Dylan in Cincinnati: November 2010

Art, and especially the stage, is an endeavor in which stumbling is unavoidable. There will be many unsuccessful days ahead, many entirely unsuccessful seasons, there will be great misunderstandings and deep disappointments and you have to be ready for all that, you have to expect it, and despite it all you must stubbornly, fanatically do what you think is right.

--Letter from playwright Anton Chekhov to actress Olga Knipper (4 October 1899)

In Chapter 19 of Andrew Muir’s indispensable One More Night: Bob Dylan’s Never Ending Tour, he describes the years 2005 through 2009 as “the period where I fell out of love with the NET” (335). His bill of particulars includes several distracting habits that Dylan lapsed into during this prolonged slump:

To recap these infelicitous techniques, the much discussed ‘upsinging’ trend was the starting point and was followed by: an odd mix of garbling and growling (sometimes referred to as the ‘Wolfman’ voice); the habit of repeating last or other crucial lines or half-lines; a weird, high-pitched ‘singing’ to indicate extreme emotion; and the inclusion of staccato, tick-tock passages that seem beyond rational or emotional comprehension. (351)

Veterans of Dylan shows during this period, or avid listeners to bootlegs, will immediately recognize what Muir is talking about. These stage gimmicks may have been tricks to compensate for the ravaged vocal cords of a man in his sixties who had been touring constantly for two decades. But Muir worried that they were symptoms of something more troubling, an erosion of authenticity, a performer gradually losing connection to his songs and to his audiences.

After a remarkable run of Cincinnati concerts at the turn of the century—Bogart’s in 1999, Riverbend in 2000, and Xavier’s Cintas Center in 2001—Dylan and his local audiences went through a dry spell coinciding with the drought chronicled by Muir. The problem was one of quality, not quantity.

Paradoxically, Dylan was playing more shows in the area than ever before. Between 2007 and 2013, he played five concerts at five different venues in Cincinnati and Northern Kentucky. And that’s only in the metropolitan area. During that same period, he also played a dozen shows within a two-hour drive of Cincinnati: three apiece in Dayton and Columbus, Ohio; three in Louisville, Kentucky; and one each in Indianapolis, Elizabeth, and Noblesville, Indiana. He was saturating the market . . . with subpar performances.

In the years between his brilliant concert at Xavier in 2001 and his return to form in 2019 and beyond, Dylan’s concerts became inconsistent affairs, with hits often outnumbered by misses. For instance, his return to Taft Theatre in 2007—site of his very first Cincinnati concert in March 1965—should have been cause for celebration. Instead, in my opinion it holds the distinction as the least compelling concert he ever played in the city. His 2008 concert, at the new National City Pavilion adjacent to Riverbend Music Center, wasn’t much better.

But Dylan remained committed to his art. He followed Chekhov’s advice in the epigraph above, stumbling through unsuccessful nights and seasons on stage, driven by a stubborn, fanatical devotion to live performance. His persistence paid off.

Muir dates the beginning of “the period where I fell out of love with the NET” in 2005, but he also sets an end date of 2009. After that, he started falling back in love with Dylan’s live performances. I feel the same about Dylan in Cincinnati, though the transition actually began south of the city. Glimmers of light began to return in 2010 at Northern Kentucky University’s Bank of Kentucky Center. It’s an uneven performance, but when it’s good, it’s damn good. The same can be said for Dylan’s 2012 concert at the (renamed) PNC Pavilion and the 2013 “AmericanaramA” tour stop at Riverbend.

I don’t plan to do full reviews of these three concerts, but I do want to highlight select performances from each. Join me on a deep dive into a couple standout songs from NKU, “When the Levee Breaks” and “Man in the Long Black Coat.” To fully appreciate what makes these songs special, let me situate them in various contexts because, as I keep emphasizing throughout this series, when and where a performance takes place matters.

