Dylan's Shadows

Part 2

From his first band The Shadow Blasters to his recent film/album Shadow Kingdom and beyond, Bob Dylan has remained persistently fascinated with shadows. In Part 1 of this series, we explored 20 Dylan songs that reference shadows, ranging from songs about characters hidden in the shadows to shadows of death, from sexy shadows to rival shadows. The mood got gloomy in that final section, as we encountered suspicious, jealous, paranoid singers who believed that their love was under threat by some shadowy nemesis. Now let’s penetrate even deeper into the darkness and follow the footsteps of Dylan’s stalker shadows.

Shadow Stalkers

An important link between Dylan’s rival shadows and the more dangerous subspecies of stalker shadows appears in the Oh Mercy song “What Was It You Wanted?” On one level, the singer seems to be questioning his lover to find out if she’s been cheating on him:

Was there somebody looking

When you gave me that kiss?

Someone there in the shadows

Someone that I might have missed?

It sounds like the singer’s understudy might be warming up in the wings, ready to supplant him as the current leading man. We’ve heard plenty of these worried men with worried minds in Dylan songs before. But “What Was It You Wanted?” works on other intriguing levels.

At times, the singer seems to be the one under investigation:

What was it you wanted?

I ain’t keepin’ score

Are you the same person

That was here before?

Is it something important?

Maybe not

What was it you wanted?

Tell me again I forgot

The singer sounds trapped under a spotlight, forced to account for his actions and shortcomings by some shadowy interrogator. This is the stuff of crime drama and film noir. Or it could be a doomsday reckoning for the singer’s soul, accounting for his past sins to determine where he’ll spend eternity. Either way, “What Was It You Wanted?” fits perfectly with the noir ambience of a “Roadhouse on the River Styx” (to quote Sean Latham) in Shadow Kingdom.

It’s pretty clear from Dylan’s comments in Chronicles that he had demanding critics and fans in mind for “What Was It You Wanted?”: “If you’ve ever been the object of curiosity, then you know what this song is about. It doesn’t need much explanation” (172). This song confronts the scavengers who feed off Dylan’s celebrity and pointedly asks them “What Was It You Wanted?” As he reflects in Chronicles, “They can obstruct you in a lot of ways. It’s pointless trying to resist them or deal with them by force. Sometimes you just have to bite your upper lip and put sunglasses on” (172).

Dylan isn’t embodying the shadow stalker in “What Was It You Wanted?” Rather, he is telling us what it feels like to be an object of obsession, feeding the insatiable appetites of the dark eyes and devouring shadows that have engulfed him for decades.

He might also have had his dark-eyed producer in mind. Dylan details his many clashes with producer Daniel Lanois during the recording sessions for Oh Mercy. The recurring question in “What Was It You Wanted?” could be in part directed toward the demanding maestro who kept prodding and pushing Dylan in creative directions he resisted. Tellingly, when he recounts his first meeting with Lanois, he describes his nemesis like a shadow stalker: “He was noir all the way—dark sombrero, black britches, high boots, slip-on gloves—all shadow and silhouette—dimmed out, a black prince from the black hills” (177). The more Dylan grappled with Lanois, the more his shadow imagery proliferated.

“Art is a disagreement,” as a wise philosopher once put it (POMS 35). We can argue about a lot of things in Dylan’s art, but there’s no debate about which of his records is the darkest: Time Out of Mind. There are more shadows lurking in this album than any other. Dylan contributes to the murder ballad tradition with several songs about creepy stalkers. Keep your eyes and ears fixed on the shadows: they work as effectively as a GPS tracker for following these predators down the moonlit pathways of pathos.

Dylan establishes the theme from the beginning with the opening song “Love Sick”:

I see lovers in the meadow

I see silhouettes in the window

I watch them ’til they’re gone

And they leave me hanging on

To a shadow

This is how it starts. Unrequited love leads to resentment, which leads to bitterness toward the jilted lover, which extends to anger toward others who enjoy the love deprived from the singer, which instills a hunger for revenge—and the hunt is on. “This kind of love . . . I’m so sick of it.”

This lovesick disease is apparently spread by shadows, for everywhere you find them, you will also see signs of the infection spreading. Even the beloved outtake “Mississippi” is not immune. In alternate take #3 from the TOOM sessions, the singer laments,

I’m standing in the shadows with an aching heart

I’m looking at the world tear itself apart

Minutes turned to hours, hours turned to days

I’m still loving you in a million ways

These shadow dwellers cling to love as if it is the cure for what ails them. However, this mutant strain of love proves to be the cause of their illness. We find the singer trying to fight off the disease in the album’s second song, “Dirt Road Blues”: “I’ve been looking at my shadow, I been watching the colors above / Looking at my shadow, watching the colors up above / Rolling through the rain and hail, looking for the sunny side of love.” Unfortunately, he’s not headed toward the sunny side of love: he’s plunging further into darkness.

Viewed from this vantage point, even the seemingly sweet “Make You Feel My Love” turns sour and toxic:

When the evening shadows and the stars appear

And there is no one there to dry your tears

I could hold you for a million years

To make you feel my love

In the demo version above, as well as the track that made it onto the album, Dylan sings “shatters” rather than “shadows”; but the official lyrics read “shadows” and that’s what he has consistently sung in concert ever since. By now, we know a shadow stalker when we hear one. It’s dark, they are alone, he has her in his grasp, and he will never let her go. Cause of death: love sickness. Source of infection: shadows.

