This is my 50th post for Shadow Chasing! Whether you’ve been reading since the beginning two and a half years ago, or have joined at some point farther down the line, I greatly appreciate your interest in my work. If you value this site enough to support it financially, please consider signing up for a paid membership of $5 per month or $50 per year.

Or if you’d like to help me celebrate this milestone with a one-time donation, please click the Buy Me a Coffee button below. Now on with the show.

In Bob Dylan’s Nobel Lecture, he reflects upon the process of transforming old songs into new ones:

By listening to the early folk artists and singing the songs yourself, you pick up the vernacular. You internalize it. […] I had the vernacular down. I knew the rhetoric. None of it went over my head—the devices, the techniques, the secrets, the mysteries—and I knew all the deserted roads that it traveled on, too, I could make it all connect with the current of the day. When I started writing my own songs, the folk lingo was the only vocabulary that I knew, and I used it.

How exactly does this metamorphosis work and what are the results? Let’s take some specimens into the lab to find out. For this experiment, we’ll be dissecting demon lover ballads. The idea is to analyze two artists who have repeatedly turned to the same old songs, internalized the vernacular, and translated the tradition into new forms that speak to contemporary concerns.

The first artist is of course Bob Dylan. We’ll listen to his covers of two demon lover ballads—“House Carpenter” in this first installment, and “Blackjack Davey” in the next—as well as several original songs adapted from this tradition. The second artist is the writer Shirley Jackson. We’ll explore two of her demon lover stories: “The Daemon Lover” in this first installment, and “Elizabeth” in the next. I want to put Jackson’s stories into conversation with Dylan’s songs and consider how they each internalize and historicize this particular ballad tradition.

The Demon Lover Tradition

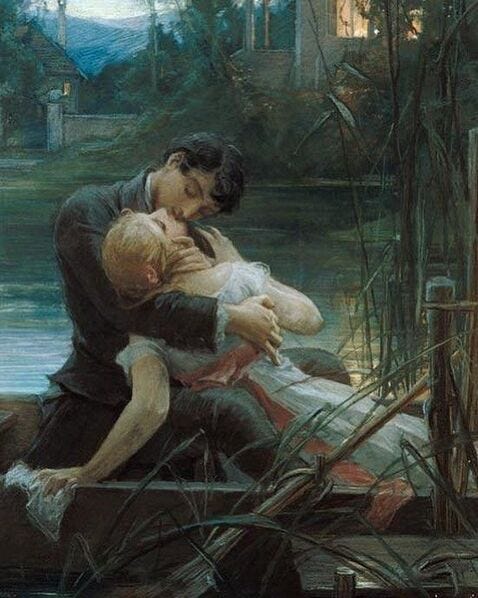

Andrew Muir has done a lot of interesting research into Dylan and the Scottish and English ballad traditions. He explored that subject in his book The True Performing of It: Bob Dylan & William Shakespeare, and he extends the project in his Substack site More True Performing. In his inaugural essay, “‘Our wells are deep’: Dylan, Shakespeare and Broadside Ballads,” he notes, “there is a recurring theme in many of these ballads of the temptations and dangers of infidelity, especially when it involves a woman leaving her husband for a mysterious lover. Numerous ballads play variants on this as a retelling of the ‘Eve story,’ which always leads to a catastrophic ending, the inevitable ‘fall.’” One of the classic examples is Child Ballad No. 243, a song about a seductive demon lover.

In his landmark five-volume compendium English and Scottish Popular Ballads, Francis James Child traces six variations of the ballad “James Harris (The Dæmon Lover).” The song evolved significantly over the years, particularly after it made the transatlantic voyage. It is known by a variety of alternate titles, including “A Warning to Married Women,” “The Ship-Carpenter’s Wife,” or, most popularly in America, “House Carpenter.” In the broadside from Samuel Pepys’s collection published in 1685, he offers this plot summary:

Jane Reynolds and James Harris, a seaman, had exchanged vows of marriage. The young man was pressed as a sailor, and after three years was reported as dead; the young woman married a ship-carpenter, and they lived together happily for four years, and had children. One night when the carpenter was absent from home, a spirit rapped at the window and announced himself as James Harris, come after an absence of seven years to claim the woman for his wife. She explained the state of things, but upon obtaining assurance that her long-lost lover had the means to support her—seven ships upon the sea—consented to go with him, for he was really much like a man. “The woman-kind” was seen no more after that; the carpenter hanged himself. (qtd. Friedman 13-14)

The first published version to bear the title “The Dæmon-Lover” was the fifth edition of Sir Walter Scott’s The Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border (1812). The lover’s “cloven foot” marks him as the devil, as does his ominous threat about their ultimate destination:

“O whaten a mountain is yon,” she said

“All so dreary wi’ frost and snow?”

“O yon is the mountain of hell,” he cried,

“Where you and I will go” (Scott 431)

In The Folk Songs of North America in the English Language (1960), Alan Lomax situates “House Carpenter” historically and ideologically within its transplanted American context. He interprets the song as an instrument for reinforcing patriarchal values by punishing women who stray from their domestic duties:

The song was sung by women who had come with their men to Pennsylvania and the lowlands—by their daughters who lived and died hard in mountain log cabins—in turn, by their daughters sinking deeper in the squalor of backwoods life. For them, the easiest path out of a bad marriage was to run off with another man. Yet that way, the road of adventure, they would lose what they had and die in guilt, far from their children. (Lomax 170)

He believed that the “House Carpenter” was so popular because it “represented the deepest emotional preoccupations of women who lived within the patriarchal family system” (169). According to Lomax,

No fantasy could have been better calculated to reinforce the Calvinist sexual morality of our ancestors. It counselled them to stick to what they had. Indeed, no women have ever been more long-suffering, or more hard-working helpmates, yet they did enjoy songs about women who rebelled, especially if the rebels were punished in the last stanza. (17)

This internal tension within the song—indulging liberation but also punishing it—animates both Dylan’s songs and Jackson’s fiction about demon lovers.

Dylan’s “House Carpenter” and Its Descendants

In Dylan’s Daemon Lover: The Tangled Tale of a 450-Year Old Pop Ballad, Clinton Heylin sets the scene for Dylan’s first known performance of the song:

At approximately five o’clock on Wednesday, November 22, 1961, in a studio on the seventh floor of one of Columbia’s Manhattan locales, a twenty-year old Robert Zimmerman was preparing to cut the last song at the sessions for his debut album […] The song with which he wrapped up the sessions was not one he is known to have previously tackled (even in his friends’ living-rooms), nor is there another recording extant from his “folk” days. (Heylin 1).

“House Carpenter” was inexplicably left off the debut album and wasn’t officially released until the first Bootleg Series. Although there’s no concrete evidence of him playing the song before 1961, Dylan certainly would have been very familiar with it. He probably first encountered it on the Harry Smith Anthology in a recording by Clarence Ashley. A number of musicians on the folk circuit were playing “House Carpenter” when he arrived on the scene, such as Joan Baez, Dave Van Ronk, Paul Clayton, Jean Ritchie, and Doc Watson.

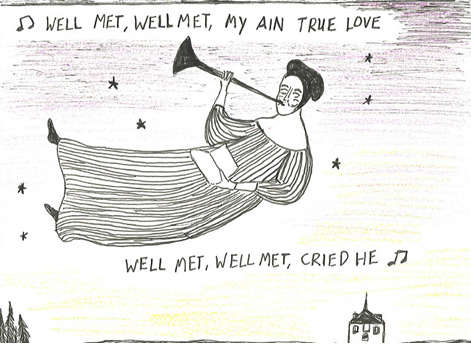

Dylan opens his 1961 performance with a spoken introduction: “Here’s a story about a ghost come back from out the sea, come to take his bride away from the house carpenter.” Even before the lyrics kick in, we are already put on notice that we’re entering the supernatural.

