Still floating from the Dylan concert last night—“South of Cincinnati”?! What a gift!—I am eager to share the second installment of my three-part series on the underworld songs of Bob Dylan and Anaïs Mitchell. Here we’ll shift our focus to the musical Hadestown. As I mentioned in the first installment, Hadestown began as a small community theater project, grew into a concept album, and eventually went through multiple musical and dramaturgical evolutions in New York, Edmonton, and London before premiering on Broadway in 2019 at the Walter Kerr Theatre. It has become the longest running show in that venue’s history, a streak that is still going strong as I write this piece in late 2023.

In her book Working on a Song: The Lyrics of Hadestown (the source for all my quotations from the musical), Mitchell recalls the watershed moment that started it all:

It was the chorus of “Wait for Me” that set me on the road to Hadestown. I was early in my career as a singer-songwriter and driving a lot; back then I’d drive a ridiculous distance, alone, for a tip gig, and that’s what I was doing when that melody came, along with these words: “Wait for me, I’m coming / In my garters and pearls / With that melody did you barter me / From the wicked underworld?” (129)

The roots of that chorus were both personal and mythical, as Mitchell explains:

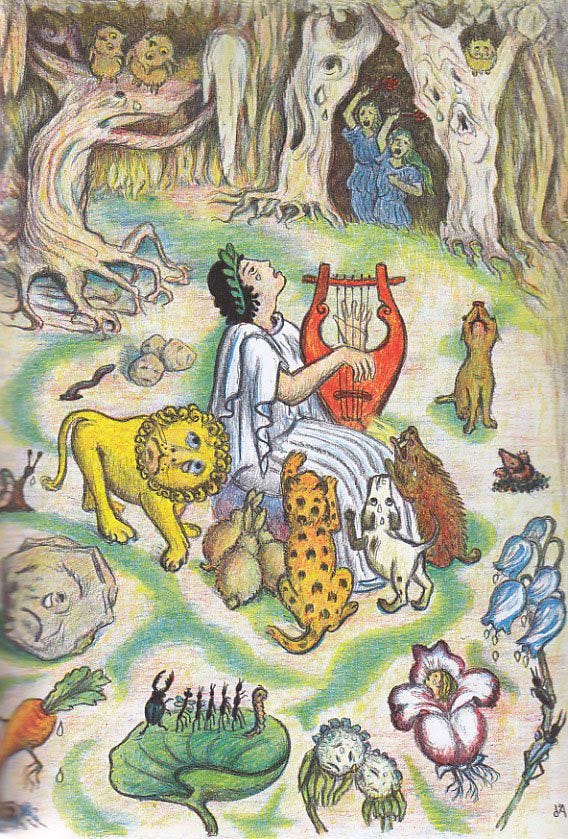

The first two lines had to do with my own love life. I met Noah [Hahn] when I was just nineteen and had the sense early on that I was going to marry him. I was young, though, and ambitious to become a touring singer-songwriter, so I was asking him to “wait” while I did some literal and figurative “running around.” The next two lines were mysterious, a free association, but they seemed to point to the story of Orpheus and Eurydice, which had been a favorite myth of mine as a kid. (130)

Mitchell and Dylan are kindred spirits in this regard. In the previous installment, I credited Dylan with a special gift for combining the personal with the mythical, best displayed in the underworld songs of Blonde on Blonde. There Dylan showcased his talent for taking first-hand experiences and relationships, expressing them in his own distinct voice, and yet simultaneously refracting them through ancient myths and primal archetypes. Mitchell inherited that same gift and cultivates it to magnificent effect in the “folk opera” Hadestown.

Dylan and Mitchell’s shared inheritance is part of their folk music birthright. In Chronicles, Dylan describes this music as the driving force of his young life, a force that catapulted him out of his mundane upbringing and into the realm of myth:

Folk music was a reality of a more brilliant dimension. It exceeded all human understanding, and if it called out to you, you could disappear and be sucked into it. I felt right at home in this mythical realm made up not with individuals so much as archetypes, vividly drawn archetypes of humanity, metaphysical in shape, each rugged soul filled with natural knowing and inner wisdom. Each demanding a degree of respect. I could believe in the full spectrum of it and sing about it. It was so real, so more true to life than life itself. It was life magnified. Folk music was all I needed to exist. (236, emphasis added)

For Mitchell, the formative intermingling of folk music and ancient mythology began at an even younger age. Mel Allen traveled to her hometown in Vermont and interviewed her family for a profile piece on New England.com. He reports, “Once, her parents had lived on the Greek island of Hydra, and they read the ancient myths aloud to Anaïs and her brother, Ethan. The stories became as familiar to her as the songs of Bob Dylan and Leonard Cohen and Joni Mitchell that were always playing in their house.” Her parents, Don and Cheryl Mitchell, knew Leonard Cohen personally on Hydra.

After returning to the U.S., the Mitchells became part of the “back to the land” ecological movement, starting a lamb farm in rural Vermont. Don Mitchell was also a professional writer, and he taught creative writing at nearby Middlebury College (his daughter’s future alma mater). When Allen spoke to him, he gave the journalist a copy of his book, Growing UpCountry: Raising a Family & Flock in a Rural Place. Don Mitchell describes their Vermont farm as a mythical realm: “He tells about how Anaïs and Ethan created their own kingdom in the deep meadows and woods beyond his sight. They drew a map to secret places they named Great Swamp, Sacred Spring, Bald Rock, Bowl of Stone, and Fairy Cliff. Don writes, ‘I feel the constant presence of a shadow world layered over what I consider to be my real one, steeping the entire farm in something like mythology’” (emphasis added). This shadow kingdom steeped in myth would prove the ideal breeding ground for the future creator of Hadestown.

