Of all the gin joints in all the towns in all the world, I’m glad Dylan walked into mine.

We have come to the legendary 1999 Bogart’s show, a concert unlike any other Dylan has played in his seven decades of tour stops in Cincinnati. I wasn’t around in 1965 when he was at his zenith of popularity and influence, and I can’t judge the quality of his March and November 1965 shows for myself since no bootlegs survive. But I have both audio and video recordings from Bogart’s, and most importantly I attended the show in person and can bear witness from a vantage point right beside the stage. From my perspective, the 1999 Bogart’s concert is the best Dylan ever played in Cincinnati.

Dylan Context

Dylan kept the wheels on the tour bus going round and round throughout the nineties, but his output of new songs ground to a halt for much of the decade. The creative drought ended with the torrential thunderstorm of Time Out of Mind (1997). This was his second collaboration with producer Daniel Lanois, who also produced the outstanding Oh Mercy (1989). Although some hardcore Dylanologists balk at Lanois’s heavy-handed production or grumble over Dylan’s relentless melancholy on Time Out of Mind, most fans and critics regard the record as a masterpiece. Less than a week after playing Cincinnati Gardens on February 19, 1998, Dylan stepped up to the podium at Radio City Music Hall to receive the Grammy for Album of the Year for Time Out of Mind, the only time in his illustrious career he ever took home the music industry’s top prize.

Months earlier it seemed that Dylan might be stepping up to the pearly gates instead. On May 24, 1997, he began experiencing severe chest pains at a gathering for his 56th birthday. Given that his father Abe Zimmerman died of a massive heart attack at the age of 56, it must have felt like the Grim Reaper was rapping at Dylan’s chamber door. He checked into St. John’s Hospital in Santa Monica the next day, where he was diagnosed with pericarditis, a potentially fatal inflammation of the sac surrounding the heart. The condition was caused by a previously undetected case of histoplasmosis, an infection from breathing in fungal spores (apparently inhaled during a motorcycle ride on his most recent tour). Dylan was discharged in early June, and by August he returned to the Never Ending Tour in August. But the health scare was a sobering reminder that no one’s tour through life is “never ending.”

Dylan’s brush with death impacted responses to Time Out of Mind. Already his most somber album, TOOM sounded like a letter from Lazarus’s tomb under these circumstances, even though the songs were written and recorded before his heart troubles. “I really thought I’d be seeing Elvis soon,” he quipped after his hospital release (qtd. Sounes 420). Fortunately, instead of jamming with the King in Heaven, Dylan was back on the road as a live performer, eventually winding his way back to the Queen City.

With the exception of bassist Tony Garnier, the NET roster turned over completely between Music Hall ’92 and Bogart’s ’99. Dylan was backed by David Kemper on drums, Charlie Sexton on guitar, and Larry Campbell on pretty much any instrument with strings. When he introduced his band to the Bogart’s audience, he described them as “some of the finest players in the country really.” Among NET aficionados, this lineup is prized as one of the very best, and that’s certainly true for Cincinnati fans. Not only did this unit make magic at Bogart’s ’99, but they also returned for stellar shows at Riverbend Music Center in 2000 and Cintas Center in 2001, the subject of the next chapter of this book. Since we’re going to be spending a lot of time with these fellas, let’s get to know them a little better.

David Kemper was drummer in the NET band from 1996 to 2001. He first met Dylan while playing with T-Bone Burnett’s band in 1978, and they became better acquainted during the drummer’s stint in the Jerry Garcia Band. Not long after Garcia’s death in 1995, Dylan invited Kemper to join his squad. In an interview with Alistair McKay for Uncut, Kemper recalled,

I had four days to learn 200 songs. Nobody said you better learn these songs—I just felt, I’m in Bob’s band, I better get a lay of the land. And we all know Bob Dylan songs. But it’s funny, there are things that escape you. There are songs that I didn’t remember. And others that I didn’t realize how amazing they were, or had a different meaning. So I went out and bought every album that I didn’t already have in my collection, and I laid on my bed for four days and just played his music.

The drummer could have saved himself the trouble. When he arrived for his first rehearsal, he found that Dylan no longer played the old songs the same way they appeared on his albums. The new recruit had to learn an entirely different set of arrangements, as well as remaining alert to the bandleader’s quicksilver improvisations live on stage. Welcome to the NET, Mr. Kemper.

Larry Campbell played in the NET band from 1997 to 2004. The first Dylan concert he attended was the Woody Guthrie Memorial Concert in 1968 when he was 13 years old. While still in his teens, Campbell began playing with Dylan’s pal Happy Traum. Later he played a lot of club gigs in New York, often with Tony Garner, which put him on Dylan’s radar. In an interview with Ray Padgett for Flagging Down the Double E’s, Campbell describes playing with Dylan as the privilege of a lifetime, but it was also challenging the first year to get up to speed. “At that second tour, I started to feel more comfortable,” he told Padgett. “Bob was starting to venture into rootsier music, cover tunes, bluegrass and old folk songs and all that, which I thought was great because a lot of that stuff was really right in my wheelhouse. I think with that particular band it seemed like we were trying to color everything with a rootsy feel—which was highly satisfactory to me, I could tell you that!” Campbell’s function in the band had evolved by 1999, especially after the departure of Bucky Baxter.

Initially I was the guitar player and Bucky played steel. When he left, then Charlie came in. Charlie became the guitar player, and I would jump from guitar to fiddle to steel to mandolin to banjo. Charlie’s presence in the band enabled me to do all the other things I can do, and Bob was trying to capitalize on that, which was cool although I had to be on my toes. I had some songs where I had just gotten comfortable with the guitar part, I had to suddenly change to a steel part or a fiddle part or something. But that’s what I do, so I was able to do it.

Judging by his sparkling performance at Bogart’s, Campbell had fully acclimated to his many musical roles by the summer of 1999.

That summer marked the official NET debut of fan favorite Charlie Sexton, though the guitar prodigy’s history with Dylan goes back much further. Fourteen years earlier, in his extensive interview with Cameron Crowe for the box set Biograph, the veteran singled out the rookie for praise. Reflecting on the state of popular music in 1985, Dylan mused,

Rock & roll, I don’t know, rhythm & blues or whatever, I think it’s gone. In its pure form. There are some guys true to it, but it’s so hard. You have to be so dedicated and committed and everything is against it. I’d like to see Charlie Sexton become a big star, but the whole machine would have to break down right now before that would happen. (866)

Sexton recorded some demos with Dylan a couple years earlier when he was only 15 years old. He first played on the NET stage on October 25, 1991, in Austin, Texas, and he sat in for parts of two Austin shows on October 26 and 27, 1996. He officially joined the band at the beginning of Dylan’s tour with Paul Simon on June 5, 1999, meaning that he had logged only five weeks on the job by the time he played Bogart’s. He would go on to earn his boss’s highest admiration. When Douglas Brinkley asked about Sexton in his 2020 New York Times interview, Dylan showered the guitarist with superlatives:

As far as Charlie goes, he can read anybody’s mind. Charlie, though, creates songs and sings them as well, and he can play guitar to beat the band. There aren’t any of my songs that Charlie doesn’t feel part of and he’s always played great with me. . . . Charlie is good on all the songs. He’s not a show-off guitar player, although he can do that if he wants. He’s very restrained in his playing but can be explosive when he wants to be. It’s a classic style of playing. Very old school. He inhabits a song rather than attacking it. He’s always done that with me.

