Dylan's Holy Outlaws

I’m a religious person. I read the scriptures a lot, meditate and pray, light candles in church. I believe in damnation and salvation, as well as predestination. The Five Books of Moses, Pauline Epistles, Invocation of the Saints, all of it.

--Bob Dylan, 2022 Interview with Jeff Slate

In his recent Wall Street Journal interview, Bob Dylan reaffirms his religious beliefs and credits scripture for sustaining his faith. He makes a point of singling out foundational texts from both Judaism and Christianity: the five books of the Hebrew Bible, attributed to Moses, which make up the Torah; and the letters of Paul, establishing the New Testament framework for the Christian church. Dylan frequently makes scriptural allusions in his songs, but it is rare since the early 1980s for him to make such public and unequivocal testimony of his personal faith.

It may seem odd that an artist who self-identifies as deeply religious should also be perpetually attracted to outlaws. This recurring fascination is on full display in The Philosophy of Modern Song. However, Dylan finds no contradiction between the spirituality and the criminality of these compelling figures from songs and scriptures. Both kinds of characters play integral roles in the metaphysical drama of damnation, salvation, and predestination. Both bear family resemblances. “‘Fair and foul are near of kin / And fair needs foul’” as Crazy Jane puts it to the bishop in Yeats’s poem. A Joyce character makes a related point in Ulysses, describing Moses descending with the Ten Commandments from Mount Sinai, “bearing in his arms the tables of the law, graven in the language of the outlaw” (181).

In this post I want to consider Dylan’s intermingling of the religious and the criminal—the Holy Outlaw—in his chapters on three songs: “Jesse James,” “Pancho and Lefty,” and “El Paso.” Dylan interjects himself and his songs into these riffs and commentaries, but only through implication, deflection, and misdirection—the art of the unsaid.

I

Jesse leaves a wife

Will mourn all her life

The children that he left will pray

For Bob Ford the coward

That shot Mr. Howard

And laid Jesse James in his grave

Jesse was a man, a friend to the poor

Never see a man suffer pain

--Harry McClintock, “Jesse James”

“To live outside the law you must be honest,” reflects the imprisoned singer in “Absolutely Sweet Marie.” This is Dylan’s most succinct statement of the outlaw code. First as a folk singer and later as a songwriter, Dylan has contributed to the long tradition of romanticizing outlaws, depicting their exploits as righteous defiance of corrupt laws and institutions, and championing criminals as morally superior to those who would condemn, capture, and punish them. Chapter 10 focuses upon an ideal example of this tradition in Harry McClintock’s 1928 recording of “Jesse James.”

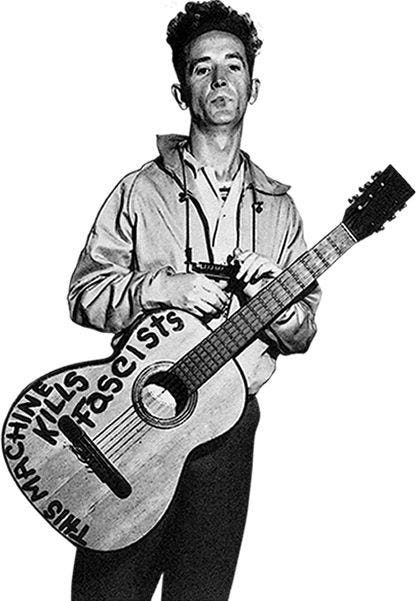

McClintock depicts Jesse and Frank James as Robin Hood figures, thieves who steal from the rich and give to the poor, striking blows against a rigged system that keeps wealth, power, and privilege unjustly concentrated in the hands of an elite few. As Woody Guthrie sang in his likeminded song “Pretty Boy Floyd,” “Some will rob you with a six-gun / And some with a fountain pen.” Dylan makes a similar distinction in his commentary: “Outlaws are different from common criminals. A common criminal can come in many guises. Criminals can wear badges, army uniforms, or even sit in the House of Representatives. They can be billionaires, corporate raiders or stockbroker analysts” (47). Given a choice between these two brands of criminal, common folk will side with the outlaw every time. As Guthrie memorably put it, “I love a good man outside the law just as much as I hate a bad man inside the law” (Guthrie & Santelli 134).