As for musical influences, Mitchell names the big three over and over in interviews. For instance, she told Matthijs van der Ven: “Dylan was one of the bigger artists for me growing up in Vermont, together with Leonard Cohen, Joni Mitchell. […] Dylan of course is the Bible of that. Kind of undeniable.” All three leave their imprint on Hadestown, but the longest shadow is cast by Dylan. In honor of his 78th birthday, Mitchell performed a cover of “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall” for the website Influences. She reflected on the song and on Dylan’s enduring appeal:

I grew up with Bob Dylan, my parents had those records in their collection. I think that song [‘A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall’] is kinda like when the portal opened. It feels channeled. I don’t know if it was the first Dylan song I heard, but I do know I always responded to his early records. This like really folky, almost solo stuff. It feels so inspired. Obviously there’s a lot of words, you just are so transfixed by hearing image after image. I think it’s a song that feels more and more relevant and real nowadays, even though he wrote it so long ago.

To hear her tell it, Dylan sounds almost like a mythological figure, on a par with characters from the D’Aulaires’ Book of Greek Myths that she read as a kid.

It should come as no surprise, then, that when Mitchell began composing a “folk opera” about Orpheus’s descent into the underworld, she turned not only to the ancient myths that fascinated her since childhood, but also to the quasi-mythical modern Orpheus who sang much of the soundtrack of her youth. It’s the folk process since time immemorial: channeling the stories and songs that came before, making them your own, bringing them back to life for listeners, then handing them down for future musicians to recycle and reinvent. For the rest of this installment, let’s focus on echoes and reverberations—some quiet and subtle, others loud and substantial—between Mitchell’s Hadestown and Dylan’s work.

Hadestown

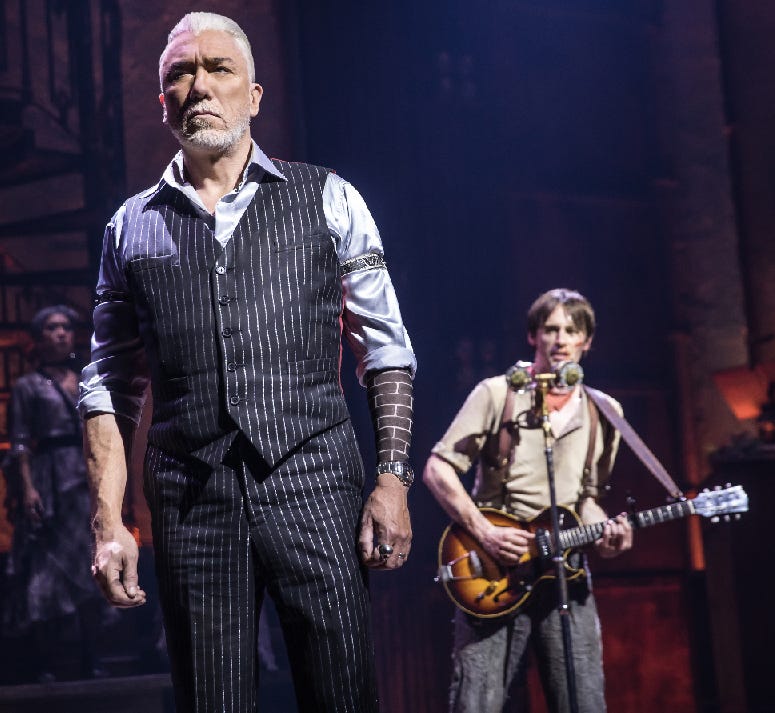

Mitchell put together an amazing ensemble for the 2010 album version of Hadestown, and she and director Rachel Chavkin put together the perfect company for the Broadway musical in 2019. The concept album features Justin Vernon (aka Bon Iver) as Orpheus, Mitchell herself as Eurydice, Ben Knox Miller as Hermes, Greg Brown as Hades, and Ani DiFranco as Persephone. The stage musical and subsequent cast recording stars Reeve Carney as Orpheus, Eva Noblezada as Eurydice, André De Shields as Hermes, Patrick Page as Hades, and Amber Gray as Persephone.

Even if you haven’t had a chance yet to see Hadestown performed live, it’s worth listening to the recordings and comparing them because they’re quite different. I’m especially struck by the differences in Justin Vernon’s interpretation of Orpheus compared with Reeve Carney. For most of the narrative arc, Vernon plays Orpheus as cock of the walk, fanning his tail feathers and strutting his stuff. He’s the best singer in this world and the next, and he knows it. Carney shows flashes of bravado, but he can come across at other times as credulous, vulnerable, distracted, and obsessive.