Murder ballads typically involve both crime and punishment. In the aftermath of TOOM’s crime of passion, the singer remains tortured by his lost love. The fever still hasn’t broken. In the first installment of this series, I considered “Not Dark Yet” in the Christian context of the crucifixion. However, in the present context, it could just as well depict a condemned killer on death row, awaiting execution in solitary confinement. Well, solitary unless you count the shades that haunt him:

Shadows are fallin’ and I’ve been here all day

It’s too hot to sleep and time is runnin’ away

Feel like my soul has turned into steel

I still got the scars that the sun didn’t heal

There’s not even room enough to be anywhere

It’s not dark yet but it’s gettin’ there

Like any great work of art, “Not Dark Yet” is large enough to contain multitudes. It’s not a matter of choosing the correct interpretation: is it a song about Jesus, or a song about a killer? The song is expansive and complex enough to encompass multiple levels of meaning, even contradictory ones.

Out of all the stalker shadows from the TOOM sessions, the one I find most interesting is “Dreamin’ of You.” On one hand, this is another song about an obsessive singer chasing after the shadow of his lost lover:

Travel under any star

You’ll see me wherever you are

The shadowy past is awake and so vast

I’m sleeping in the palace of pain

I’ve been dreamin’ of you

That’s all I do

But it’s drivin’ me insane

It’s such a perfect expression of the love sickness theme—maybe too perfect—so of course Dylan suppressed it and left it off the album. When the song was eventually released on the phenomenal Tell Tale Signs (Bootleg Series Vol. 8), it was accompanied by this fascinating video starring Dylan’s pal Harry Dean Stanton.

Dylan returns to the stalker shadow motif established in “What Was It You Wanted?” and amplifies the creepiness. In the song “Dreamin’ of You,” Dylan assumes the perspective of the stalker. But in the video, Dylan shifts from predator to prey, shadowed from town to town by an obsessive fan. Anderson’s character is ostensibly a bootlegger, following Dylan on the road to surreptitiously record his concerts. However, there is something unmistakably menacing about the way he tracks his quarry. We sense this threat every time he glances down at the black & white picture of a woman, presumably his lost love. It invites troubling questions: What did he do to her? What is he capable of doing next to his latest obsession? Harry Dean Stanton comes across like a copycat of Mark David Chapman. This is what a Bob Dylan stan looks like.

The dark shadows from Time Out of Mind metastasized into “Moonlight” on Dylan’s next album “Love and Theft.” Musically, the song sounds like a moon/June/spoon torch ballad, but lyrically the singer’s fangs drip with blood:

Well I’m preaching peace and harmony

The blessings of tranquility

Yet I know when the time is right to strike

I take you ’cross the river dear

You’ve no need to linger here

I know the kinds of things you like

The clouds are turnin’ crimson

The leaves fall from the limbs an’

The branches cast their shadows over stone

Won’t you meet me out in the moonlight alone?

Beware Miss Lonely! You do not want to meet this Jack the Ripper out in the moonlight alone, or any of Dylan’s other stalker shadows for that matter.

Shadow Selves

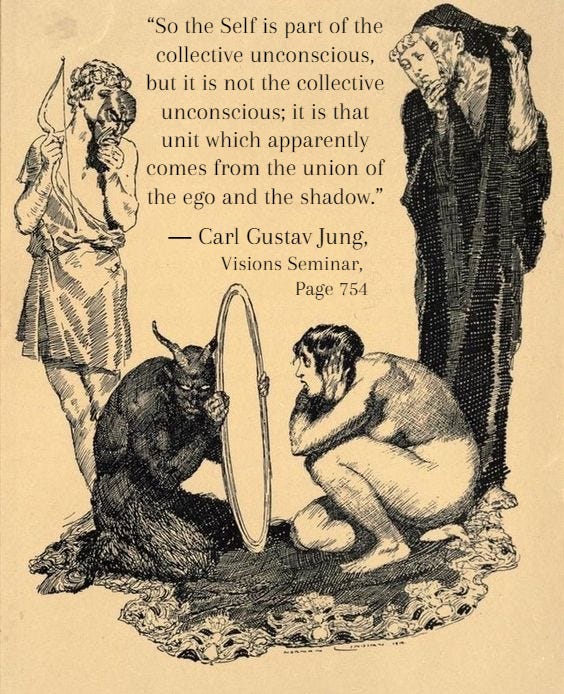

Pioneering psychologist Carl Jung referred to the shadow as an integral part of the individual psyche and an archetype in the collective unconscious. In Aion: Researches into the Phenomenology of the Self, Jung defines the shadow as “that hidden, repressed, for the most part inferior and guilt-laden personality whose ultimate ramifications reach back into the realm of our animal ancestors and so comprise the whole historical aspect of the unconscious” (266). This repressed component of the personality festers in the dark corners of the unconscious, where it threatens the wellbeing of the conscious self. As Jung put it in Psychology and Religion: West and East, “Unfortunately there can be no doubt that man is, on the whole, less good than he imagines himself or wants to be. Everyone carries a shadow, and the less it is embodied in the individual’s conscious life, the blacker and denser it is” (76)

