Dylan Context

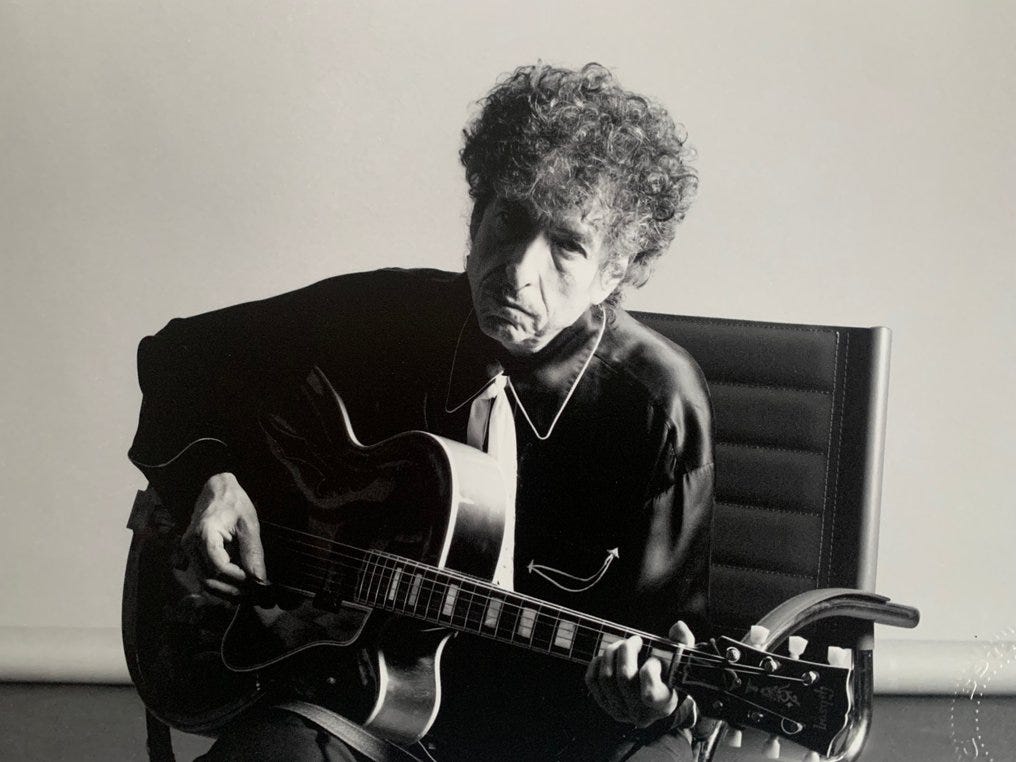

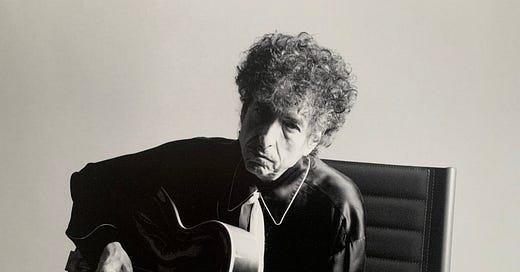

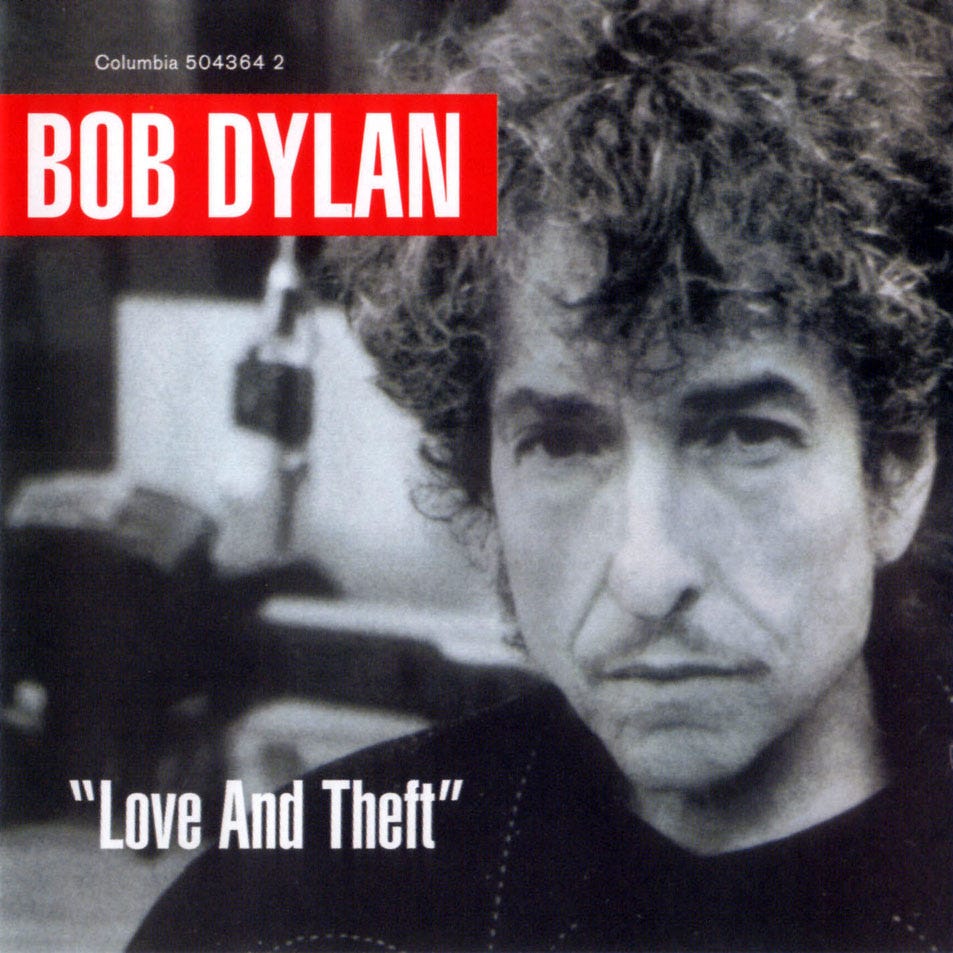

Dylan released his first album of the new millennium in 2001, and it was a major achievement: “Love and Theft.” His reputation as the greatest singer-songwriter of the era rested largely on thirty studio albums from the 20th century, culminating with a Grammy for Album of the Year for Time Out of Mind. And yet this restless troubadour always had a vexed relationship with studio recordings, preferring the spontaneity and immediacy of live performance to the gadgetry of technical manipulation, the monotony of multiple takes, and the calcifying effect of staying put for days or weeks and committing canonical versions of songs to tape.

He was fortunate to team up in the sixties and early seventies with producers he could trust, first Tom Wilson and then Bob Johnston, men with keen ears, steady hands, and laid-back managerial styles which accommodated Dylan’s way of doing things. His luck was less consistent in the eighties, as musical tastes and recording styles changed, and his creative vision, though still sharp at times, occasionally slipped out of focus.

