Tower of Song

Yeats & Dylan, Part 3

A few months after Rough and Rowdy Ways was released in 2020, Laura Tenschert posted one of the best assessments of the album on Definitely Dylan. In the first installment of a multi-chapter series, Laura viewed the album through the lens of kleos, “which literally translates to ‘that which is heard,’ and means your renown, your reputation, and in a broader sense, it refers to the fame, the enduring honor or everlasting glory that those epic figures were hoping to gain.” Laura argued that Dylan’s preoccupation with kleos in RARW was part of his ongoing reassessment of his legacy, a retrospective prompted by the Nobel Prize for Literature.

When Dylan was announced as the surprise recipient of the world’s most prestigious literary award in 2016, Sara Danius, permanent secretary of the Swedish Academy, compared his songs to the rhapsodies of Homer. Dylan himself identified closely with the ancient Greek bard in his Nobel Lecture, crediting The Odyssey as a formative influence, and concluding his recorded speech with a quotation from the beginning of Homer’s epic: “Sing in me, oh Muse, and through me tell the story.” Homer and Dylan call upon a higher power to inspire their songs and confer kleos upon the heroes they praise. Dylan catalogues a number of such heroes over the course of Rough and Rowdy Ways. However, as Laura recognizes, one hero is the main focal point of his meditation and his scrutiny: himself.

He is the hero of these songs. It just so happens that he also fulfils the role of Homer as well. In these songs, the singer is addressing not just his own identity, but also how he is perceived in the world. In other words, Dylan is engaging with his own image, talking about his reputation, perhaps even actively seeking to shape his legacy. And after decades in the public eye, it is powerful to hear Bob Dylan, as he is nearing his 80th birthday, contemplating how he will be remembered, and perhaps even insisting on defining himself.

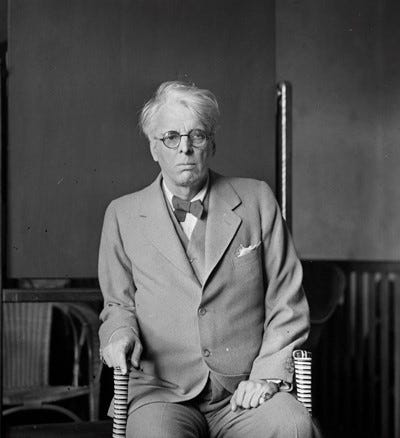

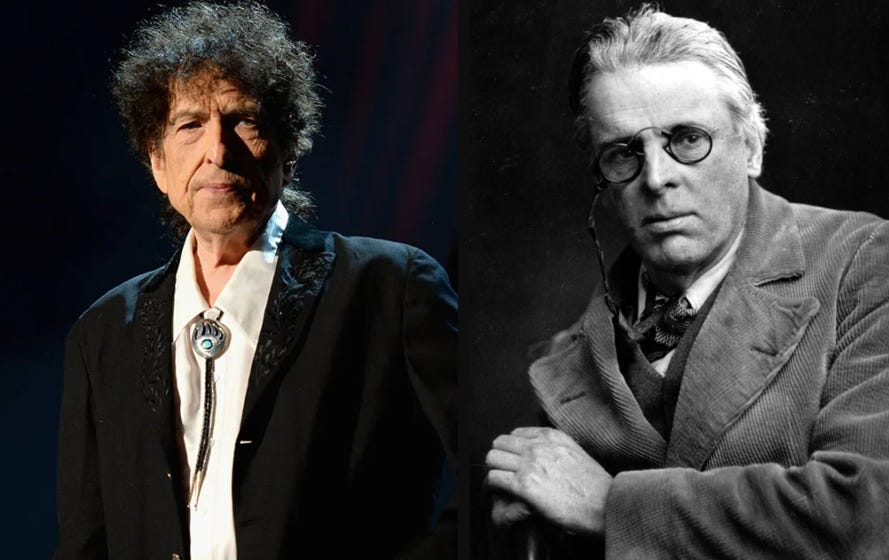

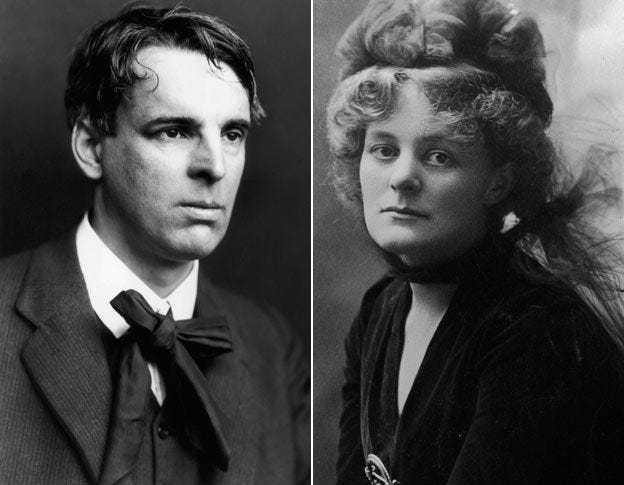

You win the Nobel Prize, you deliver the required lecture, you cash the check . . . then what? Most recipients have been past their prime when they received this career achievement award; indeed, in most cases, they were being honored for work composed many years earlier. But some Nobel laureates continued to create significant, relevant, innovative work even after their canonization. Bob Dylan is one. William Butler Yeats is another.

In 1923, Yeats became the first of four Irish writers to win the Nobel Prize for Literature in the 20th century [followed by George Bernard Shaw (1925), Samuel Beckett (1969), and Seamus Heaney (1995)]. Unlike the truant Dylan, Yeats traveled to Stockholm in person to deliver his lecture, “The Irish Dramatic Movement,” in which he contextualized his achievements alongside those of his friends and colleagues John Synge and Augusta Gregory. For an excellent study of Yeats winning the Nobel, read Ed Mulhall’s piece for RTÉ.

