When I heard about Burt Bacharach’s recent death, I thought immediately of Dylan’s wisecrack about Elvis Costello in The Philosophy of Modern Song: “When you are writing songs with Burt Bacharach, you obviously don’t give a fuck what people think” (10). Ouch! Whether you agree with the sentiment or not, it seems like an awfully mean-spirited thing to publish.

Or am I reading it wrong? Could Dylan have actually intended this statement as a sort of compliment, applauding Costello for his wide-ranging musical interests and his willingness to follow inspiration wherever it leads, even at the risk of alienating fans and critics, facing ridicule for his unpopular tastes or outdated views?

If we needed any reassurance on the matter, after reading The Philosophy of Modern Song we can all agree that Dylan doesn’t give a fuck what people think either.

The observation about Bacharach was only the first of countless examples where Dylan made me cringe the first time through the book, thinking “Come on, Bob! How could you write such rubbish?” While re-reading the book, however, I often paused over such comments and second-guessed my first impressions, wondering “Am I being too literal-minded and thin-skinned? Too humorless and square?” Then I would start third-guessing: “Am I trying too hard to justify and apologize, rationalizing a benign interpretation for truly malicious remarks?”

If you’re like me, the most problematic sections of The Philosophy of Modern Song are Dylan’s provocative, cantankerous, inflammatory, or tone-deaf passages about women. You know the ones I’m talking about. I bet you’ve either quoted them or had them quoted at you. Like this one: “The lips of her cunt are a steel trap, and she covers you with cow shit—a real killer-diller and you regard her with suspicion and fear, rightly so” (253). Say what?! Yes, yes, I know: taking such lines out of context distorts their meaning; Dylan is channeling the voice of a character in a song, not expressing his own views; he’s having a laugh at the expense of his legion of uptight critics who wouldn’t know a joke if it bit them in the steel trap; lighten up, it’s only rock ’n’ roll and he’s just an excitable boy. Okay. But then I try to imagine someone handing me the same passage and telling me it was an excerpt from the next book by [insert your choice of sexist Dylan critic here]. Would I have laughed it off and pleaded context and creative liberty, or would I have started polishing my marching shoes and sharpening my pitchfork?

I’ve written several pieces on PoMS, but I’ve side-stepped the elephant in the room. The time has come to confront some of the weird and unsettling gender issues raised by the book. This is a thorny problem, but any full and fair assessment demands grappling with this major theme. Some early reviewers, like Jody Rosen of the Los Angeles Times and John Carvill for Pop Matters, accuse Dylan of blatant misogyny. Among the fans I know, most don’t regard Dylan as a misogynist, in or out of this book; but some do, or more to the point, some didn’t until now. I respect both positions. I’m certainly not going to “mansplain” why you should or shouldn’t be offended by Dylan’s views on women in PoMS. Poor scrivener that I am, I prefer not to approach this subject like a debate or sporting event, with right and wrong answers, winners and losers. What follows will read less like a thesis-driven academic argument and more like intertextual pinball. If I have anything worthwhile to contribute—and I hope I do—it will come from placing Dylan’s work in conversation with other texts, contexts, and perspectives that might shed light on the complex gender dynamics of The Philosophy of Modern Song.

“Pump It Up” by Elvis Costello

After establishing the Odyssean theme of the hero’s journey home in the first chapter on “Detroit City,” Dylan introduces another recurring theme for his hero—trouble with women—in the second chapter on “Pump It Up”: “You’re the alienated hero who’s been taken for a ride by a quick-witted little hellcat, the hot-blooded sex starved wench that you depended on so much, who failed you. You thought she was heaven and life everlasting, but she was just strong willed and determined—turned you into a synthetic and unscrupulous person. Now you’ve come to the place where you’re going to blow things up, puncture it, shoot it down” (7). We’ve heard this tune before. Yet another man characterizing yet another woman as cruel temptress, blaming her sexuality for driving him crazy and making him do bad things. Dylan has plenty of kindling from “Pump It Up” to fuel temptation’s angry flame:

Though you try to stop it

She’s like a neurotic

You wanna torture her

You wanna talk to her

All the things you bought for her

Putting up your temperature

Costello deflects these violent fantasies through the second-person voice (“you”), which is also Dylan’s preferred voice throughout PoMS. Nevertheless, the bloodlust of the singer is unmistakable. I know: it’s art, not a diary entry or sworn deposition. Costello is singing in character, and Dylan is writing in character, inhabiting a fictional persona. However, as in a lot of Dylan’s performances of murder ballads, it can be disturbing how much he relishes the part and plays it so convincingly: “And what about that little she goat that won’t go away? You want to maim and mangle her. You want to see her in agony” (8). I have written elsewhere about the songs for Time Out of Mind as murder ballads, but none of those lyrics are as graphic and sadistic as Dylan’s riff on “Pump It Up.” Granted, he belatedly puts some distance between himself and the song: “The song is brainwashed, and comes to you with a lowdown dirty look, exaggerates and amplifies itself until you can flesh it out, and it suits your mood. This song has a lot of defects, but it knows how to conceal them all” (8). But by this point many readers will find Dylan’s disclaimer at the end to be less persuasive than his simulation of misogynistic violence in the rest of the riff.