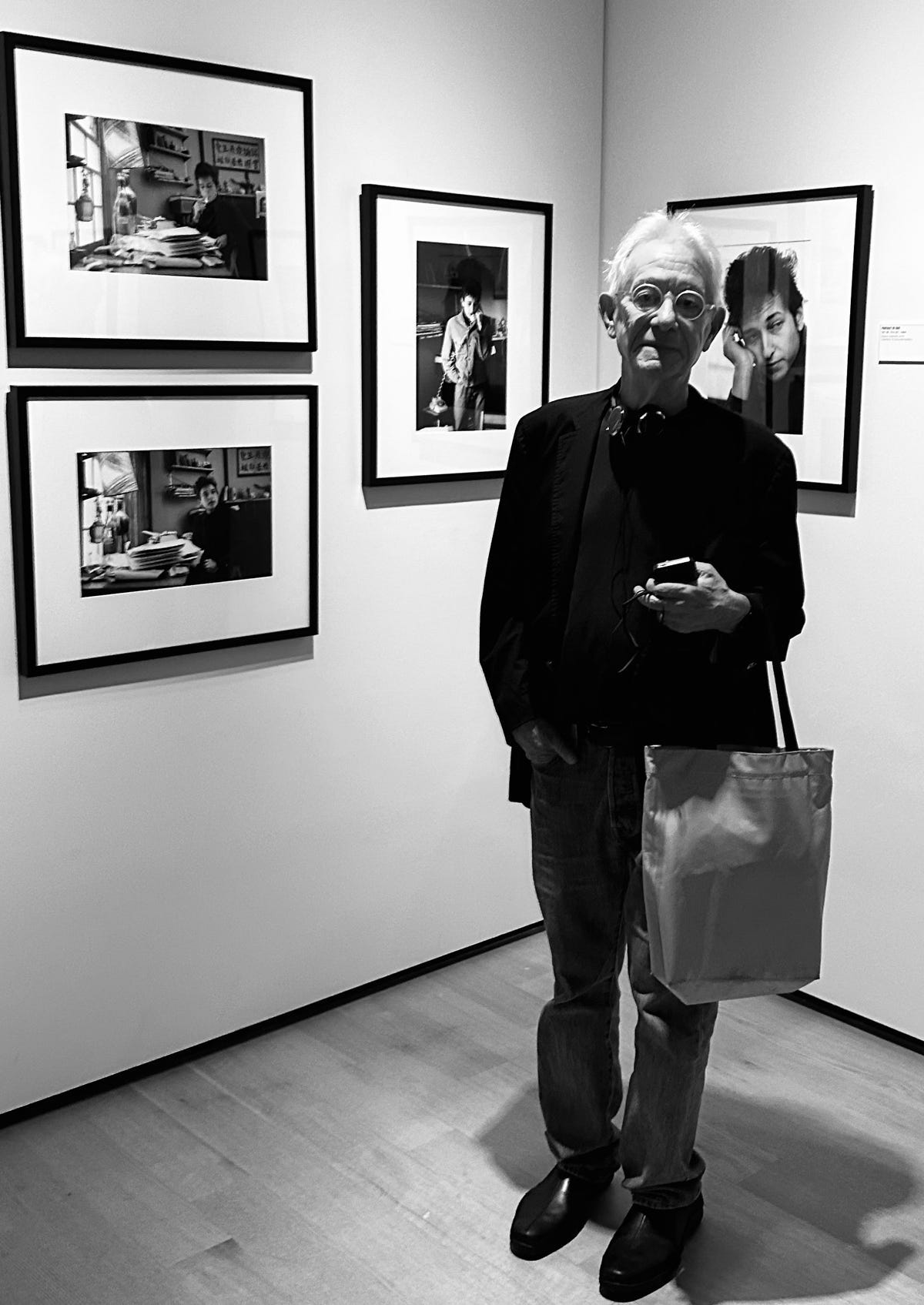

By the nineties, he began taking a more active role in the studio. Under the alias “Jack Frost,” Dylan co-produced under the red sky with Don Was at the beginning of the decade and Time Out of Mind with Daniel Lanois at the end. Although the latter album was one of the most highly acclaimed of his career, his relationship with Lanois was so quarrelsome, and the studio conditions were so chaotic, that he determined never to repeat that frustrating experience. Beginning with “Love and Theft,” Jack Frost became Bob Dylan’s primary producer, and he has remained at the helm throughout the 21st century.

At the risk of oversimplification, Time Out of Mind is a masterpiece of depth, and “Love and Theft” is a masterpiece of breadth. The former shows how much Dylan could accomplish by taking a limited and obsessive set of lyrical images, projecting them onto a dreamer-protagonist wandering through a surreal sonic netherworld, and following that singular mood down to the bottom of a dark well. The results are amazing, and deserve all the album’s accolades. Having pulled it off once, however, he had no interest in repeating himself. His follow-up album is an experiment in range.

After the relentlessly somber tone of TOOM, it is striking how comparatively upbeat his music and mood are on L&T. “Dylan’s voice is almost completely shot here,” concedes Michael Gray in The Bob Dylan Encyclopedia, “yet what he does with it is most subtly nuanced and shrewdly judged. And he is in such a good mood! This is the warmest, most outgoing, most good-humoured Bob Dylan album since Nashville Skyline, if not The Basement Tapes” (432).

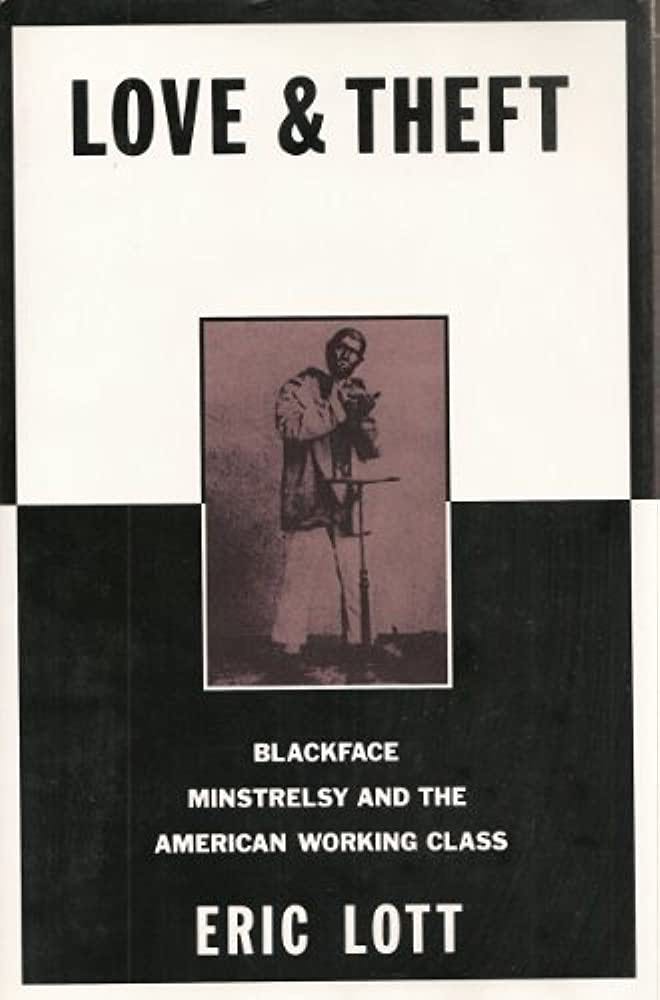

Along with an expanded emotional palette, “Love and Theft” also features a wider variety of musical styles than its predecessor. The album’s title appears in quotation marks and apparently comes from Eric Lott’s academic study Love & Theft: Blackface Minstrelsy and the American Working Class.

Minstrel shows were precursors to vaudeville and featured a wide variety of entertainments: love ballads, dance routines, comic skits, scenes from Shakespeare, and risqué jokes. Dylan’s “Love and Theft” contains all of these elements, too. Of course, blackface minstrelsy also featured vulgar racial mimicry rooted in offensive stereotypes that were as inexcusable then as they are irredeemable now. Why would Dylan conjure up the ghosts of a tradition better left a-moulderin’ in its grave? Love & Theft author Eric Lott has often been asked to speculate about Dylan’s motives.

In his 2017 book Black Mirror: The Cultural Contradictions of American Racism, Lott offers his best guesses in a chapter titled “Just Like Jack Frost’s Blues: Masking and Melancholia in Bob Dylan’s “Love and Theft.’” He conjectures, “I would guess that Dylan regards minstrelsy, say, whatever its ugliness, as responsible for some of the United States’ best music as well as much of its worst” (Lott 201). The cultural historian credits Dylan with daring to “step up and face the racial facts of one of the traditions he inherited” (202). After considering multiple examples of love and theft in songs from the album, rooted particularly in Dylan’s “black mirroring” of the blues, Lott concludes:

Race, memory, and music meet in musical melancholia, where you get by with materials you barely remember taking in the first place: you were too young, or they were too available, or both, and they work so well, speak so solidly to your condition. You reach back to your roots, you work through your masks, and you find yourself again in the land where the blues began. (207)

Dylan’s eroded voice bore witness to the negative consequences of the Never Ending Tour, but the outstanding musicianship on the record testified to the positive effects of constant touring. For whatever reason, his past pattern had been to work with a substantially different lineup of players in the studio than on the road. For his first solo production, however, Jack Frost decided that if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it. Dylan had routinely introduced his bandmates as some of the best players in the country, so he drafted Larry Campbell, Charlie Sexton, Tony Garnier, and David Kemper into service on “Love and Theft.”

In retrospect, Kemper recognized the synergy between the music they had been playing in concert and the sounds they laid down in the studio. In an interview with Alistair McKay, he reflected on his seminar from Professor Dylan:

I didn’t realize we were actually headed somewhere. I wasn’t smart enough to realize: you are in the School of Bob. But when we went in to record “Love and Theft,” I realized then, because the influences were really so old on that record. It comes from really early Americana, way back at the turn of the century, and the 1920s. And not everybody in the band was familiar with that style of playing. And I know that the songs that he would bring in would be these amazing examples of early Americana. Nobody that I know, knows as much about American music as Bob Dylan. He has spent so much time trying to understand, and collecting these songs—it was like a never stopping resource. He was always coming up with these songs or artists that I had never heard of. And then when we went in and recorded “Love and Theft” it was like, oh my God, he’s been teaching us this music—not literally these songs, but these styles. And as a band, we’re familiar with every one of these. That’s why we could cut a song a day for 13 days and the album was done.

Dylan’s apprenticeship was designed to groom the right band to play the right music on “Love and Theft,” and that same group chemistry allowed them to interject these songs immediately into their setlists when they returned to the road in the fall of 2001. This leg of the NET included a stop in Cincinnati. Enquirer music critic Chris Varias singled out the new songs as concert highlights.

