Dylan's Shadows

Part 1

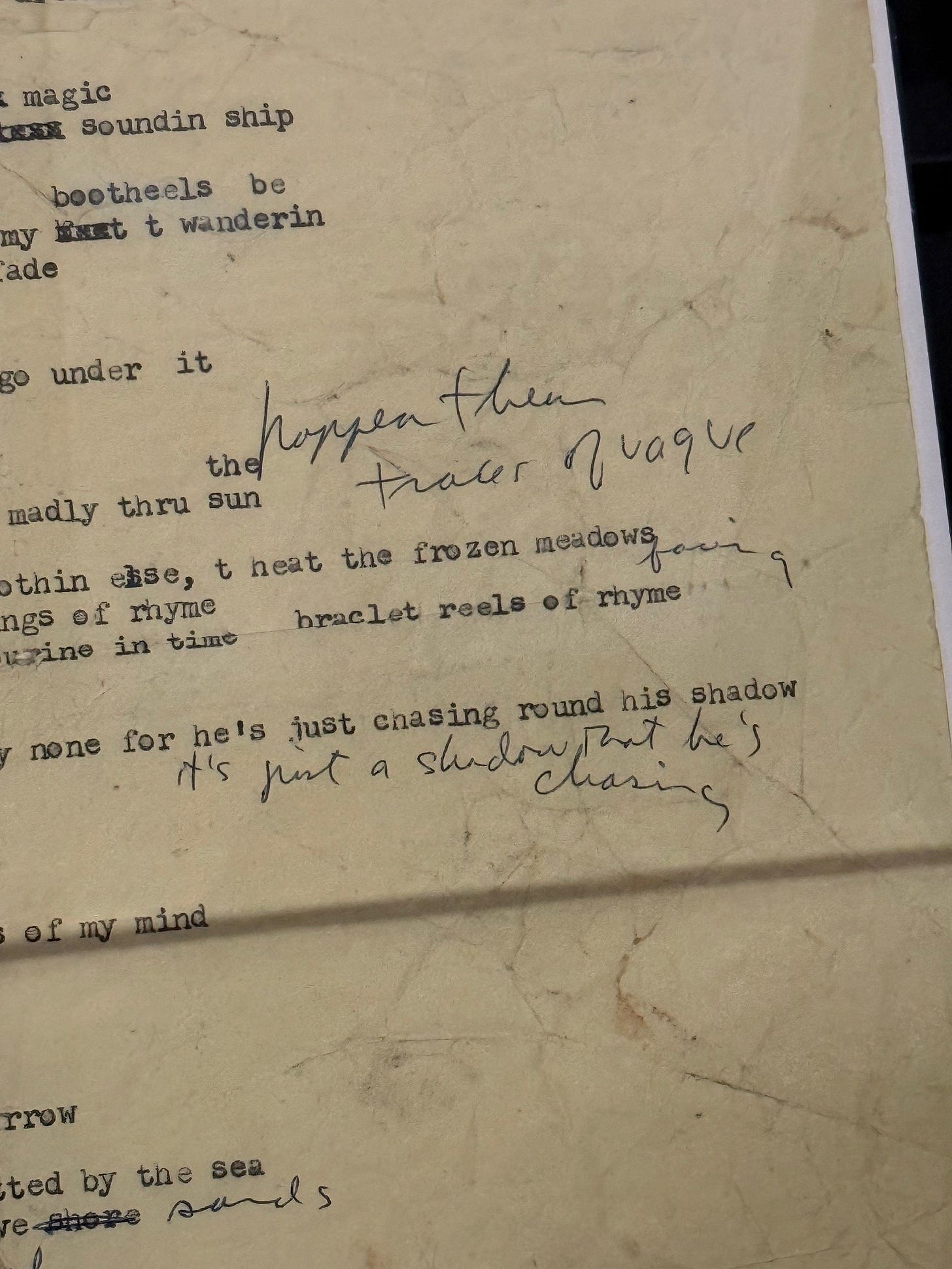

The night before the World of Bob Dylan 2025 Conference began, the Dylan Center hosted a sneak peek of its “Going Electric” exhibit. Laura Tenschert attended the event and excitedly texted me a picture from one of the display cases:

This is from the original typescript for “Mr. Tambourine Man.” Laura knew I would love it because it shows Dylan working on the line echoed in the title of my Substack site. He initially typed, “It’s just a ragged clown behind / an if his eyes look blind dont worry none for he’s just chasing round his shadow.” He later scribbled in the phrase “it’s just a shadow that he’s chasing.” It’s cool to find Dylan chasing after the image while composing the song, tracking down just the right way to phrase it.

