Dylan in Prison

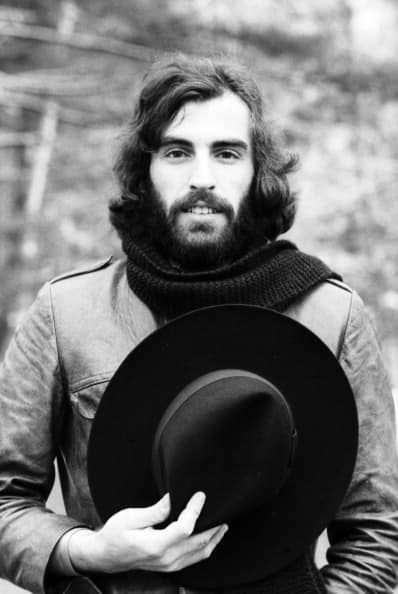

For the last several months I’ve been obsessed (again) with the Basement Tapes. I’m part of the monthly “Million $ Bash Roundtable” on Jim Salvucci’s The Dylantantes, and we recently recorded two extensive conversations about the Basement Tapes, one on the covers and another on the originals. Preparing for those podcasts gave me a welcome excuse to re-immerse myself in one of my favorite periods in Dylan’s entire career.

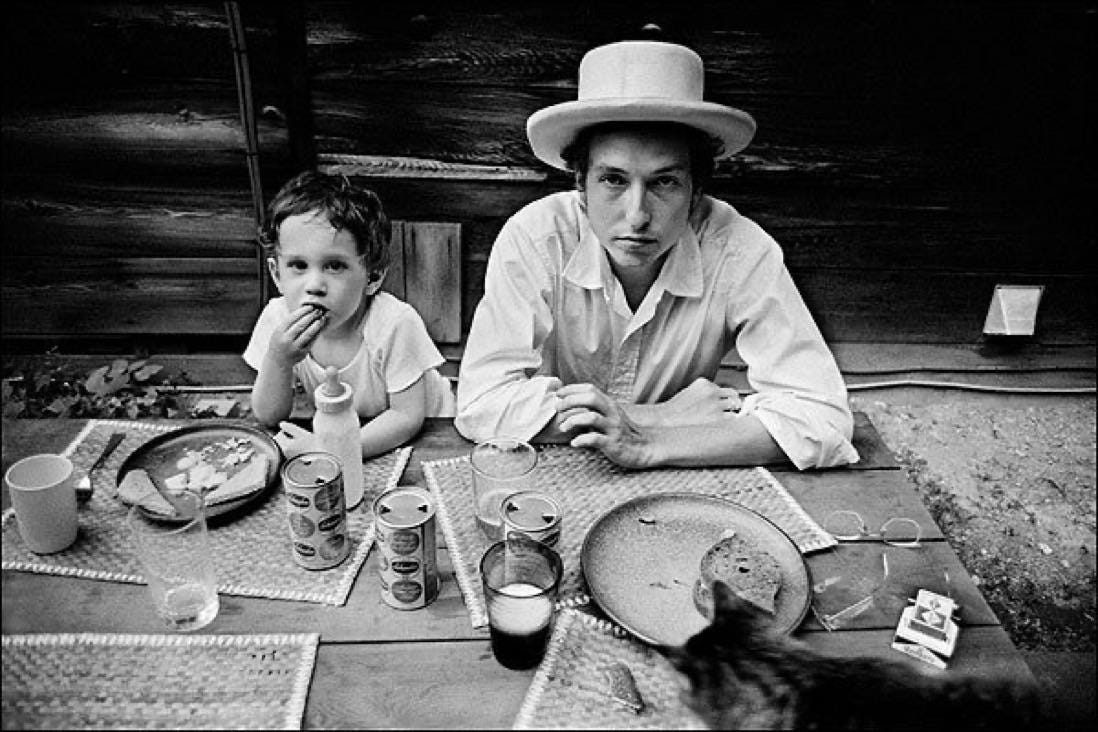

Even before those virtual roundtables, my good friend Erin Callahan reignited the spark with her excellent paper at the Denmark symposium on Dylan and masculinity. In her presentation on “Mixing Up the Medicine: Bob Dylan’s Basement Carnival and Homosocial Masculinity,” Erin described the period in terms of escape and sanctuary. She argued, “Domestic life with Sara and the children afforded Dylan a respite from that frenetic pace, but it changed Dylan’s connection to his creative identity, the source of his mode of production.”

Although the domestic sphere felt like a refuge at first, it didn’t take long before Dylan needed a sanctuary from his sanctuary. As Erin put it, home became “the space he must escape when he goes to the masculine environment of Big Pink.” Enter the Basement: “The all-boys ‘clubhouse’ in the basement at Big Pink provided a physical space for Dylan to escape domestic life.” However, Dylan being Dylan, these blissful conditions were short-lived and it came time to flee again. No matter the address, if the restless wanderer cools his heels anywhere for long then it turns into a prison that he must escape.

Thinking about this pattern led me to revisit Dylan’s prison songs of the 1960s. Early in his career, he penned two underrated portraits of prison life, “Ballad of Donald White” and “Walls of Red Wing.” He also alluded to prisoners in songs as various as “Percy’s Song,” “Seven Curses,” “The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll,” “Chimes of Freedom,” and “Bob Dylan’s 115th Dream.” The prison dynamic is particularly pronounced on Blonde on Blonde. Whether literally incarcerated like the frustrated inmate in “Absolutely Sweet Marie,” or figurately stranded in a seemingly inescapable, mind-bending, wheel-spinning lifestyle like the singer in “Stuck Inside of Mobile with the Memphis Blues Again,” this album sends signals through the fog and amphetamines: get out of here before it kills you.

