To Hell and Back: Bob Dylan & Anaïs Mitchell’s Underworld Songs

Part 3: Rough and Rowdy Ways & Shadow Kingdom

In 1962, the same year that Columbia Records released Dylan’s debut album, Doubleday Books published the first edition of Ingri and Edgar Parin D’Aulaires’ Book of Greek Myths. This beloved children’s classic combines beautiful illustrations with accessible stories from ancient Greek mythology. The book gave Anaïs Mitchell an early foothold in these myths. I wouldn’t be surprised if Bob and Sara Dylan read it to their kids at bedtime, too, when they weren’t playing basketball in the kitchen or banging on pots and pans (Chronicles 118).

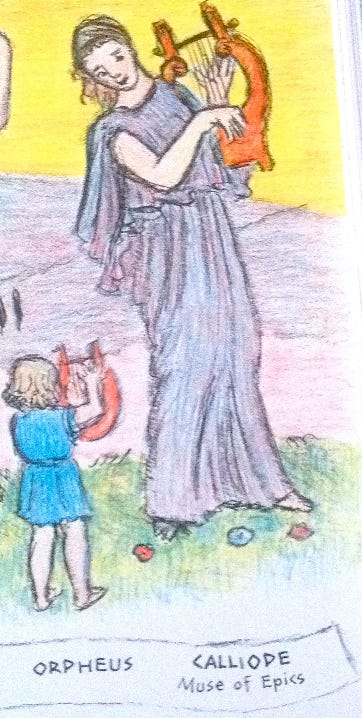

The D’Aulaires include a lovely picture of the Muses:

The picture is accompanied by this story:

The nine Muses were daughters of Zeus and the Titaness Mnemosyne. Their mother’s memory was as long as her beautiful hair, for she was the goddess of memory and knew all that had happened since the beginning of time. She gathered her nine daughters around her and told them wondrous tales. […] The nine Muses listened to her with wide and sparkling eyes and turned her stories into poems and songs so they would never be forgotten. (100)

Parents aren’t supposed to have favorites, but according to the D’Aulaires, one of the Muses was the first among equals and held in highest esteem by her mother Mnemosyne: “Each of the daughters had her own special art. Calliope, the Muse of heroic poetry, was the first among them. She had a mortal son named Orpheus, and he sang almost as beautifully as the Muses themselves” (101). You can see little Orpheus in the corner of the illustration, playing his lyre for Calliope. “When he was grown, he left his mother and his eight loving aunts and went to live in his father’s kingdom of Thrace to bring the joy of music to earth” (101).

This mythic family—Mnemosyne, the goddess of memory; Calliope, her daughter, the Muse of heroic poetry; and Orpheus, the grandson of memory, the son of epic, the singer responsible for bringing the joy of music to earth—has been much on Dylan’s mind of late. In “Mother of Muses,” he invokes Mnemosyne: “Mother of muses, sing for me.” In the same song, he pines, “I’m falling in love with Calliope.” What’s up with these specific classical references?

It started when he unexpectedly won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2016. The last line of Dylan’s Nobel Lecture is a quotation of the first line of Homer’s The Odyssey: “Sing in me, Muse, and through me tell the story.” Dylan delivered his lecture just ahead of the deadline, and he missed the Nobel ceremony entirely. He didn’t claim his award until the spring of 2017. The Guardian reported that Dylan met with a dozen academy members at a private event where he was presented with the Nobel medal. According to Sara Danius,

Quite a bit of time was spent looking closely at the gold medal, in particular the beautifully crafted back, an image of a young man sitting under a laurel tree who listens to the Muse. Taken from Virgil’s Aeneid, the inscription reads: Inventas vitam iuvat excoluisse per artes, loosely translated as “And they who bettered life on earth by their newly found mastery.”

In Why Bob Dylan Matters, Harvard classicist and noted Dylanologist Richard F. Thomas sheds light on the context and symbolism behind the medal.

The man we see here is not just any young man. He would seem to represent the poet Virgil, one of the shepherd singers of his poem Eclogue 1, ‘meditating the woodland Muse’ as he sings in the shade of a tree. The singer on the medal is likewise looking up at the Muse as she plays the seven-stringed lyre, or cithara as the Greeks and Romans called it—the word that gives us guitar. […] Like the image, the words engraved around the medal’s rim are also Virgil’s: Inventas vitam iuvat excoluisse per artes. In its larger context the line comes from a description of the privileged place that singers have deserved in Virgil’s version of paradise in Book 6 of his epic the Aeneid. (13-14)

To provide further context, consider that Book 6 chronicles Aeneas’s descent into the underworld. The passage quoted on the Nobel medal derives from the scene where Aeneas encounters the spirits of great poets and singers. Not surprisingly, Orpheus is chief among them. Unlike the Nobel medal, Virgil depicts Orpheus as the one playing the lyre. I’ll quote from Stanley Lombardo’s translation of Aeneid (endorsed on the back cover with a blurb from Richard Thomas):

And Orpheus,

In the long robes of a Thracian priest,

Accompanies them on his seven-toned lyre,

Plucking notes with his fingers and ivory quill. (Book 6, lines 766-79)

I agree with my good friend Laura Tenschert that these myths, epics, heroes, and muses continued to preoccupy Dylan after 2017 and deeply inspired the songs on his 2020 album Rough and Rowdy Ways. In the second chapter of her series on the album, Laura considers the image on the Nobel medal as an allegory for the creative process.

When you think about it, every artistic endeavor (and songwriting is no exception) exists somewhere between an inward and an outward impulse. On the one hand, there is within the artist a deep certainty that they must pursue their urge to create. And this act of creation, from the moment that inspiration strikes until the work is done, is one of focus and determination. It’s an intimate, personal, and often solitary process. On the other hand, songs need an audience. It’s the old “If a tree falls in the forest” question. Is a song even a song if no one hears it? So what I would call the outward aspect is related to the question of what happens to the song once it is created. How is it received? How many lives does it touch? I think that both these impulses, the inward and the outward, are beautifully represented by the image on the Nobel medal: the moment of creation (in the figure of the Muse), and the outward communal aspect expressed in the inscription from Virgil.

Spot on, Laura! These perceptive observations about inward and outward impulses send us back to that Homeric quotation from the Nobel Lecture: “Sing in me, Muse, and through me tell the story.” The singer is figured as a medium through which inspiration passes. Laura quotes multiple interviews where Dylan describes his role as just such a vessel, channel, or postman for delivering songs that originate from mysterious, divine sources beyond him. In effect, I suppose you could say that the artist is the lyre: the instrument gods use to communicate with mortals.

