Dylannati

Introduction to Series on Dylan in Cincinnati

My wife Cathy and I moved to Cincinnati in the summer of 1998. I had recently taken a job as an assistant professor of English at Xavier University after making my first trip to Cincinnati for the interview. I was 28 years old and had just finished up my doctoral work at Florida State University. My final year of grad school was mostly spent working on a dissertation about Samuel Beckett’s film and television plays, and my musical obsession during that period was Bob Dylan’s haunting new album Time Out of Mind. Like most diehard fans, I initially fell in love with Dylan as a teenager. My first memory isn’t of a song or an album but a book. My mother gave me Lyrics, 1962-1985 as a Christmas present in 1985, so I was first exposed to Dylan’s words long before I heard most of his songs (which may explain a thing or two). By the time I relocated to Cincinnati, I had seen Dylan in concert, but only a few times.

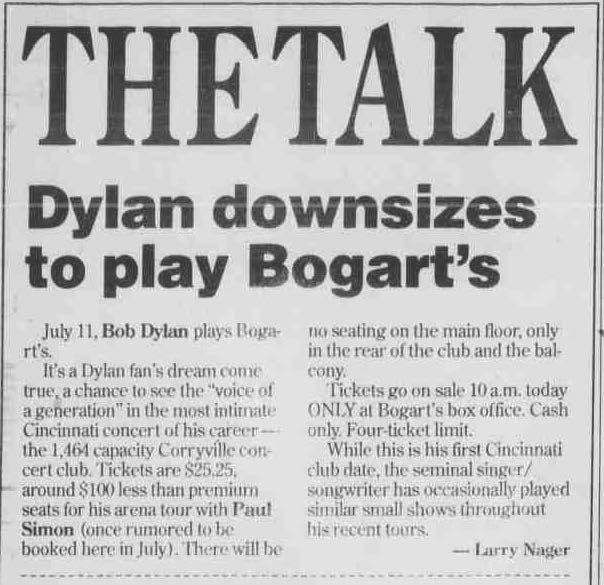

Getting oriented to a new job, home, and city consumed most of my attention that first year in Cincinnati, so I wasn’t really thinking much about Dylan. That changed on Saturday morning, June 26, 1999, when I opened up the Cincinnati Enquirer and read this surprising announcement from music journalist Larry Nager:

This was the first public announcement of the show, and tickets went on sale that day, cash only, exclusively in person at the box office. But, hey, it was a sunny morning and I was on summer break, so why not? I grabbed my keys, drove five miles from my apartment in Norwood to the University of Cincinnati campus, found parking on a side street near the club, and hustled over to Bogart’s . . . to encounter the longest line I’ve ever seen in my life. It snaked for blocks around the Corryville neighborhood, like a scene from Dylan’s 1966 England tour. I took my place at the back of the line despite having little chance of making it to the box office in time. Sure enough, after a couple hours waiting in the oppressive heat, word started to spread: Sold Out.

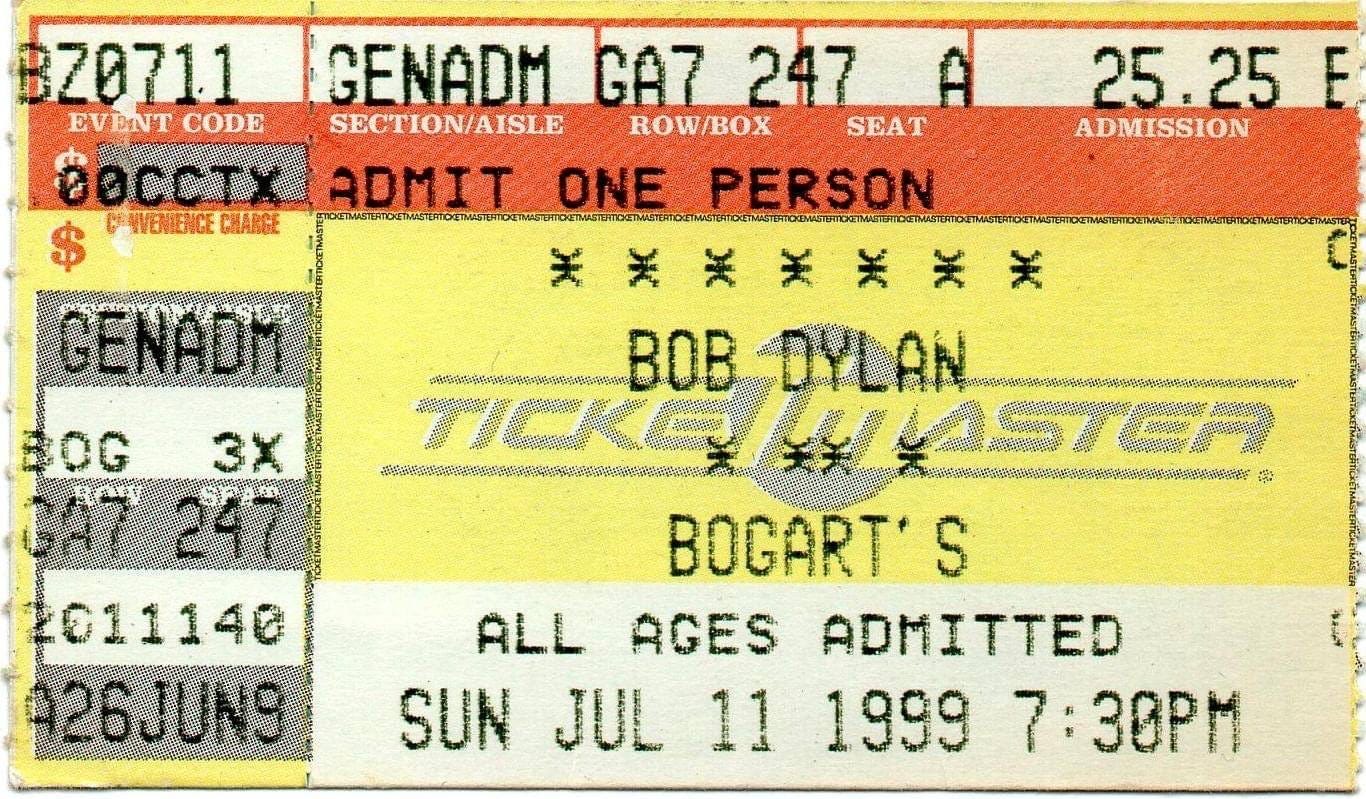

I sulked for a couple days. Dylan in a local dive bar and I was going to miss it?! I whined about my rotten luck to my new Xavier colleague, Alison Russell, and she put me in touch with her husband, who was in the local record business. Somehow Byron Russell scored me a single general-admission ticket, and there I was: in the same room with Bob Dylan and his band at Bogart’s on July 11, 1999. I wormed my way closer and closer to the stage, and by the time the show started I was right up front. If Dylan had called out to the packed house for an E harmonica, I could have held the damn thing to his lips. And it was an amazing performance! But I’m just giving you a tease. Much more to follow in a future post on the Bogart’s show.