Bob Dylan’s perpetual tour over the past several years yields concerts that get a little better each time. The lineup of his backup band hasn’t changed, thus producing musical ESP among the players and heightening the nuances of each performance. Now, as proved by Mr. Dylan’s Sunday night stop at Xavier University’s Cintas Center, the quality has taken a more dramatic leap, thanks to Love and Theft, his terrific new album. It’s not Highway 61 Revisited or Blonde on Blonde or John Wesley Harding terrific—nothing is—but it ranks with his second-tier work, and it provides Mr. Dylan good new material to inject into his shows. As part of his two-hour-plus set he did five Love and Theft tunes, the performances of which ranked with those of any of the several classic songs he played. (C-1)

I don’t have to rely on second-hand testimony because I was there that November night on my home campus of Xavier University. It was an outstanding concert, one of Dylan’s best ever in the city. But I can’t look back without remembering that, like everyone else in attendance, I had a lot of other things on my mind. From the ill-fated day of its release—September 11, 2001—“Love and Theft” became associated with calamity. L&T should have represented an emergence from the darkness of TOOM and back into the light; but the city and the nation were headed in the opposite direction, and the album got absorbed into the turmoil. The shadow of 9/11 enveloped the album and tour that fall, and other local factors contributed to the sense of a pall enshrouding the Cintas Center concert.

Cincinnati Context

Where were you on 9/11? I was in the Cintas Center. I was an Assistant Professor of English beginning my fourth school year at Xavier. The university had a new president, Father Michael Graham, who would go on to serve twenty years in the job.

He holds a doctorate in American Studies from the University of Michigan, is a big Bob Dylan fan, and had previously been a History professor at Xavier before rising through the ranks. Father Graham wanted to send a clear message in his first semester as president that his primary allegiance remained with academics. In his first semester as president, he organized a symposium called Academic Day, bringing together local experts to discuss important issues facing higher education in the 21st century. Classes were canceled that Tuesday so that all Xavier faculty, students, and staff could attend. The events were scheduled for September 11, 2001, at the Cintas Center. This facility had just opened on campus the previous year. It is home for the enormously popular Xavier Musketeers basketball teams. In addition to the sports arena, the Cintas Center contains a conference facility, which is where I was for Academic Day on 9/11.

There was a brief break after Father Graham’s opening remarks and before the first panel was set to begin. On my way to refill my coffee, I saw people huddled around a television in the arena concourse. That’s where I first glimpsed the image of the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center on fire. Like everyone else standing around the Cintas Center, and millions of others watching around the globe, I was in shock and could not comprehend what I was seeing.

Then I watched as the South Tower collapsed and the world instantly changed. I skipped the Academic Day panels and rushed home to be with my wife Cathy and our infant son Dylan—yes, named after Bob—who was nine months old at the time. I didn’t enter the Cintas Center again until the evening of November 4, 2001, to attend the Dylan concert.

Even before 9/11, local citizens were reeling from the so-called Cincinnati Riots in April 2001. As I discussed in the previous chapter, the spark that ignited the civil unrest was the killing of Timothy Thomas by Officer Stephen Roach. However, this was not an isolated incident. Thomas was the fifteenth Black man killed by Cincinnati police since 1995, and the fifth since October 2000. One of those deaths occurred near Xavier’s campus.

Roger Owensby, Jr., died in police custody on November 7, 2000, in the parking lot of Sam’s Carry Out in the neighborhood of Roselawn. For those unfamiliar with Cincinnati, let me connect some geographical dots for you. The precise address where Owensby died was 2092 Seymour Avenue, only a couple blocks from the Cincinnati Gardens (2250 Seymour Avenue), home basketball court of the Xavier Musketeers for many years (1983-2000). Dylan played a concert at Cincinnati Gardens in 1998. In 2000, Xavier moved into the Cintas Center on campus, site of Dylan’s 2001 concert.

Roger Owensby, Jr., was an Army veteran of the first Gulf War and Bosnia. He was pursued because an officer thought he was the same person who had run away from him days earlier. Owensby was arrested, handcuffed, held down on the ground with a policeman on his back, and sprayed in the face with mace while in this prone position. The coroner determined that Owensby died of asphyxiation, either from a chokehold or from the weight bearing down on his chest, circumstances that eerily anticipate the killing of George Floyd. Officer Robert “Blaine” Jorg was charged with involuntary manslaughter, and Officer Patrick Caton was charged with misdemeanor assault. Caton was found not guilty. Jorg’s jury deadlocked, resulting in a mistrial, and prosecutors chose not to retry the case. Both of those verdicts were handed down in the week prior to Dylan’s arrival in Cincinnati.

On the morning of the concert, the Sunday paper featured a front-page story on the recurring local and national patterns of acquittals for officers accused in the deaths of suspects. Five years later, a federal judge ruled that police had violated Owensby’s civil rights, and his family was awarded a $6.5 million settlement from the city of Cincinnati.

When and where a performance takes place matters. Between the shootings and civil unrest in Cincinnati in April, the terrorist attacks on New York and Washington in September, and the retaliatory airstrikes already under way in Afghanistan, the mood was exceedingly bleak outside the Cintas Center arena. As with any concert, attendees were gathered to have a good time and hear some entertaining music. But there was no way to completely shut out the events surrounding this concert. One other factor impacted my reception as an audience member that night. Because I had the reputation as a big Dylan fan, a generous colleague offered me a cushy seat in a corporate suite overlooking the stage. It should have been a great view.

The problem was that I was attending with a number of people who were less interested in Dylan than in the decisive Game 7 of the 2001 World Series, pitting the Arizona Diamondbacks against the New York Yankees. Much of the world was rooting for a New York victory in the wake of the 9/11 attack on the city. The Diamondbacks upset that storybook ending, rallying in the bottom of the ninth inning to win the game and take the championship.

Fair play to my concert mates, the game was a very big deal. I’m a baseball fan, too, and under normal circumstances I would have been glued to Game 7. But when someone switched on a television shortly after the concert began, I couldn’t shut out the distraction nor stomach the disrespect to Dylan. I left my sweet/suite perch and wandered down to find an unobstructed view at the top of an aisle, where I remained for the rest of the concert. Standing-room-only was good enough for Bogart’s in 1999, and it would damn well be good enough for Cintas in 2001.

The Concert

When: November 4, 2001

Where: Cintas Center, Xavier University

Band: Bob Dylan (vocals, guitar, and harmonica); Larry Campbell (guitar, mandolin, and vocals); Tony Garnier (bass); David Kemper (drums); Charlie Sexton (guitar and vocals)

Setlist:

1. “Wait for the Light to Shine”

2. “Mr. Tambourine Man”

3. “It’s Alright, Ma (I’m only Bleeding)”

4. “Searching for a Soldier’s Grave”

5. “Gotta Serve Somebody”

6. “Floater (Too Much to Ask)”

7. “Country Pie”

8. “Sugar Baby”

9. “Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right”

10. “John Brown”

11. “Tangled Up in Blue”

12. “Summer Days”

13. “Mississippi”

14. “Cold Irons Bound”

15. “Rainy Day Women #12 & 35”

*

16. “Things Have Changed”

17. “Like a Rolling Stone”

18. “Forever Young”

19. “Honest with Me”

20. “Blowin’ in the Wind”

*

21. “All Along the Watchtower”

The 2001 concert marked the fourth consecutive year Dylan played in Cincinnati, a winning streak the city never enjoyed before or since. The Cintas Center concert features the most songs in a local show since his 30-song marathon on the first night at Music Hall in 1981. In fact, the 21 songs performed at Cintas ’01 remains Dylan’s longest Cincinnati setlist of the 21st century. The structure of the concert was distinct as well. The band began with an acoustic set (songs 1-4), shifted to an electric set (5-8), then repeated the pattern with another acoustic (9-11) and electric (12-15) set. After briefly leaving the stage, the band returned for a mixed electric and acoustic encore (16-20), and then came out for one more blistering electric number before scampering to the tour bus to catch end of the World Series.

First Acoustic Set

Dylan and the band charge out of the gate with “Wait for the Light to Shine.” This song was written by Fred Rose, first recorded by Roy Acuff, and best known by Hank Williams. At this point in the NET, it had become customary for Dylan to open concerts by covering an old traditional song. His selection here seems deliberately designed to convey a message of hope in the midst of despair:

Wait for the light to shine

Wait for the light to shine

Pull yourself together

Keep looking for the sign

And wait for the light to shine

Every verse offers encouragement for the downtrodden. Dylan believes in the sustaining power of traditional music, and he administers a healing dose with this opener. The band played “Wait for the Light to Shine” 30 times between October 2001 and May 2002 and then never again.

