Have you seen this woman?

According to Wikipedia’s entry on “Sweetheart Like You,” “The video shows Dylan and his backing band on a bar stage performing after hours while being watched by a female janitor (also played by Dylan) cleaning up the bar.” Say what!? The anonymous author offers no citation to support this claim.

I’ve watched the video multiple times, paused on the scenes with the custodian, and stared at the screen until my eyes glowed like an idol with an iron head. I just don’t see it. The eyes, the facial features, the neck—none of it looks like Dylan to me. Of course, makeup crews can work wonders, so I can’t completely discount the possibility that it’s Dylan in drag. If any Shadow Chasing readers have an inside scoop on who plays the custodian in this video, I’m eager to hear it. But I don’t think it’s Dylan.

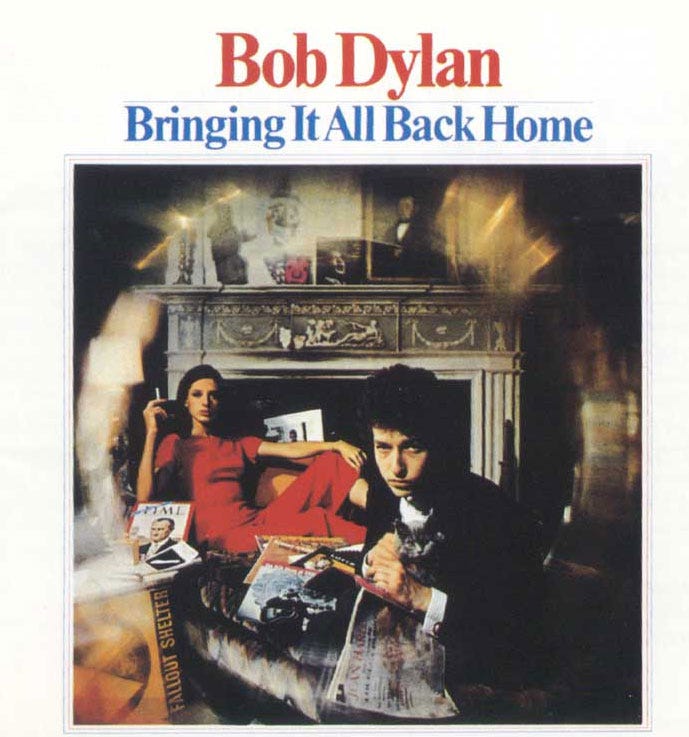

Here’s the thing, though: I so want it to be Dylan! Now I know how that first generation of fans must have felt back in 1965, gazing at the cover of Bringing It All Back Home and convincing themselves that the woman in red must be Dylan in drag. Did Sally Grossman have an alibi for her whereabouts during the shooting of this video?

Dylan in drag would reinforce a recurring pattern where he identifies so closely with a woman that distinctions between them blur and he sees himself reflected in her. Think “Visions of Johanna”: “She’s delicate and seems like the mirror.” Think “Simple Twist of Fate”: “I still believe she was my twin.” Think “When the Night Comes Falling from the Sky”: “In your teardrops, I can see my own reflection.”

Combine these mirror reflections with references to drag sprinkled throughout his work [e.g., “Ballad of a Thin Man,” “Temporary Like Achilles,” and all the old queens, from “Queen Jane Approximately” and “Just Like a Woma through “I Contain Multitudes”]. Then mix in Dylan’s identification with burlesque [“When you’re up on stage, and you’re looking at a crowd and you see them looking back at you, you can’t help but feel like you’re in a burlesque show” (Gates 1201)]. And voilà! Wikipedia’s unconfirmed assertion that Dylan played both the man strutting his stuff on stage and the woman staring back at him, locking gazes in what amounts to a self-serenade, isn’t so far-fetched after all. It’s such a perfectly Dylanesque idea that I’m disappointed if that’s not him in drag. (But I still don’t think it is.)

“Sweetheart Like You” is one of the songs routinely trotted out as proof of Dylan’s sexism, particularly the lines:

You know, a woman like you should be at home

That’s where you belong

Watching out for someone who loves you true

Who don’t know how to do you wrong

Sounds like a very old-fashioned, stereotypical view that a woman’s place is in the home, right? But there’s a lot more to the song and video than this one section, taken in isolation, might suggest. The more homework I do on “Sweetheart Like You,” the more complicated and interesting it becomes. Let me share some of the best insights I’ve gained from others in my research into this song.

Women and Dylan

I have learned more from Laura Tenschert on this subject than from anyone else. As readers of Shadow Chasing probably know, she is one of the premier feminist scholars working in Dylan Studies today. I’m also fortunate to count her as a good friend. When it comes to “Sweetheart Like You,” she’s the teacher and I’m the student.

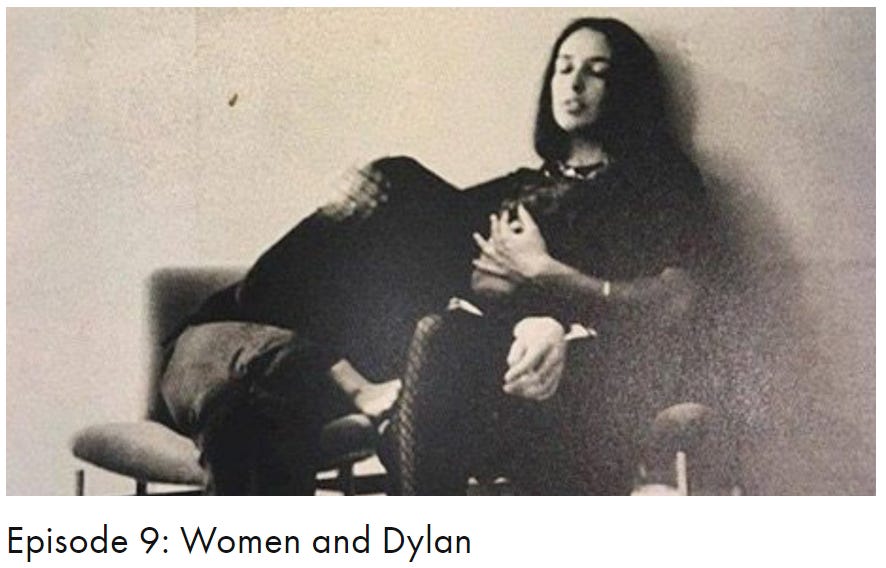

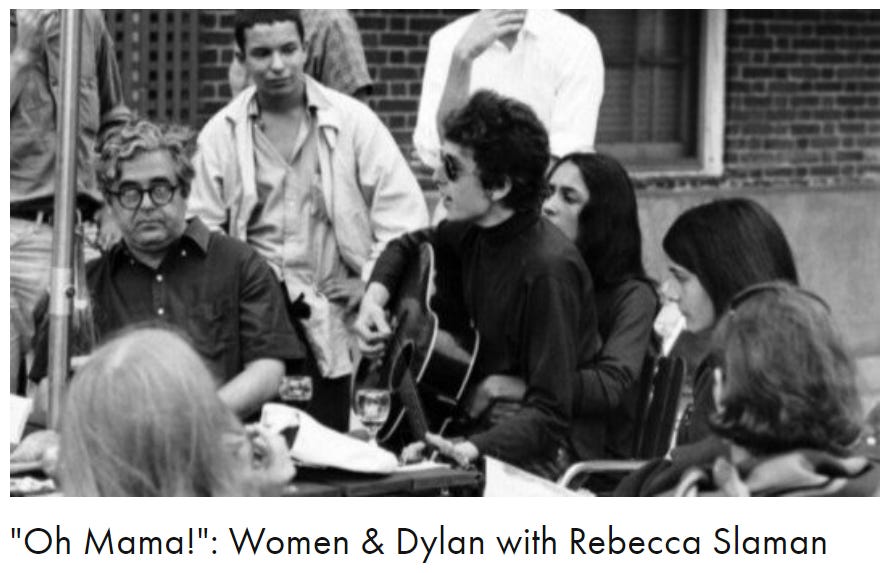

Laura has produced two episodes of Definitely Dylan called “Women and Dylan,” the first a radio show that aired in the spring of 2018, and the second a podcast conversation with her pal (and mine) Rebecca Slaman posted in the summer of 2023. “Sweetheart Like You” features prominently in both.

