Dylan Context

From the outside looking in, it may have seemed that Dylan was on his farewell tour in the late eighties. After an enthusiastic but erratic run of concerts with The Grateful Dead in the summer of 1987 and with Tom Petty & The Heartbreakers in the fall, Dylan was inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in January 1988. It seemed the fitting culmination of an historic career. A subpar compilation of live tracks was released the following year as Dylan & The Dead, notoriously the worst album that either act ever produced. In May he put out the latest in a string of poorly received records, Down in the Groove. According to Derek Barker, founding editor of the fanzine ISIS, “A more appropriate title would have been ‘Down in the Dumps’” (Barker 371). Dylan had a good run, but the view from the bleachers suggested an irrelevant rocker past his prime, out of gas and coasting on fumes toward the finish line.

This conventional wisdom now seems dead wrong. For too long, the eighties have been maligned as an artistic wasteland for Dylan. Even with the recorded material available to the general public at the time, this was an unfairly stern judgment. But especially in light of two amazing installments of The Bootleg Series, Trouble No More 1979-1981 (Vol. 13) and Springtime in New York 1980-1985 (Vol. 16), it is becoming hard to ignore or refute how creatively rich Dylan’s work was during the decade. The enthusiastic response to Erin Callahan and Court Carney’s roundtable at the World of Bob Dylan 2023 conference, “‘Where Beauty Goes Unrecognized: Reconsidering Bob Dylan in the 1980s,” shows that the critical winds are shifting directions toward a positive reassessment. I regard the present chapter as part of that revisionist movement. Dylan felt alienated in many ways from the music business and the dominant cultural climate of Reagan-era America, but it didn’t prevent him from producing substantial and lasting work during this period. He also devised plans for something even more ambitious.

Late in 1987, Dylan began to conceive a new approach to touring. He recalls in Chronicles,

I saw that instead of being stranded somewhere at the end of the story, I was actually in the prelude to the beginning of another one. I could put my decision to retire on hold. It might be interesting to start up again, put myself in the service of the public. I also knew that it would take years to perfect and refine this idiom, but because of my fame and reputation, the opportunity would be there. It seemed like the right time for it. (153-54)

This tour would be different. After playing with large ensembles in the late seventies and early eighties, and then attaching himself to pre-existing bands with their own fan bases in the Dead and the Heartbreakers, Dylan decided to form his own lean and mean squad of road warriors and start over. He hatched a plan for rejuvenating his fan base through regular, strategically scheduled concerts. He told tour manager Elliot Roberts “to book a similar amount of shows in the same towns the following year and also the year after that—a three-year schedule of more or less the same towns. I figured it would take me at least three years to get to the beginning, to find the right audience, or for the right audience to find me” (154). Sure enough, Dylan played Cincinnati in both 1988 and 1989, and played fifty miles up the road at Dayton in 1990. Roberts was skeptical of saturating these local markets, but Dylan insisted. The blueprint was established for what would become the Never Ending Tour (NET).

Roberts volunteered to recruit the right band for such a venture. In a lengthy interview with Adrienne Faillace for the Archive of American Television, guitar virtuoso G. E. Smith recounted the origin of the first NET lineup.

Smith was a celebrity in his own right in 1988 as the flamboyant leader of the Saturday Night Live house band. When it came to Dylan, however, he was a giddy fanboy. He told Faillace, “When I was a kid, going to St. Matthew’s grade school, I would carry Bob Dylan records around so that people would see them. I wanted people to see that. His first ten albums probably, I knew every word, could play all the parts, everything, knew the stuff inside out.” Familiar with his devotion, Roberts invited Smith to bring a couple guys and come play with his hero at Montana Studios in November 1987. He arrived with two SNL bandmates, drummer Chris Parker and bassist Tom “T-Bone” Wolk. And they waited.

