Creole Trilogy

Yellow Moon, Oh Mercy, and Acadie

Bob Dylan is a myth-maker, and Chronicles is a wonderful work of auto-mythology. He frames pivotal chapters of his life as a hero’s quest: overcoming obstacles, resisting temptations, cultivating wise mentors, fighting wily enemies, hearing his true calling, embracing his destiny, and choosing the right path forward at the crossroads. It’s the stuff of legends and fairy tales, as well as morality plays and gospel hymns: “I once was lost / But now I’m found / Was blind / But now I see.” In the longest chapter of Chronicles, “Oh Mercy,” Dylan begins with a description of his hand injury in 1987. His art and career, like his hand, were damaged almost beyond repair, atrophied from years of abuse. However, in the second half of the eighties, through a series of serendipitous encounters and sudden epiphanies, culminating in his epic Battle of New Orleans with the dark knight Daniel Lanois, Dylan achieved regeneration. He recovered his superpowers by renewing his commitment to live performance—launching the Never Ending Tour in 1988—and by making a real effort to produce high-quality work in the studio worthy of his talents—recording and releasing the comeback album Oh Mercy in 1989.

That’s one way of telling the story, the Dylan-centric version, focused on the travails and triumphs of the rejuvenated hero. In this piece, however, I’d like to offer a counternarrative.

Ever since the release of Fragments, I’ve been renewing my love of Daniel Lanois. You know how much I adore Time Out of Mind, dear reader, so of course I was elated to have even more tracks from the TOOM sessions to luxuriate in and meditate upon. But that remix of the album made me feel very defensive—how could they do that to Lanois?—and spurred me into clinging protectively to the magnificent album as released. It motivated me to go back and spend a lot of time listening again to the first Dylan-Lanois collaboration on Oh Mercy, and I also re-read Lanois’s memoir Soul Mining. Reflecting on his debut album, which was recorded in the same space as Oh Mercy and released only two weeks later, Lanois wrote something that really struck me: “My first record, Acadie, was finished in the Soniat house with the ghost of Bob Dylan at the coffee machine. The setup stayed the same, and I regard my record as stage three of the New Orleans trilogy: Yellow Moon first, Oh Mercy second, and then my Acadie” (109). Hmmm…that’s a very different way of telling the story, eh? And it is a story worth telling.

I was tempted at first to be cheeky and call this piece “Lanois-iana Trilogy.” However, I don’t want to misrepresent the collaboration by simply replacing a Dylan-centric perspective with a Lanois-centric perspective. The idea is to decenter the narrative in order to more accurately depict the nature of true collaboration, which is a back-and-forth exchange among equals, an artistic conversation among fellow creators. Yellow Moon, Oh Mercy, and Acadie—each produced by Lanois and released in 1989—are capable of standing alone as great individual albums in their own right. However, I’ve come to share the producer’s view that it’s even more interesting to think of them in relationship to one another as a trilogy of mutual influence and musical conversations.

I’ve opted for the title “Creole Trilogy,” not just to stamp “Made in New Orleans” on the label, but also to invoke “creole” in the sense of culturally hybrid. In his groundbreaking book The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness, Paul Gilroy challenges essentialism: the claim that some cultural expressions (like music) were created by a single racial or ethnic group and therefore should permanently remain the privileged and exclusive domain of that group. “Against this choice stands another, more difficult option: the theorisation of creolisation, métissage, mestizaje, and hybridity” (Gilroy 2). Music resists neat categories and defies segregation. Musicians delight in eluding capture by border patrol officers who would confine them to one side of a wall or another. In this sense, music doesn’t have to be made in Louisiana to be creole—but it sure helps. The trilogy of albums I’m considering are ideal examples of cultural mixture and creative intermingling. A lot of diverse ingredients went into the musical gumbo cooked up in Lanois’s New Orleans studio in 1989.

Yellow Moon

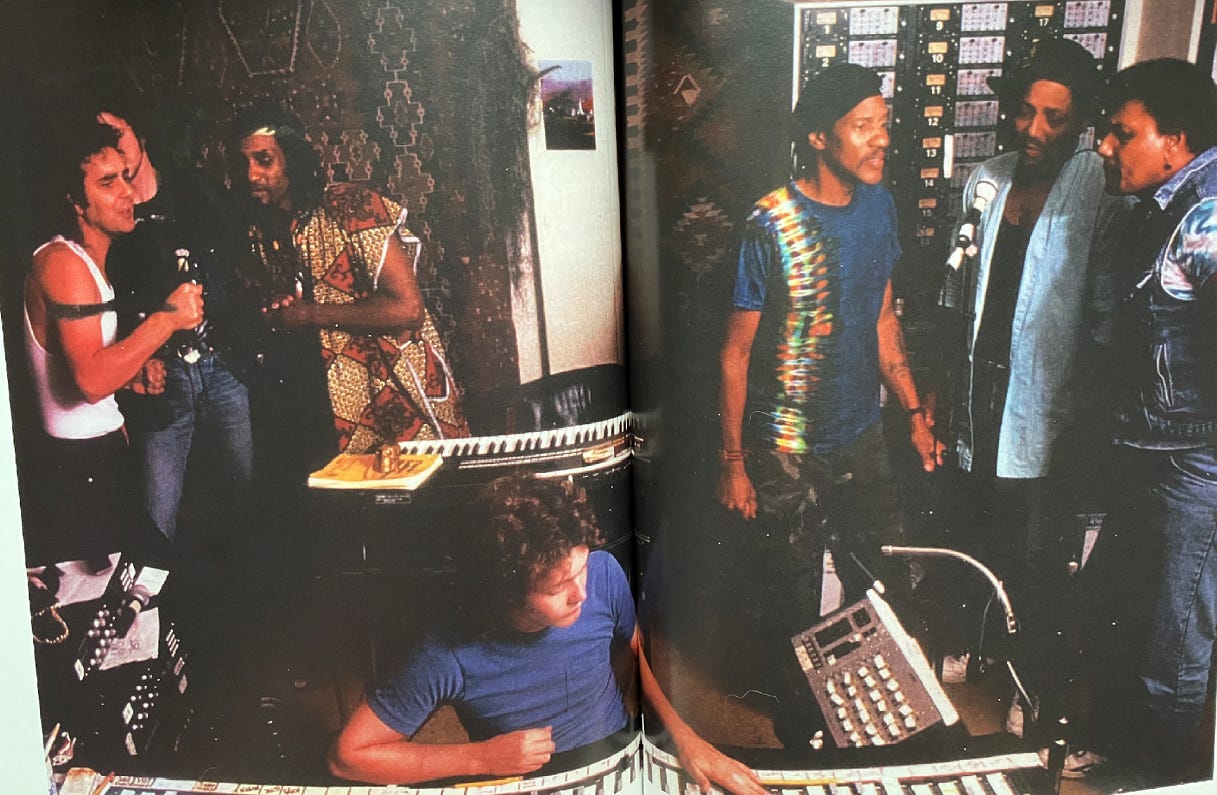

Lanois was a tremendously successful producer in high demand in the mid-eighties, shuttling between Canada, the United States, England, and Ireland, making innovative hit records for U2 [The Unforgettable Fire (1984) and The Joshua Tree (1987)], Peter Gabriel [So (1986)], and Robbie Robertson [Robbie Robertson (1987)]. In 1988 he moved to New Orleans and set up shop at Emlah Court, an apartment building in the French Quarter. He and sound engineer Mark Howard converted it into a mixed-use studio and living quarters. Soon Lanois gravitated into the orbit of the city’s favorite sons, the Neville Brothers. Cyril Neville recalls the circumstances:

