Dylan Lit: Dana Spiotta

Part 2, Stone Arabia

Life isn’t about finding yourself or finding things. Life is about creating yourself and creating things.

--Bob Dylan

In 2021, Dana Spiotta published an essay on Rolling Thunder Revue: A Bob Dylan Story by Martin Scorsese. As she sees it, “the director curates the archival footage to make an argument about how the tensions of the American cultural moment are a crucial part of the story of Bob Dylan. The singer-songwriter’s own acts of self-invention and reinvention seem to work out American contradictions on the plane of music and performance.” Some viewers balked at Scorsese’s intermingling of fact and fiction in the film, but Spiotta cites this approach as a strength: “By indicating that there are fictional things woven in among the real things, the film admits its artifice. This makes it more honest than a straight documentary, which also shapes the truth and has a point of view—so why not play with that?” She argues, “The fake-mixed-with-real runs deep in the American ethos.”

Spiotta quotes the Dylan line I use for my epigraph: “Life isn’t about finding yourself or finding things. Life is about creating yourself and creating things.” The novelist agrees: “Yes. Why isn’t this invented self—the self you create—the authentic self? Why is that faker than the self of birth and happenstance?” She champions self-invention, but she also acknowledges its complications and limitations: “It is critical to admit the complexity of this idea. Self-invention liberates us, but the past still exists. In The Great Gatsby, F. Scott Fitzgerald shows how our past can’t be left behind; it always catches up to us. Dylan is famous for not looking back, but what are the Dylan archives, or the interviews here, if not a form of looking back? Maybe the past shapes the possibilities we imagine.”

In the previous installment on Eat the Document (2006), we explored self-invention as it applied to fugitives on the run. For the present piece, let’s consider this issue as it relates to musician Nik Kranis (aka Nik Worth) and his sister Denise in Spiotta’s follow-up novel Stone Arabia (2011). Like last time, there’s no advance homework assignment. But I hope you’ll be inspired to read the book if you haven’t already.

Stone Arabia is a very different novel than Eat the Document, but certain signature preoccupations bind these books together, namely Spiotta’s abiding interests in art, identity, memory, obsession, and the endless struggle between creation and destruction, loss and preservation. Dylan is perennially engaged by these subjects, too.

Music plays an even more central role in Stone Arabia, and yet, unlike Eat the Document, there aren’t many overt references to Dylan. In fact, he is only mentioned by name once, very briefly, so we won’t be playing a game of Whack-a-Bob in this installment. Nevertheless, I still sense his shadow hovering over the book at several points, giving us plenty of opportunities for shadow chasing.

Origin Story

The first line of the novel is “She always said it started, or became apparent to her, when their father brought him a guitar for his tenth birthday” (1). The “she” is Denise Kranis, and the “it” is the musical obsession of her brother Nik. Three important factors converged to make Nik’s tenth birthday so special. The most important was the guitar, but it was inseparable from what came before and after receiving this gift.

Before the birthday party, Denise and Nik saw a matinee screening of A Hard Day’s Night and were immediately hooked:

Nik was a bit of a Beatle skeptic; he had the 45s, but he wasn’t sure it wasn’t too much of a girl thing. The movie erased all his doubt. Denise remembered how everything about it thrilled them—the music, of course, but also the fast cuts, the deadpan wit, the mod style, the amused asides right into the camera. The songs actually made them feel high, and in each instance felt permanently embedded in their brains by the second repetition of the chorus. They stayed in their seats right through the credits. If it wasn’t for the party, there was no question they would have watched it again straight through. (4)

What was gained from the musical gifts of the Beatles and the guitar was counteracted by the loss of the father, who blew in for the party, gave Nik his present, and then abandoned the family. Though they didn’t realize it at the time, the tenth birthday party was the last time Nik and Denise would ever see their father.

Spiotta’s setup here is effective on multiple levels. The association Nik makes between his guitar and his emotionally unavailable, chronically absent, and prematurely deceased parent surely makes a lasting impact on his music, inspiring songs of longing, tethered to something lacking or missing. Spiotta is surely mirroring the formative experiences of John Lennon and Paul McCartney. Lennon’s mother Julia died at age 44 when he was just 17. McCartney’s mother Mary died at age 47 when he was only 14. Both men were shaped by the missing mothers of their youth, and both artists tapped into those primal feelings for some of their most powerful songs.

Denise and Nik responded rapturously to the fun-loving Beatles in A Hard Day’s Night in 1964. However, the siblings were also poised to become ideal listeners for later mother-haunted ballads like Lennon’s “Julia” and “Mother,” or McCartney’s “Let It Be,” songs born from loss and longing.

The Beatles’ music is so irresistibly alluring that Spiotta might have chosen any number of entry points into the addiction. But she strategically selects the film A Hard Day’s Night as Nik’s gateway drug. This is such a meta-film, built upon the construction of an alternate reality.

The Beatles perform a highly stylized version of themselves in the film. A Hard Day’s Night depicts John, Paul, George, and Ringo in 1964 wearing their most entertaining Beatles’ masks [cf. Dylan’s Halloween concert that same year at the Philharmonic Hall: “I’ve got my Bob Dylan mask on!”]. This type of self-referential work established a precedent Nik would emulate in his own art.