Overview

I am working on a project studying Dylan’s many concert performances in Cincinnati. My long-range plan is to turn this study into a book called Dylan in Cincinnati. Along the way, I want to share this work with readers of Shadow Chasing. The present post is the first in a series of installments on the subject. In this introduction I want to lay some foundational principles and approaches for the entire project. As I write this in April 2023, Dylan has played 19 concerts in the Cincinnati area (which I’m defining as within ten miles of downtown):

1. March 12, 1965, at Taft Theatre downtown

2. November 7, 1965, at Music Hall in Over-the-Rhine

3. October 15, 1978, at Riverfront Coliseum downtown

4. November 4, 1981, at Music Hall in Over-the-Rhine

5. November 5, 1981, at Music Hall in Over-the-Rhine

6. June 22, 1988, at Riverbend Music Center in Anderson Township

7. August 10, 1989, at Riverbend Music Center in Anderson Township

8. November 3, 1992, at Music Hall in Over-the-Rhine

9. February 19, 1998, at Cincinnati Gardens in Bond Hill

10. July 11, 1999, at Bogart’s in Corryville

11. July 11, 2000, at Riverbend Music Center in Anderson Township

12. November 4, 2001, at Cintas Center on the campus of Xavier University

13. October 15, 2007, at Taft Theatre downtown

14. August 22, 2008, at National City Pavilion in Anderson Township

15. November 3, 2010, at The Bank of Kentucky Center on the campus of Northern Kentucky University

16. August 26, 2012, at PNC Pavilion in Anderson Township

17. July 6, 2013, at Riverbend Music Center in Anderson Township

18. November 8, 2019, at BB&T Arena on the campus of Northern Kentucky University

19. November 9, 2021, at Aronoff Center downtown

I plan to carefully examine the majority of these concerts in Dylan in Cincinnati. My work is inspired by too many previous scholars to list here, but Paul Williams and Andrew Muir deserve special mention. Williams sets the gold standard for writing about the performative dimension of Dylan’s art in his three-volume series, and Muir chronicles a committed groundling’s view of the first two decades of the Never Ending Tour in The Razor’s Edge and One More Night. Both writers provide creative inspiration and practical blueprints for my study. I share Muir’s approach and appreciate his candor in the preface to One More Night:

I want to tell you about this fan’s experience of the NET. That experience has been both a cherished and an exhilarating one, though admittedly not without a degree of obsession that borders on the unbalanced. At the same time, this is not simply a fan’s memoir; I do intend to bring some critical analysis, objectivity and balance to my account, though these are not always qualities I can guarantee to take to the shows themselves. (ix)

An important distinction between my work and that of Williams and Muir, however, has to do with scope. Before his untimely death, Williams managed to comment, passionately and perceptively, on Dylan’s major artistic accomplishments as a performer, dating back to the beginning of his career right up through the 2001 album “Love and Theft.” Muir has attended over 200 concerts, most of them on the NET, and he faithfully records his impressions crisscrossing international borders in pursuit of the next great (and sometimes not so great) live experience. My book will have a much narrower focus, spotlighting concerts in a single locale for an extremely specific, yet highly representative, case study of Dylan in performance.

On a personal level, this project is a love letter with two recipients: the artist who has meant the most in my life, and the city where I’ve worked, played, and raised a family. But this project is not simply the personal memoir of an overgrown fanboy laying gifts at the feet of his rock idol, nor is it a brochure for the Cincinnati Chamber of Commerce hyping the virtues of the “Queen City of the West.” I aim to study Dylan as a performing artist in multiple contexts, considering what individual concerts tell us about Dylan’s ever shifting art and career, and grounding each performance in time and place as an event in the civic life of Cincinnati.

In Martin Scorsese’s documentary No Direction Home, Dylan declares, “The ideal performances of the songs occurred on the stages of the world. Very few of them could be found on my records. Reaching the audience: that’s what it’s all about.” Those performances did not take place in a vacuum. One of the central premises of Dylan in Cincinnati is that when and where a concert takes place matters. The performer and the audience may only be dimly aware of these factors at the moment, if at all. In retrospect, however, our appreciation of Dylan’s art is greatly enriched by placing his achievements in historical, cultural, political, aesthetic, and geographic contexts.

What do Dylan’s shows mean to the cities where he plays? When he first landed in Cincinnati in 1965, like an alien from another planet, what were the conditions on the ground and how did that determine his effect on audiences and the community? How did his songs come across differently in 1981 than 2001 or 2021, as Dylan, his audiences, and the city continued to change? We can gain a fresh perspective on Dylan’s work by reconsidering it in light of such questions. I think of this approach as “Regional Dylan.” My contribution to the field is Dylan in Cincinnati, but there could and should be similar studies focused on various cities around the world. I won’t be the one to write those other books, but I hope someone will.

Why Cincinnati? In the galaxy of Dylan, what makes Cincinnati special? My first answer is, well, nothing much—and that’s precisely the point. The city’s seeming lack of distinction in the Dylan cosmos is a big part of my attraction to this project. When one thinks of Dylan in performance, one immediately thinks of his breakthrough in the bars and coffeehouses of Greenwich Village, or his rise and fall at the Newport Folk Festival, or the tempestuous tours of England in 1965 and 1966, or the Rolling Thunder Revue’s wild caravan a decade later. The epicenters of his musical earthquakes tend to be metropolises like New York, London, San Francisco, Tokyo, etc. But Dylan has played thousands of shows over his sixty-plus year career. Most nights were not legendary and have not entered the lore.

“He is so out there, and I don’t mean that in the vernacular sense. He is so out there in the territories,” observes Greil Marcus. “You land in any spot and there is a reasonable chance that Dylan will be playing in that town that night.” Almost all of Dylan’s concerts have been documented through bootleg recordings, and a high percentage of them are noteworthy—some transcendently so—even if relatively few listeners have bothered to take note and give them the scrutiny they deserve. We may think we know the Dylan narrative writ large, but there’s another story to be told about the small-scale intimate experiences of individual shows. Of course, there are also plenty of performances better left forgotten, but that’s part of the story, too. Dylan is a working musician plying his trade on the road, navigating the vicissitudes of an impossibly long career as a troubadour. Sometimes he sounds like he’s just punching the clock and trying to get back to the bus—and sometimes he blasts off like a rocket into the heavens. His best live performances have too often gone unnoticed except for the lucky fans who were there in that place on that night, and for bootleggers who vicariously experience the shows after the fact.

During the pandemic, while listening to a bootleg of Dylan’s gorgeous Beacon Theatre concert from November 21, 2021, I blasphemously wondered: why doesn’t he play every show in New York? He sure does bring his A-game when the spotlight shines brightest and he’s surrounded by his most celebrated followers. Why bother playing so many concerts in flyover states, middling villages, and dodgy dancehalls scattered across the globe? He certainly doesn’t need more money or fame, and it can’t be particularly good for his physical health or personal relationships. One possible explanation is the time-tested tradition of taking a play or musical on the road for a tryout in the provinces, working out the kinks in preparation for the big show on Broadway or the West End. Maybe that’s the answer, but I don’t really think so.

No community wants to be relegated to the role of understudy audience, and I reject the notion that Dylan’s concerts in Cincinnati or a thousand other comparable towns were mere warmups for the shows that truly mattered before his favorite fans. I cannot imagine Dylan approaching concerts this way. Surely he doesn’t pace backstage thinking, “Let’s give ’em 70% tonight and save the best stuff for Royal Albert Hall.” No, I give him the benefit of the doubt that he tries to bring his A-game most nights, even at B-list venues in C-town. The evidence is there for anyone to hear in the recordings. Bootlegs provide ample proof that many of Dylan’s greatest performances come out of nowhere. At bottom, Dylan is a Nowhere Man from Nowhere Land. The kid in him from Hibbing knows that those anonymous audiences in their invisible republics deserve to hear great music, too. He has committed his life to delivering the goods, night after night, year after year, on the stages of your town and mine.

