Dylan Context

If you only look at Dylan’s recorded output, the year 2000 doesn’t stand out as special. But important new projects like the album “Love and Theft” were gestating, the Never Ending Tour was peaking as it crisscrossed North America and Europe multiple times, and developments off stage cast foreshadows, if only visible with the benefit of hindsight.

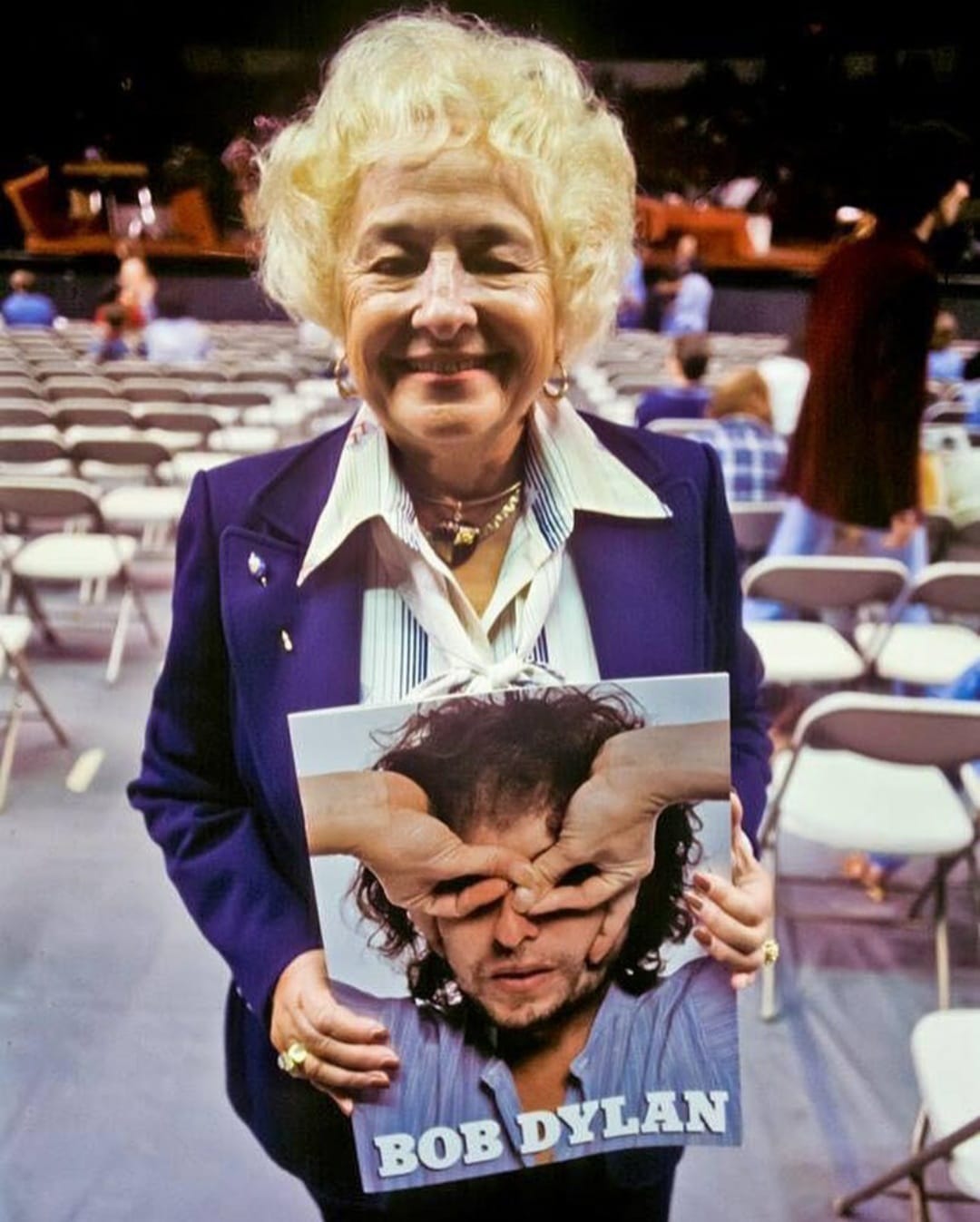

The year got off to a miserable start with the death of Dylan’s beloved mother. His father Abe Zimmerman died of a heart attack in 1968 at the relatively young age of 56. His mother Beatrice Stone Zimmerman (later Rutman) outlived her first husband by over three decades, dying on January 25, 2000, at the age of 84. Beatty (pronounced BEE-tee) was her son’s biggest supporter. “My mom, bless her,” wrote Dylan in Chronicles, “had always stood up for me and was firmly on my side in just about anything and everything” (226).

Robert Shelton, Dylan’s authorized biographer, visited the Zimmermans shortly before Abe’s death, and he learned that young Bobby was unabashedly a mama’s boy. Beatty shared a touching twelve-stanza poem her son wrote for her on Mother’s Day, and Shelton quotes the conclusion:

My dear mother, I hope that you

Will never grow old and gray,

So that all the people in the world will say

“Hello, young lady, Happy Mother’s Day”

Love, Bobby. (Shelton 34)

Sweet, right? It reads like his first draft of “Forever Young.” She occasionally appeared in public to support her son, as when she went on stage during the Rolling Thunder Revue concert in Toronto in 1975, or when she appeared by his side during his Kennedy Center Honors in 1997. Mostly, however, she was a quiet, stable, proud, loving presence in the background of her famous son’s life, keeping the home fires burning in Minnesota.

Dylan generally preferred to keep his grief private. According to interviewer Dave Fanning in 2001, “He’s been quoted as saying that ‘even to talk about my mother just about breaks me up.’ Best leave it at that” (1263). In the song “Lonesome Day Blues,” released on “Love and Theft” the year after Beatty’s death, he sings, “I wish my mother was still alive.” Perhaps he regretted revealing even this much, since the line is omitted from the official published lyrics. Song would continue to be a place for Dylan to process his deepest feelings of love and loss, movingly but obliquely, as we shall soon see from his concert at Cincinnati’s Riverbend Music Center in 2000.

Dylan must have been working on material for “Love and Theft” throughout much of the year, but he kept those original compositions close to the vest. He did release one new song in 2000, however, and it was a monumental one: “Things Have Changed.” Director Curtis Hanson asked Dylan to contribute to the soundtrack for his new film Wonder Boys, and, after screening a rough cut, Dylan agreed. The movie includes multiple Dylan songs, but the standout is “Things Have Changed.” Dylan released the song as a single, and he used it as the closer for his new greatest hits package The Essential Bob Dylan. He debuted the song live in March 2000, and it has become a warhorse in his setlists ever since, performed in over a thousand concerts. “Things Have Changed” went on to win the Academy Award and the Golden Globe for Best Original Song. Dylan has a sketchy relationship with awards, but, as a lifelong film buff, he seems genuinely proud to have won an Oscar. We know this because for years he brought his trophy with him on tour and prominently displayed it on stage.

Speaking of awards, Dylan was recipient of the Polar Music Prize in 2000. The award was founded by Stig Anderson, manager and lyricist for ABBA. It honors highly accomplished musicians in a variety of genres “for significant achievements in music and/or musical life, or for achievements which are believed to be of great potential importance for the advancement of music and/or musical life.” So much was made of Dylan’s conspicuous absence from the Nobel Prize ceremony in 2016, but he may well have had a “been there, done that” attitude about the affair. He was touring Europe in the spring of 2000 and had a day off after his May 14 show in Göteborg, Sweden. He attended the Polar Music Prize ceremony on May 15 at Berwaldhallen in Stockholm, where he was presented with the award by King Carl XVI Gustaf.

Seeing a visibly uncomfortable Dylan standing there with his framed certificate and a giant potted plant (no kidding), it’s easy to understand why he passed on a return visit and repeat performance sixteen years later. He didn’t stick around for the musical celebration afterwards, escaping to Helsinki where he had a concert the following night. Interestingly, though, he did have a proxy in attendance, Bryan Ferry, who sang “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall.” Foreshadows once again of 2016 Stockholm, where Patti Smith (2011 recipient of the Polar Music Prize) substituted for Dylan with the same song at the Nobel ceremony.

