Dylan in Cincinnati: March 1965

One of the most famous rock concerts in Cincinnati history was The Beatles’ show at the Cincinnati Gardens on August 27, 1964. Civic leaders didn’t know what hit them. The front page of the Cincinnati Enquirer on August 28 reads like coverage of a natural disaster:

The unnamed journalist covering this pandemonium reported, “A screaming, howling ‘Beatle-cane’ struck Cincinnati Gardens Thursday night. Veteran reporters and policemen were stuck for words to describe the demonstration 14,000 seemingly demented teenagers put on for their idols. ‘Unbelievable’ was the closest they could come to creating a word picture of the bedlam” (1). As you can see, the story included a photo of several screaming teen girls holding hand-made posters and a giant image of doe-eyed Paul McCartney.

Inside the sweltering arena, the crowd was whipped into a frenzy when the lads from Liverpool took the stage:

Then it struck. The Beatles made their appearance, and the mob exploded into a maelstrom of sound—screaming, stomping, crying, begging, moaning—every imaginable sound a human is capable of making. The Beatles played three numbers, but they might as well have been doing a pantomime. The screaming was so loud for 10 minutes that the Mormon Tabernacle Choir and the Marine Corps Band would have been drowned out.” (1)

The story portrayed an outbreak of mass hysteria, as well as an assault on community values staged by foreign agitators: “The youngsters were in the midst of an emotional banzai attack against anything that remotely resembled logic and order. Some sobbed, clutching their hands to their mouths. Others waved their hands above their heads and screamed at the tops of their lungs. Some jumped up and down on their seats” (1).

Hamilton County Juvenile Court Judge Benjamin Schwartz was so disturbed by the show that he delivered a stern—and absolutely priceless—public rebuke. You have to check this out:

Judge Benjamin Schwartz, “The Beatles are a threat to our children, especially girls: A Warning from Cincinnati, August 1964.” YouTube clip posted by acmestreamingDOTcom.

The judge condemned parents for allowing their children to attend this hysteria-inducing bacchanal. He essentially warned city leaders and parents not to sit back idly in the future and permit an infestation of parasites (i.e., Beatles) to infect the city’s youth.

The Beatles did not hang around long enough to read the local papers or receive their judicial scolding. The Fab Four flew directly from Cincinnati to New York to play at the Forest Hills Tennis Stadium on August 28. That night they met Bob Dylan for the first time at the Delmonico Hotel—where he apparently got them stoned for the first time, too.

John, Paul, George, and Ringo should not feel so all alone: Dylan would also get stoned by the Cincinnati press during his first appearances there the following year. His music and persona were markedly different from The Beatles in 1964. In fact, the folkies and progressives who revered Dylan thought Beatlemania was a vapid farce. Such fine distinctions were lost on the guardians and protectors of Cincinnati, however. For worried civic leaders and parents, there was no point in splitting hairs. Call it a Beatle or call it a beatnik, these outsiders were seen as Pied Pipers coming to enchant and abduct the city’s youth.

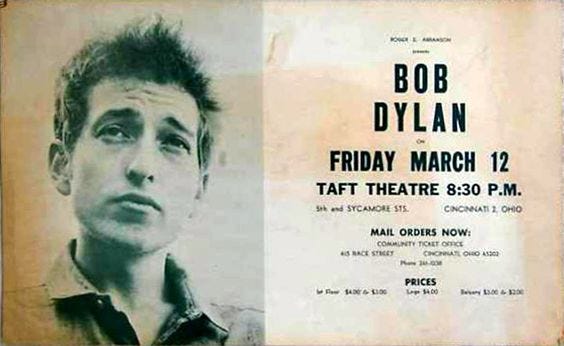

Sadly, no recordings survive of Dylan’s first two concerts in Cincinnati. He played at the Taft Theatre on March 12, 1965, during his final solo acoustic tour, and he returned to Music Hall on November 7 with The Hawks during his first electric tour. Unlike most installments in my Dylan in Cincinnati series, I won’t be able to comment in detail upon performances from these 1965 shows without the aid of bootlegs. Luckily, however, Dylan’s first visits to the city received intense local press coverage. So even if the concerts as such are lost to history, the media record left behind paints a vivid portrait of both Dylan and Cincinnati in 1965.