In Working on a Song, Mitchell retraces the evolution of what the creative team called “New Orpheus.” As Hadestown transitioned from album to musical, early audiences weren’t sure what to make of Orpheus:

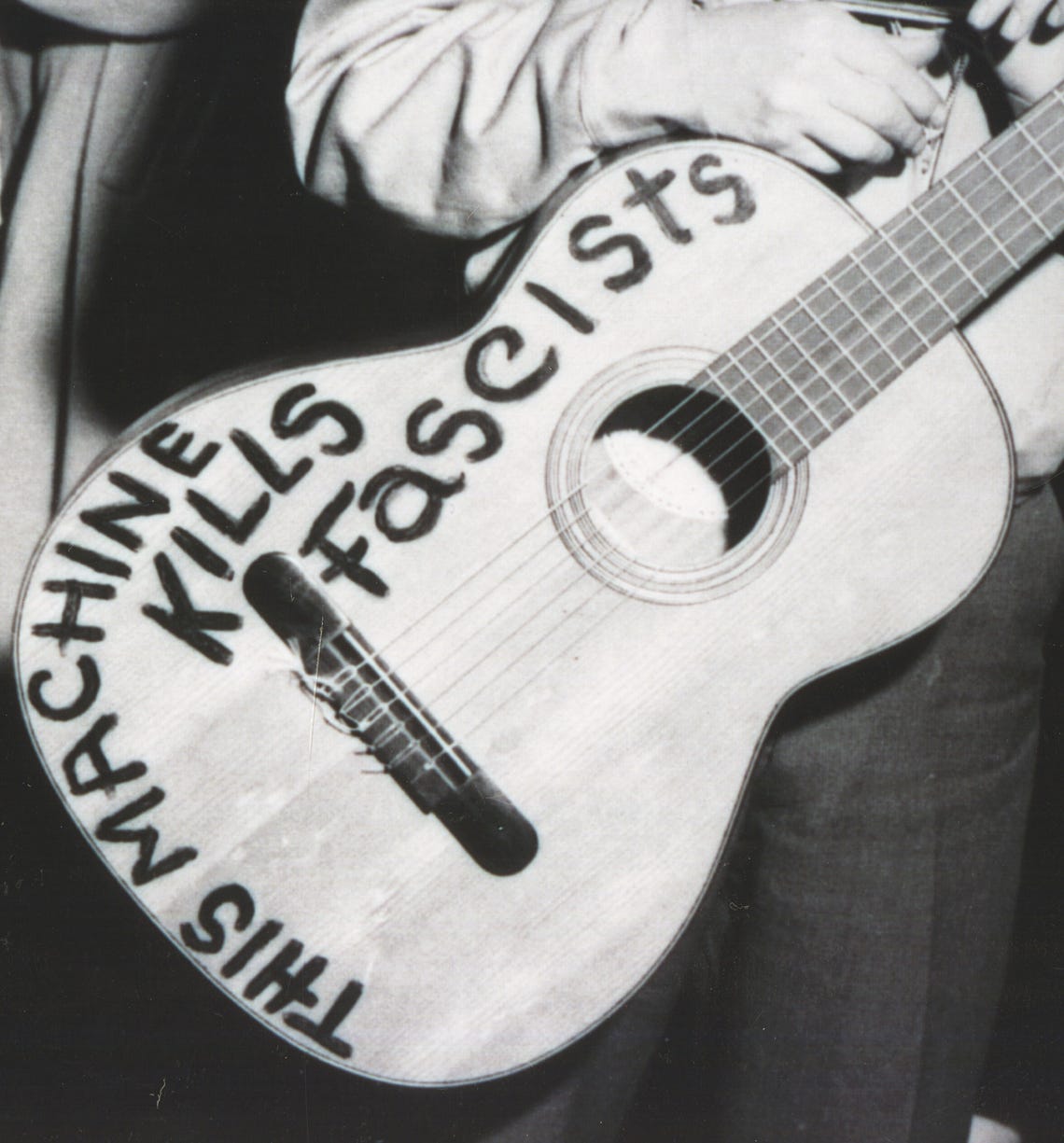

Was he Che Guevara, or Woody Guthrie? A revolutionary, or a farm boy? Was he really as confident as he came across in early versions of the show? What had been a pesky ambiguity became a full-blown crisis after London, when review after review commented on the unsympathetic qualities of our hero. Audiences weren’t falling in love with him, and we needed them to, for the story to matter at all. (19)

Part farm boy, part revolutionary, a protagonist that characters and audiences can both follow and fall in love with. The solution was to make Orpheus more Dylanesque. New Orpheus retains the anti-fascist idealism and rugged straightforwardness associated with Woody, but adds in the revolutionary allure and sexy danger that have become Che’s pop culture aura/brand. Want a singer-hero who kicks ass and melts hearts? No need to invent him from scratch because the perfect prototype already exists.

In order for the character to emerge as a rebel-hero, he needs a worthy nemesis. In Mitchell’s hands, the antagonist Hades is transformed into part fascist tyrant, part Pharaoh, part Harlan County coal boss, and part devil at the crossroads. Even the name Mitchell assigns her version of hell, Hadestown, sounds like a company town monopolized by a greedy tycoon.

Boss Hades is a descendant of the ravenous capitalists targeted in pro-union folk songs like “Which Side Are You On?” and “Ludlow Massacre,” as well as Dylan’s contribution to this tradition in the mining song “North Country Blues.”

The music of Hadestown riffs on Dixieland jazz, transforming the Walter Kerr stage into Preservation Hall and Napoleon House in New Orleans. The southern flavor of the music is reinforced with lyrical allusions to slave plantations, the New Orleans auction block, Jim Crow share-cropping farms, and the hell-on-earth prison labor camp Parchman Farm. Hermes and company put it this way in “Way Down Hadestown”:

Company: Way down Hadestown

Way down under the ground

Hermes: Mister Hades is a mean old boss

Persephone: With a silver whistle and a golden scale

Company: An eye for an eye!

Hermes: And he weighs the cost

Company: A lie for a lie!

Hermes: And your soul for sale!

Company: Sold!