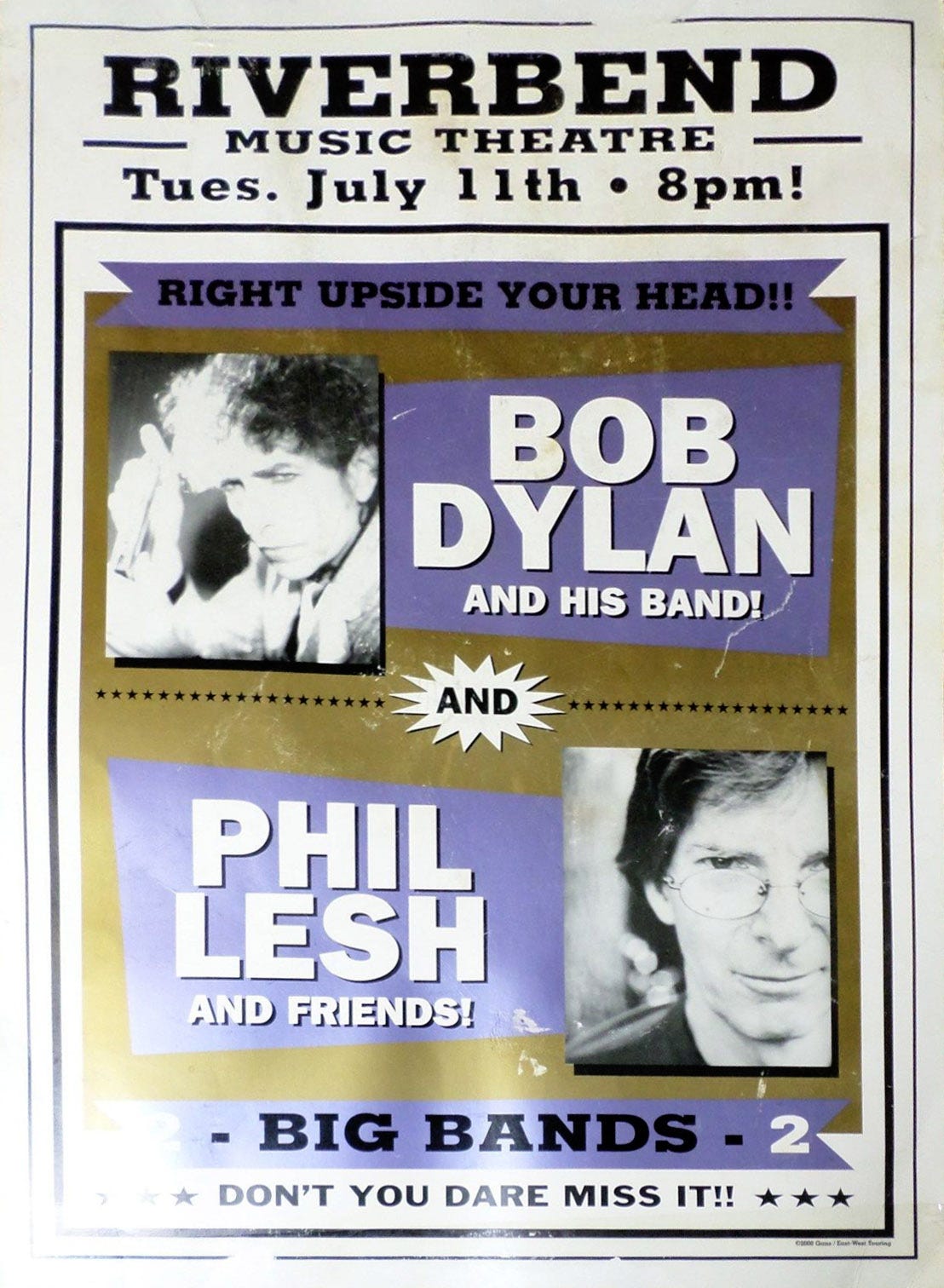

His primary focus during this period was on touring. In 1999, the band performed 119 concerts, the most Dylan ever played in a single year. He was nearly as active in 2000, with three legs of the NET in North America and two in Europe, for a total of 112 concerts. He ended 1999 on tour with Phil Lesh and Friends, and they teamed up again in the summer of 2000, including a stop at Cincinnati’s Riverbend. Lesh was the longtime bassist for The Grateful Dead. Dylan and the Dead were huge mutual admirers. The Dead regularly included Dylan songs in their setlists, and their intense fan culture and steadfast commitment to touring were key inspirations for the Never Ending Tour. Dylan has credited the Dead with reigniting his passion for live performance in the mid-eighties, and as recently as 2023 he paid his respects with several Dead covers in concert. After the death of bandleader Jerry Garcia in 1995, the remaining members formed various spinoff bands. The lineup of Phil Lesh and Friends (later Phil Lesh Quintet, later still Phil & Friends) evolved over the years. The group he brought to Cincinnati featured members from Little Feat. These merry pranksters unhitched their wagons at Riverbend on July 11, 2000, exactly one year to the day after the 1999 Bogart’s show. I was in England on a research grant to study at the Beckett Archives in Reading, so I couldn’t attend Riverbend ’00 and have only the bootleg (LB-6963) to go by. I imagine that the confluence of fans devoted to Dylan, the Dead, and Little Feat made for a groovy atmosphere down by the banks of the Ohio.

I hope those who made it to the show arrived early. Out of the twenty concerts he has played in the Cincinnati area since 1965, this is the only one where Dylan was the opening act. Cincinnati Enquirer music critic Chris Varias started off his concert review by puzzling over this decision:

The only two people Bob Dylan should have to bequeath the headlining slot to are Hank Williams and Howlin’ Wolf, and they’re both dead. Yet there he was at Riverbend Tuesday, taking the stage at 7:08 p.m. with the sun still shining, more than two hours before Grateful Dead bassist Phil Lesh would begin his headlining set. That just makes Mr. Dylan the world’s best opening act. (Varias E-5)

How does one go from accepting the Polar Music Prize from the King of Sweden in May to serving appetizers for Phil Lesh in Cincinnati in July? My good friend Rob Reginio, who saw multiple shows on this tour, helps shed some light. According to Rob, Lesh had an elaborate light show for his concerts. Therefore, whenever the tour was booked at an outdoor venue like Riverbend, Dylan did his old pal the courtesy of going on first, before sunset, so that Lesh could have the darkness he needed to shine at his brightest. Classy move. You’re a mensch, Bob.

Cincinnati Context

If you were wandering leisurely among the concert crowd that pleasant summer night, you probably would have had no inkling that the city was about to endure the most troubling chapter in its modern history. However, if you were a resident of Over-the-Rhine, Avondale, or Evanston, then you could have seen it coming. Cincinnati was a powder keg waiting to explode. The spark was lit on April 7, 2001. That night, police officers pursued Timothy Thomas, a 19-year-old African American with a number of warrants against him for misdemeanor charges. Thomas was confronted in an alley in Over-the-Rhine by Stephen Roach, a white Cincinnati police officer, who shot and killed the unarmed teen. Thomas became the 15th Black man to die in confrontations with Cincinnati police officers since 1995.

Relations between the Cincinnati police and the Black community were abysmal, characterized by mutual distrust, corrosive tension, and sometimes open hostility. In 1999, Minister Bomani Tyehimba filed a lawsuit against the CPD, accusing the department of discrimination and racial profiling of African Americans. Other local groups joined the lawsuit, including the ACLU and the local activist group Black United Front. But things only got worse. When Timothy Thomas was shot in April 2001, he became the fifth Black man to die in police custody in Cincinnati since October 2000. The conditions were in place for what is commonly referred to as the Cincinnati Riots of 2001, the most difficult and heartbreaking experience in the city’s civic life since I’ve lived here.

A couple hundred protesters staged a rally at Fountain Square and attended a contentious City Council meeting at City Hall on April 9. The civil unrest soon spilled into the streets, and what started as peaceful protests turned destructive at times (e.g., assault, fires, vandalism, looting), especially in Over-the-Rhine but in other pockets of the city, too. Mayor Charlie Luken declared a state of emergency and announced citywide curfews. The unrest lasted for five days and did not ease up until Timothy Thomas’s funeral on April 14, the day before Easter.

If you want to understand what happened in Cincinnati at that time, including eyewitness accounts and expert reflections on the buildup and aftermath of the uprising, I highly recommend the film Cincinnati Goddamn. It’s tough to watch, filled with brutality, injustice, rage, and grief. I hurt for my city of ruin when I watch Cincinnati Goddamn: for the families of those who lost loved ones, and for the communities that have long endured biased and inequitable treatment by the legal system. That said, it should be mandatory viewing for all Cincinnatians, or anyone else who wants an inside perspective on the so-called Cincinnati Riots. The film was directed by April Martin and Paul Hill, is named after the great protest song “Mississippi Goddamn” by Nina Simone, and is freely available for streaming through the Wexner Center for the Arts website.

There are a lot of disturbing and eye-opening moments captured in the film, but some of the most wrenching feature Thomas’s mother, Angela Leisure. In a somber interview, she recalls moving her family to Cincinnati:

As a parent, you expect to outlive your children. You expect your children to bury you. You don’t expect to bury them. And then for me to save my children’s lives by moving them from Chicago to here, which I thought was a safer, better place. And then to bring him here to be killed? It’s almost . . . It’s almost unthinkable.

