Some of the best parts of Bob Dylan’s new book aren’t even in it.

Dylan sketches an outline for the art of the unsaid in an early chapter of The Philosophy of Modern Song: “A big part of songwriting, like all writing, is editing—distilling thought down to essentials. Novice writers often hide behind filigree. In many cases the artistry is in what is unsaid” (55). Dylan makes this observation in relation to “Pancho and Lefty,” but it applies equally well to his own approach in the book. His riffs and commentaries are usually quite brief, but he packs a lot into them, and he leaves a lot out.

One of his key techniques for “distilling thought down to essentials” is the integral use of images throughout the book. About a dozen photos come from the Michael Ochs Archive. Ochs first shared selections from his massive collection in the 1984 book, Rock Archives: A Photographic Journey Through the First Two Decades of Rock & Roll. The book is organized into three sections: Mitosis (late ’40s to late ’50s), Osmosis (late ’50s to early ’60s), and Cosmosis (mid ’60s to late ’60s). There are references to Dylan in all three sections, including a photo spread (206-7) where a central photo of Phil Ochs (the archivist’s older brother) is encircled by multiple shots featuring Dylan (three to the left, three to the right).

Several images from Michael Ochs are reproduced in Dylan’s book, and he may have borrowed more than just photos. The Philosophy of Modern Song mirrors Ochs’s curatorial agenda in Rock Archives. Ochs declares in his preface, “The greatest thing about popular music—and rock & roll in particular—is that it’s one of the most immediate forms of communication within the culture. A record, like a photograph, is an instant encapsulation of time and the means by which that time can be shared with others at a later date” (vii). Dylan shares this philosophy: records and photos work as time capsules. What gets packed into these time capsules is highly personal and idiosyncratic. As Ochs notes, “Only your own personal experience can allow you to feel respect for those whose work comes alive every single time you hear a song. With Rock Archives I’ve sought to present a vast, though incomplete and admittedly subjective, collection of photographs from many eras, the visual complement to countless sounds” (vii). Dylan takes a very similar approach in The Philosophy of Modern Song, providing verbal and visual complements to the songs he spotlights. His riffs and commentaries refract these songs through the prism of the person experiencing them. According to Dylan, “It’s what a song makes you feel about your own life that’s important” (9).

How does it feel? Sometimes the power of The Philosophy of Modern Song resides as much in what is omitted as what is included, what is concealed rather than revealed. Dylan saves one the best examples of the art of the unsaid for last. The final chapter, on “Where or When” by Dion and the Belmonts, includes his most thoughtful reflections on the interrelationships of time, memory, and identity as mediated through song. It’s an ideal marriage of song and interpretation, and of content and form. Dylan writes about “Where or When” in such a way that his riff and commentary function as enactments of the very process being described: musical reincarnation. But that’s only part of the story, because the rest remains hidden from view. “In many cases the artistry is in what is unsaid. As the old saying goes, an iceberg moves gracefully because most of it is beneath the surface” (55). So, too, with Dylan’s reincarnations in “Where or When.” He gives us a peek into his personal musical time capsule, but he keeps his most prized memento mori to himself.

Let’s start with the visible part of the iceberg. The riff begins:

This is a song of reincarnation, one repetitious drone through space, plugging the same old theme, nonstop over and over again, where every waking moment bears a striking resemblance to something that happened in pre-Revolutionary times, pre-Renaissance times or pre-Christian times, where everything is exactly alike, and you can’t tell anything apart. History keeps repeating itself, and every moment of life is the same moment, with more than one level of meaning. (327)

