A quick update on plans for Dylan in Cincinnati. I announced in the introduction that this would be a selective study of Dylan’s 19 concerts in the Cincinnati area. That number will be increasing soon, since Dylan has announced his return to the Queen City for his 20th concert on October 20th at the Andrew J. Brady Music Center downtown. I’ve got my ticket! As for my decision that Dylan in Cincinnati will be selective rather than exhaustive, I still think that’s the best route. But as I approach my first skipped concerts, I’m having some misgivings.

In my last piece on Riverbend ’89, I announced that next we’d be skipping ahead to the 1999 Bogart’s show. Since then, I went back and listened to the 1992 concert at Music Hall. Mamma mia! There are some really great performances in that concert—too important to leapfrog over. So I’m calling an audible and a-courtin’ that leapfrog with this previously unscheduled piece for readers of Shadow Chasing.

Dylan Context

Dylan devoted his greatest time and energy to live performance in the nineties, playing an average of over a hundred shows per year throughout the decade. But if you weren’t keeping up with the Never Ending Tour and only paid attention to his recording output, the nineties can seem like mostly lean years. He started the decade with the poorly received under the red sky (1990), and it would be seven years before he released another album of original material. However, he did put out two albums of sensitively interpreted and beautifully rendered folk and blues songs during this period: Good as I Been to You (1992) and World Gone Wrong (1993).

Over the course of his career, Dylan has periodically immersed himself in music written and first performed by others, probably just for pure pleasure, without any calculated careerist plan in mind. After wrapping himself in a cocoon of cover songs for a period, he invariably emerges from the chrysalis transformed, with fresh wings to carry him toward new art. He experienced this musical rejuvenation on The Basement Tapes after his motorcycle crash, and again on Self Portrait before his 1970s comeback, and again on Good as I Been to You and World Gone Wrong before his late-career renaissance, and again on his trilogy of American standards before Rough and Rowdy Ways.

In the present case, the butterfly’s wings were brand new. Columbia released Good as I Been to You in the U.S. on November 3, 1992—and Dylan played Cincinnati’s Music Hall that very same night.

Less than three weeks before Dylan played Cincinnati, he was fêted at Madison Square Garden in a star-studded extravaganza celebrating his 30th anniversary as a recording artist.

Dylan surely felt more in his element playing Music Hall on November 3rd than he did occupying the center ring at the “Bobfest” circus on October 16th. The bootleg evidence backs up that claim. In One More Night: Bob Dylan’s Never Ending Tour, Andrew Muir contrasts Dylan’s lackluster performance at “Bobfest” with his otherwise dependably strong concert performances that fall. “It was hard to believe that this was the same man who had croaked his way through his part at Madison Square Garden. Yet, how like Dylan it was to perform so poorly at a celebration of his career, and play so well either side of it. How like Dylan, too, to answer that bloated celebration of his incomparable writing talents by releasing an album of covers” (114).

At the risk of sounding overly self-promotional, I think that’s precisely why we need more studies like Dylan in Cincinnati. Dylan’s best performances often take place far away from the brightest spotlights and the orchestrated spectacles designed to showcase his preeminence. You’re much more likely to catch his genius in full bloom out on the road and in the provinces—say, on a random Tuesday night in Cincinnati in 1992.

