Summer is reading season, so I figured I’d pass along a couple recommendations targeted specifically toward Dylan fans. Let me turn you on to Dana Spiotta. I love her fiction and think you will, too. She is the award-winning author of five novels: Wayward (2021), Innocents and Others (2016), Stone Arabia (2011), Eat the Document (2006), and Lightning Field (2001). She also teaches in the MFA program at Syracuse University.

You don’t have to be a Dylan fan to appreciate Spiotta’s fiction, which stands sturdy and tall on its own merits. But she clearly knows her stuff when it comes to Dylan. So if you’re a fan—and you wouldn’t be reading this newsletter otherwise—then you’ll catch elements of Spiotta’s writing that would fly past the nets of the uninitiated. I want to draw your attention to two novels in particular: Eat the Document, which I’ll be focusing on here, and Stone Arabia, which I’ll write about in my next installment. No prerequisites or advance homework necessary. I’ll give you all the info you need to follow along, and I hope you’ll be inspired to read the books on your own. Feel free to share your own impressions and discoveries in the comments.

I’m interested in studying passages where Spiotta’s art intersects with Dylan’s art, where her fictional worlds collide with our experiences as Dylan devotees, and where her meditations guide us into deeper contemplation of both of their works. Frankly, this is also an excuse to quote at length from a much better writer than me. Please resist the usual temptation to eye-skip over block quotations because those are probably going to be the best parts.

Radicals & Fugitives

The singer in “Subterranean Homesick Blues” counsels, “Get dressed, get blessed / try to be a success.” The first line of Eat the Document moves in the opposite direction: “It is easy for a life to become unblessed” (3). The unblessed life is still worth living, and worth examining.

Mary Whittaker is part of a radical leftist group, never named but clearly modeled after organizations like the Weatherman (aka the Weathermen, the Weather Underground) who pursued militant strategies for opposing institutionalized racism in America and protesting the war in Vietnam. As you probably know, this group took its name from Dylan’s “Subterranean Homesick Blues”: “You don’t need a weatherman / To know which way the wind blows.”

Mary Whittaker was involved in a protest bombing that killed an innocent housekeeper in 1972. She and the other members of her cell split up, went into hiding, assumed false identities, and became fugitives from justice and exiles from their former lives. This is how Mary’s life became unblessed.

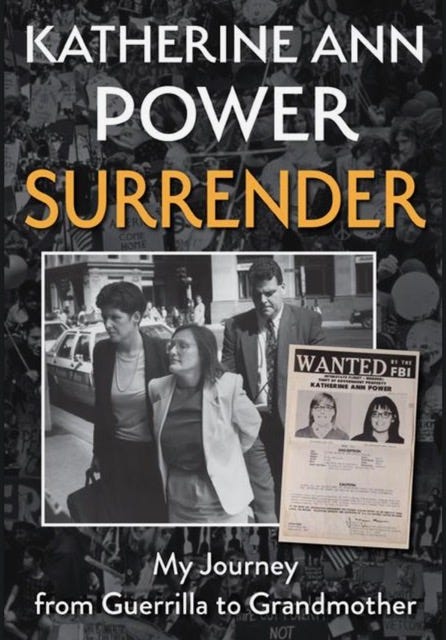

In multiple interviews Spiotta has credited Katherine Ann Power as an early inspiration for this novel.

Power was a leftist activist involved in a Boston bank robbery in 1970 that resulted in the death of a security guard. She was a fugitive living under aliases for 23 years before turning herself into authorities in 1993 and serving a jail sentence. To be clear, the protagonist of Eat the Document isn’t merely an avatar for Katherine Ann Power. The real-life fugitive was merely one leaping-off point for Spiotta’s fictional portrait.

From the very first page, Mary articulates her fugitive condition using Dylan’s language: “Her mistakes—and they were legion—were not lost on her. She knew all about the undoing of a life: take away, first of all, your people. Your family. Your lover. That was the hardest part of it. Then put yourself somewhere unfamiliar, where (how did it go?) you are a complete unknown. Where you possess nothing” (3). You will instantly recognize the echo from the chorus of “Like a Rolling Stone”:

How does it feel?

How does it feel?

To be out on your own

With no direction home

Like a complete unknown

Like a rolling stone

Dylan’s song implies that, for all the devastating loss that comes from being stripped of one’s former status, there can also be something liberating about self-annihilation:

When you ain’t got nothin’

You got nothin’ to lose

You’re invisible now

You got no secrets to conceal

Mary has stood in Miss Lonely’s shoes, however, and she sees things differently, albeit still in the lexicon of Dylan: “She discovered, despite what people may imagine, having nothing to lose is a lot like having nothing. (But there was something to lose, even at this point, something huge not to lose, and that was why this unknown, homeless state never resembled freedom)” (3). Mary’s approach to loss is less like “Rolling Stone” and more like “Tryin’ to Get to Heaven”: “When you think that you’ve lost everything / You find out you can always lose a little more.”