Persephone: To the king on the chromium throne (80-81)

The damned in Hadestown are forced to work his mines, dig his silver and gold, build his walls, and line his pockets. When Eurydice descends in search of a steady meal, she signs Hades’s papers, surrenders her memories and free will, and essentially sells her soul to the devil.

With his lyre and his lyrics, Orpheus poses an existential threat to Hades:

The king of the underworld recognizes the danger. If his subjects follow Orpheus’s lead and free their minds, then he’ll soon have an uncontrollable rebellion on his hands. Hades spells out the peril in “His Kiss, The Riot”:

Dangerous, this jack of hearts

With his kiss, the riot starts

All my children came here poor

Clamoring for bed and board

Now what do they clamor for?

Freedom! Freedom (223)

If the workers keep listening to Orpheus, then they ain’t gonna work on Hades’s farm no more.

Dylan earned the title “voice of his generation” with his songs of freedom: questioning apathy that perpetuates war and racism in “Blowin’ in the Wind”; sounding the rally cry for progressive reform in “The Times They Are A-Changin’”; denouncing the military industrial complex’s greed in “Masters of War”; exposing systemic racism in the American legal system in “The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll”—you know this already, dear readers, and Mitchell does, too. If Dylan was “the Bible” of the music she grew up with, then the gospel he preached was freedom.

One of Dylan’s most inspirational declarations of solidarity with poor, huddled masses yearning to be free is “Chimes of Freedom.” Mitchell sang a moving cover of this song at the 2005 Festival on the Green on her home turf of Middlebury:

This is the spirit she instills in Orpheus, a courageous singer who inspires others through his freedom songs. Indeed, as the workers listen to Orpheus’s songs in the underworld, they begin to rise up, no longer keeping their heads low in a deferential stoop. They answer the call of his liberty bell, like the one Dylan sounds in “Chimes of Freedom”:

Tolling for the aching ones whose wounds cannot be nursed

For the countless confused, accused, misused, strung-out ones an’ worse

An’ for every hung-up person in the whole wide universe

An’ we gazed upon the chimes of freedom flashing

Mitchell is also familiar enough with Dylan’s work to know that eventually he felt suffocated by the expectations placed upon him as “voice of his generation.” When he turned in his resignation from Maggie’s Farm, he quit the movement that had at once anointed him as its leader while simultaneously coopting him as its indentured servant:

Well, I try my best

To be just like I am

But everybody wants you

To be just like them

They say sing while you slave

I just get bored

I ain’t gonna work on Maggie’s farm no more

That’s the declaration of independence he issued when he went electric at the Newport Folk Festival in 1965. But he already anticipated his emancipation a year earlier on Another Side of Bob Dylan.

Two songs after “Chimes of Freedom,” he sings a much more delicate song, “To Ramona,” in which he prioritizes individual freedom over the peer pressure of conformity, even when that pressure comes from well-intentioned groups like The Freedom Singers:

From fixtures and forces and friends

Your sorrow does stem

That hype you and type you

Making you feel

That you must be exactly like them

His alternative advice? “Everything passes / Everything changes / Just do what you think you should do.”

FYI: Anaïs Mitchell named her daughter Ramona.

Dylan’s ability to go big and to go small, to shift fluently from ambitious panoramic murals like “Chimes of Freedom” to intimate miniatures like “To Ramona,” to thump his chest defiantly in one breath and then expose his fragile heart of glass in the next—these are qualities Mitchell integrated into her New Orpheus. As she writes in Working on a Song, “We decided to reframe Orpheus as more of an innocent. […] This ‘New Orpheus’ wasn’t a shy character—that was important to me for the guy who sings ‘Wedding Song’—but a sensitive soul, the kind who gets lost in his own world sometimes” (19). This point is established in the prologue to Hadestown, “Road to Hell,” where each member of the cast is introduced. “Hermes has to introduce [Orpheus] twice, because he doesn’t hear the audience’s applause the first time. That little gesture alone seemed to endear him to the audience more quickly” (20).

Mitchell’s Orpheus reminds me of Springsteen’s Dylan. When he inducted Dylan into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, Springsteen described Dylan’s voice as “simultaneously young and adult.” “When I was a kid, Bob’s voice somehow—it thrilled and scared me. It made me feel kind of irresponsibly innocent. And it still does.” “Irresponsibly innocent”—I like that. It suggests someone smart enough not to be hoodwinked, but also someone who refuses to let his soft heart get crushed or his clean soul get sullied. Even if it’s risky, emotionally and spiritually, he will preserve his innocence in this fallen world. Yours, too, if you’ll open your ears and hearts and let him in.