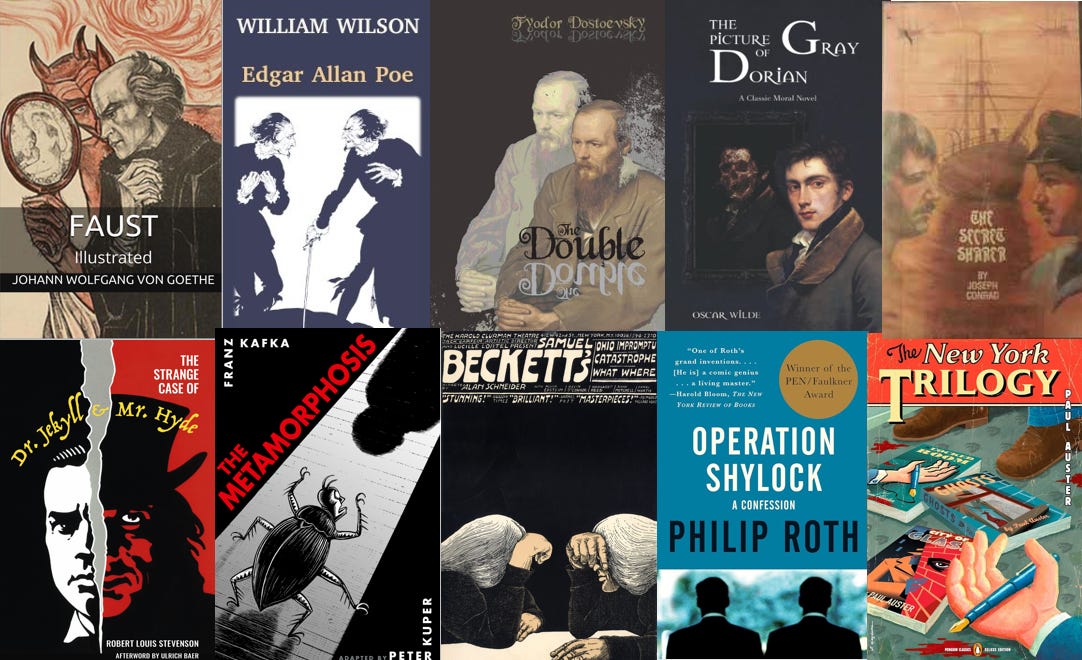

The dark side of the self is often depicted artistically in the form of a doppelganger. Otto Rank wrote a groundbreaking study of the subject called The Double: A Psychoanalytic Study [first published in German in 1914 as Der Doppelgänger]. Rank studies a wide variety of doubles in literature, film, and myth, and he distills down two main strands:

[1] pathological self-love as in Greek legend or in Oscar Wilde, the representative modern esthete; [2] or in the defensive form of the pathological fear of one’s self, often leading to paranoid insanity and appearing personified in the pursuing shadow, mirror-image, or double (85-86)

These two forms of the double lead down one of two paths: “So it happens that the double, who personifies narcissistic self-love, becomes an unequivocal rival in sexual love; or else, originally created as a wish-defense against a dreaded eternal destruction, he reappears in superstition as the messenger of death” (86). Even before pioneering psychologists like Jung and Rank gave us clinical terminology for these ideas, artists were already mapping out the shadow country.

Dylan was born on May 24, 1941, which makes him a Gemini, the zodiac sign for the twins. He regards doubles, twins, and shadows as part of his astrological birthright. As he told Neil Hickey of TV Guide in 1976, “My being a Gemini explains a lot, I think. […] It forces me to extremes. I’m never really balanced in the middle. I go from one side to the other without staying in either place very long. I’m happy, sad, up, down, in, out, up in the sky and down in the depths of the earth. I can’t tell you how Bob Dylan has lived his life. And it’s far from over” (520). Sounds like a tug-o’-war with his shadow self. Note that he even refers to “Bob Dylan” like a separate person, an alien alter-ego.

Dylan’s dueling doppelgangers assume many forms. Sometimes the battle is staged between sibling rivals, as in “Tweedle Dee & Tweedle Dum,” or the allusion to Cain and Abel in “Every Grain of Sand.” If you’re willing to stretch the definition of brother vs. brother to cover the black vs. white chess metaphor of “Only a Pawn in Their Game,” we can trace the conflict all the way back to Byron De La Beckwith stalking and killing Medgar Evers:

But when the shadowy sun sets on the one

That fired the gun

He’ll see by his grave

On the stone that remains

His epitaph plain

Only a pawn in their game

The battlefield of doubles often lies within the singer’s psyche. Think of “Where Are You Tonight? (Journey through Dark Heat)”: “I fought with my twin, that enemy within / ’Til both of us fell by the way.” Or there’s the “shadowy world” of “Jokerman,” where the singer is “Keeping one step ahead of the persecutor within.” Infidels also contains the epitome of split-self rivalry, “I and I,” with the warning “No man sees my face and lives.” God to Moses, yes, but in the present context, the song also dramatizes the confrontation of shadow selves.

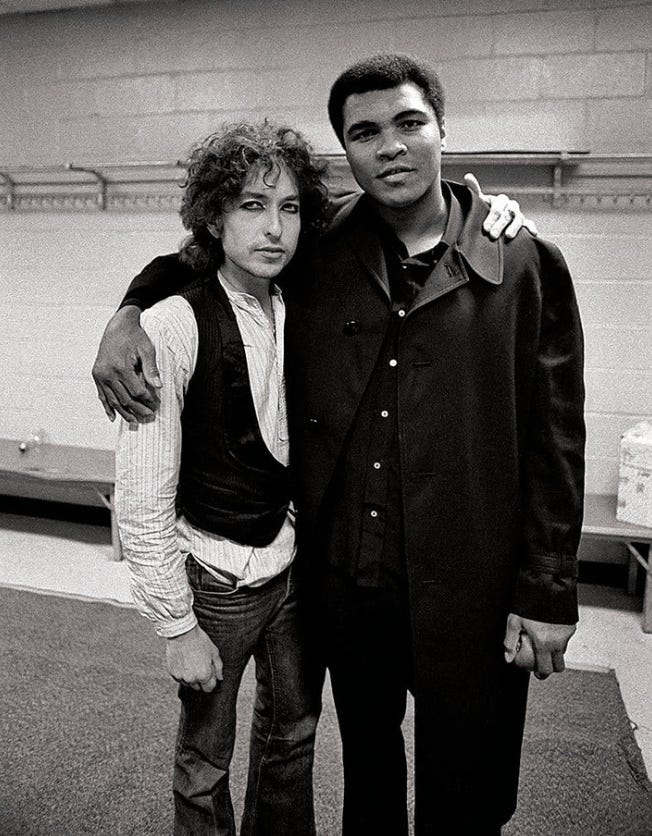

Occasionally, Dylan invokes shadow imagery to depict this struggle. Funny enough, one of the earliest examples takes a comic approach. I’m referring to “I Shall Be Free No. 10” from Another Side of Bob Dylan (even the album title suggests multiple personalities). Instead of the chess analogy used in “Only a Pawn in Their Game,” Dylan moves the competition to a boxing ring: “I was shadow boxing early in the day / I figured I was ready for Cassius Clay.”

