Dylan in Cincinnati: November 1965

Dylan Context

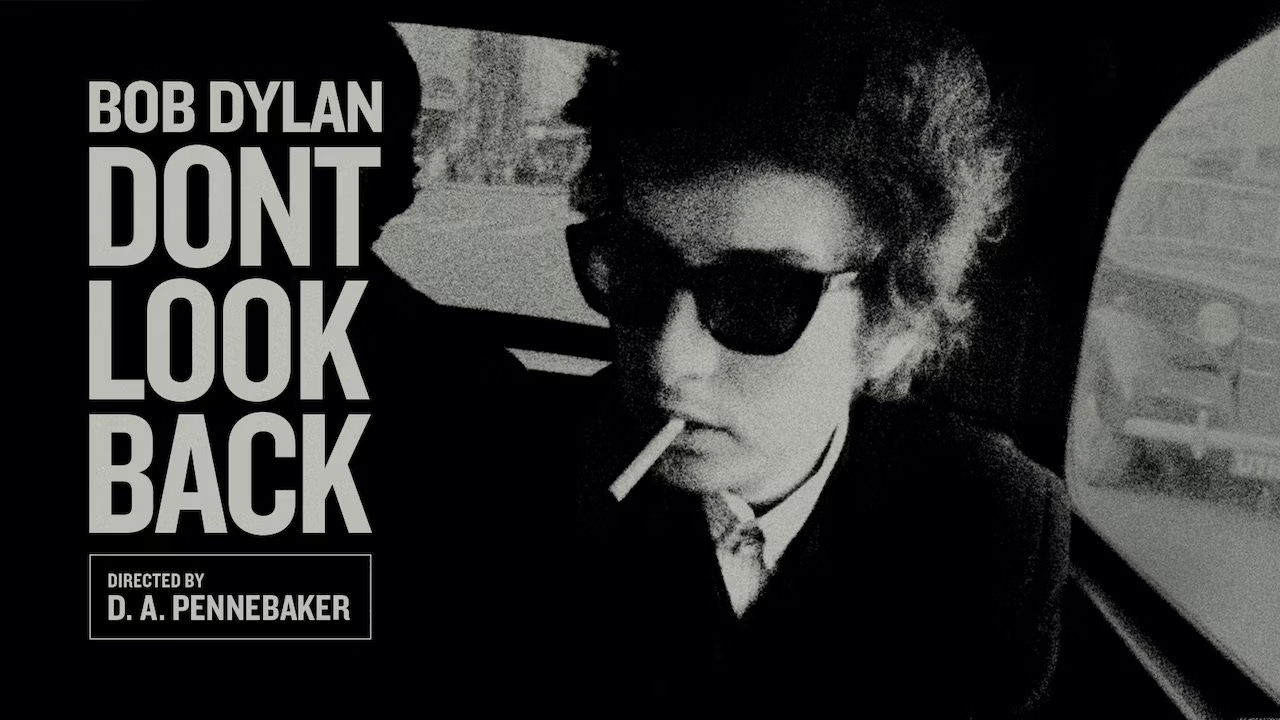

Between his March and November trips to Cincinnati, Bob Dylan radically reinvented himself as a performer and altered the course of popular music history. He released Bringing It All Back Home, the first album in his groundbreaking rock trilogy, on March 22. That spring he made his final solo-acoustic tour, culminating in the England concerts of April and May, captured for posterity in D. A. Pennebaker’s highly acclaimed documentary film Dont Look Back.

On July 25 he fired the shot heard ’round the musical world by “going electric” at the Newport Folk Festival, outraging folk purists who booed him off stage for allegedly betraying the movement and selling out. Or maybe the sound system just sucked. The details are disputed and are largely immaterial by now, long since supplanted by mythology.