Dylan Context

Between the Cintas Center concert at Xavier in 2001 and the Bank of Kentucky Center concert at NKU in 2010, Dylan was astoundingly active on multiple fronts. In 2002, he co-wrote (with Larry Charles) and starred in the bizarre film Masked and Anonymous. [If you want to hear recent reflections on that film, check out the Million $ Bash Roundtable on Jim Salvucci’s The Dylantantes.] In 2004, he published the amazing book Chronicles, Volume One: part memoir, part apprenticeship novel, part patchwork quilt of literary allusions, part self-mythology—and all magnificently Dylanesque.

He released two albums of original songs during this span: Modern Times (2006) and Together Through Life (2009), the latter largely co-written with Grateful Dead lyricist Robert Hunter. He also put out five more installments of the Bootleg Series, including volumes on: the Rolling Thunder Revue (2002); the 1964 Philharmonic Hall concert (2004); the No Direction Home soundtrack (2005) [from the wonderful Scorsese documentary released the same year]; my favorite, Tell Tale Signs (2008), a compilation of outtakes, alternate versions, and live performances from his late career renaissance (1989-2006); and the Witmark demos (2010) from the very beginning of his career.

In 2009 he surprised listeners with Christmas in the Heart, an album of Christmas covers, which some Dylan fans actually ended up enjoying. He also found time to host a hundred episodes of Theme Time Radio Hour for Sirius-FM between 2006 and 2009. Each episode was organized around a theme, with an eclectic mix of songs curated and quirkily commented upon by Dylan.

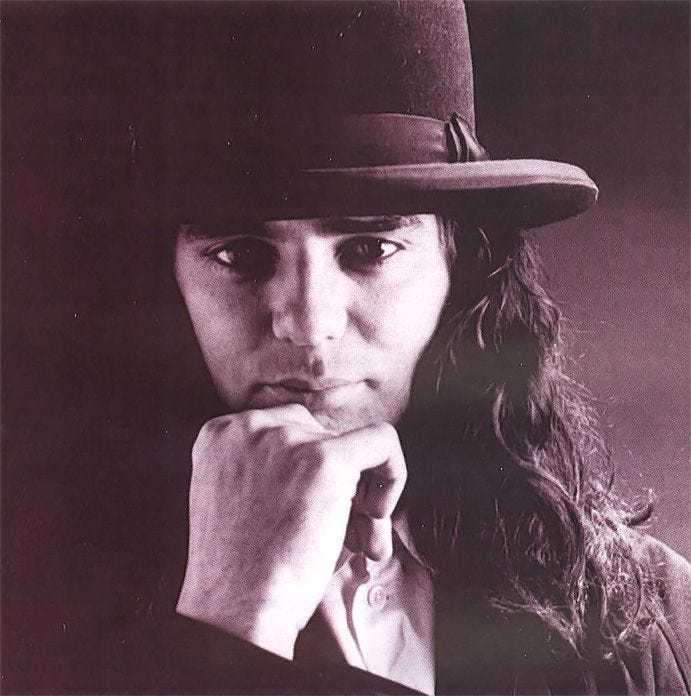

During this busy period, Dylan continued to devote the bulk of his time and energy to the Never Ending Tour, playing around a hundred concerts annually. The stalwart Tony Garnier remained on bass, manning the first-mate position he has held since 1989. After a period away from the band, fan-favorite Charlie Sexton was back on guitar. Joining him on guitar was the talented Stu Kimball, and pounding drums was New Orleans native George Receli. Dylan has enjoyed a run of amazing multi-instrumentalists on the NET, starting with Bucky Baxter and continuing with Larry Campbell; but the longest tenured of them all is Donnie Herron, who joined the band in 2005 and has remained by Dylan’s side ever since. Alas, if only he knew how to spell his last name correctly!

For his part, the general had long since handed over guitar duties to his lieutenants. Beginning in 2002, Dylan’s main instrument in concert has been the keyboard or piano, and his trusty harmonica when the mood strikes him. Mind you, he’s still willing to pick up his axe if the right person asks:

Dylan brought the A-team for his first concert in Northern Kentucky. Pause to consider this remarkable statistic. Only five musicians have ever played 1,000 or more concerts with Bob Dylan—and all five were on the NKU stage on November 3, 2010.

