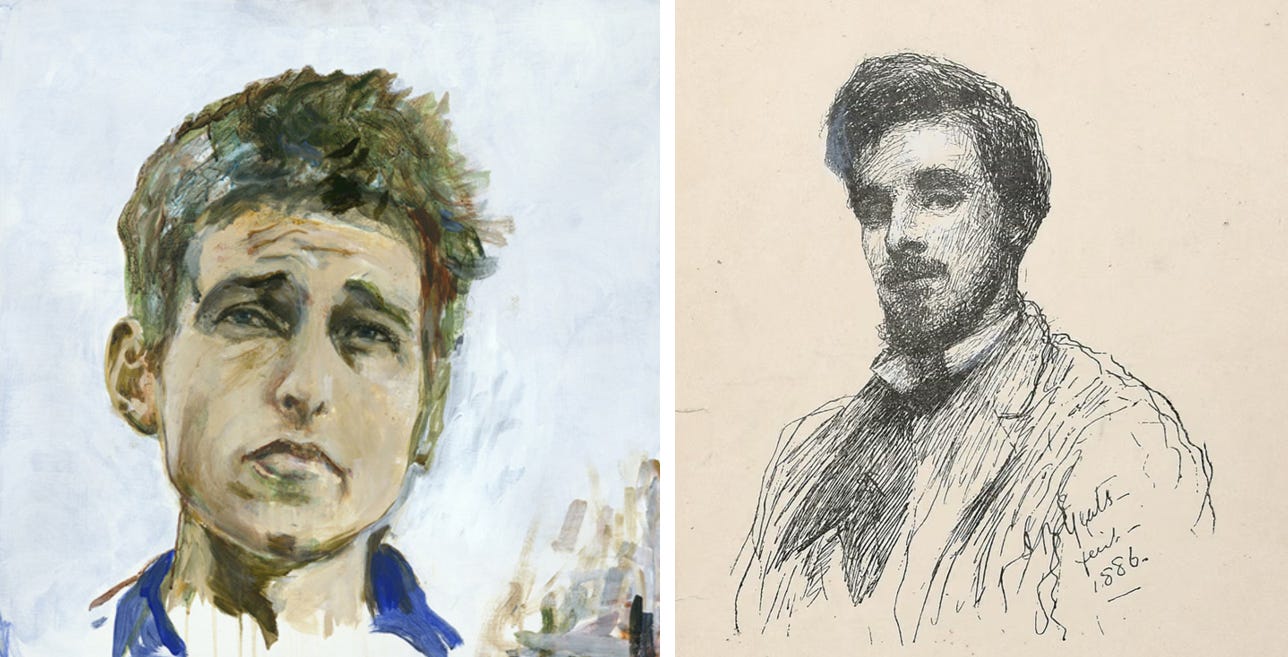

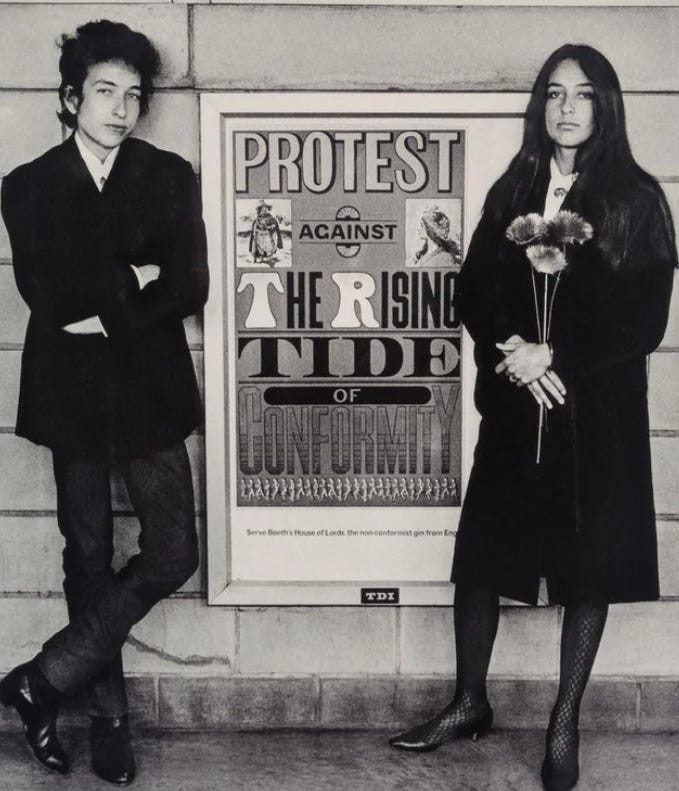

Yeats & Dylan

Part 1: Voices of Their Generations

Bob Dylan is in Ireland! As I type these words, he is in the middle of a two-night stand in Belfast. From there the Rough and Rowdy Ways Tour will head south for a couple concerts in Killarney before concluding this European leg in Dublin on November 25. For a while now, I’ve been considering writing about resonances I hear between my favorite singer-songwriter and my favorite poet. Since this is Irish week in Dylan world, I figured that now is as good a time as any to share these thoughts about Bob Dylan and William Butler Yeats.

You probably know that both men won the Nobel Prize in Literature: Yeats in 1923, Dylan in 2016. But their similarities run much deeper than that. Both artists established themselves as major forces in their twenties. Both initially identified as folkies, but they soon began engaging with major socio-political crises of their times. Both also had contentious relationships with their audiences: many supporters who once championed them as “voices of their generation” later turned against them as traitors to the cause.