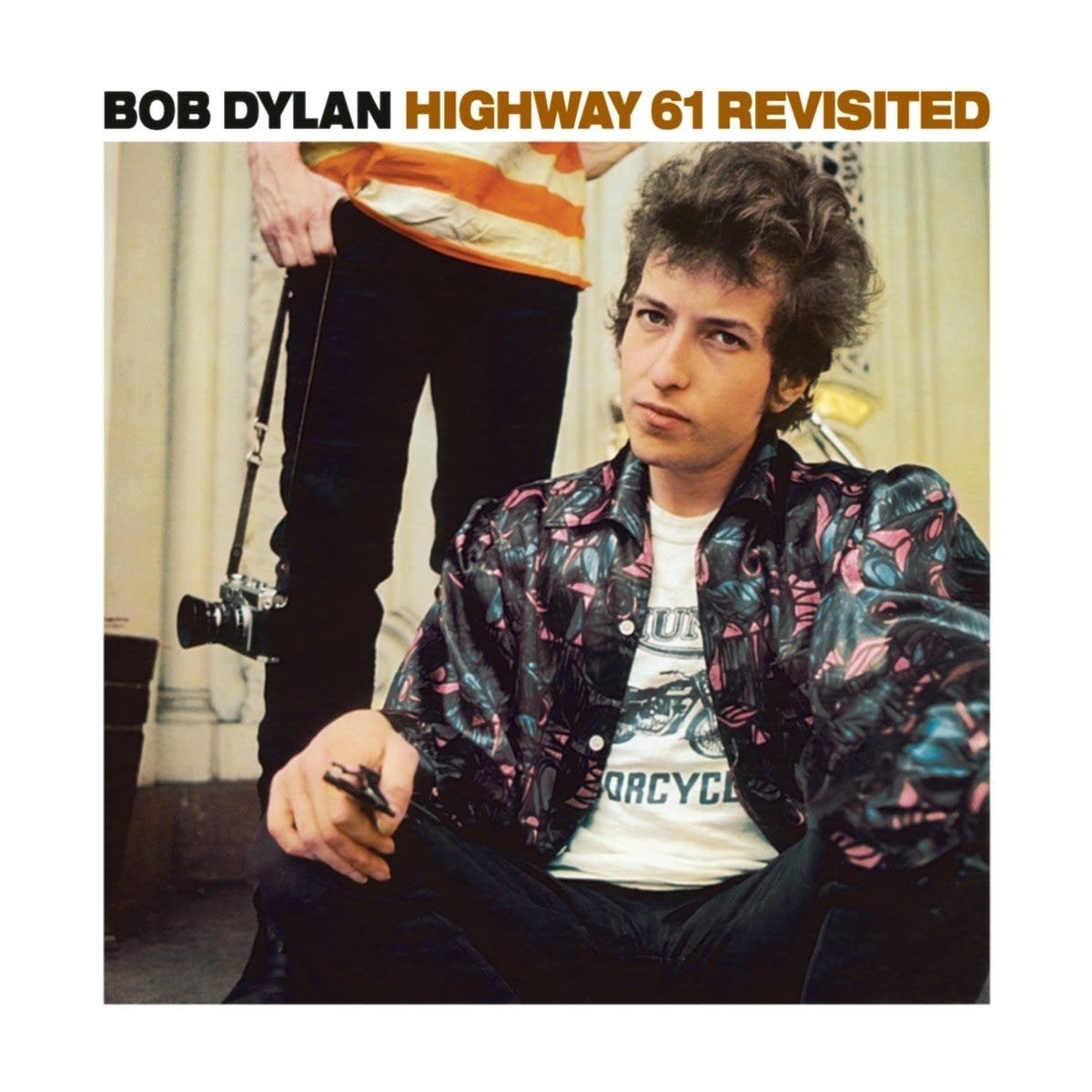

On August 30 Dylan released his first fully electric album, Highway 61 Revisited, opening with “Like a Rolling Stone,” one of the most influential rock songs of all time.

That fall he staged his first tour with a band, The Hawks, playing an acoustic set each night followed by an electric set which often met with hostile audience reactions. Dylan and The Hawks had played fewer than twenty shows together by the time they appeared at Cincinnati’s Music Hall on November 7, 1965.

Any one of these achievements would have left a lasting legacy, but the cumulative impact of detonating so many depth charges in such a compact span of time was to turn Dylan from a star into a legend. The birthplace of the myth was Newport. This is where the Prince of Protest and King of Cool morphed into the Outlaw Hero: the crossroads where, depending on who is telling the story, Dylan became either a martyr or a traitor.