Dylan has spoken about reincarnation many times in different contexts, but he’s hard to pin down. He is better at singing about it than talking about it. His most articulate expressions of reincarnation come in the shifting identities and fateful recurrences on songs from Blood on the Tracks and Street-Legal. In interviews, however, he’s all over the place. Asked in 1977 by Jonathan Cott, “Do you believe in reincarnation?” he demurred: “I don’t think there’s enough time for reincarnation. It would take thousands or millions of years and light miles for any real kind of reincarnation. I think one can be conscious of different vibrations in the universe and these can be picked up. But reincarnation from the twelfth to the twentieth century—I say it’s impossible” (Cott 567). Asked the following year by Karen Hughes if he believed in reincarnation, he modestly reversed positions: “In a casual but not astonishing way” (Hughes 636). Martin Keller posed the question a third time to Dylan in 1983 and received a third different reply: “Yeah, I do. I don’t think there are any new souls on earth. Caesar, Alexandra, Nebuchadnezzar, Baal, Nimrod. They’ve all been here time and time again. Spirit talks to flesh—flesh talks to spirit. But you never know which is which” (Keller 755). In his 2012 interview with Mikal Gilmore, Dylan suggested that “transfiguration” was a better way to talk about these issues. There he suggested he was the transfiguration of Bobby Zimmerman, a Hells Angels biker who died in a crash in 1966. “I couldn’t go back and find Bobby in a million years. Neither could you or anybody else on the face of the Earth. He’s gone. If I could, I would go back. I’d like to go back. At this point in time, I would love to go back and find him, put out my hand. And tell him he’s got a friend. But I can’t. He’s gone. He doesn’t exist” (Gilmore). A decade later in The Philosophy of Modern Song, Dylan seems to have found a way of going back and touching that lost Bobby Zimmerman from the past by reanimating the songs of his youth.

It helps that the singer of “Where or When” is someone with whom Dylan can closely identify. Dion DiMucci was still a teenager when he recorded this song with the Belmonts in 1959. Like Bob Dylan, Dion has undergone a number of radical transformations over the course of his long and varied career. As Dylan writes in his commentary,

Dion DiMucci evolved throughout his career, changing outwardly but maintaining recognizable characteristics across every iteration. Not reincarnation in the strictest sense but an amazing series of rebirths, taking him from an earnest Teenager in Love to a swaggering Wanderer, a soul-searching friend of Abraham, Martin and John to a hard-edged leather-clad king of the urban jungle who was a template for fellow Italo-rocker Bruce Springsteen. Most recently, he has realized one of his early dreams and become some kind of elder legend, a bluesman from another Delta. (334)

Change a few words and this passage works as Dylan’s own concise bio. But caveat emptor. As Dylan counsels the reader early on, “Knowing a singer’s life story doesn’t particularly help your understanding of a song” (9). Dylan breaks this rule about as often as he observes it in The Philosophy of Modern Song. Ultimately, however, in the final chapter as throughout the book, his focus is more on the song than the singer. He cares less about Dion’s rebirths than about the strange magic of songs like “Where or When” to perform musical reincarnation.

Dion and the Belmonts perform “Where or When” on Dick Clark’s Saturday Night Beech-Nut Show (27 February 1960). YouTube video posted by NRRArchives.

Some things that happen for the first time

Seem to be happening again

And so it seems that we have met before

And laughed before and loved before

But who knows where or when?

Dylan opens his final commentary by replicating the song’s sense of déjà vu: “I feel like I’ve already written about this song before. But that’s understandable because ‘Where or When’ dances around the outskirts of our memory, drawing us in with images of the familiar being repeated and beguiling us with lives not yet lived” (331). In a way Dylan has written about this song before in the preceding chapters. The final chapter feels like the last song on a great Dylan album, a perfect culmination of the tracks that came before it. He brings it all back home in the final paragraph with a distillation of his philosophy of modern song: “But so it is with music, it is of time but also timeless; a thing with which to make memories and the memory itself. Though we seldom consider it, music is built in time as surely as a sculptor or welder works in physical space. Music transcends time by living within it, just as reincarnation allows us to transcend life by living it again and again” (334). That’s a damn good description of Dylan’s attempts to resuscitate songs from the past by reembodying them in his voice and in his book. Time in and out of mind. Time in and out of various bodies, too. By the end, after following Bob Dylan on his journey from Detroit to Nirvana, from Bobby Bare to Dion DiMucci (BB to DD), The Philosophy of Modern Song emerges, collectively and in its constituent parts, as a well sculpted, deliberately orchestrated, wizard-like display of musical reincarnation, transcending time and living lost lives again.