“Well met, well met, my own true love”

“Well met, well met,” cried she

“I’ve just returned from the salt, salt sea

And it’s all for the love of thee”

The carpenter’s wife puts up brief resistance, but soon she agrees to leave her husband and babies behind and escape with the demon lover. Dylan ratchets up the drama with his emotive vocals and driving guitar. You can hear the mounting dread as the wife asks,

“Oh what are those hills yonder, my love

They look as white as snow”

“Those are the hills of heaven, my love

You and I’ll never know”

“Oh what are those hills yonder, my love

They look as dark as night?”

“Those are the hills of hell-fire, my love

Where you and I will unite”

In the climactic final verse, the wife pays for her infidelity with death and damnation: “When the ship all of a sudden, it sprung a leak / And drifted to the bottom of the sea.” Drowning is Dylan’s preferred method for punishing wickedness during this early period (e.g., “The Times They Are A-Changin’” and “When the Ship Comes In”). But it remains to be seen whether the ex-wife is better off spending eternity with her demon lover than she would have been stuck with a life sentence as a wife and mother.

As much as I like the 1961 version, I love the 1970 “House Carpenter” on Another Self Portrait even more. Dylan’s sings in a higher pitch, which to my mind sounds like he’s taking the woman’s side, perhaps channeling Joan Baez or Jean Ritchie. The song benefits from additional musicians—David Bromberg on acoustic guitar and Al Kooper’s swirling piano, plus Dylan’s piercing harmonica—sounding every bit like the house band on a sea cruise to hell.

Within the morality play cosmos of the song, the husband’s occupation is no coincidence. Like Jesus, he is trained as a carpenter. When his wife chooses to run off with James Harris, she is effectively choosing the Demon Lover over the Carpenter, i.e., Evil over Good. However, it’s not entirely clear that Dylan shares this moral judgment, at least not in 1970. For instance, he adds a new lyric that didn’t appear in the 1961 version. He hints at where his allegiances lie when he asks in the woman’s voice:

“If I forsake my house carpenter

And fly away with thee

What have you got to maintain me upon

And keep me from slavery?”

Only after he reassures her of his wealth does she accept the bargain and agree to flee with him. But the word that stands out to me in that verse is slavery. Is she suggesting that the alternative to leaving with the demon lover is remaining home in captivity? If so, then the husband’s occupation seems significant for a different reason: as a carpenter, he knows how to build sturdy walls for keeping his wife imprisoned. Sung from this perspective, “House Carpenter” seems less about risking damnation and more about longing for emancipation.

Freedom is the dominant theme of Dylan’s songs from the mid-sixties inspired by “House Carpenter,” though the shadow of death also lurks nearby. Take for instance “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue,” the closing track on Bringing It All Back Home (1965).

The opening lines suggest someone hastily escaping their home, much like the wife in “House Carpenter”: “You must leave now, take what you need, you think will last / But whatever you wish to keep you better grab it fast.” The singer’s invitation to Baby Blue echoes the demon lover addressing the wife: “‘Forsake, forsake your house carpenter / And come away with me.’” Leaving her husband also means leaving her kids without a mother, which might lie behind Dylan’s cryptic image: “Yonder stands your orphan with his gun / Crying like a fire in the sun.”

The final verse of “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue” resonates strongly with “House Carpenter.” Dylan adopts the persona of the demon lover and urges “you”—both the wife and the song’s listener—to cut ties with home and be free. The potential rewards are high, but so are the risks—life or death:

Leave your stepping stones behind, something calls for you

Forget the dead you’ve left, they will not follow you

The vagabond who’s rapping at your door

Is standing in the clothes that you once wore

Strike another match, go start anew

And it’s all over now, Baby Blue

This thrilling but dangerous invitation is what Joyce Carol Oates was responding to in “Where Are You Going, Where Have You Been?” The story focuses on a teenager named Connie who is seduced by a suave killer named Arnold Friend. In a 2015 piece for the Wall Street Journal, she reflected on why she chose to dedicate this story to Bob Dylan. “In 1965, I was writing my short story ‘Where Are You Going, Where Have You Been?” when Bob Dylan’s Bringing It All Back Home was released. The album was riveting, but the song ‘It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue’ was especially moving and relevant.”