It’s a ludicrous image—the lightweight singer duking it out with the heavyweight world champ—and Dylan plays it for laughs. But the shadow imagery is no accident. He offers a similar pairing in the first verse, only this time he depicts himself as the listener’s double:

I’m just average, common too

I’m just like him, the same as you

I’m everybody’s brother and son

I ain’t different than anyone

It ain’t no use a-talkin’ to me

It’s just the same as talkin’ to you

That isn’t the first instance where Dylan depicts a shadow relationship between artist and audience. Consider “Eternal Circle,” an outtake from The Times They Are A-Changin’.

I sang the song slowly as she stood in the shadows

She stepped to the light as my silver strings spun

She called with her eyes to the tune I’s a-playing

But the song it was long and I’d only begun

This song strikes me as a beatnik variation of the Narcissus & Echo myth. The silent woman is drawn to the singer like Echo to Narcissus; Dylan even adds an echo: “As the tune drifted out / She breathed hard through the echo.” But the narcissistic singer is too enamored with his own art to answer her love in time, leaving him stuck eternally singing to his own shadow.

It’s no wonder that Dylan was attracted to the song “We Three (My Echo, My Shadow, and Me).” In true shadow fashion, this song was a hit for two separate groups in 1940, The Ink Spots and Frank Sinatra with the Tommy Dorsey Orchestra. Both acts took “We Three” up to (of course) #3 on the Billboard charts. The lyrics express self-fragmentation in explicit terms: “We three, we’re not a crowd / We’re not even company / My echo, my shadow, and me.” The echo and shadow from this song may even foreshadow “Eternal Circle,” as when the singer croons, “We three, we’ll wait for you / Even ’til eternity / My echo, my shadow, and me.”

Dylan covered the song (of course) three times in concert in the 1980s. Interestingly, after the first performance above (Budokan, 1986), he immediately followed it with the split-self “I and I.”

One of his most interesting and multi-layered songs about shadow selves is “Tell Ol’ Bill,” composed in 2005 for the film North Country. In the second verse, the singer is alone, arguing with the shadow in his mind:

The tempest struggles in the air

And to myself alone I sing

It could sink me then and there

I can hear the echoes ring

I tried to find one smiling face

To drive the shadow from my head

I’m stranded in this nameless place

Lying restless in a heavy bed

Later in the song, however, he claims that he is not alone:

Tell ol’ Bill when he comes home

That anything is worth a try

Tell him that I’m not alone

And that the hour has come to do or die

Well, which is it? Answer: it’s both. The shadow self is simultaneously internal and external, latent and manifest. There’s a term for what Dylan is doing here, one weighted with mystical significance: transfiguration.

It’s a concept with specific Christian connotations. The Gospels of Matthew, Mark, and Luke all recount a fateful trip Jesus took to a mountaintop with the apostles Peter, James, and John. According to Matthew, Jesus “was transfigured before them: and his face did shine as the sun, and his raiment was white as the light. And behold, there appeared unto them Moses and Elias talking with him” (Matthew 17:1-3). This is regarded as one of the greatest Christian miracles, one that affirmed Jesus as the son of God, the messiah foretold by generations of prophets (represented by Elijah) and the fulfillment of divine law (signified by Moses). God sanctifies the transfiguration, appearing in the form of a cloud to deliver his blessing: “While he yet spake, behold, a bright cloud overshadowed them: and behold a voice out of the cloud, which said, This is my beloved Son, in whom I am well pleased; hear ye him” (Matthew 17:5).

Dylan invokes the transfiguration of Jesus directly in the opening verse of “Tell Ol’ Bill”: “The heavens never seemed to near / All of my body glows with flame.” The singer adopts the perspective of Jesus, simultaneously singular and multiple, imbued by the holy spirits of Moses and Elijah and overshadowed by God.