What’s in a name? Before the bombing, Mary’s boyfriend Bobby Desoto insisted that they adopt new names within the movement. “‘All cultures have naming ceremonies. You have a given name, but then you get a chosen name. It’s part of a transformation to adulthood. They tell you who you are, and then you decide who you are. It’s like getting confirmed, or getting married’” (8).

After the bombing, Mary has a different motivation for finding a new name and identity. She settles on the name Caroline Sherman, and again her inspirations are musical:

She wrote it all out on a piece of spiral notebook paper. Her age: twenty-two. Birthplace: Hawthorne, California. Name: Caroline. Hawthorne was just another suburban town in California, which you could bet was more like all the other suburban towns in California than it was different, and it would do just fine even if her favorite band was also from Hawthorne. And Caroline is a pretty girl’s name that also happened to be the name of the girl in one of her favorite songs. (9)

The references here are to the song “Caroline, No” by the Beach Boys, who hailed from Hawthorne.

“Caroline, No” is the last song on Pet Sounds. The final verse resonates strongly with the position Caroline (née Mary) now finds herself in:

Could I ever find in you again

The things that made me love you so much then?

Could we ever bring ’em back once they have gone?

Oh, Caroline, no

The novel moves back and forth in time. Some sections are set in the early seventies as Mary adapts to life in under an assumed identity, first as Caroline Sherman and later as Louise Barrot (more on that name later). Other sections are set in the late nineties, alternating between the suburban Seattle lives of Louise and her teen son Jason, and urban Seattle life for Bobby Desoto, now Nash Davis, who manages a subversive bookstore called Prairie Fire.

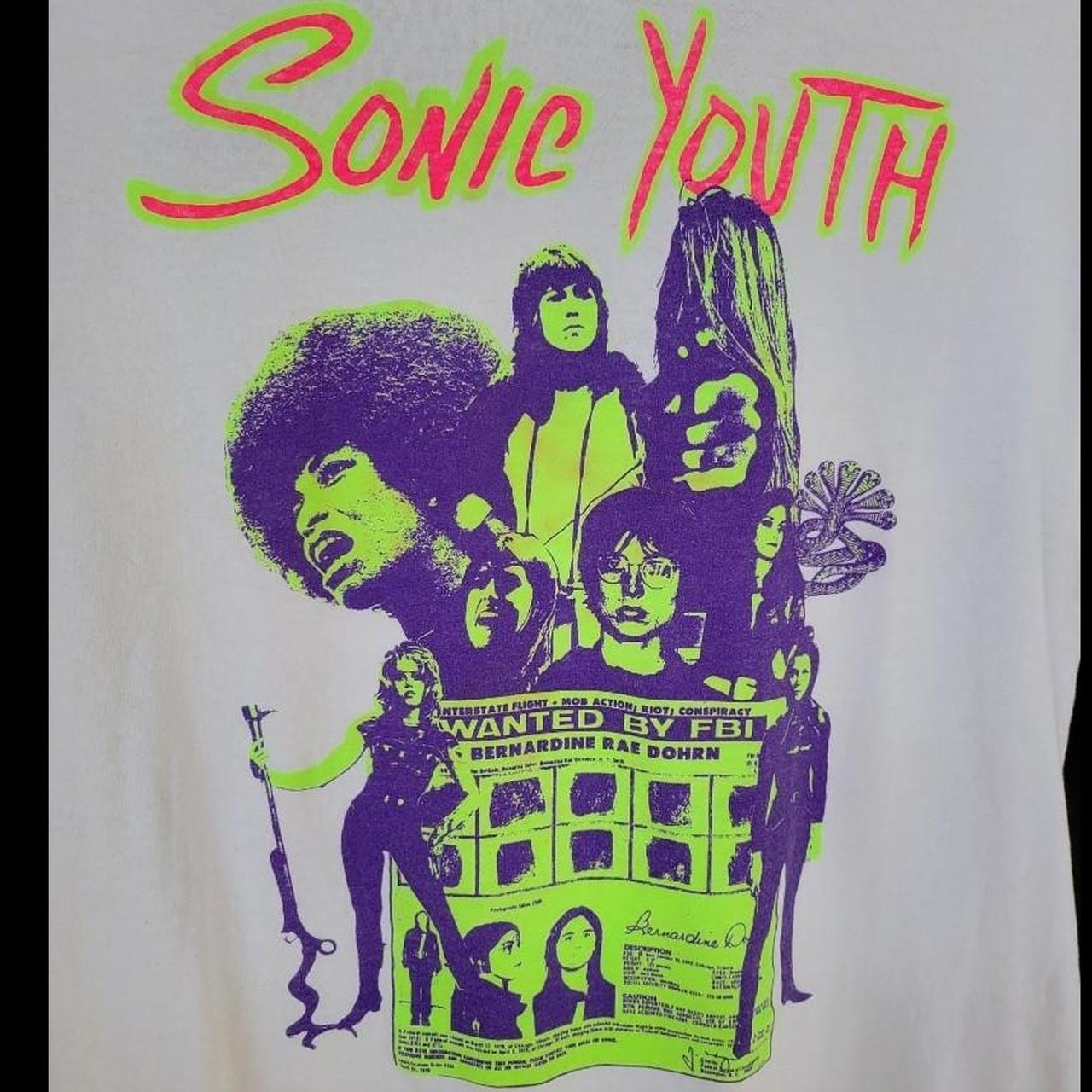

Nash’s fictional bookstore takes its name from the 1974 Weather Underground manifesto, Prairie Fire: The Politics of Revolutionary Anti-Imperialism. Two prominent members from the group, the couple Bernardine Dohrn and Bill Ayers, are surely inspirations behind Mary Whittaker (aka Caroline Sherman) and Bobby Desoto (aka Nash Davis).