When it comes to charges of straightforward misogyny in Costello or in Dylan, however, it’s not the “misogyny” part of the indictment I resist as much as the “straightforward.” It’s more complicated and crooked than that in both cases. For instance, consider “Pump It Up” within its original context on This Year’s Model. In his June 1978 album review for Crawdaddy, Jon Pareles observed, “No doubt about it—This Year’s Model rocks tough and committed. It is also so wrongheaded, so full of hatred, and so convinced of its moral superiority that it makes me uneasy. Costello’s intelligence is evident in every lyric; it’s easy to identify, for a little while, with his pained vindictiveness.” As Pareles noted, that hatred and vindictiveness was not distributed equally: “Costello distrusts his entire universe, particularly its female side, and I get the feeling negativity won’t pull him through.” [Notice Dylan already lurking in the shadows with Pareles’s nod at the end toward “Just Like Tom Thumb’s Blues.”]

In his article “‘A Complete Loser’: Masculinity and Its Discontents in Elvis Costello’s My Aim Is True and This Year’s Model,” John McCombe uses a different lens for looking at Costello’s gender dynamics. “Elvis Costello” is a deliberately constructed myth of the complete loser, the Über-Wimp, a persona invented by Declan Patrick MacManus as an alternative to 1970s clichés of masculinity. In his revealing March 1986 interview with Bill Flanagan for Musician, Costello registers his disdain for “cock rock” machismo on the one hand, and doe-eyed, tender-hearted crooners on the other:

Two types of rock ’n’ roll had become bankrupt to me. One was ‘Look at me, I’ve got a big hairy chest and a big willy!’ and the other was the ‘Fuck me, I’m so sensitive’ Jackson Browne school of seduction. They’re both offensive and mawkish and neither has any real pride or confidence. Those songs on the first couple of records helped mold my persona, but to me there was a lot of humor in it. I was laughing at the alternatives. It was wanting to have another set of clichés because the old clichés were all worn out.