Denise vividly remembers the first time she realized her brother was a prodigy. It happened with “Versions of Me,” “his great early song about playing poseur and then wondering why no one knew the real you” (25). She recalls the transformative effect the song had on her:

He began to play ‘Versions of Me,’ and all at once Denise’s very familiar but distant brother became someone else. This was truly the moment when she saw how different he was from everyone else she knew, including herself. He, just by singing his song, could change how she saw the world. He became a vivid human to her, someone who understood her as yet unnamed alienation. She had, all at once, a deep faith in his perception, as he pinpointed the way she often felt, angry at the world for misunderstanding her while playing at deliberately misrepresenting herself. (26)

Nik has it: the unnamable, unlearnable something that distinguishes the great from the good. The thing that makes artists like the Beatles and Dylan stand out as distinct, as if they are channeling some mysterious force and are guided by destiny.

We know from Dylan’s Chronicles that he views his own life and art as guided by forces beyond his understanding and control. Looking at Nik’s carefully preserved first guitar forty years later in 2004, Denise reflects upon its talismanic significance for her brother:

She knew he felt there was some destiny to the day he received it: the Beatles, the guitar, the last time they would see their father. She knew because Nik felt there was destiny in everything. The story was part of his legend: he hadn’t even wanted a guitar—it never occurred to him, he would claim with a laugh. And yet it changed his life. Which was true, it did change him. It took him over like a disease. (22)

Chronicles & Self-Invention

Like Dylan in Chronicles, Nik burnishes his own legend through an elaborate self-mythology. Beginning with his first band the Demonics in 1973, and right up through the novel’s present setting in 2004, Nik keeps a meticulous record about his music in a multi-volume compilation he calls . . . wait for it . . . the Chronicles!

The debt to Dylan is obvious, but here is Spiotta’s leap of genius: Nik’s Chronicles is fake. He makes the whole thing up! Well, not the music, the music is real. He has continued to compose, play, and record consistently ever since he got his first guitar. In fact, when it comes to the music, he is as diverse as he is prolific, first with his punk band the Demonics, then with his power-pop band called (oh so appropriately) the Fakes, and later with a fictional trio called the Pearl Poets, where he sings all three parts in different voices, along with writing all the songs and playing all the instruments. Nik makes all of this music in his Topanga Canyon apartment, records it on tapes (later discs), and gives out hand-decorated copies to his few friends and family members.

Nik never broke through in the music business, never went on tour, never signed with a label, never released any albums for sale in stores to the public. Nik Kranis has worked as a bartender at the same dive for thirty years and barely subsists at the poverty level. In the alternate reality of the Chronicles, however, Nik Worth is a music legend. How amazing is that?!

Denise fills us in on the back story:

By 2004 Nik had thirty-odd volumes of the Chronicles (going back to 1978 officially; unofficially they were retrofitted back to 1973 with the rise of the Demonics). They were written exclusively by him. They are the history of his music, his bands, his albums, his reviews, his interviews. He made his chronicles—scrapbooks, really—thick, clip-filled things. He wrote under many different aliases, from his fan club president to his nemesis, a critic who started at Creem magazine and ended up writing for the Los Angeles Times, a man who really hates his work. (36)

What a wonderfully self-reflexive conceit. Spiotta is through the looking-glass, referring to her own artwork from the other side of the mirror. The author attributes to her character the creative agency she herself exercises: making everything up, devising multiple personae, speaking in different voices, generating a solipsistic metafictional cosmos.

As with Dylan’s Chronicles, Nik’s Chronicles oscillate between the scrupulously candid and the outlandishly embellished. And as with A Hard Day’s Night, there is enough overlap between truth and fiction that it’s difficult to distinguish between the two. For instance, consider the curious (and hilarious!) case of Nik’s dead dog:

Nik’s Chronicles adhered to the facts and then didn’t. When Nik’s dog died in real life, his dog died in the Chronicles. But in the Chronicles he got a big funeral and a tribute album. Fans sent thousands of condolence cards. But it wasn’t always clear what was conjured. The music for the tribute album for the dog actually exists, as does the cover art for it: a great black-and-white photo of Nik holding his dog with an intricate collage along the edge consisting of images of the Great K9s of History from Toto to Lassie to Rin Tin Tin (credited as ‘the border collieage compiled by N. Worth’—Nik loved puns, and in the Chronicles all his loves ran without restraint, unfettered and unashamed). But the fan letters didn’t exist. In this way Nik chronicled his years in minute but twisted detail. The volumes were all there, a version of nearly every day of the past thirty years. (37)

Spiotta’s invention of Nik Kranis’s invention of Nik Worth in the Chronicles is a tour de force for anyone who digs postmodern metafiction. It reminds me of Virginia Woolf’s Judith Shakespeare, her thought experiment in A Room of One’s Own, imagining what it would be like if Shakespeare had a sister with all of his genius but none of his opportunity. Spiotta conducts a comparable thought experiment with Nik Worth, and this is where the shadow of Dylan looms large.

What would happen if someone possessed the same talent, devotion, ingenuity, and capacity for reinvention as Bob Dylan, but was denied an audience or any public outlet for his art? Her answer is brilliant: he would keep on creating anyway, supplying what was missing through simulation and fabulation, filling his void with the superabundance of his teeming mind.

Is Nik’s mind deranged? Some readers think so. In a roundtable discussion of Stone Arabia for Reluctant Habits, Levi Asher offers this assessment of Nik Worth: “His retreat into fantasy seems to me a mild analog to schizophrenia. His decision to detach himself from reality and find solace in a world of sarcastic self-reference is like Alonso Quijana’s decision to become Don Quixote. And everybody knew that Don Quixote was mad.”