I’ve always said that the brothers are our own best producers. But when we signed with A&M in 1989 and they hooked us up with Daniel Lanois, the chemistry was right. Lanois was the baddest outside producer the Nevilles have ever known. He came to New Orleans and turned a house on St. Charles into a studio. Artie brought in a stuffed bobcat, some big ol’ rubber snakes, and thickets of moss to hang from the ceiling. Lanois had the voodoo vibe going strong; he had psychics dropping by; he let us hang loose; he encouraged using all sorts of sounds—crickets, the whistling wind, you name it—to catch our family flavor. Lanois knew how to kick back and stay out of the way while bringing out the essential Nevilleness of me, Artie, Aaron, and Charles. (Ritz 324)

Holed up in this idiosyncratic laboratory, Lanois and the Nevilles assembled a house band of veteran local musicians and experimented day and night throughout 1988, with sound engineer Mark Howard documenting the results. In March 1989 Yellow Moon was released, and it remains the Neville Brothers’ most ambitious and fully realized album to date.

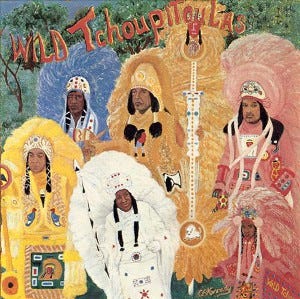

Art, Aaron, Charles, and Cyril Neville grew up in the 13th Ward of New Orleans, and each pursued a musical career. But they didn’t come together as a group until their uncle George Landry, aka Big Chief Jolly, assembled them to make The Wild Tchoupitoulas (1976).

The songs and chants on this album are vintage expressions of the Mardi Gras Indians, an ethnically hybrid tradition dating back to the 19th century. Cyril Neville explains,

Some say it started during the Civil War when slaves were no longer allowed to drum and dance in Congo Square. There’s evidence that some of the runaway slaves were taken in by Indian tribes. A deep bond between American Indians and African Americans became a sacred secret in parts of Louisiana. Both peoples were oppressed and slaughtered, both estranged from a system of belief—in Africa and America—that ran counter to the established culture. You hear in the Indian chants of New Orleans the soul of West Africa, you also hear the soul of Haiti and Trinidad, places with their own tradition of Mardi Gras Indians. (244)

Indian identity is integral to the history, ethos, and music of the Neville Brothers, and this is foregrounded in “My Blood,” the opening track of Yellow Moon. Cyril Neville’s political activism and cross-cultural allegiances shine through the lyrics:

Send some justice to America

Free the blood from the land

That’s my blood down there

On the reservation

That’s my blood down there

All the Indian nations

That’s my blood down there

The first Americans

That’s my blood down there

I’m gonna help them if I can now.

The album returns to this theme with “Wild Injuns” as the closer. The song name-checks each of the Mardi Gras Indian tribes, describes several ceremonial rituals, and ends with praise for Big Chief Jolly, the leader of the Wild Tchoupitoulas [a Choctaw word meaning “those who live at the river”].

The most striking feature of Yellow Moon is surely the polyrhythmic percussions. The drums are irresistible. The political consciousness of several songs makes you think, but the beats make you dance. I dare you to listen to the album and remain sitting still, without bopping your head, shimmying your shoulders, tapping your feet, or shaking your booty. You can’t do it! The Neville Brothers’ signature sound is drawn in part from Native American influences, but it’s also a with mélange of Pan-African sources. According to Cyril Neville,

They say New Orleans is the most northern port of the Caribbean, and a sense of island life—island dreams, island songs, island rhythms—is definitely part of our heritage. The slave trade with Africa, souls being shipped and abandoned, cultures confused and commingled, the sense of oppression, the sense of relaxation, humid heat hanging over your head like a hammer, carnivals and rituals and a beat that goes from morning till night, drums that talk like singers and singers who sing like drums. (Ritz 233)

Lanois was already experimenting heavily with drum techniques on albums before arriving at Emlah Court. But make no mistake about it: he was the student in New Orleans, not the teacher, and the Nevilles gave him an advanced seminar on the subject. Lanois would apply these lessons to later productions. He even brought in Cyril Neville to play timbales and tom-toms for “Political World,” “Most of the Time,” and “What Was It You Wanted?” on Dylan’s Oh Mercy.

At various points on Yellow Moon, the Nevilles profess empathy and allegiance with people suffering political strife across the globe in the late eighties, including inhabitants of South Africa, Haiti, Nicaragua, El Salvador, and Belfast. The album also maintains strong ties closer to home, if more distant in time, including songs from and about the U.S. Civil Rights Movement of the fifties and sixties. Cyril Neville contributes “Sister Rosa,” a rap saluting Rosa Parks [“Thank you Miss Rosa / You are the spark / You started our freedom movement / Thank you Sister Rosa Parks”]. But the American civil rights theme is accentuated most in songs showcasing Aaron Neville—all of them connected to Bob Dylan.

Neville covers one of the most moving songs of the era, “A Change Is Gonna Come.” It would be impossible to top Sam Cooke’s timeless original, but Aaron Neville soars nearly as high. Readers of Shadow Chasing probably know that one of Cooke’s major inspirations for “A Change Is Gonna Come” was Dylan’s “Blowin’ in the Wind.” Dylan’s influence in Yellow Moon is felt even more directly in Aaron Neville’s two covers from The Times They Are A-Changin’, “Ballad of Hollis Brown” and “With God on Our Side.” The latter is simply the best version of the song I’ve ever heard, and Dylan apparently felt the same way. Bono recommended Lanois as producer for the album that became Oh Mercy, and Dylan went down to New Orleans to check out the scene for himself. In the studio he heard a playback of “With God on Our Side,” and he was thunderstruck. He reflects in Chronicles,

Aaron is one of the world’s great singers, a figure of rugged power, built like a tank but has the most angelic singing voice, a voice that could almost redeem a lost soul. It seems so incongruous. So much for appearances. There’s so much spirituality in his singing that it could even bring sanity back in a world of madness. It always surprises me to hear a song of mine done by an artist like this who is on such a high level. Over the years, songs might get away from you, but a version like this always brings it closer again. (178)

Neville makes the song his own through his inimitable vocal styling. He even has the chutzpah to add a new verse:

In the 1960s

Came the Vietnam War

Can someone tell

What we were fighting for?

So many young men died

So many mothers cried

Now I ask the question

Was God on our side?

