Gender Performance, Part 2

Ricky Nelson

In the first installment of this series, I considered ways in which Johnnie Ray offered an alternative model of masculinity. His gender performance deviated significantly from the predominant behavior, values, and emotions that young Bobby Zimmerman was taught to embody and express (or repress) as a young man growing up in forties and fifties America.

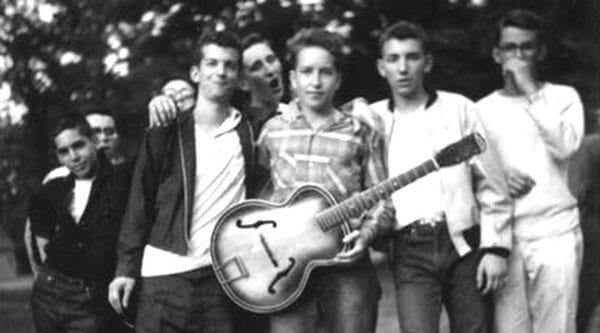

In this second installment, I want to take a step back and establish the baseline. If you weren’t supposed to look and act and sound like Johnnie Ray, then what did the ideal teen boy look and act and sound like? Easy—like this:

Ricky Nelson

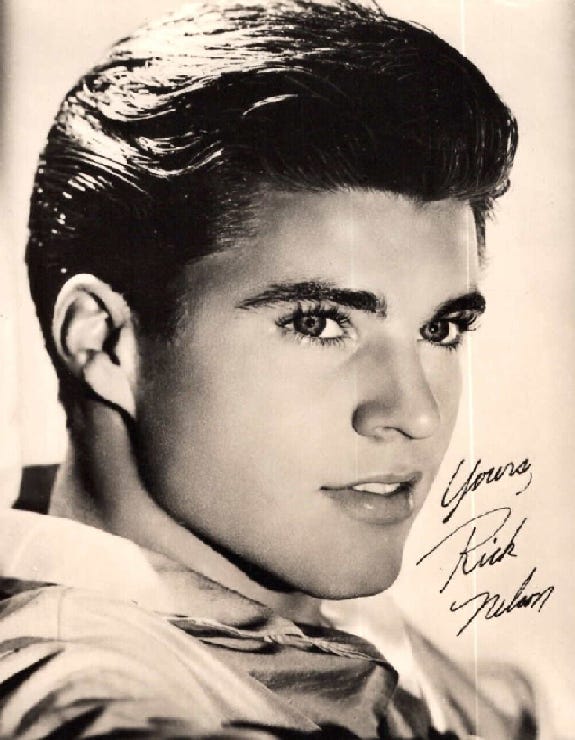

Eric Hilliard Nelson was born May 8, 1940, making him only a year older than Robert Allen Zimmerman. But what different lives the two boys led. Ricky and brother David—Bobby had a brother David, too—played themselves on the long-running hit show The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet, starring their real-life/TV parents. Ricky emerged as a heartthrob for teen girls and a role model for teen boys, particularly after he began regularly playing a mellow version of early rock & roll on the show.

One of Nelson’s admirers was Bobby Zimmerman. In Chronicles, Dylan recalls, “Ricky had a smooth touch, the way he crooned in fast rhythm, the tonation of his voice. He was different than the rest of the teen idols, had a great guitarist [James Burton] who played like a cross between a honky-tonk hero and a barn-dance fiddler” (14). In his youth, Bobby identified in certain respects with his TV counterpart: “I’d always felt kin to him, though. We were about the same age, probably liked the same things, from the same generation although our life experience had been so dissimilar, him being brought up out West on a family TV show” (14).

In later years, the two men’s musical careers would intersect several times. Dylan writes in Chronicles,

Ricky’s talent was very accessible to me. I felt we had a lot in common. In a few years’ time he’d record some of my songs, make them sound like they were his own, like he had written them himself. He eventually did write one himself and mentioned my name in it [“Garden Party”]. Ricky, in about ten years’ time, would even get booed while onstage for changing what was perceived as his musical direction. It turned out we did have a lot in common. (14)

Nelson covered “She Belongs to Me,” “If You Gotta Go, Go Now,” and “I Shall Be Released” on Ricky Nelson in Concert (1970); and “Just Like a Woman” and “Love Minus Zero / No Limit” on Rudy the Fifth (1972). I think my favorite of the bunch is “Just Like a Woman,” which, as Laura Tenschert has argued, is a song very much about gender performance:

Dylan’s continuing admiration for Nelson has taken multiple forms. Here is a recording of Dylan singing Nelson’s “Lonesome Town” with Tom Petty in 1986:

More recently, Dylan drops in a couple Nelson allusions on Rough and Rowdy Ways. He namechecks Nelson’s “Hello Mary Lou” in “False Prophet,” and the line “Take me out traveling, you’re a traveling man” in “I’ve Made Up My Mind to Give Myself to You” nods toward Nelson’s hit “Travelin’ Man.” Dylan also devotes a chapter to Nelson in The Philosophy of Modern Song. More on that below.

But before we leave Chronicles, I should point out that there were strict limits to Dylan’s identification with Nelson. For all the teen idol’s charm, Bobby Zimmerman ended up following different mentors and models for gender performance. Some of the barriers between them were erected by Dylan himself because of diverging musical tastes. He claims, “Nelson had never been a bold innovator like the early singers who sang like they were navigating burning ships. He didn’t sing desperately, do a lot of damage, and you’d never mistake him for a shaman. It didn’t feel like his endurance was ever being tested to the utmost” (Chronicles 14).

In retrospect, and maybe even at the time, Dylan could see that the order was rapidly fadin’: “I had been a big fan of Ricky’s and still like him, but that type of music was on its way out. It had no chance of meaning anything. There’d be no future for that stuff in the future. It was all a mistake” (Chronicles 14). Dylan was beginning to hear his calling from folk music, which offered a world of greater substance and more brilliant dimensions than Nelson’s material:

What was not a mistake was the ghost of Billy Lyons, rootin’ the mountain down, standing ’round in East Cairo, Black Betty bam be lam. That was no mistake. That’s the stuff that was happening. That’s the stuff that could make you question what you’d always accepted, could litter the landscape with broken hearts, had power of spirit. Ricky, as usual, was singing bleached out lyrics. Lyrics probably written just for him. (14)

Dylan’s rejection of Ricky Nelson was representative of his larger indictment against the prevailing values of the entire era: “Practically speaking, the ’50s culture was like a judge in his last days on the bench. It was about to go. Within ten years’ time, it would struggle to rise and then come crashing to the floor. With folk songs embedded in my mind like a religion, it wouldn’t matter. Folk songs transcended the immediate culture” (27).

But Dylan didn’t feel entirely welcome in the folk music fraternity either. He perceived invisible barriers erected by others, older and larger forces beyond his control, designed to bar his admission or limit his inheritance.

Dylan’s lifelong friend Louie Kemp believes that Dylan’s Jewish upbringing plays an integral role in his art. In Kemp’s view,

Supporting the underdog is virtually second nature to Jews because we have so often been in that position ourselves. We seem to have a sixth sense when it comes to persecution, discrimination, and injustice, and many of us have devoted our lives to battling these things. There’s no question in my mind that Bob’s drive to write songs that mattered was born at least in part from his roots as a Jew. (40-41)

Be that as it may, Dylan’s Jewish identity also exposed him to discrimination. As Seth Rogovy reminds us, “Working-class towns composed mostly of immigrant Catholics tended to be hotbeds of anti-Semitism across America. Growing up middle-class and Jewish in Hibbing made Bobby Zimmerman feel different from the others, separate, an object of suspicion, and alienated from his peers” (23).

Dylan’s move to New York City may have given him a fuller sense of cultural and musical community, but as Chronicles shows, he still experienced insecurity and social anxiety connected to his Jewishness. This is most clearly communicated in reflections on Mike Seeger.

The Seegers and The Nelsons

Dylan admired and envied Mike Seeger. A member of the New Lost City Ramblers and half-brother to Pete Seeger, Mike Seeger was an expert folk musician who seemed hardwired and predestined for greatness. Pay attention to Dylan’s preoccupation with blood in his description of Seeger:

He was like a duke, the knight errant. As for being a folk musician, he was the supreme archetype. He could push a stake through Dracula’s black heart. He was the romantic, egalitarian, revolutionary type all at once—had chivalry in his blood. Like some figure from a restored monarchy, he had come to purify the church. (Chronicles 69-70, emphasis added)

The chronicler depicts Seeger as pure-blooded royalty, someone capable of defeating any blood-sucker who threatened him. With all this emphasis on bloodlines, I think Dylan is communicating that, when he was first trying to break through as a folk musician, he worried that he couldn’t pass folk music’s unofficial yet binding purity test.