Guthrie found a kindred spirit in Jesus. The Jesus worshipped by Guthrie was the Holy Outlaw, the rebel rouser who defied both Roman and Jewish authorities, who hung out with social pariahs—tramps and thieves, lepers and crooks—a wanted man executed by the state to silence his dangerous message. Guthrie’s attraction to Jesus wasn’t just religious, it was political. In Bound for Glory, he has a character enlist Jesus as if he were a proto-socialist revolutionary:

“If Jesus Christ was sitting right here, right now, he’d say this very same damn thing. You just ask Jesus how the hell come a couple of thousand of us living out here in this jungle camp like a bunch of wild animals. You just ask Jesus how many millions of other folks are living the same way? Sharecroppers down South, big city people that work in factories and live like rats in the slimy slums. You know what Jesus’ll say back to you? He’ll tell you we all just mortally got to work together, build things together, fix up old things together, clean out old filth together, put up new building schools, and churches, banks and factories together, and own everything together. Sure, they’ll call it a bad ism. Jesus don’t care if you call is socialism or communism, or just me and you.” (251)

Dylan never mentions Guthrie or Jesus directly in his brief chapter on McClintock’s song. But you can damn well bet he knows that Guthrie lifted the tune and lyrical structure of “Jesse James” and refashioned it into his own Holy Outlaw song “Jesus Christ”:

He went to the preacher, he went to the sheriff

He told them all the same

“Sell all of your jewelry and give it to the poor”

So they laid Jesus Christ in his graveWhen Jesus come to town all the working folks around

Believed what he did say

But the bankers and the preachers, they nailed him on the cross

So they laid Jesus Christ in his grave

Fight the power, and the power will fight back. Challenge accepted. But you expect your friends to have your back, not stab you in it. The other crucial connection between Jesus Christ and Jesse James was personal betrayal. McClintock blames “Bob Ford the coward” for turning against his friend, and Guthrie lays the same claim against Jesus’ most trusted disciple: “One dirty little coward called Judas Iscariot / Laid poor Jesus in his grave.” McClintock and Guthrie spell this out as singers and songwriters, but Dylan takes a subtler approach in The Philosophy of Modern Song. There is what Dylan commits to the page, then there is the more tantalizing art of the unsaid: gestures toward unnamed references looming off the page, implied between the lines, hiding in the shadows off stage.

