The Dylan Review recently published several papers from the “Bob Dylan – Questions in Masculinity” Symposium, organized by Anne-Marie Mai and Erin Callahan in May 2024 in Odense, Denmark. It was a wonderful conference, and I appreciate The Dylan Review for sharing our work with a larger audience. My original presentation was accompanied by several images that I wasn’t able to include in the journal article. As a special bonus for Shadow Chasing readers, I’m posting this illustrated version of the paper.

The Philosophy of Modern Song chronicles how Bobby Zimmerman used music and pop culture to transform himself into Bob Dylan. The novelist Ralph Ellison pointed out that “while one can do nothing about choosing one’s relatives, one can, as artist, choose one’s ‘ancestors’” (140). Dylan’s book is a tribute to his chosen ancestors. He assembles an eclectic group of 66 songs and imagines his way into them through idiosyncratic riffs and commentaries. The book’s title implies that if you listen to these songs and read Dylan’s reflections, you’ll get a mosaic self-portrait of his “philosophy of modern song.”

In the process, you can also learn a lot about his philosophy of masculinity and gender performance. The Philosophy of Modern Song chronicles his education from several groundbreaking artists in the 1950s. These mentors and chosen ancestors taught him to question, resist, and reimagine gender, rejecting a rigid, narrow, stable essence of masculinity in favor of shifting performances across a spectrum.

You couldn’t find a better image for communicating these concerns than the cover photo. Pictured on the left is pioneering rocker and queer icon Little Richard; in the middle is Alis Leslie, nicknamed “the female Elvis”; and on the right is rockabilly star Eddie Cochran. Think of the cover like a radio dial of gender, with Dylan at the knob, moving back and forth from station to station throughout the book. In this piece I’d like to tune into some of the strongest frequencies for young Bobby in the fifties, as rebroadcast by old Dylan in 2022.

Marlon Brando & James Dean

In her book The Male Body: A New Look at Men in Public and in Private, feminist philosopher Susan Bordo recalls Dylan’s influence on the young men of her generation.

Among popular entertainers, the only one whose style of masculinity they consciously emulated was that of folk singer Bob Dylan, who combined poetry, domestic rebellion, and anti-establishment passion with lousy posture, a Salvation Army wardrobe, a voice that defied convention, and a sense of indifference to his audience, even when bellowing lyrics of protest. My friends slouched like Dylan, they mumbled like Dylan, they scoured the Newark thrift stores in search of Dylan-like clothing. (132)

Bordo points out that Dylan’s sixties persona was an amalgamation of fifties trailblazers: “What most of them didn’t know, however, was that young Robert Zimmerman, and many other singers and public politicos of the sixties, just slightly older than the boys I knew, had gotten their inspiration from two movie stars of the fifties: Marlon Brando and James Dean” (132).

