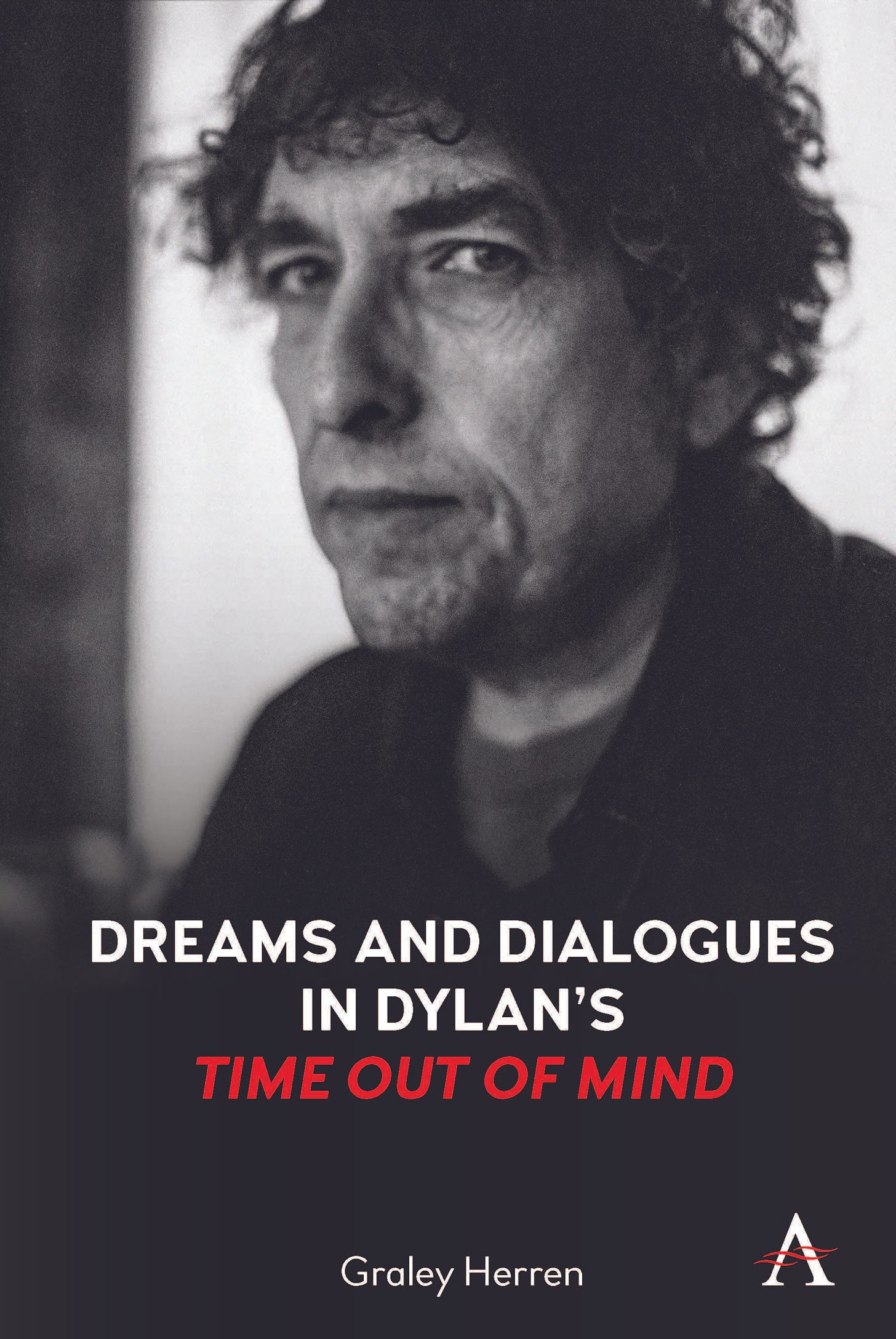

How did you spend your pandemic? I spent a lot of mine writing Dreams and Dialogues in Dylan’s Time Out of Mind.