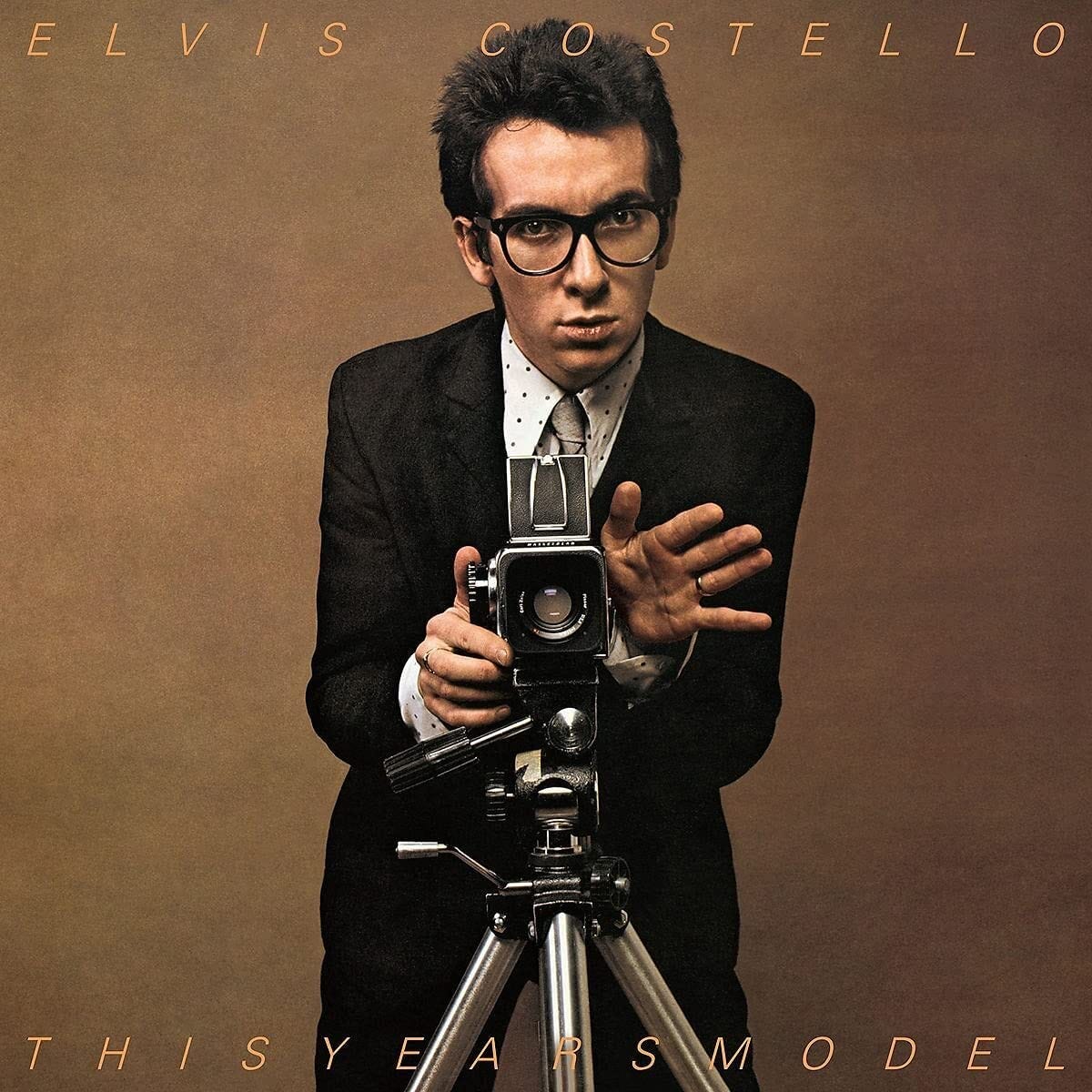

McCombe argues that Costello wasn’t simply hurling derision and abuse at beautiful models as commodified objects of desire in This Year’s Model. After achieving some fame from his first album, Costello began to identify as a reluctant celebrity himself. According to McCombe, “Costello is the woman objectified—he is ‘this year’s girl.’ Of course, ‘This Year’s Girl’ would be an awkward title for a record that bears Costello’s own image on the cover, so ‘girl’ becomes ‘model,’ but the album artwork nevertheless confirms the connection between the singer and the model before the camera” (202).

Costello stands behind the camera like some cut-rate Svengali, a cheap pornographer trying to manipulate the object of his male gaze into a pose that will sell magazines. Meanwhile, Chris Gabrin equipped Costello with the same tripod and camera he was using for the cover shoot, mirroring the subject position of the photographer. Simultaneously, Costello himself is on display as object of both the photographer’s and the consumer’s gaze, posing for a money shot calculated for maximum album sales.

In his chapter on “Pump It Up,” Dylan likewise plays with subject/object relations, masculine anxieties, and the gendered gaze. However, his reference points reach back much further to ancient mythology. “You never look back you look forward, you’ve had a classical education, and some on the job training. You’ve learned to look into every loathsome nauseating face and expect nothing” (7). I suspect that Dylan is subtly drawing upon his own autodidactic classical education, putting “Pump It Up” in conversation with the most famous myth about looking into a “loathsome nauseating face”—the head of Medusa.

Dylan isn’t showing off his intelligence—quite the opposite—he obscures his allusions so thoroughly that they’re barely detectable. And he’s not just randomly invoking arbitrarily chosen mythological figures. Costello’s “Pump It Up” fits surprisingly well alongside Medusa.

Remember that Medusa was one of the three Gorgon sisters. After she had sex with (i.e., was raped by) Poseidon in Athena’s temple, Athena punished her by transforming her beauty into monstrosity, giving her snakes for hair and ensuring that any man who met her gaze would be instantly turned to stone. Perseus ultimately defeated Medusa with a trick Athena taught him: he avoided Medusa’s gaze by looking instead at her reflection in his shield. Using this mirror tactic, he was able to approach close enough to cut off her head. Even after death, Medusa’s head retained its power to turn onlookers into stone. Perseus incorporated the head into a shield, the Aegis (literally translated from the Greek as “the skin of a female goat”; cf. Dylan’s “she goat” reference), which he gave to his divine benefactor Athena.

In modern times Medusa has become the exemplary witchy woman because of the anxieties she provokes from sketchy men. For Freud, Medusa was the ideal emblem of male castration anxiety. In his essay “Medusa’s Head,” Freud offers an interpretation of the Gorgon that is so…well, so Freudian, that a century later ChatGPT could have written it for him.

To decapitate = to castrate,” he asserts. “The terror or Medusa is thus a terror of castration that is linked to the sight of something. Numerous analyses have made us familiar with the occasion for this: it occurs when a boy, who has hitherto been unwilling to believe the threat of castration, catches sight of the female genitals, probably those of an adult, surrounded by hair, and essentially those of his mother. (273)

But Freud notes that Medusa effectively gives back what she takes away:

The sight of Medusa’s head makes the spectator stiff with terror, turns him to stone. Observe that we have here once again the same origin from the castration complex and the same transformation of affect! For becoming stiff means an erection. Thus in the original situation it offers consolation to the spectator: he is still in possession of a penis, and the stiffening reassures him of the fact. (273)

I’m not defending Freud’s diagnosis. I’m simply laying out his interpretation because it has had such an influential impact on how Medusa is viewed. She is at once the object of male desire and the destroyer of sexual potency. Perseus preemptively chops off her head, with those writhing phallic snakes, before she can chop his off. Yet she also turns men to stone: literally hard as a rock. Medusa cuts it off and she pumps it up.

The singer might as well be gazing at Medusa on the songs from This Year’s Model. Anxieties about threats posed by powerful women, and fears about sexual inadequacy, recur in almost every song. In the opening track, “No Action,” one wonders if the singer is still referring to the telephone when he admits,

But when I hold you like I hold that Bakelite in my hands

There’s no action

There’s no action

There’s no action

That thing in his hand just won’t work, can’t make a connection, is incapable of action. For years I didn’t know that Bakelite was the substance phones were made of. I thought Costello was referring to a gun [I was probably confusing Bakelite with Armalite, the IRA’s weapon of choice.] In the present context, however, I think my misreading still captures the essential point. This guy is shooting blanks, but he blames and punishes women for his own failures, using them for target practice.