Cincinnati/Northern Kentucky Context

You might well ask why I’m covering a show that didn’t take place in the city of Cincinnati, nor even in the state of Ohio. Quick geography lesson for those unfamiliar with the region. Cincinnati is on the northern banks of the Ohio River, which serves as the border between the states of Ohio and Kentucky. Several towns in Northern Kentucky are part of the Cincinnati metropolitan area, including Covington and Newport along the southern banks of the river, and inland communities like Hebron (where the Cincinnati/Northern Kentucky International Airport is located) and Highland Heights (where the NKU campus is located).

I live in the neighborhood of Mt. Washington, on the eastern city limits of Cincinnati. My house is ten miles from Fountain Square at the heart of downtown. By comparison, NKU is only eight miles from Fountain Square. For all practical purposes, Highland Heights is a suburb of Cincinnati.

There’s no way to tell the history of Cincinnati without taking both the northern and southern banks of the Ohio River into account. That history involves commerce and industry. It also involves freedom and slavery, as I discussed in the introduction. And, most relevant to the present chapter, it involves floods. Before taking you down to the Bank of Kentucky Center, let me take you down to the banks of the river for an important chapter in local history. [If you’re not into local history, just scroll down to the concert and we’ll meet you there.]

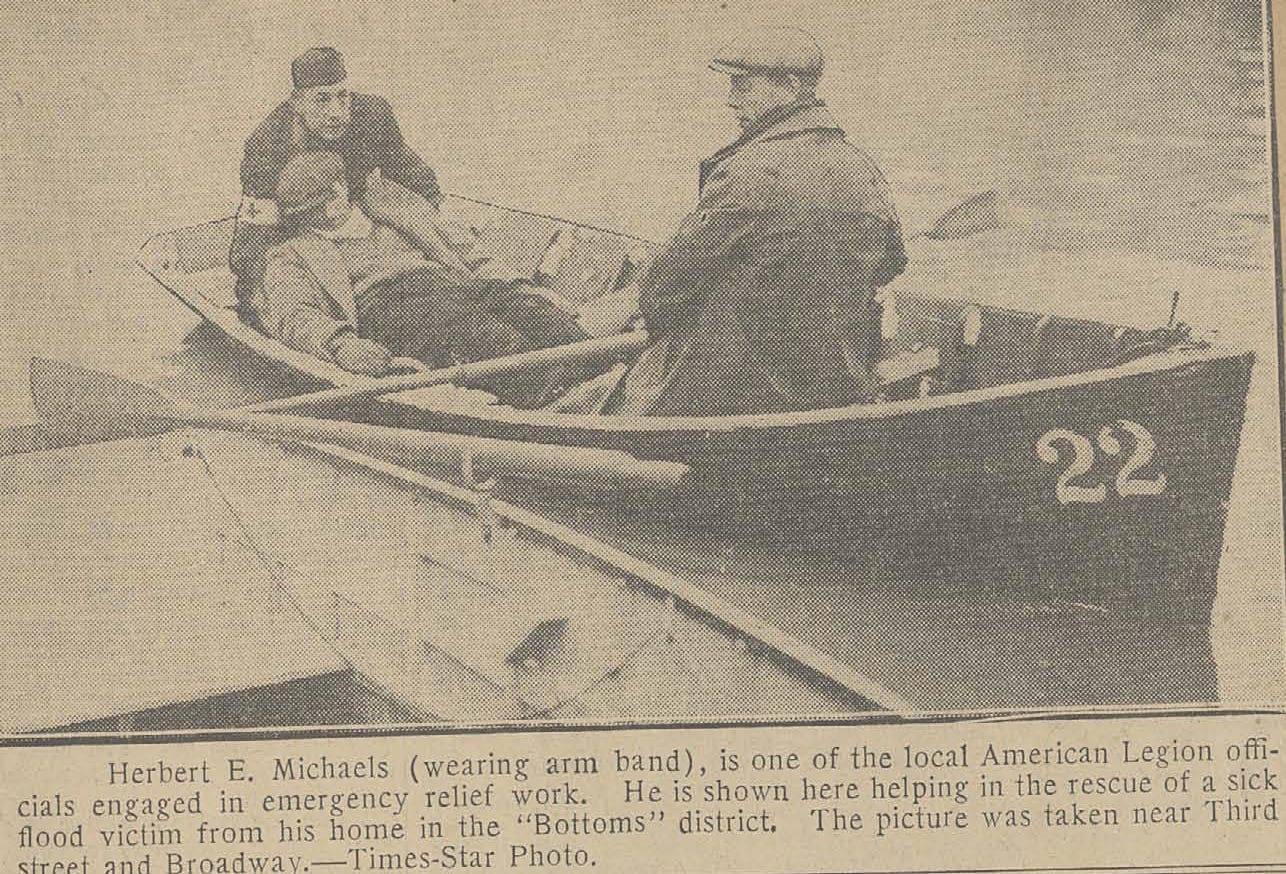

In his preface to The Thousand-Year Flood: The Ohio-Mississippi Disaster of 1937, David Welky points out that the 1937 Ohio River flood has long been overshadowed by the great Mississippi flood a decade earlier. The human misery, destruction, and loss of both events was staggering, and I don’t wish to stage a competition between them. Nevertheless, in terms of empirical data, the 1937 disaster was “the worst river flood in American history” (Welky xi). To paint the picture in broad strokes, “By the time the crest passed, the flood had killed hundreds of people, buried a thousand towns, and left a million people homeless” (xi).

Deborah Pitel lays out the basic timeline for the disaster in a 2020 profile for the Northern Kentucky Tribune. The unprecedented precipitation (rain, sleet, and snow) began on January 13. By January 18 the river reached the flood line of 52 feet and continued to rise at a rate of 6 inches per hour. On January 23, the river had already surpassed its previous high-water mark from 1884, when another six inches of snow fell on the region.