“We were nervous,” Smith recalled. “I can’t compare his iconic stature to anyone now similar in music to what Bob meant. They had put that thing on Bob, which I later talked to him about, ‘the savior of a generation.’ He was the guy who influenced The Beatles. He was the guy. The whole ’60s, ’70s thing, Bob invented that.” Eventually Dylan arrived at the studio, plugged in, and started tooling around, but with no apparent agenda or direction. Drummer Chris Parker told Ray Padgett, “I had the gall at one point to say, ‘What do you want me to play on this?’ Bob said, ‘I’m just a fucking poet.’” According to Smith, “After maybe a half hour of that, I’m thinking, you know, this is not going well here. I don’t know what it is he wants to do.” Eventually Dylan approached Smith and Wolk and asked if they knew “Pretty Peggy-O,” a folk song Dylan covered on his debut album. “We both, like twins, go ‘Sure!’ He goes, ‘You do?’ Well, yeah, we know ‘Pretty Peggy-O,’ of course we know ‘Pretty Peggy-O.’ That’s who we are: we’re the guys who know ‘Pretty Peggy-O’!” They started playing the song, it sounded good, and they were off: the night rebounded from down in the dumps to down in the groove.

Roberts called Smith the next day and informed them that they got the gig as Dylan’s road band—a job they hadn’t even known they were auditioning for—because they passed the “Pretty Peggy-O” test. Wolk had scheduling conflicts and declined the invitation, so he was replaced on bass with Kenny Aaronson.

With a tight four-piece unit in place, the band rehearsed through the spring and played their first show before an audience on June 7, 1988, in Concord, California. No one could have anticipated the epic scope of this new undertaking. Dylan and an evolving lineup would continue to tour from 1988 onward, usually playing about a hundred shows every year, until Covid forced an end to the Never Ending Tour after 31 years and 3,000+ concerts. Thirteen of those shows took place in the Cincinnati metropolitan area, starting with the tenth NET concert on June 22, 1988, at Riverbend Music Center.

Cincinnati Context

Both the Enquirer and the Post led with stories about the oppressive heat wave suffocating the region. Daily temperatures were hovering near 100° F (38° C)—not the best conditions for Dylan’s first outdoor concert in the city. The other big local news was an event dubbed “Unity ’88.” President Ronald Reagan was completing his second and final term, and the Republican primaries pitted several rivals to succeed him as standard bearer for the party. By June the presumptive nominee was Vice President George H. W. Bush, and his former competitors were lining up support ahead of the Republican National Convention in August. Toward that end, party leaders staged “Unity ’88” at the Clarion Hotel in downtown Cincinnati. Ohio was considered a key to Bush’s success in the November election. He went on to win the state and the general election by a wide margin to become the 41st President of the United States. An interesting piece of trivia: no Republican candidate has ever been elected President without winning the state of Ohio.

The temperature was still near 90° F (32° C) when Dylan and his new band took the stage at Riverbend Music Center. The venue is a large outdoor amphitheater, located beside the Ohio River in suburban Anderson Township. Since its opening in 1984, Riverbend has played host to countless big acts on the annual summer touring circuit. Like many such venues, Riverbend consists of a covered seating area close to the stage, and beyond that an open grassy hillside where fans attend picnic style. The total capacity in the reserved seating area is 6,000, and the general admission lawn area accommodates another 14,500. About 9,000 fans showed up for the 1988 concert at Riverbend; by comparison, that’s 8,000 less than the crowd at Riverfront Coliseum downtown a decade earlier. The size of the band and the length of the setlist were also cut in half. But those lucky fans who braved the heat for the Riverbend ’88 show were treated to one of the best concerts Dylan ever performed in Cincinnati.

The Concert

When: June 22, 1988

Where: Riverbend Music Center in Anderson Township

Opener: The Alarm

Band: Bob Dylan (vocals and guitar); Kenny Aaronson (bass); Christopher Parker (drums); G. E. Smith (guitar and backup vocals)

Setlist:

1. “Subterranean Homesick Blues”

2. “Ballad of a Thin Man”

3. “Silvio”

4. “My Back Pages”

5. “Clean-Cut Kid”

6. “All Along the Watchtower”

*

7. “Wild Mountain Thyme”

8. “The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll”

9. “Barbara Allen”

*

10. “I’ll Be Your Baby Tonight”

11. “You’re a Big Girl Now”

12. “Stuck Inside of Mobile with the Memphis Blues Again”

*

13. “It Ain’t Me, Babe”

14. “Like a Rolling Stone”

Dylan’s 1978 setlist at Riverfront Coliseum consisted of 27 songs, and his previous 1981 concerts at Music Hall contained 30 and 26 songs respectively. He only played 14 songs at Riverbend ’88—but he played the hell out of them. The other thing that may not come across when viewed in isolation, but becomes immediately clear when viewed in aggregate, is how remarkably diverse Dylan’s setlists were in the summer of 1988. True, he only played 14 songs on June 22 in Cincinnati—but 10 of the 14 were different from his setlist the night before in Cuyahoga Falls, Ohio. And at his next show on June 24 in Holmdel, New Jersey, he played 10 different songs from those in Cincinnati. Ah, those glorious early days of the NET! You truly never knew what you were gonna get.

