BOWIE

Dylan's Shadows, Part 3

I hope you have enjoyed Part 1 and Part 2 of this series on Dylan’s shadows. As advertised, this final installment takes a different approach by putting Dylan’s work into conversation with another great shadow artist. I’ve kept him waiting in the wings long enough, so now it’s finally time to bring him out on stage. David Bowie!

I’m excited to offer this deep-dive into Bowie, an artist I’ve loved for decades but have never written about until now. This piece makes no attempt to cover the entirety of his remarkably eclectic and innovative career. Instead I’ll focus on the recurring pattern of shadows in select examples from his musical, visual, and performative art. Several categories we considered previously in Dylan—shadows rivals, shadow selves, shadow art, the shadow of death—prove just as integral to Bowie’s work.

From early on, Bowie identified a shadow relationship with Dylan, at once a big-brother mentorship and a doppelganger competition. For most of Bowie’s career, their relationship was distinctly one-sided: Bowie admiring and emulating Dylan; Dylan ignoring Bowie. However, Bowie produced some stunning work in the final years of his life, and I think Dylan took notice.

After years of chasing their own shadows, independently and on parallel tracks, their work begins to intersect in subtle but significant ways, specifically in Bowie’s Lazarus (2015) and Blackstar (2016) and Dylan’s Rough and Rowdy Ways (2020). Shadows provide a shared language for addressing likeminded concerns: coming to terms with internal conflicts, confronting ghosts of the past, reconnecting with one’s audience, preparing for death, and contemplating what will be left behind. In these various entanglements, for once it is Dylan who seems to be chasing Bowie’s shadow rather than the other way around.

By the way, this piece ended up running quite long, and I thought about breaking it down into two parts. But then I reconsidered and decided to just put it all out there. It’s already written, so why tease you along? Move at your own pace and cut it into bite-sized portions of your choice. Or treat it like a double-album. If you’re more interested in recent Bowie & Dylan, feel free to skip down and listen to the second disc first. Dealer’s choice. As always, I trust Shadow Chasing readers to take what you need and leave the rest.

Becoming Bowie

David Robert Jones fell to Earth (Brixton to be precise) on January 8, 1947. In one of those delicious synchronicities that the universe loves to serve up, Davy Jones shares the name Robert with Bobby Zimmerman, who also has a younger brother named David. Young Davy also felt a strong affinity for Elvis Presley, as they share the same January 8th birthday.

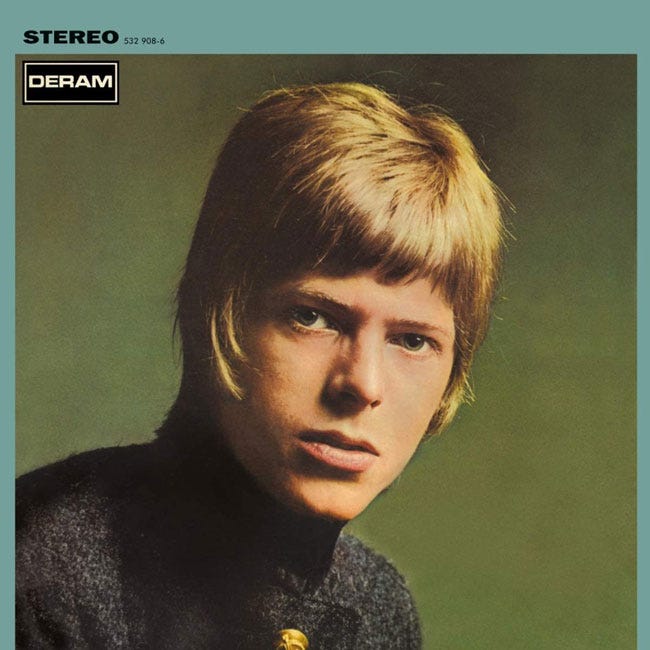

Bobby Zimmerman changed his name to Bob Dylan in the early sixties, his first of many acts of self-reinvention. Davy Jones followed suit in the mid-sixties by becoming David Bowie, though in his case the motive was more practical, as there was already a famous English rocker named Davy Jones in The Monkees. Bowie looked like a modish Monkee at first, but what he wanted to become was something closer to Dylan.

In a 2003 interview with Mikel Jollett, Bowie said that his first attraction to New York City and its arts scene came from The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan:

I’ve had a sentimental attachment to this city since I was, like, 17. It’s because around that time, I’d bought the second Bob Dylan album—the one where he’s walking down, I believe it’s Bleeker Street. And he’s got the girlfriend with him. And I thought, “This guy is so cool looking.” […] Then I played the album. I loved the music. And it was absolute dynamite. It was like this 60 year-old guy voice in this young kid. I thought, “This is the Beats. It’s everything that’s great about America in this one album.” (388)

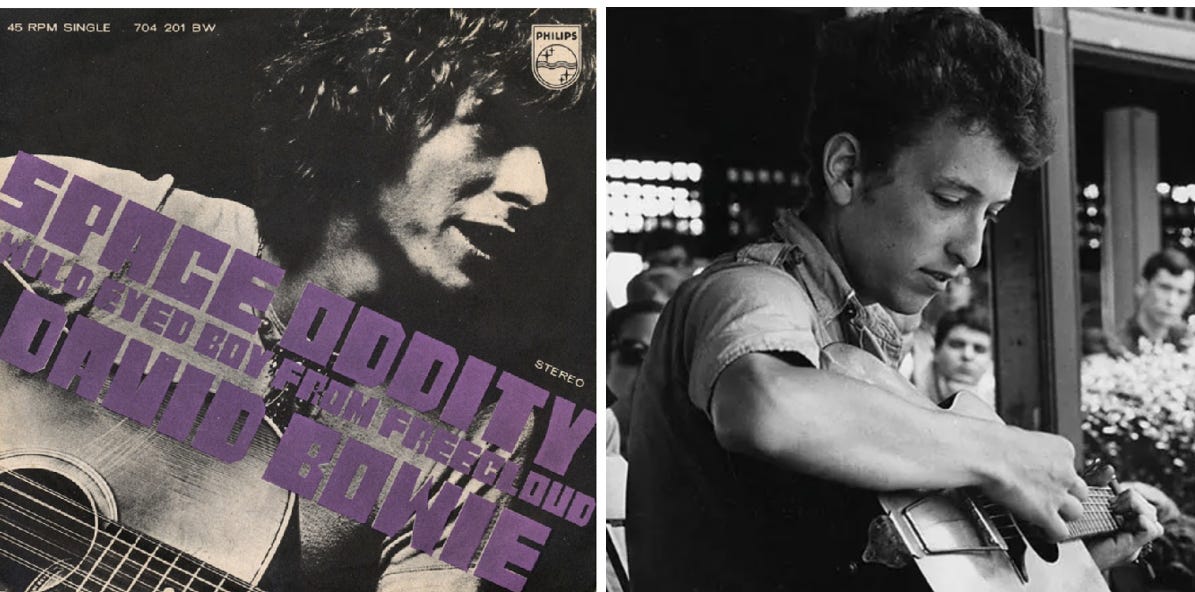

When he began to achieve widespread recognition in the late sixties, the music press branded him “the next Dylan.” Other artists chafed under this yoke, but Bowie seems to have welcomed it. Referring to the 1969 album David Bowie (aka Space Oddity), Nicholas Pegg observes, “But without doubt the overriding influence is Bob Dylan, echoes of whose early work ring throughout the album’s environment of acoustic guitars, harmonica solos and folksy protest lyrics” (276). Bowie himself claimed at the time that “‘he sings like Dylan would have done if he’d been born in England’” (qtd. Pegg 277).

The shadow of Dylan, and a host of other shadows, are displayed prominently on Bowie’s great early album Hunky Dory (1971). The opening track, “Changes,” establishes the theme of the shadow self:

So I turned myself to face me

But I’ve never caught a glimpse

Of how the others must see the faker

I’m much too fast to take that test

The test is presumably one of authenticity: Are you being real? Are you being your true self? The postmodern singer cannot begin to understand what that could even mean. He’s in a constant state of flux, transforming from one character into another, no sooner adopting one mask than he gets bored, discards it, and tries on a different identity.

As philosopher Simon Critchley puts it in On Bowie, “Art’s filthy lesson is inauthenticity all the way down, a series of repetitions and reenactments: fakes that strip away the illusion of reality in which we live and confront us with the reality of illusion” (24). Others may see this as being fake, but not Bowie. For him, change is the essence of life and of art: “Ch-ch-changes / Turn and face the strange.” Don’t deny it or run away from it. Confront and embrace the shadow.

My favorite song on Hunky Dory is “Life on Mars?” Like young Dylan, Bowie appealed directly to outsiders and outcasts. In this song, disaffected youth is represented by a girl whose parents constantly criticize what they can’t understand.

It’s a god-awful small affair

To the girl with the mousy hair

But her mummy is yelling “No!”

And her daddy has told her to go

But her friend is nowhere to be seen

Now she walks through her sunken dream

Rejected by her family and abandoned by her friends, she retreats into the alternate reality of movies: “And she’s hooked to the silver screen.” But even the cinema is losing its magic for her: “But the film is a saddening bore / For she’s lived it ten times or more.” Where can I find sanctuary? Where can I feel truly at home? Where do I belong? These are essentially the same questions that Dorothy asks in “Over the Rainbow”:

Somewhere over the rainbow

Skies are blue

And the dreams that you dare to dream

Really do come true

This is the fantasy that sends Dorothy from Kansas to Oz and back again.

Somewhere over the rainbow

Bluebirds fly

Birds fly over the rainbow

Why, oh why can’t I?

This is the same plea for love and acceptance that leads the girl with the mousy hair to look up and ask, “Is there life on Mars?” Because there sure as hell isn’t life for her down on Earth.

In Part 1 of my series on Dylan’s shadows, I considered his use of movies in “New Danville Girl” to draw attention to the shadow play of failed relationships. A couple goes through the motions of love like actors playing a scene: “we’re busy talking back and forth to our shadows.” The artifice projected on screen mirrors the artifice enacted off screen and vice versa. Bowie adds a similar level of meta-commentary to “Life on Mars?” After depicting the lonely girl trying and failing to make a connection with the figures on the big screen, the singer pans out and bares the device, like pulling the curtain to expose the Wizard of Oz. It turns out that the girl in the mousy hair is also a character performing a scene. The singer reveals:

But the film is a saddening bore

Because I wrote it ten times or more

It’s about to be writ again

As I ask you to focus on…

The girl watches the movie, the singer watches the girl, and the listener watches them both: frames within frames, mirrors reflecting mirrors—Bowie’s shadow kingdom.

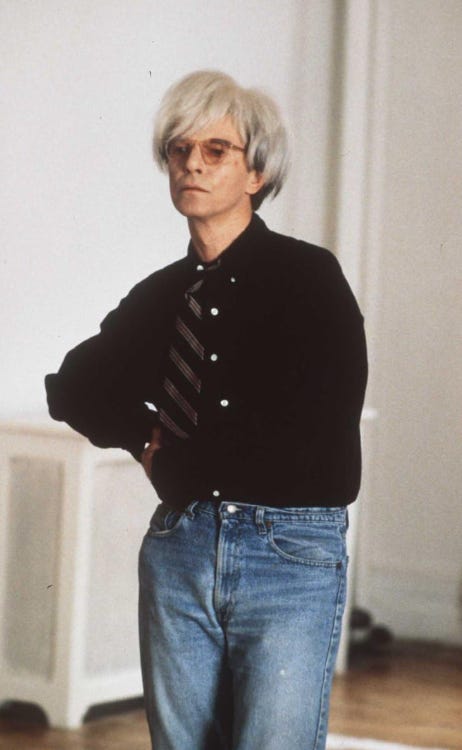

He extends this approach on the second side of Hunky Dory in “Andy Warhol.” Warhol’s films were notoriously transgressive, built upon improvisation and baring the device of traditional cinematic conventions. Bowie gives “Andy Warhol” the Warholian treatment, beginning with ad lib chatter and concluding with audience applause. In the chorus, the singer dissolves the barrier separating reality on and off screen: “Andy Warhol, silver screen / Can’t tell them apart at all.”