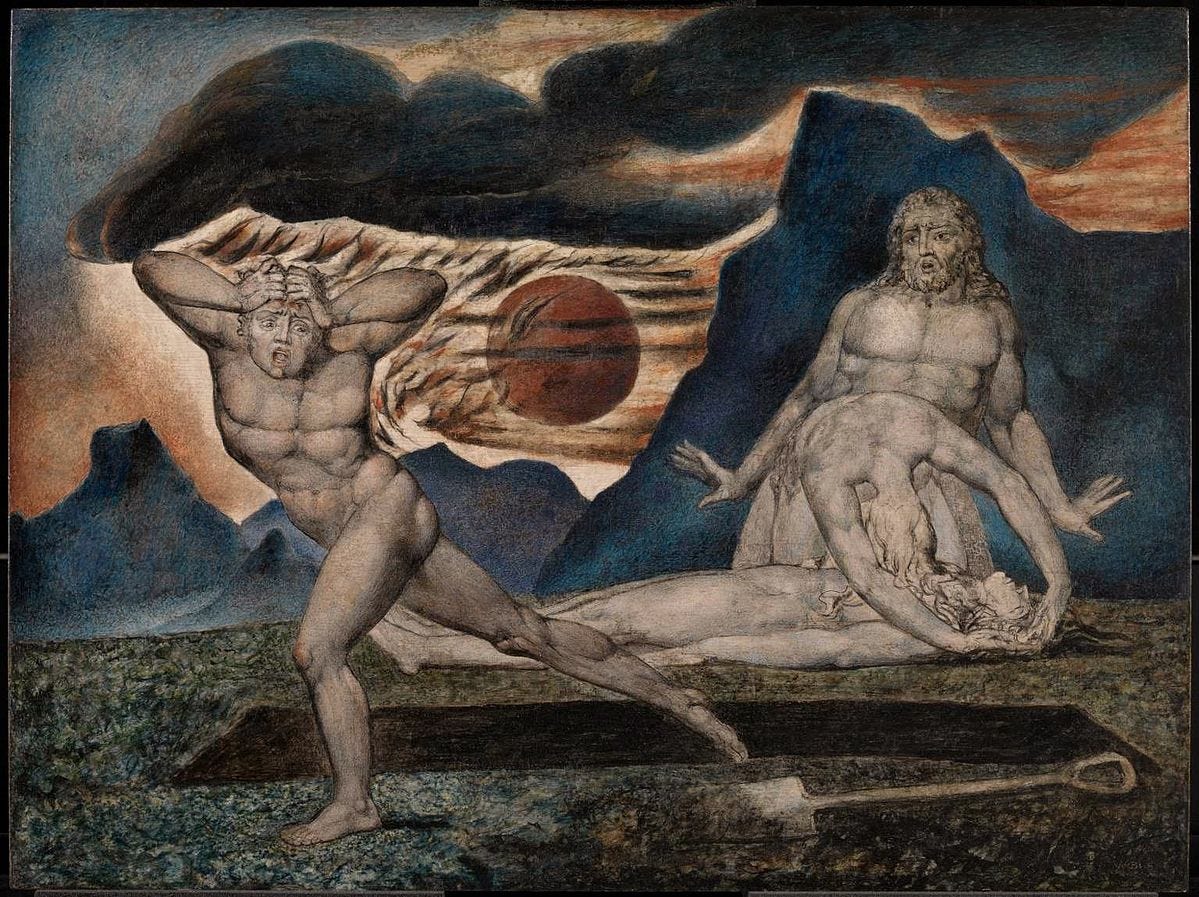

I see the silhouette of another scriptural figure on the fringes of these Holy Outlaw ballads. Dylan claims that outlaws are fundamentally different from common criminals: “But an outlaw has no protection from any group. He’s cut off from society. No sponsors, no family to speak of, and where he goes, he goes unprotected. He is forced to be a rugged individual with no friends and no place to hide” (47). Out on his own, with no direction home, like a complete unknown. This doesn’t sound much like Jesus, who was accompanied by disciples and attracted a ragged flock of devoted followers. But it does sound like the first scriptural outlaw: Cain.

The first-born child of Adam and Eve grew up to be a farmer, and his younger brother Abel grew up to be a shepherd. After God appeared more pleased with Abel’s sacrifice of meat than with Cain’s offering of grain, the older brother lashed out, killing his younger rival out of jealousy and spite. God responded by condemning Cain to a life sentence as permanent fugitive: “And now art thou cursed from the earth, which hath opened her mouth to receive thy brother’s blood from thy hand; / When thou tillest the ground, it shall not henceforth yield unto thee her strength; a fugitive and a vagabond shalt thou be in the earth” (Genesis 4:11-12). Uprooted from the soil he once nurtured and banished from his home, he was doomed to perpetual exile: “And Cain went out from the presence of the Lord, and dwelt in the land of Nod, on the east of Eden” (Genesis 4:16). “Nod” is the root for the Hebrew verb “to wander.” In other words, Cain’s destination was also his predestination. Cain establishes the prototype for all subsequent outlaws who follow in his doomed footsteps, fated to a life of endless wandering.