Welky quantifies the mind-boggling precipitation that set the disaster in motion: “There is no great mystery to what caused the 1937 flood: it rained. A lot. About 165 billion tons—close to 41,250,000,000,000 (quadrillion!) gallons—of ice, snow, sleet, and rain pummeled the Ohio valley in the month following Christmas. Certain areas on the lower Ohio absorbed twenty-five inches of precipitation” (59). The Ohio River officially reached its highest crest ever on January 26, 1937, at 79.99 feet, over 27 feet above the flood line. However, Pitel’s research suggests that the true crest was probably even higher. She reports that double indemnity clauses in certain insurance policies along the river would have kicked in at 80 feet, so the official crest seems to have been deliberately capped just below that figure.

Although the high-water mark was January 26, by all accounts the worst single day of the crisis came on January 24. As Welky puts it, “Black Sunday proved the tipping point along the Ohio, the day when a major flood turned into a nightmare” (89).

It must have felt like the apocalypse was under way when, in the midst of Cincinnati’s worst flood, the waters caught on fire. “Floodwaters smashed debris into gas lines, electrical systems, and oil tanks. Petroleum tanks wrenched from their moorings became floating bombs drifting with the current. Hundreds of thousands of gallons of gasoline shimmered on the water’s surface” (Welky 92). The worst fire broke out on the Mill Creek tributary, sparked by a derailed streetcar. The result was an inferno: “Flames rushed in every direction until they burned almost three-quarters of a mile long and a quarter-mile wide. Scores of families ran for their lives as gas tanks exploded and naphtha drums popped from the heat. Policemen from an adjacent patrol house rushed outside in time to see a thousand-foot tower of flame” (92). What a hellscape!

The catastrophe of 1937 exposed how ill-equipped areas along the Ohio River were to deal with a major flood. Cincinnati and Northern Kentucky ended up taking different approaches to flood management for future crises. If you’re ever in the area, take a stroll down to the river and you’ll get an object lesson in these approaches.

Although it took many years, Newport (just across the river from Cincinnati) built a giant 83-foot floodwall and earthen levee along a 1.5-mile stretch of the southern banks of the Ohio. This massive project, a collaboration between local and federal government and the Army Corps of Engineers, was completed in 1951. Today it is the site for Newport on the Levee, a large entertainment complex and home to the Newport Aquarium.