Similarly, when our flaccid hero tries to “pump it up,” his efforts are futile:

Pump it up

Until you can feel it

Pump it up

When you don’t really need it

Dylan shows he’s in on the joke in his translation: “you want to blow this whole thing up until it’s swollen, where you’ll run your hands all over and squeeze it till it collapses” (8). He opens the chapter with an image of a boy innocently pumping up his bicycle tire. But Dylan knows as well as Costello that the dysfunctional thing being pumped up in this song is closer to hand and much more salacious.

Of course, Dylan is no stranger to impotence metaphors, though he typically plays them for humor rather than vindication. Knowing that “Pump It Up” borrows its rhythmic structure from Dylan’s “Subterranean Homesick Blues,” I wonder if Costello’s central image for sexual dysfunction comes from the same song: “The pump don’t work / ’Cause the vandals took the handles.” Or from “Please Mrs. Henry”:

Look, Missus Henry

There’s only so much I can do

Why don’t you look my way

And pump me a few?

Or from “Goin’ to Acapulco”:

Well, sometime you know when the well breaks down

I just go pump on it some

Rose Marie, she likes to go to big places

And just sits there waitin’ for me to come

Before leaving the Medusa connection behind, I should point out the feminist backlash against Freudian interpretations of the myth. The most famous rebuttal comes from Hélène Cixous in her groundbreaking essay “The Laugh of the Medusa.” She mocks the male obsession with castration anxiety which has led to such a distorted misrepresentation of Medusa: “Wouldn’t the worst be, isn’t the worst, in truth, that women aren’t castrated, that they have only to stop listening to the Sirens (for the Sirens were men) for history to change its meaning? You only have to look at the Medusa straight on to see her. And she’s not deadly. She’s beautiful and she’s laughing” (424). It’s a brilliant revisionist counternarrative: the laughing Medusa. And what is Medusa laughing at? The limp-dicks who perniciously misinterpret the feminine life-force as an emblem of death to be feared:

Men say that there are two unrepresentable things: death and the feminine sex. That’s because they need femininity to be associated with death; it’s the jitters that give them a hard-on! for themselves! They need to be afraid of us. Look at the trembling Perseuses moving backward toward us, clad in apotropes. What lovely backs! Not another minute to lose. Let’s get out of here. (424)

“Come on-a My House” by Rosemary Clooney

“This is a song of seduction” begins Dylan (279). He’s right.

Come on-a my house, my house a-come on

Come on-a my house, my house a-come on

Come on-a my house, my house, I’m gonna give-a you candy

Come on-a my house, my house, I’m gonna give-a you everything

Everything, everything, everything, everything

Written by Ross Bagdasarian and William Saroyan, the song was turned into a hit in 1951 by Rosemary Clooney. In her autobiography Girl Singer, Clooney admits that she never liked “Come on-a My House”:

I didn’t have any appreciation for the song’s slightly tongue-in-cheek, self-parodic edge. I thought the lyric ranged from incoherent to just plain silly, I thought the tune sounded more like a drunken chant than an historic folk art form, and I hated the gimmicky arrangement: it was orchestrated for jazzed-up harpsichord, of all things, with a kind of calypso rhythm. I was afraid once people heard it, they wouldn’t take me seriously as a singer capable of more than “I’m gonna give-a you candy.” (74)

She initially balked at recording the song at all, but when producer Mitch Miller threatened to fire her if she didn’t, she acquiesced.

In the studio, Clooney continued to struggle with the song: “I was having trouble investing the lyrics with genuine feeling. The silly words were also uncomfortably suggestive—‘I’m gonna give-a you everything’—and I didn’t know how to work the combination of playfulness and seductiveness; it didn’t seem to mix” (76). The producer took his “girl singer” aside for some paternalistic advice: “Now he put his arm around my shoulders. ‘Look at it this way,’’ he told me, as if he knew exactly what wasn’t clicking. ‘You are asking this boy over to your house because you’re going to marry him.’” Clooney’s reaction? “It was simplistic; it was pretense; it was quintessentially ’50s. And it worked” (76).

Rosemary Clooney sings “Come on-a My House” on The Rosemary Clooney Show in 1956. YouTube video by Songs of the Heart.

Fifties America is the home base Dylan keeps returning to in PoMS. “Come on-a My House” is yet another example of how songs from that decade anticipate in nascent form the musical and sexual revolutions of the sixties. Think about the journey from “Come on-a My House” to Dylan’s “If You Gotta Go, Go Now (Or Else You Got to Stay All Night)” to the Rolling Stones’ “Let’s Spend the Night Together.” The pretense and subterfuge are progressively stripped away, revealing a shared bedrock of sexual seduction. Dylan responds to the thrill of enticement and sexual awakening embedded in “Come on-a My House”: “This song is gesturing at you to discover yourself. It’s coaxing you, enticing you to come out of retirement and jump in. Are you tempted? You bet. But you’re not thinking about what will happen if you’re lured in there, you’re thinking about what could happen” (281).

What will happen if you take the bait and taste the forbidden fruit? Dylan interprets “Come on-a My House” as a deadly trap set by a sexual predator.

