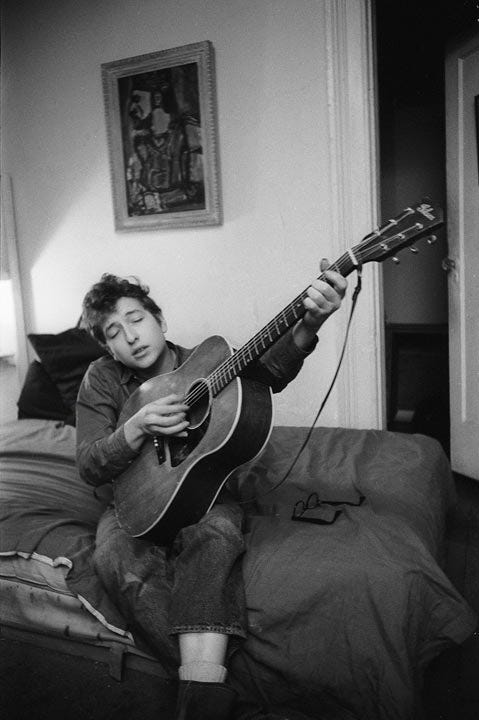

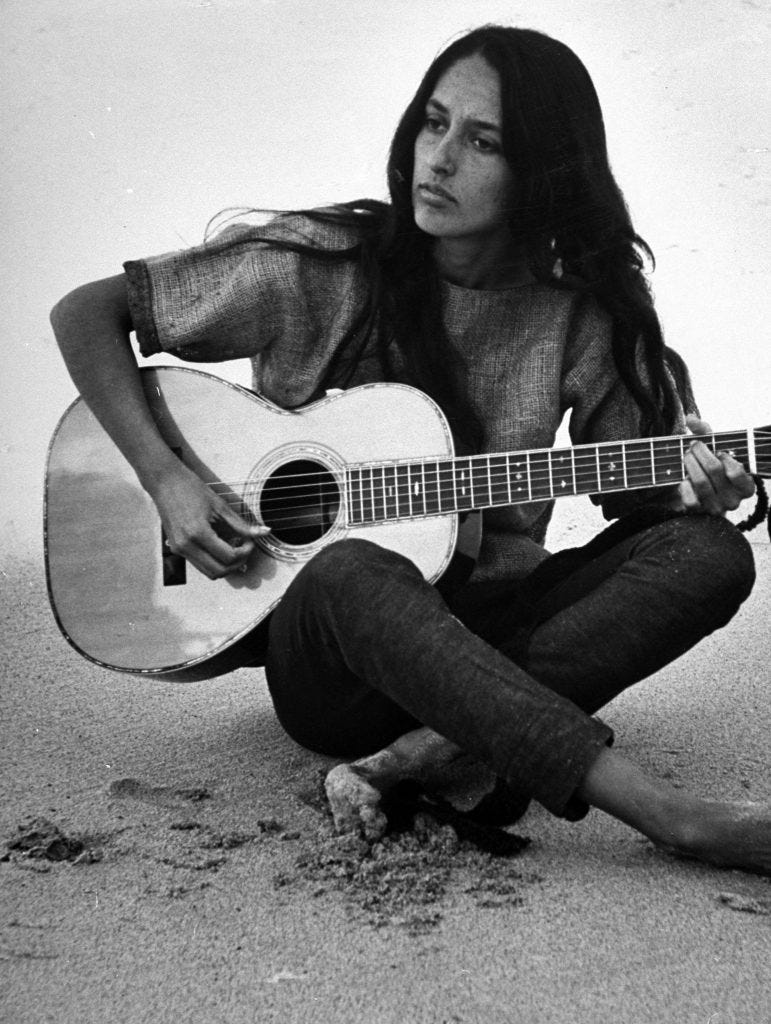

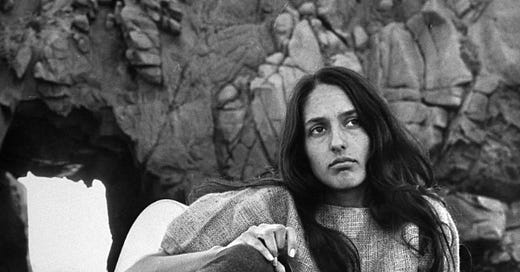

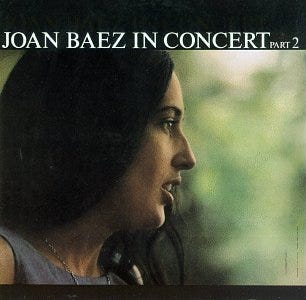

“Poem to Joanie” first appeared as the liner notes to Joan Baez in Concert, Part 2, released in November 1963. This live album, recorded between April and May that year, includes covers of four Dylan songs: “Don’t Think Twice, It’s Alright,” “With God on Our Side,” “Death of Emmett Till,” and “Tomorrow Is a Long Time.” The liner notes are untitled, but it was later published as “Poem to Joanie,” first by A. J. Weberman and later in a limited run in England. I first encountered the poem in Lyrics, 1962-1985, which was a Christmas present from my mother in 1985.

I’ve been thinking a lot about this poem recently, so I maybe it’s worth preserving some of these thoughts in writing. As is usually the case, I’m not writing to communicate what I think so much as to discover what I think. The writing is an extension of the pondering process.

I forget what led me back to reread this poem for the first time in many years. I mentioned something about it in a comment on Laura Tenschert’s Definitely Dylan Patreon page. We briefly discussed the poem in one of our monthly Zoom sessions. [Laura is awesome, and I encourage all of my readers to support her on Patreon.] Peter White and Robin Haar are members of that group, and they decided there was still more to say on this subject. So Peter made Dylan’s early poetry the subject of his monthly Bob Dylan book club meeting, It’s Alright, Ma (I’m Only Reading) [another wonderful group worth your support]. Robin led us in a spirited discussion earlier this month.

After exchanging ideas with so many smart Dylan fans, it’s hard to remember which of these ideas were independently formed on my part, and which ideas were inspired by or pilfered from someone else. So let me begin with an all-encompassing thanks to the members of Laura’s Patreon gang and Peter’s book club for reigniting my interest in this fascinating early poem by 22-year-old Bob Dylan.

The Poem

It’s always a tricky business to equate the “I” with Dylan himself, or with any author who uses first-person voice for that matter. But lots of details in the poem invite us to make that assumption in this poem, so I’ll take the bait, with all the usual caveats about this being a work of art, not a sworn deposition.