I wrote it during lockdown in 2020, conditions that were wretched in most respects but which did give me time to immerse myself in the album and its outtakes from Tell Tale Signs, write daily, and do something productive during an otherwise desolate period. If I was seeking escape from bleakness, however, I picked the wrong album. As readers of Shadow Chasing know, Time Out of Mind is Dylan’s darkest record: lyrically, musically, psychologically, and metaphysically. During that first year of the pandemic, the album felt less like an exit door and more like a mirror or magnifying glass, reflecting and amplifying the misery of a world gone wrong. Back in 1996-1997, Dylan must have thought that writing, singing, playing, and recording such thoughts and feelings were better than brooding in impotent silence. The results are a staggering achievement, one of the highest peaks in the mountain range of his career.

Regrettably, travel came to a standstill in 2020, meaning that the recently opened Dylan archives was closed indefinitely. I suspected they had some hidden treasures relevant to my research, but I had no way to find out, so I finished the job with the tools at hand. I am elated now to have belated access to many of these crown jewels through Fragments: Time Out of Mind Sessions (1996-1997): The Bootleg Series, Vol. 17.

The deluxe box set consists of five discs: 1) a remix of the entire album; 2 & 3) outtakes and alternate takes; 4) select live versions from 1998 to 2001; and 5) a compilation of recordings from the Time Out of Mind sessions which had previously been released elsewhere. I love the Tell Tale Signs tracks on the fifth disc and wrote extensively about several in my book. The live cuts are interesting as well, but I’m going to set those aside for now. As a proud member of Team TOOM who passionately loves the album as is, I’m not the target audience for the 2022 remix. Personally, I’d be fine with Daniel Lanois doing the remix of “Love and Theft” as the lead disc for the next bootleg series. Kidding! Jack Frost has nothing to fear. Why would Columbia contract someone out to produce a new remix of a masterpiece? Why indeed….

But let us not talk falsely now. Fragments is truly cause for celebration, and I appreciate the opportunity to re-immerse myself in these songs, including several amazing versions I had never heard before. For the present piece I want to consider select outtakes from the second and third discs of Fragments and relate them to the second and third chapters of my book, those addressing religious allegory and race in America. Think of this post as an addendum to Dreams and Dialogues in Time Out of Mind, my chance to fill in some of the archival gaps in my book and examine earlier stages of the album’s gestational process.

In The Philosophy of Modern Song, Dylan includes a chapter on “If You Don’t Know Me by Now” by Harold Melvin & The Blue Notes. At first his commentary addresses the song on the surface level as a plea for understanding from a singer who has been completely misunderstood and mistreated by his lover. But then Dylan breaks out his critical steam shovel and dump trunk and excavates a buried layer of religious meaning: “Supposedly, early readers of the Bible were disturbed by the harshness of God’s behavior against Job, but the prologue with God’s wager with Satan about Job’s piety in the face of continued testing, added later, makes it one of the most exciting and inspirational books of the Old or New Testament.” “Context is everything,” he adds, concluding with deadpan understatement: “Here’s another way to look at a love song” (97). “If you don’t know me by now / You will never, never, never know me” as Job’s recrimination hurled at a capricious and cruel God? Yes! I read a number of Dylan songs as religious allegories, so it is both thrilling and validating to find Dylan using the same interpretive lens in his response to other artists. His invocation of Job’s contentious relationship with God strikes a chord with me since I apply the same analogy in my book to “’Til I Fell in Love with You”: “Just don’t know what I’m gonna do / I was alright ’til I fell in love with you.”