Spiotta was invited to respond to the roundtable discussion, and she defended Nik in more sympathetic terms:

He is unapologetic and I see him as a resister. He has found a way to be the person he wants to be. He seems immune to the judgment of others. He is deeply unconventional and eccentric, albeit very self-obsessed. I admire Nik’s ability to create his own artistic world. He was supposed to quit and get a real job, or he should have gone out and promoted himself. But he isn’t interested in that, and he pays the price. He isn’t bitter — he has been content in his odd way.

Rather than accepting the disappointments of his life, Nik invents the counterlife he thinks he deserves through his Chronicles. To repeat Dylan’s motto: “Life isn’t about finding yourself or finding things. Life is about creating yourself and creating things.”

Memory / Archive / Technology

I respect the audacity and tenacity of Nik’s project, his refusal to accept the world’s verdict that his music doesn’t matter and neither does he. However, I haven’t had to put up with his bullshit for my whole life like his sister has. Denise genuinely loves Nik’s music and is his #1 fan (not that there’s any competition). But she finds her brother frequently exasperating and self-destructive, one more person in her life that she’s responsible for looking after, as if she didn’t have enough problems of her own.

Early in Stone Arabia, but late in the story’s chronology, Denise begins writing what she calls “The Counterchronicles.” In this journal from 2004, she reconstructs the year’s events leading up to some unspecified “crisis” that took place around Nik’s fiftieth birthday. [By the way, Nik’s birthday is May 25, the day after Dylan’s birthday.]

Denise begins her Counterchronicles with a disclaimer:

You can go back forever to grab a context for a brother and sister. And even then the backward glance is distorted by the lens of the present. The further back, the greater the distortion. It is not just that emotions distort memory. It is that memory distorts memory, if that makes any kind of sense. I must simply try to recall the events that led to our crisis (let’s call it that for now). (28)

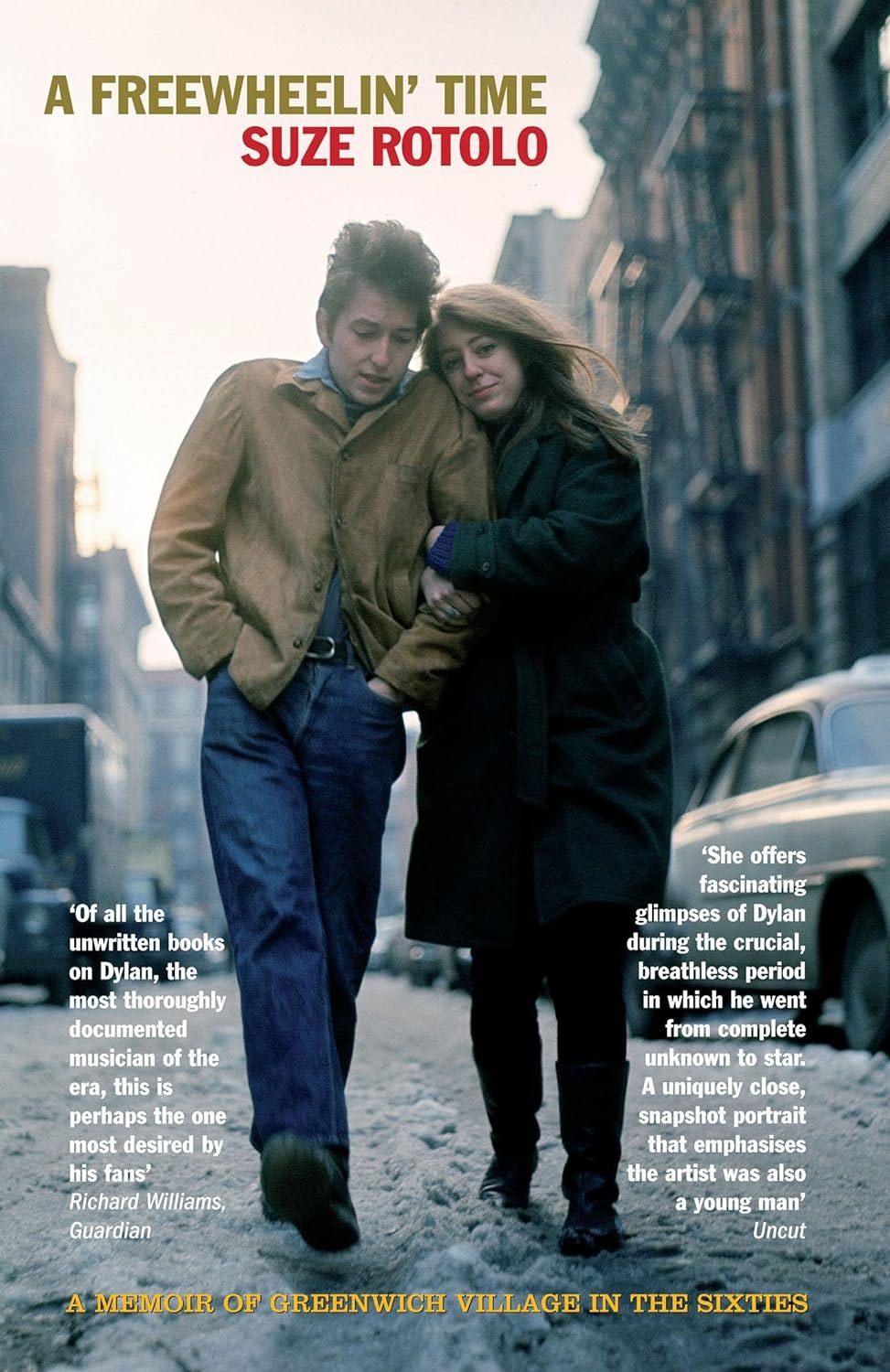

Denise’s Counterchronicles relates to Nik’s Chronicles in much the same way that Suze Rotolo’s memoir relates to Dylan’s Chronicles.