Spread out over a few different terms spanning twenty years, Sexton is one of only five musicians to have played over 1,000 concerts with Dylan. As of September 2023, that elite group consists of Tony Garnier (3,187 and counting), George Receli (1,648), Donnie Herron (1,522 and counting), Stu Kimball (1,343), and Charlie Sexton (1,275).

Cincinnati Context

The Bogart’s show was hastily assembled. On Friday, June 25, 1999, the Cincinnati Post announced that tickets were going on sale the next day, cash only at the venue’s box office. That day also happened to be my fifth wedding anniversary, the first that my wife Cathy and I spent in Cincinnati.

I was shut out at the box office Saturday morning, but my pal Byron Russell later came through for me with a single general-admission ticket. I made it down to Bogart’s the afternoon of the concert and wormed my way close to the stage by showtime. It was my first Dylan concert in Cincinnati. I made my very first trip to the city the previous January to interview for an Assistant Professor of English position at Xavier University. I recently dug up my job offer letter and found it’s dated February 26, 1998: one week after Dylan played Cincinnati Gardens, and one day after he won the Grammy for Album of the Year. Our paths were drawing closer. On July 11, 1999, I found myself at the crossroads, only feet away from Dylan at Bogart’s.

This funky club is located in the Corryville neighborhood beside the University of Cincinnati campus. It has a floorplan common to bar-band venues the world over. Bogart’s is basically a big empty room with a stage at one end and a bar at the back. There is also a small balcony above the bar with a few tables and chairs, though I’ve never made it up there myself. With a capacity of less than 1,500, Bogart’s is by far the smallest venue Dylan has ever played in Cincinnati. It was one of four club dates he played at similar venues in the summer of 1999, detours in more ways than one from his mega-star joint venture with Paul Simon. [The others were EMU Ballroom in Eugene (June 14), St. Andrews Hall in Detroit (July 6), and Tramps in New York City (July 26)].

Seeing Dylan in a dive bar was different. I had never been so near the action, and I was surprised at how expressive he was for those close enough to pick up on his every gesture. Most of the night he was engaging and cheerful, quick with a smile, a wink, or a wiggle. This will sound weird, but from my crotch-level view I discovered that Dylan was unexpectedly active from the waist down! He kept doing this faux-Elvis gyration with his hip and legs, half parody and half flirtation. The packed room was a sauna, and plenty of that heat emanated from the randy 58-year-old strutting his stuff on stage.

I am not relying solely on my memory for these impressions. I have both audio (LB-1836) and video (D356) bootlegs for this concert. George Spanos, the webmaster for DVDylan, kindly shared footage shot by an anonymous taper perched in the balcony. It has been copied and converted multiple times, so the quality is far from pristine. Still, in a study otherwise focused on music, it’s nice to have access to the physical dimension of Dylan’s performance, including his collaboration with bandmates on stage and his charismatic interactions with the audience off stage.

The Concert

When: July 11, 1999

Where: Bogart’s

Band: Bob Dylan (vocals, guitar, and harmonica); Larry Campbell (guitar, fiddle, mandolin, and vocals); Tony Garnier (bass); David Kemper (drums); Charlie Sexton (guitar and vocals)

Setlist:

1. “Somebody Touched Me”

2. “My Back Pages”

3. “Desolation Row”

4. “To Ramona”

5. “Tangled Up in Blue”

6. “Girl from the North Country”

*

7. “Seeing the Real You at Last”

8. “Lay, Lady, Lay”

9. “Most Likely You Go Your Way (And I’ll Go Mine)”

10. “You Ain’t Goin’ Nowhere”

11. “Not Dark Yet”

12. “Highway 61 Revisited”

*

13. “Love Sick”

14. “Like a Rolling Stone”

*

15. “It Ain’t Me, Babe”

16. “Not Fade Away”

*

17. “Blowin’ in the Wind”

First Set

In 1999 Dylan opened most concerts with a traditional song. The Bogart’s show begins with “Somebody Touched Me,” a gospel number written by John Reedy and first recorded with his band the Stone Mountain Hillbillys in 1949. It was also covered in 1953 by the Fairfield Four, headed by Rev. Sam McCrary (father of Regina McCrary, one of the Queens of Rhythm). But the best-known version is by The Stanley Brothers, recorded in Cincinnati in 1961 and released the following year on Old Time Camp Meeting under the King Records label.

Dylan’s first public performance of “Somebody Touched Me” came the previous night in Maryland Heights, Missouri, but I like to think that was just a dress rehearsal before bringing it back home to Cincinnati. The hymn is sung with zeal by Dylan, Campbell, and Sexton, and the musicians are all on point, too. This opener signals that Dylan is not just here to play the hits. The selection is especially appropriate for a Sunday gathering; the song even has the line: “It was on a Sunday / Somebody touched me / Must have been the hand of the Lord.”

Dylan’s love for The Stanley Brothers runs deep. The group played the Newport Folk Festival in 1964, where Dylan was hailed as a folk hero (before being denounced as a rock traitor the following year). The Stanley Brothers set included “Man of Constant Sorrow,” which Dylan included on his debut album; “White Dove,” which Dylan has sung live 10 times; “Rank Stranger,” which Dylan released on Down in the Groove and has played live 26 times; and “Little Maggie,” which Dylan released on Good as I Been to You and has played live one time. As Bob Russell chronicles in The Dylan Review, Dylan has also included several other songs closely associated with The Stanley Brothers on his NET setlists: “I Am the Man Thomas,” “I’m Ready to Go,” “Pass Me Not O Gentle Savior,” “Roving Gambler,” and “Stone Walls and Steel Bars.” At the time, live in the moment at Bogart’s, “Somebody Touched Me” struck me as an eccentric choice for concert opener. But now I can appreciate it as a perfectly placed tribute to The Stanley Brothers, a magi’s gift delivered at the manger of the song’s nativity.

The band builds upon the Appalachian ambiance with a country rendition of “My Back Pages,” featuring some beautiful fiddling by Larry Campbell. Musically the first two songs sound compatible, but lyrically they are a study in contrasts: a testament of faith followed by a renunciation of all orthodoxies. After Dylan’s Christian conversion, his detractors sometimes hoisted him on his own petard, turning lines from this song against him: “Fearing not that I’d become my enemy / In the instant that I preached.” You might find it odd that he goes straight from an unabashed gospel song like “Somebody Touched Me” to a song that questions religious posturing in “My Back Pages.” At least, that’s what you might think if you’re familiar with the song from Another Side of Bob Dylan. But Dylan bypasses the contradiction by skipping over that verse in performance—problem solved! Perhaps Dylan had brushed up on the Gospel of Matthew: “And if thy right eye offend thee, pluck it out, and cast it from thee” (Matthew 5:29).

