Dylan + Art

Connections

One of art’s superpowers is its ability to forge connections. I’m thinking here primarily about connections between the artist and the audience by way of an artwork or performance. But I’m also talking about connections among audience members who bond over their shared passion for an artist and their sense of communal belonging with each other—looking at you, fellow Bobcats and Dylanologists.

Dylan provides lots of great examples of this phenomenon, but lately I’ve been noticing it all over the place, while going to the movies, visiting the art museum, listening to music, and reading books. When inspiration comes knocking, you answer the door. Think of this installment of “Dylan + Art” less as a scholarly essay and more as a meditation, one where form mirrors content: links in the chain of the art of connection.

Hamnet

After submitting final grades for the fall semester in mid-December, I treated myself to a matinee screening of Hamnet. I’ve taught Maggie O’Farrell’s tremendously moving novel a few times, so I had been eagerly awaiting director Chloé Zhao’s film adaptation.

The novel is spellbinding from start to finish, but O’Farrell’s conclusion is especially staggering. Shakespeare and his wife Agnes had three children: Susanna and the twins Hamnet and Judith. Their only son Hamnet died at the age of 11, presumably of the plague (at least that’s how O’Farrell depicts it). This sudden loss devastates the distraught parents, and their separate grief threatens to destroy the marriage. Back home in Stratford, Agnes is outraged when she learns that her husband has written a play called Hamlet, which she regards as blasphemy against the memory of their dead son with essentially the same name. Determined to confront him, she travels to London and attends the play’s premiere at the Globe Theatre.

At first, Agnes is infuriated by the spectacle. But as soon as the actor playing Hamlet walks on stage, she is thunderstruck. His speech, his carriage, his mannerisms, his wit—he is an avatar for her son had he lived. She recognizes Hamlet as her husband’s way of mourning Hamnet, fantasizing a scenario in which the father takes the son’s place and dies in his stead, imagining the boy reincarnated as a young man. The play utterly wins her over.

In the powerful conclusion of Zhao’s film—a scene that isn’t part of the book—Agnes reaches out from the pit for the hand of the actor playing Hamlet. Previously we have witnessed her special gift for looking into people’s souls and reading their destinies when she holds their hands. In this case, the actor serves as a bridge connecting her to her dead son, allowing her one final encounter as he crosses over into death. Here is how that moment of connection between mother and son is described by O’Farrell and Zhao in their co-written screenplay:

We suddenly find ourselves on the stage with Hamnet in the last moments before he died, as he wandered at the edge of this life towards the black gate that would lead him to the next. […] He is looking back at his mother. Her calling of him has kept him at the edge of the gate, waiting, waiting for his father to build this temple and for his mother to find him. Agnes feels her son’s gaze and looks up. There is her boy. He has been waiting for her. He has been waiting for her so she can let him go. Hamnet smiles at his mother, turns and walks into the void.

