Dylan in Cincinnati: November 1981

Dylan Context

In his 1963 poem “Last Thoughts on Woody Guthrie,” a young Bob Dylan vents his disillusionment and disgust with the corrupt modern world. He resents the relentless social pressure to conform to warped, shallow, materialistic values. He is searching for some defense from the siege against his soul. Part holy invocation and part profane howl, he cries out,

Sayin’, “Christ do I gotta be like that

Ain’t there no one here that knows where I’m at

Ain’t there no one here that knows how I feel

Good God Almighty

THAT STUFF AIN’T REAL.”

How does it feel? Hopeless. So the poet/pilgrim goes looking for hope. He sees two potential paths leading toward what he needs:

You can either go to the church of your choice

Or you can go to Brooklyn State Hospital

You’ll find God in the church of your choice

You’ll find Woody Guthrie in Brooklyn State Hospital.

Obviously, Young Goodman Dylan chose the path to Woody. But it is also worth noting that the poem is titled “Last Thoughts on Woody Guthrie.” This isn’t an elegy: Guthrie’s gradual deterioration from Huntington’s disease would ravage him for four more years until his death in 1967. These are “last thoughts” because, having learned all he could from the elder mentor, and having absorbed all the inspiration he needed to sustain him, the young protégé recognized it was time to strike out on his own self-guided journey.

Dylan had been hittin’ some hard travelin’ by late ’78. Feeling lost again, beset by confusion without and within, he needed a shot of love and hope. This time he followed the path leading toward the church of his choice, namely the Vineyard Fellowship in Tarzana, California. He converted to Christianity and began an intensive Bible study course. These biographical developments would be irrelevant to a study of Dylan in performance had he chosen to keep these matters private. He did not. Quite the opposite. The author of “Song to Woody” turned his attention in the late seventies to writing, recording, and publicly performing songs to Jesus.

Dylan made his religious beliefs the centerpiece of Slow Train Coming (1979), the first of a Christian trilogy of albums followed in rapid succession by Saved (1980) and Shot of Love (1981). Beginning with an extended residency at San Francisco’s Fox Warfield Theatre in November 1979, Dylan and his fellow crusaders crisscrossed the United States and Canada on three gospel tours (Fall 1979, Winter 1980, Spring 1980) in which they only played Christian songs. Once again, he showed off a singular talent for baffling audiences, not only with the fundamentalist views expressed in his lyrics, but also with the stage raps he regularly delivered between songs. Like a hellfire-and-brimstone preacher, Dylan denounced Satan’s stranglehold over this wicked world, chastised unrepentant sinners, and warned of an apocalyptic judgment day coming up around the bend when God would reward the faithful and punish the infidels.

Many dismayed fans were asking, as Paul Williams put it in a 1979 book titled Dylan—What Happened?, “Is he on a crusade? Is he lending his fame and his music to a religious movement that is politically reactionary, socially repressive, and fanatically religious? Has this poet/hero of stalwart individualism joined forces with the enemies of personal and religious freedom?” (82). It was all well and good when Dylan’s finger-pointing songs were directed at greedy bankers and tycoons, crooked politicians and judges, and racist reactionaries on the wrong side of history. But it was another matter entirely when he started pointing the finger of blame at his own audiences, condemning their behavior and beliefs (or lack thereof). Paradoxically, at the very moment when Dylan was pushing so many listeners away with his didactic evangelical lyrics and proselytizing diatribes, he was also magnetically drawing them in with some of the most impassioned live performances of his career.

Dylan’s born-again flame burned hot, but it didn’t burn long. A year after his first residency at The Warfield, Dylan returned to San Francisco in November 1980 for a series of concerts billed as “A Musical Retrospective Tour.” In these transitional performances, Dylan began reintroducing older pre-conversion material alongside his newer post-conversion songs. His motivations were doubtlessly complex, but anyone who paid close attention could tell that he wasn’t merely acquiescing to commercial pressure to play the hits. He deliberately selected older songs that made interesting juxtapositions with his newer songs, emphasizing consistent themes that endure across various periods of his art. At the beginning of this creative reintegration process, the concerts still consisted chiefly of Christian music. However, the center of gravity soon shifted. By the time Dylan arrived back in Cincinnati to play Music Hall in November 1981, the setlist was dominated by secular songs, though the religious framework was still evident, particularly at the beginning and end of the show.

Among Dylan critics, Paul Williams is the head cheerleader for the 1981 fall tour. His praise for the concerts doubles as a hosanna for bootlegs in general and their indispensable function in preserving live performances. In the second volume of his Performing Artist series, Williams marvels at those moments from 1981 where “the muse descends and suddenly singer and band are wide awake.”

It still amazes me that such moments can be captured on tape, and no doubt there are limits on the extent to which such an experience can be communicated through a recording. There is no doubt in my mind, however, that what is on these tapes is capable of enduring the way a great painting endures: as a work of art, portrait and product of a moment, an encoding of personal experience that puts us inside the bodies and hearts of other humans across space and culture and time. (211)

Williams goes so far as to hail these late ’81 shows as the pinnacle of Dylan’s performance art: “Dylan’s relationship with his band—on stage, at the moment of performance—was particularly good in the fall of 1981, and the music that resulted was exceptional. After years of striving to blend the old and the new, the spiritual and the worldly, Dylan and companions seemed to have found the right recipe” (226-27). As proof, he points to transcendent concerts in New Orleans on November 10 and 11, and Houston on November 12. My assessment of the Music Hall shows a week prior (November 4 and 5) is not as uniformly euphoric. The bootleg (LB-3089) captures some sublime performances, among the very best in all of Dylan in Cincinnati. However, there are also songs that fall flat or come up short. What is most impressive about the concert I’ll be examining in depth (November 4) is the tenacity of Dylan and his bandmates. Each time they get knocked down, they pick themselves up off the mat and come back swinging harder than ever.

Cincinnati Context

1981 was a banner year for the hometown teams. The Reds finished the season with the best overall record in all of Major League Baseball. Because of the unprecedented split-season format devised to accommodate a prolonged player’s union strike, however, the Reds finished second in both halves and were shut out of the playoffs. In a remarkable reversal of fortune, the football team at Riverfront outperformed the baseball team.

The once lowly Bengals had their best season in franchise history, finishing 12-4, winning their division and the American Football Conference championship, before narrowly losing the Super Bowl to the San Francisco 49ers. On their way to the Super Bowl, the Bengals defeated the San Diego Chargers at Riverfront Stadium on January 10, 1982, in a legendary game nicknamed “The Freezer Bowl.” It remains the coldest National Football League game on record. The air temperature was –9 °F (–23 °C), but arctic blasts throughout the day brought the wind-chill factor down to –59 °F (–51 °C).

The winds of political change were blowing as well. The “Reagan Revolution” of 1980 saw former film actor and Governor of California Ronald Reagan soundly defeat the incumbent Democrat Jimmy Carter to become President of the United States. In 1980, Reagan scored a resounding victory in Ohio, receiving 52% of the vote to Carter’s 41%, essentially mirroring the national results. Reagan owed his electoral landslide in large part to support from evangelical Christians, a growing force in American politics.

In Time Out of Mind, the second volume of his Dylan biography, Ian Bell reminds us that Dylan’s conversion coincided precisely with the political mobilization of the Moral Majority, founded by Reverend Jerry Falwell in 1979. As Bell sees it,

Evangelicals had once made it a point of principle to steer clear of organised politics. When they took up the challenge—more in anger than in sorrow, it seemed—the effect on the lordly Republican Party was revolutionary. Utterly uncompromising in any matter capable of being defined as an issue of religious belief, the new conservative Christians began to talk as if they alone were authentically American, the sole heirs to the nation’s first principles and founding ideals. Faith and ideology began to seem indistinguishable. (189-90)

This broader context is important to understanding the backlash against Dylan’s gospel period. For fans who didn’t live through those years, you might listen to Trouble No More: The Bootleg Series, Vol. 13, 1979-1981 and wonder how anyone could deny, dismiss, or revile such unassailably awesome performances. Fair enough, but that music was neither produced nor received in a vacuum.