I don’t recall spending much time on choosing my title. I wanted a space outside of traditional academic publishing for developing my ideas about Dylan’s art, getting them out quickly, and receiving immediate feedback whenever I struck a chord with interested readers. The figure of a clown chasing shadows felt right immediately. A blind fool in stumbling pursuit, always a step behind and sometimes utterly lost, groping for shadows and trying to trace their outline before the musician darted off in another direction—ah yes, there it is. Shadow Chasing.

Laura planted a seed with that innocent little text. Come to think of it, there are a lot of interesting shadows in Dylan’s work, particularly in the past decade. There is his first album of American standards, Shadows in the Night (2015). Then there is the 2021 film Shadow Kingdom, later released as an album in 2023. I even came across this 2024 Dylan painting at the Halcyon Gallery called Shadow Mountain:

Although Dylan has become acutely besotted with shadows in recent years, you can find them lurking throughout his body of work. As I began researching this subject further, I found 40 original songs by Dylan that contain the word “shadow” or “shadows,” and that’s not even counting folk songs or live covers or synonyms like “shade.” Shadows appear in Dylan lyrics from every decade of his career, including some of his most enduring songs. There’s also a remarkable variety in the range of Dylan’s shadows over the years.

I know there’s something happening here, and I want to know what it is. This piece is the first in an anticipated three-part series. The first two installments will offer a taxonomy of Dylan’s shadows, subdividing his various uses of the trope into thematic classifications. The final piece will be a select case study, putting Dylan’s shadow art into conversation with that of another likeminded artist. In keeping with the topic, I’ll keep that other artist’s identity hidden in the shadows for now.

Hidden in the Shadows

Let’s begin with the basics. Shadows are areas of darkness shielded from the light. That’s just simple optics, without any moral implications or value judgment. But humans are meaning-making creatures, and over the millennia we’ve attached deep significance to light and darkness and the interplay between them. As a songwriter, Dylan has been endlessly curious about light/dark imagery, and he has sucked the milk out of a thousand shadows.

Darkness is a hiding place. People who are lost, vulnerable, ostracized, and forgotten live in the shadows. Dylan uses this sense of the term most famously in “Chimes of Freedom”:

Far between sundown’s finish and midnight’s broken toll

We ducked inside the doorways, thunder crashing

As majestic bells of bolts struck shadows in the sounds

Seemin’ to be the chimes of freedom flashing

Throughout this anthem, the singer expresses solidarity with outlaws and outcasts relegated to the darkness. Many of these shadow dwellers are overlooked by society, while others are fleeing from the searching eyes and grasping hands of the law.

Dylan recognizes that the shadows can provide sanctuary for misfits and fugitives, but it can also provide cover for those chasing after them. For instance, consider this enigmatic example from “Gates of Eden”:

The lamppost stands with folded arms

Its iron claws attached

To curbs ’neath holes where babies wail

Though it shadows metal badge

All and all can only fall

With a crashing but meaningless blow

No sound ever comes from the Gates of Eden

In this verse the singer describes an urban hellscape, the fallen world east of Eden, where suffering families huddle in tenements, and police officers wait outside in the dark, polishing their badges and biding their time before they swarm.

