Gender Performance, Part 1

Johnnie Ray

I am excited to be participating next month in “Bob Dylan – Questions on Masculinity,” a symposium organized by Anne-Marie Mai and Erin Callahan in Odense, Denmark (May 23-24). The lineup includes some wonderful speakers, and it will be fun to reunite with friends I haven’t seen since last summer’s “World of Bob Dylan” conference in Tulsa. If any of my European readers can make it to Denmark, please look me up and we’ll toast Bob Dylan’s 83rd birthday!

I will be presenting my paper on “Gender Performance in The Philosophy of Modern Song.” My focus will be on key figures from 1950s pop culture who pushed back against the restrictive gender norms of the era. These mentors taught young Bobby Zimmerman how to question, resist, and reimagine masculinity, shifting from a rigid, narrow, stable essence toward variable performances across a broader spectrum. I look forward to sharing this presentation in Denmark, and I will let you know when and where you can read the full published version.

In the meantime, there are several profiles in gender performance that I had to leave out of the Denmark paper due to time constraints. I thought I’d go ahead and share these in a series of pieces for Shadow Chasing.

Johnnie Ray

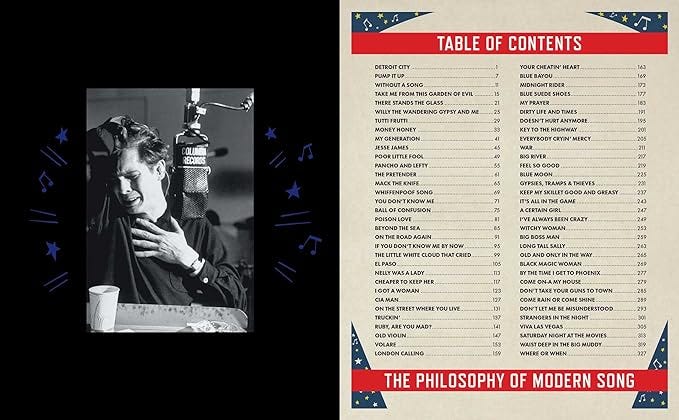

Even before his first chapter, Dylan foregrounds three of his musical heroes in The Philosophy of Modern Song. Little Richard gets pride of place on the cover with a 1957 tour photo, alongside Alis Lesley and Eddie Cochran. Open the book and the first picture you see is Elvis Presley, also from 1957, looking at albums in a record store. Flip forward and you find this evocative photo facing the table of contents:

This image is doing a lot of work. It epitomizes the emotional intensity which was Johnnie Ray’s calling card as a vocalist. It also marks Ray as a fellow Columbia Records recording artist, one of Dylan’s hallowed ancestors in the musical genealogy of The Philosophy of Modern Song.

The placement of Ray’s photo sets up an interesting juxtaposition. It’s as if the singer is so deeply moved by the list of great songs that he is choked with emotion and has to turn away:

“The Prince of Wails” looks like he could fill that coffee cup with tears after getting a glimpse at Dylan’s table of contents and seeing one of his own songs listed.

Johnnie Ray burst onto the scene in 1952 with two hit singles, “Cry” and “The Little White Cloud That Cried.” These songs instantly established him as a teen idol, but his reputation soon withered beneath the glare of celebrity and public scrutiny. He never fully recovered after a series of scandals in tabloids like Confidential with salacious headlines like “Is It True What They Say About Johnnie Ray?” and “Why Johnnie Ray Likes to Go in Drag.” Although these hit jobs were largely based upon unsubstantiated rumors and speculation, Ray’s hidden bisexuality in a time of rampant homophobia made him vulnerable to the charges, as did his arrest for solicitation of an undercover male police officer in 1951.

Well past the zenith of his fame, Ray continued to perform into the late 1980s, and many of his early fans remained faithful supporters. Bobby Zimmerman was one of them. In a 1984 interview with Burt Kleinman, Dylan declared, “Johnnie Ray knocked me out. Johnnie Ray was the first person to actually really knock me out.” Asked about Ray’s special appeal, Dylan answered, “Well, he was just so emotional, wasn’t he? I ran into him in an elevator in Australia. He was like one of my idols, you know. I mean, I was speechless. There I was in an elevator with Johnnie Ray. I mean, what do you say, you know?” (Kleinman 822). Maybe he wasn’t entirely speechless. The following year Dylan told Cameron Crowe:

He was the first singer whose voice and style I totally fell in love with. There was just something about the way he sang, “If your sweetheart sends a letter” [from “Cry”] that just knocked me out. I loved his style, wanted to dress like him, too. […] I ran into him in the elevator in Sydney, Australia, late in ’78 and told him how he impressed me so when I was growing up. I still have a few of his records. (851-52)

Dylan described Ray as “my first pop hero” to Scott Cohen, adding, “People forget how good he was” (876). Note that Dylan’s interviews with Kleinman, Crowe, and Cohen all took place in 1984-85, meaning that his resurgence of interest in Ray coincided with his work on the album Empire Burlesque, whose title spotlights a world of gendered spectacle and performance.

“The Little White Cloud That Cried”

Dylan devotes a chapter of The Philosophy of Modern Song to Ray’s “The Little White Cloud That Cried.” He describes the song like a Wordworthian nature poem: “The little white cloud sheds tears, and bawls like a baby. You’ve heard its mournful lament, when walking down by the river, but you too had a heavy heart, so you were only half listening. You too were lonesome and dispirited” (99). As with much Romantic lyric poetry, nature functions as a mirror of the solitary poet’s innermost feelings. Dylan’s signature “you” voice in The Philosophy of Modern Song connects or conflates the singer’s experience with that of the listener. The little white cloud serves as a mirror for the crooner’s lonesome emotions, and the resulting song became a mirror for the inner turbulence of Bobby Zimmerman.