Oates recalls that “the song’s soul and poetic rhythm were seductive,” and these were qualities she wanted to emulate in her story. For her, the song was a model of “renewal and beginning again,” but also a “powerful evocation of losing control, of losing everything.” For Connie and Baby Blue and the carpenter’s wife, the price of freedom is nothing less than everything. Oates concludes, “Essentially, the song is about mortality. In my story, which was first published in 1966 and many times reprinted, the life that my teenage character knew is about to end. It seemed fitting to dedicate my story to Bob Dylan.”

The other song on Bringing It All Back Home that is most indebted to “House Carpenter” is “Mr. Tambourine Man.” I’ve long been aware of the song’s allusions to the Pied Piper of Hamelin, but I’ve only recently tuned into its echoes of “House Carpenter.”

Let me defamiliarize this familiar song for you. The title character is gendered masculine, but the first-person narrator is never identified by sex. Could Dylan be adopting a woman’s perspective in “Mr. Tambourine Man”? I wonder if he’s seeing through the eyes and singing in the voice of the house carpenter’s wife, or at any rate a modern woman going through much the same experience. He’s done it before. The miner’s wife Dylan embodies in “North Country Blues” is stranded permanently at home, but the carpenter’s wife in “Mr. Tambourine Man” is willing to risk everything to go somewhere new and become someone else.

The singer paces through another sleepless night, scanning the horizons for some sign of hope, plotting her next move. Notice that “Mr. Tambourine Man,” like “House Carpenter,” dangles the possibility of escape by ship: “Take me on a trip upon your magic swirlin’ ship.” I always read that as some kind of psychedelic reference, but it works just as well as a description of the demon lover’s phantom ship. She makes her way out to the seashore at the end, which makes sense if she’s “escapin’ on the run” to catch a getaway boat. She dances her way down to the beach and waves goodbye to the life she is leaving behind: “Yes, to dance beneath the diamond sky with one hand waving free / Silhouetted by the sea, circled by the circus sands.” The ending acknowledges that the cost of freedom may be death. It sounds like a premonition of the drowning at the end of “House Carpenter”: “With all memory and fate driven deep beneath the waves.” Some are tambourine men, some are carpenter’s wives. Hey, Mr. Demon Lover, play a song for me.

The demon lover myth has proven as pliable as it is durable, attracting a remarkable range of treatments over the years. For a fantastic recent example, check out the queer graphic memoir “The Daemon Lover” by Coyote Shook, posted in a 2022 issue of Sonora Review. I’ll include several illustrations by Shook scattered throughout the final section of this piece.

Shirley Jackson Background

Now let’s turn our attention to Shirley Jackson as another artist who adapted the demon lover myth, in her case explicitly from the perspective of mid-century American women. If you’ve read anything by her, chances are its her famous story “The Lottery,” about a scapegoat ritual that persists into modern times, or The Haunting of Hill House, a slim but hugely influential novel that establishes many prototypes for the haunted house genre.

Jackson was born in San Francisco in 1916. She attended the University of Rochester and then transferred to Syracuse University, where she graduated in 1940. There she met and married Stanley Edgar Hyman, who became a prominent literary critic and legendary professor at Bennington College. The couple had four children, primarily raised by their mother, but Jackson also used the kids for writing material, publishing humorous accounts of domestic life in Life Among the Savages (1953) and Raising Demons (1957), which were very popular at the time. But Jackson led a double life as a writer of strange, uncanny, gothic tales of psychological horror for which she is now best known, including Hangsaman (1951), The Haunting of Hill House (1959), and We Have Always Lived in the Castle (1962). She died in 1965 at the age of only 48.

Although she had a troubled relationship with her philandering husband, Hyman was her most dependable reader and the biggest champion of her work. After her untimely death, he wrote: “‘I think that the future will find her powerful visions of suffering and inhumanity increasingly significant and meaningful, and that Shirley Jackson’s work is among the small body of literature produced in our time that seems apt to survive’” (qtd. Franklin 9). History has proven him right.