Dylan’s work on the Hank Williams tribute album Timeless probably put “Wait for the Light to Shine” back on his radar. Timeless was released two weeks after “Love and Theft.” Dylan performed the opening track, “I Can’t Get You Off of My Mind,” and Johnny Cash sang the closer, “I Dreamed about Mama Last Night.” Along with being an early musical hero for Dylan, Williams also has important ties to Cincinnati. Before Nashville was firmly installed as the capital of country music, Williams traveled north to record some of his greatest hits in downtown Cincinnati at Herzog Studios. Two of those songs are covered on Timeless: “I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry” by Keb’ Mo’ and “Lovesick Blues” by Ryan Adams.

Larry Campbell’s bluegrass vocals warble like a whippoorwill on “Wait for the Light to Shine.” Dylan’s voice, on the other hand, is rough as a burlap sack. Honestly, that’s how I feel about most of his vocals for “Love and Theft,” too. There is a lot to admire about that album, but Dylan’s most vital instrument—his voice—had deteriorated noticeably since Time Out of Mind. The same gravelly quality persists at the opening of the Cintas ’01 show. That said, it sometimes takes Dylan a couple songs to get his voice warmed up, so let’s not get discouraged prematurely.

The second song is one of Dylan’s greatest, “Mr. Tambourine Man.” I wouldn’t have noticed this in the arena that night, but after listening to the bootleg several times it dawns on me (pun intended) that Dylan is doing something interesting with light and dark imagery in these two opening songs. “Wait for the Light to Shine” repeatedly invokes the light of hope and salvation. The singer and his audience dwell in the dark night, but they have faith that the darkest hour is right before the dawn. Following on its heels, “Mr. Tambourine Man” is set in the new morning, fulfilling the promise of “Wait for the Light to Shine.” The singer has just endured a sleepless night and made it to sunrise.

I know that evenin’s empire has returned into sand

Vanished from my hand

Left me blindly here to stand, but still not sleeping

My weariness amazes me, I’m branded on my feet

I have no one to meet

And the ancient empty street’s too dead for dreaming

Hey! Mr. Tambourine Man, play a song for me

I’m not sleepy and there is no place I’m going to

Hey! Mr. Tambourine Man, play a song for me

In the jingle jangle morning I’ll come followin’ you

The literary term for this kind of song is an aubade: a hymn of praise heralding the dawn. The insomniac singer looks for direction out of the darkness, and he finds what he’s looking for by the light of day in the tambourine player’s music.

It still sounds like Dylan has a frog in his throat, but the frog begins stretching his legs and limbering up over the course of the performance. When he sings down in the lower register, his phrasing is distinct and quirky (i.e., Dylanesque). But it’s a strain every time he reaches for higher notes or louder volume, like the frog can’t quite make the leap to the next lily pad. I do dig his delivery on the final verse, where he stays (mostly) within his range and delivers interesting phrasing. Overall, it’s a rather uneven performance . . . until he stops singing. I love the musical jam after the final verse. Dylan delights the Cintas crowd when he pulls out his harmonica in the outro and plays an inspired solo. By the end, I adore the song all over again. Once we make it through the foggy ruins and past the frightened trees, Mr. Harmonica Man still knows how to guide us away from the twisted reach of crazy sorrow, turning the Cintas Center into a windy beach where we can dance beneath a diamond sky.

Having made it into the light, Dylan plunges us back into darkness in the next song: “Darkness at the break of noon . . . .” There’s no mistaking another classic from Bringing It All Back Home, “It’s Alright, Ma (I’m Only Bleeding).” Dylan hadn’t played this song in Cincinnati in twenty years, and this would be his final performance in the city. The musicians hang back and Dylan’s mike is way up in the mix, foregrounding his vocal delivery.

He adds some deftly sardonic inflections to certain lines. “Goodness hides behind its gates / Even the President of the United States / Sometimes must have to stand . . . naked.” This barbed criticism earns a big cheer from the audience. “It’s Alright, Ma (I’m Only Bleeding)” was written in the midst of the Vietnam War presided over by President Lyndon Johnson. But the song’s antiauthoritarianism has continued to speak to later generations, different conflicts, and subsequent heads of state.

Remember that we were only a year removed from the controversial presidential contest of 2000, a dead heat between Al Gore and George W. Bush. The Supreme Court ultimately intervened a month after the election. In the case of Bush v. Gore, the conservative majority ruled in a 5-4 decision that the Florida recount must halt, effectively deciding the outcome in Bush’s favor. He was inaugurated in January 2001, and before the year was out he was presiding over a combat mission against Al-Qaeda in Afghanistan.

As it turned out, these were only the early battles in a wider conflict he termed the “War on Terror,” which would eventually drag on longer than the Vietnam War. Different audience members had different reasons for cheering the line about the American emperor wearing no clothes; but it’s fair to presume that some of them were thinking of President Bush rather than President Johnson when they yelped their approval of Dylan’s defiant declaration.

The closing song of the first acoustic set is another stirring rendition of “Searching for a Soldier’s Grave.” In the previous chapter, I reflected at length on the powerful performance of this song at Riverbend in July 2000, considering its connection to the themes of mothers and mourning. The song strikes a different chord in November 2001 with the United States at war again.

There weren’t any American soldiers’ graves from this latest conflict yet, but they would come soon enough. The first official combat death of a U.S. soldier in Afghanistan was Sgt. Nathan Chapman, a Green Beret in the Special Forces, who was killed in action near Khost. Chapman was a few months short of his 32nd birthday when he died. I shuddered to discover that he died on January 4, 2002, which was my own 32nd birthday.

While researching this chapter, I came across a deeply moving NPR piece called “A Family Remembers the 1st U.S. Soldier Killed in the War in Afghanistan,” from a series commemorating the twentieth anniversary of 9/11. It’s a recorded conversation between Lynn and Keith Chapman, the mother and brother of Sgt. Nathan Chapman. I was bawling by the end of it, and it makes me appreciate this performance of “Searching for a Soldier’s Grave” in a new light. “You know, people take on a larger-than-life quality when things like this happen,” reflects Lynn Chapman. “But I think of him as a son and a child and then a soldier. I don’t see him as a symbol. In some way, that takes him away from me.” The solider in the song functions as a kind of symbol, too, in that he is meant to stand in as representative for the thousands of other soldiers who died far from home. And yet we know, and Dylan knows, that there is a human story behind each of these deaths, a story that lingers for the surviving family members.

Chapman’s brother Keith is haunted by regrets. Asked by his mother what he would tell Nathan now if he could, Keith admits,

There was an opportunity at his funeral to provide words to be spoken, but I wasn’t able to come up with what was really important. I’ve thought about it over the years, and the thing that I would say instead was that there were times when I thought of Nathan as less than me, and that I was wrong. There were times when I thought, and even said to him, that he would never amount to anything (chokes with emotion). And I was wrong. Everything he wanted to do was important and meaningful.

Lynn consoles her son: “It’s OK, Keith. I think a lot of siblings come to a greater understanding as they mature. Had you been given the time, you guys, you would have a chance to say everything you wanted. So that’s what’s really sad about somebody dying young. You lose all that future.” Powerful and heartbreaking. Frozen in time as forever young, but also forever out of reach.

Dylan didn’t write “Searching for a Soldier’s Grave,” but he knows what he’s doing in taking this song on the road and singing it to audiences at a time of war. Survivors often struggle to adequately express their loss and regret. We long for opportunities to grieve and to pay tribute. Sometimes we find what we need in unexpected places—like old songs—and unexpected occasions—like concerts. Reflecting in Chronicles on his motives for beginning the Never Ending Tour, Dylan writes, “It might be interesting to start up again, put myself in the service of the public” (153-54). I think of performances like the Cintas ’01 “Searching for a Soldier’s Grave” as public services.

“You ask me, stranger, why I made this journey,” sing Dylan, Campbell, and Sexton. The answer within the song is “I’m searching for his grave.” Aren’t we all searching for someone’s grave? Searching for that lost loved one, wishing like Lynn Chapman to remember them the way they really were? Wishing like Keith Chapman to reconcile and say what never got said before? Think of Dylan’s memories on the death of his father: “I had gone back to the town of my early years in a way I could never have imagined—to see my father laid to rest. Now there would be no way to say what I was never capable of saying before” (Chronicles 107).

Maybe we aren’t equal to the task, but the songs are. They give us words when we’re speechless; they communicate deep feelings viscerally through music. Songs shine a light to lead us through dark times. As Dylan told David Gates in his 1997 Newsweek interview,

I find the religiosity and philosophy in the music. I don’t find it anywhere else. Songs like ‘Let Me Rest on a Peaceful Mountain’ or ‘I Saw the Light’—that’s my religion. I don’t adhere to rabbis, preachers, evangelists, all of that. I’ve learned more from the songs than I’ve learned from any of this kind of entity. The songs are my lexicon. I believe the songs. (1193)

I believe them, too, when I hear Dylan and mates sing with such conviction, as they do in “Searching for a Soldier’s Grave.”