Neville further embellishes “With God on Our Side” by tacking on a coda from a children’s hymn, singing “Jesus loves me / This I know” to conclude the song. Aaron Neville ultimately deflects the song’s critique of Christian nationalism and steers it toward sincere faith in a loving God. The brash young author of The Times They Are A-Changin’ might have balked at such an interpretation back in the early sixties. But Dylan responded to Neville’s interpretation of “With God on Our Side” in 1988 from the perspective of an older religious convert, and he was deeply moved by what he heard.

If Lanois needed an audition as Dylan’s next producer, then with Aaron Neville’s help he landed the part. Any producer who could elicit this kind of transcendent performance had earned Dylan’s respect. As Lanois recalls in Soul Mining,

Dylan listened to a few songs off the Nevilles’ record, including a version of his own ‘God on Our Side’ sung by Aaron Neville. Aaron’s performance was riveting, and at the end of the playback, Bob looked at me and said, ‘That sounds like a record.’ After some philosophical exchange, we agreed to hook up in the spring and make his next album. Bob is no fool; he knew that something was going on here. (101)

Dylan would enter the creole laboratory and join the musical experiment in 1989.

Oh Mercy

Yellow Moon was released in March, and that same month Dylan settled into New Orleans and began laying down tracks for Oh Mercy. Several of the same musicians who worked with the Nevilles also made appearances on Dylan’s album, and, as was his custom, the multi-instrumentalist Lanois played on most of the songs he produced as well. Other local musicians, including zydeco legend Rockin’ Dopsie and his band, occasionally sat in. The center of gravity for these sessions shifted locations, however, to nearby Soniat House. In this private setting, Dylan and Lanois worked more intimately on vocal and guitar arrangements, with Mark Howard capturing it all on tape.

As readers of Chronicles know, Dylan and Lanois clashed repeatedly during the Oh Mercy sessions. Lanois won the producer gig by impressing Dylan with his work ethic, dedication to excellence, and complete commitment to the artists he recorded. But once Dylan arrived and settled into work with the producer, he discovered other traits that he hadn’t anticipated and clearly didn’t appreciate. Dylan preferred the fresh early takes of songs, but Lanois often insisted on many subsequent takes in search of a superior sound. Simply put, Lanois thought Dylan could do better if he tried harder, and Dylan thought his music would sound better if Lanois would get the hell out of his way and let him do his thing.

For instance, consider “Political World.” This was the first song Dylan wrote for the album, and it eventually batted lead-off on Oh Mercy. It was also the first song he and Lanois recorded in New Orleans, and it provoked the first of many arguments over seemingly incompatible creative visions for the record. Drop the needle or hit the play button and judge for yourself. What a first impression! You’ve never heard a Dylan record sound like this before. Listen to that rhythm section, with Tony Hall on bass and Willie Green on drums, with extra percussions from Daryl Johnson and Cyril Neville. Check out those guitars, starting with Dylan and Lanois, but then turbo-charged with the addition of Brian Stoltz and Mason Ruffner, roaring forward and picking up speed like the last firetruck from hell. In Chronicles, however, Dylan registered his disapproval: “The song had got shanghaied. You could tap your foot to it, clap your hands or jig your head up and down, but it didn’t open up the world of the real. It sounded like I was singing from the midst of the herd, a lot of artillery and tanks in the background. The longer it went the worse it got.” Lanois asked Dylan what he thought. “‘I think we missed it’” (184). Ya think? I think they nailed it.

This is precisely the sort of aesthetic transfusion and career-boosting jolt Bono was hoping for when he played matchmaker for Dylan and U2’s producer. Bono first met Dylan at a backstage interview before the 1984 Slane Castle concert. The young rocker’s first question seems in retrospect to already anticipate the Oh Mercy clash of titans:

Bono: When you’re working with a producer, do you give him that lee-way to challenge you?

Dylan: Yeah, if he feels like it. But usually we just go into the studio, and sing a song, and play the music, and have, you know ...

Bono: Have you had somebody in the last five years who said ‘that’s crap Bob.’

Dylan: Oh, they say that all the time!

Bono: Mark Knopfler, did he say that?

Dylan: I don’t know ... they spend time getting their various songs right, but with me. I just take a song into the studio and try to rehearse it, and then record it, and then do it.

This low-key, don’t-sweat-it approach to record production shows in Dylan’s lackluster studio work in the mid-eighties. Bono was angling to hook Dylan up with Lanois as a producer who would shake the artist from his torpor, challenge him to reach for higher standards, call him out on subpar work, and prod him into musical innovations he might not otherwise bother with. The results speak for themselves on Oh Mercy and later on Time Out of Mind.

When you listen to “Political World,” or even more so the great Oh Mercy outtake “Series of Dreams,” you can hear the influence of the Nevilles on Lanois, and you can hear Lanois adapting and projecting those lessons forward onto Dylan’s music—even if Dylan stubbornly resisted those impulses at times. I’m also reminded of Dylan’s epic diss of Lanois to David Fricke, explaining how he snatched “Mississippi” away from the producer’s meddling clutches to rescue the song from “witch doctors,” “ideological voodoo,” and “some steamy cauldron of drum theory.” In the context of the “Creole Trilogy,” this charge seems tantamount to accusing Lanois of trying to turn a Dylan song into a Neville Brothers song. Well, you could do a helluvalot worse. To lay my own cards on the table, I must say that, between Tell Tale Signs and Fragments, I’ve yet to hear a Lanois-produced take of “Mississippi” that I didn’t love. And if Dylan considered the polyrhythmic drumming on “Series of Dreams” justifiable cause for excluding it from Oh Mercy, then it strikes me as yet another instance from the eighties where Dylan seems inexplicably deaf to his own genius—and that of his producer.