Members of the Weather Underground became fugitives after an accidental explosion in a Greenwich Village townhouse killed three of their own. This disaster prompted the leaders to reconsider their strategies. Their new directives, which included moving away from military tactics and supporting a more prominent role for women in the movement, were delivered in a communiqué signed by Bernardine Dohrn and titled “New Morning – Changing Weather,” once again taking its name from Dylan.

In an interview with Florence Dore for The Ink in the Grooves: Conversation on Literature and Rock ’n’ Roll, Spiotta located Dylan at the intersection of the counterculture and political resistance:

In writing Eat the Document, a novel about an antiwar activist who must live underground, it felt essential to the cultural context of 1972 to include the music of the era. The spirit of the antiwar movement was located in the music scene—more so than in books, for instance. The fact that the Weatherman got their name from “Subterranean Homesick Blues” shows the way music of the era shaped how the activists saw themselves. I chose Eat the Document because it has the sound of the language used at the time—like “Steal this Book”—but also because of Dylan, and because it was for many years an underground/lost film, which fits with the novel’s interest in the cryptic history of American resistance.

“Temporary Like Achilles”

During the protagonist’s early days in hiding, she moves to Oregon and makes friends with a woman named Berry. As they get to know each other better, Caroline lets slip that her boyfriend’s name was Bobby. You may have already wondered if the two Bobby D’s are related (Desoto and Dylan). Spiotta seems to slyly confirm as much when, on the very same page as Caroline’s slip, we’re told this: “They were listening to the latest Dylan ‘comeback’ album, Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid. Berry played ‘Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door’ three times in a row. They both agreed it was the only good song on the album” (109). Knock-knock: who’s there? You know who.

The Dylan rap continues: “Caroline thought Berry looked like the women Dylan wrote about, bejeweled and disheveled and bewitching, ornate in body and soul, or at least it looked that way from where Caroline sat, stoned and a little drunk” (109-10). It takes one Dylanesque character to recognize another. Miss Lonely, meet Isis. Queen Berry, she’s my friend.

One of the most pivotal chapters in the novel is named after a Dylan song, “Temporary Like Achilles.” This section warrants a deep dive. By 1973, Caroline and Berry have become best friends. When Caroline starts to feel the heat in Oregon, she flees across country to New York and Berry accompanies her. They seek sanctuary at a rural women’s commune outside Little Falls, NY. At the beginning of the chapter, the two friends have a musical conversation, not about Dylan this time but about the Beach Boys’ “Good Vibrations.”

When the song comes on the radio, Caroline turns it up, recalling its exalted place in her youth. She braids Berry’s hair and remembers: “‘This was the song my junior year at high school. That fake end, when it segues into this whole other sounding song but still is connected, somehow, to the old one—that blew my mind’” (179). Berry is underwhelmed: “‘This song is all right.’” Nope, not good enough: “‘This is a great song,’” insists Caroline (179).

Berry explains what turns her off:

“Thing about the Beach Boys, it’s not that they’re too corny or whatever. I don’t mind that. But they are completely not sexy—”

“Yes, that’s true—”

“Utterly sexless, even. Unless you are twelve years old.”

“That’s not the point.”

“What else could be the point?”

“Loneliness. Longing. The sadness that leaks through all that enforced sunny cheer. It’s heartbreaking.” (179)

Caroline makes a little progress, coaxing a slight upgrade from Berry: “‘This is a cool song’” (179). Cool is good, but still not good enough. Caroline hears much more in “Good Vibrations”: “‘It’s in the sound, not the words. It’s the way you feel, or rather the feeling you get. Like slightly off, rancid America, you know?’” (179). Berry begins to relate, not with “Good Vibrations,” but with the totemic importance of music: “Berry turned to her and smiled. Her blond braids glittered in the sun. ‘When you move somewhere new, it’s good to have someone or something from your past there with you, reminding you of who you are, don’t you think?’” (179).

The upshot of this conversation is that special songs harness the time-defying, self-preserving power to keep the listener rooted firmly to their origins and essence. Spiotta establishes this premise at the beginning of the chapter, but then she shakes the foundations of this belief like a California earthquake by chapter’s end.

This is where “Temporary Like Achilles” comes into play. I think Spiotta drafts Dylan’s song into service as a challenge and oppositional counterforce to the reassuring consolations Caroline clings to in “Good Vibrations.”