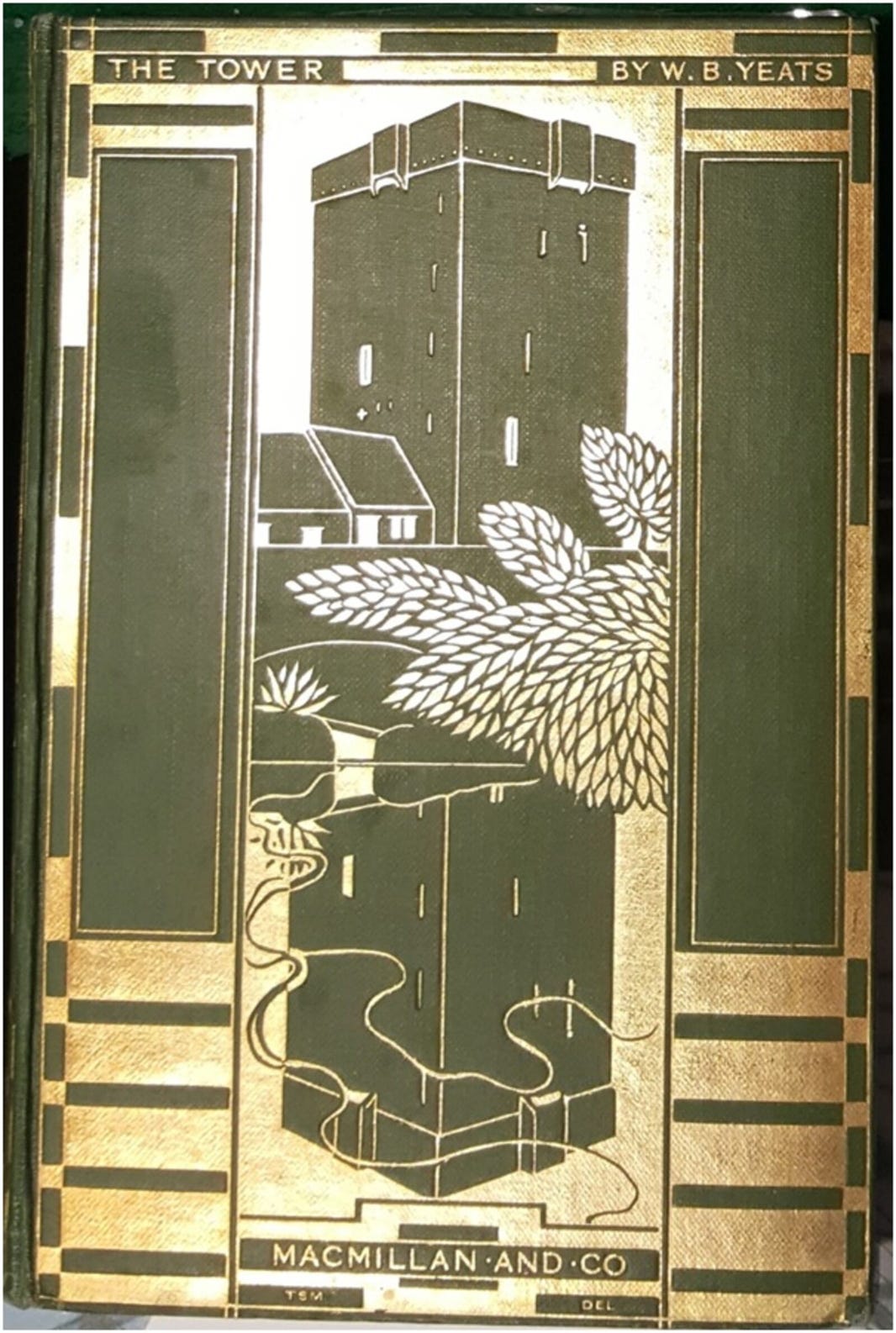

This was only the beginning of Yeats’s post-Nobel stock-taking. As with Dylan, it wasn’t until he processed his kleos through his primary medium of expression that he was able to adequately sound his depths and take his full measure. His first book of poems published after the Nobel was The Tower, arguably the single best volume of his career, and one of the crowning achievements in all of modern poetry.

There’s a lot to be learned from putting post-Nobel Yeats and Dylan into conversation. In this third and final installment of the series, I want to focus on selections from The Tower (1928) and Rough and Rowdy Ways (2020), comparing the two laureates’ ruminations on aging and endurance, history and memory, mortality and immortality, that which is left behind when one dies and that which lives on through art.