Fragments includes the earliest recording of “’Til I Fell in Love with You” at the Teatro on 3 October 1996. From its first incarnation, Dylan apparently conceived this song, at least on one level, as a conversation between man and God. The unfamiliar opening lines on this version are striking:

Well my head’s out of order

Ain’t takin’ any calls

You got any messages

Put ’em on the wall

At first blush, it’s a clever comparison of the singer’s frazzled mind with a busted telephone. For a biblical student like Dylan, however, the reference to messages on the wall may also echo Belshazzar’s feast in the book of Daniel. The phrase “the writing on the wall” stems from this account, where a disembodied hand appears during the banquet and inscribes a cryptic message on the wall. Daniel is brought in to decipher it and concludes that, because Belshazzar defied God, his days are numbered, he will soon die and face God’s stern judgment, and his kingdom will be divided—all of which comes to pass the very next day (Daniel 5:25-31). Dylan’s verse about the message on the wall was discarded post-Teatro, though it resurfaced years later in altered form in “Thunder on the Mountain”: “The writing’s on the wall, come read it, come see what it say.” A trace of the same scene from Daniel survives in “Mississippi”: “Your days are numbered, so are mine.”

I adore Dylan’s vocal performances on all the Teatro tracks. The “Can’t Wait” outtake on Tell Tale Signs has long been a favorite, and now I can add “Dreamin’ of You” to my personal desert island disc. On “’Til I Fell in Love with You—Version 1,” the malleability of his phrasing enhances the religious subtext. For instance, in a variant lyric he sings:

Well loneliness

Got a mind of its own

The more people around

The more you feel alone

Without a guide

Without a charge

Grief can cut you right to the heart

Least that’s what I think I hear him say. The way he pronounces “guide” sounds like he was leaning toward saying “Without a god.” That slippage may be accidental or deliberate, but either way it lends extra significance to a verse highly compatible with Job’s sense of spiritual abandonment. I also go back and forth as to whether Dylan says “Grief” or “Faith” as the thing that “can cut you right to the heart.” Those words look nothing alike written on the page (or the wall), but his phrasing resembles one of those pictures from the internet where one person sees black & blue and another swears it’s white & gold. Grief or Faith—mere semantic quibbling for Job, for whom the two have become indistinguishable, twin edges of the same blade.

The final Teatro verse of “’Til I Fell in Love with You” was abandoned at the Criteria sessions, but this recovered fragment confirms the religious roots of the song. My transcription may be imperfect, but this is what I hear:

Sometimes the words

Don’t do no good

Got to talk a different language

To be understood

Maybe you tuck by [talk about?]

And you feel alive

It’s a miracle

If you can just survive

By this point in the song, the religious level of meaning seems primary rather than secondary, overt rather than covert. The opening verse about miscommunication in the form of a broken telephone evolves by the final verse into unanswered prayer: Babel-like broken discourse between a mortal and a god no longer on speaking terms, who don’t even speak the same language. It would take a miracle to survive such a relationship, but the miracle maker is no longer taking requests.

No outtakes of “Not Dark Yet” were included on Tell Tale Signs, leading one to wonder if any worthwhile alternate versions were held back in the vaults. Asked and answered. “Not Dark Yet—Version 1,” recorded at Criteria on 11 January 1997, is one of the brilliant highlights of Fragments. We’ve become so accustomed to thinking of this as the darkest song on Dylan’s darkest album that it’s a jolt and a joy to hear it through new ears in this gently rollicking musical arrangement. The words are still bleak, but not the music. It’s definitely not dark yet in this version: the sun may be sinking, but it’s still got some shine left. Dylan chose the right version to include on the album. This lighter “Not Dark Yet” would have felt out of place alongside its somber siblings. But I’m sure Shadow Chasing readers are all glad that this version was preserved and released and can now occupy a secure spot on our regular rotation playlists.

In my chapter on religious allegory in Time Out of Mind, I discussed “Not Dark Yet” as a Jesus song in a section titled “The Crucifixion Blues.” Religious references are already on display in the original lyrics of Version 1. If I had archival access to this outtake back in 2020, you can bet I would have made a meal out of these lines:

I’ve gone too far down life’s beaten track

And I’m praying the Master will guide me back

The violets are fading and the trees are bare

Lord it’s not dark yet but it’s getting there

Notice how the guiding Master here jibes with the guide/God reference in “’Til I Fell in Love with You.” Dylanologists will immediately hear echoes of “Every Grain of Sand”: “In the fury of the moment I can see the Master’s hand.” The Master might still have been on Dylan’s mind from “Lone Pilgrim,” the exquisite closing track of his previous album World Gone Wrong: “The call of my Master compelled me from home.”