Dylan Context

By the spring of 1965, Dylan’s reputation as “voice of his generation” was as firmly affixed as an albatross around his neck. He bristled at the label and insisted that he never wanted the job, but his complaints were futile. Dylan was fitted for a (thorny) crown as the Prince of Protest whether he liked it or not. He first garnered attention as part of the early sixties Greenwich Village folk scene. As he put it in Chronicles, “What I was playing at the time were hard-lipped folk songs with fire and brimstone servings, and you didn’t need to take polls to know that they didn’t match up with anything on the radio, didn’t lend themselves to commercialism” (6). Despite his apparent lack of commercial appeal, Dylan distinguished himself from the start as a uniquely charismatic chameleon. He soon caught the attention of legendary record executive John Hammond, Sr., who offered him a recording contract with Columbia Records. After releasing a largely overlooked 1962 debut album consisting mostly of folk covers, Dylan catapulted to fame on the strength of his next three albums: The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan (1963), The Times They Are A-Changin’ (1964) and Another Side of Bob Dylan (1964).

He performed his original material solo with acoustic guitar and harmonica so that it sounded like traditional folk music of the past. But his subject matter was strikingly contemporary and captured the spirit of the age. Dylan wrote and sang like no one else about the ideals, angers, hopes, desires, and pain of young people. In rapid succession he churned out one anthem after another: ripped from the head, the heart, and the headlines; fueled by intelligence, sensitivity, humor, empathy, bravado, and rage; committed to calling out pettiness, mendacity, greed, hypocrisy, injustice, and bigotry wherever he saw it; by turns shaming the guilty, consoling the abused, embracing the outcast, prodding the apathetic, and inspiring activists fighting for positive change.

From the perspective of his most ardent fans, Dylan was the antidote to the mindless entertainment and frivolous banality of pop music epitomized by The Beatles. “For people committed to that struggle,” writes Elijah Wald, “it was obvious why a lot of white youngsters would rather imagine themselves in swinging London than in murderous Mississippi, and more important than ever for the music of involvement to counteract the music of escape” (190). Dylan had a different, more engaged, and it would seem morally superior message than “I want to hold your hand.” His songs counseled listeners to keep your eyes on the prize and your shoulder to the plow, for the answer is blowin’ in the wind and the times they are a-changin’.

In retrospect, however, it seems clear that Dylan was beginning to change, too. The title Another Side of Bob Dylan provided the first clue that he was turning over a new leaf in his back pages, and his musical transformation was even more apparent on Bringing It All Back Home (1965), the first side of which featured electrical instruments, a known gateway drug leading to rock ’n’ roll. This seismic album had already been recorded by the time Dylan arrived for his first concert in Cincinnati, and it was released just ten days later.

The Prince of Protest was on his way out, deposed by the King of Cool. “In 1965, Bob Dylan was the coolest person on the planet,” proclaims Lee Marshall. “He dressed immaculately, without ever seeming contrived; his hair became increasingly uncontrolled and somehow still managed to look perfect; he held court with icy with and implacable nerve; he played mind games to destroy journalistic triviality” (93).

Swinging London hipster Marianne Faithfull agrees. Looking back at Dylan in the spring of 1965, during the English tour documented in Dont Look Back, she recalls: “Dylan was, at that moment in time, nothing less than the hippest person on earth. The zeitgeist streamed through him like electricity. He was my Existential hero, the gangling Rimbaud of rock, and I wanted to meet him more than any other living being. I wasn’t simply a fan; I worshipped him” (40). Patti Smith also gravitated toward Dylan not as a folk protest singer but as a thrillingly dangerous outlaw: “I look at him and I don’t see a guy giving out leaflets, holding a banner. I see a machine gun” (Miles 95).

Dylan’s 1965 song “Tombstone Blues” opens: “The sweet pretty things are in bed now of course / The city fathers they’re trying to endorse / The reincarnation of Paul Revere’s horse / But the town has no need to be nervous.” Likewise, the city fathers (and mothers) were very nervous about what effect the Prince of Protest and King of Cool would have on the Queen City.