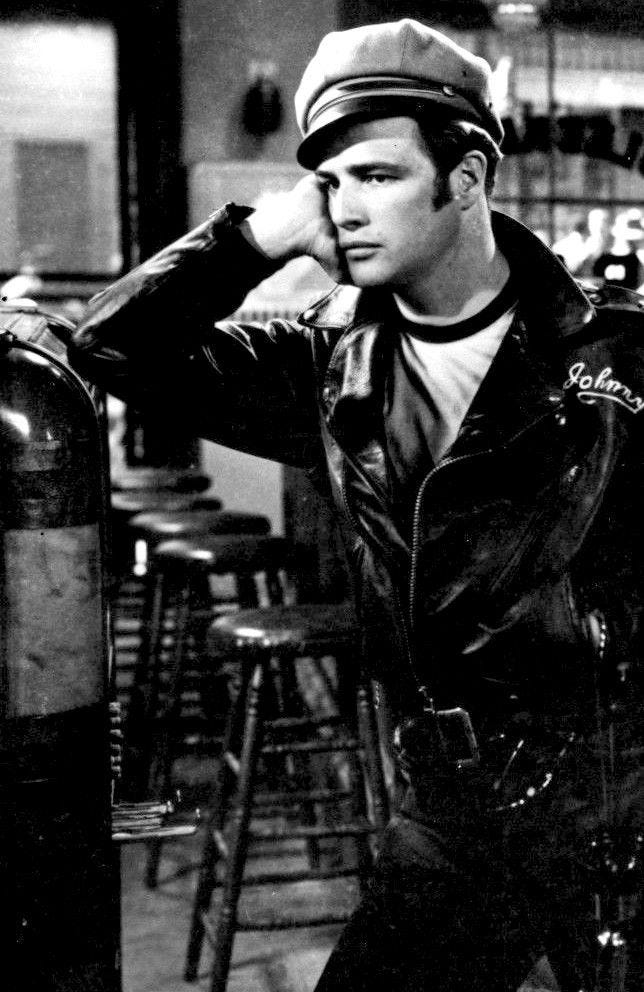

Brando first achieved recognition in 1947 for his brutish but irresistible performance as Stanley Kowalski in Tennessee Williams’s play A Streetcar Named Desire. But it was his volcanic eruption in Elia Kazan’s 1951 film adaptation that turned Brando into a celebrity. Two years later, in his starring role as Johnny Strabler in The Wild One, the leather-clad Brando astride his Triumph motorcycle became the face, voice, pouting lips, and rippling chest of youth rebellion.

In his commentary on The Who’s “My Generation” for The Philosophy of Modern Song, Dylan credits Brando with sounding a clarion call for his generation:

Marlon Brando, like Elvis Presley, Little Richard, and the first wave of rockers, fell somewhere between the greatest generation ever and the baby boomers; too young to fight against the Nazis, too old to go to Woodstock. Yet when Brando replied, “Whaddaya got?” when a local girl asked him what he was rebelling against in the movie The Wild One, it set the stage for the sixties and the rebellion against the picture-perfect prefab communities the boys came home from the war to build. (43-44)

It wasn’t just the communities that were picture-perfect and prefabricated, it was the boys themselves. One of the main things Brando rebelled against was the era’s smothering codification of correct masculinity.

In his book Rebel Males: Clift, Brando and Dean, Graham McCann observes, “Brando’s character [in The Wild One] epitomized an entire subculture that was fast spreading in America at that time—the drifting gang. Johnny inspired many young men in search of a role model, including Dylan, Presley and Dean. The cool, self-confident pose adopted by Johnny disguises a person who is actually profoundly insecure and confused” (106). The insecurity behind the tough-guy front would later become a hallmark of Dylan’s songs and performances, as it was for Brando, who combined irrepressible sexual vitality with the neediness and fragility of a child.

In the case of Brando’s Johnny, the character’s rebellion and confusion wasn’t just existential: it was also gendered. Graham McCann asserts, “From his first appearance, leading the swarm of motorcycles, this man/boy lone ranger is established as a figure of considerable force. Johnny appeals to men and women alike, and while this is never openly expressed by the character himself, there are unmistakable signs that he needs the adoration of both sexes” (106).

