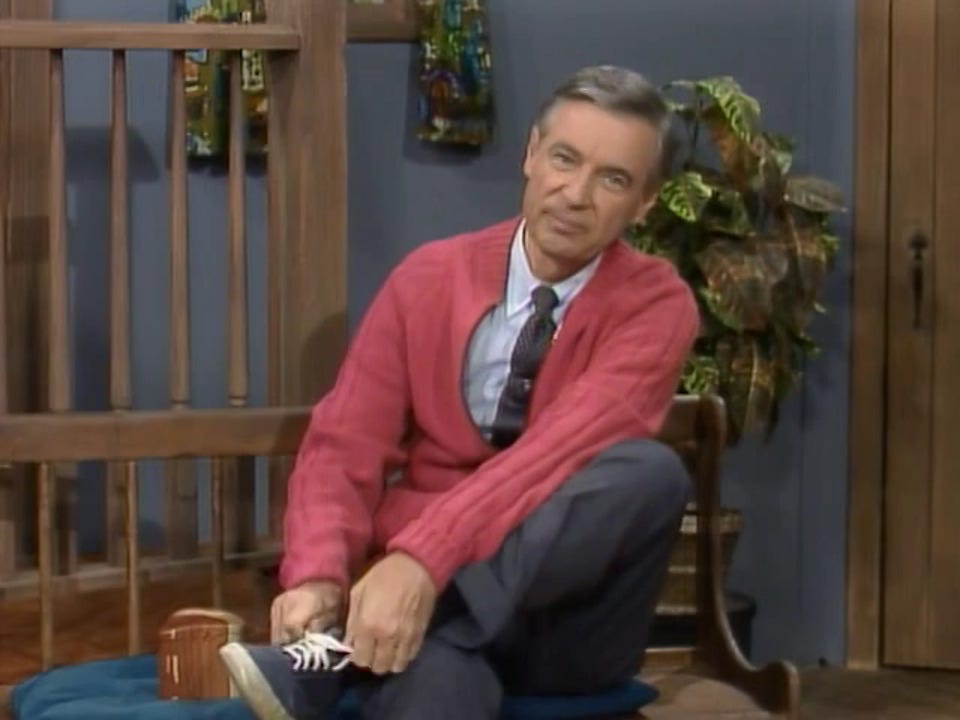

It’s a beautiful day in this neighborhood

A beautiful day for a neighbor

Would you be mine?

Could you be mine?

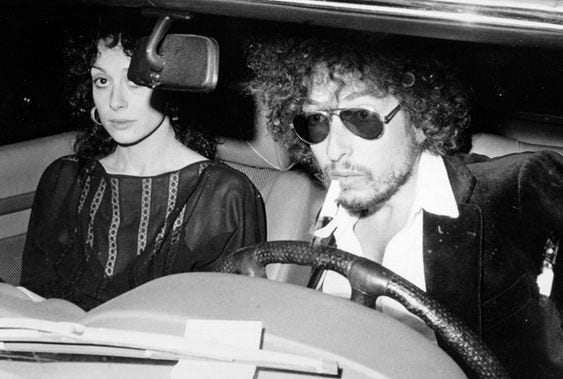

Time to tie our shoestrings, button our coats, and take another virtual trip together to the Cincinnati Art Museum, with Dylan always on our minds, our ears open to conversations among the artworks, and our eyes fixed upon the gaze. Inspired by Ray Padgett’s piece about Dylan’s 1974 trip to The Phillips Collection in Washington, D.C., the first installment considered three works—Moses Jacob Ezekiel’s Eve Hearing the Voice, Ferdinand Hodler’s The Sacred Hour, and Karen LaMonte’s Seated Dress with Impression of Drapery—each related to the tradition of displaying women’s bodies as objects of the male gaze.

For this second installment, we’re still considering works that incorporate their looked-at-ness into the experience, but we’re shifting our perspective. The three pieces we’ll ponder here all depict subjects caught in the act of looking at someone or something. The artists who created these works—William Merritt Chase, Grant Wood, and Elizabeth Catlett—each have instructive things to show us about looking: what we see, how we see it, and what we miss or misperceive, depending upon our vantage point. This instructional dimension is no accident, since all three of these artists were also revered art teachers. Let’s look at their work, do a little homework, and see what we can learn from them.

Summer at Shinnecock Hills by William Merritt Chase

Every time I visit the Cincinnati Art Museum, I stand before this painting and lose myself in it for a while. It seems to tell a story. A woman stands in a field, looking back toward the horizon. One house clearly stands out in the center distance. No matter how many times I’ve stared at this painting, I’m never entirely sure if the other blobs in the distance are houses or conveyances. Chase’s blurry impressionist style makes it impossible to say for sure. The one on the far left could be a pointy roofed A-frame house, or it might be a ship in Shinnecock Bay:

The one on the far right could be a ranch house with smoke billowing out of its chimney, or it might be a steam locomotive chugging down the old Long Island Railroad line:

The sense of travel, specifically of leaving, is crucial to the painting’s appeal. As I imagine it, the woman in the foreground is running away from home, leaving her old life behind. Chase paints a stream separating her from home, suggesting that she made her way to the other side of a liminal threshold and is bound for a new reality. She has crossed her Rubicon.