Bowie then gives Dylan the Dylanesque treatment in “Song for Bob Dylan.” He steals a page from “Song to Woody,” Dylan’s direct address to his mentor Woody Guthrie, penned to the tune of Guthrie’s own “1913 Massacre”:

Hey, hey, Woody Guthrie, I wrote you a song

’Bout a funny ol’ world that’s a-comin’ along

Seems sick an’ it’s hungry, it’s tired an’ it’s torn

It looks like it’s a-dyin’ an’ it’s hardly been born

Bowie also looks out upon a world gone wrong and he credits young Dylan with diagnosing its ills better than anyone. Tellingly, David Robert Jones addresses the song not to Dylan but to his inventor:

Ah, hear this, Robert Zimmerman

I wrote a song for you

About a strange young man called Dylan

With a voice like sand and glue

It takes a shadow to know a shadow. Bowie sets up a binary opposition between Zimmerman/Dylan, but he also implies some sort of pairing between Warhol/Dylan. It’s not just that the two songs appear back-to-back on the album. Bowie also invites comparison through similar vocabulary. The “sand and glue” description of Dylan’s voice echoes “Andy Warhol”: “He’ll think about paint and he’ll think about glue / What a jolly boring thing to do.” Later in “Song for Bob Dylan,” he refers to Dylan’s thoughts as paintings: “Then we lost your train of thought / The paintings are all your own.” In both songs, the paintings of Warhol and Dylan are destined to hang on the wall. In the former he sings, “Andy Warhol looks a scream / Hang him on my wall”; and in the latter he sings, “You gave your heart to every bedsit room / At least a picture on the wall.”

It may have appeared at first that Bowie was honoring his elders by writing these tribute songs. In retrospect, however, his agenda seems less magnanimous and more mercenary. By depicting both Warhol and Dylan as held together by glue and pinned to the wall, Bowie implies that they are museum pieces, interesting relics from the sixties who no longer possess their original vitality and relevance for the seventies.

In his 1976 interview with Robert Hilburn for Melody Maker, Bowie spoke about his ambitions at the time of Hunky Dory:

There was a feeling of optimism and enthusiasm in the album that reflected my thinking at the time. There’s even a song—”Song for Bob Dylan”—that laid out what I wanted to do in rock. It was at that period that I said, “okay [Dylan] if you don’t want to do it, I will.” I saw that leadership void. Even though the song isn’t one of the most important on the album, it represented for me what the album was all about. If there wasn’t someone who was going to use rock ’n’ roll, then I’d do it.

Bowie comes to bury Dylan, not to praise him. This knowledge helps us unpack the enigmatic chorus of “Song for Bob Dylan”:

Ah, here she comes, here she comes, here she comes again

The same old painted lady from the brow of the superbrain

She’ll scratch this world to pieces as she comes on like a friend

But a couple of songs from your old scrapbook could send her home again

Bowie sets up another opposition: Dylan vs. the Painted Lady. At first blush, the song seems to recruit Dylan as returning hero, begging him to reclaim his fallen mantle. Joan Baez would make a similar plea the following year in her song “To Bobby,” released on the appropriately titled album Come from the Shadows.

The idea is that Dylan needs to come out of retirement so he can lead his followers out of these dark times and back toward the light. Bowie represents the forces of rising darkness with the Painted Lady, a mongrel combination of the Whore of Babylon and the Queen Bitch of the album’s next song (where Bowie does his best Velvet Underground impression). Rather than depicting the Painted Lady as some squalid femme fatale, however, I think she represents the Jungian anima, an embodiment of dark but irrepressible energies gaining force in the counterculture. I would go further to suggest that Bowie sees himself as the Painted Lady, a gender-bending ch-ch-changeling who embodies the Zeitgeist of 1971 better than Dylan.

When Bowie sings “Oh, God, I could do better than that” in “Queen Bitch,” he is bragging that he could play a drag queen better than the cruisers he sees down on the street. He makes a similar wager with higher stakes in “Song for Bob Dylan,” auditioning for the vacated position of “voice of his generation”: “I could do better than [Dylan].” The shadow rivalry is on!

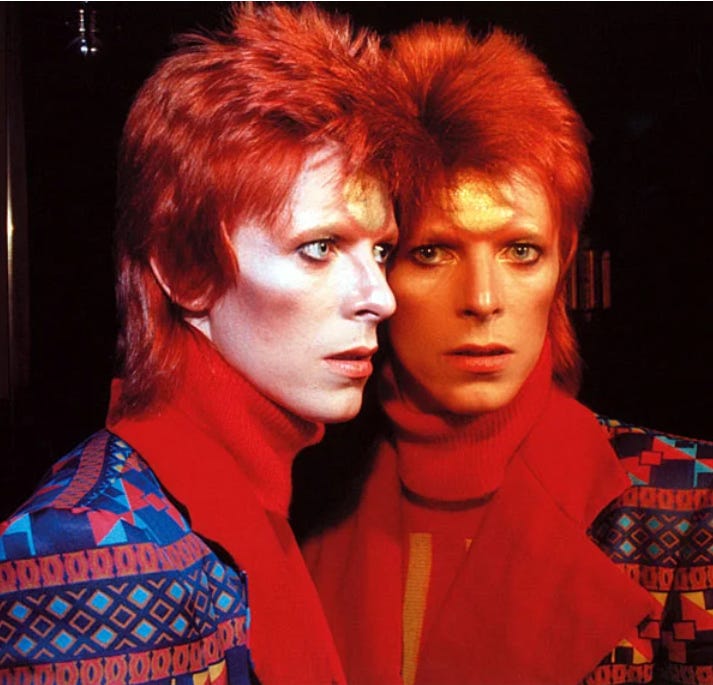

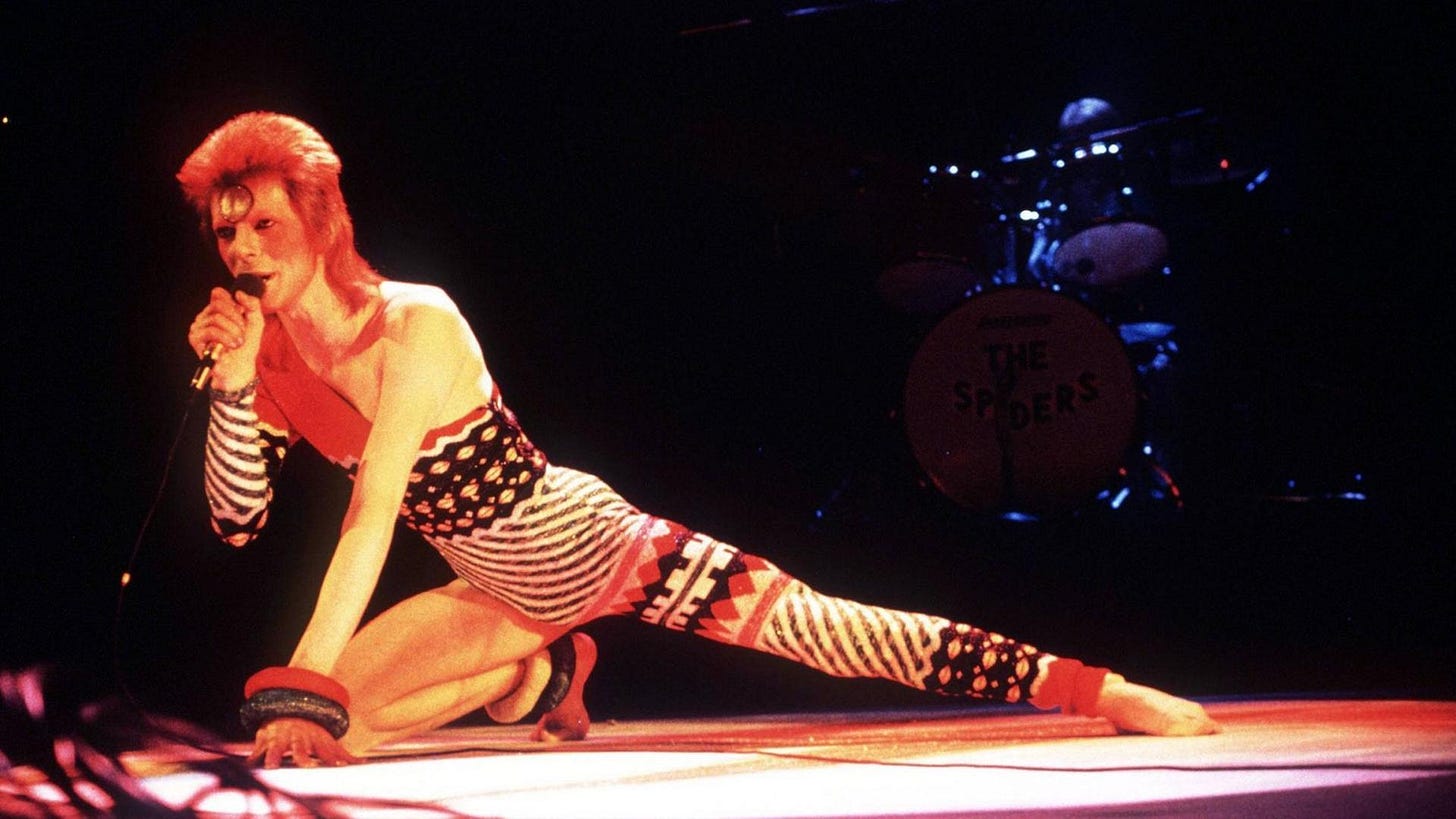

Bowie got his wish. On the combined strength of Hunky Dory and his phenomenal follow-up The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars, Bowie positioned himself at the cutting-edge of 1970s music. Dylan was never comfortable with the position of “voice of his generation,” but Bowie demanded it, wrapping it like feather boa around his neck and flaunting it on stage. As the title song proclaims, Ziggy Stardust was part Judeo-Christian savior and part Jungian archetypal shadow: “Making love to his ego / Ziggy sucked up into his mind / Like a leper messiah.”

Ziggy whipped his disciples into a frenzy, reaching across the footlights and speaking their pain, their hope, their desire for understanding and connection. He calls out to them in “Rock ‘’n’ Roll Suicide”:

Oh no, love, you’re not alone!

No matter what or who you’ve been

No matter when or where you’ve seen

All the knives seem to lacerate your brain

I’ve had my share, I’ll help you with the pain

You’re not alone!