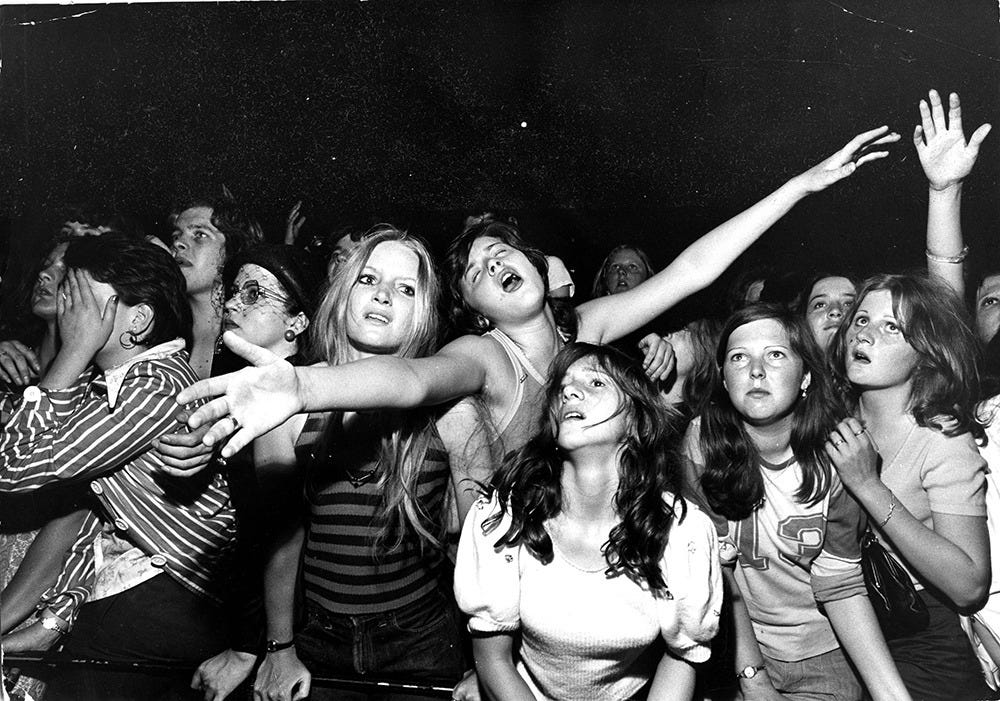

The most remarkable thing happens. When Agnes reaches out for the actor playing Hamlet, the rest of the audience moves in closer to the stage and does the same. They are moved so deeply by this play and this performer that they yearn to touch him, to make their emotional bond with him physical, tactile. What a beautiful gesture! It’s how all great art makes us feel: connected.

You know what it reminded me of? David Bowie. Awhile back I wrote a piece on Bowie, and when I saw the Globe audience reaching out toward Hamlet, irresistibly drawn toward this magnetic performer, it transported me back to Ziggy Stardust in concert.

“At the core of Bowie’s music,” observes Simon Critchley, “is a profound yearning for connection and, most of all, love” (171). This profound yearning worked both ways, shattering the fourth-wall of the stage and plugging Bowie into an electric circuit with his loving audience.

Critchley’s description of “a profound yearning for connection and, most of all, love” resonates perfectly with Zhao’s cinematic sensibilities. In a recent interview for the New York Times, David Marchese spoke with Zhao about their shared passion for the films of Terrence Malick. Marchese reflected, “There was a mysticism in The Thin Red Line, and a transcendental feeling about the natural world, that I hadn’t seen in a movie before and that I connected with so deeply.” There’s that word again: connection. “That’s really beautiful,” responded Zhao. “That is why we have art. It’s not trying to teach us something that we don’t know. It’s trying to help us remember who we are.” Describing the films that have meant the most to her, Zhao confided that they all “made me realize that this deeply uncomfortable tension I feel in my body, this yearning that sometimes feels like it’s going to consume me, this loneliness, on the other side of it is my yearning for connection and love.”

The Implorer

Still in the mood for treating myself, the next day I visited the Cincinnati Art Museum. Previous trips to this museum inspired earlier installments in the “Dylan + Art” series, beginning with a piece on Rodin. I had no idea that I was about to be floored by another bronze sculpture by Rodin’s former pupil and jilted lover, Camille Claudel.

I’m an art enthusiast, but I’m admittedly a total amateur with no expert training in the subject. I’m embarrassed to admit that I had never heard of Claudel before encountering her sculpture last month at the museum. I’ve done some homework since then. Claudel led a tragic life, and too often her personal woes have overshadowed her remarkable art. According to Emerson Bowyer and Anne-Lise Desmas,

Her passionate relationship with Auguste Rodin, mental decline, and internment in a psychiatric institution for the final thirty years of her life have provided rich fodder for a cottage industry in movies, plays, novels, musicals, and operatic scores. Despite the increased awareness of the artist that such endeavors have achieved, they have often spun sensationalist and melodramatic tales of doomed romance, victimhood, and madness. This biographical miasma has tended to obscure—or even excise—the sculptor’s art and agency. (1)

I knew none of this when I walked into the familiar gallery of European Modernists at CAM and encountered this unfamiliar statue for the first time.