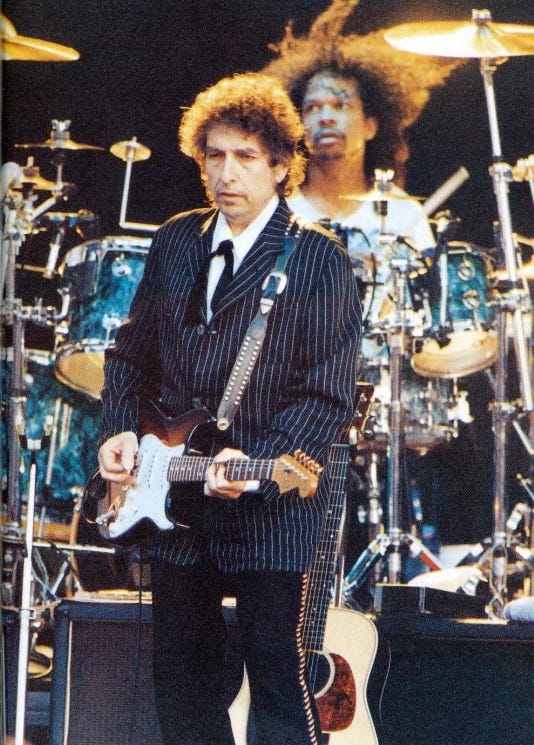

The NET is a collaborative effort. Dylan significantly retooled his lineup of collaborators in the interim between Riverbend ’89 and Music Hall ’92. With the original NET unit departed, Dylan expanded to a 6-member band. The sole holdover was stalwart bassist Tony Garnier. Alongside the general and his loyal lieutenant, the band at Music Hall consisted of guitarists John “J. J.” Jackson (who joined in early 1991), multi-instrumentalist Bucky Baxter (Spring 1992; poached from Steve Earle and The Dukes, who opened for Dylan at Riverbend ’89), and drummer Winston Watson (Fall 1992). There was a second drummer on the 1992 tour as well, Ian Wallace, who played with Dylan previously in the big band of 1978, including a memorable concert at Cincinnati’s Riverfront Coliseum.

According to Olof Björner’s statistics, Music Hall ’92 was only the 18th concert played by this group of six musicians. That’s enough times to have figured some things out, but few enough times to still be feeling each other out on a nightly basis. In other words, the Music Hall ’92 NET band was in the sweet spot where Dylan prefers to live as a performer, where beauty walks the razor’s edge between proficiency and precariousness.

Cincinnati Context

Like the rest of the nation and much of the world, all eyes in Cincinnati were fixed upon the presidential election. Dylan’s concert fell on election day. The heated contest pitted the Republican incumbent President George H. W. Bush against Democratic contender and Arkansas governor Bill Clinton. Texas billionaire Ross Perot also ran an independent campaign. Polls closed in Ohio around the time that local band Over the Rhine took the stage as Dylan’s opening act. By the time fans filed out of Music Hall that night, the country had elected a new leader, the third youngest president in American history.

Born in 1946, the 46-year-old Bill Clinton was the first Baby Boomer president. He was also a big Dylan fan. Clinton invited Dylan to play at his inauguration, where he sang “Chimes of Freedom” from the steps of the Lincoln Memorial—the same location where he sang during the March on Washington in 1963. Later that night, Dylan made a guest appearance at the “Absolutely Unofficial Blue Jeans Bash,” where fellow Arkansan Levon Helm and The Band (minus Robbie Robertson) served as house band for the gala. Dylan joined them to play “To Be Alone with You,” “Keys to the Highway,” and “I Shall Be Released.”

President Clinton later presided over Dylan’s Kennedy Center Honors in 1997, a recognition for distinguished lifetime contributions to American culture. On that occasion Clinton said of Dylan, “He probably had a bigger impact on people of my generation than any other creative artist.” Clinton also owns one of Dylan’s ironwork gates, a gift he received for his 65th birthday in 2011. He tweeted a picture of the gate along with his congratulations when Dylan won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2016.

The Concert

When: November 3, 1992

Where: Music Hall

Opener: Over the Rhine

Band: Bob Dylan (vocals, guitar, and harmonica); Bucky Baxter (pedal steel guitar and electric slide guitar); Tony Garnier (bass); John Jackson (guitar); Ian Wallace (drums); Winston Watson (drums and percussion)

Setlist:

1. “I Can’t Be Satisfied”

2. “If Not for You”

3. “All Along the Watchtower”

4. “Positively 4th Street”

5. “I Want You”

6. “I and I”

7. “Silvio”

*

8. “Mama, You Been on My Mind”

9. “Boots of Spanish Leather”

10. “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue”

11. “Desolation Row”

*

12. “Unbelievable”

13. “Every Grain of Sand”

14. “The Times They Are A-Changin’”

15. “Maggie’s Farm”

*

16. “Shooting Star”

17. “Everything Is Broken”

18. “It Ain’t Me, Babe”

The 1992 concert marked Dylan’s fourth at Music Hall. It was also his third trip to Cincinnati in the first five years of the Never Ending Tour. All three of these NET shows are remarkable, yet each is significantly different from the others in terms of material and approach. Of the 17 songs played at Music Hall ’92, 12 had not been played at either of his Riverbend shows, 10 were songs he had never played live in the city before, and 7 songs received their one and only Cincinnati performance in this show.

First Electric Set

Dylan comes out with a totally unexpected first song: “I Can’t Be Satisfied” by Muddy Waters. Well, it was unexpected unless you were keeping close tabs on the fall tour. Dylan had opened five of his previous six concerts with this song prior to the Cincinnati performance. He first played “I Can’t Be Satisfied” nine days earlier in Providence, and six days after Music Hall he played it for the last time in Sarasota. In those days of the internet’s infancy, few at Music Hall would have known this. For them, “I Can’t Be Satisfied” is as surprising as it is satisfying.