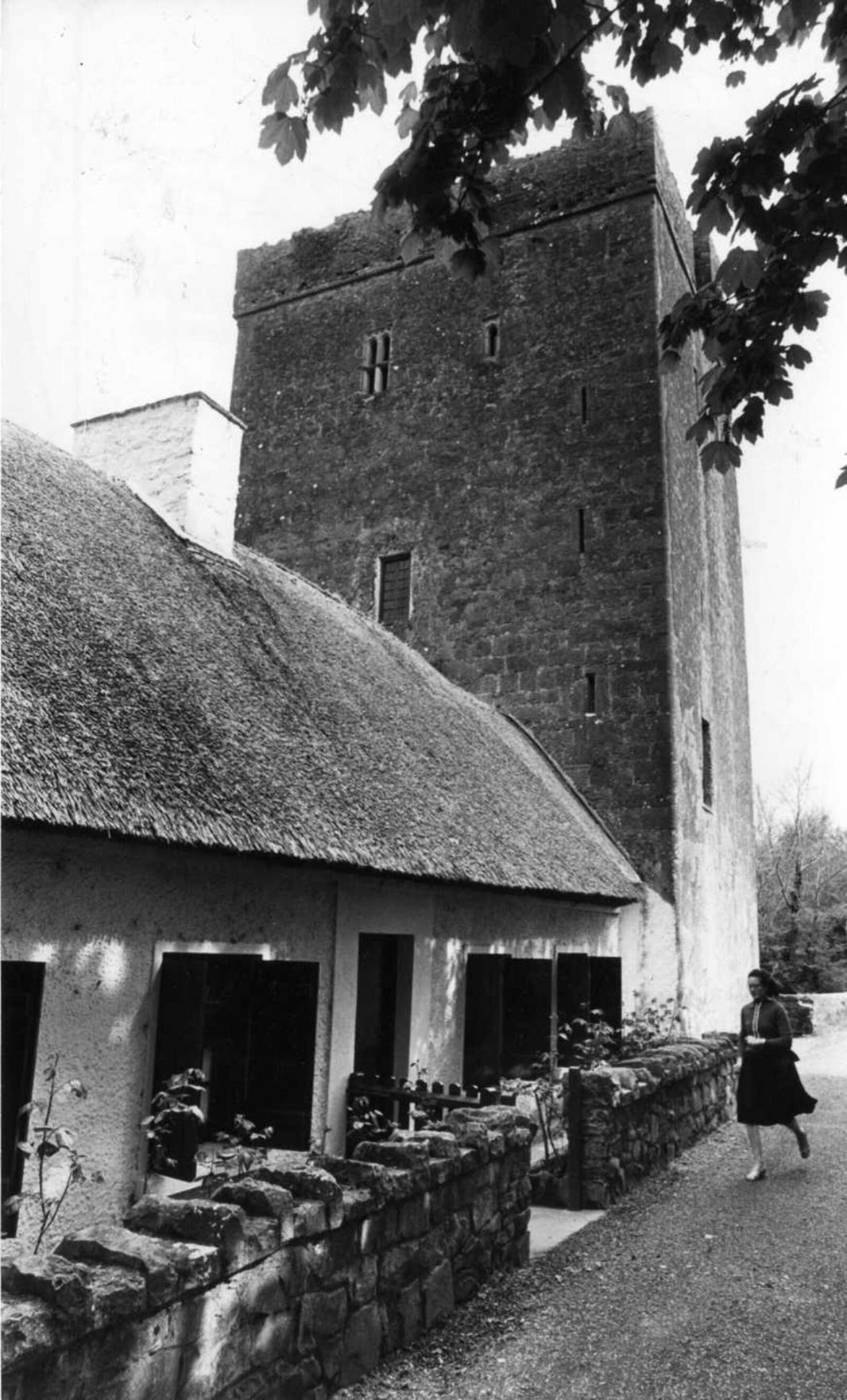

Thoor Ballylee

In “Desolation Row,” Dylan memorably depicts Ezra Pound and T. S. Eliot fighting in a tower. In The Tower, we find Yeats fighting in a tower with himself: his aging body versus his raging mind. As he wrote in Per Amica Silentia Lunae, “We make out of the quarrel with others rhetoric, but of the quarrel with ourselves, poetry” (492). In “All Along the Watchtower,” Dylan depicts the Joker and the Thief plotting their escape from a tower. In The Tower, Yeats is likewise holed up in a tower, escaping in his mind to the idealized past. Meanwhile, his feet remain firmly planted on Irish soil, or more precisely, on the ramparts of a stone fort turned summer home in County Galway.

Go to any European country with a history of military occupation (i.e., all of them) and you’ll find castles. The English domination of Ireland began in the 12th century. Anglo-Normans asserted control over the land and its people through a series of military campaigns, political alliances, strategic intermarriages, and cultural assimilation.

First came the conquests, then came the castles. Many of these fortifications can still be found scattered across Ireland in various degrees of ruin or renovation. Centuries after English rule was secured, smaller towers were constructed, especially in western Ireland. By design these tower houses continued to assert a sense of sovereignty, but, practically speaking, they served as domestic residences rather than military garrisons. One such tower was erected around the 15th century in the townland of Ballylee, near Lady Gregory’s Coole Park estate.

Yeats first visited Thoor Ballylee in the 1890s. “Thoor” is an alternate spelling of “túr,” the Irish for “tower.” Yeats was intrigued by the structure, but he was especially enchanted by the place’s connections to art and beauty. He devoted an entire chapter to Ballylee in the 1902 edition of The Celtic Twilight. There he focused chiefly on Mary Hynes, a legendary beauty who lived in the townland some sixty years earlier. Making the rounds with Gregory while collecting local folklore, Yeats was regaled with stories by old folks who still remembered Mary’s unparalleled beauty. He also heard tales of the renowned poet Anthony Raftery (Antoine Ó Raifteiri), a blind bard who wrote love songs for Mary that were still sung around the turf fires.

Yeats was so beguiled by Thoor Ballylee that he eventually purchased it in 1916. He captured its magical appeal in exalted Homeric terms in his 1923 Nobel Lecture:

I have in Galway a little old tower, and when I climb to the top of it I can see at no great distance a green field where stood once the thatched cottage of a famous country beauty, the mistress of a small local landed proprietor. I have spoken to old men and women who remembered her, though all are dead now, and they spoke of her as the old men upon the wall of Troy spoke of Helen […] It was a song written by the Gaelic poet Raftery that brought her such great fame and the cottagers still sing it, though there are not so many to sing it as when I was young: “O star of light and O sun in harvest, / O amber hair, O my share of the world, / It is Mary Hynes, the calm and easy woman, / Has beauty in her body and in her mind.”

I wonder if Dylan read Yeats’s Nobel Lecture while preparing to write his own. If so, he may have stored away this tale about the Muse Mary and the Bard Raftery for future use in Rough and Rowdy Ways. But more on that later. For now, the salient point is that Yeats located Thoor Ballylee at the crossroads where eros, thanatos, and kleos met—the perfect home for a poet.

After years of composing unrequited love songs for his own Muse, and after Maud Gonne repeatedly rejected his multiple wedding proposals, Yeats abruptly got married in 1917 at the age of 52 to a 25-year-old English woman named Georgie Hyde-Lees. The couple soon started a family, dividing their time between residences in London, Dublin, and Ballylee.

Thoor Ballylee was much more than a residence for Yeats. When he took possession of this imposing tower house, he reclaimed it for the purposes of art. As fellow Irish poet and Nobel laureate Seamus Heaney put it,

Here he was in the place of writing. It was one of his singing schools, one of the soul’s monuments of its own magnificence. His other addresses were necessary shelters but Ballylee was a sacramental site, an outward sign of an inner grace. The grace here was poetry and the lonely tower was the poet’s sign. Within it, he was within his own mind. (24)

Yeats turned Thoor Ballylee into his Citadel of the Imagination.

From Byzantium to Key West

The opening poem in The Tower is “Sailing to Byzantium.” Let’s start with the verb: sailing. Yeats begins the book by setting sail on an adventure, the classic opening for the hero’s journey. Readers of Shadow Chasing will know that this is also a favorite trope for Dylan, who has taken us on trips upon his magic swirling ship through countless songs. He intersperses this journey motif throughout Rough and Rowdy Ways. For instance, he sets sail at the beginning of “False Prophet” with these lines:

Another day without end – another ship going out

Another day of anger – bitterness and doubt

I know how it happened – I saw it begin

I opened my heart to the world and the world came in

Whether the voyage takes place on a ship as in “False Prophet,” on horseback as in “Crossing the Rubicon,” or in a Lincoln convertible as in “Murder Most Foul,” the songs enact life’s journey toward the undiscovered country of death. It’s also a journey inward, to “the deep heart’s core” as Yeats put it in his early poem “The Lake Isle of Innisfree,” or to “the foul rag and bone shop of the heart,” as he put it in the late poem “The Circus Animals’ Desertion.” Both Dylan and Yeats open their hearts and their boats to their audiences and take us along on their odysseys.

Yeats’s destination for this quest is Byzantium. In his book of esoteric philosophy, A Vision (1925), he described sixth-century Byzantium as the pinnacle of human achievement: “I think if I could be given a month in Antiquity and leave to spend it where I chose, I would spend it in Byzantium […] I think that in early Byzantium, and maybe never before or since in recorded history, religious, aesthetic and practical life were one” (190-91).

The ancient world seems much more hospitable than the modern world for the poet at the beginning of “Sailing to Byzantium”:

That is no country for old men. The young

In one another’s arms, birds in the trees,

— Those dying generations—at their song,

Fish, flesh, or fowl, commend all summer long

Whatever is begotten, born, and dies.