“It is a mistake, then, to view Dylan’s experiences only through the prism of Bob Dylan,” asserts Bell. “His conversion is significant for what it meant to his art, for the nature of the faith he chose, and for what it said about his identity as a Jew. But his response to born-again religion was entirely of its American place and time” (190). Regarded within the American context of its place and time, Dylan’s new songs seemed more compatible with the religious right than with the leftist leanings of most of his fans. Of course, we should be careful to avoid oversimplifications like Christian = Conservative. After all, Jimmy Carter, who counted Dylan as a friend, was a Democrat as well as a self-identified born-again Christian. And of course gospel music had long been an integral part of the civil rights movement and was frequently allied with progressive activism. Therefore, we shouldn’t presume that Dylan went into the baptismal water as a decadent Democrat and reemerged a righteous Republican. That caveat notwithstanding, it is true that several positions Dylan took on hot-button cultural issues in the first flush of his post-conversion zealotry were close enough to the theocratic bombast of the Moral Majority to disturb and alienate a large segment of his audience.

Dylan had other worries on his troubled mind when he returned to Cincinnati. One of the strangest stories I’ve uncovered in my research comes from Mary Judge. She is Principal Librarian for the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra and has worked at Music Hall since 1975. She shares this bizarre anecdote:

In 1981, Bob Dylan was performing at Music Hall. It was very shortly after John Lennon was killed, and Bob was convinced that someone was out to kill him, too. Even though he has eight bodyguards and his dressing room was 100 feet from the stage, he refused to walk. At curtain time, I heard a loud backfiring sound and then Bob Dylan came roaring down the hallway on a huge motorcycle! He jumped off the bike just feet from the stage and rushed onstage! The stagehand who caught the bike turned it around and, when the first half was almost over, revved it up . . . and sure enough, Bob jumped back on and roared back to his dressing room, filling the backstage with exhaust and gas fumes. (23)

This sounds like a tall tale, the sort of mythology that has accumulated around Dylan for decades and burnished his mystique. How could a motorcycle have made him any safer at Music Hall? And what’s he doing with a bike on tour in Cincinnati anyway, let alone in the hallways backstage? It sounds ludicrous . . . but that doesn’t mean it didn’t happen.

Dylan was badly shaken when John Lennon was murdered by an obsessive fan on December 8, 1980. As a fellow rock icon who had attracted similar levels of fanatical devotion, Dylan had legitimate cause to fear for his safety. Remember that he had been the target of death threats as far back as the mid-sixties. The film No Direction Home memorably includes footage of Dylan being informed before a 1966 concert in England that someone had phoned the theater threatening to shoot him. He tries to deflect the anxiety with humor—“I don’t mind being shot, man, but I don’t dig being told about”—but he is clearly unnerved. Al Kooper, who played organ behind Dylan in his first electric performances at Newport, Forest Hills, and the Hollywood Bowl, explains why he quit the band before the fall 1965 tour: “I actually was frightened when I got the tour itinerary to see we were going to play Dallas, where they had just killed the president. And I thought, ‘If they didn’t like that guy, what’re they gonna think of this guy!”

Kooper was back in Dylan’s band in 1981, and the atmosphere of menace was back, too, less than a year after Lennon’s murder and seven months after John Hinckley, Jr., had shot President Reagan in March. Tim Drummond, a Cincinnati native who played bass on the tour, told Howard Sounes about receiving a wrapped gift from the bandleader: “‘I thought, Bob Dylan’s given me a present!’ says Drummond. ‘Maybe a box full of diamonds?’ It was a bulletproof vest” (337-38). Fred Tackett corroborates Drummond’s story about bulletproof vests, elaborating to Tim Cumming:

John Lennon was shot in the winter of 1980 and that concerned everyone, because you thought, my God if someone went after John, why wouldn’t they go after Bob? So we were much more concerned. When we started the European tour everyone had bulletproof vests, and all this kind of stuff, special security guys checking out all the apartment buildings around the venues. That lasted for a little bit. Maybe one concert we wore those bulletproof vests, and then someone said, this sucks, enough of that. But there was a feeling of danger, something that was different from just going out and playing a bunch of good songs.

Dylan’s safety concerns were not just general but also very specific. He was tormented at the time by a stalker, Carmel Hubbell. Sounes pored over the police records for his biography Down the Highway, where he reports extensively on the danger posed by Hubbell. She claimed to have had an affair with Dylan in Michigan and then relocated to California to allegedly rekindle their relationship. She tried contacting him numerous times, hung out around his house, studios, hotels, and concert venues, and made increasingly violent threats toward Dylan and those around him (Sounes 338, 344-46). Odd as the Music Hall motorcycle story may sound, the hostile climate surrounding Dylan might have prompted such erratic behavior.

Dylan played his first electric show in Cincinnati at the luxurious Music Hall in November 1965. Tickets went fast when he announced his return to the venue for November 4, so a second concert was scheduled for November 5. I will be focusing exclusively on the first show for multiple reasons. At over 2 ½ hours and 30 songs, it was the longest concert Dylan ever played in Cincinnati. The final 1981 show in Lakeland, Florida, featured the only other 30-song setlist of the tour, and it has been quite rare over the course of Dylan’s long career for him to reach that threshold. Dylan shortened the setlist to 26 songs on November 5. The sheer length of the first show makes it special and recommends it for careful consideration. Dylan was also more talkative with the audience that first night, and I’ll be considering some of his stage banter in relation to the city and to his performance. The Cincinnati papers all spotlighted opening night for reviews, so there’s a better record of local reactions to that concert, too. Finally, and most importantly, the bootleg recording I have for the first night, while far from pristine, is vastly superior in audio quality to the wretched tape I have from the second night. I cannot comment accurately on performances I cannot hear clearly. The votes are in and we have a winner.

Now let’s kick off our shoes (in honor of Ruth Voss), have a grassy stroll through Washington Park, cross the street (mind those pesky cobblestones), climb the stairs leading into the gothic palace, patter across the polished marble chessboard floor of the foyer, wriggle our toes on the red carpet of Springer Auditorium, and take our virtual seats for the first 1981 concert at Music Hall.

The Concert

When: November 4, 1981

Where: Music Hall

Band: Bob Dylan (vocals, guitar, and harmonica); Tim Drummond (bass); Jim Keltner (drums); Clydie King (vocals); Al Kooper (keyboards); Regina McCrary (vocals); Madelyn Quebec (vocals); Steve Ripley (guitar); Arthur Rosato (drums); Fred Tackett (guitar)

Setlist:

1. “Gotta Serve Somebody”

2. “I Believe in You”

3. “Like a Rolling Stone”

4. “I Want You”

5. “Man Gave Names to All the Animals”

6. “Maggie’s Farm”

7. “Girl from the North Country”

8. “Ballad of a Thin Man”

9. “Simple Twist of Fate”

10. “Heart of Mine”

11. “All Along the Watchtower”

12. “I’ll Be Your Baby Tonight”

13. “Forever Young”

*

14. “Gamblin’ Man”

15. “The Times They Are A-Changin’”

16. “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall”

17. “Watered-Down Love”

18. “Dead Man, Dead Man”

19. “It’s All in the Game”

20. “Masters of War”

21. “Solid Rock”

22. “Just Like a Woman”

23. “When He Returns”

24. “Señor (Tales of Yankee Power)”

25. “When You Gonna Wake Up?”

26. “In the Garden”

*

27. “Blowin’ in the Wind”

28. “It’s Alright, Ma (I’m only Bleeding)”

29. “It Ain’t Me, Babe”

30. “Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door”

First Set

“Gotta Serve Somebody” holds a place of distinction in Dylan’s canon. It was the opening track on his first Christian album Slow Train Coming, and his vocal performance earned him a Grammy. It was the first song he played each night during the all-gospel tours, and it continued to appear at the top of most 1981 setlists, including both nights in Cincinnati. Over the years, Dylan has played “Gotta Serve Somebody” more than any other song from his Christian trilogy by far, with well over 600 live performances spread across six different decades [“In the Garden” comes in a distant second at 329]. The long stage-life of this song is testament to its enduring power well beyond its initial born-again context. But in 1981, the song was still serving the Lord. Dylan and the band burst onto the Music Hall stage, making a forceful opening statement and putting the audience on notice: “It may be the Devil / Or it may be the Lord / But you’re gonna serve somebody.”