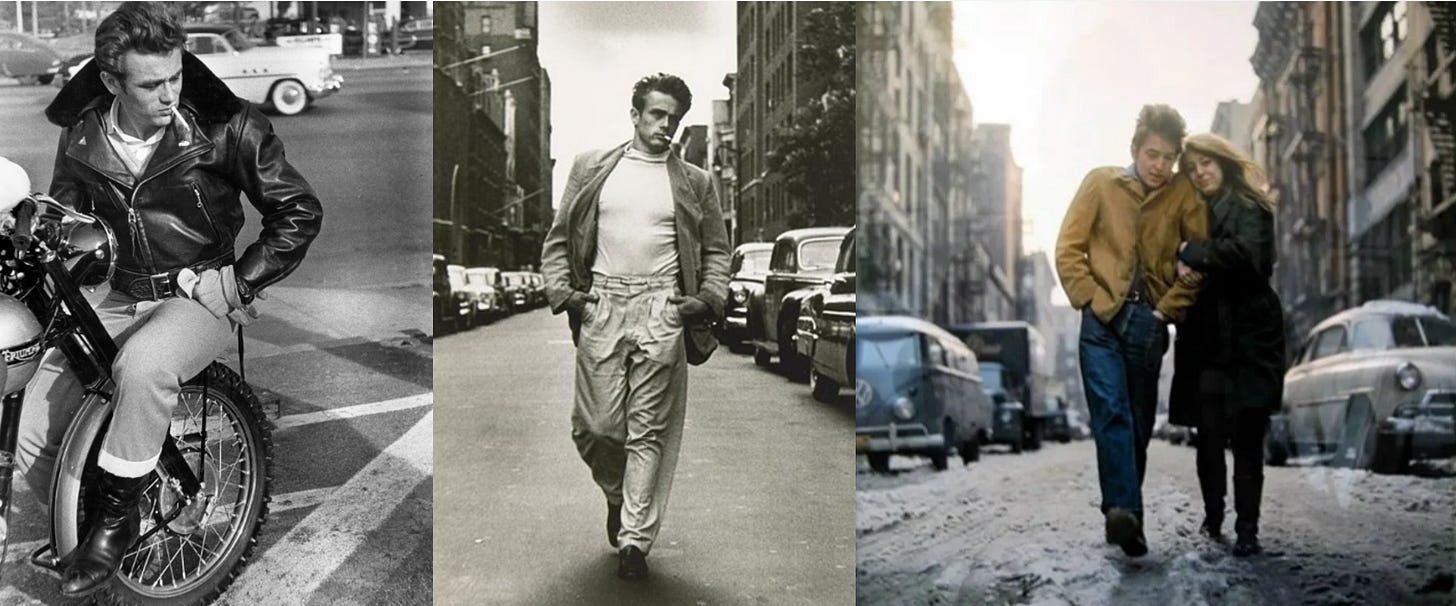

One man who obsessively adored Brando was James Dean. He only appeared in three films before his life was cut short by a car crash at age 24, but his performances in East of Eden, Rebel Without a Cause, and Giant, the latter two released after his death, were enough to secure his mythological status for Bobby Zimmerman’s generation. The screen icon’s influence was readily apparent in Dylan’s mannerisms, mumbles, and clothing, later immortalized by Don McLean in his verse about Dylan for “American Pie”: “The jester sang for the king and queen / In a coat he borrowed from James Dean / And a voice that came from you and me.” Dean broke just like a little boy, and that raw emotion spoke urgently to fifties teens like Bobby Zimmerman.

Dylan’s most extensive treatment of Dean in The Philosophy of Modern Song comes in the chapter on Vic Damone’s “On the Street Where You Live.” He writes of Dean’s heartbreak when Pier Angeli, the love of his life, suddenly dumped him to marry Vic Damone. Dylan describes Dean stalking his ex after their breakup, including a story “that he waited across the street on his motorcycle on Pier Angeli’s wedding day” (135). The passage conjures up images of Johnny Strabler, inviting comparison to Dean’s other abiding obsession for Brando.

In a published 1957 conversation with Truman Capote, Brando complained about being stalked by Dean, who mimicked his every move, followed him around, and repeatedly left him messages. Brando eventually confronted Dean, told him he was sick, and recommended professional help. In essence, go away from my window, it ain’t me you’re lookin’ for, babe. Brando told Capote that Dean was no hero but “a very lost boy trying to find himself” (qtd. Colavito).

Dylan includes pictures of Dean and Angeli in The Philosophy of Modern Song, but in the present context I’m more intrigued by the few available photos of Dean and Brando. For instance, check out their meeting, arranged by director Elia Kazan, on the set of East of Eden.

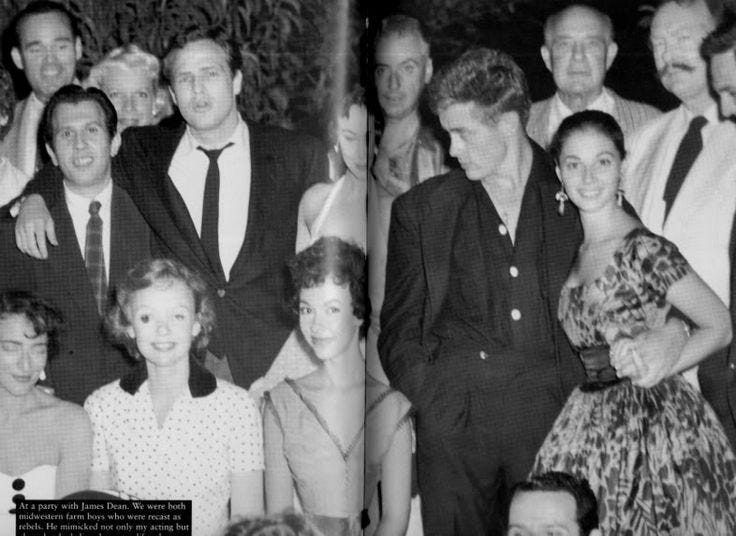

Or look at this party photo, where Dean has Angeli on his arm but only has eyes for Brando.

For what it’s worth, Patricia Quinn claims that Dylan felt the same way about Brando. Quinn, who dated both men, said in an interview that Dylan “‘adored, idolized [and] was terribly attracted to Marlon’” (qtd. Bordo 133). It’s interesting to see the gaze pointed in the other direction in this photo of the three:

I’ve written elsewhere about Dylan’s signature approach in The Philosophy of Modern Song as “the art of the unsaid,” and here’s yet another example. Overtly, Dylan writes about Dean’s adoration of Pier Angeli. But between the lines and behind the pictures, I spy with my little eye gestures toward other obsessions and loves, implying the love that dare not speak its name from the celluloid closet of fifties America.