Cincinnati Context

The local papers open a window onto the city the day Dylan first played here. The biggest news story on March 12, 1965, involved a different outlaw named Bobby. The Enquirer led with updates on the so-called “trunk murder” trial of Bobby Abbott, a 21-year-old Bellevue, Kentucky, man accused of killing a local nursing student, Wanda Cook, in a Cincinnati hotel room and then disposing of her body in a trunk. Abbott was eventually found guilty and sentenced to life in prison. The front page also reported that the city was being considered as home for a new pro football franchise. Cincinnati City Council approved construction of Riverfront Stadium in 1966, and the Cincinnati Bengals debuted in the American Football League in 1967. In national news, the Enquirer reported the murder of Rev. James J. Reeb, a white Boston minister beaten to death by segregationists in Selma, Alabama. In a related story, Attorney General Nicholas Katzenbach said federal charges were forthcoming for brutal attacks on civil rights marchers in Selma; “Bloody Sunday” had taken place the previous week.

The other major local newspaper in 1965 was the Cincinnati Post and Times-Star. The Post was the slightly more liberal alternative to the staunchly conservative Enquirer. In 1958 the Post merged with the Cincinnati-Times Star, a paper founded in 1880 by Charles Phelps Taft. While the Cincinnati Post and Times-Star was politically left of the Enquirer, it still reflected the predominant social conservatism of the city. For instance, its front page on March 12, 1965, included a column titled “Lack of Schooling, Sloth Blamed in Stenographer Shortage.” The opening says a lot about views of young women at this time and in this place:

Cincinnati is—and chronically has been for years—short on stenographers and secretaries. If there were enough girls to go around, with adequate skill, more than 1000 steady jobs could be filled overnight. The shortage is not one of people looking for work so much as one of skills. Employers and employment agencies blame the shortage on two main things—schooling and sloth. Employers don’t think high schools teach enough typing, shorthand, business arithmetic. And they think many of the graduates who want jobs don’t want to work. Many who do want to work overestimate their abilities and think they’ll get by with what is really mediocrity. (1)

The rhetoric of this column is belittling and the assumptions behind it are sexist. I cite it not merely to cluck my tongue and wag my finger, but also to draw attention to the prevailing climate in the local media and larger community when it came to gender matters. As will soon become clear, journalists and self-appointed defenders of public decency repeatedly resorted to denigrating sexual stereotypes in describing Dylan and his supporters during his Cincinnati appearances in 1965.

Ahead of Dylan’s first show on Friday night, the Enquirer primed the pump with a piece on him in the Sunday paper. Gerald White’s article attempted to account for Dylan’s special appeal to university students. “For many Cincinnati students, their conscience will sing at the Taft Theatre next Friday night. Their conscience is Bob Dylan, a nationally-known folk singer, who seems to represent the modern, college student” (4-F). White sounded a refrain repeated many times in local reactions to Dylan: parents just didn’t understand what kids saw and heard in this guy. The perennial divide between old and young had widened into a chasm between “the greatest generation” and their “baby boomer” offspring.

In his book The Rise and Fall of the American Teenager, Thomas Hine studies the dichotomy in adult attitudes toward teens.

We love the idea of youth but are prone to panic about the young. […] The very qualities that adults find exciting and attractive about teenagers are entangled with those we find terrifying. Their energy threatens anarchy. Their physical beauty and budding sexuality menaces moral standards. Their assertion of physical and intellectual power makes their parents at once proud and painfully aware of their own mortality. (11)

According to Hine, these contradictory impulses create a “teenage mystique” that adults find simultaneously appealing and adversarial: “This mystique encourages adults to see teenagers (and young people to see themselves) not as individuals but as potential problems” (11). The teenage mystique is apparent everywhere in Cincinnati coverage of Dylan in 1965, beginning with the Gerald White piece in the Enquirer.

If journalists couldn’t bridge the gap in the generational divide, they might at least try to decode the smoke signals coming from the opposing tribe. Dylan seemed to speak the secret argot of youth, but White found it all quite indecipherable:

In turmoil, agitated, involved with issues, Dylan and the college students of today seem to speak some strange language, do strange things, act out strange parts when viewed by the middle-aged and older people. Many people, now in their late 30s and 40s, remember their college days—and the cool world after World War II. Then, students didn’t get excited about anything. Their only sit-ins were in the college hangouts. Their only drive was to drink more beer than the guy across the table. Now, they wonder, shake their heads and marvel a little at the activities of Dylan and his fellow students. (4-F)

White was apparently unaware that Dylan was a college dropout, or that he generally opted out of marches, rallies, and other forms of direct political action. White simply lumped Dylan in with his caricature of Joe and Jill College, 1965 protest edition, and proceeded to tar them all with the same brush: “The sit-ins, the demonstrations, the picket carrying—all would have been unheard of 10 years ago, maybe five. But not now—now college students rush off to Mississippi to rebuild burned-out churches, accept beatings for civil rights causes, parade, work, struggle for their causes, conservative or liberal” (4-F).

