In the first installment of this two-part series, we explored songs by Bob Dylan and stories by Shirley Jackson derived from the demon lover ballad tradition. Last time we focused on Dylan’s “House Carpenter,” “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue,” and “Mr. Tambourine Man,” putting those songs in conversation with Jackson’s “The Dæmon Lover.” In this second installment, we’re going to swing from a different branch of the same family tree. A black branch with blood that keeps dripping.

Dylan covered “Blackjack Davey” on his 1992 covers album Good as I Been to You, another song featuring a woman who leaves her home behind to follow a mysterious dark figure. This demon lover ballad helped inspire one of Dylan’s most interesting responses to the tradition, “Man in the Long Black Coat” from Oh Mercy (1989).

Multiple stories from Shirley Jackson’s The Lottery or, The Adventures of James Harris are inspired by “James Harris (The Dæmon Lover)” (Child No. 243). This time we’ll turn our attention to “Elizabeth.” On the surface, this is the tale of a dissatisfied literary agent who dreams of abandoning her stagnant life and running off with a writer named (of course) James Harris. On a deeper level, however, Jackson interweaves subtle references to black magic throughout, turning “Elizabeth” into a modern metafiction about witchcraft in the context of 1940s America.

As a bonus track, we’ll close with a song by Connie Converse. Her all-too-brief musical career coincided with Jackson’s heyday in the forties and fifties, and immediately preceded Dylan’s arrival on the Greenwich Village folk scene in the early sixties. She toiled in obscurity, but her work has recently been attracting overdue attention. She dipped her bucket into the same musical wellspring of inspiration as Jackson and Dylan, dredging up a brilliant satire of the demon lover myth called “The Witch and the Wizard.”

“Blackjack Davey”

“The Gypsy Laddie” is listed as Child Ballad No. 200 in English and Scottish Popular Ballads. Early versions of the song referred to the dashing lover as Johnny Faa. According to Child, “Johnny Faa was a prominent and frequent name among the gypsies. Johnnë Faw’s right and title as lord and earl of Little Egypt were recognized by James V in 1540. But in the next year Egyptians were ordered to quit the realm within thirty days on pain of death. The gypsies were formally expelled from Scotland by act of Parliament in 1609” (200). Child cites multiple historical figures by the name of Johnny Faa who were executed for various crimes. However, the dean of ballad scholars concludes that “The Gyspy Laddie” is about an archetypal rogue more than an actual person: “Johnny Faa acquired popular fame, and became a personage to whom any adventure might plausibly be imputed” (200).

Later versions go by different titles, including “The Raggle Taggle Gypsy,” “Gypsy Davy,” and “Black Jack David.” Dylan could have picked up the tune from Woody Guthrie, The Carter Family, Pete Seeger, or John Jacob Niles. The song was also in the repertoire of his contemporaries on the folk circuit, including The New Lost City Ramblers, Jean Ritchie, and Barbara Dane. After Dylan covered “Blackjack Davey” in 1992, other rootsy artists gave it a shot. My favorites are by The White Stripes, Dave Alvin, and Hurray for the Riff Raff.

“Blackjack Davey” makes for an interesting companion piece alongside “House Carpenter” in the demon lover tradition. Both feature a seductive man who invites a woman to escape with him. Black Jack Davey—for some reason, Dylan combines the first two names in the title, but not in the published lyrics—is a classic silver-tongued devil:

Black Jack Davey come a-ridin’ on back

A-whistlin’ loud and merry

Made the woods around him ring

And he charmed the heart of a lady

Charmed the heart of a lady

Who could resist? Not this “lady,” who is actually only fifteen years old, even though she’s already married and has a child. She rides away with him, on a horse rather than a ship, and here Child Ballads Nos. 243 and 200 diverge significantly.

In “House Carpenter,” the woman discovers that James Harris is a ghost, a demon, or the devil himself. She drowns in the sea and presumably spends eternity in hell as punishment for her sins. Not so in “Blackjack Davey.” As soon as the husband, initially referred to as “the boss,” learns of his wife’s departure, he gallops off to retrieve his lost property. He catches up and confronts her, accusing her of abandoning her duties as wife and mother. She stands her ground:

“Well, I’ll forsake my house and home

And I’ll forsake my baby

I’ll forsake my husband too

For the love of Black Jack Davey

Love my Black Jack Davey”

The older Scottish “The Gypsy Laddie” concludes with the wife’s return and the gypsy’s punishment. But the American version of “Blackjack Davey” sung by Dylan ends with the new couple lying contentedly in each other’s arms:

“Last night I slept in a feather bed

Between my husband and baby

Tonight I lay on the river banks

In the arms of Black Jack Davey

Love my Black Jack Davey”

In the sultry voice of Black Jack Bobby, there can be no doubt that this runaway bride is far better off sleeping on the ground with her demon lover than she ever was sequestered in the home of her boss/husband.