This is the song of the deviant, the pedophile, the mass murderer. The song of the guy who’s got thirty corpses under his basement and human skulls in the refrigerator. This is the kind of song where a black car rolls down the street, a window rolls down and a voice calls out, “Do you want to come over here for a second, little girl? I got some pomegranates for you and figs, dates, and cakes. All kinds of erotic stuff, apples and plums and apricots. Just come on over here for a second.” This is a hoodoo song disguised as a happy pop hit. It’s a Little Red Riding Hood song. A song sung by a spirit rapper, a warlock. (283)

This is musical terrain Dylan knows well. Beginning with Time Out of Mind, every original album he has released contains at least one murder ballad masquerading as a torch song, a hoodoo song in disguise, a seemingly harmless love song that is really a demon-lover seduction, told from the killer’s perspective in first-person voice.

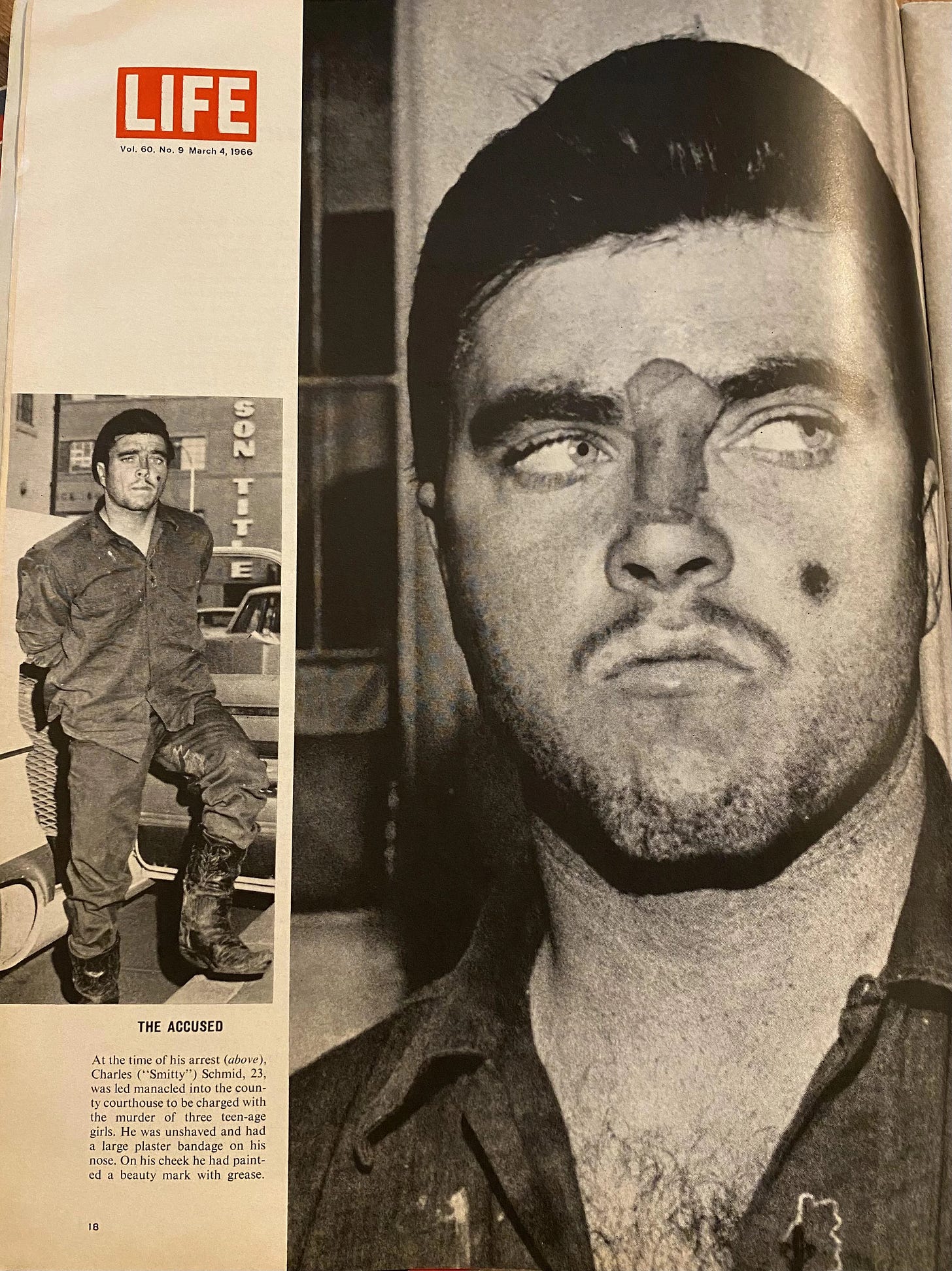

Joyce Carol Oates picked up on strains of “the deviant, the pedophile, the mass murderer” in Dylan’s music all the way back in 1965. She wrote the short story “Where Are You Going, Where Have You Been?” in part as a response to “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue.” Oates tells the story of 15-year-old Connie, who is pursued by a middle-aged creeper named Arnold Friend. He shows up at her house one Sunday afternoon, invites her for a ride, issues increasingly menacing innuendos, and finally threatens harm to her family if she doesn’t go with him. Arnold tells Connie, “‘The place where you came from ain’t there any more, and where you had in mind to go is cancelled out. This place you are now—inside your daddy’s house—is nothing but a cardboard box I can knock down any time. You know that and always did know it’” (999). Arnold is trying to seduce Connie out of her house, the opposite of “come on in my house,” but otherwise the seductions are strikingly similar. In a March 1986 piece for the New York Times, Oates identified three sources of inspiration for “Where Are You Going, Where Have You Been?” One was Dylan: “Written at a time when the author was intrigued by the music of Bob Dylan, particularly the hauntingly elegiac song, ‘It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue,’ it was dedicated to Bob Dylan.” Another source was a medieval German engraving, “an allegory of the fatal attractions of death (or the devil). An innocent young girl is seduced by way of her own vanity.” But her main inspiration was Charles Schmid, Jr., a serial killer who preyed on teen girls in the mid-1960s and was nicknamed “The Pied Piper of Tucson.”