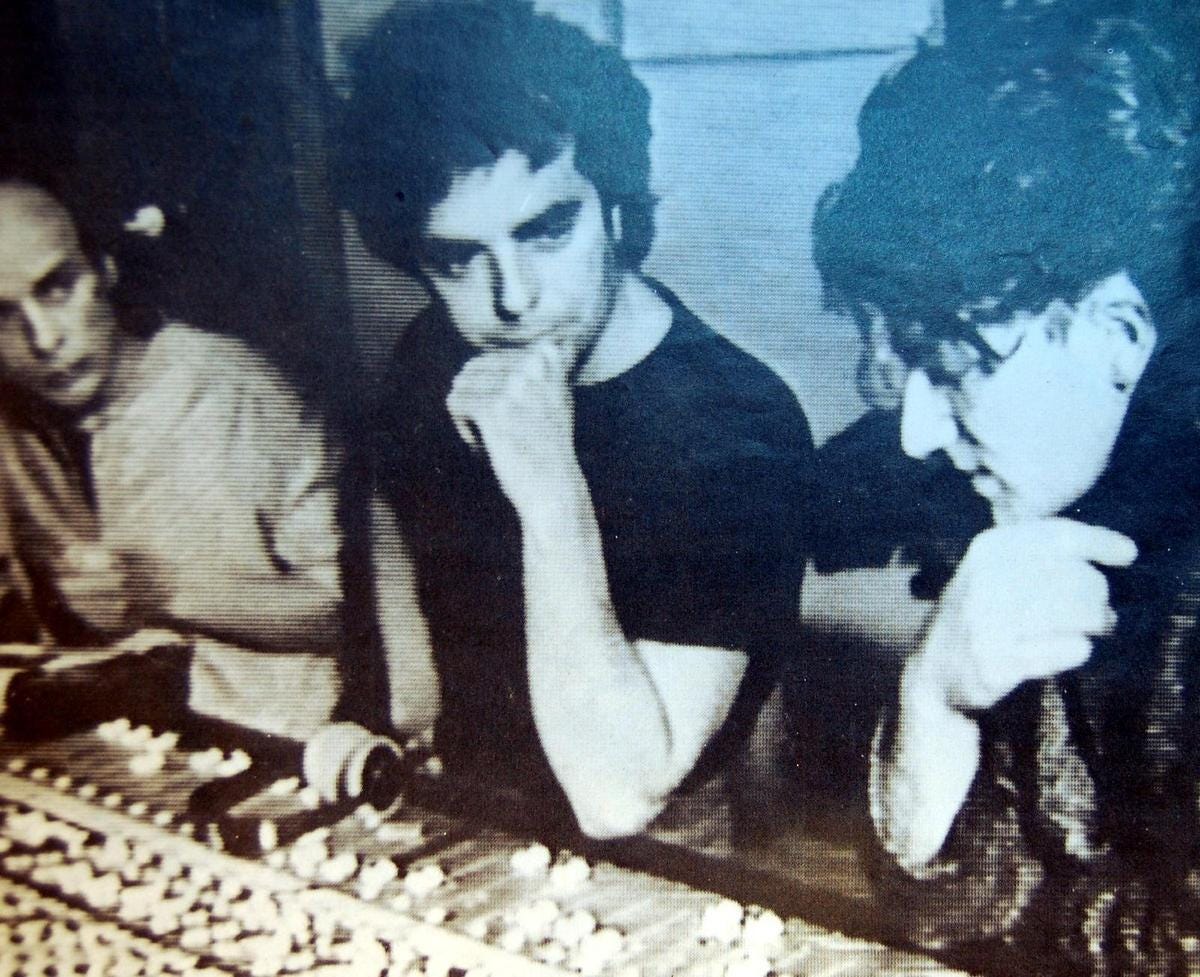

Most of the Oh Mercy lyrics were written in advance of the sessions, so perhaps Dylan had already formed ideas about how these songs should sound before he arrived. When he heard radically different mixes emerging from the studio, he worried that his songs were being hijacked to create an alien sound or to serve someone else’s agenda. “The song had got shanghaied,” Dylan wrote of “Political World,” and he felt the same way about several other tracks. But Lanois knew from experience how to build the sonic architecture of a great album, and he asked Dylan to trust him. In his memoir Lanois describes their intimate working conditions at the Soniat house: “Bob was inspired, and I was proud of our progress, though I know that part of him was pining for more of a full-band setup, which had served him well in the past. There were moments of insecurity regarding our back-porch-kitchen-with-two-chairs approach, but we had a great vocal sound, and I felt that our nucleus was intact” (107). They would eventually move their work over to the studio and layer in other instruments and effects, but beating heart of Oh Mercy songs was the vocal and guitar work laid down by Dylan and Lanois in Soniat.

A table for two—one pair of eyes stares into the other on a handshake, no other opinions are considered. The world loves a record that is specific in its stance. I will gladly embrace dictatorship if it creates a better chance for potent directed work. The setting for Oh Mercy promoted a ‘staring eyes’ feeling—one pair of eyes staring into another, or out in to the darkness of New Orleans. (Lanois 107-8).

Dylan and Lanois were more simpatico when it came to the two songs actually written during the sessions, “Man in the Long Black Coat” and “Shooting Star.” Both reflect the specific conditions of their creation in New Orleans, and both engage in musical conversations with Dylan’s collaborators and inspirations.

Dylan vividly describes New Orleans in Chronicles as a teeming necropolis crowded with the restless spirits of the undead:

The first thing you notice about New Orleans are the burying grounds—the cemeteries—and they’re a cold proposition, one of the best things there are here. Going by, you try to be as quiet as possible, better to let them sleep. Greek, Roman, sepulchers—palatial mausoleums made to order, phantomesque, signs and symbols of hidden decay—ghosts of women and men who have sinned and who’ve died and are now living in tombs. The past doesn’t pass away so quickly here You could be dead a long time. The ghosts race towards the light, you can almost hear their heavy breathing—spirits, all determined to get somewhere. (180)

In “Man in the Long Black Coat” Dylan tailors these phantasmal New Orleans threads into a spooky funeral suit, cut from the cloth of a vampire’s cloak. On one level, the lyrics read like a “Death and the Maiden” allegory or a demon-lover ballad, as the Grim Reaper sweeps into town to abduct his next victim and flee with her soul.

There are no mistakes in life some people say

And it’s true sometimes you can see it that way

People don’t live or die people just float

She went with the man in the long black coat

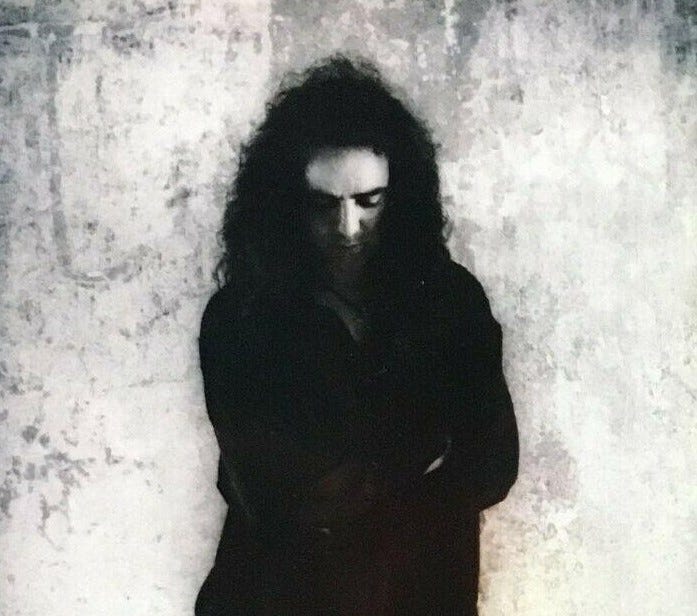

On another level, however, I wonder if Dylan’s inspiration came from those dark eyes staring back at him across the kitchen table at Soniat. In Chronicles he depicted his collaborator/nemesis in mythic terms, describing his first impression of Lanois like a dark knight: “He was noir all the way—dark sombrero, black britches, high boots, slip-on gloves—all shadow and silhouette—dimmed out, a black prince from the black hills” (177). Once the two started working together, Dylan felt his songs were being “shanghaied,” lured away from their familiar surroundings. Isn’t that basically the scenario of “Man in the Long Black Coat”? A dark, charismatic stranger arrives on the scene and seduces [Dylan’s Muse?]. Dylan resisted Lanois for a long time, but by the end of the sessions he came around. The two figured out how to work together compatibly to get where they needed to go. Dylan generously praised Lanois’s production on this song in particular:

Before the lyrics even came in, you knew that the fight was on. This is Lanois-land and couldn’t have been coming from anywhere else. The lyrics try to tell you about someone whose body doesn’t belong to him. Someone who loved life but cannot live, and it rankles his soul that others should be able to live. Any other instrument on the track would have destroyed the magnetism. After we had completed a few takes of the song, Danny looked over to me as if to say, This is it. It was. (Chronicles 216).