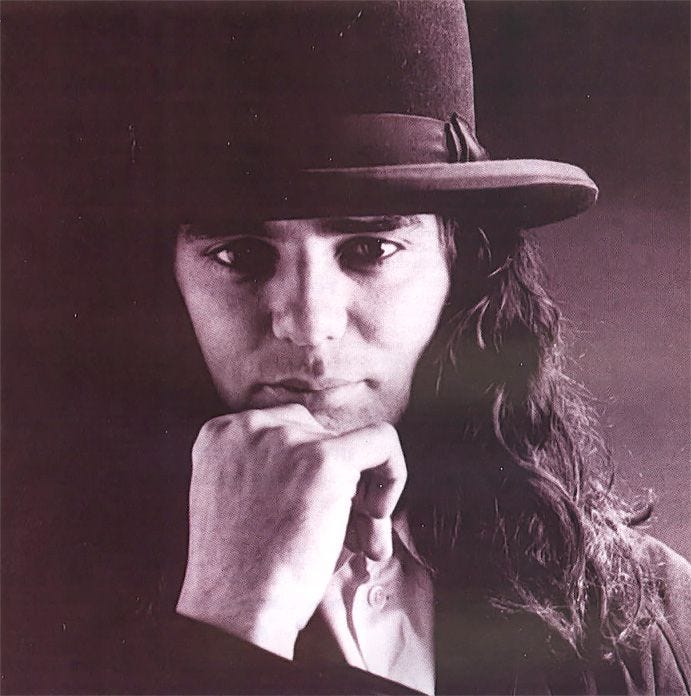

The most interesting interpretation of this song that I’ve found comes from Stanley Edgar Hyman. You will recall from the previous post that Hyman was the husband of Shirley Jackson. As a professor at Bennington, he taught a course for many years called “Myth, Ritual, and Literature,” with an eclectic syllabus that included folk songs. He also wrote a chapter on the Child Ballads for his collection The Promised End: Essays and Reviews, 1942-1962. Hyman argues that historical approaches to these ballads are misguided. To illustrate his point, he offers a case study of “The Gypsy Laddie.” He believes that the ballad is rooted in ancient agricultural rituals involving the change of seasons:

We know that the ritual combat between the forces of summer and winter was performed in many parts of the world, in many different guises, and has survived in England in such forms as Mummers Plays, Morris and Sword Dances, etc. Frazer reports a typical Manx May Day ceremony in which the two sides battled for their respective queens. All the evidence insists that the origin of “The Gypsy Laddie” was such a spring ritual battle, at which the lady, or Persephone figure, representing life and vegetation, who had been seized by the dark men of winter in the fall ceremonies and ostensibly held captive by them underground, was won back from them by the forces of summer. (253)

Like the myth of Persephone abducted by Hades and forced to spend part of the year confined to the underworld, the ballad once enacted the transition from summer to winter, from fertile to fallow, from life to death. How did it transform from an agricultural ritual to a romance about gypsy lovers? Hyman speculates:

As the rite died out and its meaning became obscured, the libretto continued as a ballad, and by a gradual rationalizing the dark men of winter became wife-stealing gypsies, the light men of summer became the lord’s loyal retainers, and, by processes suggested above, the characters gradually acquired a locality and an identity; the sequence going from rite to drama, drama to narrative song, narrative song to pseudo-historical account. (253)

Hyman makes a compelling case for hearing these old chants as “ritual in origin, dramatic in structure, and magical in function” (258). Ritual – Dramatic – Magical. Dylan’s songs and Jackson’s stories about demon lovers dwell within this mythic triangulation.

Dylan’s “Man in the Long Black Coat”

One of Dylan’s most interesting songs descended from both the “House Carpenter” and “Blackjack Davey” branches of the demon lover family tree is “Man in the Long Black Coat.” He wrote it in 1989 during the tempestuous recording sessions for Oh Mercy in New Orleans. At the time, he was routinely clashing with his own man in black, producer Daniel Lanois. Dylan’s first description of Lanois in Chronicles makes him sound straight from central casting as the villain: “He was noir all the way—dark sombrero, black britches, high boots, slip-on gloves—all shadow and silhouette—dimmed out, a black prince from the black hills” (177).

The New Orleans setting also seeps into the recording sessions, with spectral presences and spirits of the dead haunting “Man in the Long Black Coat.” According to Dylan,

The first thing you notice about New Orleans are the burying grounds—the cemeteries—and they’re a cold proposition, one of the best things there are here. Going by, you try to be as quiet as possible, better to let them sleep. Greek, Roman, sepulchers—palatial mausoleums made to order, phantomesque, signs and symbols of hidden decay—ghosts of women and men who have sinned and who’ve died and are now living in tombs. The past doesn’t pass away so quickly here. You could be dead a long time. The ghosts race towards the light, you can almost hear their heavy breathing—spirits, all determined to get somewhere” (Chronicles 179-80)

The scene is set for an epic battle between light and darkness, life and death. And that’s exactly how Dylan describes laying down the tracks for “Man in the Long Black Coat”:

Before the lyrics even came in, you knew that the fight was on. This is Lanois-land and couldn’t have been coming from anywhere else. The lyrics try to tell you about someone whose body doesn’t belong to him. Someone who loved life but cannot live, and it rankles his soul that others should be able to live. (Chronicles 216)

Lanois establishes a spooky sonic atmosphere and Dylan animates the tale with his best ghost-story voice. The lyrical perspective appears to be that of the jilted husband left behind:

Crickets are chirpin’, the water is high

There’s a soft cotton dress on the line hangin’ dry

Window wide open, African trees

Bent over backwards from a hurricane breeze

Not a word of goodbye, not even a note

She gone with the man in the long black coat

In my commentary on Dylan’s performance of “Man in the Long Black Coat” at NKU in November 2010, I suggested that the song adopts the house carpenter’s perspective from the old demon lover ballad. Andrew Muir later told me that this interpretation had actually been around since 1989. In Dylan’s Daemon Lover: The Tangled Tale of a 450-Year Old Pop Ballad, Clinton Heylin credits Andy with pointing him toward this same reading from Chris Morris:

The other connection that, frankly, had simply not occurred to me came from a review of Oh Mercy in the L.A. Reader in September 1989, and was recently sent to me by Homer, the slut [Andrew Muir’s fanzine]. In it, one Chris Morris refers to “Man in the Long Black Coat” as, “a chilling song-story about a diabolical stranger that takes its inspiration from centuries-old English ballads about the Demon Lover.” And he is right. “Man in the Long Black Coat” is exactly the song that would have been written by the house-carpenter when he found his wife had left with a mysterious stranger, a late twentieth-century “James Harris.” (168)

Whether he goes by the name James Harris or his inky-cloaked cousin Black Jack Davey, his magnetic attraction is irresistible for the wife: “She never said nothing, there was nothing she wrote / She went with the man in the long black coat.”

Laura Tenschert offers a wonderful analysis of “Man in the Long Black Coat,” concentrating on the woman’s perspective in the song. The young bride is stuck:

The town that the woman leaves behind is described as this place of stasis. The traces of a hurricane and past storms seems not to have changed anything. The song literally opens with crickets, ya know? That’s how much is going on. And in the last verse there is somebody literally beating a dead horse. How much more can you evoke repetition and things not changing.

When the mysterious stranger arrives, she recognizes an opportunity to escape and seizes the day. As Laura puts it, “I think this is a song about decisions. It’s about the decisions that we make and, more importantly, the decisions that we don’t make. The woman in the song made the decision to break out of the stasis and to take initiative.”

Laura’s interpretation of “Man in the Long Black Coat” situates it squarely within Dylan’s genealogy of demon lovers. The original ballads often served as cautionary tales warning women against betraying their domestic duties; but Dylan’s songs tug in the other direction, insisting that the promise of freedom is worth risking everything. In the bridge the singer reflects,

There are no mistakes in life some people say

And it’s true sometimes, you can see it that way

People don’t live or die, people just float

She went with the man in the long black coat

I completely agree with Laura’s carpe diem reading of these lines:

The woman’s decision in the song is to no longer float, but to take a step to live. And of course there are mistakes, the song seems to say, but what if the worst mistake of all is to not make any decision and to just stay stuck? The woman’s decision to take initiative is despite the possibility that it’s a potential mistake.

Shirley Jackson places her women characters at similar crossroads. Unfortunately, the demon lovers they meet (or imagine) are unreliable guides toward freedom. Furthermore, the cultural constraints holding back her mid-century American women prove much harder to resist. It takes special powers to counteract these forces. It takes the black magic of a witch.