Jackson’s fiction is firmly rooted in the historical conditions of post-WWII America. Her critique of the suffocating expectations placed upon women in “the long 1950s” (1945-1963) anticipates in many ways The Feminine Mystique (1963), Betty Friedan’s landmark work of second-wave feminism. Friedan opens her book with a flickering awareness of “the problem that has no name”:

The problem lay buried, unspoken, for many years in the minds of American women. It was a strange stirring, a sense of dissatisfaction, a yearning that women suffered in the middle of the twentieth century in the United States. Each suburban wife struggled with it alone. As she made the beds, shopped for groceries, matched slipcover material, ate peanut butter sandwiches with her children, chauffeured Cub Scouts and Brownies, lay beside her husband at night—she was afraid to ask even of herself the silent question—“Is this all?” (11, emphasis added)

Jackson’s characters are similarly plagued by pressures to meet unrealistic and unfulfilling ideals for proper behavior, what has been called “The Cult of True Womanhood” in the 19th century and which Friedan refers to as “The Feminine Mystique”:

The suburban housewife—she was the dream image of the young American women and the envy, it was said, of women all over the world. The American housewife—freed by science and labor-saving appliances from the drudgery, the dangers of childbirth and the illnesses of her grandmother. She was healthy, beautiful, educated, concerned only about her husband, her children, her home. She had found true feminine fulfillment. As a housewife and mother, she was respected as a full and equal partner to man in his world. She was free to choose automobiles, clothes, appliances, supermarkets; she had everything that women ever dreamed of. (13)

Friedan summarizes: “In the fifteen years after World War II, this mystique of feminine fulfillment became the cherished and self-perpetuating core of contemporary American culture” (14).

Jackson outwardly seemed to conform to these gender expectations in her personal life as a wife, mother, and homemaker. In her fiction, however, she offers a nuanced and piercing critique of the patriarchy. She takes the ultimate symbol of femininity—the home, the hearth, the domestic sphere—and depicts it as a haunted house: a danger zone where women feel trapped and tortured by demons within and without.

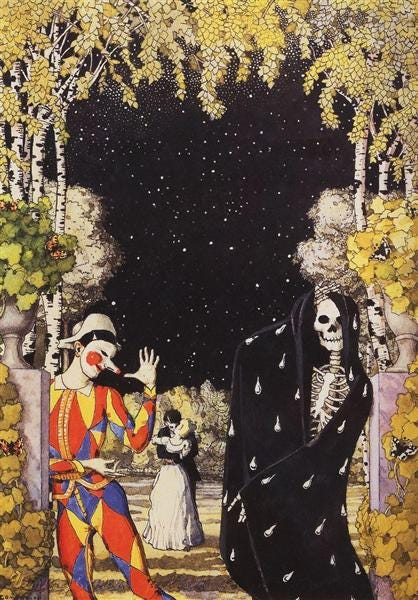

Jackson also dramatizes the desire for escape from the haunted house, and this accounts for her enduring attraction to the demon lover myth. Biographer Ruth Franklin notes that, as an adolescent, Jackson was deeply drawn to the commedia dell’arte figure of Harlequin, which gradually morphed into a fascination with James Harris:

Harlequin represented to Jackson an earlier, more innocent version of the “daemon lover” figure who would later appear in the Lottery collection and elsewhere: a character from one of the Child Ballads, also known as James Harris, who seduces a woman only to reveal, when it is too late, that he is the devil in disguise. Like a less sinister daemon lover, Harlequin offers escape from the ordinary world into a colorful realm of pastoral landscapes and freedom. (52)

Jackson enlisted Harlequin and James Harris as the Mr. Tambourine Men of her fiction.

Like Dylan, she knew the demon lover ballads extremely well. Her first novel, The Road Through the Wall (1948), contained a biographical sketch written by Hyman. He listed among her many talents: “She plays the guitar and sings five hundred folk songs . . . as well as playing the piano and the zither” (qtd. Franklin 217). She published her first collection of short stories in 1949 and called it The Lottery or, The Adventures of James Harris. In case there were any doubt about the source of that subtitle, she makes it clear in the book’s epilogue, where she reproduces the final eight verses of “James Harris, The Daemon Lover” (Child Ballad No. 243), concluding with the verses about heaven, hell, and drowning in the sea (Jackson 305-6).