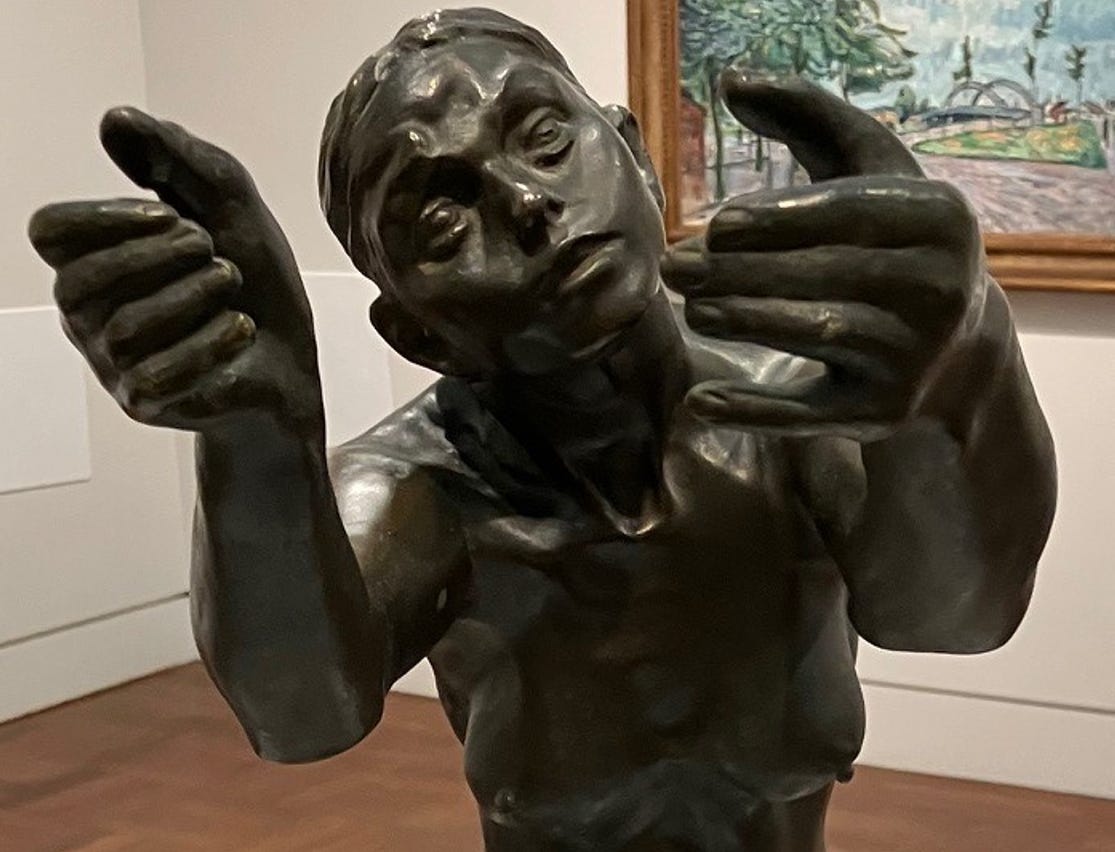

My angle of approach was a right-profile view. The first thing that struck me was a sense of suspended motion, like the figure was tumbling forward and lunging toward something just out of reach. “Never let me go!” the statue seems to implore, even as she is denied the object of her desire. There’s desire for you: the object is always out of reach.

My interest piqued, I glanced at the museum label to help get my bearings on what I was seeing. Camille Claudel, pupil of Rodin—of course! The last time sculptures had stopped me in my tracks like this, it had been Rodin’s Burghers of Calais. The placard also informed me that The Implorer was part of Age of Maturity on display at Musée d’Orsay in Paris: “In the three-figure group, an older woman leads a middle-aged man away from a kneeling young woman who reaches up to him—at once an allegory of aging and a meditation on loss following the rupture in the two artists’ relationship.”