“My Back Pages” means something very different coming from a brash 23-year-old than from a grizzled 58-year-old. “Ah, but I was so much older then, I’m younger—I’m younger than that now!” He really leans into that refrain, and it sounds so life-affirming. Somebody touched me—must have been the voice of Bob Dylan. He accompanies his poignant vocal on “My Back Pages” with a lovely harmonica part at the end. Remember how prominently this instrument was featured in the Riverbend ’89 show? Not so here. He sets the harp down after “My Back Pages” and never picks it up again at Bogart’s.

Dylan’s pipes are in good shape tonight—not always a given on the grueling NET—and he sounds particularly sharp in this confined space. The third song proves a real vocal showcase: “Desolation Row.” Dylan only sings half of the song’s original lyrics (verses 1, 2, 3, 8, and 10), but he delivers them with panache. His phrasing is impeccable and his comic timing flawless.

When Dylan debuted “Desolation Row” at Forest Hills in August 1965, the New York audience laughed loudly and repeatedly at the song’s absurdity. You can hear why someone might react that way to the Bogart’s performance, too. His delivery is so droll on lines like “One hand is tied to the tightrope walker / The other is in his pants” and “When you asked me how I was doing / Was that some kind of joke?” Yes, actually, it is a joke, and a damn funny one if you’re attuned to Dylan’s wry sense of humor. Harry Hew gave my favorite talk at the 2023 World of Bob Dylan Conference on the topic of Dylan’s underrated humor, and this Cincinnati performance of the supposedly super-serious “Desolation Row” provides ideal support for his argument. Dylan couldn’t have picked a better spot. The building that houses Bogart’s was originally built in 1905 as a vaudeville theater. Later comics like Cheech & Chong and Billy Crystal also played the club. Dylan should feel right at home in their company.

The fourth song is a lovely mandolin-infused arrangement of “To Ramona.” The packed room is remarkably quiet while Dylan sings this song, not because we weren’t into it, but because we were totally into it. I have to think that this was a pretty rare luxury for him in the midst of a boisterous summer tour with Paul Simon, mostly at large outdoor venues. There are so many distractions of people milling about in such settings, and the sound is so diffuse in those open spaces. But this Cincinnati crowd, packed in tight and fired up to be there, also respects the artistry of Dylan’s craftsmanship on a tender tune like this.

We knew we weren’t there to hoot and holler and splash beer on ourselves, and thank God no one had smartphones yet. We were there to relish Dylan in circumstances unlike any we’d experienced before or since. When Dylan wanted to boogie, we were happy to dance along—hell, we were standing for the whole show anyway. But if he wanted to serenade us, then we had the good sense (most of the time) to shut up and listen. If you’re following on the bootleg (LB-1836), play “To Ramona” all the way to the end. There you’ll hear a woman near the taper sum up the crowd’s collective reaction: “Fuck!” Maybe someone just stepped on her toes. I prefer, however, to hear it as a holy exclamation of awe.

From the first strums it’s clear that Dylan’s next number is “Tangled Up in Blue.” I’ll take it on faith that everyone who stood in line to see Dylan adores this song, and presumably you feel the same if you’re reading this book. The line “Me, I’m still on the road/ Headin’ for another joint” gets a lot of cheers from the Cincinnati fans who never dreamt we’d see him play this particular joint. The whole evening felt like such a blessing because Dylan didn’t need to play this gig. No one would have begrudged the man for taking a night off when he had the chance. I’m sure that’s exactly what Paul Simon did after their Riverbend show was canceled. But not Dylan. He kept his appointment and delivered the goods. Who needs a day off when you get this much pleasure from working the night shift?

The video shows just how much fun Dylan is having playing guitar. Several songs include extended musical interludes, and no one grabs more of the spotlight than Dylan. In his rave review for the Enquirer, Larry Nager paid special attention to this facet of the performance:

Bob Dylan’s secret fantasy? He wants to be lead guitarist in a bar band. That’s one reason he came to Cincinnati, where last year he drew 5,000 people to Cincinnati Gardens. This year it was Bogart’s, capacity 1,464. Sunday he shouldered a Stratocaster and a Gibson acoustic and did almost as much picking as singing at his hour-and-55-minute concert at the Corryville club. (C-5)

“Tangled Up in Blue” illustrates Nager’s point, featuring some of Dylan’s most animated playing of the night. He has his mojo working below the waist, too. During the final verse and outro, the video shows off some fancy footwork, at least by Dylan standards. Bogart’s is no Radio City Music Hall, and Dylan will never be cast as a Rockette, but the nimble grandfather gets a big kick out of this song—he’s literally kicking at the end of each line. Maybe it’s his homage to Brandi Chastain. The Sunday concert fell the night after the U.S. defeated China in the 1999 Women’s World Cup final at the Rose Bowl. Like many newspapers across the globe, the front page of the Sunday Enquirer led with the famous photo of Chastain celebrating her winning penalty kick. Dylan wasn’t the only one with happy feet that weekend. The whole country was tangled up in red, white, and blue.

The final acoustic number of the first set is “Girl from the North Country,” simply one of the most beautiful songs Dylan ever wrote. I’d like to report that the audience honored “Girl from the North Country” with the same reverent awe as “To Ramona.” But the bootleg tells a different story. Some of the natives were getting restless. You can hear people stirring around in the background, going to the restroom down the hallways on either side of the stage, or burrowing through the throng to grab a drink. Those who abandoned their posts missed a breathtaking performance, so fragile, so laden with longing, with such exquisite guitar playing.

Like “My Back Pages,” “Girl from the North Country” accumulates gravitas over time. Dylan wrote this song in his early twenties, but it improves with age because it’s really meant to be sung by an older singer. The song achieves peak vintage in the autumn of the singer’s years, remembering the North Country girl he lost one too many mornings ago and a thousand miles behind. That distance in time and space, the palpable erosion of the years, the love wasted on the way, the wounds that didn’t heal—all of these elements combine to make this 1999 “Girl from the North Country” even more powerful than the beloved 1963 album version. What a wide emotional spectrum Dylan and the band cover in these first six songs. And it’s only the first set.

Second Set

There is a long pause after “Girl from the North Country.” In part the delay can be chalked up to the musicians switching from acoustic to electric. But it’s more than that. David Kemper starts counting off the next song long before the others start playing, long enough for some in the crowd to mistake him banging his sticks as a cue to the audience, so they begin clapping along in time. What’s the hold up? I think we may be hearing Dylan call an audible, deciding on the spot to play something different than what’s jotted on the players’ setlist.

When they finally start playing, it turns out to be a deep cut from Empire Burlesque (1985), “Seeing the Real You at Last.” Dylan hadn’t played this song live in over a year, before Charlie Sexton joined the band. Dylan would dial this number up only one other time in the summer of 1999, at Tramps, another small-venue gig. No one in the packed house at Bogart’s came out to hear “Seeing the Real You at Last,” but the rousing first electric song earns the biggest cheers of the night so far. I suspect this song selection in Cincinnati was deliberate and site-specific.