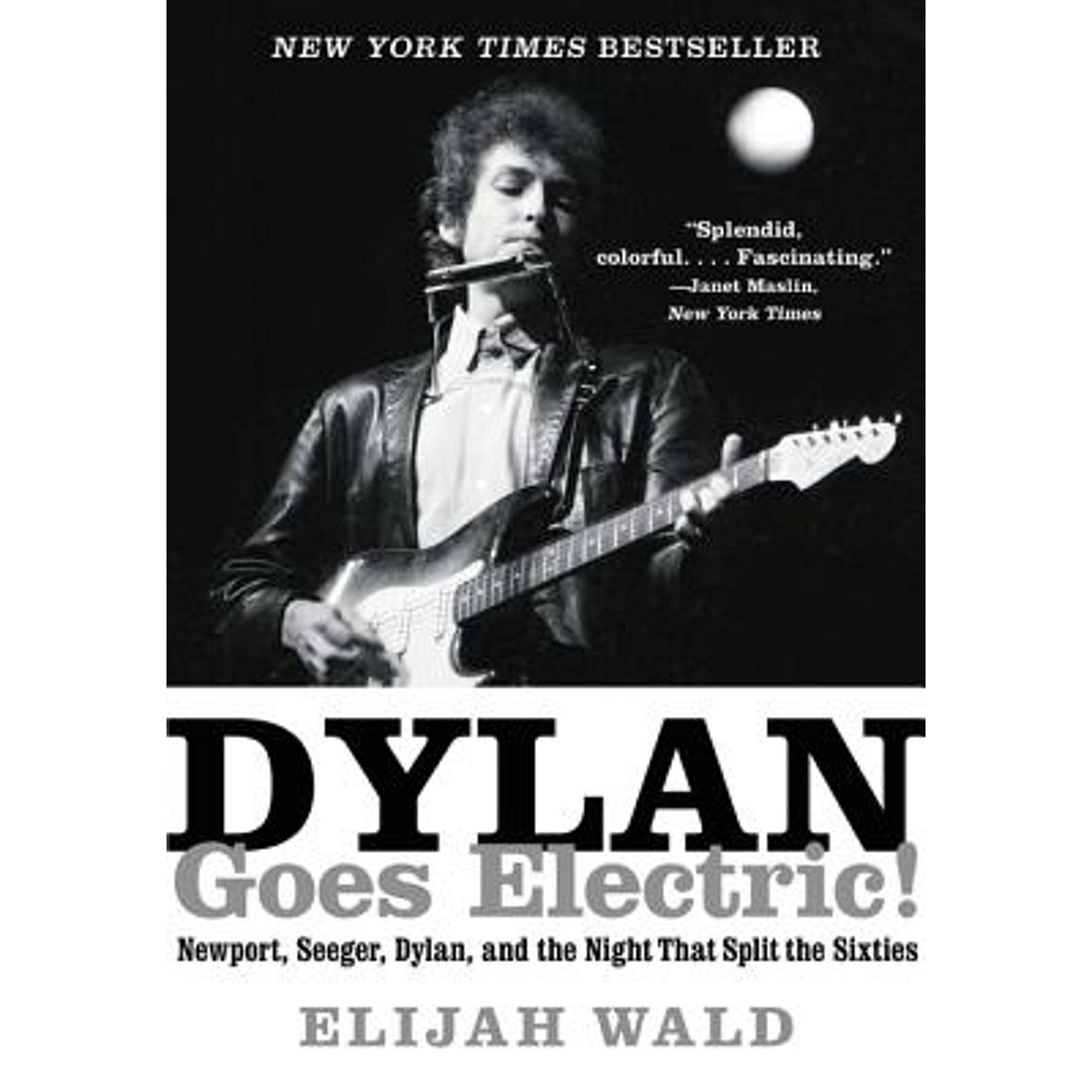

Elijah Wald does a great job of capturing the significance of Newport ’65 in his book Dylan Goes Electric! He explains, “Dylan was the iconic voice of the decade famed for rebellion and Newport was the epochal break of the young rocker with the old society that would not accept him” (2). For those who supported Dylan plugging in and expanding his artistic potential, Newport ’65 consecrated his role as “the decade’s existential hero, ramblin’ out of the west, wandering the midnight streets of Greenwich Village, jotting angular words at scarred tables in crowded cafés, roaring down the road on a motorcycle, sauntering onto stage, or striding off, ready or not” (Wald 2).

However, for those who shared Pete Seeger’s ideals, folk music was all about communal principles, “bringing people together, providing them with a shared message, and reminding them that the good fight could also be a source of satisfaction and even fun. When things got tough, songs were supposed to keep the young rebels focused and united, not encourage them to wander off into the jingle-jangle morning and disappear in the smoke-rings of their minds” (Wald 190). From that perspective, Dylan wasn’t a rugged individualist following his true calling: he was being selfish, crass, and careerist by turning his back on the cause.

In the context of the present study, what is most striking is Dylan’s power to elicit such extreme reactions from audiences—ranging from ecstasy to disgust—through the volatile precipitant of his live performances. He didn’t do it alone. He was accompanied on stage by Robbie Robertson on electric guitar, Rick Danko on bass, Richard Manuel on piano, Garth Hudson on organ, and Levon Helm on drums—a group that later became famous in their own right as The Band.

Dylan apparently first learned about the unit, then known as The Hawks, from mutual friends Mary Martin and John Hammond, Jr. After going electric, he was looking for a drummer and guitarist to back him at gigs in New York and California. The Hawks were a seasoned bar band who had played the Toronto circuit for years. At the time of Dylan’s recruitment, they were holding down a three-month residency at Tony Mart’s in New Jersey. In his memoir This Wheel’s on Fire, Levon Helm bragged, “Truth was, the Hawks were the band to know about back then. It was an ‘underground’ thing, if you know what I mean. We were like a state secret among hip musical people because nobody else was as tight as we were” (129). Helm and Robertson debuted behind Dylan at the notorious Forest Hills concert on August 28, 1965, and then backed him at the Hollywood Bowl on September 3. When manager Albert Grossman scheduled a tour for the fall of 1965, Dylan welcomed the rest of The Hawks into the nest as his road band.

It may seem that the bandmates lucked out by hitching their wagon to a shooting star, and in the process etching their names in the annals of rock history. But at the time it was a damn tough gig. Most audiences on the fall tour included vocally irate fans who vented their anger and disappointment from the moment the band took the stage. As Helm reports, “We were booed everywhere; by then it had become a ritual. People had heard they were ‘supposed’ to boo when those electric guitars came out” (138). Robertson remembers it this way in his memoir Testimony: “They booed, chanted, and hissed; sometimes they even charged the stage or threw things at us. I joked at the time that I learned how to play guitar without looking at my fingers because I was so busy dodging flying objects. It was harsh” (191).