Yeats and Dylan both evolved significantly over the courses of their long and prolific careers, adopting different masks and experimenting with various voices. Both were Muse poets who became expert at chasing uncatchable women through their love lyrics. Both went through intense religious periods that impacted their art—Theosophy and various occult beliefs for Yeats, evangelical Christianity for Dylan—though both ultimately proved much better poets and performers than preachers and proselytizers. Both had highly eclectic interests, producing art for multiple media throughout their careers. Finally, both Yeats and Dylan remained remarkably active, innovative, and relevant late in life. Rather than resting on the laurels of their Nobel Prizes, both men continued to explore and reinvent, offering some of their deepest meditations on mortality, legacy, continuity, and the vitality of imagination long past the age at which most artists have retired or run out of steam.

Yeats is a centerpiece of the Modern Irish Literature course I’ve been teaching regularly for nearly thirty years. I also focused a lot on Yeats in over a dozen trips to Ireland in Xavier University’s study abroad program. This is a topic close to my heart. So please indulge me while I play professor and share some observations about Dylanesque Yeats and Yeatsian Dylan. I won’t attempt to cover everything, not even close. But I think there’s enough here for a selective three-part series placing two of my all-time favorite artists into conversation with one another.

Dylan on Folk Music

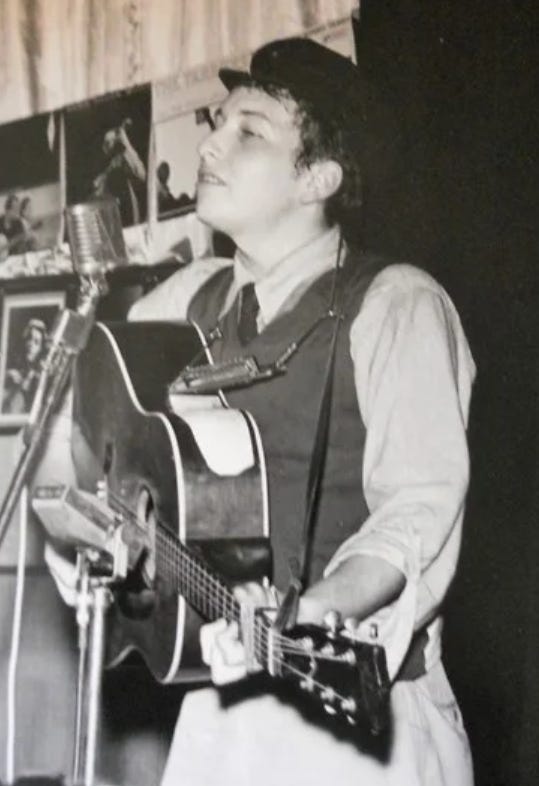

As you know, when Dylan arrived on the scene in Greenwich Village in 1961, he was completely devoted to folk music. In Chronicles, he describes its total hold over him:

Folk music was a reality of a more brilliant dimension. It exceeded all human understanding, and if it called out to you, you could disappear and be sucked into it. I felt right at home in this mythical realm made up not with individuals so much as archetypes, vividly drawn archetypes of humanity, metaphysical in shape, each rugged soul filled with natural knowing and inner wisdom. Each demanding a degree of respect. I could believe in the full spectrum of it and sing about it. It was so real, so more true to life than life itself. It was life magnified. Folk music was all I needed to exist. (236)

Dylan began writing more and more of his own songs in the early sixties, and soon these originals displaced folk standards from his repertoire. After controversially “goin’ electric” in 1965, his sound and celebrity became much more associated with rock music. However, in the fullness of time, we can look back and recognize that he never lost the faith. At key junctures when he seemed to have lost his way, Dylan turned back to folk music as his charging station and North Star, refueling his depleted energies and redirecting him toward his true vocation. See The Basement Tapes, Self Portrait, the acoustic sets of the Never Ending Tour, Good as I Been to You, World Gone Wrong, etc.

Dylan himself has explicitly testified to folk music’s enduring importance for his work. In an oft-quoted New York Times interview in 1997, he told Jon Pareles:

Those old songs are my lexicon and my prayer book. All my beliefs come out of those old songs, literally, anything from “Let Me Rest on That Peaceful Mountain” to “Keep on the Sunny Side.” You can find all my philosophy in those old songs. I believe in a God of time and space, but if people ask me about that, my impulse is to point them back toward those songs. I believe in Hank Williams singing “I Saw the Light.” I’ve seen the light, too.

He reiterated the formative influence of folk music on his art in the brilliant 2015 MusiCares Person of the Year speech:

I learned lyrics and how to write them from listening to folk songs. And I played them, and I met other people that played them back when nobody was doing it. Sang nothing but these folk songs, and they gave me the code for everything that’s fair game, that everything belongs to everyone. For three or four years all I listened to were folk standards. I went to sleep singing folk songs. I sang them everywhere, clubs, parties, bars, coffeehouses, fields, festivals. And I met other singers along the way who did the same thing and we just learned songs from each other.

Dylan paid his debts once again in his Nobel Lecture, crediting folk music with teaching him how to write and sing the songs that earned him the world’s top literary prize:

By listening to all the early folk artists and singing the songs yourself, you pick up the vernacular. You internalize it. You sing it in the ragtime blues, work songs, Georgia sea shanties, Appalachian ballads and cowboy songs. You hear all the finer points, and you learn the details. […] I had all the vernacular down. I knew the rhetoric. None of it went over my head—the devices, the techniques, the secrets, the mysteries—and I knew all the deserted roads that it traveled on, too. I could make it all connect and move with the current of the day. When I started writing my own songs, the folk lingo was the only vocabulary that I knew, and I used it.

He knew his song well before he started singing, and its lexicon came from folk music. Dylan’s fervent commitment to this art form, interpreted within a contemporary American context, mirrors Yeats’s likeminded allegiances to folk art in a specifically Irish context.