Black Magic Women

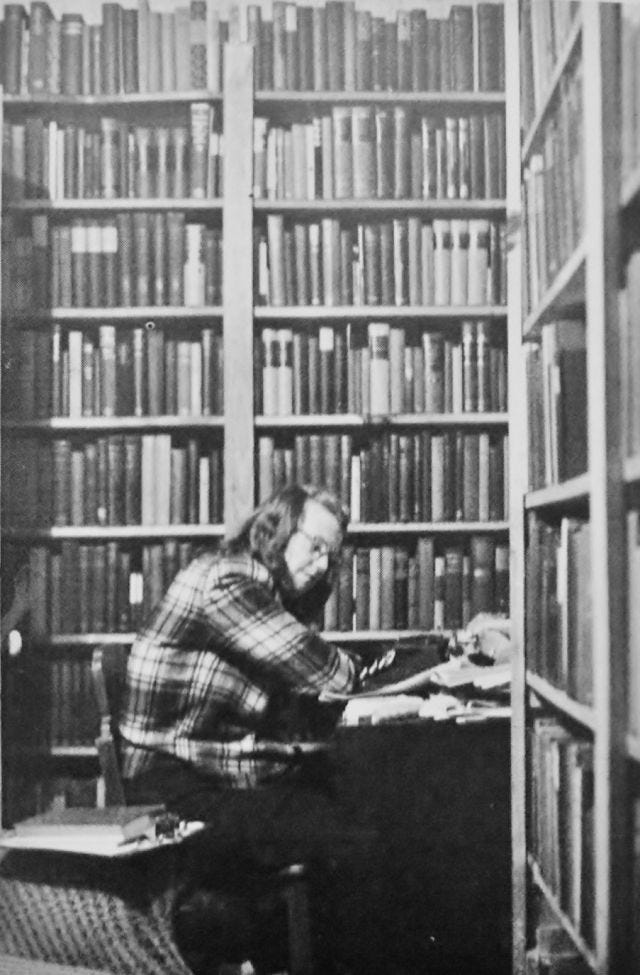

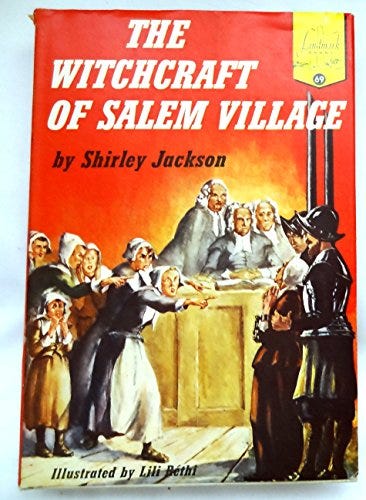

Jackson’s interest in magic and witchcraft was deep and sustained. The biographical sketch accompanying her first novel proclaims: “She is an authority on witchcraft and magic, has a remarkable private library of works in English on the subject, and is perhaps the only contemporary writer who is a practicing amateur witch, specializing in small-scale black magic and fortune-telling with a Tarot deck” (217). In 1956, Jackson published a non-fiction book aimed at young adults titled The Witchcraft of Salem Village. Biographer Ruth Franklin notes,

The witch trials, as she demonstrates, did not come out of nowhere: they were the product of the specific circumstances of the Massachusetts Bay Colony in general and Salem Village in particular. Likewise, the women who were targeted were not accidental victims, but social outcasts or others outside the mainstream. Her emphasis on these themes, novel at the time, anticipates a number of more recent treatments of the witch trials. (357)

In a later edition of the book, Jackson added a postscript letter to readers. She clearly had Joseph McCarthy’s Communist “witch hunts” in mind, but also the perennial persistence of misogyny. Jackson counseled,

The people of Salem hanged and tortured their neighbors from a deep conviction that they were right to do so. Some of our own deepest convictions may be as false. We might say that we have far more to be afraid of today than the people of Salem ever dreamed of, but that would not really be true. We have exactly the same thing to be afraid of—the demon in men’s minds which prompts hatred and anger and fear, an irrational demon which shows a different face to every generation, but never gives up in his fight to win over the world. (qtd. Franklin 361)

For centuries, women have been accused, demonized, and executed for witchcraft. In Witchcraft: A History in Thirteen Trials, Marion Gibson traces this legacy from Helena Scheuberin in 15th-century Austria to Stormy Daniels in 21st-century America. As Carol Karlsen argues in The Devil in the Shape of a Woman: Witchcraft in Colonial New England, women singled out for persecution tended to be rebels, “at best aggressive and abrasive, at worst ill-tempered, quarrelsome, and spiteful. They are almost always described as deviants—disorderly women who failed to, or refused to, abide by the behavioral norms of their society” (118).

Jackson seeks to recuperate witchcraft, taking a practice historically weaponized against women and refashioning it as a shield against degradation, exploitation, and oppression. As Ruth Franklin observes in Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life,

Witchcraft, whether she practiced it or simply studied it, was important to Jackson for what it symbolized: female strength and potency. The witchcraft chronicles she treasured […] are stories of powerful women: women who defy social norms, women who get what they desire, women who can channel the power of the devil himself. (261)

When Jackson was assembling her story collection The Lottery, her publisher suggested the subtitle Notes from a Modern Book of Witchcraft. The author opted for a demon lover allusion instead, The Adventures of James Harris; but she still inserted regular witch references, opening each section with epigraphs from demonologist Joseph Glanvill’s Saducismus Triumphatus: or, Full and Plain Evidence Concerning Witches and Apparitions (1681).

For example, the second section of The Lottery opens with an epigraph from the confessions of Margaret Jackson, an accused witch who shared Shirley’s last name. The passage from Glanvill describes intimate meetings with the devil, who assumed the form of a Black Man:

the black Man came to her, and she did give up herself unto the black Man, from the top of her head to the sole of her foot; and this was after the Declarant’s renouncing of her Baptism […]. In the night-time, when she awaked, she found a Man to be in bed with her, whom she supposed to be her Husband; though her Husband had been dead twenty years, or thereby, and the Man immediately disappeared: And declares, That this Man who disappeared was the Devil. (qtd. Jackson 143)

Puritans conceived of the devil in similar terms. In The Gothic Literature and History of New England, Faye Ringel explains,

The earliest English settlers of New England feared a Black Man in the forests. Whether visualized as an Indian, an African, or a specter of Satan, this figure haunts the history and literature of the region. The Puritans brought the belief that the devil ruled the wilderness from the Old World into forests of the new. Fear of this Black Man, symbolic or literal, can be found in Cotton Mather, whose witch cult’s devil is Black; in Hawthorne’s “Young Goodman Brown” (1835), which recounts one such forest meeting; and in Stephen King’s homage to Hawthorne, “The Man in the Black Suit.” (5)

Dylan’s seductive “Man in the Long Black Coat” is kith and kin to this Black Man lineage, as are the various James Harris figures in The Lottery.

Jackson’s “Elizabeth”

Jackson weds her interests in black magic, witchcraft, and demon lovers to great effect in the story “Elizabeth.” The title character is Elizabeth Style, a literary agent in the struggling firm of Robert Shax, her boss and lover. She gets upset when Robbie hires an attractive young secretary, Daphne Hill, whom she ends up firing in a pique of jealousy. Realizing that she has been stuck for eleven years in a dead-end job and loveless affair, Elizabeth invites a former client, the writer James Harris, over to her apartment. By the end of the story, however, she is no closer to escaping than she was at the start. Even from this brief summary, you can doubtlessly hear the echoes of “House Carpenter” and “Blackjack Davey” and see Jackson’s revisionist twists on the demon lover theme.