The world he describes has its perks—songs and sex all summer long—but only for those virile enough to enjoy it. Yeats was feeling his age in The Tower, as Dylan was on Time Out of Mind, where he reenacted a similar scene:

I see people in the park forgetting their troubles and woes

They’re drinking and dancing, wearing bright-colored clothes

All the young men with their young women looking so good

Well, I’d trade places with any of them

In a minute, if I could

Rather than envying the young lovers like Dylan, Yeats rejects their skewed values: “Caught in that sensual music all neglect / Monuments of unageing intellect.” He sets up an opposition between mortality and immortality, a tension that animates several poems in The Tower. The poet is surrounded by the folly of youth, which thrives for a season in the sun, then withers in the winter of discontent and dies. Yeats prefers to set his sights on the everlasting.

Put another way, “Sailing to Byzantium” pits the body against the spirit, another running theme in The Tower. In the second stanza, the poet declares,

An aged man is but a paltry thing,

A tattered coat upon a stick, unless

Soul clap its hands and sing, and louder sing

For every tatter in its mortal dress.

A paltry old man can become reanimated if he learns to make his spirit sing, like the dead body parts zapped to life by the immortal spirit in Dylan’s “My Own Version of You.” Song is the life force that recharges the soul. Yeats wants to leave his bothersome body behind and seek out a charging station for his spirit. He finds what he’s looking for in Byzantium:

Nor is there singing school but studying

Monuments of its own magnificence;

And therefore I have sailed the seas and come

To the holy city of Byzantium.

As a young man, Yeats fantasized about escaping the modern world in London for an idyllic sanctuary in Innisfree. Now, at the age of 61, he longs to flee modern Ireland specifically, and the mortal world more broadly, by seeking spiritual asylum in the ancient world.

In the third stanza, Yeats calls upon “sages standing in God’s holy fire” and asks them to become “the singing masters of my soul.” He believes that the body must be sacrificed, burning away all impurities, in order to achieve perfection of the soul. He vividly describes this incandescent process of transfiguration:

Consume my heart away; sick with desire

And fastened to a dying animal

It knows not what it is; and gather me

Into the artifice of eternity.

What does it look and sound like to leave the mortal world behind and join the choir immortal? Yeats concocts a strange image for this metamorphosis, probably modeled after automata kept in the palace of Byzantine emperor Theophilus. In the final stanza, the poet trades in his mortal body for the fabulous plumage of a golden bird:

Once out of nature I shall never take

My bodily form from any natural thing,

But such a form as Grecian goldsmiths make

Of hammered gold and gold enameling

To keep a drowsy Emperor awake;

Or set upon a golden bough to sing

To lords and ladies of Byzantium

Of what is past, or passing, or the come.

Yeats’s detractors love poking fun at this image. Oh, fancies himself a golden bird, does he? There he goes again, Juno’s peacock, fanning out his tail feathers to entertain the lords and ladies, turning Byzantium into a gilded Coole Park.

But let’s appreciate what Yeats is trying to do here. In choosing gold over flesh, he isn’t evoking wealth so much as lasting beauty, in the vein of Shakespeare’s Sonnet 55: “Not marble nor the gilded monuments / Of princes shall outlive this powerful rhyme.” Furthermore, of all the golden figures he might have chosen, it’s telling that he imagines himself as a bird, a creature famous for its song. Remember that the opening stanza referred to “birds in the trees,” but those birds were singing for mortals, “Those dying generations.” By contrast, the golden bird is an ageless paragon singing an immortal song—and that song is “Sailing to Byzantium,” a monument of its own magnificence destined to outlive its author.

“Sailing to Byzantium” is like the opening track for the album The Tower, the first in a series of songs meditating upon “what is past, or passing, or to come.” Dylan’s opening RARW song, “I Contain Multitudes” similarly evokes dying generations and echoes the closing lines of Yeats’s last stanza: “Today and tomorrow and yesterday too / The flowers are dying like all things do.” The songs in RARW go on to chronicle “what is past, or passing, or to come.”

The musical journey in RARW eventually leads to a place where the flowers remain in perpetual bloom: Key West, Dylan’s equivalent to Byzantium. Like Yeats, Dylan has a gift for taking real places and mythologizing them into metaphysical conditions (e.g., Mississippi, the Highlands). In RARW, Key West is the portal to Heaven. The song starts with a death: the assassination of President William McKinley, or, more precisely, Charlie Poole’s song about that death, “White House Blues.” Death is the gateway key that unlocks the door to the afterlife.

Dylan has situated songs at the threshold of death before, but he typically keeps the singer suspended, unable to cross over. Think of “Sad-Eyed Lady of the Lowlands,” waiting perpetually at the gate of the underworld. Think of “Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door” and “Tryin’ to Get to Heaven,” pleading for admission to paradise with no response. But in “Key West” it appears that permission to enter the City of Gold has finally been granted.

The singer counsels, “Key West is the place to be / If you’re lookin’ for immortality / Stay on the road – follow the highway sign.” This isn’t the Florida you’ll find at vacation resorts; this is the Florida that Juan Ponce de León was searching for in his quest for the mythical Fountain of Youth. The final verse sums up the emblematic significance of Dylan’s Key West:

Key West is the place to be

If you’re lookin’ for immortality

Key West is paradise divine

Key West is fine and fair

If you lost your mind you’ll find it there

Key West is on the horizon line

The vision I get is of the singer gazing at the setting sun, surveying this paradise from a vantage point on high, perhaps one of the island’s lighthouses or observation towers.

Standing on top of a tower, you can take in the entire horizon. This synoptic perspective gives the singer a bird’s-eye view across both space and time. In that respect and many others, Dylan occupies a position very much like Yeats atop Thoor Ballylee in his title poem “The Tower.”

Tower of Imagination

Yeats and Dylan both pay careful attention to the sequencing of their work. The order of poems in a Yeats volume is deliberate, as with the order of songs in a Dylan album or concert setlist, designed to suggest development or to set up interesting contrasts. As Hugh Kenner put it, Yeats “was an architect, not a decorator; he didn’t accumulate poems, he wrote books” (578). We can see a perfect example of Yeats’s poetic architecture at work in the first two poems of The Tower, where he stages dialectical interplay between “Sailing to Byzantium” and “The Tower.”

The opening lyric presents one solution to the problem of aging in the modern material world via escape into the timeless realm of art. “Sailing to Byzantium” is a poem of movement, a journey forward that paradoxically moves backwards in time. It is succeeded by “The Tower,” which is confined to a fixed location at Thoor Ballylee. The poet is preoccupied in both poems with “what is past, or passing, or the come.” But the image of perfect beauty and tranquility that closes “Sailing to Byzantium”—the golden bird—is unsettled by very different imagery in the opening section of “The Tower”—an old crow roosting in his nest. The temptation to escape into the past is offset by pressing matters in the present that hold him back and tether him to his tower. His imagination tries to soar in Part I of “The Tower,” but earthly worries, bodily indignities, and painful regrets keep clipping his wings.