White made little attempt to conceal his contempt for social activism, the pampered idealists who pursued it, and the musical jingoists who encouraged it. He was concerned at the prospect of civil unrest agitated by outsiders poised to swarm Cincinnati like the infestation Judge Schwartz prophesized. “Involved students were first only on the East and West coasts campuses,” White observed. “But they’ve now come to the University of Cincinnati and the other local and area campuses. Witness the recent demonstrations for and against America’s participation in South Vietnam” (4-F). Today the Greater Cincinnati Society of Professional Journalists gives an annual prize called the Gerald White Memorial Award, honoring the best work of investigative journalism for the year. He may well have earned that honor over the course of his distinguished career, but he wouldn’t have deserved his own award for this article. Gerald White knew almost nothing about Bob Dylan, but he knew enough to be suspicious. Apparently emboldened by a sense of civic duty, he roused his neighbors in the concerned citizens’ brigade like the reincarnation of Paul Revere’s horse. The radicals are coming! Quarantine your sons and daughters: a super-spreader event will break out this Friday.

Concert at Taft Theatre

The Friday night show took place at the Taft Theatre on Fifth Street downtown. The venue opened in 1928 as an extension of the Cincinnati Masonic Temple next door and was named after a prominent member of its order, Charles Phelps Taft. As I mentioned in the introduction, the Tafts are Cincinnati royalty. Charles Phelps Taft’s father, Alphonso Taft, served simultaneously as U.S. Attorney General and Secretary of War (1876-1877) in President Ulysses S. Grant’s administration. Alphonso Taft also co-founded Skull and Bones, a Yale secret society to which generations of powerful Tafts belonged, including William Howard Taft [U.S. President (1909-1913) and Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court (1923-1930)], Robert Alphonso Taft [U.S. Senator for Ohio (1939-1953)], and Charles Phelps Taft II [Mayor of Cincinnati (1955-1957)]. [For more on Dylan’s unexpected intersections with Skull and Bones, see my piece for The Dylantantes.] Charles Phelps Taft founded the Cincinnati Times-Star, served a term in the U. S. House of Representatives for Ohio (1895-1897), and owned at separate times the Philadelphia Phillies and the Chicago Cubs baseball teams. He and his wife Anna Sinton Taft were also avid art collectors, and they lived in a mansion downtown.

Exit the theater’s lobby and head west a few blocks and you’ll run into Fountain Square, the epicenter of Cincinnati anchored by the magnificent Tyler Davidson Fountain (aka The Genius of the Water).

Head east instead and you’ll find the Taft Museum, the former personal residence now open to the public for displaying the family’s extensive art collection. In 1908, William Howard Taft accepted the Republican nomination for President from the front portico of this house:

In short, Dylan’s high-heeled boots were clicking on hallowed Cincinnati ground when he stepped onto the stage of the Taft Theatre.

Speaking of Bob’s boots, to my knowledge no bootleg recordings were made of this show. Nevertheless, we can piece together a wealth of information from the local press coverage. An ad printed two days before the concert notes that some proceeds from ticket sales would “raise funds for the John F. Kennedy campus leadership awards to needy Negro students at University of Cincinnati” (12). No setlist survives either, but the songs Dylan played in concert that spring seems to have been fairly stable. Presumably Cincinnati audiences in March were treated to much the same fare as English audiences in April and May. The lineup would have included some familiar protest songs like “The Times They Are A-Changin’,” “The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll,” and “With God on Our Side.” By this point Dylan was also introducing new songs from the unreleased Bringing It All Back Home. What a rare and unexpected privilege for fans to hear “Mr. Tambourine Man,” “It’s Alright, Ma (I’m Only Bleeding),” “Love Minus Zero / No Limit,” “Gates of Eden,” “She Belongs to Me,” and “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue” played live for the very first time, flashing like the chimes of freedom in the dark auditorium of the Taft.