Yeats on Folk Art

Yeats articulates the timeless appeal of folklore, folk music, and folk art in general in his early book of essays The Celtic Twilight, first published in 1893 when Yeats was 28 years old. In a section called “By the Roadside,” he recounts an epiphany while listening to Irish folk songs on the Kiltartan road in County Galway:

The voices melted into the twilight, and were mixed into the trees, and when I thought of the words they too melted away, and were mixed with generations of men. Now it was a phrase, now it was an attitude of mind, an emotional form, that had carried my memory to older verses, or even to forgotten mythologies. I was carried so far that it was as though I came to one of the four rivers, and followed it under the wall of Paradise to the roots of the trees of knowledge and of life. (232)

Unsympathetic listeners may dismiss folk music as simplistic music played by unsophisticated people, but Dylan and Yeats find profound nobility in this art form. Remember that Dylan described folk music as a “mythical realm” populated with “vividly drawn archetypes of humanity” and imbued with deep “inner wisdom.” Yeats tunes into that same frequency. He asserts, “There is no song or story handed down among the cottages that has not words and thoughts to carry one as far, for though one can know but a little of their ascent, one knows that they ascend like medieval genealogies through unbroken dignities to the beginning of the world” (232). Yeats goes so far as to claim:

Folk art is, indeed, the oldest of the aristocracies of thought, and because it refuses what is passing and trivial, the merely clever and pretty, as certainly as the vulgar and insincere, and because it has gathered into itself the simplest and most unforgettable thoughts of the generations, it is the soil where all great art is rooted. (232-33)

That same year, in a piece called “The Message of the Folk-lorist” (1893), Yeats expanded upon his belief in folk art as the soil of all great literature: “Folk-lore is at once the Bible, the Thirty-nine Articles, and the Book of Common Prayer, and well-nigh all the great poets have lived by its light. Homer, Aeschylus, Sophocles, Shakespeare, and even Dante, Goethe, and Keats were little more than folk-lorists, with musical tongues.” Notice how closely Yeats’s convictions resonate with Dylan’s creed of folk songs as “my prayer book.”

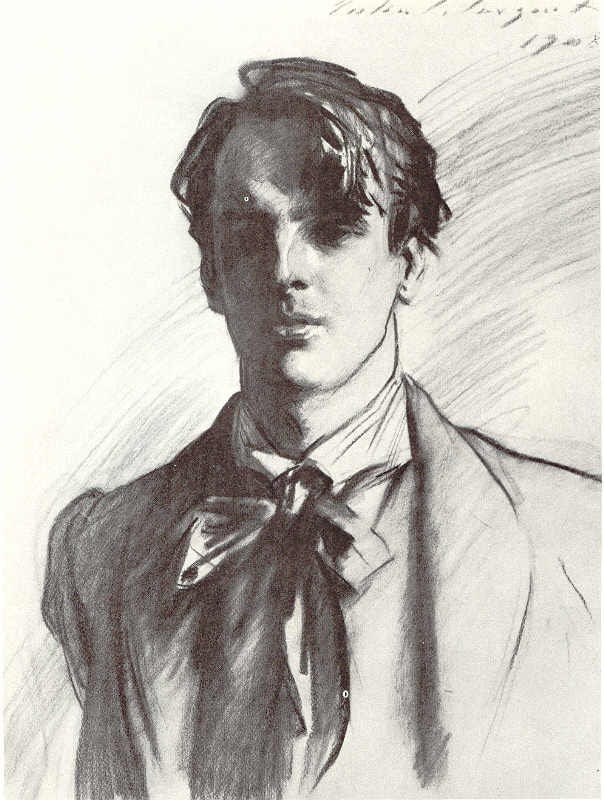

Yeats became the most outspoken and accomplished artist in the Celtic Revival, a cultural movement aimed at reviving native Irish myths, legends, and folklore. That project involved rescuing Irishness from the prevailing ridicule of English misrepresentation and Hibernophobic propaganda. “The Stolen Child” (1886) is an excellent example of Yeats’s revivalist poetry.

The poem is set amid the natural beauty of “Yeats Country” in rural County Sligo. You don’t need to have visited there in person to get a sense of the place’s enchanting power from Yeats’s lyrical description:

Where dips the rocky highland

Of Slewth Wood in the lake,

There lies a leafy island

Where flapping herons wake

The drowsy water rats;

There we’ve hid our faery vats,

Full of berries

And of reddest stolen cherries.

“The Stolen Child” is a poem about faeries. By the late 19th century, faery folklore was generally disparaged as the quaint superstition of backwards people. But Yeats approaches this subject with nuance and complexity. The speaker is a faery addressing a mortal child:

Come away, O human child!

To the waters and the wild

With a faery, hand in hand,

For the world’s more full of weeping than you can understand

The faery depicts mortal life as one of hardship and toil. By contrast, life with the faeries is a paradise of boundless pleasure and a nonstop party:

Far off by farthest Rosses

We foot it all the night

Weaving olden dances

Mingling hands and mingling glances

Till the moon has taken flight.

The scene sounds similar to Yeats’s beatific trad night described in The Celtic Twilight. However, in the final verse, after the child is persuaded to go, the faery reveals all the things the lad will miss as a complete unknown with no direction home.

Away with us he’s going,

The solemn-eyed:

He’ll hear no more the lowing

Of the calves on the warm hillside; Or the kettle on the hob

Sing peace into his breast.

Yeats addresses a subject typically dismissed as silly, or else degraded through sentimental claptrap, and gives it the serious treatment it deserves. Instead of reproducing the caricatures typical of the period, he creates a complicated poem of seduction and abduction—not the emancipated child but the stolen child—along with a folkloric renunciation of modernity’s vale of tears.