First Electric Set

Riverbend ’88 opens with a glorious performance of “Subterranean Homesick Blues.” This is one of Dylan’s classic songs, but astoundingly Dylan had never played it live until a couple weeks prior. This Cincinnati rendition was only his tenth performance ever. What a wild ride! The band comes roaring out of the gate like thoroughbreds next door at River Downs, the horse track adjacent to the amphitheater.

“Subterranean Homesick Blues” is a verbally demanding choice for opening number, but Dylan’s voice is in great shape tonight and equal to the challenge. No opening jitters or stumbles from the boss or his band tonight. Dylan sets a tone with this opener, announcing: “Now hear this, Cincinnati—the stuff we’ve got will bust your brains out!”

Enquirer music critic Cliff Radel received the message loud and clear. I haven’t always seen eye to eye with Radel in his previous reviews, but we both hear the same excellence from this performance. “The crowd of 9,076 saw one of those shows that people talk about, but rarely hear anymore,” Radel proclaimed. “Each song sounded new. Every time Dylan had a chance to alter a melody, he took it. From the very first notes of ‘Subterranean Homesick Blues,’ you knew this was not going to be one of those nights where each song would be a dull duplicate of its recorded version. By pouncing onto each line of his vocal, Dylan turned his talking homesick blues into a kick-in-the-slats rocker” (D-3).

“Subterranean Homesick Blues” led off every concert that summer, but then it was anybody’s guess what would come next. On this night the Riverbend crowd is treated to “Ballad of a Thin Man,” featuring a spectacular Dylan vocal. If you want an ideal example of how rededicated he is to live performance, listen to this “Ballad of a Thin Man.”

He’s ferocious! His delivery has all the drive of the 1966 electric shows but without the drug-addled exhaustion. I was a bit worried going in that the outdoor setting might swallow some of the sound, but nothing of the sort. The bootleg (LB-6085) by “Legendary Taper D” is pristine and sounds soooo good. I absolutely love it, and you can hear that the audience does, too. I only have audio evidence to judge by, but Larry Nager, music critic for the Post, was there and lends visual confirmation: “it was during the electric songs that Dylan—usually withdrawn and uncomfortable-looking onstage—really came alive, grinning and bobbing to the music” (9B). The new band still had rough edges, but Nager felt this edginess only added to the appeal: “that’s how Dylan seems to like it—spontaneous, with plenty of room for magic or mistakes” (9B).

The third song is a fun jam on “Silvio,” co-written with Grateful Dead lyricist Robert Hunter. It was released in May 1988, making it the newest song in the setlist. In fact, Dylan had just debuted the song the night before in Cuyahoga Falls, so Riverbend ’88 was only the second live performance ever. Parker and Aaronson provide a driving beat, and Smith shreds it on his solos. Dylan’s vocal is delightfully infectious. Even if you had never heard the song before—surely the case for many in the audience that night—you can’t help but pick up on the dynamism and begin singing along.

Playing with the Dead was a pivotal experience in Dylan’s recommitment to playing live. He admits in Chronicles that he had lost touch with the spirit of his music by the mid-eighties. Ironically, given their name, the Dead helped Dylan come back to life. They resuscitated his flagging passion and reconnected him to his artistic fountainhead. That’s basically what the song “Silvio” is about. “Stake my future on a hell of past”—what a great opening line! It could serve as the motto for the whole NET. The tour wasn’t about burnishing celebrity or lining pockets. As the refrain puts it,

Silvio

Silver and gold

Won’t buy back the beat of a heart grown cold

Silvio

I gotta go

Find out something only dead men know

It ain’t about silver and gold. It’s about taking your music to the people and sharing a unique live experience, night after night in town after town. The Dead had known it all the time, and Dylan was relearning it these days.