James Wilber’s concert review for the Enquirer fills in details to help visualize Dylan’s performance. Consider his description of the interplay with guitar, harmonica, and audience:

Dylan had some technical trouble at the beginning of his show. His harmonica holder wouldn’t adjust correctly. After asking the audience if anyone had a harmonica holder (no one did) he decided to carry on. The harmonica causes quite a problem for Dylan. Since he uses both hands to play the guitar, the only way he can blow his harmonica is to have it attached to a contraption on his neck. To complicate things further, when he changes key with his guitar, he must remove the harmonica he has been playing, and pick up a harmonica which is in the correct key. For this purpose of key change, he keeps a collection of harmonicas at hand, within easy reach, on a stool beside him. (Wilber 43)

This account squares with scenes from Dont Look Back where Dylan tediously mucked about with his harmonicas, or the famous moment at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival when he called out to the crowd for an E harmonica and a shower of them rained in from the audience and rattled on stage. Wilber had a sharp eye for Dylan’s mannerisms, but he had a deaf ear for the songs. Like many reporters assigned to cover the young sensation, Wilber didn’t get the attraction.

Protest Songs is the label given the self-written prose recitations which Dylan gives. Except for some pointed reference to the Negro dilemma in the South, it is not always clear what Dylan is protesting. Nevertheless, his obscurity about what he is against is unimportant. His stream-of-consciousness rambling seems to get through to many persons in the audience. (43)

No wonder Dylan grew so weary with condescending journalists who cluelessly criticized what they couldn’t understand.

Dylan received a more sympathetic hearing from local legend Dale Stevens. In his book Lost Cincinnati Concert Venues of the ’50s and ’60s, Steven Rosen marvels at Stevens’s omnipresence on the Cincinnati entertainment scene: “Based on the sheer number of his bylines, I’m not sure Stevens ever slept. It is not uncommon to find several stories a day by him.” Rosen notes that, in addition to regular music columns across genres, Stevens also penned columns about food, theater, and especially film (Rosen 15). If something worthwhile was happening in Cincinnati entertainment, Stevens had the scoop on it. He published five pieces in the Cincinnati Post and Times-Star about Dylan’s two 1965 appearances. He was the young musician’s first champion in the local press, offering perceptive insights into Dylan as poet and performer. He was also a byproduct of his era and community, and at times these prejudices colored his views.

“Bob Dylan is a poet who sings,” proclaimed Stevens in the single-sentence first paragraph of his Taft concert review (21). He paid much closer attention to the songs than his counterpart at the Enquirer, and he admired what he heard: “He sings of cynicism, absurdity, rebellion and he does it completely without pretense or guile” (21). Even without a surviving setlist, we can infer several titles from Stevens’s enumeration of themes:

He sings his own songs, mostly uncomplicated not quite melodic melodies with remarkable lyrics which speak of friendship between races, an awareness of danger where The Bomb is concerned, the philosophy of war between peoples both of whom believe God is on their side, the more basic relationship between any boy and any girl, and the foolishness of money men on their way to heaven. (21)

Stevens also offered keen perceptions of Dylan as performer: “He laces much of his work with humor. Often he telegraphs his wit with a sheepish grin. He is not a performer in the show business sense; rather he offers his songs in the centuries-old style of the wandering troubadour” (21).

When I first encountered this review, I found myself nodding along, feeling as if I had found a comrade who responded to Dylan in performance much as I do. Until I read this: “He is girl-like in appearance: not effeminate in any way, but with fine, sensitive features and a shock of hair that makes the Beatles look bald” (21). Huh? Dylan is “girl-like” yet “not effeminate”? Just what are you insinuating, Dale Stevens? I’d like to give him the benefit of the doubt and credit him with tuning into Dylan’s androgynous, proto-Bowie sex appeal circa 1965, that irresistible pansexual allure that makes casting Timothée Chalamet as Dylan in A Complete Unknown as genius as casting Cate Blanchett in I’m Not There. [Listen to Laura Tenschert and Rebecca Slaman discuss this topic on Definitely Dylan.] Alas, I’m afraid that Stevens is simply viewing his shaggy subject through the filter of old-fashioned gender bias, throwing in emasculating jabs for the sake of a cheap laugh.