Dylan regards himself as a conduit through which the old songs and stories are retold, whether the source is divine inspiration, ancient myth, the boundless treasure of traditional music, or some combination. As we have seen in the first two episodes of this series, one of the old stories he keeps retelling is the archetypal descent into the underworld, and one of the mythic figures he reanimates is Orpheus.

John Mellencamp recently told a funny story in his New York Times interview with Rob Tannenbaum: “I’m going to quote Bob Dylan to you. Bob and I were painting together one day, and I asked him how he wrote so many great songs. In all seriousness, he said, ‘John, I’ve written the same four [expletive] songs a million times.’” One of those [expletive] songs is Orpheus’s descent into the underworld. Oh, by the way, Mellencamp was being interviewed to promote his new album . . . Orpheus Descending. I guess the pair were sharing more than paintbrushes.

The Nobel Prize surely served as one prompt for Dylan’s reflections on mortality and on the immortal art that survives death. As I’ve discussed in the first and second installments, I suspect that McPherson’s Girl from the North Country and Mitchell’s Hadestown were also catalysts and intertextual companions for Dylan’s musical journey. Laura tugs my sleeve toward another possible clue in the new lyrics Dylan penned for “You’re Gonna Make Me Lonesome When You Go” in Mondo Scripto. She posted a Definitely Dylan episode on Mondo Scripto when the exhibition was running at the Halcyon Gallery in London in 2018, and she is continuing her research on this underappreciated series. Here’s the verse that most intrigues me:

Moonlight hour in ol’ Vermont – maple syrup’s what I want

I can feel the fire down below

You crossed me out and hooked me up – with a bag of tricks and a golden cup

You’re gonna make me lonesome when you go

Granted, for me at this point all highways seem to lead to hell, and I can hear an echo of Orpheus and Eurydice in just about anything. When you’re swinging a hammer, everything looks like a nail. So I’m awfully tempted to see a wink at Vermont artist Anaïs Mitchell’s Hadestown in the lines above, going straight from Vermont to the fire down below, and composed around the same time as the Dylan works under examination in this post.

Since we can never say with certainty why Dylan does anything he does, we’re on firmer ground if we plant our feet in the art itself. In this final episode of the series, let’s consider how he treats the underworld theme in Rough and Rowdy Ways and Shadow Kingdom. Pack your gear and put on your walking shoes. Time to follow Dylan back down to hell.

Rough and Rowdy Ways

After establishing Dylan’s deep classical debts in Why Bob Dylan Matters, Richard Thomas was understandably delighted to find Dylan returning to these sources in new and rich ways on Rough and Rowdy Ways. In an article for The Dylan Review, he marveled,

Dylan’s astonishing new album shows that he has stayed with some of the ancients, drawing from them and from everything else in his arsenal in new ways in the process of producing an album that will take its place among the greatest he has given us. As with the book, here I explore just one part of his art, and in no way imply that Dylan is limited or bounded by his interest in antiquity. He contains multitudes; this album contains multitudes. That includes the classical world, evident in the lyrics of some of the new songs. (emphasis in original)

I share Thomas’s caveat. There are a lot of things going on in RARW, and Dylan makes a bevy of allusions. I freely acknowledge and fully celebrate the album’s wide range and diversity. I’m simply tracing one dark thread in Dylan’s coat of many colors, the thread that leads back to Orpheus and Eurydice and through the underworld.

The journey begins on the first song, “I Contain Multitudes,” which opens,

Today and tomorrow and yesterday too

The flowers are dying like all things do

Follow me close – I’m going to Bally-Na-Lee

I’ll lose my mind if you don’t come with me

I fuss with my hair and I fight blood feuds

I contain multitudes

It only took Dylan two lines to make his first reference to a death, a theme that he returns to frequently throughout the album. Dying flowers are a common enough poetic conceit, but one with specific connotations in underworld mythology. Persephone is the goddess of spring in the overworld, but she is the queen of hell in the underworld. The dying flowers signals the coming of winter, so we’re already put on notice that the latest descent into death is afoot.

Hadestown makes major use of flower imagery as well, particularly in connection to Eurydice. In her song “Flowers,” Eurydice describes her descent into death:

What I wanted was to fall asleep

Close my eyes and disappear

Like a petal on a stream

A feather on the air

Lily white and poppy red

I trembled when he laid me out

You won’t feel a thing, he said

When you go down (159)

She associates life above with blooming spring: “Flowers, I remember fields / Of flowers, soft beneath my heels” (159). Not so in the underworld: “Flowers bloom until they rot” (159). Correlation does not imply causation. Dylan had no shortage of literary and musical precedents to call upon for his dead flower imagery, from Persephone to Ophelia to “Dead Flowers” from “them British bad boys the Rolling Stones” (also referenced in “I Contain Multitudes”). It’s just one of a multitude of resonant echoes between Dylan and Mitchell’s work by way of Orpheus and Eurydice.

Another triangulation that leads us down the path to the underworld appears in the lines, “Follow me close – I’m going to Bally-Na-Lee / I’ll lose my mind if you don’t come with me.” When Dylan first released “I Contain Multitudes” as a single, he sent a lot of fans straight to their search engines to figure out this obscure allusion. Outside of Ireland, relatively few listeners knew that Ballinalee is a small town in County Longford. Click on its Wikipedia entry and you’ll learn that the town is mentioned in “The Lass from Bally-na-Lee” by Antoine Ó Raifteiri, a wandering Irish bard from the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

I’ll admit that I wasn’t familiar with this poem, but as a scholar and teacher of modern Irish literature, I am familiar with the figure of “Blind Raftery.” William Butler Yeats mentions him prominently in multiple works, most notably “The Tower.” I’m not alone in suspecting that Dylan triangulates his way back to Blind Raftery by way of Yeats.

Yeats lived in an Anglo-Norman tower in County Galway’s Ballylee, which is awfully close to the name Dylan uses in “I Contain Multitudes.” Thoor Ballylee (“Thoor” is Irish for “Tower”) became more than a residence for Yeats. It served as his personal stake in the noble but fractious history of Ireland, and as an emblematic inspiration for his poetry—most notably in the The Tower (1928) and The Winding Stair and Other Poems (1929)—his first poetry volumes published after he won the 1923 Nobel Prize in Literature. Yeats is the poet laureate of aging and mortality, and “The Tower” is perhaps his most profound meditation on what legacy he will leave behind, and how an aging poet can continue to create relevant art.

