Dylan Duets

Gillian Welch & David Rawlings's Woodland

On November 21, 2024, I attended a transcendent performance by Gillian Welch & Dave Rawlings at Cincinnati’s Taft Theatre. Readers may recall that this is the same venue where Bob Dylan played his first concert in the city back in March 1965. Being in the Taft always conjures up his spirit for me, and I wasn’t the only one present with Dylan on their mind.

As I listened to the duo deliver moving renditions from their new album Woodland, I started to hear lots of echoes. In the month since the concert, I’ve immersed myself in this record and am convinced that Welch & Rawlings are engaged in a musical dialogue with the folk tradition, and with Dylan in particular. Woodland has motivated me to start a new series for Shadow Chasing called “Dylan Duets.”

I’m not talking about songs where Dylan sings with a partner, though that’s certainly an interesting topic. For excellent examples of that approach, listen to Laura Tenschert’s tribute to Clydie King on Definitely Dylan, and Ray Padgett’s deep dive on all of Dylan’s duets with Joan Baez on Flagging Down the Double E’s. Rather, I’m interested in setting up intertextual duets.

Dylan is a walking encyclopedia of music and draws freely upon traditional songs for inspiration. Now in his seventh decade of making music, he has added hundreds of his own songs to that tradition, songs which have in turn inspired countless others. In “Dylan Duets” I will choose examples of such cross-pollination, take these hybrid songs into my laboratory, and perform a kind of musical gene-sequencing. If that metaphor is too clumsy, then try this one: I want to put Dylan’s songs in conversation with others he influenced and listen to what they say to each other.

Let’s kick off “Dylan Duets” with Woodland. I was initially just going to write about “Here Stands a Woman,” which is a brilliant multi-layered answer song to “Just Like a Woman.” But the more I wandered down the pathways of Woodland, the more footprints I found leading back to Dylan. “Empty Trainload of Sky,” “Lawman,” “North Country,” “Hashtag,” and “The Day the Mississippi Died” also make for interesting intertextual duets around the Shadow Chasing campfire. Come gather round, friends, and I’ll tell you a tale.