Little Richard

In his book Sissy Insurgencies: A Racial Anatomy of Unfit Manliness, Marlon B. Ross studies men of color who infiltrated white heteronormative society and challenged predominant attitudes toward masculinity. According to Ross, “Little Richard’s snarling, popping, screeching erotic noise announces the arrival of the black sissy not exactly as a credit to the race, but as a flaunting presence whose racialized homoeroticism cannot be totally shamed or purged” (214).

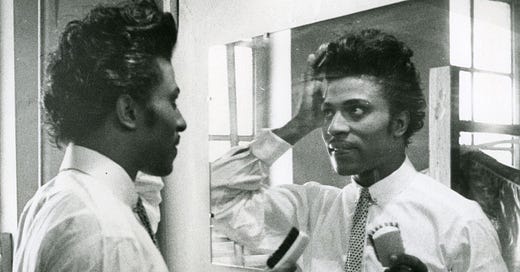

The pink-tinted book cover features Little Richard in all his magnificence, with hair, makeup, and clothes all perfectly on point. “Little Richard’s marcelled hairstyle goes a couple of steps beyond the style worn by black men of the time. The ring of curls sits atop his head like a crown, and his carefully groomed eyebrows and moustache emphasize his self-presentation as a pretty, sissified man, one not afraid to broadcast it to the world” (Ross 214).

Bobby Zimmerman’s pompadour in high school wasn’t quite as wild, but it was probably as close as he could get away with at Hibbing High in 1959. Remember that his yearbook also declared his post-graduation aspiration “to join Little Richard.”

Little Richard gained notoriety for several chart-topping hits in the mid-fifties. He first cultivated his talent for titillating audiences in carnivals, revival meetings, and even minstrel shows. As he told biographer Charles White, “Sugarfoot Sam from Alabam was a minstrel show—the old vaudeville type of show. It was quite something. That was the first time I performed in a dress. One of the girls was missing one night and they put me in a red evening gown. I was the biggest mess you ever saw. They called me Princess Lavonne” (24).

Although his background in drag was not widely known among his white teen fan base, it was obvious that Little Richard’s gender ambiguity was as subversive as it was sexy. The performer told his biographer, “We were breaking through the racial barrier. The white kids had to hide my records cos they daren’t let their parents know they had them in the house. We decided that my image should be crazy and way-out so that the adults would think I was harmless” (White 65-66).

Dylan devotes two chapters of The Philosophy of Modern Song to his hero, beginning with “Tutti Frutti.” He identifies Little Richard’s gospel roots as the source of his powerful singing: “A-wop-bop-a-loo-bop-a-wop-bam-boom. Little Richard was speaking in tongues across the airwaves long before anybody knew what was happening. He took speaking in tongues right out of the sweaty canvas tent and put it on the mainstream radio, even screamed it like a holy preacher—which is what he was” (29).

Dylan returns to this point at the end of the entry: “Little Richard was anything but little. He’s saying that something is happening. The world’s gonna fall apart. He’s a preacher. ‘Tutti Frutti’ is sounding the alarm” (30). Voices and bodies long relegated to the shadows were coming out into the spotlight and would no longer be ignored.

Dylan offers an interesting queer reading of “Tutti Frutti”: “Little Richard is a master of the double entendre. ‘Tutti Frutti’ is a good example. A fruit, a male homosexual, and ‘tutti frutti’ is ‘all fruit’” (29).

He supplements this interpretation with a full-page photo of Carmen Miranda (28). The image illustrates her burlesque performance of exaggerated sexuality.

Even better is the 1962 photo he includes of Jet Harris, Little Richard, Gene Vincent, and Sam Cooke, taken during a UK tour (31). Just look at that wink from Little Richard! Here’s a dude who knows just what to do and is eager to prove it. You know something’s happening here but you don’t know what it is, do you, Jet Harris? Then check out Gene Vincent and Sam Cooke. Cooke is one cool daddy, a total charmer, the king of soul, down for whatever with whomever—bring it on home to me!

This photo captures so much about the transgressive, crossover appeal of early rock & roll to its largest audience of white middle-class consumers like Bobby Zimmerman. The new music is hip, dangerous, alluring, and liberating. It’s an initiation and an exodus, out of bourgeois repression and conformity, into taboo realms of sex and freedom.

Ironically, the shortest entry of the book is the one-paragraph chapter on “Long Tall Sally” by Little Richard. Dylan makes some ludicrous connections between the title character and the giants of Samaria and Nephilim described in the Bible. You think the whole entry is going to be no more than a piss-take, but then Dylan closes with a razor-sharp observation: “Little Richard is a giant of a different kind, but so as not to freak anybody out he refers to himself as little, so as not to scare anybody” (263). We know from Little Richard’s own comments to his biographer that this diagnosis is spot on.