We cannot see her face. We’re positioned to look at her as she glances over her shoulder for one last glimpse. This is not some cautionary tale about the danger of looking back, as in the Orpheus and Eurydice myth or the biblical story of Lot’s wife. To me, this painting captures the thrill of escape. She looks back, not out of regret or fear, but to reassure herself that it’s finally real this time. After imagining it a thousand times, she’s finally doing it. She is free.

As I watch her gazing across that sparkling blue water, I hear echoes of Dylan’s “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue”: “Leave your stepping stones behind, something calls for you / Forget the dead you’ve left, they will not follow you.” One last look, then full steam ahead.

But you know who else drifts into my mind as I look at this painting? Sara Dylan.

The Dylans kept a summer home in the Hamptons on Lily Pond Lane, just about fifteen miles from Shinnecock Hills. This summer retreat serves as the setting for Dylan’s desperate plea for reconciliation in the song “Sara.” He begs her: “Don’t ever leave me, don’t ever go.” At other stages in their on-again, off-again breakup, however, he recognizes that she has already made the essential split that will extricate her from the marriage. She has already crossed over. In “If You See Her, Say Hello,” he concedes, “I always have respected her / For doing what she did and getting free.”

Needless to say, I know nothing about the real Sara Dylan. Neither do you. She has maintained her anonymity and silence astoundingly well for decades. All we know is Dylan’s perspective, as refracted through the prism of art, in several memorable songs written almost fifty years ago.

As I see it, Chase’s painting looks at the experience of “doing what she did and getting free” from the woman’s perspective. We observe her gazing at the home she leaves behind on Shinnecock Hills. As I hear it, Dylan gives us the other side of the experience in “Sara,” that of the man left behind, gazing morosely at pictures in the family photo album and bawling his eyes out, holed up in a lonesome beach house just up the Long Island shore. The woman in Chase’s painting may look like a figure out of Little House on the Prairie, but in my imagination, she will always be an amalgamation of Baby Blue and Sara Dylan.

I’ve learned a lot about the circumstances behind this painting from art historians Cynthia V. A. Schaffner and Lori Zabar. Chase created many paintings in this distinct landscape as head tutor at an art school in Shinnecock Hills. Schaffner and Zabar explain:

In the summer of 1890, Janet Ralston Chase Hoyt (1847-1925) invited William Merritt Chase (1849-1916) to be the director of a summer school for plein painting she was planning in the nascent resort community of Shinnecock Hills, on the South Fork of Long Island, New York. As one of the first summer residents of the adjacent summer colony of Southampton, Janet Hoyt was uniquely positioned to establish what would become the most famous, popular, and influential summer outdoor painting school in America: the Shinnecock Hills Summer School of Art (1891-1902). (303)

The chief organizer of the school, Janet Hoyt, was an illustrator, needleworker, and philanthropist. She was daughter of former Chief Justice of the Supreme Court Salmon P. Chase. And oh yeah—she was born in Cincinnati. The term “plein painting” refers to setting up your easel outdoors and painting a landscape while situated within it. The school opened in 1891, the same year Chase painted Summer at Shinnecock Hills.

If the landscape looks familiar, you may have seen it on television during a golf tournament. Shinnecock Hills Golf Club is one of the most distinctly recognizable courses in America and has hosted the U.S. Open multiple times. The course opened in 1891, the same year as its neighbor the Shinnecock Hills Summer School of Art.

Schaffner and Zabar include a representative painting by one of Chase’s summer school students, Ella Shophonisba Hergesheimer, to illustrate his aesthetic influence (318):

Notice how this painting shares the same landscape, palette, brushwork, and style as Professor Chase’s canvas. Also notice how students incorporate each other as subjects within their work. That’s probably one of Chase’s students depicted in Summer at Shinnecock Hills.

Chase exerted his influence over American art not only as a painter but also as a teacher. More than a thousand students enrolled in his summer school during its twelve years of existence, and several became established artists. “Many of Chase’s summer school students went on to teach art, spreading Chase’s teaching methods and style throughout America” (Schaffner and Zabar 318).

I also discovered another fascinating connection involving Chase. After his experiences at Shinnecock Hills, he was inspired to found his own art school in Greenwich Village. The Chase School opened in 1896. Today it is called Parsons School of Design, or simply Parsons. In 1902, Chase hired another highly respected artist and teacher, Robert Henri, to join the faculty.