Lyrically, the song doesn’t actually choose a path. Rather, it positions the listener (you) at the crossroads where such a decision cannot be avoided. Not serving is not an option: if you don’t follow the righteous path, then by default you choose the path of wickedness, doing the Devil’s work and pointing your soul toward damnation.

“Gotta Serve Somebody” works in tandem with the next two songs in the setlist, “I Believe in You” and “Like a Rolling Stone,” to establish moral parameters for the concert. “I Believe in You” is a declaration of faith, dramatizing the results of following Jesus: “I walk out on my own / A thousand miles from home / But I don’t feel alone / Because I believe in you.

The Everyman and Everywoman who choose the Christian path may be spurned and mocked, as Jesus himself was on the road to Calvary, but the way of the cross leads to Heaven. Where does the other road lead?

The next song tells us. “Like a Rolling Stone” describes a figure, Miss Lonely, who once lived high and mighty but has since come crashing down. Although the song was written many years before his Christian conversion, in performance Dylan reverses the chronology so that “Like a Rolling Stone” functions as sequel to “I Believe in You.” Following from the first song (you must choose a path) and the second song (the path of righteousness), the third song audits the wages of sin, enumerating the consequences when one sinks into depravity, indulgence, selfishness—when you choose to serve the Devil instead of the Lord:

[Background Singers:] How does it feel? / [Lead Singer:] How does it feel?

How does it feel? / To be without a home

How does it feel? / Like a complete unknown

Like a rolling stone

This new vocal arrangement, where The Queens of Rhythm are a beat or two ahead of Dylan in delivering each line, creates a call-and-response effect. They ask how it feels, and he answers. The three backup singers harmonize in unison, but the lead singer is out of step with them, he’s drifting off the path. He implies as much with his words, but he communicates it most viscerally through his dissonant vocal delivery. This way of approaching the chorus reenacts the opening of “I Believe in You”: “They ask me how I feel / And if my love is real / And how I know I’ll make it through.” How does it feel to be without the communion, protection, and direction provided by Jesus? Homeless. Lost. Alone.

Here’s the rub, though. Tonight I don’t believe “I Believe in You.” I’m not making a theological claim here but a musical one. My quarrel isn’t with Jesus but with Dylan’s half-hearted performance at Music Hall in November 1981. Does the singer believe “I Believe in You”? He acts like they never have met. Maybe my reaction would be different if I had never heard the song performed well before, but I have.

For my chapter in Erin Callahan and Court Carney’s The Politics and Power of Bob Dylan’s Live Performances: Play a Song for Me, I studied Dylan’s twelve-concert residency at San Francisco’s Fox Warfield Theatre (November 9-22, 1980) to launch “A Musical Retrospective Tour.” Every night except one, the show began with the same three-song road map for the soul: “Gotta Serve Somebody,” “I Believe in You,” and “Like a Rolling Stone.” Dylan and the band got the audiences’ hearts throbbing with the opening number, and then he ripped their hearts out with “I Believe in You.” In the context of what I call “The Warfield Cycle,” where Dylan was purposefully beginning to mend strained relations and play some songs that first united him in shared purpose and community with his fans, the song felt simultaneously directed toward Jesus and toward the audience: “Don’t let me drift too far / Keep me where you are / Where I will always be renewed.” So you can hear what I’m talking about, here is the Warfield performance of “I Believe in You” from November 10, 1980:

Dylan still served the Lord, yes, but he also wanted to renew his vows to those who stuck with him through the wilderness: “I Believe in You,” the people in this building tonight, going through this collective experience with me. [Play the track above to the end and you’ll hear Dylan single out one audience member from the collective, a renowned rock journalist: “Thank you! I wanna say hello to Greil Marcus, who’s out there some place tonight, watching with his eyes.”]

I hear a deeper sense of connection, to the song and to the audience, in November 1980 than in November 1981. Interestingly, Paul Williams fixated instead on the palpable erosion of conviction from November 1979, when Dylan debuted his all-Christian setlist at the same venue. Different residency, different Rorschach test. By 1981 in Cincinnati, Dylan’s performances were more uneven and disengaged. I wouldn’t want to speculate about the status of Dylan’s relationship with his faith, but his relationship with this song about faith has grown lukewarm.

The problem isn’t isolated to “I Believe in You.” Dylan’s flagging energy and wayward inattention are also palpable in other performances of Christian songs in the first set. Williams could hear the creep toward disinterest infecting the 1980 Warfield shows. He is unusually harsh, describing Dylan as “‘sleepwalking through most of his Christian material,’” and complaining, “‘He can’t be happy doing lackluster performances of his ‘Jesus’ songs just to keep them in the show. And the side of him that is committed to surrendering to the will of God must be a little uneasy at how readily Dylan the performer and star falls back into the routine of having his ego stroked” (quoted Heylin Trouble 199). Dylan is in the process of exchanging his religion for his profession, and his sin is his lifelessness.

The next overtly religious song in the Music Hall setlist is “Man Gave Names to All the Animals,” and it plods lethargically like a tired horse in the sun. Dylan seems to play the song out of habit, not out of passion, conviction, or need. As Vladimir observes in Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot, “habit is a great deadener” (84). Or as Beckett put it even more vividly in his study of Proust, “Habit is the ballast that chains the dog to his vomit” (515). Dylan’s chained dog doesn’t run free in “Man Gave Names to All the Animals.” Another key indicator of waning commitment is the relative scarcity of religious songs in the setlist. As recently as the spring of 1980, Dylan had been exclusively performing post-conversion compositions; but by November 4, 1981, only ten of the concert’s thirty songs come from the Christian trilogy.

Dylan’s enthusiasm for performing his secular songs rises in direct proportion to his falling interest in the religious songs, as if vitality is being transferred directly from the latter to jump-start the former. And it’s not only the frontman: the entire ensemble works wonders on the secular material, collaboratively breathing life into Dylan’s back catalogue. There is nothing habitual in their labors: they make the old new again. Having mothballed the classics for all of 1979 and most of 1980, Dylan and his band take them off the shelf in 1981 like they’re unwrapping brand new gifts.

2023 Rock & Roll Hall of Fame inductee Al Kooper deserves a share of the credit for helping Dylan reconnect with mid-sixties songs and rediscover his joy for playing them live. Kooper’s organ is incandescent on Highway 61 Revisited and Blonde on Blonde, and he reignites the spark at Music Hall. What a thrill to hear the duo reunited on “Maggie’s Farm” and “Like a Rolling Stone”—the first two songs Dylan went electric with at Newport ’65—and on Kooper’s favorite tune from Blonde on Blonde, “I Want You.”

The 1981 Music Hall version of “I Want You” sparkles and dances. Kooper’s spritely organ brings out the best in Dylan’s vocals. The singer sounds a bit subdued at first, but I come to realize that he’s intentionally holding back, laying low, waiting to hear the call from Kooper before he springs out and pounces.

Dylan loves playing “Maggie’s Farm” live (over a thousand times in concert), and his performance tonight is especially memorable. The pounding drumbeat propels the song forward like tidal waves crashing into the shore.

There were two drummers on the fall tour, with Arthur Rosato behind the kit alongside the legendary Jim Keltner. Cincinnatian Tim Drummond fortifies the rhythm on bass. Drummond earned his chops playing with James Brown and The Famous Flames, and he went on to team up with Keltner (aka Tim & Jim) to form one of the most sought-after rhythm sections in the music business.