Background

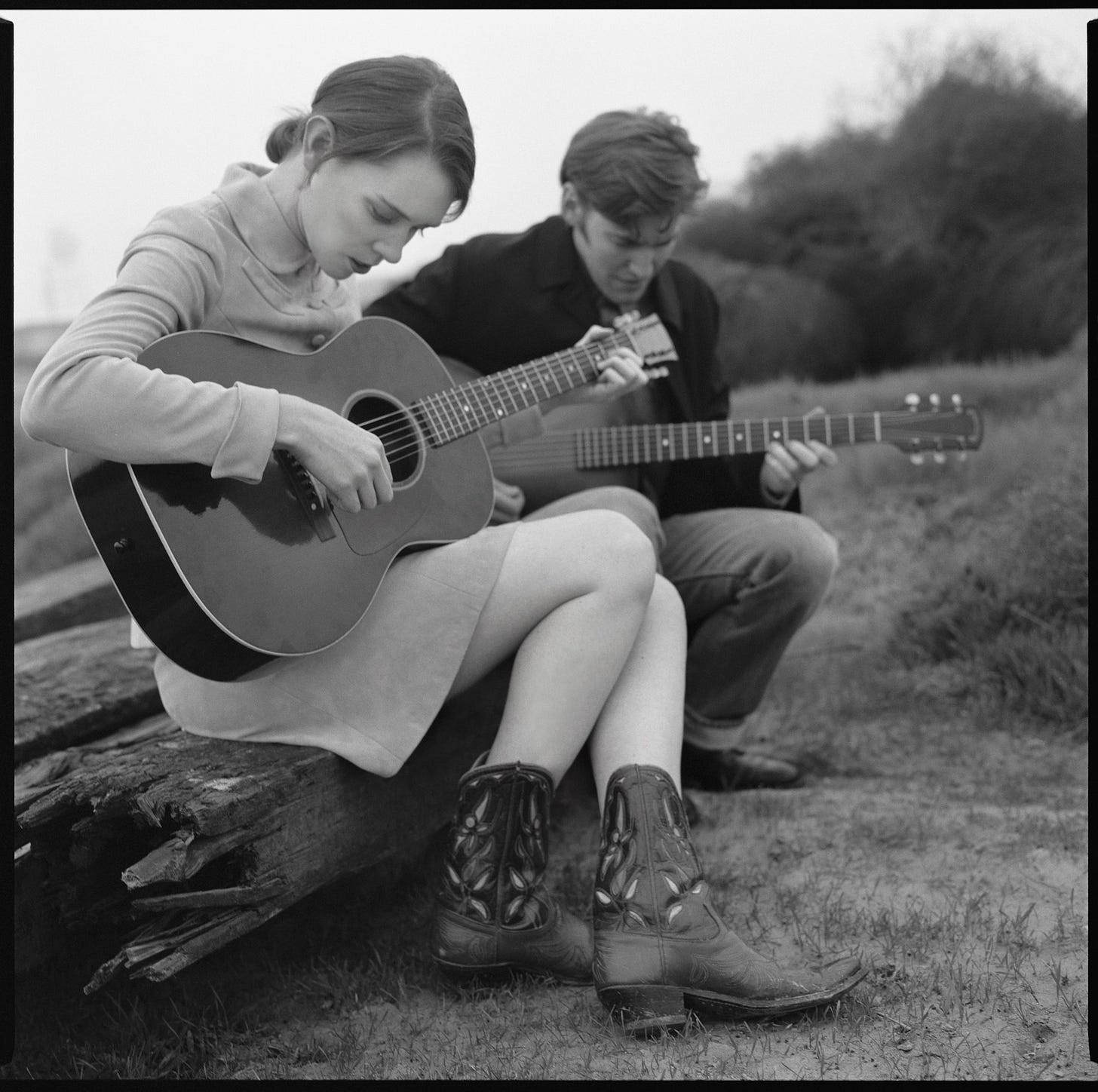

If you are a Dylan fan, then you’re probably already familiar with Welch & Rawlings. But for those readers who might not know their work yet, let me fill in some background. Gillian Welch was born in New York City and raised in Los Angeles. She graduated from UC Santa Cruz with a degree in photography, and she attended Berklee College of Music in Boston, where she majored in songwriting. She met her longtime partner Dave Rawlings at Berklee. They moved to Nashville in 1992 to pursue a career in music.

In a recent interview with The Guardian, Welch told Dave Simpson about her early attraction to Appalachian music:

I was adopted and grew up in southern California, but my people are from North Carolina. When I was eight or nine I asked for an acoustic guitar and would lock myself in my bedroom singing Carter Family songs. It just felt very natural, like I’d inexplicably gravitated towards it. Then after high school I had an epiphany when I heard the Stanley Brothers.

Welch’s first album Revival came out in 1996, produced by longtime Dylan friend and collaborator T Bone Burnett. Note that this is the same year that Burnett produced Bringing Down the Horse, the breakout album for The Wallflowers, fronted by Dylan’s son Jakob. Welch would go on to work closely with Burnett again on the Americana soundtrack for the Coen Brothers’ O Brother, Where Art Thou? (2000).

Welch’s most celebrated release to date is her sophomore album Time (The Revelator) (2001), produced by Rawlings, who also plays on all the songs. The duo has continued to collaborate closely on each other’s projects, and they regularly tour together as well. In 2015, Welch & Rawlings were honored with a Lifetime Achievement Award for Songwriting by the Americana Music Association.

In Alec Wilkinson’s 2004 profile for The New Yorker, he says this about the collaboration: “Because Welch was intent on establishing herself as a songwriter, and because their arrangement began informally, and Rawlings was playing with other people anyway, she says it didn’t occur to them to name the duet; they performed simply as Gillian Welch.” In terms of their working relationship, Welch told Simpson: “Whatever we do it’s always a collaboration. In our living room we write, arrange and record the songs together. We will both sing one until we decide we like one voice better than the other because of the key or because we’re always trying to make the story come across the best it can.” As far as which songs go on which albums, Welch told Graham Reid of Elsewhere that her releases revolve around duets: “Any time we put out a record under my name, it’s what we call a duet record. It’s pretty intense and focused. It’s like life on a spaceship, just the two of us.”

My favorite description of their intertwined sensibilities, invoking their shared love of Dylan, appears in a recent Paste article. Welch told Matt Mitchell:

Since college, we just found that our creative desires aligned. And our taste is almost more than what you like. It’s what you dislike that is really important in a collaborator. Dave and I both hate the same shit. We don’t even need to talk about it. I’ll see him roll his eyes and I know. And likewise, the thing that’ll really send me, it’s the same thing for him. We’ll be at a Dylan concert and Bob will do something, and both Dave and I will be like, “Oh,” at the exact same moment.

The duo readily acknowledges Dylan as a major influence, and they’ve covered his songs on several occasions in a variety of settings. Here is a fascinating example I just learned about from Wilkinson’s New Yorker profile:

In 1997, Rawlings bought a Fender Esquire, an electric guitar, and wanted to use it, so he and Welch got a friend to play drums, and Welch played the electric bass and they began playing clubs as the Esquires. They never announced their performances, and not many people came. They played songs by Neil Young and the Rolling Stones, among others, and Rawlings sang most of them. The Esquires brought to their gigs a complete book of Dylan songs, and once during each evening the audience was allowed to shout out a number. Welch and Rawlings picked one, then turned to the corresponding page in the Dylan book and played whatever song was on that page.

How’s that for learning the Dylan Songbook by chapter and verse? During the pandemic, Welch & Rawlings cobbled together a low-tech compilation of covers, All the Good Times (Are Past & Gone) (2020). This record contains two Dylan songs, “Señor (Tales of Yankee Power)” and “Abandoned Love,” and it won the 2021 Grammy for Best Folk Album.

Their coolest Dylan tribute prior to Woodland came on July 26, 2015. Welch & Rawlings played at the Newport Folk Festival on the 50th anniversary of Dylan “going electric.” They anchored the “’65 Revisited” set, featuring covers of thirteen Dylan songs by an array of amazing artists, including Al Kooper, Dawes, Hozier, Robyn Hitchcock, and Blake Mills.

My favorite performances are by Welch & Rawlings, with Gill taking the leads. She opened with a gorgeous “Mr. Tambourine Man”:

In the fourth slot of the setlist, she delivered a haunting rendition of “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue,” the song Dylan ended his notorious set with in 1965.

Watch these performances and they’ll whet your appetite for the 2025 World of Bob Dylan Conference in Tulsa, set to coincide with the 60th anniversary of Newport ’65. Dear Sean Latham: please try to book Gillian Welch & Dave Rawlings at Cain’s Ballroom!

Enough preliminaries. Let us go then, you and I, to an empty trainload of sky.