The opening cover fits with a pattern in this phase of the NET, when Dylan routinely began concerts with a revolving door of traditional folk, blues, and gospel songs. These are pieces he clearly loves, but he also seems to be putting the audience on notice: expect the unexpected. The singer declares, “I just can’t be satisfied,” and the sentiment applies on a meta-level, too. Dylan can’t be satisfied with exclusively playing his own compositions. He can’t be satisfied with just playing the greatest hits. And even when he does play some of those beloved anthems from the past, he resists self-imitation and declines to lead the audience in a nostalgic singalong. If you’ve made your way to Shadow Chasing, then you know this already, and respect Dylan’s inventive approach, and wouldn’t be satisfied with anything less.

The second spot on the setlist belongs to “If Not for You.” This is the first of several Dylan songs tonight that he had never played in Cincinnati before. In fact, this opening track from the album New Morning (1970) had never been played live anywhere by Dylan until the spring of 1992. The Music Hall rendition was only his ninth concert performance ever. “I Can’t Be Satisfied” features Dylan as musical archaeologist, excavating past music by others in search of buried treasure. “If Not for You” shows that there are still plenty of hidden gems worth digging up from his own backyard.

The addition of Bucky Baxter must have been one motivating factor for reviving this song. The mellow country vibe is right in Baxter’s wheelhouse. But it’s not all about Baxter. There is some lovely interplay with Jackson and Dylan’s guitars, too. And we all owe thanks to the anonymous taper. Music Hall has the best acoustics of any performance venue in Cincinnati, and the taper found the right position and equipment to capture a flawless recording.

I adore Dylan’s gentle vocals on “If Not for You.” This song is as unequivocal a statement of pure love as you’re going to find in his entire catalogue. Nothing cutting or sardonic or passive-aggressive here. Dylan knows how to write and sing songs of bitterness, betrayal, and recrimination better than anyone, but that’s not his headspace or soundscape on this sincere beatitude of thanks.

When Dylan stands on stage and sings, “Without your love I’d be nowhere at all / Oh! what would I do if not for you?” it feels like the “you” he has in mind is the audience in front of him. This musical exchange between singer and audience is mutually sustaining, fulfilling, and healing—how about we simply call it love. Dylan makes us feel his love, and the feeling is mutual. I’d go hungry, I’d go black and blue, I’d go crawling down the avenue to hear him sing “If Not for You” to me. But since that will probably never happen, at least I’ve got the Music Hall ’92 bootleg to experience that vow of love vicariously.

There is an interesting prelude to the third song, “All Along the Watchtower,” with lots of drums and cymbals from Wallace and Watson. This version sounds so different than the hard-rock renditions Dylan played in previous Cincinnati concerts. The Music Hall ’92 “Watchtower” is comparatively subdued, at least at first; not in the sense of being low-energy, but more in the sense of getting back to the foreboding mood of the original John Wesley Harding version before Jimi Hendrix forever reinvented the song. But this isn’t the JWH version either: it has more of a jazz-inflected fusion-rock sound.

I admit that I’m sometimes bad at distinguishing which guitar I’m hearing on tape at a given moment, but I’m pretty sure J. J. Jackson deserves the lion’s share of credit for the amazing sound on “Watchtower.”

In an interesting article for Isis, Jörgen Lindström considers the G. E. Smith years as lead guitarist for the NET, and then contrasts them with the J. J. Jackson years that followed. According to Lindström,

I see 1988-1990 as a kind of overture, a testing of the waters after, as he claimed, having felt lost as a stage performer for most of the decade. Dylan had guitarist G. E. Smith to lean on for the first two years—1988 and ’89—and after G. E. left there was a stronger confidence and a foundation to work from. Bob tried to continue in the G. E. vein with new guitar players, but when that didn’t work, he decided to throw it all away. (245)

Lindström believes this is the point when the NET truly began to flourish, and he sees Jackson as a crucial catalyst. In Lindström’s estimation, the new guitarist

was more willing to go along with whatever happened on stage and just to have fun with it. He was also a wonderfully inventive player, whose bluesy solos excited the 1991 audiences when sometimes Bob himself didn’t quite manage to do that. Just as it is extremely difficult to think of the NET overture without G. E., I find it impossible to think of the start of what I call the NET proper without the magnificent ‘J. J.’ Jackson. (247).

If you want to hear an excellent example of Jackson’s guitar prowess, and how his contributions work effectively to raise the level of the ensemble, check out the Music Hall ’92 “Watchtower.”

During the long outro of the song, Dylan gets in on the action by answering Jackson’s guitar with his harmonica, as if they are the musical incarnations of the Joker and the Thief. And the pounding hoofbeats of the two riders approaching are effectively doubled by the two drummers Watson and Wallace pounding away back there on their kits.