But wait. There’s more.

It turns out that Elizabeth Style was the name of an alleged witch in Glanvill’s Saducismus Triumphatus. The secretary that Elizabeth clashes with is named after Elizabeth Hill, a girl the accused witch supposedly tortured with black magic. Robert Shax’s surname is the same as a legendary demon with great power, a Grand Marquis of Hell. [Jackson kept black cats as pets and named a series of them Shax (Franklin 188).]

In Jackson’s story, Elizabeth calls her partner Robbie, derived from Robin, the name Elizabeth Style used for the devil. According to her confession, reproduced by Glanvill,

She confessed, That the Devil about 10 years since, appeared to her in the shape of a handsome Man, and after of a Black-Dog; that he promised her Money, and that she should Live gallantly, and have the Pleasure of the World for 12 Years, if she would with her Blood sign his Paper, which was to give her Soul to him, and observe his Laws, and that he might suck her Blood. […] That when she hath a desire to do harm, she calls the Spirit by the Name of Robin, to whom when he appeareth, she useth these words, O Satan give me my purpose! (Glanvill 73)

Style’s confession mentions regular meetings in the woods with “the Man in black,” where she and other witches would drink, feast, dance, and make merry with the devil. Interestingly, she also describes her dark master as a musician: “The Man in black, sometimes plays on a Pipe or Cittern, and the Company dance” (Glanvill 75).

Remember that the singer in “Mr. Tambourine Man” follows the sound of music into the woods and willingly surrenders to the musician’s magic: “cast your dancing spell my way / I promise to go under it.” Also remember that the woman in “Man in the Long Black Coat” seals her bond with the mystery man through dance:

Somebody seen him hanging around

At the old dance hall on the outskirts of town

He looked into her eyes when she stopped him to ask

If he wanted to dance, he had a face like a mask

Demon lovers aren’t merely characters within ballads. The devil is also adept at using music, song, and dance as bait to trap his victims.

Or at least that’s what preachers, demonologists, and witch hunters would have us believe. But an alternative possibility is that dancing to the devil’s music is a form of rebellious liberation. That’s what parents thought when Dylan’s generation started wop-bop-a-loo-bopping to early rock ’n’ roll. And, as Laura argues in her commentary on “Man in the Long Black Coat,” “The invitation to dance was the woman signaling a willingness for change, a breaking of the spell of stasis, and the newfound freedom that comes in the form of a dance.” Maybe this same impulse is what sent 17th-century Elizabeth Style out into the forest.

Unfortunately, the dance card is empty for Jackson’s 20th-century Elizabeth Style. Her disappointing life is governed by mind-numbing habit and soul-shrinking routine. Jackson opens her story like The Wizard of Oz in reverse, beginning with the technicolor vividness of Elizabeth’s dreams before rudely returning her to the black-and-white squalor of her waking life.

Just before the alarm went off she was lying in a hot sunny garden, with green lawns around her and stretching as far as she could see. The bell of the clock was an annoyance, a warning which had to be reckoned with; she moved uneasily in the hot sun and knew she was awake. When she opened her eyes and it was raining and she saw the white outline of the window against the grey sky, she tried to turn over and bury her face in the green grass, but it was morning and habit was lifting her up and dragging her away into the rainy dull day. (149, emphasis added)

“Habit is a great deadener,” laments Vladimir in Waiting for Godot (84). Elizabeth is most alive when she is stretching in the warm grass of her dreams, echoing “where the green grass grows / On the shores of sunny Italy” from “House Carpenter,” or the riverbank snuggle in “Blackjack Davey.” But then the alarm clock drags her away from her dream idyll and sends her trudging through another lap of daily routine.

The day had fallen into its routine; after the first involuntary rebellion against every day’s alarm she subsided regularly into the shower, make-up, dress, breakfast schedule which would take her through the beginning of the day and out into the morning where she could forget the green grass and the hot sun and begin to look forward to dinner and the evening. (149, emphasis added)

Work sucks, and everyone prefers to linger in bed on a rainy day. But at least she has a love affair to spice up her life, right? Wrong. All the spark is gone from Elizabeth’s relationship with Robert. They go through the same lifeless routines every day at work, then eat the same meals at the usual restaurant. There was a time when these rendezvous were thrilling, hopeful, and romantic. They would hold hands across the table and enthusiastically make ambitious plans. Now they’re just going through the motions out of habit. At lunch that day, she considers doing or saying something different, but she lets the moment pass as always:

Elizabeth watched him: this is Robbie, she was thinking, I know what he’s going to do and what he’s going to say and what tie he’s going to wear every day in the week, and for eleven years I have known these things and for eleven years I have been wondering how to say things to make him understand. (166-67)

In Laura’s reading of “Man in the Long Black Coat,” the decisive turning point comes when the woman invites the dark stranger to dance. It’s important to note that, in Dylan’s demon lover song, the man doesn’t abduct the woman: she makes the first move. This bold gesture, taking the initiative to break the torpor of habitual routine, is something that Jackson’s Elizabeth can never bring herself to do. She remains stuck.