In the 2018 episode, Laura observes,

The scene in the song is of a man talking to a woman in some “dump”: a dive bar perhaps, a backroom poker game, a strip club. But the way I see it when I hear it is like a scene in a black & white noir film from the 1940s, where Humphrey Bogart walks up to some beautiful damsel, maybe offering her a light or striking up a conversation.

Her instincts are spot on. Michael Gray confirms that the refrain “What’s a sweetheart like you doin’ in a dump like this?” echoes a line from a Bogart film. Compare Dylan’s line with that of Gloves Donahue, Bogie’s character in All Through the Night (1942): “What would a sweetheart like that Miss Hamilton dame be doing in a dump like this?” (qtd. Gray 557).

The effect for Laura is one of parody: “I think it’s old-fashioned to the point where I almost can’t take the singer (or the ‘I’ in the song) seriously—beyond seeing him as a sketch or a caricature of an old-fashioned man.” I think there are additional targets of parody and satire at work in “Sweetheart Like You,” too, and these are accentuated in the video. But first let’s dig deeper into Laura’s interpretation.

She offers this provocative thesis: “I hear something that might be surprising to many people who condemn this song. I feel like this song is actually quite an accurate description of what is traditionally expected of a woman in a patriarchal society. The ‘dump,’ where women don’t belong, is the place where important men congregate.” She quotes the line, “You got to be an important person to be in here, honey / You got to have your own harem,” and then explains: “The woman’s space is either in the home or in the harem. But always in subservience to the man, and always excluded from power herself. Rather than being judged on her work, or the merits of her work, she’s always judged on her looks.”

It’s a striking claim. Rather than hearing the song as the relic of an antiquated system of beliefs about women, Laura hears “Sweetheart Like You” as a critique of those values. This isn’t merely an intellectual exercise for women listeners but a commentary on experiences they’re all too familiar with: “Lastly, and this is probably something that quite a few women might recognize, she can’t even have a bloody drink in a bar without some well-meaning guy walking up to her and telling her what she should do with her life.”

Laura returns to “Sweetheart Like You” in 2023 and builds upon her original interpretation. Her guest takes the first swing at the song. Rebecca Slaman quotes the notorious lines about a woman’s place being in the home, but then she offers an alternative reading. She reminds us of the setting in a shady pickup bar. In that context, perhaps the singer is essentially saying: “I’m looking out for you, sister. A woman like you should be away from this nonsense. He’s treating her like a queen.” Interesting perspective. As Rebecca hears it, rather than being one of the barflies buzzing around this sweetheart, the singer is a swatter shooing away these pests and looking out for her best interests. Viewed through this lens, “Sweetheart Like You” comes across more like “To Ramona.”

Laura’s leaping off point is the line: “You know you could be known as the most beautiful woman who ever crawled across cut glass to make a deal.”

Take in that line. What he’s saying is actually crazy! You could crawl across cut glass to make a deal—and all you would be known for is the most beautiful woman who ever did that! Even if you did something like that, you would still be reduced to your looks. That’s a crazy statement, and one that I actually think goes so far beyond the possible chauvinism of that other line. I think that it nails something about women’s role in society.

Laura’s passion for this argument hasn’t waned in the five years since she first formulated her revisionist thesis of “Sweetheart Like You” as a critique of patriarchy. What has changed, or rather deepened, is her appreciation for the cultural context in which Dylan offers this critique.

Inspired by Karina Longworth’s podcast You Must Remember This, focusing on erotic thrillers from the eighties and nineties, Laura situates “Sweetheart Like You” within the gender dynamics of its era: “This was in the early eighties. After second wave feminism, there was this idea about women entering the workplace, but they were facing all sorts of harassment—and they were also still expected to take care of the home. I think that’s kind of in that song as well: What is a woman’s role now in the early eighties?”

That’s a really perceptive insight, and it reminds me of other cultural touchstones at the time. Viewed in this light, I see a family resemblance between “Sweetheart Like You” and Dolly Parton’s “9 to 5.”

You’ll remember this as the hit theme song for the film of the same title, starring a trio of bad-ass women: Dolly, Jane Fonda, and Lily Tomlin. 9 to 5 premiered in 1980 and reflects major social and equity concerns of the times, both in terms of the women’s liberation movement and the “Moral Majority” backlash of conservative family values.

But 9 to 5 isn’t just a period piece from a bygone era. The stage musical adaptation has enjoyed a resurgence of popularity since the #MeToo movement, reminding the world that problems facing women in the workplace 40+ years ago still remain perniciously relevant today.

Looking at other lyrics from “Sweetheart Like You,” Laura notices this:

It’s also really interesting how he positions himself in that world, not the singer but Bob Dylan. Because he says, “You got to be an important person to be in here, honey.” And then it gives three options of what you could have done. Either you’ve got to have done some evil deed, or you’ve got to have your own harem, or you’ve got to play your harp until your lips bleed—like an act of self-mutilation, self-sacrifice. Which is also related to the crawling across cut glass, right? Both need to bleed in order to be there. I think that’s quite powerful imagery.

This keen observation suggests identification between the singer and the sweetheart he addresses: both have sacrificed for their work, bled for their art.

I’m reminded of an insight from earlier in the episode where Laura compared Joni Mitchell and Bob Dylan as different types of songwriters. Mitchell has pointed out in interviews that she embraces the autobiographical nature of her songs and confronts that confessional material directly in first-person voice. Dylan, on the other hand, tends to externalize his personal songs by projecting them onto another person addressed as “you.” Maybe the same dynamic is at play in “Sweetheart Like You.” On some level, Dylan may be talking to himself, giving the advice he wishes he had received when he was new to the game. This strategy of replacing “I” with “you” can seem like a protective deflection, but it’s also a rhetorical and psychological move that breeds empathy, in this case with women who have been mistreated and exploited by the music business.