My study is titled Dylan in Cincinnati, but I recognize that many readers will care a lot more about one of those subjects than the other. I write with two audiences always in mind: 1) readers with local ties to Cincinnati who attended some of these shows and want to relive the experience from a fellow fan’s perspective; and 2) readers who know very little about Cincinnati but who care deeply about Dylan as a live performer. I think both groups stand to learn a lot about each other, and I suspect we’re all curious to see what emerges from a longitudinal study of a mercurial artist over a span of nearly fifty years playing regularly in a single city. Like all river towns, Cincinnati depends upon sturdy, reliable bridges. My aim throughout this study is to build a bridge connecting the world of Dylan to the world of Cincinnati.

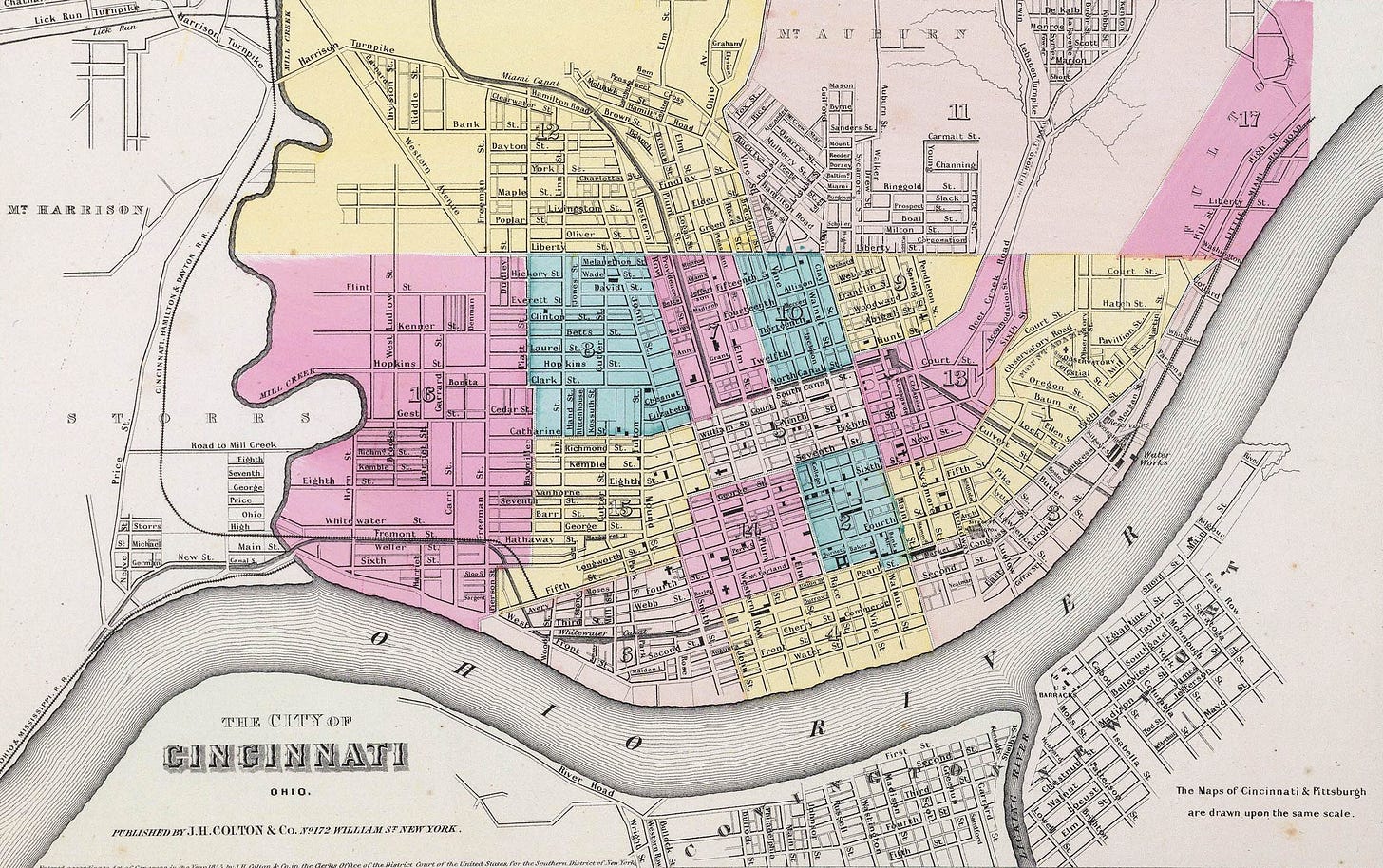

Historical Cincinnati

In this introduction I want to lay the foundations of that bridge by establishing Cincinnati’s historical and musical significance prior to Dylan’s arrival on the scene. For centuries, time out of mind, the area known today as Cincinnati was home to hunters and gatherers who spoke the Algonquin language, members of the Shawnee, the Lenape, the Ojibwa, and the Miami tribes. After the Revolutionary War, as citizens of the new country began to move westward and claim new land, white settlers arrived in the region, attracted by the fertile basin of the Little Miami Valley and its strategically advantageous location along a major waterway, the Ohio River. In 1788 these settlers founded Losantiville. A year later Fort Washington (named after the newly elected first President of the United States, George Washington) was constructed to defend white claims against Native Americans who resisted this incursion (cf. Dylan’s “With God on Our Side”). On January 4, 1790, the governor of the Northwest Territories, Arthur St. Clair, officially rechristened the settlement as Cincinnati. He named it after a group he headed called the Society of Cincinnatus, a relief organization for Revolutionary War veterans.

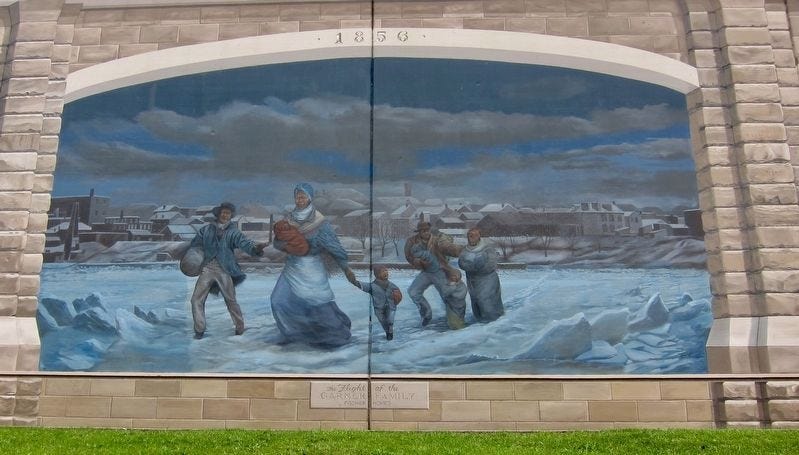

Cincinnati’s prime spot on the Ohio River allowed for rapid expansion during the 19th century as an active trade center. Its location also meant that Cincinnati had a major stake in the country’s political, economic, and moral crisis over slavery. In 1787 the U.S. Congress passed the Northwest Ordinance, banning slavery in territories north of the Ohio River. When Ohio was officially granted statehood in 1802, it entered the union as a free state. A decade earlier Ohio’s neighbor to the south, Kentucky, had already been admitted as a slave state. As the border between Ohio and Kentucky, the Ohio River constituted a threshold between freedom and slavery in the decades leading up to the U.S. Civil War (1860-1865).