In his groundbreaking book Inventing Ireland: The Literature of the Modern Nation, Declan Kiberd studies the dialectical relationship between England and Ireland. For hundreds of years, the English and Irish have defined themselves in opposition to one another. According to Kiberd, “The modern English, seeing themselves as secular, progressive and rational, had deemed the neighbouring islanders to be superstitious, backward and irrational. The strategy for the revivalists thus became clear: for bad words substitute good, for superstitious use religious, for backward say traditional, for irrational suggest emotional” (32). Yeats participates in just such a recuperation project in “The Stolen Child.” Employing revisionist strategies, Yeats and his fellow revivalists were able, in Kiberd’s words, “to take many images which were rejected by English society, occupy them, reclaim them, and make them their own” (32).

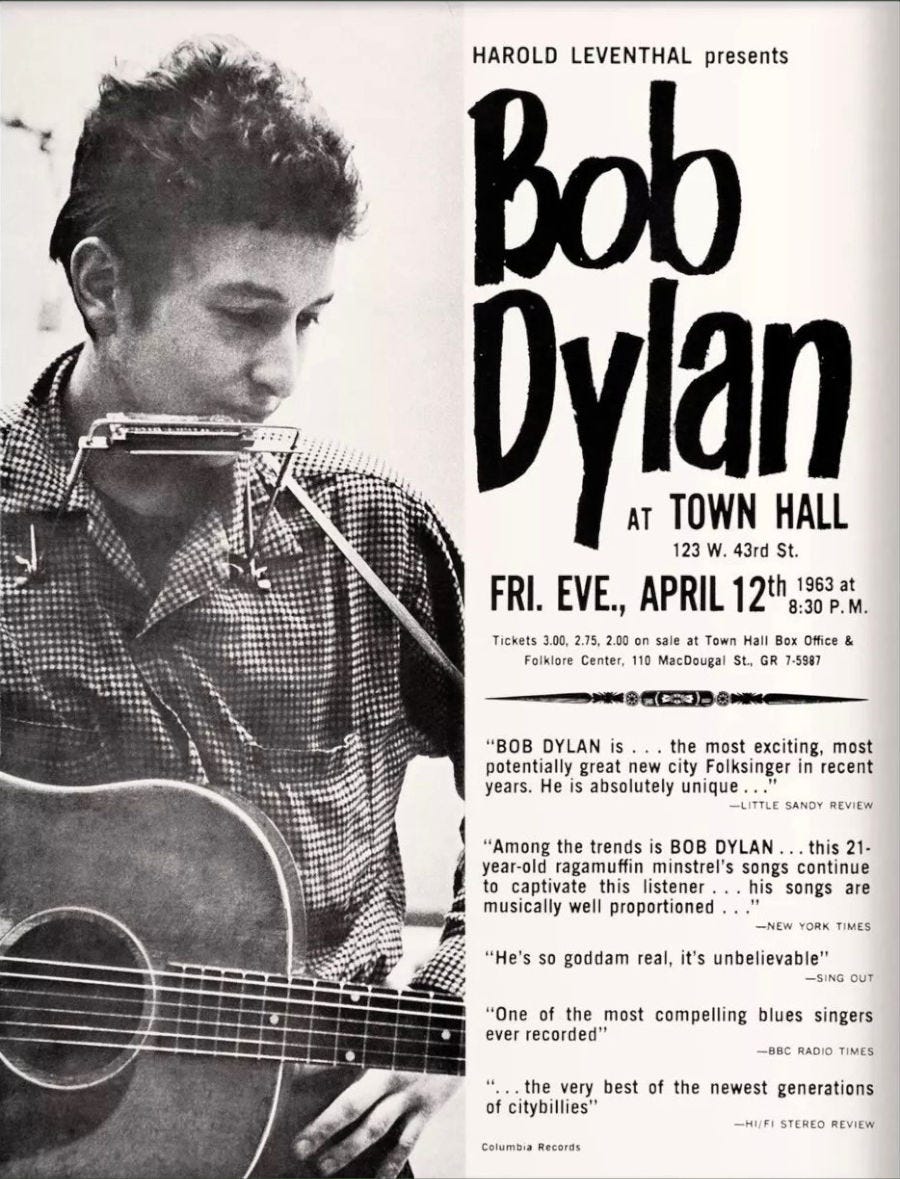

Dylan as Voice of His Generation

By 1963, Bob Dylan was widely embraced by thousands of young Americans as the chief spokesperson for their generation. He wrote and passionately performed songs about the subjects that politically aware, socially engaged and progressively oriented Baby Boomers cared most about. In Dylan Goes Electric!: Newport, Seeger, Dylan, and the Night that Split the Sixties, Elijah Wald draws the battle lines in terms of generational conflict:

Many young people felt their elders had let them down, regardless of political affiliation. The leaders of the USA and USSR looked very similar, a bunch of old men in suits arguing about how many megatons of nuclear warheads each would be allowed to build and how to maintain their balance of power. Simplistic as the generational framing might be, to a lot of young Americans the old leaders looked like their parents, and they were intensely aware that their parents were part of the problem, not the solution. (155)

Dylan gave voice to his generation’s amalgamation of rage, disappointment, frustration, and disgust at the world they were inheriting from their parents, combined with a tenacious hope for change and a determination not to remain silently idle in the face of perennial injustices.