“The Tower” begins with a question:

What shall I do with this absurdity—

O heart, O troubled heart—this caricature,

Decrepit age that has been tied to me

As to a dog’s tail?

In “Sailing to Byzantium,” he described his sick heart as fastened to a dying animal. Here he depicts old age in similar terms, like a foreign object tied to a dog’s tail. In both cases, he regards the thing that troubles him as separate and detachable, if only he could figure out how to cut the ties that bind the immortal spirit to the mortal body.

The poet also feels bound by public expectations. He insists that his artistic stamina is as vigorous as ever:

Never had I more

Excited, passionate, fantastical

Imagination, nor an ear and eye

That more expected the impossible.

Nevertheless, those tawdry, inhospitable, dying generations that he wanted to leave behind in “Sailing to Byzantium” demand that he act his age, concede his irrelevance, and quietly retire.

It seems I must bid the Muse go pack,

Choose Plato and Plotinus for a friend

Until imagination, ear and eye,

Can be content with argument and deal

In abstract things; or be derided by

A sort of battered kettle at the heel.

Yeats’s screed against aging and ageism reminds me of one of Dylan’s rants from The Philosophy of Modern Song. In his commentary on Charlie Poole’s “Old and Only in the Way,” he complains,

Actually, if you google the word senicide you’ll see that many parts of the world have a push/pull relationship with their older members—the push of veneration, the pull of elimination. The United States with its chrome-plated dreams of spit-shine modernity was never much for the admiration of its senior citizens. Way before taunts of “Okay, boomer” and the calling of people with experience the pejorative term “olds,” this country has had a tendency to isolate the grizzled dotard, if not on an ice floe then in retirement camps where they could gum pudding and play bingo away from the delicate eyes of youth. (266-67)

That is no country for old men. Better sail off to Byzantium quick before they lock you away in a retirement camp. Or a tower.

Under siege from without and within, the poet broods on the roof of his tower, awaiting the next assault on his dignity:

I pace upon the battlements and stare

On the foundations of a house, or where

Tree, like a sooty finger, starts from the earth;

And send imagination forth

Under the day’s declining beam, and call

Images and memories

From ruin or from ancient trees,

For I would ask a question of them all.

Yeats enlists ghosts and phantoms to defend his Citadel of the Imagination against attack from the philistine forces of modern Ireland and from the debilitating infirmities of advancing age.

Tower of Muses

Yeats summons up various figures from the past associated with Thoor Ballylee. The most compelling spirits are Mary Hynes and Blind Raftery. Translating his previous prose reflections into poetry, he recalls,

Some few remembered still when I was young

A peasant girl commended by a song,

Who’d lived somewhere upon that rocky place,

And praised the colour of her face,

And had the greater joy in praising her,

Remembering that, if walked she there,

Farmers jostled at the fair

So great a glory did the song confer.

Mary Hynes and Anthony Raftery were long deceased by the time Yeats came along, but the love songs lingered on, and he gave them a second life through “The Tower.”

Once a song is set loose in the world, you never know how far it will go, who will sing it or hear it, and what impact it will leave behind. As Yeats records, the potent mixture of Mary’s beauty combined with Raftery’s eloquence had an intoxicating effect on listeners:

And certain men, being maddened by those rhymes,

Or else by toasting her a score of times,

Rose from the table and declared it right

To test their fancy by their sight;

But they mistook the brightness of the moon

For the prosaic light of day—

Music had driven their wits astray—

And one was drowned in the great bog of Cloone.

Mary + Raftery + Moonlight + Music = Madness

Yeats compares this formula to Homer’s epic poetry about Helen of Troy, the face that launched a thousand ships:

Strange, but the man who made the song was blind;

Yet, now I have considered it, I find

That nothing strange; the tragedy began

With Homer that was a blind man,

And Helen has all living hearts betrayed

O may the moon and sunlight seem

One inextricable beam,

For if I triumph I must make men mad.

Irish troubadour Liam Clancy picked up a version of “Mary Hynes” during his travels:

It’s a safe bet that Dylan first encountered the story through Clancy. However, when he alludes to the Irish bard and his lass in the first verse of “I Contain Multitudes,” the reference sounds closer to Yeats’s “The Tower”: “Follow me close – I’m going to Bally-Na-Lee / I’ll lose my mind if you don’t come with me.”

Granted, there is a place in Ireland called Ballinalee in County Longford. But it seems much more likely that Dylan is thinking of Ballylee. Spellings and pronunciations in Irish can be quite fluid, especially when transcribing oral lyrics and translating from Irish to English. Dylanologists before me tracked down another Raftery poem about Mary called (in English) “The Lass from Bally-na-Lee,” which would seem to put the mystery to rest. The internal evidence of “I Contain Multitudes” suggests Thoor Ballylee as the source. Dylan follows Yeats following Raftery following Mary; meanwhile, poets and listeners alike are vulnerable to losing their minds in pursuit of the Muse.

The poet strikes a defiant pose in “The Tower,” but the victory of imagination is by no means assured. All these reveries about Muses and the songs they inspire inevitably lead Yeats back to Maud Gonne. Memories of Maud are the Achilles’ heel for Yeats. She was his Mary and his Helen [cf. “No Second Troy”], the woman who inspired him to artistic achievements like Raftery and Homer, but who also led his wits astray like the man who drowned in the bog.

At the end of Part II, when Yeats finally gets around to asking the question for which he has summoned his ghosts, it revolves around Maud: “Does the imagination dwell the most / Upon a woman won or woman lost?” The answer is so obvious that it hardly needs asking. The poet pacing the roof of Thoor Ballylee doesn’t dwell upon the woman won—his wife Georgie, nesting downstairs with the kids—but the woman lost—that wild bird Maud.

Sing in me, oh Muse? Sorry, but no—this bird has flown. Instead, like Dylan in RARW, Yeats is left with the Mother of Muses, Mnemosyne, the goddess of memory. When thoughts of Maud come howling like an idiot wind across the ramparts of Thoor Ballylee, it chills Yeats to the heart and engulfs him in the darkness of regret and self-recrimination:

If on the lost, admit you turned aside

From a great labyrinth out of pride,

Cowardice, some silly over-subtle thought

Or anything called conscience once;

And that if memory recur, the sun’s

Under eclipse and the day blotted out.

Mother of Muses, strike me blind.

We often romanticize artists who endlessly pursue creative inspiration. But by the time Yeats and Dylan produced their late work, they had learned the hard way how exhausting it could be to spend your whole life chasing after something you can never catch. The next song is always just out of reach; the next performance is always a little farther down the road.