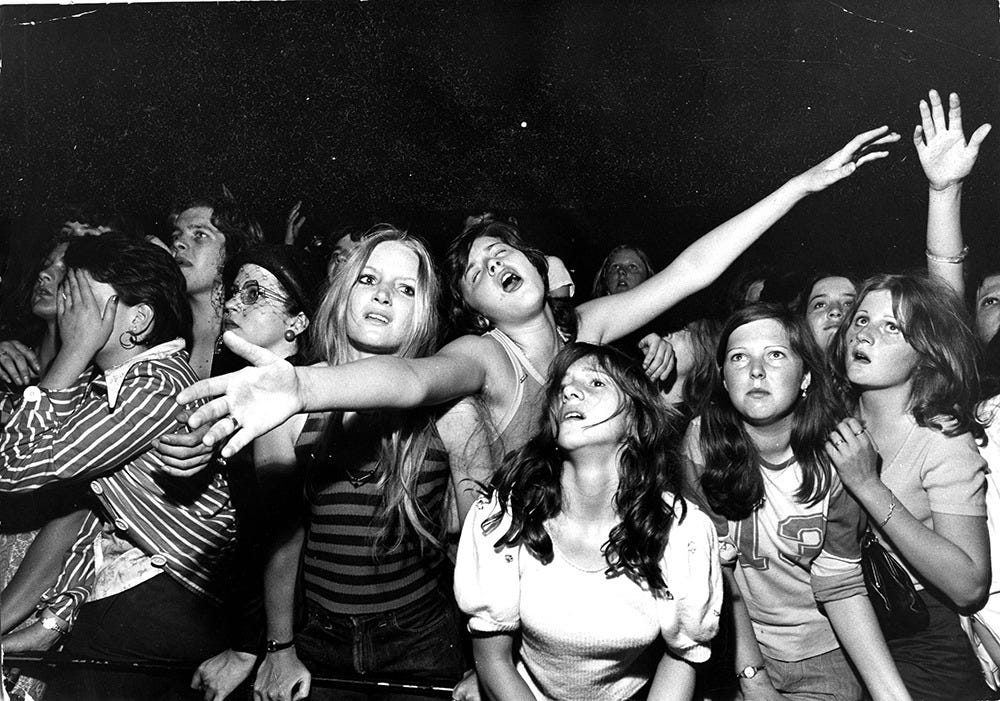

Simon Critchley vividly captures Bowie’s exalted role for his fans in the seventies:

Bowie incarnated a world of unknown pleasures and sparkling intelligence. He offered an escape route from the suburban hellholes that we inhabited. Bowie spoke most eloquently to the disaffected, to those who didn’t feel right in their skin, the socially awkward, the alienated. He spoke to the weirdos, the freaks, the outsiders and drew us in to an extraordinary intimacy, reaching each of us individually, although we knew this was total fantasy. But make no mistake, this was a love story. (168)

Ziggy was a funhouse mirror reflecting his audience’s image back at them, magnified and distorted. He was their Shadow Man.

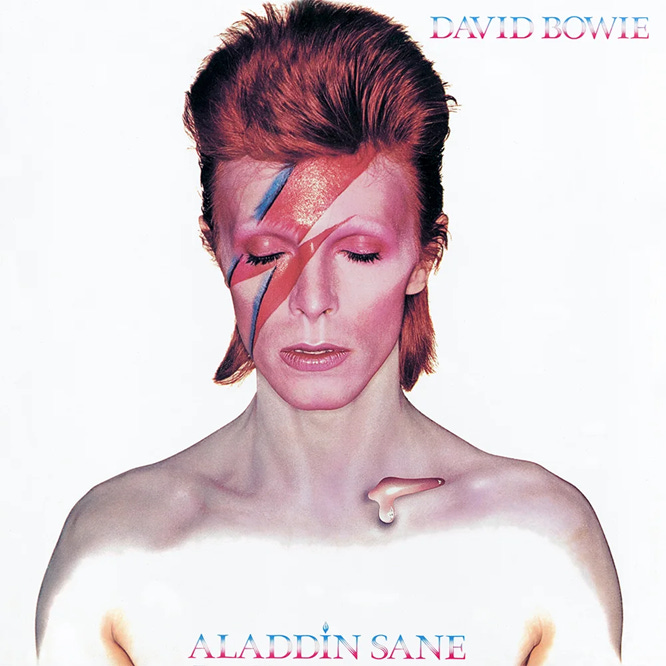

Never content to remain in one place or inhabit one identity for long, the Shadow Man kept reinventing himself throughout the decade. He killed off Ziggy and replaced him with Aladdin Sane (i.e., a lad insane), only to discard him in favor of the Thin White Duke. He relocated to Berlin with producer Brian Eno, where the pair reached their artistic zenith with a sonically adventurous trilogy of albums: Low (1977), “Heroes” (1977), and Lodger (1979). Bowie also memorably played the stranded space alien Thomas Jerome Newton in Nicolas Roeg’s film The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976).

It’s important to recognize that Bowie didn’t merely bewitch and bewilder his fans—he inspired them. In addition to offering empathy, he also modeled a way to survive through personal transformation. Critchley explains Bowie’s shape-changing appeal in terms that will resonate strongly with Dylan fans:

Just as Bowie seemingly reinvented himself without limits, he allowed us to believe that our own capacity for changes was limitless. Of course, there are limits—profound limits, mortal limits—in reshaping who we are. But somehow, in listening to his songs—even now—one hears an extraordinary hope that we are not alone and this place can be escaped, just for one day. (48-49)

Bowie vs. Bowie

By the beginning of the eighties, Bowie found himself in a similar conundrum as Dylan at the beginning of the seventies. Now what? Hunky Dory features Bowie shadow boxing with his rivals—Warhol, Dylan, Lou Reed—but his work from the eighties onward is increasingly animated by battles with his own shadow selves: Bowie vs. Bowie.

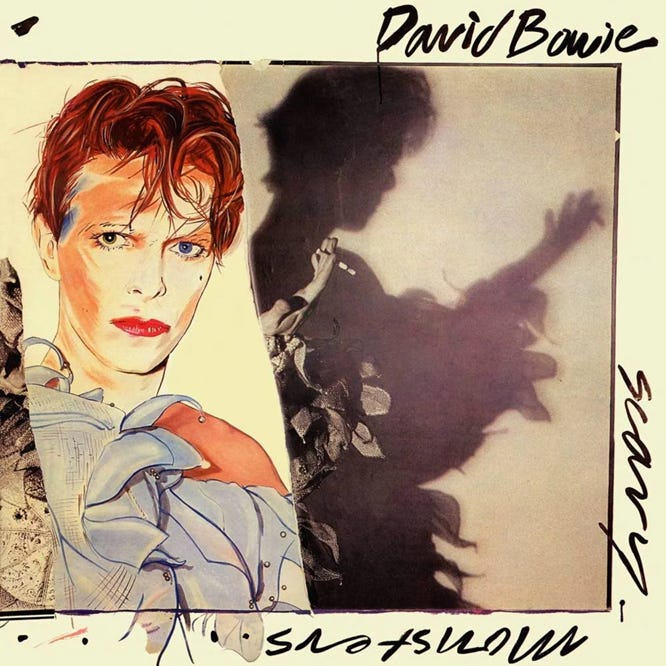

Take for instance Bowie’s first album of the decade, Scary Monsters (And Super Creeps) (1980). The big hit was “Ashes to Ashes,” where he resurrected the character that first won him fame, Major Tom from “Space Oddity”:

Do you remember a guy that’s been

In such an early song?

I’ve heard a rumour from Ground Control

Oh, no, don’t say it’s true

Alas, it is true, and the old boy isn’t faring well:

Ashes to ashes, funk to funky

We know Major Tom’s a junkie

Strung out in heaven’s high

Hitting an all-time low

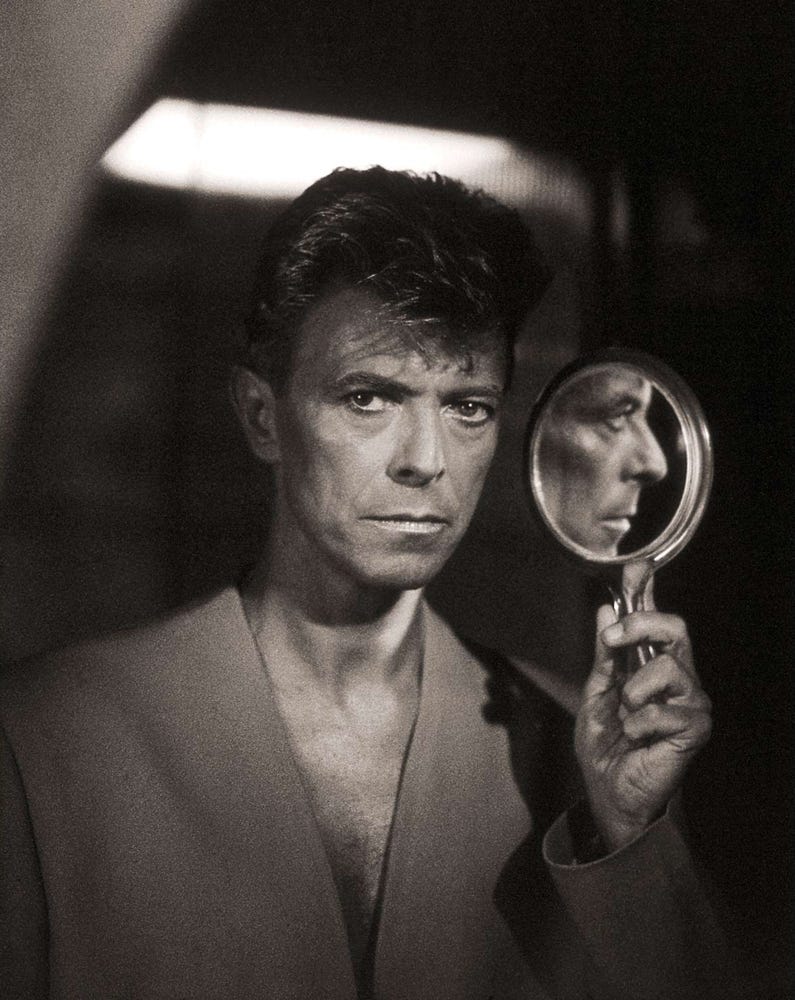

In his book-length study of the album, Silhouettes and Shadows: The Secret History of David Bowie’s Scary Monsters (And Super Creeps), Adam Steiner argues, “Through his music, Bowie tried to reassert an inner identity, the man behind the music, sick with his own shadow, haunted by characters he had created that threatened to overpower him” (25). In his book Future Nostalgia: Performing David Bowie, Shelton Waldrep amplifies this interpretation, viewing Major Tom as a double for Bowie on multiple levels:

At one level the song’s lyrics are about his character, at another drug addiction, at still another a new character, a sci-fi Pierrot, who is lost in an inner if not an outer space. The multiple voices are echoed in the choric aspects of the song and in Bowie’s schizophrenic doubling of his own voice—he sings the lyrics and then repeats them, one step behind, in a resigned spoken voice as though he is a shadow of his own self. (91)

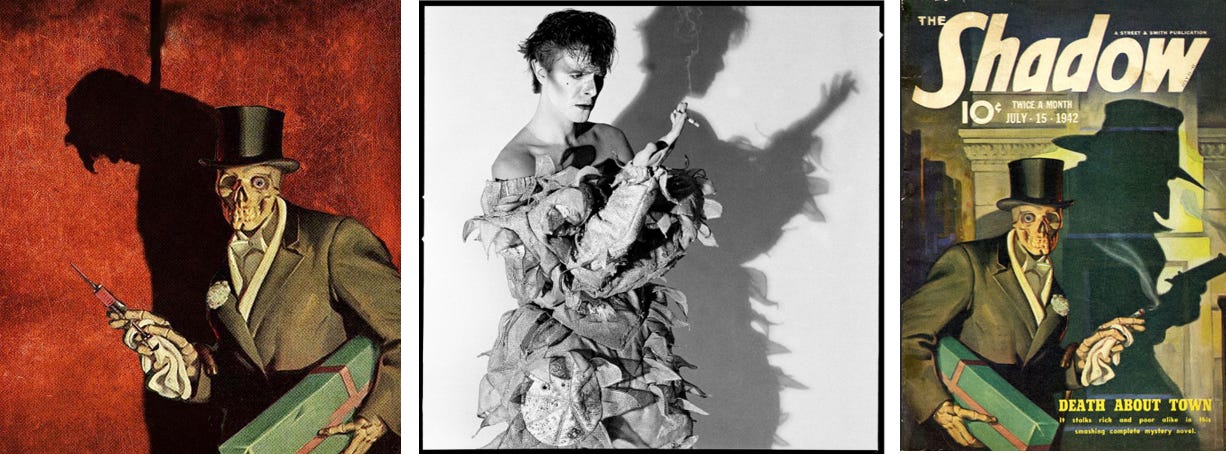

The shadow theme is prominently established on the cover of the album.