Peter Yarrow of Peter, Paul and Mary declared in 1963: “‘Bob Dylan is the most important songwriter in the country today. He has his finger on the pulse of America’s youth’” (qtd. Shelton 164). That same year, Joan Baez claimed that Dylan had elevated the agitprop genre of protest songs into a true art form:

The majority of those “protest” songs are stupid. They’re without beauty. By contrast, there are Bob Dylan’s songs. They’re powerful as poetry and they’re powerful as music. Most of the others are powerful as neither. Their writers are just trying desperately to say something, but they don’t know how to say it. But Bob is expressing what all these kids want to say. (Hentoff 42)

In Wicked Messenger: Bob Dylan and the 1960s, Mike Marqusee sums up Dylan’s relationship with his generation this way: “However you measure Dylan’s subsequent achievements (and they are substantial), they do not enjoy the same umbilical relation to the turmoil of the times as the work of the sixties. This is a body of song tied to the unfolding political and cultural drama of its era in a way that the later work is not” (3).

Of course, we know how much Dylan grew to resent these unwanted labels and all the pressures and presumptions that came along with the honorific “voice of his generation.” In the film No Direction Home, he expresses bafflement at his anointment: “At a certain point people seemed to have a distorted, warped view of me for some reason. Those people were usually from outside the musical community. ‘The Spokesman of a Generation,’ ‘The Conscience of’ one thing or another. That I could not relate to. I just couldn’t relate to it.” He vents further disdain in Chronicles:

I had been anointed as the Big Bubba of Rebellion, High Priest of Protest, the Czar of Dissent, the Duke of Disobedience, Leader of the Freeloaders, Kaiser of Apostasy, Archbishop of Anarchy, the Big Cheese. What the hell are we talking about? Horrible titles any way you want to look at it. All code words for Outlaw. (120)

At the end of the day, it makes little difference that Dylan resents and rejects the burden placed on his shoulders (or wrapped around his neck). He didn’t apply for the job of “voice of his generation”: the Chosen One is chosen. Resistance is totally understandable, even to be expected, but it is also futile.

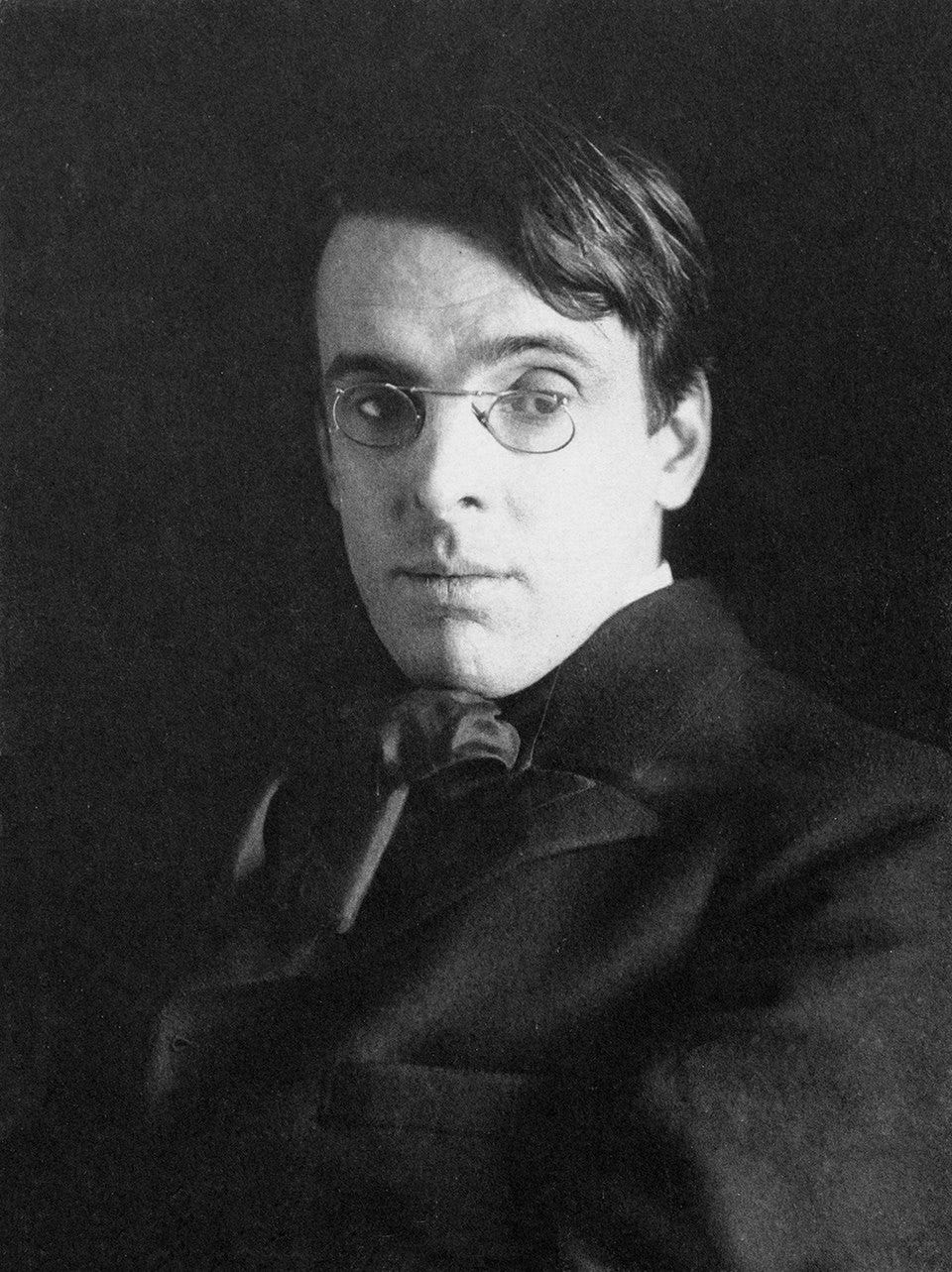

Yeats as Voice of His Generation

Yeats was also known as the “voice of his generation,” but his situation was significantly different. He actively sought the role of spokesman for the Irish cause, deliberately fashioning himself as a modern Irish bard at the head of a cultural vanguard.