The hostility gradually wore Helm down and made him second-guess his decision to tour with Dylan. “I began to think it was a ridiculous way to make a living: flying to concerts in Bob’s thirteen-seat Lodestar, jumping in and out of limousines, and then getting booed” (Helm 138). Dylan stood strong in the eye of the hurricane, and Helm was deeply impressed by his stamina and resolve: “I couldn’t have taken what Bob endured. We seemed to be the only ones who believed in what we were doing. But the guy absolutely refused to cave in. It was amazing, but Bob insisted on keeping this thing together” (139). Soon, however, he would have to keep it together with a new drummer. Helm stuck it out for the American fall tour (including the Cincinnati Music Hall concert), but he quit before the European leg of the tour the following spring. The rest of the band soldiered on. As Robertson put it, “We were in the midst of a rock ’n’ roll revolution; either the audience was right, or we were right” (191).

History’s verdict is in: Dylan and his band of revolutionaries were right. They ultimately won the war. But triumph was by no means assured at the time, as they roamed the country and the world, waging battles night after night with their own audiences.

Cincinnati Context

The racial animosities that made the Cincinnati region a powder keg in the 19th century did not magically disappear with the end of the Civil War. On the morning of Dylan’s second concert in town, the Enquirer included a front-page story headlined “Klan Rallies in Ohio after Indiana Rebuff.” The piece opened: “The Knights of the Ku Klux Klan burned a cross Saturday night on a farm five miles east of here as part of a rally that had been scheduled for Indiana but was moved as a result of a court order. Warren County Sheriff’s deputies said they had no trouble reports from Parkie Scott’s farm near Interstate 71, but Associated Press photographer Gene Smith said he was barred from the site at gunpoint” (1). For decades Parkie Scott remained a notorious local figure whose farm served as a KKK hub. A 1993 Enquirer exposé of Klan activities in the region included a profile of Parkie Scott. The report mentioned the 40-foot cross and giant Confederate flag painted on the roof of his barn, both clearly visible to passersby on I-71. Scott was quoted defending his allegiances: “I’ll never retire from working for a Christian organization. I’ll work as long as I live for Christianity and the good of the country” (A-6). Several months after the November 1965 cross-burning incident, Scott sponsored another Klan rally to celebrate America’s Independence Day. A brief notice in the Enquirer reported: “Crosses will be burned Saturday, July 2, and Monday, July 4, according to Mrs. Parkie Scott. ‘We never burn crosses on Sunday,’ Mrs. Scott explained” (47).

The Enquirer depicted the racist Klan in a critical light, yet the editors seemed utterly oblivious to their own casual sexism. The front page reprinted an Associated Press story from London titled “Take It from the Top: Easy to Tell Big Girls’ from Little Ones.” It opened: “In Britain, women’s skirts get shorter, men’s eyes get bigger, and customs officers’ faces get longer. Their problem? The long and short of it is that they can’t tell the difference any more between a dress designed for a woman and one for a child. The difference is vital, because they have the duty to stick a 10% sales tax on women’s dresses. Children’s clothing is exempt” (1). The anonymous cad who wrote the piece offered this solution to the problem: “The answer: Lift up your eyes from the hemlines and try measuring the bust-lines” (1). This gleefully unabashed sexual objectification of women (and children) was on the front page of the Cincinnati Enquirer on November 7, 1965. The editors apparently deemed breast ogling to be as newsworthy as cross burning for the Sunday morning edition of the city’s most prominent paper. Welcome back to Cincinnati, Mr. Dylan!

On a more genuinely uplifting note, it was an amazing time to be a music fan in Cincinnati. The previous night, James Brown and The Famous Flames played an incendiary show at the Cincinnati Gardens.

As of Sunday morning, some tickets remained available for Dylan’s concert that evening, ranging from $2.50 to $4.50 a seat.

The entertainment page also included ads for upcoming shows which read like a who’s who of sixties popular music. The following Friday the Cincinnati Gardens hosted a revue billed as “The Biggest Show of Stars for ’65,” featuring The Temptations, The Four Tops, Stevie Wonder, Martha and The Vandellas, Jr. Walker and His All Stars, The Marvelettes, and The Spinners.

If you could hop into a time machine, you could go back and see them all for just $1.75. While you’re at it, might as well stick around until November 27, when you could have paid $2.50 to see The Rolling Stones (with Patti La Belle and The Blue Belles opening) at the Gardens in only their second American tour.

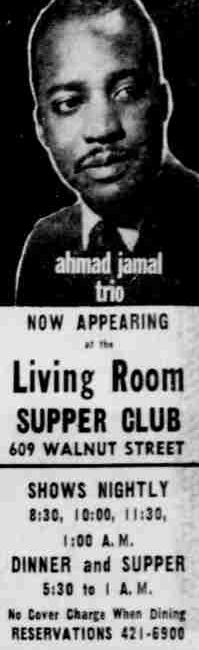

If rock and soul were not your style, you could wander over to the Living Room Supper Club downtown where the great jazz pianist Ahmad Jamal (2017 Grammy for Lifetime Achievement) was in residence with his trio.

While you’re enjoying Cincinnati nightlife, why not take in a play? A traveling Broadway production of The Subject Was Roses was beginning its run the following week at the Shubert Theatre, co-starring 25-year-old Martin Sheen, who hails from just up the road in Dayton, Ohio.

All of these options were available to Cincinnati art lovers in November 1965. But hey, we all know which show we’re really here for.