Dylan went with the man in the long black coat.

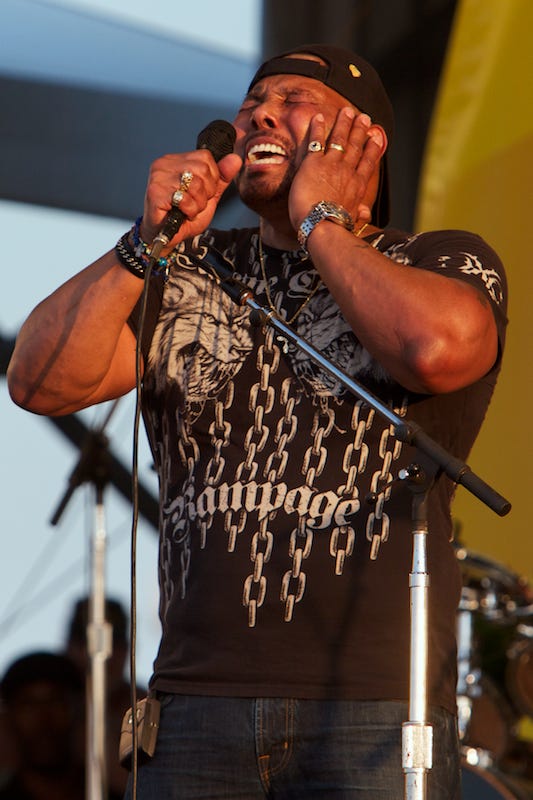

The closer on Oh Mercy is “Shooting Star,” a creole palimpsest of a song that bears palpable traces of various influences. One important voice in “Shooting Star,” not on the record but in the mind of the songwriter, is Aaron Neville. Dylan delivered a fascinating acceptance speech when he was honored as the 2015 MusiCares Person of the Year. The ceremony included several performances of Dylan songs, including a special request by the man himself for Aaron Neville to sing “Shooting Star.” In a follow-up interview with Bill Flanagan, Dylan effusively praised Neville and revealed that the singer was an inspiration for the song:

I could always hear him singing that song. He’s recorded other songs of mine, all great performances, but for some reason I kept thinking about ‘Shooting Star,’ something he’s never recorded but I knew that he could. I could always hear him singing it for some reason, even when I wrote it. I mean, what can you say? He’s the most soulful of singers, maybe in all of recorded history. If angels sing, they must sing in that voice. I just think his gift is so great. The man has no flaws, never has. He’s always been one of my favorite singers right from the beginning. ‘Tell it Like it Is,’ that could be my theme song. It’s strange, because he’s the kind of performer that can do your songs better than you, but you can’t do his better than him. Really, you can’t say enough about Aaron Neville. We won’t see his likes again.

Alongside the soaring angelic voice of Aaron Neville, Dylan must also have had a fallen angel in mind for “Shooting Star”: Richard Manuel. The title image is popularly associated with the volatile combustion of fame, since a shooting star shines brilliantly for a brief time and then burns out too soon. Most Shadow Chasing readers will be familiar with this sad story, but it bears repeating for its relevance to “Shooting Star.” Richard Manuel was a member of the largely Canadian band The Hawks, the backing group that accompanied Dylan on the tempestuous electric tours of 1965-1966.

After Dylan left the road and settled down in Woodstock, the band moved into a big pink house in nearby West Saugerties, where they would regularly get together and jam in the basement. These informal sessions eventually morphed into The Basement Tapes, and they served as seedbed for Music from Big Pink (1968), the debut album for The Band (as they were rechristened). The lead track on that album was “Tears of Rage,” composed at Big Pink with lyrics by Dylan and music by Richard Manuel, who also sang lead on the album version in heart-wrenching falsetto. Manuel takes the lead on the album’s closer as well, “I Shall Be Released,” another Dylan-penned lyric. The Band catapulted into international fame in their own right, but they continued to play with Dylan in concerts (Woody Guthrie Tribute, Isle of Wight, Last Waltz), the ’74 Tour, and the albums Planet Waves and Before the Flood. Meanwhile, Manuel gradually spiraled downward into drug addiction and alcoholism. Following a concert in Winter Park, Florida, in March 1986, Manuel’s shooting star burned out when he hanged himself in his hotel room. He was only 42.

Bandmate Robertson wrote the first musical tribute to Manuel following his suicide. “Fallen Angel” is the opening track on the solo debut Robbie Robertson (1987), co-produced with Daniel Lanois. In part Robertson seems to draw upon a previous elegy, “Dry Your Eyes.” He co-wrote that song with Neil Diamond, released it on the album Beautiful Noise (produced by Robertson), and performed it with The Band during The Last Waltz. It was inspired by Martin Luther King’s death and refers to a falling angel:

Right through the lightning and the thunder

To the dark side of the moon

To that distant falling angel

That descended much too soon

Come dry your eyes

Dry your eyes

Take your song out

It’s a newborn afternoon

And if you can’t recall the singer

You can still recall the tune

The sentiments of both grief and praise apply well to Manuel and provide a working model for Robertson. But he recalls a different singer and other tunes even more clearly in “Fallen Angel.”

Robertson has another debut opener in mind—“Tears of Rage”—as he laments his late friend:

Fallen angel

Casts a shadow up against the sun

If my eyes could see

The spirit of the chosen one

All the tears, all the rage

All the blues in the night

If my eyes can see

You kneeling in the silver light

The angel falls in this lyric, and so does the sun. It’s shining at first (“Casts a shadow up against the sun”), but it has set by the time we get to “blues in the night” and the moonlit prayer “kneeling in the silver light.” Perhaps Robertson is also subtly invoking the chorus of the other Dylan song most closely associated with Manuel, “I Shall Be Released.” Manuel sang a moving rendition as the closer on Music from Big Pink, and Rick Danko sang it at Manuel’s memorial service. Ever since then, it’s hard not to think of the long-suffering musician’s suicide when you listen to Music from Big Pink and hear Manuel’s piercing plea for release:

Dylan likewise conjures up celestial imagery in “Shooting Star,” which comes across as a direct response to “Fallen Angel.” The silvery night of Robertson’s elegy is suddenly illuminated by the blazing light of Dylan’s shooting star. Then it dissolves and the dawn returns again:

Seen a shooting star tonight

Slip away

Tomorrow will be

Another day

Guess it’s too late to say the things to you

That you needed to hear me say

Seen a shooting star tonight

Slip away

While we’re on the subject of fallen angels and shooting stars, and at the risk of putting too fine a point on it, remember that Manuel killed himself by hanging, not gunshot. The symbol of a “shooting star” could also relate to another musical comrade who died too soon at the beginning of the eighties, a star who was literally shot: John Lennon. Dylan would eventually compose an elegy squarely directed at Lennon in “Roll on John,” the album closer for Tempest (2012). But he may have already been testing out a tribute in his touching closer for Oh Mercy.