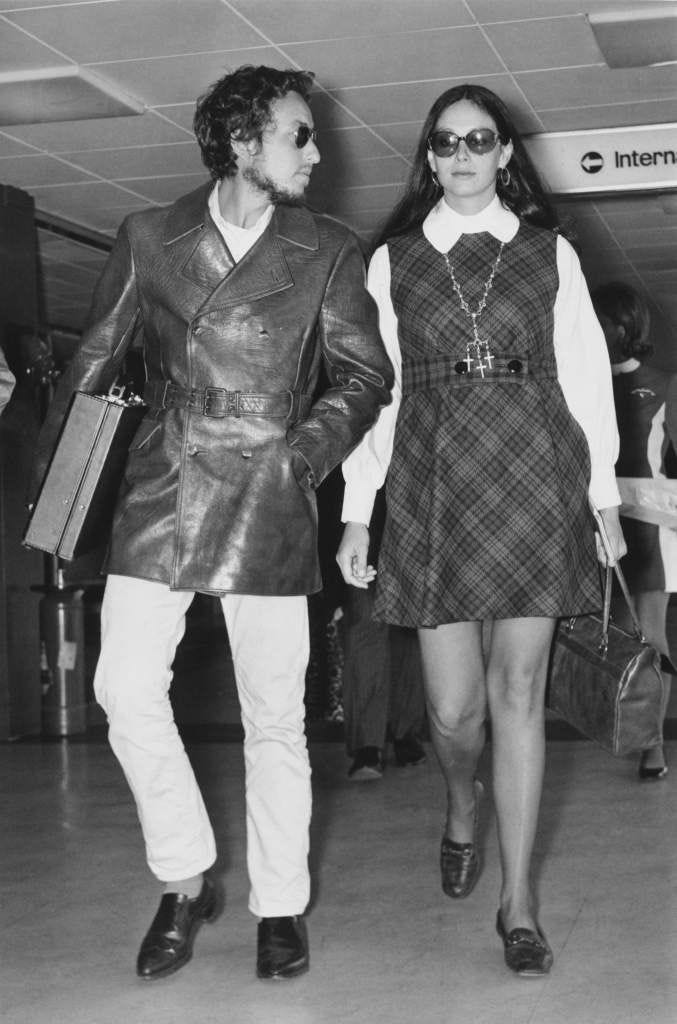

This is the tender vulnerability Dylan lets show in “Girl from the North Country” [“I wonder if she remembers me at all / Many times I’ve often prayed / In the darkness of my night / In the brightness of my day”] and “To Ramona” [“And someday maybe / Who knows, baby / I’ll come and be cryin’ to you”] and “Just Like a Woman” [“Please don’t let on that you knew me when / I was hungry and it was your world”]. It’s the threadbare Dylan hunched up on a snowy street clinging to Suze Rotolo for warmth in photos from The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan. It’s the chic and ultracool yet warm-vanilla-sugar sweetness that we’re all anticipating from Timothée Chalamet’s Dylan in the biopic A Complete Unknown. And it’s the Dylanesque vibe Mitchell goes for in New Orpheus. We need to admire him as an artist and rebel leader, but we also need to be utterly enchanted by him, like the way we all crush so hard on our boo Bob.

The irresponsible innocence of Orpheus makes him comically adorable at times in Hadestown. I love the scene where he first meets Eurydice in “Come Home with Me.” At first she mistakes him for a dimwit with no game. The wing-footed mentor Hermes tries to play wingman for his young protégé, but Orpheus wears his heart on his sleeve and won’t play it cool:

Hermes: You wanna talk to her?

Orpheus: Yes

Hermes: Go on . . .

Orpheus—

Orpheus: Yes?

Hermes: Don’t come on too strong

Orpheus & Chorus: Come home with me

Eurydice: Who are you?

Orpheus & Chorus: The man who’s gonna marry you

Orpheus: I’m Orpheus!

Eurydice (to Hermes): Is he always like this?

Hermes: Yes

Eurydice (to Orpheus): I’m Eurydice

Orpheus & Chorus: Your name is like a melody . . .

Eurydice: A singer? Is that what you are?

Orpheus: I also play the lyre.

Eurydice: Ooh, a liar and a player too!

I’ve met too many men like you (31-32)

Orpheus displays the unabashed love for Eurydice that Dylan’s Orphic singer expresses for his absent lover in “I Want You.” You can see how Mitchell is already setting up the later chapter in the saga with Orpheus’s first words “Come home with me”—the same plea he’ll make when trying to lead Eurydice out of the underworld. For now, “come home with me” is a wedding proposal. Why would she accept? “Because he’ll make you feel alive,” Hermes answers. Eurydice replies, “Alive . . . That’s worth a lot” (33). It’ll be worth even more after she’s dead.

But her first impulse is to dismiss Orpheus as a liar and a player. Hermes assures her she’s wrong. “He’s not like any man you’ve ever met.” For he’s not just any singer—he’s the greatest singer who ever lived, and he’s working on his masterpiece:

A song to fix what’s wrong

Take what’s broken, make it whole

A song so beautiful

It brings the world back into tune (33)

Orpheus is no fool: he is a hero. His heroic quest will lead him to the underworld to try and save Eurydice. As a singer, he’s on an even more ambitious quest to try and save the world.

In his book Bob Dylan: Prophet, Mystic, Poet, Seth Rogovoy traces a likeminded mission in Dylan’s work: “The concept that we live in a world where everything is broken—and that it is mankind’s task to repair the brokenness of the world—is central to Jewish mysticism. […] This process of repairing the world is called tikkun olam, literally ‘fixing the universe’” (253-54). I don’t know how familiar Mitchell is with tikkun olam in a Jewish context, as Dylan surely is through his involvement with Lubavitcher Hasidism. But she definitely depicts the world of Hadestown, above and below, as broken and out of harmony. The hero who is both bold enough and innocent enough to repair the damage through song is a distinctly Dylanesque Orpheus.

If Dylan provides a model for Orpheus’s heroic traits, however, his underworld songs also share Orpheus’s tragic flaw: Doubt.