“Silvio” is often dismissed as doggerel by Dylanologists. Nay-sayers greet it with disdain whenever it appears in setlists. Dylan clearly likes playing the song, however, having performed it in concert nearly 600 times. Paul Williams poses the direct question “Why does Dylan like it?” and offers a convincing answer: “He likes the response it often gets from his live audience (not because they’re familiar with the song, but because the dynamics of the song’s music and Dylan’s enthusiasm for it as singer and bandleader tend to make it an exciting and satisfying musical experience even though it’s not one of the Dylan songs the audience members were coming to hear tonight)” (35). Williams speculates that the relatively minor status of “Silvio” is part of Dylan’s attraction: “he feels liberated by the fact that it’s a Dylan song without baggage; he and the band play it as though it were a big hit or a song that made him famous, and the audience can feel that and respond happily without knowing what song this is . . . which allows the singer to lean into it in a way that’s different from the other Dylan songs and covers he’s playing” (35). Spot-on as usual, Mr. Williams. That is precisely what comes through when listening to this 1988 rendition, the first of four consecutive Cincinnati concerts where Dylan belted out the heart-warming, rump-shaking “Silvio.”

For a good illustration of the wonderful unpredictability of the NET setlists, check out the deep cut Dylan dials up for his fifth song: “Clean Cut Kid.” Riverbend ’88 was the only time he played the song in his 71 concerts that year. In fact, he would only play it one more time ever, two years later and two-hours’ drive north in Columbus. This penultimate rockabilly rendition sounds superb, with distinct flavoring from Elvis Presley’s “All Shook Up.” This live version is so much better than the track that appears on the overproduced 1985 album Empire Burlesque.

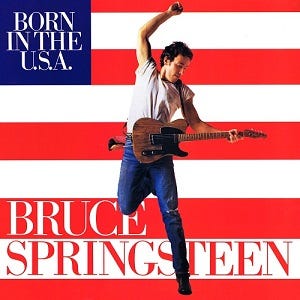

“Clean Cut Kid” strikes me as a cousin to Bruce Springsteen’s “Born in the U.S.A.” Both songs consider the human toll war takes on veterans, and both conceal their social critique inside heart-thumping rock. Springsteen’s 1984 song was notoriously hijacked by the Reagan campaign as a patriotic anthem, when in truth it is a song about a downtrodden Vietnam War veteran who can’t catch a break back home. The singer isn’t bragging about being born in the U.S.A., quite the opposite. He feels bitter and betrayed, promised the American Dream but sold a bill of goods.

Dylan’s 1985 song focuses on a similar subject and reaches the same conclusion: “He was a clean-cut kid / But they made a killer out of him / That’s what they did”; “He bought the American dream but it put him in debt / The only game he could play was Russian roulette” [shades of Christopher Walken’s character in The Deer Hunter]; “Everybody wants to know why he couldn’t adjust / Adjust to what, a dream that bust?” [cf. Springsteen’s “The River”: “Is a dream a lie if it don’t come true / Or is it something worse?”]. We’ll never know why Dylan decided to play “Clean Cut Kid” on this particular night in Cincinnati and nowhere else on the tour. But I wonder if he read the local papers that day and saw that Reagan’s VP, decorated World War II veteran, and the next Republican nominee for President, George H. W. Bush, was passing through Cincinnati. While party power brokers were staging a rally around the flag downtown at the Clarion, Dylan issued a very different clarion call up river, exposing the debilitating costs of patriotic zeal, when a clean-cut kid is given a license to kill.

Dylan and the band mash the pedal to the floor on the sixth song, “All Along the Watchtower.” This one frequently provides a jolt in concert, and that’s certainly true tonight. Music lovers beyond Dylan World think first of Jimi Hendrix’s bewitching cover of this song. No one can out-hoodoo Hendrix on guitar, but G. E. Smith holds his own with some killer licks on this number. I love Dylan’s vocal delivery, too.

As written, the song works on multiple levels, with scriptural allusions (cf. the fall of Babylon in Isaiah 21), an archetypal pair of doppelgangers (the Joker and the Thief), and an experiment with circular time (the two riders approaching at the end mark the Joker and Thief’s arrival). On its most primal level in performance, as Dylan reminds the Cincinnati audience on this balmy summer night, the song is an extended howl.