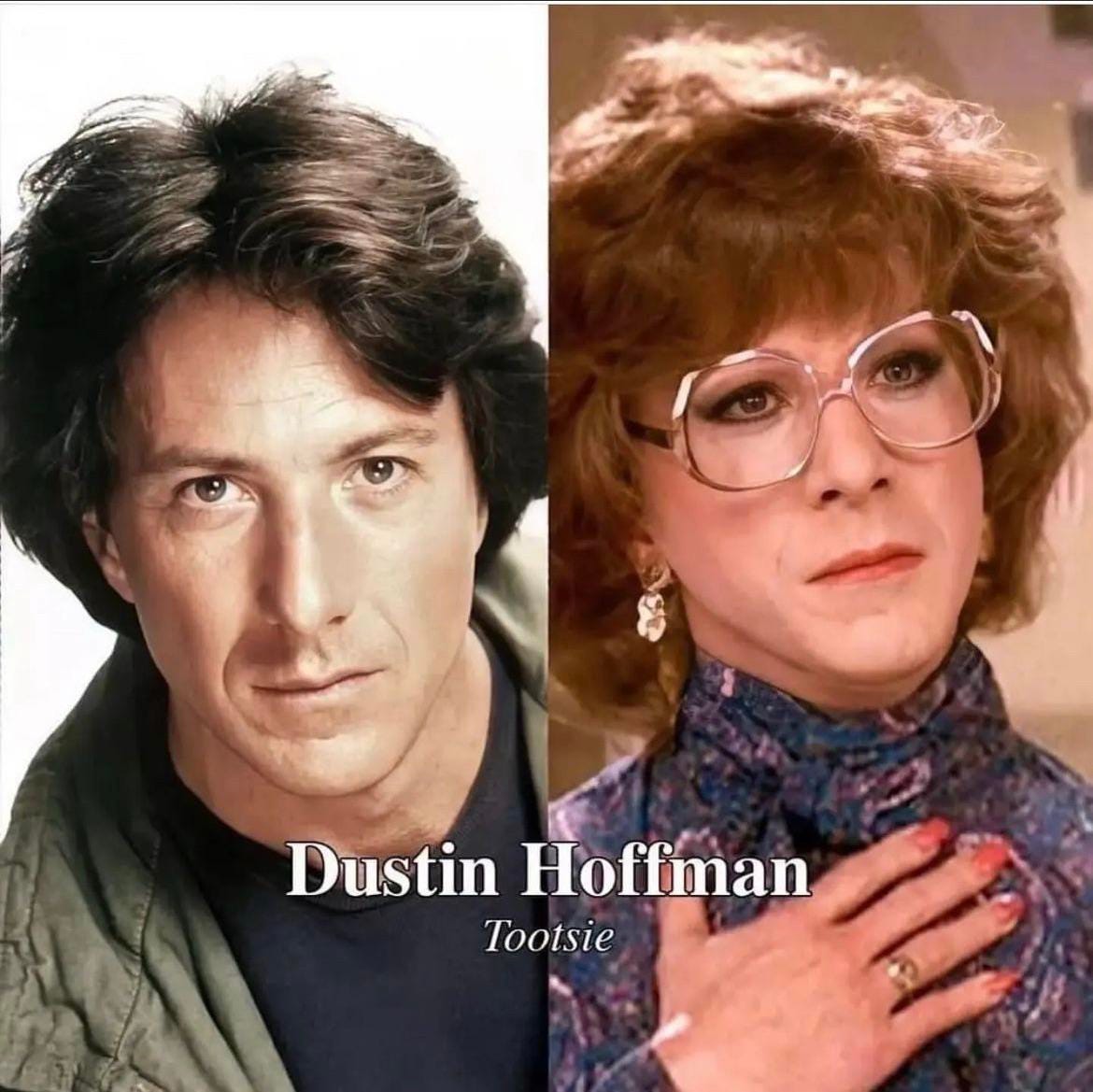

This notion of identification between I and You, between the singer and the woman he addresses, or even between Dylan on stage in the video and the woman custodian off stage, reminds me of another iconic film from around this time: Tootsie, starring Dustin Hoffman.

Hoffman plays Michael Dorsey, a struggling actor who lands a role in a hit soap opera by pretending to be a woman and dressing in drag. He takes on the role of Dorothy Michaels, whom he plays as an outspoken feminist. He becomes very close to his co-star Julie (played by Jessica Lange), but their relationship falls apart after Michael’s fraud is exposed. Near the end of the film, he tries to explain the inner transformation he underwent during his cross-gender performance as a woman: “I was a better man with you . . . as a woman . . . than I ever was as a man . . . with a woman. […] I learned a few things about myself being Dorothy, Julie. I just have to learn to do it without a dress.”

Tootsie is a comedy, and certain scenes and speeches now come across as cheesy or in poor taste. Those valid criticisms notwithstanding, the film is another example to support Laura’s argument that “Sweetheart Like You” emerges from a specific cultural context in the eighties. Along with 9 to 5 and Tootsie, I would add works like La Cage Aux Folles (1978), Victor/Victoria (1982), and Yentl (1983) as other prominent films that explore the shifting roles of women through the vehicle of cross-gender performance. I haven’t listened to Karina Longworth’s podcast yet, but I’m sure she provides lots of other examples.

In their 2023 “Women and Dylan” discussion, Rebecca is damn impressed by Laura’s interpretation of “Sweetheart Like You”: “Yeah, you just kind of unlocked it for me. That is amazing!” Laura admits, “I think I just unlocked it for myself.” Rebecca connects this conversation about “Sweetheart Like You” to a lively panel on Dylan in the eighties at the 2023 World of Bob Dylan conference in Tulsa. “So many people were like, ‘You don’t understand—the eighties were terrible!’ And I’m like, ‘I do understand—that’s why you guys hate it so much!’ That’s why there’s so many negative reactions to Dylan in the eighties.” However, Rebecca then adds this very shrewd observation: “This is a perfect example of Dylan taking in the world that he’s living in, which he does very well at every point in his career, and synthesizing it into great art about the time.” Amen, Rebecca!

By the way, the sponsors of that great panel—the dynamic duo of Erin Callahan and Court Carney—are teaming up for a collection of essays reconsidering Dylan’s work from the eighties. It’s becoming apparent that we’ve overlooked and underestimated some major Dylan achievements from that decade, including “Sweetheart Like You.”

The Video

As I suggested in the introduction, there’s more going on in the video than immediately meets the eye. Not counting the Andy Warhol short film of “Subterranean Homesick Blues” or various other live performances captured on film, “Sweetheart Like You” was Dylan’s first official video in the MTV sense of the genre.

Terry Gans interviewed the video’s director Mark Robinson for his book Surviving in a Ruthless World: Bob Dylan’s Voyage to Infidels. According to Robinson, “Dylan was involved in the creative decisions, production decisions and editing. However, trying to get to decisions ‘was like nailing Jello to the wall,’ according to the director. ‘The way I approached it was to give three options each for concept, wardrobe, staging, etc. This allowed for Dylan’s unique creativity and also gave some structure to the process’” (214). It sounds like working with Dylan was an exasperating experience for Robinson. But Gans confirms that Dylan was centrally involved in the creative vision of the video. Therefore, when we see what looks like Dylan’s idiosyncratic signature on this performance piece, we know it’s no forgery.

The video was supposed to be quite different than what they ultimately released.

The original concept, as rumored in 1983, was for a number of women to portray the “Sweethearts.” All would have on the same outfit but be different women. One idea was that each would morph into having the same face. “It was to be a performance piece,” said Robinson, “with secondary interactions (with the women). But it just wasn’t working” (Gans 214-15)

Although the creative team abandoned the initial concept, they seem to have retained the concept of “morphing”; that is, of portraying figures who merge with or transfigure into each other.

Morphing is also the language of dreams. This becomes a very different video when you translate it into that language. Maybe we’re meant to understand the entire action as taking place in the mind of the custodian. As she goes about the drudgery of her nightly tasks, she becomes lost in reverie, slips into dreams. She imagines the singer into existence as an antidote to her loneliness, a wish fulfillment fantasy of a man who sees her in a sympathetic light.

In 2021, Harold Lepidus interviewed Carla Olson, who plays a guitarist in Dylan’s (fictional) band for the video. She shares a number of interesting anecdotes from the 23-hour shoot. For instance, she mentions how finicky Dylan was about his wardrobe. According to Olson, he eventually went to Robinson and asked to borrow his black leather jacket, which is what Dylan ended up wearing in the video. Gans confirmed this story with the director. Perhaps it’s just another example of the star’s fickle fashion sense. But I wonder if the wardrobe adjustment represents a more calculated aesthetic decision.

Note that the black jacket over a white shirt worn by Dylan matches the outfit worn by Olson. There’s also visual symmetry on stage between the white and Black performers on the left (Clydie King and Dylan) and on the right (Olson and Robbie Shakespeare), but the genders are reversed. These juxtapositions seem intentional to me, not arbitrary, and they contribute to the mirroring and morphing dynamics pervasive throughout the video. Keep in mind, too, that there is a form of cross-gender impersonation going on when Carla Olson mimes the guitar solo at the end, which was actually played by Mick Taylor on the record.