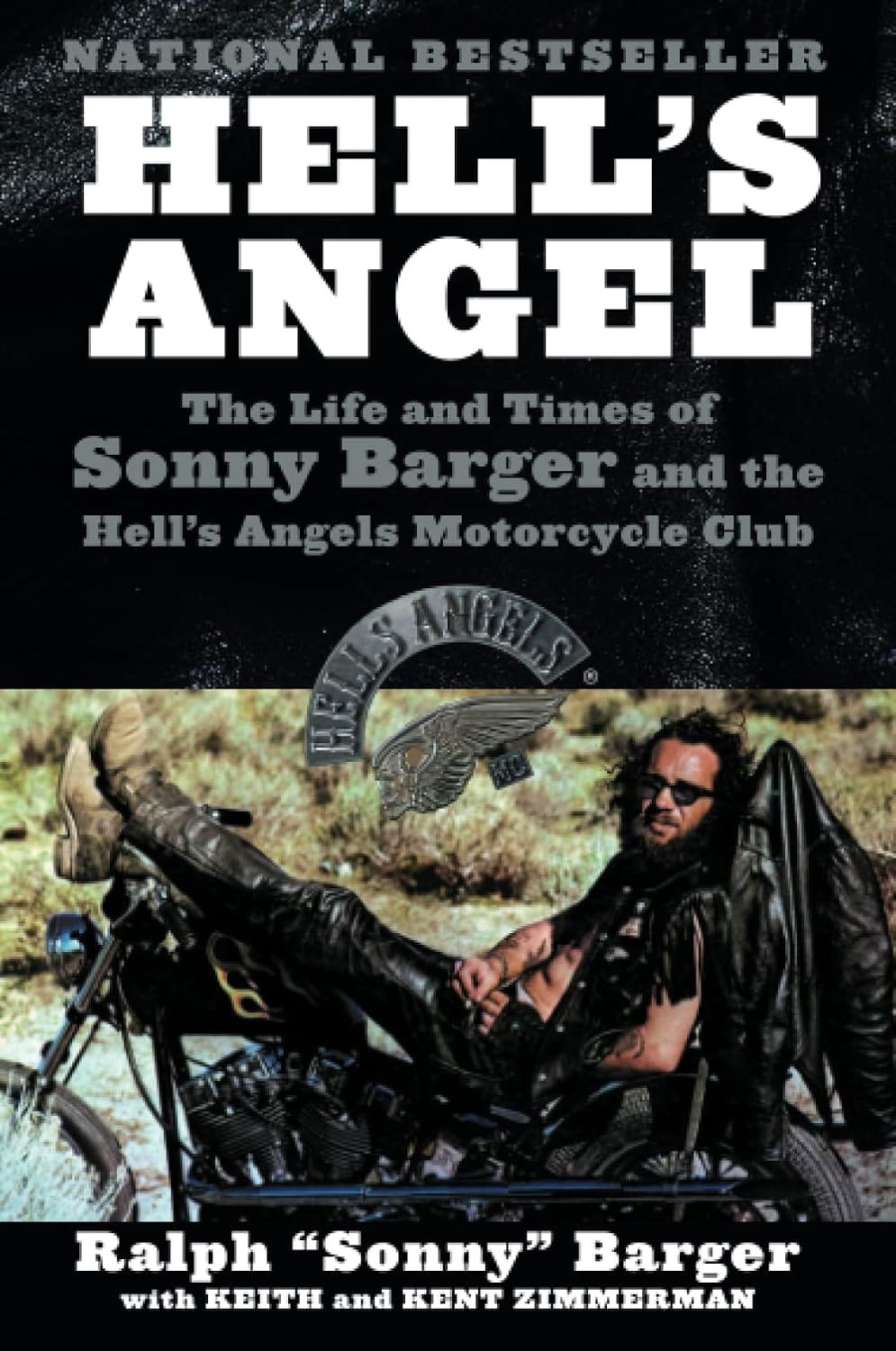

That’s the Christian interpretation, but Dylan has more idiosyncratic notions about transfiguration, as he tried to explain to Mikal Gilmore in his 2012 Rolling Stone interview. Dylan came prepared to discuss this subject, bringing along a copy of Hell’s Angel: The Life and Times of Sonny Barger and the Hell’s Angels Motorcycle Club, written by Barger with Keith Zimmerman and Kent Zimmerman as co-authors. He asks, “Do those names ring a bell? Do they look familiar? Do they? You wonder, ‘What’s that got to do with me?’ But they do look familiar, don’t they? And there’s two of them there. Aren’t there two? One’s not enough? Right?” Obviously, the Zimmermans share Bob’s original surname, and the fact that there are two of them taps into his long-running interests in twins, doubles, and rival siblings.

Dylan is most interested in talking about Bobby Zimmerman. He has Gilmore read a passage from the book about the death of a young man named Bobby Zimmerman in a motorcycle accident. Dylan relates very personally to this event: “You know what this is called? It’s called transfiguration.” He claims that he himself has been transfigured: “I’m not like you, am I? I’m not like him, either. I’m not like too many others. I’m only like another person who’s been transfigured.” Because of his transfiguration, the man that sits before Gilmore in 2012 is no longer the same man that the Rolling Stone journalist thought he was interviewing:

So when you ask some of your questions, you’re asking them to a person who’s long dead. You’re asking them to a person that doesn’t exist. But people make that mistake about me all the time. I’ve lived through a lot. […] Transfiguration is what allows you to crawl out from under the chaos and fly above it. That’s how I can still do what I do and write the songs I sing and just keep on moving.

Dylan’s understanding of transfiguration is rather puzzling and unconventional, but he seems to conflate the Christian miracle of transfiguration with ancient Western notions of metempsychosis [transmigration of souls] and Eastern beliefs in samsara [reincarnation], mixed together with psychological and astrological figures of doppelgangers and shadow selves.

“Tell Ol’ Bill” is a shadow song in yet another sense, transfiguring two main musical sources: “Tell Old Bill” and “I Never Loved but One.” “Tell Old Bill” was in the folk repertoire of several musicians Dylan admired, including Dave Van Ronk and Joni Mitchell. Dylan himself performed a sensitive cover for the Self Portrait sessions, later released on Another Self Portrait as “This Evening So Soon.” In this recording, Dylan tips his cap to folk singer Bob Gibson as his model:

Dylan’s arrangement of “Tell Ol’ Bill” evolved significantly in multiple studio takes. Reserve an hour of your time someday and listen to the studio sessions for “Tell Ol’ Bill,” which is one of the most fascinating chronicles of Dylan’s creative process you’ll ever hear. Through its many iterations, the rhythmic heart of the song continues to beat in time with The Carter Family’s captivating “I Never Loved but One.”