Concert at Music Hall

Music Hall is one of the finest jewels in the Queen City’s crown. This majestic building is located beside Washington Park in the neighborhood of Over-the-Rhine, and it is home to the Cincinnati Opera, the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra, the Cincinnati Pops Orchestra, and the long-running annual May Festival. Music Hall opened to great fanfare in 1878, and ever since it has played an important role in the community in various capacities.

Along with providing the most ornate setting and finest acoustics for music in the city, Music Hall has also hosted political conventions, industrial exhibitions, sporting events, dance clubs, posh celebrations, and memorial services. The University of Cincinnati’s College of Engineering and the nationally renowned Cincinnati College of Music both started there, and WCET (the first educational television station in America) originally broadcast from there. As Luke Feck tallies in his introduction to a centenary celebration of Music Hall, “William Jennings Bryant spoke there, Billy Sunday preached there, Buster Crabbe swam there, Gorgeous George wrestled there, and thousands of corsaged teen-aged girls went to proms there” (10-11).

Music Hall has other unsavory associations, however. In his account of the bloody Court House Riot of 1884, Zane L. Miller recounts how a protest meeting at Music Hall, “voicing public indignation at the sentences meted out in a murder case, led to rioting in which some 50 persons were reported killed and over 200 injured, and to the burning of the courthouse” (36).

By the mid-sixties when Dylan arrived, Music Hall stood as a point of civic pride for some Cincinnatians and an emblem of social inequality for others: a lavish palace attracting the city’s elite for evenings of leisure and jewelry rattling, situated in the heart of Over-the-Rhine, one of the most impoverished neighborhoods in the city. OTR residents share a neighborhood with Music Hall while effectively inhabiting a completely different world than its patrons. On one hand, this elegant home for classical music may seem an unlikely venue for Dylan to go electric in Cincinnati. This was in fact the first rock concert ever been performed at the venerable institution. On the other hand, its combination of grandeur, variety, vitality, and controversy made Music Hall the ideal setting for Dylan’s traveling revolution of 1965.

As with the March show at the Taft, no bootlegs and no setlist survive from the Music Hall performance in November. Dylan’s concert lineup seems to have been fairly stable at the time, however, so we can speculate with reasonable confidence that the acoustic set included mostly songs from Another Side of Bob Dylan and Bringing It All Back Home, bypassing the protest anthems for which audiences still hungered but which Dylan had tired of feeding them. The electric set would have featured several songs from the hard-rocking Highway 61 Revisited released a couple months prior, as well as electric band arrangements of songs he had previously played solo acoustic like “Baby Let Me Follow You Down” and “I Don’t Believe You (She Acts Like We Never Have Met).” The evening most likely concluded with his breakthrough hit “Like a Rolling Stone.”

Although I haven’t discovered any recordings, apparently the band taped the shows on this tour, so perhaps some hidden gems remain locked away somewhere. Levon Helm attests, “We made tapes of the shows and listened to them afterward in the hotel, because we couldn’t believe it was that bad that people felt they had to protest, but the tapes sounded good to us. It was just new” (Helm 138). Robbie Robertson confirms that the band studied concert tapes, both to improve their performances and to reassure themselves that the booing was unjustified. He adds, “Still, the audiences didn’t seem to notice or care how much better we were getting. They came to these shows with their minds already made up” (Robertson 191).

Did the Cincinnati audience boo? It depends on who is telling the story. Stu Levy says no. He was a University of Cincinnati undergraduate who attended the concert and took some fantastic front-row photos of Dylan and the band in performance. I spoke with him by Zoom from his home in Portland, Oregon, and he assured me that he heard no booing and registered no negative reactions from the crowd. Larry Patterson told a different story. He covered the concert for the University of Cincinnati News Record, and he reported a backlash during the electric set: “The audience, somewhat disappointed, to say the least, by a faulty sound system, was often noticeably disappointed by the second half of the show in which Dylan sang with a band. But seeing the unique and sometimes obviously exhibitionist types in individuals that attended was a treat in itself. However, this must be recorded as one of Dylan’s worst performances vocally, and the capacity audience indicated openly their disappointment with their idol in his new capacity.”

Dylan himself said his concerts were better received in the Midwest and South than elsewhere. Asked during his December 1965 press conference in San Francisco about the booing, he replied, “They’ve done it just about all over except in Texas . . . and they didn’t boo us in Texas, or in Atlanta, or in Boston or in Ohio. They’ve done it in just about . . . or in Minneapolis, they didn’t do it there. They’ve done it in a lot of other places. I mean, they must be pretty rich to be able to go someplace and boo. I couldn’t afford it if I was in their shoes” (245). What a drag it would be to stand inside the shoes of a deluded heckler at such earth-shaking, epoch-making performances. Did the Elm Street audience at Music Hall go Fourth Street and turn against Dylan? These Rashomon accounts leave the answer uncertain.

As in March, the intrepid Dale Stevens was on the scene to cover the November concert. He regarded Dylan’s appearances as major events in the cultural life of the city and devoted two articles in the Cincinnati Post and Times-Star to the subject. In his first review, Stevens compared James Brown’s Saturday night show at the Cincinnati Gardens with Dylan’s Sunday night show at Music Hall. If Dylan was “the voice of his generation,” then Brown was “the hardest working man in show business,” a title he successfully defended at the Gardens.