The most bizarre element of “Watchtower” doesn’t come through on the bootleg, but it was recorded for posterity in Cliff Radel’s concert review for the Cincinnati Enquirer. According to the local music critic, “You know you’re in for a night of surprises when Bob Dylan moonwalks across the stage. Strange as it sounds, that’s what he did Tuesday night early into his two-hour Election Day concert at Music Hall. To be exact, it wasn’t a true moonwalk. Dylan glided sideways, not backward, during his show’s third song, ‘All Along the Watchtower.’ So call it a Bobwalk” (C-9). Radel is riffing off the recent “Bobfest” celebration in New York, as well as his own feature piece on Dylan published in the previous Sunday paper.

Next up is a remarkable reinvention of “Positively 4th Street.” Dylan originally wrote and recorded the song in a seething rage directed at folk purists who turned against him when he went electric at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival. (Dylan lived on 4th Street in Greenwich Village in the midst of the folk music circuit.) The anger is largely drained out of the song in this 1992 reincarnation. Dylan’s voice sounds gravelly and weary in this delivery: he’s no longer infuriated, just melancholy and disappointed.

I’m especially fascinated by the song’s musical reimagination at Music Hall ’92. The band takes some turns on “Positively 4th Street” that I’ve never heard before in the song. During an extended breakdown on either side of the final verse, it feels like they pull the old car in for a tune-up. I get a visual image of Dylan and the fellas standing around in the garage and popping the hood on this song. They pull wires and jiggle plugs, messing around with the machinery, curious to see what makes it run and testing the limits of its durability.

The fifth song is “I Want You.” The last time Dylan played this spritely tune at Music Hall he was accompanied by Al Kooper, whose organ provided a signature for Dylan’s mid-sixties sound. “I Want You” was no longer a regular part of Dylan’s setlists in 1992; in fact, the only time he played the song in the U.S. that year was at Music Hall.

This is another performance where Baxter’s southern-fried contributions bring out new flavors in the song. Dylan joins the country romp with his harmonica after the final verse, and the band lays back to give him room. Things are rolling along fine at first . . . but then the wheels come off.

Dylan stops playing harmonica at the 5:00 mark, and it sounds like no one is quite sure how to interpret that, or what they’re expected to do in response. Dylan pushes each of them out of the plane, and no one can find the ripcord to his parachute. After noodling around and getting nowhere, they finally just accept defeat, shut it down, and put the song back in storage. Perhaps we can chalk it up to unfamiliarity: this NET lineup had never played the song together live. In any case, they sound lost at the end. Dylan dropped “I Want You” from the fall setlist after this meandering Music Hall miscue. He wouldn’t brush off the mothballs and unpack the song again for another year, at the storied Manhattan Supper Club shows of 1993, with much better results.

Ray Padgett has conducted many excellent interviews with musicians who played with Dylan. A recurring theme in conversations with NET band members is the reward, but also the challenge, of flying by the seat of your pants on stage. It’s spontaneous, it’s intuitive, it can be exhilarating, and it can also be scary. Drummer Winston Watson described it this way:

No one ever said, “Play like this or play like that.” That is a relief, but it’s also terrifying because it’s all up to you to be intuitive. That’s more intimidating than putting staff paper in front of me. Not being a great sight-reader, I can fake my way through a chart, but you can’t fake your way through a vibe. People are like, “How can you memorize all this stuff?” I said, “Easy. You don’t play it like everybody remembers it. Just play it however he wants it today.”

Ah, but what if you can’t figure out how the boss wants it today? Witness the latter part of “I Want You” at Music Hall ’92. When it works, the results can be magical. When it doesn’t, it can feel more like, to quote Watson, “a mindfuck.”

In a conversation with Clinton Heylin, Bucky Baxter describes very similar experiences in playing live with such a volatile bandleader:

He’s in a lot of different moods. He’ll be looking at you like you’re king of the world. Two songs later, he’s shrinking you with his eyes: “You suck so bad.” At the end of a show you almost forget about the good parts, because you’re uptight about the parts he isn’t digging. My friends say, “What’s it like?” And I always say, “It’s not that much fun. But it’s incredibly interesting.” (qtd Heylin 685)

“I Want You” is followed by “I and I.” The band shakes off the last fumble and totally commits to the next play. They sound fantastic!