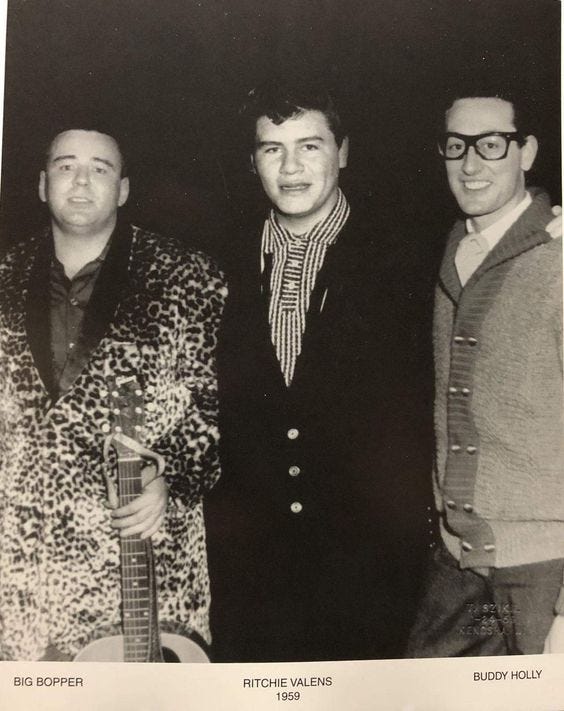

Dylan doesn’t put everything on display, however. The book is also an artwork of the unsaid. I suspect that the Wizard of PoMS has another reincarnation in mind but keeps it cloaked behind his curtain. Who knows where or when? The Shadow knows. Behind the book’s opening trinity of ’50s singers on the cover (Little Richard, Alis Lesley, and Eddie Cochran), and its closing trinity of ’50s singers (Dion and the Belmonts), lurks another trinity hidden in the shadows, never named or shown, but hovering over the book and making their presence felt most acutely in the final chapter. Buddy Holly, The Big Bopper, and Ritchie Valens.

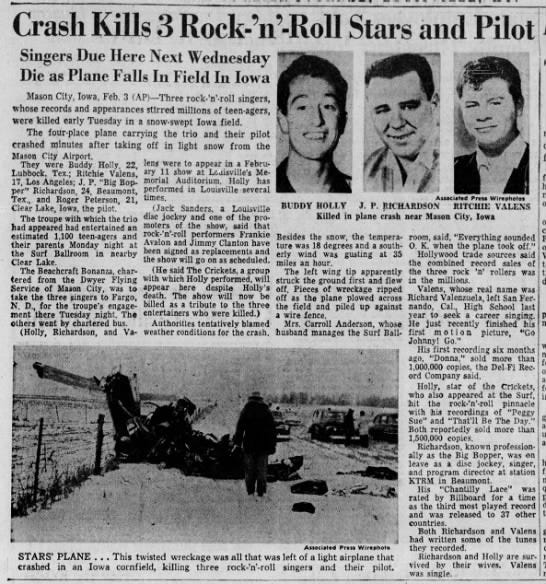

Invisibly and inexorably, Dylan’s compass in “Where or When” points toward two coordinates in space and time: Duluth National Guard Armory on 31 January 1959; and a cornfield in Clear Lake, Iowa, on 3 February 1959. The first where-and-when is the night teenager Bobby Zimmerman traveled from Hibbing back to the city of his birth to attend a concert in the Winter Dance Party tour headlined by Buddy Holly. The second where-and-when is the deadly plane crash, when a rented Beechcraft Bonanza (another BB) went down in wintry conditions, killing the pilot and three young rock stars from the tour. Ever since Don McLean released his anthem “American Pie” in 1971, this morbid event has been popularly referred to as “The Day the Music Died.” But from Dylan’s perspective in The Philosophy of Modern Song, McLean gets it wrong. Holly, Richardson, and Valens died that day, but their music did not. The songs live on, not fade away.