Jackson approaches The Lottery like a concept album, with individual stories bound together by the demon lover myth and recurring appearances by James Harris. Franklin explains:

But she also had another unifying concept in mind. The collection would include several extremely accomplished stories that she had written the previous year but had not yet published (The New Yorker turned them all down), which would serve as cornerstones of the book. They all worked along a similar model: an apparently mundane situation—a dinner guest, a visit to the dentist—that takes a Hawthorne-like detour, sharp yet subtle, into the uncanny. (252-53)

Jackson’s “The Daemon Lover”

Jackson’s most direct adaptation of the myth appears in the second story of the volume, “The Daemon Lover.” If you’d like to hear it in Jackson’s own voice, listen to her 1960 recording for Folkways:

“The Daemon Lover” follows an unnamed and increasingly frantic woman on the day she plans to marry James Harris. The protagonist gets jilted and the reader does as well: Jamie (as she calls him) never makes an appearance in the story. This is a significant variation on the demon lover myth. Jackson’s James Harris doesn’t abduct the woman he targets, stealing her from her husband and children. Quite the contrary. The main character is a lonely and completely dissatisfied woman who desperately pursues him as her would-be savior.

In fact, it’s not entirely clear that James Harris actually exists. He could be a wish-fulfillment fantasy. “The Daemon Lover” opens with this meandering sentence, crossing back and forth between the threshold of sleeping and waking:

She had not slept well; from one-thirty, when Jamie left and she went lingeringly to bed, until seven, when she at last allowed herself to get up and make coffee, she had slept fitfully, stirring awake to open her eyes and look into the half-darkness, remembering over and over, slipping again into a feverish dream. (9)

The story that follows tracks the protagonist rushing all over town in pursuit of James Harris, but it is equally possible that she never leaves dreamland.

This strategy is something that Jackson and Dylan have in common. Think about how many of his songs take place in the nether region between darkest night and early dawn. “And the silent night will shatter from the sounds inside my mind” [“One Too Many Mornings”]; “Ain’t it just like the night to play tricks when you’re tryin’ to be so quiet” [“Visions of Johanna”]; “Early one mornin’ the sun was shinin’ / I was lyin’ in bed” [“Tangled Up in Blue”]; and, most relevant here, “Mr. Tambourine Man.”

The singer in “Mr. Tambourine Man” has apparently been up all night, suggesting insomnia. [For the purposes of this argument, let’s continue to think of the singer as a woman.] She repeatedly declares “I’m not sleepy,” doubling down with “My weariness amazes me” and “the ancient empty street’s too dead for dreaming.” Methinks the lady doth protest too much. The song’s trippy mood is often attributed to drugs, but its hallucinatory quality might just as well describe drifting off to sleep. Instead of counting sheep, she follows a fantasy figure into dreamland. “I know that evening’s empire has returned into sand” reminds me of “Mr. Sandman, bring me a dream.” And his insistent request, “Hey! Mr. Tambourine Man, play a song for me,” is reminiscent of a child asking for one more story or lullaby before going to sleep.

Dylan and Jackson both recognize the strategic appeal of this liminal setting between waking reality and dreams. It allows the narrative and imagery to drift seamlessly into surrealism. It also keeps the characters and listeners/readers disoriented and off balance. Our hands can’t feel to grip, our toes too numb to step. Jackson’s protagonist persistently struggles to stay awake: “She opened the window and sat down next to it until she realized that she had been asleep and it was twenty minutes to one. Now, suddenly, she was frightened” (13). Think how often sleep factors into fairy tales as well: Sleeping Beauty, Snow White, Goldilocks, The Wizard of Oz, Alice in Wonderland, etc.