Henri hailed from Cincinnati (of course!) and had a friendly relationship with Chase at first. However, the two strong-willed men gradually began to clash over artistic tastes, subject matter, and pedagogical approach, leading to a fierce rivalry. By 1907, Chase was so fed up with Henri that he quit his own school rather than work any longer with his bitter enemy.

Here’s the cool connection. One of Henri’s star pupils was Norman Raeben:

Readers of Shadow Chasing probably recognize Norman Raeben as Bob Dylan’s art teacher. In the spring of 1974, Dylan took intensive painting classes taught by Raeben in his eleventh-floor studio at Carnegie Hall. In a 1978 interview with Pete Oppel, Dylan recalled, “Five days a week I used to go up there, and I’d just think about it the other two days. I used to be there from eight o’clock to four. That’s all I did for two months.” Dylan looked up to Raeben as more than a teacher. “I had met magicians, but this guy is more powerful than any magician I’ve ever met. He looked into you and told you what you were.” In his 1978 Rolling Stone interview, Dylan told Jonathan Cott that Raeben “taught me how to see.” He also credited the art teacher/magician with training him how to write songs again: “He put my mind and my hand and my eye together, in a way that allowed me to do consciously what I unconsciously felt” (all quotes from Cartwright 86-87).

Unfortunately, even as the teacher guided the songwriter back to artistic inspiration, Dylan believed that Raeben’s influence drove a wedge between him and Sara. He told Oppel: “It changed me. I went home after that and my wife never did understand me ever since that day. That’s when our marriage started breaking up. She never knew what I was talking about, what I was thinking about, and I couldn’t possibly explain it” (qtd. Cartwright 86).

Hmmm. So maybe I had it backwards. Maybe I should see the figure in Chase’s painting as an avatar for Dylan, walking toward his art and away from his home, looking back one last time before striking another match and starting anew.