“Empty Trainload of Sky”

The first Dylan echo on Woodland appears before anyone speaks a word. Listen carefully to the opening notes of “Empty Trainload of Sky”:

Sound familiar? Sure it does—it’s the same guitar line as Dylan’s “Things Have Changed”:

Welch recently sat down with Jason Isbell—fellow singer-songwriter, Nashville resident, and Dylan fan—to discuss the craft of songwriting for GQ magazine. She revealed this fascinating inspiration for the song:

I actually saw, crossing the Cumberland River, down there on that high trestle that goes over Shelby Bottoms, a very strange visual hallucination, almost. I couldn't quite tell what I was seeing. It was just a trick of the light and what was happening, which was moving and which was stationary, the sky or the train, and was the train empty or was it full of sky? What was happening? It was a real mind bender. And I sat down on the bench right there and didn’t get up until I kind of had the first verse. And then I walked straight home and commenced working on it, setting it to music. And then Dave and I were off to the races.

Welch translated that “very strange visual hallucination” into this first verse:

Saw a freight train yesterday

It was chugging, plugging away

’Cross the river, trestle so high

Just a boxcar of blue

Showing daylight clear through

Just an empty trainload of sky

Trains are everywhere in Americana music. On the literal level, they are associated with long-distance transportation, hauling people and goods across the vast American landscape. In an allegorical sense, trains are often used in gospel songs to carry the saved to the promised land, as in Woody Guthrie’s “This Train Is Bound for Glory” and The Impressions’ “People Get Ready.” Trains are everywhere in Dylan, too. In his first Christian album Slow Train Coming, he takes the heavenly train of folk and gospel and diverts it onto a different track. In the title song he warns that a train will soon arrive to send the wicked on a one-way trip to hell.

“Empty Trainload of Sky” represents both an homage to the folk tradition and a departure. I’m tempted to call it “revisionist folk,” but that would be redundant, since revision has always been fundamental to the folk process. Singers take songs from the tradition, do their own thing with them, then pass them down for future players to adapt. Guthrie did it to the Carter Family, Dylan did it to Guthrie, Welch & Rawlings do it to Dylan, and so on, ad infinitum. May the circle be unbroken.

“Was it spirit? Was it solid? / Did I ditch that class in college?” Maybe she skipped a course in musical metaphysics at Berklee, but Professor Welch is teaching an advanced seminar in it now. She unpacks the train only to fill it back up. This train isn’t bound for glory, nor is it bound for hell, but it’s not bound for nihilism either. Something’s happening here.

You don’t look into this train, you look through it. What you see is something sublime: blue sky. You don’t need a train to see the sky, but it helps you see things differently. The train provides a frame of reference. Empty? No. This train is loaded with significance.

For that matter, the sky is loaded, too. For music aficionados like Welch & Rawlings, you can’t look at the blue sky without immediately hearing correspondent tunes in your head: the Allman Brothers’ “Blue Sky” and ELO’s “Mr. Blue Sky” and Pink Floyd’s “Goodbye Blue Sky” and anything by their beloved Blue Sky Boys. Furthermore, if you know your Dylan as well as they do, then you hear “Underneath that sky of blue” from “New Morning” and “The sunny sky is aqua blue” from “Mozambique” and the singer’s request to “Play ‘Blue Sky’” in “Murder Most Foul.”

Trains and skies and songs about them aren’t merely beautiful, however. Sublime = Beauty + Terror.

Well it hit me and it hurt me

Made my good humor desert me

For a moment I was tempted to fly

To the Devil or the Lord

As it hung there like a sword

Just an empty trainload of sky

You’ll note that allusion to the sword of Damocles, hanging above the singer’s head and reminding her of the weight of responsibility that comes with carrying this tradition forward. “It may be the Devil or it may be the Lord / But you’re gonna have to serve somebody” counsels her mentor Dylan. Play enough folk songs and you’ll end up serving both sooner or later, as Welch well knows: “Pulled the curtain from my eyes / I say hey, hey, my, my.” Out of the blue sky and into the black.

“Lawman”