First Electric Set

In the first song of the electric set, this tug of war between light and dark gets staged on the metaphysical plane as a contest between good and evil, God vs. Satan—and you’re the rope. This was only the second time Dylan sang “Gotta Serve Somebody” in the fall of 2001, and he’d only dial it up once more on that tour. Xavier is a Jesuit university, so that might have factored into his selection for a Sunday night sermon on the Catholic campus. Tonight’s performance features a distinct arrangement where Dylan chops up the chorus into short segments:

You got to serve some

Serve somebody

Might be the Devil

Might be the Lord

But you

Know you

Got to

Serve somebody

He sings new lyrics at times:

Might be looking for somewhere

You can’t even find

Maybe you’re searching

For some peace of mind

Searching for some peace of mind by searching for a soldier’s grave? In the moment, standing at the top of an aisle at Cintas Center and grooving to the first electric song of the night, I didn’t notice this little linchpin subtly linking this song of service back to the preceding song of sacrifice and commemoration. Dylan may or may not have forged these links intentionally, but after playing these concerts night after night, I bet he picked up on the serendipities and synchronicities. One of the great pleasures of this Dylan in Cincinnati project is listening repeatedly to bootleg recordings, sometimes of concerts I attended live, and belatedly appreciating interconnections and resonances I overlooked the first time.

Dylan constantly renewed his commitment to movement, experimentation, and change through his variable song selections. This was a trademark feature of the NET from its beginning in 1988, and it remained a welcome treat for audiences in 2001. Take a look at Dylan’s setlist from his previous concert on November 3. Out of the first nine songs he played Saturday night in Nashville, only one song was repeated Sunday night in Cincinnati. You just don’t encounter this degree of variety in many other performers. Dylan hasn’t mixed up such a wide assortment of medicines in many years, but in 2001 you still never knew what you were going to get from the 60-year-old shaman on his never-ending, ever-changing tour.

The one song that remained consistent in Cincinnati from the starting nine in Nashville was “Floater (Too Much to Ask)” from “Love and Theft.” This is one of my favorites from the album, and the Cintas performance was only the fourth time he ever played it live. There’s no other Dylan song quite like it. Musically, it’s a pleasant shuffle and a throwback to another era. Kemper mentioned how the maestro immersed the band in early Americana, and “Floater (Too Much to Ask)” is a perfect example. The melody comes from the 1932 song “Snuggled on Your Shoulder (Cuddled in Your Arms),” composed by Carmen Lombardo and Joe Young. It has been covered by the likes of Bing Crosby, Kate Smith, Julie London, and Cincinnati native Doris Day, but Dylan’s arrangement sounds closest to crooner Al Bowlly’s rendition.

“Floater” conjures images of Huck Finn sitting on his raft with a strand of straw in his mouth and a fishing pole in his hand, basking in the humid summer heat. Lyrically, it’s a grab-bag of references from an eclectic array of sources, a miniature vaudeville variety show (or perhaps minstrel show) with jokes, bits of Shakespeare and Christmas carols, cornpone wisdom, and Civil War references, all floating up a lazy musical river like flotsam and jetsam on the stream of life. Cincinnati is situated on the shores of the Ohio River, so this line earned a cheer from the Cintas audience: “They went down the Ohio, the Cumberland, the Tennessee / All the rest of them rebel rivers.”

Vocally, Dylan presents a master class in phrasing and pacing. He has an astounding gift for maintaining the steady rhythm of the song despite the fact that some verses contain twice as many words as others. No one else would write a song like “Floater,” and no one else could sing it like Dylan.

“Floater” builds upon the light/dark imagery so central to the Cintas ’01 setlist. Dylan begins by establishing the protagonist’s sunny disposition. The song literally begins in the sun:

Down over the window

Comes the dazzling sunlit rays

Through the back alleys—through the blinds

Another one of them endless days

We wander with the singer through one of those endless summer days, as he wakes and greets the sun, grabs his pole, and wanders down to his favorite fishing hole. Despite the apparent tranquility of this sun-drenched period piece, several lyrics suggest that the singer is beset by darker threats.

The paranoid fisherman behaves like someone in the witness protection program. He peeks suspiciously through the closed blinds, then slinks through the back alleys trying to avoid detection: “I keep listenin’ for footsteps / But I ain’t hearing any.” The coast may be clear for now, but “A squall is settin’ in.” Fights are brewing between the old and young, between the bosses and workers, between the lords and vassals. This singer is no stranger to trouble, and he won’t back down from a fight:

If you ever try to interfere with me or cross my path again

You do so at the peril of your own life

I’m not quite as cool or forgiving as I sound

I’ve seen enough heartaches and strife

And yet, for all his worries and disappointments, the protagonist of “Floater” is a resilient survivor inclined to take things in stride and accept the crookeds with the straights. In the middle of the song he remarks,

They say times are hard, if you don’t believe it

You can follow your nose

It don’t bother me—times are hard everywhere

We’ll just have to see how it goes

If the opening song was one of hope and faith, then this sixth song is more about endurance and composure when the troubles are closing in and hard times come scratching at the door, as they were for the city and the nation in 2001. “Floater (Too Much to Ask)” is an intriguing song when considered in isolation, but it’s even more interesting considered within these troubled contexts.

Dylan had a sweet tooth in Cincinnati, not for our famous Graeter’s ice cream, but for “Country Pie.” He served a slice of this deep cut from Nashville Skyline at his Riverbend ’00 concert, and liked it so much he came back for seconds at Cintas ’01. The hip-shaking country-rock arrangement injects a surge of adrenaline. “Floater” drifts languidly downstream in the summer heat, and then “Country Pie” blasts by on a speedboat and tips Huck’s raft in its wake.

The contrast brings to mind something Dylan told Robert Hilburn about “Love and Theft.” In an interview for the Los Angeles Times, he highlighted a key difference from Time Out of Mind:

I knew after that record that when and if I ever committed myself to making another record, I didn’t want to get caught short without up-tempo songs. A lot of my songs are slow ballads. I can gut-wrench a lot out of them. But if you put a lot of them on a record, they’ll fade into one another, and there was some of that in Time Out of Mind. I sort of blueprinted it this time to make sure I didn’t get caught without up-tempo songs. If you hear any difference on this record—why it might flow better—it’s because as soon as an up-tempo song comes over, then it’s slowed down, then back up again. There’s more pacing. (1312)

In other words, producer Jack Frost arranged L&T much the same way that bandleader Bob Dylan orchestrates his setlists. “Country Pie” picks up the pace after “Floater,” and it sets the stage for the most gut-wrenching slow ballad of the concert.

“Sugar Baby” is absolutely riveting! This closing song from “Love and Theft” is fierce and chilling on the album, but the live performance at Xavier drags any competing version’s corpse through the mud. I was dissing Dylan’s voice earlier, but now he couldn’t sound better. Something evil this way comes. He completely and convincingly inhabits the burned-out, world-weary character who rues his faithless Sugar Baby in this deeply bitter song. Garnier lays down a mean bass line, Kemper adds well-placed embellishments here and there on cymbals, and Sexton and Campbell lay low and let Dylan slay the crowd with his lethal vocals. You’re gonna want to hear this one:

“Sugar Baby” is “Idiot Wind” as sung by a 500-year-old vampire. Lyrically, it’s a hateful song, specifically a woman-hating song. The chorus is laced with sexist scorn:

Sugar Baby get on down the road

You ain’t got no brains no how

You went years without me

Might as well keep going now

And this textbook definition of misogyny speaks for itself: “There ain’t no limit to the amount of trouble women bring.” Several dudes audible on the bootleg hoot and grunt their approval. In One More Night: Bob Dylan’s Never Ending Tour, Andrew Muir traces this call-and-response pattern from other audiences as well. He describes the general awe with which fans greeted “Sugar Baby,” but then adds this asterisk:

I say reverential silence, but this song was often ruined by male whooping and hollering after the lines about women bringing trouble. It sounded more like a reaction of a crowd to ice hockey players clashing violently than anything else, a sad thing to hear in the midst of Dylan’s intense concentration on singing this sublime and complex work. (275)

A work of art can contain vile sentiments without endorsing those views. What salvages “Sugar Baby” from simple-minded sexism and elevates it to a “sublime and complex work” is not only Dylan’s gripping performance as vocalist, but also his intertextual dialogues with Dock Boggs as lyricist and with Greil Marcus as cultural historian. Dylan recently set his social media followers abuzz with an Instagram post celebrating Dock Boggs on his 126th birthday (February 7, 2024). As Marcus establishes in The Old, Weird America, his remarkable book about the musical, historical, and cultural antecedents of The Basement Tapes, Dylan has been a Boggs disciple since his youth.