Yes, there is something thrilling and life-affirming about Yeats and Dylan’s continuous artistic quest. As Dylan describes it in “I’ve Made Up My Mind to Give Myself to You”:

From the plains and the prairie – from the mountains to the sea

I hope the gods go easy with me

I knew you’d say yes – I’m saying it too

I’ve made up my mind to give myself to you

Whether “you” is the audience or the Muse, the demands on the devotee remain the same: total commitment. As the singer acknowledges in the same song, this odyssey can also be lethal:

I traveled the long road of despair

I met no other traveler there

A lot of people gone, a lot of people I knew

I’ve made up my mind to give myself to you

Here the emphasis is less on “you” and more on “give myself”: the complete sacrifice required for following one’s artistic vocation. Pursuing the Muse must sometimes feel like a pathological compulsion, or like being a cursed ghost doomed to roam the earth forever. Perpetual motion is actually a lot like being stuck: “I know it looks like I’m moving, but I’m standing still,” as Dylan laments in “Not Dark Yet.” This is the position Yeats finds himself in at the end of Part II of “The Tower,” stranded in his tower, eclipsed by dark emotions, stuck in the past, going nowhere.

Tower of Pride

Yeats rallies his flagging spirits by setting his sights on the future. As in “Sailing to Byzantium,” the way forward leads through the past. In the final section of “The Tower,” he mounts a vigorous defense against aging and death. “It is time I wrote my will,” he declares at the beginning of Part III, turning the rest of the poem into a form of self-elegy. He bequeaths his pride to “upstanding men,” which he identifies as members of the Anglo-Irish.

Time for a little history lesson. The Anglo-Irish are distinct from the Anglo-Normans. Both groups were instrumental in the subjugation of Ireland, but their methods were markedly different. The Anglo-Normans favored cultural assimilation, so thoroughly acclimating themselves to native customs that they allegedly became, in a famous phrase from Irish historiography, “more Irish than the Irish themselves.” Not so for the Anglo-Irish. They tended to carve out enclaves separate from the locals, isolate themselves in Big House estates, and maintain aloof detachment from the majority Catholic community. The Anglo-Irish enjoyed privileged status ever since the rabidly anti-Catholic Oliver Cromwell brought an army to Ireland in the mid-17th century, killed political enemies, seized land, redistributed it to his supporters, and installed a legal framework that advantaged Protestants and discriminated against Catholics.

Paradoxically, the Anglo-Irish also produced some of the leading lights of the Irish struggle for independence, seemingly working against the self-interests of their privileged class, and ultimately facilitating their own extinction. These Anglo-Irish nationalists included militant revolutionaries like Wolfe Tone and Robert Emmet, Home Rule champion Charles Stewart Parnell, as well as the leaders of the Celtic Revival and the Abbey Theatre, Yeats, Gregory, and Synge.

After the Irish War of Independence (1919-1921), during which many of the Big Houses were burned down in protest, the Anglo-Irish found themselves marginalized by the Irish Free State but alienated from the United Kingdom—too English for the Irish, and too Irish for the English. As the sun descended on this former ruling class, Yeats chose this occasion to celebrate its achievements:

The pride of people that were

Bound neither to Cause nor to State,

Neither to slaves that were spat on,

Nor to the tyrants that spat,

The people of Burke and Grattan

That gave, though free to refuse.

Edmund Burke was an Anglo-Irish philosopher in the 18th century who is widely regarded as a forefather of political conservatism. Henry Grattan was an Anglo-Irish politician who led the Irish Parliament at the end of the 18th century and opposed the Acts of Union which absorbed Ireland into the United Kingdom in 1800. Their statues face each other at the front gate of Trinity College Dublin, a longtime bastion of Protestant privilege in the middle of the Irish capital. The same poet who expressed his profound ambivalence about Easter Rising martyrs in “Easter, 1916” was now lionizing Anglo-Irish dignitaries after independence had been won. One cannot overstate what a politically controversial, tone-deaf position this was to hold in 1920s Ireland. And he didn’t confine his remarks to poetry.

In June 1925, Senator Yeats made a notorious speech on the floor of the Seanad Éireann (Irish Senate) during the debate over a bill to ban divorce. He condemned this measure as a sign of the Catholic Church’s overreaching interference in Irish domestic policy, boasting that “It is one of the glories of the Church in which I was born that we have put our Bishops in their places in discussions requiring legislation.” He was only getting warmed up. In the inflammatory conclusion of his speech, Yeats trumpeted Anglo-Irish leaders for making the modern independent state possible:

I think it is tragic that within three years of this country gaining its independence we should be discussing a measure which a minority of this nation considers to be grossly oppressive. I am proud to consider myself a typical man of that minority. We against whom you have done this thing are no petty people. We are one of the great stocks of Europe. We are the people of Burke; we are the people of Grattan; we are the people of Swift, the people of Emmet, the people of Parnell. We have created the most of the modern literature of this country. We have created the best of its political intelligence. Yet I do not altogether regret what has happened. I shall be able to find out, if not I, my children will be able to find out whether we have lost our stamina or not.

It is a speech of staggering hubris and class chauvinism—and it is quintessential late Yeats. At every turn, whenever his age or his caste dictated that he should mind his manners and bite his tongue, he did the opposite. It is also a culturally specific act of kleos, honoring Anglo-Irish Protestant heroes at the very moment when the Free State was largely dumping that legacy in the ashbin of history.

If Yeats sounds proud when talking about his cultural heritage, that rhetoric pales in comparison to his grandiose claims for the omnipotent powers of the imagination.

And I declare my faith:

I mock Plotinus’ thought

And cry in Plato’s teeth,

Death and life were not

Till man made up the whole,

Made lock, stock and barrel

Out of his bitter soul.

Yeats is espousing the philosophy of subjective idealism associated with Bishop Berkeley, another of his Anglo-Irish heroes. Berkeley’s central dictum was “being is being perceived” [esse est percipi]. For the Bishop of Cloyne, this philosophy reinforced his theology, believing that all existence resides within the mind of God, the perceiver of all. For Yeats, however, this creative function is performed by human perception, whereby “Man makes a superhuman / Mirror-resembling dream.” The mind constitutes its own cosmos, made in the perceiver’s own image. Death cannot defeat the poet, who wields imaginative power capable of converting the grave into the Garden of Eden:

Aye, sun and moon and star, all,

And further add to that

That, being dead, we rise,

Dream and so create

Translunar Paradise.

Percy Shelley famously proclaimed that poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the world. Yeats goes him one better, declaring that poets are the creators of life, death, and the afterlife.

Frankly, Yeats makes a better poet than a philosopher. He may think he can outwit death with such haughty gibberish, but as a reader I’m unmoved. He is far more persuasive at the end of the poem, when he stops trying to philosophize his way out of the problem of aging and instead levels with us about how it really feels.