The visuals are complemented by lyrics in “Sweetheart Like You” that play with gender. The best example is: “You know, I once knew a woman who looked like you / She wanted a whole man, not just a half.” Hearing Dylan sing these lines while the camera moves in on the cleaning woman practically begs for a drag interpretation.

Later in this same verse, there’s reference to a “queen.” On the surface, this seems to refer to a con man who is dealing from the bottom of the deck. In the present context, however, it’s awfully tempting to hear a drag queen connotation: “In order to deal in this game, got to make the queen disappear / It’s done with a flick of the wrist.” Is the “queen” on screen disappearing? No, quite the opposite: she is given her moment in the spotlight, albeit off stage with a mop rather than a scepter in her hand. I think we can number this custodian among “All the old queens from all my past lives” that Dylan sings about almost forty years later in “I Contain Multitudes.”

Once upon a time Queen Sweetheart might have dressed so fine, but now she seems to be scrounging for her last meal. That hairdo and makeup ain’t doin’ her any favors either. She looks for all the world like an aging queen in a bad wig and greasepaint, no longer on the performance bill, reduced to cleaning up after the other divas. The visual effect is one of exaggerated artifice, the kind of campy caricature one associates with burlesque and drag.

To be fair, the custodian isn’t the only one with a mop. Get a load of Dylan’s hair.

Gans asked Robinson about this unusual look, and here’s what he learned:

Dylan was in total control of how he looked, and, according to Robinson, was specific about his hair and makeup. The look itself is unlike any Dylan seen before or since. His hair is poofed and down low on his forehead. And most odd, his eyebrows have been enhanced to the degree that the appearance is that of a werewolf the evening of a full moon. (215)

I know it was the decade of bad hair, but damn! My 12-year-old sister could have done a better job with her Clairol hot curlers and a can of Aqua Net in 1983. The more I think about it, though, the more I’m convinced that the whole point was to make the frontman of this fake band look artificial, like a cut-rate Dylan impersonator. What I see on screen is one disheveled queen staring down another.

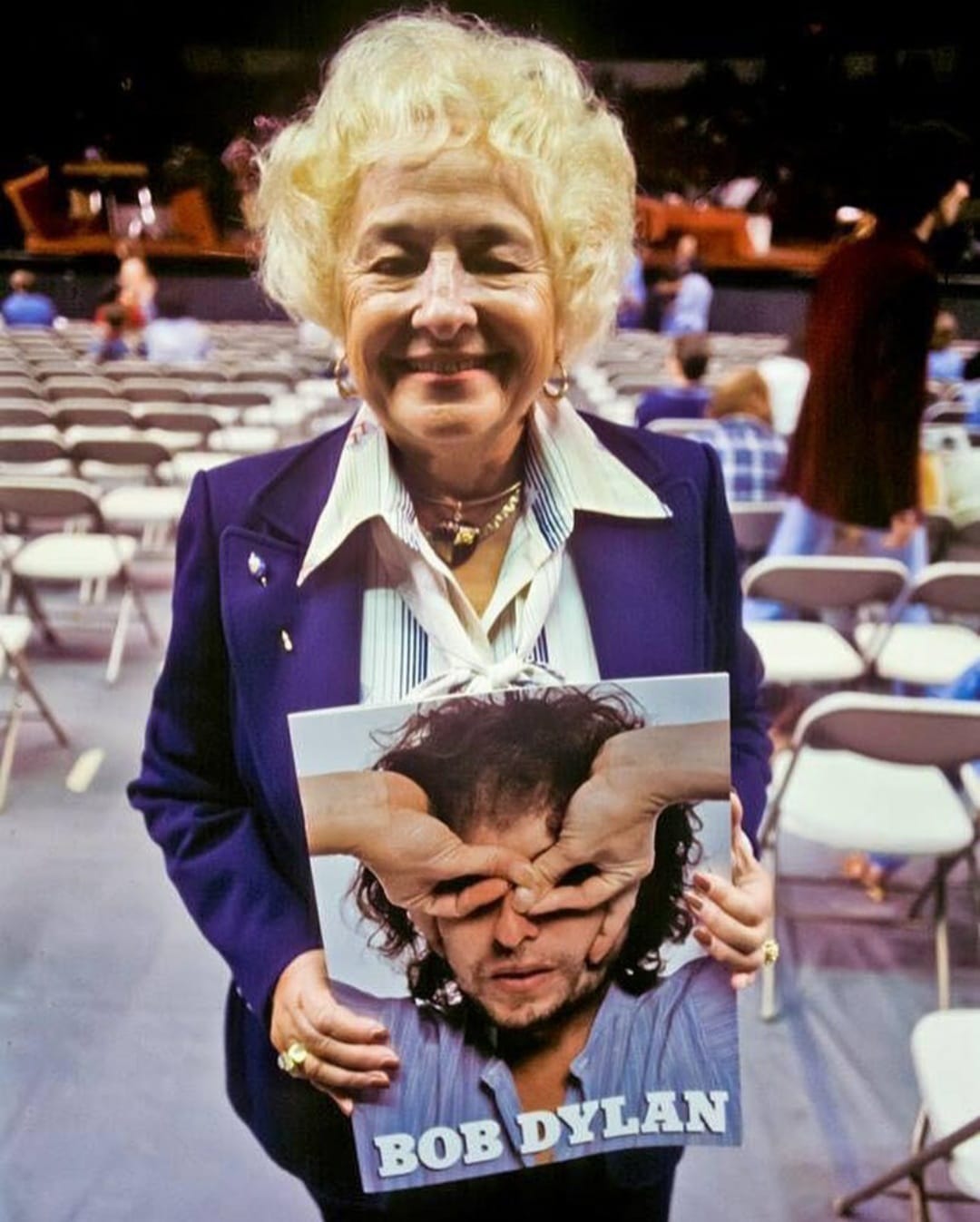

The heart of the “Sweetheart” video is the cleaning woman. She is also its central mystery. As Gans notes, “There has been a lot of speculation over the years about the identity of the woman. One school of thought is that it was Dylan’s mother Beattie [sic]. Some think it’s Dylan” (215). Ooh! Beatty would be a fascinating casting choice. I do see a resemblance.

But Robinson dismisses such fanciful speculations: “‘The casting was . . . she was just an actress with an interesting face,’ according to Robinson with no doubt or equivocation” (Gans 215). Maybe so. Personally, I still find that following these leads makes for a worthwhile investigation. The search might not lead to definitive answers, but these questions help unlock the song, to borrow Rebecca’s phrase.

Commenting on Dylan’s wolfish look, Gans editorializes: “This significantly detracts and distracts from the story being presented (author’s opinion)” (215). I disagree. I’ve come to regard the vulgarities of this video as integral to its larger creative vision: a satire of the form itself.

“Sweetheart Like You” isn’t a bad video so much as a metacommentary on bad videos, a winking critique of the market-driven forces that compel artists to make such travesties.

Dylan said no to Ed Sullivan in 1963, but he felt compelled to say yes to MTV in 1983. Does that mean this video is evidence of him caving into commercialism? You could see it that way, but you’d be missing part of the bigger picture. If he’s going to get pressured into making this trivia, then he’s at least going to have some fun by mocking the excesses of the genre. You want me to mug and wiggle for the camera while pretending to sing my song? Fine, I’ll play the game. But I’ll do it as burlesque, as self-parody, a lampoon of the degrading things the music business demands of its exploited artists.