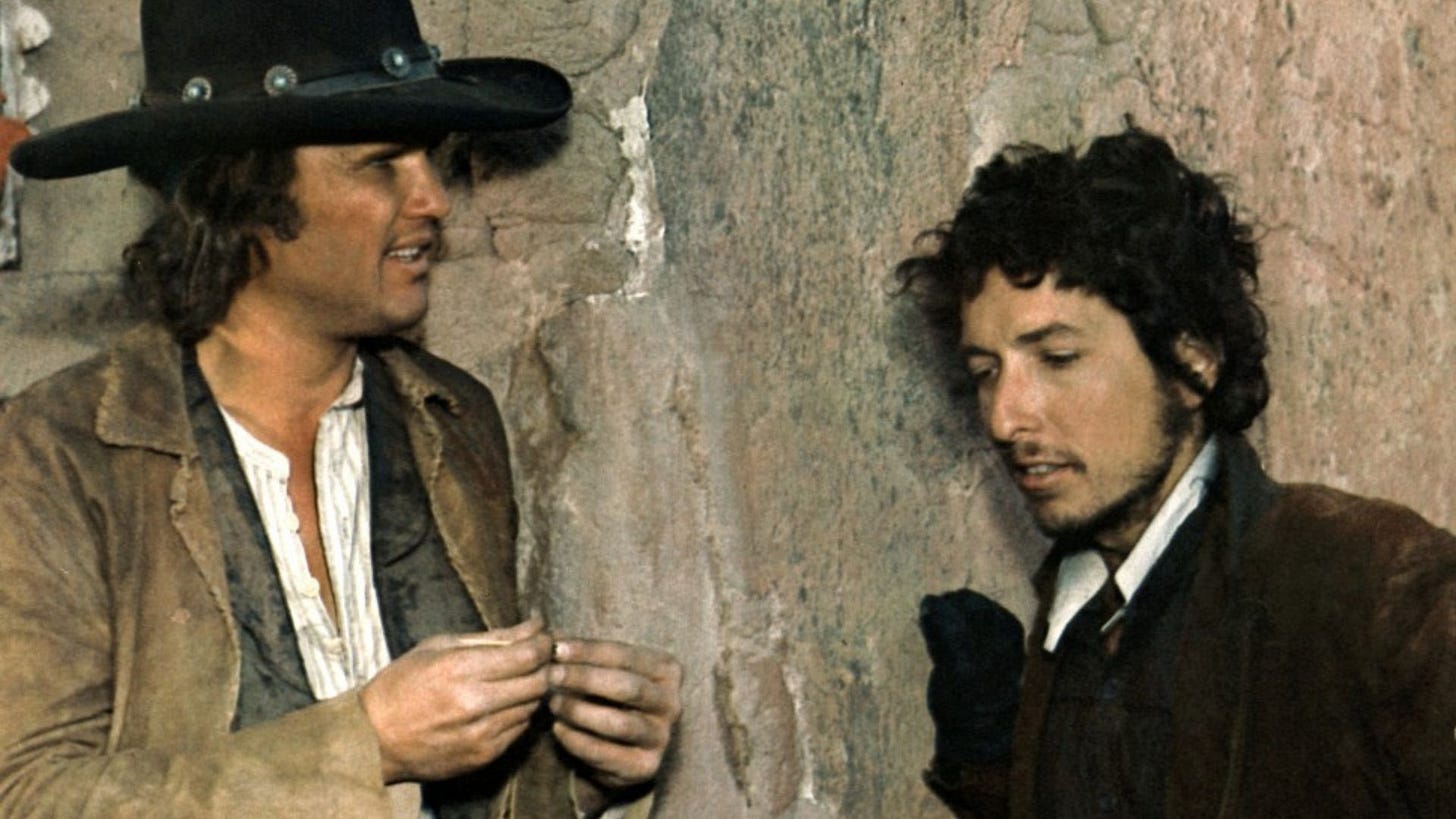

There have been many great covers of Dylan over the years, but I would put Welch & Rawlings’s rendition of “Billy” on the top shelf among the very best.

“Billy 1” is a deep cut from the soundtrack to Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid. Dylan manages to distill the entire film into the first verse:

There’s guns across the river aimin’ at ya

Lawman on your trail, he’d like to catch ya

Bounty hunters, too, they’d like to get ya

Billy, they don’t like you to be so free

Welch & Rawlings released their cover on the 2006 DVD Music from the Revelator Collection. When the duo played the Newport Folk Festival in 2008, they introduced a new song called “Lawman,” surely inspired in part by “Billy.” However, they were dissatisfied with the results and abandoned it.

They resurrected “Lawman” for the Woodland sessions and produced a new version up to their standards. Rawlings recounted the song’s evolution to Isbell:

There was another song called “Lawman” that we wrote 15 years ago that had the same riff. I liked the riff, I liked the title. And two years ago or something, I was like, man, there was something there—if we can just find a song that will go around it. But I remember throwing our hands up with that one and then coming back, and when you come back, you can see the parts of it that you value, and you don't care about your failure at that point. It all falls away.

We should all be grateful that they gave “Lawman” another shot because now it sounds fantastic.

That riff is indeed great, and well worth salvaging. Or scavenging. I think Henry Carrigan is right in his review for Folk Alley that it is lifted and adapted from Blind Faith’s “Can’t Find My Way Home.” And that’s only the first echo you’ll hear in “Lawman.”

Rawlings lays the musical foundation then Welch begins to sing: “Sylvie gonna bring a little water . . .” and already we’re retreading Lead Belly country. Lyrically, “Lawman” is a catalogue of folk archetypes: “Baby’s gonna cry until he’s fed”; “Poor folk gonna scrap for a piece of bread”; “Preacher’s gonna preach from the Bible / Devil’s gonna laugh at what he said.” The refrain returns to the fugitive theme of many roving songs but displays it from a parallax view: “And the lawman / Lawman / Lawman gonna kill my honey dead.”

One of the things I love about Welch as a singer-songwriter is how she returns to familiar musical territory in folk but then defamiliarizes it, often by reconsidering it from a woman’s point of view. Take for instance her shattering performance of “Caleb Meyer,” released on her sophomore album Hell Among the Yearlings (1998).

“Caleb Meyer” is a revisionist murder ballad. Instead of depicting the typical scenario where a cruel man kills a helpless woman, Welch turns the tables. Meyer attacks Nellie Kane while her husband is away and tries to rape her. But she grabs a broken bottleneck and slits his throat. Welch takes the folk trope, upends it, and spills its blood on the ground. “Lawman” may not be as startling as “Caleb Meyer,” but it’s the byproduct of a similar aesthetic.

The thing that strikes me most about Welch’s viewpoint in “Lawman” isn’t her pining for lost love but rather the tragic sense of inevitability. The word she pounds home over and over is “gonna”: these things are going to happen, they have always happened, and they always will happen, repeated endlessly. This is the myth of eternal return. Sylvie is always gonna bring a little water because that’s her function in the folk cosmos.