The Basement Tapes

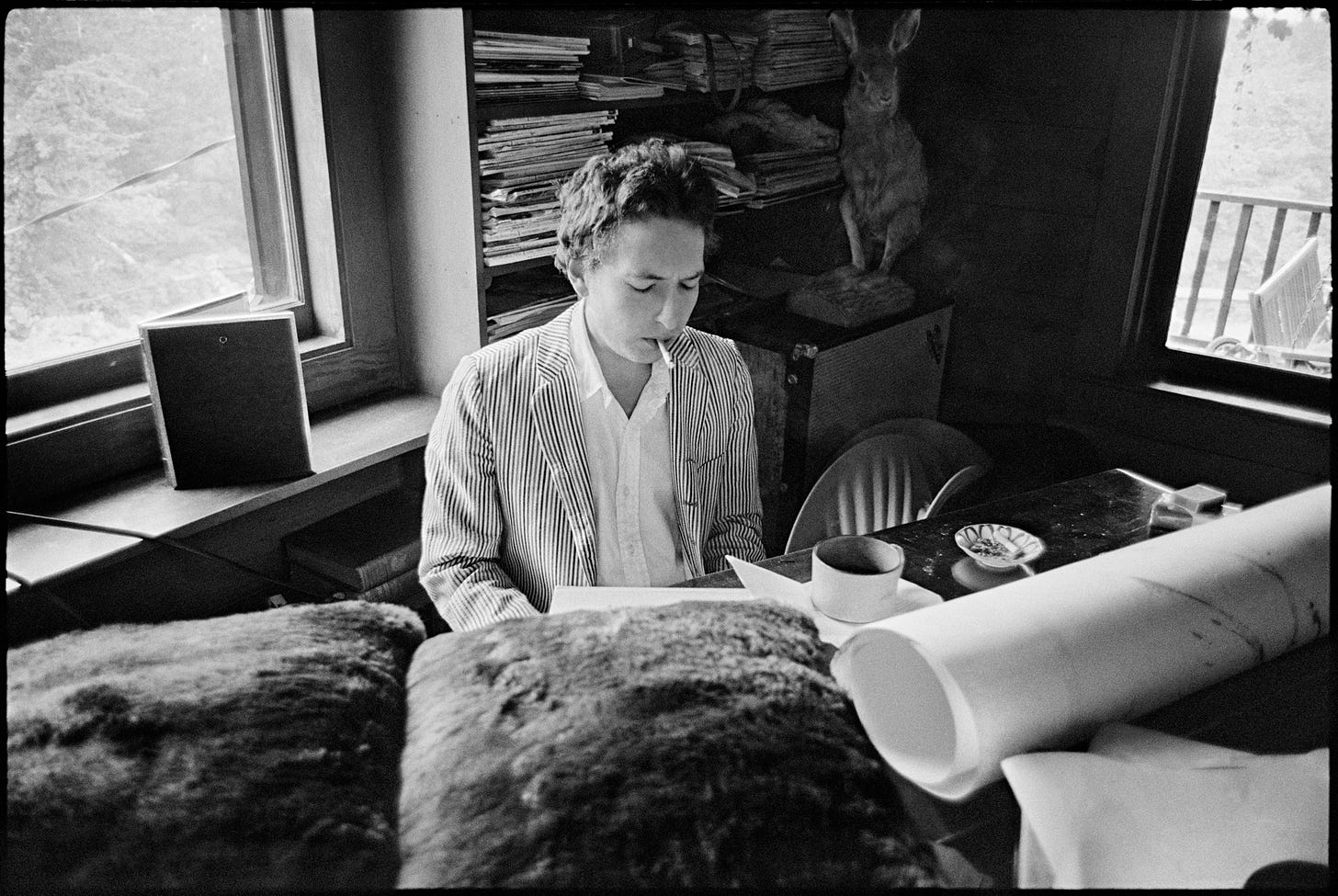

After months of enduring hostility and heckling from fans who despised his new electric music and band, and after steadily increasing his drug use to dangerous levels, Dylan crashed, quite literally. He wrecked his motorcycle on July 29, 1966, which just happened to be the one-year anniversary of recording “Positively 4th Street,” his defiant rebuttal to folk purists who turned against him. He used his convalescence to get off the road and off hard drugs. He found new sources of joy and inspiration, first in his young family, and soon in his musical collaborations with Robbie Robertson, Garth Hudson, Richard Manuel, and Rick Danko (and later Levon Helm). Dylan first invited the lads over to jam at his place, setting up their equipment in the Red Room of his Woodstock home. When his bustling domestic life proved too distracting, they switched locales to the basement/garage at the Band’s nearby bachelor pad in West Saugerties, nicknamed Big Pink.

For the next several months, from roughly March or April through at least November 1967, the guys regularly got together to play, at first entertaining themselves with a wide array of covers. Eventually their focus shifted to producing demos of the amazing new songs Dylan had just composed, either back home, or on the typewriter upstairs, or improvised on the spot. The results are versatile, sensitive, profound, hilarious, miraculous. The Basement Tapes are the finest document of creative freedom that I’ve ever heard. I bet many of you feel the same.

Paradoxically, some of the best expressions of this creative freedom comes in the form of prison songs. For the present post, I want to examine three in depth: Brendan Behan’s “The Auld Triangle,” Johnny Cash’s “Folsom Prison Blues,” and Dylan’s own “I Shall Be Released.” I’m not the first to detect links between them. I agree with Clinton Heylin that the first two songs helped inspire the third. As he puts it in Revolution in the Air:

Prisons of the body and the mind seem to have preyed on Dylan’s mind throughout his time spent with the boys on retainer. Among the songs recorded at early basement sessions were covers of “Folsom Prison Blues” and “The Banks of the Royal Canal” (the latter is particularly affecting), both songs written—metaphorically—from inside prison walls. Dylan then takes a leaf from Johnny Cash and Brendan Behan (brother of Dominic), authors of those earlier songs, by writing his own prison song, “I Shall Be Released.” (348)

Heylin recognizes the source material but then turns his attention to other matters. I want to linger longer over these songs, filling in more context and exploring further connections between Behan, Cash, and Dylan’s respective prison songs.

In an interview with Sid Griffin for his book Million Dollar Bash, Garth Hudson said something really insightful that I’ve used as my guide. The multi-instrumentalist and de facto sound engineer for the Basement Tapes marveled at Dylan’s genius for “‘singing one song to arrive at another’” (qtd. Griffin 110). That’s it! In what follows, I want to consider how Dylan sang “The Auld Triangle” and “Folsom Prison Blues” to arrive at “I Shall Be Released.”

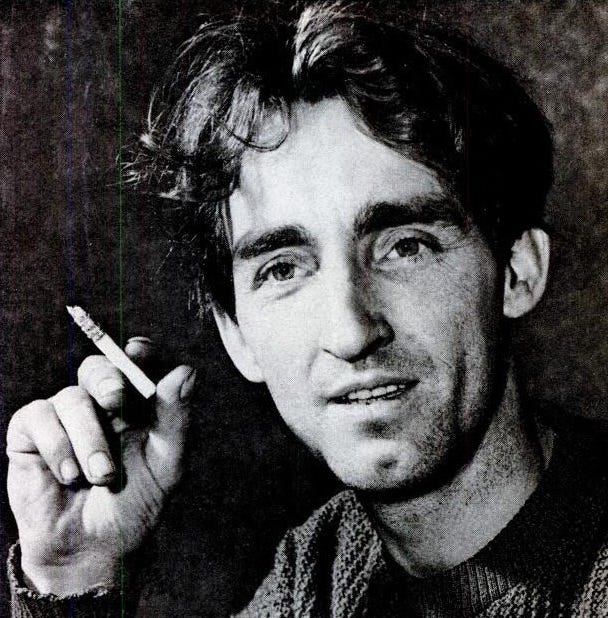

The Behan Brothers & The Clancy Brothers

If you’re a Dylan fan, the first association you probably have between him and a Behan is actually with Brendan’s younger brother Dominic. In 1963, Dominic publicly accused Dylan of ripping off his song “The Patriot Game” in “With God on Our Side.” There’s no denying that the two songs share the same melody and opening lyrical structure; Dylan admits as much in his introduction to the song at the 1963 Newport Folk Festival. [Dominic conveniently neglected to mention that he lifted the tune for “The Patriot Game” from the folk song “One Morning in May.”]

The elder Behan got in some shots on his brother’s behalf the following year in his travelogue Brendan Behan’s New York. In his chapter on Greenwich Village, he offers this profile of the folk scene: “If you are interested in folk-singing, Washington Square on a Sunday must be unique. Folk-singers I personally detest. I would shoot every one of them, because I am a singer myself—at least I was until my larynx gave in to too many cigarettes. And they always tell a pack of lies” (115). Oh, yeah? Any particular lying folk-singers you have in mind?