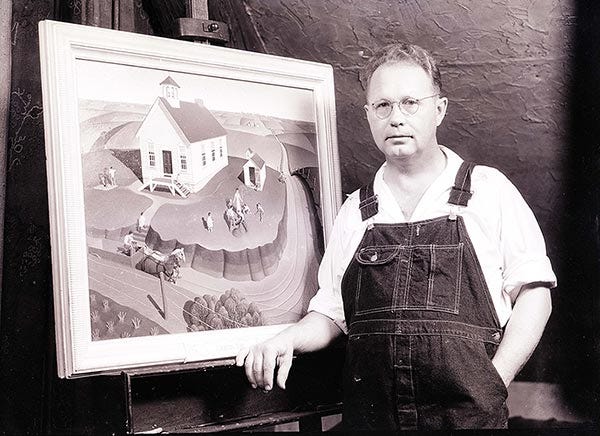

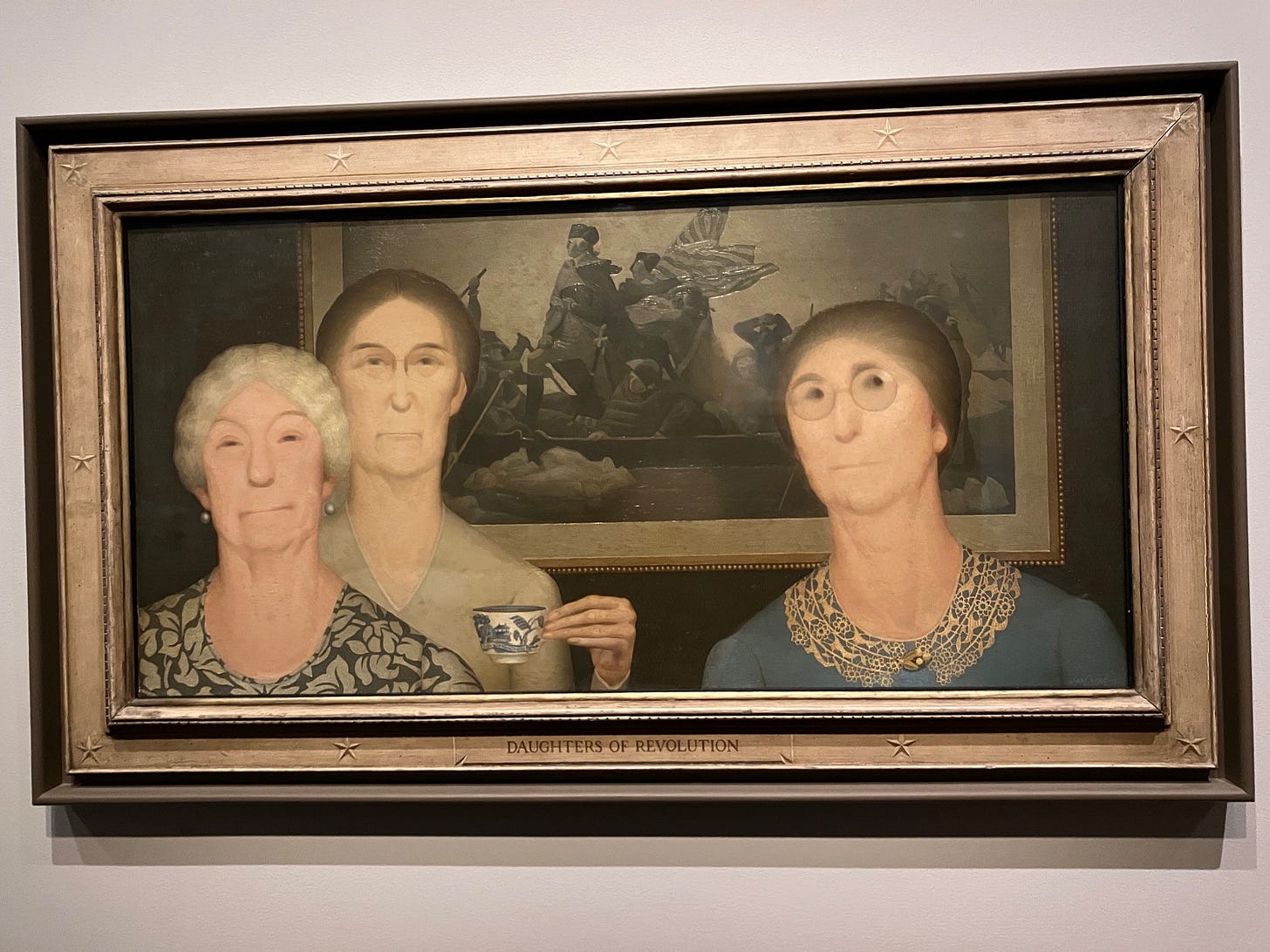

Daughters of Revolution by Grant Wood

Grant Wood painted American Gothic, one of the most iconic images in 20th century American art. If you’ve seen that painting, then you’ll immediately recognize Wood’s signature style on display in Daughters of Revolution, painted two years later and one of the Cincinnati Art Museum’s prized possessions. There’s an interesting story behind this painting. In 1928, Wood was commissioned to produce a Veterans Memorial Window in Cedar Rapids in his home state of Iowa. The Daughters of the American Revolution publicly challenged Wood’s patriotism because he used German materials to produce his memorial for American soldiers. Daughters of Revolution serves as the artist’s satirical response to the DAR.

The contrast with Chase’s painting couldn’t be starker. We go from a woman looking away from us to three women staring directly at us.

They look primly severe and supremely unimpressed. The perceptual tables have been turned. The spectator becomes the object of the gaze, fixed in the withering stares of these smug crones. As Wood’s biographer Tripp Evans sees it, “Apparently interrupted at a tea, the women regard the viewer with a look of undisguised contempt.” He adds, “With their tightened lips, beaky noses, and thick, elongated necks, the women resemble nothing so much as a puffed-up group of hens. Indeed, the central figure’s bony hand recalls a chicken’s talon” (Evans 156).

This painting reminds me of the verse from “It’s Alright, Ma (I’m Only Bleeding)” about the self-appointed gatekeepers of puritanical morality: “Old lady judges watch people in pairs / Limited in sex, they dare / To push fake morals, insult and stare.” Sounds like a spot-on description of Daughters of Revolution. I’m also reminded of the satirical tone of “With God on Our Side,” skewering the hubris and cultural chauvinism of American nationalists who presume that the United States is God’s favorite country and so he’s always on our side. Wood paints the women at their hoity-toity tea party in a similar light.

I also like Wood’s incorporation of Washington Crossing the Delaware, the famous patriotic painting by Emanuel Leutze. It lends a delicious meta-artistic effect to the experience of standing before Wood’s painting. Here are these Daughters of the American Revolution, standing beside one of the most enduring images from the Revolutionary War; but rather than looking at Washington, they are preoccupied with giving us the evil eye.

The museum label points out that another function of the painting-within-the-painting is to call out the DAR’s hypocrisy:

The colonial teas hosted by the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) every year on Washington’s Birthday, and the festivities in 1932 that marked the bicentennial of the first president’s birth, inspired Wood’s clever exposé of patriotism taken to extremes. Wood played on the foreign origins of all we deem ‘American’ (which includes, of course, our own ancestry). Behind the three smug women is an engraving of Washington Crossing the Delaware, a hallowed national icon painted in Dusseldorf, Germany by Emanuel Leutze, a German native who grew up in Philadelphia. The teacup is an example of Blue Willow china, which is decorated with Chinese-inspired motifs.

Here’s another cool touch. Check out the engraved frame Wood made for this canvas:

Wood removes the word “American” from the painting’s title, hoisting the DAR upon its own petard. He denies the group its claim to privileged status, much as they routinely challenged the patriotism of others as un-American, or less American, than these Boston Brahmins.