Cincinnati’s status as a free city directly across the river from a slave state made it a major hub for runaway slaves on the Underground Railroad: a metaphorical term for the clandestine network aimed at helping slaves escape captivity in the south and seek freedom in the north. Today the city commemorates this legacy at the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center, located in downtown Cincinnati on the historic northern bank of the Ohio River. The city’s pivotal role with respect to fugitive slaves and the flight to freedom is also memorialized in classic American literature, most notably Uncle Tom’s Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stowe (a novel inspired by her observations as a resident of Cincinnati) and Beloved by Toni Morrison (a novel set in Cincinnati and northern Kentucky and written by the Nobel laureate from Lorraine, Ohio).

As a student of history, Bob Dylan recognizes 19th-century Cincinnati as a bellwether for the Civil War. According to his memoir Chronicles, after moving to New York in 1961, young Dylan made trips to the New York Public Library to read newspaper accounts from the Civil War era, including articles from the Cincinnati Enquirer (84). He traced the racial animosity building toward violent conflict in several key cities: “Anti-slave labor advocates inflaming crowds in Cincinnati, Buffalo and Cleveland, that if the Southern states are allowed to rule, the Northern factory owners would then be forced to use slaves as free laborers” (85). Chronicles is as much coming-of-age fiction as it is factually accurate autobiography; but whether the young college dropout really gave himself a crash course in American history at the NYPL, or whether the older chronicler did the homework for him, Dylan gets his story more or less right.

A vocal faction of white workers increasingly feared that abolition would result in an erosion of job security. Cincinnati’s cauldron of resentment, anger, and paranoia periodically boiled over into race riots in 1829, 1836, 1841, and 1862. Dylan claims he read all about it in the pages of the Cincinnati Enquirer. The newspaper was identified politically with the Democratic Party in its early years. Although its editors and journalists were not explicitly pro-slavery, they did mirror and foment anxieties over abolition from their largely white working-class readership. In his book on the history of the newspaper, Graydon DeCamp explains:

The mainstays of the party were the Irish, the predominantly Catholic Germans, and mountain Southerners who had migrated north to jobs on the river and the city. These groups had a keen economic interest in the health of river commerce, since many of them earned their wages as warehousemen, boatmen, and wharf-hands, or in shops and factories dependent upon river trade. One thing they were against was abolition. They feared that freed slaves would migrate northwards and take their jobs. (37)

The political, social, and racial tensions Dylan found in the 1860s Cincinnati Enquirer read like harbingers for his own 1960s America. “It all makes you feel creepy. The age that I was living in didn’t resemble this age, but yet it did in some mysterious and traditional way. Not just a little bit, but a lot,” Dylan wrote in Chronicles. “Back there, America was put on the cross, died and was resurrected. […] The godawful truth of that would be the all-encompassing template behind everything that I would write” (86).

The winds of change shifted directions after the Civil War, as the state of Ohio and the city of Cincinnati transformed into Republican strongholds. In the sixty years following the war, nine Republicans were elected President of the United States, and seven of them hailed from Ohio. Cincinnatian William Howard Taft holds the distinction as the only man to have served as both President and Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. The Taft family is Cincinnati royalty, with the Taft name embossed all over town on street signs, museums, taverns, and theaters. By the mid-20th century the Cincinnati Enquirer had evolved to reflect the region’s Republican ethos. This position was solidified by Roger Ferger, who became the paper’s publisher near the end of World War II and established the Enquirer as the leading conservative voice of Cincinnati. Ferger presided over the paper until 1965, the same year as Dylan’s first concerts in the city. This conservative context will prove crucial in the next installment to understanding skeptical reactions to Dylan in the community and in the local press. He played his first show here on March 12, 1965, at the Taft Theatre—yes, named after that same Taft family.

Musical Cincinnati

Another context useful for appreciating Dylan in Cincinnati is the city’s rich musical tradition. The story of Cincinnati popular music is tightly intertwined with the Great Migration. Between roughly 1910 and 1970, around six million African Americans migrated north, fleeing racist terrorism, discriminatory Jim Crow laws, and an exploitative agrarian economy that condemned sharecroppers to subsistence-level living conditions and generational poverty. Like many cities outside the South, Cincinnati experienced a major demographic shift during this period. According to census statistics, the African American population of Cincinnati in 1910 was 14,482, accounting for 4.4% of the city’s total population. By 1950, the number of African American Cincinnatians had grown to 78,685, representing 15.6% of the total population (Bunch-Lyons 15). At the same time, a large number of white Appalachian natives were leaving their rural homes to seek greater economic opportunities in urban industrial areas, particularly in the Midwest. Cincinnati became a crossroads where these two major migrations converged, and this commingling was represented in the city’s flourishing music scene.

No institution represents this intercultural exchange better than King Records. When Dylan played at the Aronoff Center in 2021, he acknowledged the city’s most important musical legacy, telling the audience, “Nice to be here in Cincinnati, home of King Records—one of the best labels ever really.” King was founded by Syd Nathan in 1943 and quickly grew into a major independent label recording an eclectic lineup of artists. In King of the Queen City: The Story of King Records, Jon Hartley Fox notes,

King Records was all about ‘American music.’ King was the most important record company in the United States in the years between 1945 and 1960. […] King was active in virtually all genres of vernacular American music, recording musicians and styles overlooked by the larger labels, making records for ‘the little man,’ as Syd Nathan often put it. (Fox xv)

For a glimpse of the diversity and immense talent assembled at King, consider this remarkable cross-section of styles and artists:

When it came to the music of ‘the little man,’ King had it covered: there was ‘jump blues’ with Wynonie Harris, Roy Brown, and Bull Moose Jackson; country with Moon Mullican, the Delmore Brothers, and Grandpa Jones; blues with Freddie King, Lonnie Johnson, and Albert King; bluegrass with the Stanley Brothers and Reno & Smiley; black gospel music with the Swan Silvertones and the Spirit of Memphis Quartet; R&B with Billy Ward and the Dominoes, the 5 Royales, and Hank Ballard and the Midnighters; rockabilly with Charlie Feathers and Mac Curtis; and proto-soul music with Little Willie John and James Brown. (Fox xv)

With its combination of blues, gospel, R&B, and soul on the one hand, and country and bluegrass on the other, King Records effectively represented the soundtrack for the Great Migration. The lion’s share of credit for King’s success goes to Syd Nathan. His creative vision for a label that encompassed the full range of American music had democratic appeal, and his progressive policy of fully integrating the workplace was unusual for mid-century Cincinnati and was ahead of its time in the music business.

Dylan’s shout-out saluting King Records was no mere pleasantry. He was deeply influenced by King’s music and musicians. For instance, during his 1980 residency at The Warfield in San Francisco, he told a story on stage about his early exposure to soul music and then launched into a scintillating rendition of Little Willie John’s “Fever,” originally recorded March 1, 1956, at King Studios. In Dylan’s 1985 interview with Mikal Gilmore, he enthusiastically praised two other King artists, Alton and Rabon Delmore: “The Delmore Brothers—God, I really love them. I think they’ve influenced every harmony I’ve ever tried to sing” (Gilmore 885). Over the years Dylan has covered multiple songs and artists associated with King, and he included many of the label’s records on his Theme Time Radio Hour.