Dylan gives none of this away in his commentary in Chronicles. He knows better than to interrogate his inspirations when they arrive unbidden. “‘Shooting Star’ was one of the songs I wrote in New Orleans. I felt like I didn’t write it so much as I inherited it. […] The song came to me complete, full in the eyes like I’d been traveling on the garden pathway of the sun and just found it. It was illuminated” (213). That’s all well and good for an artist, but not for us critics, who specialize in looking gift horses in the mouth. Or in the eyes. That “full in the eyes” phrase has me thinking again of Dylan and Lanois’s “staring eyes” approach at Soniat, facing off in their kitchen-table collaborations. “Shooting Star” isn’t only about other artists, it’s also about Dylan confronting his own art and legacy. He had little cause in 1989 to suspect that he was only at the midpoint of his career. Indeed, by the end of the eighties he may well have felt all washed up. That self-doubt comes through in the second verse:

Seen a shooting star tonight

And I thought of me

If I was still the same

If I ever became

What you wanted me to be

Did I miss the mark?

Overstep the line

That only you could see?

Seen a shooting star tonight

And I thought of me

Who is the “you” addressed in this verse. It could have a number of antecedents, from a lover to God to the listener. But in the context of the “Creole Trilogy,” I believe Dylan has Lanois at least partially in mind, the producer’s staring eyes and demanding ears that scrutinized the artist’s latest efforts and pushed him to reach for more. Near the end of the chapter, Dylan gives major credit to Lanois for the album’s artistic success, specifically crediting the producer with seeing things the artist could not: “A lot of what he did was pure genius. He steered the record with deft turns and jerks, but he did it. He stood in the bell tower, scanning the alleys and rooftops. My limited vision didn’t permit me to see all around the thing” (220).

Acadie

Lanois helped guide Dylan into new sonic territory, and the influence was mutual. For his part, Dylan led Lanois toward excavating more personal terrain in his own songs. “I believe my time with Bob inspired me to look at my own life stories,” he writes in Soul Mining. “Enough time had passed, and my geographical distance brought me clarity, and my songs poured out” (109). Lanois had offered similar advice a couple years earlier to Robertson. “Robbie Robertson’s storytelling ability was always magic to me. I loved listening to Robbie talk about his times in Arkansas with his buddy Levon Helm. I pushed Robbie to go into the labyrinth of the backwater swamp: dimly lit one-room shacks, sparsely spread out on the river’s edge; one story led into another” (79). The result was “Somewhere Down the Crazy River,” the most mesmerizing song from their 1987 album. The river is the Mississippi if you’re consulting maps or navigating by the Southern Cross. But if your gaze is fixed instead on the Northern Lights, then you’re swimming upstream on the river of time.

This crazy river serves as a lifeline between Canada and the United States, meandering through the heartland, past Arkansas and Memphis, down to New Orleans and the Mississippi Delta, the Tchoupitoulas and the French Quarter, carrying on its currents the best of American roots music. On the surface level, “Somewhere Down the Crazy River” is a memory song about one young Canadian’s first exposure to the American South, its distinct people, inspirational music, and illicit pleasures. On a deeper level, however, Robertson’s journey is emblematic of the Acadian exodus out of Canada down to Louisiana, where French-Canadians adapted through generations of creolization into Cajuns. The word “Cajuns” is in fact a corruption of the word “Acadians.” In Acadie, Lanois deliberately and beautifully retraces that journey, traveling both up and down the crazy river, leading him back in time and history to his Canadian past and forward to his adopted home in New Orleans.

“The Ottawa River is the dividing line between Ontario and Quebec, or between English- and French-speaking Canada,” begins Lanois’s memoir. “My parents lived on the Quebec side of the river, the French side, in a government housing community by the name of Project Dusseau. We were French Canadian. I spoke only French until the age of ten” (3). Lanois’s bilingual proficiency is reflected on Acadie, where he shifts fluently back and forth between English and French. Not only is he French Canadian, but he is also descended from the native inhabitants of Canada. In 2017, he participated in a concert sponsored by APTN (Aboriginal Peoples Television Network) celebrating Canada’s Aboriginal Day. In a piece for the Montreal Gazette, Lanois said, “I have aboriginal blood on both sides of the family. It’s pretty watered down, Micmac and Algonquin. A lot of people say that [they’re part native], but with the French in Canada, it’s normal—everybody is practically Métis.” Lanois embodies multiple identities, and he weaves this hybridity into the highly intertextual songs of Acadie.

The opening track, “Still Water,” establishes the cultural setting of the album. “All the images in my head were clearly Canadian. The Grand River cutting through the Six Nations reserve, the native eyes that I had stared into, eyes with alcohol in them, were the eyes of inspiration for my song ‘Still Water,’ a song that explains departure, but a song that is also there for the return” (109). Note that Robbie Robertson’s mother was Mohawk and Cayuga, and her family lived on the Six Nations reserve. The experiences captured in “Still Water” are not autobiographical for Lanois, but they are specifically Canadian. “I’m going to where the boats go by / Caledonia river flow so wide” places the song on the Grand River which flows through Caledonia in Ontario. From a Canadian musical perspective, this place is inevitably associated with the song “Caledonia Mission,” written by Robbie Robertson and sung by Rick Danko on Music from Big Pink. Robertson recalls, “There was a Canadian town called Caledonia we would drive by on the way to Six Nations, and something about that place conjured up strange images and a story of estrangement and solitude in my imagination. Mostly I just like the name. I knew Rick’s vocal sound would be good for this song. Even the town where he was born and raised wasn’t far from Caledonia, so it felt like the right fit” (274).

Lanois has another culturally specific reference in mind for “Still Water.” There is a tradition dating back to the 19th century of Mohawks working on high-rise construction projects like bridges and skyscrapers in Canada and the United States. “Still Water” profiles a native construction worker on the gigantic Caledonia Bridge spanning the Grand River. Without spelling it out, he may also be conjuring up memories of the disastrous 1907 collapse of the Quebec Bridge over the Saint Lawrence River. Over 80 workers died, 35 of whom were Mohawk from Kahnawake and Akwesasne near the Canadian-U.S. border. The singer laments,

Going to where the rain falls

Look for my brother

Look for my brother

Going to where the rain falls

Caledonia river far away

Still water, laying over

Still water, lay my body down

Still water, laying over

Caledonia river far away

He appears to be laying ironwork over the still water, but his thoughts lie elsewhere with his absent (dead?) brother. The lyrics also invite a still darker interpretation: If the still water is “laying over” the singer, does that mean he drowned in the river? The melancholic “sky walker,” working construction on the Caledonia Bridge, seems at the very least to be contemplating suicide, disturbing that still water by taking a fatal plunge into the Grand River below.