Dylan feeds off some Famous Flames of his own tonight—the scorching Queens of Rhythm—adding vocal fuel to keep each other’s fires burning hot. “Maggie’s Farm” is doubly interesting viewed in light of Dylan’s latest artistic transition in 1981. Ever since he blasted out this ear-piercing anthem as the shot heard round the musical world, “Maggie’s Farm” has been interpreted as a declaration of independence. “I ain’t gonna work on Maggie’s farm no more.” In other words, “I ain’t gonna keep up this stale routine—I quit!” Dylan effectively issued the song at Newport as his defiant letter of resignation: I will no longer be your spokesperson. The line of demarcation isn’t as precise in 1981 as it was at the aptly named Freebody Park on July 25, 1965. Nevertheless, when Dylan sings “Maggie’s Farm” at Music Hall sixteen years later, it seems to augur big changes on the horizon. In hindsight we can see what was already audible in the concerts: Dylan was coming to the end of his road as a Christian messenger. He wouldn’t be working on Jesus’ farm much longer.

Meanwhile, Dylan and company have their mojo working on refurbished secular favorites. The best example from the first set is “Simple Twist of Fate.” Keltner, Rosato, and Drummond assemble the sonic skeleton, and Kooper puts flesh on the bones with deft organ flourishes. But the animating spirit that jolts the performance into life is Dylan’s vocal delivery. He feeds off the musical groove and guides it with his strongest instrument—his voice—building toward an exquisite apotheosis of longing.

Although Paul Williams was describing a different performance, his words ring true and reflect what I hear in the 1981 Music Hall rendition of “Simple Twist of Fate”: “sometimes all the musicians, including Dylan, get into a groove or fall under a collective spell, inspired by, expressed through, and held together by a kind of musical grace. They hear it together, they reach for it together, and they don’t fail. Dylan as singer and focal point becomes the vehicle for the expression of the group heart” (Middle 71).

The Queens of Rhythm are vital to “the group heart” of Dylan’s 1981 band. Each of these singers deserves major credit, but make no mistake about it: The Queens had a King, and her name was Clydie.

I want to thank Laura Tenschert for first making me realize just how crucial Clydie King was as Dylan’s featured duet partner. King sings with Dylan on multiple tracks for Shot of Love, and allegedly the two recorded enough covers for an album that was never released (some are now available on The Bootleg Series, Vol. 16: Springtime in New York, 1980-1985). After her death in 2019, Dylan told David Browne of Rolling Stone: “She was my ultimate singing partner. No one ever came close. We were two soulmates.” Dylan and King’s special rapport should be obvious to anyone who attended the 1981 Music Hall concerts or listens subsequently to the bootleg. Their sweet duet on “Heart of Mine” is endearing, but the one that lifts me off my seat is “I’ll Be Your Baby, Tonight.”

What a treat! The crowd spontaneously starts clapping along to this jaunty, swinging performance. Much as I love the album version, the song works best as a duet. We eavesdrop on an amorous couple as they pass around the booze and slowly get buzzed, sauntering toward sex but in no hurry—they’ve got all night. Dylan and King are pros, and they play their parts convincingly. I buy everything they’re selling. This number also works well as a direct address to the audience: “I’ll be your baby tonight.” The Music Hall crowd sounds game for the seduction. Of course we’ll be your baby tonight! Pass that bottle over here.

Not everyone finds King and her fellow Queens of Rhythm as intoxicating as I do. Tenschert calls out Clinton Heylin for repeatedly belittling the “girlsingers” in Dylan’s bands from the late-seventies through the mid-eighties, and he is far from alone. As I discussed in the 1978 installment, there is a faction of Dylan fans (I’ll let you guess the typical demographic profile) who wince at The Queens of Rhythm, individually and collectively, and couldn’t wait for Dylan to dethrone them. Recall that, in 1978, the local Cincinnati chapter of this faction was headed by Enquirer critic Cliff Radel, who dismissed Carolyn Dennis, Jo Ann Harris and Helena Springs as “three useless backup singers.” The lineup of singers had changed by 1981 to Clydie King, Regina McCrary, and Madelyn Quebec, but Radel’s tastes had not evolved. If anything, his biases were even more firmly entrenched. In his review of opening night at Music Hall, Radel alludes to Dylan’s “nine-piece band, which featured three useless female singers wearing diaphanous garments that would have been the hit of any slumber party in 1965.” Radel clings to his sexism but seems to have lost his thesaurus, recycling the same diss from 1978 about three useless singers, then topping it off with a condescending fashion critique. Such blatant disrespect should come as no surprise by this point, but that doesn’t make it any easier to stomach.

Some members of the Music Hall crowd are no better. After Dylan finishes the first set with “Forever Young,” the vocal trio takes the spotlight for “Gamblin’ Man.” This traditional song provides an effective pivot between the first and second sets. The story told in “Gamblin’ Man” is reminiscent of “Dyin’ Crapshooter’s Blues,” one of the inspirations behind Dylan’s song “Blind Willie McTell.” A man who has devoted his life to sin now faces death and his day of reckoning. But unlike McTell’s song, which is told largely from the gambler’s perspective, “Gamblin’ Man” is told from the perspective of the gambler’s worried mother: “I wonder where / He’s a gamblin’ man / I wonder where the poor man’s gone.” It could be a question about a fugitive on the run from debtors or the police, but it sounds more like concern for the fate of his soul. Is he with the Devil or the Lord? Is he knockin’ on the door of Heaven or Hell?

On a self-referential level, the song also alludes to Dylan’s temporary absence from stage: “I wonder where the poor man’s gone?” [According to Mary Judge, he had gone to take a quick spin on his motorcycle backstage.] It’s a clever theatrical ploy, pulled off beautifully by The Queens of Rhythm. Unfortunately, their talents are squandered on some in the audience who have no patience for singers they regard as superfluous. These yahoos close their minds, plug their ears, and stand on their hind legs to bark displeasure: “We want DYLAN!”

The haters make me want to raise the ghost of Sam Wyche and hand him a microphone. At a notorious December 1989 Bengals game in Cincinnati, the referees halted the game because disgruntled fans were throwing snowballs onto the field. The officials gave hometown head coach Sam Wyche a live mike on the sideline in hopes that he could quell the rowdy crowd. “Will the next person who sees anybody throw anything on that field point him out, and get him out of here?” boomed Wyche over the stadium speakers. To punctuate his point, he used a heated cross-state rivalry to prick the conscience of local fans: “You don’t live in Cleveland—you live in CINCINNATI!” We could’ve used Sam Wyche at Music Hall on November 4, 1981.

Interlude

The interlude between sets seems a good place to insert some special notes of local interest. Between 1979 and 1981, Dylan spoke to the audience between songs more often than at any other point in his career. Initially his stage raps took the form of mini-sermons, but he had abandoned preaching by the fall of 1981. Nevertheless, he was in a talkative mood on opening night at Music Hall. The most tantalizing Bob Talk (as Dylanologists call it) appears between “Like a Rolling Stone” and “I Want You.” Dylan tells the audience: “I want to thank you, Cincinnati. Was there a place in Cincinnati called . . . what was it called? Ollie’s Trolley? Something like that? Do they still have that here? I wrote a song there one time, sitting in Ollie’s Trolley. Can’t remember exactly when. But I do remember where. It was in Ollie’s Trolley.”

Intriguing! Which song? I’ve actually written about this subject before. Rather than repeating myself, check out my piece “Slow Trolley Coming,” which Ray Padgett graciously posted on his wonderful Substack site Flagging Down the Double E’s.

I’ll let Dale Stevens set up the other noteworthy local story. Sixteen years after covering Dylan’s first appearance in Cincinnati, Stevens returned to Music Hall to review the November 4 concert for the Post. He filled in visual details that didn’t come through on audiotape, like this opening description: “‘Happy 20th, 1961-1981.’ That was the banner a fan had hung from the balcony at Music Hall, where Bob Dylan opened his two-day stand last night” (1B). Stevens’s obsession with Dylan’s hair hadn’t waned with the passage of time: “He made his entrance in the dark last night. The first light was a single yellow spot behind him. It made his perm into a halo” (1B). I’m especially interested in Steven’s description of Dylan’s fellow musicians: “His band, which was frequently out of tune last night—possibly because it contains four guitars—moves and mugs enough that, with several hats and black suits, they sometimes are a gentle blend of the Blues Brothers and Sha Na Na” (1B). It seems that Cincinnati music critics all moonlight as fashion critics. But keep your eye on those hats.