Hades recognizes what a serious threat Orpheus poses. If the workers keep listening to his song and rise up in rebellion, Hades will lose everything:

Give them a piece and they’ll take it all

Show them the crack and they’ll tear down the wall

Lend them an ear and the kingdom will fall

The kingdom will fall for a song (182)

When Hades agrees to let Orpheus try and escape the underworld with Eurydice, it’s not a purely altruistic gesture out of the goodness of his bad heart. He knows how corrosive suspicion can be, since he is consumed by jealousy, paranoia, and possessiveness whenever his own wife Persephone is in the overworld. He reflects,

Nothing makes a man so bold

As a woman’s smile and a hand to hold

But all alone, his blood runs thin

And doubt comes

Doubt comes in (224)

So he attaches a fateful condition to the deal, one designed to undermine the venture and snuff out the rebellion. Hermes breaks the news to Orpheus and Eurydice:

Hermes: Well, the good news is

He said that you can go

Eurydice: He did?

Orpheus & Workers: He did?

Hermes: He did . . .

There’s bad news, though

Eurydice: What is it?

Hermes: You can walk . . .

But it won’t be like you planned

Orpheus: What do you mean?

Eurydice: Why not?

Hermes: Well, you won’t be hand in hand

You won’t be arm-in-arm

Side by side, and all of that (225)

They won’t be reenacting the cover of The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan. How will this work then?

Hermes (to Orpheus): He said you have to walk in front

And she has to walk in back

Orpheus: Why?

Hermes: And if you turn around

To make sure she’s coming too

Then she goes back to Hadestown

And ain’t nothing you can do (226)

Strange stipulation, but this shouldn’t be a huge problem, right? If you’re brave enough to sneak into the underworld, talented enough to win an audience with the king and queen, wily enough to coax a refund out of the old miser, and talented enough to sing your way out of hell with your bride right behind you, then surely you can keep your eyes on the prize and Don’t Look Back. Tragically, time will tell just who has fell and who’s been left behind when Orpheus goes his way and Eurydice goes hers.

Hades finds the Achilles heel for Orpheus, and doubt comes in. Orpheus worries he’s being set up and is incapable of outwitting the underworld god. But the doubt that gnaws at him most is that Eurydice is no longer following him. Finally, he can’t fight the demons any longer. He looks back. In so doing, he cuts his connection to Eurydice and loses her to the underworld.

Before looking back, Reeve Carney’s Orpheus asks aloud, “Where is she? Where is she now?” (239). Go back and listen to the 2010 album, however, and Justin Vernon’s interrogation in this climactic song is much more insistent, and the phrasing is more telling:

Where are you? Where are you now?

Doubt comes in

And kills the lights

Doubt comes in

And chills the air

Doubt comes in and falls silent

It’s as though you aren’t there

Where are you? Where are you now? (emphasis added)

Mitchell appears to directly echo two of Dylan’s best underworld songs, “Absolutely Sweet Marie” from Blonde on Blonde (1966) and “Where Are You Tonight? (Journey through Dark Heat)” from Street-Legal (1978).

“Absolutely Sweet Marie” doubles the mythic underworld with a criminal underworld. The singer is a prisoner who broods upon his faithless lover and criminal accomplice who hung him out to dry. She got away with the plunder, retained her freedom, and, he fears, found a new man to enjoy the booty with. Meanwhile, he is stuck alone in jail with his jealousy, bloodlust, and impotent desire:

Well, six white horses that you did promise

Were fin’lly delivered down to the penitentiary

But to live outside the law, you must be honest

I know you always say that you agree

But where are you tonight, sweet Marie? (emphasis added)

He poses the same question at the end of each refrain, though he already knows the answer:

Now, I been in jail when all my mail showed

That a man can’t give his address out to bad company

And now I stand here lookin’ at your yellow railroad

In the ruins of your balcony

Wond’ring where are you tonight, sweet Marie?

That railroad might as well be the road to hell, and that jail cell might as well be death row in Hadestown. The chances of Sweet Marie returning to the singer are the same as Eurydice returning to Orpheus: sweet fuck all. And in Orpheus’s case, he really has no one to blame but himself.

“Doubt Comes In” resonates even more strongly with “Where Are You Tonight? (Journey through Dark Heat),” one of Dylan’s most powerful underworld songs. The subtitle marks this song from the start as a descent into hell. In the first verse the singer pines for his lost love: “There’s a woman I long to touch and I miss her so much / But she’s drifting like a satellite.” Throughout the song, he looks for an escape route from hell, back to heavenly bliss: “There’s a white diamond gloom on the dark side of this room / And a pathway that leads to the stars.” But it’s not easy: “If you don’t believe there’s a price for this sweet paradise / Remind me to show you the scars.” This woman is an emblem of faith and love, and the singer pleads to her in the same language Mitchell’s Orpheus uses for Eurydice: “Where are you tonight?”

Unfortunately, doubt comes in. Dylan’s singer has his faith tested by warring impulses. He is drawn into the dark heat of desire through a shady urban underworld. He admits his temptation in the second verse:

There’s a neon light ablaze in this green smoky haze

Laughter down on Elizabeth Street

And a lonesome bell tone in that valley of stone

Where she bathed in a stream of pure heat

As the song progresses, temptation becomes harder to resist: “As her beauty fades and I watch her undrape / I won’t, but then again, maybe I might.” Eventually, he gives in, with imagery that links his story to the archetypal myth in the Garden of Eden: “I bit into the root of forbidden fruit / With the juice running down my leg.”