Tower of Death

The conclusion of “The Tower” contains some of the most poignant lines Yeats ever wrote. Ostensibly, his point is to prove that death is illusory and the soul lives on forever. However, his descriptions of the degradations of old age are so powerful that the pathos overshadows his resolve.

Now shall I make my soul,

Compelling it to study

In a learned school

Till the wreck of body,

Slow decay of blood,

Testy delirium

Or dull decrepitude,

Or what worse evil come—

The death of friends, or death

Of every brilliant eye

That made a catch in the breath—

Seem but the clouds of the sky

When the horizon fades;

Or a bird’s sleepy cry

Among the deepening shades.

Yeats strikes a supremely confident tone at the beginning of this passage, preparing for a conclusion very much like “Sailing to Byzantium.” He directs his soul to study in a learned school, echoing the previous poem: “Nor is there singing school but studying / Monuments of its own magnificence.” The monument of Yeats’s own magnificence is “The Tower,” an imposing stone structure which Yeats transforms into an enduring artwork, with himself installed at the top, singing like a golden bird on his Byzantine bough.

But the bird’s voice begins to crack as he describes the maladies that beset his aching body. A Grecian goldsmith would never construct anything resembling this old scarecrow. Heavier shadows fall as he contemplates the loss of old companions. Thinking about the death of friends and lovers causes him to catch his breath. Damn, this is harder than he thought it was going to be. What was supposed to be a song of triumph sounds more like a dirge for the dead.

Attempting to gather himself, the poet insists that his imagination can overpower these pains, transmuting them into images of beauty, serenity, and consolation, making his hardships

Seem but the clouds of the sky

When the horizon fades;

Or a bird’s sleepy cry

Among the deepening shades.

Seem? These closing images are, to quote Hamlet, “but the trappings and the suits of woe” (1.2.86). The grief is irrepressible and resists being painted over with luminous clouds or drowned out by sweet birdsong.

The tension here between melancholy for the dying body and faith in the soul’s immortality reminds me of Dylan’s touching statement after the passing of Little Richard, the musical hero of his youth. “I just heard the news about Little Richard and I’m so grieved. He was my shining star and guiding light back when I was only a little boy. His was the original spirit that moved me to do everything I would do.” Dylan tries to reassure himself that art conquers death and the soul survives in the afterlife; but those bromides are hard to swallow after the Black Rider has just punched you in the gut: “Of course he’ll live forever. But it’s like a part of your life is gone.”

Yeats dramatizes the conflict between mortality and immortality in The Tower. This tension is epitomized by the tug-of-war between the book’s first two poems, the idyllic “Sailing to Byzantium” followed by the brooding “The Tower.” Dylan stages a similar tension between the last two songs on Rough and Rowdy Ways.

The singer follows the highway signs to paradise in “Key West.” RARW would be a very different album if it ended there. But Dylan includes one more song, the longest he ever recorded, taking us on a deadly detour to Dallas. The album concludes with an elegy, not just for the assassinated President John F. Kennedy, but for an American worldview that seemed to die with him.

Once again, Dylan turns a real place into a mythical realm and metaphysical condition. He establishes these two allegorical settings as opposite poles in the album’s cosmos, one compass point facing fair and the other facing foul. “Fair and foul are near of kin / And fair needs foul,” writes Yeats in “Crazy Jane Talks with the Bishop.” Dylan replicates this dualism in Rough and Rowdy Ways.

Key West is the place to find your mind, and Dealey Plaza is the place to lose it. Key West is “the land of light,” and the Big D is the epicenter of darkness. Key West is the place to be for “love and inspiration,” and Dealey Plaza is “the place where Faith, Hope and Charity died.” Key West represents everlasting life, and Dallas represents inescapable death. The singer forewarns us in the album opener: “I sleep with life and death in the same bed.” How does it feel? We can judge for ourselves in the album’s closing songs. “Key West” and “Murder Most Foul” represent Dylan’s Marriage of Heaven and Hell.