After rapidly ascending to the top of the tower, Dylan was unceremoniously toppled at Newport ’65 as the “supreme archetype” of folk, failing the test of purists when he went electric. The villagers sharpened their pitchforks, and another Seeger (allegedly, mythically) raised an ax to fend off the menace. Recalling those tumultuous events decades later in No Direction Home, Dylan was still reeling from the blow: “I heard a rumor that Pete was going to cut the cable. I heard it later, and it didn’t make sense to me, you know. Pete Seeger. Someone whose music I cherish. Someone I highly respect was going to cut the cable. I was like, ‘Ah, God!’ [clutching chest] It was like a dagger.” Or a stake through his black heart?

Young Dylan, the Jewish upstart from Nowheresville, was hyper-conscious that he did not share the Brahmin bloodline of the Seegers, American folk music’s royal family: “What I had to work at, Mike already had in his genes, in his genetic makeup. Before he was even born, this music had to be in his blood” (Chronicles 71, emphasis added). See what I mean? It’s in the blood, or so young Dylan feared. His sense of cultural and religious otherness made him wonder if a Hibbing Zimmerman could ever earn the keys to the kingdom that were the privileged birthright of the Seegers—and the Nelsons.

This brings me back to Dylan’s commentary on Ricky Nelson. One of my favorite lines in Chronicles is this description of Nelson: “It was like he’d been born and raised on Walden Pond where everything was hunky-dory, and I’d come out of the dark demonic woods, same forest, just a different way of looking at things” (14). Nelson features as All-American hero from the All-American family. He is protagonist of a tall tale the nation loves to tell about itself, one of rugged individualism and self-reliance. On the other hand, Dylan depicts himself like a vampire or troll, a demon relegated to the margins of the dark woods.

Ricky Nelson was “the supreme archetype” for what a young man was supposed to aspire to in Bobby Zimmerman’s youth. But gender norms and expectations were inextricable from cultural anxieties and religious barriers. Even if the Hibbing teen wanted to emulate the TV heartthrob, he knew that he didn’t have equal access to that particular American Dream and so would have to find an alternative path—as a musician and as a man.

“Poor Little Fool”

Chapter 11 of The Philosophy of Modern Song is devoted to Ricky Nelson’s first #1 hit, “Poor Little Fool.” Dylan’s commentary on Nelson picks up right where he left off in Chronicles: “Ricky Nelson was a true all-American boy” (POMS 51). At one point, Dylan puffs up Nelson as even bigger than Elvis: “There’s an argument to be made that Ricky, even more than Elvis, was the true ambassador of rock and roll. Sure, when Elvis appeared on Ed Sullivan everybody stopped and took notice, but Ricky was in your house every week” (52). Nelson once again comes across as official spokesman for the fifties American zeitgeist: “Ricky made rock and roll part of the family. And not just for us but all over the world, magically transforming the image on a black and white television into the American dream” (52).

The dream didn’t last. The pleasant illusions simulated by Ricky Nelson, The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet, and “Poor Little Fool” eventually came crashing down. Out of several hit songs Dylan could have chosen by Nelson, I don’t think it’s an accident that he picked this one. The song was composed by Sharon Sheeley, who was only 17 years-old when she wrote it, the same age as Dylan when the song hit #1 in 1958. Sheeley’s boyfriend was another Minnesota musician, Eddie Cochran, who hailed from Albert Lea, MN.