Setting aside the occasional retrograde remark, the review is on balance rapturous. The critic recognized why the young singer-songwriter was dubbed “the voice of his generation”: “Bob Dylan is unique, an individual who speaks for our conscience and his own and goes his own way apparently not caring if you like his odd looks or not” (21). Was Stevens getting in another dig at Dylan’s looks? Or was he mocking himself for dwelling upon such superficial details? Either way, there is no misinterpreting the full-throated endorsement at the end: “His stature in the field is earned and deserved. Once you see him, and hear him, you could never forget him. Just keep in mind that he’s a poet. Listen to his words” (21). Words do matter. Listen to Steven’s words, too.

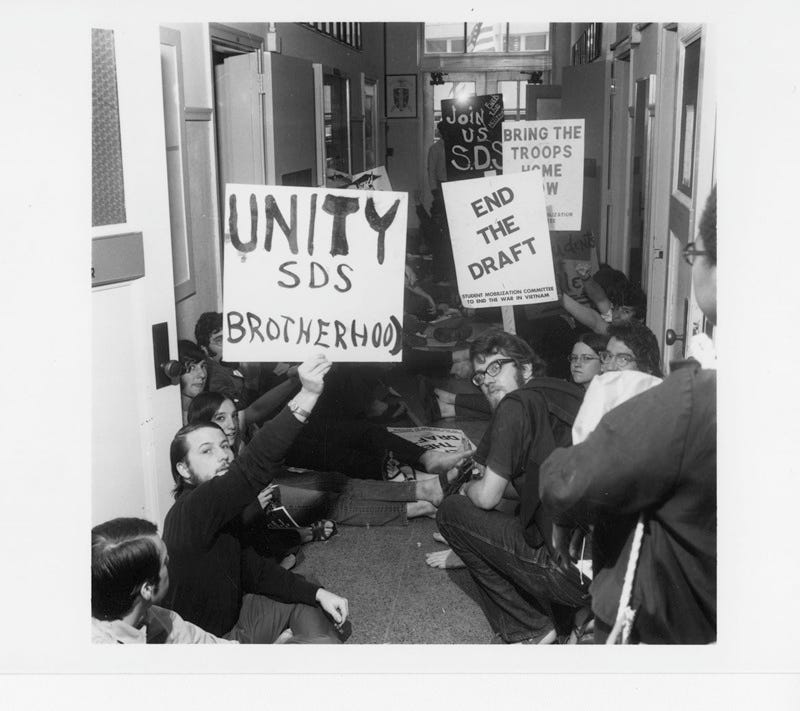

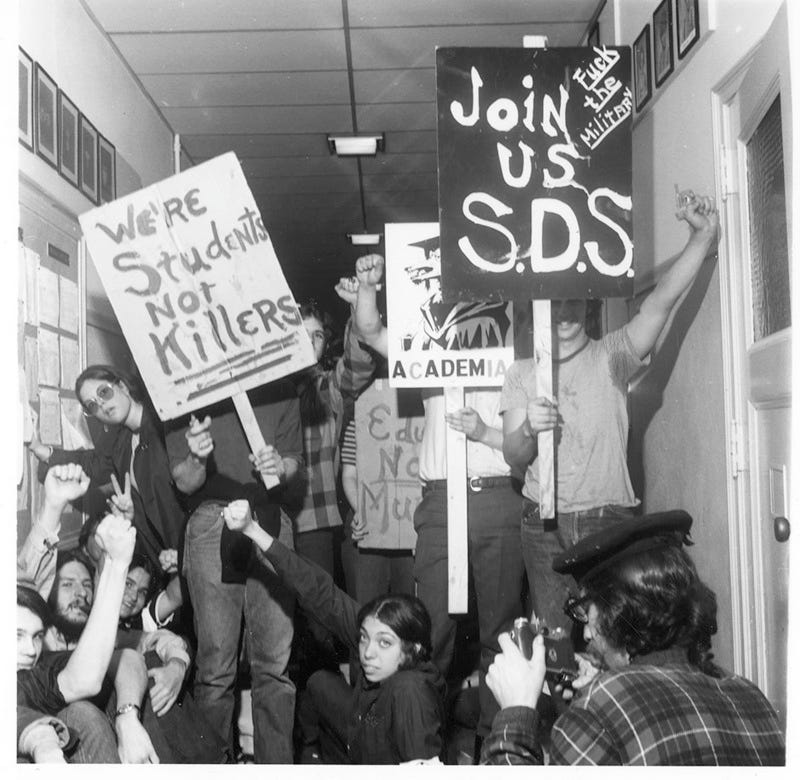

And then listen to the words of Mrs. Viel. No response to the Taft concert reveals more about the social and political climate of 1965 Cincinnati than a letter from Mrs. John Viel of Harrison. She attended the show and wrote to the Cincinnati Post and Times-Star to vent about what she witnessed there. Stevens printed her letter in his column the following week. Mrs. Viel (she never gives her first name) was convinced to go see what all the fuss was about by her husband, who dropped her off at the box office while he parked the car. Mrs. Viel immediately formed negative opinions based upon the shabbiness of the assembling crowd. Looking around the lobby, she wondered, “These are our students of today? Perhaps our leaders of tomorrow? The beards, the long uncombed hair, the dirty blue jeans . . . What has happened to the suit, white shirt and tie?” (31). Her problem with the crowd ran deeper than fashion. It was political:

The next step was the passing out of anti-Viet Nam literature. I doubt there were many there old enough to vote, but I listened to them express their idea of ‘idealism’ such as ‘I would rather commit suicide than serve my time in the service.’ Has patriotism suddenly become a dirty word to these youths? Where as people have we failed them? What do their parents think? Do they condone this style of dress? These ideas? These mixed dates? Or perhaps they just don’t care. (31)