Since Dylan opts out of commenting on the lyrics to “Long Tall Sally,” I’ll let Rip Lhamon fill in some gaps. In his book Deliberate Speed: The Origins of a Cultural Style in the American 1950s, Lhamon decodes several references. “Traditional black folk figures scamper through this song in scandalous antics. Uncle John is a stock figure in black lore from the ‘John cycle’ of tales about a slave who outwits the authorities” (95). And what about the title figure? “It’s Long Tall Sally, ‘built for speed,’ who ‘got everything that Uncle John need.’ But where did Sally come from? Nightmare to every Aunt Mary, Sally is the newly noticed, old, subtraditional freak. Not only long, tall, and speedy, she’s ‘bald-headed’” (95). Lhamon adds this drag reading of Sally:

In the transvestite shows of Little Richard’s apprenticeship, baldheadedness was preparation for one’s wigs. Clearly Sally is a freak, the same term the singer had applied to his own incarnation as Princess Lavonne. Long Tall Sally, in addition to her other meanings, is therefore a transvestite fantasy figure slipping and sliding through life’s niches. […] She bears variant and deviant fantasies. She is as new as rock ’n’ roll. She is as old as the oral tradition. (95)

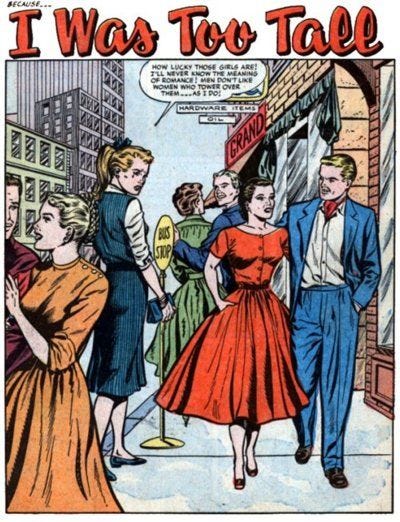

As for Dylan, he lets his accompanying picture do most of the interpretive work. Get a load of this striking vintage comic from the fifties on the facing page of the “Long Tall Sally” entry. Three couples pair off, wearing generic wardrobe from the era, walking down the street in white-bred bliss. A solitary woman towers over them all, gazing with envy and shedding a tear. Her thought bubble reads: “How lucky those girls are! I’ll never know the meaning of romance! Men don’t like women who tower over them…as I do!” (262).

It’s a blatant example of the rigidity of gender expectations and the cruel consequences of failing to conform to them. On one hand, this old-fashioned picture of a vanilla world seems hilariously out of place in contrast to the raunchy exuberance of “Long Tall Sally.” On the other hand, there’s more than one way to feel like a freak.

The more I think about it, this is a perfect illustration for the chapter, because it shows how someone from the fifties white middle class—the tall woman in the picture, or a Jewish kid from Hibbing, Minnesota—might identify with Little Richard as a misfit and outcast. Shortly after Little Richard’s death, Dylan offered this tribute to his chosen ancestor:

He was my shining star and guiding light back when I was only a little boy. His was the original spirit that moved me to do everything I would do. I played some shows with him in Europe in the early nineties and got to hang out in his dressing room a lot. […] In his presence he was always the same Little Richard that I first heard and was awed by growing up and I always was the same little boy. Of course, he’ll live forever. But it’s like a part of your life is gone. (Bob Dylan Facebook post, 9 May 2020)

Early rock music was liberating for listeners like Bobby Zimmerman who didn’t fit in to the society they were inheriting. Swishing, border-crossing performers like Little Richard offered an alternative by celebrating the rebellious, the freakish, and the queer, turning social stigmas into badges of honor, pride, and solidarity.

Elvis Presley

The first face you see on the cover of The Philosophy of Modern Song is Little Richard from 1957, when Bobby Zimmerman was a 16-year-old high school sophomore. Then you open the book, and the first figure you encounter is a full-length Elvis Presley, also from 1957. Elvis is in a record store staring at an album display, and if you look closely you can see albums by Elvis, Little Richard, and even James Dean. For Bobby Zimmerman in the fifties, the record store was a sacred space. The picture is a sort of analogue for Dylan’s book: both are repositories of song, archives of the preserved and curated past, warehouses of the mind, memory palaces.

