You’d think that Willie Nelson had his hands full with organizing and headlining the Outlaw Music Festival. But on September 11, 2024, at Cincinnati’s Riverbend Music Center, he also delivered the best review I’ve heard yet of Bob Dylan’s concerts on this tour. Wedged between the crowd-pleasing sets of John Mellencamp and Willie Nelson, Dylan’s idiosyncratic performance was met mostly with indifference by the restless crowd. The Outlaw-in-Chief may have thought he was singing about cowboys, but to my ears these lines from the Waylon & Willie classic fit Dylan like a glove (or a noose):

Them that don’t know him won’t like him

And them that do sometimes don’t know how to take him

He ain’t wrong, he’s just different

But his pride won’t let him

Do things to make you think he’s right

Mammas don’t let your babies grow up to be Bob Dylan!

A reviewer going by E.B. on Bob Links provides this field report, accurately capturing the general malaise of this Willie-centric audience in response to the eccentric Bob set:

If the folks could stop their non-stop nattering, but, no, it was a talkative crowd. I was close enough to give my attention to the songs and appreciated Bob’s careful, forceful, committed performance. But the man next to me kept saying, “C’mon, Bob!” in his annoyed voice, expecting the hit parade he didn’t get. He sat down and stared at his phone after a while. I caught a quick glance: he was googling “Bob Dylan.” I wondered if he found him?

I agree with E.B.’s conclusion: “These outdoor Pavilion crowds are a certain type that want to hear the hits. Can’t blame them, but that’s not happening, and I got the feeling that everyone was marking time until Willie came on. Such a shame, because something was happening here, but they didn’t know what it was.”

Don’t get me wrong: I’m no buzzkill. Normally, I’m one of those summer concertgoers out for a good time. When Mellencamp was encouraging the audience to belt out the chorus of “Jack & Diane,” I was headbanging along with all the other hooligans. “Oh, yeah, life goes on long after the thrill of living is gone.” It can be thrilling to temporarily revisit your youth, seeing your favorite performers from days of yore, jamming out to those old beloved anthems, shouting and shimmying and hoping your knees and hip don’t give out in front of all these fine folks. “Whiskey River take my mind!” Take mine too, Willie!

Most big-time musicians cater to this harmless appetite for nostalgic fun. That’s the job, isn’t it? Entertain the ticket-buying public. The other three acts on the bill certainly believed so and orchestrated their concerts accordingly. But that isn’t Dylan’s approach. He ain’t wrong, he’s just different. Call it pride, call it integrity, call it contrarianism, whatever you like. He refuses to conform to conventional expectations by playing the hits and getting the fans involved, at least not in the same gregarious ways that the consummate showmen Mellencamp and Nelson do it.

Particularly in recent years, Dylan concerts have become profound experiences. We’re witnessing the glorious sunset of a major artist, and it fills fans with gratitude and awe. The congregation gathers to revere this larger-than-life figure who has meant so much to us personally and to the culture. Dylan feeds a different appetite than most popular musicians. Everything about the Rough and Rowdy Ways Tour—from the song selections and performances to the venue choices and phone policies—were deliberately designed to facilitate devout pilgrims in their quest toward musical nirvana.

It was impossible to faithfully reproduce those conditions and cultivate those experiences in the context of the Outlaw Musical Festival. Looking for a sprawling outdoor concert for swaying in the summer heat to golden oldies? Sounds fun, count me in. Want a profound communion with a singular talent at the top of his powers in the twilight of his career? Yes please, I wouldn’t dare miss it. Usually these two choices are mutually exclusive and discretely compartmentalized: choose your own adventure. At Riverbend ’24, however, one experience was grafted onto the other, and it made for a disjointed evening.

The live dimension of Dylan’s concerts is always important, but this is one where I didn’t fully appreciate the strength of his performance until I re-experienced it by bootleg in the privacy of my home. With the benefit of hindsight and tranquility, I now recognize Riverbend ’24 as a significant achievement and a worthy final installment of the Dylan in Cincinnati series.

When: September 11, 2024

Where: Riverbend Music Center in Anderson Township

Openers: Southern Avenue and John Mellencamp

Headliner: Willie Nelson & Family

Band: Bob Dylan (vocals, piano, and harmonica); Bob Britt (acoustic and electric guitar); Tony Garnier (electric and stand-up bass); Jim Keltner (drums); Doug Lancio (acoustic and electric guitar); Mickey Raphael (harmonica)

Setlist:

1. “Rainy Day Women #12 & 35”

2. “Shooting Star”

3. “Love Sick”

4. “Little Queenie”

5. “Mr. Blue”

6. “Early Roman Kings”

7. “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall”

8. “Under the Red Sky”

9. “Things Have Changed”

10. “Stella Blue”

11. “Six Days on the Road”

12. “Can’t Wait”

13. “I’ll Be Your Baby Tonight”

14. “Soon After Midnight”

15. “Simple Twist of Fate”

16. “Ballad of a Thin Man”

One of the things I’ve come to cherish most about Riverbend ’24 is how persistently Dylan emphasizes the theme of returning home. It comes through on several levels. There is his reunion with musical brothers, sharing a bill with Mellencamp and Nelson, and making music once again with longtime collaborator Jim Keltner. He also reiterates the homecoming theme by returning to his musical roots in 1950s Minnesota, performing songs and celebrating singers that first inspired his odyssey.

Dylan embodies the ravages of time while simultaneously transcending time through song, merging the past with the present and conjuring the dead back to life. In this final installment, I want to marvel at how he accomplishes this feat in select songs from Riverbend ’24. The two major performances are “Hard Rain” and “Stella Blue,” so I’ll use those as bookends. I’m also interested in “Under the Red Sky” and “Shooting Star,” songs last played live in 2013 before being resurrected for the Outlaw tour. Additionally, Dylan channels his teen years at Riverbend ’24, most notably through his covers of “Little Queenie” and “Mr. Blue.”

One of the most familiar examples of the homecoming theme in Dylan is the chorus of “Like a Rolling Stone”:

How does it feel

How does it feel

To be on your own

With no direction home

Like a complete unknown

Like a rolling stone?