Leisure seems still in shock during that interview, but she is fired up with righteous fury at the City Council meeting on April 9. She directly confronts council members and CPD Police Chief Tom Streicher, demanding accountability. “If you’re sorry, tell me why my son was killed? If you are sorry, tell me why my son was killed!? Why was these other parents’ sons killed, if you so sorry? Show me how sorry you are, because we wanna know!” She then grips the hand of her surviving son, looks the city leaders dead in the eye, and says: “This is my other son. I know he has a ticket. Is he gonna die too?”

Devastating. Mothers and mourning will become recurring themes in a different context when we turn our attention to Dylan’s 2000 concert.

Reverend Damon Lynch III, leader of the Black United Front, diagnosed the central conflict behind the unrest this way:

The problem is, when we look at the same picture, we don’t see it the same way. We can look at the Timothy Thomas shooting. What does Cincinnati do? It divides. White Cincinnati says, “Why did he run?” Black Cincinnati says, “Why did they shoot him?” And until white America can see what the Latino community sees, or what the Black community sees, and that’ll never happen unless they are immersed in our culture the same way we had to be immersed in theirs, then we’ll continue to divide along lines of race while looking at the same picture.

Attorney and civil rights activist Michelle Alexander, author of The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness, places the Cincinnati problem in a larger national and moral context:

At the root of all this is the failure of us as a nation to extend genuine care, compassion and concern to people of other races, of other classes. That was the central birth defect of our nation that Dr. King talked so eloquently about, Ella Baker, Sojourner Truth. Viewing some of us as less than human, as unworthy of genuine care, compassion and concern. The same rights, treatment, care you would give to your own neighbor or your own friends. That’s at the core of all of this. And we can by coming together and doing courageous forms of advocacy and organizing in our own communities, create a moral consensus.

It must be said that, in certain respects, Cincinnati learned lessons from the 2001 unrest and made some tangible progress. A diverse group of stakeholders painstakingly negotiated a Collaborative Agreement, jointly approved by Mayor Luken, Police Chief Streicher, representatives of the ACLU and the Black United Front, U.S. District Judge Susan Dlott, and the U.S. Department of Justice, which led to police reforms and a greater commitment to community-oriented policing. However, Stephen Roach was found not guilty of all charges, just like the other officers involved in deaths of young African American men during this tumultuous period. The problems that violently surfaced in Cincinnati had been smoldering like subterranean magma for years; and neither the explosion of 2001 nor the Collaborative Agreement completely resolved the underlying issues.

Like many American cities, Cincinnati’s race relations are a dormant volcano awaiting the next eruption. Manning Marable, Professor of African American Studies at Columbia University, says as much at the end of Cincinnati Goddamn: “America has the capacity to not just marginalize the poor and black and brown people, but literally to exterminate the lessons of our own history. That’s why Cincinnati is so important. I see it as a harbinger of the future. There will be more Cincinnatis over the next decade. I promise you.” Marable died in 2011, so he didn’t live to see this prophecy come true in the wave of killings that sparked the Black Lives Matter resistance movement.

Dylan fans should watch Cincinnati Goddamn all the way through the closing credits. The final words of the documentary come in the form of a song by Jake Speed & The Freddies called “Hard Times in Cincinnati.” It’s a clever rewrite of Dylan’s “Hard Times in New York Town,” which was itself a rewrite of the folk song “Penny’s Farm.”

Speed comments on Cincinnati’s fraught racial history, including the unrest of 2001, in a fashion worthy of Dylan’s best socially engaged songs. I’ve devoted so much space to establishing this troubled Cincinnati context, not because I think Dylan had a crystal ball and foresaw what was coming—obviously he did not. I foreground it because, in retrospect, we know there’s a slow train coming up around the bend. If you listen closely you can sense it gaining speed and billowing dark smoke. I sometimes compare bootlegs to time machines, capable of transporting us back to a distant place and time. Be that as it may, we take our foreknowledge of what comes next with us, and sometimes that alters what we hear. Personally, I cannot listen to Dylan’s 2000 performance in Cincinnati without seeing foreshadows and hearing harbingers of things to come.

The Concert

When: July 11, 2000

Where: Riverbend Music Center

Headliner: Phil Lesh and Friends

Band: Bob Dylan (vocals, guitar, and harmonica); Larry Campbell (guitar, mandolin, and vocals); Tony Garnier (bass); David Kemper (drums); Charlie Sexton (guitar and vocals)

Setlist:

1. “Duncan and Brady”

2. “Song to Woody”

3. “Desolation Row”

4. “Love Minus Zero / No Limit”

5. “Tangled Up in Blue”

6. “Searching for a Soldier’s Grave”

*

7. “Country Pie”

8. “Tell Me that It Isn’t True”

9. “Just Like Tom Thumb’s Blues”

10. “Positively 4th Street”

11. “The Wicked Messenger”

12. “Leopard-Skin Pill-Box Hat”

*

13. “Things Have Changed”

14. “Like a Rolling Stone”

15. “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall”

16. “Highway 61 Revisited”

Acoustic Set

Dylan opens with “Duncan and Brady”—a murder ballad about a police shooting. In this case, a white officer is shot and killed by a Black man. The song is based loosely on real events. Patrick Blackman has an informative piece on “Duncan and Brady” for the magazine Sing Out! It turns out that three familiar murder ballads that were part of Dylan’s folk repertoire were inspired by true crimes committed in St. Louis in the 1890s: “Duncan and Brady,” “Stack a Lee,” and “Frankie and Johnny” (aka “Frankie and Albert”). Drawing heavily upon John Russell David’s doctoral thesis “Tragedy in Ragtime: Black Folktales from St. Louis” (St. Louis University, 1976), Blackman details the death of Patrolman James Brady on October 6, 1890, in Charles Starkes’s saloon in the predominantly Black neighborhood of Deep Morgan, nicknamed “The Bloody Third” police district. That night there was a physical altercation between two white policemen, Brady and Gaffney, and two Black brothers, Harry and Luther Duncan. The brothers fled into the saloon where Brady was shot and killed. Harry Duncan was also shot multiple times but survived. He was tried and convicted of Brady’s murder, though he insisted that Starkes was the man who actually killed Brady. Duncan’s appeals were all denied, however, and on July 27, 1894, William Henry Harrison Duncan was executed by hanging.

I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again: When and where a performance takes place matters. I doubt that Dylan was specifically aware of the simmering animosity between Cincinnati’s Black community and the police. However, the author of “Hurricane” was fully aware of, and outraged by, this pervasive problem plaguing American cities. As listeners, when we return to the 2000 bootleg now, it’s hard to listen to “Duncan and Brady” without superimposing images of Thomas and Roach, an officer-involved shooting that unleashed calamity in Cincinnati and forced an overdue reckoning with the city’s racially charged divisions. This gestating tragedy was still nine months away when Dylan played Riverbend. But when the rough beast, its hour come round at last, slouched toward Cincinnati to be born, it changed utterly my perspective on “Duncan and Brady.” At the time, no one at Riverbend could have heard the beating wings of the angel of history, but I can’t unhear it now.

None of the lyrics Dylan sings refer directly to Duncan. Each verse focuses instead on Brady and the community’s reaction to his death. “Duncan and Brady” is in effect a protest song against police brutality. Officer Brady was a dirty cop who abused his power:

Twinkle, twinkle, little star

Along came Brady in his ’lectric car

Got a mean look runnin’ in his eye

He’s gonna shoot somebody just to see him die

Brady is looking for trouble, knowing that his badge (his twinkling little star) will grant him total immunity. “King Brady” is a despotic bully who has lorded it over the neighborhood for years. Now the king is dead.

The song’s sympathies lie with the regicide Duncan, not with the slain King Brady. This is clear from the second verse, which describes the shooting as the officer’s own fault:

Brady, Brady, now you know you done wrong

Breakin’ in here while this game’s going on

Bustin’ on the window, beatin’ on the door

Now you’re lyin’ dead on the barroom floor

How does the community respond to the killing of Brady? The third verse tells us:

When the women all heard King Brady was dead

They went on home and they came back in red

Slippin’ and slidin’, shovin’ on the street

With their big Mother Hubbards and their stocking feet

In other words, they do not dress in black to mourn his loss. When they hear the news of the tyrant’s death, they dress in red and dance in the streets.

The singer knows better than to blatantly rejoice in the killing of a policeman. But his verdict is unmistakable from the refrain: “He’s been on the job too long.” This officer didn’t serve and protect the community, he terrorized it. Not anymore. Take that badge off Brady, he can’t use it anymore. He has walked his last beat, and the neighborhood breathes a collective sigh of relief at his “retirement.” The bad blood between the St. Louis police and Deep Morgan residents uncannily anticipates the antipathy between the Cincinnati police and the residents of Over-the-Rhine and other predominantly Black neighborhoods. Dylan is no soothsayer, but he couldn’t have picked a more prescient opening song.