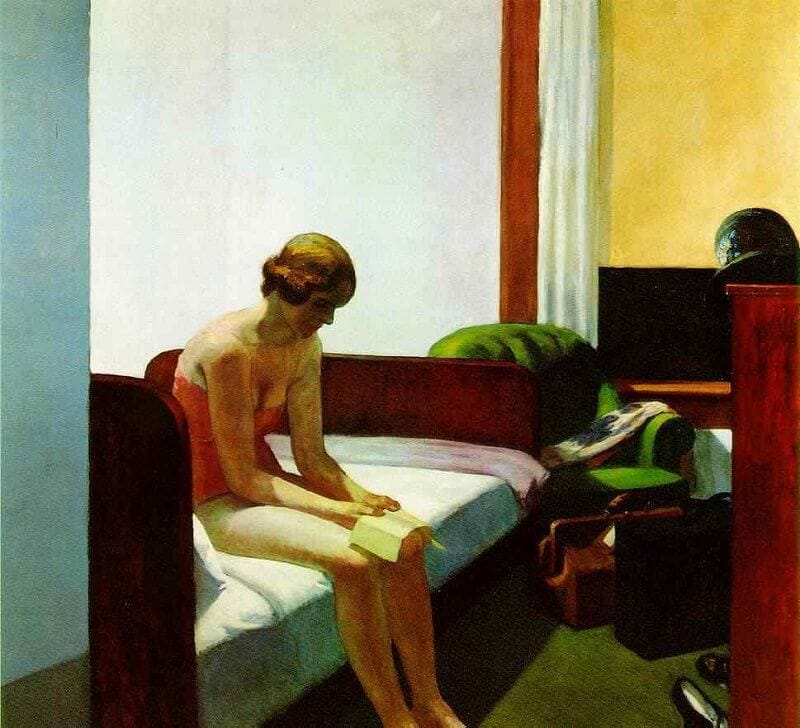

Late in the story, Jackson provides a particularly poignant image of loneliness. Elizabeth returns home, and Jackson paints a verbal portrait like something out of Edward Hopper, a modern still-life of quiet despair:

The appearance of her room shocked her; she had forgotten her hurried departure this morning and the way she had left things around; also, the apartment was created and planned for Elizabeth; that is, the hurried departure every morning of a rather unhappy and desperate young woman with little or no ability to make things gracious, the lonely ugly evenings in one chair with one book and one ashtray, the nights spent dreaming of hot grass and heavy sunlight. (188)

The only thing that gets Elizabeth through the day is the prospect of going back to bed and escaping into her dreams.

But Jackson models her protagonist after a witch for a reason. She invests Elizabeth with a magical power for exerting some control over her tedious life: imagination. Like her author, the protagonist is a daydreaming writer with the shape-shifting ability to alter reality. As Shirley Jackson herself attested, “I like writing fiction better than anything, because just being a writer of fictions gives you an absolutely unassailable protection against reality; nothing is ever seen clearly or starkly, but always through a thin veil of words” (261).

As I mentioned in the previous installment, the reader of Jackson’s “The Daemon Lover” is never entirely sure whether James Harris really exists or is just a figment of the imagination. In that case, the phantom seems a symptom of the protagonist’s delusions. But the case is different in “Elizabeth,” where Jackson’s literary avatar exercises conscious creative control over her fantasies, inventing scenes to combat ennui, punish her adversaries, and inject drama into her daily routine.

The first hint that we’re reading metafiction comes on Elizabeth’s way to work. She stops by her neighborhood drugstore and orders an orange juice, exchanging polite, meaningless words with the soda jerk Tommy. Knowing that she’s a literary agent, he tells her that he’s just finished writing a play. “Funny thing, she thought, a clerk in a drugstore, he gets up in the morning and eats and walks around and writes a play just like it was real, just like the rest of us, like me” (153, emphasis added). Just like it was real. Writers invent alternate realities, populate them with plausible characters, and give them interesting things to say and do. It’s what Tommy did in writing his play, it’s what Jackson did in writing “Elizabeth,” and it’s what Elizabeth proceeds to do over the course of the story.

Tellingly, Elizabeth is the head of the fiction department. At work that morning, while reading a manuscript submitted by a potential client, she gets an idea for her own work of fiction: “She opened the notebook to a blank page, copied out a paragraph from the manuscript, thinking, I can switch that around and make it a woman instead of a man; and she made another note, ‘make W., use any name but Helen,’ which was the name of the woman in the story” (161). She plans to take an idea from a previous source and then switch around some details around to make it her own. Of course, that is exactly what Jackson does in appropriating and adapting demon lover ballads and Saducismus Triumphatus to create “Elizabeth.”

Immediately after Elizabeth gets an idea for a new work of fiction featuring a woman character, lo and behold, Daphne Hill enters the office and the story for the first time. Although Jackson never spells it out, I suspect that Daphne is Elizabeth’s invention. She improvises a scene with an imaginary character “just like it was real.”