This is a very long poem, consisting of 295 lines in the 1985 edition. So it might help to first establish the narrative arc of the poem before digging down into specific lines, images, patterns, and themes. Dylan begins as a solitary and angry child, ripping up grass beside a railroad track near his aunt’s house. Before he becomes a singer or poet himself, he already begins to form certain artistic values in relation to beauty and ugliness. He rejects the conventionally beautiful in favor of what many consider ugly, but which he considers gritty authenticity.

These views harden into rigid principles as he begins playing music himself. He is forced to reconsider his philosophy, however, when he encounters Joan Baez. She is a kindred spirit to Dylan in many ways, and a formidable performer in her own right, but she sings with a much more conventionally beautiful voice. He is immediately drawn to Joanie as a person, but he puts up a wall of resistance to her music.

Eventually, on a fateful night at a party in Woodstock, he drinks enough wine to let his defenses slip. For the first time, he appreciates her voice as different than his, but no less valid artistically. This experience teaches him to open up, relax his former orthodoxy, and recognize that there are more forms of beauty than he was originally willing to admit.

The poem concludes with the poet envisioning his return to his hometown as a changed person. He plans to go back to the railroad track, but this time he vows not to tear at the grass but to show gentleness instead. He will shout out Joanie’s name to the passing train and follow his own path forward, informed by the lessons she has taught him, about music and about himself.

We know Dylan admires the Romantic poets, and this poem reflects that influence. As with the Romantics, everywhere the poet directs his gaze he sees the world mirroring back his inner state of mind. You might expect liner notes written for Joan Baez’s album to focus primarily upon her. Nope. There are a couple crucial sections about her in the middle of the poem. But he only mentions her by name once, and not until the final stanza. Dylan’s primary emphasis here is on himself, his growth, and his artistic development. After the pivotal Woodstock encounter, he adds her to the pantheon of influences “who taught me well / Not about themselves but me” (lines 212-13). The piece may be called “Poem to Joanie,” but an even more accurate title would be “A Self-Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man.”

Beauty and Ugliness

What does young Bobby learn about himself from Joanie?