Plus, it’s a damn fine performance. During this era of the NET, Dylan generally opened concerts with traditional songs. Remember that he kicked off Bogart’s ’99 with “Somebody Touched Me.” As with that arrangement, Larry Campbell and Charlie Sexton join in with spirited vocal accompaniment on “Duncan and Brady.” I’ve focused on serious subjects so far, but the ballad is also darkly satirical. Dylan winks at the audience with self-deprecating humor as he and the lads sing, “He’s been on the job too long.” I’m sure there were plenty of beer-swishers at Riverbend who elbowed each other and had a laugh at how well the line applied to the old goat bleating from the stage. You’ve got to admit it’s pretty funny to begin a concert with the complaint “He’s been on the job too long.” Sorry, no, he’s just getting started.

Dylan’s next song is indeed from when he was just getting started: “Song to Woody.” As a young folk singer, he modeled himself faithfully after Woody Guthrie. In Chronicles, he vividly recounts how Guthrie’s songs changed his life: “They had the infinite sweep of humanity in them. Not one mediocre song in the bunch. Woody Guthrie tore everything in his path to pieces. For me it was an epiphany, like some heavy anchor had just plunged into the waters of the harbor” (244). Guthrie pointed the way toward Dylan’s destiny, and he heard his vocational calling in Woody’s Okie drawl. “I decided then and there to sing nothing but Guthrie songs. […] Through his compositions my view of the world was coming sharply into focus. I said to myself I was going to be Guthrie’s greatest disciple. It seemed like a worthy thing to do” (Chronicles 245, 246).

Dylan went to New York to seek his fortune and to thank his mentor in person. He expressed his humble gratitude in “Song to Woody,” the first song he wrote after his arrival in NYC in 1961. “Song to Woody” is both a tribute and a farewell. “I’m out here a thousand miles from my home / Walkin’ a road other men have gone down.” Dylan was only 20 when he wrote the song, but already he’s a worried man with a worried mind. He follows in the footsteps of Woody and other likeminded musicians, mentioning Cisco Houston, Sonny Terry, and Lead Belly by name. It’s an honorable lineage and a worthy cause, but it’s also a long, hard road:

I’m a-leavin’ tomorrow, but I could leave today

Somewhere down the road someday

The very last thing that I’d want to do

Is to say I’ve been hittin’ some hard travelin’ too

The young troubadour was only beginning his journey and imagining future fatigue when he recorded the song for his debut album in 1962. By the time the 59-year-old bard revived the song at Riverbend ’00—four decades further down the road and a dozen years into the relentless Never Ending Tour, having already outlived Guthrie (who died at 55)—Dylan knew the weariness of the road like few before him or since. Sonically, Dylan sounds in good form tonight, but his song selection implies exhaustion: “He’s been on the job too long”; “I’ve been hittin’ some hard travelin’ too”; “Seems sick an’ it’s hungry, it’s tired an’ it’s torn / It looks like it’s a-dyin’ an’ it’s hardly been born.” Pay attention to Dylan’s music and vocals, and he seems alert and engaged. Pay attention to his words, and you might wonder if the hardships of this wandering life were taking their toll.

To be fair, along with the world-weariness of “Song to Woody,” Dylan also communicates a lot of love and admiration. In that respect, the contrast between the first two songs couldn’t be sharper. “Duncan and Brady” revels in the death of a despicable man who exploited the people he was duty-bound to serve. “Song to Woody” celebrates the life of a noble man who led his life with dignity, motivated by concern for others. Dylan inherits Guthrie’s legacy, builds upon it, and pays it forward night after night, year after year, in no small part because it’s what Woody would have wanted him to do. Recalling his sense of spiritual kinship to Guthrie before he even met him, Dylan writes movingly in Chronicles: “One by one, I began singing them all, felt connected to these songs on every level. They were cosmic. One thing for sure, Woody Guthrie had never seen nor heard of me, but it felt like he was saying, ‘I’ll be going away, but I’m leaving this job in your hands. I know I can count on you’” (246). He’s been on the job a long time, that’s for sure, but it’s a job worth doing and a job well done.

In his chapter for The Politics and Power of Bob Dylan’s Live Performances: Play a Song for Me, Court Carney points out that, when Dylan resurrected “Song to Woody” in the late 1990s and early 2000s, he installed it reliably in the second slot of the setlist, following a traditional song and teeing up one of his own major compositions. Sure enough, Riverbend ’00 fits this paradigm: 1) “Duncan and Brady,” 2) “Song to Woody,” 3) “Desolation Row.” Dylan’s passage above from Chronicles suggests a torch being passed, and Court traces that same dynamic at work in the three-song structure, progressing from the folk tradition, through Woody, to Dylan. “This juxtaposition between old and familiar underscores the powerful vectors encoded in ‘Song to Woody,’” Court observes. “In these shows, Dylan tends to be saying: here is the past, here is my past, here is an opening, here is the entry point, here is a way into understanding the past, here is a slanted and personal and signifying look at history, here is a tethering of the ambiguities and tensions of the past and the present” (8).

The band’s performance of “Desolation Row” at Riverbend ’00 is fantastic. Cincinnati has been fortunate to receive at least three Dylan renditions of this classic (1992, 1999, and 2000; he may well have played it in November 1965, too, but we don’t know the setlist for sure). Funny thing is, each time he’s only sung 5 of the 10 verses, and each time it’s been a different combination. This time he sings verses 1, 2, 3, 7, and 10. I think this is the best of the bunch. Dylan starts off singing quietly, just his vocals and guitar plus a thrumming beat from Garnier’s bass. The band comes in by the end of the first verse, and midway through the song turns into a bona fide guitar jam. Drummer David Kemper keeps a brisker pace than I’m accustomed to for “Desolation Row,” but I love the results. The whole ensemble sounds so together, so tight. Charlie Sexton was still in his rookie season when the band played Bogart’s ’99, but, according to Olof Björner’s statistics, this was concert #133 for this particular NET lineup. The band sounds like a cohesive unit, and “Desolation Row” showcases their strong team chemistry.

It’s possible Dylan sang “Love Minus Zero / No Limit” at one or both of his 1965 shows, but no record survives. When he plays it at Riverbend ’00, it becomes the only Cincinnati performance of this gorgeous love song ever captured on tape. He reconceives it as a sad country ballad, aided by Campbell’s steel guitar, playing a melody that sounds to my untrained ear like the kissing cousin of “If Not for You.” There are some lovely guitar touches at the end, too, probably by the frontman himself. The crowd responds warmly at the conclusion, acknowledged with a hearty “Thank you!” from Dylan.

When I first listened to this bootleg, I was underwhelmed by “Love Minus Zero.” In my initial notes I wrote, “I’m not used to this song being such a downer. It’s more morose than it needs to be.” Having now listened to it several times, I want to grab my former self by the lapels and shout “Wake up! This is amazing!” Now I’m totally vibing with the brooding beauty of Dylan’s performance, a vocal delivery that would feel perfectly at home in the Rough and Rowdy Ways Tour. Listen to his expert phrasing, particularly at the end of each verse. I hadn’t realized how many “-er” words Dylan uses for rhymes until he drew my attention to it through this performance: “ho-urs,” “flow-ers,” “buy her,” “fut-ure,” “fail-ure,” “anoth-er,” “both-er,” “hamm-er.” I now notice that most lines in this song have feminine endings (lines that end on an unstressed syllable), which may communicate something subliminally, though I’m not sure what. The music is top-notch, too. Dylan probably won’t ever play this song live again, but he sure nailed this one documented Cincinnati performance.

The audience reacts excitedly to the familiar opening strain of “Tangled Up in Blue.” You can hear them get increasingly pumped up over the course of the song, and by the end they release their biggest cheers of the night so far. The chief credit here goes to the musicians. The band is smoking hot, the guitarists are running fast and free, and the drummer is pounding back there like a buffalo stampede. And the vocalist? Well, his delivery is . . . interesting.

I like it a little better each time I listen, but I don’t think the listener’s enjoyment is foremost in Dylan’s mind. He sometimes sounds willfully out of step with the tempo the band is playing. It’s one of those performances—if you listen to a lot of bootlegs you’ll frequently encounter this—where Dylan seems more intent upon trying out different pitches, speeds, and vocal effects, or laying the stress in unexpected places, or stretching out some words while racing through others—in short, more interested in experimentation than on coherence. I don’t fault him: these rough sketches occasionally turn from doodles into masterpieces, even at the risk of collapsing into tangled messes. Hand the lyrics to any other vocalist on the planet and none of them would sing “Tangled Up in Blue” like this. But that’s also what we love, right? This Riverbend ’00 performance epitomizes the quirky, unpredictable, inimitable essence of Bobness.