Yeats discusses Blind Raftery as a fellow muse poet. Raftery was inspired to write a love song about a local woman, and the song was so intoxicating to some listeners that a man actually died trying to seek out the enchantress from the song. As Yeats tells it in “The Tower,” “Music had driven their wits astray— / And one of them drowned in the great bog of Cloone.” The moral Yeats draws from this example is: “if I triumph, I must make men mad.” A man so drunk with love that he follows after a woman unto death. Sound familiar? It’s the old song of love and death sung by Raftery, sung again by Yeats, and sung yet again by Dylan. And it’s a variant of the Orpheus and Eurydice myth.

I was pleased (and reassured) to come across Niall Brennan’s blog post on High Summer Street while researching this piece. Brennan likewise connects “I Contain Multitudes” with Raftery and Yeats. In Brennan’s reading of “The Tower,” he finds,

Yeats makes a courageous attempt to explore his creative past, present and future in some detail. In the short opening section he writes of how he must “bid the Muse go pack” and “choose the sages Plato and Plotinus for a friend,” perhaps a reflection on how the Nobel recognition has now trapped him, has in effect made him into a kind of monument or mausoleum.

You can see why Dylan would be especially interested in revisiting an elderly laureate’s musings on these subjects in the aftermath of his own Nobel selection.

Like Yeats, Dylan was not ready to retire or “bid the Muse go pack” just because he won literature’s biggest lifetime achievement award. He ain’t dead yet, his bell still rings. But mortality weighs on his mind in Rough and Rowdy Ways. Once again, mythical figures and archetypal narratives provide guidance for his meditation. Dylan retraces the trail to the underworld, a descent that leads simultaneously downward and inward: “I’ll keep the path open – the path in my mind / I’ll see to it that there’s no love left behind.” Ah, but as Orpheus can attest, in order to see that no love is left behind, you first have to look back.

The Orphic singer of RARW is a man of many moods. In certain songs, he is filled with swaggering defiance. For instance, in “False Prophet” he saunters down to hell like he owns the joint. He’s puffed up and ready to take on all rivals:

I’m first among equals – second to none

I’m last of the best – you can bury the rest

Bury ’em naked with their silver and gold

Put ’em six feet under and then pray for their souls

He hasn’t come to hell on a holiday. He’s a man on a mission to outmaneuver the king and rescue his bride from oblivion and death.

You don’t know me darlin’ – you never would guess

I’m nothing like my ghostly appearance would suggest

I ain’t no false prophet – I just said what I said

I’m here to bring vengeance on somebody’s head

That somebody is Hades. The Orphic singer rolls into the underworld like Brando on his motorcycle in The Wild One. “Hello Mary Lou—Hello Miss Pearl / My fleet footed guides from the underworld.” The names of these underworld barmaids apparently derive from songs by Ricky Nelson and Jimmy Wages, but I also get a vibe of “My Boyfriend’s Back” by The Angels. Eurydice’s boyfriend is back, and Hades is gonna be in trouble.

The title figure in “Black Rider” is a personification of Death, so the family resemblance to Hades, the king of the dead, is unmistakable. The singer claims not to be intimidated by this Grim Reaper, however. On the contrary, the song is peppered with taunts. Some of the tension seems taken straight out of Orpheus’s epic conflict with Hades. The most striking example comes in the middle verse:

Black Rider Black Rider all dressed in black

I’m walking away and you try to make me look back

My heart is at rest I’d like to keep it that way

I don’t want to fight—at least not today

Go home to your wife stop visiting mine

One of these days I’ll forget to be kind (emphasis added)

The “don’t look back” allusion flashes like a neon sign pointing to its mythic source. I also love the penultimate line, which in this context reads as “Go home to Persephone and leave Eurydice alone.” As for the line, “One of these days I’ll forget to be kind,” that takes some unpacking. First, I’m intrigued by the unusual phrasing. He could have said what he would do to the Black Rider, instead of what he’d forget to do. I think he’s landing a subtle but effective jab related to memory and forgetting—crucial concepts in the underworld and in the world of RARW.

In ancient Greek mythology, the dead were ferried by Charon across the River Styx to Tartarus, first arriving in Asphodel Fields. I’ll let Robert Graves pick up the story from there: “Beyond these Asphodel Fields stood Hades’s towering cold palace. To the left of it grew a cypress tree, marking Lethe, the Pool of Forgetfulness, where ordinary ghosts flocked thirstily to drink. At once they forgot their past lives, which left them nothing whatever to talk about” (29). Note that “My Own Version of You” contains the instruction, “Stand over there by the Cypress tree.” If this tree is a location marker beside the Lethe, then instructing someone to stand beside the Cypress sounds like telling them to remain safe on the perimeter and not approach the Pool of Forgetfulness. Stop—don’t drink. In Working on a Song, Mitchell described memory loss as the scariest part of Hadestown: “I found that what had always frightened me most about the underworld was the idea of ‘forgetting.’ The dead are made to drink of the waters of the River Lethe, which causes them to forget their former lives. This was the river of oblivion in ‘Way Down Hadestown Reprise’” (157, emphasis in original).

Not every shade in Tartarus is doomed to permanent oblivion, however, and they have Orpheus to thank for their reprieve. Graves explains that “ghosts who had been given a secret password by Orpheus, the poet, whispered it to Hades’s servants, and went instead to drink from Mnemosyne, the Pool of Memory, marked by a white poplar. This allowed them to discuss their past lives, and they could also foretell the future” (Graves 29).

Orpheus, you rascal! According to this version of the myth, Orpheus didn’t just challenge Hades’s authority the one time by trespassing into the underworld and trying to charm his wife away. He had a scam running down there among the shades, sharing his secret password, hacking the firewall, sneaking friends out of the memory-wiping Lethe and into the memory-enhancing Mnemosyne, granting the elect not only the liberty to discuss the past, but even bestowing the superpower to foretell the future. No wonder Hades has it in for him!

These two are rivals, and the animosity is mutual. Given this context, “One of these days I’ll forget to be kind” is a shiv in the Black Rider’s ribs, a stiletto-pointed insult from an underworld insurgent with privileged access to Memory. It’s as if Orpheus is bragging, “Yeah, you know I’ve got the Memory market cornered down here, King Hades. I’m Ticketmaster to Mnemosyne, lifeguard for the Pool of Memory. But one of these days I just might forget something. I might forget to be kind to your punk ass!” What he actually sings is more subtle but no less cutting: “Some enchanted evening I’ll sing you a song / Black Rider Black Rider you’ve been on the job too long.” Sounds less like a serenade and more like a threat.