Foremothers

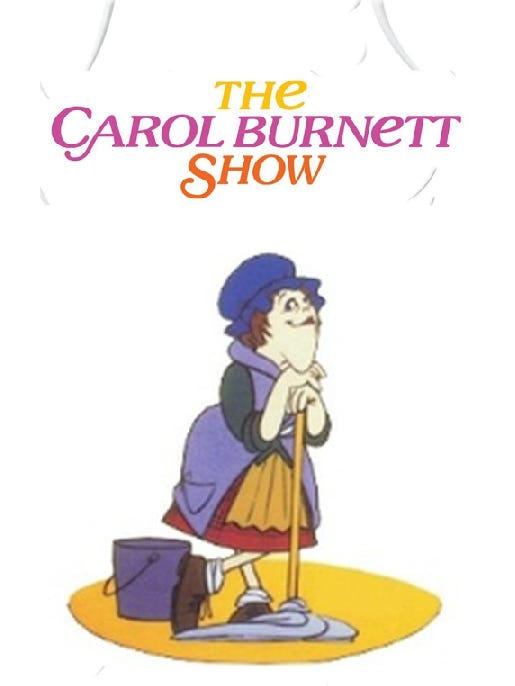

When I was a kid, I loved The Carol Burnett Show. Variety shows and sketch comedies were very big in the seventies, so there was lots of competition for viewers, but Burnett was the queen of the genre. Her show remained very popular through reruns well into the eighties. The comedian was a chameleon, adept at playing countless memorable roles, from Scarlett O’Hara to Queen Elizabeth, from Eunice Higgins to Mrs. Wiggins—we roared with laughter at them all.

But Burnett also had a lovely singing voice, and she could tug at your heartstrings with sentimental ballads, too. The best example is her most iconic recurring character: the charwoman. In the context of 1983, it’s hard to imagine that Dylan and Robinson didn’t have this character in mind as a prototype for the custodian.

In an interview with Alice George for a Smithsonian exhibition of her work, Burnett reflected on the inspiration behind the charwoman. The interviewer sets the stage with a description that might just as well apply to the custodian in Dylan’s video: “In a typical charwoman scene, she would enter the set, dragging her bucket and mop. Something would spark her imagination, and she’d reveal her dream in pantomime.”

Burnett claims that she got the idea for the character while listening to David Rose’s 1962 song “The Stripper”: “I was listening to it on the radio this one afternoon, and the disc jockey who was going to play it said, ‘This is the housewives’ favorite song,’ so I pictured a housewife, quote-unquote, ironing or sweeping or vacuuming, but doing The Stripper’s walk like she was Gypsy Rose Lee or somebody.” From there, the housewife morphed into a cleaning woman mopping up a burlesque house after a show, imagining her way into the erotic performances that took place nightly on the stage. Sound familiar?

Burnett created the bit as a piece of farce, but over the years she came to identify with the charwoman as an avatar for her own character transformations in the variety show. She sometimes sang her closing theme song, “I’m So Glad We Had This Time Together,” in the guise of the charwoman, and she adopted the character as the logo for The Carol Burnett Show.

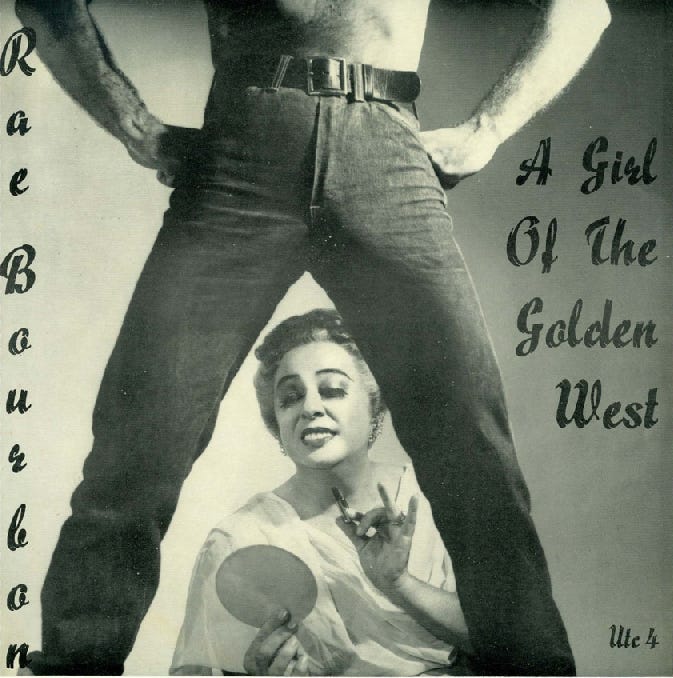

While doing research for this piece, I came across a fascinating alternative theory about the source for Burnett’s iconic character. On his website Don’t Call Me Madam: The Life and Work of Ray Bourbon, Randy Riddle reports that Carol Burnett may actually have gotten the idea for her charwoman character from the Mop Lady, a recurring character played by drag performer Ray (or Rae) Burton.

Bourbon was a drag performer for decades. He was part of the so-called “Pansy Craze” back in the twenties and thirties, he toured with traveling burlesque revues all over the country, he owned a popular Hollywood nightclub called The Rendezvous in the forties, and he released several albums of risqué material in the forties and fifties.

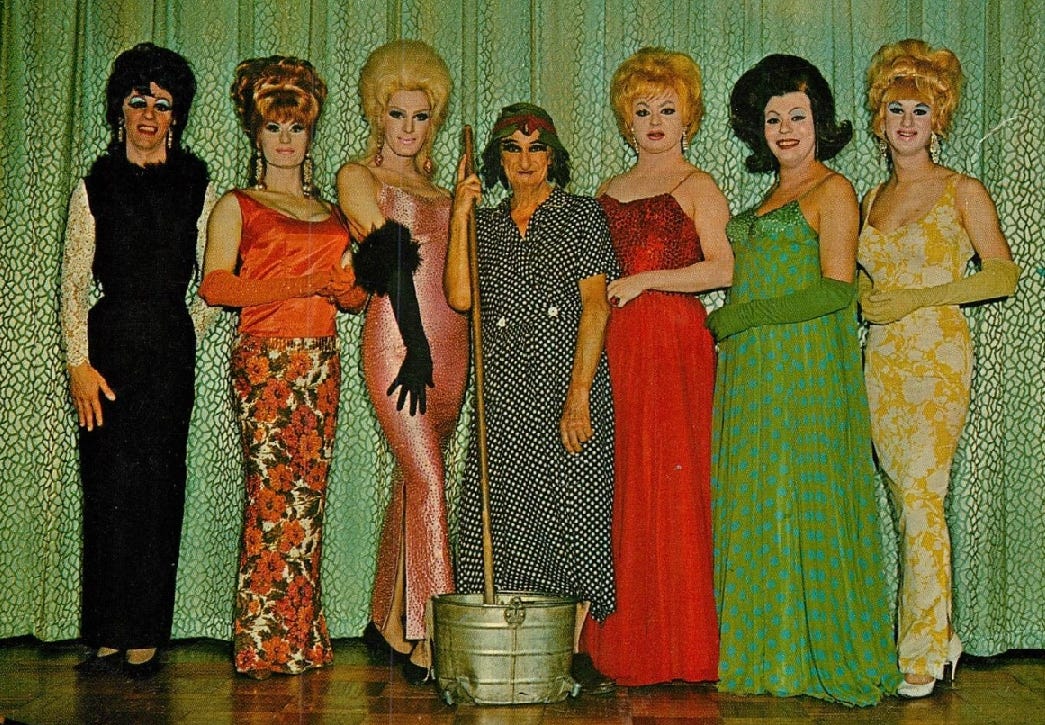

One of Bourbon’s most popular characters was called Mavis, generically referred to as the Mop Lady. At the end of a drag show featuring luxuriously dressed prima donnas, Bourbon would return to stage in the guise of a humble custodian, pretending to clean up the mess made by the performers and heckling the audience.

Riddle quotes Jack Ames, a bartender at the Jewel Box in Kansas City where Bourbon’s troupe performed many times. Ames describes the Mop Lady schtick:

The best part of the show was at the end. All the others had left the stage and Rae, [came out] dressed as the cleaning lady in an old dress and foul mouth. The departing audience, many of them, didn’t realize it was the same person who had been causing them so much merriment before. She threw the bucket down on the stage, started mopping, mumbling about having to clean up “after those bitches.” Then stood there, mop in one hand, other hand on hip & delivered a 10-15 minute little post script, all ad lib and just so funny!