If you’re looking for permanence and stability, then Dylan ain’t your guy. Everything passes, everything changes in Dylan’s songs, where he not busy being born is busy dying. As the title announces, things are impermanent in the world of this song, temporary. Things are not what they seem, not what they once were. Identity isn’t a fixed essence but a series of shifting masks.

The singer pleads with a woman, who is probably a man in drag—“Honey, why are you so hard?” indeed! Before the Trojan War, the great warrior Achilles spent time in exile, hiding out as a woman on the island of Skyros. So Dylan’s title isn’t as arbitrary as it sounds, and neither is Spiotta’s borrowing.

If we take Caroline’s advice—“‘It’s in the sound, not the words’”—then just listen to sound of “Temporary Like Achilles.” Not exactly a sun-soaked Beach Boys song, is it? Now this is rancid America. This is the sound of being strung out at 3 a.m., depleted, exhausted, too lost and wasted to find your way home. “Temporary Like Achilles” is “Bad Vibrations.” And that’s precisely the direction this chapter is headed.

After spending two months isolated in the woods on the commune, Caroline and Berry decide they’re ready to get out and let loose: go to a bar, drink and smoke, hook up with a couple random strangers—feel young and free again. They hitch a ride and make it to a bar, but then the plan comes unraveled.

Harking back to the earlier reference to Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid, Caroline notices that the bar has an outlaw theme. “The wall behind Berry was decorated with posters from the Wild West. A desperado-outlaw theme halfheartedly accomplished with Jesse James and Billy the Kid wanted posters” (185). The criminal décor includes a photogenic contemporary outlaw:

Caroline noticed a black-and-white poster that said ‘FBI Most Wanted’ over a large picture of the Weather Underground siren Bernardine Dohrn. She was in a leather miniskirt and knee-high boots. It showed her fingerprints and vital stats just like a real FBI poster, but surely doctored to feature an alluring body shot of Dohrn instead of a mug shot. Caroline had seen the body shot before, of course, it was one of the reasons some women distrusted Dohrn, the way she seemed to play into the porno of outlaw chick with great legs. But she did look great, didn’t she? (185)

Spiotta plays with the term “most wanted,” showing how fierce intellectuals and political rebels get reduced to objects of desire as hot “outlaw chicks.” This scene contributes to a larger theme in Eat the Document about the commodification of radicalism. Forces within the culture contain threats to the status quo by absorbing, redefining, eroticizing and/or monetizing them.

In this case, the activist lioness Bernardine Dohrn is tamed into a passive sex kitten for public consumption by horndogs in a dive bar, feeding their visual appetites as surely as the salty pretzels whet their thirsts. Also note that, having begun the chapter with the asexual innocence of the Beach Boys, Spiotta has now placed Caroline and Berry in a seedy joint surrounded by images of sex and crime. The rising sense of menace and foreboding is palpable.

As Caroline scans the wall of outlaws, “she soon noticed other, smaller FBI wanted posters. These were not altered but actual tear sheets, like at the post office. Some were covered over partially and hard to read. At Bernardine’s left toe she could see a poster of another woman fugitive, whom Caroline took several breathless seconds to realize was her, Mary Whittaker” (185-86). Oh, shit! Caroline bails on date night and retreats to a motel with Berry to regroup.

If you were worried that something bad was going to happen to them in that bar, then you might breathe a sigh of relief. You might even wonder if the evening’s consummation is headed in a more promising direction. But Spiotta is just luring readers into letting down our guard before delivering a gut punch.

First, however, comes a fateful confession. The two women get high and drunk, and Caroline tells Berry the truth about who she really is and what she did. During this confession, we get our clearest picture yet of how Mary became radicalized. She sounds like Bernardine Dohrn. She also sounds like Dylan in “Masters of War.” She is filled with anger and disgust at the greedy profiteers perpetuating the Vietnam War:

“Napalm, someone makes that, you know? Someone sits in an R and D lab and thinks, Let’s make it burn, but hey, let’s add plastic so it will also stick. But look, they just jump in the water, so let’s add phosphorus so it burns underwater, burns though to the bone. So people on the board of Dow or Monsanto or GE decide that this is a good way to make money, and they are so removed from the consequences. These men are at such remove they could help prolong it a year, two years, and is it right that that should cost them nothing? We are invisible to them. How smug they were, ignoring us. I wanted them to feel some consequence, pay some price for the terrible things they did for pride or power or profit.” (189)

Mary Whittaker wanted to bring the war home to the masters of war. Instead, all she managed to do was kill a housekeeper, damage some property, and destroy her former life, while the war rages on unabated. And more suffering is just around the corner.

The last two pages of the “Temporary Like Achilles” chapter are the most disturbing in the novel. Realizing she has made a terrible mistake by telling her secrets, Caroline leaves Berry and hitchhikes her way out of New York. Somewhere in Pennsylvania, she hitches a ride with the wrong couple, and things take a terrifying turn. The man rapes Caroline in the backseat while the woman (girl?) drives and watches in the rearview mirror. Caroline wills herself to dissociate from the assault, detaching her mind from her body. Afterwards, the couple dumps Caroline on the side of a desolate road, leaving both the character and the reader blindsided and brutalized.