Notice how similar Mitchell’s Hadestown imagery is to Dylan’s allegory of faith vs. doubt. Hades describes his desire for Persephone as a furnace, a metaphor that he makes literal by building a giant foundry in the underworld:

And then I kept that furnace fed

With the fossils of the dead

Lover, when you feel that fire

Think of it as my desire

Think of it as my desire for you (100)

One typically associates the underworld with darkness, and in a metaphysical sense that’s accurate. However, both Dylan and Mitchell light their respective hells in strip-club neon, a glare designed to mask the despair of the damned who dwell there. As Hades tells Persephone,

When I made the neon shine

Silver screen, cathode ray

Brighter than the light of day

Lover, when you see that glare

Think of it as my despair

Think of it as my despair for you (102)

When doubt comes in, Hades paints it, like Dylan, from a palette of furnace heat and neon light.

Dylan and Mitchell’s underworld songs dramatize Orpheus’s doubt in Eurydice, but at bottom they are both primarily about Orpheus’s self-doubt in Orpheus. The most telling lines of “Where Are You Tonight?” appear in the middle of the song: “I fought with my twin, that enemy within / ’Til both of us fell by the way.”

When biographer Robert Shelton asked Dylan about this song, he reflected, “‘a man is his own worst enemy, just as he is his own best friend. If you can deal with the enemy within, then no enemy without can stand a chance.’” Shelton followed up by asking if Dylan could put his finger on his own enemy within. Dylan laughed, placed his index finger on his heart, and answered “‘Suspicion.’” He directed Shelton to “Where Are You Tonight?” as a song about “the mortal battle with his alter ego” (481).

In Hadestown, Hermes frames Orpheus’s test in exactly the same terms, as an inner struggle against the enemy within:

The meanest dog you’ll ever meet

He ain’t the hound dog in the street

He bears some teeth and tears some skin

But brother, that’s the worst of him

The dog you really got to dread

Is the one that howls inside your head

It’s him whose howling drives men mad

And a mind to its undoing (229)

I can’t hear Hermes’s warning without thinking of Dylan’s “One Too Many Mornings.” That early song from The Times They Are A-Changin’ describes a singer torn between staying with his current lover or leaving to pursue a new muse. The external conflict between competing lovers begins as an internal conflict in the singer’s mind:

Down the street the dogs are barkin’

And the day is a-gettin’ dark

As the night comes in a-fallin’

The dogs’ll lose their bark

An’ the silent night will shatter

From the sounds inside my mind

For I’m one too many mornings

And a thousand miles behind

I have to think that Mitchell had Dylan’s imagery at the back or front of her mind when penning Hermes’s lines about the hellhounds of the mind.

Switching from a dog metaphor to a road metaphor, Hermes counsels Orpheus that his ultimate heroic quest involves a journey inward to battle his own inner demons:

You got a lonesome road to walk

And it ain’t along the railroad track

And it ain’t along the blacktop tar

You’ve walked a hunnert times before

I’ll tell you where the real road lies

Between your ears, behind your eyes

That is the path to Paradise

Likewise the road to ruin (231)

This characterization fits perfectly with Joseph Campbell’s understanding of mythic quest. In The Hero with a Thousand Faces, Campbell asserts, “The passage of the mythological hero may be overground, incidentally; fundamentally it is inward—into depths where obscure resistances are overcome, and long lost, forgotten powers are revivified, to be made available for the transfiguration of the world” (29). Those resistances may be overcome in some myths, but not in Orpheus and Eurydice, not in Hadestown, and not in “Where Are You Tonight?”

The final verse of Dylan’s song portrays the singer’s reemergence into the light and the land of the living. Sadly, his lover didn’t make it through with him:

There’s a new day at dawn and I’ve finally arrived

If I’m there in the morning, baby, you’ll know I’ve survived

I can’t believe it, I can’t believe I’m alive

But without you it just doesn’t seem right

Oh, where are you tonight? (emphasis added)

Likewise, Mitchell’s Orpheus fails the inner test of faith and love, and Eurydice pays the price. Dylan and Mitchell’s underworld songs both dramatize the psychomachia of a singer besieged by doubts. He can’t truly believe that his lover will remain faithful because he feels unworthy of her love. He convinces himself that she must prefer someone else and will eventually wise up and move on. His suspicion sabotages the relationship and turns his doubt into a self-fulfilling prophecy. When he looks back, he fires a preemptive strike against their love. He’s so convinced that she’ll betray him that he betrays her first, with catastrophic results.

The myth of Orpheus and Eurydice ends tragically, but Hadestown does not. Mitchell won’t let it. When Orpheus fails and Eurydice returns to the underworld, it’s a crushing moment. Hermes gives voice to this grievous loss, but he also guides spectators and listeners through it to something more redemptive.

André De Shields turned in a star performance as Hermes, winning the 2019 Tony for Best Actor in a Featured Role in a Musical, and owning the stage of the Walter Kerr Theatre until he stepped away from the role in May 2022. [Incidentally, he participated in a staged reading from Dylan’s The Philosophy of Modern Song at 92NY in July 2023. Check out this review by Rebecca Slaman.]

Hermes is the communications director within the play, informing the audience who’s who and what’s what. At times he also plays messenger and mentor. Hermes is to Mitchell’s Hadestown what Virgil is to Dante’s Inferno, what the Stage Manager is to Thornton Wilder’s Our Town, what Dr. Walker is to Conor McPherson’s Girl from the North Country. He is the narrator who holds the story together, the engineer who guides the train down the tracks. After the catastrophe, Hermes becomes the mourner in chief.

He can barely keep it together in the immediate aftermath of the failure. In a barely audible and defeated voice, he concedes,

It’s an old song

It’s an old tale from way back when

It’s an old song

And that’s how it ends (246)

But as he pulls himself together and reflects further, he corrects himself. That’s not how it ends, not exactly, because the song that commemorates what happened lives on.