Billy the Kid and Pat Garrett may once have been real-life historical figures, but not anymore. They’ve been transported to the realm of myth and transfigured into archetypes. Now and forever, Billy is the prototypical Outlaw and Garrett the quintessential Lawman. Their fateful encounter, resulting in one killing the other, is written in the stars, as fated as Oedipus killing Laius, Cain killing Abel, and Stagger Lee killing Billy Lyons. Every time the song is sung, we leave profane time and reenter sacred time where the myth is reenacted anew.

Dylan knows, loves, and honors this mythic world. He is a high priest of the folk religion. He accepted the creed as a young man, and he has kept the faith ever since (despite being denounced as a heretic in 1965). He espouses the tenets of the faith in Chronicles:

Folk music was a reality of a more brilliant dimension. It exceeded all human understanding, and if it called out to you, you could disappear and be sucked into it. I felt right at home in this mythical realm made up not with individuals so much as archetypes, vividly drawn archetypes of humanity, metaphysical in shape, each rugged soul filled with natural knowing and inner wisdom. Each demanding a degree of respect. I could believe in the full spectrum of it and sing about it. It was so real, so more true to life than life itself. It was life magnified. Folk music was all I needed to exist. (236)

Welch draws from these same archetypes, but her reenactments of the myths offer repetition with variation. For instance, instead of focusing on the experience of the Outlaw (as Dylan does in “Billy 1”) or the Lawman (as he does in “Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door”), Welch voices the perspective of the Widow. “Lawman gonna kill my honey dead,” sings his grieving survivor. Welch does for Americana outlaw ballads what Dolores O’Riordan did for Irish rebel ballads in The Cranberries’ “Zombie.” Rather than glorifying the exploits and martyrdom of outlaws/rebels, Welch and O’Riordan shift the focus to the generational sacrifices and cyclical traumas of women caught in the emotional crossfire of atavistic male violence.

“North Country”

Much as Welch & Rawlings draw from the same cast of archetypal characters as Dylan, they also dwell in similar metaphysical territory. Think of his “Sad-Eyed Lady of the Lowlands” and their “Lowlands,” both drawing on Odetta’s “Lowlands” and several Child ballads rooted in a similar setting. Think of their “Scarlet Town” and his “Scarlet Town,” both drawing on the great folk song “Barbara Allen.” And now we can add “North Country” to the list, the fifth track on Woodland, with its overt debts to Dylan’s “Girl from the North Country” and “North Country Blues.”

Remember that “Girl from the North Country” is itself a response to an earlier song, “Scarborough Fair,” about a man sending a message through an intermediary to his former lover. He has moved away, but she still lives in their old hometown, and he still thinks of her. In “Girl from the North Country,” snowy wintertime conjures the true love back to mind. Welch borrows this same setup for her “North Country,” but she skips the intermediary and sends a message directly to the old flame:

I don’t make it up this way too often

Now the cold is a little bit hard on me

Gotta wait for the season to soften

Before I make the trip from Tennessee

Way up in the North Country

Tennessee is a specific state, but the North Country feels more like a state of mind. There’s a vast gulf separating the singer from the addressee, and it’s not merely geographical. The singer has made that hard journey in the past, but it’s not clear that they (Welch never specifies gender) will ever be able to make it again. “Wintertime in the pines and the snow is coming on / You’ll be back when the cold winds blow, I’ll be gone.” It sounds like the singer is bound for that undiscovered country from whose bourn no traveler returns: Death.

In the meantime, the two communicate long distance through letters: “Some long dark night you might send me a letter / Full of sleepless devilry.” I think of all those letters in Dylan songs across his entire canon: “Farewell,” “John Brown,” “Boots of Spanish Leather,” “Desolation Row,” “Idiot Wind,” “Where Are You Tonight? (Journey through Dark Heat),” “When the Night Comes Falling from the Sky,” “Not Dark Yet,” “’Cross the Green Mountain,” etc. No one writes letters anymore: you might as well send your message by carrier pigeon or pony express. But people still sing songs about letters, and the songs function as messages from singer to listener, and in this case from one songwriter to another. It’s no accident that this song-letter is sent from Tennessee—where Welch lives and where Woodland was recorded—and is addressed to the North Country. Forget Malibu: Dylan will always be from the North Country.

She even adds a postscript to Dylan, the poet laureate of freedom, in her final lines: “I’ll tell you now we could be together / If you ever get tired of being free / Way up in the North Country.” Surely she is echoing “Billy” again: “Billy, they don’t like ya to be so free.” But as Dylan and Welch both know from Billy (aka Kris Kristofferson), “Freedom’s just another word for nothin’ left to lose / Nothin’ ain’t worth nothin’ but it’s free.”

“The Day the Mississippi Died” & “Hashtag”

“The Day the Mississippi Died” is one of the standout songs on Woodland. It achieves the delicate balance that Dylan has always been so good at, writing songs that are at once local and universal, of a specific time & place and of all time, commenting on contemporary conditions while seeming as if they could have been written a hundred years ago.