According to Matthew Lindsay, “the decadent glamour of [artistic designer Edward] Bell’s portrait was darkened by a shadow Bowie, cigarette in hand, from the [photographer Brian] Duffy photograph, occupying half the cover’s space.” Lindsay adds, “It was like a looming image from the German Expressionist movies Bowie loved, peopled with doppelgangers and fractured personalities . . . perfect for an album whose first English line was ‘silhouettes and shadows,’ striking a stylish pose while being full of decay.”

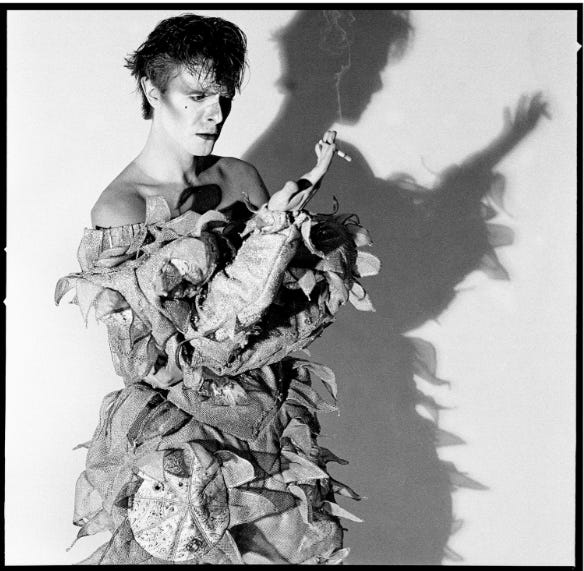

On the cover of Scary Monsters, as well as in the video for “Ashes to Ashes,” Bowie dresses as Pierrot, a figure he long identified with. As he told Jean Rook of the Daily Express in 1976, “I’m Pierrot. I’m Everyman. What I’m doing is theatre, and only theatre. […] What you see on stage isn’t sinister. It’s pure clown. I’m using myself as a canvas and trying to paint the truth of our time on it.” Pierrot has a long history within commedia dell’arte, but he has specific associations for Bowie. In 1967, Bowie played the narrator Cloud in a production of Pierrot in Turquoise, or The Looking Glass Murders, starring the mime artist Lindsay Kemp.

Brian Duffy photographed Bowie in a state of half-dress, taking off the costume, transitioning between character and actor, Pierrot and Bowie. The subject’s silhouette is projected against the wall, accentuating the doubleness of the gesture. As Adam Steiner colorfully describes it, “The shadow has broken from the past of his body, standing at an in-between space, sucking life from the pale light of his body, already grown stiff in legend” (192).

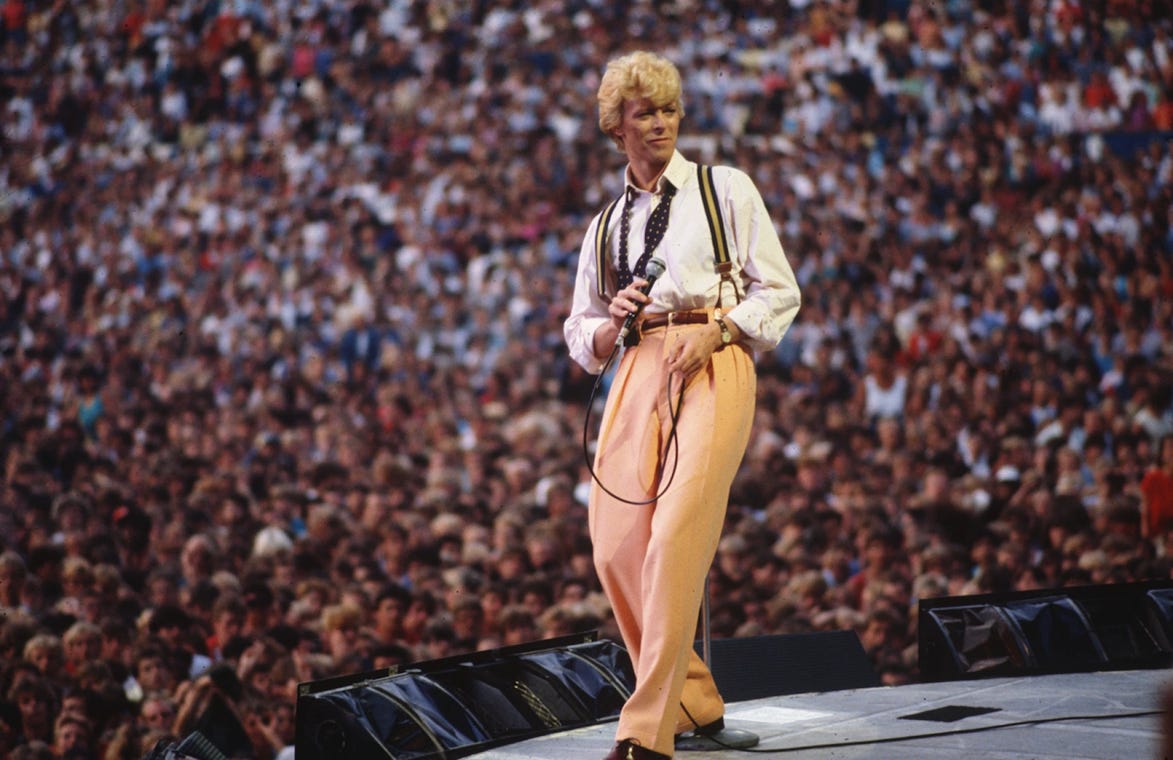

“Strung out in heaven’s high / Hitting an all-time low.” Strung out, okay. But was Bowie at an all-time low in the eighties? As with Dylan in the eighties, the answer depends very much upon what measuring stick one uses. With his next album Let’s Dance (1983) and the “Serious Moonlight” worldwide tour, Bowie was hitting all-time highs in album and ticket sales. As a teenager in the 1980s, this was my entry-point into Bowie, and I must say that I still love jamming to “Let’s Dance” and “Modern Love.”

However, dedicated Bowie fans generally regard Let’s Dance in much the same way that folk purists viewed Dylan going electric at Newport ’65: as a blatant sell-out, abandoning his artistic integrity in exchange for commercial success and celebrity status. Eighties Bowie was more popular than ever, but just going through the motions artistically—a shadow of his former self.

In hindsight, Bowie himself has come to judge this period rather harshly, as a lapse in his commitment to the duties of true art. Bowie was one of the featured artists in Michael Apted’s film Inspirations, a documentary including interviews with artists in various disciplines, as well as footage of them at work. In a telling excerpt, Bowie shares sage wisdom about maintaining artistic integrity, implicitly contrasting this advice with his work in the eighties.

I think it’s terribly dangerous for an artist to fulfill other people’s expectations. I think they generally produce their worst work when they do that. And the other thing I would say is that if you feel safe in the area that you’re working in, you’re not working in the right area. Always go a little further into the water than you feel you’re capable of being in. Go a little bit out of your depth. And when you don’t feel that your feet are quite touching the bottom, you’re just about in the right place to do something exciting.

Bowie vs. Dylan

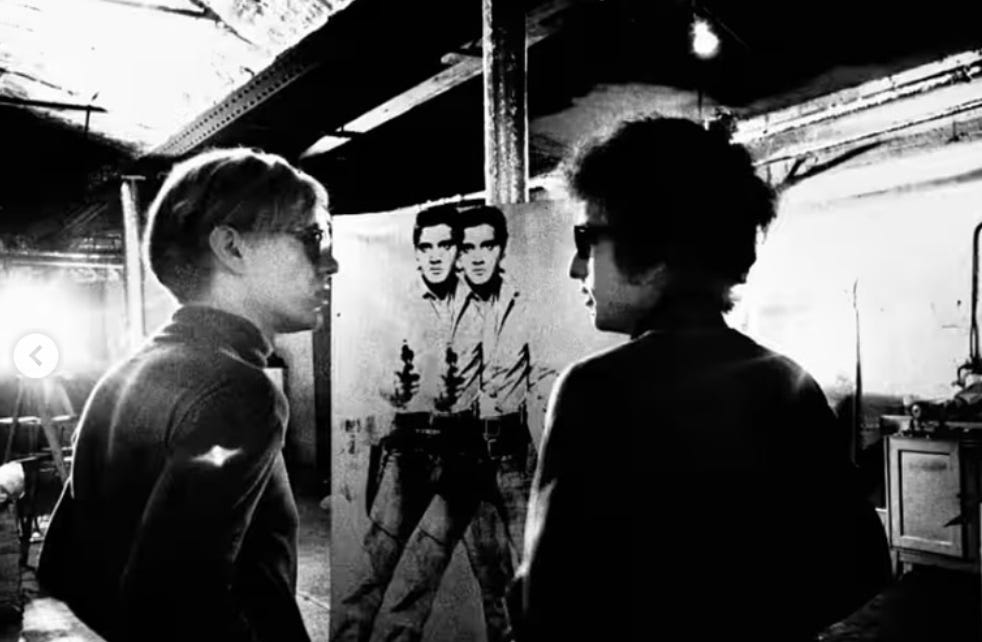

Now for some kiss & tell gossip—or diss & tell. According to Bowie, he first met Dylan in New York in 1975. In his Playboy interview the following year, he told Cameron Crowe: “We don’t have a lot to talk about. We’re not great friends. Actually, I think he hates me.”

After a gig they both attended, Bowie spoke with (or at) Dylan: “I was in a very, sort of . . . verbose frame of mind. And I just talked at him for hours and hours and hours, and whether I amused him or scared him or repulsed him, I really don’t know. I didn’t wait for any answers. I just went on and on about everything. And then I said good night. He never phoned me.” This must be the same encounter where Dylan allegedly told Bowie that he didn’t like “Young Americans,” though I’d prefer to think Dylan had better manners and better taste than that.

Each time Bowie recounted this story, it got worse. The subject came up again in his 1978 interview with Melody Maker, where he told Michael Watts:

I had a dreadful time with Bob Dylan. Absolutely ghastly. I talked at him for hours. I was fairly flipped out of my head, if I remember, and I just talked and talked. The funniest part about it was that I’d been talking about his music and what he should do and what he shouldn’t and what his music did and what it didn’t, and at the end of the conversation he turned to me and—I hope it was in jest, but I have a feeling it wasn’t—he said (falling into a banal American accent), “You wait till you hear my next album.” I thought, “Oh no, not from you, please! Not that, anything but that!” I don’t know whether I was in the correct state to appreciate him, but it was the first and last time I ever met him. (90)

Don’t meet your heroes. Or your shadows.