Now we come to my favorite performance of the concert, and one of my favorites in all of Dylan in Cincinnati. The band closes the acoustic set with “Searching for a Soldier’s Grave.” Let’s dig deep into this one because I find it so effective on many levels. Dylan was drawn intensely to this song between 2000 and 2002, playing it 111 times during that span and then never again. The Riverbend ’00 rendition was only his ninth live performance ever. The song was written in 1946 by Johnnie Wright, Jim Anglin, and Jack Anglin, and popularized by Roy Acuff, The Bailes Brothers, and The Stanley Brothers. Around this time, Dylan got involved in the Hank Williams tribute album Timeless, released the following year, so he was probably plunging back into the country legend’s songbook. Hank Williams and The Drifting Cowboys recorded a moving rendition of this song 1951:

In “Searching for a Soldier’s Grave,” the singer crosses the Atlantic seeking the grave of an American soldier killed in World War II. For what it’s worth, Dylan premiered the song at his first concert back in the States after a spring tour of Europe. Perhaps the trip through Germany and Italy brought this old song back to mind, though I suspect he had other triggers, too. “Searching for a Soldier’s Grave” is basically “Two Soldiers” meets “Lone Pilgrim,” songs Dylan covered on World Gone Wrong. He began the acoustic set with a song that mocked the death of a man in uniform, but the emotional register is completely different in this last song of the set, a sincere tribute to a fallen soldier stranded thousands of miles from his home.

I am completely enraptured by Dylan, Campbell, and Sexton’s shared vocals in this performance. The lovely mandolin brings out the song’s Appalachian roots. As someone from the hills of Tennessee myself, I feel like I’m back at Herren’s Chapel Church of Christ on a Sunday morning listening to Lloyd Shores or Ronnie Herren lead the congregation in a hymn. Dylan was deeply influenced by the harmonies of old country, bluegrass, and gospel groups, and this performance features a perfect synthesis of those traditions.

I’ll admit that it’s a bit strange to hear Dylan sing such a patriotic song. We tend to associate him with songs critical of war, the military industrial complex, and the indoctrination of soldiers into nationalistic violence [e.g., “John Brown,” “Masters of War,” “With God on Our Side,” and “Clean Cut Kid”]. “Searching for a Soldier’s Grave,” on the other hand, extols the sacrifice of “all the Americans who all died true and brave.” The song’s gut-punch is emotional, however, not political. It’s a dirge of mourning, focusing on the devastated loved ones left behind to mourn the loss of this nameless soldier. The song opens:

You ask me, stranger, why I made this journey

Why I cross three thousand miles of rolling waves

Like so many others my love was killed in action

So I’m here, I’m searching for his grave

The most poignant portion of the song is the third verse:

Beside each cross mark there all around me

I’ll kneel down and gladly say a prayer

For all the dear loved ones home across the ocean

Whose hearts like mine are buried over here

The song takes a conflict whose scale of death is too enormous to be fathomed, and it personalizes the human costs by focusing on a single mourner’s grief over the death of an individual combatant. There’s a similar story behind every one of those cross marks, and this song serves as a humble commemoration of just one representative loss.

I have some theories about what might have inspired Dylan to begin playing this song so regularly in 2000. As I mentioned earlier, he introduced it in the summer, after a spring tour of Europe. On May 24, 2000, he played a concert in Dresden, a city utterly decimated in World War II by Allied fire bombings. At the end of the show, he told the crowd, “I will remember this birthday for a while.” I wonder if that show brought back memories of the last time Dylan had played a concert on his birthday, way back in 1966, when he turned 25 and performed in Paris. He was flanked that night by Rick Danko, bassist and brother in arms. Danko died of heart failure on December 10, 1999.

Dylan compared the bandmates who played with him during that tumultuous 1966 tour to knights. In No Direction Home he reflects, “The guys who were with me on that tour, which later became The Band, we were all in it together. We were putting our heads in the lion’s mouth. I had to admire them for sticking it out with me. Just for doing it, in my book they were gallant knights for even standing behind me.” Knights = Soldiers? If Dylan went searching for this fallen soldier’s grave, he wouldn’t need to cross the Atlantic. Danko is buried next to his son Eli in Dylan’s old stomping grounds of Woodstock, New York. His epitaph contains a Dylan allusion: “Forever Young, Forever Loved.”

But I think Dylan has another grave in mind even closer to home. While listening to the Riverbend ’00 performance of “Searching for a Soldier’s Grave” for the third or fourth time in a row, it suddenly hit me like a sledgehammer: Dylan is mourning his mother through this song. In “Lonesome Day Blues,” the same 2001 song where Dylan sings, “I wish my mother was still alive,” he also includes this line: “Well, my pa he died and left me, my brother got killed in the war.” During the 2000-2001 period, Dylan was pondering casualties of war in highly personal terms from the perspective of the survivors left behind. Years later in The Philosophy of Modern Song (2022), he counsels, “Knowing a singer’s life story doesn’t particularly help your understanding of a song. […] It’s what a song makes you feel about your own life that’s important” (9). Dare I ask what “Searching for a Soldier’s Grave” makes Dylan feel?

I normally avoid autobiographical readings on principle, so I’m aware of the hypocrisy in breaking my own rules. But hear me out. I can’t shake the feeling that his mother’s death is the key to unlocking “Searching for a Soldier’s Grave.” Dylan debuted the song on June 15, 2000, just two days after what would have been Beatty’s 85th birthday, and his first concert back from Europe. Her family had traveled the Atlantic in the opposite direction, leaving Lithuania for a new home in America. Now she lies buried beside Abe Zimmerman in a Minnesota grave. Dylan songs aren’t diary entries, and he would never want to make a public spectacle of his private grief. If my hunch is right, this song allows him to tell the truth but tell it slant. He chooses a dirge that taps into his mood of mourning while providing cover and deflection from its personal source. He’s here [on this occasion in Cincinnati] searching for [her] grave.

What I’m proposing here is that, in his performance of “Searching for a Soldier’s Grave,” Dylan works through the death of his mother in the same sort of way Shakespeare works through the death of his son in Hamlet. I’m comparing their artistic methods, mind you, not the relative magnitude of their achievements. In her brilliant, heart-wrenching novel Hamnet: A Novel of the Plague, Maggie O’Farrell suggests that Shakespeare wrote Hamlet as a way of processing his grief for his son Hamnet, who died at 11. In an imaginative leap of paternal fantasy, Shakespeare reverses the roles, making the father the one who dies and the son the one who lives to mourn him. In the thrilling conclusion of the novel, Agnes (aka Anne Hathaway), Shakespeare’s wife and Hamnet’s mother, attends the premiere of Hamlet. From the audience, she intuits the creative act of substitution unfolding through the performance, as Prince Hamlet encounters the ghost of his dead father, played by Shakespeare himself:

Hamlet, here, on this stage, is two people, the young man, alive, and the father, dead. He is both alive and dead. Her husband has brought him back to life, in the only way he can. As the ghost talks, she sees that her husband, in writing this, in taking the role of the ghost, has changed places with his son. He has taken his son’s death and made it his own; he has put himself in death’s clutches, resurrecting the boy in his place. (O’Farrell 304)

I sense that Dylan is doing something comparable in “Searching for a Soldier’s Grave,” albeit in reverse. He picks a song that allows him to trade places with the dead, singing about a son who dies far from home. But he also chooses a song that allows him empathetically to inhabit the role of the surviving parent, providing an outlet for mourning, deeply but indirectly, through art.

As long as we’re considering the psychodynamics of projecting our own experiences into songs, maybe I’m mourning for my own mother through this elaborate interpretation of “Searching for a Soldier’s Grave.” If I’m going to speculate about Dylan’s personal connection to this song, I should be transparent about my own.

Bonnie Lee Elrod was born in 1945, the year before this song was written. Like Dylan’s mother, my mother’s maternal ancestors are from Lithuania. The Elrods were a military family. Both of her parents were enlisted in the U.S. Army during World War II, and my mother was born at Fort Jackson in South Carolina in the final year of the war. Her father Dick (Robert Graley Elrod, Sr.) later served in Korea, her brother Bobby (Robert Graley Elrod, Jr.) fought in Vietnam, and her mother (Ann Sinkavich Elrod) died at the Presidio base in San Francisco and is buried in Golden Gate National Cemetery. My mother died January 5, 2021, and is buried in the G.V. Herren Family Cemetery in Tennessee beside my father Charles. The images and themes in the song—war, distant graves, transatlantic crossing, loss, grief—resonate with my family history as much as I suspect they do for Dylan. By hearing “Searching for a Soldier’s Grave” as a work of mourning, it’s possible that what I’m really doing is responding to my own mother’s death through the prism of song. Ultimately, I can’t say for sure what this song means to Dylan, but now you know what it means to me. “It’s what a song makes you feel about your own life that’s important” (Philosophy of Modern Song 9).