As I mentioned earlier, the building first housed a vaudeville theater. Later it was converted into a cinema, and by the sixties it was a popular nightspot called the Inner Circle. Al Porkolab bought the club in 1975 and transformed it into Bogart’s. In a 40th anniversary profile for local CityBeat magazine, Porkolab explained the inspiration behind the venue’s distinct name: “The real name of Bogart’s is Bogart’s Café Américain. I wanted to call it Rick’s Café Américain, because in the movie [Casablanca], when the major’s looking for Victor Laszlo, the inspector says, ‘He’ll be at Rick’s. Everybody comes to Rick’s.’ And I thought, ‘What a great tagline.’ I was sitting with a friend at [nearby restaurant] InCahoots and he went, ‘That’s way too sophisticated. No one will get that.’ I wasn’t trying to be sophisticated, I just thought it was neat” (qtd. Baker). The Bogart reference would certainly have resonated with Dylan, a huge fan of the screen legend. We know this from his many lyrical quotations from Bogart, particularly on Empire Burlesque. “Seeing the Real You at Last” contains more Bogie allusions than any other Dylan song.

John Lindley picked up on this pattern in his 1986 article for The Telegraph, “Movies inside his head: Empire Burlesque and The Maltese Falcon.” Readers and critics picked up on this thread and discovered several other lyrics lifted from the movies. “Seeing the Real You” is practically a montage of film clips. Lindley writes that he “‘would not be surprised to discover in time that the entire song . . . is constructed of lines from this medium’” (qtd. Gray 555). Although it contains quotes from Paul Newman in The Hustler and Clint Eastwood in Bronco Billy, the song’s primary source is Humphrey Bogart. In The Maltese Falcon, Bogart’s Sam Spade says, “I don’t mind a reasonable amount of trouble,” a line quoted verbatim in the song. In the same film, Spade says, “I’ll have some rotten nights after I’ve sent you over—but I’ll get over it.” On the album version of the song, Dylan sings, “Well, I have had some rotten nights / Didn’t think that they would pass.” He skips over that line at Bogart’s, but he does sing the line, “Gonna quit this baby talk now,” echoing Bogie’s line to Bacall [“Stop that baby talk”] in To Have and Have Not. In The Big Sleep, Bogart’s character asks, “What’s wrong with you?” and Bacall’s character answers, “Nothing you can’t fix.” Compare this with Dylan’s lines, “At one time there was nothing wrong with me / That you couldn’t fix.” Dylan opens the song with: “I thought the rain would cool things down / But you know it looks like it don’t.” This parrots a line from another Bogart film, Key Largo, though it is spoken by Edward G. Robinson’s character: “You’d think this rain would cool things off, but it don’t.”

The allusions to Casablanca in “Seeing the Real You at Last” are especially interesting when performed at Bogart’s Café Américain. It’s a shame that Dylan leaves out the verse that begins, “Well, didn’t I risk my neck for you.” This reference riffs on Rick Blaine from Casablanca, where Bogie’s steadfastly neutral character repeatedly declares, “I stick my neck out for nobody.” So he says. But Rick used to stick his neck out politically, running guns in Ethiopia and fighting with the Loyalists in the Spanish Civil War. He also used to put his heart on the line—that is, until he got jilted by his lover Ilsa Lund. Afterwards, Rick carefully shields himself from pain and humiliation by wearing a mask of detached cynicism. The premise of “Seeing the Real You at Last” seems modeled after Bogie’s famous line from Casablanca, “Here’s looking at you, kid.” Both song and film are fixated upon the seen and the unseen, what is revealed and what is concealed in the lover’s gaze.

Bogart first delivers his signature catchphrase in a flashback scene. Rick sulks in his closed bar, getting hammered and brooding on his long-lost “girl from the north country” (Ilsa is from Norway). He fought hard to forget her, but then she walks back into his gin joint and back into his head. Ain’t it just like the night to play tricks when you’re tryin’ to be so quiet? Memories return to haunt him from their affair in Paris before the Nazis invaded. A flashback shows the couple toasting champagne and gazing lovingly in each other’s eyes:

RICK: Who are you really? And what were you before? What did you do and what did you think? Huh?

ILSA: We said “no questions.”

RICK: Here’s looking at you, kid.

He next delivers the line as the Germans are closing in on Paris. Rick toasts Ilsa at a going away party—“Here’s looking at you, kid”—secure in the knowledge they’ll be leaving the next day to begin a new life together. She has trouble meeting his gaze in this scene because she sees what he doesn’t: they’re finished. Ilsa sends a breakup letter to Rick at the train station, abruptly abandoning him without explanation. She has learned that her husband, the freedom fighter Victor Laszlo, is not dead as she had thought, but has managed to escape the concentration camp to reunite with her. Rick is completely in the dark about this. All he knows is that the woman he loved turned out to be a rank stranger. When the mask gets ripped away, “here’s looking at you, kid” turns into “seeing the real you at last.” Rick doesn’t get his first real look at Ilsa until he sees her with Victor.

Rick wears a disguise, too. Ultimately, he drops his aloof façade by taking a noble and altruistic stand, sacrificing all future prospects with Ilsa to serve the greater good of Victor’s anti-fascist cause. As he puts her on the escape plane, Rick once again says, “Here’s looking at you, kid,” but it lands differently in Casablanca than in Paris. Now he allows her to see his real self at last, the romantic idealist hidden inside the gruff exterior he shows the rest of the world. Takes a woman like Ilsa to get through to the man in Rick. This is a big part of Bogart and Dylan’s irresistible magnetism, right? Both are adept at cracking wise and putting up impervious tough-guy fronts. But then both can melt our hearts by suddenly exposing the sweetness and vulnerability lurking behind the camouflage. It’s a dizzying metatheatrical experience to hear Dylan on stage at Bogart’s, channeling lines, scenes, and emotions immortalized on screen by Bogart in Rick’s. Play it again, Bob!

It’s also thrilling to see him perform the song with such uninhibited gusto. No one is ever going to confuse his moves for those of James Brown, Mick Jagger, or Michael Jackson. Dylan can be physically awkward on stage, all knees and elbows, Ichabod Crane in a cowboy band. But when the music gods smile upon him and he’s feeling the spirit, as he clearly is during “Seeing the Real You at Last,” he becomes a pulsar radiating joy. Go to the video (D356) and watch Dylan’s guitar jam beginning at 2:30. He plays an enthusiastic solo and then walks up to the mike as if he’s ready to sing the final verse. But he thinks better of it at 3:05 and decides he’s not finished jamming. This is where he really blasts off. Take a look at 3:20-3:45, keep on watching until the end, and judge for yourself. Have you ever seen him so unabashedly gleeful on stage? I haven’t. Oh, wait, yes, I have—I was standing there at his feet when it happened!