Dylan didn’t play his most famous rock song at Riverbend ’24, and in truth it would’ve been incompatible with this setlist. The Outlaw concert sends a starkly different message: there is a direction home, and Dylan has not been on his own. As Court Carney observes in “Wanted Men: Bob Dylan and the Vulnerability of Brotherhood” (forthcoming in the next issue of The Dylan Review), Dylan has learned from wise mentors and leaned on loving brothers throughout his life and career. He has companions for the journey home.

At Riverbend ’24, Dylan and the band walk out on stage to the finale of Rossini’s William Tell Overture. No one from Dylan’s generation can hear this music without immediately associating it with The Lone Ranger television show (1949-1957).

“Return with us now to those thrilling days of yesteryear. The Lone Ranger rides again!” But here’s the thing: The Lone Ranger was not alone. He rode on his trusty steed Silver and he depended on his faithful friend Tonto. Likewise, Dylan is backed by his posse on stage, as well as an entire behind-the-scenes support staff making his Lone Ranger mystique possible. During the 2024 Outlaw Music Festival, he seems intent upon acknowledging the importance of companionship and brotherhood to his songs, values, and legacy.

“A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall” & “Under the Red Sky”

Dylan presents “Hard Rain” as a dirge at Riverbend ’24. The primary focus is on Dylan’s voice. His delivery is as slow and somber as I’ve ever heard it.

The parent asks the child, “What’ll you do now, my blue-eyed son? / What’ll you do now, my darling young one?” He answers, “I’m going back out ’fore the rain starts to fallin’.” That exchange comes across very differently in 1962 than in 2024. In its original incarnation, “Hard Rain” was charged with both prophecy and defiance, as if to say, “I see the ills that beset my world. I foresee worse problems if we stand by idly and do nothing. I’m going out to sound the alarm and support the revolution.”

And now? The darling young one is a wizened old man. The prophet’s voice has grown hoarse from decades of unheeded warning. The rain has kept falling steadily until the flood waters are up to his chin. He can’t yell anymore; he can hardly even speak. But he’ll keep delivering his message until his final breath—which sounds like it could come any minute.

I’ve loved “Hard Rain” from the moment I first heard it as a teenager. But I’ll confess that there’s one element that never entirely sat right with me: “And it’s hard, and it’s a hard, and it’s a hard, and it’s a hard / And it’s a hard rain’s a-gonna fall.” Dude, just say it once and be done with it! At Riverbend ’24, however, Dylan rescues the refrain for me. He’s not excessively piling on unnecessary repetition to stretch the sentiment past its saturation point. In this performance, he stresses every single utterance of the word “hard.” He makes me hear how truly HARD those hard times were. The 83-year-old singer invests each iteration with the heavy weight of lived experience. The 21-year-old singer-songwriter hypothesized the storm to come. The man on stage is more like Lear on the heath: he has weathered the storm.

“Talk” is the right word for it. Dylan recites “Hard Rain” rather than singing it. This performance could have taken place at City Lights Bookstore just as well as Riverbend Music Center. It reminds me of those Beat readings by Kerouac with jazz accompaniment, or Dylan’s recording of his Nobel Lecture with piano support. His slow reading is punctuated with pauses, for emphasis and for breath. He has never sounded more like “a column of air,” to use that beautiful description of Dylan’s voice by Allen Ginsberg in No Direction Home.

The musical embellishments by the band during those pauses are fascinating. It sounds like the narrator is followed by a bedraggled cortege on their ten-thousandth mile in the mouth of a graveyard. I’m especially captivated by Jim Keltner’s interjections. He is the thunder. He is the stones in the road. Dylan vocally sounds the warning, and Keltner redoubles it with his drum, like Kattrin in Mother Courage and Her Children.

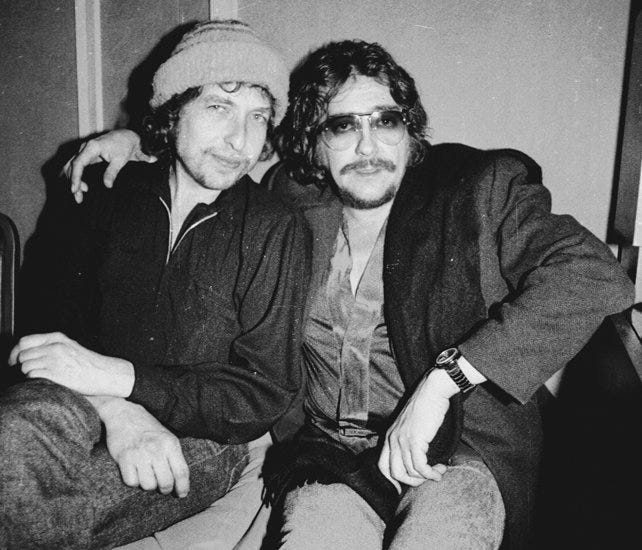

No drummer has a longer history with Dylan than Keltner. Ray Padgett hits the highlights of their 50+ year collaboration in his interview for Flagging Down the Double E’s:

They first met at a 1971 session where Keltner’s Leon Russell-led rhythm section backed Bob on “Watching the River Flow” and “When I Paint My Masterpiece.” […] Keltner played drums for all three of Dylan’s “gospel years.” He played on a wide array of albums—Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid, Saved, Shot of Love, Empire Burlesque, Time Out of Mind—and assorted tracks in between. He became Bob’s go-to drummer for strange one-offs, from the Letterman 10th anniversary special to Japan’s Great Music Experience event where Bob played with a giant orchestra to, of course, the who’s-who of stars at Dylan’s 30th Anniversary Concert Celebration (aka Bobfest). Oh, and did I mention Jim was the sixth Traveling Wilbury? George Harrison even asked him to become an official member and Jim said no (but he still got his own Wilbury moniker: Buster Sidebury).

Keltner has even backed Dylan in Cincinnati before, at Music Hall on November 4 & 5, 1981. He told Ray how much he admired Dylan’s fearless search for “the vibe”:

The thing that I love about Bob is his fearlessness. There’s a fearlessness from some artists that translates to the musicians playing. When that happens, you get the best from the musicians, because the musicians are not worried about tempo or about whether they’re rushing or they’re dragging or whether they’re not in the pocket. It’s not about finding a pocket. It’s more about searching for the vibe, searching for the thing that makes the song have life. I love being able to find a pocket and sit in, but I also love the exploratory thing where you’re letting the song bump you along instead of you bumping the song. It’s a great thing that doesn't happen often enough.