Rotolo titles her memoir A Freewheelin’ Time: A Memoir of Greenwich Village in the Sixties, an allusion to the famous album cover where she and Dylan walk arm in arm down snowy Great Jones Street. She might just as well have called the book Counterchronicles.

Dylan and Rotolo both do an effective job of capturing their initial attraction, but she goes into greater detail about what pulled them apart. There was the lying and cheating of course. But more than anything, she refused to accept a supporting role as handmaid to a genius who pored all of his best energy into art and saved little for anything or anyone else:

I knew I was not suited for his life. I could never be the woman behind the great man: I didn’t have the discipline for that kind of sacrifice. Though I wasn’t sure where I was going and lacked a sense of mission or ambition, I knew what would not work for me, even if I was uncertain what would. I just knew with all my heart that I could not be a string on his guitar. I could not live in his shadow and I was ill-equipped to be his caretaker. (Rotolo 287)

Suze broke up with Bob. But as Nik’s sister, Denise doesn’t have that luxury. In a conversation with John Emrys Eller for 12th St: The Journal of Writing and Democracy, Spiotta says she chose to focus on a sister rather than a lover for precisely that reason: “At the same time I was thinking of a private artist, I was thinking of the person who loved and cared for him. I really didn’t want it to be a romantic love affair. I wanted it to be a life-long relationship, so I thought it should be a sibling. Only after I began to write did the ideas of memory and family get involved.”

Both Suze and Denise foreground the slippery unreliability of memory. Rotolo asserts in her opening chapter: “The only claim I make for writing a memoir of that time is that it may not be factual, but it is true” (2). She adds that “because memory is the joker in the deck I try not to take the representations of the past too seriously” (3).

Memory is one of the main subjects of Stone Arabia, and Spiotta examines it from multiple perspectives. Ella Kranis, mother to Nik and Denise, has been diagnosed with the early stages of dementia, and as her mother’s main caregiver, Denise witnesses Ella’s slow erasure through memory loss.

Spiotta has a keen eye for detail in documenting this decline. For instance, consider Ella’s growing fixation with paperwork. “Now she was interested in coupons, receipts, bills, instructions, warranties, paper trails of any kind. She kept things to show me. As she grew anxious, the receipts proved something of a comfort to her, a concrete thing she could hold that wouldn’t fade like the things she was constantly trying to recall” (46-47). It’s a perceptive observation, and one that gets me thinking about the relationship of memory to archive.

Dylanologists have long hoarded every scrap of evidence, every discarded track, every trivial artifact related to Dylan, as if these things might somehow bring us closer to the mystery of why his work means so much to us. The term derives from AJ Weberman, who literally sifted through Dylan’s trash in search of clues about his life.

After a lifetime of being targeted by stalkers, obsessive fans, ravenous critics, and pedantic professors, it should come as no surprise that Dylan is wary of such activities, which he dismisses as pathetic and perverse. “The world of research has gone berserk / Too much paperwork,” as he puts it in “Nettie Moore.” That’s why so many of us were shocked—and delighted—when he donated his materials to Tulsa and we discovered that the man has been saving enough notes, manuscripts, recordings, and detritus over the years to fill up a museum.

Why did he save these things? I think of Eliot’s line from The Waste Land: “These fragments I have shored against my ruins.” Each fragment may be insignificant in itself, but combined they form a levee to fend off the rising tide of oblivion. Though I still haven’t fully wrapped my head around it, I sense some connection between Nik’s Chronicles, his mother’s paperwork, and Dylan’s archive. Mind you, Spiotta’s novel came out five years before Dylan sold his archive to the George Kaiser Family Foundation in Tulsa, so I’m not suggesting that she used it as a direct reference. I’m just saying that her fiction inspires me to think more deeply about bedrock principles related to memory, loss, preservation, and the archival impulse.

Fun fact: Dana Spiotta has an amazing personal connection to Tulsa and Dillon. No, that’s not a misspelling. As a tenth-grader, Dana Spiotta spent her summer in Tulsa on the set of Francis Ford Coppola’s 1982 film Rumble Fish, starring Mickey Rourke and Matt Dillon.

She explained how this came about in a conversation with Oklahoma author Constance Squires:

My father and mother went to Hofstra College with Francis Coppola. My parents fell in love while they were performing in a Coppola-directed production of A Streetcar Named Desire. My dad played Stanley and my mom played Stella. […] Anyway, my father became the president of Coppola’s studio, Zoetrope. Francis loved kids and always took a special interest in me. I wanted to be a film director, so he invited me to Tulsa to be a “student observer” while he filmed Rumble Fish. It was 1982, and I was 16. I spent the whole summer there.

Pretty cool, huh? Check out the full story where she talks about being treated kindly on the set by Tom Waits and having a conversation about James Dean with Dennis Hopper.