With back-to-back Music Hall shows, Dylan had some extra time in the city. He spent part of it at the best hat shop in Cincinnati. Batsakes has been a flagship downtown business since its opening in 1907, the same year that Dylan’s paternal grandfather, Zigman Zimmerman, immigrated to America. Frank Weikel broke the story about Dylan’s splurge in his December 14 column for the Enquirer titled “Dylan Finds City Is Tops in Hat Dept.”:

When Bob Dylan, the folk-singing star whose recent offerings have turned to sacred music, visited the Queen City last month for a performance at Music Hall, he left town with a much larger hat collection than he arrived with. Dylan and a companion showed up at a Seventh Street hat store, and before leaving, he bought 40 hats. . . . The cost topped $1,000. The hats were paid for in cash . . . with $100 bills. (C-1)

In 2007, the Enquirer profiled Batsakes in honor of its centenary. John Eckberg interviewed Gus Miller, who immigrated to Cincinnati from Greece as a 17-year-old in 1951 and was given a job by his uncle Pete Batsakes. As of this writing, Miller still puts in a full work week at the shop where he has been employed for over 70 years.

The hatter was behind the counter when Dylan walked in, and here is what he remembers: “‘A little skinny guy. He wore a hood. He’d try on a hat, take off the hat and put his hood back up. Try on a hat. Take it off. Hood back up. He bought $4,000 worth of hats. I didn’t know who he was. When he got back into his limousine, his manager told me’” (Eckberg J-5). Notice how the total price has quadrupled since first reported in 1981, further embellishing the Dylan mythology. The fall tour itinerary lists a day off in Cincinnati on November 3 (Heylin Trouble 265), which must have been shopping day. Surely the fancy headgear the musicians were showing off on November 4 was part of the Batsakes spree.

Now let’s get Dylan and his hatless halo off that bike and back on stage.

Second Set

Any unruly fans are pacified when the frontman returns with his acoustic guitar and harmonica to play “The Times They Are A-Changin’.” It is a beautifully sensitive rendition.

Dylan’s vocal delivery is softer, slower, and in a higher register than the familiar album version. The Music Hall audience listens in rapt silence, hanging on his every word and note. I can never hear the original recording without thinking of Dylan’s scowling face on the album cover. As written, it’s an angry young man’s battle cry with embedded threats for anyone obstructing the tidal wave of sociopolitical change. As performed on this night in Cincinnati, however, the 40-year-old singer casts a different spell. Here the mood is solemn and the tone is pleading, as if his chief concern is to avoid a violent clash rather than instigate one. But storm clouds are gathering.

The skies open during the next song, another sixties anthem, “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall.”

With each successive verse, more instruments and voices join the fray, increasing the volume and intensity, as if the musical rainmakers are summoning the prophesized storm on stage.

Dylan constructs the opening section of the second set as a bridge between his old and new material. He captivates the audience with two guaranteed crowd-pleasers from the sixties, then he guides them across the water to the eighties shore with two songs from Shot of Love, released just three months earlier. “Times” and “Hard Rain” are thematically linked to “Watered-Down Love” and “Dead Man, Dead Man” through shared water imagery of drowning and resurrection. The flood begins to rise in the opening verse of the four-song sequence:

Come gather ’round people wherever you roam

And admit that the waters around you have grown

And accept it that soon you’ll be drenched to the bone

If your time to you is worth savin’

Then you better start swimmin’ or you’ll sink like a stone

For the times they are a-changin’

Here the potential drowning victims are on the wrong side of history, standing in the way of civil rights progress. In the next song, the just and unjust are in the same boat, equally vulnerable to the gathering storm. Even the prophet who anticipates the coming tempest is in danger of being consumed by the cataclysm, a new age Noah on an arkless Mount Ararat:

And I’ll tell it and think it and speak it and breathe it

And reflect it from the mountain so all souls can see it

Then I’ll stand on the ocean until I start sinkin’

But I’ll know my song well before I start singin’

And it’s a hard, it’s a hard, it’s a hard, it’s a hard

It’s a hard rain’s a-gonna fall

Drowned if you do, drowned if you don’t. The effect of juxtaposing these two songs is to suggest that, no matter which side you’re on, whether you swim with the tide or against it, whether you’re down in the flood or up on the mountaintop, no one is guaranteed safety when the winds of change reach hurricane force.

Dylan narrows the scope and lowers the stakes with the third song of the set, “Watered-Down Love.” “You don’t want a love that’s pure / You wanna drown love / You want a watered-down love.” This first step off the bridge and onto the eighties shore is rather squishy. The impulse of following up “Hard Rain” with “Watered-Down Love” may have been to stress symbolic consistencies between the songs, but the actual effect is to expose the latter song as overmatched, a lightweight struggling to hold its own against the heavyweight champ.

“Watered-down” means diluted and inferior, and it’s hard not to feel that way about Dylan’s trivial track from Shot of Love in comparison to the song’s profound predecessor in the setlist. Dylan soon reached the same conclusion. “Watered-Down Love” remained in the regular rotation for a couple more weeks, then it was driven deep beneath the waves, never to be heard from in concert again. Weirdly, the sound quality of my bootleg recording improves dramatically midway through this song—the taper must have made an equipment adjustment or switched positions. I didn’t realize just how muffled the audio had been until it suddenly became much clearer, like a swimmer who finally knocks the water out of his ears.

The improved sound in my earbuds coincides with improved sound coming from the stage, as the band shifts into a more substantial song from the new album, “Dead Man, Dead Man.” This is the most spirited performance of a religious number since the concert opener “Gotta Serve Somebody.” Keltner and Rosato’s drums work like spurs in the flanks of this song, propelling the music forward at galloping speed, trading tired horses for thoroughbreds.

Dylan’s interplay with The Queens of Rhythm on “Dead Man” turns Wednesday night at the opera house into Sunday morning at church. This is the first religious song tonight where all the singers sound imbued with the Holy Spirit. Form matches content. This performance enacts theatrically what the song calls for lyrically: resurrecting the dead. This zombie needs to be born again. The imagery of “Dead Man” is the opposite of watery; it’s bone dry. “Dead man, dead man / When will you arise? / Cobwebs in your mind / Dust upon your eyes.” The central figure is suffering from spiritual drought and wandering a wasteland. He shouldn’t fear death by water, he should positively welcome it. Drowning is exactly what he needs: i.e., baptism, the drowning of the desiccated old self and the resurrection of a sanctified new self.

The predominant theme of the second set is death and resurrection, particularly in the latter half when religious songs outnumber secular ones for the first time since the concert’s opening section. Two gospel numbers stand out in this segment, one as a disappointing flop and the other as an unexpected triumph.

“Solid Rock” has a strong claim as the hardest rocking song of Dylan’s Christian period, and it was a dependable highlight throughout the gospel tours. Regrettably, Dylan seems to have lost his grip on “Solid Rock” by November 1981. The problem is speed, namely the lack of it. On a good night, “Solid Rock” is a stampeding bronco. But tonight Dylan jerks back too hard on the reins. I keep waiting for the song to break loose, and the band sounds like they’re itching to run, but Dylan holds them back for some misguided reason.

There are listeners who actually like this slower arrangement of the song. For instance, in the liner notes to the box set of Trouble No More, Rob Bowman admires the “slide guitar swamp blues” of “Solid Rock” as performed in Philadelphia a couple weeks prior, the same arrangement played in Cincinnati (quoted by Jim Salvucci in Callahan & Carney). But after listening to the bootleg many times, I remain unconverted. I have to side with Heylin on this one, who finds the “gelatinous groove” (Still 170) of the slower version to be “particularly disastrous” (Trouble 271). The Music Hall “Solid Rock” sounds to me like a 45 played at 33 rpm. “Solid Rock” is watered-down at best, if not altogether drowned.