Yeats was still in his twenties when he published the brief but rousing “Hopes and Fears for Irish Literature” (1892), a rallying cry to Irish writers to produce new literature rooted in their home culture. He frames his manifesto in terms of both national (Irish vs. English) and generational (young vs. old) oppositions. Referring to the disengaged and decadent poetry currently in vogue, Yeats reproaches,

It is not possible to call a literature produced in this way the literature of energy and youth. The age which has produced it is getting old and feeble, and sits in the chimney-corner carving all manner of curious and even beautiful things upon the staff that can no longer guide its steps. Here in Ireland we are living in a young age, full of hope and promise—a young age which has only just begun to make its literature. It was only yesterday that it cut from the green hillside the staff which is to help its steps upon the long road.

How many roads must an Irishman walk down before you call him a man? Young Yeats contends that the road forward is the same road that leads back to the glorious Irish past:

We have behind us in the past the most moving legends and a history full of lofty passions. If we can but take that history and those legends and turn them into dramas, poems, and stories full of the living soul of the present, and make them massive with conviction and profound with reverie, we may deliver that new great utterance for which the world is waiting.

The whole wide world is watching, insists this brash young self-appointed Irish bard. The key to making good on this promise, he counsels, is to “study all things Irish, until we know the peculiar glamour that belongs to this nation, and how to distinguish it from the glamour of other countries and other races. ‘Know thyself’ is a true advice for nations as well as for individuals.” However, in the spirit of honest self-knowledge, and in words that anticipate some of Yeats’s future clashes with his Irish audience, he also contends,

We must know and feel our national faults and limitations no less than our national virtues, and care for things Gaelic and Irish, not because we hold them better than things Saxon and English, but because they belong to us, and because our lives are to be spent among them, whether they be good or evil. Whether the power that lies latent in this nation is but the seed of some meagre shrub or the seed from which shall rise the vast and spreading tree is not for us to consider. It is our duty to care for that seed and tend it until it has grown to perfection after its kind.

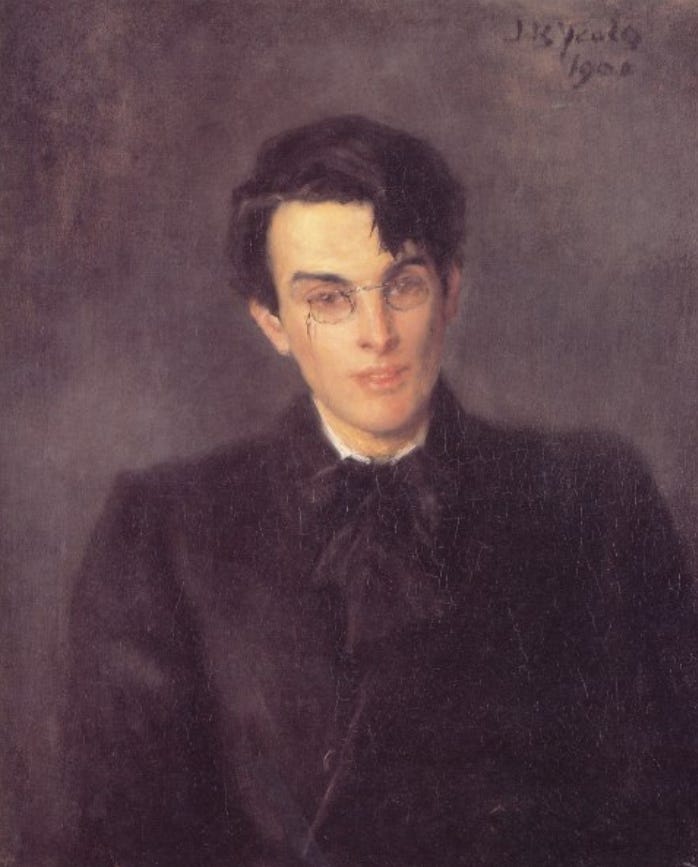

Yeats emerged as the leading voice of the most consequential generation in modern Irish history. As Declan Kiberd puts it, “It was the grand destiny of Yeats’s generation to make Ireland once again interesting to the Irish, after centuries of enforced provincialism […]. No generation before or since lived with such conscious national intensity or left such an inspiring (and, in some ways, intimidating) legacy” (3). Yeats’s biographer Roy Foster observes, “His best-known poetry defines for many people the Irish identity which was forged in revolution. […] He came to fame as the poet of the new Ireland, asserting its identity; his own discovery of his voice is often neatly paralleled with his country’s discovery of independence” (xxviii). To appreciate what made Yeats the “voice of his generation,” let’s turn our attention to his most iconic early poem, “The Lake Isle of Innisfree.”

Composed in 1888 and first published in 1890, “The Lake Isle of Innisfree” was Yeats’s first “hit” poem. I know I’m mixing genres here, but it really was massively popular, and he was asked to recite it at poetry readings for the rest of his career, much like musicians are expected to play to play the hits in concert (looking at you, Bob). It’s no accident that, late in life, when Yeats sat down for a 1932 recording of a few select poems, he began with “The Lake Isle of Innisfree.” It’s like Dylan choosing “Blowin’ in the Wind” for his 2021 Ionic recording.