Daphne is tailor-made to serve as an alter-ego. Before Elizabeth came into work “this morning she thought, as she had thought nearly every morning standing in front of her mirror, I wish I’d been a blonde; never realizing quite that it was because there were thin hints of grey in her hair” (150). Mirror, mirror, on the wall, who’s the fairest of them all? Elizabeth imagines a rival who is her polar opposite—young, blonde, attractive, free—a sexy substitute whom she is expected to train as her replacement, in Robbie’s office and in his bed. O Satan give me my purpose!

She invents an arch-enemy for the purpose of destroying her. According to my metafictional reading, the events that follow—Elizabeth’s debate with Robbie over lunch for hiring the new secretary behind her back, the catty clashes between Elizabeth and Daphne in the office, Elizabeth’s humiliation of her rival culminating in Daphne’s dismissal—are imaginary scenes devised and enacted by Elizabeth, embedded within Jackson’s larger frame story.

And what about the demon lover James Harris? His picture hangs on the office wall as a constant reminder of unfulfilled promise. We read about “an autographed photograph of one of the few reasonably successful writers the firm had handled. The photograph was signed, ‘To Bob, with deepest gratitude, Jim’” (157-58). I suspect that this photo triggers another daydream reverie. Elizabeth imagines taking the initiative, phoning Jim Harris, and arranging a date. My theory is that this entire exchange took place inside her imagination. She is only capable of casting a spell and conjuring a demon lover in her mind.

In fact, as with Jackson’s “The Daemon Lover,” James Harris never actually makes an appearance in “Elizabeth.” The story closes with a fantasy about a dark stranger who might sweep her away to a better life. But the reappearance of the warm grass at the end implies that he is no more than a fantasy figure, Elizabeth’s Mr. Tambourine Man or Man in the Long Black Coat, guiding her to dreamland:

To get a new apartment she needed more money, she needed a new job, and Jim Harris would have to help her, tonight would be only the first of many exciting dinners together, building into a lovely friendship that would get her a job and a sunny apartment; while she was planning her new life she forgot Jim Harris, his heavy face, his thin voice; he was a stranger, a gallant dark man with knowing eyes who watched her across a room, he was someone who loved her, he was a quiet troubled man who needed sunlight, a warm garden, green lawns . . . .” (191)

Keep dreaming, Elizabeth. The story ends exactly where it began. Like the damned in Dante’s Inferno, Elizabeth revolves endlessly around her circle of hell, rotating from empty home to demoralizing job and back, day after day, year after year. She has talent, but no viable outlet for self-expression. She is a witch with a broken wand. Metafiction is an appropriate medium for Elizabeth because she is a character passively stuck in a story written by someone else.

Elizabeth Style reminds me of Judith Shakespeare in Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own. Woolf attempts to recuperate the forgotten lineage of women writers who never received an opportunity to have their voices heard. Woolf asserts that whenever

one reads of a witch being ducked, of a woman possessed by devils, of a wise woman selling herbs, or even of a very remarkable man who had a mother, then I think we are on the track of a lost novelist, a suppressed poet, of some mute and inglorious Jane Austen, some Emily Brontë who dashed her brains out on the moor or mopped and mowed about the highways crazed with the torture that her gift had put her to. I would venture to guess that Anon, who wrote so many poems without signing them was often a woman. (74)

The patron saint of suppressed women writers is Judith Shakespeare, a hypothetical sister who possessed all of William Shakespeare’s talent but none of his opportunity. Woolf believes that such a woman would almost certainly be driven mad. She argues that

any woman born with a great gift in the sixteenth century would certainly have gone crazed, shot herself, or ended her days in some lonely cottage outside the village, half witch, half wizard, feared and mocked at. For it needs little skill in psychology to be sure that a highly gifted girl who had tried to use her gift for poetry would have been so thwarted and hindered by other people, so tortured and pulled asunder by her own contrary instincts, that she must have lost her health and sanity to a certainty. (74-75)

Shirley Jackson conducts a similar experiment in “Elizabeth.” She imagines a modern American woman, half witch and half writer, and takes us through a day in her life. Elizabeth summons all the imaginative powers at her disposal, but it gets her nowhere. Elizabeth Style has no better chance of fulfilling her dreams in 1940s America than her namesake had in the seventeenth century, or her forebear Judith Shakespeare had in the sixteenth century. Sadly, Woolf didn’t fare any better, filling her pockets with stones and drowning herself in the River Ouse in 1941. Jackson’s protagonist doesn’t go insane or die, but she certainly doesn’t enjoy a happy ending. Elizabeth has a (shabby) room of her own and a (meager) salary, but all it gets her is a place to lay her head and dream about a demon lover who never arrives.

Bonus Track: Converse’s “The Witch and the Wizard”

What would have happened if the demon lover had arrived? To play out that scenario, let’s turn to Connie Converse. Get this: “Connie” was a nickname for Elizabeth Eaton Converse. Elizabeth!

She was born in New Hampshire in 1924. She won a four-year scholarship to Mount Holyoke College, but dropped out after two years and moved to New York City. She wrote and recorded her own songs, as well as painting, drawing cartoons, and writing children’s books. She tried to make it as a professional musician but never found success. Finally, she left NYC in 1960, moving to Ann Arbor, Michigan, to be closer to her brother and his family. In August 1974, at the age of 50, she wrote several goodbye letters and disappeared. She has never been heard from since. Add Connie Converse’s name alongside Judith Shakespeare in the roll call of women geniuses discouraged into obscurity, depression, and an early grave.