The future poet and singer formed his first artistic principles around the paradox that ugliness is the true beauty. He learned this lesson from the railroad, and from Hank Williams songs about the railroad:

An’ my first symbol was the word “beautiful”

For the railroad lines were not beautiful

They were smoky black an’ gutter-colored

An’ filled with stink an’ soot an’ dust

An’ I’d judge beauty with these rules

An’ accept it only ’f it was ugly

An’ ’f I could touch it with my hand

For it’s only then I’d understand

An’ say “yeah this’s real” (57-65)

When Dylan moves to New York, the grungy city resonates with his inner impulses and steadfast rules about the beauty of ugliness: “‘The only beauty’s in the cracks an’ curbs / Clothed in robes a dust an’ grime’” (89-90). Dylan and the city speak to each other in the same voice:

The voice t’ speak for me an’ mine

Is the hard filthy gutter sound

For it’s only this that I can touch

An’ the only beauty I can feel (99-102)

Then Bobby meets Joanie. He identifies with her immediately in certain respects, but he remains fundamentally opposed to her beautiful voice:

A girl I met on common ground

Who like me strummed lonesome tunes

With a “lovely voice” so I first heard

“A thing of beauty” people said

“Wondrous sounds” writers wrote

“I hate that kind a sound” said I

“The only beauty’s ugly, man

The crackin’ shakin’ breakin’ sounds’re

The only beauty I understand” (120-28)

However, he gradually begins to reconsider his resistance. “‘But I’ll wait though ’til yer song is done / ’Cause there’s something about yuh / But I don’t know what’” (143-45). They spend some time together, and she moves him with her story “as a little girl in an Arab land” (153), presumably from the period when Baez’s father worked for UNESCO in Iraq and was a physics professor at Baghdad University. She recalls seeing dogs beaten to death in the streets, and one time she hid a dog in her house to try and save it. Her compassion impresses Dylan, and her gentleness stirs up old feelings of guilt about ripping up the grass, an act he now regrets as cruel destruction. She triggers a battle of conscience within the poet:

An’ I said softly underneath my breath

“Yuh oughta listen t’ her voice . . .

Maybe somethin’s in the sound . . .

Ah but what could she care anyway

Kill them thoughts—they ain’t no good

Only ugly’s understood” (170-75)

The stage is set for the Woodstock breakthrough. His growing sympathy for Joan as a genuinely caring person, combined with the effects of a lot of red wine, finally frees him up to really listen to her voice for the first time, unfettered by his biased presumptions about ugliness as the only acceptable form of beauty. Instead of grumbling, denouncing, and resisting her singing as he had in the past, he tells himself “Let her voice ring out” (199). Once he lets her voice in, he can’t get enough: “Don’ stop singing . . . sing again” (211).

Head and Heart

Dylan has the good sense not to replace one orthodoxy with another. He doesn’t go from exclusively appreciating conventional ugliness to exclusively appreciating conventional beauty. Instead he makes room for both, rejecting conventional thinking that imposes strict rules.

I did not begin t’ touch

’Til I finally felt what wasn’t there

Oh how feeble foolish small an’ sad

’F me t’ think that beauty was

Only ugliness an’ muck

When it’s really jus’ a magic wand

That waves and teases at my mind

An’ knows that only it can feel

An’ knows that I ain’t got a chance

An’ fools me into thinking things

Like it’s my hands that understand

Ha ha how it must laugh

At crippled one like me who try

T’ pick apart the sounds a streams

An’ pluck apart the rage ‘f waves

Ah but yuh won’t fool me any more (226-241, emphasis added)

This cryptic epiphany requires some unpacking. After rereading it many times, the words that stick out to me are the words think/thinking and try and pick apart and pluck apart on the negative side of the ledger, and the words magic and feel on the positive side of the ledger. Rather than making judgements about “good” and “bad” based upon restrictive aesthetic standards and moral categories, he learns to be more open-minded and big-hearted. The chief lesson young Dylan learned from Joan Baez was to rely less on intellect and more on intuition: to do less thinking and more feeling.

I get the sense that Bobby and Joanie were still having this long-running conversation with each other when they reunited for the Rolling Thunder Revue. In a striking scene from Renaldo and Clara, later incorporated in Martin Scorsese’s RTR film, the two former lovers ostensibly debate their former romantic relationship, but the language they use comes back to their larger tug-of-war between thinking and feeling:

DYLAN: It really displeases me that you went off and got married . . .

BAEZ: You went off and got married first and didn’t tell me.

DYLAN: Yeah, but I . . .