He doesn’t name names, but he surely has Dylan in mind with this pointed barb: “I will admit however, that some of these pseudo-folk-singers seem to be excellent composers, but most of them will never admit that they haven’t written the song themselves” (115). Message received, Brothers Behan! When Dylan complained in Dont Look Back (1965), “I don’t wanna hear nobody like Dominic Behan, man!,” the feeling was surely mutual. By that point, however, he would be taking no more guff from Brendan, who drank himself into an early grave in March 1964 at the age of 41.

Lot of water under the bridge, lot of other stuff, too. But let’s not overlook other compelling evidence that Dylan was a big admirer of Brendan Behan’s work, particularly the song “The Auld Triangle”—which, ahem, was actually written by Dick Shannon, though it’s routinely attributed to Behan.

Dylan emphasized the importance of “The Auld Triangle” in his 1984 interview with Bono of U2. It came up as part of Dylan’s praise for the Irish musical tradition. Speaking with Bono backstage before the huge Slane Castle concert, he declared, “Irish music has always been a great part of my life because I used to hang out with the Clancy Brothers. They influenced me tremendously” (805). He fondly remembered that period of 1961-63, playing and hanging with the Clancys. “One of the things I recall is how great they all were—I mean there is no question but that they were great. But Liam Clancy was always my favorite singer, as a ballad singer. I just never heard anyone as good, and that includes Barbara Streisand and Pearl Bailey. He’s just a phenomenal ballad singer” (805).

Liam Clancy may well be the one who introduced Dylan to “The Auld Triangle.” It was certainly a regular part of their sets. He sang plenty of other rebel ballads about prison, too, like “Kevin Barry,” set in the same Mountjoy Prison as “The Auld Triangle.” “Kevin Barry” is included on their 1959 album Irish Songs of Drinking and Rebellion, as is “The Parting Glass” (which provided the melody for Dylan’s “Restless Farewell”) and “Roisin’ the Bow” (which Dylan and the Band covered in the Basement Tapes).

And then there’s “The Auld Triangle.” Dylan asks Bono, “You heard the songs—Brendan Behan’s songs? ‘Royal Canal,’ you know ‘Royal Canal’?” (809). He starts performing it on the spot, then adds, “I used to sing it all the time. […] Every night” (810).

Dylan the sponge may have absorbed the song secondhand from the Clancys, but it’s entirely plausible that he picked the song up firsthand from The Quare Fellow, Brendan Behan’s play which featured “The Auld Triangle” prominently. Remember that he was dating Suze Rotolo at the time, and she was very active in the Village theater scene. In fact, Rotolo recounts a direct run-in between Dylan and Behan, an encounter that she orchestrated.

In her memoir A Freewheelin’ Time: A Memoir of Greenwich Village in the Sixties, she recalls working in the basement theater at One Sheridan Square in 1962 during a long run of Behan’s play The Hostage. I’ll let her take the story from here:

I was standing in the back of the theater watching the play one evening when Behan himself wandered in. If Behan happened to be in the city where one of his plays was being put on, he had a habit of showing up and joining the performance. It made for interesting theater at times, especially when he engaged the actors in some improvisation. But he was a bit of a drinker and could completely disrupt the play if he was in his cups. I ran to the phone and called Bobby at home to tell him Brendan Behan was at the theater and he should come by. (129)

Let me interrupt to observe that Suze must have known Bobby was a big fan, otherwise why would she think he’d care that a drunken playwright had just staggered into her theater? But she did, and he did, and their 4th Street apartment was just around the corner, so he dashed over.

Behan was very drunk. Listing left and right, he wandered onto the stage and, waving his hands about, made an incoherent speech to the actors. Then he abruptly teetered off the stage and out the door. He staggered up the stairs of the theater with Bob right behind him. Bob followed him to the White Horse, hoping for a conversation, but Behan was in no shape for anything remotely resembling talk and eventually passed out. (129)

Just your typical evening at the White Horse Tavern: Bob Dylan propping up an incoherent Brendan Behan, while Tommy Makem and the Clancy Brothers serenade the patron saint of boozers with his greatest hits. If only Pennebaker had brought his camera that night!

The Quare Fellow

If Dylan was such a groupie that he pursued the playwright for several blocks and followed him into a pub, then it’s fair to assume that he was familiar with the man’s most famous play The Quare Fellow. The play begins and ends with verses from “The Auld Triangle,” and the song is interjected at key junctures throughout the action. In the original 1954 production, Behan himself played the prisoner singing “The Auld Triangle.”

The Quare Fellow is set in Mountjoy Prison in Dublin. Behan was from an Irish Republican family active in militant activities. In 1942 when he was still a teenager, he was sentenced to 14 years for attempted murder of two police officers. He was imprisoned at Mountjoy until 1946, when he was released as part of a general amnesty for IRA political prisoners.

“Brendan Behan first saw his father through prison-bars,” writes Declan Kiberd in Inventing Ireland. Not long after his birth in 1923, the infant was taken to the jail in which Stephen Behan, even then a veteran republican, was held as a consequence of the Civil War. Two decades later, the son himself would be in prison as a republican prisoner” (513). Like father, like son, right? Well, not exactly.

Behan’s attitude toward prison contrasts with that of many writers who became radicalized in jail. “The effect of prison on most of the republicans,” observes Kiberd, “was to redouble their political fervor; the effect on Behan, however, was to leave him with an abiding distrust of all commitments” (513). That distrust of commitments and institutions is epitomized in his stultifying portrait of prison life in The Quare Fellow. Behan uses the play to protest capital punishment and to expose the absurdity, capriciousness, and cruelty of the penal system. But most of all, the play decries “the corrupting effects on the human spirit of prison life” (Kiberd 513). The essence of that critique is distilled down into “The Auld Triangle.”

There’s an interesting bit of stage business in the third act. As a senior and junior warder make their evening rounds, they hear incessant tapping. The older warder explains that this is a form of communication between the prisoners, like a jailhouse Morse code. It’s an odd effect from the audience’s perspective. We see the action and hear the words on stage, but we’re also made aware of another stream of information being expressed which we can’t translate because we don’t speak the language.

I have a similar reaction when listening to the best of the Basement Tapes. Dylan and the Band are so in sync with each other that it’s like they’re communicating telepathically, carrying on a musical conversation in code. Listening to the Basement Tapes feels like eavesdropping on private messages, something not meant to be overheard, an enigmatic and illicit secret.

That must be what Robbie Robertson had in mind in his conversation with Greil Marcus, comparing the Basement Tapes to a conspiracy. The critic conceptualized the basement as a kind of laboratory, but when he ran the idea past the guitarist, he disagreed: “No. A conspiracy. It was like the Watergate tapes. A lot of stuff, Bob would say, ‘We should destroy this’” (xxii). Luckily, they didn’t destroy “The Auld Triangle,” one of the most gorgeous songs in the entire Basement Tapes.

“The Auld Triangle”

This performance is utterly captivating. It took place in the Red Room of Dylan’s home in Woodstock in the spring of 1967. But it seems irrelevant to pin the song down to a time and place when it effectively transports the listener to an astral plane all its own.