Welch & Rawlings poignantly comment on the era of Donald Trump, the Covid pandemic, and the existential climate crisis when she sings,

Now the truth is hard to swallow, it’s hard to take

But I do believe we’ve broken what we never knew could break

I’m just so disappointed in me and you

We can’t even argue so what else can we do

But they also wade into the waters of archetype and allegory. Mississippi is the name given to an actual river and state, but it’s also loaded with historical and mythological significance. It is the flow of American history cutting through the heart of the country in Mark Twain’s Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and William Faulkner’s Yoknapatawpha County novels. It is the capital of racism and degradation in Nina Simone’s “Mississippi Goddam.” It is the Golgotha of civil rights sacrifice in Dylan’s “Only a Pawn in Their Game,” and the epitome of African American experience—from the Middle Passage through slavery, from Parchman Farm to the Great Migration—in his epic “Mississippi.”

The mighty Mississippi represents America itself, its hope and its despair, its promises and its betrayals, the blues skies and the black. In his chapter on The Clash’s “London Calling” from The Philosophy of Modern Song, Dylan asserts, “Any time you mention a river in America you are thinking about the Mississippi. A beautiful, wide flowing body of water that rolls down the middle of America. And everything that that conjures up. The Clash are talking about the Thames. But in America you can’t help but think Mississippi” (161).

I’ve been focusing on the Dylan threads in Woodland, but there are countless other musical scraps in Welch & Rawlings’s quilt. For instance, take a listen to the final verse of “The Day the Mississippi Died”: “My pony he did stumble and sent me to the sky / When the jury brought the verdict it was a blue tail fly.” They’re giving us the key to decoding yet another folk source, this time from “Blue Tail Fly,” sometimes called “Jimmy Crack Corn.”

The song is best known by Burl Ives, though it dates back to the minstrel shows of the mid-19th century. Pay attention to the lyrics and you’ll find that it’s sung from the perspective of a slave whose master dies when he’s thrown from his horse:

My pony run, he jumped, he pitch

He threw my master in the ditch

He died and the jury wondered why

The verdict was the blue tail fly

The song was a favorite of Abraham Lincoln, and he even had it played as the introduction before he delivered the Gettysburg Address (Brodie 180). American music and history have always flowed into and out of each other, converging at the delta of the Mississippi.

Welch & Rawlings foretell a day when this mighty Mississippi will run dry. The chorus is a classic “come all ye” in the folk tradition, but it is also a eulogy:

So fill up ’em once again, boys

Fill ’em up and over the brim, boys

There’s whiskey but the water done run dry

We’re drinking to the end of a long, long friend

And the day the mighty Mississippi died

In raising a parting glass to the Mississippi, Welch & Rawlings are throwing a wake for the death of America.

They have other personal losses in mind, too. The track that precedes “The Day the Mississippi Died” is “Hashtag.” Here’s a very touching rendition from the 2024 Newport Folk Festival:

As Welch & Rawlings have noted in interviews, the song was inspired by seeing #GuyClark trending on Twitter and knowing instantly that he must have died. As Welch writes and Rawlings sings,

You laughed and said the news would be bad

If I ever saw your name in a hashtag

Singers like you and I

Are only news when we die

Welch & Rawlings meditate upon the magnitude of loss as one after another mentor dies.

So here I’m sitting ’round another night

Looking at your boots, Jesus Christ

That’s some mighty big ones to try to fill

Never can and never will

So here’s another song that’s over now

You’re another sun that’s done gone down

Put another good one in the ground

Good Lord it’s goin’ ’round

This same sentiment carries over into “The Day the Mississippi” died. On a deep (subconscious?) level, I think Welch & Rawlings are imagining that dark day when we’ll lose our greatest living folk singer. Guy Clark certainly left some big boots to fill, but Jesus Christ, think how big Dylan’s boots are. The voice of his generation has become the voice of America, as he himself seems to concede in “I Feel a Change Comin’ On”: “Some people they tell me / I got the blood of the land in my voice.” Blood of the river, too. From a folk singer’s perspective, losing Dylan will be the equivalent of the mighty Mississippi running dry.

I’m reminded of a passing comment Welch made to Hanif Abdurraqib for his piece in the New York Times Magazine:

Welch speaks the way she writes, the way she sings — with a deeply controlled thoughtfulness layered with a matter-of-fact honesty. As we talked about some of our singing and writing heroes, Welch mentioned Bob Dylan. “I don’t know what I’ll do when he’s gone,” she told me, pausing to stare into the rain-soaked distance. “I can’t even talk about it.”

No, but perhaps she can sing about it.

“Here Stands a Woman”

Now we come to my favorite song on Woodland: “Here Stands a Woman.” Dylan has always been a loving thief, stealing freely from the songs that inspired him. Beginning with Time Out of Mind (1997), his appropriations became so frequent and so ingenious that you could footnote practically every line, tracing it back to some previous source. Not only is “Here Stands a Woman” an answer song to “Just Like a Woman,” but Welch writes the song using Dylan’s trademark patchwork method.

Dylan doesn’t give the addressee a name in this controversial classic from Blonde on Blonde (1966). He simply calls her Baby.

Nobody feels any pain

Tonight as I stand inside the rain

Everybody knows

That Baby’s got new clothes

But lately I see her ribbons and her bows

Have fallen from her curls

The chorus of “Just Like a Woman” is the section most frequently cited as evidence of Dylan’s sexism in the song:

She takes just like a woman, yes, she does

She makes love just like a woman, yes, she does

And she aches just like a woman

But she breaks just like a little girl

In “Here Stands a Woman,” Baby is all grown up. Gillian Welch fully inhabits her perspective, gives her voice, and sees her reflection in the mirror of Dylan’s song.