Spiotta shrewdly observes how our vexed relationship with technology has warped our capacity to remember. Even before smartphones made it so easy to take pictures that most of us walk around with a gallery’s worth of images nestled in our pockets, Spiotta diagnosed the detrimental relationship between photos and memory. Denise offers this provocative critique:

It does not help, having a photo. I believe—I know—that photos have destroyed our memories. Every time we take a photograph, we forget to embed things in our minds, in our actual brain cells. The taking of the photograph gets us off the hook, in a way, from trying to remember. I’ll take a photo so I can remember this moment. But what you are really doing is leaving it out of your brain’s jurisdiction and relying on Polaroids, Kodak paper, little disintegrating squares glued in albums. Easily lost or neglected in a box in your waterlogged garage. Or you bury it in some huge digital file, waiting to be clicked open. All you have done is postponed the looking and so the actual engaging, until all you are left with is this second-generation memory, a memory of an event that is truly only a memory of a photograph of the event. It is not a real, deep memory. It is a fake, fleeting one, and your mind can’t even tell the difference. (52)

I am completely persuaded by this argument. Susan Sontag or Roland Barthes couldn’t have said it better. It’s obvious that Nik creates fake memories when he constructs a fictional history of his nonexistent celebrity past. However, Spiotta suggests that we all routinely produce fake memories. In place of independent, unmediated memories of the past—which, let’s face it, was always a fantasy—we substitute retrospective simulations based upon select (and often staged) images of those events.

Nik may come across at first as an outrageous fraud, but Denise reveals ways in which we commonly replicate his fabulism in our own daily lives. It’s worth remembering that the present setting of Stone Arabia is 2004, the same year that Facebook launched, and Spiotta’s manuscript was completed in 2010, the same year that Instagram launched. The very behavior that makes Nik seem so outlandish and idiosyncratic in his own time are so commonplace today that we take them for granted without a second thought. Social media enables and encourages people to adopt the practices of Nik Worth, compiling highly curated self-chronicles, often fueled by embellishments and fantasies that bear little resemblance to the creators’ actual lives.

Before I come across as some finger-wagging, gavel-banging judge, I should plead guilty to similar charges. No, I’m not on Facebook, X, Instagram, etc. But I am essentially compiling a self-archive of my own work here on the pages of Shadow Chasing.

In her conversation with Eller, Spiotta recognizes the resonance between Nik’s project and today’s social media, but she points out that Nik’s Chronicles is more like antisocial media:

I am interested in writing about technology because I am interested in examining—in an off-kilter way—what it is like to live now. I like thinking about outdated technology; it seems to be a good lens for examining our current moment. So the book doesn’t contain Facebook or Twitter, but I think it has a dialogue with social media. You could view Nik as exhibiting a variation of the self-dramatization and documentation that social media encourages. But Nik’s form is totally of his own devising and it has no “social” component. He has his own low-fi antisocial version of Facebook; he is, as he says, a paste and paper guy.

The Ontology of Worth

Although Nik Worth inspires me to think more deeply about Dylan, I don’t want to give you the misimpression that he is merely a knock-off substitute. Much of Nik’s music sounds nothing like Dylan’s output. For instance, consider his long-running solo project, The Ontology of Worth. This twenty-volume series might remind you of Dylan’s long-running Bootleg Series, but the resemblances end there.

According to the liner notes of Volume 2, Ontology features a recurring character named Man Mose.

Full of cryptic references, Man Mose (one gathers) lives in tunnels under the streets and hears things through the ground as he moves from place to place. He apparently makes or records his “music” all the time. Side two is the music MM hears (makes?). Underground music, indeed. Who would have guessed that what we were all waiting for was a collection of atonal, arrhythmic assault compositions mixed with concept sound poems? (90)

This project sounds more like something from David Bowie or the Flaming Lips than Dylan. Remember that these liner notes, like everything else in the Chronicles, is written by Nik himself. In this case, he assumes the alias Mickey Murray and gives him the greatest job title I’ve ever heard: “Greil Marcus Professor of Underground, Alternative, and Unloved Music”! Where can I apply?

The first time I read Stone Arabia, I was surprised to arrive at the end of the novel and discover that Nik Worth is actually based in part upon a real person. In a closing author’s note, Spiotta writes, “Although this novel is a work of fiction and Nik Worth is a character of my imagination, my inspiration for him is a real-life person, my stepfather, Richard Frasca, a.k.a. Jon Denmar. Richard Frasca is not Nik Worth, but Richard’s devotion to his own music and Richard’s self-documented chronicle of his life as a secret rock star gave me the idea for Nik. Thank you, Richard, for your generosity. You are a true artist. Viva Village” (237). [Village is the name of his band.] If you think this sounds as awesome as I do, you can learn more about Frasca’s work on his website called (of course!) Fake Records.

In her conversation with Eller, Spiotta mentioned additional inspirations: “Mingering Mike makes fake record albums, labels, etc. I had a lot of people in mind. There are cult musicians like Jandek and R. Stevie Moore. […] I spent a lot of time looking at outsider art. Anyone who had a secret enduring obsession was interesting to me, especially private artists, the people who don’t care if they have an audience.”

She provided an even longer list of models in her BOMB interview with David Humphrey: “I thought about (and sometimes listened to) a number of off-center musicians: Robert Pollard, Syd Barrett, Alex Chilton, Roky Ericson, Skip Spence, Jandek, R. Stevie Moore, Emitt Rhodes, Johnny Thunders, Calvin Johnson, Epic Soundtracks and Swell Maps, and many others.”

These lines from Swell Maps’ “H.S. Art” seem particularly prescient:

Are you intent on making it?

Maybe even faking it?

Then you’ll see the real me

Then you’ll see what we can do […]

Do you believe in art?

Do you believe in art?

Do you believe in art?