According to some of Bourbon’s collaborators, members of Burnett’s creative staff were frequent patrons of the Jewel Box, and some allege that they ripped off Bourbon’s Mop Lady for Burnett’s charwoman. She premiered her character in 1962; Bourbon had been doing the bit since the 1930s. Riddle spreads the rumor but then dispels it. He suspects that Bourbon and Burnett were both drawing upon older stock characters from vaudeville, music hall, and burlesque as inspiration for characters that they each adapted and made distinctly their own.

Likewise, I think the cleaning woman in Dylan’s video is a composite drawn from many sources. Burnett’s charwoman must be one of them: the similarities are unmistakable, and the image was too ubiquitous to escape notice. But I love the idea of another illicit underground progenitor hiding in the family tree. Given the gender-bending dynamics of the song and video, it’s appropriate, illuminating, enriching, and utterly fabulous to think that Rae Burton’s Mop Lady in drag could be one of the foremothers of “Sweetheart Like You.”

Another ancestor for “Sweetheart Like You” can be found in that great genealogy book Chronicles. Think about the video scenario: Dylan stands on stage and sings the song directly to a silent cleaning woman off stage. She stops her mopping and listens intently, lost in fantasy, guided by voices and visions. It strikes me that we’ve seen this scene before in Dylan, but with the roles reversed.

Young Bob Dylan sometimes accompanied girlfriend Suze Rotolo to her workplace at the Theatre de Lys on Christopher Street (now the Lucille Lortel Theatre). In late 1961 or early 1962, he was in the auditorium for Brecht on Brecht. He was bowled over by Lotte Lenya’s performance of “Pirate Jenny,” about a hotel maid who imagines herself a pirate queen and fantasizes about revenge against the rich gentlemen who treat her like garbage. Back then, Dylan was the silent spectator and the cleaning woman was the one on stage singing to him in the darkness.

In Chronicles, he recaptures this seminal moment of identification with Lenya’s “Pirate Jenny.” As he listened, he “got tuned in to the point of view of the maid, where she’s coming from, and it’s the driest, coldest place. Her attitude is so strong and burning. ‘The gentlemen’ who she is making up beds for have no idea of the hostility inside her […]. The scrubbing lady is powerful and she’s masquerading as a nobody—she’s counting heads” (274).

Read Dylan’s account of the scrubbing lady in “Pirate Jenny,” and then watch the video again for “Sweetheart Like You.” I had long assumed that the video was an overly literal illustration of the lyrics: the custodian is the “sweetheart,” and the singer asks what she’s doing in a dump like this bar. He shows sympathy for her, so I presumed that she likewise appreciated his concern. Does she though?

She never cracks a smile, nor does she show any visible signs of affection. If the scene is real, she might well be thinking, “When the hell are these freaks gonna get lost so I can finish my job and get home?” If it is imaginary, she might be remembering with bitterness the dignity and opportunities that have been denied her in a patriarchal society and ruthless capitalist system. Either way, the sentimentality I initially gleaned from the video may have been wishful thinking on my part. The custodian might just as well be counting heads like Jenny.

When Dylan first saw Lotte Lenya perform this song in the early sixties, he wasn’t a rich rock star. His daily reality mirrored Jenny’s economic deprivation, professional insignificance, and personal indignation. The song hit home. It also inspired him as a paradigm for effective songwriting and live performance. He recalls, “I’d think about this later in my dumpy apartment” (276). Oh, dumpy was it? Well, what’s a sweetheart like you doing in a dump like that, Bob?

I hadn’t done anything yet, wasn’t any kind of songwriter but I’d become rightly impressed by the physical and ideological possibilities within the confines of the lyric and melody. I could see that the type of songs I was leaning towards singing didn’t exist and I began playing with the form, trying to grasp it—trying to make a song that transcended the information in it, the character and plot” (Chronicles 276)

I would argue that he accomplishes those goals in the song and video of “Sweetheart Like You.” He plays with the form in a way that transcends his raw material of character and plot, presenting a sly social critique through music and performance that follows in the footsteps of Brecht & Weill’s The Threepenny Opera and the mop trail of Lenya’s “Pirate Jenny.”

Lotte Lenya died in Manhattan in 1981, so in case you’re wondering (as I did): no, unfortunately the scrubbing lady in the video is not Pirate Jenny. Still, she looks more like Lenya than like Dylan. See for yourself. Here she is as the villain Rosa Klebb in the James Bond movie From Russia With Love, filmed the year after her fateful performance at the Theatre de Lys.

By the way, that’s a cute hat.

Afterlives

Dylan has never performed “Sweetheart Like You” in concert. And yet the song has had an interesting afterlife beyond the eighties and beyond Dylan thanks to talented women performers. For instance, Chrissie Hynde of The Pretenders includes a sensitive cover of the song on her 2021 album Standing in the Doorway: Chrissie Hynde Sings Bob Dylan.

It’s a small detail, but the thing I love best about Hynde’s rendition is her enunciation of the word “dump.” Dylan leans into the Bogie term of endearment “sweetheart,” but Hynde grinds her pumps into the Bette Davis term of contempt “dump,” as in “What a dump!” Davis first delivered the line in the film Beyond the Forest (1949). But the line was really made famous through parody, when Elizabeth Taylor delivered a wonderfully exaggerated imitation of Davis in the film adaptation of Edward Albee’s Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (1966).

By the eighties, “What a dump!” had become the elderly Davis’s catch phrase, though by then she said the line like an imitation of Taylor’s imitation. I don’t know if Dylan had this in mind when he wrote “Sweetheart Like You,” but Hynde surely has it in mind when singing the refrain. In conjuring these echoes, she adds yet another level of mimicry to a song that is already stacked with multilayered pastiche.

In her review of Hynde’s Standing in the Doorway (alongside Emma Swift’s Blonde on the Tracks) for The Dylan Review, Christine Hand Jones rightly notes, “The women who have covered the songs of Bob Dylan have left an indelible mark on his career and his compositions.” She cites several examples and adds Hynde and Swift to the distinguished lineage.

As with the best interpretations, these albums not only highlight the depth and beauty already inherent in Dylan’s work, they also add new layers of meaning that neither Dylan nor any male interpreters could hope to achieve. When Hynde and Swift cover Dylan, they also uncover a range of feminist interpretations that shine uniquely in the female voice.

Jones focuses in particular on Hynde’s “Sweetheart Like You.” She observes that Dylan’s version can come across at times as paternalistic or creepy. Not so with Hynde:

All of these lines hit differently when imagined as a woman speaking to another woman or a woman speaking to herself. They sound understanding, accepting, even helpful. As with other lines that sound condescending when coming from a man to a woman, “Snap out of it, baby,” takes on a different tone when self-directed, for who among us has not needed to give ourselves a wakeup call? What is this good girl doing in a place where she knows she should not be? It is a question many have asked themselves when their choices have led them to dark places. In this context, a potentially disturbing line like “Just how much abuse will you be able to take? / Well, there’s no way to tell by that first kiss,” takes on a wry, self-knowing tone.

Jones concludes that “With Hynde at the helm, ‘Sweetheart Like You’ explores new territory. Although the song slides away from clear, unified interpretation no matter who sings it, having a female narrator sing the song to herself suddenly makes us suspect that a woman, too, may embody multitudes: Sweetheart, Scoundrel, Queen, Messiah? She contains them all.”