I look around but cannot trace

One welcome word or smiling face

In gazing crowds I am alone

Because I never loved but one

Dylan echoes: “I tried to find one smiling face / To drive the shadow from my head.” As “Tell Ol’ Bill” deftly shows, you’re never truly alone when shadows follow wherever you go. The Carter Family famously counseled listeners to “Keep on the Sunny Side” and to find “Sunshine in the Shadows.” However, in the songs we’re considering for this series, Dylan prefers instead to pitch his tent among the deepening shades.

Shadow Kingdoms

In these final two sections, I want to contextualize Dylan’s shadows within larger traditions of shadow art. An older meaning for the word “shadow” is “mirror reflection.” For example, consider this exchange from Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar:

CASSIUS: Tell me, good Brutus, can you see your face?

BRUTUS: No, Cassius; for the eye sees not itself

But by reflection, by some other things.

CASSIUS: ’Tis just

And it is very much lamented, Brutus,

That you have no such mirrors as will turn

Your hidden worthiness into your eye,

That you might see your shadow. (1.2.51-58)

When a group of traveling players passes through Elsinore in Hamlet, the dark prince reminds them of their basic job as performing artists: “…the purpose of playing whose end, both at the first and now, was and is to hold as ’twere the mirror up to Nature” (3.2.20-22).

But mirrors can also be used to distort what they reflect. In that regard, “shadows” are associated with fraudulence: fake imitations of reality. That is the sense of shadows at play in this tense encounter between the ascendant King Henry and the deposed King Richard in Shakespeare’s Richard II. Richard calls for a looking-glass with which to examine his misery. Surprised to discover that he still looks the same, despite his recent ruin, he shatters the lying mirror, breaking his reflection into shards: “For there it is, cracked in an hundred shivers. / Mark, silent King, the moral of this sport, / How soon my sorrow hath destroyed my face.” Henry counters him with a clever play on words: “The shadow of your sorrow hath destroyed / The shadow of your face.” Richard finds harsh truth in this charge of false appearances:

Say that again!

The shadow of my sorrow? Ha, let’s see.

’Tis very true, my grief lies all within;

And these external manners of laments

Are merely shadows of the unseen grief

That swells with silence in the tortured soul. (4.1.289-98)

Along similar lines, the OED adds a further meaning of “shadow” as an actor or a play: “Applied rhetorically to a portrait, as contrasted with the original; also, to an actor or a play, in contrast with the reality represented.” The best example of this connotation is in Puck’s epilogue for A Midsummer Night’s Dream:

If we shadows have offended,

Think but this, and all is mended,

That you have but slumber’d here

While these visions did appear. (5.2.409-12)

Performers are depicted here as figments in a mirror reality, the dream world of shadow art.

The Bard of Hibbing frequently draws inspiration from the Bard of Avon. Don’t take my word for it: read the definitive book on the subject by Andrew Muir, The True Performing of It: Bob Dylan & William Shakespeare, and then check out Andy’s further thoughts on the subject at More True Performing. Like Shakespeare, Dylan frequently blends his shadows with dreams and playacting.

We shouldn’t be surprised to encounter shadows in “Series of Dreams,” a phantasmal outtake from Oh Mercy. In a verse that appears in the Tell Tale Signs version (but disappears from The Bootleg Series Vols. 1-3), the singer conjures these dream visions:

Thinkin’ of a series of dreams

Where the middle and the bottom drop out

And you’re walking out of the darkness

And into the shadows of doubt

Wasn’t goin’ to any great trouble

You believe in it’s whatever it seems

Nothin’ too heavy to burst the bubble

Just thinkin’ of a series of dreams

Dylan’s shadows sometimes speak a dream language in which Shakespeare feels like a Rosetta Stone. In another outtake, “Can’t Escape from You,” written in 2005 for a film that was never completed, the melancholy singer muses,

I cannot grasp the shadows

That gather near the door

Rain falls round my window

I wish I’d see you more

The path is ever winding

The stars they never age

The morning light is blinding

All the world’s a stage

You can’t miss the allusion to melancholy Jaques in Shakespeare’s As You Like It:

All the world’s a stage,

And all the men and women merely players.

They have their exits and their entrances,

And one man in his time plays many parts. (2.7.140-43)

Dylan and director Alma Har’el bring Jaques’s proverb to life (or death) in Shadow Kingdom. “One man in his time plays many parts” indeed. The transfigured older Dylan performs songs by his younger self, sometimes dressed in white and sometimes in black, sometimes illuminated by the spotlight and sometimes shrouded in shadows. “I can suck melancholy out of a song as a weasel sucks eggs” brags Jaques, and Dylan can make the same boast in Shadow Kingdom. Dylan and Har’el construct an alternate reality from these old songs. The shadow king and his shadow blasters perform in an underworld dive-bar for languid shades.

Shadow Kingdom isn’t Dylan’s only dream world populated by shadows. “Changing of the Guards” feels like a Tarot deck come to life: heroes and witches, merchants and thieves, towers and stairs and the wheel of fortune. I don’t know Tarot well enough to decode all the symbolism. Dearbhla Egan may be right that Dylan was inspired more by the visual imagery of the deck than to any coherent archetypal narrative.

When Jonathan Cott asked about Tarot connections to songs on Street-Legal, Dylan dodged the question: “I’m not really too acquainted with that, you know.” Pressed further, he described those songs like figments from a dream: “we’re all dreaming, and these songs come close to getting inside that dream. It’s all a dream anyway” (Cott 671). Tarot becomes just another Rosetta Stone for translating dream imagery into another Dylanesque shadow kingdom.