Dylan, who has millions of fans worldwide, has always been skeptical of his audience’s obsession with him and his music. Nik, who is a complete unknown with no fans, craves listeners just as consumed by his art as he is. In a (self-authored) interview promoting Ontology, Volume 2, in the imaginary fanzine Butter Your Toast, the interviewer asks, “How do you expect your fans to listen to it?” Nik humbly responds,

I expect complete and total attention for all of my work. I want my fans to drop whatever else is going on and devote themselves. I want them to listen, with rapt and dire attention, to the prior eighteen volumes, in order, and then I want them on their knees, eyes closed, with the whole fifty-six minutes of the CD played at top volume. I want them to repeat that undistracted deep listening until they see the patterns, themes, and ideas that link and resonate through the entire nineteen volumes. I want them to understand any failings they may perceive in the work as part of its terrible beauty, and I want them to embrace the mystery and beauty of the project as a whole. Then I want them to hold those thoughts and feelings and wait breathlessly for the final chapter—Volume 1. Soon to come. That’s all I expect. (93)

Brilliant! In short, he wants to be listened to like Dylan and the Beatles are listened to, the way James Joyce is read.

Spiotta told Squires, “I think the book that matters (and has mattered) the most to me is Ulysses. Reading Dubliners and Ulysses as a young person made me want to write. It gave me ideas about what was possible. It felt as if a secret had been whispered to me.” Nik seems to be echoing Spiotta’s favorite writer in the fake interview above. In a real interview with Max Eastman, Joyce claimed, “The demand that I make of my reader is that he should devote his whole life to reading my works.”

Monomaniacal as Nik’s Chronicles may sound, there is also something inviolable and perfect (too perfect?) about his archive, a self-contained utopian community of one. But a few factors threaten Nik’s peaceful equilibrium. For one, he’s about to turn fifty, an age which tends to prompt reflections on legacy and mortality. Furthermore, his magnum opus, The Ontology of Worth, is nearing completion.

Ontology: the study of being. To be or not to be? Is the overexamined life still worth living for Nik on the other side of fifty and Ontology? To put it bluntly, Denise fears that her brother plans to commit suicide on his fiftieth birthday.

Garageland & Basementland

There’s another wild-card factor: Denise’s daughter Ada has decided to make a documentary film about her uncle. “‘I think I want to make a movie about Nik,’” she announces to her mother. “‘You know, he really is like a folk-art genius. Not just the music but the whole deal, the whole constructed lifelong thingy. He would totally be a great subject’” (70)

Could this film save Nik from obscurity and pathological obsession, giving him a purpose and maybe even an audience? Or would such exposure destroy his fantasy and send him over the edge? Does a legacy project like Ada’s documentary demand the death of its subject as prerequisite? It’s a serious concern. As Nik himself morbidly muses late in the novel, “‘I’ll be the next Henry Darger. Do you remember how that movie ended? The outsider artist dies and the whole world discovers he was secretly a genius’” (184).

Denise gets the appeal of Nik as a film subject. But she suspects this type of scrutiny could fatally disrupt Nik’s tenuous balance. “‘Let’s put it this way,’” Denise explains to Ada. “‘I think his whole life is a private joke that he doesn’t want to explain to anyone. […] And I think part of his pleasure, or at least his freedom, is he doesn’t think anyone will see it or judge it’” (71).

Ada presses ahead with the documentary anyway. To Denise’s surprise and concern, Nik agrees to open up his archive to his niece and participate in the film. Ada announces the news on her blog:

I am heading out to LA to start filming my documentary, Garageland. Garageland is about a life spent making music and art outside the mainstream. Way outside. It is a celebration of a devoted unrepentant eccentric. It is about living out a secret fantasy life of your own making. Do you need an audience to create work, or does not having an audience liberate you and make you a truer artist? And ultimately, Garageland will question what makes a person produce in the face of resounding obscurity. (143)

You might recognize “Garageland” as a song by the Clash. Spiotta uses a quote from the song as an epigraph for Stone Arabia: “I just wanna stay in the garage all night” (ix).

Reading Ada’s idea for Garageland, I find myself thinking of Basementland: that brief, artistically fertile period Dylan spent with the Band in Big Pink, making music for pleasure with no intention of ever releasing the basement tapes to the public. What an ideal laboratory for experimentation and creative liberty. Of course, for the ever-restless Dylan, such conditions were never going to remain in place for long. But for Spiotta’s Bizarro-World Dylan, Nik Worth has effectively remained inside the gates of his Edenic Garageland for thirty years.

Spoiler alert: Nik doesn’t commit suicide. He does disappear, however, after completing the final volume of The Ontology of Worth. When Denise arrives at his apartment, his guitars are gone, but everything else remains intact, including his archive. He apparently decided to start over and reinvent himself as someone else somewhere else.

That said, the final entry of Nik’s Chronicles, waiting for Denise to find on his desk, bears the chilling headline: “Nik Worth, Rock Star Turned Eccentric Innovator, Dies at 50” (198). Nik Kranis’s final creative act in the Chronicles is to kill off Nik Worth and write his obituary. It begins: “Nik Worth, the eccentric genius and reclusive oddity, died yesterday of an apparent suicide. He was found unconscious at his home by his sister, Denise Kranis” (198).

The simulation is macabre, but also darkly entertaining, like conducting an Easter egg hunt in a graveyard. For instance, according to the obituary, Nik had a fateful motorcycle crash in 1980 (cf. Dylan’s crash in 1966); his first efforts in The Ontology of Worth were dismissed by some critics as “Worth’s Folly” (cf. Dylan’s poorly received debut record dismissed as “Hammond’s Folly”); his hermitage for producing music is located on Skyline Drive in Topanga Canyon (same address as Neil Young).

The completion of Nik’s invented life prompts a postmortem from his sister on the relation between his real and fictional selves.