Acoustic Set

Dylan then transitions into a middle acoustic set, a cherished feature of the NET for many years. The acoustic set regularly showcased some of Dylan’s most memorable performances of traditional songs. On this hallowed evening, he blessed the Cincy crowd with a spellbinding rendition of the Scottish-Irish air “Wild Mountain Thyme.” This song holds a special place in Dylan lore. His first recorded performance was in 1961 at the Minnesota home of Bonnie Beecher, and he played it with Joan Baez in 1965 at London’s Savoy Hotel. His next known performance was at the Isle of Wight Festival in 1969. He played the song seven times during the Rolling Thunder Revue (1975-76), often in duet with Baez. But he hadn’t played it live since then—until he summoned “Wild Mountain Thyme” like a genie from his bottle on June 22, 1988. He has never played it in concert again.

What a precious gift Dylan gives Cincinnati by delivering his final performance at Riverbend. His tender vocal is achingly beautiful, and the acoustic guitar playing (accompanied by Smith) is sublime. I was moved to tears the first time I heard it, and it’s one of my motivations for writing Dylan in Cincinnati. The singer has contributed so much to my personal and professional life and to the civic life of my adopted hometown. I want to reciprocate with a gift of my own, sharing what makes these Cincinnati concerts special and shining a light on Dylan performances like this one that deserve wider recognition.

In his 2022 book The Philosophy of Modern Song, Dylan declares, “Knowing a singer’s life story doesn’t particularly help your understanding of a song. It’s what a song makes you feel about your own life that’s important” (9). I personally associate “Wild Mountain Thyme” with my many trips to Ireland teaching in Xavier University’s study abroad program. Whenever we went out west, we spent as much time as we could with Gerry Joyce.

Gerry is a man of many talents: thatcher, architect, naturalist, raconteur, walking encyclopedia of folk songs, and a big Dylan fan. We’d always arrange a lunch with the students at Gerry and Mary Graham’s lovely place in Letterfore, and afterwards he’d pull out his guitar and treat us to some tunes. For my sake, he’d always play “Girl from the North Country,” the Nashville Skyline version, delighting us with impressions of Dylan and Cash. There’d be plenty of Irish rebel ballads, too. But the highlight for me was always his stirring rendition of “Wild Mountain Thyme,” the song he performed at his daughter’s wedding. Dylan’s Riverbend ’88 performance is pure and sparkling as a mountain stream, and it leads back to the purple heather of other times and places. Listening to the bootleg, I am transported back to those golden afternoons in the hills of Connemara. Thyme Out of Mind.

Other listeners have different associations, as you can hear from the audience reactions captured on tape. A few lines into the song a woman near the taper yelps: “This is a Joan Baez song!” Well, the song dates back much further than that, but she’s not wrong. During a musical interlude before the final chorus, an audience member with a distinctly Southern accent loudly marvels: “That’s bad as hell!” Indeed it is, my virtual seatmate. And he ain’t done yet.

If forced to choose Dylan’s single greatest protest song, I’d have to pick “The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll.” Based upon true events, though rendered with considerable poetic license, the singer tells the story of a young, wealthy, privileged owner of a tobacco farm, William Zanzinger, who struck a poor kitchen maid, Hattie Carroll, with a blow that contributed to her death. We’re told that the assailant was arrested for first-degree murder, but he is ultimately given a slap on the wrist with a six-month sentence. Some of Dylan’s protest songs are filled with righteous indignation or preachy moralizing. However, “The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll” takes a more measured approach. Dylan lays out certain key facts about the case—or at least one version of the facts—and then invites listeners to draw their own conclusions about inequities and injustices in the American legal system of the early 1960s.

As Christopher Ricks notes in Dylan’s Visions of Sin, the songwriter’s strength lies as much on what he omits as what he includes: “The song never says she’s black, and it’s his best civil rights song because it never says she’s black. . . . But then you know that Zanzinger is white, though it never says this either. It’s a terrible thing that you know this from the story, and from the perfunctory prison sentence, even while the song never says so. It’s white upon black, it’s man upon woman, it’s rich upon poor, it’s young upon old” (231). The song isn’t just an indictment of Zanzinger but of the systemic racism of the society that produced him. Dylan doesn’t waste a word, letting us fill in the gaps with our own sad knowledge of that society, before handing down a verdict that speaks for itself.