Another late example is “Scarlet Town” from Tempest. Dylan looks into the mirror of the classic folk song “Barbara Allen” and leads us through the looking-glass. Both songs begin “In Scarlet Town where I was born,” and both feature sweet William on his deathbed. But then Dylan veers off into an alternate reality, populating his dream with a mashup of strange phantoms, from Little Boy Blue and Mistress Mary, to nameless beggars and drug-addicted prostitutes.

Along with riffing off “Barbara Allen,” the singer echoes Vern Gosdin’s “Set ’Em Up Joe,” which itself echoes Ernest Tubbs’s “Walking the Floor,” and even sneaks in a reference to Sam Cooke & The Soul Stirrers’ “Touch the Hem of His Garment.” If you follow Desolation Row to the end of the line, you’ll find yourself in Scarlet Town. You’ll also find yourself immersed again in Dylan’s shadow art:

Scarlet Town in the hot noon hours

There’s palm-leaf shadows and scattered flowers

Beggars crouching at the gate

Help comes but it comes too late

By marble slabs and in fields of stone

You make your humble wishes known

I touched the garment but the hem was torn

In Scarlet Town where I was born

This is one of the most striking songs from Tempest, but it really came into its own later in concert. Here is my favorite live version, from North Charleston in 2018:

With Dylan hiding out these days behind his piano, lamps, and hoodies, it’s refreshing to see him out in the open, strutting his stuff at center stage and accompanied by a fantastic NET band. This performance is good enough to earn him a pardon for dropping the verse about shadows.

Shadow Chasers

Let’s complete the circle by returning to where we started in Part 1. Dylan’s first shadow chaser is the ragged clown in “Mr. Tambourine Man”:

And if you hear vague traces of skipping reels of rhyme

To your tambourine in time

It’s just a ragged clown behind

I would pay it any mind

It’s just a shadow you’re seeing that he’s chasing

This is my favorite Dylan shadow. It’s a cipher that contains so many other connotations of shadows that we’ve been considering in this series. The clown follows the musician like a shadow. Maybe he’s simply amused by the tambourine man, or perhaps he is hypnotized by the music and obeys the siren call in a trance.

Since the singer depicts himself as following the charismatic musician, too, the ragged clown is often viewed as Dylan’s self-portrait embedded into the song. Mr. Tambourine Man can be viewed as a muse, guiding the singer out of the darkness and into the dawn of new artistic possibilities. But we must also acknowledge that, like the darker versions of the Pied Piper story, the musician might actually be leading the singer toward his death. For the fatal implications of the song, see my recent comparison of “Mr. Tambourine Man” with “House Carpenter.”

In fact, it’s not entirely clear that the clown is following the musician at all: “It’s just a shadow you’re seeing that he’s chasing.” Whose shadow—the musician’s or his own? We’re drifting into the territory of doppelgangers and shadow selves again, and maybe even the kind of stalking Dylan knows all too well from obsessive fans and critics.

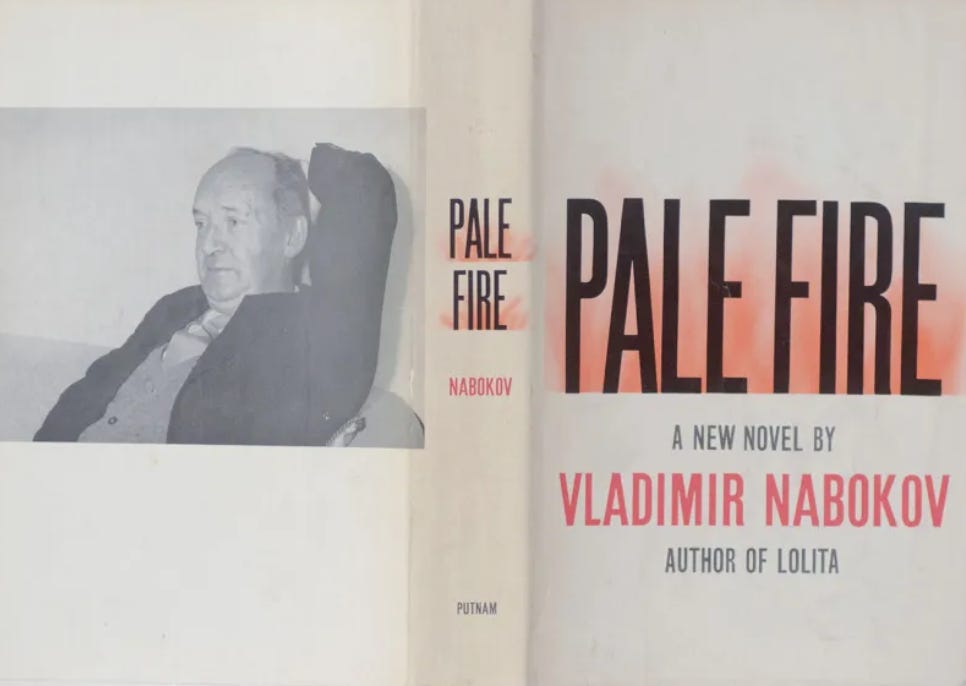

Once I start thinking about Dylanology in terms of shadow chasing, I’m reminded of one of my all-time favorite novels, Vladimir Nabokov’s Pale Fire. It’s a brilliant first-person examination of madness and a lacerating satire of the excesses of academia and literary scholarship. Nabokov parodies critics’ relentless fixation on their subjects, fluctuating between the ludicrous and the pathological, as an imaginary annotator stalks his chosen artist and tries to throttle all the meaning out of his work. There’s plenty of self-lampoon in this portrait, too, since Nabokov was both an artist and a critic. He knows his song well before he starts singing. He spent 14 years working on a translation of Pushkin’s Eugene Onegin, which stretched to four volumes, consisting mostly of Nabokov’s exhaustive annotations.