You told me that you loved me

And that would never change

Now I’m looking in the mirror

And I know that I’m to blame

’Cause it’s all gone Babe

Like the song says

“Fallen from her curls”

Here stands a woman

Where there once was a girl

We know precisely what song she’s referring to because she quotes from it directly: “Fallen from her curls.” Yeah? Well, things have changed. She is risen. What an empowering gesture: Dylan reduces the fallen woman to a girl, but Welch recuperates Baby as a Woman with a backbone.

“Here Stands a Woman” may sound like a revisionist anthem for the #MeToo era, and maybe it is. But it is also an ambivalent song. For instance, what do we do with the line, “I know that I’m to blame”? This is not a straightforward finger-pointing song. When the singer looks in the mirror, she sees a woman, not a girl. Maybe the girl would have seen her ex-lover as the villain, but the woman knows it’s more complicated than that. She proves her maturity by accepting a share of blame for the breakup.

Listen to these songs back to back and you can tell that “Just Like a Woman” was written by a 25-year-old and “Here Stands a Woman” was written by a 57-year-old. As Welch told Amanda Petrusich of The New Yorker, it took her years to grow into the songs she sings: “I had to work my way up to the more raw and primary emotions that are present in a Stanley Brothers song. That was a lot to handle. The drunk husband, the man damned to a life in jail—I had to work my way up to processing that. But now, you know, I’m kinda there. I’m a grown woman now, and—excuse my language—some shit has happened.” Here stands a woman where there once was a girl.

To be fair, “Just Like a Woman” was never simply a reactionary expression of misogyny. The chorus is condescending, no doubt about it, but other lyrics reveal that the singer and this so-called Baby have more in common than he’s comfortable to admit. He makes it clear in the final verse that she was the more powerful partner from the start. He also confesses his vulnerability and insecurity now that they’ve broken up:

I just can’t fit

Yes, I believe it’s time for us to quit

When we meet again

Introduced as friends

Please don’t let on that you knew me when

I was hungry and it was your world

He, too, breaks like a little child.

In the second verse of “Here Stands a Woman,” the singer shifts focus from her lover to her parents. This is familiar territory for Welch, who performed the beautiful “Orphan Girl” on her debut album Revival (1996), and returned to the subject with “I Had a Real Good Mother and Father” and “No One Knows My Name” on Soul Journey (2003). But she’s not yet done with her adopted musical father Dylan:

The mother and the father

Who kept me in their care

They’re both gone like the ribbons

That I used to wear

But it’s alright, Ma

Things got tight, Pa

So I went and pawned the pearls

Here stands a woman

Where there once was a girl

See what I mean about her patchwork method? There are those ribbons again, the ones that fell from Baby’s curls in “Just Like a Woman.” These ribbons trace their parentage back to Paul Clayton’s “Who’s Gonna Buy You Ribbons?,” Dylan’s prototype for “Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right.” You’ll also notice the allusion to “It’s Alright, Ma (I’m Only Bleeding),” which unabashedly borrows its title from Elvis Presley’s “That’s All Right, Mama.” The pearls belong to Baby—“With her fog, her amphetamines, and her pearls”—but the act of pawning them mirrors Miss Lonely in “Like a Rolling Stone”—“You better take your diamond ring, you better pawn it, Babe.”

Welch continues to trace the genealogy of songs in the third verse when she sings, “I come a long way from Danville / Where they wear that Danville curl.” Oh, you’re good, Gill! Let’s uncurl these lines. The singer is now looking into another song and seeing her reflection: Woody Guthrie’s “Danville Girl.” This song tells the story of a man waiting in the train station hoping to catch a free ride:

Standin’ on the platform

Smokin’ a big cigar

Waitin’ for some old freight train

That carries an empty car

During one of his stops, the singer falls in love. But as a wanderer who roams and rambles, loving the road more than the women he encounters, he soon hops another train and leaves her behind:

I rode her down to Danville town

Got stuck on a Danville girl

Bet your life she was a pearl

She wore that Danville curl

She wore her hat on the back of her head

Like high-tone people all do

Very next train come down that track

I bid that girl adieu

Welch performs a paternity test on “Just Like a Woman” and reveals Woody Guthrie’s “Danville Girl” as its musical father, which in turn makes him the grandfather of “Here Stands a Woman.”

Dylan’s inheritance from Guthrie runs deep. He draws most overtly on “Danville Girl” for inspiration in “Brownsville Girl.” Co-written with Sam Shepard, this masterpiece from Knocked Out Loaded (1986) was originally titled “New Danville Girl.” The location shifts to Brownsville, but the musical source is unmistakable in the chorus:

Brownsville girl with your Brownsville curls

Teeth like pearls shining like the moon above

Brownsville girl, show me all around the world

Brownsville girl, you’re my honey love

Dylan’s debts to “Danville Girl” are subtler in “Just Like a Woman,” but Welch knows a curl and a pearl when she sees one. She writes “Here Stands a Woman” as an answer song to “Just Like a Woman,” but in the process she shows that Dylan himself was answering Guthrie’s “Danville Girl.”

And there’s still more. In the final refrain, she switches the song quotation: “’Cause it’s all gone, Babe / Like the songs says / ‘I been all around this world.’” Instead of quoting “Just Like a Woman,” this time she quotes “I’ve Been All Around This World.” This folk song is best known as “Hang Me, Oh Hang Me” by Dave Van Ronk, as made popular by Oscar Isaac’s moving cover in the Coen Brothers’ Inside Llewyn Davis. Welch uncurls Dylan’s sources again, this time inserting a footnote to the line “Brownsville Girl, show me all around the world.”