“Wild Mountain Thyme” was a total wildcard, but “The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll” was one of those beloved songs from “the voice of his generation” that many fans came out hoping to hear. The proof is clearly audible on tape. Once Dylan begins singing the first line, he is greeted with jubilant cheers of gratitude. You can also pick up on the crowd singing along with the chorus, a practice Dylan often undermines in performance but tonight indulges.

Something else really strikes me in this performance of “Hattie Carroll.” The song is driven by an insistent cadence, and this rhythm is dictated by Dylan’s distinct breathing pattern as a singer. If “Watchtower” is a howl, then “Hattie Carroll” is a pant. As the song builds toward the climax, the verbal units get shorter and the breaths come quicker. The singer expresses viscerally the anxiety and panic that the songwriter declines to articulate verbally. In 1988 Dylan contributed an essay to a traveling exhibit on Jimi Hendrix; my thanks to Paul Williams for pointing this piece out and quoting it at length. Dylan notes that “my songs were not written with the idea in mind that anyone else would sing them, they were written for me to play live” (qtd Williams 122). He lists multiple challenges posed by the songs, but the one I find most intriguing is his emphasis upon breathing: “my songs are different & i don’t expect others to make attempts to sing them because you have to get somewhat inside them & it’s hard enough for me to do it sometimes & then obviously you have to be in the right frame of mind. but even then there would be a vague value to it because nobody breathes like me so they couldn’t be expected to portray the meaning of a certain phrase in the correct way without bumping into other phrases & altering the mood, changing the understanding” (122).

Interestingly, Cis Berry, longtime voice director for the Royal Shakespeare Company, stressed the same thing in training actors, highlighting the intimate link between breathing and thought. In her book The Actor and the Text, she asserts, “We have to see the breath not simply as the means by which we make good sound and communicate information; but rather we have to see it as the physical life of the thought, so that we conceive the breath and the thought as one. We need to be able to encompass one thought with one breath” (26). Berry tells performers:

We also see that how we share the breath is how we share the thought. If we waste the breath, we disperse and generalize the thought; and, conversely, if we hold on to the breath in some way, we reduce the thought by holding it back and locking it into ourselves. But, more important than this, we perceive that how we breathe is how we think; or rather, in acting terms, how the character breathes is how the character thinks. (26)

If you want to hear an example of the integration of breathing and thought, listen to Dylan’s Riverbend ’88 performance of “Hattie Carroll.” He doesn’t have to spell out his views on this travesty of justice in words; he communicates it forcefully through his panting vocal delivery. He’s practically hyperventilating by the time he delivers the shameful verdict.

The final song of the acoustic set is an exquisite “Barbara Allen.” This celebrated Child Ballad rang out nightly in the clubs and coffeehouses of Greenwich Village when Dylan arrived on the scene. His first known public performance was at the Gaslight Café in 1962. He didn’t play it in concert again for 19 years, busting it out at Earl’s Court in London in 1981. Riverbend ’88 was only the sixth registered time he performed it live, though it’s a safe bet he played this classic off the radar at plenty of impromptu hootenannies and late-night loft parties. Barbara Allen!

What a treasure the Cincinnati audience received that night, and how lucky we are that “Legendary Taper D” captured moments like this to share with the rest of us. The most dedicated chronicler of the NET, Andrew Muir, singles out this song as a recurring highlight of the tour’s first leg: “‘Barbara Allen,’ played in a variety of ways, was a regular standout. I swear that on some nights the way he sang the words ‘Oh yes oh yes, I’m very sick, and I will not be better’ was worth the admission price alone” (37).

The new band rehearsed an extensive catalogue of songs in the spring of 1988 to prepare for the summer tour. Paul Williams keenly observes that Dylan “paid uncharacteristic attention to songs he was singing at the very start of his career” (149). It’s true. “Wild Mountain Thyme” and “Barbara Allen” are two cases in point from Riverbend ’88, but other concerts included “Man of Constant Sorrow,” “Baby, Let Me Follow You Down,” “Pretty Peggy-O,” “Song to Woody,” etc. Williams is definitely onto something when he writes, “We can infer that Dylan in spring ’88 devised a strategy for ‘getting back there’ to the meaning of his own work without emergency assistance from Jerry Garcia” (150). At so many crucial junctures in his career, Dylan recharged his creative batteries by playing beloved covers, following their lead back to a place where he could produce meaningful original work again. This regenerative process had a healing effect in 1988, as his major new album Oh Mercy would soon affirm in 1989. But let’s not get ahead of ourselves. We still have the second electric set and encore at Riverbend ’88 to go.