Brown was by far the most popular artist on the local King Records label. He played Cincinnati regularly and was the biggest musical celebrity in town. His bass player at the time was Tim Drummond, who would go on to play with Dylan in the studio and on the road during the late seventies and early eighties. James Brown and The Famous Flames were seasoned live performers, and according to Stevens they drew more than twice as many fans (6,500) at the Gardens as Dylan and The Hawks did at Music Hall (3,000).

Stevens once again credited Dylan for his poetic prowess. But he also remained unnervingly fixated upon the young artist’s eccentric looks: “Dylan not only writes deep, literate lyrics and sings them with a sing-song ‘olive’ voice (one that has to grow on you) but he has lengthy feminine styled hair and a slender physique to go with his obvious poet’s sensitivity” (13). Maybe I’m showing my 21st-century sensibilities here, but this description sure sounds chauvinistic to me. The simplistic gendered terminology bothers me, sure; but it’s also the ease with which such remarks are delivered, seemingly without malice yet dripping with condescension, secure in the knowledge that he can mock Dylan’s unmanliness with complete impunity and only expect a sympathetic chuckle from his readers in response.

Stevens was a lousy fashion critic, but he was a keenly perceptive music critic as well as a useful barometer for shifting tastes during this transitional moment in Dylan’s career. His second review focused exclusively on the Music Hall concert, where Stevens had high praise for Dylan’s solo acoustic set. “In his concert Sunday, he did the first half as the Dylan of old—alone on the stage with his folk guitar and assortment of harmonicas. You could hear every word plainly, and with Dylan the words are all” (22). In “My Back Pages,” Dylan sings, “Ah, but I was so much older then / I’m younger than that now.” Stevens clearly preferred the “older” artist, the poet laureate of protest, and he had nothing but superlatives for that side of Dylan: “It requires the test of time to put the ‘great’ label on anything. Yet Dylan has come close in two seasons’ time to proving his greatness as a writer of poetic folk music” (22).

Stevens was more skeptical of the newer, younger, louder Dylan. Like many fans disappointed with the new sound, Stevens felt the poetic effectiveness of Dylan’s words decreased in direct proportion to the increased decibels of the band’s music: “Their volume almost drowned out Dylan’s voice, and the fact that Bob displayed a certain exuberance, or spirit, by moving around more, or raising a leg in reflex, might be an indication of his personal liking for the music but it did little to get his message through to the audience” (22). Stevens was no square and no purist. He appreciated Dylan’s talent as a performer, even as he doubled down on his preference for songs he could understand:

My feeling is that Dylan is not so much the purist the folk purists want him to be; but is an honest performer with an awareness of how to reach the large general audience. […] Dylan already has influenced the entire rock-and-roll field which has picked up on his songs to create the new folk rock. And it’s interesting to watch him do that same style of folk rock without the manufactured mannerisms. With Dylan, while he’s playing amplified guitar with a gang behind him, you get no large smiles and choreography. He gives it the same no-hokum approach as he does his straight folk performance. The only problem I see is that it doesn’t add to his songs, it detracts. I feel I got his message in folk music. In folk rock I can’t even hear it. The words can’t get through the din. (Stevens 22)

Stevens walked into the dressing room with his pencil in his hand for a backstage interview with Dylan. Not surprisingly, the artist disagreed with the critic about the new music being a distraction. Stevens reported: “Obviously he plays rock-and-roll, or his folkish version of it, because he enjoys it. To him, it augments what he has to say” (22). Dylan downplayed the negative reactions from fans that summer in Newport and Forest Hills and didn’t mention the resistance he periodically encountered during the current fall tour.

Stevens wasn’t sure what to expect from the interview, given the icon’s reputation for clashing with the media. Dylan was apparently in a gracious mood, but I don’t know how he kept his cool when Stevens (again!) made light of his bizarre looks: “Dylan, though reportedly strongly anti-press, was very nice to me. We talked about his hair, well past his neck in back, frizzy over his forehead, very much in female style” (22). How tiresome and lame. Dylan shrugged off this tactless effrontery with humor, though the interviewer seemed not to get the joke: “He said he had worn it far longer, below his shoulders five or six years ago—indicating, of course, that he was unorthodox as an unknown and has not adopted trick appearance to enhance success” (22). Or indicating that he was pulling your leg, Mr. Stevens.

The critic closed with an overall assessment doubtlessly intended as praise, but it comes across as cloyingly patronizing by today’s standards:

Despite his nonconformist look, he is, in person, quiet, friendly and normal—a word I use only in the sense that there is no falseness, no put-on, no fakery in his manner. The sensitivity manifest in his lyrics is an overtone in his personality. Like most artists, the giant who speaks for his generation is a reachable, genuine, nice guy. Somehow it helps to know that. (Stevens 22)

To me this passage reads like the Novak Djokovic of backhanded compliments. I ain’t sayin’ the Cincinnati press treated Dylan unkind, but it could’ve done better, and I mind.

Apparently Dylan thought twice about it, too. At his San Francisco press conference the following month, he complained about being misrepresented by journalists. Asked for examples of when and where this had happened, Dylan replied, “But this is just for interviews you know, when they do want interviews in places like Omaha, or in Cincinnati, man, you know. I don’t do it, and then they write bad things” (242).