I have a completely different reaction to “When He Returns.” Some of Dylan’s Christian songs are jubilant shouts, some stern rebukes, and some self-righteous harangues; but his finest expression of spiritual fragility and surrender comes on the closing track of Slow Train Coming. “When He Returns” is Dylan’s “Batter my heart, three-person’d God,” his testimony about an omnipotent God who breaks down the sinner before building him back up as a faithful servant.

The iron hand it ain’t no match for the iron rod

The strongest wall will crumble and fall to a mighty God

For all those who have eyes and all those who have ears

It is only He who can reduce me to tears

Don’t you cry and don’t you die and don’t you burn

For like a thief in the night, He’ll replace wrong with right

When He returns

As powerful as the song is on the album, Dylan fully fathomed its depths in live performance. Paul Williams superbly captures the effect:

What a mood this song sets! And how much it has to say to the listener, once listener and pianist and singer are sharing the same mood. The live version manages to go beyond the gloriously dramatic, self-conscious vulnerability of the album track into a shared vulnerability, a welcoming (with no softening of the song’s fiercely honest language), a fellowship. What results is a performance worthy of a great singer and a master creator—Dylan at his most naked and his most inspired, quite a combination. (Middle 155)

“When He Returns” is bound to the born-again experience and to faith in Christ’s second coming, so there didn’t seem to be an appropriate place for the song in Dylan’s setlists once he began transitioning back to secular music. He played the song nightly during the first and second gospel tours, but only once on the third and final gospel tour, at which point “When He Returns” appeared to have served its purpose and been permanently retired.

Dylan plays “When He Returns” on November 4, 1981, for the first time in eighteen months—and for the final time in his career. The first remarkable thing about the Music Hall performance, then, is that it happens at all. The second surprise is the nearly unrecognizable arrangement. Dylan directs the band on rhythm guitar, rather than taking the lead on piano. Their playing sounds haphazard and tentative at first, maybe improvised on the spot. Dylan certainly didn’t spend time refamiliarizing himself with the words. He skips verses, repeats others, transposes lines, alters vocabulary, and occasionally fills in dummy lyrics. This sloppiness earns the derision of Heylin, who mocks the Music Hall “When He Returns”:

Dylan himself wanted in on the whole garageband aspect of this new live sound and his notoriously reedy rhythm-guitar was bumped up in the mix, with rather discordant results, especially on songs he was trying out live for the first time in a while. A last-ever “When He Returns,” a song he’d not played in a year and a half, one night in Cincinnati was played on the guitar, not the piano, and without recourse to lyrics he could no longer readily recall (a telling confirmation of how detached he had grown from some of the gospel material). The result was painful to behold. (Trouble 271)

Heylin gets some basic facts right in this description, but he gets the feeling all wrong. I absolutely love this performance of “When He Returns.” Let me try to articulate why.

Dylan’s earlier piano performances were riveting, but this reimagination of the song is captivating in a different but equally compelling way. The singer is trying to find his way through unfamiliar waters. He fumbles at his instrument like a faint distress signal. He’s alone and lost, paddling in the dark, but then he registers the thump of drums and strum of guitars and picks up the frequency of the organ. The band falters at first, trying to figure out what is required of them from one beat to the next. Then they get it, their course becomes clear. The music gets louder, more assured. Their captain is stranded on a drunken boat and has drifted too far from the shore. They are the search party trying to rescue him. He calls to them from the darkness. “Mayday.” “Can you hear us?” “I hear you.” “We’re almost there.” They get closer, tighter, working together as a synchronized unit with a common purpose. Words are incidental here; listen to the music. Heylin is right that Dylan messes up the lyrics, but he’s wrong to think it discredits the performance. Ride the waves. The music is an ocean and it ends at the shore. Just listen: they make it home. Dylan repeats the lines “When He returns” four times at the conclusion, and then never again. The song is over, tonight and forever. It is finished.

The last two songs of the second set, as with all the fall concerts but one (November 20 in Miami), are “When You Gonna Wake Up?” and “In the Garden.” This closing sequence bookends the concert by reinforcing the moral framework with which it began. Both songs contribute to the spiritual rebirth theme; the first as a wake-up call to sleepwalking sinners, and the second as a reenactment of the crucifixion and resurrection of Jesus. Although both performances seem restrained in comparison to their high-water marks during the gospel tours, Dylan does begin to loosen the reins, freeing the band to play with more fervor than on the inhibited “Solid Rock.” The relatively subdued beginnings seem deliberate and dramaturgically justified in “When You Gonna Wake Up?” and “In the Garden.” In the former, the song starts off sleepy but gradually shakes off its slumber and awakens.

In the latter, the opening scene in the Garden of Gethsemane begins in diminuendo, building over the course of the Passion, and ultimately reaching crescendo when Christ rises from the dead.

“In the Garden” remained on Dylan’s setlists longer than most Christian songs, well into the eighties and nineties, and even getting resurrected a couple times in the 21st century. This could indicate Dylan’s continuing Christian faith, but it seems just as likely that he was drawn to the song’s theatrical vitality. “In the Garden” also works effectively as self-commentary on Dylan’s combative relationship with audiences—“Did they speak out against Him, did they dare?”—and his pugnacious resilience as a performer—“When He rose from the dead, did they believe?”

Does the Music Hall audience believe? I don’t hear much audible response to these closing songs of the second set, certainly not as much as, say, the thrilling finales in Toronto or San Francisco the year before. Of course, this could just be the fluky result of the taper’s position in the auditorium or the limitations of his equipment. Dale Stevens was there in the room, and he reports a livelier response than what comes through my earbuds. According to Stevens, “One row of feverish fellows down front sang along with many of his lyrics. There were plenty of standing ovations. And, if he hadn’t done an encore, the audience probably would have stormed his dressing room” (1B).

This is reassuring news. That said, if I’m going to be critical of Dylan for uneven commitment to his religious material over the course of the concert, then I should also be critical of fans for uneven commitment to Dylan. The energy transfer between performer and audience works in both directions, an economy of interdependent withdrawals and deposits, and the transaction is voided if either party fails to pay up. If Dylan doesn’t always seem to give enough, it could be in part a consequence of not receiving enough in return.

Encore

Fortunately, all is mended in the encore, which is animated throughout by energy, grace, gratitude, and love. The first song is a gospel-inflected “Blowin’ in the Wind.” Dylan introduced this stirring arrangement to open each encore in his second Warfield residency (November 1980), and “Blowin’ in the Wind” continued to bat leadoff in every 1981 encore except one (July 5 in Birmingham, England). If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.

The Queens of Rhythm sing the first verse, then Dylan walks back on stage and joins them for the refrain. He assumes the lead from there, but he continues to depend upon the buoyant support of his vocal collaborators on each refrain. The crowd loves it, cheering and clapping along enthusiastically. Dylan has sung this song so many times, but he has a gift for reviving its spirit again and again. Al Kooper also lends a hand with a lovely organ solo, sparkling brighter than at any previous point in the concert. Although this song was written long before Dylan’s Christian conversion, its performance tonight is the spiritual highpoint of the entire concert, a ceremony of holy communion between the musicians on stage, the Music Hall audience, and us virtual bootleg communicants decades later.

Had Dylan ended the concert right there, he would have sent everyone in the building home satisfied and renewed. But he’s only getting warmed up. “All right, I’ll try and sing this one in tune,” he assures the audience as he tunes an acoustic guitar. “I don’t think I sang one song in tune all night. All right, I’m gonna try and sing this in key.” It sounds like half apology, half self-effacing humor. But really I think he’s setting us up with a little rope-a-dope routine. The Music Hall crowd is about to get walloped with a staggering “It’s Alright, Ma (I’m Only Bleeding).”

You may recall my 1978 post where I was initially resistant to the full-band rock version of this song before eventually coming around. Tonight at Music Hall Dylan delivers the kind of performance I had been hoping for three years earlier. He is really feeling the song tonight, and the audience is right there with him, responding with yelps of glee and awe between each verse, and begging for more at the end. I’m reminded of something Stevens said in his Post review. He asserted that Dylan “is much more effective as a singer in 1981 than he was in 1961, but he is much less a messiah. His great work would seem to be behind him now” (1B). Stevens announces as much with his title: “Bob Dylan: The Elder Statesman.” The critic couldn’t be more wrong about the performer’s best work being behind him—in 1981! But he is right about Dylan being treated more as a messiah in the sixties than in the eighties, and you can hear it in the congregation’s worshipful response to this sixties-style solo acoustic “It’s Alright, Ma.”