What stands out most to me in the original lyrics of “Not Dark Yet” is Dylan’s preoccupation with eyes: “Feel like my eyes are two pieces of broken glass”; “Feel like the hand of fate has jabbed its finger in my eye”; “Well I can close my eyes and I see her from such a long ways off.” Time Out of Mind is nothing if not persistent. Dylan paints his shadowy expressionist portrait from a limited palette that includes walking and dreaming, fire and disease. One of TOOM’s primary colors is blindness. I’m not telling you anything here you haven’t noticed yourself, right? Dark eyes stare out of this album, and they’re perpetually blind, closed, stuck, strained, unfamiliar or unreliable.

“Dirt Road Blues” [“until my eyes begin to bleed”]

“Million Miles” [“I don’t dare close my eyes and I don’t dare wink”]

“Tryin’ to Get to Heaven” [“I’ll close my eyes and I wonder / If everything is as hollow as it seems”]

“’Til I Fell in Love with You” [“my eyes feel like they’re falling off my face”]

“Not Dark Yet” [“I ain’t looking for nothing in anyone’s eyes”]

“Highlands” [“I got new eyes / Everything is far away”]

“Red River Shore” [I knew when I first laid eyes on her / I could never be free”]

“Mississippi” [“I’m gonna look at you ’til my eyes go blind”].

It’s like the singer saw those lovers in the meadow and silhouettes in the window on the opening track of “Love Sick,” and he’s not been able to see straight since, like his sight is diseased—like sight is the source of his disease.

Blindness has deeply religious connotations in Time Out of Mind. Publicizing the album release in September 1997, Dylan gave multiple interviews in which he reflected upon the importance of traditional music in shaping his personal philosophy and theology. He told Jon Pareles of the New York Times,

Those old songs are my lexicon and my prayer book. All my beliefs come out of those old songs, literally, anything from “Let Me Rest on That Peaceful Mountain” to “Keep on the Sunny Side.” You can find all my philosophy in those old songs. I believe in a God of time and space, but if people ask me about that, my impulse is to point them back toward those songs. I believe in Hank Williams singing “I Saw the Light.” I’ve seen the light, too.

This revealing passage is often quoted out of context, forgetting its specific relevance to Time Out of Mind, and overlooking the scriptural framework Dylan establishes for his prayer book of old songs. Earlier in the same interview, he recalled, “I get very meditative sometimes, and this one phrase was going through my head: ‘Work while the day lasts, because the night of death cometh when no man can work.’” He claimed not to remember where he got this mantra from. “But it wouldn't let me go. I was, like, what does that phrase mean? But it was at the forefront of my mind, for a long period of time, and I think a lot of that is instilled into this record” (Pareles).

The phrase comes from the gospel of John and relates to Jesus encountering a blind man and restoring his sight. Before performing the miracle, Jesus proclaims, “I must work the works of him that sent me, while it is day: the night cometh, when no man can work. As long as I am in the world, I am the light of the world” (John 9:4-5). Although Dylan obscures the footprints leading back to this passage in his interview, he knows precisely where it comes from because he uses it to set up the later references to enlightenment in old songs like “I Saw the Light”:

Just like a blind man I wandered along

Worries and fears I claimed for my own

Then like the blind man that God gave back his sight

Praise the Lord I saw the lightI saw the light, I saw the light

No more darkness, no more night

Now I’m so happy no sorrow in sight

Praise the Lord I saw the light

What’s so fascinating about “Not Dark Yet,” especially the earliest version included on Fragments, is that Dylan chronicles the opposite journey—from sight to blindness. “Lord, it’s not dark yet, but it’s getting there.” On one important level, “Not Dark Yet” is about going blind. It’s the opposite of a religious epiphany: it’s “I Saw the Dark.”