BAEZ: You should have told me.

DYLAN: But I married the woman I loved.

BAEZ: I know that’s true. That’s true. And I married the man I thought I loved.

DYLAN: See, that’s what thought has to do with it. Thought will fuck you up.

BAEZ: You’re right. I agree with that.

DYLAN: See, it’s heart, it’s not head.

Twelve years earlier in “Poem to Joanie,” Dylan credits Baez with teaching him to stop looking for definitive answers and start embracing mystery:

An’ like gypsy drums

An’ Chinese gongs

An’ cathedral bells

An’ tones ’f chimes

It jus’ held hymns ’f mystery

An’ mystery’s all too involved

It can’t be understood or solved

By hands an’ feet an’ fingertips

An’ it shouldn’t be called by a shameful name

By those who look for answers plain

In every book ’cept themselves (247-57)

Dylan and the Romantics

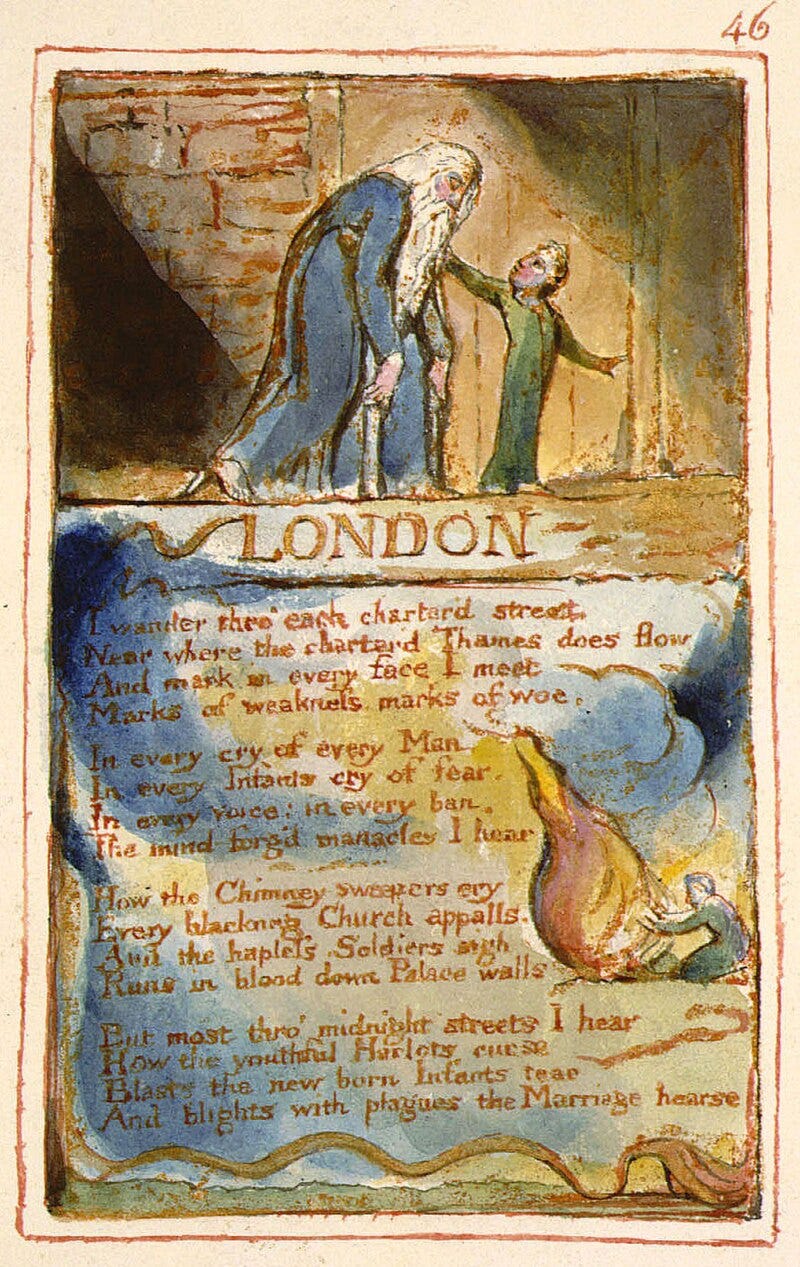

When I shared some of these ideas with the It’s Alright, Ma (I’m Only Reading) book club, Erin Callahan typed this phrase into the chat: “mind-forged manacles.” Bingo, Erin! That’s a phrase from the Romantic poet William Blake. It appears in “London,” one of the poems in Songs of Experience [cf. “I sing the songs of experience like William Blake / I have no apologies to make” in Dylan’s “I Contain Multitudes”]. Blake’s idea was that humans imprison themselves in the shackles of oppressive rules, limiting concepts, and cowering moral codes.