That’s your cue to enter, Ruth Voss. I should first point out that Ruth Voss went on to do important philanthropic work in the community as a founder of New Life for Girls (now Lighthouse Youth & Family Services), a halfway house providing housing, training, and social services for Cincinnati women since 1971. The seed money for this agency came from President Richard Nixon. He was so impressed with Voss when he met her at the White House that he donated $50,000 to her cause.

In his speech the next day to the National Federation of Republican Women, President Nixon commented, “Then yesterday, while you were taking your tour of the White House, another lovely lady came to see me. She was from Cincinnati, Ohio—Mrs. Ruth Voss, the mother of eight children. She worked for the Cincinnati Enquirer. Incidentally, whenever I get discouraged with the Washington Post, I read the editorials in the Cincinnati Enquirer.”

In 1965 Voss was editor of the Enquirer’s teenager section. In that capacity she was lured to Music Hall by the prospect of an interview with Dylan during the concert’s intermission. Voss proudly paraded her disinterest in Dylan’s music and her disdain for the decadence she saw that evening. She titled her piece “Looking around a Lobby,” but she might as well have recycled the 1964 Enquirer headline for The Beatles: “Young Fans Drop Veneer of Civilization.”

Of the 3000-odd young people who filed through Music Hall’s ornate, usually sedate lobby Sunday night to hear their idol, Bobby Dylan, at least 2500 of them certainly were odd. Standing and watching in disbelief alongside Roger Pellens, Music Hall manager, I saw at least a dozen barefoot boys, two more barefoot but wearing sandals, a number of girls in ‘granny’ dresses, countless motorcycle outfits complete with goggles, hoods, and high-heeled boots, one girl in a gold brocade formal and flats, four girls in bell-bottom pants and boots, and even one fellow in a long, black flowing cape. (Voss 2)

Voss never even attempted to engage with Dylan’s performance or with the substance of his songs. She took it as a given that there was nothing happening on stage worth her attention, so instead she turned her opera glasses toward the strange creatures prowling around the lobby, as if she had mistakenly wandered into the Cincinnati Zoo instead of Music Hall. “It seemed like every other one of these oddballs was smoking, and not more than a handful looked as though they had ever seen the inside of a barbershop. To top it all off, I was lucky enough to be in the same box with a 16-year-old kook who not only was barefoot, but draped those bare feet over the railing during the performance” (2). Mrs. Viel seems like a paragon of impartiality and restraint compared to Mrs. Voss—who, lest we forget, was employed as a professional journalist and sent to cover the concert for the biggest newspaper in Cincinnati.

But give Voss credit for knowing her readers, most of whom were sure to share her sense of hilarity and repugnance at the sight of Dylan’s uncivilized followers. Voss was quite open about her motives for being there: “I only sat through the first half of Mr. Dylan’s concert because it had been suggested he might grant an interview with three of our ‘Teen-ager’ reporters during intermission. (It would have been cheaper to stay home and listen to my cat and dog fighting). But when his road manager said he would see none from the press that night, I bit my tongue to keep from saying what I really felt about the whole miserable affair” (Voss 2). In other words, she flew the coop before The Hawks ever took flight. Exit Ruth Voss.

Before closing her column, she fired off a couple parting shots at the crowd: “I wonder where these beatniks hide during the week. You seldom see them on the street. I also wonder what our fighting men in Vietnam would say at the sight of these teen-age protesters? They weren’t carrying signs, but that’s about all they weren’t doing!” (Voss 2). Here the subtext underlying the review rose unmistakably to the surface. Voss was clearly hawkish on the Vietnam War if not on Dylan and The Hawks. As for the cultural insurgency they incited off stage, Voss could tell a Hawk from a handsaw. The Music Hall hooligans didn’t need to carry banners to make their allegiances known. They let their freak flags fly with their hair, clothes, footwear (or lack thereof), and disregard for the conventions of polite society—all signs of unpatriotic, anti-American values. Nixon’s “silent majority” speaks loudly and clearly in the voice of Ruth Voss.

The losers in 1965 would be later to win. Elijah Wald depicts the musical rebellion as a harbinger for the larger generational transition of power: “When Dylan shouted his electric refusal to work on Maggie’s farm, it was a declaration of independence for what was not yet known as the counterculture. The politics of words and manifestos were being supplanted by a politics of clothing, hair, sexuality, drugs, and music” (Wald 300).

Dylan going electric was the Fort Sumter flashpoint in a culture war. Newport was the first major clash in Dylan’s rock revolution, but he and his lieutenants would continue to fight skirmishes in the provinces, and Cincinnati was one of those battle sites in November 1965.

The kids staged a verbal counter-offensive a week later in the teen section of the Enquirer. Much like the young readers’ backlash against Mrs. Viel in March, several young people wrote into the paper to challenge Ruth Voss’s libel against them and Dylan. Voss reproduced several of these letters in her weekly column, slapping on the snarky heading, “Our Readers Gripe: ‘Square’ . . . ‘Narrow-Minded,’ They Say.” B. Sherman Nichols of Batavia noted how predictable her haughty diatribe had been: “I was one of those 2500 ‘odd’ people at the Bob Dylan concert. We affected you as is expected. You went there with a negative attitude. What you saw and heard added to your distaste for us. For you saw and heard us under the influence of the external values of society” (qtd Voss 2). Nichols also accused Voss of fundamentally misunderstanding the audience’s relationship with the singer-songwriter: “You were uninformed enough to call Bob Dylan our ‘idol.’ ‘Idol’ is one of the most overworked words used by adults in reference to teen-agers and their music. One screams at an ‘idol’; one listens to people who have something to say” (qtd Voss 2).