It goes without saying that most of the people at Bogart’s that night were big Dylan fans, and there’s nowhere on the planet we would rather have been. But even employees, who were just there punching the clock, with no prior interest in Dylan, were impressed by what they saw. Aaron Gizarra has worked at Bogart’s since 1994 and was assigned to greet the headliner when he arrived. Gizarra wasn’t a fan of the oldster’s music, but Dylan won him over that night:

I expected to see a corpse walk up, but I met him at the back door and his bodyguard came in and Dylan said, ‘Hey, how are you?’ And I was like, ‘Holy crap, that’s Bob Dylan!’ That night, I was running spotlight, and he was dancing around and I thought he was going to break a hip. He was doing Elvis twists, and at one point he did a kick that looked like he didn’t land right. But it was a two-and-a-half hour show and I was watching in amazement, and I’m not a big Dylan fan. (qtd. Baker)

The video shows Dylan regularly looking down at the fans beside the stage—seeing the real us at last!—mirroring our enthusiasm and reflecting it back tenfold. It’s a party, it’s a seduction, it’s Charlie Chaplin channeling Chuck Berry, it’s Little Richard trapped in the body of Barney Fife but wriggling his way out. Crammed into a joint that held roughly the same number of fans as the Duluth Armory, where young Bobby Zimmerman saw Buddy Holly play in 1959. Dylan fills his rockabilly hero’s shoes on “Seeing the Real You at Last,” transmitting the holy ghost to the Bogart’s faithful on this Sunday night forty years later.

There’s something else compelling about the middle part of the setlist. I didn’t pick up on it in the moment, but it becomes apparent after many listens and closer inspection. Notice the back-and-forth dynamic Dylan sets up in the first four songs of this set, alternating styles and moods, essentially pitting songs against one another. “Seeing the Real You at Last” is followed by “Lay, Lady, Lay,” Dylan’s first and only performance of this sultry honeydripper in Cincinnati.

The song is about getting laid, and its musical vibe is laid back, a major gear shift from the full-force rocker that preceded it. Lyrically, the two songs are polar opposites. “Seeing the Real You at Last” is a breakup song from the perspective of a sucker who finally sees that he’s been duped. “Lay, Lady, Lay” is a carpe diem song from the perspective of a silver-tongued seducer who likes what he sees and begs to see more: “I long to see you in the morning light”; “Until the break of day, let me see you make him smile”; “You’re the best thing that he’s ever seen.” Romeo trying to lure Juliet to his big brass bed couldn’t have laid it on thicker: “Did my heart love till now? Forswear it, sight, / For I ne’er saw true beauty till this night” (1.5.51-52). Here’s looking at you, Juliet. Love at first sight is intoxicating; love at second sight is sobering. Dylan puts those sentiments in tension with one another through his setlist sequencing.

He plays two songs that compare different ways of seeing, and then transitions into two songs that contrast going vs. staying. The bluesy rocker “Most Likely You Go Your Way (And I’ll Go Mine)” makes a claim—we’re going in different directions—which is then flatly contradicted by the folksy swinger “You Ain’t Goin’ Nowhere.” Ha! Dylan’s comic sensibilities are on display again with this clever juxtaposition. The first is a breakup song about lovers going their separate ways, the second a honeymoon song about lovers coming together with no plans of leaving their big brass wedding bed. To wrap up this four-song study in contrasts, consider this line from “Seeing the Real You at Last”: “From now on I’ll be busy / Ain’t goin’ nowhere fast.” Dylan quotes himself but turns the quotation inside out. He takes a phrase first used as a vow of fidelity (ain’t goin’ nowhere), and he repurposes it as the permanently stalled engine of a dead relationship (ain’t goin’ nowhere) without changing a word. Oh, you’re a sly one, Bob!

Let’s not get so lost in verbal gamesmanship, however, that we fail to appreciate the musical triumph of “You Ain’t Goin’ Nowhere.” Dylan played 117 concerts in 1999, but he only performed this song three times. It’s a special gift for the Cincinnati audience, and it sounds like a treat for the band to play. Campbell lays the foundation with his fiddle, setting that chair rocking on the porch before the action moves inside. He and Sexton join with backing vocals on the exuberant refrain:

Whoo-ee! Ride me high

Tomorrow’s the day

My bride’s gonna come

Oh, oh, are we gonna fly

Down in the easy chair!

I love the collaborative chemistry here. It’s a fool’s errand to try and harmonize with Dylan, so Campbell and Sexton don’t even try. They go high and harmonize with each other; meanwhile, the boss goes low and does his own thing. The results are uplifting, whether you were standing at the foot of the stage in 1999 or sitting in your easy chair years later listening to the bootleg.

“You Ain’t Goin’ Nowhere” is one of the brightest numbers of the evening, so dualistic Dylan follows it with “Not Dark Yet,” the most somber song from his darkest album Time Out of Mind. This was his first performance of the song in Cincinnati, and he makes it a memorable one.

Now that I’m besotted with Bogie, the song conjures up images for me from Casablanca. “Not Dark Yet” captures Rick’s desolation at his low point, hunched over a bottle rotgut in the dark, torturing himself by listening to “As Time Goes By.” [Dylan sings a gorgeous cover of this song on Triplicate (2017).] “You must remember this . . .” Oh, he remembers!

Shadows are falling and I’ve been here all day

It’s too hot to sleep, time is running away

Feel like my soul has turned into steel

I’ve still got the scars that the sun didn’t heal

The song jibes with the jaded cynicism of a disaffected exile: “Well, my sense of humanity has gone down the drain / Behind every beautiful thing there’s been some kind of pain.”

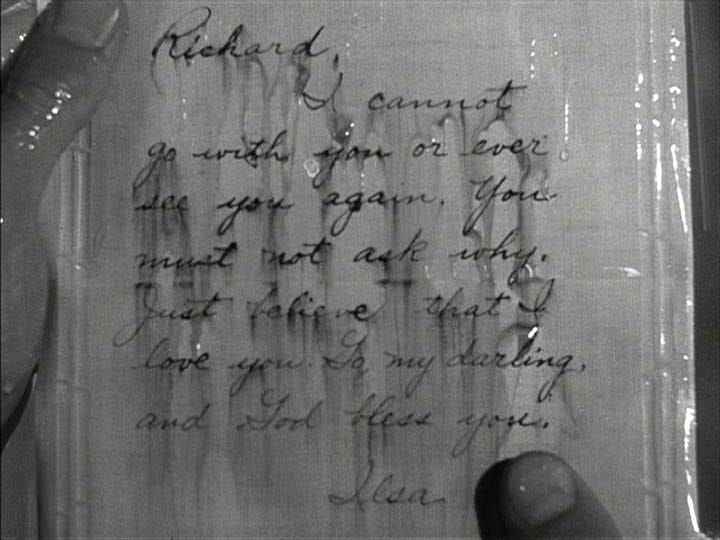

There are even little details that link the singer’s experiences in “Not Dark Yet” to those of Rick in Casablanca. Dylan sings, “She wrote me a letter and she wrote it so kind / She put down in writing what was in her mind.” Ilsa writes Rick a fateful letter, too. It is more cruel than kind, and conceals more than it reveals, but it gets the job done: “I cannot go with you or ever see you again. You must not ask why. Just believe that I love you. Go, my darling, and God bless you.”

How’s that for you go your way and I’ll go mine? He goes to the ends of the earth to escape her memory, but it doesn’t work. The groom’s still waiting at the altar. “I know it looks like I’m moving, but I’m standing still.” He ain’t goin’ nowhere.