Second Electric Set & Encore

The standout from the second electric set is “You’re a Big Girl Now.” When the band started playing, I couldn’t identify the tune at first, a common experience at a Dylan concert.

From the first time I heard the bootleg, the opening notes sounded familiar, and after repeated listening it finally occurred to me what I was hearing: “Heart and Soul” by Huey Lewis and The News! Absurd, I know, and surely coincidental. But listen to the opening riffs of both songs back to back and I bet you’ll hear it, too.

The mystery is revealed when Dylan sings the first verse and launches into “You’re a Big Girl Now,” one of his emotionally bloodiest tracks from Blood on the Tracks. G. E. Smith contributes perfect guitar fills and a brief but piercing solo. He is a seasoned bandleader capable of showing off, as SNL showcased weekly. Most of the time he curbs his diva impulses on this tour, however, content to take whatever share of the spotlight Dylan cedes him. If Dylan is the quarterback of Team NET, then Smith is his quality running back, waiting for his number to get called in the huddle and a gap to open in the line. When his turn comes, he takes the handoff and hits the hole.

Ever since Blood on the Tracks was released in 1975, it was hailed as one of Dylan’s finest. Over the years, Dylan has displayed a wayward devotion to these songs, performing several of them frequently in concert, but also significantly revising the lyrics and arrangements. Rather than suggesting dissatisfaction with the Blood on the Tracks songs, Dylan’s evolving approach to these songs is testimony to their enduring strength and malleability. He trusts these songs to be effective in a number of different registers and guises. On the album version, “You’re a Big Girl Now” exposes the singer at his most decimated, especially when he repeatedly wails “ooooh!” midway through each verse. The keening is absent from this 1988 performance. Dylan starts in a melancholy mood, but the vibe gradually shifts from vulnerable to pugnacious. On Blood on the Tracks, the singer admires his ex for moving on more successfully than he has; i.e., if only I could be a big girl like you instead of breaking like a little boy. At Riverbend ’88, he sings a different tune, stabbing out the lyrics as if he means to cut this “big girl” down to size. Same words—different song.

After mixin’ up the medicine for only an hour, Dylan and the band leave the stage, having played only twelve songs. In 1978 and 1981, the shows were less than halfway through at that point. The quantity of songs may be comparatively low, but the quality of performances was remarkably high. Thankfully, the foursome returned for two more crowd-pleasers in the encore. First up is a lovely acoustic version of “It Ain’t Me, Babe.”

No trouble recognizing this tune: the crowd applauds loudly, then listens with rapt attention until each chorus, when they sing along in unison with Dylan. He delivers his vocal like a heavyweight champ with his opponent on the ropes, landing one bruising body blow after another: “It ain’t ME babe! / NO NO NO, it ain’t ME babe! / It ain’t me you’re lookin’ FOR babe! / It ain’t ME you’re LOOKin’ FOR!”

For us bootleg listeners who weren’t there in person to witness it, Smith vividly describes the NET setup for acoustic numbers:

There was a spot on Bob. The rest of the stage is black, just one spot. A circle around him, from about ¾ front, so it’s hitting him in the forehead. So he’s got those deep shadows. Beautiful lighting. Casts a nice shadow behind him. I’m just on the edge of that circle of light, to his right, so I could watch his hands to see where he’s going. Because Bob didn’t really tell you what he was going to do. And I’m really out of the light. My face is out of the light, but my guitar is in the light. So they can watch my hands if they want to, but it’s not about me, it’s about Bob. That’s the way it should be. And we would just do anything. Whatever he wanted. He would just play any song. And I love that ‘seat of the pants’ thing for myself, just following people. (Faillace)

Paul Williams has an interesting take on how and why the double-guitar arrangement worked so effectively in the middle set and the acoustic numbers in the encore:

G. E. Smith’s role in this, although his playing as second guitarist in the acoustic sets was skillful and tasteful, often intelligent and always appropriate, seems to have been primarily to boost Dylan’s confidence by taking away the possibility that he would make a very audible mistake in his guitar playing, a possibility that would have worried him and made it difficult for him to be as present in his singing during the “solo” sets as he needed and wanted to be. Because of this new two-guitar format, and Dylan’s confidence in Smith’s ability to “cover” him, Dylan was able to be more ambitious in the songs he chose to play and sing, and to set higher goals for what he hoped to achieve, musically and emotionally, during this part of the show. (144-45)

Perhaps it is presumptuous for Williams to speculate on Dylan’s insecurities on stage, but his points resonate with certain sentiments expressed in “It Ain’t Me, Babe”: “You say you’re lookin’ for someone / Who’ll pick you up each time you fall.” Whatever the motive, there’s no arguing with the results, which are consistently daring, musically and emotionally, as Williams rightly observes.

How to close this outstanding concert? Oh, might as well play the greatest rock song of all time: “Like a Rolling Stone.”

Dylan really belts out his vocals, yelling the famous chorus like he’s strapped to the mast in a hurricane. “HOW does it FEEEEL! / HOW does it FEEEEL! / To be WITHout a HOME / With no diRECtion HOME / Like a comPLETE unKNOWN / Like a ROLLin’ STOOOOONE!” I’m not surprised that he placed this song last in the setlist because there’s no place left for his voice to go after issuing this roar. The crowd is whipped into a frenzy throughout this closer, and indeed for much of the concert. There must have been a lot of raspy voices to go along with the smiling faces as fans staggered happily back to the parking lot.

For anyone keeping score, the majority of songs Dylan sings at Riverbend ’88 were written and recorded in the 1960s—9 out of 14. And yet this concert certainly doesn’t come across as a nostalgic oldies revue by a has-been troubadour resting on his laurels. Most of the older songs are reimagined through new arrangements, and all of the performances are animated by Dylan’s renewed enthusiasm and his kick-ass band. In short, he had rediscovered his mojo. As luck would have it, he returned to play the same venue the very next summer. For more on Riverbend ’89, stay tuned for the next installment of Dylan in Cincinnati.

Works Cited

Barker, Derek. The Songs He Didn’t Write: Bob Dylan Under the Influence. Chrome Dreams, 2008.

Berry, Cicely. The Actor and the Text, revised edition. Applause, 1992.

Dylan, Bob. Chronicles, Volume One. Simon & Schuster, 2004.

---. Official Song Lyrics. The Official Bob Dylan Website,

http://www.bobdylan.com/

.

---. The Philosophy of Modern Song. Simon & Schuster, 2022.

Faillace, Adrienne. Interview with G. E. Smith (5 October 2015), Television Academy Foundation, https://interviews.televisionacademy.com/interviews/ge-smith?clip=66981#interview-clips.

LB-6085. Bootleg Recording. Legendary Taper D. Riverbend Music Center, Cincinnati (22 June 1988).

Muir, Andrew. One More Night: Bob Dylan’s Never Ending Tour. CreateSpace, 2013.

Nager, Larry. “Dylan Legend Works Its Magic at Riverbend.” Cincinnati Post (23 June 1988), 9B.

Padgett, Ray. “Drummer Christopher Parker on the Start of Bob Dylan’s Never Ending Tour,” Flagging Down the Double E’s (26 September 2021),

.

Radel, Cliff. “Bob Dylan gives masterful new kick to a night full of old hits.” Cincinnati Enquirer (23 June 1988), D-3.

Ricks, Christopher. Dylan’s Visions of Sin, Ecco, 2003.

Springsteen, Bruce. “The River,” Springsteen Lyrics, https://www.springsteenlyrics.com/lyrics.php?song=theriver.

Williams, Paul. Bob Dylan, Performing Artist, 1986-1990 & Beyond: Mind Out of Time. Omnibus, 2005.

Bravo, Graley! That was an insightful and inspiring analysis of Dylan’s 1988 show in your beloved home city. Your thoughts on “Silvio” may influence some of the naysayers. I am looking forward to the next installment and, ultimately, the entire book.

“That’s bad as hell!” What a precise evocation of a stunning set. I'm still not sold on "Silvio," but, my God, "Watchtower," "Thyme," and "Barbara Allen" are riveting. It is this kind of show that draws out the Shakespearean comparisons--gifted for nights on end with these performances (not rock concerts, but moments where the currency of common song and Dylan's incalculable restless creativity bring poetry to the crowd) is staggering to conceive.