As Dylan memorably recounts in his Nobel Lecture, during the Duluth concert he sensed an energy transfer directed specifically at him, projected from the stage to the audience, from 22-year-old Buddy to 18-year-old Bobby.

He was powerful and electrifying and had a commanding presence. I was only six feet away. He was mesmerizing. I watched his face, his hands, the way he tapped his foot, his big black glasses, the eyes behind the glasses, the way he held his guitar, the way he stood, his neat suit. Everything about him. He looked older than twenty-two. Something about him seemed permanent, and he filled me with conviction. Then, out of the blue, the most uncanny thing happened. He looked me right straight dead in the eye, and he transmitted something. Something I didn’t know what. And it gave me the chills. (Nobel Lecture)

Dylan depicts this mystical moment as his transfiguration, when something permanent—the transcendent and immortal spirit of music—was passed to him just days before the plane plummeted into the valley of the shadow of death and Holly could no longer carry the musical torch forward in person. For Dylan, 31 January 1959 was The Night the Music Lived, and it has continued to live through him ever since as the keeper of its eternal flame. He carries it with him every time he takes the stage, and will continue to do so until his mortal candle is snuffed out and his turn comes to pass the torch. All singers eventually die, but Dylan takes it as an article of faith (The Theology of Modern Song?) that the music transcends time and lives again and again.

At this point I imagine some of my readers are thinking, “Amen! Well said. But you are the one saying it, not Bob Dylan.” Fair enough. Dylan says, “In many cases the artistry is in what is unsaid” (55), and I agree. However, I also acknowledge that the art of the unsaid cannot be a blank check with an infinite credit line. Dylan didn’t say Macbeth or “The Gettysburg Address” either, and it would be a distorted fantasy to imagine that he deserves credit for everything under the sun that he never uttered or wrote. As I understand it, the art of the unsaid requires a palpable gesture toward the thing that is intentionally left out, like drawing a chalk outline around the lacuna of a missing person. It also results in a kind of hide-and-seek game with the reader, a riddle waiting to be solved.

I’m reminded of a passage from Jorge Luis Borges’s mind-bending story “The Garden of Forking Paths,” published the year of Dylan’s birth. The title refers to a secret labyrinth in time constructed by Ts’ui Pen. Sinologist Stephen Albert asks the narrator, “In a riddle whose answer is chess, what is the only word that must not be used?” He thinks for a moment and correctly answers, “The word ‘chess.’”

“Exactly,” said Albert. “The Garden of Forking Paths is a huge riddle, or parable, whose subject is time; that secret purpose forbids Ts’ui Pen the merest mention of its name. To always omit one word, to employ awkward metaphors and obvious circumlocutions, is perhaps the most emphatic way of calling attention to that word.” (Borges 126)

Over the course of 340 pages, Dylan drops hundreds of names in The Philosophy of Modern Song. But unless I missed it, he never mentions Buddy Holly a single time. He never mentions The Big Bopper. He never mentions Ritchie Valens. Did these prominent 1950s rockers, whom Dylan personally saw perform live in concert, simply slip his mind while assembling a book that returns over and over to the songs of his youth? Maybe. I find it much more likely, however, that these conspicuous omissions serve as gaps to be filled by the reader, absences that exert a powerful presence. Call it the art of the unsaid or call it a riddle. Dylan uses his chapter on “Where or When” to point us in the direction of these missing persons. He drafts Dion into service as his messenger and proxy.

Who knows where or when? Dion knows.

Dion DiMucci was present for the first where-and-when in 1959 Duluth, and fortunately he was absent for the second where-and-when in 1959 Clear Lake. That year Dion and the Belmonts (D and the B’s) were looking for road experience and greater exposure, trying to expand their audience beyond the East Coast, and hopefully build some buzz for their upcoming debut album. Opening for a well-established artist like Buddy Holly on the Winter Dance Party tour was a major coup for the 19-year-old DiMucci and his mates from Belmont Avenue in the Bronx. Their first hit single, “A Teenager in Love,” was released the month after the plane crash, and their first album, Presenting Dion and the Belmonts, was released in October 1959. It contained the song “Where or When,” which would prove the biggest hit the group ever had.