On the northern banks, Cincinnati civic leaders resisted such a plan, opting instead to build a series of parks along the river designed to absorb flood waters. Today you can jog, walk your dog, or enjoy a festival at Sawyer’s Point, Yeatman’s Cove, and Smale Riverfront Park, before climbing your way up the hill for a drink, a meal, a game, or a show.

Hey, why not take in a Dylan concert? The vast majority of his Cincinnati concerts have taken place in the flood plain of the Ohio. Over the course of his career, he has played five concerts within seven blocks of the river downtown: at Taft Theatre (1965, 2007), Riverfront Coliseum (1978), Aronoff Center (2021), and Brady Music Center (2023). And if you’re up for a little cruise, you can sail downriver a few miles to the site of six more Dylan concerts on the banks of the Ohio at Riverbend (1988, 1989, 2000, 2013) and the Pavilion (2008, 2012).

In short, there’s no telling the story of Cincinnati, or the story of Dylan in Cincinnati, without the Ohio River running right through the middle of the tale.

The Concert

When: November 3, 2010

Where: The Bank of Kentucky Center, Northern Kentucky University

Band: Bob Dylan (vocals, harmonica, guitar, and keyboard); Tony Garnier (bass); Donnie Herron (fiddle, mandolin, banjo, and steel guitar); Stu Kimball (guitar); George Recile (drums and percussion); Charlie Sexton (guitar)

Setlist:

1. “Rainy Day Women #12 & 35”

2. “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue”

3. “Stuck Inside of Mobile with the Memphis Blues Again”

4. “Love Sick”

5. “The Levee’s Gonna Break”

6. “Desolation Row”

7. “Cold Irons Bound”

8. “Man in the Long Black Coat”

9. “Summer Days”

10. “Tangled Up in Blue”

11. “Highway 61 Revisited”

12. “Workingman’s Blues #2”

13. “Thunder on the Mountain”

14. “Ballad of a Thin Man”

*

15. “Jolene”

16. “Like a Rolling Stone”

You can take the man out of the river, but you can’t take the river out of the man.

Rivers feature prominently in Dylan’s music, and it’s worth noting that he grew up near major waterways. He was born in Duluth beside Lake Superior and the St. Louis River, and he grew up in Hibbing (part of St. Louis County) near the northern origins of the Mississippi River. A generation earlier, T. S. Eliot grew up beside the Mississippi downriver in St. Louis, Missouri. As I listen to Dylan playing river songs in Cincinnati and Northern Kentucky, I find myself thinking of Eliot’s “Dry Salvages,” completed in 1941, the year of Dylan’s birth. Eliot sounds very much like a son of the river at the beginning of the poem:

I do not know much about gods; but I think that the river

Is a strong brown god—sullen, untamed and intractable,

Patient to some degree, at first recognised as a frontier;

Useful, untrustworthy, as a conveyor of commerce;

Then only a problem confronting the builder of bridges.

The problem once solved, the brown god is almost forgotten

By the dwellers in cities—ever, however, implacable.

Keeping his seasons and rages, destroyer, reminder

Of what men choose to forget. Unhonoured, unpropitiated

By worshippers of the machine, but waiting, watching and waiting.

Waiting for what? For its moment to strike, reminding mortals on its banks to fear the wrath of the strong brown god.

“The Levee’s Gonna Break”

Dylan and mates bring the river flooding inside the arena during their torrential performance of “When the Levee Breaks.”

This is blues rock at its finest. Phenomenal playing by the entire crew, with Dylan at the helm of a renegade steamboat chugging along the choppy waves of a rapidly rising tide. Memphis Minnie is one of Dylan’s blues heroes, and his song is clearly inspired by “When the Levee Breaks” (with Kansas Joe McCoy). Her song is one of many blues inspired by the 1927 Mississippi flood.