Ava Cherry confirms that Bowie received a chilly reception from other members of rock royalty. Biographer Dylan Jones includes this anecdote from Cherry:

I remember another time we were at this party with Bob Dylan, Ronnie, Wood, all these stars, and they were all being a bit frosty to David. We walked in and there was a very chilly atmosphere, like: Who is this glam-rock guy Bob Dylan said, “Who does this guy think he is?” And David said to me, “Who do I think I am?” They tried to make fun of him, and seemed like they were jealous of him. There were lots of people like that. (Jones 212)

Judging by the look of things, the rivals got along better when they met at The Whitney in 1985 for the release of Dylan’s Biograph box set.

Is Dylan asking Bowie to produce Knocked Out Loaded? Kidding. But you’ve probably heard the rumor that Dylan solicited Bowie to produce his 1983 album Infidels before eventually handing the reins over to Mark Knopfler. Maybe Dylan trusted Bowie’s musical instincts in the eighties better than his own. As further proof that Dylan dug Bowie’s sound more than he let on, consider all the musicians Dylan has poached for his band who previously played with Bowie, such as Mick Ronson, G. E. Smith, Charlie Sexton, and Matt Chamberlain.

As far as I know, Dylan has never covered a Bowie song in concert or on record. However, Bowie has remained remarkably loyal to Dylan’s songs. In The Complete Bowie, Nicholas Pegg tracks down seven covers over the years: “Blowin’ in the Wind,” “Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right,” “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall,” “Like a Rolling Stone,” “Maggie’s Farm,” “She Belongs to Me,” and “Tryin’ to Get to Heaven.” The latter song accrued an extra layer of poignancy when it was released posthumously on January 8, 2021, on what would have been Bowie’s 74th birthday.

For his part, Bowie seems to have accepted his love for Dylan’s songs without having to win the love of Dylan the man. By the nineties and into the 21st century, he ceased viewing Dylan as competition. He addressed the issue in a 1990 interview for the Dutch program Countdown. The interviewer asked if Bowie felt he had competitors in the music business. “I feel that, frankly, over the last twenty years or so, I’m pretty much my own man.” He drew an analogy with Dylan: “I suppose it’s pretty cheeky to put myself in the same light, but if I look at Bob Dylan, he doesn’t have competition: he’s just Bob Dylan. Whether you like him or don’t like him, whether he does good stuff or bad stuff, he’s still Bob Dylan. And you don’t compare him to anyone. It’s not a competition.”

Bowie claimed the same privileged status: “I think I probably am in the same kind of position. I’m David Bowie. I’m either good, I’m a pile of shit. Or you know, I’m accessible, I’m not accessible. I’m obscure, very commercial. I change all the time, but I’m still me. No [laughs]. My answer is no. I don’t feel I’m in a competition.” Let’s follow Bowie’s example by moving past rivalry and toward affinity in the late shadow art of Dylan and Bowie.

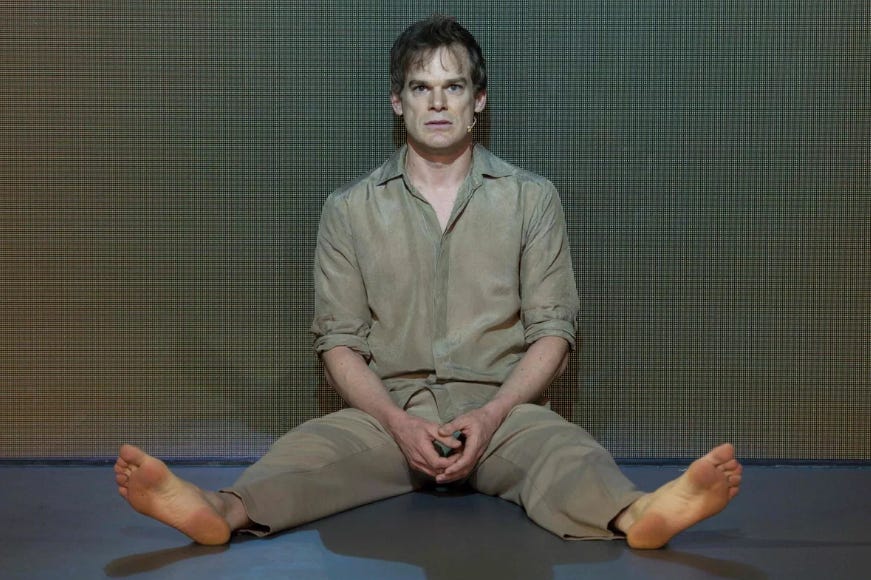

Lazarus: The Hero’s Journey

Great minds think alike. Bowie approached the Irish playwright Enda Walsh to write the book for a play built around his songs. The work that emerged was called Lazarus, and it premiered in Dylan and Bowie’s adopted city of New York in December 2015. Meanwhile, Dylan’s representatives contacted the Irish playwright Conor McPherson and proposed that he write a play inspired by Dylan’s songs. The result was Girl from the North Country, which premiered in Bowie’s hometown of London in July 2017. I have written elsewhere about Girl from the North Country, so I’ll focus here on Lazarus.

In his preface to the published script, Enda Walsh recalled his first meeting with Bowie, who arrived with a four-page treatment:

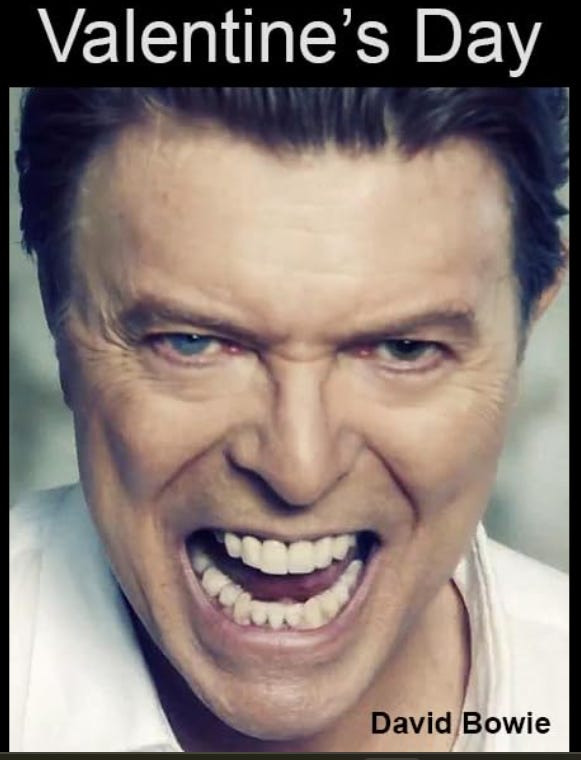

David had written three new characters around Thomas Newton (the stranded alien, seemingly immortal and definitely stuck). There was a Girl who may or may not be real; a “mass murderer” called Valentine; and a character of a woman who thought she might be Emma Lazarus (the American poet whose poem “The New Colossus” is engraved on the base of the Statue of Liberty)—a woman in this case who would help and fall in love with this most travelled of immigrants: Thomas Newton. (viii)

The killer Valentine is a character taken from Bowie’s sinister song “Valentine’s Day” on The Next Day (2013). The allusion to Emma Lazarus is surprising. When Bowie died of cancer less than a month after the musical’s premiere, everyone assumed that Lazarus referred to the man Jesus raised from the dead. That interpretation is legitimate, but true to form, Bowie embedded multiple identities within Lazarus. Who would have suspected Emma Lazarus as a source?

The main focus is on Thomas Newton, picking up the story where The Man Who Fell to Earth left off. If it has been a while since you saw the film, Girl gives us a concise distillation:

You were sent here from another planet and you never got back home to your family. You got real rich—started a bunch of companies. You tried to leave once before and these people did experiments on you and they hurt you really bad—turned you crazy—and you wouldn’t prove what you were to them—and they stopped you leaving. And you were in love with this woman called Mary-Lou. But she left years ago—and you’re still stuck here drinking gin and not being able to die or leave. That’s why your head’s sick. You’re heartbroken over all that stuff. (18)

In both the film and the musical, Newton is a stranded exile, numbing himself with gin and television, longing to return home.

Television offers one kind of alternate reality, but an even more important shadow kingdom in Lazarus takes the form of dreams. “I suspect that dreams are an integral part of existence, with far more use for us than we’ve made of them,” Bowie told Chris Roberts of Uncut in 2013. “I’m quite Jungian about that. The dream state is a strong, active, potent force in our lives.” Like Dylan, Bowie also drew deep inspiration from dreams. But he stresses to Roberts that dreams are not some escapist fantasy for him:

The fine line between the dream state and reality is at times, for me, quite grey. Combining the two, the place where the two worlds come together, has been important in some of the things I’ve written, yes. That other life, that doppelganger life, is actually a dark thing for me. I don’t find a sense of freedom in dreams; they’re not an escape mechanism. In there, I’m usually, “Oh, I gotta get outta this place!” The darker place.

Dreams are a place for confronting the shadow side of existence, which is precisely their function in Lazarus.

In Blackstar Theory: The Last Works of David Bowie, Leah Kardos argues, “There are clear indications in the script and staging of Lazarus that suggest what the audience is experiencing is a dream sequence. The show begins and ends with Newton lying in the same location on the floor with his eyes closed” (112). Playwright Walsh confirmed that we are meant to understand the stage as Newton’s internal dreamscape. He told Paul Trynka of Mojo that the set of Lazarus, a beige room with two windows, was “‘not an apartment; it’s a head, a mind’” (qtd. Kardos 113).

Interestingly, Dylan used a similar approach in his film Renaldo & Clara. As he confided to Allen Ginsberg:

The man on the floor at the end is the Dreamer. That’s neither Renaldo nor the Chorus nor the man on the stage—the stage is part of the Dream. A man who’s walking around seeming to be alive has dreamt nothing. But the man on the floor, who’s obviously dreaming, no one asks him anything—but the whole movie was his dream. (Ginsberg 526)

Bowie described his approach to dreams as “quite Jungian,” which is compatible with Dylan’s treatment of the shadow self in several songs, as discussed in Part 2 of this series. Leah Kardos offers a compelling Jungian interpretation of Lazarus. Take for instance the sadistic character Valentine. According to Kardos, “Valentine’s bitterness at his isolated and loveless existence has given him the twisted psychology of a mass shooter (the point of view portrayed in the lyrics to the song ‘Valentine’s Day’), an incel-terrorist soured by loneliness who becomes incensed when he is ignored and sees others enjoying what he believes he can never have” (119).

In another setting, Valentine might simply be regarded as a villain. However, set within the dreaming mind of Newton, it is more accurate to see him as Newton’s shadow self. Kardos argues, “Valentine’s villainy is clearly announced as archetypal within the context of the play, which raises the suggestion that other main characters might also be visionary figments from Newton’s fragmented psyche” (99). Describing the figure in Jungian terms, Kardos asserts, “The murderous Valentine is the shadow figure of the piece […]. He is everything that Newton’s conscious ego does not identify itself with: wildly emotive, decisive and vengeful” (118).

I find Kardos’s argument persuasive, and it makes me think differently about some of Dylan’s late works, too. I have frequently written about the stalkers and killers populating several Dylan songs from Time Out of Mind onward. I have focused primarily upon those “sickos disguised as Romeos” in relation to the murder ballad tradition. I still believe that’s true, insofar as the argument goes. But I now realize that, in a larger sense, Dylan is confronting the dark side in these songs—not necessarily his own dark side, but the archetypal shadow side of the culture, or the collective unconscious as Jung would have it.