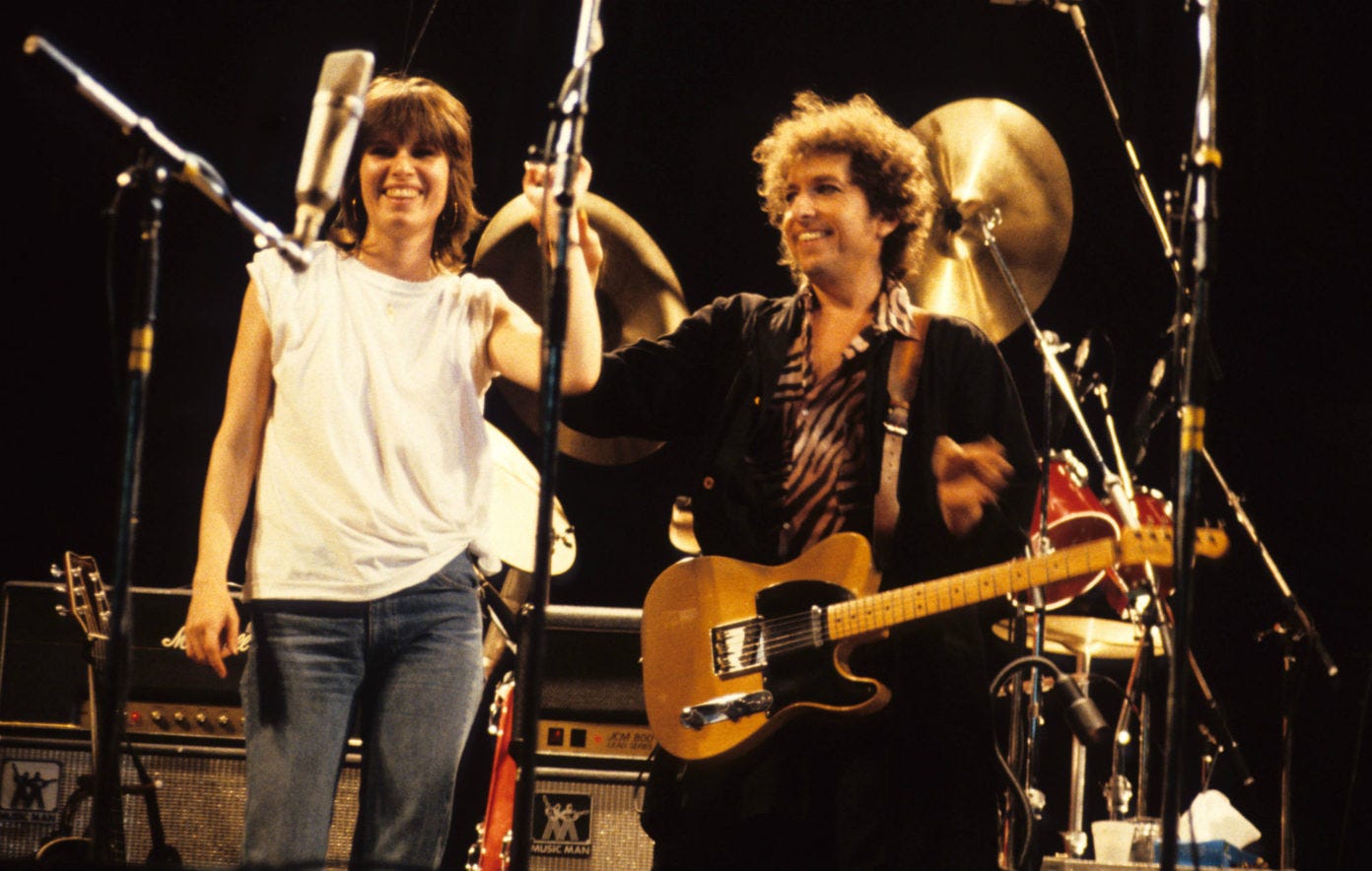

Hynde and Dylan go way back. She joined him on stage for multiple songs at the famous Wembley Stadium concert in London in 1984:

She also appeared at the 30th Anniversary Concert at Madison Square Garden in New York in 1992, where she played “I Shall Be Released.” In the present context, however, their most interesting connection is through Mark Robinson. The very first music video he ever directed was “Brass in Pocket” by The Pretenders.

Interestingly, this video also features a hardworking woman gazing into an enticing world just out of her reach. In this case, the worker is a waitress played by Hynde, who works for tips (i.e., brass in pocket) but aspires to quit her dead-end job and lead a more exciting life. The women in “Brass in Pocket” and “Sweetheart Like You” just can’t catch a break. Whether slinging hash or mopping floors, they are both dreamers stuck in dumps and surrounded by a bunch of pretenders.

Readers of Shadow Chasing are doubtlessly familiar with Chrissie Hynde, but you may not know Lo Carmen. To be honest, I had never encountered her work until I stumbled across it while researching this piece. You should check her out. On her Substack site Loose Connections, she describes herself this way:

I’ve been an independent operator as a producer of musical, written and other creative works since . . . forever. I am a singer-songwriter/recording artist/touring musician/writer and occasional actor sharing essays and recommendations on cultural delights and fascinations every weekend. I create and host the Death Is Not the End podcast. I’ve been published in Rolling Stone, The Guardian, Vogue, Talkhouse, No Depression and many other places.

She is also the author of Lovers Dreamers Fighters, a “femnoir/manifesto” published by HarperCollins Australia.

Her very first post on Loose Connections was an essay about her long-term love affair with, and creative inspiration from, Dylan’s “Sweetheart Like You.” She begins at the beginning: “At the end of 1983, when I was thirteen years old, Bob Dylan released the song ‘Sweetheart Like You’, and eventually it worked its way onto lounge room stereos and radio waves across Australia and soon worked its way deep into my consciousness. I became obsessed.”

Carmen’s response to the song was wrapped up in two identities: her working life after school in a series of low-paying, thankless jobs; and her future aspirations to become a professional musician.

Something about the “what’s a sweetheart like you doing in a dump like this?” scenario appealed to my tender burgeoning vanity. It was like Bob Dylan could see the real me, beneath the facade of the mythical “cute hat,” behind the ever churning wheels of grime, sweat and damp tea towel. He saw my shine, knew that given half a chance, I could make them tires squeal with my talents. As the years went on, the song was never too far from my stereo, or my heart.

Carmen never responded to the singer as a barroom gigolo on the prowl. From the start, she responded to the song as words of wisdom and warning from a mentor to a protégé.

I began to feel like he was talking to me artist to artist. I felt like he was sitting me down in an empty diner booth and straight talking to me, saying “I recognise what you’re trying to do here—but do you understand what you have to sacrifice for success?” It was like a “Danger Ahead!” sign from the dude watching it all go down from the sidelines at the Devil’s Crossroads. I felt like the song had become a kind of warning; of the value judgements, the demands, the dismissiveness, the hurt, the fakery, the gritted teeth, the itchy glamour, the inherently messed up world of “making it.” I took my own messed up comfort from that reading of it.

This response resonates well with the critical perspectives discussed above, but it’s especially interesting to hear coming from a woman approaching the song as a fellow artist.