The guitarists on this song have big shoes to fill after the great Mark Knopfler’s perfect accompaniment on the album Infidels (1983). J. J. Jackson holds his own, and Dylan is no slouch either. His vocal is powerful, too, if a bit on the nasally and gravelly side. But tonight on “I and I,” the musical-I has the upper hand over the lyrical-I. This achievement is all the more notable coming on the heels of a rather shambolic “I Want You.” The band goes straight from a segment where they sound disjointed to one where every musician is dialed into the same frequency, their intuition is perfectly aligned with the frontman, and they play as a cohesive unit. Dylan’s one and only Cincinnati performance of “I and I” is a stone-cold killer.

Acoustic Set

If you are as big a fan of Good as I Been to You as I am, then you will love the acoustic set at Music Hall ’92 because Dylan’s voice and guitar playing sound so similar to his brilliant work on that album. The acoustic sets are always greeted warmly by audiences, but the Cincinnati crowd is noticeably louder than they had been all night during the transition to the acoustic set. I’m guessing that many listeners seated up close by the taper had already purchased their copies of GAIBTY and had been listening to it throughout the day. They are pumped up for acoustic Dylan, and he delivers the goods.

The first acoustic number is “Mama, You Been on My Mind.” This song is especially beloved in Dylan lore for his duets with Joan Baez, first in 1964 and later during the Rolling Thunder Revue in 1975.

Dylan on acoustic guitar and harmonica delivers a tender version at Music Hall ’92, cut from the same sonic cloth as GAIBTY.

I’ve been groping for the right way to describe the effect of Dylan’s solo acoustic performance of “Mama, You Been on My Mind” on this night. I think the best term for it is “ghost duet.” The song is so closely associated in my mind with Dylan’s duets with Baez that I retain a sense of her spectral presence in the song even in her physical absence. Dylan’s piercing performance just makes it too concise and too clear that Joanie’s not here. I can’t help but mentally fill in her missing voice, turning his solo into a ghost duet. It’s all in my head, sure, but that’s equally true for the singer, right? You’ve been on both of our minds.

Music Hall has a longstanding reputation for being haunted. The reputation is so deeply instilled in the community that the Friends of Music Hall regularly lead ghost tours of the building. The TV show Ghost Hunters featured Music Hall in an episode called “Phantoms of the Opera,” which aired on Halloween 2014. I’m not typically into that sort of thing myself. But I will say that “Mama, You Been on My Mind” was the first of multiple instances where this concert feels musically haunted to me. I’m reminded of the line from Dylan’s late friend Robbie Robertson in his song “Somewhere Down the Crazy River”: “Wait, did you hear that? / Oh, this is sure stirring up some ghosts for me.”

The second acoustic song is the beautiful “Boots of Spanish Leather.” What a gift Dylan gives the Music Hall audience this evening. “Boots” is the ninth song on the setlist, and six of them had never played in our fair city before. He delivers another exquisite performance. His playing and singing on “Boots” sound like a blend of “Love Henry” and “Two Soldiers” from World Gone Wrong, the 1993 follow-up to Good as I Been to You.

Although I’m sure Dylan didn’t intend the “ghost duet” effect I describe above for “Mama,” I do think he intends something very like it in “Boots.” The song is written as a series of letters back and forth across the sea from a woman who travels abroad to Europe and a man who stays behind and misses her. There are two letter-writers in the song, but only one singer. The song seems tailor-made for a duet between a man and woman, and indeed there have been some very fine renditions along these lines (my favorite is by Mandolin Orange). But recasting the song as a two-hander loses an important dimension. The woman is gone for good and the man is left behind to brood over her, rereading her letters for the thousandth time, gradually forgetting exactly what she sounded like as his own inner voice comes to displace her unrecoverable voice. She is an absence with a persistent presence in his life, which is what makes the song at heart a “ghost duet.”

In the pause between “Boots” and the next song, a man near the taper (or perhaps the taper himself) yells out “Little Maggie!” A woman nearby throws in, “Diamond Joe!” These are clearly superfans who have already been listening to Good as I Been to You, since both of those tunes appear on the album released earlier that day. The Dylanophiles do not get their wishes, but I guarantee they were happy with what they got instead: “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue.”

Even before he utters a word, Dylan casts a spell with his superb guitar intro. He has played this song so many times since 1965, one may well wonder how he has anything left to give it. But he’s totally locked in tonight, completely present in the song musically and vocally—no ghosting here. It’s absolutely riveting. The yelping audience stops shouting requests and quiets down into reverent silence. They know they’re getting something very special from Dylan and no one dares to break the trance. I had to go back and listen to this one again immediately after first hearing it because I wasn’t ready yet to wake up from the dream. Is this the secret chord that David played to please the Lord? After the lyrics, Dylan lays down some phenomenal guitar, and just when you think you can’t love it any more he pulls out his harmonica and pierces you to the soul. What a thing of sacred beauty. Hallelujah!