In an interview with Liza Johnson for The Believer, Spiotta was asked about her approach to revolutionary violence, but I think her answer also applies to her approach to sexual violence: “I always think the novelist should go to the culture’s dark places and poke around. Pose a lot of hard questions. Tell me it’s forbidden, unthinkable, and that’s where I want to go.” So what purposes does this terrifying scene serve in Eat the Document, and specifically in the “Temporary Like Achilles” chapter?

This experience proves a defining moment for Caroline, though not necessarily in the ways you might expect. On one level, she feels obliterated by this traumatic, dehumanizing attack. On another level, however, she adopts a steely resolve as she looks westward and imagines her way forward. Gone is the character from the beginning of the chapter, clinging to her former life while nostalgically listening to “Good Vibrations.” By the end of the chapter, Caroline cuts ties with the past and commits fully to reinventing her reality for the future:

Then she thought: It never happened. She would never speak of it, or let herself think of it, ever. She was quite certain that you could change your past, change the facts, by will alone. Only memory makes it real. So eliminate the memory. And if it was also true that there were occasions when she couldn’t control where her mind went—a dream, a cold sweat at an unexpected moment, an odor that would suddenly betray her—time would improve it. Time lessens everything—the good things you desperately want to remember, and the awful things you need to forget. Eventually all will be equally faint. This was one thing her second life had taught her about how humans endure. (195, emphasis in original)

Don’t look back. Mary Whittaker is dead; Caroline will survive by whatever means necessary. “It was at this point,” she reflects at the end of the chapter, “that she began to inhabit her new life as her only life” (195).

Spiotta anticipates this act of willed amnesia early in the novel. Way back on page 10, during the first few days of Mary’s new life as Caroline, we get this passage about the relationship of past and present, memory and forgetting:

She fell asleep those first few nights committing the “facts” of her new identity to memory. And for a while it would be impossible not to be confused and self-conscious during even the most mundane exchanges. Do you drink coffee? And she would have to think, Well, I always have, but now, well, maybe I don’t. And she would reply, “No, I never touch the stuff.” And the extra step of comparing the present with the past would keep her in a constant state of reaction. Until it stopped, later and slowly—but she didn’t know about that yet, couldn’t even imagine it. Yet one day she would have lived her new life so long that the conjuring of the old life would seem like a dream, an act of imagination. Eventually it would almost feel as though it had never happened. This was the way it was supposed to go down. A secret held so long that even you no longer believe it isn’t really you. But at this point she had no idea that this could go on indefinitely. She had no idea she would find that her identity was more habit and will than anything more intrinsic. (10, emphasis added)

Note Spiotta’s deft use of omniscience here. We’re still almost two hundred pages away from the assault scene that will prompt Caroline’s denial and repression (“It never happened”), but the Cassandra-like narrator foresees what’s coming and the impact it will leave behind, and she foreshadows it for the reader.

So often we talk about Dylan’s protean superpower for reinvention in exclusively positive terms. He has everything he needs, he’s an artist, he don’t look back. But Spiotta’s portrait of Caroline reminds us that often the people who make the most radical breaks from their past don’t do so voluntarily but are motivated by desperate necessity as their only way to survive experiences that might otherwise crush them. Maybe the singer in “Rolling Stone” can scarcely fathom what triggered Miss Lonely’s fall, or all the wounds she accumulated on her tumble down. How does it feel to stare into the vacuum of his eyes after he took from you everything he could steal? Caroline knows.

Caroline relocates to Los Angeles and invests considerable effort into crafting a new self. She looks through infant obituaries and finds a baby who died before receiving a social security number. She uses this information to create a reliable paper trail for her new identity as Louise Barrot. This happens in a chapter titled “Dead Infants”—plural, indicating more than one dead child. I wonder if this new shadow self is an allusion to Dylan’s “Visions of Johanna”:

Louise, she’s all right, she’s just near

She’s delicate and seems like the mirror

But she just makes all too concise and too clear

That [Mary Whittaker’s] not here

I also suspect that Louise Barrot is a clever riff on Jean-Louis Barrault. This famous French actor played the mime Baptiste Deburau in the classic Les Enfants du Paradis [Children of Paradise], a major influence on Dylan’s Rolling Thunder Revue film Renaldo and Clara. The chapter title “Dead Infants” also winks at (and subverts) the film title. Les Enfants Morts.

Fandom

In her interview with Florence Dore, Spiotta elaborates upon her deep personal and artistic influence from music and musicians:

I grew up listening to records alone in my room. The lyrics of the big icons, from Lou Reed to Dylan to Bowie to John Lennon—and on and on—certainly made me more playful with language. But it was the sensibility, maybe, that influenced me most. The refusal to play nice in punk rock, the lyrical nihilism of Television, the irony in Bryan Ferry, the perversity mixed with resistance in Dylan, the combination of authenticity and artifice in Gram Parsons, the soulfulness of Big Star—I could go on and on—all certainly help shape my idea of what stance an artist should have toward the culture.