Garth Hudson deserves a lot of the credit for navigating this trip through the cosmos. He must have been playing with both hands and feet to get this spellbinding sound from his Clavinet and organ. But there’s nothing ostentatious about his performance. His touch is delicate, not the iron jangling of a jailhouse triangle, but the soft tinkling of a light breeze through wind chimes. The other players are all restrained, too. Dylan keeps rhythm with his 12-string acoustic guitar, Danko’s bass is barely perceptible, and Robertson holds back and picks his spots subtly but effectively on electric guitar.

The calendar says that we’re less than a year removed from the raucous 1966 tour, but musically we’re light years beyond “Play it fucking loud!” Dylan led that cavalry charge at the Manchester Free Trade Hall like he was storming the Bastille, with his blaring, defiant, howling voice. Now he leads a funeral procession through a vale of tears.

The sound is celestial, but the lyrics describe an earthbound condition. “The Auld Triangle” is sung by a prisoner incarcerated at Dublin’s Mountjoy Prison. Accompanied by lovely harmonizing from Danko on the refrain, Dylan sings,

A hungry feelin’

Came o’er me stealin’

As the mice were squealin’

In my prison cell

And the old triangle

Goin’ jingle jangle

All alooong

The baaaanks

Of the royaaaal

Canal

If you love Irish music like I do, you’ve heard this song a thousand times. But pause to think about the economy of language and imagery packed into this first verse. Start with the hunger, an extremely loaded term in the Irish context. The hunger inevitably calls to mind the horrors of “The Great Hunger” of the 1840s, and the mishandling of the crisis by the British government, turning an agricultural disaster of potato blight into a nationwide famine and humanitarian tragedy. The hunger also has specific connotations at Mountjoy Prison, site of the famous 1920 Hunger Strike held by Irish republicans to protest the refusal of authorities to recognize their status as political prisoners.

Within the context of the song, the hungry feeling that comes stealing over the singer seems more like a spiritual hunger, the malnourishment of his soul in this doleful place—the predominant theme of The Quare Fellow. The prisoner longs to be free, one way or another. The emblem of his oppression is the old triangle, which goads his every action in an environment of total institutional control and zero self-autonomy.

The singer is tortured by the thought that the jingle-jangle made by the triangle enjoys a greater freedom than he does. The sound drifts above the walls and flows freely through Dublin along the banks of the nearby Royal Canal. Place this song alongside “Mr. Tambourine Man” and the influence seems obvious: “In the jingle jangle morning I’ll come followin’ you.” The prisoner in “The Auld Triangle” desperately wishes he could follow the sound, but he’s incarcerated and there is no place he’s going to.

On a fine spring evenin’

The lag lay dreamin’

The seagulls beamin’

High aboooove the waaaall

They can hold your body in captivity, but they can’t prevent your mind from dreaming of a better life. Still, when the prisoner looks upon nature, he sees glimpses of freedom that he no longer enjoys himself. The gulls soar high above the wall, “free as a bird.” Incidentally, I suspect that one of Dylan’s attractions to writing “Walls of Red Wing” was the cruel irony of facility’s name—Red Wing—implying the freedom of flight which is utterly denied the inmates behind the walls.

The final verse Dylan sings is especially poignant:

Oh, the day was dyin’

And the lag was sighin’

As I lay cryin’

In my prison cell

And that old triangle

Went jingle jangle

All aloooong the baaaanks

Of the Royaaaal

Canaaaal

In The Old, Weird America, Greil Marcus takes the measure of this dejected performance: “There seems to be no bottom to Dylan’s tone here, and no desire in it either. ‘Jingle jangle,’ goes the triangle that rouses the prisoners each morning (Hudson gets the sound out of his clavinette)—‘The Old Triangle,’ as the song is sometimes called, as if the singer admits the hated instrument was here before he was, that it will be here when he’s gone” (259).

You might say that the song isn’t merely a dirge but also a self-eulogy. Or as Marcus puts it, hammering the final nail in the coffin, “this is ‘I Shall Be Released’ without any hope for freedom” (259). That’s a perceptive observation, but it should also serve to remind us that Dylan did eventually move beyond the despair of “The Auld Triangle,” working through Behan’s dark lamentation to arrive at his own prison song with more glimmers of hope.

Cash & Dylan

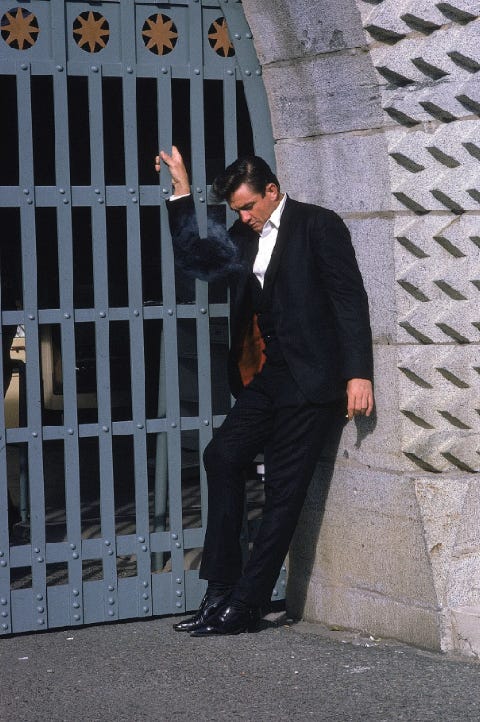

In one of the other memorable papers from the Denmark symposium, my pal Court Carney shared his thoughts on “Wanted Men: Bob Dylan and the Vulnerability of Brotherhood.” Court considered three broad types of male relationships that have sustained Dylan personally and professionally: mentors, gunslingers, and brothers. You could make a case for putting Johnny Cash in all three categories: he was that important to Dylan.

A whole book could (and should) be written on what these two revolutionary artists meant to each other. I’m just going to briefly sketch the outline of Cash’s long shadow over the Basement Tapes.

Cash was nine years older than Dylan, and he had already cemented his place in music history with his Sun recordings in the mid-fifties, several years before Dylan started making a name for himself. The young singer-songwriter made a huge impression on the veteran with The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan (1963). Cash so admired the depth, maturity, and range of songs that he took the initiative to write a “fan letter.” Dylan immediately reciprocated, saying that he had been a big fan of Cash’s songs ever since “I Walk the Line.” The two memorably met at the 1964 Newport Folk Festival, where Cash covered “Don’t Think Twice, It’s Alright.” In his autobiography Cash recalls, “I do remember June and me and Bob and Joan Baez in my hotel room, so happy to meet each other that we were jumping on the bed like little kids” (266).

Their musical collaborations were just beginning. Cash included three Dylan covers on his 1965 album Orange Blossom Special: “It Ain’t Me, Babe,” “Don’t Think Twice, It’s Alright,” and “Mama, You Been on My Mind.” Their mutual record producer Bob Johnston got them together for a recording session in February 1969, and Dylan released their duet of “Girl from the North Country” on Nashville Skyline later that spring. In May 1969, Dylan appeared as a guest on the very first episode of The Johnny Cash Show where they reprised the duet.

