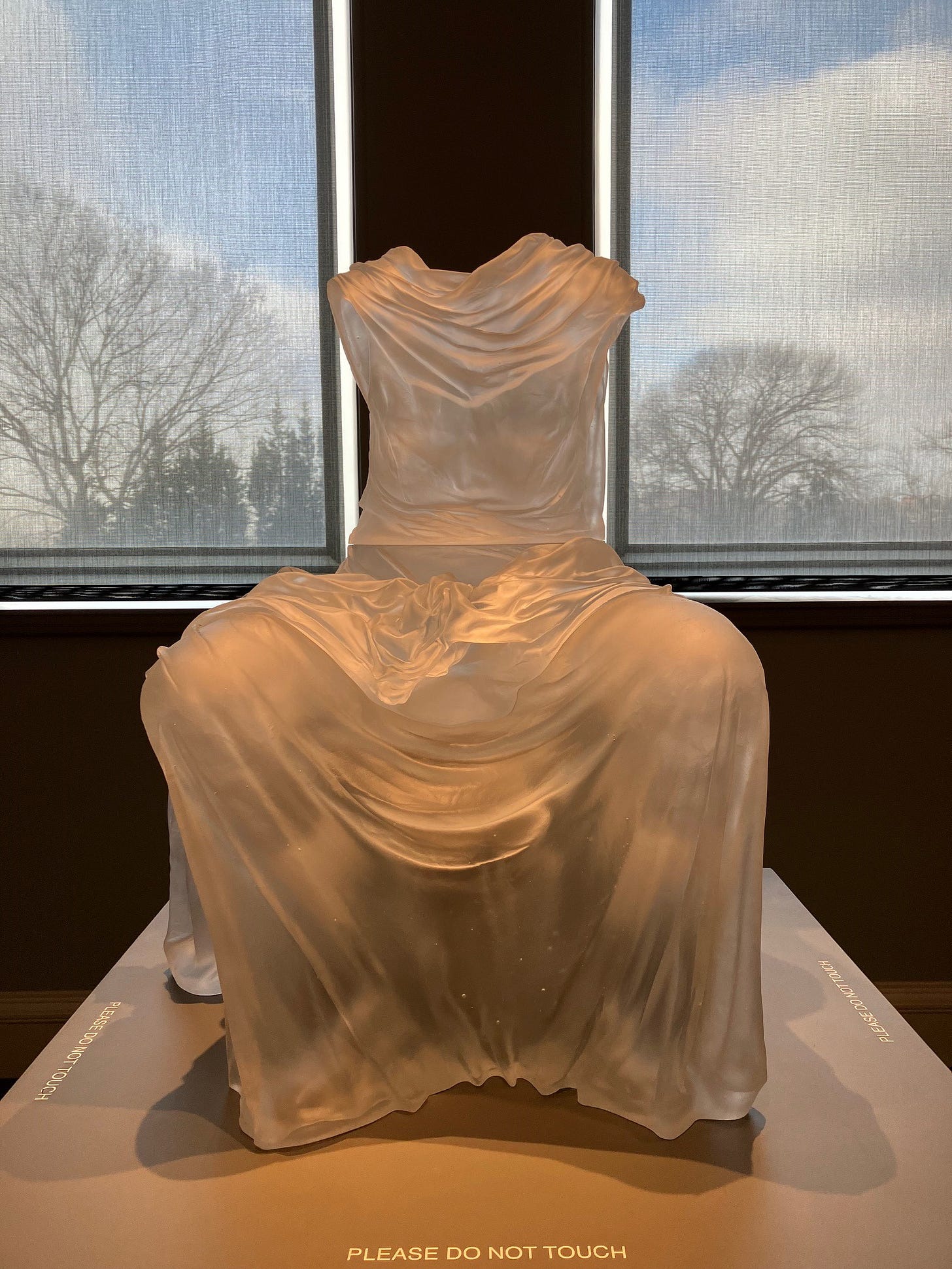

Seated Dress with Impression of Drapery by Karen LaMonte

I think this is one of the coolest pieces at the Cincinnati Art Museum. The curators’ placement of Seated Dress with Impression of Drapery is perfect, sitting beneath two windows facing west. The afternoon sunlight streams through the translucent glass, filling out the contours of the hollow sculpture. You can just about convince yourself that you see a ghost sitting on the pedestal, but you can only detect her spectral presence by the cloak she wears.

The invisible woman is sitting in the same position as the women in The Sacred Hour. I doubt that LaMonte had Hodler consciously in mind as a model. This is just the kind of happy serendipity made possible by museums. Put a bunch of great artworks together in the same building and they’re bound to strike up stimulating conversations. Pay attention as you wander through the galleries and you’ll hear them whispering to each other—admiring, flirting, gossiping, scheming, arguing. “Art is a disagreement,” writes Dylan in The Philosophy of Modern Song (35). It’s not just that listeners and critics have different tastes in rating good and bad art. The art itself is sometimes an expression of disagreement with other artworks.

I sense that Karen LaMonte’s Seated Dress with Impression of Drapery is a disagreement with and rejoinder to the objectification of women’s bodies by artists who traffic in the male gaze. This glass sculpture is beautiful, but it is also as empty as Cinderella’s discarded glass slipper. What is so conspicuously missing from Seated Dress with Impression of Drapery is the woman’s material, visible body inside the dress.