Call him the Pied Piper or call him the Big Bad Wolf, this is the kind of deviant that sprang to mind for Oates while listening to Bringing It All Back Home, and this is the kind of deviant that sprang to mind for Dylan while listening to “Come on-a My House.”

I must say, however, that I hear Clooney’s song differently than Dylan. In his riffs for PoMS, Dylan is nimbly adept at losing himself in songs and inhabiting the persona of the singer. His commentaries, on the other hand, generally hold the song at arm’s length and view them with somewhat more objectivity. In his commentary for “Come on-a My House,” Dylan uses masculine pronouns to describe the sexual predator using sweets to lure in his next victim: “The song of the guy who’s got thirty corpses under his basement and human skulls in the refrigerator” (283). That’s a fair reading as written. But as Dylan stresses time and again, songs are much more than lyrics on a page.

He neglects to heed his own lesson when he writes about a sketchy man tricking and trapping a vulnerable girl to “come on-a my house.” That is not what we hear in Clooney’s performance. It’s not what we hear in any of the best renditions of this song, all of them by women: Ella Fitzgerald, Julie London, Eartha Kitt, Bette Midler, and Imelda May, to list only my favorites. Bagdasarian and Saroyan may have written “the song of the deviant, the pedophile, the mass murderer”; that’s what the male critic Dylan reads, and that’s what the male singer Dylan would do with the song in performance. Listen to any of the renditions above, however, and you’ll hear an entirely different song. Those women are nobody’s victim: they’re in full control. Yes, the song drips with sexuality, but it’s not the drool of some creepy candyman or Big Bad Wolf. It’s the sweat of a grown-ass woman—Big Red Riding Hood—no longer hooded and ready to ride.

I agree with Dylan that “Come on-a My House” is a Riding Hood song, but it’s not sung by a warlock. A better touchstone would be “The Company of Wolves,” Angela Carter’s reimagination in her collection of revisionist fairy tales The Bloody Chamber. In Carter’s bold and sexually assertive revision, as LRH and BBW draw closer, the girl’s eyes grow wide, not with fear but desire:

What big teeth you have!

She saw how his jaw began to slaver and the room was full of the clamour of the forest’s Liebestod but the wise child never flinched, even when he answered:

All the better to eat you with.

The girl burst out laughing; she knew she was nobody’s meat. She laughed at him full in the face, she ripped off his shirt for him and flung it into the fire, in the fiery wake of her own discarded clothing. The flames danced like dead souls on Walpurgisnacht and the old bones under the bed set up a terrible clattering but she did not pay them any heed. (118)

Carter’s LRH is nobody’s victim, nobody’s meat. All the comings and goings in that house take place with her knowledge and consent, under her control and for her pleasure. Rather than repeating the traditional fairy tale versions, which alternately have the helpless girl devoured by the wolf or saved by the mighty woodsman, Carter curls up her tale with a postcoital denouement: “See! sweet and sound she sleeps in granny’s bed, between the paws of the tender wolf” (118).

This feminist revision of Little Red Riding Hood seems more compatible with the song as sung than the serial rapist/killer commentary offered by Dylan. Reimagined by strong female vocalists in full command, “Come on-a My House” essentially becomes a sister song to “Let’s Spend the Night Together,” a celebration of sensual indulgence aimed at mutual satisfaction:

Don’t you worry ’bout what’s on your mind, oh my

I’m in no hurry, I can take my time, oh my

I’m going red and my tongue’s getting tied

Tongue’s getting tied

I’m off my head and my mouth’s getting dry

I’m high, but I try, try, try, oh my

The better to eat you with indeed! Care to comment, Ms. Hood?

“Witchy Woman” by the Eagles and “Black Magic Woman” by Santana

Some of Dylan’s most outlandish writing about women appears in Chapters 52 and 56. The titles “Witchy Woman” and “Black Magic Woman” are similar, and Dylan treats these two songs/chapters as companion pieces. I’ve already quoted the most controversial passage from the “Witchy Woman” entry in my introduction, but that is certainly not the only example of language about women which seems over-the-top and out-of-bounds. Consider this: “The old coot’s got a volatile spirit, banished everything sacred and pure from your life, and regresses you to a childlike state. She’s hot as pepper, foul-tasting, she’s one crazy bitch, made you a prisoner of your inner demons” (255). Are you chuckling, dear reader? Or groaning? Or fuming?