II

Lefty he can’t sing the blues

All night long like he used to

The dust that Pancho bit down south

Ended up in Lefty’s mouth

The day they laid poor Pancho low

Lefty split for Ohio

Where he got the bread to go

There ain’t nobody knows

--Townes Van Zandt, “Pancho and Lefty”

Screenshot from the official video for “Pancho and Lefty”: Townes Van Zandt (left), Willie Nelson (middle), Merle Haggard (right), Sacred Heart of Jesus (above).

When I use the phrase “the art of the unsaid,” I draw it from Dylan’s observation of Townes Van Zandt’s “Pancho and Lefty”: “A big part of songwriting, like all writing, is editing—distilling thought down to essentials. Novice writers often hide behind filigree. In many cases the artistry is in what is unsaid” (55). Dylan probably borrowed this notion from Brian T. Atkinson’s I’ll Be Here in the Morning: The Songwriting Legacy of Townes Van Zandt (2012), where musician Dave Alvin praises this very same gift in Van Zandt: “what he leaves out is so amazing. ‘Pancho and Lefty’ is a great song because of what he doesn’t say. The beautiful poetry is in the fine line between what he chooses to say and what he doesn’t” (157). What’s important here, however, isn’t where Dylan got the idea but what he does with it. Viewed through Dylan’s dualistic lens, “Pancho and Lefty” becomes a classic doppelganger story about two alter-egos intimately bound together yet locked in mortal combat, a story as old as Cain and Abel. “Pancho and Lefty. Two reflections of each other,” writes Dylan. “Pancho and Lefty are a match made in heaven but neither of them have found their true mate in life” (59). Dylan finds mates for them from the Holy Outlaws of scripture and from his own art.

Pancho is the obvious outlaw of the song, and in certain respects he resembles the notorious bandit and Mexican revolutionary Pancho Villa. But Dylan responds more sensitively to Pancho’s less illustrious counterpart Lefty. Dylan really opens up the song for me as a listener with this perceptive and provocative interpretation: “Lefty can’t sing the blues because he’s been screwed up in the mouth by something either Pancho or the Federales did. He can’t even talk, let alone sing. He drops out of sight, and ends up on the low side of Cleveland, in a fleabag hotel, on a lost-weekend trip, with thirty pieces of silver and a pistol to blow out his brains” (59). Note how the “thirty pieces of silver” reference unmistakably links Lefty to Judas, who sold out Jesus to the Romans for the same price. The symmetry of Pancho’s execution at the hands of the government and Lefty’s death by his own hand likewise mirror the fates of Jesus and Judas. Mind you, none of this is stated outright in the lyrics. The song leaves gaps to be filled at the discretion of the listener, and it is telling that Dylan chooses to fill them scripturally, interpreting “Pancho and Lefty” as a retelling of Judas’ betrayal of Jesus, transplanted to the Texas-Mexico borderlands of the early twentieth century.

If Dylan is guilty of inserting his own preoccupations into the song, he is only following Van Zandt’s lead. “Pancho and Lefty” seems at first like the quintessential two-person song, but then who is the shadowy figure in the first verse, referred to only as “you”?

Living on the road my friend

Was gonna keep you free and clean

And now you wear your skin like iron

And your breath’s as hard as kerosene

Weren’t your mama’s only son

But her favorite one it seems

She began to cry when you said goodbye

And sank into your dreams

Although this could refer to Pancho or Lefty, the distinct second-person voice suggests a separate third character. The most likely candidate is the songwriter/dreamer TVZ, inserting himself into the saga in the guise of “you,” the same mask Dylan frequently adopts in his own songs and throughout The Philosophy of Modern Song.

Dylan inserts himself into “Pancho and Lefty” through hints and associations. Some of his commentary applies more faithfully to own outlaw songs than to “Pancho and Lefty.” For instance, he describes the duo as “nonconformist thieves” who “attack the middle class, taking advantage of and exploiting their false values, materialism, hypocrisy, and insecurities” (59). Really? I don’t hear that at all in “Pancho and Lefty.” But I do hear it in the whispers of the Joker and the Thief in “All Along the Watchtower,” or the conspiracies of “Lily, Rosemary, and the Jack of Hearts” and “Isis,” or the knife-throwing, bone-bagging criminal exploits in the Land of Nod in “Tweedle Dee & Tweedle Dum.” Dylan asserts, “Pancho is also supplying the alcohol, drugs, and sex for them” (59). Oh really? Where are you getting that from? I don’t find it in “Pancho and Lefty,” but I do find it in the Jersified adaptation of the song, “Tweeter and the Monkey Man,” by those other wandering brothers Lucky Wilbury and Charlie T. Wilbury, Jr. One way or another, Dylan seems determined to read “Pancho and Lefty” in such a way that it leaves room for him to plant his cross between the two “nonconformist thieves.”

Dylan’s most interesting triangulation comes by way of performance, or more precisely a missing performance. I was initially disappointed that he chose to spotlight the hit single “Pancho and Lefty” by Willie Nelson and Merle Haggard. That version is good enough, but it goes down like cooking sherry when it should go down like throat-scorching kerosene, as does the straight-no-chaser original recording on The Late Great Townes Van Zandt. My first guess was that Dylan chose a two-singer rendition to mirror the two-character narrative of the song. But the more I began to appreciate this composition as really a trinity (Pancho, Lefty, and You), the less convincing that theory became. Now I suspect Dylan wanted to implicate himself into the song by silently gesturing toward his own live duet at Willie Nelson’s 60th birthday celebration. Dylan refers to Nelson backstage as a “philosopher-poet” before taking the stage to perform “Pancho and Lefty” with his fellow musical outlaw:

Willie Nelson and Bob Dylan sing “Pancho and Lefty,” KLUR Studios, Austin, Texas, 22 May 1993. YouTube video posted Peter Sugarman.

Holy Outlaws come in threes. “I don’t know why the number 3 is more metaphysically powerful than the number 2, but it is,” writes Dylan in Chronicles (159). In Chapter 12 of The Philosophy of Modern Song he expresses it in triplicate: three characters, three performances, and three pictures (1, 2, 3):

III

Back in El Paso my life would be worthless

Everything's gone in life, nothing is left

It’s been so long since I’ve seen the young maiden

My love is stronger than my fear of deathI saddled up and away I did go

Riding alone in the dark

Maybe tomorrow a bullet may find me

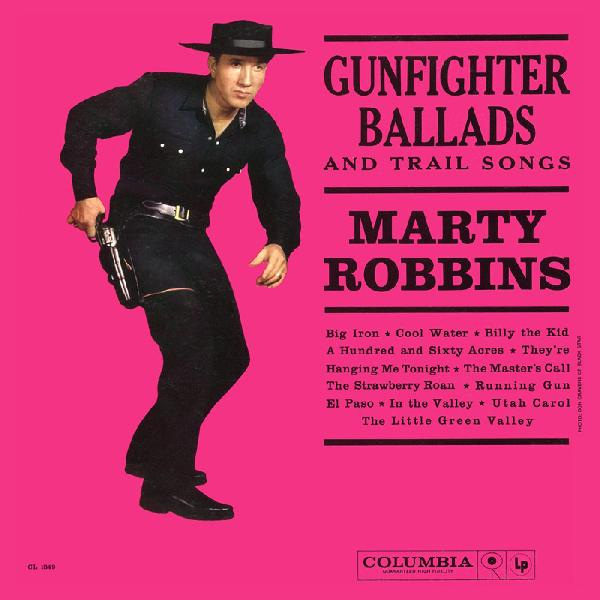

Tonight nothing's worse than this pain in my heartMarty Robbins, “El Paso”

Chapter 23 on Marty Robbins’s “El Paso” is among my very favorite in the entire book. “The song hardly says anything you understand, but if you throw in the signs, symbols, and shapes, it hardly says anything that you don’t understand” (105). You might say the same of Dylan’s riff on the song, which seems intellectually indecipherable yet intuitively spot-on, as if he gets the song on a deeper level than any listener or critic has before. Dylan hears “El Paso” as religious allegory. “This is a ballad of the tortured soul, the cowboy heretic,” he boldly declares at the beginning (105). And he’s just getting started: “This is Moloch, the cat’s eye pyramid, the underbelly of beauty, where you take away the bottom number and the others fall. The cowboy chosen one, bloody mass sacrifice, Jews of the Holocaust, Christ in the temple, the blood of Aztecs up on the altar. […] This is mankind created in the image of a jealous godhead. This is fatherhood, the devil god, and the golden calf” (105). I find these references as bewildering as you do, but they don’t strike me as random or meaningless. There is a string holding these rosary beads together, even if I don’t fully grasp it. References to Jews, Moloch, and the golden calf all jibe with the importance Dylan attributes to the Five Books of Moses in his Slate interview. But his other associations are all over the place—historically, geographically, and metaphysically—from Aztec sacrifices to Nazi genocide to Gnostic beliefs that this world was created by a deranged and spiteful Demiurge.

One thing is certain: Dylan doesn’t simply regard this as a romantic cowboy ballad. As he summarizes at the end of his commentary, “You can accept this song as the lovely lament of a dying cowboy drifting through exotic places and dying for a dancing girl that he hardly knows, or not” (111). “El Paso” means much more than that to Dylan. He debunks the idyllic myth of the singing cowboy and replaces it with a darker vision: the cowboy as tortured soul and heretic: the cowboy as cursed, lost, and doomed: the cowboy as Cain. “It’s a labyrinth of a song, it’s the end of the line for Roy Rogers, king of the cowboys. The end of beans, bacon and meat, bedrolls, and cow roping—code of the west and the longhorn drive. The end of the sheik, the gaucho, and the matador—where one bad bull will be the death of you, the lonely figure and the scamp—the cowboy scapegoat and this is his story” (108). And what comes at the end of the line for the cowboy scapegoat? What comes after violence, exile, and sacrifice?

While doing research for this piece, I came across an interesting book by Ricardo J. Quinones called The Changes of Cain: Violence and the Lost Brother in Cain and Abel Literature. Quinones studies the enduring appeal of the Cain and Abel myth, tracing its evolution and adaptation across time and cultures. I was particularly intrigued by his chapter on the regeneration of Cain in post-World War II American literature and film. Quinones never mentions Dylan, but the arguments seem relevant to some of his songs, as well as to his Cain-inflected reading of “El Paso.”

Among the spate of American works all invoking the Cain-Abel story that appeared after World War II, John Steinbeck’s East of Eden excels. In some ways, all of these works—and they include three films, The Gunfighter, Shane, and High Noon […], and two novels, Steinbeck’s work, and Herman Wouk’s The Caine Mutiny—are all concerned with defining the nature of the American experience, wherein the character of Cain becomes something of a national type. (135)

Quinones points out several Cain-influenced works I had never recognized as such—including Jean Toomer’s Cane and Orson Welles’s Citizen Kane—but which now seem obvious, hiding in plain sight. I was especially interested by the works he chose to highlight after World War II because of their connections to Dylan. Readers of Shadow Chasing will know The Gunfighter as the film at the heart of “Brownsville Girl,” where Gregory Peck plays the hounded gunslinger Jimmy Ringo. One of Dylan’s other cinematic heroes, James Dean, had his film debut in East of Eden, adapted from Steinbeck’s novel by Elia Kazan. Dean plays the Cain-figure Cal Trask, son of Adam, who eventually kills his brother Aron, the Abel-figure of the story.

How is Cain an American national type? According to Quinones, each of these works meditate upon national identity and purpose, “about violence and guilt, about the justification of violence (hence its relation to World War II) and the transcendence of guilt” (135). A key factor in Quinones’s estimation is immigration, the wandering experience of Cain, but mobilized into collective national action to fight fascism during the war:

In the larger sense, as the Civil War destroyed the agricultural and Edenic myth of an Adamic innocence, immigration and the emergence of America after World War II helped create the myth of a regenerate Cain. Steinbeck understood that the primary American myth had been transformed from the American Adam to the American Cain, and that World War II had represented the crucial experience by which a nation of immigrants had coalesced into a formidable entity. (Quinones 143)

To illustrate this argument, Quinones cites a revealing passage from Steinbeck’s East of Eden. Lee, a Chinese immigrant and longtime domestic worker for the Trask family, speaks to Cal about the interwoven threads of violence and immigration in the fabric of American experience:

“We’re a violent people, Cal. Does it seem strange to you that I include myself? Maybe it’s true that we are all descended from the restless, the nervous, the criminals, the brawlers, but also the brave and independent and generous. If our ancestors had not been that, they would have stayed in their home plots in the other world and starved over the squeezed out soil.” (Steinbeck 570)

I cite Quinones and Steinbeck at length because this idea of a “regenerate Cain” gives me a better grip on what Dylan is doing in his “El Paso” chapter. Look at the trajectory the singer follows in Dylan’s translation of the song. He begins as a tortured soul who kills his rival out of anger and jealousy. He goes on the run from the law—becomes an outlaw. But he refuses to remain in exile forever. He returns to the scene of the crime, a new man with a new mission. The cowboy heretic transforms into the cowboy chosen one, the cowboy martyr. He comes full circle, returning to sacrifice himself for love.

Simply put, the singer in “El Paso” begins the song as Cain and ends it as Jesus.

As if to punctuate the point, the song ends with a pietà:

From out of nowhere Felina has found me

Kissing my cheek as she kneels by my side

Cradled by two loving arms that I’ll die for

One little kiss and Felina, goodbye

“They pump you full of lead and shoot you off your horse,” writes Dylan. “It’s there that Felina finds you, and takes her place beside you, kissing your cheek while you’re slowly dying—cradles you in her two loving arms, lays her hands on you and kisses your lips, and you kiss her back, with a kiss that says I forgive you” (108). In the context of Dylan’s Holy Outlaws, the closing kiss feels less like a romantic resolution and more like Jesus forgiving Judas for the kiss that betrayed him and led to his death.

This intertextual dialogue between Holy Outlaw songs has me rethinking Dylan’s most overt reference to Cain in “Every Grain of Sand”:

Don’t have the inclination to look back on any mistake

Like Cain, I now behold this chain of events that I must break

In the fury of the moment I can see the Master’s hand

In every leaf that trembles, in every grain of sand

The fugitive and exile Cain, driven onward, trying not to look back at the devastation he leaves in his wake. The name Cain calls to mind the word Chain. The singer feels like a link in a larger chain, born into this life shackled to a destiny forged by someone else. When he says, “In the fury of the moment I can see the Master’s hand,” is he implying that God had a hand in Cain’s furious killing of Abel? Was the first outlaw murder not a defiance of God’s law but a fulfillment of his divine plan?

This is essentially the theological argument of The Last Temptation of Christ. One of the most controversial moves in both Kazantzakis’s novel and Scorsese’s film is the portrayal of Judas not as a villain but as a hero. He is the crucial catalyst necessary for the realization of Christ’s sacrifice. Jesus tells Judas, “Remember, we’re bringing God and man together. They’ll never be together unless I die. I’m the sacrifice. Without you, there can be no redemption. Forget everything else. Understand that.” But Judas balks: “If you were me, could you betray your master?” Jesus replies, “No. That’s why God gave me the easier job, to be crucified.” In betraying his master Jesus, he is obeying his Master God. Judas was simply playing his necessary role in the drama of Christ’s sacrifice, a role scripted for him by the Almighty.

If God is the Master of all, then his dominion encompasses the bad things as well as the good. Cain and Judas were both part of the Master’s plan. Like every sparrow falling, like every grain of sand, they are links in the chain of destiny. Young Dylan asked, “Are birds free from the chains of the skyway?” No, answers Old Dylan in the Slate interview: “I believe in damnation and salvation, as well as predestination.”

Abel and Jesus need your prayers, it’s true. But save a few for Cain and Judas, too. They only did what they had to do.