After doing some research, I learned more about Claudel’s sources. The man is modeled after Rodin, the older woman is an unflattering depiction of his longtime companion Rose Beuret, and the younger woman is a self-portrait of Claudel. The sculptor’s brother, the poet Paul Claudel, immediately recognized the identity of The Implorer: “My sister! My sister Camille. Imploring, humiliated, kneeling, this superb woman, this proud woman, this is how she is represented. Imploring, humiliated, kneeling, and naked!” (qtd. Bowyer & Desmas 191).

But in the room at the time, I was just responding viscerally to what I saw. As I moved in closer and started circling around counter-clockwise, I got my first frontal view of the woman.

Mesmerizing! I’m still haunted by those yearning eyes and grasping hands.

As the lone spectator in the room that cold December morning, it felt like she was reaching for me, trying to make a connection with me. Of course, I’m aware of the rules against touching artworks in the museum, so I promise I kept my hands to myself, dear reader. But on an emotional level, she bridged the distance and made an instant, powerful connection.

As I continued circling, I began to register the play of light on bronze. I also noticed how the spotlight above cast a shadow of The Implorer on the floor below.

This was the point at which I pulled out my phone and took my first picture. Looking back at it now, I’m strangely moved by the way her shadow merges with my own on the floor. “Shadows are falling, and I’ve been here all day” (“Not Dark Yet”). Something feels subversive about this intermingling, as if our shadows had achieved the connection forbidden by the museum’s prohibitions. “Shadows grew closer as we touched on the floor” (“Caribbean Wind”).

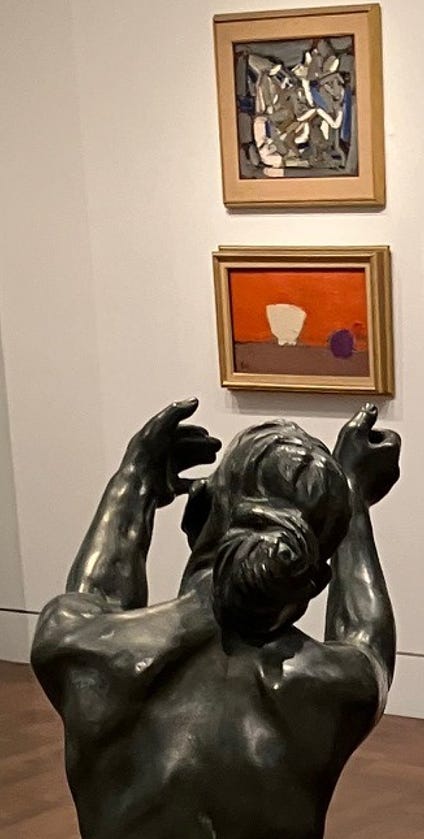

As I made my way to the back, I noticed the curvature of her spine, which reinforced my initial impression of movement, almost as if she were swaying to music.

I gradually became conscious of the figure’s placement within the gallery. The Implorer is powerful enough to hold a room, and indeed that was how Rodin’s Burghers of Calais had been displayed. They were set apart from the rest of the museum’s holdings, given pride of place in their own space, inviting exclusive contemplation. Not so with Claudel’s statue. She is placed in the midst of several European Modernist paintings.

On one hand, like the scene from Hamnet, The Implorer captures something essential about the art of connection. On the other hand, by situating the figure in a room full of paintings, the artwork occupies the position of a spectator—the same perspective as me, in this room for the umpteenth time, looking at those paintings on the walls.

Context matters. Individual responses are shaped by external forces and suggestive juxtapositions. For this specific display in this gallery, the sculpture reaches out toward the facing wall, grasping for Trapped Rocks (top) and White Bowl (bottom), both by Nicolas de Staël. And why not? She is a trapped rock, suspended in place indefinitely; she is an empty vessel, waiting to be filled with meaning by random passersby.