None of it would have happened if Dion had taken his seat on that plane. In an extensive interview with Forbes magazine in 2019, he details that fateful night of 3 February 1959. After repeated mechanical problems with the tour bus, Holly impulsively rented a small four-seat plane to fly to Fargo, North Dakota, for the next show in neighboring Moorhead, Minnesota. According to Dion, he flipped a coin for a seat on the plane and won; but when he heard he would have to pay $36 for the perk (the same price as his father’s rent in the Bronx), he balked and gave his seat to Ritchie Valens. He was haunted for years by the fluke that saved his life. But he also feels blessed by the enduring spirits of his fallen friends. He told interviewer Jim Cash,

Those three guys affected my life on a lot of levels. Buddy told me once, “Dion, I don’t know how to succeed, but I know how to fail. Try to please everybody, and you’ll go nowhere.” If he didn’t tell me that, I probably never would have done “Runaround Sue,” “The Wanderer,” “Abraham, Martin and John.” I miss those guys. Thank God that in my faith, relationships never end. I always ask for their prayers, because I feel they are closer to the beatific vision, and are helping me out. I have three angels up there. (Cash)

Dylan probably shares Dion’s religious faith, and he certainly shares his faith in the transcendent, immortal, saving power of music. For more than sixty years, they have both been keeping the faith by playing these songs, communing with the spirits, conjuring acts of musical reincarnation, projecting that energy to audiences, and inspiring new generations of fans.

Dylan has frequently acknowledged his debts to Buddy Holly in public comments and performances. During his Grammy acceptance speech for Album of the Year for Time Out of Mind, he recalled the night he saw Buddy Holly play in Duluth, and he credited Holly’s spirit with presiding over the recording sessions. Around the same time, he elaborated upon Holly’s spectral presence in an interview with Murray Engleheart:

While we were recording, every place I turned there was Buddy Holly. You know what I mean? It was one of those things. Every place you turned. You walked down a hallway and you heard Buddy Holly records, like “That’ll Be the Day.” Then you’d get in the car and go over to the studio and “Rave On” would be playing. Then you’d walk into this studio and someone’s playing a cassette of “It’s So Easy.” And this would happen day after day after day. Phrases of Buddy Holly songs would just come out of nowhere. It was spooky [laughs]. But after we recorded and left, you know, it stayed in our minds. Well, Buddy Holly’s spirit must have been someplace, hastening this record. (Engleheart 1234-35)

Dylan’s chief form of commemorating Holly’s influence and keeping his spirit alive is through song. Dylan often takes a break from touring in the months of January and February, so he was off the road on the tenth, twentieth, and thirtieth anniversaries of the 1959 concert and crash. But when he played in New Orleans on 3 February 1999, he closed with Holly’s timeless hit “Not Fade Away,” paying his respects and honoring Holly’s musical immortality on the 40th anniversary of his death. “A love that lasts more than one day / Love is love and not fade away.” The song became a mainstay of the Never Ending Tour that year with 84 performances in 1999. Had Dylan’s love for this song faded in the intervening four decades? Judge for yourself:

Dylan is joined by Steve Van Zandt and Nils Lofgren of the E Street Band for a performance of “Not Fade Away,” at Hallenstadion in Zürich, Switzerland, on 25 April 1999. YouTube video posted by KULP11.

For the fiftieth anniversary, Dylan was off the road again in January and February. But that summer he made a point of playing Buddy Holly’s hometown of Lubbock, Texas, on 8 August 2009, where he opened the encore with “Not Fade Away.” To date this remains Dylan’s last public performance of the song. He was not done commemorating those formative experiences from 1959. He ended the 2009 tour with a three-night stand in New York City. In what must have felt like déjà vu of the most surreal and wonderful kind, his opening act was Dion—the same artist who opened for Holly on the Winter Dance Party tour fifty years earlier, when young Bobby Zimmerman was on the other side of the footlights.