Grant Wood is often classified as one of the preeminent purveyors of American Regionalism in the 1930s. However, Erika Doss views his work from a very different perspective in “Grant Wood’s Queer Parody: American Humor During the Great Depression.” Doss applies “queer” here broadly to mean “an oppositional perspective, a subversive operation aimed at destabilizing controlling ideas and attitudes and imagining different ways of thinking and acting” (3-4). According to Doss, “Much of Wood’s playful, parodic body of art […] was grounded in a queer sensibility of resistance to mainstream, or heteronormative, understandings of historical tales, cultural subjects, and social standards” (4).

Drawing on Susan Sontag’s groundbreaking essay “Notes on Camp” (1964), Doss finds a camp sensibility at play in Wood’s queer parodies: “Using camp tropes to highlight the artificial, or constructed, terms of self and national identity in America, Wood’s humor-inflected paintings aimed at educating Americans about the fundamentally invented terms of their character and history” (4). Doss interprets American Gothic (1930), Midnight Ride of Paul Revere (1931), Daughters of Revolution (1932), and Parson Weems’ Fable (1939) as humorous yet deeply subversive works designed “to stimulate audience recognition of the artifice at the core of American myth-making” (32).

Wood’s queer parody of American myth-making sounds to me a helluvalot like Dylan’s artistic sensibilities in songs like “Talkin’ John Birch Society Paranoid Blues,” “Talkin’ World War III Blues,” “With God on Our Side,” “Bob Dylan’s 115th Dream,” “Tombstone Blues,” “Highway 61 Revisited,” and countless other examples. Get to work, Dylanologists! We can get a lot of mileage out of this concept of queer parody. That’s as a good a definition as any for Dylan’s signature combination of spoof, hyperbole, sarcasm, and biting social critique. I never anticipated that a museum trip and some follow-up research would uncover such a useful interpretive lens for seeing Dylan’s songs in a revealing new light.

Phillis Wheatley by Elizabeth Catlett

Be careful while backing up to get a better view of Grant Wood’s Daughters of the Revolution. You just might bump into the bronze bust of Phillis Wheatley by Elizabeth Catlett.

The placement is no accident. Elizabeth Catlett was a student of Grant Wood. After her graduation from Howard University, she enrolled in graduate school at the University of Iowa in hopes of studying with Wood. She told biographer Melanie Herzog about her first encounter with him. The DAR was still on his mind:

The first thing he said to me, I guess it was to make me feel at home, was “Miss Catlett, I was so annoyed with the Daughters of the American Revolution when they wouldn’t let Marian Anderson sing at Constitution Hall,” with his little soft voice. And I thought, why is he telling me that? He wants me to know that he’s not racially prejudiced. (qtd. Herzog 19)

According to Herzog, “What she learned from Grant Wood about his disciplined, methodical process of working and reworking an image has remained vital to her own approach, as has his encouragement, reinforced by his own example, to take as her subject what she knew best” (19).

The placement of Phillis Wheatley beside Daughters of Revolution is doubly interesting because it seems as if the judgmental women in Wood’s painting are looking dismissively at Catlett’s bust. This disdainful regard is consistent with the blue-blooded ideology of the DAR, which regarded those with pedigrees dating back to the founding of the nation as a superior class, an American aristocracy—so long as they arrived on the right ship. Phillis Wheatley landed in Massachusetts in 1761, fifteen years before the signing of the Declaration of Independence. But she crossed the Atlantic in bondage on a slave ship, abducted from her home at the age of seven, and sold as a slave to John and Susanna Wheatley in Boston.

The juxtaposition of these two artworks is striking. The self-important upholders of white American nobility gaze upon a Black slave, a woman who overcame her dehumanization to become the first published African American poet. The sightlines set up by the curators are provocative. The DAR women stare in the direction of Phillis Wheatley, but she doesn’t return their gaze. They only get her profile—talk to the hand! (You kind of wish she had raised a different finger toward them, don’t you?)

Wheatley’s gaze is mesmerizing. The figures in Wood’s painting seem like kitschy caricatures next to Catlett’s forthright portrayal of strength, confidence, and serene determination. I’m reminded of something Dylan says in the documentary No Direction Home: “All the great performers I’d seen, all of those I wanted to be like, they had something in common. It was in their eyes. It said ‘I know something that you don’t know.’ I wanted to be that kind of performer.” Phillis Wheatley has got the look. She’s the kind of artist Dylan wants to be.

The contrast set up by the curators between the DAR women and Phillis Wheatley reminds me of a contrast Dylan sets up in “Caribbean Wind.” The song features an entangling relationship between a white American man and a Black Haitian woman. The refrain draws attention to the different fates that awaited their ancestors when they crossed over to the New World: one seeking the land of opportunity, the other shackled in the chains of slavery.