But we must also recognize that, in Dylan’s musical cosmos, blindness does not have exclusively negative connotations. After all, some of the greatest blues masters were blind. Dylan knows their work well, reveres it, and emulates it. As a young man he adopted the aspirational alias Blind Boy Grunt, as a mature man he praised Blind Willie McTell above all other blues singers, and shortly before embarking upon Time Out of Mind he covered songs by multiple blind musicians on his great cover albums. If we consider TOOM as the third installment of a trilogy beginning with Good as I Been to You and World Gone Wrong—and that’s a pretty useful way of thinking about it—then Dylan has moved a step beyond covers and is now attempting to channel these bards for inspiration in original compositions, as if he were an old blind blues singer himself. When he sings in “Not Dark Yet—Version 1” “I’m praying the Master will guide me back,” he may have Blind Wille McTell, Blind Blake, Blind Lemon Jefferson, Blind Willie Johnson, Blind Boy Fuller, Sonny Terry, and Rev. Gary Davis in mind just as much as God. Shut off from the sights of the external world, blind bards must sharpen their inner vision in order to recreate the world inside their minds.

“Here we go!” That’s what someone yells out as “Dirt Road Blues—Version 1” starts to roll out of the station on 12 January 1997. It’s a bumpy ride. I’m no musician, but even I can tell there’s a lot—probably too much—going on in the room at the same time. Interviews with those involved in the Miami sessions confirm this was often the approach at Criteria: gather a lot of talented players together, give them latitude to do their thing, and keep your ears open for when they find a groove, or just a salvageable riff. By all accounts, this process could be chaotic and frustrating, but judging from the final product I would certainly conclude that it worked magnificently. And if you disagree, well, now you have a remix to listen to instead.

It’s interesting when you can actually hear gestational development captured on tape in the outtakes. For instance, in “Dirt Road Blues—Version 2,” the band is much tighter and together: they have a clearer sense of where they’re going with the song now. But they’re still open to experiment and discovery. Go to 3:04 on the track and you’ll find the first appearance of a keyboard part that ends up becoming a major motif in the album version of the song:

Lyrically, Dylan is still finding his way, too. “Dirt Road Blues” is cut from the same cloth as the other songs, but it’s still in patches on these two outtakes. Some pieces are already firmly in place from the start, including references to religion [“I’ve been praying for salvation”] and blindness [“Gon’ walk down that dirt road / Until my eyes begin to bleed”]. Most striking of all, there is a slavery reference which makes this song a crucial chapter in the fugitive slave saga of Time Out of Mind: “’Til there’s nothing left to see / ’Til the chains have been shattered and I’ve been freed.” In other respects, however, Dylan is still wandering, not as the character in the songs but as the composer. Consider these abandoned lines from Version 2:

Well I’ve seen the lights of Broadway

And I’ve been on Sunset and Vine

I seen the lights of Broadway

And I stood around on Sunset and Vine

Well I ain’t been breakin’ your heart

You can stay away from mine

It’s an intriguing curiosity, but it doesn’t make a whole lot of sense. I thought he was on a dirt road, no? How does that square with walking the streets of New York and Hollywood? Or is the idea that he’s been to the big city, but now he has traveled to the rural South in pursuit of her? Or to escape her, since he tells her not to break his heart? You can see why this track got discarded: the jumbled lyrics just don’t quite work together.

Other lines from “Dirt Road Blues” didn’t make the final cut but nevertheless gesture toward important (if submerged) themes. Unlike the album rendition, Version 1 contains a bridge, and the lyrics accompanying the first bridge are quite remarkable:

Well right up ahead I see a patch of light

I’m wonderin’ why the flowers on the trees are so white

People all around me droppin’ like flies

I got the miseries of the world in my eyes

Hank Williams’s “I Saw the Light” refers to the saving grace of a religious epiphany, but that’s not the vibe I’m getting from Dylan here. Heading toward the light is also associated with approaching death, and that feels more relevant to “Dirt Road Blues.” Maybe the salient point is that one must choose—head toward the light or run away from it—before knowing if it represents life or death, salvation or damnation, the escape route to freedom or a one-way ticket to captivity in cold irons bound.