You can hear Keltner and the band being bumped by “Hard Rain,” following the song down improvised routes without a map.

Listening back to the bootleg of Riverbend ’24, I find the musical embellishments visually evocative. They give me a vision of the earth coming back to life after an age of destruction. The words foretell apocalypse, but the music communicates something more hopeful, looking through and beyond the devastation toward a second creation.

I belatedly realize the source of these mental images. The Riverbend ’24 “Hard Rain” dislodged deep memories of a poem I hadn’t thought about since junior high: Sara Teasdale’s “There Will Come Soft Rains.” It was written in 1918, in the wake of World War I and in the midst of a lethal flu pandemic. My 7th grade English teacher Mrs. Roberts introduced it to us in the midst of the Cold War, and it spoke to our shared dread of nuclear holocaust. I wonder if Bobby Zimmerman learned the poem in a similar context back in Hibbing.

Maybe Teasdale’s “Soft Rains” has always been shadowing Dylan’s “Hard Rain” and I never chased it down until now. The poet imagines a day in the distant future, after humanity has destroyed itself, when nature will once again thrive in our absence:

There will come soft rains and the smell of the ground,

And swallows circling with their shimmering sound;

And frogs in the pools singing at night,

And wild plum-trees in tremulous white;

Robins will wear their feathery fire

Whistling their whims on a low-fence wire;

And not one will know of the war, not one

Will care at last when it is done.

Not one would mind, neither bird nor tree

If mankind perished utterly;

And Spring herself, when she woke at dawn,

Would scarcely know that we were gone.

That’s exactly what I visualize as I listen to the Riverbend ’24 “Hard Rain.” Dylan’s voice communicates the hard rain of destruction, but the band summons the soft rains of rejuvenation.

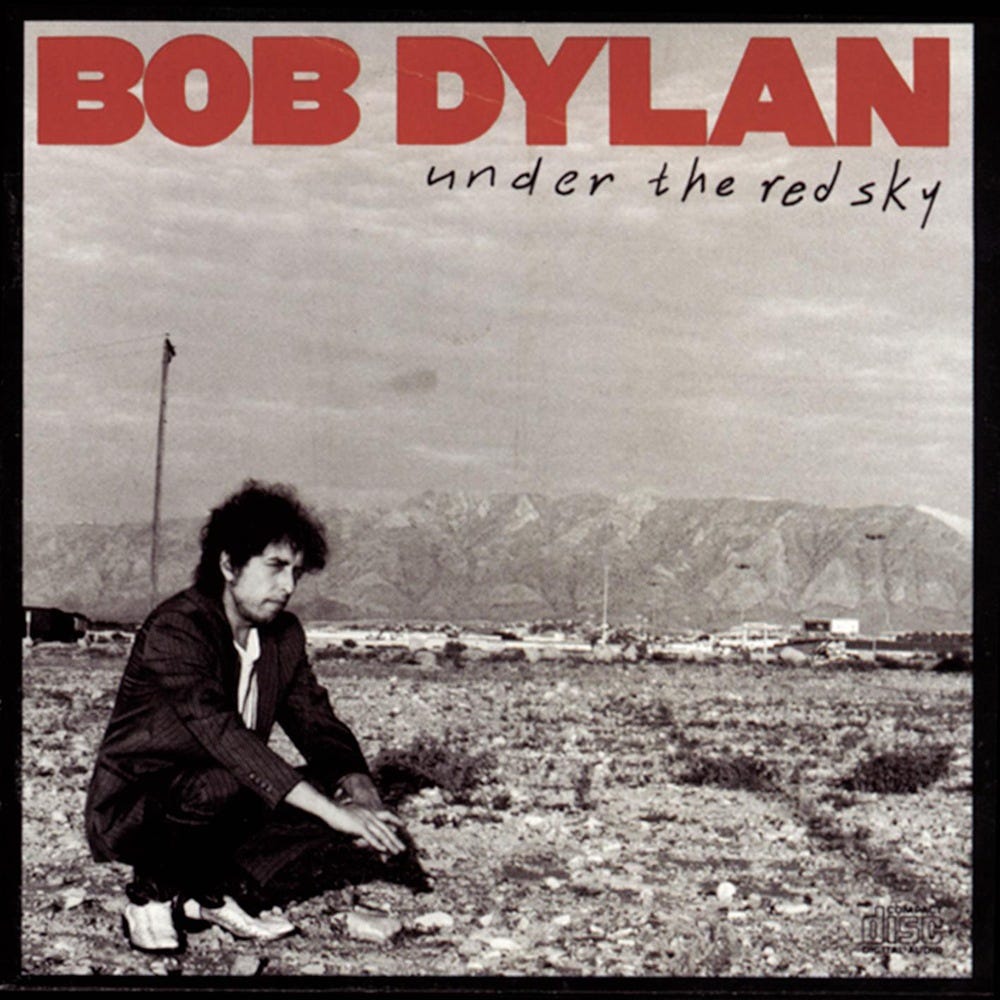

Dylan keeps our attention pointed skyward with the next song in the setlist, “Under the Red Sky.” It’s an inspired pairing with “Hard Rain.”

Lyrically and musically, the two songs are studies in contrast. As many commentators have noted, Dylan draws heavily upon nursery rhymes for his 1990 album under the red sky. “There was a little boy and there was a little girl / And they lived in an alley under the red sky.” The kids are visited by the big daddy from the sky: “There was an old man and he lived in the moon / One summer’s day he came passing by.” “Under the Red Sky” does not end happily ever after. The boy and girl are baked in a pie, and the man in the moon abandons the wasteland.

As Dylan was playing this song at Riverbend, I had a very meta moment where it felt like I had entered the song. The sky father was winking at me with a half moon rising over the Ohio River above the giant projection screen.

Although “Hard Rain” and “Under the Red Sky” are written in very different modes, there is an apocalyptic bent to both. As Michael Gray points out, Dylan’s title imagery mirrors this warning from Jesus:

When it is evening, ye say, it will be fair weather: for the sky is red. And in the morning, it will be foul weather today: for the sky is red and lowring. O ye hypocrites, ye can discern the face of the sky; but can ye not discern the signs of the times? A wicked and adulterous generation seeketh after a sign; and there shall no sign be given unto it, but the sign of the prophet Jonas. (Matthew 16:2-4)

Keep your eyes wide for red skies, but also remember that, according to both scriptures and Dylan, death is not the end. Noah survived the flood, and Jesus was resurrected after crucifixion. Hard rains are followed by soft rains, and red skies are followed by blue skies.