And them Caribbean winds still blow from Nassau to Mexico

Fanning the flames in the furnace of desire

And them distant ships of liberty on them iron waves so bold and free

Bringing everything that’s near to me nearer to the fire

Elizabeth Catlett’s own background resonates strongly with Dylan’s refrain. The African American sculptor was the granddaughter of slaves, and she lived most of her adult life in Mexico. She first traveled south of the border on a grant in 1946. She ended up moving down there and working with Taller de Gráfica Popular (TGP), a graphics workshop dedicated to social activism and leftist causes. Because of TGP’s ties to Communism, Catlett was targeted for investigation by the notorious House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) and the U.S. Embassy in Mexico. In 1955, she was ordered to submit her political affiliations and name people she knew or suspected were Communists. As Lisa Farrington explains in Creating Their Own Image: The History of African-American Women Artists,

Catlett refused to comply with the mandate and was, in due course, imprisoned as a “foreign agitator” by Mexican authorities in collusion with the HUAC. In protest, Catlett made the radical decision to renounce her American citizenship upon her release from prison. In 1962, she became a citizen of Mexico, at which time the U.S. government promptly declared her an “undesirable alien” and for the next ten years prohibited her from returning home. (124-25)

In separate but kindred ways, both Wheatley and Catlett were separated from their native lands but nevertheless found the courage and inspiration necessary to thrive. In 1958, Catlett became the first woman professor at the National University of Mexico’s School of Fine Arts. The following year she was named chair of the department, a position she held until her retirement in 1976. As she told her protégé Samella Lewis, “I know very well that, if I had continued to live in the United States, I would not have developed as I did. If I had been able to look ahead and see what would happen in my life by staying in Mexico, I would have done the very same thing. I have enjoyed life in Mexico” (qtd. Lewis 23).

As an artist, teacher, and social activist, Catlett was committed to positive treatments of Black women. She saw her work as part of a countertradition to the dominant male tradition (mostly white) of objectifying female bodies (mostly white). “Many artists are always doing men. I think that somebody ought to do women. Artists do work with women, with the beauty of their bodies and the refinement of middle-class women, but I think there is a need to express something about the working-class Black woman and that’s what I do” (qtd. Lewis 102).

Phillis Wheatley (1973) is a perfect example. Melanie Herzog explains the motivation behind this sculpture: “To commemorate the 200th anniversary of the 1773 publication of Phillis Wheatley’s Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral (the first book published by an African American), poet Margaret Walker and Jackson State College in Mississippi commissioned Catlett in 1973 to create a life-size bronze bust of Wheatley.” The bust “is based on the only known contemporary portrait of the poet, the engraving by Scipio Moorhead that appeared in Wheatley’s book” (Herzog 155).

The theme of this post is “Looking.” Margaret Walker’s conference and Elizabeth Catlett’s bust were both efforts to take a fresh look at Phillis Wheatley, a figure who had been largely unseen or misperceived for two centuries. I want to spend the rest of this post taking a deeper look at Phillis Wheatley. She provides an ideal case study in what gets seen, what gets overlooked, and what gets distorted or occluded depending upon the perspective from which we view art. My first guide for this second look has been Catlett’s bust, but my second guide is Henry Louis Gates’s The Trials of Phillis Wheatley.

This slim volume is an expanded version of the Thomas Jefferson Lecture in the Humanities, delivered by Gates at the Library of Congress in March 2002. The operative word in Gates’s title is “trials.” He frames his lecture as an examination of various trials Phillis Wheatley endured during her lifetime and afterwards in terms of her literary legacy. Each of these trials challenged the poet’s legitimacy and authenticity.

The first trial was convened by John Wheatley in October 1772. He owned a young slave named Phillis who had written a collection of poems that he wished to publish. However, he was having difficulty raising funds for publication because of the widespread prejudice that she could not possibly have written this poetry on her own. The slaveowner put together a group of eighteen esteemed white men from Boston (the majority of them fellow slaveowners) to test her intelligence and veracity and to authenticate the poems. As Gates puts it, “The panel had been assembled to verify the authorship of her poems and to answer a much larger question: was a Negro capable of producing literature?” (5).

Before arriving in Boston, Phillis was stolen from her home on the Senegambian coast of Africa, transported across the Atlantic to the Massachusetts Bay Colony, and purchased by John and Susanna Wheatley in July 1761. She was named after the schooner Phillis—the slave ship that brought her to America (Gates 16-18).

No transcript of Wheatley’s tribunal survives, but we know that she passed her test because all eighteen of her judges signed a sworn statement that read:

We whose Names are under-written, do assure the World, that the Poems specified in the following Page, were (as we verily believe) written by Phillis, a young Negro Girl, who was but a few Years since, brought an uncultivated Barbarian from Africa, and has ever since been, and now is, under the Disadvantage of serving as a Slave in a Family in this Town. She has been examined by some of the best Judges, and is thought qualified to write them. (qtd. Gates 29-30)

On the strength of this dubious authentication (“Barbarian”??), Wheatley was able to release Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral in 1773, the first published volume of poetry by an African American writer. For a short time, she became something of a literary sensation. The Wheatleys took her to England on a book tour, where she was celebrated but her American owners were denounced. As Gates notes, British critics “condemned the hypocrisy of a colony that insisted on liberty and equality when it came to its relationship to England but did not extend those principles to its own population” (35). A month after the book’s publication, the Wheatleys returned to Boston and freed Phillis.