One of the joys of the NKU “The Levee’s Gonna Break” is the audience response. Sometimes the placement of the taper and the surrounding company make a big impact on your listening experience for bootlegs, positively or negatively. In this case, the impact is what they like to call these days “value-added.” Folks near the taper (and maybe the taper himself) are audibly having a ball blissing out to this bluesy barnstormer. They sing along enthusiastically, and they yelp their approval during the long musical interludes. You get the impression that these are veterans who have attended a ton of concerts. If you’ve memorized all the words to this deep cut from Modern Times, then you’re a Dylan freak. These aficionados know the real thing when they hear it and respond with unabashed, infectious delight. Rave on!

You know who wasn’t having a good time? The security guard who almost kicked our merrymakers out on their keisters. Listen to the very end of the track and you’ll hear our virtual seatmates get a stern warning: “There is no photography. There is no photography! Put the camera away. There’s not photography at all, on cell phones or anything. Whatever picture you took, delete it, and put your phone away please.” Luckily, she didn’t confiscate the taper’s recording device, which for all we know could have been that same phone.

Dylan establishes the destructive power of the river in divine terms: “If it keep on rainin’ the levee gonna break / If it keep on rainin’ the levee gonna break / Everybody saying this is a day only the Lord could make.” “The Levee’s Gonna Break” strikes a thunderous chord from the summit of Highland Heights, whose very name suggests a celestial vantage point, rumbling down a warning to the Ohio River below.

Like most blues, “The Levee’s Gonna Break” focuses on a troubled relationship. At times, the couple in the song seems on good terms: “When I’m with you I forget I was ever blue / Without you there’s no meaning in anything I do.” At other times, the couple bitterly exchanges accusations and threats [I’m quoting the lyrics Dylan sings at NKU]: “I picked you up from the gutter and this is the thanks I get / Yeah! I picked you up the gutter and this is the thanks I get / ‘I want to quit ya!’ Told ya ‘Naaah! Not just yet.’”

“The Levee’s Gonna Break” might seem at first like a weird mash-up of two completely different songs, one about a destructive flood and the other about a dysfunctional relationship. But I think this is really a Judeo-Christian blues about humans’ vexed relationship with Jahweh, the omnipotent, needy, petulant, spiteful Old Testament God. The argument dramatized in this song could just as well be between that cantankerous JWH and Abraham or Job or Moses; but given all the flood imagery, the most likely candidate is Noah.

Of course, you don’t have to be a figure from scriptures to know what it’s like to depend upon a mighty force for your sustenance, and yet also fear that same force as your deadliest foe. You don’t have to be Noah to understand that the waters are both life-giving and death-dealing. You could simply live in the lowlands beside a major river, be it the Ohio or the Mississippi, the Thames or the Seine, the Nile or the Tigris and Euphrates, the Red River or the Rubicon. Only a river gonna make things right—until it makes everything wrong.

“Man in the Long Black Coat”

Dylan gave the NKU faithful a rare treat with “Man in the Long Black Coat.” Out of 102 concerts in 2010, he only played this song six times. This would turn out to be his only performance ever in the metropolitan area. The musical arrangement is unrecognizable:

Well, it is recognizable—as the Stray Cats’ “Stray Cat Strut,” or Ray Charles’s “Hit the Road Jack” or Lonesome Lee’s “Lonely Travelin’.” But it bears almost no resemblance to “Man in the Long Black Coat” as produced by Daniel Lanois and released on Oh Mercy.

Among the general public, Dylan’s collaborations with Lanois on Oh Mercy and Time Out of Mind sit on the top shelf alongside his best albums. Among Dylanologists, however, Lanois is a polarizing figure. Legions of haters love to throw shade on the producer’s stylistic distortions of Dylan’s songs. For his part, Dylan has given the anti-Lanois camp plenty of ammunition over the years, in various published interviews and in his chapter on Oh Mercy in Chronicles, and in permitting a new mix of the album for the Bootleg Series on Time Out of Mind. Long before the release of Fragments, partisans have pointed to Dylan’s radical rearrangements of songs from Oh Mercy and Time Out of Mind as proof that the singer wants to wrest back control of his art by essentially remixing the albums live on stage.