The concert venue was the United Palace Theatre, which today functions (seriously, you can’t make this stuff up) as home of the United Palace of Spiritual Arts. “It seems we stood and talked like this before / We looked at each other in the same way then / But I can’t remember where or when.” Who knows where or when? Dylan knows. Dion provides the link back to Holly. Dylan leaves it artfully unsaid, but he guides us there. Then he trusts us to follow the jingle-jangle where it leads and complete the final steps of the journey ourselves. It is a journey back home.

Holly is the jingle to Dylan’s jangle. The Hibbing teen was already playing music before attending the Winter Dance Party concert. But looking back on the long odyssey of his musical career, he locates his true musical genesis at Duluth National Guard Armory on 31 January 1959. In his Nobel Lecture, he explicitly gives credit only hinted at in The Philosophy of Modern Song.

If I was to go back to the dawning of it all, I guess I’d have to start with Buddy Holly. Buddy died when I was about eighteen and he was twenty-two. From the moment I first heard him, I felt akin. I felt related, like he was an older brother. I even thought I resembled him. Buddy played the music that I loved—the music I grew up on: country-western, rock ’n’ roll, and rhythm and blues. Three separate strands of music that he intertwined and infused into one genre. One brand. And Buddy wrote songs—songs that had beautiful melodies and imaginative verses. And he sang great—sang in more than a few voices. He was the archetype. Everything I wasn’t and wanted to be. I saw him only but once, and that was a few days before he was gone. I had to travel a hundred miles to get to see him play, and I wasn’t disappointed. (Nobel Lecture, emphasis added)

With his mixture of styles and voices, galvanized by the raging glory of his talent, Buddy Holly was the archetype for Bobby Zimmerman to follow in refashioning himself into Bob Dylan.

If Holly was the archetype, then the Nobel Lecture is a rough draft of the blueprint Dylan would later follow in The Philosophy of Modern Song for reconstructing his musical odyssey. “When I received the Nobel Prize for Literature, I got to wondering exactly how my songs related to literature. I wanted to reflect on it and see where the connection was. I’m going to try to articulate that to you. And most likely it will go in a roundabout way, but I hope what I say will be worthwhile and purposeful” (Nobel). Dylan’s roundabout consideration leads him to reject categorizing his art as “literature,” which he associates with death. He identifies his art instead with song: “Our songs are alive in the land of the living.” According to Dylan, if you want to appreciate his art accurately, you shouldn’t place it alongside dead literary greats but alongside the pantheon of popular musicians. Dylan’s The Philosophy of Modern Song stakes its claim in the land of the living. At the end of the book, he declares: “Music transcends time by living within it, just as reincarnation allows us to transcend life by living it again and again” (334). Dylan’s journey comes full circle. The end of the book leads back home, back to the beginning to start all over again, where music never dies and love never fades away.

Works Cited

Borges, Jorge Luis. “The Garden of Forking Paths” (1941). Collected Fictions, edited and translated by Andrew Hurley. Penguin, 1998, pp. 119-28.

Cash, Jim. “Rock Icon Dion Recalls 1959 Plane Crash that Killed Buddy Holly” (14 February 2019). Forbes, https://www.forbes.com/sites/jimclash/2019/02/14/rock-icon-dion-recalls-1959-plane-crash-that-killed-buddy-holly-ritchie-valens-and-the-big-bopper/?sh=419fb1e32f33.

Cott, Jonathan. Rolling Stone interview with Bob Dylan (December 1977). Every Mind Polluting Word: Assorted Bob Dylan Utterances, edited by Artur Jarosinski, Don’t Ya Tell Henry, 2006, pp. 556-69.

Dylan, Bob. Acceptance Speech for Grammy Award for Album of the Year (25 February 1998). The Grammys. https://www.grammy.com/grammys/news/40th-grammys-who-won-big-four-categories.

---. “Nobel Lecture in Literature.” The Nobel Prize (4 June 2017). https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/literature/2016/dylan/lecture/.

---. The Philosophy of Modern Song. Simon & Schuster, 2022.