I first learned about her from Howard Fishman’s 2023 biography To Anyone Who Ever Asks: The Life, Music, and Mystery of Connie Converse. In 2024, Sophie Abramowitz, Sarah Bachman, and Emily Hilliard launched their podcast The Female Bob Dylan with an inaugural episode on Connie Converse. Laura Tenschert drew my attention to this podcast when she interviewed the trio for Definitely Dylan. Along with these sources, I also highly recommend watching Andrea Kannes’s We Lived Alone: The Connie Converse Documentary on YouTube.

Converse’s song “The Witch and the Wizard” makes for a fascinating sequel to “Elizabeth” by picking up the demon lover trope where Jackson leaves off. In Converse’s song, the witch actually manages to run away with her demon lover. Unlike the cautionary tale in “House Carpenter,” the woman survives in “The Witch and the Wizard” and begins a new life. Be careful what you wish for, warns Converse.

A witch there was, and a wizard as well

Moved into a rose-covered cottage in hell

A rose-covered cottage in hell

The relationship is built upon lies because neither partner knows the other’s true nature:

The wizard in spite of his wizardly eyes

Didn’t know he had married a witch in disguise

He thought her a very respectable maid

And hoped she would never discover his trade

Likewise, the witch hides her magic from the wizard, pretending to be a typical domesticated housewife:

The witch was not wanting in womanly wiles

She covered her bridegroom with waffles and smiles

She only went witching on Saturday night

And hoped in between times it all would go right

Spoiler: it goes all wrong.

The couple foolishly tries to fix the problem by having a baby, but that only makes things worse:

Next day the witch bore the wizard an elf

So handsome he looked like the devil himself

And he was the devil himself

Demon lovers might be thrillingly attractive at first, but there’s definitely nothing appealing about raising the demon seed as your child.

The wizard turns out to be a deadbeat dad:

The wizard looked down at his son surprised

Saying “None of my family has lavender eyes

I think for my honor there’s only one course

I’ll ask you to grant me an instant divorce”

Meanwhile, the devil tries to convince the witch to stick it out with the wizard for the sake of the family: “The devil looked up from his crib and he smiled / ‘Don’t break up your home, you must think of your child.’”

And so they’re all stuck together. Converse saves her most potent satire for the poisonous final verse:

The witch settled down and the wizard as well

And both began raising the devil in hell

In rage and vexation and tears

The witch can’t stop witching, the wizard won’t speak

And though they’ve been married for only a week

It seems like a thousand years

With the ruthlessness of a pirate queen, Connie Converse eviscerates the idealized nuclear family of post-WWII America. Rooted in the same historical conditions as Jackson’s fiction of “the long 1950s,” Converse depicts marriage and family as its own circle of hell, and domesticity as a form of damnation.

As for the demon lover myth, Converse is much more skeptical than either Dylan or Jackson. “The Witch and the Wizard” lampoons the romantic myth that some mysterious stranger will arrive to rescue women from their miserable homes and deliver them to freedom. From Converse’s perspective, today’s demon lover is just tomorrow’s domestic tyrant. Give him enough time and offspring, and Black Jack Davey will turn into a big jerk daddy. Demon lovers be damned.

Work Cited

Beckett, Samuel. Waiting for Godot. The Complete Dramatic Works. Faber and Faber, 1986. 7-88.

Child, Francis James. English and Scottish Popular Ballads. Houghton Mifflin, 1904.

Converse, Connie. “The Witch and the Wizard.” Musicks. 2023.

Dylan, Bob. Chronicles, Volume One. Simon & Schuster, 2004.

---. Official Song Lyrics. The Official Bob Dylan Website.

https://www.bobdylan.com/.

Fishman, Howard. To Anyone Who Ever Asks: The Life, Music, and Mystery of Connie Converse. Dutton, 2023.

Franklin, Ruth. Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life. New York: W. W. Norton, 2016.

Gibson, Marion. Witchcraft: A History in Thirteen Trials. Scribner, 2023.

Glanvill, Joseph. Saducismus Triumphatus: or, Full and Plain Evidence Concerning Witches and Apparitions. London, 1681.

Heylin, Clinton. Dylan’s Daemon Lover: The Tangled Tale of a 450-Year Old Pop Ballad. Helter Skelter, 1999.

Hyman, Stanley Edgar. The Promised End: Essays and Reviews, 1942-1962. World Publishing Company, 1963.

Jackson, Shirley. The Lottery and Other Stories. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1982.

Karlsen, Carol F. The Devil in the Shape of a Woman: Witchcraft in Colonial New England. W. W. Norton, 1987.

Ringel, Faye. The Gothic Literature and History of New England. Anthem Press, 2022.

Tenschert, Laura. “Episode 21: Dancing Spell.” Definitely Dylan (10 June 2018), https://www.definitelydylan.com/listen/2018/6/10/episode-21-dancing-spell.

Woolf, Virginia. A Room of One’s Own. Hogarth Press, 1929.

I’m just seeing this and don’t have time to read before church, but my Sunday afternoon is planned out! Can’t wait!!!