For an admittedly obscure but nevertheless revealing sample of his Cincinnati musical tastes, consider the jam session at London’s Savoy Hotel on May 4, 1965. Dylan sat around his room that night trading tunes with Joan Baez and Bobby Neuwirth (an Ohio native), and brief excerpts appear in D. A. Pennebaker’s groundbreaking documentary Dont Look Back. The full impromptu session included ten songs, a number with connections to Cincinnati. They sang “Blues Stay Away from Me,” the Delmore Brothers’ hit composed and recorded in Cincinnati in 1949 (Barker 43-44). Dylan would later record the song with Doug Sahm in 1972, and he played it live with Levon Helm and Rick Danko at the Lone Star Café in 1983. The Savoy singalong also includes “Remember Me (When the Candlelights Are Gleamin’).” Scott Wiseman reported that he wrote this song in 1939 while he and his duet partner Lulu Belle were working at WLW radio station in Cincinnati (see Helfret). Dylan, Baez, and Neuwirth harmonized on two favorites from Hank Williams, “Lost Highway” and “I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry.” The latter song was recorded at Herzog Studio on Race Street in downtown Cincinnati on December 22, 1948 (see Bird). The Savoy Hotel hootenanny concluded with the lovely Scottish and Irish folk song “Wild Mountain Thyme.” Although 23-year-old Dylan could not have known it at the time, his 47-year-old future self would sing this song publicly for the last time at Cincinnati’s Riverbend Music Center on June 22, 1988. No crystal balls are needed to detect that by May 1965—two months after his solo acoustic performance at Taft Theatre and six months before his acoustic/electric show at Music Hall—Cincinnati had already made a formative impact on Dylan’s music.

Recorded Live

Along with grounding my study of Dylan in a regional context, I also want to consider more performance-based contexts for thinking about his concerts. We are all familiar with the idea of something being “recorded live.” I heard variations of this phrase throughout childhood on TV: “All in the Family was filmed before a live studio audience.” This concept extends to cover the phenomenon of live albums, such as Dylan’s Real Live or the box set The 1966 Live Recordings. However, as Philip Auslander points out in his book Liveness: Performance in a Mediatized Culture, “recorded live” is actually an oxymoron: if it is recorded, then strictly speaking it is not (or is no longer) live. Nevertheless, terms like “recorded live” or “live recording” are still useful for capturing how listeners respond to concert recordings, as distinct from studio recordings. Auslander parses it out this way:

In the case of live recordings, the audience shares neither a temporal frame nor a physical location with the performers, but experiences the performance later and usually in a different place than it first occurred. The liveness of the experience of listening to or watching the recording is primarily affective: live recordings allow the listener a sense of participating in a specific performance and a vicarious relationship to the audience for that performance not accessible through studio productions. (60)

In the specific world of Dylan, and in the broader field of performance studies, the relationship between live performance and recorded performance is highly ambivalent and contested. To put it plainly, sometimes recordings and live performances complement each other, and sometimes they are pitted against each other as rivals or adversaries. Many times over the course of Dylan in Cincinnati I will yank the rope in this ongoing tug-o’-war, but for now I just want to establish how and why this contest matters when considering Dylan in performance.

A revealing battle in this conflict is Lee Marshall’s squabble with Michael Gray. In his chapter on the Never Ending Tour from his book The Never Ending Star, Marshall describes his approach to Dylan in performance as “NET consciousness,” which he defines in opposition to the “recording consciousness” of Gray.

For the benefit of the uninitiated, I should point out that Michael Gray was one of the first serious Dylan critics and he remains one of the most accomplished. He has been an eloquent champion of Dylan’s formidable art for decades, but he doesn’t pull punches when he finds Dylan falling short of those lofty standards. In his magnum opus Song & Dance Man III, Gray grouses over Dylan’s decline as a performer. Responding to a subpar “Desolation Row” at the 1990 Montreal concert, the eminent Dylanologist complains:

He always cuts out verses from long songs these days. There is no reason for this, beyond the sheer shrugging-off of the task of the full performance. There you are, say, at the concert in Montreal in May 1990; Dylan launches into ‘Desolation Row,’ which is fresh—having been performed only five times in the previous two decades; and he misses out five verses. How can this not disappoint? Such short-changing of the audience, such short-changing of his own work, is in essence another expression of self-contempt. (855)

Marshall regards Gray’s critique as emblematic of a values system he rejects. As Marshall sees it, Gray privileges fidelity to the past “text” (in this case, the 1965 recording of “Desolation Row” that closed Highway 61 Revisited) over fidelity to the live re-creation of the song in the present. “Gray’s view that Dylan ‘misses out’ five verses depends upon a fixed idea of the work to which the performer is expected to adhere,” summarizes Marshall (213). He continues, “In referring to a short-changing of the work itself, Gray accuses Dylan of treating his own work disrespectfully. I don’t think this is true; it seems to me that Dylan is incredibly respectful of his (and others’) songs” (214). He insists, rightly I think, that “respect is manifested by not treating them as too precious to touch” (215). Marshall magnifies this quibble with Gray into a much larger counterargument about how best to approach Dylan in performance: “When Gray rhetorically asks ‘how can this not disappoint?’ he fundamentally misunderstands the ethos of the NET and, I think, misjudges the experiences of Dylan’s new audience. The chief effect of attending multiple shows is a reconfiguration of how one hears a text, facilitating what I might as well call a ‘NET consciousness’ in place of a recording consciousness” (215).

So far, so good. I agree with Marshall that Dylan is committed to reinventing his songs in performance and that audiences should be open to these new reinventions rather than constantly measuring them against the old recordings and finding them lacking. However, Marshall then takes it a step further: “In the moment of performance, in the act of listening, NET consciousness undermines any awareness of alternative versions of the text. If ‘Mr. Tambourine Man’ has two verses tonight, or three, then that’s what ‘Mr. Tambourine Man is tonight—you hear the performance in front of you and not absent others” (215).

Yeah, but can you ever really do that? Marshall offers a valid critique of listeners and critics who cling too possessively to the “definitive text” of a song (not that Gray uses that term himself) and who hold it against Dylan when he fails to reproduce this ideal version on stage. That said, how can a Dylan fan not have a baseline of previous versions of “Desolation Row” and “Mr. Tambourine Man” in mind when hearing his latest rendition? You don’t necessarily have to be mentally ranking them in order of superiority, and you can certainly embrace difference without branding one as good and the others as bad. But I can’t entirely share Marshall’s “NET consciousness” if it entails wiping my memory clean like an Etch A Sketch for every performance, as if hearing the song for the first time. Dylan in performance functions more like a palimpsest for me than a tabula rasa.