That same year, Cash sang “Wanted Man” at the San Quentin Penitentiary, a song Dylan wrote specifically for him. You can hear it on the live concert album released that summer. You can also hear the two men singing it together on Travelin’ Thru (The Bootleg Series, Vol. 15), along with several other Dylan/Cash collaborations.

Cash looms large in the Basement Tapes of 1967. By my count, there is no artist Dylan and the Band covered more than Cash, playing “Belshazzar,” “Big River,” “Folsom Prison Blues,” “Still in Town,” and “Hills of Mexico.” For our purposes, the most significant of these performances is one of Cash’s earliest compositions and one of the most famous prison songs ever written.

“Folsom Prison Blues”

Cash was inspired to write “Folsom Prison Blues” during his stint in the Air Force. In the early fifties he was stationed in Landesberg, near Munich, in West Germany. Biographer Robert Hilburn shares this interesting footnote: “The air base was a former outpost for the Luftwaffe, the German Air Force, and it was notorious in Germany because Adolf Hitler wrote Mein Kampf while imprisoned there in 1924” (40).

The prison that inspired the song, however, was the one in the title. Sort of. Actually, the initial idea came when Cash saw the film Inside the Walls of Folsom Prison. The melody and some of the lyrics were adapted from the song “Crescent City Blues,” written by Gordon Jenkins and sung by his wife Beverly Mahr. Listen to the song and the debts are obvious.

But Cash makes “Folsom Prison Blues” distinctly his own, particularly with the striking line, “I shot a man in Reno just to watch him die.” Hilburn observes: “He wanted to write not just about someone who was lonely for his girl, but about someone so empty inside that he felt cut off from both his family and his faith—someone so numb spiritually that he could take pleasure in killing a man just to watch him die” (80).

Cash sometimes played concerts in prisons. For instance, he put on a show at San Quentin in 1960 attended by convict Merle Haggard. The Okie from Muskogee was so inspired by this performance that he vowed to pursue his own singing career after he got out of the can. Cash’s most famous prison concert was at Folsom. On January 13, 1968, he walked out on stage, began with his trademark introduction [“Hello, I’m Johnny Cash”], and launched into a rambunctious rendition of “Folsom Prison Blues,” revved up by the enthusiastic response of the inmates.

A few months earlier, on the other side of the country, Dylan and his garage band put their own spin on Cash’s classic. Their approach contrasts with the iconic Sun record by Cash and the Tennessee Two.

In that original version, Marshall Grant’s bass and Luther Perkins’s electric guitar work in tandem to create the steady, driving, freight train sound of the song. And then of course there’s Cash’s booming voice, bold but beaten down by the singer’s captivity in prison. The way he descends the musical scale at the end of each verse, it sounds like he’s walking down the steps to solitary confinement in the hole of Folsom Prison.

When Bobby’s in the basement mixin’ up the Johnny, he concocts a distinctly different “Folsom Prison Blues.” Dylan gets the train a-rollin’ with his acoustic guitar. As the music builds momentum, Danko’s bass and Robertson’s electric guitar emerge, generating the song’s chugga-chugga, clickety-clack rhythm. Hudson’s bopping organ speeds down the tracks like the Chattanooga Choo-Choo.

You’ll never out-Cash the Man in Black, so Dylan doesn’t even try. His vocals sound nothing like Cash’s rich baritone, and nothing like the bourbon-and-molasses croon he would adopt for Nashville Skyline. Where Cash goes low, Dylan goes high, boosted by Danko’s wildcat yowl on harmonies. I love the way Marcus describes it: “Taken fast, Dylan’s fuck-it-all singing for the verses rising high on the choruses with the group’s help, as if for a second he could actually make it over the wall” (243).

Like the contrasting vocals of Cash and Dylan, the narrator of the song is a study in dichotomy. Before landing in Folsom, he was fierce, unbridled, audacious, and ruthless. Not now. His once indomitable spirit has been crushed by prison life. He’s depressed: “I ain’t seen the sunshine since I don’t know when.” He’s emotionally fragile: “When I hear that whistle blowin’ I hang my head and cry.”

The train whistle has much the same effect on the prisoner as the triangle has on the lag in Behan’s song. The Dublin inmate hears the jingle-jangle and imagines the sound going where he wishes he could go: over the wall, down the canal, flowing into the city, unencumbered, free. The Folsom inmate hears a sound that originates outside the prison wall, and it prompts him to imagine the freedom enjoyed by others on the train outside:

I bet there’s rich folks eatin’ in some fancy dining car

I bet they’re drinkin’ coffee and smokin’ big cigars

But I’m stuck in Folsom prison, I know I can’t be free

But those people keep a-movin’ and that’s what tortures me

Movement = Freedom = Life. Stasis = Captivity = Death. The prisoner’s highest aspiration is to get moving again:

If they freed me from this prison, if that railroad train was mine

You bet I’ll move it on down a little further down the line

Far from Folsom Prison, that’s where I want to stay

Well, I’ll let that lonesome whistle blow my blues away

Cash once had this to say about the enduring appeal of prison songs:

I think prison songs are popular because most of us are living in one little kind of prison or another, and whether we know it or not the words of a song about someone who is actually in a prison speak for a lot of us who might appear not to be, but really are. (qtd. Horstman 291)

Did Dylan feel like a prisoner in Woodstock? This gets me back to my initial impetus for this piece, prompted by Erin Callahan’s prison/sanctuary framework for the Basement Tapes.

We can say this much for sure: Dylan was vibing hard with prison songs in 1967. Both “The Auld Triangle” and “Folsom Prison Blues” equate freedom with movement and captivity with stasis. While Dylan was freer to move than actual jailhouse inmates, he still felt increasingly stuck in Woodstock. This is not idle speculation or outrageous presumption—he has said so himself.

In the “New Morning” chapter of Chronicles, Dylan recalls, “I found myself stuck in Woodstock, vulnerable and with a family to protect” (115). Hounded by intrusive fans, the Dylan household was under siege: “Tensions mounted almost immediately and peace was hard to come by. At one time the place had been a quiet refuge, but now, no more” (116). His sanctuary had turned into a prison: “Woodstock had turned into a nightmare, a place of chaos” (118).

Interestingly, as disaster encircled his family and he sought some way to escape by reinventing himself, Dylan turned to Cash as one of the few people who could relate to his predicament and provide some guidance. In the “New Morning” chapter, he writes,

I turned on the radio. Johnny Cash was singing “Boy Named Sue.” Once upon a time Johnny had shot a man in Reno just to watch him die. Now he was saying that he was stuck with a girl’s name that his father had given him. Johnny was trying to change his image, too. Aside from that, I didn’t see much similarity between my situation and anybody else’s—felt pretty isolated with just myself and my small but growing family facing a fantastic world of sorcery. (127)

At the time he wrote Chronicles, Dylan characterized his conflict as Us vs. Them, with Us representing his family inside the home, and Them representing the threatening and rapacious forces outside the home. Later, however, he hinted that family obligations were a major source of his pain, insofar as Home proved adversarial to Art.

In his 2015 interview for AARP Magazine, Robert Love elicited some revealing reflections from Dylan on the Woodstock years. The interviewer asked, “In a period around 1966, you went into seclusion for more than a year, and there was much speculation about your motives. But it was to protect your family, wasn’t it?” Dylan answered unequivocally: “Totally. That’s right.”