When Dylan transfigures before our eyes and ears, becoming a medium for channeling sacred mysteries, it’s not just fans on our side of the footlights or the bootleg who respond with awe. Winnie Watson testifies to having the same reaction to Dylan’s acoustic performances. “When Bob plays acoustic guitar, I think it’s the most beautiful thing someone could hear,” the drummer told Ray. He said as much to Dylan, too:

I told him that one night. I said, “I could sit there and listen to you play all night and not ever get on my drums.” He says, “Do you think a room full of people would sit there and do that?” I said, “Don’t give me that, man. Come on.” I could talk to him like that, which was pretty cool. I was still a fan. I know you’re not supposed to show that, but I couldn’t help it.

Yes, Bob, of course a room full of people would sit there and listen to you play acoustic guitar all night. Please! Like me, I’m sure you love Dylan’s many bands through the years, and all the extra layers of sensory experience that come from interacting with his talented musical collaborators. But when you hear a performance like “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue” at Music Hall ’92, you’re reminded that the man has the skill, the magnetism, the material, and the gravitas to hold an audience completely spellbound all by himself. He got tired of carrying the whole load back in 1965, and he has never looked back. How could we wish it any other way? Nevertheless, when he unplugs his electric guitar and taps back into that latent power source with just his acoustic guitar and harmonica, that little dude expands to stellar proportions and fills the arena with the radiant light of a supergiant star.

The fourth and final number of the acoustic set is another colossal song: “Desolation Row.” There’s a good chance that Dylan played this song in the acoustic set of his November 1965 concert at Music Hall. But since no tape or setlist survives from that show, this is the first record we have of him playing the masterpiece in Cincinnati. This was his only performance of “Desolation Row” during the fall of 1992, so he’s giving the locals a very special treat.

The highlight of this “Desolation Row” is Dylan’s blistering acoustic guitar. The first thing you notice is how fast he’s playing. But it’s more than just speed. He is remarkably freewheeling in his musical explorations. Andy Muir credits GAIBTY with renewing Dylan’s aptitude for acoustic guitar: “Another sharp contrast to the NET was to be found in Dylan’s brilliant guitar playing. The same man that had merely strummed his way through countless acoustic sets was now to be heard dexterously picking the guitar strings and providing effective, understated embellishments” (115). “Desolation Row” certifies that Dylan could still be a virtuoso on the instrument when he put his mind and fingers to it.

There are a couple of extended breaks where Dylan breathes new life into the classic song with guitar parts I’ve never heard before. Or maybe I have. In the long musical interlude before the last verse, I could swear that some of Dylan’s licks sound like The Edge’s iconic guitar intro in U2’s “I Still Haven’t Found What I’m Looking For.”

Unfortunately, I hear very different echoes in Dylan’s vocal for “Desolation Row” at Music Hall ’92, and it has kind of ruined an otherwise compelling performance for me. Mind you, I loved it the first few times I heard it. My initial notes praise Dylan for his distinct phrasing. But when I returned to the bootleg in order to write this piece, “Desolation Row” struck me in a weird way. Dylan’s high nasal whine, particularly in the last verse, began to remind me more and more of . . . Cartman from South Park! Trust me: I wish I could unhear this. But now that it’s stained on my brain, I can’t seem to wash it clean. You can judge for yourself:

Hearing a “ghost duet” between Bob and Joan is all well and good. But it’s maddening to hear a work of genius funneled through my earbuds and refracted through my twisted mind only to come out as “Screw you guys! I’m going home . . . to Desolation Row!” After hearing the similarities, I did what one does and googled it. Sure enough, there are many threads out there comparing Dylan and Cartman’s voices. But I didn’t have the heart to wander any further down that rabbit hole. Ain’t it just like the night to play tricks when you’re trying to be so quiet?

Second Electric Set & Encore

Back with the full band, Dylan opens the second electric set with a surprising selection: “Unbelievable” from the largely overlooked album under the red sky. He first played this song live in August 1992, and he only played it five more times ever after Music Hall. I hadn’t listened to this deep cut in many years before encountering it in the bootleg. Musically, this performance sounds like a rockabilly rough draft of “Summer Days.” Following on the heels of an astonishing acoustic set, “Unbelievable” strikes me as good fun but nothing extraordinary.