When Dylan turns his attention to “Black Magic Woman,” you think at first that he’s prepared to respect the power of the feminine divine: “The Black Magic Woman is the ideal woman—summons demons, holds séances, levitates, is skilled in the art of necromancy, conducts ritualistic orgies with the dead, always out of body, a creature with dark powers and you’ve got her all to yourself” (269). She has everything she needs, she’s a goddess—but she belongs to me. Over the course of the chapter we find references to the Black Magic Woman as a cow, bird, horse, dog, bull-dyke, and spider woman. “She feeds on the entrails of your victims, and if you pull back her skin, you’ll see the head of an animal” (271). How much more dehumanizing could a profile get?

I understand how someone could read these chapters and conclude that Dylan had devolved into a crotchety old coot himself. Within the larger context of the book, however, I think these depictions of feminine ferocity serve a different and more integral function. I needed some help to see it. It took re-reading an essay by Rennie Sparks to open up my mind to another conceivable point of view.

Rennie Sparks is best known as half of the musical duo The Handsome Family. She contributed my favorite chapter to the 2005 collection The Rose & the Briar: Death, Love and Liberty in the American Ballad, edited by Sean Wilentz and Greil Marcus. Her primary focus is on “Pretty Polly,” but she uses this song as a launch pad into broader meditations on women’s roles in religion, mythology, ecology, American history, and murder ballads. It’s a fantastic piece that deserves to be better known among Dylanologists. Let me share some of Sparks’s illuminations that shed light on gender dynamics in The Philosophy of Modern Song.

Sparks establishes the attraction/repulsion tension in “Pretty Polly” specifically, and in murder ballads in general, with her opening paragraph:

The first time you hear “Pretty Polly,” you giggle nervously. The dark forest flowing with blood, the beautiful girl, the open grave—it makes you dizzy with a strange mix of horror and delight. The flat, vaguely medieval melody circles and drones. The chant rises in fury as the words round their dusky path. Cryptic signifiers flash through your head—red blood, white skin, dark grave. (37)

“Pretty Polly” was part of Dylan’s early folk repertoire, as captured in a powerful 1961 live recording at the Gaslight Café. Sparks doesn’t name any specific renditions, though her description reminds me most of Jean Richie’s haunting 1963 performance at Folk City, accompanied by Doc Watson. Sparks mentions that the murder ballad “Pretty Polly” is close kin to “Knoxville Girl,” but she doesn’t mention the fact that The Handsome Family did a mesmerizing cover of “Knoxville Girl” for their 2003 album Smothered and Covered.

“Pretty Polly” derives from older European ballads like “The Gosport Tragedy” and “Lady Isabel and the Elf Knight.” These predecessors contained more resistance from the woman and more punishment for her assailant. Such elements did not survive the journey across the Atlantic to Appalachia, however. “In America,” observes Sparks, “Polly is a mannequin, an empty shell. She wreaks no vengeance. She doesn’t even struggle to live. She is limp, weepy, slaughtered without struggle. Her lily-white breast is already corpselike. She is dead before the knife cuts her” (42). The American Polly seems the quintessential victim, utterly powerless against Willie’s sadistic attack. “In some versions of the song, he stabs her in the heart without saying another word. Sometimes, though he lingers there with his suspicions. He’s sure that hiding somewhere under Polly’s pure, white veils there is a dirty slut who deserves to die” (38). But when Sparks looks behind the veil of “Pretty Polly,” she doesn’t see a dirty slut—she sees a repressed goddess.

In my commentary on The Philosophy of Modern Song, I keep referring to Dylan’s “art of the unsaid.” It’s gratifying to find Rennie Sparks invoking the same principle: “In murder ballads, the magic is in the mystery, the parts left unsaid. Like the wordless, unspeakable parts of our own psyche, murder ballads hold secrets that loom larger the farther down they’re pushed. The more holes we cut in these songs, the more powerful they become” (39). Sparks argues that the wordless, unspeakable, mysterious power of murder ballads resides in repressed but palpable feminine power. Her remarkable description of this power is worth quoting at length, not only because she’s so spot-on, but also because her language jives so well with Dylan’s vivid descriptions of voracious women in PoMS:

This powerful witching woman surrounded by birds and blood is the dark shadow of the demon goddess who once flew naked through the ancient wilds of Europe and the Middle East. She is the serpent that coiled out of Eve’s mouth to destroy the world. She is the wicked witch who baked children in her oven. She is the great Astarte, once worshipped with human sacrifice and sexual orgies and now remembered only in Easter eggs and bunnies. She is Circe the she-falcon, who turned men into pigs. She is the winged Harpy—the furiously hungry woman with razor-sharp talons. She is Lilith, the original wife of Adam, who sprouted wings and rose into the night as a raging she-demon when Adam tried to make her lie down for sex. (41)

How’s that for a genealogy of witchy women! I think this is the same vision, mythos, and legacy Dylan is trying to channel in several of the wildest and weirdest passages from PoMS. It may be harder to swallow coming from a Boomer man than from Sparks, but I think they’re tuning into very similar frequencies.