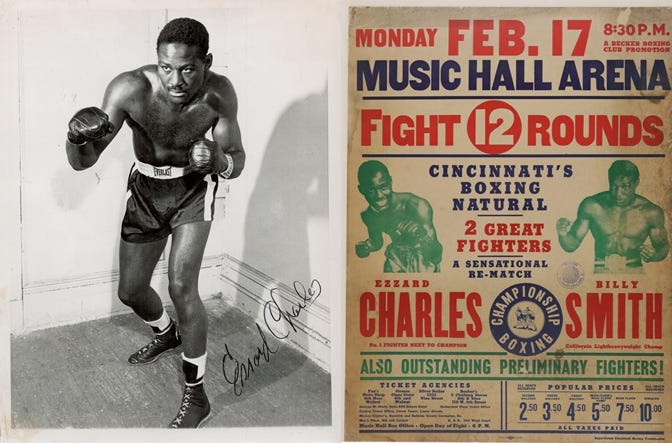

Stevens’s messiah comparison is apt, but an even better analogy may be to boxing. Music Hall is a large complex, and one wing was formerly used for sporting events, including fights featuring our greatest local boxer, Ezzard Charles (“The Cincinnati Cobra”).

Dylan is a big boxing fan, as songs like “Who Killed Davey Moore?” and “Hurricane” attest, and he once owned a boxing gym in Santa Monica. He also conducts himself like a fighter on stage, a scrappy slugger capable of punching well above his weight. Dylan made the comparison himself in his Biograph interview with Cameron Crowe: “Sometimes you feel like a club fighter who gets off the bus in the middle of nowhere, no cheers, no admiration, punches his way through ten rounds or whatever, always making someone else look good, vomits up pain in the back room, picks up his check and gets back on the bus heading out for another nowhere” (868). There may have been moments on November 4, 1981, when Dylan felt like it wasn’t his night, like the Music Hall crowd wasn’t in his corner and regarded him as past his prime. Rather than being discouraged or defeated, Bob “Boom Boom” Dylan answers the bell, charges back into the ring, and lands a late-round knockout blow—Pow!

He’s got us where he wants us now, totally in control. He follows up the stunning “It’s Alright, Ma” with the most achingly gorgeous “It Ain’t Me, Babe” I’ve ever heard.

Dylan sings in an unusually high pitch on several songs in this concert, and sometimes it sounds strained, an experiment pushed too far or a stylized affectation. But this voice is perfect for driving “It Ain’t Me, Babe” like a stake into the listener’s heart. His delivery is so raw and beseeching. He further accentuates the sense of heartbreak non-verbally with his piercing harmonica, an instrument Larry Starr calls Dylan’s “other voice” (see Starr chapter 3).

In the final verse, Dylan sings, “There’s nothing in here that’s moving / And anyway I’m not alone.” In a live context, he is right about not being alone: there is a crowded room of people transfixed by this amazing performance. But he is wrong when he sings, “It ain’t me you’re looking for.” Oh yes, it is! You’re exactly who we’re looking for. As with “Blowin’ in the Wind” at the top of the encore, Dylan delivers something closer to a religious experience with “It Ain’t Me, Babe” than with his overtly Christian material. “He stuns you by degrees,” to borrow a description from Emily Dickinson, then “Deals one imperial thunderbolt / That scalps your naked soul” (172).

After battering our hearts and lifting our spirits in the first three songs of the encore, Dylan and the band take us all the way to the pearly gates in the evening’s final song, “Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door.” The song is traditionally an expression of metaphysical angst, delivered by a dying sheriff who worries that all the blood on his hands and sins on his soul will bar him from Heaven. Those somber worries are easy to overlook while basking in the sunshine of this ultra-smooth Music Hall rendition, where reggae meets fusion jazz.

The band drifts gently on tropical waves without a worry in this world or the next. Textually, you can make a strong argument that the singer is denied entrance to Heaven. But that’s not what I hear in the song tonight, as this carefree beach band transforms the majestic Music Hall into their own super-chill tiki hut. What sad-eyed archangel would want to keep their Rasta rhythms and Caribbean drums waiting outside the gates of the celestial Highlands?

Dylan and his talented bandmates make a few stumbles over the course of the evening, and occasionally the performers and audience lose their connection with each other. However, any temporary defeats or disappointments are forgiven in the triumphant encore. Dylan may have lost some skeptics along the way, but he wins them back in the end. To paraphrase Puck’s epilogue in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, “Give me your hands, if we be friends; / And [Dylan] shall restore amends” (5.1.427-28). If I’m going to blame the audience for not giving Dylan all he needed at times, I should also give them credit for feeding his energy and inspiring him to greatness in the encore.

The forefather of method acting, Constantin Stanislavski, had a wise way of describing the crucial relationship of the audience and the stage performer:

If you want to learn to appreciate what you get from the public let me suggest that you give a performance to a completely empty hall. Would you care to do that? No! Because to act without a public is like singing in a place without resonance. To play to a large and sympathetic audience is like singing in a room with perfect acoustics. The audience constitute the spiritual acoustics for us. They give back what they receive from us as living, human emotions. (204)

Yes! I love that idea—the audience provides the spiritual acoustics for the performance. Dylan may be the main attraction we’ve all come to see and hear, and the quality of the show depends heavily upon what he succeeds or fails in delivering on any given night. But he is not alone on that stage—it is a collaborative artistic effort—and the performers don’t play to an empty room. We’re all in this thing together. Much as the singer calls out from the darkness in “When He Returns” and the band comes to bail him out, the audience and Dylan help each other find their way back to the light in the encore at Music Hall. Listeners cumulatively help create the spiritual acoustics necessary for a mutually uplifting experience.

Last Thoughts on Christian Dylan. He left Cincinnati and played several more shows that month, finishing up in Lakeland, Florida, on November 21, 1981. It was not just the end of a tour but the end of an era. A year earlier, in an interview with Robert Hilburn of the Los Angeles Times, Dylan hinted that his gospel calling was set to expire: “I’ve made my statement and I don’t think I could make it any better than in some of those songs. Once I’ve said what I need to say in a song, that’s it. I don’t want to repeat myself” (Hilburn (1980) 721). A few years later, looking back on his spiritual journey, he told the same reporter: “I don’t particularly regret telling people how to get their souls saved. I don’t particularly regret any of that. Whoever was supposed to pick it up, picked it up. But maybe the time for me to say that has just come and gone. Now it’s time for me to do something else. It’s like sometimes those things appear very quickly and disappear. Jesus himself only preached for three years” (Hilburn (1983) 757). Dylan essentially preached for three years, across a trilogy of Christian albums and three gospel tours. Shortly after his November 1981 concert in Cincinnati, he retired from public ministry and took a long sabbatical from the road, not touring again for three years. He had come to the end of another road and the end of another Dylan.

He once was found, but he became lost again. In the fourth chapter of Chronicles, Dylan describes most of the eighties as an aimless blur, a period when he lost touch with his music and his fans and seriously questioned his artistic vocation: “My performance days in heavy traffic had been grinding to a halt for a while, had almost come to a full stop, I had single-handedly shot myself in the foot too many times. It’s nice to be known as a legend, and people will pay to see one, but for most people, once is enough. You have to deliver the goods, not waste your time and everybody else’s” (147). Even at his lowest point, when he felt irrelevant and depleted, he never completely lost hope: “There was a missing person inside of myself and I needed to find him” (147). He sensed a trapped inner self looking for rescue, a dying voice calling out for resurrection.