Even if you haven’t read interviews with the author, it is obvious from her fiction that she’s a huge music fan. Several chapters in Eat the Document are framed as journal entries from Louise’s fifteen-year-old son Jason. These are some of the most interesting parts of the book for Dylanologists. Spiotta displays her intimate knowledge of obsessive fan culture through her portrait of Jason, who can’t get enough of his favorite band the Beach Boys.

Jason listens repeatedly to multiple outtakes of the same song from his bootleg of the Beach Boys’ album Smile. I’m sure many Shadow Chasing readers will relate to this immersion from your own experiences listening to Dylan bootlegs like The Cutting Edge or The Basement Tapes Complete.

Now, you might ask, why the hell does someone want to listen to all that? And in truth, when I realized what I had bought (ninety dollars, no less), at first I was disappointed. But, and this is a big but, there is something amazing about hearing the takes. It is as if you are in the recording studio when they made this album. You are there with all the failures, the intense perfectionism, the frustration of trying to realize in the world the sounds you hear in your head. Sometimes they abruptly stop after someone says “cut” because they lost it, it didn’t break their hearts enough, they just couldn’t feel it in the right places. Or someone starts laughing, or says suddenly, “Could you hear me on that?” What happens is you jump to a new level in your obsession where even the most arcane details become fascinating. You follow a course of minutiae and repetition, and you find yourself utterly enthralled. Listening deeply to this kind of music is mesmerizing in itself; the same song ten times in a row is like a meditation or a prayer. So it is quite apt to listen to the song “Our Prayer” in this manner. (22)

The author of this passage gets it—she gets us. This is how obsessive practices that might seem pathetic or pathological to outsiders can feel from the inside like a holy meditation for the devoted listener.

Fandom doesn’t just encompass the relationship of an individual listener to an individual artist. It also includes the peculiar interactions among fellow fans. Jason uses an example from the Byrds, but you can easily substitute your own favorite example from Dylan:

My friends—what few friends I have—are the types of guys who will argue about whether the rare RCA single version of “Eight Miles High” is superior to the track issued on Fifth Dimension, the Byrds’ album release. It isn’t, but it is cool to ask the question because it proves you know there are two versions and you are conversant with both. It is even cooler to maintain that the album—a common, reissued object—does have the superior version, and not the rare, hard-to-find single. (This is true, despite the fact, perhaps inconsequential, that the LP version is actually the superior version.) It is perverse, and very sophisticated, in these circles, to maintain the common, popular object is the better object. Only a neophyte or a real expert would argue such a thing. So are you getting the picture on my pals here? (72)

Yes! We apparently share the same pals, though in my group the equivalent is to argue that the officially released version of Blood on Tracks, largely rerecorded in Minneapolis, is superior to the original New York recordings. (Which is true.)

Like many of us, Jason goes back and forth between thinking of his musical devotion as a blessing or a curse. In pessimistic moods,

I wondered if my life was going to be one immersion after another, a great march of shallow, unpopular popular culture infatuations that don’t really last and don’t really mean anything. Sometimes I even think maybe my deepest obsessions are just random manifestations of my loneliness or isolation. Maybe I infuse ordinary experience with a kind of sacred aura to mitigate the spiritual vapidity of my life. (76)

However, in optimistic moods, he defends his passion:

I reconsidered my earlier despair—no, it is beautiful to be enraptured. To be enthralled by something, anything. And it isn’t random. It speaks to you for a reason. If you wanted to, you could look at it that way, and you might find you aren’t wasting your life. You are discovering things about yourself and the world, even if it is just what it is you find beautiful, right now, this second. (76)

I love the voice Spiotta gives Jason. He is witty and perceptive, but he’s also insecure and cannot say a thing directly without attaching caveats and disclaimers. He can barely finish a sentence before he is already formulating a rebuttal to his own argument, searching for an escape clause should he change his mind.

The thing of it is I don’t necessarily feel connected to Brian Wilson or any of the Beach Boys. But I do, I guess, feel connected to all the other people, alone in a room somewhere, who listen to Pet Sounds on their headphones and who feel the way I feel. I just don’t really want to talk to them or hang out with them. But maybe it is enough to know they exist. We identify ourselves by what moves us. I know that isn’t entirely true. I know that’s only part of it. (76)

I recognize this teenager. Hell, maybe I was him. Plug those headphones into Highway 61 Revisited and I feel like I still am.

One of Jason’s most interesting journal entries concerns lost albums. He offers a taxonomy of different subspecies of lost albums, including one subterranean beast you will recognize in the form of “jam sessions meant for private reference only. These eventually surface in legitimate form after years of being available extralegally as bootlegs. The most famous one is The Basement Tapes, the Dylan and the Band bootleg that everyone preferred to what Dylan actually put out (Nashville Skyline, which, of course, I like and actually prefer to The Basement Tapes)” (80). Okay, Jason, you’re allowed to like Nashville Skyline. But better than The Basement Tapes? Dude, please! And to think I was starting to identify with this kid.