It’s interesting to find a different perspective from Jake Fredel. He has spent more time with the 1992 bootlegs than anyone else, and he shared some of his impressions in “The Best and Worst Dylan Shows of 1992—By Someone Who’s Listened to Every Single One,” a guest piece on Flagging Down the Double E’s. Fredel ranks Cincinnati #5 on his list of Dylan’s best concerts in 1992, explaining, “Here’s another great one! I’ve never heard anything about this show, but it’s one of those hidden gems you always hope to stumble upon. Bob is engaged, the band is tight, there are some well-performed rarities, and the sound quality of the recording is very good.” He elaborates upon the relative strengths at Music Hall:

The acoustic set is not quite top tier for this tour, but it’s hard to beat the song selection. Solo acoustic “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue” and “Desolation Row” with Tony accompanying on standup bass. But what is top tier is the version of “Unbelievable” that follows. Just when I was getting sick of this song, Bob and crew blew me away with what might be the best version yet. Really cool rockabilly breakdown at the end.

I share Fredel’s high regard for Music Hall ’92, but we experience different peaks and valleys. He finds the acoustic set good and “Unbelievable” great; I would reverse those adjectives. I respond with almost religious ecstasy at times to the acoustic set—I believe in you! I believe less fervently in “Unbelievable.” It’s an entertaining number, no sin in that. Dylan and the boys play the hell out of “Unbelievable,” but I wouldn’t call it heaven-sent like the acoustic performances that precede it.

Dylan continues to burnish this golden setlist by following “Unbelievable” with his most poignant hymn of belief in the face of temptation and self-doubt: “Every Grain of Sand.” This is one of the finest songs Dylan ever wrote. It was originally released as the closing track on his final Christian album, Shot of Love (1981). It always feels like cause for celebration when Dylan sings this achingly beautiful song about spiritual crisis, and it has never been more powerful than as the closer during The Rough and Rowdy Ways Tour.

The Music Hall ’92 “Every Grain of Sand” is quite different than either the 1981 album version or the RARW finale. I wouldn’t want to call this version “worse,” since I would never denigrate a work of such magnificence and grace as “Every Grain of Sand.” I will admit, however, that I miss Dylan’s piano and harmonica from other memorable performances. There’s the ghost thing again: the song is haunted by other incarnations that come before and after.

Dylan and his bandmates play an extended interlude before the last verse where they seem to be searching for something musically, knocking on doors that never open. Salute them for their effort. Not every musical experiment can work. If it were easy and obvious how to break on through to the other side, then every concert would be like skipping through a field of poppies in the land of permanent bliss. Instead, you grope through a hallway with a busted bulb, fumbling for the right key in the darkness. Sooner or later, one might open the portal to nirvana.

Dylan delivers a strong, if idiosyncratic, vocal in this “Every Grain of Sand.” As with multiple Music Hall ’92 songs, he falls into a pattern of laying emphasis on the final word of each line, increasing his pitch and volume. If he were doing this to stress a point, lyrically or emotionally, it could be an effective technique. But once it becomes habitual, it sounds like a verbal tic or affectation. (By the way, I partially blame this technique for the Cartman effect in “Desolation Row.”) He slips into that pattern in the early verses of “Every Grain of Sand.”

Even if Dylan never approaches the vaulted ceiling of this cathedral of a song at Music Hall, the floor is extremely high. In truth I’ve never heard a version of “Every Grain of Sand” that didn’t feel like a blessing. Dylan’s vocal is so passionate in the final verse that any doubt from this listener is dispelled and I’m converted into a true believer once again.

Dylan revives two favorites from the sixties to close out the second electric set. The audience responds warmly to “The Times They Are A-Changin’.”

Musically and vocally this new version sounds less like the album version and more like something off GAIBTY such as “Arthur McBride” or “Diamond Joe.” Once again, Dylan experiments with vocal modulations in his delivery on “Times.” Sometimes it’s effective, sometimes distracting, at least to me. But the Music Hall audience gobbles the whole hog down hungrily and clamors for more.

They get what they ask for with “Maggie’s Farm.” I’ve never heard the song sound quite like this before.

I didn’t like it much at first and thought it fell flat. But then the interplay of guitars and percussion starts to win me over, picking up speed and chugging like a freight train from the middle of the song through to its conclusion. This arrangement brings the song back home to its rural setting (it takes place on a Southern plantation). The more I listen, the more I think that the guitars and percussions really are going for this train effect, accelerating for straight stretches, then slowing down around the bends, before building up another head of steam and hauling ass down the track. By the end, I’ve hitched a ride and am totally on board.

Dylan plays three songs in the encore: “Shooting Star,” “Everything Is Broken,” and “It Ain’t Me, Babe.” The latter two are strong, but “Shooting Star” outshines them so brilliantly that I’ll just focus on that one.