Dylan slowly started to find his path again. As so often before, the key to his salvation was renewing his commitment to live performance. He wasn’t at the end after all, but just another crossroads. He declined the path to the retirement home and instead chose the road leading to the stage. By the late eighties, he was ready to embark on a new journey, the most ambitious of his career, a project that has come to be called “The Never Ending Tour.” He would eventually bless Cincinnati audiences with over a dozen concerts on the NET, beginning in the very first month of the tour. We will be virtually attending several of those shows in future Dylan in Cincinnati installments. Let’s hop aboard the slow trolley coming up around the bend—no rush, Dylan kept us waiting for seven years between visits, so we can take our time—eventually winding our way to his next local stop at Riverbend Music Center in June 1988.

Works Cited

Beckett, Samuel. Waiting for Godot. The Complete Dramatic Works. Faber and Faber, 1986.

---. Proust, The Selected Works of Samuel Beckett, Volume IV, ed. Paul Auster. Grove Press, 2010.

Bell, Ian. Time Out of Mind: The Lives of Bob Dylan. Pegasus, 2013.

Browne, David. “Clydie King, Unsung Backup Singer for Ray Charles and Bob Dylan, Dead at 75.” Rolling Stone (10 January 2019), https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-news/clydie-king-ray-charles-bob-dylan-singer-dead-777417/.

Callahan, Erin C. and Court Carney, eds. The Politics and Power of Dylan’s Live Performances: Play a Song for Me. Routledge, 2024.

Crowe, Cameron. Interview with Bob Dylan for Biograph (1985). Every Mind Polluting Word: Assorted Bob Dylan Utterances, ed. Artur Jarosinski, Don’t Ya Tell Henry, 2006.

Cumming, Tim. “Gospel Bob: Guitarist Fred Tackett on Playing with Dylan, 1979-1981.” Tim Cumming: Art Music Poetry, https://timcumming.wordpress.com/2017/11/01/gospel-bob-guitarist-fred-tackett-on-playing-with-dylan-1979-1981/.

Dickinson, Emily. “He fumbles at your spirit.” The Collected Poems of Emily Dickinson, ed. Martha Dickinson Bianchi. Little, Brown, 1924.

Dylan, Bob. Chronicles, Volume One. Simon & Schuster, 2004.

---. “Last Thoughts on Woody Guthrie.” The Official Bob Dylan Website, http://www.bobdylan.com/songs/last-thoughts-woody-guthrie/.

---. Official Song Lyrics. The Official Bob Dylan Website,

http://www.bobdylan.com/

.

Eckberg, John. “Capping off a century, hat shop alone on top.” Cincinnati Enquirer (21 January 2007): J-5.

Herren, Graley. “Slow Trolley Coming.” Flagging Down the Double E’s (14 August 2022),

.

Heylin, Clinton. Still on the Road: The Songs of Bob Dylan, Vol. 2: 1974-2008. Constable, 2010.

---. Trouble in Mind: Bob Dylan’s Gospel Years, What Really Happened. Lesser Gods, 2017.

Hilburn, Robert. “Bob Dylan’s Song of Salvation” (24 November 1980). Every Mind Polluting Word: Assorted Bob Dylan Utterances, ed. Artur Jarosinski, Don’t Ya Tell Henry, 2006.

---. “Bob Dylan at 42—Rolling Down Highway 61 Again” (30 October 1983). Every Mind Polluting Word: Assorted Bob Dylan Utterances, ed. Artur Jarosinski, Don’t Ya Tell Henry, 2006.

Judge, Mary. “I Remember When.” Music Hall Marks (Summer 2016): 23.

LB-3089. Bootleg Recording. Taper Unknown. Music Hall, Cincinnati (4 November 1981).

No Direction Home. Directed by Martin Scorsese. Paramount Pictures, 2005.

Radel, Cliff. “Thanks to the Mrs., Bob Dylan Turns Adversity into Triumph,” Cincinnati Enquirer (16 October 1978): A-12.

---. “Dylan Offers Mixed Bag of Sacred, Secular Music.” Cincinnati Enquirer (6 November 1981): C-9.

Shakespeare, William. A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Arden Shakespeare Third Series, ed. Sukanta Chaudhuri. Bloomsbury, 2017.

Sounes, Howard. Down the Highway: The Life of Bob Dylan. Grove Press, 2001.

Stanislavski, Constantin. The Actor Prepares, trans. Elizabeth Reynolds Hapgood. Routledge, 1964.

Starr, Larry. Listening to Bob Dylan. University of Illinois Press, 2021.

Stevens, Dale. “Bob Dylan: The Elder Statesman.” Cincinnati Post (5 November 1981): 1B.

Tenschert, Laura. “Episode 38: A Tribute to Clydie King.” Definitely Dylan (13 January 2019), https://www.definitelydylan.com/listen/2019/1/13/episode-38-a-tribute-to-clydie-king.

Weikel, Frank. “Dylan Finds City Is Tops in Hat Dept.” Cincinnati Enquirer (14 December 1981): C-1.

Williams, Paul. Dylan—What Happened?. and books/Entwhistle Books, 1979.

---. Bob Dylan, Performing Artist, 1974-1986: The Middle Years. Omnibus, 2004.

Graley - I am hopelessly behind in my Dylan content including yours (the rest of my life keeps interfering) and just got the chance to sit down and give this the attention it deserves. This is amazing. I can’t explain why but at times when you took us through the performances I had tears in my eyes. Laura has said so much above I don’t need to add anything but bravo!

That was such a fun read! Not for the first time it struck me how much these pieces on Dylan’s concerts through the years carry on the spirit of Paul Williams. Like him, you transport us directly into the audience. But the thing is, when I first read Paul Williams, the fact that he was describing recordings I hadn’t heard was both exciting (so much out there for me yet to discover), and frustrating (how could I get my hands on them??). So your decision to publish these pieces on Substack, as well as your generosity to include the recordings in the text, means that we can hear them as well as read about them, and the effect is much more than the sum of its parts: it allows us to be right there with you. I’m glad you’ve decided to share your thoughts on Cincinnati Dylan in this way!

What a fascinating concert, due to the length alone, but also because the concerts in the early 80s are such emotional rollercoasters: the push and pull between sacred and secular music always has you wondering where his head and his heart are at. That version of Simple Twist of Fate is incredible – somehow both driving and urgent, as well as light and breezy. And speaking of Paul Williams, I can’t think of a more beautiful way to describe Dylan’s vocal than as the “vehicle for the expression of the group heart”. So good! As you know, I always love your writing about Clydie King and the way you articulate her immense importance for Dylan’s performances and the group sound (and thanks for the generous shoutout). That performance of I’ll Be Your Baby Tonight is wonderful - It’s not just that her vocals bring a real soul sound, but sometimes I feel like Clydie out-Bobs Bob – not just is her phrasing so free, but she just has that “coolness” that Dylan embodies, and she not only meets him there, but pulls him further in. No idea if that makes sense, but that’s how it felt listening to this song, which really works astonishingly well as a duet, although it feels more like a dance.

Side note: I need to know which hats Bob bought at Batsakes.

I love the theatrics of the band playing one song without him (and what a performance that is!!), and then his return to the stage basically starts from scratch, just Dylan, and then slowly the rest of the band reassemble, it’s so effective, and gives him both an opportunity to breathe, but also to change tone completely before ramping things up again. I LOVE that version of Dead Man Dead Man. I’ve long been obsessed with the live version from New Orleans little more than a week later (10 November – it's on a Japanese live compilation I found years ago), but this one is just as great. I had never heard that version of “When He Returns”, and it completely blew me away. I’m fascinated with the choice to change the arrangement so drastically. You describe hearing Dylan finding his way in unfamiliar waters, which makes total sense, but my impression was almost the opposite. The best way I can describe it is that in the arrangement of the early days, it was like Dylan was singing a gospel song, but here, it sounds like he’s turned it into a Dylan song? It’s more blues, more r&b, more rock n roll – and that, to my ears, puts Dylan vocally in his comfort zone, where he can experiment where to take the song within these more familiar parameters. So even though he and the band are working out the song on the spot, Dylan was in his element. I love the repeated “When He Returns” at the end – like the song has left the church and is now on pop radio. Absolutely stunning and deeply moving!

Thanks for taking us along on this journey, Graley!