Engleheart, Murray. Guitar World Interview with Bob Dylan (March 1999). Every Mind Polluting Word: Assorted Bob Dylan Utterances, edited by Artur Jarosinski, Don’t Ya Tell Henry, 2006, pp. 1233-36.

Gilmore, Mikal. “Bob Dylan Unleashed.” Rolling Stone (27 September 2012). https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-news/bob-dylan-unleashed-189723/.

Hughes, Karen. Rock Express Interview with Bob Dylan (April 1978). Every Mind Polluting Word: Assorted Bob Dylan Utterances, edited by Artur Jarosinski, Don’t Ya Tell Henry, 2006, pp. 630-38.

Keller, Martin. Minneapolis City Pages Interview with Bob Dylan (July 1983). Every Mind Polluting Word: Assorted Bob Dylan Utterances, edited by Artur Jarosinski, Don’t Ya Tell Henry, 2006, pp. 753-56.

“Not Fade Away.” Composed by Charles Hardin (aka Buddy Holly) and Norman Petty. Performed by Buddy Holly and the Crickets.

Ochs, Michael. Rock Archives: A Photographic Journey Through the First Two Decades of Rock & Roll. Dolphin, 1984.

“Where or When.” Composed by Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart. Performed by Dion and the Belmonts.

Brilliant ruminations, Graley, on the paradoxes of time, memory, and history that coalesce, for Dylan, in popular song. I especially was intrigued by Michael Ochs' book, and it got me thinking of how the desire for some tangible connection to the past most old, single photos can evoke is at play too in our drive to re-play songs, over and over. Sculpting with time -- something Dylan seems to have been aware of, or at least intuited, when he began composing off old melodies. That wasn't "just the way it's done," I think, for Dylan, but it was a kind of haunting and inhabitation, not to be taken lightly.

Brilliant, again. Yes, you are telling us, not Bob, but someone needs to do the heavy lifting. Most readers of PoMS are not going to make these connections without you. And it’s clearly intentional. For those of us wanting to know the deeper levels of Dylan’s art, your essay is invaluable. Many folks are probably content with the tip of the iceberg, but I think it’s incredibly cool that Dylan has included some extra, more cosmic content for fans willing to dive under.

My own interest, as I once wrote you in an email, is the deeper layers of that mystical land called “Key West.” I’m bringing out a book soon with my discoveries, but here I’d like to point out a connection to Buddy Holly in that lovely song, and so to your themes here.

Yes, he mentions “Buddy” directly of course (and all the rest), but I’m thinking more of “Mystery Street,” where, supposedly, “Truman had his White House there.” Well, no. Truman had his White House on Front Street. Where Harry does live, for sure, is on the “Mystery Street” in Bob’s head, as described in Chronicles. There, Dylan describes sitting, as a child, on the shoulders of his uncle, and being “mesmerized” by the politician, as he gave a speech in Duluth’s Leif Eriksen Park, on the Superior lakeshore. This is one of the places Dylan takes us with the “Mystery Street” and “Truman” references in “Key West.”

But why? To bring us also to Holly. For one, “mesmerizing” is the same word, as you cite above, that the singer used to describe Holly in his Nobel speech. Spellbound. Mysterious. And next, Leif Eriksen is just across the way from the Duluth Armory, where Truman had appeared earlier that day, in 1948, and where Bob would have his fateful encounter with Holly 11 years later.

The “Mystery Street” of “Key West” is another of Bob’s below-the-surface references, tripping the “observant” listener back and forth in time. Another tribute to Buddy, and the power of song to change lives.

But, as we know, the dude contains multitudes. “Mystery Street” doesn’t only refer to Holly and that mystical transference of musical destiny. It also takes us directly to the song’s “convent home” and a message that the singer has left for us there, via his abiding interest in the personalities and moral quandaries of Civil War era America. More on that later . . .

Thank you for your insights, Grady! Incredible stuff!

And here’s Harry, and the Duchess of Duluth:

https://collection.mndigital.org/catalog/nemhc:5825#?cv=&c=&m=&s=&xywh=484%2C-6339%2C6273%2C16860