I mentioned that there are several moments from Riverbend ’24 where Dylan seems transported back to his youth in the 1950s. Don Was, the co-producer on under the red sky, told Telegraph interviewer Reid Koppel that Dylan had Hibbing in mind when he wrote the title song: “It’s actually about people who got trapped in his hometown. I think it’s about Hibbing and about people who never left. […] He said, ‘It’s about my hometown’” (qtd. Gray 692-93).

After the subdued pace of “Hard Rain” at Riverbend ’24, “Under the Red Sky” sounds like a jitterbug by comparison. Keltner’s drumming really stands out again. It’s no wonder that he’s been in such high demand for decades. The guitars, piano, and harmonica all hitch their vibe to what Keltner is mixing up back there on the kit. Dylan has gone through several drummers since George Receli left, searching for something he felt was missing. He found it on the Outlaw tour with one of his oldest collaborators and musical brothers. Dylan is the engineer, but Keltner is the one laying down the tracks, and his drumming is sturdy as Mesabi Range steel.

Fifties Flashbacks

In the penultimate song at Riverbend ’24, Dylan performed “Simple Twist of Fate.” Because it first appeared on Blood on the Tracks, listeners tend to associate it with Bob’s split from his wife Sara. “I still believe she was my twin, but I lost the ring.” But Clinton Heylin makes a convincing case for Suze Rotolo as a more likely inspiration. In Dylan’s lyrics notebook from the period, “Simple Twist of Fate” is subtitled “4th Street Affair.” Bob and Suze’s apartment was at 161 West 4th Street in Greenwich Village. If you’re into autobiographical readings, the song seems to recount an affair he had while she was abroad in Europe. Heylin cinches his argument by quoting a performance of “Simple Twist of Fate” from June 30, 1981, when Dylan sang, “I remember Suze and the way that she talked” (Heylin 37).

Another Suze signifier is this revised line, which wasn’t in the original but which Dylan has been singing for years: “She should have met me back ’58, she would’ve stayed with me / Instead sailing off to sea, and leaving me to meditate / Meditate on that simple twist of fate.”

In her memoir, Suze stresses how immature both she and Bob were during their romance:

Bob was my first significant relationship. I was seventeen when we met and, despite having had to grow up very quickly, I still had more growing up to do. Bob was just twenty, and precocious as he was he still had much to learn about life. During our time together things became very complicated because so much happened to him so fast. We had a good time, but also a hard time, as a young couple in love. (226)

When Dylan wishes that Suze had met him back in 1958, he doesn’t mean when she was 14, he means when he was 17. In other words, he wishes they had been the same age, and he wishes she had met Bobby Zimmerman instead of Bob Dylan. Their relationship might have stood a better chance in the fifties than it did in the sixties.

The late fifties are very much on Dylan’s mind during the Outlaw Music Festival. The fourth song in the set is a cover of Chuck Berry’s “Little Queenie.” One wonders if Dylan had Rotolo in mind again with this selection: “There she is again standin’ over by the record machine / Lookin’ like a model on the cover of a magazine / She’s too cute to be a minute over seventeen.” Won’t you come see me, Queen Suze?

“Little Queenie” showcases Bob Britt and Doug Lancio on electric guitars, reminding me of that cool line from Bob Seger’s “Rock and Roll Never Forgets”: “All of Chuck’s children are out there playin’ his licks.”

Dylan’s enthusiasm is obvious on vocals and piano, even if he can’t hold a candle to Berry’s 1959 original. For that matter, I prefer The Rolling Stones’ 1969 live cover and Seger & the Silver Bullet Band’s 1975 live cover to Dylan’s Riverbend ’24 version. But that’s not a musical critique so much as a fantasy of perpetual youth. I wish I could turn back time and meet Bobby back in the late fifties, when the song was new, his vocal chords were elastic, and his golden future still lay before him.

Dylan pairs “Little Queenie” with another fifties cover, “Mr. Blue,” a hit for The Fleetwoods in 1959. As far as we know, he never played the song in concert before the Outlaw tour. But he did perform it with his basement brothers in 1967. I have long considered “Mr. Blue” one of the highlights of the Basement Tapes, so I was elated to finally hear him sing it live at Riverbend ’24.

1959 was a pivotal year for Bobby Zimmerman’s transfiguration into Bob Dylan. On January 31, 1959, he saw Buddy Holly in concert, only a few days before the 22-year-old Texan died in a fatal plane crash. In his Nobel Lecture, Dylan claims that he had a mystical experience at the Duluth concert: “Then, out of the blue, the most uncanny thing happened. He looked me right straight dead in the eye, and he transmitted something. Something I didn’t know what. And it gave me the chills. I think it was a day or two after that that his plane went down.” Dylan implies that Holly anointed him as his successor and passed down his musical spirit before meeting his doom on February 2, 1959. Dylan describes Holly as his musical brother:

From the moment I first heard him, I felt akin. I felt related, like he was an older brother. I even thought I resembled him. Buddy played the music that I loved – the music I grew up on: country western, rock ‘n’ roll, and rhythm and blues. Three separate strands of music that he intertwined and infused into one genre. One brand. And Buddy wrote songs – songs that had beautiful melodies and imaginative verses. And he sang great – sang in more than a few voices. He was the archetype. Everything I wasn’t and wanted to be.