Tower of Song

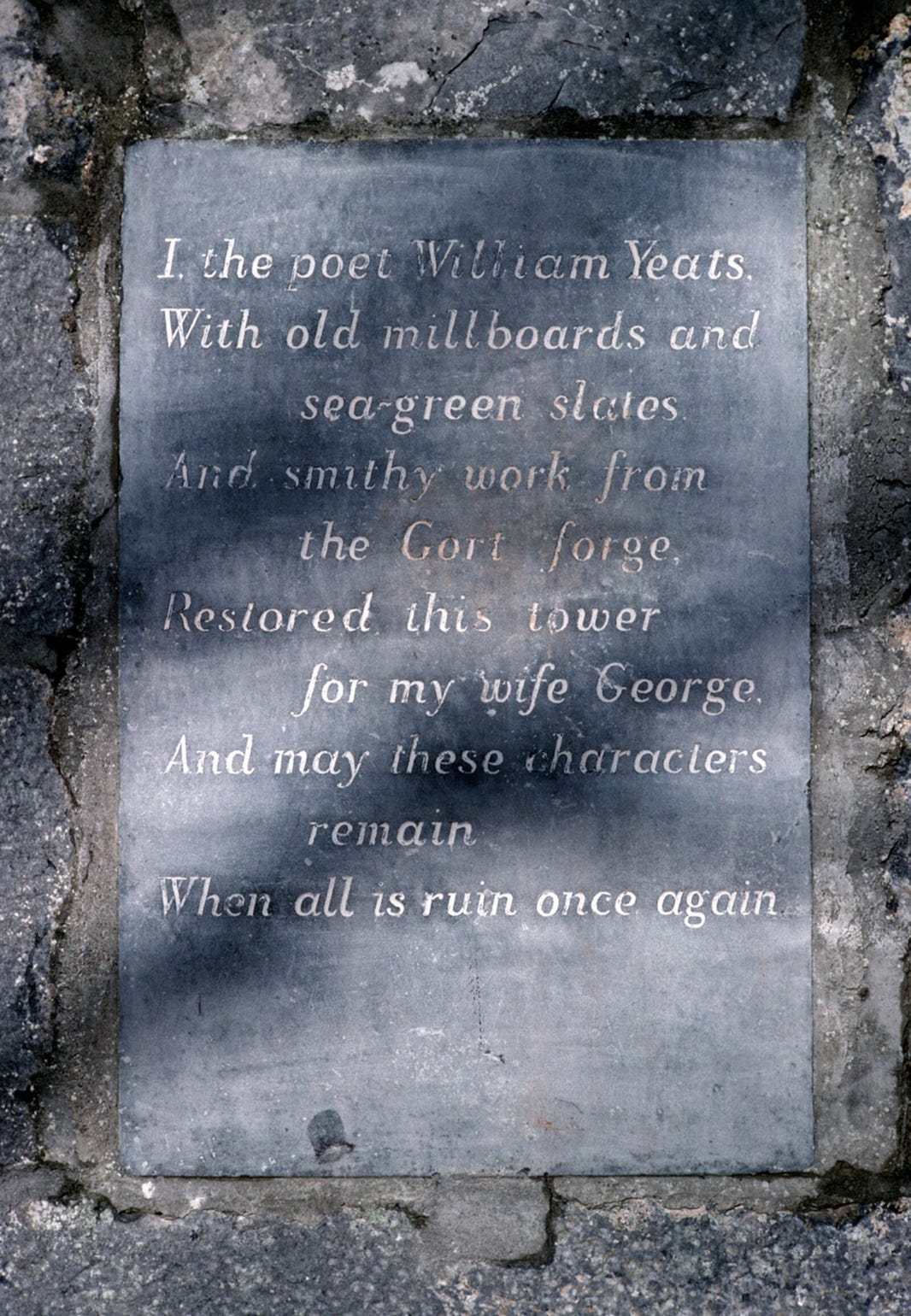

As the two Nobel laureates demonstrate in The Tower and Rough and Rowdy Ways, art can build a ballast against the ruins of time, even when that ballast is constructed from individual suffering and historical wreckage. Yeats inscribed this conviction on the outer wall of Thoor Ballylee, greeting the future visitors he trusted would make pilgrimages to this site.

I, the poet William Yeats,

With common sedge and broken slates

And smithy work from Gort forge

Restored this tower for my wife George.

And may these characters remain

When all is ruin once again.

As Dylan piles up musical and pop cultural references in the final section of “Murder Most Foul,” line after line, tier on top of tier, it feels like he is mortaring together stones for his own musical monument, his RARW Tower. I suspect that, a hundred years from now, listeners will still be visiting Dylan’s tower as they do Yeats’s The Tower and Thoor Ballylee. For now, no pilgrimages are necessary. Sit tight and sooner or later Dylan and his band will probably come to you, rebuilding his tower of song in your hometown.

He has also been including some gorgeous covers in the post-Nobel concert circuit, often by artists he loves who have passed on. The most moving tributes have been delivered in cities associated with the original artists. I’m thinking especially of Leonard Cohen’s “Dance Me to the End of Love” in Montreal, and Shane MacGowan’s “Rainy Night in Soho” in Dublin.

Listening to these moving memorials, it feels like Dylan has made his pilgrimage to place a stone on the graves of his immortal heroes. His covers effectively double as elegies and as Dylan’s Kleosophy of Modern Song. He fits these songs alongside his own, stone by stone, much as Yeats set his accomplishments beside those of his peers, heroes, and inspirations. You keep on working until your shift is done when you’re building the Never Ending Tower of Song.

I’ll leave the last word to Leonard Cohen, who made his own lasting contributions to the tower and now has a permanent home there:

My friends are gone and my hair is grey

I ache in the places where I used to play

And I’m crazy for love but I’m not coming on

I’m just paying my rent every day in the Tower of Song

Works Cited

Dylan, Bob. Nobel Prize Lecture. The Nobel Prize (5 June 2017), https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/literature/2016/dylan/lecture/.

---. Official Song Lyrics. The Official Bob Dylan Website.

https://www.bobdylan.com/.

---. The Philosophy of Modern Song. Simon & Schuster, 2022.

Foster, Roy. “Roy Foster on WB Yeats and Thoor Ballylee: ‘When all is ruin once again.’” Irish Times (21 March 2020), https://www.irishtimes.com/culture/books/roy-foster-on-wb-yeats-and-thoor-ballylee-when-all-is-ruin-once-again-1.4198959.

Heaney, Seamus. The Place of Writing. Scholars Press, 1989.

Kenner, Hugh. “The Sacred Book of the Arts.” The Sewanee Review 64.4 (1956): 574-90.

Mulhall, Ed. “Yeats as ‘Smiling Public Man’: the Nobel Poet and the new State.” RTÉ (October 2023), https://www.rte.ie/centuryireland/articles/yeats-as-smiling-public-man-the-nobel-poet-and-the-new-state.

Sean Éireann Debate (11 June 1925). Houses of the Oireachtas, https://www.oireachtas.ie/en/debates/debate/seanad/1925-06-11/12/.

Shakespeare, William. Hamlet. Second Quarto. Arden Shakespeare Third Series. Eds. Ann Thompson and Neil Taylor. Bloomsbury, 2006.

---. “Not marble nor the gilded monuments (Sonnet 55).” Poetry Foundation, https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/46455/sonnet-55-not-marble-nor-the-gilded-monuments.

Tenschert, Laura. “Chapter 1: ‘Sing in Me, Oh Muse’: Rough and Rowdy Ways, the Nobel Prize & the Shaping of Bob Dylan’s Legacy.” Definitely Dylan (11 October 2020), https://www.definitelydylan.com/podcasts/2020/10/11/chapter-1-sing-in-me-oh-muse-rough-and-rowdy-ways-the-nobel-prize-amp-the-shaping-of-bob-dylans-legacy.

Yeats, W. B. “Crazy Jane Talks to the Bishop.” The Collected Poems of W. B. Yeats. Ed. Richard J. Finneran. Simon & Schuster, 1983, 259-60.

---. “The Irish Dramatic Movement.” The Nobel Prize (15 December 1923), https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/literature/1923/yeats/lecture/.

---. Per Amica Silentia Lunae Per Amica Silentia Lunae. Essays. Macmillan, 1924, 479-538.

---. “Sailing to Byzantium.” The Collected Poems of W. B. Yeats. Ed. Richard J. Finneran. Simon & Schuster, 1983, 193-94.

---. “The Tower.” The Collected Poems of W. B. Yeats. Ed. Richard J. Finneran. Simon & Schuster, 1983, 194-200.

Dylan depicts Key West, not as Heaven in the Christian sense, but as the Underworld in ancient Greek mythology - "You stay to the left, and then you lean to the right/Feel the sun on your skin..."

Upon entering Hades, supposedly a real place for those who die, there lies dark Tartarus to the left where the those judged to be wicked are violently punished; to the right lies the Elysian Fields, a blissful and sunlit place for the virtuous.

Not sure that "Key West" is a vision of heaven or even a 'locus amoenus', for me as in all Dylan, there are too many contradictions pointing to intimations of danger and violence. Also it is not clear whether the voice in the song represents that of a stable consciousness, or rather someone who is trying to remember via broken memories and wistfulness what he can salvage from his life in Key West. Also the history of Key West, with its significance for Spain, Cuba, Jewish emigration, and illegal practices lies uneasily in the background to the 'stream of consciousness' treatment. And of course, there are the Presidents and links to the White House, at least two of them assassinated.