Referring to specific Boggs songs that influenced Dylan like “Sugar Baby,” “Country Blues,” “Down South Blues,” “Danville Girl,” and “Pretty Polly,” Marcus declares:

Dock Boggs made primitive-modernist music about death. Primitive because the music was put together out of junk you could find in anyone’s yard, hand-me-down melodies, folk-lyric fragments, pieces of Child ballads, mail-order instruments, and the new women’s blues records they were making in the northern cities in the early years of the 1920s; modernist because the music was about the choices you made in a world a disinterested god had plainly left to its own devices, where you were thrown completely back on yourself, a world where only art or revolution, the symbolic remaking of the world, could take you out of yourself. (148-49)

Marcus goes on to assert: “Boggs’s music accepted death, sympathized with its mission, embraced its seductions, and traveled with its wiles” (149). The exact same descriptions could be applied to Dylan’s “Sugar Baby.”

We know that Dylan was familiar with Marcus’s book (originally published in 1997 under the name Invisible Republic) because he offered an enigmatic blurb: “This book is terminal, goes deeply into the subconscious and plows through that period of time like a rake. Greil Marcus has done it again.” Marcus exhumed the late musician from the subconscious, then the aging rocker/mad scientist reassembled the salvaged parts into “Sugar Baby” (aka “My Own Version of Boggs”). Dylan channels the man Marcus describes as “a coal miner, a bootlegger, and a churchgoer in his ordinary life and a killer in his art, Boggs told a story of estrangement and sorrow, crime and no regret” (150).

“Sugar Baby” is a character study, and Dylan relishes playing the role of a sinister antagonist, milking every ounce of venom from this creeper. Boggs never comes out and threatens his lover directly, but he sure as hell implies it. When he sings, “I’ve got no honey baby now / I’ve got no sugar baby now,” it could mean she left him, or it could mean that he followed through on his vow to send her back home to her mother. But it could also mean that he sent her to her grave. The same implied threat comes through in the last verse of Dylan’s “Sugar Baby”:

Your charms have broken many a heart

And mine is surely one

You got a way of tearing a world apart, love

See what you have done

Just as sure we’re living

Just as sure as you’re born

Look up, look up—seek your Maker

’Fore Gabriel blows his horn

The words and melody here closely resemble Gene Austin’s 1927 song “The Lonesome Road,” but the mood is cooked up in Boggs’s country kitchen, seasoned with a dash of Othello urging Desdemona to say her prayers before he smothers her to death.

In Greil Marcus’s album review of “Love and Theft” for The Guardian, he describes the persona Dylan adopts as not so much a menacing killer as a notorious crank and town eccentric: “Sometimes he sounds crazy, but the same sound can be seductive, especially in his seeming disdain for all those he wants dead, banished, out of his world. You catch something strange and glamorous in his voice: how you might feel if you had the nerve to talk like this.” The crazy/seductive old man speaks in a language he learned from old records:

Some people will remember how the man used to take out an album by a stone-faced character named Dock Boggs, a singer from the Virginia mountains who first recorded in 1927, the man would carefully explain; he’d play a song called Sugar Baby. That was real killer-inside-me stuff; Sugar Baby was what Boggs called his lover, who you weren’t sure would survive the song.

Although the L&T character seems at times like a cut-rate parody of Boggs, Marcus insists that they grow out of the same existential soil:

The feeling, though—the sense of a life used up, wasted as every life is finally wasted, leaving the earth as if one’s life had never been—is the same. The feeling is that there is all the time in the world to take stock, if only in the ledger you keep in your heart to settle accounts, to tell jokes you half hope no one will get. […] You laugh, and then something in his tone pulls you down into the emptiness he’s speaking from.

In essence, Marcus claims that “Love and Theft” is as much a byproduct of “old, weird America” as The Basement Tapes, now a little older and weirder, a patchwork quilt stitched from tragedy and farce. “Sugar Baby” is an American tall tale, the preferred mode of Boggs, Dylan, and Marcus.

I got my back to the sun ’cause the light is too intense

I can see what everybody in the world is up against

You can’t turn back—you can’t come back, sometimes we push too far

One day you’ll open up your eyes and you’ll see where we are

Wherever Dylan sings it, he turns that spot into the house of the setting sun; whenever he sings it, he turns that moment into ruination day. The singer may speak from a place of emptiness, as Marcus asserts, but if we follow Dylan down that vortex we discover a darkness buzzing with the murmur of dead voices.

Second Acoustic Set

Some of those dead voices belong to Dylan’s past selves. Like a spiritual medium at a séance, he channels one of those past selves in the next song. Having just turned his back to the sun and rejected hard-hearted Sugar Baby, he conjures up a song from nearly forty years earlier based upon an identical situation:

It ain’t no use in turnin’ on your light, babe

The light I never knowed

Ain’t no use in turnin’ on your light, babe

I’m on the dark side of the road

In “Don’t Think Twice, It’s Alright” the singer is passive aggressive, claiming not to be hurt and not to care, even though we can tell that he really is suffering and just puts up a tough-guy front.

I ain’t saying you treated me unkind

You could’ve done better but I don’t mind

Kind of wasted all of my precious time

But don’t think twice, it’s all right

In “Sugar Baby,” there’s nothing passive about the singer’s aggression—he is nakedly hostile. The dismissive attitude toward the infantilized women remains consistent, even though the traveling roles are reversed. In “Don’t Think Twice,” he is the one driven from his home and set to wander the dark roads; in “Sugar Baby” she is the one walking the streets while he sulks and seethes around the hearth, tightening his robe and cranking up the thermostat.

Although the two songs aren’t that far apart lyrically, the infectious joy of the music in “Don’t Think Twice” keeps the darkness at bay. Dylan’s Cintas ’01 performance is incandescent. Even before he sings a word, he has already enchanted the audience with his gorgeous acoustic guitar intro. After the final verse, the song turns into a real guitar jam, with Dylan joining for a crowd-pleasing harmonica solo. They wind down with a slow-motion arrangement of the final bars of the song, driving the Xavier crowd totally bonkers.

After three songs in a row about falling in and out of love with a woman, Dylan pivots to a different kind of relationship gone terribly wrong: a son misled by his mother, and a soldier betrayed by his country. “John Brown” is about a soldier who goes off to war with the encouragement of his mother, fully expecting to return a hero with lots of medals on his chest and a bright future ahead of him after his country triumphs against its enemies. Dylan wrote the song in 1962 during the buildup to the Vietnam War, but he didn’t release it until the first Bootleg series in March 1991, the month after the First Gulf War concluded.

Another President Bush was in the White House in 2001, and America was at war again. The setlist shows that the conflict was very much on Dylan’s mind. This was the third night in a row that he played “John Brown.” It would turn out to be his only performance of the song in Cincinnati.

It’s fair to presume that many concert attendees were unfamiliar with this song since it had never appeared on any of Dylan’s studio albums. “John Brown” is an unflinching portrait of a traumatized soldier. He departs from home a patriot but returns disfigured and disillusioned, feeling abandoned by his family and his country. The song builds to a devastating climax with the blind and maimed soldier confronting his mother, rejecting the hawkish nationalism that led him to war, and dropping his unwanted medals into her hand. “John Brown” is one of the most searing anti-war songs I’ve ever heard. Like a touring actor with a bottomless trunk of scripts and masks, Dylan fully commits to his performance as an embittered veteran, snarling at the violence, exploitation, futility, and irredeemable waste of war. Which war? Take your pick. Dylan doesn’t have to give speeches or distribute pamphlets to express his views on the current conflict, or the previous one, or the next. The song says it all for him.

On one occasion, however, Dylan did let the mask slip to interject his personal thoughts on “John Brown.” He introduced the song in Portland in 1990 with a dedication: “I’d like to dedicate this next song to all prisoners of war . . . today, and every other day” (qtd Williams 288). Paul Williams delves into this splendid concert in the final volume of his Performing Artist series. He recognizes that Dylan’s comment was not simply a reference to POWs, though it includes them, too. Rather, as Williams puts it, “this is indeed a song of empathy for ‘prisoners of war’—young people waking up to find themselves soldiers, trapped in a foreign and very hostile environment, at constant risk of losing their lives or (as in this case) their ability to walk or talk or see. With no opportunity to even try to escape. Prisoners indeed” (288).

Second Electric Set

After closing the acoustic set with a sloppy and forgettable “Tangled Up in Blue,” Dylan and mates plug back in with “Summer Days.” This joyous jitterbug from “Love and Theft” is a throwback to the sock hops of Dylan’s teen years in the 1950s. As he sings in “Summer Days,” echoing Jay Gatsby, “She says, ‘You can’t repeat the past.’ I say, ‘You can’t? / What do you mean you can’t? / Of course you can.’” Dylan sounds like he’s having a blast playing this up-tempo boogie-woogie. The old guy has still got it, and he knows it: “How can you say you love someone else when you know it’s me all the time?”

This song also showcases Dylan’s sense of humor, an endearing signature of “Love and Theft.” He has the perfect comic timing of a vaudeville veteran. What a distance Dylan travels, and what a performative range he displays, from the brooding melancholy of “Sugar Baby” [“I got my back to the sun ’cause the light is too intense”] to the Henny Youngman one-liners of “Summer Days” [“Well, my back has been to the wall for so long it seems like it’s stuck / Why don’t you break my heart one more time just for good luck”]. The band is firing on all cylinders, too. The final line sounds like Dylan’s own concert review: “I know a place where there’s still somethin’ goin’ on.” Me too: the Cintas Center on November 4, 2001.