I don’t know when Dylan first familiarized himself with Blake, so I can’t say if he is drawing directly on the visionary Romantic in these liner notes. We do know how important Blake was to Dylan’s mentor and friend Allen Ginsberg, who recorded an entire album of dramatic readings of Songs of Innocence and Experience, including “London.” Shadow Chasing reader Ed Mulhall also drew my attention to Joan Baez’s recording of “London” on her 1968 album Baptism. In any case, Dylan certainly uses a lot of manacled prison imagery in “Poem to Joanie.” The work is filled with metaphorical bars, walls, fences, and locked cells.

In his youth Dylan describes himself as voluntarily shut off from the world, as if he has sentenced himself to solitary confinement:

’Til at last I backed so far away

From the world’s walls an’ friendless games

That I did not have a word t’ say

T’ anyone who’d meet my eyes

An’ I locked myself an’ lost the key (41-45)

Later he compares himself to “an arch criminal who’d done no wrong / An’ committed no crime but was screamin’ through the bars / A someone else’s prison” (84-86).

The “mind-forged manacles” about beauty and ugliness keep Bobby sequestered from Joanie when they first meet:

So between our tongues there was a bar

An’ though we talked a the world’s fears

An at the same jokes loudly laughed

An’ held our eyes at the same aim

When I saw she was set t’ sing

A fence of deafness with a bullet’s speed

Sprang up like a protectin’ glass

Outside the linin’ a my ears

An’ I talked loud inside my head

As a double shield against the sounds (129-38, emphasis added)

When Dylan has his breakthrough, the thing he’s breaking through are those self-constructed, self-policed prison walls:

Without one fence standin’ guard

When all at once the silent air

Split open from her soundin’ voice

Without no warnin’ from her lips

An’ by instinct my blood reversed

An’ I shook an’ started reachin’ for

That wall that was suppose t’ fall (190-96)

He hears her voice, and his prison cell dissolves: “She laughed out loud as ’f t’ know / That the bars between us busted down” (214-15). He shall be released.

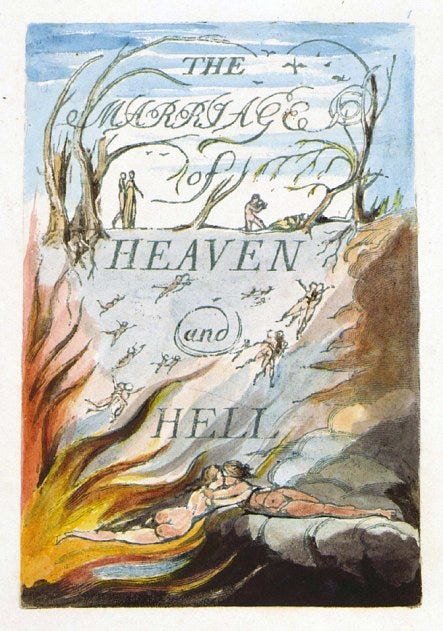

Now that Erin has put Blake on my radar, I find myself thinking about The Marriage of Heaven and Hell. Blake frequently sets up dialectical contests between oppositional forces, as in his dueling collections Songs of Innocence and of Experience, and in his provocative mixture of poetry, proverbs, and prose treatise The Marriage of Heaven and Hell.

In the world of rock music, the poem is most famous for this line: “If the doors of perception were cleansed everything would appear to man as it is, infinite.” Aldous Huxley echoed this verse in the title of his book on experimenting with psychedelics, The Doors of Perception, which in turn provided Jim Morrison the name for his band The Doors. Morrison seemed to lead his life by one of Blake’s proverbs: “The road of excess leads to the palace of wisdom.” But Dylan’s connection to Blake is more about competition of contrary forces and rebellion against obedient conformity.

Early in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, Blake lays out his premise:

Without contraries is no progression. Attraction and repulsion, reason and energy, love and hate, are necessary to human existence.

From these contraries spring what the religious call Good and Evil. Good is the passive that obeys reason; Evil is the active springing from Energy.