His ass may be planted in Casablanca, but he left his heart in Paris. “We’ll always have Paris,” Rick tells Ilsa in their tearful farewell at the film’s conclusion. “Well, I’ve been to London and I’ve been to gay Paree,” Dylan sings in “Not Dark Yet.” Paris was the City of Light for Rick and Ilsa; London was the city of Blitzkrieg. During Major Strasser’s first conversation with Rick, the Nazi officer tries to goad the American expatriate into revealing his true loyalties:

STRASSER: Are you one of those people who cannot imagine the Germans in their beloved Paris?

RICK: It’s not particularly my beloved Paris.

STRASSER: Can you imagine us in London?

RICK: When you get there, ask me.

To be clear, I’m not arguing that Dylan had Casablanca consciously in mind when writing “Not Dark Yet.” These echoes are probably accidental rather than intentional, but they’re no less evocative for that. What I’m reveling in here is the art of intertextuality and juxtaposition, where context creates new meaning. When Dylan plays a song at a certain place and time, it accrues layers of significance it would not have elsewhere. “Not Dark Yet” is a different song played at Bogart’s than at any other gin joint in any other town in all the world.

The circumstances behind this impromptu show even manage to give a comic twist to an otherwise brooding line from “Not Dark Yet.” Dylan sings, “I can’t even remember what it was that I came here to get away from.” Ah, sure you do, Bob—you came here to get away from Paul Simon!

I’m sure that zinger is just a happy accident, but it fits with Dylan’s joking mood throughout Bogart’s ’99. The most overt example comes during the band introductions.

“On the other guitar is Charlie Sexton. Charlie went over to the Hamilton County jail today to see his cousin, bring him a cell phone. [Kemper plays a rimshot.] He just about made it back for the gig.” Cheesy, sure, but at least he made the effort to localize the gag. The Hamilton County crowd laughs along, and so do the ghosts of vaudevillian performers who first played this room.

The last song of the second set is a raucous “Highway 61 Revisited.” This one is a dependable crowd-pleaser. The performance stands out at Bogart’s for reasons somewhat detectable on the audio bootleg, but most obvious on the video bootleg.

Throughout the second verse, Charlie Sexton keeps holding his guitar weirdly, like he’s trying to hear some distracting noise his instrument is making (or failing to make). The videographer tightens the frame during the third verse so Sexton is cut out. At the 2:00 mark of the video, Dylan looks over his left shoulder, and Campbell matches his gaze. The camera pans out and we see what has their attention: a tech guy is on stage working on Charlie’s guitar while he’s still playing it!

I’ve never seen such a thing—except that I must have. I retain zero memories of it, even though I was standing right there at the time. Maybe that’s because, in an effort to redirect the audience’s attention away from this fiasco, the rest of the band compensated by thrashing away on an extended jam. Poor Charlie never got that axe working right for the rest of the song, though occasionally he plays a few test notes that sound like someone assaulting a goose. Fortunately, this is a group effort, and the rest of the team rallies to pick up the slack, blotting out the technical difficulties entirely from this fan’s recollection. It’s a shambles, really, but it’s fast and loud, and maybe that’s the main objective. I was too busy speeding down Highway 61 to rubberneck at the new guitarist stranded on the side of the road.

Encores

The band exits after finishing their twelfth song but soon returns for the first of three encores. First up is “Love Sick,” the opening track from Time Out of Mind. Songs from TOOM have featured prominently in Dylan’s concerts ever since the album dropped, none more so than “Love Sick.” He has performed the song live 941 times, making it his twelfth most played song in concert. This is quite remarkable for a song that didn’t come out until 1997, 35 years into his career. Note that 9 of the top 12 were released in the sixties, and only “Things Have Changed” has been played more (1,030) despite coming out later (2000).

The theme of an outcast traveling the fallen world in pursuit of his lost love is the classic stuff of myth and legend, and right in the wheelhouse of a wandering minstrel like Dylan. “I’m walking through streets that are dead / Walking, walking with you in my head.” Hell, it could just as well be Orpheus on the trail of Eurydice. The journey through a blasted wasteland may be a physical one, but it is also a psychological voyage into the singer’s heart of darkness. It’s a portrait of deranged, insatiable desire. The singer—not Dylan, mind you, but the character he portrays—seems capable of just about anything to get his lover back: “Just don’t know what to do / I’d give anything to beeEEEeee with youuuu!”

If 941 performances of “Love Sick” is impressive, then what do we make of the 2,109 performances of “Like a Rolling Stone”? What Dylan makes of it at Bogart’s is frankly a bit of a mess. Its sin is its lifelessness, to borrow the description of Ophelia in “Desolation Row.” The singer sounds like he’s reaching for a new handle on an old song but can’t quite grasp it. There’s a high floor on a song this great, meaning there’s a limit to how low Dylan can go. But for most of the song he dwells closer to the floor than the ceiling.

Then something changes. Dylan revives. In the final verse he takes what had been a mediocre rendition and spins straw into gold. After being on autopilot for six minutes, the captain is jolted awake, grabs the wheel, switches off autopilot, and pulls back on the throttle. The musical interlude before the last verse marks the transition. The audience is the defibrillator. You can see it happening on the video. Dylan keeps looking at the fans up front, responding to our enthusiasm, getting into his playing more, smiling at the supporters urging him onward. He rides the wave of encouragement and feeds off the love to fuel him through a revitalized final chorus. The Bogart’s audience engineers a Peter Pan moment by clapping Tinker Bell back to life.

A dozen songs plus an encore of two more, culminating with “Like a Rolling Stone”—show’s gotta be over, right? But praise be to Nero’s Neptune, Dylan and his crew set sail for more. After the electric crescendo of “Like a Rolling Stone,” the band pivots to acoustic diminuendo to open the second encore. It takes a minute to recognize the musical intro, but when Dylan implores, “Go ’way from my window . . .” it becomes clear we’re to be blessed with a divine “It Ain’t Me, Babe.”

I’m continually amazed by Dylan’s talent for reconnecting with the wellspring of his greatest songs after so many years and several hundred performances. He sings “It Ain’t Me, Babe” with the fresh commitment of a piece written last night on the tour bus. This chameleon of a song comes in many colors, sometimes spiteful, sometimes condescending, sometimes a cunning rebuttal to The Beatles’ “She Loves You” (“no, no, no” for “yeah, yeah, yeah”). Tonight Dylan opts for a tender, wounded, regretful lament, which is how I like it best.

“It Ain’t Me, Babe” is another song so harmonious with the emotional cosmos of Casablanca that you could imagine Bogie speaking the lines as easily as Dylan singing them. The singer ruthlessly examines his relationship with a woman and unsparingly concludes that they’re wrong for each other. “I’m not the one you want, babe / I’m not the one you need”; “I will only let you down”; “You say you’re lookin’ for someone / Who will promise never to part”; “Someone who will die for you an’ more / But it ain’t me, babe.” Much as he hates to admit it, he’s not the man for her. This is the same heart-rending message Rick delivers at the Casablanca airfield. It ain’t me you’re lookin’ for, Ilsa—it’s Victor. She resists at first: “You’re saying this only to make me go.” But this isn’t payback for the Paris brushoff [“Go, my darling”]. He isn’t dumping her, no, no, no, he’s facing the hard fact that she’s better off with someone else. “I’m saying it because it’s true. Inside of us we both know you belong with Victor. You’re a part of his work, the thing that keeps him going. If that plane leaves the ground and you’re not with him, you’ll regret it. Maybe not today, maybe not tomorrow, but soon, and for the rest of your life.”