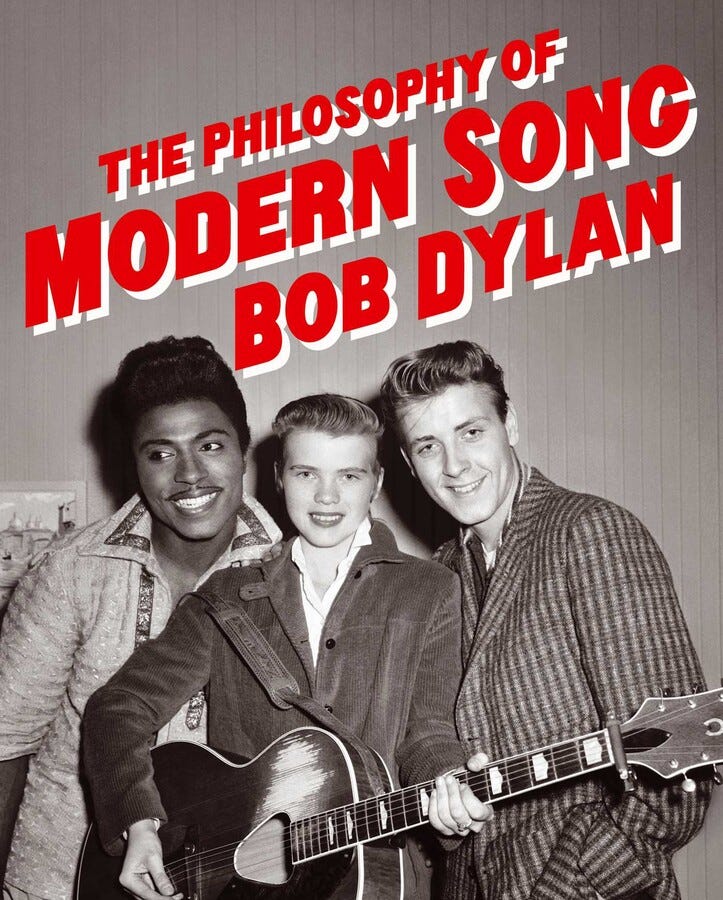

In the conclusion to Chronicles, Dylan lists several prominent figures from his home state: Roger Maris, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Sinclair Lewis, and Eddie Cochran. He identifies with them as fellow Minnesotans and fellow dreamers: “They were all from the North Country. Each one followed their own vision, didn’t care what the pictures showed. Each one of them would have understood what my inarticulate dreams were about. I felt like I was one of them or all of them put together” (292). Dylan shines his brightest spotlight on Cochran by placing him on the cover of The Philosophy of Modern Song:

Cochran shone brightly but briefly, and he met a dark end. He died in a fatal car crash on April 16, 1960, during a UK tour. He was only 21 years-old. Two other passengers survived the crash: fellow musician Gene Vincent and Cochran’s girlfriend and songwriter Sharon Sheeley.

Nelson also died violently and prematurely, in a plane crash on New Year’s Eve, 1985, at only 45 years of age. Car crashes (James Dean, Eddie Cochran), plane crashes (Buddy Holly, Ricky Nelson). Dylan wrote in Chronicles about the 1950s crashing down. In The Philosophy of Modern Song, employing the “art of the unsaid,” he generally avoids spelling these catastrophes out; but he leaves bloody footprints to guide us back to the scenes of these deadly disasters.

Dylan doesn’t dwell exclusively in darkness, discrimination, demonization, and death, however. Actually, I find his riff on “Poor Little Fool” pretty hilarious, if you’re dirty-minded and retain a sophomoric sense of humor.

I can’t shake the notion that, on a very sly and crude level, channeling the hormonal libido of 17-year-old Bobby Zimmerman, Dylan imagines “Poor Little Fool” as a song about the singer’s penis. His riff sounds like the kind of double entendre he delighted in from Little Richard. The riff is an extended dick joke, a cautionary tale about thinking with the wrong head, being misled by your poor little fool, and being left to tend to its demands all by yourself.

Take another look at the first two paragraphs and see what you think:

In the past you entertained yourself with other people’s hearts, you stretched the rules. All you had to do was look at someone the eye and they wasted no time in coming to you, covered the ground in short time.