Judge Schwartz couldn’t have said it better. Here was a damning display of teenage mystique turned public menace: kids growing their hair long, disregarding proper decorum, questioning the motives of authority and the policies of their government, rejecting patriotism as pretense for another foreign war, socializing (and god knows what else) with people outside their race (“mixed dates”!). One can only imagine what she thought when she heard Dylan sing: “Old lady judges watch people in pairs / Limited in sex, they dare / To push fake morals, insult and stare.” Something is happening here but you don’t know what it is, do you Mrs. Viel?

Mrs. Viel felt out of her element inside the auditorium just as she had in the lobby. Her commentary on the performance was brief: “Now to Bob Dylan . . . My husband thought he was tremendous. I did not care for him. Perhaps I do not have the mentality to understand such things” (31). Unlike Stevens, who found Dylan sincere and guileless, Mrs. Viel found him inaccessible and phony. But like Stevens, she fixated upon the ragamuffin’s unconventional looks:

Why does a good performer nowadays need a gimmick? With him it was the blue jeans, the skimpy jacket. Would this crowd, and I hope this is only a small portion of our youth, hold him in as much esteem if he took part of that nice fat fee and bought a suit, a white shirt, and a pair of shoes, plus, above all else, a haircut? (31).

Starring tonight in the role of Lady Bracknell . . . . Enough. To be fair, if I’m going to call out Stevens for being snide, then I should curb my own tendencies. Actually, I’m grateful to Mrs. Viel for giving me such an effective crash-course education. I did not live through these times and so can only access the climate of the times second-hand. In her own way, Mrs. Viel is an ideal spokesperson, the voice of her generation, defending the very values that Dylan and his supporters were so flagrantly defying.

Young fans were vocal in their opposition to Mrs. Viel. The following week Stevens published another column on Dylan and titled it “Students Come to the Defense of Bob Dylan.” This was the third piece by Stevens on Dylan in the Post in the span of ten days, showing what a lingering impact that first concert made in Cincinnati. Here Stevens included letters from readers objecting to Mrs. Viel’s misrepresentation of Dylan and his fans. Multiple readers rose in defense of Dylan, but I’ll cede the floor to Ellen Reinstatler of Oxford to speak for them all.