Oof! Gets me every time I watch it. And that’s exactly the same feeling I get every time I listen to Dylan nail a performance of “It Ain’t Me, Babe” like he does at Bogart’s.

Just when you think it can’t get any better, it does. The next song in the second encore is my absolute favorite performance of the evening. Dylan and his posse gird themselves for battle with electric instruments and mow down the crowd. Kemper and Garnier begin stomping out a galloping thump, then Dylan, Campbell, and Sexton charge the mikes and belt out—

I’m a-gonna tell ya how it’s gonna be

You’re gonna give your love to me

I’m gonna love you night and day

Ya know my lovin’ not fade away

What!? “Not Fade Away” by Buddy Holly and The Crickets. There have been some great covers of this song over the years, particularly by The Rolling Stones and The Grateful Dead, but the Bogart’s performance is so rapturous, so charged with ecstatic joy, that I’ll put it up against any other version. Dylan had a resurgence of interest in Buddy Holly in the late nineties, and he covered him a lot in 1999, regularly playing “Not Fade Away” in his own sets and frequently singing a duet with Paul Simon on “That’ll Be the Day.” Thankfully I knew nothing about this in advance, being blissfully ignorant of bootlegs and setlists back in those days.

Dylan, Campbell, and Sexton attack the song like gunslingers at the O.K. Corral. It is so GREAT! The playing is grungy and the singing is mush-mouthed, but those imperfections just serve to validate its legitimacy as the real thing, old school Rock & Roll, created in a reckless big-bang instant, but also leaving a lasting mark. The song is simultaneously of its moment and timeless—which is to say that it fulfills the pledge to not fade away. The band declares with bold swagger that they’re gonna make us love them with a passion that won’t fade away. I can testify almost a quarter-century later that those words still ring true. Even without the aid of audio or video bootlegs, this performance glows like burning coal in my memory across the gulf of time. The enduring vitality of Holly’s “Not Fade Away” for Dylan, and Dylan’s “Not Fade Away” for me, calls to mind Shakespeare’s Sonnet 18 (“Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?”) about a love that deepens over time rather than fading away:

But thy eternal summer shall not fade,

Nor lose possession of that fair thou ow’st;

Nor shall death brag thou wander’st in his shade,

When in eternal lines to time thou grow’st:

So long as men can breathe or eyes can see,

So long lives this, and this gives life to thee.

I’ve written so much about Bogie, but Buddy is another major influence on the Bogart’s show. Each icon represents the kind of artist Dylan aspired to become when he dedicated his life to performance. When he accepted his Grammy in 1998, he mentioned Holly as a presiding spirit over the Time Out of Mind sessions. “I just want to say that one time when I was about sixteen or seventeen years old, I went to see Buddy Holly play at, I don’t know, Duluth National Guard Armory, and I was three feet away from him, and he looked at me. And I just have some sort of feeling that he was—I don’t know how or why—but I know he was with us all the time we were making this record in some kind of way.”

Years later, in his lecture for the 2016 Nobel Prize in Literature, he elaborated at length on the importance of Holly as a performer, and he portrayed that 1959 Duluth concert as if it were Saul’s conversion on the road to Damascus:

He was the archetype. Everything I wasn’t and wanted to be. I saw him only but once, and that was a few days before he was gone. I had to travel a hundred miles to get to see him play, and I wasn’t disappointed. He was powerful and electrifying and had a commanding presence. I was only six feet away. He was mesmerizing. I watched his face, his hands, the way he tapped his foot, his big black glasses, the eyes behind the glasses, the way he held his guitar, the way he stood, his neat suit. Everything about him. He looked older than twenty-two. Something about him seemed permanent, and he filled me with conviction. Then, out of the blue, the most uncanny thing happened. He looked me right straight dead in the eye, and he transmitted something. Something I didn’t know what. And it gave me the chills.

Glory, glory, glory, somebody touched me! Dylan believes a mystical energy transfer took place at the Duluth Armory that night. The doomed Texan gazed down at the Minnesota kid and tapped him as his apostle and heir-apparent, charged with carrying the torch forward. Dylan accepted this mission and has kept the faith, sharing the way, the truth, and the life through music with audiences all over the globe for decades.

“Not Fade Away” circles back to the concert opener “Somebody Touched Me.” In their separate but related ways, both are musical expressions of connection and transcendence. Both performances feature Dylan, Campbell, and Sexton singing in unison across the footlights to fans staring back with the same adoration that Bobby Zimmerman had for Buddy Holly. The songs speak to each other, and they speak to the listener. Dylan felt touched by the holy spirit of rock & roll in 1959. His musical ministry has evolved significantly over the years, but his vocation, his sense of a calling, has never wavered. He lights another candle and converts another congregation at Bogart’s in 1999.

The concert could easily have ended after “Not Fade Away” and Dylan would have sent everyone home satisfied. But he comes back out for a third encore, and the final song of the evening is a monumental one: “Blowin’ in the Wind.” Dylan was only 22 years-old when he wrote this song, the same age as Holly when he died. Out of the hundreds of songs Dylan has composed, “Blowin’ in the Wind” has as strong a claim for immortality as any. Centuries after he’s gone, this song will still be sung—it will not fade away.

Dylan gives an emotional delivery to the secular hymn, accompanied by Campbell and Sexton on the refrain: “The answer, my friend, is blowin’ in the wind / The answer is blowin’ in the wind.” The song is concrete enough to proclaim solidarity with the persecuted, but broad enough to be universally applicable in a variety of cultural and historical contexts.

Lyrically, it’s hard to deduce a political agenda or action plan from the song. “The answer is blowin’ in the wind”—what precisely does that mean? Are the answers to humanity’s perennial problems finally within reach, or must they remain perpetually elusive? Is “Blowin’ in the Wind” a principled manifesto or a vague dodge?

Interestingly, the title phrase is uttered in Casablanca by the most ethically ambivalent character in the film, Captain Louis Renault, played with incorrigible charm by Claude Rains. When Major Strasser questions the allegiances of the corrupt Casablanca police chief, their exchange sounds like Pete Seeger confronting Bob Dylan after the 1965 Newport Folk Festival:

STRASSER: Captain Renault, are you entirely certain which side you’re on?

RENAULT: I have no conviction, if that’s what you mean. I blow with the wind, and the prevailing wind happens to be Vichy.

Not so inspirational when you put it like that, eh? Louis’s “Blowin’ in the Wind” sounds less like “We Shall Overcome” and more like “Won’t Get Fooled Again.”