The river continues to flow and the eyes continue to gaze in the next song, “The Maker”:

Oh, oh, deep water

Black and cold like the night

I stand with arms wide open

I’ve run a twisted line

I’m a stranger in the eyes of the Maker

Lanois explains in his memoir that the initial inspiration for this song came in Ireland while producing U2’s The Unforgettable Fire:

Images of the River Liffey in Dublin in 1984, and walking home every night along its banks, the river almost spilling its black ink water into the dockland warehouse area. My home was the Gresham Hotel. I was working with U2 on The Unforgettable Fire. My route home would take me by the two Guinness ships, often docked by the studio, having their bellies filled, readying for the twice-a-week Guinness transport to Liverpool. The black calmness of the river at night made it look like a mirror. On a moonlit night I could see my reflection, and when I listened the river spoke to me. (194)

This anecdote reminds me of the backstory to Yeats’s “The Lake Isle of Innisfree.” The Irish poet was living in London at the time he wrote the poem. One day he was standing by a fountain in Regent’s Park, and the sound of splashing water transported him back to the rural Sligo of his youth. The prodigal son heard the call to return to his homeland:

I will arise and go now, for always night and day

I hear lake water lapping with low sounds by the shore;

While I stand on the roadway, or on the pavements grey,

I hear it in the deep heart’s core.

Similarly, the black water of the Liffey transported Lanois back to the Canada of his childhood. But he followed the river of time even further back into Acadian history.

In the second verse of “The Maker,” the singer has a vision that stretches back to the 18th century and the French and Indian War:

And from across the great divide

In the distance I saw the light

Jean-Baptiste

Walking to me with the Maker

I suspect this is a reference to Jean-Baptiste Cope (aka Major Cope), a Mi’kmaq chief allied with the French Acadians in their struggle against the British. The song’s bridge reinforces this historical source:

My body is bent and broken

By long and dangerous sleep

I can’t work the fields of Abraham

And turn my head away

I’m not a stranger in the hands of the Maker

The thing he can’t turn away from is his Acadian roots, as evidenced by the allusion to the Battle of the Plains of Abraham, the decisive turning point in the British defeat and expulsion of the Acadians. Note that the first verse says that the singer, far away from home in Dublin, is a stranger in the eyes of the Maker. But after reconnecting with his cultural inheritance, the prodigal son is no longer a stranger in the hands of the Maker.

The creole intertextuality of “The Maker” culminates in a final verse that conjures up images of a new home in New Orleans:

Brother John

Have you seen the homeless daughters

Standing there with broken wings?

I have seen the flaming swords

There over East of Eden

Burning in the eyes of the Maker

“Brother John” name-checks the song “Brother John,” the opening track on The Wild Tchoupitoulas. The song was written by Cyril Neville about Scarface John Williams, a New Orleans singer and Big Chief of the Apache Hunters Mardi Gras Indians, who was stabbed to death in a barroom fight in 1972. In case there’s any doubt about the Neville connection, Lanois dispels it by bringing in Aaron Neville to sing the last three lines quoted above. Those lines concern another expulsion: Cain’s eviction East of Eden after murdering Abel, dooming the outlaw to a life of perpetual exile. As I argue in “Dylan’s Holy Outlaws,” the myth of Cain is vitally important to Dylan [cf. “Every Grain of Sand”: “Like Cain I now behold this chain of events that I must break”]. On an album notable for its many layers of allusion, inspiration, and collaboration, “The Maker” stands out as the most intertextually rich song on Acadie.

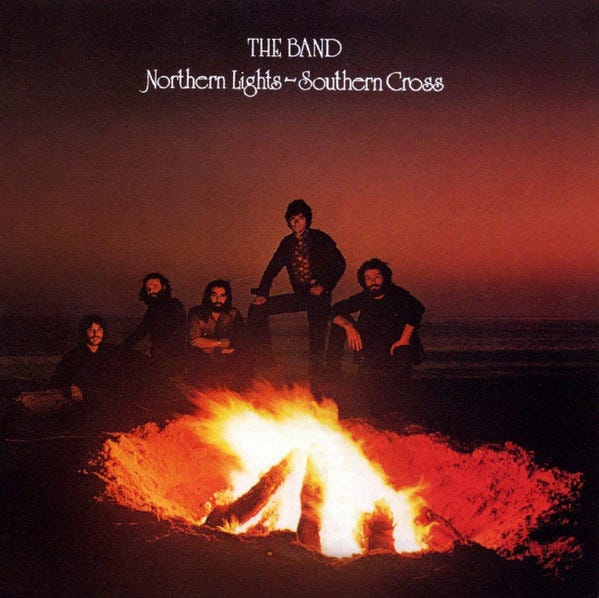

One source exerts a stronger influence than any other: “Acadian Driftwood,” written by Robertson, sung by Manuel, Danko, and Helms for the album Northern Lights—Southern Cross, and reprised for The Last Waltz with cameos by fellow Canadians Neil Young and Joni Mitchell.

The author of “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down” takes up a lost cause closer to home, memorializing the Acadian defeat and displacement after the Battle of the Plains of Abraham:

The war was over

And the spirit was broken

The hills were smokin’

As the men withdrew

We stood on the cliffs

Oh and watched the ships

Slowly sinkin’ to their rendezvous

They signed a treaty

And our homes were taken

Loved ones forsaken

They didn’t give a damn

Try to raise a family

End up an enemy

Over what went down on the Plains of Abraham

This battle and its resulting exodus point the way from Acadia to Louisiana, just as surely as “Acadian Driftwood” rides the current downriver to Acadie. Robertson maps it all out for Lanois, from the diaspora to New Orleans to the inner compulsion to reverse the journey back home:

We worked in the sugar fields

Up from New Orleans

It was evergreen

Up until the flood

You call it an omen

Point ya where ya goin’

Set my compass north

I got winter in my blood

The curse of Cain—forever restless and uprooted, on the run and never belonging anywhere for long—is also the birthright of the Acadians. As Robertson puts it in the chorus,

Acadian driftwood

Gypsy tailwind

They call my home

The land of snow

Canadian cold front

Movin’ in

What a way to ride

Oh what a way to go

This same fugitive spirit pervades the songs of Acadie and springs from the same personal, cultural, and historical sources. Stuck inside New Orleans with the Acadian blues again.

One of the most interesting things I learned while researching this album is that Lanois actually wrote a song in 1989 called “Acadie” but didn’t release it. The ballad recounts the Battle of the Plains of Abraham from the perspective of a soldier serving under French commander Louis-Joseph de Montcalm. Forced to flee, he and his lover set their sails southward with a mixture of gratitude for their American sanctuary and regret for their lost homeland. Robbie Robertson and Neil Diamond would both approve of the song’s final lines:

Oh no, no, Francine don’t cry

Dry your eyes for you are now

Far away from the land of Acadie

In Louisiana where we will be free

It’s Lanois’s title song, and he leaves it off the album—what a Dylanesque move! His motivations for the exclusion doubtlessly resemble Dylan’s familiar calculus. Maybe he never found a take he was fully satisfied with. Maybe he decided that the didactic historical song didn’t fit well alongside other more personal and subtle songs. Or maybe Lanois thought “Acadie” revealed too much about the inspirations and intentions of the album. So he suppressed it, but then embedded similar ideas in the surviving songs in more nuanced ways. In any case, the outtake “Acadie” suggests that one lesson Lanois learned from his apprenticeship with Dylan is that the songs you leave off an album are sometimes as important as the ones you put on it.