Love continued: “And I think that people didn’t quite want to understand that, because your idiosyncratic view of the world as an artist made them think you were an idiosyncratic person, but in reality you were a typical dad who was just trying to protect his kids.” Again, Dylan didn’t mince words: “Totally. I gave up my art to do that.”

What a direct, piercing statement: “I gave up my art to do that.” Dylan never put it that bluntly in Chronicles. Love is a good interviewer. He asked the right follow-up: “And was that painful?” Listen to Dylan’s honest answer: “Totally frustrating and painful, of course, because that intuitive gift—which for me went musically—had carried me so far. I did do that, yeah, and it hurt to have to do it. But I didn’t have a choice.”

Dylan loved his wife and kids and made sacrifices for their wellbeing. He doesn’t regret it, and he’s not asking for special recognition: millions of people sacrifice for their families every day. But he’s acknowledging that it wasn’t easy—in fact it was really fucking hard—and not just because of trespassers on the roof and hack journalists in the press. It was painful because he felt cut off from what he was put on this planet to do. Confined. Isolated. Stripped of choices. Stuck.

To be fair, Woodstock was a gilded cage of his own creation. A real-life inmate at Mountjoy or Folsom would probably reject the analogy. That said, I’m arguing that the impulses that drew Dylan away from the Living Room to the Red Room, and then away from Home to the Basement, are the same impulses that drew him to prison songs in 1967. It gave him access to relate on some deep, intuitive level to the prisoners’ experiences in “The Auld Triangle” and “Folsom Prison Blues.” And these songs in turn opened the creative doors Dylan needed to arrive at his greatest original contribution to the genre.

“I Shall Be Released”

Other Voices, Other Cells

“Coming events cast their shadows before,” thinks Leopold Bloom in James Joyce’s Ulysses (210). I feel the same way when listening to Dylan. Sometimes you’ll be certain that an event or experience must have influenced a song or album, only to discover that it actually happened after the song was already written (cf. the brush with mortality and Time Out of Mind). Chronology seems misleading in these cases—surely our gut instinct isn’t wrong, so the calendar must be.

For instance, it feels like “I Shall Be Released” must be, should be, has to be a response to Woody Guthrie’s death. I shall be released from this body that has betrayed me, and I shall be released from this asylum they keep me trapped in. Yes, I know the song was recorded by September and Woody didn’t die until October, but there goes that lying calendar again. As Blanche Du Bois insists, “I don’t tell the truth. I tell what ought to be the truth. And if that is sinful, then let me be damned for it!” (1033).

While I’m floating far-fetched theories that don’t meet scholarly standards of proof but nevertheless feel intuitively right, let me confess that I really want “I Shall Be Released” to be Dylan channeling the Rosenbergs in prison before their executions. Of course, he did eventually write a song about them, “Julius and Ethel,” an outtake from the Infidel sessions. Was he already imagining his way into their prison experience as early as 1967? I have no evidence to back up this hunch. But I’ll put it out there anyway in case Shadow Chasing readers find the notion as intriguing as I do.

Ultimately, Dylan didn’t have to look outside himself to Woody or Julius or Ethel to imagine his way into a prisoner’s experience. He could sing his way into Mountjoy or Folsom, transforming the Red Room or the Basement into a virtual cell. From there, he was eventually able to see his own reflection inside his own prison song.

“I Shall Be Released” is the most-covered song from the Basement Tapes. And yet, puzzlingly, it was omitted from the official double album The Basement Tapes put out by Columbia in 1975. According to Sid Griffin, “It is alleged that Robertson did not put this prisoner’s lament or ‘The Mighty Quinn’ on the official ’75 release as he and Dylan thought the public already knew them well enough from their cover versions” (191). Maybe. But given Dylan’s perverse tendency to leave some of his best songs off albums, perhaps he couldn’t resist the delicious irony of not releasing a song titled “I Shall Be Released.”

What makes this song so special? Let’s start with the sound. Dylan is back on 12-string acoustic guitar, the same magic wand he waved to cast a spell in “The Auld Triangle.” Robbie Robertson’s electric guitar is the lantern leading his comrades through the darkness. Dylan famously described Robertson as a “the only mathematical guitar genius I’ve ever run into who does not offend my intestinal nervousness with his rearguard sound.”

Asked what he thought Dylan meant by that cryptic remark, Robertson gave this answer to MOJO’s Michael Simmons in 2017: “It’s having a structure that’s improvised and at the same time you have a sense of dynamics—when to rise, when to fall, when to shimmer, when to growl.” That’s as good a description as anything I could come up with to describe his guitarwork on “I Shall Be Released.” Hudson’s ambient organ is the sea the other players float in, and Danko helps mark the pace with his bass in yet another drummerless basement track.

The voices—my God, the voices! They’re heavenly. Dylan’s singing ranges from melancholy brooding to heart-wrenching prayer. He utterly loses himself in the role of a prisoner at the end of his rope—figuratively if not literally. If Robertson is a special kind of genius on guitar, then the same can be said for Danko’s harmonies. And then there’s Richard Manuel. I’m not always a fan of falsetto singing, but Manuel uses it to perfection here. Dylan establishes the foundation, Manuel soars above him, and Danko provides a sonic tether connecting the two. The Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost.

First Verse & Chorus

Now let’s shift our attention from the performative how to the lyrical what. Note that I’m transcribing the words I hear sung on The Basement Tapes Complete, which sometimes depart from the official lyrics on Dylan’s website. The song begins,

They say everything can be replaced

Yet every distance is not near

So I remember every face

Of every man who put me here

Dissatisfaction with his position and his place? You bet. Resentment toward those to blame for his incarceration? Yes indeed. But the chief emphasis in this first verse is on loss. More specifically, the singer broods on what has been taken from him and who is responsible for taking it. There is something fundamentally missing from his life; a crucial part of him is gone, and he hasn’t been able to adequately replace it.

How does it feel? Isn’t that always the question driving Dylan’s greatest songs and performances? He feels his way into the emotional heart of an experience and gives voice to it. Given Dylan’s comments above in the Love interview, he could relate personally to the prisoner’s lament in “I Shall Be Released.” One too many mornings in Woodstock, and a thousand miles behind on the road. Stasis vs. Movement.

The chorus is so beautiful:

I see my light come shining

From the west unto the east

Any day now

Any day now

I shall be released

Think about what he’s describing here. The light shining from west to east indicates sunset: the end of the day and perhaps the end of his life. Under these conditions, you couldn’t fault him for feeling depressed and laying emphasis upon the coming night (cf. “It’s not dark yet, but it’s getting there”). But that’s not what he does here. The prisoner doesn’t “rage against the dying of the light,” as that other Dylan (Thomas) advised. Quite the contrary, he longs for release, and seems perfectly willing to embrace death as the agent of his deliverance. He doesn’t see this as giving into darkness or despair. Look at his positive word choices: “light,” “shining,” “day” (twice), “released.”

It’s impossible to separate the what from the how because the harmonies on the chorus are so divine. Let me test another wild hypothesis on you: Dylan as Body and Manuel as Soul. I’m not suggesting that the singers are so calculated or literal-minded as to consciously design the harmonies that way. But I think one reason their voices work so well together is because it sounds like we’re hearing different sides of the protagonist crying out. There’s the earthbound body stuck in prison, but then there’s the immortal soul yearning to break free and fly away.