Yeats was reading Thoreau’s Walden around the time he wrote this poem, and you can see that ideal of simplicity and self-reliance transplanted to Irish soil:

I will arise and go now, and go to Innisfree

And a small cabin build there, of clay and wattles made;

Nine bean rows will I have there, a hive for the honey bee,

And live alone in the bee-loud glade.

For much of his young adulthood, Yeats lived primarily in London. This was a common story among itinerant Irish workers of every trade, who found more job opportunities in the imperial capital than were available back home. Kiberd explains this phenomenon in a literary context:

Yeats followed Wilde and Shaw to London in the 1880s, the approved route for an Irishman on the make in England. Once there, however, he grew rapidly depressed at the ease with which London publishers could convert a professional Celt into a mere entertainer, and so he decided to return to Dublin and shift the centre of gravity of Irish culture back to the native capital. (3)

In his memoir Four Years, Yeats recalled his initial inspiration for “The Lake Isle of Innisfree” while strolling through London in 1888:

I had still the ambition, formed in Sligo in my teens, of living in imitation of Thoreau on Innisfree, a little island in Lough Gill, and when walking through Fleet Street, very homesick, I heard a little tinkle of water and saw a fountain in a shop-window which balanced a little ball upon its jet, I began to remember lake water. From the sudden remembrance came my poem “Innisfree,” my first lyric with anything in its rhythm of my own music. (44-45)

Yeats translates this experience lyrically into the stirring final verse of the poem:

I will arise and go now, for always night and day

I hear lake water lapping with low sounds by the shore;

While I stand on the roadway, or on the pavements grey,

I hear it in the deep heart’s core.

We come to realize that the poet is not writing from bucolic Innisfree. He treads the grey urban pavements of an unnamed metropolis, a stranger in a strange land. In another respect, however, he is always in Innisfree because he carries it with him in his heart.

Stuck Inside of London with the Sligo Blues Again

His family’s familiar home turf was “Yeats Country” in Sligo, so the young man could have selected any number of places as his own private Walden Pond. But as a poet, Yeats was wise beyond his 23 years in choosing Innisfree. The name combines the Irish word for island with the English word for free.

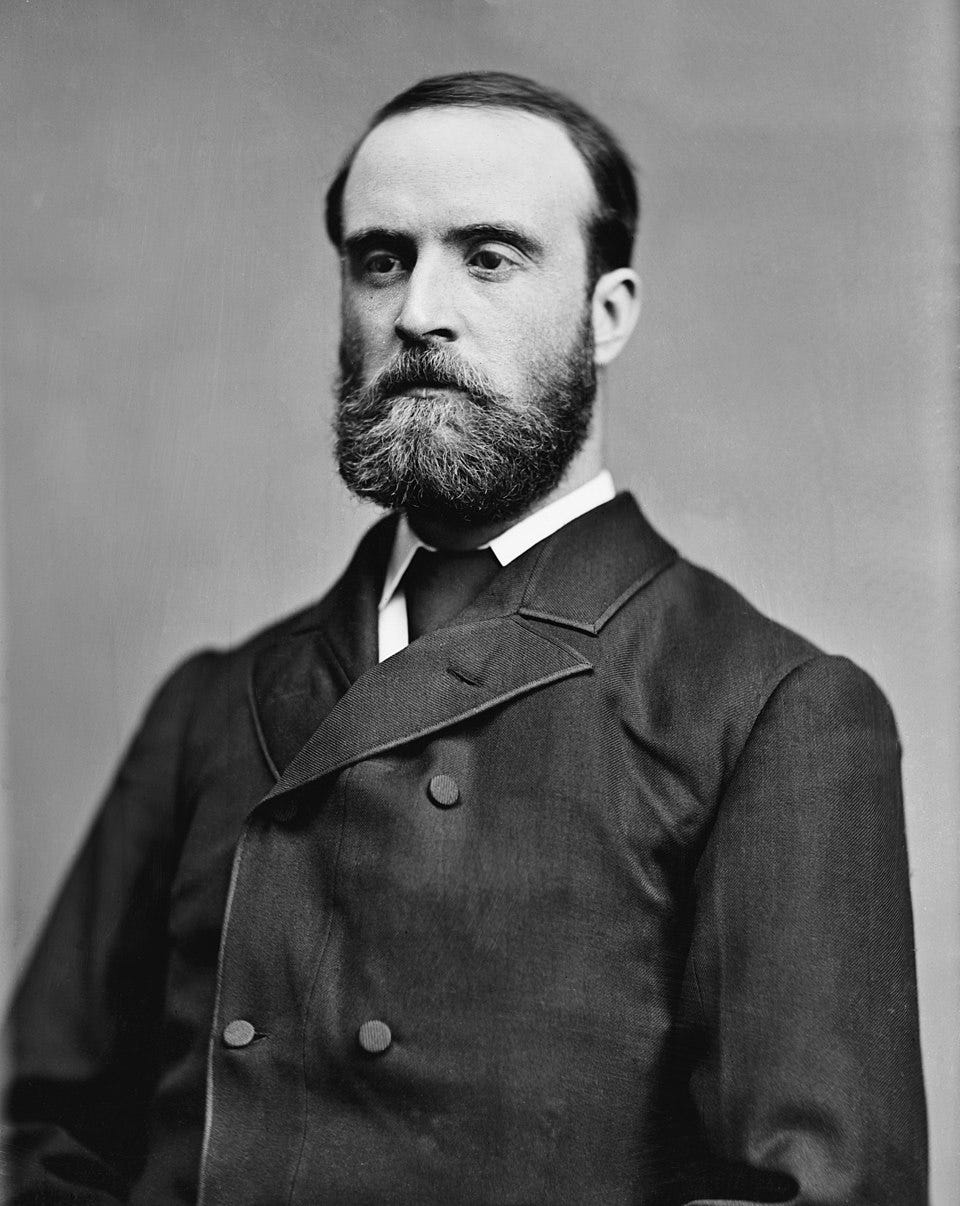

Island + Free = Free Ireland

For hundreds of years, Irish rebels had resisted English rule in Ireland. These uprisings had all been swiftly and ruthlessly squashed by the empire. In the late 19th century, the Irish Parliamentary Party led by Charles Stewart Parnell tried instead to secure some measure of independence through political means.