These themes of variety and range apply to Dylan’s song distribution in the setlist as well. It’s not just that he alternates between up-tempo numbers and slow ballads. He also includes samples from across the long span of his career. By my count, thirteen different albums/releases are represented in the Cintas setlist, plus two cover songs. His rationing is fairly balanced, with no record getting more than two songs—except for “Love and Theft,” which gets five. He is clearly proud of the new record and wants to show it off. He features back-to-back L&T tracks with his next performance, the mighty “Mississippi,” one of the best songs he ever wrote. Dylan polished this precious gem in concert a relatively modest 75 times before retiring it to his treasure chest in 2012. He knew he had something special with “Mississippi,” and he doled it out sparingly. He blessed the Xavier audience with just his eighth live performance ever, and it remains his only Cincinnati performance of this masterpiece.

“Mississippi” was initially written and recorded for Time Out of Mind, but Dylan withheld it because of irreconcilable creative differences with his co-producer, saving it instead for his follow-up “Love and Theft.” A couple weeks after the new record’s release, Dylan publicly repudiated his collaborator in Rolling Stone for mishandling “Mississippi.” Ever since this hatchet job, the song has come to epitomize the contrasting production principles of Daniel Lanois and Jack Frost.

Recalling their clash over “Mississippi” during the TOOM sessions, Dylan told David Fricke, “The song was pretty much laid out intact melodically, lyrically and structurally, but Lanois didn’t see it. Thought it was pedestrian. Took it down the Afro-polyrhythm route—multirhythm drumming, that sort of thing. Polyrhythm has its place, but it doesn’t work for knifelike lyrics trying to convey majesty and heroism” (1318). Does that clear up their creative differences for you? No? Then let Dylan muddy the waters further for you:

I tried to explain that the song had more to do with the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution and the Bill of Rights than witch doctors, and just couldn’t be thought of as some kind of ideological voodoo thing. But he had his own way of looking at things, and in the end I had to reject this because I thought too highly of the expressive meaning behind the lyrics to bury them in some steamy cauldron of drum theory. (Fricke 1318)

What a take down! Dylan’s poisonous cocktail is mixed with equal portions of epic burn, hilarious inscrutability, chest-thumping sibling rivalry, and shameless self-promotion at a friend’s expense. But those seemingly random references to foundational American documents may point in an old, weird way to the ambitious scope of this deeply American song.

As I argue in my book Dreams and Dialogues in Dylan’s Time Out of Mind, I hear “Mississippi” as a dream-song rooted in the legacy of slavery and the centuries-long struggle by African Americans to achieve a full and equal measure of the American promise of freedom. Within its initial context for Time Out of Mind, “Mississippi” depicts a dreamer imagining his way into a fugitive slave narrative, crossing the river in pursuit of Rosie, that emblematic Lady Liberty sung about in prison songs from Mississippi’s notorious Parchman Farm. Within the context of “Love and Theft,” “Mississippi” is Dylan’s meditation on his debts to Black history, culture, and music. Within the context of his Cintas concert, “Mississippi” is one of several songs reflecting upon the causes and costs of American wars, first and foremost the Civil War.

These are bold and controversial moves on Dylan’s part—or at least they would have been controversial, had anyone bothered to notice what he was up to. Having gotten away with it undetected on Time Out of Mind, he drew extra attention to his project by naming “Love and Theft” explicitly after a book on blackface minstrelsy. Plenty of reviewers and critics commented on that fact, but then most let the matter rest there, without interrogating the ways Dylan enacts, through a combination of love and theft, his own cross-racial performances of Black experiences.

What’s most interesting to me is the way Dylan merges voices and perspectives together in “Mississippi.” The song is the product of Rimbaud’s formula “Je est un autre” [“I is an Other”]. At times, “Mississippi” sounds like a highly personal song where the first-person speaker is Bob Dylan himself. The first verse sounds like self-commentary on his own career: “I was raised in the country, I been workin’ in the town / I been in trouble ever since I set my suitcase down.” In the last verse, he seems to be issuing a personal statement about his sustaining love for music and his admiration for those who have helped him make that music and share it with audiences across the globe: “But my heart is not weary, it’s light and it’s free / I’ve got nothin’ but affection for all those who’ve sailed with me.” And the last lines before the final refrain must ring all too true for this sixties legend: “You can always come back, but you can’t come back all the way.”

On the other hand, the circumstances being described in each verse also reflect key chapters in African American history: the Great Migration to the North in verse one; the Jim Crow South in general and Parchman Farm specifically in verse two; and the Middle Passage from Africa across the Atlantic on a collision course with America in verse three. “Time is piling up” indeed; “I’m trapped in the heart of it, trying to get away.” Mississippi isn’t just a state but a state of mind, a mythical realm and metaphysical condition, a primal setting for the perpetual pursuit of elusive Freedom.

Don’t get me wrong: I’m not denying that Dylan is personally invested in this song, nor do I think it’s a matter of choosing the single, correct interpretation. All great works of art are capable of meaning more than one thing, even contradictory things, at the same time. Dylan merges himself into the character he sings, not just in “Mississippi” but in all of his best songs. Two become One and One becomes Two. Through the alchemy of performance, I is an Other.

Dylan follows up “Mississippi” with another song from the TOOM sessions, “Cold Irons Bound.” As the shackles of the title indicate, this is another song drawing upon imagery of slavery and imprisonment, in this case apparently the arrest and incarceration of a fugitive: “I’m twenty miles out of town in cold irons bound.”

That’s what’s going on lyrically in the song, but what’s most remarkable tonight is the sound of the song. There is a paradoxical kind of controlled cacophony at first. I’m reminded of the musicians in a symphony warming up before a concert, doing their own thing individually and sounding totally out of sync collectively, before suddenly coming together in perfectly orchestrated harmony. In the case of “Cold Irons Bound,” the anarchy appears to be a calculated effect, beginning with the assembly of ingredients for an incendiary device and culminating in its detonation. Or if that analogy doesn’t work for you, then try this one: it’s like Dylan and comrades are packing their gear and loading their weapons before heading into battle.

The mesmerizing percussions set the time-bomb ticking, the bass and guitars enter to ratchet up the tension, and the sound gradually builds toward an explosion. Several of the songs in this setlist comment upon war. Lyrically, this song is not one of them. But sonically “Cold Irons Bound” sounds like a firefight in guerilla combat against a hidden enemy. It runs hot and cold, with periodic exchanges of rapid fire separated by relatively calm interludes before launching the next attack. Dylan is on point with his vocals and guitar, serving as the platoon leader for this night raid. The bandleader rallies his troops for their most rousing musical assault of the night. Dylan has played this song live over 400 times, but this is his only Cincinnati performance. He sure makes it a memorable one. Hot irons unbound is more like it!

For the final song of the second electric set, Dylan calls a ceasefire and whips out his peace pipe: “Everybody must get stoned!”

Yes, yes, calm down, I know: the lyrics seem to be referring more directly to the ancient biblical practice of stoning as a form of communal punishment. Dylan had lots of experience with rebellion and knew all too well the price one paid for it. But come on, who are we kidding, he also knows a hell of a lot about the other kind of getting stoned, and so do plenty of his fans, including several rambunctious merrymakers in the vicinity of the bootlegger. I suppose it’s a harmless way to pass the time while waiting for the light to shine. “Rainy Day Women #12 & 35” is a dependable crowd-pleaser, and it’s just the right up-tempo song to conclude the concert proper before transitioning into the encore section.

Encores

Judging by the sheer quantity of performances, Dylan’s favorite 21st century song is “Things Have Changed.” He has played it over a thousand times, including the first encore number at Xavier. As the singer repeatedly informs us, “I used to care, but things have changed.” What does this mean? It sounds like cynical resignation, and maybe it is, but that’s not the only way to play it. An alternate interpretation is that the grizzled singer no longer concerns himself with petty distractions which once weighed him down. If people are now crazy and times are unfathomably strange, then maybe it’s a good idea to be out of range from the madness, to have achieved escape velocity from the bullshit. “I used to care, but things have changed” may be the equivalent of “Frankly, my dear, I don’t give a damn.”

One thing Dylan does care about is singing the hell out of this song. He has a lot of fun fluctuating his voice and stretching his range. He weaves and swerves but never crashes against the guardrails of the beat. If anything, his vocals fortify the rhythm, stressing certain syllables like he’s keeping time on a drum:

PEE-ple are crazy, TIMES are strange

I’m LOCK’d in tight, I’m OUT of range

I YOOS’d to care, YEAH, but things have changed

Dylan & Co. get down in the groove on “Things Have Changed,” and I totally dig it. This may be the best performance of the song I’ve ever heard.