I think it is funny, and no doubt not at all lost on Nik, that in the end, his life in the Chronicles wasn’t all that different from his real life. In some ways it was worse, and in other ways it was exactly the same. Not a fantasy perfect life at all, just a different life, perhaps a more artful life. But in the Chronicles he wasn’t the author of the Chronicles, which was arguably the thing he had grown to be proudest of as time went by. (200)

After Nik’s disappearance, Ada shares footage with her mother from her interview with Nik for Garageland. In the interview, Ada observes, “The Chronicles are not just a casual hobby, are they? They are extremely elaborate, the work of a lifetime of effort. They appear to be considered down to the tiniest detail.” Nick replies,

You want to know how detailed? Let’s put it this way. If the Chronicles are dug up two hundred years from now, the readers would find them entirely plausible. It would be hard to believe they are conjured from nothing. Particularly when I have all the music. I kept close track. I kept the internal logic and continuity. I have the accompanying scholarship. Verifications could be made. (206)

Spiotta seems to be winking in Joyce’s direction again. The Irish novelist boasted to his friend Frank Budgen that, in faithfully reconstructing the setting for Ulysses, he wanted “to give a picture of Dublin so complete that if the city one day suddenly disappeared from the earth it could be reconstructed out of my book.”

Ada finally comes right out and asks Nik why he created this elaborate fantasy. “But why make a fake life? Why not do it with real life and get a real audience for all your work?” Nik objects to this misunderstanding of his life’s work.

It wasn’t fake, it was real. And I grew to like not having an audience. Imagine being freed from sense and only having to pursue pure sound. Imagine letting go of explanations, of misinterpretations, of commerce and receptions. Imagine doing whatever you want with everything that went before you. Imagine never having to give up Artaud or Chuck Berry or Alistair Crowley or the Beats or the I Ching or Lewis Carroll? Imagine total freedom. (211, emphasis added)

Total freedom from all the extraneous bullshit that distorts and distracts from the music—what could be better? Never mind the bollocks, here’s Nik Worth. “Businessmen they drink my wine, plowmen dig my earth / None of them along the line know what any of it is Worth.”

On one hand, Dylan has longed for exactly the conditions of unfettered freedom Nik Worth describes and defends here. Maybe it’s wrong to conceive of Nik as a failed Dylan; maybe he’s Dylan’s dream come true, Dylan to the Dylanth degree. Nik doesn’t have to quit Maggie’s Farm because he was never indentured there in the first place.

On the other hand, for all the tensions and periodic clashes with his fans, it’s hard to fathom Dylan divorced entirely from live performance before an audience. He tried it for the better part of eight years in the late sixties and early seventies but eventually couldn’t stand the separation any longer.

But give the man credit: Dylan knows how to make the most of a sabbatical. During those glorious months in Basementland, he embarked upon an experiment comparable to that of Nik Worth, living humbly, making tons of interesting and fulfilling music, reimagining an alternative self—creating a counterlife. And my god, look how much he accomplished off the road during the pandemic—painting an exhibition’s worth of new canvases, writing The Philosophy of Modern Song, recording his latest masterpiece Rough and Rowdy Ways. Provide Dylan with a little time, space, distance, and privacy, and he’s a whirling dervish of creativity, whether it’s by choice in the basement or by necessity during lockdown.

Versions of Me

In her interview with Nik for Garageland, Ada asks him who his audience is. He answers, “Myself. Other than that, I don’t have one, I suppose. Some family and friends” (210). Ada mentions her mother as Nik’s audience, but he resists that label: “My sister doesn’t count as my audience because she feels like an extension of me. She’s, well, an alternative version of me” (210, emphasis added). Fascinating. You’ll recognize the echo of Nik’s first major song, “Versions of Me.” This passage makes me wonder about a bigger question that keeps tapping me on the shoulder.

How far are we meant to press this notion of Denise as an “alternative version” of Nik, as alter-ego or mirror-image? Might we take it so far as to speculate that one could be inventing the other?

It’s not so crazy to imagine a single person could be capable of creating the entirety of this fictional world when you consider that’s precisely what Dana Spiotta did. Is it likewise possible that Denise invents Nik as a projection of her ideal underground artist? Or that Nik invents Denise as a projection of his ideal imaginary listener?

Let me pursue this theory further. Periodically Spiotta inserts a gap in Denise’s Counterchronicles, then the voice switches from first-person to third-person. Why? At the very least, it’s a rhetorical gesture to make us question the narrative perspective, drawing attention to alternate versions of me/he/she/they. Maybe we’re meant to read even more significance into these ruptures. Maybe Spiotta is constructing a metafictional house of mirrors in Stone Arabia.

During my research, it was reassuring to find one other reader who shared a similar hunch. In the Reluctant Habits roundtable discussion of the novel, Sarah Weinman speculates that “this whole massive project may be in Denise’s head, a manifestation of shifting (even failing) memory, or that she essentially created ‘Nik Worth’ so she had a more legitimate way of expressing her artistic self.” Bingo! I had initially been leaning toward Nik as the embedded author, but the more I contemplate it, the more I’m convinced that the controlling consciousness of Stone Arabia must be Denise.

On several occasions, Denise experiences what she calls “fragile border moments” or “breaking events,” where distinctions dissolve between self and other, internal and external. “They are what I call the permeable moments: the events that breached the borders of my person. Let’s call them breaking events. I don’t mean breaking news. I mean breaking of boundaries. These are incidents that penetrated my mind, leaked the outside inside” (106). She cites several examples from news stories (e.g., the Abu Ghraib prisoner abuse, the Beslan school siege) where she empathizes to the point of trauma, as if these terrible events are happening to her. Nik’s alternative, shutting out the world entirely and retreating into a solipsistic inner sanctuary of art, must seem far preferable in comparison. How far down the rabbit hole will Denise go in pursuit of Wonderland? Is she capable of becoming Wizard of her own Oz? Could she be the chronicler behind both the Chronicles and the Counterchronicles? Is Denise wearing her Nik mask?