Jackson has a special gift for capturing the stifling gender expectations of her era. She doesn’t hit readers over the head with her critique of the patriarchy. Instead she shows the countless little ways in which her protagonist feels compelled to look, dress, behave, and conform to “the feminine mystique.” The main character in “The Daemon Lover” has thoroughly internalized this ideology. Even when she is entirely alone in her apartment, she constantly scolds herself for her inadequacies.

The overriding pressure governing her life is the coercion to marry a man. Jamie is her golden ticket to fulfill this primary duty of “true womanhood.” And she seems so close to winning the marriage lottery. She begins a letter announcing the good news to her sister: “‘Dearest Anne, by the time you get this I will be married. Doesn’t it sound funny? I can hardly believe it myself, but when I tell you how it happened, you’ll see it’s even stranger than that.’” (9).

Her age adds significantly to her anxiety. By the standards of the day, she is an “old maid” past her prime and confronting a lifetime of barren spinsterhood. Such notions may strike us as absurd, and Jackson is clearly critical of this sexist ideology. But her protagonist is fully indoctrinated: “she could not bear the thought of Jamie bringing to marriage anyone who looked haggard and lined. You’re thirty-four years old after all, she told herself cruelly in the bathroom mirror. Thirty, it said on the license” (12).

Eventually the protagonist gets tired of waiting for her demon lover and goes to search for him. She hurries around from person to person, looking for clues, trying to track Jamie down. It’s part archetypal quest, part nursery rhyme adventure (cf. Little Red Hen or Cock Robin), and part pathetic delusion. On one level, she knows she’s deceiving herself: Jamie has run away and will never marry her. But she has invested too much in this dream to just let it slip away, so she continues her mad pursuit of James Harris.

She becomes so frantic that she considers going to the police. Only then does the ridiculousness and utter unfairness of her situation start to sink in, prompting this revealing passage:

And then she thought, What a fool I’d look like. She had a quick picture of herself standing in a police station, saying, “Yes, we were going to be married today, but he didn’t come,” and the policemen, three or four of them standing around and listening, looking at her, at the print dress, at her too-bright make-up, smiling at one another. She couldn’t tell them any more than that, could not say, “Yes, it looks silly, doesn’t it, me all dressed up and trying to find the young man who promised to marry me, but what about all of it you don’t know? I have more than this, more than you can see: talent, perhaps, and humor of a sort, and I’m a lady and I have pride and affection and delicacy and a certain clear view of life that might make a man satisfied and productive and happy; there’s more than you think when you look at me.” (23, emphasis added)

Fourteen years before the publication of The Feminine Mystique, Jackson’s protagonist is essentially diagnosing “the problem that has no name” for mid-century American women and asking “Is this all?” It’s not just a problem plaguing suburban housewives who have seemingly achieved the dream, but also a congenital disease infecting women futilely groping toward that mirage.

Jackson’s “The Daemon Lover” is a story of dignity under assault. The nameless protagonist desperately pursues a man who obviously doesn’t want to wed her and who may not even exist. An author could portray such a character as hopelessly neurotic, but Jackson instead builds sympathy for the character as a byproduct of her society’s warped gender expectations. The nameless protagonist has been trained to believe that her total worth is determined by her ability to land a husband and raise a family.

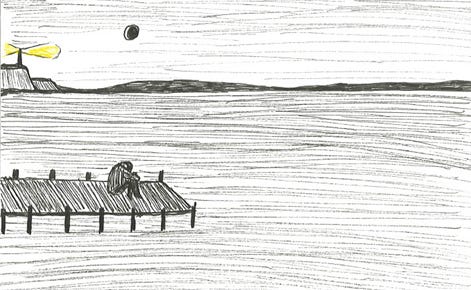

At the end of “The Daemon Lover,” the jilted fiancée finally thinks she has tracked Jamie down. She runs upstairs and finds two doors. The scene unfolds like an anxious nightmare fueled by fear, loneliness, and shame. “She knocked, and thought she heard voices inside, and she thought, suddenly, with terror, What shall I say if Jamie is there, if he comes to the door? The voices seemed suddenly still. She knocked again and there was silence, except for something that might have been laughter far away” (27). She is mortified, but she’s determined to see this thing through to the end. She tries the other door, but all she finds in an otherwise empty room is a scary rat, “its evil face alert, bright eyes watching her. She stumbled in her haste to be out with the door closed, and the skirt of the print dress caught and tore” (27).