I don’t buy it. Dylan does this to all of his songs, so why single out the Lanois albums? When he completely reimagines some of his sixties songs in performance, should we regard it as a renunciation of Bob Johnston, or a correction of Tom Wilson? Of course not. Let’s enjoy Dylan’s creative reimagination of “Man in the Long Black Coat” without fashioning it into a cudgel for beating a dead horse.

I love the lilting swing of the music. “Man in the Long Black Coat” is downright creepy on Oh Mercy, but you could actually dance to the song at NKU, and you kind of want to. Maybe Dylan draws inspiration from the dance scene in the second verse:

Somebody seen him hanging around

At the old dance hall on the outskirts of town

He looked into her eyes when she stopped in to ask

If he wanted to dance, he had a face like a mask.

Tonight’s performance is a nice marriage of form and content, reinforcing the “death and the maiden” courtship element at the heart of the song.

Laura Tenschert has a super interesting interpretation of “Man in the Long Black Coat” in Episode 21 of Definitely Dylan. The organizing principle of this episode is songs about dancing, including spells that compel one to dance, or spells that are cast by dancing. Laura rightly places “Man in the Long Black Coat” in the long tradition of “demon lover” folk songs about a demonic stranger who comes to town and lures a woman away from her home and family, following him to her death and damnation. Dylan is very familiar with such songs, having performed and recorded classic examples like “The House Carpenter” and “Blackjack Davey.”

Laura argues that “Man in the Long Black Coat” departs significantly from the demon lover tradition:

The town that the woman leaves behind is described as this place of stasis. The traces of a hurricane and past storms seems not to have changed anything. The song literally opens with crickets, ya know? That’s how much is going on. And in the last verse there is somebody literally beating a dead horse. How much more can you evoke repetition and things not changing.

Confined and suffocating in this dead-end town, the woman in the song doesn’t need to be abducted by a mysterious stranger—she is positively eager to get out. According to Laura, “I think this is a song about decisions. It’s about the decisions that we make and, more importantly, the decisions that we don’t make. The woman in the song made the decision to break out of the stasis and to take initiative.”

Tying this song in with her “dancing spell” theme, Laura draws attention to the dance scene in verse two. “It is at that dance hall that the woman took the first step and asked this man to dance. […] This act of initiative reminds me of the act of transgression of Eve when she took the apple. The woman in the song, too, is giving in to her curiosity, and somewhat overstepping a boundary.” Laura contrasts the woman’s daring transgressions with the guilt-inducing sermon of the preacher in the following verse. The song offers an alternative lesson in the bridge:

There are no mistakes in life some people say

And it’s true sometimes you can see it that way

People don’t live or die, people just float

She went with the man

In the long black coat

What does that mean? Laura draws this astute conclusion:

I think the woman’s decision in the song is to no longer float, but to take a step to live. And of course, there are mistakes, the song seems to say, but what if the worst mistake of all is to not make any decision and to just stay stuck? The woman’s decision to take initiative is despite the possibility that it’s a potential mistake.

This interpretation rings true to me. It also jibes with my take on the Dylan-Lanois collaboration. According to Chronicles, Dylan arrived in New Orleans with most of the lyrics already written for Oh Mercy. “Man in the Long Black Coat” was one of only two songs [along with “Shooting Star”] that he wrote on site in the midst of his tempestuous recording experience with Lanois. Note how Dylan makes a point in Chronicles of stressing the producer’s dark features on their first meeting: “Lanois sat down. He was noir all the way—dark sombrero, black britches, high boots, slip-on gloves—all shadow and silhouette—dimmed out, a black prince from the black hills” (177).

I think Dylan tapped into the thrill and trepidation of working with this innovative producer and channeled it into the lyrics of “Man in the Long Black Coat.” On some level, he appears to associate Lanois with the title character, while Dylan identifies with the woman in the song. Like the woman in Laura’s interpretation, Dylan was taking a chance by following this mysterious dark stranger, knowing it could be a terrible mistake. But he found himself at a moment of stasis in the eighties—stuck—and it was time to change. So he threw caution to the hurricane breeze and asked Blackjack Danny to dance.