The subject of lost albums comes up when Jason introduces his friend Gage to the obscure solo work of Beach Boys drummer Dennis Wilson. Check out Jason’s colorful verbal portrait:

Dennis Wilson is a man I hold very close to my heart. To most people he is still a tragic joke, a colorful loser, a complete disaster. How could I not love him? Dennis was famous for being not only the only Beach Boy who actually surfed but for being so incredibly derelict for the last ten years of his short life that he actually drowned in a boat slip in Marina del Rey in like six feet of water. He was also the “good-looking” Beach Boy. He was also the Beach Boy who hung around Charles Manson because of all the easy drugs and easy pussy. (As if being a rich, handsome rock star didn’t give him enough easy drugs and easy pussy and he needed Charles Manson’s, or maybe there was something particularly potent in unbathed, helter-skelter cult pussy.) (81)

Jason knows he’s not supposed to like Dennis Wilson or his music, but that just draws him in deeper. Any true music lover will recognize the tug of this magnetism:

Admittedly there are a lot of plink-plink so-type piano songs sung in this almost embarrassingly sad, rusty voice. These real dirgy, messed-up vocals, unashamedly full of self-pity and raw emotion. I found it operatic, a complete expression of a tortured, not-too-bright, not-too-gifted, weary guy. But here is the thing, say what you will about skill, technique, control, brilliance: this stuff is truly moving. To me anyway. I don’t know why, but I listen to that album and I start bawling, I really do. (81)

The same could just as well apply (minus the “not-too-bright, not-too-gifted” part) to some of my favorite Dylan performances from the deeper basement cuts, like “I’m Not There,” “Mr. Blue,” “Four Strong Winds,” or “One for the Road.”

When Jason plays Dennis Wilson for Gage, his friend is deaf to all its charms. “‘Just pathetic, this drunken guy crying about all his suffering, all his cliché regrets’” (82). That’s all Jason can take: “I flicked the needle handle up, interrupting the song, and snatched the album cover out of his hand” (82). Gage has just failed a crucial litmus test of friendship. How can you not hear how great this music is? The echoes of Caroline’s debate with Berry over “Good Vibrations” is unmistakable.

More than anything, it reminds me of the scene from Chronicles where Dylan is floored by Robert Johnson but Dave Van Ronk finds him derivative. So Dylan takes his record home to listen undisturbed by his friend’s egregious lapse in taste. As he recalls in Chronicles, “I let Dave go back to his newspaper, said I’d see him later and put the acetate back in the white cardboard sleeve. […] The record that didn’t grab Dave very much had left me numb, like I’d been hit by a tranquilizer bullet. Later, at my West 4th Street apartment I put the record on again and listened to it all by myself. Didn’t want to play it for anybody else” (283). It’s refreshing to be reminded that, before Dylan was a music legend, he was a superfan like Jason, like Spiotta, like us.

Eat the Document as Time Capsule

Jason discovers his mother’s secrets in the year 2000. His clues come, appropriately enough, from underground art. Watching a VH1 special on the Lost Love Movie [fictional] about Arthur Lee of the band Love [real], Jason sees a photo of Lee with a young woman he is certain is his mother. Following up his hunch, he does some online sleuthing and learns that the Lost Love Movie was shot by experimental filmmaker Bobby Desoto. Jason acquires copies of Desoto’s three extant films, sees footage of his mother, and learns from the credits that her name is Mary Whittaker. From there all it takes is a simple internet search to reveal his mother’s involvement in the bombing and subsequent fugitive status as a wanted outlaw.

In the midst of these revelations, Spiotta inserts her one and only direct reference to the book’s Dylan-derived title: “I went to the site most likely to sell copies of the film: www.undergroundmedia.com, where a year earlier I had in fact purchased a very distant-generation bootleg DVD copy of Eat the Document (the notorious never-released documentary about Dylan’s ’66 gone-electric tour)” (247-48).

The whole novel is named after this underground film, and yet that’s all Spiotta has to say about it. She simply drops that stone in the water and lets the ripples fan out without explication. Let the reader work for it. I have further thoughts on the relation of the film to the novel, but first let me wrap up some key plot points.

Jason confronts his mother. He is angry that she has lied to him all these years, though he grudgingly credits her with having the courage of her convictions in her political activism, even if it all went catastrophically wrong. Jason also pieces together Bobby Desoto’s alias as Nash Davis, and he gives his mother her old boyfriend’s contact information. Louise and Nash—or Mary and Bobby—meet again for the first time since the bombing. They apologize and forgive each other, acknowledging their mutual responsibilities and admitting that they’re done hiding. Mary plans to turn herself in to the authorities. Bobby refuses to do the policework for them, but he accepts the inevitability of his pending capture.

In the penultimate chapter of Eat the Document, Spiotta takes us back to the bombing. Mary was the one who actually planted the explosive, smuggling it in her purse, asking to use the restroom, planting the bomb under the sink, and activating the device before she left. Spiotta’s loaded language emphasizes the pressing weight of time:

A clock face, some wires and a mound of molded plastic no bigger than two fists.