More 1950s songs are included in The Philosophy of Modern Song than any other decade by far, and Elvis is the most frequently referenced musician in the book. If you want further confirmation of Elvis’s exalted importance to young Bobby Zimmerman, consider his testimonial in US Magazine commemorating the tenth anniversary of Presley’s death:

When I first heard Elvis’s voice I just knew that I wasn’t going to work for anybody; and nobody was going to be my boss. He is the deity supreme of rock & roll religion as it exists in today’s form. Hearing him for the first time was like busting out of jail. I think for a long time that freedom to me was Elvis singing “Blue Moon of Kentucky.” I thank God for Elvis. (1046)

It is difficult for those of us who didn’t live through the fifties to appreciate just what a radical effect Elvis had on young people back then—and what a threat he posed to the older gatekeepers of morality, conventional gender roles, and racial segregation. Whatever “Elvis the Pelvis” had going down below his wait was deemed so dangerous that the TV public had to be shielded from it, as when “The Ed Sullivan Show” famously decided to only frame Elvis from the waist up.

When he appeared for the first and last time on the Grand Ole Opry stage in 1954, the audience was more shocked by Elvis from the neck up, with his coifed hair and makeup. In her book Vested Interests: Cross-Dressing & Cultural Anxiety, Marjorie Garber offers this vivid description of Elvis’s subversive appeal:

Race, class, and gender: Elvis’s appearance violated or disrupted them all. His created “identity” as the boy who crossed over, who could take a song like “Hound Dog” from Big Mama Thornton or the onstage raving—and the pompadour, mascara, and pink and black clothing—from Little Richard, made of Elvis, in the popular imagination, a cultural mulatto, the oxymoronic “Hillbilly Cat,” a living category crisis. (367)

That’s pretty good: Elvis as “living category crisis.” Or, we could distill it down further, using Little Richard’s preferred term, and simply say that Elvis was a freak.

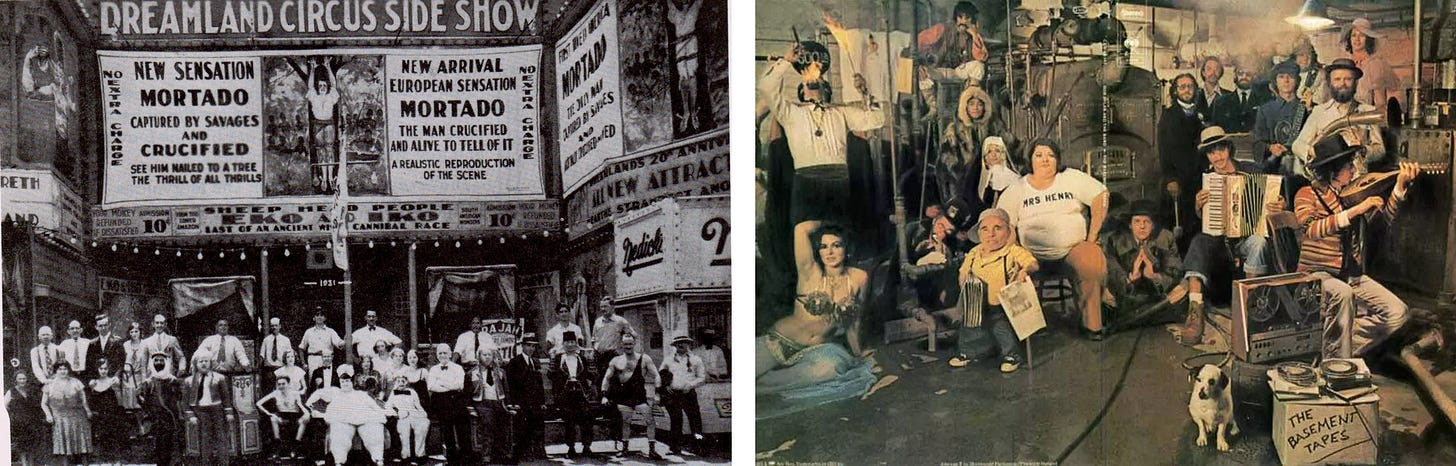

In his memoir Chronicles and the documentary No Direction Home, Dylan talks about the lasting impression traveling circuses made on him as a child, and he made several references to carnivals and freak shows in his mid-sixties rock trilogy. The best example is “Ballad of a Thin Man” on the album Highway 61 Revisited.

You hand in your ticket

And you go watch the geek

Who immediately walks up to you

When he hears you speak

And says, “How does it feel

To be such a freak?”

And you say, “Impossible!”

As he hands you a bone

Because something is happening here

But you don’t know what it is

Do you, Mister Jones?

The freaks in this song are the Long Tall Sally variety, as Dylan makes clear in this thinly veiled reference to a blowjob from a drag queen:

Well, the sword swallower, he comes up to you

And then he kneels

He crosses himself

And then he clicks his high heels

And without further notice

He asks you how it feels

And he says, “Here is your throat back

Thanks for the loan”

And you know something is happening here

But you don’t know what it is

Do you, Mister Jones?

The freaks control the world of this song, and for once it’s the button-down square who feels confused and out of place. Freak shows could be a place for egregious exploitation by unscrupulous profiteers, yes, but these spaces also functioned as playgrounds for taboo behavior. Freak shows were also sanctuaries and communities for the marginalized and demonized.

I stress this carnivalesque context because Dylan himself makes an extended circus analogy in his commentary on Elvis’s “Viva Las Vegas”:

Among a certain cadre of fans, Colonel Tom Parker is equally reviled for squandering Elvis’s talents in increasingly substandard movies and holding him in stasis in Las Vegas by allowing the Hilton a sweetheart deal to help offset the managers staggering gambling debt. Famously, Elvis’s health and performance spiraled downward but still, he was paraded out night after night. The spectacle began to resemble something out of P. T. Barnum, who would promote a star attraction well past their prime as a curiosity just to get people into the tent. In this case Elvis was that curiosity and the tent was Vegas, and if people were ultimately disappointed by the star’s dissolution there were plenty of other distractions to take their minds off it. And to take their money. All lessons the Colonel learned somewhere between the Netherlands of his birth and the carnivals where he was truly born. (309)

Parker as Barnum and Elvis as circus freak is one thing. But in depicting Elvis as a carnal commodity to be auctioned off to pay his boss’s debts, and by referencing the other distractions notoriously available in Vegas, as well as the Netherlands of Parker’s youth (think of the bordellos and burlesque shows in Amsterdam’s red-light district), Dylan is also implying that Parker was Elvis’s pimp.

Dylan relates personally to these various subversive forms of gender performance: the freak, the stripper, the prostitute. He had a greedy and manipulative Colonel Parker of his own, Albert Grossman, who drove him so hard in the mid-sixties that it nearly killed him. But Dylan’s sense of being in the burlesque business extends well beyond the Grossman years. In his 1997 Newsweek interview, he told David Gates: “I don’t think of myself in the high falutin’ area. I’m in the burlesque area” (1196).

That same year at a London press conference, he observed: “Performing’s all the same. When you’re up on stage, and you’re looking at a crowd and you see them looking back at you, you can’t help but feel like you’re in a burlesque show” (1201).

He was still singing this tune at the 2001 Rome press conference, but by then he was stressing not only exploitation but also the thrill of burlesque: “The stage is the only place where I’m happy. It’s the only place you can be what you want to be. When you’re up there and you look at the audience and they look back then you have the feeling of being in a burlesque. But there’s a certain part of you that becomes addicted to a live performance” (1259).

Cher

My favorite expression of Dylan’s identification with burlesque, and one of his most intriguing gender performances, appears in The Philosophy of Modern Song in his chapter about Cher’s “Gypsies, Tramps and Thieves.” In this song she assumes the role of a young woman born on the road. Her mother is a stripper, and her father is part revival tent preacher and part medicine show charlatan. The implication is that the father pimps out his wife on the side, and his daughter is eventually drafted into the family business. At the age of sixteen, she gets pregnant by an older man who soon abandons her. Like her mother before her, she becomes a sex worker to support her young daughter, repeating the generational cycle. As they roam from place to place, these carnies are denounced by the townsfolk as “gypsies, tramps and thieves”; but come nightfall, the local men slink into the tent to indulge forbidden desires

.

“This song takes place on the dividing line between the old culture and the new,” writes Dylan (235). It takes place on the old dividing line of binary genders, too, and Dylan crosses over. He imagines his way into the experience of this young burlesque performer. He dances in her heels and sees through her eye shadow. Using the pronoun “you,” located in the shadowland between I and they, Dylan conjures the scene under the tent: “Strip yourself bare and dance the sword dance, buck naked inside of a canvas tent, fenced in, where the town royalty, the top brass and leading citizens, bald as eggs throw their money down, sometimes their entire bankroll” (232). This is Dylan in drag, channeling his inner Cher and passing as Princess Lavonne. This is Dylan as stone-cold diva and charcoal maiden strutting his feathers well.

Dylan identifies closely with this burlesque dancer, seeing his own reflection when he looks into her mirror. Describing her relationship with the audience, he observes, “you know how to make them see wonderful things, and you can make music that drives them mad. You’ve got the character of Saturn and the spirit of Venus. Passion and desire, you give it to them under the counter” (232).