Kardos also invokes Jung in her reading of Lazarus’s conclusion, which she sees as a revision or correction of both the novel and movie versions of The Man Who Fell to Earth. “The book and film leave Newton’s fate in stasis—damaged and rendered impotent by humanity, he cannot complete the ‘hero’s journey’ and return to his realm with the reward he set out to find” (117). Newton lies back down on the ground, probably suggesting his death.

In a different play, this might be a tragic ending. However, viewed through a Jungian lens, Kardos sees the conclusion as a psychological triumph:

Newton’s heroic ending is finally written and the quest is completed. Newton accomplishes his life-enhancing return by achieving union with the self, even if it is only momentary (just for one day). In triumphing over his bullying mind, he achieves what Jungian psychology refers to as individuation, a transformative process of self-actualization brought about by the integration of the disparate elements of the personality into an assimilated well-functioning whole. The moment of Newton’s death is also the moment of his departure back to the stars […], lifting the dead man up and out of his cage on Earth and on to the next place. (125)

As if to support this interpretation of Jungian self-actualization and completion of the hero’s quest, the final song of Lazarus is a stirring rendition of Bowie’s “Heroes.”

Blackstar: The Shadow of Death

In her poem “Lady Lazarus,” Sylvia Plath famously declares: “Dying / Is an art, like everything else. / I do it exceptionally well.” Forty years before he died, David Bowie told Cameron Crowe: “I’ve decided that my death should be very precious. I’d like my death to be as interesting as my life has been and will be.” Mission accomplished.

On January 7, 2016, Bowie released a haunting video for “Lazarus,” a song that premiered on stage a month prior. On January 8th—his 69th birthday—he released his final album Blackstar. Two days later he died. The opening lines of “Lazarus” were instantly transformed into a posthumous oracle from the deceased artist:

Look up here, I’m in heaven

I’ve got scars that can’t be seen

I’ve got drama, can’t be stolen

Everybody knows me now

Look up here, man, I’m in danger

I’ve got nothing left to lose

But the song isn’t entirely morbid. The echo of The Wizard of Oz in “Life on Mars?” is even more pronounced in “Lazarus”: “Just like that bluebird / Now ain’t that just like me / Oh, I’ll be free.” Look up here, I’m over the rainbow.

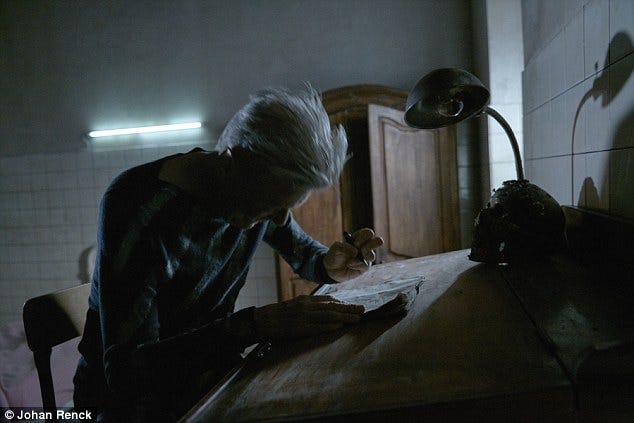

The video was directed by Johan Renck. During preparations for the shoot, Bowie privately informed the director that he was dying. Renck later told biographer Dylan Jones,

I don’t think he told me only so I could figure out what to do on the practical level for the video, to find a replacement for him, I really think he told me because he wanted death to be a third collaborator in this video; he wanted death to be there as a presence in terms of formulating all the ideas and lying as a middle instigator for his thoughts as we went onwards. (Jones 478)

That’s the thing about both Lazarus and Blackstar: Bowie’s final act is so devastating—he’s dead!—and yet so beautiful—what an exit! As Simon Critchley so eloquently observed,

Despite its massive and obvious sadness, Bowie’s was the best of deaths. If there was ever the “good” death of a major cultural figure, a dignified death, then this was it. If a death can be a work of art, a statement completely consistent with an artist’s aesthetic, then this is what happened on January 10th, 2016. Bowie turned death into art and art into death. He didn’t die a dumb rock-star death at the age of twenty-seven. Nor did he fade out in a fog of addiction, decay and disgrace, leaving his fans to shore together fragments of a ruined life. This was a noble death in the gift of privacy with all of his fans listening to his new album. (177-78)

There are many gifts hidden in Blackstar and left for us to delight over and debate. Consider the title, which technically isn’t a word but a symbol. On the album cover, designed by Jonathan Barnbrook, the black star is dissected at the bottom to approximate the name BOWIE:

In the title song, the singer repeatedly proclaims: “I’m a blackstar.” What does that mean? Choose your poison: it could refer to a cancerous lesion, or the Jungian shadow, or a theoretical alternative to a black hole, or the planet Saturn, or a day of execution from Peaky Blinders, or a line from Kendrick Lamar’s To Pimp a Butterfly, or an abandoned song by Elvis Presley. It could be any, all, or none of these things—such is the hermeneutics of Bowieology and the elusive/allusive nature of shadow art. Dylanologists can certainly relate.

Blackstar’s avant-garde jazz score sounds amazing. Bowie and producer Tony Visconti saved one of the boldest musical experiments of their long collaboration for the very end. Great athletes refer to “leaving it all on the field,” and that’s just how Blackstar feels. The final track is titled “I Can’t Give Everything Away,” but it feels like this is exactly what Bowie has done. Having given us everything, it’s time to go.

He settles his accounts before leaving. Kardos sums it up effectively in Blackstar Theory: “Long-running themes become enriched by complex intertextual details drawn to the surface of a body of ideas, artistry and myth some fifty years in the making. Archetypal characters—the outsized egos, vulnerable animas, tricksters, tyrants and shadows that lurk in the catalogue—are confronted. Karmic ledgers are balanced. The dead are taken for one last walk” (171). Now you can seal up the book and not write anymore.

Bowie’s Shadows in Rough and Rowdy Ways

The year after Bowie died, Michael Cunningham published a remarkable essay in GQ titled “Stage Oddity: The Story of David Bowie’s Secret Final Project.” Sometime before the collaboration with Walsh on Lazarus, Bowie approached Cunningham about writing the book for a musical. Some of the elements Bowie proposed were identical to those that eventually appeared in Lazarus. But Bowie pitched Cunningham one other stunning idea—get a load of this: “David reluctantly told me that he imagined the musical taking place in the future. The plot would revolve around a stockpile of unknown, unrecorded Bob Dylan songs, which had been discovered after Dylan died. David himself would write the hitherto-unknown songs.”

What?!

Cunningham took this wild suggestion in stride: “Who could write a convincing fake Dylan song? Well, okay, that would be David Bowie, if anyone, but who (including David Bowie) would want to? And how would the actual Bob Dylan feel about that?” Your reaction is way calmer than mine, Mr. Cunningham. This blows my mind! Maybe I was too quick to declare a ceasefire in the old shadow rivalry, since this proposal sounds like the Oedipus complex and the anxiety of influence all rolled into one. Bowie fantasizes about killing Dylan off so that he can write his songs for him!

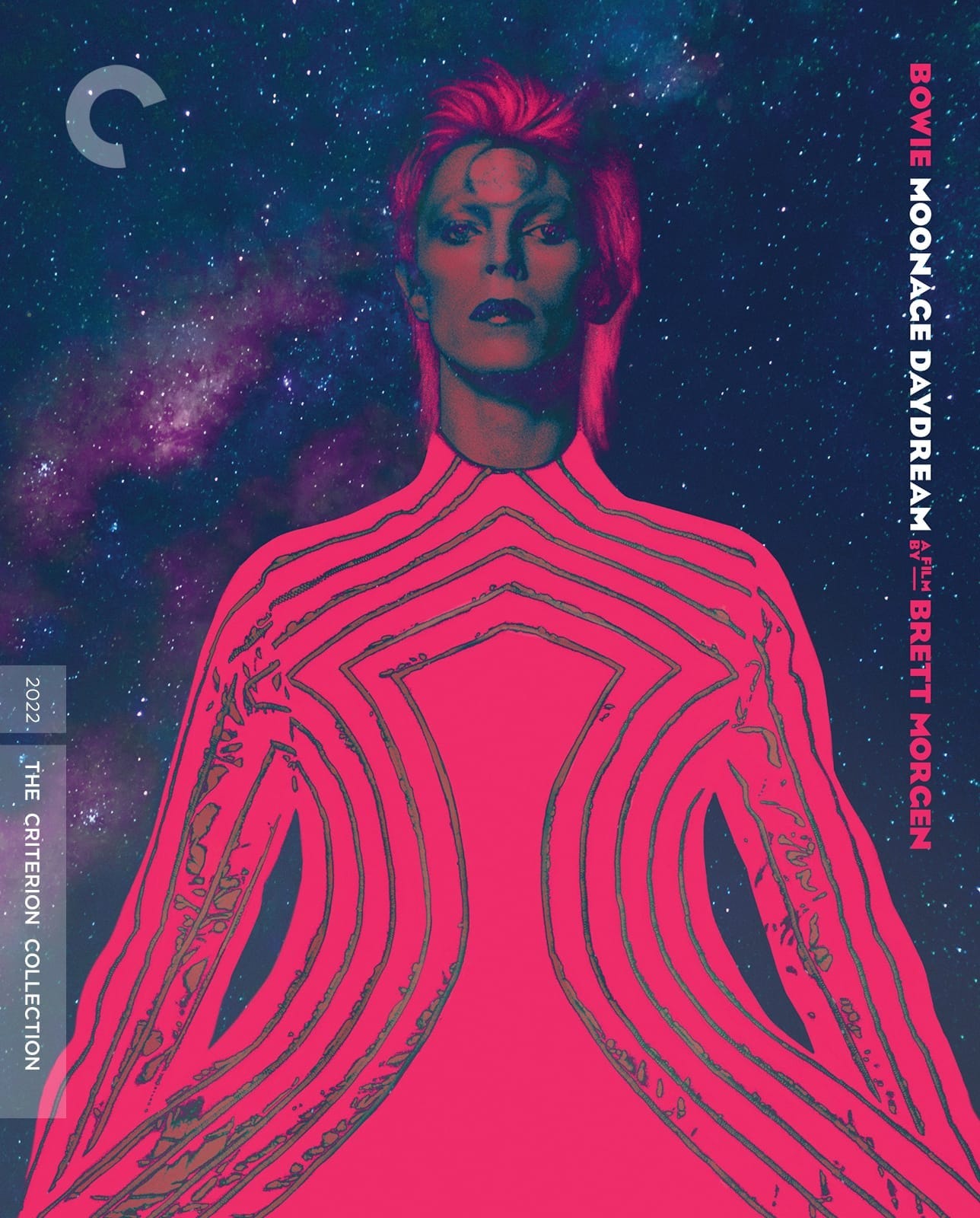

Unfortunately, Bowie fell ill with heart trouble and the planned musical with Cunningham fell through. It’s a shame that Bowie never followed through on his imaginary collaboration with/as Dylan. But in a way Dylan might have returned the favor on Rough and Rowdy Ways. I’m not suggesting that Dylan was trying to write a Bowiesque batch of songs (though he does namecheck Bowie’s “All the Young Dudes” in the opening track “I Contain Multitudes”). But I am proposing that, on an album packed with allusions, an album that resurrects the dead and takes them on a stroll through the graveyard, one of the significant shades haunting RARW is Bowie.