I identify more closely with the experience Matthew Ingate describes in Together through Life: My Never Ending Tour with Bob Dylan. Ingate takes a layered approach to Dylan in performance, as distinct from Gray’s preference for classic recordings or Marshall’s preference for ignoring everything but the performance unfolding each night live on stage. As an audience member, Ingate responds to the palpable presence of multiple Dylans in concert, young and old, then and now. His first concert was in 2011, when he was 17 and Dylan was 70. However, Dylan still summoned up earlier incarnations through his performance:

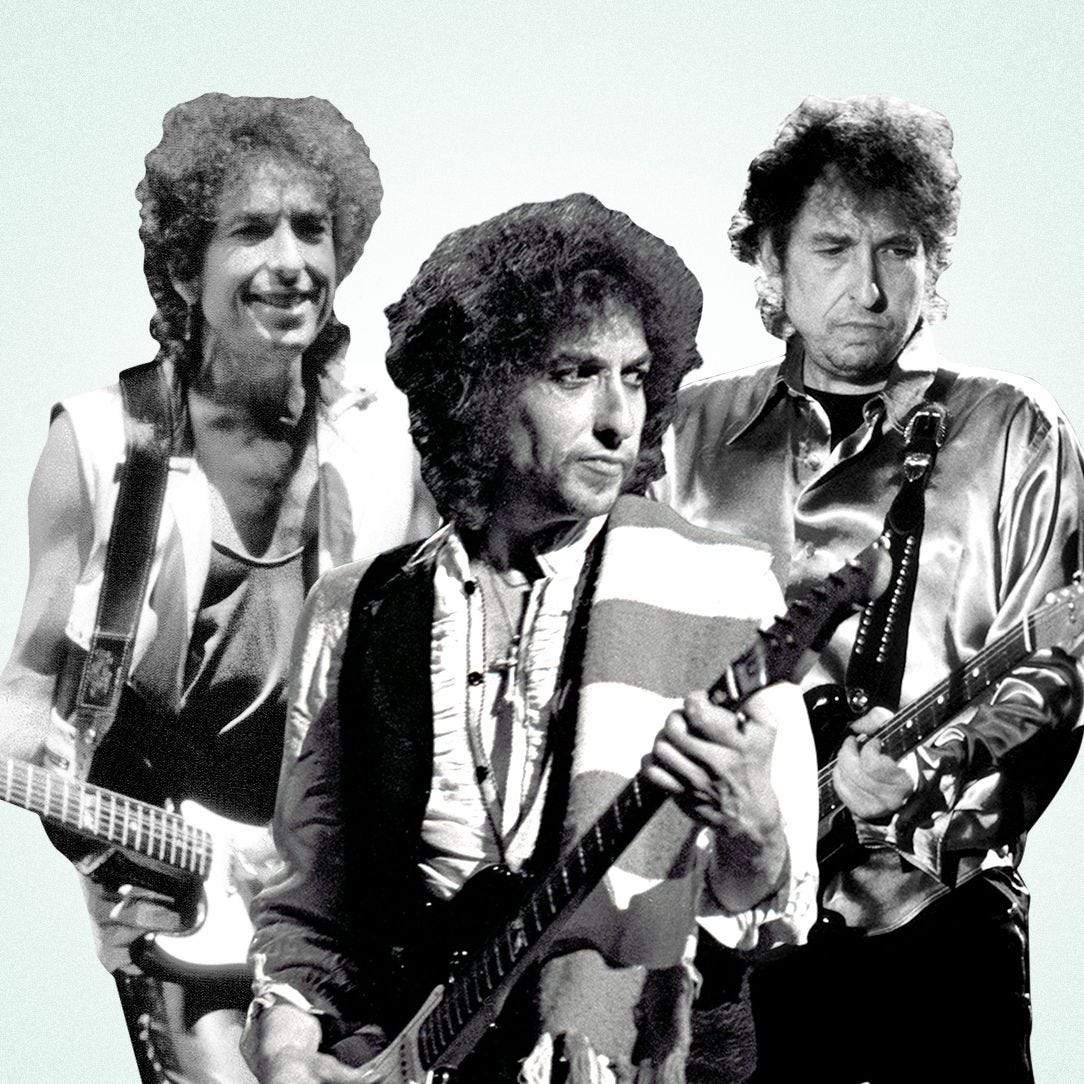

Standing in front of me is 70-year-old Bob Dylan. Wandering outlaw troubadour; pencil tache, bolo tie and all. Standing in front of me is 35-year-old Bob Dylan in white face and flower-decked hat. Standing in front of me is 22-year-old Bob Dylan, youthful, smiling and bouncing as he overflows with energy for the music and words that can’t stop bursting out of him. Standing in front of me is every Bob Dylan that has been and all those that are yet, somehow, miraculously, still to come. (xiii-xiv)

Ingate’s reaction reminds me of the video to “Thunder on the Mountain.”

The video is a montage of older Dylan performances assembled in such a way that the beats and rhythms on screen match up uncannily with the new song. The effect is to make it look like those previous Dylans are playing as backup band for the latest Dylan, returning from the past to support—or haunt—his new creation.

The field of performance studies has a lot to teach us about Dylan. For example, the phenomenon Ingate describes as multiple Dylans resonates well with Marvin Carlson’s theories of “ghosting.” In an online or social media context, this term refers to an abrupt absence and silence; but in a performance context “ghosting” refers to lingering presences that persist and refuse to go away. In his influential book The Haunted Stage: The Theatre as Memory Machine, Carlson examines various ways in which past associations with plays, performers, and spaces can affect an audience’s response to present performances. This work seems relevant for understanding how Dylan’s live performances in his later years conjure up ghosts of his former selves, instigating a kind of self-dialogue with his own songs and personae.

If this is true on Dylan’s side of the footlights, it is equally true on our side. Carlson explains, “The recycled body of an actor, already a complex bearer of semiotic messages, will almost inevitably in a new role evoke the ghost or ghosts of previous roles if they have made any impression whatever on the audience, a phenomenon that often colors and indeed may dominate the reception process” (8). Dylan often seems uneasy with this sort of spectral conjuring, but he cannot prevent it and is limited in his ability to control it. As Carlson observes, “Even when an actor strives to vary his roles, he is, especially as his reputation grows, entrapped by the memories of his public, so that each new appearance requires a renegotiation with those memories” (9). In the song “High Water (For Charley Patton),” Dylan alludes to this burden of renegotiation, which must feel at times like a doomed competition against his own ghosts: “As great as you are, man / You’ll never be greater than yourself.” This “ghost in the (memory) machine” effect also helps explain why some fans respond so negatively to Dylan’s re-imagination of his old classics in concert. Considering this tension in Why Bob Dylan Matters, Richard F. Thomas posits,

In all of these cases there was something at stake, something to do with memory, song, and shared human emotions and the joy, sorrow, or pain that is involved in listening to Bob Dylan. […] The music of our youth in particular stays with us. When it changes too much in performance, the singer may be doing things to those memories. (289)

These nightly renegotiations between the performer, the audience, and their competing memories don’t always have to be contentious and burdensome. Ghosting also intensifies the thrill of seeing a great performer live. According to Carlson, “One of the most powerful and positive experiences in the theatre arises from seeing a series of creations by those great actors in every theatre generation who in addition to creating memorable roles gradually take on a special aura of achievement” (92). Carlson is thinking primarily of actors like David Garrick in the 18th century, or Sarah Bernhardt and Eleanora Duse in the 19th century, or John Gielgud, Ralph Richardson, and Laurence Olivier in the 20th century. But he might just as well be talking about the stage performer Bob Dylan in the 21st century when he observes:

Once such actors have established themselves at the pinnacle of their profession, their appearance in each new role, or in each major revival, is ghosted not only by memories of specific past performances but, perhaps even more important, by a general audience awareness of the significance of the achievement represented by those performances. (92)

The last couple times I saw Dylan perform I felt the ghosting effect Carlson describes. I sensed that others in the audience did, too. We all converged at a common point in space and time and were bound by a common devotion. We were there to hear great live music, sure, but we were also there to honor the legacy of that music’s creator and animator. There was a prevailing communal spirit of shared gratitude and admiration for what Dylan was giving us on that particular night but also for what he had already given us on so many previous nights. We will not see and hear Dylan’s like again. Our awareness of the ghosts behind Dylan alters our response to the performance in front of us.