Dylan shares the dancer’s wanderlust, waking up every day with a chance to reinvent yourself on stage every night. She is his twin sister: “Your philosophy of life is wait and see. You make anybody who sets their eyes on you feel like they’re falling in love, you’ve got a long lineage—and you go everywhere at all times. This-a-way, that-a-way, over the hill, around the mountain, up the road and down the road, can you go past the cutoff point—sure, go where you like” (233).

Dylan can relate to being a commodified sex object who is sold to line the pockets of greedy profiteers and bought to feed the audience’s desires. But he also relates to the paradoxical freedoms and pleasures afforded by life on the road, unencumbered by the drudgery that chain normies like us to our mundane lives. Her home and her identity are unfixed: she performs herself into existence over and over again.

I’ll close with an interesting comment from Dylan in a 1986 radio interview in Australia. Reflecting upon his most formative decade, he recalled,

The ’50s were rough. Everybody romanticizes the ’50s but that was a very rough time. […] The only thing I remember that kept everybody going that I know in the ’50s was maybe a few films that Marlon Brando made, or James Dean, or the rockabilly music, and rhythm and blues, and that was it. That music, it called out to you, and very few people were onto it. And it was almost like a life raft thrown to people who were different back then. (EON-FM 936)

Bobby Zimmerman never made it out of Minnesota, but Bob Dylan did. He climbed aboard that life raft and fled the restrictive values that defined and confined him in 1950s America. He sailed that life raft to New York and performed new selves into existence in the decades that followed. In The Philosophy of Modern Song, Dylan reconstructs the escape route on his journey to freedom and self-expression. He celebrates the artists, revolutionaries, and chosen ancestors who taught him a new philosophy, showing him a different way to live and create and survive.

Works Cited

Bordo, Susan. The Male Body: A New Look at Men in Public and in Private. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1999.

Colavito, Jason. “No, James Dean Was Not Marlon Brando’s Sex Slave.” Culture & Curiosities (14 April 2023),

.

Dylan, Bob. “Ballad of a Thin Man.” Highway 61 Revisited. Columbia Records, 1965.

---. London Press Conference, Metropolitan Hotel (4 October 1997). Every Mind Polluting Word: Assorted Bob Dylan Utterances, ed. Artur Jarosinski (Don’t Ya Tell Henry, 2006), 1197-1213.

---. The Philosophy of Modern Song. Simon & Schuster, 2022.

---. Post on the death of Little Richard. Bob Dylan’s Facebook Page (9 May 2020), https://www.facebook.com/bobdylan/posts/i-just-heard-the-news-about-little-richard-and-im-so-grieved-he-was-my-shining-s/10163359789960696/.

---. Rome Press Conference, De la Ville Inter-Continental Roma Hotel (23 July 2002). Every Mind Polluting Word: Assorted Bob Dylan Utterances, ed. Artur Jarosinski (Don’t Ya Tell Henry, 2006), 1259-63.

Ellison, Ralph. “The World and the Jug.” Shadow and Act, 1964, 107-43.

EON-FM Radio Interview with Bob Dylan. Melbourne, Australia (21 February 1986). Every Mind Polluting Word: Assorted Bob Dylan Utterances, edited by Artur Jarosinski, Don’t Ya Tell Henry, 2006, 936-37.

Garber, Marjorie. Vested Interests: Cross-Dressing & Cultural Anxiety. Routledge, 1992.

Gates, David. “Dylan Revisited.” Newsweek (5 October 1997), https://www.newsweek.com/dylan-revisited-174056.

Lhamon, Jr., W. T. Deliberate Speed: The Origins of a Cultural Style in the American 1950s. Smithsonian Institution, 1990.

McCann, Graham. Rebel Males: Clift, Brando and Dean. Rutgers University Press, 1993.

McLean, Don. “American Pie.” American Pie. United Artists, 1971.

Ross, Marlon B. Sissy Insurgencies: A Racial Anatomy of Unfit Manliness. Duke University Press, 2022.

US Magazine Feature on Tenth Anniversary of the Death of Elvis Presley. Every Mind Polluting Word: Assorted Bob Dylan Utterances, edited by Artur Jarosinski, Don’t Ya Tell Henry, 2006, 1046.

White, Charles. The Life and Times of Little Richard: The Quasar of Rock, updated edition. Da Capo, 1994.

Did you ever see this, Graley??

https://open.substack.com/pub/johnnogowski/p/review-dylan-looks-at-all-sorts-of?r=7pf7u&utm_medium=ios

Thanks for this great writing. I was in Odense too and I lived through the fifties and I do think you appreciate good !

All the best.