In these examples, Dylan’s sympathies unmistakably lie with the pursued in their flight from the pursuer. As a place, the shadows represent a haven; but those who seek refuge there are also referred to sometimes as shadows. Other examples spring to mind. Think of Simon & Garfunkel’s “Bleeker Street”: “I saw a shadow touch a shadow’s hand / On Bleeker Street.” Or Bruce Springsteen’s “Jungleland”: “And the kids ’round here look just like shadows / Always quiet, holding hands.” Compare those musical shadows with Dylan’s great Oh Mercy outtake “Dignity”:

Wise man looking in a blade of glass

Young man looking in the shadows that pass

Poor man looking through painted glass

For dignity

One of my favorite presentations at the 2025 Tulsa conference was delivered on the final day by Timo Zwarg. He approaches Dylan from a distinct perspective as a graduate student in Kennesaw State University’s School of Conflict Management, Peacebuilding and Development. After the conference, he kindly sent me a copy of his paper on “Minimal Gestures: Dignity as a Peacebuilding Imperative in Bob Dylan’s Oh Mercy.” He argues that “a central, unifying theme of the album is the systematic absence of human dignity and the quiet, often fragile, responses that arise in its wake” (1). According to Zwarg, Dylan’s intervention takes the form of “minimal gestures: foundational acts of witnessing, remembrance, and acknowledgment. Ultimately, this reading suggests that Oh Mercy offers a sustained meditation on how, when larger systems fail, the essential work of holding ground begins with the simple, understated, yet imperative act of human recognition” (2-3). It’s a compelling and profound thesis.

This central theme is epitomized by the song “Dignity”—which, in Dylan’s signature move from the eighties, he perversely left off the album. I drew your attention to the image of the shadow, but now take a second look and pay attention to the verbs:

Wise man looking in a blade of glass

Young man looking in the shadows that pass

Poor man looking through painted glass

For dignity

On one hand, the emphasis on “looking” is portrayed as a futile act since the detective-singer never succeeds in finding the dignity he seeks. On the other hand, the minimal gesture of looking—of recognition and being seen—proves fundamentally important.

As Zwarg observes, “Within this bleak context, a typology of ‘minimal gestures’ emerges as the core of the album’s restorative potential: foundational acts of recognition” (36). He cites bell hooks on “love as political resistance” and applies it to Dylan’s approach to dignity violations. In the outtake “Dignity,” and in several other songs from Oh Mercy, Dylan models “the practice of recognizing and affirming human worth precisely where domination seeks to render people invisible or disposable. By documenting pervasive violations while simultaneously centering these small acts, Dylan suggests that when breakdown feels complete, the way forward begins with the irreducible act of one human being recognizing another” (38-39). Violations of dignity reduce people to shadows. But the minimal gesture of recognizing the shadow as such, and validating that person’s experience, marks a crucial step toward restoring lost dignity.

The Shadow of Death

If we survey the entirety of Dylan’s work from high atop Shadow Mountain, we see that he most frequently uses shadows to evoke death or doom. The earliest example I could find from a Dylan original is “Whatcha Gonna Do?,” a 1962 outtake from the Freewheelin’ sessions. The song opens:

Tell me what you’re gonna do

When the shadow comes under your door

Tell me what you’re gonna do

When the shadow comes under your door

Tell me what you’re gonna do

When the shadow comes under your door

O Lord, O Lord

What shall you do?

From the start of his career, young Dylan was a self-styled Old Testament prophet warning of a day of moral reckoning near at hand.

He also uses shadows to conjure the specter of unjust institutionalized violence, particularly capital punishment. For instance, in “Seven Curses,” a 1963 outtake from The Times They Are A-Changin’, a daughter sleeps with a corrupt magistrate in exchange for her father’s pardon. However, as the lecherous judge is enjoying his conquest, he reneges on the deal and orders the father’s hanging:

The gallows shadows shook the evening

In the night a hound dog bayed

In the night the grounds was groanin’

In the night the price was paid

The next mornin’ she had awoken

To find that the judge had never spoken

She saw the hangin’ branch a-bendin’

She saw her father’s body broken

Dylan’s phrasing is interesting. The shadow is invested with supernatural power, a force of evil capable of making the evening shake, the dogs bark, and the grounds groan. The shadow emanates from the gallows; but the evil emanates from the death-dealing judge who controls the gallows, his icy grip manipulating the levers of justice.

Dylan opens “It’s Alright, Ma (I’m Only Bleeding)” with one of his most vivid uses of the trope:

Darkness at the break of noon

Shadows even the silver spoon

The handmade blade, the child’s balloon

Eclipses both the sun and moon

To understand you know too soon

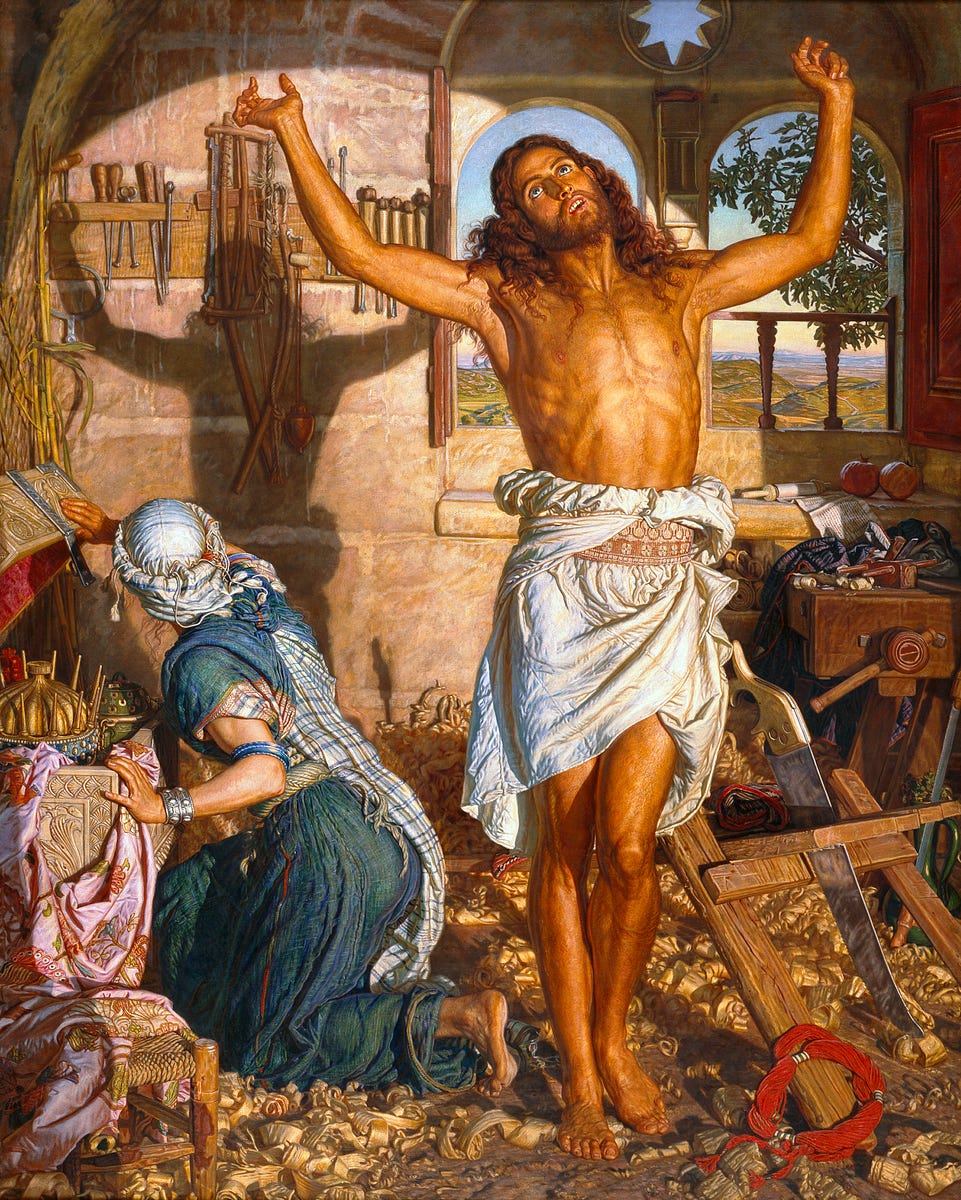

There is no sense in trying

The eclipse that causes this shadow is taken from the crucifixion. According to the gospels, Jesus was regarded by Roman imperial officers as a threat to the state. They arrested him as a criminal, tortured him and condemned him to death, and publicly executed him on the cross as a warning against other rebels. According to Luke, as Jesus hung dying in the noonday sun, the sky suddenly went dark:

It was now about noon, and darkness came over the whole land until three in the afternoon, for the sun stopped shining. And the curtain of the temple was torn in two. Jesus called out with a loud voice, “Father, into your hands I commit my spirit.” When he said this, he breathed his last. (Luke 23:44-46 NIV)

Dylan is highly critical of his own society in “It’s Alright, Ma,” skewering American consumerism, phony propaganda, political corruption, and moralizing piety. In the final verse, the singer wonders if he, too, might eventually be branded an enemy of the state and targeted for elimination: “If my thought-dreams could be seen / They’d probably put my head in a guillotine” The law and the gallows are always shadowing Dylan’s renegades and holy outlaws.

I hear echoes again of the crucifixion, as well as self-echoes of “It’s Alright, Ma,” in Dylan’s brooding masterpiece “Not Dark Yet.” Death hangs over the condemned singer from the very first word:

Shadows are fallin’ and I’ve been here all day

It’s too hot to sleep and time is runnin’ away

Feel like my soul has turned into steel

I still got the scars that the sun didn’t heal

There’s not even room enough to be anywhere

It’s not dark yet but it’s gettin’ there

In this context, it’s worth noting that “Not Dark Yet” was included on the soundtrack Songs Inspired by The Passion of the Christ. Since Time Out of Mind was released seven years before Mel Gibson’s The Passion of The Christ, there’s no way that the song was directly influenced by the film. However, Dylan’s decision to contribute this song to the soundtrack invites a connection to the crucifixion. It’s tantalizing to interpret “Not Dark Yet” as, in part, Dylan’s effort to shadow Jesus and identify with his plight during the final painful hours of his mortal life.

Time and again, Dylan’s invocation of shadows contains religious resonances. There’s no mistaking the Christian allusion in “When the Deal Goes Down”:

The midnight rain follows the train

We all wear the same thorny crown

Soul to soul our shadows roll

And I’ll be with you when the deal goes down

However, Sometimes the connotations are more sinister, as in “Unbelievable”: “You must be living in the shadow of some kind of evil star / It’s unbelievable it would get this far.”

The tone gets downright apocalyptic in “Rollin’ and Tumblin’”: “The night’s filled with shadows, the years are filled with early doom / I’ve been conjuring up all these long dead souls from their crumblin’ tombs.”

One thing that remains consistent is that, when the shadow of death comes for you, there is no avoiding or denying your fate. Dylan spells that out most clearly in “Tempest”:

The night was black with starlight

The seas were sharp and clear

Moving through the shadows

The promised hour was near

That said, Dylan’s characters do not always approach death with dread. The shadow of death is palpable throughout Rough and Rowdy Ways, but in “Key West (Philosopher Pirate),” the singer walks through the darkness toward the light with acceptance and grace:

Well the Fishtail Palms and the orchid trees

They can give you the bleeding heart disease

People tell me I ought to try a little tenderness

On Amelia Street, Bayview Park

Walking in the shadows after dark

Down under, way down in Key West

In this beatific hymn, Dylan comes closest to achieving the faith and peace of mind eloquently expressed by the psalmist David: “Yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil; for thou art with me; thy rod and thy staff they comfort me” (Psalm 23:4 KJV). With the Lord as his shepherd, the singer in Key West seems bound for glory: “Surely goodness and mercy shall follow me all the days of my life: and I will dwell in the house of the Lord forever” (Psalm 23:6 KJV).

Sexy Shadows

Dylan’s shadows aren’t always spiritual—some are practically panting with carnal desire. Several songs trace silhouettes of lovers, foreshadowing sex rather than death. A nice bridge between these two species of shadows can be found in “Golden Loom,” an outtake from Desire:

First we wash our feet near the immortal shrine

And then our shadows meet and then we drink the wine

I see the hungry clouds up above your face

And then the tears roll down, what a bitter taste

And then you drift away on a summer’s day where the wildflowers bloom

With your golden loom

Those converging shadows never sounded sexier than in Maria Muldaur’s sultry cover:

For the most overtly sexual shadow in Dylan’s stable, saddle up for a ride on “New Pony.” The pony is named Lucifer, which I suppose implies a religious interpretation. That might work on the page. But I defy you to actually listen to the song and come away with any impression other than throbbing, sweating sexuality.

Well now it was early in the mornin’, I seen your shadow in the door

It was early in the mornin’, I seen your shadow in the door

Now I don’t have to ask nobody

I know what you come here for

That ain’t no Bible salesman scratchin’ at the door, and it ain’t no Grim Reaper, either. We know a booty call when we hear one. Unfortunately, you won’t hear it on Street-Legal, where Dylan omits this verse. But you can hear him sing it at this Paris soundcheck in 1978:

Dylan continued to pursue shadows of seduction into the eighties. On “Emotionally Yours” from Empire Burlesque, he sings,

Come baby, rock me, come baby lock me into the shadows of your heart

Come baby, teach me, come baby, reach me, let the music start

I could be dreamin’ but I keep believing you’re the one I’m livin’ for

And I will always be emotionally yours

It’s also worth pointing out that Dylan was drawn to shadows in the songs of other artists he admired. In a 2009 interview, Bill Flanagan asked him about the songwriters he admired most. When asked his favorite Gordon Lightfoot songs, the first he named was “Shadows”:

Let it go

Let it happen like it happened once before

It’s a wicked wind and it chills me to the bone

And if you do not believe me

Come and gaze upon the shadow at your door

In 2012, Dylan played a lovely cover of “Shadows” at his concert in Edmonton. When Flanagan asked about John Prine, Dylan said his favorite song was “Lake Marie.” You may recall the memorable crime scene from that song:

In the parking lot by the forest preserve

The police had found two bodies

Nay, naked bodies

Their faces had been horribly disfigured by some sharp object

Saw it on the news

On the TV news

In a black and white video

You know what blood looks like in a black and white video?

Shadows

Shadows!

Prine’s lyrical strategy, intercutting news footage of a double homicide with the death of a marriage, reminds us that sex and death are not necessarily mutually exclusive topics. We’ll see that dynamic on stark display in Part 2 of this series. But before Dylan began writing about shadow stalkers, he explored the theme of rival shadows.

Rival Shadows

An early example of rival shadows appears in the “Billy” songs from the Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid soundtrack. In “Billy 4” he cautions,

Laying around with some sweet señorita

Into her dark chamber she will greet ya

In the shadows of the mesa she will lead ya

Billy and you’re going all alone

Stretching out on some sweet señorita’s big brass bed sounds sexy enough. But when the tryst is followed by a trip to a shadowy mesa, it sounds like Billy’s lover is leading him into an ambush and a date with death.

Sex is rarely simple in Dylan’s songs. He has a playwright’s instincts for dramatic conflict. Hooking up with a new lover often involves stealing her from someone else, or looking over your shoulder for a rival lover sneaking up from behind. There’s an excellent example of this dynamic in one of Dylan’s greatest songs, “Caribbean Wind.” I’ve never heard a bad version of the song, and Dylan apparently never heard a good version—at least not one good enough to release on a studio album. The first and only live performance came at San Francisco’s Warfield Theatre on November 12, 1980 (mislabeled 1979 on Trouble No More). “Caribbean Wind” features one of the best love triangles in all of Dylan:

Shadows grew closer as we touched on the floor

Prodigal son sitting next to the door

Preaching resistance, waitin’ for the night to arrive

He was well connected but his heart was a snare

And she had left him to die in there

But I knew he could get out while he still was alive

Dylan describes the lovers’ shadows drawing closer to signal that the couple is having sex on the floor. But the shadow of the singer’s rival also hovers over the scene. This “prodigal son” sounds like a revolutionary who was betrayed and abandoned by his lover, left to rot in a jail cell. But as long as the woman’s ex remains alive, he poses a threat to return and reclaim his lost love. The sun is sinking low (thus the shadows on the floor), but when the night comes falling from the sky, the rival shadow is poised to pounce.

Sometimes a third party isn’t necessary to sabotage a relationship. Another fascinating use of shadows, where lovers come across more like rivals, can be found in “New Danville Girl,” an outtake co-written with Sam Shepard and recorded during the Empire Burlesque sessions. “New Danville Girl” departs so radically from “Brownsville Girl” that it is essentially a different song. In one variant lyric, Dylan sings,

You know it’s funny how people just want to believe what’s convenient

Nothing happens on purpose, it’s an accident if it happens at all

And everything that’s happenin’ to us seems like it’s happenin’ without our consent

But we’re busy talking back and forth to our shadows on an old stone wall

Oh you got to talk to me now baby, tell me about the man that you used to love

And tell me about your dreams just before the time you passed out

Tell me about the time that our engine broke down and it was the worst of times

Tell me about all the things I couldn’t do nothin’ about

I quote this passage at length because a) it’s amazing, and b) it provides relevant context for understanding the shadow imagery. This couple doesn’t really communicate anymore: they talk to each other’s shadows. They recite lines of dialogue as if they’ve memorized a script. Essentially, they are no different than actors in a movie scene, which is why the film references works so effectively in this song. It’s all an elaborate form of self-imitation, of shadow theater, as the singer spells out in the final verse when he projects himself into the film:

There was a movie I seen one time and I think I sat through it twice

I don’t remember who I was or what part I played

All I remember about it was that it was starring Gregory Peck

But that was a long time ago

And it was made in the shade

Perfect! Made in the shade (darkness), made out of shades (mirror images), and made for shades (ghosts), in this case the ghosts of a dead love.

The ghosts of dead love continue to haunt Dylan’s late shadow songs. We find another one throwing shade in “This Dream of You” from Together Through Life:

I look away but I keep seeing it

I don’t want to believe but I keep believing it

Shadows dance upon the wall

Shadows that seem to know it all

Those shadows could come from a rival creeping into his lover’s room when he’s not around, or they could be paranoid figments of his imagination. Ultimately the result is the same. The singer is jealous and suspicious that his love cannot be trusted, that it has all been a dream.

My favorite treatment of this morose mindset on Together Through Life comes in the song “Forgetful Heart.” Dylan must be fond of this one, too, since he has recently revived it for his Outlaw Music Festival setlists. Check out this brazen video shot at the Cincinnati concert on June 22, 2025. There is a brief video glitch near the end, and, wouldn’t you know it, the line that gets dropped is the one about the shadow. Maybe the shadow was covering his tracks. The perspective is so intrusively close that you could just about convince yourself that we’re witnessing Dylan being stalked by his own shadow:

Here’s the full final verse:

Forgetful heart

Like a walking shadow in my brain

All night long

I lay awake and listen to the sound of pain

The door has closed forevermore

If indeed there ever was a door

If you’re a Shakespeare fan, you can’t miss the echo of Macbeth’s morbid soliloquy:

Out, out, brief candle!

Life’s but a walking shadow; a poor player

That struts and frets his hour upon the stage,

And then is heard no more: it is a tale

Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury

Signifying nothing. (5.5.23-28)

Note that the stage where the shadow struts and frets in “Forgetful Heart” is the singer’s brain. His perceived rival has moved from a silhouette on the wall to a shade inside his skull. There’s no cure for that, and no escape. He recognizes as much in the final line: there is no exit door from his self-imposed prison of shadows.

I’ve touched upon 20 different Dylan songs in Part 1, and I still haven’t gotten to many of the best examples. In Part 2 I’ll keep compiling this taxonomy of Dylan’s shadows with sections on stalker shadows, shadow selves, shadow art, and my favorite Dylan shadow of them all (I bet you’ve already guessed it). Then hang around for Part 3, where I’ll reveal the identity of Dylan’s secret sharer and we can watch them chase each other’s shadows.

Works Cited

Dylan, Bob. Official Lyrics. The Official Bob Dylan Website.

https://www.bobdylan.com/.

Flanagan, Bill. Interview with Bob Dylan (2009). Notes from various mornings and nights (8 February 2024),

.

The Holy Bible. King James Version.

The Holy Bible. New International Version.

Shakespeare, William. Macbeth. Arden Shakespeare, 10th edition. Ed. Kenneth Muir. Methuen, 1971.

Zwarg, Timo A. “Minimal Gestures: Dignity as a Peacebuilding Imperative in Bob Dylan’s Oh Mercy.” Conference Paper. World of Bob Dylan Conference. Tulsa, 2025.

Personally I can’t imagine starting a Dylan newsletter with an under-thought and esoteric title that no one understands.

(Wait, who are we talking about again!)

Love it. And this. https://open.substack.com/pub/johnnogowski/p/on-time-the-basement-tapes-and-us?r=7pf7u&utm_medium=ios