When Spiotta first began working on Stone Arabia, her primary focus was on Nik Worth. However, her approach shifted over time. In her response to the Reluctant Habits roundtable, she recalls that “as I was working, I realized that the sister—the audience—would narrate it, had to narrate it. And the thing became a novel of consciousness. As a writer I am really interested in the depiction of consciousness in fiction. I think the novel describes— enacts—the experience of a mind better than any other medium.” Now of course, one can narrate events and characters without necessarily inventing them. But when Spiotta says the sister not only describes but also enacts experiences of the mind, it feeds my suspicion that Denise could be the single consciousness generating the entirety of Stone Arabia.

Spiotta doubles down on the mirror dynamics of total identification in the final chapter. This flashback takes place in 1972 and is written in first person, present tense, from Denise’s perspective. There’s literally a mirror scene where both Denise and Nik stare into the looking-glass as she teaches him how to apply eyeliner.

In the conclusion Denise merges with the music she listens to in the garage. Though she doesn’t use the phrase “alternative version of me,” she invokes the same concept through musical identification: “That voice, I can’t explain how much it fits with what I am feeling, what I want and need, alone in the garage. I start to sing along and I feel something else: I feel like I am him, this is my little edge of want. So I want to be the voice and I want to be the one the voice wants. All of it at once. I want it so bad” (235, emphasis in original).

This final passage of the novel is another breaking event of sorts, but here the effect is creative for Denise rather than destructive, inducing ecstasy rather than anxiety. The singer permeates the listener’s borders, the two intermingle as if one, in a duet of musical nirvana.

Ah, if only such moments could last. It’s satisfying to conclude on such a thrilling note, but let’s not forget that this final chapter is set in 1972, before all the crises in the preceding narrative transpired, before time ravaged members of the Kranis family, as it does for us all. “Time is a jet plane, it moves too fast / Ah, but what a shame if all we’ve shared can’t last,” as Dylan sings in “You’re a Big Girl Now.” I wonder if Spiotta gives her fictional family the name Kranis as a play on Chronos: Father Time. Time the revelator, time the conqueror, time the chronicler.

Dana Spiotta should get the last word here. Let me share this brilliant and beautiful meditation on the relationship of fiction to history and memory to the past. In her BOMB interview she reflected:

Maybe fiction is to history what your memories are to your past. Subjective, distorted, even parasitic, but something hard-felt and recognizably human. Fiction is good at getting at the way people engage with historic events or facts. If all our memories are memories of memories, or memories of photos or images of events, with an experience at the end of the chain or not, verifiable or not, then we are all constructing something—a personal version of the past and of how the world operates—that isn’t all that different from an ongoing art project, or a life-long narrative, a kind of autobiographical novel. So history owns the verifiable facts, but everything else—all our personal memories—are these constantly mutating, deeply connected, constructed things. Novels can occupy the space between consciousness and facts.

Works Cited

Champion, Edward. “Stone Arabia Roundtable – Part One.” Reluctant Habits (11 July 2011), https://www.edrants.com/stone-arabia-roundtable-part-one/.

---. “Stone Arabia Roundtable – Part Five.” Reluctant Habits (15 July 2011), https://www.edrants.com/stone-arabia-roundtable-part-five/.

Dore, Florence, ed. “Precious Resource (Rock and Our Generation of Novelists): An Interview with Jonathan Lethem and Dana Spiotta.” The Ink in the Grooves: Conversations on Literature and Rock ’n’ Roll. Cornell University Press, 2022.

Dylan, Bob. Chronicles, Volume One. Simon & Schuster, 2004.

---. Official Song Lyrics. The Official Bob Dylan Website.

https://www.bobdylan.com/.

Eliot, T. S. The Waste Land. Poetry Foundation, https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/47311/the-waste-land.

Eller, John Emrys. “A Conversation with Dana Spiotta.” 12th St: The Journal of Writing and Democracy (27 November 2012), https://www.12thstreetonline.com/a-talk-with-dana-spiotta/.

Humphrey, David. Interview with Dana Spiotta. BOMB (10 July 2012), https://bombmagazine.org/articles/2012/07/10/dana-spiotta/.

“James Augustine Aloysius Joyce (1882-1941).” Author’s Calendar, http://authorscalendar.info/jjoyce.htm.

Rolling Thunder Revue: A Bob Dylan Story by Martin Scorsese. Directed by Martin Scorsese. Netflix, 2019.

Rotolo, Suze. A Freewheelin’ Time: A Memoir of Greenwich Village in the Sixties. Aurum Press, 2009.

Spiotta, Dana. “Rolling Thunder Revue: American Multitudes.” The Criterion Collection (19 January 2021), https://www.criterion.com/current/posts/7248-rolling-thunder-revue-american-multitudes.

---. Stone Arabia. Scribner, 2011.

Squires, Constance. “Books, Movies & Rock ’n Roll: A Conversation with Dana Spiotta.” This Land (8 September 2014), https://thislandpress.com/2014/09/08/books-movies-rock-n-roll-a-conversation-with-dana-spiotta/#google_vignette.

Swell Maps. “H.S. Art.” A Trip to Marineville. Rough Trade, 1979.