Good is heaven. Evil is hell.

But Blake doesn’t follow the accepted path of simply defending Good and denouncing Evil. Milton tried that in Paradise Lost but ended up building the opposite case in spite of himself. Blake asserts, “The reason Milton wrote in fetters when he wrote of Angels and God, and at liberty when of Devils and Hell, is because he was a true poet, and of the Devil’s party without knowing it.”

Blake stages debates between angels and demons in which the devils not only make the more persuasive arguments, but they also seize the higher moral ground. At one point, the Devil even drafts Jesus onto Team Hell: “I tell you, no virtue can exist without breaking these ten commandments. Jesus was all virtue, and acted from impulse, not from rules.”

If that sounds to you like the lesson Dylan learns from his encounter with Baez, then we’re tuned into the same wavelength. “Poem to Joanie” reads to me like Dylan’s restaging of The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, with Joanie as celestial angel and Bobby as the diabolical demon child.

Dylan uses that precise term to describe himself in the first stanza: “An’ I sung my song like a demon child / With a kick an’ a curse / From inside my mother’s womb” (34-36). He returns to that image in the final stanza, imagining his return to the poem’s beginning: “An’ I’ll stand up an’ remember when / A rock was flung by a devil child” (286-87). Along the way, the poet and singer learns to “act from impulse, not from rules,” as Blake put it. But that doesn’t mean Dylan switches from Team Hell to Team Heaven. He is still a rebel, like the first rebel Lucifer: “An’ I’ll sing my song like a rebel wild / For it’s that I am an’ can’t deny” (290-91). What he has learned is to reconcile the Angel and the Devil, a marriage of Heaven and Hell.

I’ll leave you with a final image from another Romantic poet, Samuel Taylor Coleridge. In Dylan’s recent interview with Jeff Slate, he claims to have turned to Coleridge during the pandemic: “I reread ‘Rime of the Ancient Mariner’ a few times over. What a story that is. What a poem. If there’d been any opium laying around, I probably would have been down for a while.” I hear echoes of a different Coleridge lyric in “Poem for Joanie,” one famously inspired by a laudanum-induced hallucination or dream: “Kubla Khan.” Its subtitle is “Or, a vision in a dream. A Fragment.” [Come to think of it, “A Vision in a Dream” could have made a good subtitle for Dylan’s bootleg release Fragments.]

Even if you don’t know the poem, you might recognize it from the opening of Orson Welles’s Citizen Kane: “In Xanadu did Kubla Khan / A stately pleasure dome decree.” This ornate palace sits gloriously in the sun above ground, but the poet follows the sacred river Alph to the mystifying ice-lined caverns underground. What does he find there? “A savage place! as holy and enchanted / As e’er beneath a waning moon was haunted / By woman wailing for her demon-lover!”

After rereading “Poem to Joanie” many times, like Dylan reread Coleridge during the pandemic, I feel like I’ve entered an opium dream, where visions intermingle and characters exchange identities. “Kubla Khan” closes with a vision of “a damsel with a dulcimer” singing to her demon-lover, a poet with “flashing eyes” and “floating hair.” I’ll be damned (to Blake’s Hell please!) if they don’t look a helluvalot like Bobby and Joan, though I’ll leave it to you which is the Angel and which the Devil:

A damsel with a dulcimer

In a vision once I saw:

It was an Abyssinian maid

And on her dulcimer she played,

Singing of Mount Abora.

Could I revive within me

Her symphony and song,

To such a deep delight ’twould win me,

That with music loud and long,

I would build that dome in air,

That sunny dome! those caves of ice!

And all who heard should see them there,

And all should cry, Beware! Beware!

His flashing eyes, his floating hair!

Weave a circle round him thrice,

And close your eyes with holy dread

For he on honey-dew hath fed,

And drunk the milk of Paradise.

Just a quic note to thank you, again, for drawing our attention to this interesting poem! I will savor your post over the next few days.

To me Dylan is all about duality. I have read this poem several times but did not know the literary references. Gates can keep you locked up or open a way in as he says when talking about his sculpture. The goddess and the whore, sin and redemption,

beauty and ugliness. This juxtaposition is his reoccuring artistic and poetic theme, and also a judgement of sorts in trying to reconcile the collision of opposites. His ongoing search to find his "twin" seems like he's seeking non duality at the same time. 🤷🏻♀️

You guys are all so smart and literary! Unfortunately I don't have that foundation.