Dylan follows “Things Have Changed” with “Like a Rolling Stone.” Back in the old days, he rode this song like rocket ship to blast through the rafters. In later years, as in the Riverbend ’00 performance, the song sometimes lacked the energy to make it off the launchpad. The Cintas ’01 performance splits the difference.

Dylan and the band never kick into turbo-drive on “Rolling Stone,” but they don’t roll over and play dead either. His vocal is introspective, suggesting the singer feels empathy for Miss Lonely from the start and is concerned about her downfall. But he doesn’t let the song lapse into maudlin sentimentality, and the band keeps the musical pulse pumping. Dylan finds a new entry point into his old classic, different than familiar pathways from the past, but one that still gets him where he’s going.

Dylan follows “Like a Rolling Stone” with the poignant prayer “Forever Young.” This is the first time he played “Forever Young” in Cincinnati in twenty years.

Dylan’s phrasing is so delicate and tender. Then Campbell and Sexton join in, strapping the song to their backs and soaring into the heavens. I’ve always loved the rendition by Dylan and The Band in the film The Last Waltz, but I’m ready to declare this version even better. They really stretch the words out and hold their notes in the refrain, and the effect is exquisite. Lovely guitar playing as well. What a transcendent performance of a beautiful hymn.

Time to shift gears with an up-tempo song, so Dylan introduces “Honest Me,” his fifth and final “Love and Theft” song of the night. His voice, which was pretty rough at the top of the show, improved as he got loosened up. However, by this nineteenth song his vocal chords are feeling the strain. The Wolfman is growling on “Honest with Me.”

The band is still in great shape and sound like they could go all night. Dylan throws himself into the fray, but he’s running out of vocal ammunition. To use his own words from this song against him: “I’m glad I fought—I only wish we’d won.”

By the way, that line is sometimes seen as Dylan’s self-defense for the civil rights era and his contributions to the righteous cause. Maybe. But you’ll never hear it the same way again once you learn that the lines come from a song called “Oh I’m a Good Old Rebel.” Look up the lyrics, written by unreconstructed Confederate officer James Innes Randolph, and you’ll find an unabashed defense of the “Lost Cause” ideology:

Oh I’m a good old rebel

Now that’s just what I am

And for this Yankee nation

I do not care a damn

I’m glad I fought again’ her

I only wish we’d won

I ain’t asked any pardon

For anything I done

Hmmm. That’s a very different take on “I used to care, but things have changed.” It’s also a stark contrast from channeling the African American freedom struggle in “Mississippi.” Dylan was just beginning his dalliance with Confederate poets; he would sneak in multiple quotations from Henry Timrod, the so-called “Laureate of the Confederacy,” in his next album Modern Times (2006). But I’m getting ahead of myself. For now, let’s just say that Dylan adopts some dubious masks in “Love and Theft,” and some would’ve been better left in the ashbin of history where he found them.

I’d be surprised if anyone in the arena had ever heard of James Innes Randolph or picked up on the buried allusion to “Oh I’m a Good Old Rebel.” But I’ll wager that every single ticketholder knew and loved “Blowin’ in the Wind” and were delighted to hear this revered civil rights anthem in the encore.

It’s also a timely remedy for Dylan’s flagging voice, with vocal booster shots courtesy of Campbell and Sexton. The boss quietly delivers each verse, then his trusty lieutenants join on the chorus, providing a power surge equivalent to Popeye gobbling down a can of spinach. Campbell deserves special credit. Over his tenure in the band (1997-2004), he blossomed as multi-instrumentalist and singer. I’m not alone in considering this lineup—Campbell, Sexton, Garnier, and Kemper—as the A team of the NET. I’d rather hear Dylan sing alongside Campbell than any duet partner he’s ever had, with the possible exception of Clydie King. Listen to “Forever Young” and “Blowin’ in the Wind” in the Cintas ’01 encore, and you’ll hear why.

When the band exited after “Blowin’ in the Wind,” I figured the concert was over. But after a brief pause the guys come back out for one final number: a tempestuous “All Along the Watchtower.” It’s a hard-bitten version with a driving beat and propulsive forward momentum, charging headlong into the fog of war.

Dylan’s original 1967 version smoldered with foreboding, and then Jimi Hendrix threw jet fuel on the fire with his incendiary electric version. The song became part of the soundtrack for the Vietnam War, warning of an apocalyptic reckoning on the horizon. By closing the concert with “All Along the Watchtower,” Dylan drafts the song back into service as an ominous harbinger for things to come in America’s latest war.

Dylan repeats the opening verse at the end of “All Along the Watchtower.” The effect is curious. The construction of the song is unusual to begin with, unfolding in reverse and turning back on itself, so that the final verse is chronologically first. In other words, the two riders approaching the watchtower in the final verse are the joker and the thief who arrived in the first. Repeating that verse, as Dylan does tonight, accentuates the closed structure of the song, round and round the watchtower, looking for an escape: “‘There must be some way out of here,’ said the joker to the thief / ‘There’s too much confusion, I can’t get no relief.’” No relief and no exit. To repeat the first verse is to start the song over, taking another lap around an endless loop. Here we go again. Within the context of 9/11 and the ensuing war that was already under way, the song speaks to fears about America repeating the same mistakes in Afghanistan (and later Iraq) that had led to the tragic quagmire in Vietnam. John Fogerty would capture this concern perfectly a few years later in his song “Deja Vu (All Over Again),” but I also pick up on that foreboding sense of déjà vu in Dylan’s Cassandra-like performance of “All Along the Watchtower” at Xavier in 2001.

Imagine how different the effect would have been had Dylan ended with “Blowin’ in the Wind” instead of “All Along the Watchtower.” The early-sixties anthem is infused with hope that solutions to age-old problems may finally be within grasp for the younger generation: “The answers are blowin’ in the wind.” By the late-sixties, however, so much of that promise had been squandered, converted into frustration, disappointment, and rage. Dylan began this concert with an affirmation in “Wait for the Light to Shine.” Things may seem dire now, but just wait, the sun will come out tomorrow and dispel the dark times. Had he closed with “Blowin’ in the Wind,” he could have reinforced this rallying cry of guarded optimism. Instead he ends with the anxious premonitions of “All Along the Watchtower.” He couldn’t have chosen a less reassuring song. The view from the citadel shows the darkness gathering. A storm was blowin’ in the wind and headed right for us.

Works Cited

Bootleg audio recording (LB-0828). Taper unknown. The Cintas Center, Xavier University, Cincinnati (4 November 2001).

Dylan, Bob. Chronicles, Volume One. Simon & Schuster, 2004.

---. Song Lyrics. The Official Bob Dylan Website.

https://www.bobdylan.com/.

Fricke, David. “The Making of Dylan’s ‘Love and Theft.’” Rolling Stone (27 September 2001). Every Mind Polluting Word: Assorted Bob Dylan Utterances. Ed. Artur Jarosinski. Don’t Ya Tell Henry, 2006.

Gates, David. “Dylan Revisited.” Newsweek (6 October 1997). Every Mind Polluting Word: Assorted Bob Dylan Utterances. Ed. Artur Jarosinski. Don’t Ya Tell Henry, 2006.

Gray, Michael. The Bob Dylan Encyclopedia, corrected and updated edition. Continuum, 2008.

Hilburn, Robert. “How Does It Feel? Don’t Ask.” Los Angeles Times (16 September 2001). Every Mind Polluting Word: Assorted Bob Dylan Utterances. Ed. Artur Jarosinski. Don’t Ya Tell Henry, 2006.

Lott, Eric. Black Mirror: The Cultural Contradictions of American Racism. Belknap Press, 2017.

Marcus, Greil. “Bringing the deep south back home,” The Guardian (7 September 2001). https://www.theguardian.com/theguardian/2001/sep/08/weekend7.weekend8.

---. The Old, Weird America: The World of Bob Dylan’s Basement Tapes, updated edition. Picador, 2011.

McKay, Alistair. Interview with David Kemper. Uncut (24 October 2008). https://www.uncut.co.uk/features/bob-dylan-behind-the-scenes-of-tell-tale-signs-part-12-37864/.

Muir, Andrew. One More Night: Bob Dylan’s Never Ending Tour. CreateSpace, 2013.

Varias, Chris. “New material makes for classic Dylan,” Cincinnati Enquirer (6 November 2001): C-1.

Williams, Paul. Bob Dylan, Performing Artist, 1986-1990 & Beyond: Mind Out of Time. Omnibus, 2005.

Graley, another terrific essay - or novella, but who’s counting? What you have written here about Dylan’s messaging on war and race is fascinating as always. I was watching the video of him performing Change Gonna Come at the Apollo theater celebration. I was struck by not only the power of his interpretation but how it combined in performance with his own status in our culture to create a sense of something beyond performance. For someone who eschews politics, in performance he says a lot.

I forgot to mention how insightful and precise your distinction between the way the TOOM and L&T work: that distinction was very valuable to read!