Memory features even more prominently in the song “Mother of Muses.” Here the reference isn’t to the pool in the underworld but to the goddess of memory, Mnemosyne, who is also the mother of Calliope and grandmother of Orpheus. Guess that’s where he learned to secret password, eh?

Mother of Muses sing for me

Sing of the mountains and the deep dark sea

Sing of the lakes and the nymphs in the forest

Sing your hearts out—all you women of the chorus

Sing of honor and fame and of glory be

Mother of Muses, sing for me

We heard Dylan invoking the muse at the end of his Nobel Lecture, echoing Homer’s invocation at the beginning of The Odyssey. But this time he offers a variation. Although he later declares his love for Calliope by name, it’s not the Muse of epic poetry he calls upon in this song but rather her mother. Why? I like Laura Tenschert’s explanation:

Mnemosyne was one of the Titans, and she was considered really important. It’s easy to understand why when we think of the crucial role that memory played in the time before writing, when all important information, and even the long epic poems, had to be relayed orally from memory. So the fact that Dylan is calling on Mnemosyne in the song means essentially that the singer is calling on Memory personified. Consequently, he is not actually asking for inspiration, but he is asking to remember.

This makes me wonder if Dylan switched editions of Homer. His quotation in the Nobel Lecture comes from Robert Fitzgerald’s translation: “Sing in me, Muse, and through me tell the story.” However, Stanley Lombardo’s more colloquial translation distills down the first line to read simply: “Speak, Memory—” (Book 1, line 1).

Throughout Rough and Rowdy Ways, the singer’s guiding motive is that of Orpheus: to bring the dead back to life by way of song. Dylan enacts the culmination of this quest in the final three songs: “Crossing the Rubicon,” “Key West (Philosopher Pirate),” and “Murder Most Foul.”

The Rubicon is a real river in northern Italy, but it has come to represent much more ever since Julius Caesar crossed it with his army and triggered a clash with the Roman Senate that would lead to civil war, his rise as dictator, and his eventual murder. Dylan uses the Rubicon in this emblematic sense of making a fateful decision and crossing a liminal threshold from one reality into another. The Rubicon doubles here as the River Styx, crossing from life into death. When he sings, “I abandoned all hope and I crossed the Rubicon,” you probably picked up on the nod to another famous descent narrative, Dante’s Inferno, with its warning inscribed on the gates of hell: “Abandon all hope, ye who enter here.”

All hope is not lost for Dante, however, nor is it for Dylan. After all, Inferno is only the first book in The Divine Comedy trilogy, followed by Purgatorio and ultimately Paradiso. Dylan provides his vision of heaven in the album’s penultimate song, “Key West (Philosopher Pirate).” The song begins with the assassination of another leader, this time U.S. President William McKinley. But the gods are apparently kind to the ghost of the Ohio native, sending him to warmer climes way down in Key West. “Key West is the enchanted land,” Dylan informs us; or, even more explicitly, “Key West is paradise divine.” Death might be the price of admission, but once you pay the ferryman, “Key West is the place to be / If you’re lookin’ for immortality.”

As Jim Salvucci reminds us, Florida is the legendary home of the Fountain of Youth, which helps account for the zip code Dylan chooses for his vision of ageless vitality. But Dylan’s Key West also looks backward, eastward, and downward. Given the ubiquitous references to the classical underworld on the album, Larry Fyffe makes a solid case on Untold Dylan for reading Key West as Dylan’s translation of the underworld’s Elysian Fields.

Rough and Rowdy Ways would be a different album if it ended there, coasting into paradise. Instead, having conjured up this dreamscape of light, love, happiness, and immortality, Dylan then abruptly shifts course. He plunges the listener into the “nightmare on Elm Street,” that “dark day in Dallas – November ’63” when the “soul of a nation [was] torn away” by the assassination of President John F. Kennedy.

In Folk Music: A Bob Dylan Biography in Seven Songs, Greil Marcus argues that “Murder Most Foul” is narrated by the slain president as he crosses over into death: “you’re listening in to John F. Kennedy’s brain after the president-for-five-more-seconds has first been hit but before he’s killed, arguing with his assassins as if there’s still time to talk them out of it” (227). It’s a fascinating interpretation by Marcus, and an extremely bold move by Dylan if he is indeed channeling the voice of the inspiring/expiring leader of his generation. The theory holds up at moments like this:

Ridin’ in the back seat, next to my wife

Heading straight on into the afterlife

I’m leaning to the left, got my head in her lap

Oh Lord, I’ve been led into some kind of trap

At other moments, however, particularly in the spellbinding final stanza of the song, I hear other voices echoing in “Murder Most Foul.” By this point in the underworld series, you won’t be surprised to learn that one of those voices belongs to Orpheus.

The spirit heading into death is Kennedy, but it’s not only Kennedy. There’s a lot of metempsychosis at work in “Murder Most Foul.” This dying hero has many faces and speaks in many tongues. For starters, he stands in the shoes of other slain presidents, from Lincoln to Garfield to McKinley. “The day they blew out the brains of the king / Thousands were watching, no one saw a thing.” As Andrew Muir astutely observes, “Murder Most Foul” also integrates the foul murders of three kings from Shakespeare’s plays Hamlet, Macbeth, and Julius Caesar.

The spirit slowly floating down to the underworld is also a singer. The final stanza is the longest and most powerful in “Murder Most Foul,” and it’s also the most haunted with allusions. This section is framed as a series of song requests for the famous disc jockey Wolfman Jack. Whoever is making these requests possesses an encyclopedic knowledge of songs. Furthermore, several of these requests extend beyond 1963, which is to say after Kennedy died.

Whose musical knowledge extends so deep and wide? For one, Bob Dylan. When the dead hero is described as “a hard act to follow, second to none,” we hear the echo from Dylan’s boast in “False Prophet”: “I’m first among equals – second to none.” Few readers of Shadow Chasing would challenge Dylan’s claim if he’s talking about himself and comparing himself to his contemporaries. But in the grand scheme of things, perhaps he is second to one singer, the greatest of them all. I’m referring of course to the mythical singer who brought music to earth and then brought it down to the underworld as well, a hero who needs no introduction by now.