I don’t have space here to restate all my arguments for detecting a fugitive slave narrative in the songs recorded for Time Out of Mind; you’ll need to read the third chapter of my book and see if you’re convinced. But I will say that, viewed from this perspective, Dylan’s white flowers in the trees remind me of the sweet magnolias in Billie Holiday’s “Strange Fruit,” as well as the lynched Black bodies dangling from Southern trees. With people all around him dropping like flies or hanging like fruit, with the miseries of the world in his eyes, one can well imagine why this fugitive singer might prefer blindness to sight. He’s been hit too hard and seen too much.

I think “Standing in the Doorway” on Time Out of Mind is one of Dylan’s single greatest performances. The outtakes on Fragments provide further proof of his vocal dexterity. No matter how much the arrangements evolve from take to take, Dylan is consistently able to tap into the emotional core of the song. He slays me every time. Blues: wrapped around his head / Me: wrapped around his finger.

Lyrically, “Standing in the Doorway” is so much more than a lost-love song. Like the multiple levels of a dream, it moves in strange directions and morphs into unexpected shapes. The song invites a wide variety of interpretations, and I accept the invitation in my book, reading “Standing in the Doorway” on one level as a scaffold song in the murder ballads tradition, and on another religious level as a crucifixion song. I didn’t feature the song in my final chapter on race in America, but Fragments makes me wish I could go back and insert it.

In all the available versions of “Standing in the Doorway,” Dylan plays with time. He gives us a modern jukebox in the first verse, but other references in the song suggest a much older setting. This is not sloppy inconsistency: it is the tell-tale sign of a dreamscape where linear narrative does not apply, where past and present are inextricably intermingled. “Standing in the Doorway—Version 1,” recorded at Criteria on 13 January 1997, provides an enticing example. We still get that jukebox playing low in the first verse, but then this verse comes unexpectedly galloping through:

Maybe they’ll get me and maybe they won’t

But not tonight and it won’t be here

I know this horse I’m riding on could throw me but it don’t

The mercy of God must be near

Love that horse! In an album obsessed with walking, and occasionally with hopping buggies or trains, we can now add riding horses to the varied modes of locomotion. Very 19th century, wouldn’t you say? The horse conjures up images of outlaws from a bygone antebellum era, suggesting the singer is a 19th century fugitive. He traverses both space and time. As befits a dreamer or a blind man, the journey fundamentally takes place between his ears, across the blasted wasteland and populous graveyard of his mind.

The most provocative lyrical variant in “Standing in the Doorway—Version 1” marks the singer’s journey as a pursuit of freedom:

When the last rays of daylight go down

Buddy you’ll roll no more

I can hear them silent bells in my head

And I wonder who they’re ringing for

Don’t pass me by

Give me liberty

Or let me die

Readers of Shadow Chasing are probably familiar with Dylan’s epic burn of Lanois, when he explained to David Fricke of Rolling Stone why he left “Mississippi” off Time Out of Mind:

I tried to explain that the song had more to do with the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution and the Bill of Rights than witch doctors, and just couldn’t be thought of as some kind of ideological voodoo thing. But he had his own way of looking at things, and in the end I had to reject this because I thought too highly of the expressive meaning behind the lyrics to bury them in some steamy cauldron of drum theory. (Fricke 1318)

I don’t think Dylan is just randomly mentioning these foundational American documents to stress the forcefulness of his objections. I think the songs themselves show that Dylan had much more ambitious themes in mind than the obvious story about a man longing for his lost love. One cannot hear the lines above, “Give me liberty / Or let me die,” without thinking of Patrick Henry’s famous proclamation: “Give me liberty or give me death!” There is a running tension in the songs recorded for Time Out of Mind between liberty and incarceration, freedom and slavery. Dylan doesn’t beat us over the head with messages, but the theme is palpable throughout, lurking persistently below the surface and occasionally peeking out. On the surface, sure, I hear what you hear: a singer obsessively pining for the woman who did him wrong. But the songs work on other levels, too, hinting at a much larger commentary about the pursuit of freedom, justice, equality, and dignity—specifically the African American experience of pursuing an elusive, unfaithful, but alluring Lady Liberty.