Gates’s subtitle refers to “encounters with the founding fathers.” He examines four such encounters with Benjamin Franklin, John Hancock, George Washington, and Thomas Jefferson. The best by far was with Washington. Phillis wrote a poem in his praise, “His Excellency George Washington,” and mailed it to him in October 1775. Her panegyric concludes:

Proceed, great chief, with virtue on thy side,

Thy ev’ry action let the goddess guide.

A crown, a mansion, and a throne that shine,

With gold unfading, WASHINGTON! be thine.

Washington replied with admiration and appreciation in February 1776 and invited the young poet to visit him at his headquarters in Cambridge, across the Charles River from Boston. The following month, she took him up on the offer, spending a pleasant half hour with the commander-in-chief, future first president, and namesake for Elizabeth Catlett’s hometown. Note that this encounter between Phillis Wheatley and George Washington took place the same year as his famous crossing of the Delaware River on Christmas 1776, the very scene depicted in the background of Wood’s Daughters of Revolution.

Phillis Wheatley’s encounter with Thomas Jefferson was much more contentious. Below is a statue you may have seen before of the third President of the United States. It stands outside the Rotunda on the campus of the University of Virginia, founded by Jefferson in 1819. But you probably didn’t know that the sculptor was Moses Ezekiel, the same artist (and former Confederate soldier) who made Eve Hearing the Voice, which we studied in the first installment.

Jefferson and Wheatley never met in person, but he was on record as totally dismissive of her poetry. I probably don’t have to tell you that the lead author of the Declaration of Independence was highly selective in applying the self-evident truth “that all men are created equal.” For instance, look at Jefferson’s condescending comments, not only on Phillis Wheatley’s poems, but on the incapacity of any Black person to produce true art:

Misery is often the parent of the most affecting touches in poetry. Among the blacks is misery enough, God knows, but not poetry. Love is the peculiar oestrum of the poet. Their love is ardent, but it kindles the senses only, not the imagination. Religion, indeed, has produced a Phillis Whatley [sic]; but it could not produce a poet. (qtd. Gates 44)

Gates manages to be remarkably restrained in responding to Jefferson’s galling white supremacy. Of course, remember that he was delivering the Thomas Jefferson Lecture in the Humanities at the time. He observes,

Jefferson was quite convinced that Wheatley’s finer sentiments, such as her piety, are quite separate from the “love” needed to write poetry. What Jefferson meant is quite simple. He believed that Africans have human souls, they merely lack the intellectual endowments of other races. (44)

In other words, Jefferson’s encounter with Phillis constituted another “trial,” one with a split decision: she passed his test as a human being with a soul worth saving, but failed his test as a poet with a literary imagination worth reading.

When white supremacists gathered around Jefferson’s statue during the 2017 Unite the Right rally, I’m not sure if that was a calculated move to embrace the Founding Father as an icon or just a convenient gathering place on campus. For all his democratic aspirations and inspirational rhetoric about equality, there are many troubling elements of white supremacy that taint Jefferson’s legacy, and this bias is evident in his views of Phillis Wheatley’s poetry. [Footnote: the racists at the rally chanting “Jews will not replace us!” were ignorant about many things, among them the fact that Jefferson’s statue was made by a Jewish artist.]

The trials of Phillis Wheatley didn’t end with her death. In contrast to the white supremacist critique of Jefferson, her posthumous legacy has most often been challenged by a jury of African American peers. Exhibit A for the prosecution is her poem “On Being Brought from Africa to America”:

’Twas mercy brought me from my Pagan land,

Taught my benighted soul to understand

That there’s a God, that there’s a Saviour too:

Once I redemption neither sought nor knew.

Some view our sable race with scornful eye,

“Their coulour is a diabolic die,”

Remember, Christians, Negros, black as Cain,

May be refin’d, and join th’angelic train.

Henry Louis Gates is frank in his assessment: “This, it can be safely said, has been the most reviled poem in African-American literature. To speak in such glowing terms about the ‘mercy’ manifested by the slave trade was not exactly going to endear Miss Wheatley to black power advocates in the 1960s” (71).

Gates cites numerous examples of withering criticism of Phillis Wheatley from Black artists and intellectuals. In the 1920s during the Harlem Renaissance, James Weldon Johnson wrote of her “smug contentment,” and Wallace Thurman called her “a third-rate imitation of Alexander Pope.” In the 1960s during the Black Arts Movement, Amiri Baraka claimed that her “pleasant imitations of eighteenth-century English poetry are far and, finally, ludicrous departures from the huge black voices that splintered southern nights with their hollers, chants, arwhoolies, and ballits” (qtd. Gates 75-76).