In Laura’s words, “The invitation to dance was the woman signaling a willingness for change, a breaking of the spell of stasis, and the newfound freedom that comes in the form of a dance.” I agree, and the highly danceable version of “Man in the Long Black Coat” at NKU further accentuates this connection. Of course, in live performance the terms of the seduction shift, as Dylan invites the audience to join him in the dance. But the allure of freedom remains much the same either way.

There is one lyrical variation worth pointing out in “Man in the Long Black Coat.” On the album Dylan sings, “People don’t live or die, people just float.” However, at NKU he sings, “I went down to the river, I just missed the boat.” If you look on Dylan’s official website, this latter line is actually the copyrighted version. I’ve always loved the floating image, so I missed its absence at first. But now I realize that there’s something quite clever about “I went down to the river, I just missed the boat.”

Who went down to the river and missed the boat? Notice that this is the only appearance in the entire song of a first-person voice and perspective. Surely the “I” narrator is the jilted husband [aka the house carpenter] who arrives too late to prevent his wife from leaving. Aha! Where has he been hiding all these years?

I also like how this line guides us back down to the river, the scene of the crime from the husband’s perspective, and the scene of liberation for the long-gone wife. The river is where she makes her fateful decision to leave—seizing the opportunity that first opened on the dance floor—and the river is also her means of escape. This is classic river imagery for Dylan, who consistently associates rivers with crossing over from one bank to another, from one stale and depleted reality to something fresh and rejuvenating.

The wife crosses over—the husband does not. Where did her journey lead? Who did she become? Don’t ask her husband because he wouldn’t know. He missed the boat. He remains stuck in the land of the beaten horse. At least the dude in “Boots of Spanish Leather” got a letter every now and then. Not this guy: “She never said nothing, there was nothing she wrote / She went with the man in the long black coat.”

“The Levee’s Gonna Break” and “Man in the Long Black Coat” made crossing the Ohio River from Cincinnati to Kentucky worth the trip. Thanks for crossing over with me. We’ll return to the river in the next installment with a select survey of Dylan’s 2012 concert at Cincinnati’s PNC Pavilion. See you on the other side!

Works Cited

Bootleg audio recording (LB-8964). Taper unknown. The Bank of Kentucky Center, Northern Kentucky University, Highland Heights, Kentucky (3 November 2010).

Chekhov, Anton. Anton Chekhov’s Life and Thought: Selected Letters and Commentary. Trans. Michael Henry Heim. Ed. Simon Karlinsky. Northwestern University Press, 1997.

Dylan, Bob. Chronicles, Volume One. Simon & Schuster, 2004.

---. Official Song Lyrics. The Official Website of Bob Dylan.

https://www.bobdylan.com/.

Eliot, T. S. “The Dry Salvages.” Four Quartets. http://www.davidgorman.com/4quartets/3-salvages.htm.

Muir, Andrew. One More Night: Bob Dylan’s Never Ending Tour. CreateSpace, 2013.

Pitel, Deborah. “Our Rich History: The Flood of 1937 and flood control in Newport; a controversy over 79.99 ft. measurement.” Northern Kentucky Tribune (25 May 2020). https://nkytribune.com/2020/05/our-rich-history-the-flood-of-1937-and-flood-control-in-newport-a-controversy-over-79-99-ft-measurement/#:~:text=The%20floodwall%20consisted%20of%20both,and%2012%2C800%20tons%20of%20steel.

Tenschert, Laura. “Episode 21: Dancing Spell.” Definitely Dylan (10 June 2018), https://www.definitelydylan.com/listen/2018/6/10/episode-21-dancing-spell.

Welky, David. The Thousand-Year Flood: The Ohio-Mississippi Disaster of 1937. University of Chicago Press, 2011.

I love the attention to detail and narratives that you weave into these concert reviews. I attended this show, as well as the PNC Pavilion concert, and I recall both as having some wonderful highlights. I remember Leon Russell opening at PNC. Was he at Northern as well?

As I recall, there was no opening act at the NKU show. Knopfler would have been interesting.