I suppose there was a time when attending a Dylan concert could simply be a groovy way to spend an evening. But these days it feels like much more than that. We’re there to party but also to pay our respects. I’m not suggesting a funereal atmosphere, but I am suggesting an event that is about more than entertainment. Dylan’s 2020 album Rough and Rowdy Ways is filled with intimations of mortality and immortality, and it is hard not to ponder death—including Dylan’s own death—when song after song on the RARW tour ruminates on the subject. The ghosting of Dylan doesn’t just work backwards in time: it also looks ahead to a day in the not too distant future when he will cease to perform.

This foreknowledge may have been at the back of Laura Tenschert’s mind when she flew from London to attend Dylan’s final show of the 2021 fall tour in Washington, D.C. In her podcast about the trip and concert, she candidly reflects,

This is the weird thing, and the stuff that’s kind of hard to talk about, when you’re doing something like traveling really far for a concert and a lot of people are rooting for you. I felt like a sudden pressure to be enjoying myself, to be in this moment and just fully be there, and just be happy and enthusiastic. But at the same time, you know, I really was just arriving. It took me maybe a song or two to fully realize that I was actually there, and I was experiencing this—and Bob Dylan was right there.

The pressure she captures so effectively here is twofold. There is first a sense of responsibility to be awake and receptive to the work, to be fully in the moment and in the room with these songs—the same challenge Dylan sets for himself on stage. As someone who writes about Dylan, however, there is another sense of responsibility. We feel an obligation, to our contemporary readers and to posterity, to document faithfully what happened, to grope for words that accurately communicate the visceral experience of the performance, to consider how these effects might have been achieved, and to make a case for why it all matters. We do this because we love it, but also because we know that we are the last generation blessed with the opportunity to see Dylan perform live.

Bootlegs

Thankfully, future generations can still listen to the bootlegs. But that opens up another major front in the contested terrain of Dylan in performance. Dylan in Cincinnati would not have been possible without the ready availability of bootlegs: those unapproved, non-copyrighted, freely traded recordings made surreptitiously by dedicated, rule-breaking, resourceful, largely anonymous but utterly indispensable fans determined to liberate Dylan’s live performances and share them with the world. All hail the bootleggers! I can honestly say that I have not paid a single penny for any of the rare and unreleased live recordings used for this project, and neither should any of my readers. Back in the early days of bootlegging, small fortunes were doubtlessly made selling illicit albums and tapes, but those days are pretty much over. Now digital files are routinely swapped gratis by fans through websites without any money changing hands and without any financial profit. Indeed, the premier internet forum on Dylan, Expecting Rain, strictly forbids the sale of the thousands of concert recordings it freely advertises.

Clinton Heylin traces the development of this underground industry in The Great White Wonders: A History of Rock Bootlegs. He understands the renegade proletarian appeal of bootlegs, but he also offers an aesthetic defense of the practice. “I believe bootlegs have been a positive influence on the music,” Heylin affirms.

They have reminded fans that rock & roll is about ‘the moment,’ that you might have to wade through static, pops, crackles, bad nights and worse tapes to find one clear moment, but no record company can capture each and every one worth preserving; that the record companies cannot lock music up in neat little boxes and say ‘This is what you may listen to.’ (4)

Heylin adds, “Hopefully the bootleggers have also freed an awful lot of music that the artists themselves might not have ‘approved’ for release” (4). That last point deserves emphasizing. It is not only the big bad moguls who forbid bootlegs in a nefarious effort to dictate the public’s musical tastes and exercise a monopoly over music profits. Many artists are also opposed to bootlegs on artistic principle—and according to Lenny Kaye, they are dead wrong.

Kaye is best known as a member of the Patti Smith Group, so you might expect this musician to be skeptical of bootleggers who distribute music illegally without permission from or royalties for the artist. However, Kaye makes a compelling case that bootlegs provide a crucial check on artists’ tendencies to be too protective of their music. Kaye told Heylin:

‘I think that bootlegs keep the flame of the music alive by keeping it out of not only the industry’s conception of the artist, but also the artist’s conception of the artist. I think a lot of artists would like to keep the scruffy moments away. There’s that self-editing thing and, with all due respect to great artists, a lot of times their own instincts aren’t as righteous about the music as someone else.’ (Heylin 392)

Kaye even used Dylan, the most bootlegged artist in music history, as an ideal example: “‘I’d rather have a lot of scattered stuff so that someday, maybe even in fifty years, someone will be looking at the work of, say, Bob Dylan and all of a sudden hear something that might have been lost forever had somebody not grabbed it somewhere and put it out’” (Heylin 392). Those are exactly the kind of spontaneous, non-curated moments I document throughout Dylan in Cincinnati.

The most outspoken defender of bootlegs among Dylanologists was Paul Williams—the best writer on Dylan in performance who ever lived.

In the first volume of his Performing Artist series, he vindicated bootlegs as an integral component to any study of Dylan in performance:

One of my purposes in writing this book is to help legitimize a conceptual view of rock and roll implicit in the activities and enthusiasms of collectors of performance tapes and studio outtakes […]: the view that each performance by an artist is potentially of interest, that our attention need not be limited to the sum of the artist’s output as measured in songs or record albums. (175)

If every performance potentially contains something significant, deserving of comment, and worth preserving—and I agree with Williams that it does—then the only way a writer can do justice to performance criticism (short of attending every single concert and possessing the power of total recall) is by listening to bootlegs. As Williams puts it in his second volume, “without the crutch of taped recordings there are significant barriers to writing critically, or anyway intelligently, or in depth, about specific works of performed art” (292).

Granted, listening to a recording is not the same as being there live and experiencing a concert in the moment. Nevertheless, bootlegs are what endure as the lasting artifacts of Dylan in performance, and therefore they must be produced, disseminated, consulted, preserved, and cherished. In his most rousing bootleg manifesto, Williams proclaims:

I’m listening to tapes, you see, and not because they give me a chance to remember what I loved in the performances; rather, they are the performances, for better or worse—like the score for Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony, they are what survives. This book is not really about history at all. It’s about music/art that is in existence now, a body of work that survives the touring and the amphitheaters and the dreams and ambitions and intentions and obstacles of that particular moment in the performer’s life. This body of work, these tapes, are not equivalent to the live performances—but they are what we have, to listen to, to talk about, and it is my firm conviction and primary argument that, imperfect as they are, they are worthwhile. Indeed, they are something more than that; they are works of performed art. They stand on their own. They offer direct (and continuing) access to the mystery. (295)

Amen, brother! Today, any day, anyone reading this passage can experience (or re-experience) almost any Bob Dylan concert right now, as if for the first time, thanks to the existence of bootleg recordings. Simply pause your reading of this page, go to Expecting Rain, download the concert of your choice, clear two hours in your schedule, pop in your earbuds, and access the mystery.

Williams touts the symbiosis between concerts and bootlegs, but not everyone has such rosy regard for the relationship. Many critics in performance studies see recordings as the antithesis of live performance. For instance, according to Peggy Phelan, “Performance honors the idea that a limited number of people in a specific time/space frame can have an experience of value which leaves no visible trace afterward” (149). Phelan throws down the gauntlet against recording:

Performance cannot be saved, recorded, documented, or otherwise participate in the circulation of representations of representations: once it does so, it becomes something other than performance. To the degree that performance attempts to enter the economy of reproduction, it betrays and lessens the promise of its own ontology. (146)

Viewed from this perspective, a bootleg is less like the score of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony and more like an autopsy report. This policy strikes me as too stringently doctrinaire, and Dylan never fares well with purists.