Even though the identities and ideologies of Wheatley’s detractors were sharply different in the 18th and 20th centuries, the trials still hinged upon contested claims about her legitimacy and authenticity. As Gaines astutely observes,

It’s clear enough what we’re witnessing. The Jeffersonian critique has been recuperated and recycled by successive generations of black writers and critics. Too black to be taken seriously by white critics in the eighteenth century, Wheatley was now considered too white to interest black critics in the twentieth. […] Jefferson and Amiri Baraka, two figures in American letters who would agree on little else, could agree on the terms of their indictment of Phillis Wheatley. (82-83)

I think Elizabeth Catlett’s bust is an attempt to defend the maligned poet’s legitimacy, redeem her tarnished legacy, and overturn the previous convictions—first by white supremacist judges, and later by a jury of Black cultural nationalists—in the trials of Phillis Wheatley. The sculptor/instructor teaches us how to take a second look and see a sister artist through fresh eyes.

Works Cited

Cartwright, Bert. “The Mysterious Norman Raeben.” Wanted Man: In Search of Bob Dylan. Ed. John Bauldie. Citadel Press, 1991. 85-90.

Catlett, Elizabeth. Phillis Wheatley. Bronze, 22 x 12 ¾ x 14 inches, 1973. Cincinnati Art Museum.

Chase, William Merritt. Summer at Shinnecock Hills. Oil on canvas, 26.4 x 32.5 inches, 1891. Cincinnati Art Museum.

Doss, Erika. “Grant Wood’s Queer Parody: American Humor During the Great Depression.” Winterhur Portfolio 52.1 (2018): 3-45.

Dylan, Bob. Official Song Lyrics. The Official Bob Dylan Website.

https://www.bobdylan.com/.

Evans, R. Tripp. Grant Wood: A Life. Knopf, 2010.

Farrington, Lisa E. Creating Their Own Image: The History of African-American Women Artists. Oxford University Press, 2005.

Gates, Jr., Henry Louis. The Trials of Phillis Wheatley: America’s First Black Poet and Her Encounters with the Founding Fathers. Basic Civitas Books, 2003.

Herzog, Melanie Anne. Elizabeth Catlett: An American Artist in Mexico. University of Washington Press, 2000.

Lewis, Samella. The Art of Elizabeth Catlett. Handcraft Studios, 1984.

Padgett, Ray. “Exit Through the Gift Shop.” Flagging Down the Double E’s (16 January 2024),

.

Schaffner, Cynthia V. A. and Lori Zabar. “The Founding and Design of William Merritt Chase’s Shinnecock Hills Summer School of Art and the Art Village.” Winterhur Portfolio 44.4 (2010): 303-50.

Wood, Grant. Daughters of Revolution. Oil on masonite, 20 x 39.9 inches, 1932. Cincinnati Art Museum.

Graley - I continue to be so impressed and not a little jealous at your ability to find and gather disparate threads from Grant Wood to Sara Dylan to Thomas Jefferson to Phillis Wheatley into a a complete piece that completely makes sense. So happy I started my Presidents Day reading with this. On to the next Dylan and Cincinnati piece.

The first segment on Merritt’s painting had me all emotional, and got me thinking about Dylan’s songs about leaving and being left. I think what makes songs like If You See Her Say Hello and Sara so rough to listen to is that Dylan is so famously un-nostalgic, and usually quick to move on, both from situations and people (I think it's a Gemini thing). But these songs are the heartbreaking document of exceptions to the rule. We can hear Dylan struggling with something that usually comes easy to him.

Maybe when he sings that he "respects" her for "getting free", he's also secretly envying her for finding it so easy to leave. This train of thought has also just given me a new perspective on one of my favourite songs, “Abandoned Love”: I always took the singer at face value (MY BAD), thinking that he’s looking to have one last night with his lover before he’s able to sever the ties for good. “Let me feel your love one more time before I abandon it”. But now I’m ready to call his bluff, because – does it ever work like this? How many smokers have sworn that the next will be their last cigarette, and then said the same before the next and the one after that? So while the singer is undoubtedly looking to quit, he also needs another fix first (a shot of love if you will). In fact we know that we can’t really take him at his word, because throughout the song he emphasises the power she has over him, begging her to turn him loose, to cross him off her list, to descend from her throne, and it’s only in the very last line that he pretends like he has the power to quit her, but of course he doesn’t. The love is all but abandoned!

Incidentally, "Abandoned Love" is also a long with a lot of looking: “I can see the turning of the key”, “I see you in the streets, I begin to swoon” (he’s down bad!), “I love to see you dress before the mirror” (double looking!), kissing in the theatre (not looking at the screen), and the request that she get all dolled up for his gaze.

I just love your writing, Graley, thank you for this beautiful piece! I so appreciated learning about these paintings, their artists and their histories, and to find out more about Phillis Wheatley.