Maureen Mitchell also wrote in, identifying herself as a student at Our Lady of Cincinnati College (later Edgecliff College, which eventually merged with Xavier University). She began by noting that she usually enjoyed the paper’s teen section, but she was disturbed by coverage of the Music Hall show. “I’m surprised to find you so narrow minded,” objected Mitchell. “I was disappointed in your editorial on the Bobby Dylan concert. Why do you ‘put down’ those people only on what you saw?” (qtd Voss 2). Then Mitchell put her values-based education to good use by applying an ethical critique and an appeal to social justice: “My whole life teachers and parents have said, ‘Do what you think is right; don’t be ashamed; stick to your convictions.’ Then, if someone does, he is torn apart. If those people were bold enough to drop conformity, more power to them” (qtd Voss 2). And more power to you, too, Maureen Mitchell of Our Lady of Cincinnati College. Shake those windows and rattle those walls!

Yes, the times and Dylan were both changing radically. He may have alienated the hardcore folk nucleus of his fan base when he went electric, but in the process he significantly increased the size and scope of his audience, speaking to the disaffected masses through the lingua franca of rock ’n’ roll. As Wald asserts,

By 1965 Dylan was a millionaire dressed in fashionable clothes, and for a moment it seemed he might have sold out to the system, but the battle of Newport proved he was as untamed as ever. He was not capitulating to the present, he was breaking with the past—and if the mainstream rewarded his rebellion, that was because it was changing, not because he was. (Wald 300)

Dylan left his mark on Cincinnati, as he did in so many places in 1965, and then he pointed his caravan forward and headed down the road. Thirteen years would pass before he returned to the city, and by then both Dylan and Cincinnati had undergone enormous transformations yet again. Fortunately, from that concert onward, someone thought to smuggle in a recording device to document these important performances. In the next installment of the Dylan in Cincinnati series, we’ll step back into the time machine and take a trip upon Dylan’s magic swirling ship to 1978.

Works Cited

Dylan, Bob. KQED San Francisco Press Conference (6 December 1965). Every Mind Polluting Word: Assorted Bob Dylan Utterances. Ed. Artur Jarosinski, Don’t Ya Tell Henry, 2006.

---. “My Back Pages.” Another Side of Bob Dylan. Columbia, 1964.

“Faces of the KKK: Parkie Scott, Oregonia.” Cincinnati Enquirer (24 January 1993), p. A-6.

Feck, Luke. Cincinnati’s Music Hall. Jordan & Company, 1978.

Helm, Levon, with Stephen Davis. This Wheel’s on Fire: Levon Helm and the Story of the Band. Chicago Review Press, 1993.

“Klan Rallies in Ohio after Indiana Rebuff.” Cincinnati Enquirer (7 November 1965), p. 1.

Levy, Stu. Personal Conversation with Graley Herren. Zoom. 19 May 2022.

Miller, Zane L. “Music Hall: Its Neighborhood, the City and the Metropolis.” Cincinnati’s Music Hall. Jordan & Company, 1978.

“Never on Sunday.” Cincinnati Enquirer (24 June 1966), p. 47.

Nixon, Richard. “Remarks at the Convention of the National Federation of Republican Women” (22 October 1971). The American Presidency Project. https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/remarks-the-convention-the-national-federation-republican-women.

Patterson, Larry. “Dylan Discusses ‘New-Style Sound.’” University of Cincinnati News Record (11 November 1965).

Robertson, Robbie. Testimony. Crown Archetype, 2016.

Stevens, Dale. “James Brown and Bob Dylan: Unique,” Cincinnati Post and Times-Star (8 November 1965), p. 13.

---. “The Two Sides of Bob Dylan.” Cincinnati Post and Times-Star (9 November 1965), p. 22.

“Take It from the Top: Easy to Tell Big Girls’ from Little Ones.” Cincinnati Enquirer (7 November 1965), p. 1.

Various advertisement from Cincinnati Enquirer (7 November 1965), p. 5-F.

Voss, Ruth. “Looking Around a Lobby.” Cincinnati Enquirer (13 November 1965), p. 2.

---. “Our Readers Gripe: ‘Square’ . . . ‘Narrow-Minded,’ They Say.” Cincinnati Enquirer (20 November 1965), p. 2.

Wald, Elijah. Dylan Goes Electric! Dey St., 2015.

I was at that 1965 Music Hall show. I don't remember any booing or significant sound problems. In fact, I was amused when, in their rendition of "She Belongs To Me", he changed the lyric from "She wears an Egyptian ring..." to "She wears a ruby red ring..." for no apparent reason. I'd never heard an artist change a lyric before and for no reason. Thanks for this comprehensive insight into the whole scene. Larry Butler