It’s a sad song

It’s a sad tale; it’s a tragedy

It’s a sad song

But we sing it anyway

Cos here’s the thing

To know how it ends

And still begin

To sing it again

As if it might turn out this time

I learned that from a friend of mine (246)

The song lives on. The story it commemorates is sad, but the endurance of the song itself lends strength, resilience, and hope.

Hermes’s message gets through to the company on stage, and they slowly spring back to life, raising their voices to join the song. Orpheus failed to bring Eurydice back, it’s true, and that is tragic. But Orpheus also leaves behind his inspirational songs and serves as a model for others to follow, turning abject defeat into a musical triumph.

Hermes: He could make you see how the world could be

In spite of the way that it is

Can you see it?

Company: Mmm . . .

Hermes: Can you hear it?

Company: Mmm . . .

Hermes: Can you feel it like a train?

Is it comin’?

Is it comin’ this way? (247)

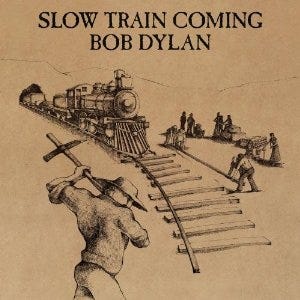

Yes! You better believe we can see it and hear it and feel it. Hermes preaches in the defiant, prophetic voice of “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall”: “And I’ll tell it and think it and speak it and breathe it / And reflect if from the mountain [or the underworld, or the stage] so all souls can see it.” How does it feel to ride that train? It feels like a song by Dylan, “Slow Train” to be precise [“There’s a slow, slow train comin’ up around the bend”], a song Hermes seems on the verge of quoting in the lines above.

The play has come full circle, back to the prologue when the characters arrived on that train in “Road to Hell.” Since then, they have taken the audience on a journey to hell and back. In “Road to Hell Reprise”—OED reprise: music: “A return to the first section of a composition or movement after an intervening and contrasting section”—Hermes resets Hadestown, returning us to the beginning, ready to embark upon the quest all over again. All aboard!

Let me circle back to a point I made in the previous installment: myths specialize in ritual repetition, not resolution. The train tracks in “Road to Hell” lead in both directions and run in a continuous loop. Follow that line to its terminus and you’ll find yourself in hell among the dead. Reverse course to the original station of departure and, lo and behold, you’re livin’ it up on top. The tale of Orpheus and Eurydice makes for a sad song, sure, but it’s also a love song, modeled after the love song of Hades and Persephone that came before. It’s an old song because it continues to tell a story we need to hear about faith and doubt, love and loss, life and death. As Mitchell writes it and Hermes and company belt it out:

Hermes: It’s an old, old, old tale from way back when

And we’re gonna sing it

Company: Again and again

Hermes: We’re gonna sing it again (250)

If you don’t believe it, buy a ticket to the Walter Kerr Theatre tomorrow night and go see for yourself.

Orpheus identifies with the experiences of Hades and Persephone. He sees the god’s desires and dilemmas reflected in his own, so he adapts that prior melody to fashion a new song rooted in the old. Mitchell adopts this same approach in Hadestown, not only by drawing upon the archetypal descent into the underworld and the ancient myth of the world’s greatest singer Orpheus, but also by drawing upon the songs, imagery, themes, and iconic persona of Bob Dylan, our closest approximation to a modern-day New Orpheus. That’s how myth works, and that’s how the folk process works. It’s an old song, and we’re gonna sing it again.

Mitchell isn’t done singing those songs, and neither is Dylan. In the years since Hadestown premiered on Broadway in 2019, the elder bard has renewed his interest in descent narratives and songs of the underworld. In the third and final installment of this series, we’ll follow the ancient footsteps that lead Dylan back to the underworld in Rough and Rowdy Ways (2020) and Shadow Kingdom (2021).

Works Cited

Allen, Mel. “The Road to Hadestown with Vermont’s Anaïs Mitchell.” NewEngland.com (27 December 2019), https://newengland.com/yankee/the-road-to-hadestown-anais-mitchell/.

Campbell, Joseph. The Hero with a Thousand Faces. Princeton, NJ: Princeton UP, 1949.

D’Aulaire, Ingri and Edgar Parin. Book of Greek Myths. Bantam Doubleday Dell, 1962.

Dylan, Bob. Chronicles, Volume One. Simon & Schuster, 2004.

---. Official Song Lyrics. The Official Bob Dylan Website,

http://www.bobdylan.com/.

Hadestown (Original Broadway Cast Recording). Sing It Again, 2019.

Mitchell, Anaïs. Hadestown. Righteous Babe, 2010.

---. Working on a Song: The Lyrics of Hadestown. Plume, 2020.

Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford University Press, 2023.

Rock & Roll Hall of Fame. “Bruce Springsteen inducts Bob Dylan Rock and Roll Hall of Fame Inductions 1988. YouTube (11 February 2010).

Rogovoy, Seth. Bob Dylan: Prophet, Mystic, Poet. Scribner, 2009.

Shelton, Robert. No Direction Home: The Life and Music of Bob Dylan. Beech Tree Books, 1986.

Slaman, Rebecca. “The Philosophy of Modern Song.” Bawker (18 July 2023),

.

van der Ven, Matthijs. “Sessions: Anaïs Mitchell.” Influences (24 May 2019), https://theinfluences.com/anais-mitchell/.

Loving this series! When I was first getting into Dylan, I noticed connections between Love Minus Zero and Hades & Persephone’s relationship in the musical. The flowers, the wall, the pawns!