Over the course of this palimpsestuous song, Welch channels Baby, Miss Lonely, the Danville Girl, and the Brownsville Girl. She descends from their lineage, yet she stands independent from them because she ain’t no girl. She stresses the point not only through what she says but also what she leaves out. The last line of her song is the simple declaration: “Here stands a woman.” Period. She omits the previous line “Where there once was a girl.” By the end, that goes without saying. Girl time is over.

In her conversation with Jason Isbell, Welch reflected on her songs with Rawlings in relation to the folk tradition:

I think it’s understood that, in folk music, even if we’re writing original songs—I mean, the great folk tunes, who wrote ’em? Everybody wrote ’em. Every voice that sang ’em, every hand that they passed through added something to them. And so that’s kind of what I’m talking about is I’m proud that at this point, I see our hand having done something to the world of folk, I sort of see our imprint. But at the same time, I’m able to see what came before and I see what's coming after and it’s cool.

This is an excellent definition of what I mean by intertextual duets. Woodland presents an ideal case study in how to take shreds and patches from one’s musical forebears, stitch them into provocative patterns, and invent something new out of the old. It’s the re-creative process Dylan has perfected over the course of his long career, and it’s the same process used by his most sensitive and discerning inheritors. As Welch & Rawlings sing in “Howdy Howdy,” the final song on Woodland, “We’ve been together since I don’t know when / And the best part’s where one starts and the other ends.” This is Welch & Rawlings singing to each other, but it’s also both of them singing back to the tradition, engaging in an ongoing polyphonic dialogue with the past. As we’ve seen and heard, one of their most inspirational duet partners is Bob Dylan.

Works Cited

Abdurraqib, Hanif. “How Gillian Welch and David Rawlings Held Onto Optimism.” New York Times Magazine (3 November 2020), https://www.nytimes.com/2020/11/03/magazine/gillian-welch-dave-rawlings.html.

“Blue Tail Fly: About the Song.” Ballad of America, https://balladofamerica.org/blue-tail-fly/.

Brodie, Ian, “Crime and Punishment in the Cape Breton Songs Contest,” Ethnologies 41.1 (2019): 173-95.

Carrigan, Henry. “Album Review: Gillian Welch and David Rawlings, ‘Woodland.’” Folk Alley (21 August 2024), https://folkalley.com/album-review-gillian-welch-and-david-rawlings-woodland/.

Dylan, Bob. Chronicles, Volume One. Simon & Schuster, 2004.

---. Official Lyrics. The Official Bob Dylan Website.

https://www.bobdylan.com/.

---. The Philosophy of Modern Song. Simon & Schuster, 2022.

Isbell, Jason. “Gillian Welch and David Rawlings Talk to Jason Isbell About Their New Album Woodland and the Art of Songwriting.” GQ (23 August 2024), https://www.gq.com/story/gillian-welch-and-dave-rawlings-talk-to-jason-isbell.

Guthrie, Woody. “Danville Girl.” Woody Guthrie Lyrics, https://www.woodyguthrie.org/Lyrics/Danville_Girl.htm.

Kristofferson, Kris. Kristofferson. Monument, 1970.

Mitchell, Matt. “Gillian Welch & David Rawlings: Just the Two of Us.” Paste (17 September 2024), https://www.pastemagazine.com/music/gillian-welch-david-rawlings/gillian-welch-david-rawlings-just-the-two-of-us.

Petrusich, Amanda. “What Gillian Welch and David Rawlings Took from the Tornado.” The New Yorker (25 August 2024), https://www.newyorker.com/culture/the-new-yorker-interview/what-gillian-welch-and-dave-rawlings-took-from-the-tornado.

Reid, Graham. “Gillian Welch Interviewed (2016): Taking sad songs to make it better.” Elsewhere (18 January 2016), https://www.elsewhere.co.nz/absoluteelsewhere/7322/gillian-welch-interviewed-2016-taking-sad-songs-to-make-it-better/.

Simpson, Dave. “Americana icon Gillian Welch: ‘Bob Dylan walking on to our version of Billy put a smile on my face.’” The Guardian (8 August 2024), https://www.theguardian.com/music/article/2024/aug/08/americana-icon-gillian-welch-bob-dylan-walking-on-to-our-version-of-billy-put-a-smile-on-my-face.

Welch, Gillian and David Rawlings. Woodland. Acony, 2024.

Wilkinson, Alec. “The Ghostly Ones.” The New Yorker (12 September 2004), https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2004/09/20/the-ghostly-ones.

Stupendous Graley. Been loving the new album, hearing the Dylan references and echos, but this piece just blows me away! Saw them at The Beacon about a decade ago, just gorgeous.

This is just a terrific piece. Here's something that will amuse you while it reinforces one of your central observations - Bob Dylan got the music for "Things Have Changed" from "Observations of a Crow" by Marty Stuart from his 1999 concept album "The Pilgrim." The story is that Dylan was in Nashville looking over Marty Stuart's collection of Nudie Suits and other C&W memorabilia and told Marty that he wanted to use the song for something he had in mind. Stuart noted that he'd taken a lot from Dylan and that Dylan was welcome to it. Hilariously, after "Things Have Changed" came out some critics accused Stuart of cribbing the music from Dylan. It is great to see that Welch & Rawlings have put it to further good use. It is pretty great. Be sure to take a listen to "Observations of a Crow"

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Kr7rst4jEY0&ab_channel=MartyStuart-Topic