Although I respect Mrs. Viel’s opinion, I would like to defend myself, my ideals and the people whom she attacked. I am only 16 and, of course, I realize Mrs. Viel probably has more concrete reasons backing her opinion than I for mine. But I think perhaps I can see the situation more clearly than she. (20)

The Oxford teen apparently learned from Dylan how to walk a rhetorical tightrope between polite Midwestern deference (cf. “With God on Our Side”) and righteous indignation (cf. “Masters of War”). Reinstatler also echoed “The Times They Are A-Changin’”: “So many of today’s adults compare people such as Bob Dylan to performers of their own youth. This is their first mistake. The times have changed drastically with our generation and our performers change right along with them” (20). Reinstatler was particularly piqued by superficial judgments based upon physical appearances: “Beards, long straight hair, etc., seem to have become some sort of stigma to the adult world. This is such a pity because for this reason many brilliant minds will be wasted merely because some people don’t approve of their appearance” (20). On the contrary, “If people would seriously think about the things today’s folk singers sing of, many useful ideas of peace, equality and brotherhood might be discovered” (20). Reinstatler’s defense rests with this summation:

So to Mrs. Viel and the many other people who share her opinion—my parents, for example—I could like to suggest they at least once lift the veil between themselves and the younger generation and instead of looking, listen. I’m sure they won’t regret it. (20)

This war of words in the Cincinnati press reads like a dramatization of Dylan’s best-known anthem about generational conflict:

Come mothers and fathers

Throughout the land

And don’t criticize

What you can’t understand

Your sons and your daughters

Are beyond your command

Your old road is rapidly agin’

Please get out of the new one if you can’t lend a hand

For the times they are a-changin’.

Dylan essentially issued the same warning in the summer of 1965 but aimed at a different target audience. The Us vs. Them conflict got more complicated, as one faction of fans rejected the artist’s latest metamorphosis and ignited a mutiny within the ranks. More on that development in the next installment of the Dylan in Cincinnati series, where we’ll consider Dylan’s electric concert, backed by The Hawks, at the venerable Music Hall in November 1965.

Works Cited

“Bob Dylan Set.” Cincinnati Enquirer (10 March 1965), p. 12.

Dylan, Bob. Chronicles, Volume One. Simon & Schuster, 2004.

---. “It’s Alright, Ma (I’m Only Bleeding).” Bringing It All Back Home. Columbia, 1965.

---. “The Times They Are A-Changin’.” The Times They Are A-Changin’. Columbia, 1964.

---. “Tombstone Blues.” Highway 61 Revisited. Columbia, 1965.

Faithfull, Marianne, with David Dalton. Faithfull: An Autobiography. Cooper Square, 2000.

“Inside Cincinnati: Lack of Schooling, Sloth Blamed in Stenographer Shortage,” Cincinnati Post and Times-Star (12 March 1965), p. 1.

Herren, Graley. “Come You Whiffenpoofs of War.” The Dylantantes (22 November 2022).

Hine, Thomas. The Rise and Fall of the American Teenager. Perennial, 1999.

Marshall, Lee. Bob Dylan: The Never Ending Star. Polity, 2007.

Miles. Interview with Patti Smith (18 March 1977). Wanted Man: In Search of Bob Dylan, edited by John Bauldie. Citadel Press, 1990.

Rosen, Steven. Lost Cincinnati Concert Venues of the ’50s and ’60s: From the Surf Club to Ludlow Garage. The History Press, 2022.

Stevens, Dale. “Bob Dylan: The Poet Who Sings.” Cincinnati Post and Times-Star (13 March 1965), p. 21.

---. “The Readers: ‘Greatest Story,’ Dylan,” Cincinnati Post and Times-Star (17 March 1965), p. 31.

---. “Students Come to the Defense of Bob Dylan.” Cincinnati Post and Times-Star (23 March 1965), p. 20.

“Teen-agers Revel in Madness: Young Fans Drop Veneer of Civilization.” Cincinnati Enquirer (28 August 1964), p. 1.

Tenshcert, Laura and Rebecca Slaman. “Will Timothée Chalamet Save Dylan Fandom?” Definitely Dylan (24 May 2022).

Wald, Elijah. Dylan Goes Electric! Dey St., 2015.

White, Gerald. “Involvement Is the Key: Today’s Student Fight for Causes.” Cincinnati Enquirer (7 March 1965), p. 4-F.

Wilber, James. “Dylan’s Music of Protest,” Cincinnati Enquirer (15 March 1965), p. 43.

Grassy - from that incredible video of the judge (I saw the Beatles in Chicago that year) through the description of the reactions to Dylan’s performance this is terrific. It paints such a picture of the disruption that music was making.