One of the many layers of meaning Dylan adds to the palimpsest of “Murder Most Foul” seems to come from the brutal murder of Orpheus. Recall from my first installment how the singer’s stoning in “Rainy Day Women #12 & 35” seems modeled in part after Orpheus’s murder by the Maenads. Let’s pick up that story where I left off in Book 11 of Metamorphoses. The Maenads do more than stone Orpheus—they rip him to shreds. According to Ovid, the whole world mourns this murder most foul:

The mourning birds wept for you, Orpheus,

The throngs of animals, the flinty rocks,

And the woods that had so often followed your songs,

The trees shedding their leaves as they grieved for you

With heads shorn. They say that rivers were swollen

With their own tears, and that nymphs of wood and stream

Wore black and grey and kept their hair disheveled. (Book 11, lines 45-51)

This same cast of characters sings a threnody in Rough and Rowdy Ways: in the falling leaves of “Crossing the Rubicon” [“The killing frost is on the ground the autumn leaves are gone”]; in the crying trees of “My Own Version of You” [“I say to the willow tree – don’t weep for me”]; in the keening river of “I’ve Made Up My Mind to Give Myself to You” [“My heart’s like a river – a river that sings”]; in the forest nymphs of “Mother of Muses” [“Sing of the lakes and the nymphs of the forest / Sing your hearts out – all you women of the chorus”]. Hell, Dylan even includes the disheveled hair in “I Contain Multitudes” [“I fuss with my hair and I fight blood feuds”].

All of nature sings a lamentation for Orpheus after his murder. Most astounding of all, the severed head of Orpheus continues to sing even as it floats toward its final resting place:

His limbs lay all over the fields, but his head and lyre

Were received by you, O Hebrus, and as they floated

Downstream, his lyre—it was a miracle—

Played mournful notes, and his lifeless tongue

Murmured mournfully, and mournfully the banks replied. (Book 11, lines 52-56)

Orpheus’s final swan song, his posthumous self-elegy, delivered as he follows the river and returns to the underworld for good this time—that’s what I hear now when I listen to “Murder Most Foul.” It’s a dirge for Kennedy and for the death of the hopeful sixties generation he inspired. It’s one more Muse-inspired epic for slain heroes, both ancient and modern, who fought the good fight and went down for a righteous cause. It’s a contemplation of the inevitable decay and death that awaits us all.

But it’s also a lasting monument to the power of song and those who sing them. Songs outlive singers and confer a kind of death-defying immortality. Dylan communicates this through the content of the song, reeling off requests from several singers who are no longer alive; but he also communicates it through the song’s form, a musical Möbius strip that in theory never ends. I share Laura Tenschert’s view in “‘Today and Tomorrow and Yesterday Too’: Time in Bob Dylan’s Work of the 2020s”: “In the song’s final lines, Dylan’s request to DJ Wolfman Jack to ‘Play the Blood Stained Banner – Play Murder Most Foul,’ doubles as a prompt to the listener to play the song from the beginning again, to rewind the clock, undo death, only for the story to unfold from the beginning again” (180). It’s a sad song, but he’s gonna sing it again, and we’re gonna listen.

“Murder Most Foul” is the song Orpheus would have sung if he’d been born in America in 1941.

I’m reminded of a story Anaïs Mitchell tells in Working on a Song about an outtake from Hadestown. “I can remember André De Shields singing these words in a workshop, and I’m not sure why, but they still make me cry. It has to do with how many times I rewrote the ‘Epics,’ and still, they never felt finished. It has to do with artists the whole world over, restlessly pursuing their work” (55). These are the lines:

Orpheus was a poor boy

But he had a gift to give us

There was one song he’d been working on

He could never seem to finish

A song about this broken world

That he rewrote again and again

As though if he could find the words

He could fix the world with them. (55)

This is such a powerful notion: the endless search for the right song that can repair the broken world. It’s the mission behind the Jewish mystical concept of tikkun olam, referenced in the previous episode, that seems to drive a lot of Dylan’s work. “Murder Most Foul” is a devastating song delivered in somber tones by a voice that sounds otherworldly, as if speaking from beyond the grave. Yet I sense a restorative impulse behind the song, too.

Dylan dramatizes a nation-shattering, cosmos-altering event of violent destruction, and then he tries to piece something back together from the shards that remain after the detonation. What he produces in the final section of “Murder Most Foul” sounds fragmentary and random. He’s just picking up whatever pieces survived the blast and trying to reassemble them. By the end it’s hard to say whether he succeeds or fails, but goddammit he tries. Give him that. He keeps trying. The king is dead, long live the king. In this broken world, may the circle of song be unbroken.

Shadow Kingdom

When Justin Vernon played Orpheus on the 2010 album Hadestown, he sang these lines in “Epic, Part 1” to describe Hades: “King of diamonds, king of spades / Hades was king of the kingdom of dirt.” However, as Mitchell mentions above, she spent more time revising the “Epics” than any other portion of the musical. By the time Hadestown made it to Broadway in 2019, the New Orpheus played by Reeve Carney described Hades this way: “King of shadows / King of shades / Hades was king of the underworld” (49, 198). Enter Shadow Kingdom!

Mind you, we still can’t confirm that Dylan has seen Hadestown. This could be another case of triangulation, where he isn’t drawing upon Mitchell directly but rather they’re both drawing upon an older source text. Shakespeare is a likely candidate. The Bard of Hibbing’s admiration for the Bard of Avon is well documented (see especially Andrew Muir’s Bob Dylan & William Shakespeare: The True Performing of It). I sometimes teach a Shakespeare course at Xavier, and I always include A Midsummer Night’s Dream. My first thought upon hearing the title of his streaming video event, Shadow Kingdom, was to hear an echo of MND. Puck refers to the fairy king Oberon as “king of shadows” (3.2.347).

The actor playing Puck also steps out of character in the play’s closing epilogue by referring to the performers as “shadows,” in the sense of mirror reflections of reality:

If we shadows have offended,

Think but this, and all is mended

That you have but slumber’d here

While these visions did appear. (5.1.409-12)

Furthermore, the surreal atmosphere of Shadow Kingdom, and the timing of its release during the summer of 2021, invites association with A Midsummer Night’s Dream. As you descend into Dylan’s shadowy kingdom, however, you’ll start to hear other familiar echoes. According to the closing credits, the fictional Bon Bon Club where Dylan performs is located in Marseilles. But other clues hint that the location is once again the mythic underworld.

Dylan opens with “When I Paint My Masterpiece.” The song conjures up classical Rome, the world of the Caesars, of Virgil’s Aeneid and Ovid’s Metamorphoses, a distant time that continues to shadow Dylan’s modern songs.