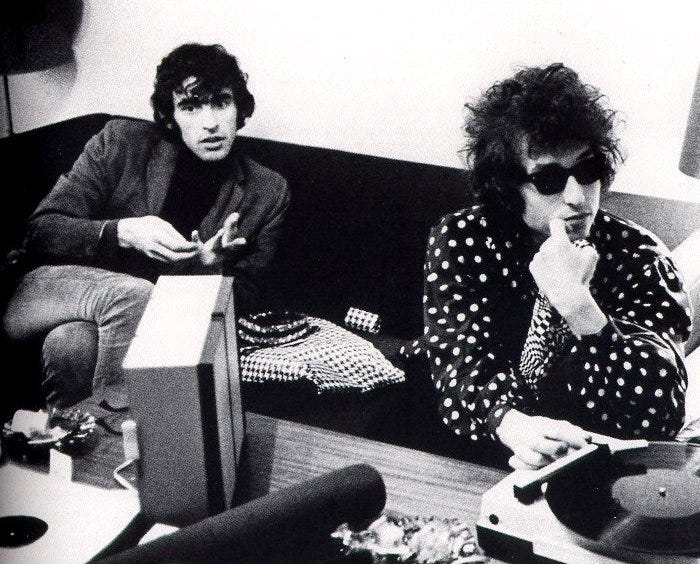

Dylan met another important musical brother in 1959. Robert Velline was 15 years-old when his idol Buddy Holly died. The Winter Dance Party tour was scheduled for Moorhead, Minnesota, on February 3, the night after “the day the music died.” The promoter scrambled for local substitutes to fill out the decimated lineup. The ambitious high-school sophomore quickly assembled his pals and volunteered for the gig. Asked by the emcee how they should be introduced, the singer made up a band name on the spot: Bobby Vee & The Shadows.

Later that summer, The Shadows decided to experiment by adding a piano player. In an interview for his fan site, Bobby Vee recalls how Bobby Z joined the band:

While The Shadows were on the road the summer of ’59, we talked about how cool it would be to have a piano in the band like Little Richard or Scotty What’s-His-Name, with Gene Vincent. Not any old piano player but someone who could put it down like Jerry Lee. But hey, the ’50s was about Fender guitars, not pianos! We couldn’t find a rock ’n’ roll piano player anywhere. Then one day my brother Bill came home and said he was talking with a guy at Sam’s Recordland who claimed he played piano and had just come off of a tour with Conway Twitty. Bill made arrangements to audition him at the KFGO studio and said he was a funny little wiry kind of guy and he rocked pretty good. Wow! This must be the guy! He told Bill his name was “Elston Gunnn” (with 3 n’s). Kind of weird but let’s try him out. By now, we were making enough money to buy him a matching shirt and with that he was in The Shadows.

Even as an 18-year-old, our young hero was committed to improvisation. I love Vee’s story about their first show:

His first dance with us was in Gwinner, North Dakota. All I remember is an old crusty piano that hadn’t been tuned ever! In the middle of “Lotta Lovin’” I heard the piano from hell go silent. The next thing I heard was the Gene Vincent handclaps, bap bap…bap…BAP BAP…BAP and heavy breathing next to my ear. I looked over to find Elston Gunnn dancing next to me as he broke into a background vocal part. Obviously, he had also come to the conclusion that the piano wasn’t working out.

They soon parted ways amicably, with Bobby Z heading off to the University of Minnesota and Bobby Vee putting together a string of hits, emerging as a teen idol in the early sixties.

Knowing that Dylan sometimes sang backup with The Shadows, I really wish we knew their setlists. When Steve Seel interviewed Vee at the 2007 symposium “Highway 61 Revisited: Dylan’s Road from Minnesota to the World,” he asked what songs Dylan played. Vee’s answer was vague: “He knew all the songs that we knew. We grew up listening to the same radio stations and the same songs. So he knew the tunes. And he sang along with them and played along as best as he could.” Perhaps we can look for clues from Bobby Vee’s first album, Bobby Vee Sings Your Favorites (1960). Take a listen and one track leaps out—“Mr. Blue”!

Our grizzled veteran had never played “Mr. Blue” in concert as Bob Dylan until 2024; but it’s fascinating to speculate that Elston Gunnn may have performed it 65 years earlier with The Shadows.

The synchronicities don’t end there. Bobby Vee felt a lifelong debt to Buddy Holly, whose untimely death opened a spot for his own debut and subsequent popularity. In the early sixties Vee released an album of Holly covers called I Remember Buddy Holly. He also teamed up with Holly’s old band on another album called Bobby Vee Meets The Crickets. The latter record consisted of several rockabilly favorites, including . . . “Little Queenie”!

Though Dylan’s direct collaboration with Vee was limited to a couple gigs in 1959, the experience cast a long shadow over both of their lives. Dylan devotes a section of Chronicles to his former bandmate. He recalls,

Bobby Vee and me had a lot in common, even though our paths would take such different directions. We had the same musical history and came from the same place at the same point of time. He had gotten out of the Midwest, too, and had made it to Hollywood. Bobby had a metallic, edgy tone to his voice and it was a musical as a silver bell, like Buddy Holly’s, only deeper. (80)

Dylan remembers attending Vee’s concert in Brooklyn in 1961 and graciously being invited backstage. The gesture meant a lot at the time, since Vee was a rising star and Dylan was still “a complete unknown.” It cemented their bond as musical brothers:

Standing there with Bobby, I didn’t want to act selfishly on his time so we said good-bye and I walked down the side of the theater and out through one of the side doors. There were throngs of young girls waiting for him in the cold outside the building. I cut back out through them into the press of cabs and private cars plowing slowly through the icy streets and headed back to the subway station. I wouldn’t see Bobby Vee again for another thirty years, and though things would be a lot different, I’d always thought of him as a brother. Every time I’d see his name somewhere, it was like he was in the room. (81)

Dylan returned the favor in 1990, inviting Vee backstage for a reunion before his show in Fargo. Most moving of all, when Vee attended his 2013 concert in St. Paul, Dylan covered his old friend’s first hit, “Suzie Baby,” prefacing it with this touching tribute:

Thank you everyone, thank you friends. I lived here a while back, and since that time, I’ve played all over the world, with all kinds of people. And everybody from Mick Jagger to Madonna. And everybody in there in between. I’ve been on the stage with most of those people. But the most beautiful person I’ve ever been on the stage with, was a man who is here tonight, who used to sing a song called “Suzie Baby.” I want to say that Bobby Vee is actually here tonight. Maybe you can show your appreciation with just a round of applause. So we’re gonna try to do this song, like I’ve done it with him before once or twice.

In 2011, Bobby Vee was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s Disease. He got together with his family that year and recorded his final album, The Adobe Sessions. Released in 2014, it includes his only cover (to my knowledge) of a Dylan song, “The Man in Me.”

When Dylan first sang “The Man in Me” on New Morning (1970), it was unmistakably a love letter to his wife Sara, thanking her for bringing out the best in him. But I can’t listen to Vee’s cover without thinking about his Alzheimer’s, a disease that was already eroding his faculties when Dylan serenaded him with “Suzie Baby.” With hundreds of songs to choose from, Vee’s selection seems significant and poignant: a song about a hidden self, “the man in me,” someone trapped inside and inaccessible to everyone but the singer’s intimate partner.