First, I should point out an oddity on the bootleg. While the audience is cheering for the band to come back out for an encore, we almost hear a fight break out. Someone very close to the taper threatens, “Leave it alone, fucking asshole!” Is it the taper himself? Was someone messing with his equipment? Maybe Gene Hackman from The Conversation could solve the mystery, but I cannot. Afterwards, as the band starts playing but before Dylan starts singing, a couple of excited fans start yelling “Oh Sister! Oh Sister!” Well, it’s not “Oh, Sister” but rather “Shooting Star.” To be fair, the song’s respective openings sound more similar than I had ever noticed before. There’s the ghost of Joan Baez making her presence felt once again. But the song summons other ghosts, too.

I’ve always been deeply moved by “Shooting Star,” the closing track on Oh Mercy. The album hadn’t been released yet when Dylan played Riverbend ’89, so this is the first Oh Mercy song he ever played in Cincinnati. I hear the first and last verse as a response to Richard Manuel’s suicide in 1986, and perhaps John Lennon’s 1980 murder as well (the literal shooting of a star), alongside Dylan’s commentary on himself as a shooting star in the second verse.

His vocal delivery really floors me. The third verse gathers intensity, then he delivers the final verse drenched in sadness. The music after this final verse—or what is usually the final verse—effectively complements the mood, especially Baxter’s mournful steel guitar.

Then Dylan does something jaw-droppingly wondrous. Anyone who knows the song from Oh Mercy assumes that he’s done singing and is riding the wave of the outro back to shore. But instead he goes back and repeats the third and fourth verses. They were so good the first time, why not try them a second time with even more emotion? So that’s exactly what he does.

He wrings every ounce of yearning out of the third verse, and then yells, pleads, shakes his fist at the sky on that final verse—"Tomorrow gonna be another DAY! / It’s too late to say to you the things / That you needed to HEAR ME SAY!!” These are tears of rage and tears of grief, to quote the song co-written by Dylan and Manuel. Finally, he closes in diminuendo with tears of impotence: “Seen a shooting star tonight / Slip away.”

This isn’t a shooting star, it’s an entire meteor shower of emotion which I did not see coming at all but which illuminates the auditorium like the explosion from a dying star. The singer is consumed with regret for not getting a last chance to express what he needed to say to the lost “you” of the song. Hear that “you” as the ghost murmuring in your own ear as you listen. By repeating those last verses, he tries again, and fails again, to make a connection. Too late. The futility of the gesture would be utterly devastating were it not for the beautiful song that Dylan creates out of the pain, a work of art that lives on after the star has flamed out into darkness. I see my light come shining through this haunting and haunted performance.

Oh mercy! Dylan’s supernova “Shooting Star” is not only the highlight of the entire concert, but it’s also one of my favorite moments from his entire performance career in Cincinnati. Let that glorious blaze across the firmament serve as epilogue for Music Hall ’92 and as prologue for future greatness to come. For the next installment (for real this time) we will turn our attention to the first and best Dylan concert I ever attended in Cincinnati: the legendary show at Bogart’s in 1999. See you there!

Works Cited

Clinton, Bill. “Remarks by the President at Kennedy Center Honors Reception.” White House Archives (7 December 1997), https://clintonwhitehouse4.archives.gov/WH/New/html/19971208-2814.html.

Dylan, Bob. Official Song Lyrics. The Official Bob Dylan Website,

http://www.bobdylan.com/

.

Fredel, Jake. “The Best and Worst Dylan Shows of 1992—By Someone Who’s Listened to Every Single One.” Flagging Down the Double E’s (15 November 2022),

.

Heylin, Clinton. Bob Dylan: Behind the Shades Revisited. William Morrow, 2001.

LB-04998. Bootleg Recording. Taper unknown. Music Hall, Cincinnati (3 November 1992).

Lindström, Jörgen. “New Morning: On the Threshold of a New Game.” Bob Dylan Anthology, Volume 3: Celebrating 200 Editions of Isis Magazine, ed. Derek Barker (Red Planet, 2019), 245-57.

Muir, Andrew. One More Night: Bob Dylan’s Never Ending Tour. CreateSpace, 2013.

Padgett, Ray. “Winston Watson Talks Drumming for Bob Dylan in the ’90s.” Flagging Down the Double E’s (4 August 2022),

.

Radel, Cliff. “Dylan enunciates passion in concert.” Cincinnati Enquirer (5 November 1992): C-9.

Robertson, Robbie. “Somewhere Down the Crazy River.” Robbie Robertson. Geffen, 1987.

In the late 00s message board posters dubbed his low growl The Wolfman. Had the show been around in 92, that would have slotted in nicely next to The Cartman.