In his entry on “I Shall Be Released,” Heylin highlights this perfect quote from Dylan’s 1978 interview with Phillip Fleishman: “‘The whole world is a prison. Life is a prison, we’re all inside the body’” (qtd. Heylin 348). Yes! That’s exactly what I’m talking about.

This cosmological view is consistent with Gnostic beliefs that this world was created by a mad Demiurge to trap the divine light within us and keep it from returning to its origin in the Pleroma. But you don’t have to be a theologian or kabbalist to get it. You can simply listen to “I Shall Be Released.”

There is something higher and brighter inside the prisoner, something which responds to the sunset as a kindred spirit, something that yearns to be released from this prison/world/body and be free. Might as well call it a soul. The soul of the song is Richard Manuel. His voice is the spirit breaking loose, escaping, and going home. That’s what I hear anyway, and if that is sinful then let me be damned for it.

Second & Third Verses

Back down here on earth, Dylan delivers another charged second verse:

They said every man needs protection

They say every many must fall

Yet I swear I see my reflection

Some place so high above this wall

I’ve never spent time in prison, but the impression I get from prison songs is that nothing is more imposing or impenetrable than the prison wall. It’s a literal barrier, of course, but it rises to symbolic heights as the emblem of captivity. Out there, above and beyond the wall, is freedom; inside the wall is subjugation. “The Auld Triangle” treats the wall in this manner, and so does Dylan’s early prison song “Walls of Red Wing.” Another prime example is Johnny Cash’s song “The Wall,” wedged in between two Dylan covers on Orange Blossom Special.

I think Dylan has other walls in mind, too, on “I Shall Be Released.” One of his Cash covers for the Basement Tapes was “Belshazzar,” based upon the Book of Daniel. Walls surround that song from the start:

Well, the Bible tells us about a man

Who ruled Babylon and all its land

’Round the city he built a wall

Declared that Babylon would never fall

But Belshazzar’s confidence was shaken during a feast when mysterious writing suddenly appeared in blood on the banquet hall’s wall. He summoned the prophet Daniel to translate the writing on the wall. It was a message from God, which also serves as the chorus of the song:

You are weighed in the balance and found wanting

Your kingdom is divided, it cannot stand

You are weighed in the balance and found wanting

Your houses are built upon the sand

Daniel’s vision prefigures the punishment of the wicked and corrupt, the destruction of the prison walls that held the Jewish people captive, and God’s deliverance of his chosen people once again from slavery into freedom.

The writing on Belshazzar’s wall might just as well be written on the prison walls of “I Shall Be Released.” But that’s not the only scriptural allusion I detect in this verse. Take a listen to the first take of “I Shall Be Released.” It’s still a rough cut. The band is still learning their parts, and Dylan hasn’t quite nailed down the lyrics yet.

We know that Dylan was reading the Bible a lot during this period. There are scriptural allusions on his prison wall which take us back inside the gates of Eden. What I hear him sing in this first take of the second verse is: “They say every man needs protection / They say every belly must crawl.” If my ears don’t deceive me, this must be an allusion to God’s punishment of the serpent after tempting Eve to eat the forbidden fruit. “And the Lord God said unto the serpent, Because thou hast done this, thou art cursed above all cattle, and above every beast of the field; upon thy belly shalt thou go, and dust shalt thou eat all of the days of thy life” (Genesis 3:14).

In the better known second take of the song, Dylan retains the rhyme, but replaces “crawl” with “fall”: “They say every man must fall.” Of course, now that we’ve got our Bibles open, this sounds like an allusion to the same catastrophe in Eden, shifting the focus to mankind’s fall from grace. Yonder comes sin. Humanity has been weighed in the balance and found wanting. Now it’s goodbye Garden of Eden, hello world as prison.

The wall imagery in “I Shall Be Released” is being used in an unconventional manner, however, atypical of the prison song genre. The prisoners in “The Auld Triangle” and “Folsom Prison Blues” have visions of the people they’ll see and the things they’ll do if they ever get out of the joint and back to walking the streets or riding the trains. Not Dylan’s prisoner. He sees his image reflected in the heavens, and that’s ultimately where he longs to be. When he looks at the prison wall, he regards it as his leaping-off point, out of this prison-world and cage of a body, and into the mystic.

Before that can happen, the prisoner has to overcome other walls, inner walls, which he has erected himself. The prerequisite to release is first achieving the peace of mind that comes with atonement, forgiveness, and acceptance.

To appreciate how the singer arrives there, let’s consider the third and final verse:

Now yonder standin’ me in this lonely crowd

A man who swears he’s not to blame

All day long I hear his voice shouting so loud

Crying out that he was framed

I really like Paul Williams’s interpretation of “I Shall Be Released.” He hears each of the three verses as stages in the prisoner’s evolving attitude toward his crime and punishment:

The first verse is about desire for revenge, the second about faith, and the third about acceptance (implicit, by contrast with the man “next to me” who “swears he’s not to blame”), and each verse is followed by the chorus, which is about desire for, faith in, and finally acceptance of, deliverance. This is not a song we can imagine showing up on Blonde on Blonde or Highway 61 Revisited. It’s the humblest performance of all the Basements, and the least ambivalent; Dylan could be sly here too if he wished, but he chooses not to be; he has something he wants to say. (234)

Deliverance is precisely the right word for what Dylan is trying to say lyrically with this song. Deliverance is a term weighted with scriptural and historical meaning, signifying the emancipation of the Jewish people, first from Egypt and then from Babylon. This motif of deliverance was later adopted by African Americans striving for freedom from slavery, persecution, and inequality. Just listen to Nina Simone’s cover of “I Shall Be Released,” and you’ll hear all the history lesson you need. Finally, deliverance implies a deliverer: a higher power that leads the way toward a freedom that cannot be achieved alone.

Dylan wasn’t a Christian yet in 1967, but he was starting to incorporate religious texts, images, themes, and messages, with sophistication and urgency, into the Basement Tapes and the contemporaneous songs for John Wesley Harding. “I Shall Be Released” is an ideal example.

Let me build upon Williams’s interpretation. In the first verse, the singer remembered every face of every man who put him in jail. The mood there is one of recrimination and revenge. He’s consumed with bitterness. This makes me think of John Prine’s great song about the wages of bitterness, “Bruised Orange (Chain of Sorrow).”

You can gaze out the window

Get mad and get madder

Throw your hands in the air

Say “What does it matter?”

But it don’t do no good

You get angry

So help me I know

For a heart stained with anger

Grows weak and grows bitter

You’ll become your own prisoner

As you watch yourself sit there

Wrapped up in a trap

Of your very own chain of sorrow

Dylan’s prisoner begins to pivot away from retribution and bitterness, and toward reconciliation and acceptance, in the second verse. The emphasis shifts from the fallen (“They say every man must fall”) to the risen (“I swear I see my reflection / Somewhere so high above this wall”). The singer breaks those “chains of sorrow” forged by anger and resentment that Prine warns about. And in the process, he restores his connection to the divine, seeing his face mirrored back at him as a child of God.