Play the video to the end and you’ll see that it’s signed “Thank You Elston.” Vee was gradually forgetting everything, but he still remembered his former Shadow and what they meant to each other, an enduring connection forged through song. The gratitude was mutual. Take a brother like you to get through to the man in me.

“Shooting Star” & “Stella Blue”

The moon and stars were out at Riverbend ’24. You could see them in the sky, but you could also hear them in Dylan’s setlist. The man in the moon makes his rounds in “Under the Red Sky,” and another nightcrawler creeps around in “Soon After Midnight” with the moon in his eyes. Not to be outshone, “Mr. Blue” has his head in the stars from the start:

Our guardian star lost all its glow

The day that I lost you

Lost its glitter, lost its glow

Silver turned to blue

Stars streak across Dylan’s beautiful elegy “Shooting Star.” The title image refers not only to a celestial phenomenon but also to a star performer who shines brightly but burns out quickly.

I seen a shooting star tonight slip away

Tomorrow will be another day

I guess it’s too late to say the things to you

That you needed to hear me say

I seen a shooting star tonight slip away

The song’s arc is a downward parabola, rising sharply then plummeting abruptly. As I mentioned in the 1992 chapter (featuring Dylan’s only other performance of this song in Cincinnati), “Shooting Star” seems inspired by the deaths of two musical brothers: John Lennon and Richard Manuel.

The title applies with piercing precision to Lennon, a star who was shot to death by an obsessed fan. It’s also moving to hear Jim Keltner play on “Shooting Star,” knowing what a good friend and frequent collaborator he was with Lennon.

In previous installments I sometimes complained about Dylan’s up-singing: his habit of vocally leaping up the scale at the end of each line. This wouldn’t be a problem if it were rooted in the acute emotion of the moment; but instead it devolved into a vocal tic and a symptom of disengagement. Listen to “Shooting Star” at Riverbend ’24, particularly the final verse, and you’ll hear the opposite technique: down-singing. He descends the scale with each line like he’s rolling barrels down the plank of a cargo ship.

But it works. Down-singing suits Dylan’s aging vocal range much better than up-singing ever did. Furthermore, this vocal styling doesn’t feel random or artificial, but rather intentional, engaged, and appropriate to the material. His voice mirrors the descent of the falling star. He “climb[s] a ladder to the stars” [“Forever Young”] but then tumbles down “where all ladders start / In the foul rag and bone shop of the heart” [Yeats’s “The Circus Animals’ Desertion”].

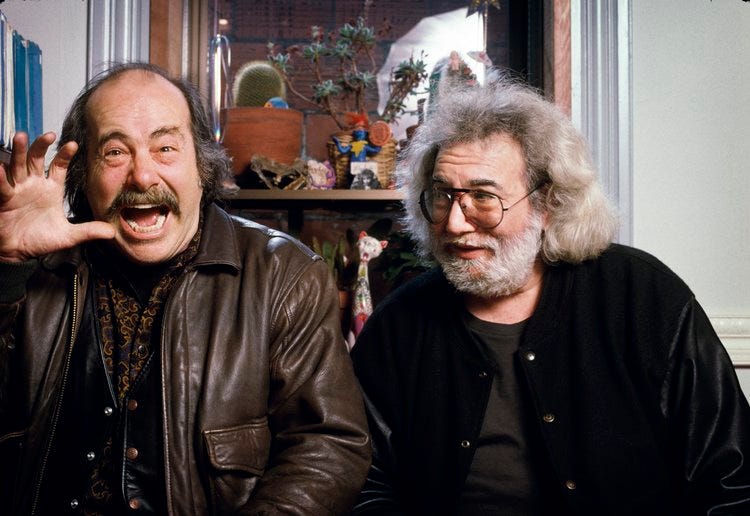

The brightest star at Riverbend ’24 is “Stella Blue.” The title translates as Blue Star, and it makes for a lovely coupling with The Fleetwoods/Bobby Vee cover: Mr. & Mrs. Blue. Dylan began introducing Grateful Dead covers into his setlists in 2023. He debuted “Stella Blue” on June 23, which would have been lyricist Robert Hunter’s 82nd birthday. This is my favorite Dead cover by Dylan, so I was excited to bask in the glow of Stella by starlight on the Ohio River.

The Grateful Dead have a tight connection to Dylan’s heart. He joined them for a few shows in 1986, then toured with them in 1987. He credits the band, and particularly Jerry Garcia, with reconnecting him to the wellspring of his own songs and inspiring his recommitment to live performance. Dylan collaborated with Robert Hunter on several songs, beginning with “Silvio” in 1988. The duo co-wrote most of the songs on Dylan’s 2009 album Together Through Life.

Hunter penned the lyrics to “Stella Blue” and Garcia later composed the melody. The song was first released on the album Wake of the Flood (1973), and Garcia delivered countless sublime performances over the years. As Court Carney notes, “‘Stella Blue’ became a mainstay of the deep second set for the band: a late ‘Jerry Ballad’ respite among the cosmic storm-cloud denouement. A song tinged in sadness about never quite matching one’s potential, ‘Stella Blue’ meant something to Garcia and, decades later, clearly signified something to Dylan.”

As I hear it, “Stella Blue” is not only a song but also a song-within-a-song. Whenever the beleaguered singer is down and out, second-guessing his life choices and struggling to hear his vocational calling—think Dylan in the eighties—he can play “Stella Blue” again and remember why music matters. The song encompasses past, present, and future: 1) a song about how he got stuck here, 2) the song he’s singing here and now to get unstuck, and 3) the song he must continue singing because he needs to play it and we need to hear it.

All the years combine

And they melt into a dream

A broken angel sings from a guitar

In the end there’s just that song

Come cryin’ in the night

Through all the broken dreams and vanished years

Stella Blue

Stella Blue

As Fred Bals points out, “The song’s title might have multiple inspirations, the most popular theory being that it’s a reference to a Stella guitar, a low-cost alternative to pricier Gibson and Martin guitars, and which was often sold in a cheap, blue-lined case. Lead Belly played a Stella, as did many street musicians of the 1920s and ’30s.”