Electric Set

Mothers mourning sons, sons mourning mothers—this has gotten awfully grim for a rock concert, no? Dylan plugs in and lightens up with a welcome palate cleanser to open the electric set, a heaping helping of “Country Pie.”

This sugary slice from Nashville Skyline is as shallow as the previous song is deep, but at this point in the concert it’s just what we need. “Oh me, oh my / Love that country pie!” Despite its appearance on Dylan’s most country album, the Riverbend ’00 rendition is a full-force rocker. No one was handing out Nobel Prizes, or even Polar Music Prizes, for the likes of “Country Pie.” But Dylan has learned a thing or two about setlist construction by 2000, and he makes the right call to open the electric set with a toe-tapper that gets the blood pumping again.

Did someone hand Dylan the wrong itinerary on the tour bus? Does he think he’s in Nashville? He follows up one deep cut from Nashville Skyline with an even deeper cut from the same album: “Tell Me that It Isn’t True.” He had never played either of these 1969 songs live until 2000. In the case of “Tell Me that It Isn’t True,” the Riverbend ’00 performance was only his twelfth ever. Who could have guessed that, halfway through the concert, Dylan would have played more songs from Nashville Skyline than any other album? And none from Time Out of Mind, the Grammy winner for Album of the Year just three years prior?

The lyrics seem pretty cliché: I hear you’re hanging out with another man, please say it’s not true. However, now that I’ve got death on my mind, it keeps bleeding into my ears. I wonder if there’s something darker going on in this song. Dylan wrote it the year after his father’s death, and he revives it the year of his mother’s death. What if “Tell Me that It Isn’t True” isn’t a bubblegum breakup ballad but a demon lover song, a descendant of “House Carpenter” and a forerunner of “Man in the Long Black Coat” and “Black Rider”?

They say that you been seen with some other man

That he’s tall, dark and handsome, and is holdin’ your hand

Darlin’ I’m countin’ on you

You gotta tell me, tell me that it isn’t true

Imagine that the “tall, dark, and handsome” figure that is holding her hand isn’t a rival lover but is instead the Grim Reaper. If this is just some lame-ass generic love song, someone forgot to inform the impassioned crooner. He finds an emotional purchase and gives it his all:

To know someone else is holding you tight

It just hurts me all over to hear it, you know it just doesn’t sound riii-iight!

All of these awful things that I have heard

I don’t want to believe them, all I want is your word

Darlin’ I’m countin’ on you

You got to tell me, tell me that it isn’t true!

The heartbroken singer simply cannot accept this loss. Given the timing and the juxtaposition with other songs in the setlist, I wonder if the emotional reservoir Dylan draws from is less jilted love and more the melancholia of unresolved mourning.

After two relatively obscure selections, Dylan returns to prime time with “Just Like Tom Thumb’s Blues,” a standout from one of his greatest albums, Highway 61 Revisited. This is his only documented performance of the song in Cincinnati (insert standard asterisk here about 1965). Riverbend ’00 is a very cool rendition. There’s a guitar riff running throughout that sounds sort of like the loop in “Highlands” from Time Out of Mind. I dig this laid-back version of the song: very different than the famous album version, but equally intoxicating.

I always love the conclusion, but it accrues an extra layer of meaning in the context of this setlist. After biting off more than he could chew on a decadent bender down south, the burned-out singer declares, “I’m going back to New York City / I believe I’ve had enough.” After playing two straight songs recorded down south in Nashville (“Country Pie” and “Tell Me that It Isn’t True”), Dylan follows with a song set in the south but recorded in New York (“Just Like Tom Thumb’s Blues”). At the end of that song, he declares he’s heading back to New York, and, sure enough, the next song is “Positively 4th Street,” recorded in New York and set among the coffeehouses and bars of Greenwich Village. Oh, you’re a sly one, Bob!

You’ll recall that “Positively 4th Street” was Dylan’s rejoinder to the folk purists who turned against him when he went electric at the Newport Folk Festival in 1965. It was recorded while Dylan was working on Highway 61 Revisited, but apparently he was so eager to shoot it across the bow that he released it in advance as a single.

All of that righteous anger and urgency is drained out of the Riverbend ’00 version. The pace is slow, and Dylan’s vocal is subdued. Some songs are open to being played with bitterness or being played with tenderness. I just don’t think this is one of them. Anger is too central to this song to be optional or detachable; remove the anger and “Positively 4th Street” loses its reason for existing. Dylan’s approach here is wistful, I guess, or maybe he’s going for wounded. Whatever it was he was aiming for, it misses the mark for me and just comes across as bloodless. Skip. Unsubscribe.

In the interests of a balanced treatment, I should point out that others listened to the same performance and found it sublime. I came across a very interesting concert review on Bob Links by Mark Rothfuss. He was a college student from the Cincinnati area who followed Dylan around on the summer tour of 2000. He was underwhelmed by the concert two nights earlier in Noblesville, Indiana. But he raved about the Riverbend show. “I’ve been seeing shows there for as long as I can remember and this one topped them all.” He cited several highlights, but he praised Dylan’s performance of “Positively 4th Street” above all others:

Retraction time. Just 48 hours ago I made the assertion that Bob should shelve this song. Well, I was wrong. Tonight’s rendering was simply perfect. Laid back? Yes. Uninteresting? No! This is the best he sang all night. It was hypnotic. It was captivating. He teased and manipulated the message and the words like only he can. Whispers, growls, pointed annunciation (plus some well-paced guitar) made this a sublime listening experience. When you get the tape, just close your eyes and enjoy.

This glowing reaction from Rothfuss motivated me to go back and give the song another chance. I closed my eyes and opened my mind . . . but I still don’t hear it. Listen for yourself and you be the judge. The irony isn’t lost on me: I’m hating on a song which is essentially Dylan’s rebuttal to all the haters who turned against him when they didn’t like his new musical choices. I’m certainly receptive to Dylan’s musical experiments, and some of the Riverbend ’00 performances that I resisted initially have subsequently grown on me. Unfortunately, I remain negative about “Positively 4th Street.” But hey, why dwell on the bad. “If ye cannot bring good news, then don’t bring any.”

Good news! Dylan and mates get their groove back on the next song, an amazing electric performance of “The Wicked Messenger.” This was only Dylan’s eighth live performance ever of the song. I’m so familiar with the pared-down version on John Wesley Harding that I was skeptical at first of this rock arrangement. But it didn’t take long for me to come around, and now I absolutely love it.

I should’ve known better than to resist. The ominous acoustic songs of John Wesley Harding have an impressive track record of amplified reimagination by rockers. The most famous example is “All Along the Watchtower,” launched into the heavens by that brilliant shooting star Jimi Hendrix. But I also should have known better because I’d already heard a great rock version of “The Wicked Messenger” by The Godmother of Punk.

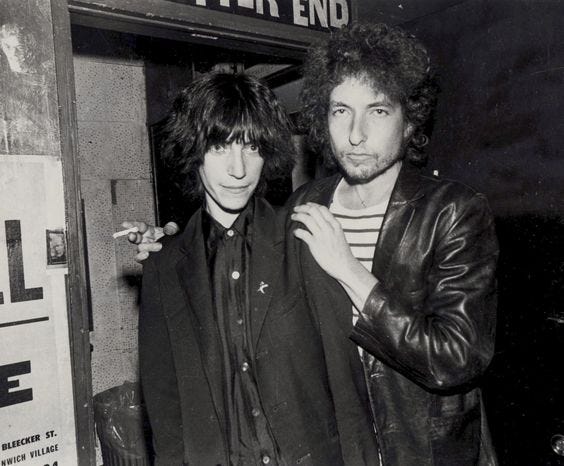

Patti Smith and Bob Dylan have a long and rich history, and it dovetails with the theme of mothers and mourning. She was first introduced to Dylan’s music by her mother. As she told Thurston Moore in an interview for BOMB magazine, “My mother was a counter waitress in a drugstore where they had a bargain bin of used records. One day she brought this record home and said, ‘I never heard of the fellow but he looks like somebody you’d like,’ and it was Another Side of Bob Dylan. I loved him.” She taught herself to play guitar from a Dylan songbook. When Smith was beginning to make a name for herself as a performer, Dylan showed up one night unannounced to her show at the Bitter End. Their first encounter was awkward, but it meant a lot to her, as she remembers in Just Kids:

I could feel another presence as surely as the rabbit senses the hound. He was there. I suddenly understood the nature of the electric air. Bob Dylan had entered the club. This knowledge had a strange effect on me. Instead of humbled, I felt a power, perhaps his; but I also felt my own worth and the worth of my band. It seemed for me a night of initiation, where I had to become fully myself in the presence of the one I had modeled myself after. (248)

The cosmic transfer she describes, from mentor to protégé, is reminiscent of young Dylan’s sense that Woody Guthrie had passed down a torch to him. However, Smith initially feared she had blown it with Dylan. They posed for a photo together, which appeared in The Village Voice, but otherwise failed to connect in that first meeting.