Dylan shifts the emphasis again in the third verse, focusing on a fellow prisoner. This man is still stuck in the position the singer was in at the beginning of verse one. He shouts and cries because he is still shackled by his chains of sorrow. The singer can pity this man because he’s been there himself. If the first prisoner can break free and achieve spiritual deliverance, then there’s hope for the second prisoner.

And by extension, there’s hope for us all, wrestling with the same hang-ups and obstacles, keeping ourselves confined by “mind-forg’d manacles,” to borrow an image from William Blake. Listen deeply enough to “I Shall Be Released,” and you just might find the key you’re looking for to unlock your own cell door, remove your chains, and shine your light.

Going Home

If the world and the body are prisons, as Dylan claimed in his 1978 interview with Philip Fleishman, then how does one escape? By leaving one’s current home in pursuit of another, the original and ultimate Home. As Dylan told Fleishman, “‘Most people are working toward being one with God, trying to find him. They want to be one with the supreme power, they want to go Home, you know. From the minute they’re born, they want to know what they’re doing here. I don’t think there’s anybody who doesn’t feel that way’” (qtd. Heylin 348).

In retrospect, it makes sense that Dylan was espousing these religious beliefs about a homecoming with God in 1978, on the cusp of his born-again conversion to Christianity. Perhaps it is more surprising to find him preaching this sermon in 1967 on “I Shall Be Released,” a prison song that morphs into a freedom song and a sacred hymn about deliverance.

Then again, hasn’t Dylan always been singing about trying to find his way home? We were just talking about this recently in a Patreon gathering for Laura Tenschert’s Definitely Dylan, and Laura touched upon this topic in her Denmark paper, too. Those of us who write about Dylan just can’t stop quoting those lines from No Direction Home because they cut straight to the heart of his work: “I was born very far from where I’m supposed to be, and so I’m on my way home.”

The man can read a map and afford transportation back to Minnesota. His journey home has never been about geography. It’s a spiritual journey, rooted in Dylan’s belief in an immortal spirit that was created by God, resides temporarily on earth inside a body, but instinctively longs for release so that it may return where it came from, the only place it truly belongs.

I’m no preacher. Hell, I’m not even much of a believer when it comes to heavenly homes. But I do believe in Dylan, and I believe in the power of song. When I listen to “I Shall Be Released” from the Basement Tapes, I come as close to feeling spiritual transcendence as I’m ever likely to experience. I don’t have to share all of Dylan’s beliefs in order to be profoundly moved by how deeply he and his bandmates invest everything in this plea for release.

It’s enough to make me hope they’re right. I guess Richard, Rick, and Robbie know now. [January 2025 update: Add Garth’s name to the roll called up yonder.] If there’s a home after this one, then they’ve already made it there. I hope it’s big and pink. I hope Leonard’s there, too, and I hope Bob waits a while longer before joining them.

Going home without my sorrow

Going home sometime tomorrow

Going home to where it’s better than before

Going home without my burden

Going home behind the curtain

Going home without the costume that I wore

Works Cited

Behan, Brendan. Brendan Behan’s New York. Little, Brown, 1964.

---. The Quare Fellow. The Quare Fellow and The Hostage: Two Plays by Brendan Behan. Grove Press, 1964, 1-86.

Blake, William. “London.” Poetry Foundation, https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/43673/london-56d222777e969.

Bono. Interview with Bob Dylan. Hot Press (26 August 1984). Rpt. Every Mind Polluting Word: Assorted Bob Dylan Utterances, ed. Artur Jarosinski, Don’t Ya Tell Henry, 2006, 805-10.

Cash, Johnny. At Folsom Prison. Columbia, 1968.

---. Orange Blossom Special. Columbia, 1965.

Cash, Johnny and the Tennessee Two. “Belshazzar.” Sun, 1957.

Cash, Johnny and the Tennessee Two. “Folsom Prison Blues.” Sun, 1955.

Cash, Johnny, with Patrick Carr. Cash: The Autobiography. Harper, 1998.

Callahan, Erin C. “Mixing Up the Medicine: Bob Dylan’s Basement Carnival and Homosocial Masculinity.” Bob Dylan: Questions on Masculinity Symposium. Odense Adelige Jomfrukloster, 23 May 2024.

Carney, Court. “Wanted Men: Bob Dylan and the Vulnerability of Brotherhood.” Bob Dylan: Questions on Masculinity Symposium. Odense Adelige Jomfrukloster, 23 May 2024.

The Clancy Brothers & Tommy Makem. Irish Songs of Drinking and Rebellion. Legacy, 1959.

Cohen, Leonard. “Going Home.” Old Ideas. Columbia, 2012.

Dont Look Back. Directed by D. A. Pennebaker. Leacock-Pennebaker, 1967.

Dylan, Bob. Chronicles, Volume One. Simon & Schuster, 2004.

---. The Official Lyrics. The Official Bob Dylan Website.

https://www.bobdylan.com/.

Griffin, Sid. Million Dollar Bash: Bob Dylan, The Band and The Basement Tapes. Jawbone Press, 2014.

The Holy Bible. King James Version.

Heylin, Clinton. Revolution in the Air: The Songs of Bob Dylan, 1957-1973. Chicago Review Press, 2009.

Hilburn, Robert. Johnny Cash: The Life. Little, Brown and Co., 2013.

Horstman, Dorothy. Sing Your Heart Out, Country Boy. Country Music Foundation Press, 1996.

Kiberd, Declan. Inventing Ireland: The Literature of the Modern Nation. Harvard University Press, 1995.

Love, Robert. “Bob Dylan Uncut.” AARP Magazine (February/March 2015), https://www.aarp.org/entertainment/celebrities/info-2015/bob-dylan-magazine-interview-process.html?intcmp=AE-ENT-CEL-NXT-BDYL.

Marcus, Greil. The Old, Weird America, updated edition. Picador, 2011.

No Direction Home. Directed by Martin Scorsese. Paramount, 2005.

Prine, John. “Bruised Orange (Chain of Sorrow).” Bruised Orange. Asylum, 1978.

Rotolo, Suze. A Freewheelin’ Time: A Memoir of Greenwich Village in the Sixties. Aurum Press, 2009.

Salvucci, Jim. The Dylantantes,

.

Simmons, Michael. “Robbie Robertson Remembered: ‘I remember saying to Dylan, there’s too many verses in this.’” MOJO (8 September 2024), https://www.mojo4music.com/articles/stories/robbie-robertson-interviewed/.

Thomas, Dylan. “Do not go gentle into that good night.” Poets.org, https://poets.org/poem/do-not-go-gentle-good-night.

Williams, Paul. Bob Dylan, Performing Artist, 1960-1973: The Early Years. Omnibus, 2004.

Williams, Tennessee. A Streetcar Named Desire. The Norton Anthology of Drama, shorter third edition. Eds. J. Ellen Gainor, Stanton B. Garner, Jr., and Martin Puchner. W. W. Norton, 2017.

Just transcendent, Graley. Gorgeous and compelling piece. Thank you so much!

Just brilliant, Graley. As I have been immersing myself in 1967 Dylan, I couldn't help but nod along with these beautiful readings and marvel, again, at how Dylan's restless mind turns from home, to basement, from prisons literal and figurative to the tumultuous America of 1967 outside of the Woodstock enclave: "There must be someway out of here...: