Gypsy Dylan

Graley Herren

Nostalgia is the essence of Gypsy song, and seems always to have been. But nostalgia for what? Nostos is the Greek for ‘a return home’; the Gypsies have no home, and, perhaps uniquely among peoples, they have no dream of a homeland. Utopia—ou topos—means ‘no place.’ Nostalgia for utopia: a return home to no place. O lungo drom. The long road.

Isabel Fonseca, Bury Me Standing: The Gypsies and Their Journey

I

What is the deal with Dylan and Gypsies?

Gypsies frequently make appearances in his songs over the years, from “Gypsy Lou” to “Gypsy Davey,” from his “Spanish Harlem Incident” with a “Gypsy gal” on Another Side of Bob Dylan, to the time he “Went to See the Gypsy” on New Morning, and several other later references. The look, sound, and entire ethos of the Rolling Thunder Revue seems modeled after some idyllic notion of the Gypsy caravan. More recently, Dylan draws attention to other people’s songs about Gypsies in The Philosophy of Modern Song. In this post I want to explore Dylan’s identification with Gypsies in his latest book. I’ll be spotlighting two songs in particular: “Willy the Wandering Gypsy and Me” by Billy Joe Shaver and “Gypsies, Tramps & Thieves” by Cher. In yet another example of “the art of the unsaid,” Dylan inserts himself and his own songs into these chapters, too, even though he never says it in so many words.

Before turning to Dylan’s book, however, it’s important to establish a few things about the highly problematic term “Gypsies.” This label was a misrepresentation from the start. When the group it labels migrated out of northwestern India and into Europe several hundred years ago, they were routinely misidentified as hailing from Egypt, or from Little Egypt in western Greece. As evidence of my own ignorance, I didn’t realize until beginning this study that “Gypsies” is a corruption of “Egyptians.”

The term “Gypsy” has fallen out of favor in recent years as irredeemably loaded with negative stereotypes. Among many Roma people today it is regarded as an insult or racist slur. Even my cursory research shows that this issue is complicated and contested. Jodie Matthews notes that, among Romanies she interviewed for her book on representations of Gypsy women, “There are still people who self-identify as ‘Gypsy,’ and there is a degree of debate within the Romani community of Britain as to whether this should be seen as a derogatory exonym or proudly reclaimed label” (10). I gather that a lot of scholars in this field retain the term “Gypsy,” not to be culturally insensitive, but because they aim to critique the Orientalist stereotypes it (mis)names.

For my part, I see no way of avoiding the label because it is everywhere in the chapters and songs I’ll be quoting from. I apologize for any offense this might cause. Please understand that I’m not attempting to make an ethnographic study of the real Roma people. I am simply trying to figure out what Gypsies mean to Dylan’s art, and what he’s doing with the recurring Gypsy trope in The Philosophy of Modern Song. Now let’s take a look and have a listen.

II

On the road again

Like a band of Gypsies we go down the highway

We’re the best of friends

Insisting that the world keep turning our way

And our way

Is on the road again

Willie Nelson, “On the Road Again”

Billy Joe Shaver performs “Willy the Wandering Gypsy and Me” on Austin City Limits (14 August 1984). YouTube video posted by Walter Brinkman.

Dylan’s endless fascination with the number 3 will be familiar to all readers of Shadow Chasing. Trilogies of albums and three-character songs are ubiquitous throughout his career, and triplicate images are scattered throughout The Philosophy of Modern Song. As a prose writer, Dylan seems particularly engaged with the three-way interplay of narrative voices:

I / You / Stranger

1st Person / 2nd Person / 3rd Person

The dominant voice of this book is the middle figure You. If you were inclined to make bad puns, you might say “You” is you-biquitous in The Philosophy of Modern Song. “It’s what a song makes you feel about your own life that’s important” (9). Dylan the Gemini thinks and creates in terms of oppositional forces fated to eternal struggle: doppelgangers, twins, shadow selves. Those battles are fought first in pairs. In his songs, however, and in many of those he highlights in this book, he fixes upon a middle position located at the intersection where the opponents converge and merge together. In this book, that middle position goes by the name You. A perfect example is his riff on Billy Joe Shaver’s “Willy the Wandering Gypsy and Me.”

This sounds at first like a classic two-person song: Willy the Wandering Gypsy (#1) and Me (#2). But Dylan messes with these neat categories by replacing the Me with You. “You and Willy, the wise man and the fool” (26). He wedges in that middle perspective to turn Shaver’s duo into a trio: “There’s you, and there’s Willy and there’s the wandering Gypsy. Maybe one, maybe two people or maybe three” (25). He repeats the point for emphasis in the final paragraph: “There’s three people in the song. There’s Willy, there’s the wandering Gypsy, and then there’s you” (27).

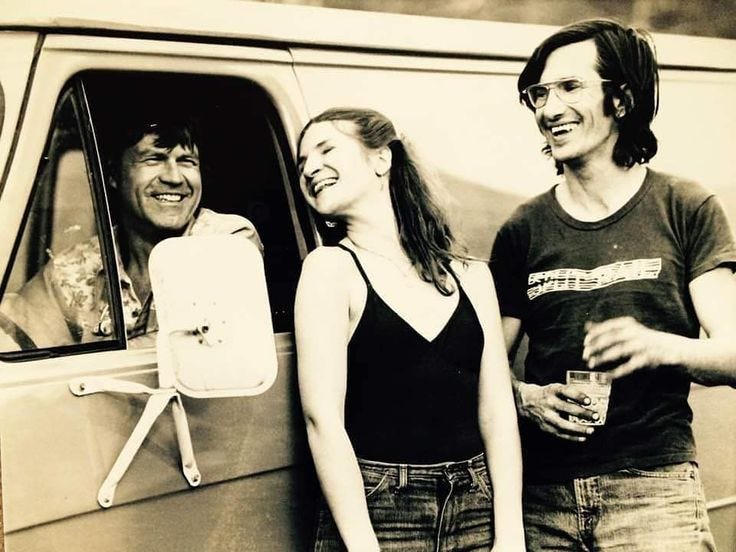

These three amigos all share a common aspiration: they want to escape their boring lives and go on the road like a band of Gypsies. Both Shaver’s song and Dylan’s riff romanticize the wandering life. Shaver sings, “Willy he tells me that doers and thinkers / Say moving is the closest thing to being free.” Dylan thinks the same way: “This song has a philosophical point of view. Keep moving, it’s better, let the train keep rolling. It’s better than drinking and crying in your beer. Let’s go. Let’s go forever” (26). According to this philosophy, Gypsies represent the epitome of freedom, and the characters in this song long to liberate themselves from the ties that bind them to home.

The singer admits, “My woman’s tight with an overdue baby.” Family, commitment, responsibility, domesticity. If home is the problem, then the solution is the road: “Willy keeps yelling hey Gypsy let’s go.” To be a Gypsy in this context has nothing to do with ethnicity or the actual cultural practices of the Roma people. To be a Gypsy is to be a mover, not a stayer, even if—especially if—leaving means walking out on your obligations to those left behind. “To live is to fly,” as Townes Van Zandt put it; and by implication, to nest is to die. “But it don’t pay to think too much / On things you leave behind,” counsels TVZ on his way out the door. “So shake the dust off of your wings / And the tears out of your eyes.”

Dylan opens his chapter on “Willy the Wandering Gypsy and Me” with this teaser: “This is a riddle of a song, the further you go with it, the stranger it gets, seems to have ulterior motives. Kind of song you don’t see coming until it’s on you” (25). This is a Sphinx-like riddle of a riff, too, and the answer lies in Egypt:

The sure thing about Gypsies is they travel in packs, tribes, and clans. Gypsies have home rule, been sticking together for centuries. Some historians say they came out of Egypt, the original Egyptians. Forced from their home country by African workers, who were imported to do the manual labor—who eventually overran the indigenous people. Gypsies never travel alone, they’re self-sufficient, and they don’t take honorary members. If Willy’s a Gypsy, then he’s an imposter. (25)

As we’ve already established, the legend about the Roma people originating in Egypt is bogus, and most of Dylan’s claims in the passage above are dubious at best. We could simply chalk it up to sloppy research and stereotypical profiling and leave it at that, but then we’d overlook the most interesting parts. The point here isn’t historical accuracy: the point is Egypt. Because if Dylan can trace the Gypsies back to Egypt, then he can stage a convergence with his own Jewish ancestry. As he told Martin Keller in a 1983 interview:

My so-called Jewish roots are in Egypt. They went down there with Joseph, and they came back out with Moses, you know, the guy that killed the Egyptian, married an Ethiopian girl and brought the law down from the mountain. The same Moses whose staff turned into a serpent. The same person who killed 3,000 Hebrews for getting down, stripping off their clothes and dancing around a golden calf. These are my roots. (755)

He has used this synchronicity before—common roots in Egypt and a shared legacy of slavery—to forge a transhistorical connection with African Americans, most overtly in the song “Precious Angel”: “We are covered in blood, girl, you know our forefathers were slaves”; and “On the way out of Egypt, through Ethiopia, to the judgment hall of Christ.” Here Dylan makes the same rhetorical sidestep to connect his Jewish heritage with the nomadic Gypsies of lore, effectively conflating the trope of the Wandering Gypsy with that of the Wandering Jew.

Dylan also inserts himself into “Willy the Wandering Gypsy and Me” by way of an evocative photograph:

Given its placement in this chapter, the reader automatically assumes this is a group of Gypsies having a drink at some roadside establishment. When I hunted the picture down online and saw the Portugal setting in the caption, it made me think of that line from “Sara”: “Drinkin’ white rum in a Portugal bar.” Right album, wrong song. Look closer at the dark contents of the drink in the man’s hand. When I tell you that I found this photo on a website advertising coffee, you’ll make the connection quicker than I can type it out. Dylan incorporates this photo into the chapter on “Willy the Wandering Gypsy and Me” as a winking self-allusion to his own Gypsy song, “One More Cup of Coffee (Valley Below).”

Dylan frequently told interviewers and audiences about the backstory behind “One More Cup of Coffee.” For example, before playing the song in concert on 21 November 1978, Dylan told the El Paso crowd:

I was over in the south of France a few years back. The Gypsies from all over Europe have their big high holy day. Happens to be on my birthday also, so I thought I’d better check that out. All the Gypsies come from all over Europe, everywhere. Anyway, they party for a week and I met the King of the Gypsies over there. He’s a man had 16 wives and 120 children. Yeah. Anyway, I partied over with them for a week. I did most everything I could think to do and in the last few days I didn’t do anything but drink coffee. So when it’s time to go he said “OK, Bob, thanks. Now you’re on your way, what would you like?” I said, “One more cup of coffee”. Anyway, there was a big valley spread out over there and I just played “One More Cup of Coffee” and headed out East. (transcription by Olof Björner)

The timing of the celebration on his birthday (24 May) would have given Dylan a special sense of connection to the Gypsy celebration at Saintes-Maries-de-le-Mer. As a lost wanderer trying to process the breakup of his marriage, Dylan must also have been powerfully struck by the object of veneration at this ceremony: Sara-la-Kali, aka Black Sara, aka the Black Madonna, the Patron Saint of the Gypsies.

The “Wandering Gypsy” of Shaver’s song morphs in this context into Dylan’s King of the Gypsies: “Your daddy he’s an outlaw / And a wanderer by trade.” The singer in “One More Cup of Coffee” is a restless wanderer, too. He hangs out with the Gypsies long enough to get drunk, fall in love, then sober up with a steaming cup of joe before returning to his travels: “One more cup of coffee for the road / One more cup of coffee before I go / To the valley below.” This is a song about a man torn between staying and going. He has made his choice, or his restless spirit has made it for him: he must go. But he’s reluctant to leave, so he prolongs his journey by having just one more cup of coffee. “This is a riddle of a song,” claims Dylan, and he matches it with a visual riddle of his own, alluding to one of own Gypsy songs. He relates so closely to Shaver’s song because he has essentially written a variation on it himself.

III

I was born in the wagon of a traveling show

My mama used to dance for the money they’d throw

Papa would do whatever he could

Preach a little gospel

Sell a couple bottles of Doctor Good

Cher, “Gypsies, Tramps & Thieves”

Cher performs “Gypsies, Tramps & Thieves.” YouTube video posted by TakeMeHomeTT.

The characters in Shaver’s song talk a big game about pulling up stakes and hitting the road. But all their boastful dreams are uttered in future-tense, perpetually deferring their adventures to some rosy-dawned tomorrow. In truth, they probably never actually go anywhere. Not so for “Gypsies, Tramps & Thieves.” The singer was born on the road. She lives out of a Gypsy caravan and travels with her family in a medicine show. The family members each supply various forms of entertainment and relief, in both daytime and nighttime doses. Then the caravan hustles down the road before anyone can punish them for selling what the townsfolk are ashamed to have bought. Transactions made on Saturday night easily turn into buyer’s remorse on Sunday morning. In this song, as throughout history, the Gypsies make for easy scapegoats:

Gypsies, tramps, and thieves

We’d hear it from the people of the town

They’d call us Gypsies, tramps, and thieves

But every night all the men would come around

And lay their money down

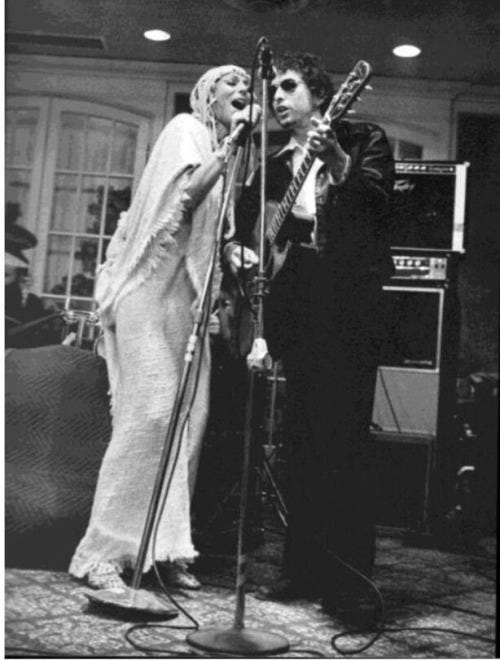

“Gypsies, Tramps & Thieves” makes an interesting companion piece alongside “Willy the Wandering Gypsy and Me.” Philosophically, they are both road songs: “This is a song about being on the move and keeping it moving—being born on the move” (231). This is the spirit that Dylan and his band of rovers sought to embody in the Rolling Thunder Revue, which Allen Ginsberg described as “a con-man, carny medicine show of old, where you just get in a bus or carriage and go from town to town.”

But “Gypsies, Tramps & Thieves” also offers a counterbalance to the fantasy with its deromanticized depiction of life on the road from a woman’s perspective. At the age of 16, the singer hooked up with a 21-year-old man in Mobile, stuck with him long enough to get pregnant, then he jilted her in Memphis [coordinates sure to strike a chord with the author of “Stuck Inside of Mobile with the Memphis Blues Again”]. So the cycle continues. With a daughter in tow and a mouth to feed, the singer takes up the family business, becoming a sex worker like her mother before her, presumably pimped out by her father. O lungo drom. The long road.

Despite the singer’s hardships, Dylan emphasizes her resilience over her victimization. Riffing again through his signature “you” voice, he observes, “There’s never been a day when you haven’t woken up and said that this wasn’t going to be a good day” (232). Along these same lines, Dylan writes, “Your philosophy of life is wait and see” (233). Being a Gypsy certainly contributed to the singer’s hard times and social ostracization, but her Gypsy identity also helps her endure with a sense of purpose and community: “It’s a family thing. Cousins, half-brothers, aunties, grand uncles, nieces, cousins twice removed, a fraternal order and sisterhood, an enclosed circle is what it is, a secret society” (232). The singer is in on this secret. Meanwhile, the commentator still has some cards up his sleeve, too.

As with the Shaver song, I sense that Dylan inserts himself subtly into Cher’s song by way of one of his own: “Blind Willie McTell.” This great song builds a connection between Jerusalem and New Orleans, between Dylan’s Jewish roots and the African American home of jazz and the blues. The connection comes through lyrically in his references to the Passover in the first verse, and it comes through musically in his adaptation of the tune from “St. James Infirmary.” Michael Gray hears a Jewish allusion in the tents of the second verse, but he hears other echoes, too: “‘Takin’ down the tents’ gives us another glimmer of the Israelites, now on their way out of Egypt, but suggests too the medicine shows, the carnival tents that linger into the twentieth century from an older America” (542). And here we are propelled into the world of “Gypsies, Tramps & Thieves”:

Well, I heard that hoot owl singing

As they were taking down the tents

The stars above the barren trees

Were his only audience

Them charcoal Gypsy maidens

Can strut their feathers well

And I can tell you one thing

Nobody can sing the blues

Like Blind Willie McTell

Compare the scenario described in “Blind Willie McTell” to Dylan’s description of Cher’s protagonist: “Strip yourself bare and dance the sword dance, buck naked inside of a canvas tent, fenced in, where the town royalty, the top brass and leading citizens, bald as eggs throw their money down, sometimes their entire bankroll” (232). The tent in Dylan’s “Blind Willie McTell” could play host to a risqué burlesque show or a Christian revival meeting, and like the tent in “Gypsies, Tramps and Thieves,” it probably transitions daily from one into the other. There are no hoot owls per se in Cher’s song, though the hooting eggheads in the audience will suit the purpose just as well.

The charcoal of Dylan’s Gypsy maidens may imply another scenario, namely that the performance is in blackface. To be fair, there is nothing in Cher’s song to suggest a minstrel show. However, to the extent that Cher is singing as a Gypsy character, there is cross-cultural imposture in her performance. Cher was born Cherilyn Sarkisian, and her father was of Armenian descent, but as far as I know she has no Roma ancestry. As for Dylan, we know he has a more vexed relationship with the blackface minstrel tradition, one of both love and theft. Viewed from a loving perspective, Dylan’s creative approach for the riffs in The Philosophy of Modern Song are an exercise in empathy and transfiguration, imagining his way into the experiences of another. Viewed from the perspective of theft, Dylan tramps across the borders of ethnicity and gender to play a gypsy maiden. A little charcoal might prove a handy accessory for this brand of transgressive performance.

Dylan doubles down on the Egyptian theme as well. In his commentary to “Gypsy, Tramps & Thieves,” he writes, “The tarnished-angel myth is a hard one to buy into. It’s much easier to imagine Little Egypt doing her dance of the pyramids. At least it seems like she was having fun beguiling men” (235). The reference here is to Leiber and Stoller’s song “Little Egypt.” It was first recorded by The Coasters in 1962, but became better known when Elvis Presley included the song and an elaborate dance number in his 1964 film Roustabout. However, I suspect Dylan has a couple other performances in mind. Check out this outtake from Elvis’s ’68 Comeback Special, and see if you notice the iconic similarities with Dylan’s “comeback special” Shadow Kingdom:

Outtake of Elvis Presley’s performance of “Little Egypt” for his ’68 Comeback Special. YouTube video posted by @elvispresley.

Dylan is probably also aware of the deleted scene from the 1985 film Mask in which Cher performs the song “Little Egypt” around a campfire:

Cher sings “Little Egypt” in deleted scene from Mask. YouTube video posted by DarkLadyUK.

“Little Egypt” is about a burlesque dancer who mesmerizes the singer, but she later settles down with him as wife and mother to seven kids. In that respect, “Little Egypt” occupies a middle position between the dancer in Cher’s song and the pregnant wife back home in Shaver’s song.

Burlesque is also a common link binding together those Gemini divas Dylan (born 24 May 1941) and Cher (born 20 May 1946).