Speaking of random passersby, there’s no separating my personal response to The Implorer from the lingering effects of watching Hamnet the day before. The scene with Agnes and the audience reaching out toward Hamlet followed me like a shadow into the gallery and haunted my reaction. Surely one reason I was so struck by this statue was the uncanny sense of repetition. Here was another woman in another artwork poignantly embodying a profound yearning for connection and love.

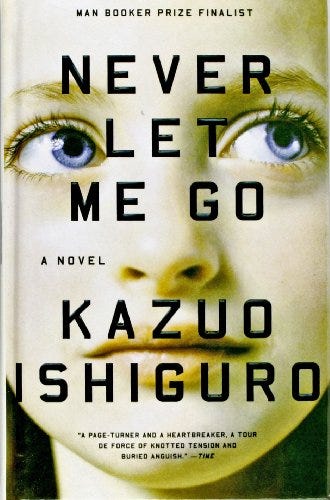

Never Let Me Go

After Christmas, it was time to start preparing for the new semester. I’m teaching a new course on “Literature of Captivity,” and I include some novels I haven’t taught in a while. I spent part of the winter break rereading these books. I was enchanted all over again by Kazuo Ishiguro’s melancholic Never Let Me Go (2005).

The book’s title requires a lot of unpacking. It refers to a fictional song on the fictional 1956 album Songs After Dark by the fictional singer Judy Bridgewater. A cassette tape of this album is the most prized possession of the narrator Kathy, a student at a mysterious school in rural England called Hailsham.

We eventually piece together that the students there are cloned human beings created for the purposes of mandatory organ donations once they mature into adults. As clones, they have no parents per se, and they are medically sterilized to prevent them from having children. These factors become significant for appreciating a pivotal scene in the novel.

Kathy’s favorite song from the tape is “Never Let Me Go.” She explains, “It’s slow and late night and American, and there’s a bit that keeps coming round when Judy sings: ‘Never let me go . . . Oh baby, baby . . . Never let me go . . .’ I was eleven then, and hadn’t listened to much music, but this one song, it really got to me” (70). Kathy creates an elaborate maternal fantasy around this song:

I didn’t used to listen properly to the words; I just waited for that bit that went: “Baby, baby, never let me go . . .” And what I’d imagine was a woman who’d been told she couldn’t have babies, who’d really, really wanted them all her life. Then there’s a sort of miracle and she has a baby, and she holds this baby very close to her and walks around singing: “Baby, never let me go . . .” partly because she’s so happy, but also because she’s so afraid something will happen, that the baby will get ill or be taken away from her. Even at the time, I realised this couldn’t be right, that this interpretation didn’t fit with the rest of the lyrics. But that wasn’t an issue with me. The song was about what I said, and I used to listen to it again and again, on my own, whenever I got the chance. (70)

One day Kathy is alone in her room, listening to “Never Let Me Go,” when she realizes that the school patron (known as Madame) is eavesdropping on her. She recalls,

What I was doing was swaying about slowly in time to the song, holding an imaginary baby to my breast. In fact, to make it all the more embarrassing, it was one of those times I’d grabbed a pillow to stand in for the baby, and I was doing this slow dance, my eyes closed, singing along softly each time those lines came around again: “Oh baby, baby, never let me go . . .” (71)

This scene upsets Madame so much that she rushes away sobbing. Years later, Kathy confronts Madame and asks her why she reacted that way. She explains,

“When I watched you dancing that day, I saw something else. I saw a new world coming rapidly. More scientific, efficient, yes. More cures for the old sicknesses. Very good. But a harsh, cruel world. And I saw a little girl, her eyes tightly closed, holding to her breast the old kind of world, one that she knew in her heart could not remain, and she was holding it and pleading, never to let her go. That is what I saw. It wasn’t really you, what you were doing, I know that. But I saw you and it broke my heart. And I’ve never forgotten.” (272)

There it is again: Never let me go! As in Hamnet and The Implorer, art expresses the profound yearning for connection and love, and art can also lament the abrupt severing of those bonds.