Oh, the streets of Rome are filled with rubble

Ancient footprints are everywhere

You can almost think that you’re seeing double

On a cold, dark night by the Spanish Stairs

Douglas Brinkley asked the maestro about “When I Paint My Masterpiece” in his 2020 New York Times interview, and Dylan offered an interesting reflection:

I think this song has something to do with the classical world, something that’s out of reach. Someplace you’d like to be beyond your experience. Something that is so supreme and first rate that you could never come back down from the mountain. That you’ve achieved the unthinkable. That’s what the song tries to say, and you’d have to put it in that context. In saying that though, even if you do paint your masterpiece, what will you do then? Well, obviously you have to paint another masterpiece. So it could become some kind of never-ending cycle, a trap of some kind.

The notion of a cyclical trap that keeps repeating harks back to “Murder Most Foul” replaying the Kennedy assassination on a loop: “Oh Lord, I’ve been led into some kind of trap.” Dylan’s phrasing also recalls Orpheus’s gnawing fear in Hadestown that the king of the underworld is leading him into a trap. Late in the play, Hermes hails his protégé: “Hey, the big artiste! / Ain’t you working on your masterpiece?” He is indeed working on his masterpiece, a song that will fix the broken world, put it back in tune. But Orpheus worries that Hades is turning this work against him, twisting the masterpiece into, in Dylan’s words, a never-ending cycle and trap.

Dylan includes a couple songs from Blonde on Blonde on Shadow Kingdom. “Most Likely You Go Your Way (And I’ll Go Mine)” and “Pledging My Time” are both works with Orpheus & Eurydice resonance in their lyrics, as I pointed out in the first installment of this series. I’m particularly interested in the visual treatment of these songs in Shadow Kingdom. Director Alma Har’el employs dim lighting and dark shadows for a chiaroscuro effect that invokes film noir.

But rather than populating her canvas with hardboiled detectives, double-crossing spouses, and gritty delinquents from the criminal underworld, the setting seems to be a nightclub in the mythic underworld, where shades intermingle, brooding in their own private hells, lost in varying degrees of oblivion and lifelessness. In “Most Likely,” some of the audience members seem to be mannequins, further emphasizing the atmosphere of lifelessness.

On other hand, the barflies are all abuzz in “Pledging My Time.” Belly-rubbing couples slow drag across the dancefloor, and a dude off in the corner freestyles solo to a rhythm it seems only he hears. In this performance, Dylan displays the Orphic power to enchant his listeners, inducing a trance over his underworld audience.

Sean Latham also picks up on the underworld implications of Shadow Kingdom in his compelling review, “Roadhouse on the River Styx.”

But the place we’ve found is not a crossroads, it’s a ferry crossing; and the River Styx, the boundary between this world and the next, flows insistently just outside the door. A superimposed title reminds us this is a film, that the entire thing is an act, and that we’ve entered this shadow kingdom to hear ‘the early songs of Bob Dylan.’ Over the next hour, the music will mingle life with death and hopefulness with mourning as we wait our turn for the relentless boatman.

Latham and I both interpret Shadow Kingdom as a descent into a honkytonk in hell. But he doesn’t share my view that this is Orpheus’s descent: “We are therefore not listening to Orpheus in this shadowy place, and so should not count on the music to carry us away, back to the world of the living. In Shadow Kingdom, Dylan tries to make the ghostly past talk by conducting a séance with his old songs to see if they might yet have something new to say.”

I like the séance analogy very much, but I think Latham is too quick to dismiss the Orpheus comparison. After all, Orpheus fails in his attempt to carry Eurydice back to the world of the living. The world of Shadow Kingdom isn’t all pie-in-the-sky hope, that’s for sure; but neither is it a yelp of resigned despair. The mood isn’t one of resolution but of suspension, not linear progression forward but circular repetition, albeit with interesting variations on each lap around the track. The early songs of Bob Dylan are old songs, often sad songs, but he’s going to sing them again. All these years later, our latter-day Orpheus still follows those ancient footprints, rapping at the door of his underworld Baby Blue, trying and failing yet trying again to sing a song to set things right.

The effort can feel futile and doomed. The singer appears to have gotten himself stuck down there and is now fronting hell’s house band. Drinks are on the house and the band plays all night, but no one is going anywhere. Closing time never comes when time stands still. As Laura Tenschert puts it in her article on time in Dylan’s recent work, “every song looks like Dylan is performing within a moment in time that’s on a constant loop, like a painting that’s come to life: not only do the hands on the clock on the wall never move, but the audience members are confined to repetitive movements” (179).

This strange performance of stuck time sounds so much like Macbeth’s final soliloquy that it’s hard to imagine Dylan didn’t have the speech consciously in mind when conceiving Shadow Kingdom:

Tomorrow, and tomorrow, and tomorrow,

Creeps in this petty pace from day to day,

To the last syllable of recorded time;

And all our yesterdays have lighted fools

The way to dusty death. Out, out, brief candle!

Life’s but a walking shadow; a poor player,

That struts and frets his hour upon the stage,

And then is heard no more. (5.5.19-26)

Denzel Washington as Macbeth in Joel Coen’s film The Tragedy of Macbeth (2021).

The creeping pace, recorded time, dusty death and walking shadow all feels right at home in Shadow Kingdom. But not the “heard no more” part, since the songs are always sung, on permanent repeat. And Dylan surely doesn’t share Macbeth’s closing nihilism: “it is a tale / Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury / Signifying nothing” (5.5.26-28). That may be the view from Dunsinane Castle, but not from Dylan’s Shadow Kingdom, and for that matter, not from Mitchell’s Hadestown. The darkness is never absolute and the negation is never complete. Each night the brief candle gets blown out, but then a new match is struck and we start anew.

The final song of Shadow Kingdom is “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue,” or simply “Baby Blue” as the film titles it. In the present context, this song sounds like the concluding chapter of the Orpheus and Eurydice myth, the planned exodus from the underworld. Grab your things, Eurydice, and let’s get the hell out of here: “Well, you must leave now, take what you need you think will last / But whatever you wish to keep you better grab it fast.” It’s time to leave the world of the dead and return to the land of the living: “Leave your stepping stones behind, something calls for you / Forget the dead you’ve left, they will not follow you.”