I love Moonage Daydream, Brett Morgen’s 2022 film about Bowie. As a Dylan fan, I was especially struck by Bowie’s comments to Mick Rock in 1972 about the shadowy nature of rock gods:

The artist doesn’t exist. The artist is strictly a figment of the people’s imagination. Dylan is, Lennon is, I will be, Jagger is. All figments. They don’t exist. None of ’em exist. None of us exist. We’re in the Twilight Zone. We’re the original false prophets. We are the gods. We’re the new gods that were gonna—you know, we’re going to hell. We set ourselves up as such. We want it all. You know, we want all the adulation, for people to read the lyrics and just play the game. I feel that same emptiness they all feel when they get there. ’Cause they know that it’s not real. It has nothing to do with them.

Readers of Shadow Chasing will laser in on Bowie’s reference above to “false prophets.” Surely Dylan is aware of this pronouncement, where Bowie calls him out by name, but I doubt that he agrees entirely with the sentiment. As Dylan writes in Chronicles, “Legend, Icon, Enigma (Buddha in European Clothes was my favorite)—stuff like that, but that was all right. These titles were placid and harmless, threadbare, easy to get around with them. Prophet, Messiah, Savior—those are tough ones” (124). In his RARW song “False Prophet,” he repeatedly insists, “I ain’t no false prophet.” No, no, no, it ain’t me, Dave.

To be fair, Bowie ultimately seems to deconstruct the myth of rock deity. It’s an illusion, a figment—a shadow projected by worshippers to fill the god-shaped void in their lives. By 1972, Bowie’s Ziggy had ascended to the same pantheon as Dylan, Lennon, and Jagger, and from that vantage point he sees what they already knew: “It’s not real. It has nothing to do with them.”

Needless to say, neither Bowie nor Dylan invented the term “false prophet,” so it could simply be a coincidence that they both use this phrase. But I don’t think so. As many listeners have noted, Dylan conjures up Ricky Nelson in “False Prophet” with the line “Hello Mary Lou – Hello Miss Pearl / My fleet-footed guides from the underworld.” This is of course a reference to the 1961 hit “Hello Mary Lou” by Ricky Nelson. In a previous piece for this site, I explored Dylan’s admiration for and identification with Nelson, as reflected in both Chronicles (13-14) and The Philosophy of Modern Song (48-53).

Lazarus contains 22 songs by David Bowie. But there is one composition not by Bowie, and it is the very first song in the play. Here are the opening stage directions: “In the darkness a sudden cacophony of televisual sounds is heard. It lights NEWTON – he sits detached – staring into a screen – the television switching between channels – Ricky Nelson’s ‘Hello Mary Lou (Goodbye Heart)’ skips/repeats in broken pieces. The sounds mix, distort and escalate—until suddenly they snap into silence” (4). “Hello Mary Lou”! The song was also used in the film The Man Who Fell to Earth, referring to one of the main characters, Newton’s earthling girlfriend Mary-Lou.

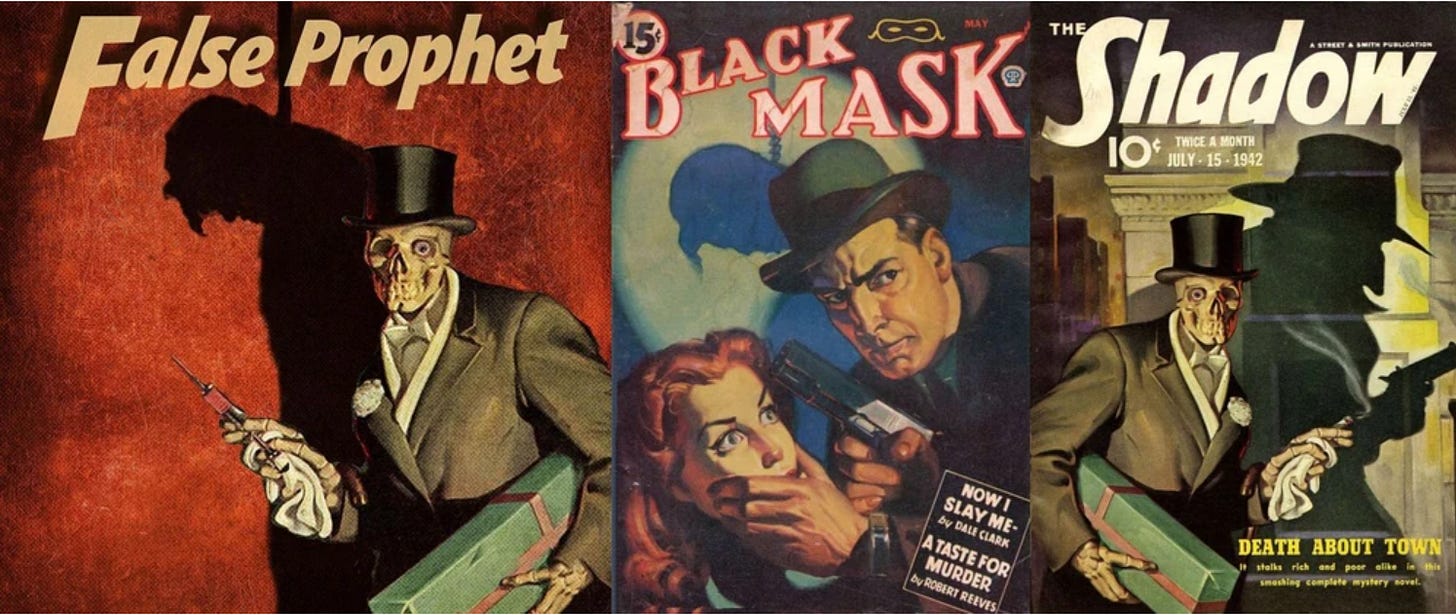

Along with the conceptual callback to “false prophets” and the shared musical echo of “Hello Mary Lou,” I sense Bowie’s shadow behind the song’s promotional imagery, too. Remember that “False Prophet” was released as a single before the album came out. The cover art featured a spooky skeleton, and this figure was eventually adopted for the RARW Tour poster as well. Dylanologists quickly tracked down the source to a couple pulp fiction covers:

It’s a cool mash-up. “False Prophet” takes the skeleton from the “Death About Town” issue of The Shadow—of course it would be The Shadow!—reverses it, and replaces the smoking cigarette with a lethal needle (or is it a Covid shot?). Then the art designer removes the shadow of death in the form of a gunman and replaces it with the shadow of a hanged man from the cover of Black Mask. Clever. However, is it just my imagination, or do you also see resemblances to the cover photo from Bowie’s Scary Monsters (And Super Creeps)?

I doubt that photographer Brian Duffy was intentionally posing Bowie’s Pierrot to mirror the skeleton in The Shadow, but the resemblance is uncanny just the same, right down to the dangling cigarette. As for the distinct shadow on Dylan’s cover, some observers are convinced that this is a veiled allusion to Donald Trump being hanged as a false prophet. To my mind, however, the floppy-haired silhouette might just as well gesture toward the self-professed false prophet David Bowie. Scary times call for Scary Monsters. I look at those cover images above and I think of the chorus from Bowie’s 2013 song “The Next Day”:

Here I am, not quite dying

My body left to rot in a hollow tree

Its branches throwing shadows on the gallows for me

And the next day, and the next, and another day

Bowie’s overarching emblem for death on his final album is the Black Star. On RARW, Dylan offers his own allegory for death in the Black Rider. There’s an unholy mixture of sex and death in Dylan’s “Black Rider.”

As you know, “riding” can refer to having sex, and the singer clearly views the Black Rider as a sexual rival: “Go home to your wife stop visiting mine.” The accusation is even more graphic in the final verse: “Black Rider Black Rider hold it right there / The size of your cock will get you nowhere.” On Blackstar, Bowie uses comparable language in “’Tis a Pity She Was a Whore”: “Black struck the kiss, he kept my cock.” The swordplay isn’t just verbal in these songs.

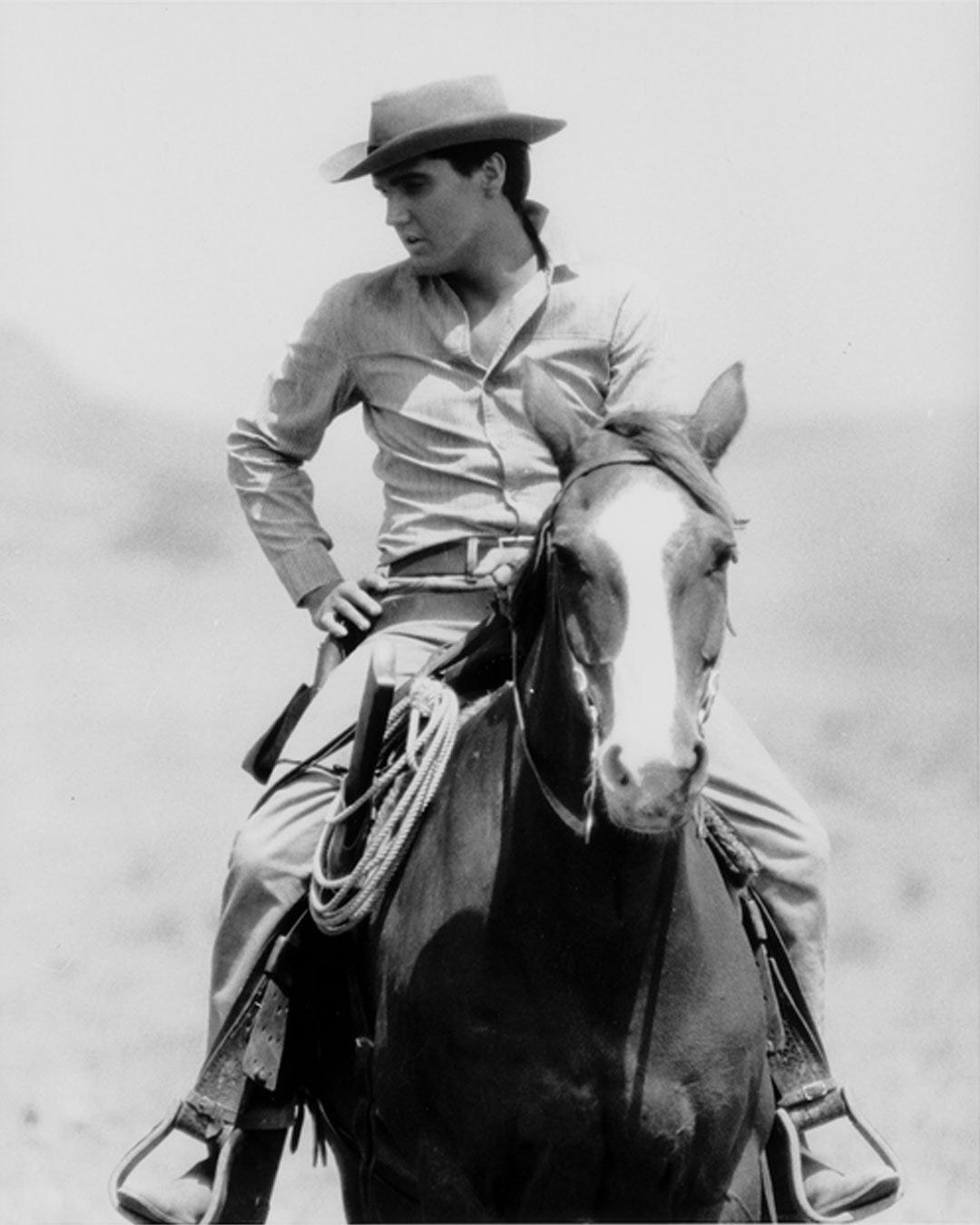

But what’s most interesting here is how Dylan and Bowie are both measuring themselves against the king—Elvis Presley. I’ve already written about Presley’s importance for Dylan, so I won’t repeat myself. Elvis was also one of Bowie’s heroes, and not just because they shared a birthday. The flamboyantly transgressive performances of Little Richard and Elvis Presley had a formative influence on Bowie’s Ziggy Stardust persona. When he replaced Ziggy with Aladdin Sane, he signaled his debt by painting Elvis’ “Taking Care of Business” thunderbolt logo across his face.