Just as he was on the brink of passing the Irish Home Rule Bill, however, Parnell was brought down in scandal over an extramarital affair. The so-called “uncrowned king of Ireland” lost his parliamentary support, religious leaders turned against him in disgrace, the home rule campaign collapsed, and Parnell was hounded out of office and into an early grave. Yeats’s generation’s disillusionment after the downfall of Parnell was comparable to Dylan’s generation’s disillusionment after the assassination of President Kennedy.

But whereas Dylan began to recede from political engagement after JFK’s death, Parnell’s death was the spur that prompted WBY to deepen his involvements in Ireland, albeit with cultural rather than political objectives. As Yeats’s pointed out at the beginning of his Nobel Lecture in 1923,

The modern literature of Ireland, and indeed all that stir of thought which prepared for the Anglo-Irish War, began when Parnell fell from power in 1891. A disillusioned and embittered Ireland turned away from parliamentary politics; an event was conceived and the race began, as I think, to be troubled by that event’s long gestation.

Having witnessed the catastrophic failures of both militant and political independence movements, young Irish artists and intellectuals focused their energies instead on a cultural revival. By restoring pride in a distinct Irish identity, and by renouncing denigrating influences from England, Yeats and his peers strategically planted the seedbed for future independence.

After many generations of subjugation, the Irish people needed to imagine their way back to freedom before they could ever realistically expect to achieve independence militarily or politically. “The Lake Isle of Innisfree” is Yeats’s most beloved manifestation of that vision. He imagines Free Ireland into existence through an act of artistic will power and sustains it in the deep heart’s core.

We can also hear him accepting personal responsibility for participating in the freedom struggle. There is a recurring phrase in “The Lake Isle of Innisfree”—“I will arise and go now”—which is taken directly from the prodigal son parable (Luke 15:18). Yeats was young when he left home, but he recognized that the time had come to return to Ireland, body and soul.

Around the turn of the century, Yeats began to spend more time in Ireland, particularly after he co-founded The Abbey Theatre in Dublin and became its first artistic director. There he began working in earnest to transform the imaginary Free Ireland into reality. He and his generation eventually succeeded, but it wasn’t easy and the casualties were severe. When the dust settled, the free nation Yeats got wasn’t the one he expected or thought he was fighting for. But that’s another story which we’ll save for the next installment.

Works Cited

Dylan, Bob. 2015 MusiCares Speech. Rpt. Christy Moore, https://www.christymoore.com/bob-dylans-musicares-acceptance-speech-well-worth-read/.

---. Chronicles, Volume One. Simon & Schuster, 2004.

---. Nobel Prize Lecture. Nobel Prize (5 June 2017), https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/literature/2016/dylan/lecture/.

Foster, R. F. W. B. Yeats, A Life: Vol. 1, The Apprentice Mage. Oxford University Press, 1997.

Hentoff, Nat. “A Talk with Joan Baez.” Hifi/Stereo Review (November 1963), 39-42, https://dc.library.northwestern.edu/items/5e100598-ece1-493c-96af-6cf535cfd900.

Kiberd, Declan. Inventing Ireland: The Literature of the Modern Nation. Harvard University Press, 1995.

Marqusee, Mike. Wicked Messenger: Bob Dylan and the 1960s. New York: Seven Stories Press, 2005.

No Direction Home. Directed by Martin Scorsese. Paramount Pictures, 2005.

Pareles, Jon. “A Wiser Voice Blowin’ in the Autumn Wind.” New York Times (28 September 1997). https://www.nytimes.com/1997/09/28/arts/pop-jazz-a-wiser-voice-blowin-in-the-autumn-wind.html. Accessed 26 May 2020.

Shelton, Robert. No Direction Home: The Life and Music of Bob Dylan. New York: Beech Tree Books, 1986.

Wald, Elijah. Dylan Goes Electric!: Newport, Seeger, Dylan, and the Night that Split the Sixties. New York: Dey St., 2015.

Yeats, W. B. The Celtic Twilight (1893). A. H. Bullen, 1902.

---. Four Years (1921). Max Bollinger, 2019.

---. “Hopes and Fears for Irish Literature” (1892), https://studylib.net/doc/8603650/hopes-and-fears-for-irish-literature-1892-doc.

---. “The Lake Isle of Innisfree” (1888). The Collected Poems of W. B. Yeats. Ed. Richard J. Finneran. Simon & Schuster, 1983, 39.

---. “A Literary Causerie: The Message of the Folk-lorist” (1893), https://www.lyriktheorie.uni-wuppertal.de/texte/1893_yeats1.html#text.

---. “The Nobel Prize Lecture: The Irish Dramatic Movement” (15 December 1923). The Nobel Prize, https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/literature/1923/yeats/lecture/.

---. “The Stolen Child” (1886). The Collected Poems of W. B. Yeats. Ed. Richard J. Finneran. Simon & Schuster, 1983, 18-19.

Thank you Grayley. Such a deep read and I will look forward to more.

This was gorgeous Graley! The Dylan world is so much richer for your ideas and how you write them. I'm going to go read some Yeats now!