The final paragraph closes the door on all the protagonist’s dreams of happiness. The demon lover remains conspicuously absent from Jackson’s “The Daemon Lover,” yet the woman’s ultimate damnation seems just as assured as it was in the old ballad:

She knew there was someone inside the other apartment, because she was sure she could hear low voices and sometimes laughter. She came back many times, every day for the first week. She came on her way to work, in the mornings; in the evenings, on her way to dinner alone, but no matter how often or how firmly she knocked, no one ever came to the door. (27-28)

She keeps coming back. How sad is that? One humiliation isn’t enough for her. She keeps returning for her daily dose. Life has nothing more to offer her than closed doors, dirty rats, public mockery, and private despair. Her ship hasn’t come in, and there’s no cause to believe it ever will.

Jackson’s adaptation of Child Ballad No. 243 offers a fascinating variation on the myth. Instead of a carpenter’s wife, what if James Harris targeted an unmarried childless contemporary woman instead? Rooted in the social mores of her time and place, Jackson’s answer is basically “damned if you do and damned if you don’t.” Resist the devil’s temptations and be doomed to a life of unfulfilled dreams, or chase after the devil . . . and meet the same damn fate. The protagonist of “The Daemon Lover” doesn’t follow James Harris to hell—she doesn’t have to. She already lives in her version of hell in mid-century America.

“The Daemon Lover” works as a counternarrative to the trope Jackson inherited. Rather than reinforcing the moral prohibitions of the patriarchy, Jackson warns of the destructive consequences that come from pursuing “the feminine mystique.” As Ruth Franklin observes, “The themes of Jackson’s work were so central to the preoccupations of American women during the postwar period that Plath biographer Linda Wagner-Martin called the 1950s ‘the decade of Jackson.’ Her body of work constitutes nothing less than the secret history of American women of her era” (5-6).

Works Cited

Child, Francis James. English and Scottish Popular Ballads. Houghton Mifflin, 1904.

Dylan, Bob. Official Lyrics. The Official Bob Dylan Website.

https://www.bobdylan.com/.

Franklin, Ruth. Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life. New York: W. W. Norton, 2016.

Friedan, Betty. The Feminine Mystique. Dell, 1963.

Friedman, Albert B., ed. The Viking Book of Folk Ballads of the English-Speaking World. Viking, 1956.

Heylin, Clinton. Dylan’s Daemon Lover: The Tangled Tale of a 450-Year Old Pop Ballad. Helter Skelter, 1999.

Jackson, Shirley. The Lottery and Other Stories. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1982.

Lomax, Alan. The Folk Songs of North America in the English Language. Doubleday, 1960.

Muir, Andrew. “Our wells are deep: Dylan, Shakespeare and Broadside Ballads.” More True Performing (11 March 2025),

.

Oates, Joyce Carol. “Joyce Carol Oates on Dylan’s ‘It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue.’ Wall Street Journal (19 May 2015), https://celestialtimepiece.com/2015/01/21/why-is-where-are-you-going-where-have-you-been-dedicated-to-bob-dylan/.

Scott, Sir Walter. Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border. 5th edition. A. Constable, 1812.

Shook, Coyote. “The Daemon Lover.” Sonora Review (11 February 2022), https://sonorareview.com/2022/02/11/the-daemon-lover-coyote-shook/.

Brilliant stuff, Graley and this took me completely by surprise: "Mr. Tambourine Man.” I’ve long been aware of the song’s allusions to the Pied Piper of Hamelin, but I’ve only recently tuned into its echoes of “House Carpenter.”"

I can safely say that I never would have had you not pointed them out here.

btw, I think I prefer the earlier version of "House Carpenter", but we are truly blessed to have either, far less both.

Brilliant as usual, Graley. And right on about the Another Self Portrait version. Something was definitely going on with him during that period. We should panel this out sometime.