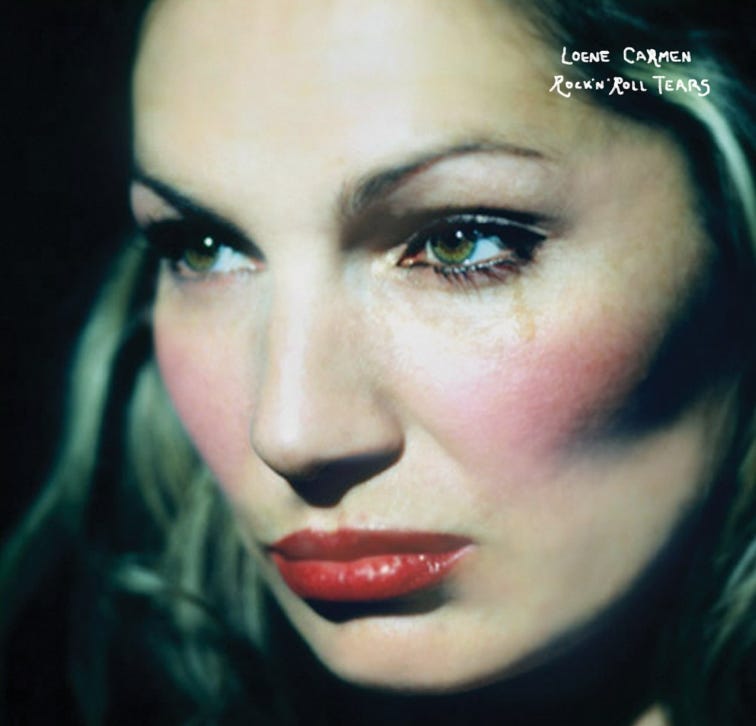

The story doesn’t end there. Twenty years later, Lo Carmen wrote an answer to “Sweetheart Like You” called “Rock’n’roll Tears.” It’s a cool song with breadcrumbs leading back to the original source. For example, I love the lines:

He said “What happened to you, you’re all rouged up

And you got soot on your knee”

I said “I been crawling across cut glass

Just trying to get somewhere clean”

Carmen seems to be illustrating that line with the album cover. If you’ve made it this far into the post, the affinities with the “Sweetheart” video should be obvious.

Carmen vividly elaborates on her intentions with this answer song:

I wanted to write a song where I was the girl in “Sweetheart Like You,” but who she was when she gets home from her shitty job, and transforms into the songwriting machine she really is down deep inside, where money doesn’t matter and all that matters is the words spread out around her, where she looks like wreck and she doesn’t care cos she’s fired up and excited cos she’s busily invested in working on stuff that’s important to her, not trying to put on a presentable or appealing front for the boss or the customers, not worn down by the relentless dumbing down of what the world requires of her for her survival.

Surviving in a ruthless world indeed. What a remarkable parallax view. It’s like Carmen steps through the looking-glass and writes the song from the other side of the mirror, standing in the custodian’s shoes from the video.

Rather than feeling demeaned as a woman by “Sweetheart Like You,” Carmen felt inspired as an artist to create new work: “Writing the song felt empowering. More than anything, I wanted to play it for Bob. I knew he’d understand the journey it took to get there. I took his anthem and turned it into my own anthem. Just like he’d done a million times before with his own ancestors in song.” She reimagines “Sweetheart Like You,” not as a series of pickup lines from some skeezy lounge lizard, but rather as a dialogue between fellow artists.

If you listen, it’s not hard to understand the secrets he’s telling you, like “steal a little and they throw you in jail, steal a lot and they make you king.” It’s all there for the taking. Take what you need and make up the rest. At the end of writing my answer song, I felt like I’d gone head to head, toe to toe, with the King, conversed in a corner with the court jester and walked out crowned a Queen.

Laura Tenschert, Rebecca Slaman, Rae Bourbon, Lotte Lenya, Chrissie Hynde, Christine Hind Jones, Lo Carmen, and the unidentified custodian from the video. I thank these strong women, creative performers, and critical thinkers for teaching me to see and hear things I previously overlooked or misunderstood in “Sweetheart Like You.” This post is dedicated to you all.

Works Cited

Carmen, Lo. “What’s a Sweetheart Like You Doing in a Dump Like This?: On Writing Your Own Anthems & Psychic Conversations Between Bob Dylan & a Rock’n’roll Waitress.” Loose Connections (14 April 2021),

.

Dylan, Bob. Chronicles, Volume One. Simon & Schuster, 2004.

---. Official Lyrics. The Official Bob Dylan Website,

https://www.bobdylan.com/.

Gans, Terry. Surviving in a Ruthless World: Bob Dylan’s Voyage to Infidels. Red Planet, 2020.

Gates, David. “Dylan Revisited.” Newsweek (5 October 1997), https://www.newsweek.com/dylan-revisited-174056.

George, Alice. “Carol Burnett Reveals How She Came to Create the Charwoman.” Smithsonian Magazine (28 November 2022), https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smithsonian-institution/carol-burnett-reveals-how-she-came-to-create-the-charwoman-180981168/.

Gray, Michael. Song & Dance Man III: The Art of Bob Dylan. Cassell, 2000.

Jones, Christine Hand. Album Reviews of Chrissie Hynde’s Standing in the Doorway: Chrissie Hynde Sings Bob Dylan (BMG, 2021) and Emma Swift’s Blonde on the Tracks (Tiny Ghost Records, 2020). The Dylan Review (Fall/Winter 2021-22), https://thedylanreview.org/2022/01/15/review-of-standing-in-the-doorway-and-blonde-on-the-tracks/.

Lepidus, Harold. Interview with Carla Olson. Boston Harold Podcast (15 September 2021), https://bostonharoldpodcast.blogspot.com/2021/09/carla-olson-behind-scenes-at-dylans.html.

Riddle, Randy A. “Ray Bourbon’s ‘Mop Lady’ and Carol Burnett’s ‘Charwoman.’” Don’t Call Me Madam: The Life and Work of Ray Bourbon (31 January 2020), https://raebourbon.com/2020/01/31/ray-bourbons-mop-lady-and-carol-burnetts-charwoman/.

“Sweetheart Like You.” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sweetheart_Like_You.

Tenschert, Laura. “Episode 9: Women and Dylan.” Definitely Dylan (11 March 2018), https://www.definitelydylan.com/listen/2018/3/11/episode-9-women-and-dylan.

---. “‘Oh Mama!’: Women & Dylan with Rebecca Slaman.” Definitely Dylan (6 August 2023), https://www.definitelydylan.com/podcasts/2023/8/6/oh-mama-women-amp-dylan-with-rebecca-slaman.

Tootsie. Written by Larry Gelbart, directed by Sydney Pollack, starring Dustin Hoffman. Columbia Pictures, 1982. https://www.writingclasses.com/WritingMovies/Tootsie.pdf.

Ah Graley, what a wonderful and entertaining piece, thank you – I actually laughed out loud at the juxtaposition of Tootsie and the picture from the Masked & Anonymous premiere, that’s hilarious!

I’m honoured that my episode and the conversation with Rebecca (which I loved so much) helped inspire you to write this. And I’m so glad that you keep returning to the topic of burlesque and explorations of gender and queerness, because I love the sensitivity and humour you bring to this subject. I think there’s a book in there…

This might be very close to a point that you already made here, but in the midst of all the drag performance, I can’t help but think of the moment when women entered into male-dominated workspaces as a drag performance. The “power dressing” of 80s suits with strong shoulder pads to seem more imposing and masculine. Like Lady Macbeth “unsexing” herself in order to shed herself of “feminine” emotions and softness and instead become ruthless and cruel, all in subservience to her ambition. What happened to the sweetheart?

Re Pirate Jenny – having been part of a production of Brecht’s Dreigroschenoper back in high school, I want to add that pirate jenny is not actually a character in the play. The song is sung by Polly Peachum at her wedding to Mack the Knife (although I just looked it up, and in some productions it appears later in the opera, sung by the prostitute Jenny, Mack’s lover). So she’s a character played by another character – and is pirate jenny masquerading or fantasising. It all adds another level of performance and performativity!

Speaking of the original video idea of two women who play the same role but are two different women – I guess Dylan finally realised that vision in the Tight Connection to My Heart video, which features two women who are sometimes dressed alike. In the end, the role that both women play is that of Dylan’s sweetheart of course.

This has given me a lot to think about, and I’m sure more thoughts will follow – thank you for always pushing the conversation forward, your writing is so unique.

I made it to the end and along the way accumulated quite a treasure trove of deep research that so characterizes your work, plus a bucket overflowing with ideas. Thanks for being the heavy hitter on any Dylan lineup.