She looked at her watch.

She put her hand in the purse and held the clock face steady.

She pulled the pin up until it clicked.

She listened for the faint ticking.

She inhaled.

She let go. (287)

From the moment she let go of the pin on that timer, her life was never the same. The bomb exploded in 1972, literally killing a housekeeper and effectively killing the person formerly known as Mary Whittaker. Ever since she went on the run, another clock has been ticking down, counting down the years until her new life detonated. In 2000 her time was up.

Spiotta gives Jason the final word. His last journal entry involves a different kind of letting go: he lets go of the Beach Boys.

I still admire them, appreciate them, but it is almost purely intellectual now. I don’t have the deep-felt desire to listen over and over. I honestly never thought the day would really come. And although it is sad, it is also kind of a relief, a liberation. As more time goes by, I discover other things to fill that now vacated space. Or perhaps I found the other things first and that’s what pushed the Beach Boys slowly to the perimeter. (288)

Perhaps you’ve had this same experience, with Dylan or some other all-important artist, as you transitioned from unquenchable thirst to stone-cold sobriety. Though I’ve been a Dylan fan for a long time, my superfandom has only lasted for the past decade or so. I had other comparable obsessions before—literary ones for Samuel Beckett, then Don DeLillo. The up and down trajectories of those previous passions make me pretty confident that I’ll eventually fall out of love with Dylan and promiscuously move on to some other future obsession. I do sometimes wonder what the impact will be after Dylan is no longer around, touring and producing new work. As Jason candidly admits, “maybe it is as simple as I wore out the old material and I ran out of new material to listen to (it is—after all and despite all the bootlegs—ultimately a finite set of work)” (289).

But falling out of love doesn’t rule out the possibility of falling back into love. At the end of this final chapter, Jason imagines some future day when he will return to the Beach Boys:

I will listen to this music and I will remember exactly what it was like to be me now, or me a year ago, at fifteen, totally inhabited by this work, in this very specific place and time. My Beach Boys records sit there, an aural time capsule wired directly to my soul. Something in that music will recall not just what happened but all of what I felt, all of what I longed for, all of who I used to be. And that will be something, don’t you think? (289-90)

“An aural time capsule wired directly to my soul”—what a great image! Jason never sounds more like Mary’s son than when he espouses this faith in the power of music to defy the ravages of time and preserve something pure and lasting.

Does Spiotta share that faith? Well, she’s awfully good at depicting the consciousness of characters who do. But we shouldn’t overlook other passages where she challenges such idealism. Remember that Caroline espoused similar beliefs at the beginning of the “Temporary Like Achilles” chapter—when the Beach Boys seemingly kept her innocent youth alive, preserved in amber by “Good Vibrations”—only to have those fantasies ripped away by the end of the chapter, when she adopted a different belief in wiping the past clean and starting over. It’s complicated.

There is a running tension throughout the novel between preserving the past in stable form versus destroying the past through periodic gestures of radical reinvention. It’s not about right or wrong, but rather back and forth. Art is a major battleground where these perpetual conflicts are waged, and Dylan features as a recurring combatant in this endless aesthetic/existential/metaphysical struggle. We might even (temporarily) think of him as Spiotta’s Achilles.

I think this recurring struggle lies behind her decision to title the book Eat the Document. Imagine Dylan after the motorcycle accident, off the road and away from the chaos, removed from the throbbing heart of the culture and relocated to his domestic sanctuary. Dylan the voluntary exile, Dylan the country husband and father. He got out and started over . . . and yet he continued to pore over footage of the previous life he had abruptly abandoned, and the previous self he had blown to smithereens.

What a bizarre, disorienting experience that must have been. No wonder he could never complete it. He called it Eat the Document, but maybe the document ate him.

I bet Spiotta factored in the impact that this title would have for prospective readers. I’m thinking especially about the subset of readers who lived through those tumultuous times when Dylan was the oracle of his generation, when the Weather Underground declared war on the U.S. government and its corporate enablers, and when some of the best popular music ever made was produced with astounding regularity. The book itself is a kind of time capsule. You see the title, you get the Dylan reference, you pick it up, you begin to read. It takes you back. But look out, kids! The past might not be as hospitable and innocent as you remember.

Spiotta wires a time bomb to her time capsule.

Works Cited

The Beach Boys. “Caroline, No.” Pet Sounds. Capitol, 1966.

Dore, Florence, ed. “Precious Resource (Rock and Our Generation of Novelists): An Interview with Jonathan Lethem and Dana Spiotta.” The Ink in the Grooves: Conversations on Literature and Rock ’n’ Roll. Cornell University Press, 2022.

Dylan, Bob. Chronicles, Volume One. Simon & Schuster, 2004.

---. Official Lyrics. The Official Website of Bob Dylan.

https://www.bobdylan.com/.

Johnson, Liza. “An Interview with Dana Spiotta.” The Believer (1 November 2006), https://www.thebeliever.net/an-interview-with-dana-spiotta/.

Spiotta, Dana. Eat the Document. Scribner, 2006.