The rift was repaired soon after during a chance encounter on 4th Street, of all places:

And then a few days later I was walking down 4th Street by the Bottom Line and I saw him coming. He put his hand in his jacket—he was still wearing the same clothes he had on in the picture, which I liked—and he takes out The Village Voice picture and says, “Who are these two people? You know who these people are?” Then he smiled at me and I knew it was all right. (Moore)

Smith was courted for Dylan’s Rolling Thunder Revue in 1975 but she declined, preferring to concentrate on her own projects. It was the right move. Her legendary album Horses came out that same year, and it’s hard to imagine the fiery renegade fitting into a supporting role in the RTR medicine show.

Patti Smith wouldn’t have another opportunity to tour with Dylan until many years later. She quit the concert circuit for sixteen years to raise a family with her husband Fred “Sonic” Smith of the band MC5. After his untimely death in 1994, following closely on the heels of her brother’s death and the suicide of her friend Kurt Cobain, Smith was consumed with grief. Music saved her. She channeled her energy into her first album in eight years, Gone Again, which included her kick-ass cover of “The Wicked Messenger.” She credits Dylan with helping to pull her out of the dark hole by inviting her on tour in 1995. In an interview with Alistair McKay, Smith recalls the circumstances:

I was at a very low point in my life. Bob and I spoke privately and I thanked him for giving me the opportunity, and he really encouraged me to come back into the fold. He said the people would be happy to see me. I truthfully wasn’t certain how I would be received, or what I should do, and being encouraged by him was very important to me. I mean, Bob—the man I know—is a man of few words, but the words are always meaningful. And so that was very important. He was very encouraging to me about my place in the community of rock ’n’ roll.

Dylan suggested that they perform a song together on tour, and he gave her free choice of anything she liked. She picked his hauntingly beautiful “Dark Eyes.” Video footage is available online of these lovely duets.

Smith told McKay that a big appeal of the East Coast tour in 1995 was its proximity to her home, allowing her to bring her son Jackson and daughter Jesse along with her, children still mourning the loss of their father.

I’ve given you this extended backstory on Dylan and Smith’s fateful intersections through the years in order to reveal one more: Patti Smith attended the Riverbend ’00 concert! I’m indebted here to Mark Rothfuss, who not only spotted her among the crowd but even had a brief brush with greatness. I’ll let him tell you about it:

It is at this point that Patti fucking Smith walks right by me up the stage-left aisle. She goes completely unrecognized from backstage exit all the way up the walkway where I stop her. I tell her I think she’s great and that she is my favorite female singer. She smiles in appreciation then she and her son continue walking up to the lawn. I am just in shock! Total shock. I thought that was it, but 15 minutes later she and her son return with beverages passing down the big horizontal aisle in the very middle of Riverbend. Nobody seems to notice, which I find odd considering her extremely unmistakable look. When she gets to the point where we are sitting I ask her if she’s gonna play w/ Bob tonight. She said no, that she’s “just here to watch.” So I begged for “Dark Eyes” or a reprise of “Wicked Messenger” and she laughs. Then says “maybe tomorrow.” Turns out she has a show at Bogart’s where Bob played one year ago to today’s date, tomorrow. I just might have to score some tickets. It was short but sweet. She disappeared backstage before anybody even realizes she was there.

Wondrous! Instead of a mother mourning a dead son, or a son mourning a dead mother, we witness The Godmother of Punk, a living mother with her 17-year-old son, not at a cemetery but at a rock concert. Before I lighten your mood too much, though, let me insert a dark footnote. Patti Smith’s father died in 1999, so she and Dylan both had the recent deaths of parents to commiserate over backstage. By the way, Rothfuss is right about the Bogart’s show. A year and a day after Dylan played the same venue, Smith performed at Bogart’s on July 12, 2000. The third song in her setlist was “The Wicked Messenger.”

Encore

It is striking how old most of the song selections are at Riverbend ’00. “Duncan and Brady” is from the 1920s, “Searching for a Soldier’s Grave” is from the 1940s, and nine of Dylan’s first ten songs are from the 1960s. Heading into the encore, the most recent composition he had played was “Tangled Up in Blue,” written in 1974, and three of the four encore selections come the from the sixties. I wonder why Dylan’s emphasis was so firmly fixed on the past? It’s not simply because he chose to “play the hits,” since he bypasses many well-known songs in favor of obscure selections. Don’t get me wrong: I’m not complaining. I appreciate that 8 of his first 12 songs were ones he had never played live in Cincinnati before. Still, it’s odd that he leapfrogs over the last 25 years of the 20th century.

That streak ends with the first number in the encore, Dylan’s newest song, “Things Have Changed.” “I’m a worried man, got a worried mind,” he sings at Riverbend. Note the allusion to Woody Guthrie’s “Worried Man Blues”: “It takes a worried man to sing a worried song.” This is indeed a worried song. Dylan declares in the chorus: “People are crazy and times are strange / I’m locked in tight, I’m out of range / I used to care, but things have changed.” Coming from the author of “The Times They Are A-Changin’,” one of the most beloved anthems of the civil rights movement, that sentiment sounds cynical resignation. Hard to imagine that this is the vocation Guthrie passed on to Dylan.

However, we must remember that Dylan wrote this song specifically for the film Wonder Boys, whose protagonist Grady Tripp (played by Michael Douglas) is a washed-up novelist and jaded wunderkind whose youthful idealism is in tatters. It is entirely possible, therefore, that Dylan is singing in character, expressing Tripp’s cynicism rather than his own. There are certainly several instances where Dylan seems to be adopting a fictional persona (“Standing on the gallows with my head in a noose”), wearing a disguise (“gonna dress in drag”), or experimenting with an alter-ego (“I’m trying to get as far away from myself as I can”). My favorite meta-reference in the song is “I’m in the wrong town, I should be in Hollywood.” Say it ain’t so, Bob! Cincinnati is exactly the right town for you to be in, especially when treating the Riverbend audience to your first performance in our fair city of “Things Have Changed.”

Next up is Dylan’s most dependable crowd-pleaser, “Like a Rolling Stone.” He seems to have made a strategic decision about how to play this one over the years. He starts off conserving his energy vocally, with his fellow musicians holding back accordingly. But as the song proceeds, Dylan and the band gradually build up intensity. Or they’re supposed to. That’s how they played it a year ago at Bogart’s, and that’s what I was expecting here when “Like a Rolling Stone” got off to a slow start. The problem is that, after riding the brake for so long, everyone on stage forgets where to find the gas pedal. This is the lowest energy performance of the song yet in Cincinnati. “Like a Rolling Stone” gathers moss at Riverbend ’00.

While I cannot honestly say I like this performance of “Like a Rolling Stone,” I concede that the somber interpretation is consistent with the dark thread I’ve been tracing throughout this concert. The song may have private maternal connotations for Dylan that contribute to the melancholy mood of “Like a Rolling Stone.” Listen to the chorus he sings at Riverbend ’00 with this salient fact in mind: Beatty Zimmerman’s maiden name was Stone.

How does it feel

How does it feel

To be without a home

With no direction home

Like a complete unknown

Like a rolling stone?

Dylan really leans into that directionless, homeless feeling tonight. The hard travelin’ theme connecting several songs together in this setlist might be tangled up in Dylan’s lonesome blues for his dead mother. The body of Dylan’s first rolling stone—Beatrice Ruth Stone Zimmerman—now resides beneath a headstone in Tifereth Israel Cemetery. To adapt a line from “Standing in the Doorway”: “When the last rays of daylight go down / Beatty, you’ll roll no more.”

Dylan follows up one sixties anthem with another: “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall.” The pace is once again remarkably slow. Campbell and Sexton join Dylan on the refrain, which is very effective, but otherwise my first impression was to find the performance soporific, like Dylan was staggering toward the finish line and struggling to prop his eyelids open. The sun hadn’t even set yet and the opening act was already laid out like a patient etherized upon a table.

I was wrong, so very wrong. The more times I listen, the more touching I find this rendition. Dylan isn’t checked out, he’s locked in, emoting every line like some sad-eyed Noah who shudders for the approaching storm and fatal flood headed inexorably this way. The harmonies from the “tough guy angels” lend a sense of foreboding, as if they are heralds of death here to break open the seals of the apocalypse. My conversion on “Hard Rain,” from infidel to believer, was partially inspired by Mark Rothfuss, who testified to the powerful impact the song made on the Riverbend ’00 audience: “Hard Rain . . . didn’t see it coming. But so glad it came. Very pleasant all around. He spoke the verses more than he sang them. However, everybody including the audience joined in on the chorus to spine-tingling affect. It gives me chills to hear that kind of ‘one-ness’ in a world so mixed-up and at odds.”