We’re headed out of the darkness and back toward the light: “Strike another match, go start anew / Yes and it’s all over now, Baby Blue.” They are poised for an escape, but the song remains suspended at the threshold. They want to cross over, but they haven’t completed the journey yet. The myth tells us that they never will, but that doesn’t invalidate the impulse to try anyway. It’s a myth about trying and failing and trying again. Dylan captures this sensation in Blonde on Blonde, Rough and Rowdy Ways, and Shadow Kingdom. Mitchell makes her likeminded effort to express it in Hadestown.

Her lyrical and visual imagery is beautifully compatible with Dylan’s in “Baby Blue,” and vice versa. Eurydice’s first song, “Any Way the Wind Blows,” expresses her lost and wandering search for a home. Trying to brave the elements and find her way through the darkness, she asks “Anybody got a match? / Gimme that” (22). At the end of the show in “Road to Hell Reprise,” after Orpheus looks back and sends her back to Hell, she repeats the gesture: “Anybody got a match?/ Gimme that” (246-47). There’s a potent intertextual link here with Dylan’s “Strike another match, go start anew / Yes and it’s all over now, Baby Blue.” Yes, it’s all over for now, until we take up the story and sing it again and again and again.

Laura Tenschert points out that the chronology of songs in Shadow Kingdom reinforces this circular structure:

If the individual performances in Shadow Kingdom represent moments frozen in time, then the two framing songs close like a circle around them (much like the last line of “Murder Most Foul” leads us back to the beginning). In combining these looped moments with the out-of-time feel of the visuals (the mimed performances, the unmoving clock on the wall, and the slow-moving camera), Shadow Kingdom creates a world that is both stuck in time and exists outside of time. (181)

Art has the potential to achieve immortality, as myth does, through replacing linear time with cyclical time: the eternal circle. [Laura tells me that “Eternal Circle” was a working title for her essay on time in Dylan.] In Dylan’s underworld songs, and in the myths that inspire them, movement forward doesn’t lead to the end, it leads back to the beginning. I’m reminded of T. S. Eliot’s articulation of this idea in “Little Gidding”:

We shall not cease from exploration

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time.

Through the unknown, remembered gate

When the last of earth left to discover

Is that which was the beginning.

Laura concludes her essay on time in Dylan’s recent work with reference to “Forever Young”: “during one of the most tender moments in Shadow Kingdom he’s standing in what looks like an otherworldly waiting room, dressed all in white and bathed in a diffused spotlight, singing directly to us through the camera: ‘May your song always be sung / May you stay forever young’” (188).

I would call it an “underworldly waiting room,” but otherwise we’re perfectly in sync. As the character Llewyn Davis puts it in the Coen Brothers’ film, “If it was never new, and it never gets old, then it’s a folk song.” Or as a young Dylan put it “Eternal Circle,” in what seems in retrospect like his first look back at the Orpheus and Eurydice myth:

As the tune finally folded

I laid down my guitar

Then looked for the girl

Who’d stayed for so long

But her shadow was missin’

For all of my searchin’

So I picked up my guitar

And began the next song

Epilogue

In director Rachel Chavkin’s interview with Richard Schechner for TDR, she describes Hadestown as “a cyclical tragedy, with the potential for a breakthrough each time” (92). Hermes stresses this same point in the final song of the show proper, “Road to Hell Reprise”:

It’s a sad tale; it’s a tragedy

It’s a sad song

But we sing it anyway

Cos here’s the thing

To know how it ends

And still begin

To sing it again

As if it might turn out this time

I learned that from a friend of mine (246)

In that respect, the tale may be tragic, but the song always holds out the prospect for something more hopeful and, at least in theory, potentially redemptive.

Doubling down on this theme of the eternal circle, the closing song isn’t the end. Hadestown closes with an epilogue, or an encore if you prefer the musical terminology. “We Raise Our Cups” takes place outside the world of Hadestown and inside the world of the theater. The microphones are turned off, signaling that the cast is no longer in character. They sing directly across the footlights, performer to audience. Watch and listen for yourself starting at 7:15.

They send the audience home with a toast, and that seems a good way to close this series on the underworld songs of Bob Dylan and Anaïs Mitchell, too.

Mitchell and Dylan descend from the tradition of Orpheus, not only as musicians, but also as troubadours who wander the earth to create and share songs based on sorrow, loss, regret, and longing. It’s not the happy-go-lucky entertainers that are singled out for praise in “We Raise Our Cups.” No, it’s the sublime melancholics, the beautiful losers who transform their suffering into song.

Persephone & Eurydice: Some birds sing when the sun shines bright

Our praise is not for them

Persephone: But the ones who sing in the dead of night

We raise our cups to them (253)

You’ll pick up on that echo of Leonard Cohen’s “Bird on a Wire,” but I’m sure you also think of that mournful warbler from Dylan’s “You’re a Big Girl Now”:

Bird on the horizon, sittin’ on a fence

He’s singin’ his song for me at his own expense

And I’m just like that bird, oh, oh

Singin’ just for you

I hope that you can hear

Hear me singin’ through these tears

The Hadestown company shifts metaphors and offers a second toast:

Company: Some flowers bloom

Persephone & Eurydice: Where the green grass grows

Company: Our praise is not for them

Persephone & Eurydice: But the ones who bloom in the bitter snow

Company: We raise our cups to them (253-54)

I imagine Mitchell raising her cup to the Bard of the North Country, Jack Frost, the laureate of winter storms and frozen rivers, the singer fated to trudge his slushy path through the cold, pursued by hellhounds within and without, heroically braving the dark night until the dawn of a new morning.

That’s the Orphic tradition Mitchell and Dylan both descend from and carry forward, and it’s the legacy honored in the closing toast:

Company: We raise our cups and drink them up

Persephone: We raise them high and drink them dry

Company: To Orpheus, and all of us

Persephone: Good night, brothers, good night (254)

I love Mitchell’s gloss on this epilogue in Working on a Song. She hears the song as a salute to failure, or rather the artistic triumphs that emerge from the ashes of repeated defeats.

We raise our cups to Orpheus not because he succeeds, but because he tries. We understand implicitly that there’s value in his trying and even in his failure. The act of writing, for me, has most often been a process of failing repeatedly. It’s the only way I know how to write! And in the moment of “failure,” at the desk, banging one’s “head against the wall,” it’s nearly impossible to see or feel the value in it. (255)

If Dylan is a New Orpheus, then so is Mitchell. She endures defeat after defeat and yet continues to make the descent into the underworld, hoping maybe this time she’ll return with a prize rescued from the depths. So far it keeps ending badly, so far it hasn’t saved the world, but next time, who knows, it just might succeed. Art depends upon such heroic gestures of faith, hope, sacrifice, and resilience.