I find Walter Benjamin’s approach to reproduction more amenable. He predated bootlegs, but something tells me he would have been a fan. In his seminal 1935 essay “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” Benjamin noted that previous eras placed primary value in the aura of artworks: the unreproducible authenticity of a unique work fixed in time and place. However, during the modern mechanical age, the traditional aura of singular artworks was challenged and displaced by mass reproductions of artworks through photography and film, and we could later add bootleg recordings to the list. Benjamin recognized that mass reproduction flies in the face of tradition—and he approved of that transgression. As he put it,

that which withers in the age of mechanical reproduction is the aura of the work of art. This is a symptomatic process whose significance points beyond the realm of art. One might generalize by saying: the technique of reproduction detaches the reproduced object from the domain of tradition. By making many reproductions it substitutes a plurality of copies for a unique existence. And in permitting the reproduction to meet the beholder or listener in his own particular situation, it reactivates the object reproduced. (221)

I recognize my experience with bootlegs in Benjamin’s description. Rather than feeling as if I’m encountering a pale reproduction that is completely inferior to the real concert, or as if I’m violating the sacrosanct aura of the authentic thing itself, I feel instead like the bootleg meets me, the listener, in my “own particular situation” and “reactivates” the concert by means of reproduction (a copy of a copy of a copy). Benjamin gets it. He understands and validates the audience’s impulse to engage with art that would otherwise be inaccessible by means of mechanical (now digital) reproduction. This desire is not a symptom of the listener’s bad taste, accepting a cheap knock-off in place of the original. Rather, listening to bootlegs is motivated by a desire for intimacy, for a closer connection than would otherwise be possible to a work of art distant in time and/or place. In one of my favorite passages from the essay, Benjamin recognizes

the desire of contemporary masses to bring things ‘closer’ spatially and humanly, which is just as ardent as their bent toward overcoming the uniqueness of every reality by accepting its reproduction. Every day the urge grows stronger to get hold of an object at very close range by way of its likeness, its reproduction. (223)

The desire to bring things closer spatially and humanly—yes! That is precisely why we seek out bootlegs of Dylan concerts, find a time and place where we can concentrate, and click play: we want to get closer to that sound, to the creator, and to the moment of (re-)creation. I would never dismiss the magical power of hearing music live in concert. But I must admit that it’s often easier—not to mention a great deal cheaper—to cultivate conditions conducive to intimacy by listening to a bootleg at my kitchen table than by attending a concert at a crowded venue. The recording bridges the distance between the listener and the stage—a distance which, let’s face it, is largely determined by how much the listener is capable of spending for one of the best seats in the house.

Don’t get me wrong: the ritual of seeing and hearing Dylan in concert and basking in the aura of his presence is magnificent. I won’t give up making my pilgrimages to his shows for as long as he keeps playing. But reproductions of those performances are crucially important, too, and will become even more so after Dylan is no longer a live performer (or alive at all). Bootlegs aren’t poor substitutes for “the real thing,” and they’re definitely not blasphemies against liveness. Bootlegs provide a lasting lifeline to Dylan in performance. How does it feeeel? Listen to the recordings and judge for yourself. Susan Sontag was right in “Against Interpretation” when she described the best kind of art criticism: “What is important now is to recover our senses. We must learn to see more, to hear more, to feel more.” As she sums up it up, “In place of a hermeneutics we need an erotics of art” (14). Bootlegs are a circuit for conducting that current of intimacy connecting audiences to Dylan in performance.

In the introduction to the first volume of his Performing Artist series, Paul Williams succinctly describes his critical approach: “The best any of us can do is to tell the truth as we see, hear, and feel it.” He humbly adds, “Something else we can do is stay in touch with the joy and the wonder of it, and let that come through our reports. Wish me luck” (xii). I plan to follow this same approach in Dylan in Cincinnati. May my aim prove as true. Wish me luck! And keep an eye out for my next installment on Dylan’s first concerts in Cincinnati in 1965.

Works Cited

Auslander, Philip. Liveness: Performance in a Mediatized Culture, second edition. Routledge, 2008.

Barker, Derek. The Songs He Didn’t Write: Bob Dylan Under the Influence. Chrome Dreams, 2008.

Benjamin, Walter. “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” translated by Harry Zohn. Illuminations, edited by Hannah Arendt. Schocken, 1969.

Bird, Rick. “Herzog Is Hallowed Ground.” CityBeat (16 November 2009), https://www.citybeat.com/music/herzog-is-hallowed-ground-12177733.

Bunch-Lyons, Beverly A. Contested Terrain: African-American Women Migrate from the South to Cincinnati, 1900-1950. Routledge, 2002.

Carlson, Marvin. The Haunted Stage: The Theatre as Memory Machine. University of Michigan Press, 2001.

DeCamp, Graydon. The Grand Old Lady of Vine Street: A History of the Cincinnati Enquirer. Cincinnati Enquirer, 1991.

Dylan, Bob. Chronicles, Volume One. Simon & Schuster, 2004.

---. “High Water (For Charley Patton).” “Love and Theft.” Columbia, 2001.

Fox, Jon Hartley. King of the Queen City: The Story of King Records. University of Illinois Press, 2009.

Gilmore, Mikal. “Bob Dylan—After all these years in the spotlight the effusive star is at the crossroads again.” Los Angeles Herald Examiner (13 October 1985). Every Mind Polluting Word: Assorted Bob Dylan Utterances, edited by Artur Jarosinski, Don’t Ya Tell Henry, 2006.

Gray, Michael. Song & Dance Man III: The Art of Bob Dylan. Continuum, 1997.

Ingate, Matthew. Together through Life: My Never Ending Tour with Bob Dylan. Troubador, 2022.

Helfret, Manfred, Bob Dylan’s Musical Roots and Influences, http://bobdylanroots.com/remember.html.

Heylin, Clinton. The Great White Wonders: A History of Rock Bootlegs. Viking, 1994.

Marcus, Greil. “Greil Marcus and Don DeLillo Discuss Bob Dylan and Bucky Wunderlick (2005).” GreilMarcus.net (17 October 2014), https://greilmarcus.net/2014/10/17/greil-marcus-and-don-delillo-discuss-bob-dylan-and-bucky-wunderlick-2005/.

Marshall, Lee. Bob Dylan: The Never Ending Star. Polity, 2007.

Muir, Andrew. One More Night: Bob Dylan’s Never Ending Tour. Andrew Muir, 2013.

No Direction Home. Directed by Martin Scorsese. Paramount Pictures, 2005.

Phelan, Peggy. Unmarked: The Politics of Performance. Routledge, 1993.

Sontag, Susan. “Against Interpretation.” Against Interpretation and Other Essays. Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1966.

Tenschert, Laura. “I Flew to America to See Bob Dylan—Here Are My Thoughts!” Definitely Dylan (16 December 2021), https://www.definitelydylan.com/listen/2021/12/16/i-flew-to-america-to-see-bob-dylan-here-are-my-thoughts.

Thomas, Richard F. Why Bob Dylan Matters. Dey St., 2017.

Williams, Paul. Bob Dylan, Performing Artist, 1960-1973: The Early Years. Omnibus, 2004.

---. Bob Dylan, Performing Artist, 1974-1986: The Middle Years, Omnibus, 2004.

I'm very excited that you're sharing your work on Dylan in Cincinnati here on your Substack, because I think it's a project that gets to the heart of what Bob Dylan does – the mercurial nature of performance and the malleability of songs within it, bootleg culture, as well as Dylan's love for the non-coastal heartland and its role in music history. You're already hitting on this and much more in this wonderful introduction, and I'm excited to follow along on the journey!