But if you’re trying to make sense of “Blowin’ in the Wind” through intellectual interrogation, then you’re asking the wrong questions. The song’s appeal has always been visceral and musical, a power that resides chiefly in live performance. Ask Larry Campbell what this anthem means, and you’ll get closer to the heart. In an interview with Jeff Giles, Campbell recalled what it felt like to play “Blowin’ in the Wind” on stage with Dylan:

I remember a particularly good show with Bob Dylan where the set was paced really well and he was right on and everything was doing good. Huge crowd right there with us. And at the end of the show, we did, for the first time that I played with him, a version of “Blowin’ in the Wind.” You know, this song, when I was a kid, this song was everywhere. It was the anthem of my exposure of the modern folk movement that was going on at that time. I’m talking about a young kid here—6, 7, 8, around that. And that tune, for many reasons, it was a huge part of musically driving me to where I got to. What it meant lyrically, the melody, and how it brought people together and its role in the civil rights movement back then. And this one night, we ended the show with that song, and it was done in such an emotional way on everybody’s part—Bob and everyone in the band. It sort of left the audience stunned. And we finish the tune and I’m just thinking, man, I have arrived! This is the completion of a circle for me, because I was affected by something like this from its source, and now I’m at that source.

I’m no musician, but I shared the experience Campbell describes from the receiving end, down in the mosh pit at Bogart’s, mere feet away from the source.

In his Enquirer concert review, Larry Nager described the scene at Bogart’s as “a very small space with a fanatical crowd that really, really wanted to be there. . . . Because the show was general admission, the people in the front row weren’t there because they could afford scalpers’ prices; they were there because they’d been waiting outside the club since early Sunday morning” (C-5). As the band closed their Sunday evening service with “Blowin’ in the Wind,” the Cincinnati flock rejoiced. This is what we came here for. Dylan brought us back to the source, he took us to the river and washed us in the water. We filed out slowly, drenched in sweat and renewed in our musical faith. I said it heading in, and it bears repeating at the exit door:

Of all the gin joints in all the towns in all the world, I’m glad Dylan walked into mine.

Works Cited

Baker, Brian. “We’ll Always Have Short Vine . . . .” CityBeat (22 July 2015), https://www.citybeat.com/news/we-ll-always-have-short-vine--12175168.

The Big Sleep. Directed by Howard Hawks. Warner Brothers, 1946.

Björner, Olof. Still on the Road, https://www.bjorner.com/Artist%20index%20top%20100.htm.

“Bob Dylan Playing Bogart’s,” Cincinnati Post (25 June 1999): C1.

Brinkley, Douglas. “Bob Dylan Has a Lot on His Mind.” New York Times (12 June 2020), https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/12/arts/music/bob-dylan-rough-and-rowdy-ways.html?action=click&module=Top%20Stories&pgtype=Homepage.

Casablanca. Directed by Michael Curtiz. Warner Brothers, 1942.

Crowe, Cameron. Biograph Liner Notes (1985). Every Mind Polluting Word: Assorted Bob Dylan Utterances, ed. Artur Jarosinski. Don’t Ya Tell Henry, 2006.

D356. Bootleg Video Recording. Taper unknown. Bogart’s, Cincinnati (11 July 1999).

Dylan, Bob. Acceptance Speech for Grammy for Album of the Year (25 February 1998). The Grammys. https://www.grammy.com/grammys/news/40th-grammys-who-won-big-four-categories.

---. “Nobel Lecture in Literature.” The Nobel Prize (4 June 2017). https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/literature/2016/dylan/lecture/.

---. Official Song Lyrics. The Official Bob Dylan Website,

http://www.bobdylan.com/.

Giles, Jeff. “Larry Campbell Shares Memories of Bob Dylan, Phil Lesh, Hot Tuna, Paul Simon and More: Exclusive Interview.” Ultimate Classic Rock (14 May 2015), https://ultimateclassicrock.com/larry-campbell-2015-interview/.

Gray, Michael. Song & Dance Man III: The Art of Bob Dylan. Continuum, 1997.

Hewitt, Harrison. “‘How Long Can We Falsify and Deny What Is Real’: Bob Dylan is the Funniest Person Alive, and Why We Need to Talk About It.” The Dylan Review 5.1 (2023), https://thedylanreview.org/2023/08/26/world-of-bob-dylan-how-long-can-we-falsify-and-deny-what-is-real-bob-dylan-is-the-funniest-person-alive-and-why-we-need-to-talk-about-it/.

Key Largo. Directed by John Huston. Warner Brothers, 1948.

LB-1836. Bootleg Audio Recording. Taper unknown. Bogart’s, Cincinnati (11 July 1999).

The Maltese Falcon. Directed by John Huston. Warner Brothers, 1941.

McKay, Alistair. Interview with David Kemper. Uncut (24 October 2008), https://www.uncut.co.uk/features/bob-dylan-behind-the-scenes-of-tell-tale-signs-part-12-37864/.

Nager, Larry. “Dylan gives Bogart’s crowd peek at legend.” Cincinnati Enquirer (13 July 1999): C-5.

Padgett, Ray. “Larry Campbell Goes Deep on His Eight Years with Bob Dylan.” Flagging Down the Double E’s (31 March 2021),

.

Russell, Bob. “Bob Dylan and the Stanley Brothers.” The Dylan Review 4.1 (Spring/Summer 2022), https://thedylanreview.org/2022/08/04/bob-dylan-and-the-stanley-brothers/.

Shakespeare, William. Romeo and Juliet. Arden Shakespeare Third Series. Ed. René Weiss. Methuen, 2012.

---. “Sonnet 18: Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?” Poetry Foundation, https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/45087/sonnet-18-shall-i-compare-thee-to-a-summers-day.

Sounes, Howard. Down the Highway: The Life of Bob Dylan. Grove Press, 2001.

To Have and Have Not. Directed by Howard Hawks. Warner Brothers, 1944.

It's taken me so long to finally sit down and take this instalment in. But it's very much worth taking the time to listen to the songs and watch the videos alongside reading the text. The way you compose these pieces, as a mixture of histories is remarkable – not only do we can a real impression what the context of Bob Dylan’s life and career was, but you also bring in the story of your city, the lives of the musicians playing with Dylan, and of course your own biography. It’s such a unique and special reading experience that truly shows just how much Dylan’s performances impact his audiences worldwide, both individually and collectively. This really looks like such a special show, and I’m so glad that you were in attendance, because as amazing as recordings and videos are, they are always more impactful when shared alongside an eye witness report (we are SEEING through you, in keeping with the themes of the songs).

Listening to the recordings from this show, it also struck me how Dylan’s instrumentation and the roots-y feel of the Larry & Charlie band lineup anticipated the shift in popular music that was soon to take place after the release of the O Brother Where Art Thou soundtrack the following year (produced and curated by T-Bone Burnett of course).

What I think is hilarious about Dylan's guitar moves in Tangled Up in Blue is that I’m pretty sure the dominant guitar solo we’re hearing is coming from Charlie, so it almost looks like Dylan is miming or playing air guitar (I’m sure he was really playing, but his guitar is way down in the mix - you hear him a little better after the 3.20 mark).

Speaking of Charlie's playing, I loved watching that video of Highway 61, and I'm intrigued what happened. I assume the strap came loose, but not sure why that would require the guitar tech screwing something back on? Maybe the strap button (I'll ask Robert)? But I don’t think it was anything that impacted the sound of the instrument, because I’m pretty sure that's Charlie playing the wailing solo WHILE the tech was working on his guitar! The show must go on I suppose!

Thank you for this Graley, your Substack has been such a vital addition to the Dylan world this year, and it's very much appreciated!