Bals offers another intriguing theory: “Or perhaps Hunter was inspired by Picasso’s ‘Blue Period’ painting of an elderly musician, a haggard man with threadbare clothing, who is hunched over his guitar while playing in the streets of Barcelona, incidentally where Bob Dylan debuted his cover of ‘Stella Blue.’” Indeed, the old guitarist pretty much looks the way the song feels.

According to Court, “Although the song tends not to unveil its narrative secrets, the lyrics allude to a workaday musician, far from home, far from fame, who continues to step up to the microphone. A life defined by cheap hotels and rusted strings.” Dylan has stayed in those hotels and played on those strings. He knows this song well before he starts singing:

I’ve stayed in every blue-light cheap hotel

I can’t win, can’t win for trying

Dust off these rusty strings and

Just one more time

Lord, I wanna make ’em shine

Hunter wrote the lyrics to “Stella Blue” in 1970 at the Chelsea Hotel, the same place where Dylan began writing “Sad-Eyed Lady of the Lowlands” for his new bride Sara. When Dylan sings, “Lord, I wanna make ’em shine,” I hear an echo of “Lay, Lady, Lay”: “Whatever colors you have in your mind / I’ll show them to you and you’ll see them shine.” The image of dusting off those rusty strings reminds me of another Dylan lay: “Lay Down Your Weary Tune.”

Lay down your weary tune, lay down

Lay down the song you strum

And rest yourself ’neath the strength of strings

No voice can hope to hum

As for the weary tune of “Stella Blue,” Deadhead Elvis Costello considers it “the most beautiful melody Jerry ever wrote” (qtd. Mahan & Jarnow). In Robert Hunter’s online journal, he described the song as the perfect marriage of words and music:

“Stella Blue” is unique. Nothing else like it. The Major, major 7th, suspended four to the 4th chord which opens it, then the drop to the minor in the ninth bar, set a dark and wistful mood that couldn’t be more accommodating for the lyric, as well as standing beautifully without it. There’s no feeling the words could exist in any other setting or that the setting could take other words. I like that about it. It becomes a reality all its own. (qtd. Mahan & Jarnow)

Interestingly, what prompted these reflections from Hunter was listening to Willie Nelson’s cover for his 2006 album Songbird: “Just heard Willie Nelson doing ‘Stella Blue’. I dig the way he understates and lets the words carry the message. Mastery. I felt, somewhere around the second verse, that Jerry was listening with me. An extraordinary feeling” (qtd. Mahan & Jarnow).

I feel the same way about Dylan’s “Stella Blue.” His performance at Riverbend ’24 feels like a ghostly incantation, a ceremony for summoning and honoring the spirits of dead brothers.

Dylan explicitly claimed Garcia as a brother in his obituary after the big guy’s death: “There’s no way to measure his greatness or magnitude as a person or as a player,” wrote Dylan in 1995. “He is the very spirit personified of whatever is muddy river country at its core and screams up into the spheres. He really had no equal. To me he wasn’t only a musician and a friend, he was more like a big brother who taught and showed me more than he’ll ever know.” An inconsolable Dylan concludes, “There’s no way to convey the loss. It just digs down really deep” (1168). He eventually realized that the best way to convey the loss was through song. Enter “Stella Blue.”

In the genealogy of Dylanology, Court Carney is one of my closest brothers. He ruminates, “I have thought a lot about vulnerability within the context of Dylan and relatedly within the context of listening to Dylan as I try to decode the complicated ways emotion fuses the musician to the listener.” In Court’s probing and persuasive assessment, the glue that binds brother to brother, musician to song, and singer to listener is vulnerability. “Stella Blue” is the epitome of vulnerability.

In October 2023, hosts Rich Mahan & Jesse Jarnow devoted their fantastic The Good Ol’ Grateful Deadcast to “Stella Blue.” Guest Scott Metzger admires Garcia’s guitar virtuosity, but he locates the song’s true magic in the vulnerable vocals:

The delivery, that’s the thing about Garcia’s vocals, right? I think the vulnerability that he had in the singing is the true X factor of his presentation as a musician. The playing, obviously great and everything. I feel like a lot of players over the years that are going for that Garcia thing—whatever that means to people—have been able to kind of dissect the guitar playing: dissect the gear Garcia used, or the kind of pick-ups and stuff. People have come close to the sound. But the one thing that I feel like is still the Holy Grail, and the thing that really is just the X factor that has not been touched, is the Garcia ballad singing. That, to me, is worth the price of admission right there. Every time. (qtd. Mahan & Jarnow)

If you’re looking for confirmation of Metzger’s thesis, listen to “Stella Blue” from Louisville’s Freedom Hall on June 18, 1974. Or better still, check out October 21, 1978, at San Francisco’s Winterland Ballroom. Garcia cries like the wind down every lonely street that’s ever been.

In that same Deadcast, Nick Paumgarten identifies fragility as the crucial component to the best performances of “Stella Blue.” Referring specifically to the 1984 show at Berkeley’s Greek Theatre, Paumgarten says, “That kind of ‘Stella Blue’—that mid-’80s ‘Stella Blue,’ before the coma, partly because he was so fragile—that’s my favorite ‘Stella Blue.’ Jerry sang like some degenerate castrato, with this beautiful tenor just barely holding on.”

If you wonder what a “degenerate castrato” sounds like, listen to Jerry’s performance of “Stella Blue” right here at Riverbend on June 30, 1986. The Dead closed that show with a Dylan cover: “When Quinn the Eskimo gets here / Everybody’s gonna jump for joy!” It was basically a teaser for their next show up the road in Akron, where they were joined on stage for the first time by Bob Dylan. Eight days later, Garcia collapsed into a diabetic coma.

Dylan’s voice differs starkly from Garcia’s, but he manages to convey the same sense of loss, vulnerability, fragility, and the damage done at Riverbend ’24. He howls at the moon like a lone wolf separated from his pack.

“Stella Blue” is the perfect vehicle for showcasing late Dylan’s ragged glory. His voice has the aged craquelure of an Old Master painting: Mona Lisa with the highway blues. Jerry didn’t live long enough to sing “Stella Blue” at age 83—he died at 53. But as I listen repeatedly to the Riverbend ’24 bootleg, I imagine a ghostly duet between the reunited musical brothers, 29 years after Garcia’s death and 38 years after he sang the same song from this same stage.