Occasionally Dylan showcases what he’s up to with lines like “Don’t pass me by / Give me liberty / Or let me die,” temporarily exhuming his buried theme. In this context, I also wonder about another variant lyric from “Standing in the Doorway”: “Too many silver spoons / Too much salt in my wounds.” If you start to hear a faint echo of the driver’s lash and the pint of salt in “No More Auction Block” in this reference, then you’re tuning into the same frequency I hear in this song. I am also drawn powerfully to that image of “silent bells in my head.” Paired with the lines about liberty or death, I hear allusions to both the Liberty Bell and “Chimes of Freedom.” If the singer is indeed contemplating the racial sins of America, then he might well wonder who those all-too-silent bells are ringing for.

Of course, Dylan ultimately silenced the bell himself by leaving this evocative verse out of the song and off the album. Perhaps it revealed too much, rang too loudly. He generally prefers to keep his more ambitious meditations obscured and muted, what I’ve referred to in posts about The Philosophy of Modern Song as his “art of the unsaid.” When it comes to Time Out of Mind, he was so effective at vacuuming up his bread crumbs that some of his most important accomplishments went unnoticed or underappreciated for a quarter-century. It bears repeating something that I wrote in my book: Time Out of Mind has been too controversial for the wrong reasons, and not controversial enough for the right reasons. Fragments should help set the record straight, serving as an ultrasound of embryonic themes busy being born in the Teatro and Criteria studio sessions of 1996 and 1997.

[Special thanks to Laura Tenschert, Robert Chaney, and the Definitely Dylan gang on Patreon. Our discussions about the bootleg series helped spark a number of ideas developed in this post. I encourage my readers to check out Laura and Robert’s first impressions of Fragments in their Definitely Dylan podcast.]

Works Cited

Dylan, Bob. “Dirt Road Blues—Version 1.” Fragments: Time Out of Mind Sessions (1996-1997): The Bootleg Series, Vol. 17. Columbia, 2023.

---. “Dirt Road Blues—Version 2.” Fragments: Time Out of Mind Sessions (1996-1997): The Bootleg Series, Vol. 17. Columbia, 2023.

---. “Every Grain of Sand.” Shot of Love. Columbia, 1981.

---. “Highlands.” Time Out of Mind. Columbia, 1997.

---. “Lone Pilgrim.” World Gone Wrong. Columbia, 1993.

---. “Million Miles.” Time Out of Mind. Columbia, 1997.

---. “Mississippi.” “Love and Theft.” Columbia, 2001.

---. “Not Dark Yet—Version 1.” Fragments: Time Out of Mind Sessions (1996-1997): The Bootleg Series, Vol. 17. Columbia, 2023.

---. The Philosophy of Modern Song. Simon & Schuster, 2022.

---. “Red River Shore.” Tell Tale Signs: The Bootleg Series, Vol. 8. Columbia, 2008.

---. “Standing in the Doorway—Version 1.” Fragments: Time Out of Mind Sessions (1996-1997): The Bootleg Series, Vol. 17. Columbia, 2023.

---. “’Til I Fell in Love with You—Version 1.” Fragments: Time Out of Mind Sessions (1996-1997): The Bootleg Series, Vol. 17. Columbia, 2023.

---. “’Til I Fell in Love with You—Version 2.” Fragments: Time Out of Mind Sessions (1996-1997): The Bootleg Series, Vol. 17. Columbia, 2023.

---. “Tryin’ to Get to Heaven.” Time Out of Mind. Columbia, 1997.

Fricke, David. “The Making of Dylan’s ‘Love and Theft.’” Rolling Stone, 27 September 2001. Every Mind Polluting Word: Assorted Bob Dylan Utterances, edited by Artur Jarosinski. Don’t Ya Tell Henry, 2006, pp. 1318-19.