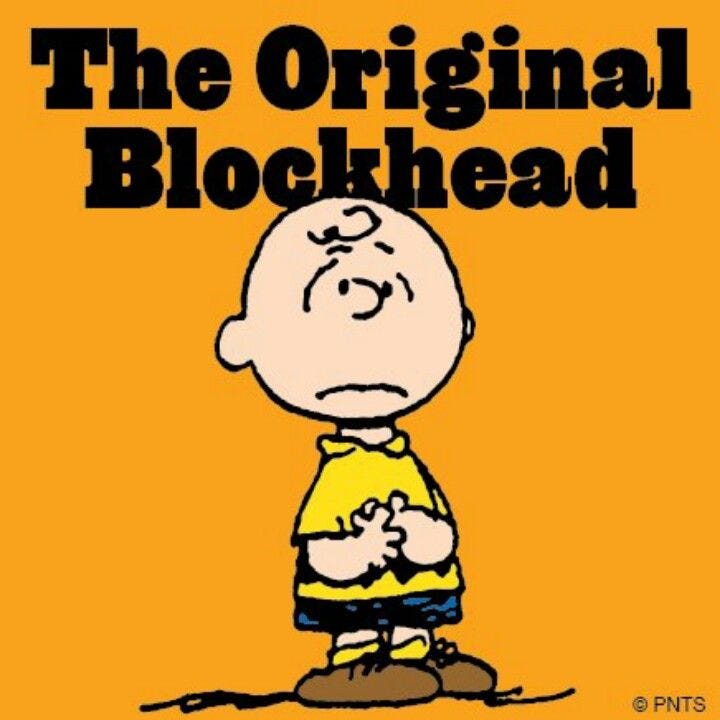

You went on a spree and left a trail of sensitive violated hearts, but that came to an end when you ran up against someone who buckled you, one on one, who made you fall to pieces and eat the dirt. You were brainless, no doubt about that. She played with you and teased you with her happy-go-lucky ways, she was easygoing and cheerful, unbothered. She fondled and stroked you, and with her baby blue peepers she enchanted you, she was a real knockout. She sized you up, she was captivating and shrewd and lousy with lies. Oh yeah, you were an absolute blockhead beyond doubt. (49)

You don’t encounter the word “blockhead” much anymore outside of Charles Schulz’s Peanuts comics; and let’s face it, the head Peanut Charlie Brown is basically a walking, talking penis, right?

Granted, this could all be a figment of my imagination. But I like this interpretation because of its revisionist transgression. Actually, in the present context, a better term for it might be midrash. As Seth Rogovoy explains,

One of the most rewarding ways of approaching Bob Dylan’s lyrics is to read them as the work of a poetic mind apparently immersed in Jewish texts and engaged in the age-old process of midrash: a kind of formal or informal riffing on the texts in order to elucidate or elaborate upon their hidden meanings. (6)

Midrash is also a useful interpretive lens for viewing Dylan’s interpretations of other artist’s songs in The Philosophy of Modern Song. Talmudic scholars probably don’t spend much time looking for references to masturbation and hand jobs in their scriptural exegesis (except maybe for the bit about Onan). But leave it to Dylan to give us a midrash that would have those three stooges Bobby and Louie and Larry rolling with laughter in their bunkbeds at Camp Herzl.

This is yet another side of Dylan’s gender performance. He takes a song by the poster boy of All-American wholesomeness and gives it the Little Richard treatment. It’s basically the opposite of what Pat Boone did when he sanitized “Tutti Frutti.” Dylan throttles this seemingly innocent love ballad until it spills its hidden secrets, turning the song into something bawdy, onanistic, and forbidden. He takes the clean and makes it dirty. He takes the pure and ravishes it. He abducts “Poor Little Fool” out of the living rooms and sock hops and malt shops of fifties America, and drags its corpse through the mud into the dark demonic woods.

Hey, if you can’t join ’em, beat ’em.

Works Cited

Dylan, Bob. Chronicles, Volume One. Simon & Schuster, 2004.

---. The Philosophy of Modern Song. Simon & Schuster, 2022.

Kemp, Louie. Dylan & Me: 50 Years of Adventures. Westrose Press, 2019.

No Direction Home. Directed by Martin Scorsese. Paramount Pictures, 2005.

Rogovoy, Seth. Bob Dylan: Prophet, Mystic, Poet. Scribner, 2009.

Tenschert, Laura. “Episode 9: Women and Dylan.” Definitely Dylan (11 March 2018), https://www.definitelydylan.com/listen/2018/3/11/episode-9-women-and-dylan.

Graley, this is brilliant! It feels spot on, and I will come back to it again to take it in more fully. As before, I feel you must have made a deal at the crossroads to pull off this mind meld with Bob. (Both young and old)! I read this as news of Mr Pecker's testimony blares from the TV (my husband's CNN addiction), which perhaps further testifies to the energies pulsating through the ether these days, ready to be caught and put to the page. This is so fully in the spirit of Bob.

Ok wait, I honestly never noticed the double entendre in the Poor Little Fool riff! That's so funny! I loved learning about Sharon Sheeley and Eddie Cochran as well, I didn't know he was from Minnesota! This whole piece was wonderful, thank you Graley!