Ogle all you like, Monsieur Voyeur, your carnal appetites will go hungry. LaMonte gestures toward the visual pleasures fed by works like Ezekiel’s statue of Eve. It’s the same kind of male gazing done by the singer in Dylan’s “Where Are You Tonight?” as he stares at a stripper and considers taking a bite of forbidden fruit: “As her beauty fades and I watch her undrape / I won’t but then again, maybe I might / Oh, if I could just find you tonight.” LaMonte ain’t staging any strip shows at the Cincinnati Art Museum. This feminist artist withholds the body we expect to see undraped.

Why glass? We often associate glass with fragility, but that’s definitely not the case with this piece: LaMonte’s sculpture is thick and sturdy. But because it’s glass, we can also see through it. See-through garments are often used to titillate, giving the onlooker a peek at the prize barely hidden behind the curtain. Not so here. It’s a genius move on LaMonte’s part that she allows us to look through the seated figure’s garment but doesn’t allow us to see what we’re conditioned to look for.

Those were my independent observations after my recent visit to the museum. But then I did some homework and came across a very interesting 2020 essay by Karen LaMonte titled “On the Origin of Ideas: Artist as Explorer.” When I look at Seated Dress with Impression of Drapery and listen to its conversations and disagreements with previous art, the piece strikes me as quintessentially postmodern. So I was surprised to learn from this essay that LaMonte regards her own work in dialogue with the oldest known European sculptural art:

My studio in Prague, Czech Republic, is three hundred miles away from the cave in Germany where the oldest-known depiction of a human being was discovered: the Venus of Hohle Fels. Standing just two and a half inches tall, this diminutive carving in mammoth ivory is forty thousand years old. She fascinates me. We do not know why the carving was made or how it was used. Some anthropologists believe it is about fertility, sex, and reproduction—the power of the female essence. Maybe, like the Roman goddess of love and beauty we named her after, she represents the divine. (229)

For LaMonte, the recovered Venus of Hohle Fels and other similar works allow her to restore the severed connection to an ancient and vibrant tradition of women’s art, one buried in more ways than one beneath the objectifying male-dominated tradition that constitutes the bulk of Western art history. LaMonte reflects,

I am drawn to her because she embodies the enduring impulse to create art in our own image. I am also intrigued by questions she raises about gender and perception: Why are the majority of figurines made over the next ten thousand years female? And, since three-quarters of the handprints in prehistoric cave drawings were female, were the first artists mostly women? (230)

LaMonte considers herself a descendant of these first artists, and she approaches her own art as an extension and adaptation of that noble but underappreciated alternative tradition. She adds,

In thinking about the idea of Venus in the twenty-first century, I am also compelled to look at the broadest manifestation of the feminine, including not only cisgender females of every body type, race, and religion but also transgender and non-binary people. To me, exploring the expansive expression of inherent beauty is one of the most exciting aspects of reinventing an ancient icon. (231)

In my research I also learned a couple interesting facts about Karen LaMonte’s direct ancestors. It turns out that she is a descendant of Lawrence Southwick, who owned the first glassworks business in the thirteen colonies, opened in Massachusetts in 1638. She is also directly descended from Giles and Martha Corey. If those names ring a bell, you probably remember them from Arthur Miller’s play The Crucible. Martha Corey was tried, convicted, and hanged as a witch in the Salem witch trials. Giles Corey was also killed for his involvement with witchcraft; he was crushed to death with rocks. Now that’s the pedigree for a subversive artist!

I hope you’ve enjoyed our latest virtual trip to the Cincinnati Art Museum. Stay tuned for the next installment, when we’ll return to issues of art and the gaze in connection with Dylan, William Merritt Chase, Grant Wood, and Elizabeth Catlett.

Works Cited

Dylan, Bob. London Press Conference (4 October 1997). Every Mind Polluting Word: Assorted Bob Dylan Utterances, ed. Artur Jarosinski (Don’t Ya Tell Henry, 2006), 1197-1213.

--. Official Song Lyrics. The Official Bob Dylan Website.

https://www.bobdylan.com/.

---. The Philosophy of Modern Song. Simon & Schuster, 2022.

Ezekiel, Moses Jacob. Eve Hearing the Voice. Bronze, 55 7/8 x 40 7/16 x 33 / 9/16 inches, modeled 1876, cast 1904. Cincinnati Art Museum.

Hodler, Ferdinand. The Sacred Hour. Oil on canvas, 72 x 89 inches, circa 1907-1911. Cincinnati Art Museum.

LaMonte, Karen. Seated Dress with Impression of Drapery. Cast, sandblasted, acid-etched glass, 48.5 x 29.5 x 26.75 inches, 2005. Cincinnati Art Museum.

---. “On the Origin of Ideas: Artist as Explorer.” Karen LaMonte (Rizzoli/Electa, 2020), pp. 229-33.

Müller, Paul. “Gestures in Hodler’s Symbolist Figurative Paintings.” Ferdinand Hodler: View to Infinity, eds. Jill Lloyd and Ulf Küster (Hatje Cantz Verlag, 2012), 55-71.

Mulvey, Laura. “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.” Screen 16.3 (1975): 6-18.

Padgett, Ray. “Exit Through the Gift Shop.” Flagging Down the Double E’s (16 January 2024),

.

Graley - I am having a perfect afternoon having come in from the cold, drinking strong Yorkshire tea, listening to the New York sessions of BOTT, and reading the first half of your latest work. I feel like I just went on a metaphorical stroll through art, feminism, race/lost cause, and something more I can’t put my finger on. You are making the most of the freedom that the Substack format offers and it’s wonderful to see where you are taking it.

Always fun to have the Twin Peaks reference in there. I always heard Ballad of Thin Man in the goings on in the Red Room.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=n135fBPB5Rg