For Sparks, and I think for Dylan as well, feminine and masculine forces are in perpetual tension, but each is necessary as a counterbalance against the other. Sparks asserts, “Greek logic, the paternal Christian trinity, the great hero-warrior—all the ideals of Western thought—rose in opposition to the swampy stench of the goddess. She is the dark bog trampled under the fortress of the rational Western mind. But she could not be completely silenced.” Sparks also drafts Medusa into service to prove her point: “In folktale and myth, the goddess is every monster ever beheaded by a hero’s sword. Behind her raging maw always lies a chained damsel awaiting rescue. But, even in the lily-white breast of the virgin, the goddess lurks, waiting to awaken” (41). Like Perseus, Willy strikes against Polly out of fear for her hidden power and sexuality. But Medusa gets the last laugh. “Unclothed in the forest—her horrible hair a twisted mass of snakes, her body dripping with the flood of the womb and the maggots of death—the goddess may kill men with an effortless glance. […] The goddess shrinks men to playthings. Like dead Polly with her sharpened claws, the goddess tears men apart with her accusing eye” (Sparks 41).

I don’t know if Dylan has read the Sparks essay, so I can’t hypothesize a direct influence on The Philosophy of Modern Song (though I don’t discount the possibility either). My point is that, whether they followed the same path or different ones to get there, both Sparks and Dylan arrive at a similar place. The songs each author studies include disturbing acts of violence stemming from fear and hatred, bloodlust and revenge. Both writers use graphic language to describe these characters and behaviors, running the risk of alienating some readers, even as they inform and enlighten others. Murder ballads feature men stabbing, shooting, choking, drowning, and/or burying their helpless lovers, but in the background Sparks hears Medusa laughing at an emasculated Perseus who will never keep her down. I think Dylan hears and echoes that same response. Sparks exhumes the buried goddess and provides an outlet for the return of the repressed. Dylan’s depiction of fierce, voracious, irrepressible, witchy women in certain chapters of PoMS seems to serve a similar function. Those sections balance out his portraits of psycho-killers and generally sketchy men in other entries. Viewed in relation to one another across the span of The Philosophy of Modern Song, Dylan’s dueling gender dynamics reenact the dramatic conflicts and animating tensions of murder ballads so perfectly captured by Rennie Sparks.

Works Cited

Carter, Angela. “The Company of Wolves.” The Blood Chamber. Penguin, 1979, pp. 110-18.

Cixous, Hélène. “The Laugh of the Medusa,” translated by Keith Cohen and Paula Cohen. Feminisms Redux: An Anthology of Literary Theory and Criticism, edited by Robyn Warhol-Down and Diane Price Herndl. Rutgers University Press, 2009, pp. 416-31.

Costello, Elvis. “No Action.” This Year’s Model. Radar, 1978.

---. “Pump It Up.” This Year’s Model. Radar, 1978.

Dylan, Bob. “Goin’ to Acapulco.” The Basement Tapes. Columbia, 1975.

---. The Philosophy of Modern Song. Simon & Schuster, 2022.

---. “Please Mrs. Henry.” The Basement Tapes. Columbia, 1975.

---. “Subterranean Homesick Blues.” Bringing It All Back Home. Columbia, 1965.

Flanagan, Bill. “The Last Elvis Costello Interview You’ll Ever Need to Read.” Musician (March 1986), http://www.elviscostello.info/wiki/index.php/Musician,_March_1986.

Freud, Sigmund. “Medusa’s Head.” The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, vol. 18, translated and edited by James Strachey. Hogarth Press, 1955, pp. 273-74.

Gabrin, Chris. “Elvis Costello: This Year’s Model Session. Snap Galleries, https://www.snapgalleries.com/product/chris-gabrin-elvis-costello-this-years-model-session/.

McCombe, John. “‘A Complete Loser’: Masculinity and its Discontents in Elvis Costello’s My Aim Is True and This Year’s Model.” Journal of Popular Music, vol. 21, no. 2, 2009, pp. 192-212.

Oates, Joyce Carol. “When Characters from the Page Are Made Flesh on the Screen.” New York Times (23 March 1986), https://www.nytimes.com/1986/03/23/movies/when-characters-from-the-page-are-made-flesh-on-the-screen.html.

---. “Where Are You Going, Where Have You Been?” The Story and Its Writer, 8th edition, edited by Ann Charters. Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2011, pp. 988-1000.

Pareles, Jon. “Below the Belt.” Crawdaddy (June 1978), http://www.elviscostello.info/wiki/index.php/Crawdaddy,_June_1978.

The Rolling Stones. “Let’s Spend the Night Together.” Between the Buttons. Decca, 1967.

Sparks, Rennie. “‘Pretty Polly.’” The Rose & the Briar: Death, Love and Liberty in the American Ballad, edited by Sean Wilentz and Greil Marcus, W. W. Norton, 2005, pp. 37-49.

Beautiful. Beyond good and bad. We are so limited in casting our judgements. I have no doubt that Bob admires the awesome and terrifying power of women. Especially as regards their place in myth and song, and so in real life. I will keep reading anything you write, Graley. It’s fun to see someone willing and able to go this deep. So much Bob talk stays on the surface. Thanks!

Thank you for another unique take on this fascinating book. It will send me back for yet another reading of some of the relevant sections. I remember you saying that people will be studying this work for years. I am still trying to wrap my head about what it is Dylan is doing in his riffs and commentary. Like so much of what he does, he approaches these songs like no one else has before and I am not sure we get it yet. Very much looking forward to hearing you and Laura in Tulsa.