I’m no artist, but I can partially relate as a head-banging, floor-pacing, paper-crumpling, pencil-snapping writer. The perennial effort to push through failures and keep trying to accomplish something worth sharing is a challenge faced by the likes of Dylan and Mitchell in writing their songs, and it’s a challenge faced by us critics in writing about those songs. It helps to lean on and learn from others committed to the same journey.

Throughout this series, I have followed in the footsteps of writers who walked this path ahead of me. I’ve been focusing on influences and resonances in Dylan and Mitchell’s underworld songs. But I’m conscious that my own writing is likewise an exercise in adaptation—inheriting ideas from others, reworking and reassembling them, adding my own original takes, and making something new from what came before. The palimpsest parchment gets passed down, the scribes add their latest scribbles, and then we send the scrolls down the line for the next round of annotations. For critics as for artists, it’s an old song, but we’re gonna sing it again. Thanks for taking the journey with me, dear readers, to hell and back.

Works Cited

“Bob Dylan finally accepts Nobel prize in literature at private ceremony in Stockholm.” The Guardian (2 April 2017), https://www.theguardian.com/music/2017/apr/02/bob-dylan-finally-accepts-nobel-prize-in-literature-at-private-ceremony-in-stockholm.

Brennan, Niall. “Open the Door Homer: Dylan, Yeats and the Blind Poet.” High Summer Street (16 May 2021). https://www.highsummerstreet.com/2021/05/open-door-homer-dylan-yeats-and-blind.html.

Brinkley, Douglas. “Bob Dylan Has a Lot on His Mind.” New York Times (12 June 2020). https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/12/arts/music/bob-dylan-rough-and-rowdy-ways.html?action=click&module=Top%20Stories&pgtype=Homepage.

D’Aulaire, Ingri and Edgar Parin. Book of Greek Myths. Bantam Doubleday Dell, 1962.

Dylan, Bob. Chronicles, Volume One. Simon & Schuster, 2004.

---. Official Song Lyrics. The Official Bob Dylan Website,

http://www.bobdylan.com/.

---. “Nobel Lecture in Literature.” The Nobel Prize (4 June 2017). https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/literature/2016/dylan/lecture/.

Eliot, T. S. “Little Gidding.” Four Quartets: An Accurate Online Text. http://www.davidgorman.com/4quartets/4-gidding.htm.

Fyffe, Larry. “Bob Dylan: Aeneas Visits Key West.” Untold Dylan (14 July 2020), https://thedylanreview.org/2021/07/25/bob-dylan-and-wallace-stevens-in-conversation/.

Graves, Robert. Greek Gods and Heroes. Dell, 1960.

Hadestown (Original Broadway Cast Recording). Sing It Again, 2019.

Homer. The Odyssey. Trans. Robert Fitzgerald. Doubleday, 1963.

---. Odyssey. Trans. Stanley Lombardo. Hackett, 2000.

Inside Llewyn Davis. Written and directed by Joel Coen and Ethan Coen. Sony Pictures, 2013.

Latham, Sean. “Roadhouse on the River Styx.” The TU Institute for Bob Dylan Studies (20 July 2021), https://dylan.utulsa.edu/roadhouse-on-the-river-styx/.

Marcus, Greil. Folk Music: A Bob Dylan Biography in Seven Songs. Yale University Press, 2022.

Mitchell, Anaïs. Hadestown. Righteous Babe, 2010.

---. Working on a Song: The Lyrics of Hadestown. Plume, 2020.

Muir, Andrew. Bob Dylan & William Shakespeare: The True Performing of It, updated edition. Red Planet Books, 2020.

Ovid. Metamorphoses. Trans. Stanley Lombardo. Hackett, 2010.

Salvucci, Jim. “Bob Dylan and Wallace Stevens in Conversation.” The Dylan Review 3.1 (2021), https://thedylanreview.org/2021/07/25/bob-dylan-and-wallace-stevens-in-conversation/.

Schechner, Ricard. “The Director’s Process: An Interview with Rachel Chavkin.” TDR: The Drama Review 65.1 (2021): 79-94.

Shadow Kingdom: The Early Songs of Bob Dylan. Directed by Alma Har’el. Veeps, 2021.

Shakespeare, William. Macbeth. Arden Shakespeare Second Series. Ed. Kenneth Muir. Bloomsbury, 1997.

---. A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Arden Shakespeare Second Series. Ed. Harold Brooks. Bloomsbury, 1979.

Tannenbaum, Rob. “John Mellencamp Just Might Punch You.” New York Times (6 June 2023), https://www.nytimes.com/2023/06/06/arts/music/john-mellencamp-orpheus-descending.html.

Tenschert, Laura. “Chapter 2: The Other Side of the Coin—The Myth and Mystery of Creation on Rough and Rowdy Ways.” Definitely Dylan (11 February 2022), https://www.definitelydylan.com/podcasts/2021/2/11/chapter-2-the-other-side-of-the-coin-the-myth-and-mystery-of-creation-on-rough-and-rowdy-ways.

---. “Episode 33: Mondo Scripto.” Definitely Dylan (21 October 2018), https://www.definitelydylan.com/listen/2018/10/21/episode-33-mondo-scripto.

---. “‘Today and Tomorrow and Yesterday Too’: Time in Bob Dylan’s Work of the 2020s.” The Politics and Power of Bob Dylan’s Live Performances: Play a Song for Me, edited by Erin C. Callahan and Court Carney. Routledge, 2024, pp. 173-90.

Thomas, Richard F. “‘And I Crossed the Rubicon’: Another Classical Dylan.’” The Dylan Review 2.1 (2020). https://thedylanreview.org/2020/06/12/and-i-crossed-the-rubicon-another-classical-dylan/.

---. Why Bob Dylan Matters. Dey Street, 2017.

Virgil. Aeneid. Trans. Stanley Lombardo. Hackett, 2005.

Yeats, William Butler. “The Tower.” Poetry Foundation, https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/57587/the-tower-56d23b4072cea.

This three part series is a triumph Graley, thank you so much! I'm honoured that my work on recent Dylan could act as a jumping off point!

I see, but even without that explanation you have been gloriously prolific and I am sure I am not the only reader, while being grateful for it, amazed by your stamina.

It's not that long until the thirtieth anniversary of TOOM's sessions. You could resurrect the Mississippi thoughts then for an expanded book on TOOM (Andy suggests, greedily.)