It all rolls into one

And nothin’ comes for freeee

Nothin’ you can hold for very long

For you, when you hear that song

Come cryin’, cryin’ to the wind

Seem like all this life was just a dream

Stella Blue

Stella Bluuuue

Hunter wrote the words and Garcia composed the melody, but Dylan has lived every line, hasn’t he? He claims in Chronicles that “A song is like a dream, and you try to make it come true. They’re like strange countries that you have to enter” (165). Dylan makes the long strange trip all the way into this song. He exposes his vulnerability, shatters the fragile dream, then puts the pieces back together again, making “Stella Blue” shine night after night on the stages of the world. I’m reminded of that great quote from Oscar Wilde: “We are all in the gutter, but some of us are looking at the stars.”

After his musical brother’s death, Robert Hunter wrote a final poem for Jerry Garcia. The resemblance is so uncanny between Hunter’s “Last Words for Jerry Garcia” and Dylan’s Riverbend ’24 concert that it’s worth quoting the elegy in full:

Go naked in the world

Wind for your cloak and coverlet

Whom the gods love best

They reward with early death

Gather them into the sun

Reflect them in moonlight

Crown them with comets

Anoint them with shooting stars

Go naked to the throne of love

Go as stars go

Arrayed in their own incandescent light

Go and our hearts go with you

Return to the source of the soul

By way of the sacred river

Royal road to the sea

Where all shall be music

And dreams shall be dreams no more

But visions of the world’s foundation

Scattered among stars

Dust shall be dust

And the voice of dust shall be music

Pleasing God who sent it forth

In search of melody

To crown his silence

With eternal song

I was going to give Hunter the final word. But then I went to see the wonderful Dylan biopic A Complete Unknown, and it serendipitously supplied me with a new and more succinct conclusion. Like the song-within-a-song “Stella Blue,” James Mangold makes prominent use of a film within his film: Now, Voyager, released in 1942, the year Garcia was born. When I heard Bette Davis deliver her tagline, it struck me down to the ground. “Oh, Jerry. Don’t let’s ask for the moon. We have the stars.”

Works Cited

Bals, Fred. “A Theme Time Radio Hour take on Dylan’s Outlaw Tour Covers Part 3: ‘Stella Blue.’” Medium (1 July 2024), https://fredbals.medium.com/a-theme-time-radio-hour-take-on-dylans-outlaw-tour-covers-part-3-stella-blue-72a6ac68ed0f.

Berry, Chuck. “Little Queenie.” Berry Is on Top. Chess, 1959.

Bootleg audio recording. Taper Domino, remastered by Bennyboy. Riverbend Music Center, Cincinnati (11 September 2024).

Carney, Court. “Wanted Men: Bob Dylan and the Vulnerability of Brotherhood.” The Dylan Review 6.2 (2024-25).

Cougar, John. “Jack & Diane.” American Fool. Mercury/Island/UMe, 1982.

Dylan, Bob. “2016 Nobel Lecture in Literature.” The Nobel Prize (5 June 2017), https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/literature/2016/dylan/lecture/.

---. Chronicles, Volume One. Simon & Schuster, 2004.

---. “Jerry Garcia’s Obituary.” Every Mind Polluting Word: Assorted Bob Dylan Utterances. Ed. Artur Jarosinski. Don’t Ya Tell Henry, 2006, 1168.

---. The Official Lyrics. The Official Bob Dylan Website.

https://www.bobdylan.com/.

E.B. Concert Review, Riverbend Music Center, Cincinnati (11 September 2024), https://www.boblinks.com/091124r.html.

The Fleetwoods. “Mr. Blue.” Mr. Blue. Dolton, 1959.

The Grateful Dead. “Stella Blue.” Wake of the Flood. Grateful Dead, 1973.

Gray, Michael. Song & Dance Man III: The Art of Bob Dylan. Continuum, 1997.

Heylin, Clinton. Still on the Road: The Songs of Bob Dylan, Vol. 2: 1974-2008. Constable, 2010.

The Holy Bible. King James Version.

Hunter, Robert. “Last Words for Jerry Garcia.” Grateful Dead reddit, https://www.reddit.com/r/gratefuldead/comments/x3az7n/bob_weir_reading_poem_by_robert_hunter_at_jerrys/.

Interview with Bobby Vee. Bobby Vee Fan Site (2020), https://www.bobbyvee.com/interview/.

Jennings, Waylon and Willie Nelson. “Mammas Don’t Let Your Babies Grow Up to Be Cowboys.” Waylon & Willie. RCA Victor, 1978.

Mahan, Rich, and Jesse Jarnow. “Wake of the Flood 50: Stella Blue.” The Good Ol’ Grateful Deadcast (5 October 2023), https://www.dead.net/wake-flood-50-stella-blue.

Nelson, Willie. “Whiskey River.” Shotgun Willie. Atlantic, 1973.

No Direction Home. Directed by Martin Scorsese. Paramount Pictures, 2005.

Now, Voyager. Directed by Irving Rapper. Warner Brothers, 1942.

Padgett, Ray. “Jim Keltner Talks Thirty Years of Drumming for Bob Dylan, Part 1.” Flagging Down the Double E’s (22 July 2021),

.

Rotolo, Suze. A Freewheelin’ Time: A Memoir of Greenwich Village in the Sixties. Aurum Press, 2009.

Seel, Steve. “Bobby Vee reflects on a young Bob Dylan.” MPR Archive (26 March 2007), https://archive.mpr.org/stories/2007/03/26/bobby-vee-reflects-on-a-young-bob-dylan.

Seger, Bob & the Silver Bullet Band. “Rock and Roll Never Forgets.” Night Moves. Capitol, 1976.

Teasdale, Sara. “There Will Come Soft Rains.” Poets.org, https://poets.org/poem/there-will-come-soft-rains.

Wilde, Oscar. Lady Windermere’s Fan: A Play about a Good Woman. E. Mathews and J. Lane, 1893.

Yeats, W.B. “The Circus Animals’ Desertion.” Poetry Foundation, https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/43299/the-circus-animals-desertion.

Another beautiful essay, Graley. Tears in my eyes several times.

“it felt like I had entered the song”—this is all we can ever hope to obtain. When these moments hit, it’s as if you’ve dissolved into the cosmos. The only thing that matters.