The final track on Acadie is “Amazing Grace,” bringing Lanois back full circle to his work with the Neville Brothers. This song has been a mainstay in Aaron Neville’s setlists for many years. He laid down a vocal track for “Amazing Grace” during the Yellow Moon sessions, but the song didn’t make it onto the record. Rather than abandon it outright, however, Lanois kept working on it, eventually producing the strangest version of this classic gospel that I’ve ever heard. “Amazing Grace” is made strange in the hands of the record maker Lanois. Neville’s angelic voice is obscured way back in the mix, buried beneath eerie sound effects that sound partially like a dinghy on the night sea and partially like a satellite drifting through deep space. It comes across like a duet between Neville’s voice and Lanois’s sonic wizardry. The familiar hymn becomes radically defamiliarized. Eventually, the music picks up speed and starts to cohere into a soundscape reminiscent of Lanois’s work on The Joshua Tree. In fact, to my ears it sounds at times so much like “I Still Haven’t Found What I’m Looking For” that it borders on self-pastiche. And that’s a really interesting choice, since the lyrical message of “I Still Haven’t Found What I’m Looking For” is diametrically opposed to the hymn’s famous refrain:

Amazing Grace, how sweet the sound

That saved a wretch like me

I once was lost, but now I’m found

Was blind, but now I see

In other words, when Aaron Neville sings “Amazing Grace,” he declares that he has found what he’s looking for. He is no longer searching, no longer lost. Lanois gradually brings up Neville’s vocal in the mix, as if the stranded voice has made its way out of the fog and into the light. In “The Maker,” the singer declared:

I could not see

For the fog in my eyes

I could not fee for the fear in my life

And from across the great divide

In the distance I saw the light

By the end of Acadie, Lanois enlists a different singer, enshrouds him in a fog of sound, but then lifts the cloud and leads him into clarity. It’s a strikingly hopeful way to end an album largely focused on restlessness, exile, and wandering. You might even say that Lanois’s placement of this song as the closer represents a kind of homecoming.

I’ll resist my typical hyper-fixation with words and close “Creole Trilogy” with an instrumental. Lanois began playing “Sonho Dourado” (Portuguese for “Golden Dream”) live in concert back in 1989. It didn’t appear on Acadie, but it was eventually included on the 2004 soundtrack for Billy Bob Thornton’s 2004 film Friday Night Lights. When Acadie was reissued (as the “Goldtop Edition”) in 2008, it included some outtakes and alternate takes. The highlight is a gorgeous instrumental labeled “Early Dourado Sketch.” Click the link and listen closely. Don’t you hear “Shooting Star”? They aren’t identical twins, but there sure is a close family resemblance. Call them Cajun cousins.

Did Dylan hear this sketch and adapt it for “Shooting Star”? Or did Lanois produce “Shooting Star” and like it so much that, consciously or unconsciously, it wormed its way into a guitar piece that would eventually get developed and repurposed? I don’t know the precise timeline and so can’t conjecture about the exact provenance. But such inquires miss the larger point. The atmosphere in New Orleans in 1989 was one of creativity, experimentation and free exchange: try this—>see what you can do with that—>what if we did it this way—>this isn’t quite right for my thing, but maybe you can use it for your thing—>throw it in the pot and let’s see what we can cook up. This spirit of mutual collaboration is what comes through most strongly in relistening to Yellow Moon, Oh Mercy, and Acadie and reimagining them as a “Creole Trilogy.”

Works Cited

Bono. Interview with Bob Dylan. Hot Press (24 August 1984), https://www.hotpress.com/music/on-this-day-in-1984-bob-dylan-was-joined-on-stage-at-slane-by-bono-and-van-morrison-22860605.

The Band. “Acadian Driftwood.” Northern Lights—Southern Cross. Capitol, 1975.

---. “I Shall Be Released.” Music from Big Pink. Capitol, 1968.

Diamond, Neil. “Dry Your Eyes.” Beautiful Noise. Columbia, 1976.

Dunlevy, T’Cha. “Aboriginal Day: Daniel Lanois Stands by ‘Native and Aboriginal Compadres.” Montreal Gazette (20 June 2017), https://montrealgazette.com/entertainment/music/aboriginal-day-daniel-lanois-stands-by-native-and-aboriginal-compadres#:~:text=%E2%80%9CI%20have%20aboriginal%20blood%20on,%E2%80%94%20everybody%20is%20practically%20M%C3%A9tis.%E2%80%9D.

Dylan, Bob. Chronicles, Volume One. Simon & Schuster, 2004.

---. “Every Grain of Sand.” Shot of Love. Columbia, 1981.

---. “Man in the Long Black Coat.” Oh Mercy. Columbia, 1989.

---. “Shooting Star.” Oh Mercy. Columbia, 1989.

Flanagan, Bill. Interview with Bob Dylan. JamBase (13 February 2015), https://www.jambase.com/article/bob-dylan-clarifies-some-points-made-during-speech.

Fricke, David. “The Making of Dylan’s ‘Love and Theft.’” Rolling Stone (27 September 2001). Every Mind Polluting Word: Assorted Bob Dylan Utterances, edited by Artur Jarosinski, Don’t Ya Tell Henry, 2006, pp. 1318-19.

Gilroy, Paul. The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness. Harvard University Press, 1993.

Lanois, Daniel. “Acadie.” Unreleased.

---. “Amazing Grace.” Acadie. Opal, 1989.

---. “The Maker.” Acadie. Opal, 1989.

---. “Still Water.” Acadie. Opal, 1989.

Lanois, Daniel, with Keisha Kalfin. Soul Mining: A Musical Life. Faber and Faber, 2010.

The Neville Brothers. “My Blood.” Yellow Moon. A&M, 1989.

---. “Sister Rosa.” Yellow Moon. A&M, 1989.

---. “With God on Our Side.” Yellow Moon. A&M, 1989.

Ritz, David. The Brothers: An Autobiography by Art, Aaron, Charles, and Cyril Neville. Little, Brown and Company, 2000.

Robertson, Robbie. “Fallen Angel.” Robbie Robertson. Geffen, 1987.

---. Testimony. Crown Archetype, 2016.

Yeats, William Butler. “The Lake Isle of Innisfree.” Poetry Foundation, https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/43281/the-lake-isle-of-innisfree.

Daniel Lanois also mixed/engineered Raffi's classic (and platinum) 1980 children's album, "Baby Beluga."

Wonderful unpacking. I thoroughly enjoyed this read. When I think of this era, I can't help but think of Emmylou Harris and the swampy Wrecking Ball.