What won me over was not just the performance itself, but its integral role within the larger contexts of the concert. When and where a performance takes place matters. Let’s start with Patti Smith’s presence. I had already listened to the bootleg several times before I learned she was in the audience, but Dylan must have known she was going to be there. Were there any plans for her to accompany him on stage for a song? The inclusion of “The Wicked Messenger” makes me wonder. This song wasn’t in Dylan’s regular rotation, but it also wasn’t unprecedented, since he had played it at three previous concerts that summer. Not so with “Hard Rain.” The only time he played this song the entire tour was in Cincinnati. Our erstwhile man in the field, Mark Rothfuss, quotes the celebrity guest saying she was “just here to watch,” but he also reports that she left the audience just before the encore and headed backstage. I get chills fantasizing that Dylan included “Hard Rain” as an open invitation for Patti Smith to join him, if she felt like it, for an impromptu duet. Alas, that never happened. Still, I’m betting that he played the song for her, knowing what special associations she has with “Hard Rain.”

Based upon the old Scottish ballad “Lord Randall,” “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall” is a song about mothers and sons. The mother asks, “Where have you been, my blue-eyed son / Where have you been my darling young one?” In the present context, the most poignant answer from the son is “I’ve been ten thousand miles in the mouth of a graveyard.” Think of Beatty and her blue-eyed Bobby, but think also of Patti and her blue-eyed son Jackson by her side at Riverbend.

Though no one could have foreseen it that evening in 2000, there’s no way to think about “Hard Rain,” Dylan, and Smith now without associating it with Stockholm in 2016. This is the song Patti Smith chose to honor Dylan with at the Nobel Prize ceremony.

She stumbled at one point and needed to start over. But she rallied to deliver a powerhouse performance. In the preface to his book Voices: How a Great Singer Can Change Your Life, Nick Coleman highlights Smith’s “Hard Rain” at Stockholm as a lifechanging vocal performance. “It is impossible to watch without tears,” he observes, but then adds, “It is also as great a passage of singing as you are ever likely to hear, if singing is to you not about the observance of musical correctitude and extravagant display and signaled passion and technical virtuosity, but about the inhabitation of the moment up to and including the moment when the moment bursts” (Coleman xvi).

Patti Smith wrote an essay called “How Does It Feel” for The New Yorker in December 2016, reflecting upon her experience with “Hard Rain” at Stockholm. Her selection of the song was quite intentional. “Having my own blue-eyed son, I sang the words to myself, over and over, in the original key, with pleasure and resolve. I had it in my mind to sing the song exactly as it was written and as well as I was capable of doing.” She also associated the song with her mother and with her late husband. In previous interviews she identified her gateway album as Another Side of Bob Dylan, but here she remembers it as The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan:

I thought of my mother, who bought me my first Dylan album when I was barely sixteen. She found it in the bargain bin at the five-and-dime and bought it with her tip money. “He looked like someone you’d like,” she told me. I played the record over and over, my favorite being “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall.” It occurred to me then that, although I did not live in the time of Arthur Rimbaud, I existed in the time of Bob Dylan. I also thought of my husband and remembered performing the song together, picturing his hands forming the chords.

Mothers and mourning. It’s clear that Patti Smith didn’t just perform the song as a tribute to the Nobel laureate, but that she also sang it as a very memorial hymn for her late mother and husband, and as a love song for her blue-eyed son. Because that’s what we do with songs. “It’s what a song makes you feel about your own life that’s important” (Philosophy 9). What good would music be if it couldn’t help us in our times of greatest need? I’m convinced that, at Riverbend ’00, Dylan was using his selection and performance of songs, his own and those written by others, as an outlet for expressing his feelings about mothers and mourning in much the same way that Smith would later do with “Hard Rain” at Stockholm in 2016. She openly reflects upon this process in her piece for The New Yorker. He is content to let the songs speak for him. “Sing in me, oh Muse, and through me tell the story” (Nobel Lecture).

In the time-honored tradition of all opening acts, the band saves their most raucous number for last. Dylan puts some sting into his vocals, Sexton lights the match with an incendiary guitar solo and whoosh! The band is on fire and goes out in a blaze of glory, slashing and burning the stage before handing it over to Phil Lesh and Friends.

For a concert so steeped in the familial, it’s appropriate that they close with “Highway 61 Revisited.” “God said to Abraham ‘Kill me a son,’” sings the son of Abe Zimmerman. The father acquiesces: “Abe said ‘Where you want this killin’ done?’ / God said ‘Out on Highway Sixty-Ooooooone!’” In other words, God commands the sacrifice of Abe’s son on the highway that runs through Bobby Zimmerman’s hometown.

Given my conviction that Dylan is looking back at the long journey of life through his concert tonight, it’s appropriate that he brings it all back home to Highway 61 on the final song. This highway was his first exit route, leading him to track down Woody Guthrie and follow in his footsteps. It’s also the road that led him (metaphorically if not literally) back for his mother’s funeral in 2000 where she is buried next to his father. Dylan likes full-circle symmetry. There is a story being told through this setlist, an odyssey about leaving and returning. The singer has been hittin’ some hard travelin’; he’s out here a thousand miles from his home; he’s searching for a grave (tell me it isn’t true) and saying a prayer; he used to care but things have changed; he’s out on his own like a rolling stone; but he eventually finds his way back to Highway 61 and follows it all the way home.

Works Cited

Björner, Olof. Still on the Road. https://www.bjorner.com/DSN21820%202000%20US%20Summer%20Tour.htm.

Blackman, Patrick. “‘Duncan and Brady’ / ‘Been on the Job Too Long.’” Sing Out! (14 January 2013), https://singout.org/duncan-and-brady-been-on-the-job-too-long/.

Carney, Court. “Bob Dylan, Woody Guthrie, and the Implications of the Past: A Case Study,” The Politics and Power of Bob Dylan’s Live Performances: Play a Song for Me. Eds. Erin C. Callahan and Court Carney. Routledge, 2023. pp. 1-9.

Cincinnati Goddamn. Directed by April Martin and Paul Hill (The Wexner Center for the Arts, 2015), https://wexarts.org/film-video/cincinnati-goddamn.

Coleman, Nick. Voices: How a Great Singer Can Change Your Life. Counterpoint, 2017.

Dylan, Bob. Chronicles, Volume One. Simon & Schuster, 2004.

---. “Nobel Lecture.” Nobel Prize (4 June 2017). https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/literature/2016/dylan/lecture/.

---. Official Song Lyrics. The Official Bob Dylan Website.

http://www.bobdylan.com/.

---. The Philosophy of Modern Song. Simon & Schuster, 2022.

LB-6963. Bootleg Audio Recording. Taper unknown. Riverbend Music Center, Cincinnati, 11 July 2000.

Fanning, Dave. “Bob Dylan Comes Clean.” The Irish Times Magazine (29 September 2001). Every Mind Polluting Word: Assorted Bob Dylan Utterances, ed. Artur Jarosinski. Don’t Ya Tell Henry, 2006.

McKay, Alistair. “Dark Eyes and a Sardonic Smile: Patti Smith on Working with Bob Dylan,” Alternatives to Valium (3 March 2009), https://alternativestovalium.blogspot.com/2009/03/dark-eyes-and-sardonic-smile-patti_03.html.

Moore, Thurston. Interview with Patti Smith. BOMB (1 January 1996), https://bombmagazine.org/articles/patti-smith/.

No Direction Home. Directed by Martin Scorsese. Paramount Pictures, 2005.

O’Farrell, Maggie. Hamnet: A Novel of the Plague. Knopf, 2020.

Rothfuss, Mark. Concert Review of Riverbend Music Center, Cincinnati (11 July 2000). Bob Links, https://www.boblinks.com/071100r.html.

Shelton, Robert. No Direction Home: The Life and Music of Bob Dylan (Beech Tree Books, 1986.

Smith, Patti. “How Does It Feel.” The New Yorker (14 December 2016), https://www.newyorker.com/culture/cultural-comment/patti-smith-on-singing-at-bob-dylans-nobel-prize-ceremony.

---. Just Kids. Ecco, 2010.

“The story behind the Polar Music Prize.” Polar Music Prize, https://www.polarmusicprize.org/about-the-prize.

Varias, Chris. “Dylan dazzles early crowd.” Cincinnati Enquirer (13 July 2000), E-5.

Maybe its the holidays that influence this comment: when I read your essay this morning, the image that comes to mind is a large, rich, and diverse holiday dinner! Your essay has a theme and but you take off from there for many interesting side stories. One song that was performed at the Polar Music Prize ceremony was one that had not really registered to me until a friend played it at a local musical get together last year...there it was, a great and overlooked song on Oh Mercy! How did I miss it? Here it is at the ceremony:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lKyzzSfC2z8

This is an amazing essay.