Bowie allegedly wrote “Golden Years” to be performed by Presley. Although that coveted cover never came to pass, you can hear Bowie lapsing into an Elvis impression at times in the song. Bowie’s penultimate album The Next Day contains the song “You Feel So Lonely You Could Die,” obviously an echo from Presley’s hit “Heartbreak Hotel.”

The song most relevant to Blackstar and Rough and Rowdy Ways was not a hit, however, but an obscure deep-cut. In 1960, Elvis starred in a forgettable Western movie called Flaming Star. The working title had been Black Star, and a theme song was written by Sid Wayne and Sherman Edwards and recorded by Elvis. Once the film changed names, the earlier track was shelved and replaced, but the outtake was eventually released in 1991. It’s pretty remarkable to listen to Presley’s “Black Star” in light of Bowie and Dylan’s subsequent appropriations.

Every man has a black star

A black star over his shoulder

And when a man sees his black star

He knows his time, his time has come

When I ride I feel that black star

That black star over my shoulder

So I ride in front of that black star

Never lookin’ around, never lookin’ around

Black star don’t shine on me, black star

Black star keep behind me, black star

There’s a lot of livin’ I gotta do

Give me time to make a few dreams come true

Black star

Elvis galloping across the Valley of the Shadow of Death with his Black Star in hot pursuit—what an image! It’s easy to see how “Black Star” would have spoken with fresh urgency to Bowie while he was dying of cancer. It also appears to serve as a prototype for the cowboy Grim Reaper in “Black Rider.” Elvis is the mutual source of inspiration here, but Bowie got there first. He chased down “Black Star,” then the Black Star chased him down. Dylan took it from there, saddling up the song for one more ride.

One of the most poignant shared elements of Blackstar and Rough and Rowdy Ways is the way Bowie and Dylan reach out to listeners. Both artists reinforce the ties that bind them to their respective audiences. This is especially moving in Bowie’s case, since he knew that death was imminent. Take for instance these piercing lines from the penultimate track “Dollar Days”:

Don’t believe for just one second

I’m forgetting you

I’m trying to

I’m dying to

There’s no way to listen to these words now without hearing them as Bowie’s direct message from beyond the grave. Listen to the final song, “I Cant Give Everything Away,” and it feels like Bowie is carving his own epitaph for mourners to read after his death:

Seeing more and feeling less

Saying no but meaning yes

This is all I ever meant

That’s the message that I sent

Simon Critchley fixes upon that affirmation, of saying no but meaning yes, in On Bowie:

At the core of Bowie’s music and his apparent negativity is a profound yearning for connection and, most of all, love. What was being negated by Bowie was all the nonsense, the falsity, the accrued social meanings, traditions and morass of identity that shackled us, especially in relation to gender and class. His songs revealed how fragile all these meanings were and gave us the capacity for reinvention. (171)

The heart of Bowie’s appeal was always that deep and loving connection with his audience. They were each other’s mirrors, each other’s shadows. You’re not alone!

Bowie orchestrates Blackstar as a farewell note and final love letter to his audience. Commenting specifically on “Dollar Days,” Critchley observes,

The phrase at the beginning of the song, ‘I’m dying to push their backs against the grain,’ resolves into the song’s final words ‘I’m dying to(o).’ The words seemed to undergo a shift in meaning as I listened to them. He too knew that he was dying and he was telling us: ‘I’m falling down.’ Bowie was also telling us that he wouldn’t forget us, his audience, his fans, those who had loved him. (180-81)

Dylan didn’t need Bowie to die in order to understand the importance of his own audience. But Blackstar does offer an inspiring example of an artist renewing his vows to his fans with dignity, grace, and emotional gravitas. I imagine the record on Dylan’s turntable during the pandemic, spinning straw into gold, death into life, a perfect final album, worthy of admiration and emulation.

Fortunately for us, Dylan didn’t follow Bowie’s lead by releasing a final masterpiece and then dying. Quite the contrary, Rough and Rowdy Ways gave him a new lease on life. His relentless commitment to touring proves just how much the vital connection with listeners means to him, and to us. Fans frequently describe the RARW Tour like a quasi-religious experience, as if the crowd is a congregation gathered to worship and to take the holy communion of Dylan’s live performances. The song that epitomizes this experience most powerfully on a nightly basis is “I’ve Made Up My Mind to Give Myself to You.”

It’s a song of commemoration for friends and comrades like Bowie who have passed on: “A lot of people gone, a lot of people I knew.” But when Dylan performs it live in front of an audience, there can be no doubt that he is addressing it to us, his adoring fans: “I knew you’d say yes – I’m saying it too / I’ve made up my mind to give myself to you.”

Bonus Track: “Shadow Man”

I’ve been saving one final Bowie song to end with: “Shadow Man.” Bowie was still preoccupied with shadow rivalries in late 1971 when he wrote and first recorded “Shadow Man” for the Ziggy Stardust sessions. There is an early demo version, as well as an alternative version which is includes echo and vocal distortions. The song did not make the cut for The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars. However, Bowie kept returning to it. In 2000, he re-recorded it for the abandoned Toy album, and it was later released in 2002 as a B-side for Heathen. This version was re-released in 2022 as part of the posthumous Toy (Toy:Box), which also included a 2021 remix by Tony Visconti. The alternate Ziggy mix was released in 2024 on Rock ’n’ Roll Star! It feels appropriate that this song remained obscure for many years and yet persistently followed Bowie around like a shadow.

“Shadow Man” is Bowie’s most overt musical treatment of the shadow trope. The singer identifies “a guy who can’t be seen” as the Shadow Man. Though he goes by many names, they are all aliases for the shadow self:

You can call him Joe, you can call him Sam

You should call and see who answers

For he promises to come running, guided by the truth

For the Shadow Man is really you

You can call him Zimmy, or you can call him Ziggy. Or, in the words of Bowie’s song, “You can call him foe, you can call him friend.” What you cannot do is put off the confrontation with the shadow forever. “He’s waiting up ahead / Shadow Man.” Commenting on this song in 1989, Bowie was quite explicit about his intentions: “‘it’s a reference to one’s own shadow self’” (qtd. O’Leary, Rebel 211).

Within the world of Hunky Dory, that shadow encompasses doppelgangers like Warhol and Dylan. Within the world of Ziggy Stardust, the Shadow Man morphs into the Starman: “There’s a starman waiting in the sky / He’d like to come and meet us / But he thinks he’d blow our minds.” Later arrangements of the song are imbued with pathos. Since January 10, 2016, it’s impossible to hear “Shadow Man” without sensing the shadow of Bowie’s death. Tony Visconti’s 2021 haunting remix delivers all the pathos of a requiem mass:

The brash iconoclastic Bowie once rushed headlong into the future, the winds of change blowing strong at his back. “Run for the shadows in these golden years.” But eventually the Shadow Man beckoned him to make his final journey across the borderline. Bowie left Blackstar behind and then crossed over.

Dylan issued Rough and Rowdy Ways four years later like a man preparing to make that same journey. Thankfully, he still has promises to keep and miles to go before he sleeps. The Shadow Man will have to wait a while longer. Still, mortality inevitably awaits us all. The Black Rider bides his time, with steely eyes and infinite patience, watching the Black Star and listening for our approach, ready to usher each of us across the threshold into the hereafter. “He’s waiting up ahead / Shadow Man.”

Works Cited

Bowie, David. Blackstar. Columbia, 2016.

---. Hunky Dory. RCA, 1971.

---. The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars. RCA, 1972.

---. Scary Monsters (And Super Creeps). RCA, 1980.

--- and Enda Walsh. Lazarus. Theatre Communications Group, 2016.

Countdown Interview with David Bowie, 1990,

.

Critchley, Simon. On Bowie. Serpents Tail, 2016.

Crowe, Cameron. Interview with David Bowie. Playboy (September 1976), http://www.theuncool.com/journalism/david-bowie-playboy-magazine/.

Cunningham, Michael. “Stage Oddity: The Story of David Bowie’s Secret Final Project.” GQ (9 January 2017), https://www.gq.com/story/david-bowie-musical.

Dylan, Bob. Chronicles, Volume One. Simon & Schuster, 2004.

---. Official Lyrics. The Official Bob Dylan Website.

https://www.bobdylan.com/.

---. The Philosophy of Modern Song. Simon & Schuster, 2022.

Ginsberg, Allen. Interview with Bob Dylan (September-November 1977). Rpt. in Every Mind Polluting Word: Assorted Bob Dylan Utterances. Ed. Artur Jarosinski. Don’t Ya Tell Henry, 2006, 524-33.

Hilburn, Robert. “Bowie: Now I’m a Businessman.” Melody Maker (28 February 1976), https://www.bowiegoldenyears.com/press/76-02-28-melody-maker.html.

Inspirations. Directed by Michael Apted. Argo/Clear Blue Sky, 1997.

Jollett, Mikel. “Such a Perfect Day.” Filter (July/August 2003). Rpt. Bowie on Bowie: Interviews and Encounters. Ed. Sean Egan. Chicago Review Press, 2015. 386-93.

Jones, Dylan. David Bowie: A Life. Crown, 2017.

Kardos, Leah. Blackstar Theory: The Last Works of David Bowie. Bloomsbury Academic, 2022.

Lindsay, Matthew. “Making David Bowie: Scary Monsters (And Super Creeps).” Classic Pop (10 April 2025), https://www.classicpopmag.com/features/classic-album/making-david-bowie-scary-monsters-and-super-creeps/.

Moonage Daydream. Directed by Brett Morgen. Universal Pictures, 2022.

O’Leary Chris. Ashes to Ashes: The Songs of David Bowie, 1976-2016. Repeater, 2018.

---. Rebel Rebel. Zero Books, 2015.

Pegg, Nicholas. The Complete David Bowie, 5th edition. Reynolds & Hearn, 2009.

Plath, Sylvia. “Lady Lazarus.” Poetry Foundation, https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/49000/lady-lazarus.

Roberts, Chris. “‘I’m hungry for reality!’ – Part 4.” Uncut (8 January 2013), https://www.uncut.co.uk/features/david-bowie-i-m-hungry-for-reality-part-4-27210/.

Rook, Jean. “Waiting for Bowie.” Daily Express (5 May 1976), https://www.bowiegoldenyears.com/press/76-05-05-daily-express.html.

Steiner, Adam. Silhouettes and Shadows: The Secret History of David Bowie’s Scary Monsters (And Super Creeps). Backbeat, 2023.

Waldrep, Shelton. Future Nostalgia: Performing David Bowie. Bloomsbury Academic, 2015.

Watts, Michael. “Confessions of an Elitist.” Melody Maker (18 February 1978). Rpt. in Bowie on Bowie: Interviews and Encounters. Ed. Sean Egan. Chicago Review Press, 2015. 77-101.

This was a great read Graley. I was enjoying it so much I missed my train stop.

“…but for those with the “terror of knowing”, bright light casts dark shadows and the eternal paradox lies in discerning which one is which…”