In the novel, the crucible for combining these desires and fears is “Never Let Me Go.” What is Ishiguro doing with this song? Quite a lot, it turns out. Although Judy Bridgewater and Songs After Dark are inventions, there are a couple of real songs called “Never Let Me Go” that probably served as models. One was written by lyricist Ray Evans and composer Jay Livingston for the film The Scarlet Hour (1956) and sung by Nat King Cole:

The other is a ballad written by Joe Scott in 1954 and sung by Johnny Ace:

Now it’s time to reveal another link in the chain: Kazuo Ishiguro is a big Bob Dylan fan! When he was awarded the 2017 Nobel Prize in Literature, the year after Dylan’s controversial selection, Ishiguro was quick to thank not only the Swedish Academy but also Bob Dylan. The day of the announcement, he told journalist Anita Singh that Dylan “was the single greatest hero for me when I was growing up. Without Dylan’s words and music, I probably wouldn’t have been a writer.”

Prior to receiving his medal, Ishiguro recorded an interview for the Nobel foundation in which he credited Dylan as his first artistic inspiration:

I never really had a big ambition to be a writer until I was almost in my mid-twenties. From the time I was around 15 years-old, my big ambition was to be a songwriter. I spent a lot of time writing songs in my bedroom with a guitar. I was very much inspired by the man who won the Nobel Prize in Literature last year in 2016, Bob Dylan. I remember buying an album of his when I was 13 years-old. I still remember the album, it was John Wesley Harding. I think that’s when I first became very excited about the idea that you could use words in a very mysterious way, and create entire worlds, just with a few words. Of course, the music and the singing and all these things are also very important to me—it’s that whole combination. But the excitement about words, and that you could use them in this way, that really happened to me when I listened to my very first Bob Dylan album when I was 13 years-old.

Ishiguro estimates that he wrote “over a hundred songs myself in my bedroom, and I played them with my friends,” before making his fateful transition toward writing fiction.

Knowing his debts and devotion to Dylan, we can now hear Ishiguro invoking a sublime duet by Dylan and Joan Baez in the title song of his novel. Between October and December 1975, the pair covered Johnny Ace’s “Never Let Me Go” 24 times in the Rolling Thunder Revue. In his tribute to Dylan and Baez’s many duets over the years, Ray Padgett writes,

This cover of an old Johnny Ace song, belted at top volume, is probably my favorite of the Rolling Thunder ’75 duets. Hell, it’s one of my favorite Rolling Thunder songs period. Joan doesn’t just mirror his lines; she weaves around his vocals, darting in and out, echoing or following at times. Her occasional “whoa-oh-oh-oh”s behind him make the song.

I share Ray’s lofty assessment, and you will too after watching this video of their final performance at New York’s Madison Square Garden on December 8, 1975:

Just let me love you tonight

Forget about tomorrow

My darling, won’t you hold me tight

And never let me go

Dry your eyes, no tears, no sorrow

Cling to me with all your might

And never let me go

A million times or more dear

We said we’d never part

But lately I find you’re a stranger in my heart

Give me the right in summer or in springtime

To tell the world that you are mine

And never let me go

Dylan and Baez must have selected the song, at least in part, for its commentary on their deep personal and artistic connection, and they radiate thermonuclear heat from the stage in this burning rendition. This is the kind of emotionally charged art that makes you want to reach out to these magical performers, just like those audiences trying to connect with Hamlet and Ziggy.

Ishiguro has continued to occasionally write songs, and he has a longstanding collaboration with the American jazz singer Stacey Kent.

In 2024, they put out an album and book called The Summer We Crossed Europe in the Rain. I’m particularly drawn to the title song. Listen to the chorus, substitute “Europe” for “America,” and it doubles as a description of Dylan and Baez’s reunion on the Rolling Thunder Revue:

Let’s be young again, if only for the weekend

Let’s be fools again, let’s fall in at the deep end

Let’s do once more

All those things we did before

The summer we crossed Europe in the rain

In the introduction to the published lyrics, Ishiguro reflects on what songs have taught him about writing fiction. One thing he learned was a certain haunting quality, quintessential to the best songs, which Ishiguro tries to emulate in fiction. His challenge as a writer is “how do you create a story that lingers in the mind for days, months, even years after a book is finished?”