Herren, Graley. Dreams and Dialogues in Dylan’s Time Out of Mind. Anthem, 2021.

Pareles, Jon. “A Wiser Voice Blowin’ in the Autumn Wind.” New York Times (28 September 1997), https://www.nytimes.com/1997/09/28/arts/pop-jazz-a-wiser-voice-blowin-in-the-autumn-wind.html.

Tenschert, Laura, and Robert Chaney. “A Closer Look at ‘Fragments—Time Out of Mind Sessions.’” Definitely Dylan (28 January 2023), https://www.definitelydylan.com/listen/2023/1/28/a-closer-look-at-fragments-time-out-of-mind-sessions.

Williams, Hank. “I Saw the Light.” MGM, 1948.

I would genuinely love to hear a Lanois re~mix of Love and Theft! The steamy cauldron mixes. It would only be fair. I really feel for him.

I think this is spot on....“If we consider TOOM as the third installment of a trilogy beginning with Good as I Been to You and World Gone Wrong—and that’s a pretty useful way of thinking about it—then Dylan has moved a step beyond covers and is now attempting to channel these bards for inspiration in original compositions, as if he were an old blind blues singer himself.”

Thanks Graley. Really enjoying your posts here.

Hey Graley, I finally had time to read this post carefully and digest. Great stuff, as always. I would love to read your book and now I see that it's nearly affordable at $30 on Amazon, so I will order it soon.

I have long heard the religious subtext on Time Out of Mind that you discuss here — the addressee of the song being on the surface a woman, but more convincingly, God. Of course it is transparent in "Tryin' to Get to Heaven":

You broke a heart that loved you

Now you can seal up the book and not write anymore

I’ve been walking that lonesome valley

Trying to get to heaven before they close the door

One thinks of Hank Williams, the "valley of the shadow of death" and the book of judgment all in this quatrain. As you point out, the "lexicon and prayerbook" in its proper context.

My forthcoming book has a chapter on the theme of spiritual loss or abandonment on "Tempest," and the idea is also crucial to my main subject, "Rough and Rowdy Ways." On the latter record, however, despair is overcome, while reconciliation, contentment, and fiery statements of belief come back to the fore. Here's one example, directly related to all your observations about the "eyes" on TOOM, and the blues masters that Dylan has long admired:

Radio signal clear as can be

I’m so deep in love I can hardly see

Down in the flatlands - way down in Key West

The "blindness" in this lyric from "Key West (Philosopher Pirate)" is no handicap. It is a requirement of faith (and so necessary in grief). Because you can't see "the Master" with your eyes. You can see all the beauty of Nature and Creation, but viewing the Source requires another kind of sense. One that Dylan describes as more like hearing: a "radio signal clear as can be." And of course he describes it that way. His prayerbook is song. In my chapters I discuss where I believe Dylan found the specific inspiration for these lines.

I look forward to reading Dreams and Dialogues because I think my book, titled I Don't Love Nobody: Bob Dylan at the End of Time, might share a few themes. Much of my analysis concerns how that "end of time," just begun in "Can't Wait," is now well along, and how we can hear it all through "Rough and Rowdy Ways." How those shadows that were falling in "Not Dark Yet" now surround the singer in "Key West," where he is "walking in the shadows after dark." How the singer appears resolute in his faith and his acceptance of mortality. He approaches the end with "A Satisfied Mind." Of course, that "end of time" has more universal connotations too.

I hope, as a writer fascinated by the hidden things in Dylan, "the art of the unsaid," as you put it, that you will be interested in my argument about the obscure origin of many of the lyrics in "Key West (Philosopher Pirate)." My discussion of the song's source material carries forward many of the ideas you have found in TOOM, and reveals, in specific detail, how the singer indeed still has the Lone Pilgrim (originally the "white pilgrim") very much on his mind.

I always look forward to your articles, Graley. Thanks for your work!