Works Cited

Atkinson, Brian T. I’ll Be Here in the Morning: The Songwriting Legacy of Townes Van Zandt. Texas A & M University Press, 2012.

Dylan, Bob. “Absolutely Sweet Marie.” Blonde on Blonde. Columbia, 1966.

---. “Ballad in Plain D.” Another Side of Bob Dylan. Columbia, 1964.

---. Chronicles, Volume One. Simon & Schuster, 2004.

---. “Every Grain of Sand.” Shot of Love. Columbia, 1981.

---. The Philosophy of Modern Song. Simon & Schuster, 2022.

Guthrie, Nora, and Robert Santelli. Woody Guthrie, Voice of the People: Songs and Art, Words and Wisdom. Chronicle Books, 2021.

Guthrie, Woody. Bound for Glory. E. P. Dutton, 1968.

---. “Jesus Christ.” Folkways: The Original Vision, The Songs of Woody Guthrie and Lead Belly. Smithsonian Folkways, 2005.

---. “Pretty Boy Floyd.” Folkways: The Original Vision, The Songs of Woody Guthrie and Lead Belly. Smithsonian Folkways, 2005.

Joyce, James. Ulysses. Penguin, 2000.

McClintock, Harry. “Jesse James.” Victor, 1928.

Quinones, Ricardo J. The Changes of Cain: Violence and the Lost Brother in Cain and Abel Literature. Princeton University Press, 1991.

Robbins, Marty. “El Paso.” Gunfighter Ballads and Trail Songs. Columbia, 1959.

Slate, Jeff. “Bob Dylan Q&A about ‘The Philosophy of Modern Song.’” Wall Street Journal (19 December 2022), http://www.bobdylan.com/news/bob-dylan-interviewed-by-wall-street-journals-jeff-slate/.

Steinbeck, John. East of Eden. Penguin, 1986.

Van Zandt, Townes. “Pancho and Lefty.” The Late Great Townes Van Zandt. Poppy, 1972.

Yeats, William Butler. “Crazy Jane Talks with the Bishop.” Poetry Foundation, https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/43295/crazy-jane-talks-with-the-bishop.

Wow. Another great essay. Your research is superb. I like the way you don't panic when faced with Dylan text that is like the intuitive strokes of paintbrush rather than a high resolution photograph and so has multiple readings (plus we are multitudes and have our own readings). Dylan.fm@fmc_dylan just posed some important lines for Christopher Ricks' Dylan's Vision of Sin on twitter (rumor has it your not "there" on twitter--good for you!) about the intuition of the artist, the pictoral and emotional picture, rather than the detailed intention. If you can't find the page numbers, I'll give it a try. Meanwhile, on the subject of stripping things down and the unsaid. Dylan was doing this from the early days. Ricks also points out no where does the Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll mention black, negro or other references to African American. But we know! We know we the sudden realization that we know because of the history of racism. That is not just stripping down but actually a dramatic moment in hearing the song. And one other early song that hides and then tells: Boots of Spanish Leather, where the two voices, one stronger, one sadder, are not assigned a gender until the 7th stanza. Which voice is Dylan's? Usually it is the male who goes off to seek a fortune; many women friends have expressed surprise when they come upon "her" in that 7th stanza. And also in that song: the title gets us curious from the beginning. What do boots have to do with it? Is this a reference to the old song Gypsy Davie? And here Dylan creates meaning with an added seemingly unnecessary word. Not only Spanish Boots but Spanish Boots of Spanish Leather. For the boots MUST be genuine, just as the lovers calling each other "true" love suggests a genuine purity that hid an underlying split, the boots desired to try to fill the gap...and maybe to walk on away from there. The meaning of the title appears doesn't appear until the last line of the last stanza of the song.

Graley

I wish I could be your student. There is so much information in this piece that I have never studied or overlaid on top of Dylan's work. My interpretation of Dylan is a one lane highway void of the Bible and great literature. I see him through the small lens of my life and understanding of human nature. Thank you for such an illuminating essay.

Happy New Year