Burlesque has been a major influence for years on Cher’s style and celebrity personae, and she makes those debts most explicit in her role as a burlesque club owner in the 2010 movie Burlesque. Dylan also identifies with burlesque as a performer. The same year that Cher performed “Little Egypt” in Mask, Dylan released an album titled Empire Burlesque in 1985. In his 1997 London press conference, he reflected: “Performing’s all the same. When you’re up on stage, and you’re looking at a crowd and you see them looking back at you, you can’t help but feel like you’re in a burlesque show” (1201). He reiterated this point in his 2001 Rome press conference: “The stage is the only place where I’m happy. It’s the only place you can be what you want to be. When you’re up there and you look at the audience and they look back then you have the feeling of being in a burlesque. But there’s a certain part of you that becomes addicted to a live performance” (1259).

By riffing on “Gypsies, Tramps & Thieves” and by vicariously inhabiting the character of a Gypsy sex worker, Dylan gives himself a literary stage to strut his feathers well: part carnival, part strip-tease, part minstrelsy, and part drag show. It’s Dylan’s Little Egypt dance. He steps outside of I and slinks toward the Stranger in the guise of You. Viewed from the perspective of theft, it’s his way of bringing it all back home to a place that never existed in the first place. Viewed from the perspective of love, it’s his way of obeying God’s commandment, as delivered through his messenger Moses, to the Israelites during their long journey through the wilderness: “But the stranger that dwelleth with you shall be unto you as one born among you, and thou shalt love him as thyself; for ye were strangers in the land of Egypt” (Leviticus 19:34).

Thanks for reading Shadow Chasing! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Works Cited

Björner, Olof. Still on the Road. https://www.bjorner.com/still.htm.

Dylan, Bob. “Blind Willie McTell.” The Bootleg Series Volumes 1-3 (Rare & Unreleased), 1961-1991. Columbia, 1991.

---. London Press Conference, Metropolitan Hotel (4 October 1997). Every Mind Polluting Word: Assorted Bob Dylan Utterances, edited by Artur Jarosinski, Don’t Ya Tell Henry, 2006, pp. 1197-1213.

---. “One More Cup of Coffee (Valley Below).” Desire. Columbia, 1976.

---. The Philosophy of Modern Song. Simon & Schuster, 2022.

---. “Precious Angel.” Slow Train Coming. Columbia, 1979.

---. Rome Press Conference, De la Ville Inter-Continental Roma Hotel (23 July 2002). Every Mind Polluting Word: Assorted Bob Dylan Utterances, edited by Artur Jarosinski, Don’t Ya Tell Henry, 2006, pp. 1259-63.

---. “Sara.” Desire. Columbia, 1976.

Fonseca, Isabel. Bury Me Standing: The Gypsies and Their Journey. Vintage, 1995.

Gray, Michael. Song & Dance Man III: The Art of Bob Dylan. Cassell, 2000.

“Gypsies, Tramps & Thieves.” Written by Bob Stone, performed by Cher. Gypsies, Tramps & Thieves. Kapp, 1971.

Keller, Martin. “Religion Today Bondage Tomorrow.” New Musical Express (6 August 1983). Every Mind Polluting Word: Assorted Bob Dylan Utterances, edited by Artur Jarosinski, Don’t Ya Tell Henry, 2006, pp. 753-56.

Matthews, Jodie. The Gypsy Woman: Representations in Literature and Visual Culture. I. B. Tauris, 2018.

“On the Road Again.” Written and performed by Willie Nelson. Honeysuckle Rose. Columbia, 1980.

Rolling Thunder Revue: A Bob Dylan Story by Martin Scorsese. Netflix, 2019.

“To Live Is To Fly.” Written and performed by Townes Van Zandt. High, Low and In Between. Poppy, 1971.

“Willy the Wandering Gypsy and Me.” Written and performed by Billy Joe Shaver. Old Five and Dimers Like Me. Monument, 1973.

What a great piece. With regards to the number 3 I can't help but think of Renaldo and Clara and the lyric" I play both sides against the middle" from Key west Philosopher.

Great essay, opening up insights not only into two of the PoMS songs but essential reading for anyone interested in a deep and serious consideration of the whole of PoMS. Thorough in its reach into other Dylan creations.