In Pale Fire, Nabokov invents a shadow-poet named John Shade, composes Shade’s epic poem “Pale Fire,” writes an elaborate commentary on the poem by the shadow-critic Charles Kinbote, and creates a fabulous fantasy in which the delusional critic believes he is Charles the Beloved, exiled King of Zembla [“a land of reflections, of ‘resemblers’” (265)]. Charles Kinbote is Nabokov’s King of Shadows. The author orchestrates the accidental murder of John Shade by a madman, whom Kinbote imagines as a hitman sent by the regicidal revolutionary group The Shadows.

To add one final looking-glass to this dizzying hall of metafictional mirrors, there are hints to suggest that the entirety of Pale Fire was composed not by Shade or Kinbote but by Vseslav Botkin, an eccentric Russian émigré and visiting professor in America—i.e., an avatar for Nabokov himself. Mirrors within mirrors, shadows of shadows.

As you can tell, I deeply identify with shadow chasers. Dylan is the tambourine man whose shadow I keep chasing, but sometimes I’m probably just chasing my own shadow, following figments of my imagination. So be it. Fortunately for me, there are enough likeminded shadow chasers out there to form a community.

In our defense, we’re following Dylan’s lead, since he has also been on a perpetual shadow chase for over sixty years as a performer. I don’t know what he’s trying to track down, and maybe he doesn’t either, but it’s certainly not that ragged clown. After the 1960s, he has routinely dropped the third verse of “Mr. Tambourine Man” in live performance. But that seems appropriate, doesn’t it? Dylan’s quintessential shadow chaser has been permanently relegated to dark oblivion. Ah well, no worries. There are still plenty of us walking in his footsteps and continuing the search.

Works Cited

Cott, Jonathan. “The Rolling Stone Interview, Part 2.” Rolling Stone (16 November 1978). Rpt. in Every Mind Polluting Word: Assorted Bob Dylan Utterances. Ed. Artur Jarosinski. Don’t Ya Tell Henry, 2006, 668-78.

Dylan, Bob. Chronicles, Volume One. Simon & Schuster, 2004.

---. Official Lyrics. The Official Bob Dylan Website.

https://www.bobdylan.com/.

---. The Philosophy of Modern Song. Simon & Schuster, 2022.

Egan, Dearbhla. “Changing of the Guards and the Tarot.” Untold Dylan (25 July 2015), https://bob-dylan.org.uk/archives/1417.

Gilmore, Mikal. “Bob Dylan Unleashed.” Rolling Stone (27 September 2012). https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-news/bob-dylan-unleashed-189723/.

Hickey, Neil. Interview with Bob Dylan. TV Guide (11 September 1976). Every Mind Polluting Word: Assorted Bob Dylan Utterances. Ed. Artur Jarosinski. Don’t Ya Tell Henry, 2006, 520-23.

The Holy Bible. King James Version.

Jung, C. G. Aion: Researches into the Phenomenology of the Self, 2nd edition. Collected Works of C. G. Jung, Volume 9, Part II. Trans. R. F. C. Hull. Eds. Herbert Read, Michael Fordham, and Gerhard Adler. Princeton University Press, 1968.

---. Psychology and Religion: West and East. Collected Works of C. G. Jung, Volume 11. Trans. R. F. C. Hull. Eds. Herbert Read, Michael Fordham, and Gerhard Adler. Princeton University Press, 2014.

Latham, Sean. “Roadhouse on the River Styx.” TU Institute for Bob Dylan Studies (20 July 2021), https://dylan.utulsa.edu/roadhouse-on-the-river-styx/.

Muir, Andrew. The True Performing of It: Bob Dylan & William Shakespeare, updated edition. Red Planet Books, 2020.

Nabokov, Vladimir. Pale Fire. Random House, 1962.

Rank, Otto. The Double: A Psychoanalytic Study. Trans. and ed. Harry Tucker, Jr. New American Library, 1971.

Shadow Kingdom: The Early Songs of Bob Dylan. Directed by Alma Har’el. Veeps, 2021.

Shakespeare, William. As You Like It. Arden Shakespeare Third Series. Ed. Juliet Dusinberre. Bloomsbury, 2006.

---. Hamlet. Second Quarto. Arden Shakespeare Third Series. Eds. Ann Thompson and Neil Taylor. Bloomsbury, 2006.

---. Julius Caesar. Arden Shakespeare Third Series. Ed. David Daniell. Bloomsbury, 1998.

---. A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Arden Shakespeare. Ed. Harold Brooks. Methuen, 1979.

---. Richard II. Arden Shakespeare Third Series. Ed. Charles R. Forker. Thomson Learning, 2004.

Re: Jungian psychology and Dylan in newsöetter-"Dylan’s dueling doppelgangers assume many forms." Could that in 'Black Rider' be his most intimate and personal?

Thanks for the kind words, Graley, but even more so for your detailed and stimulating continuation. I can hardly wait for part 3. I'll save further comments on your 'shadowy sojourn' until then.

On a reading aside, that chimes with previous exchanges here in Substackland, I'm delighted to see Dostoyevsky feature and hope that sends you on a run of reading the other "big D." It would only be fair as, due to you returning me to Don DeLillo, (via your Murder Most Foul piece), I’ve recently read not just Libra, but also Underworld, Great Jones Street and White Noise, so you are due a few Dostoyevskys in return. I've only Mao II to go from Don D, now.

All power to your pen, Graley, I'm not sure how you can keep up this pace and high quality output, but I'm very grateful that you do and I know I'm not alone in this.