Because of my background in song, the longevity of a story’s impact has always been of paramount importance to me. When I struggle to put a novel together, I’m often struggling to figure out not so much how to grip the reader (though that too), but how to say what I wish to say in a way that might haunt people for a long, long time. (x)

This haunting quality isn’t the exclusive domain of songs, but they seem better at achieving it than the other arts.

A song lives or dies by its ability to infiltrate the listener’s emotions and memory, and, like a parasite, take up long-term residence, ready to come to the fore in moments of joy, grief, exhilaration, heartbreak, whatever. No one aspires to write a song that catches the attention only while it’s being heard, then gets forgotten. That’s not how songs work. (x-xi)

Exactly right. Regardless of genre and irrespective of subject matter, the best songs all appeal directly to the listener and plead “Never let me go!”

The art of connection might initially hit us like a bolt from the blue, but the best examples, like the ones we’ve been considering here, continue to haunt us long after the first encounter. In his Nobel Lecture, Ishiguro says that building these lingering connections is his chief aim as a writer: “One person writing in a quiet room, trying to connect with another person, reading in another quiet—or maybe not so quiet—room.”

Ishiguro proves he is a worthy descendant of Dylan when he declares the primacy of feelings for his writing. That’s the litmus test for Dylan’s art of connection, and the same holds true for Ishiguro. He declares in his Nobel Lecture:

Stories can entertain, sometimes teach or argue a point. But for me the essential thing is that they communicate feelings. That they appeal to what we share as human beings across our borders and divides. […] Stories are about one person saying to another: This is the way it feels to me. Can you understand what I’m saying? Does it also feel this way to you?

How does it feel? It feels like you never want to let go.

Works Cited

Ace, Johnny. “Never Let Me Go.” Duke, 1954.

Bowyer, Emerson, and Anne-Lise Desmas, eds. Camille Claudel. Getty Publications, 2023.

Claudel, Camille. The Implorer (1898-99; cast in bronze c. 1905). Cincinnati Art Museum.

Critchley, Simon. On Bowie. Serpents Tail, 2016.

Hamnet. Directed by Chloé Zhao. Universal, 2025.

Ishiguro, Kazuo. “My Twentieth Century Evening—and Other Small Breakthroughs.” 2017 Nobel Prize for Literature Lecture. The Nobel Prize (7 December 2017), https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/literature/2017/ishiguro/lecture/.

---. Never Let Me Go. Vintage, 2005.

---. The Summer We Crossed Europe in the Rain: Lyrics for Stacey Kent. Knopf, 2024.

Kent, Stacey. “The Summer We Crossed Europe in the Rain.” The Changing Lights. Curtis Schwartz, 2013.

Marchese, David. “The Interview: Chloé Zhao Is Yearning to Know How to Love.” New York Times (24 January 2026), https://www.nytimes.com/2026/01/24/magazine/chloe-zhao-interview.html.

Nobel Prize. “Kazuo Ishiguro, Nobel Prize in Literature 2017: Official Interview.” YouTube (6 December 2017),

Padgett, Ray. “A Tribute to Bob Dylan and Joan Baez’s Duets.” Flagging Down the Double E’s (22 December 2024),

Singh, Anita. “Without Dylan, I would not be a writer: Nobel Prize winner Kazuo Ishiguro.” Sydney Morning Herald (6 October 2017), https://www.smh.com.au/entertainment/books/without-dylan-i-would-not-be-a-writer-nobel-prize-winner-kazuo-ishiguro-20171006-gyvjbl.html.

Terrific piece, as per usual! Were you aware that Chloe Zhao and Dylan are mutual admirers? She has spoken of her love of his music and even worn Dylan t-shirts in interviews. Dylan is a huge fan of her 2017 film THE RIDER (going so far as to tell the Broadway cast of Girl from the North Country that it was the only movie he liked).

I enjoyed this read very much. Looking forward for more!