He told me he was very lonesome

And no one cared if he lived or died

And said sometimes the thunder and lightning

Make all little clouds hide

In a 1952 profile for the Saturday Evening Post, Ray reflected upon his inspiration for “The Little White Cloud That Cried.” Feeling particularly downhearted about the state of his life and career, he took a walk along the Umpqua River in his native Oregon. Ray recalled, “I just took every idea out of my mind, and sort of thought ‘Lord, you’ll have to take over from here. I just don’t know what to do next. I guess I’m licked.’” Looking up at a cloud in the sky, the song came to him complete: “It was all there. The title, the words, the tune” (qtd. Whiteside 44).

He said “Have faith in all kinds of weather

For the sun will always shine

Do your best and always remember

The dark clouds pass with time”

Dylan recaptures what he first heard upon encountering the song as an 11-year-old. He empathized with the crying cloud, but it also scared him: “This white cloud is so unhappy, but you don’t want to be dragged into its misery, if you sympathize too much, you could lose your senses” (99-100).

The kid isn’t comfortable with everything he sees in the mirror of this song. The cloud “has a message for the world, that we all must yield to love. It tells you to spread this information to the far corners of the earth. You’re not sure if you’re up to this task. You don’t want to say you won’t, but you don’t want to say you will either” (100, emphasis added).

The little white cloud’s message can be interpreted religiously, but I think Dylan implies a different kind of love here, the love that dare not speak its name during the closeted repression of fifties America. As an 11-year-old, Bobby Zimmerman was probably oblivious to any queer subtext in the song. But the 80-year-old author can see linings in this little white cloud that the little boy lost overlooked.

The lyrics never actually mention the word “love,” and certainly never say that “we all must yield to love.” If that is the message of the song, then it is communicated not through words but through the mournful lamentation in Ray’s emotional delivery. Even as an adolescent, Bobby Zimmerman must have intuited how much suffering went into the making of this song. He appreciated the singer’s sacrifice, even if he hadn’t yet made up his mind to give himself to music. Here again, the octogenarian author knows the complete commitment required to pull this feat off, and he knows the cost of opening your heart to the world and letting the world come in.

In the commentary section on “The Little White Cloud That Cried,” Dylan doesn’t mince words about the public reaction to Ray’s unique style: “A lot of people thought when they heard Johnnie Ray singing that he was a girl. Johnnie sang in his natural voice, which was anything but falsetto. A lot of people think male singers who sing in falsetto are actually females. Some of the Motown singers do have that quality. In Johnnie’s case, though, he just sounded like a girl” (101). In an era of strict enforcement policing the barrier between masculinity and femininity, Johnnie Ray was on the wrong side of the fence.

When Ray’s manager Danny Kessler first played the singer’s demo for Columbia Records executives, they were “just completely knocked out by this superstar I had found.” However, the sales force had marketing concerns: “almost in unison they said, ‘we don’t think she’s gonna make it.’ They all thought I was a pitching a girl who sounded like Dinah Washington! Finally, I convinced them that she was a boy, and then I had to break the news that she was a white boy. I know they all felt that I had lost my head completely” (qtd. Whiteside 63). Needless to say, the marketing apparatus of popular music would start singing a different tune a couple years later with the crossover success of Elvis Presley and the commercial appeal of early rock & roll.

Detractors disparaged Ray in highly gendered terms, calling his performance style “hysterical” and ridiculing him personally as a “sissy” or worse. But Dylan defends Ray as an inspirational role model, and he hears something much more poignant in Ray’s singing: “It is the voice of a damaged angel cast out to walk the streets of the dirty cities, singing and squealing, crying and cajoling, banging mic stands and piano stools” (101).

Looking back on his formative years, Dylan regards Ray as one of the early standard bearers for a musical and sexual revolution against the grey flannel conformity of the fifties: “He didn’t just wear his emotions on his sleeve, he carried them on a flag that he waved in the audience’s face” (101).

In his Rock & Roll Hall of Fame induction speech for Dylan, Bruce Springsteen famously asserted, “The way Elvis freed your body, Bob freed your mind.” Before either innovator arrived on the scene, Johnnie Ray freed listeners’ emotions. As Dylan writes in The Philosophy of Modern Song, “Johnnie’s records didn’t need crocodile tears, no false emotions. Johnnie just let his hair down. And we all cried” (102).

Works Cited

Cohen Scott. 1985 Spin Interview with Bob Dylan. Every Mind Polluting Word: Assorted Bob Dylan Utterances. Ed. Artur Jarosinski. Don’t Ya Tell Henry, 2006, pp. 874-84.

Crowe, Cameron. 1985 Biograph Interview with Bob Dylan. Every Mind Polluting Word: Assorted Bob Dylan Utterances. Ed. Artur Jarosinski. Don’t Ya Tell Henry, 2006, pp. 851-69.

Dylan, Bob. The Philosophy of Modern Song. Simon & Schuster, 2022.

Kleinman, Bert. 1984 Westwood One Radio Interview with Bob Dylan. Every Mind Polluting Word: Assorted Bob Dylan Utterances. Ed. Artur Jarosinski. Don’t Ya Tell Henry, 2006, pp. 818-30.

Ray, Johnnie. “The Little White Cloud That Cried.” Columbia Records, 1952.

Springsteen, Bruce. Induction Speech for Bob Dylan. Rock & Roll Hall of Fame Ceremony (20 January 1988).

Whiteside, Jonny. Cry: The Johnnie Ray Story. Barricade Books, 1994.

Graley this is a fantastic piece! I too wish I could be in Denmark with my favorite Dylan minds.

I loved this and I am thrilled that I will get to hear the rest in Odense.