If you are a regular reader of Shadow Chasing, then it goes without saying that you love Chronicles. It’s one of the most interesting artworks Dylan has ever created, and I’ve already written a lot about it. If you’re interested, you can look up my article in The Dylan Review, or check out my chapter in the upcoming book Teaching Bob Dylan edited by Barry Faulk and Brady Harrison. But I still keep returning to it and finding new gifts to unwrap.

For instance, I’ve never really explored Dylan’s odd encounter with the wrestler Gorgeous George in 1958. My recent deep-dive into gender performance in Dylan, and my attempt to reconstruct a genealogy of influences that led him to resist and revise the ideals of masculinity instilled in his youth, have inspired me to take a closer look at this scene. Why did it make such a big impact on teenager Bobby Zimmerman? Why did it continue to leave a lasting impression on the mature artist Bob Dylan? And even if, as is sometimes the case in Chronicles, Dylan embellished or invented the scene, what point was he trying to make, what function does it serve in his portrait of the artist as a young man?

Connections and Credentials

In the previous installment of this series, I focused on Dylan’s sense of exclusion from the All-American club of the Nelsons and the Seegers because of his Jewishness. This experience led him to identify with others who were stigmatized and marginalized. Instead of trying to fit in with the privileged elite, Bobby Zimmerman learned to follow a different path, seek his community elsewhere, find a new family and home.

Dylan sets up his fateful encounter with the famous wrestler by once again emphasizing his frustration with being excluded. As a kid, he dreamt of going to West Point and fighting in glorious battles. When he shared this aspiration with his father, Abe said man you must be puttin’ me on. He reminded his son that “my name didn’t begin with a ‘De’ or a ‘Von’ and that you needed connections and proper credentials to get in there” (42). Translation: sorry, son, but West Point isn’t for Zimmermans.

The unfairness of this realization disturbed the kid: “it was the connections and credentials thing that rattled me. I didn’t like the sound of it, made me feel deprived of something. It wasn’t long before I discovered what they were and how these things can sometimes interfere with your plans” (42).

His education on the importance of connections and credentials came when trying to book gigs. There were always places in Hibbing and surrounding towns to perform if one was willing to play for free. Paying gigs were harder to find, however, and young Bobby struggled to gain access: “When I put together my early bands, usually some other singer who was short of one would take it away. It seemed like this happened every time one of my bands was fully formed. I couldn’t understand how this was possible, seeing that these guys weren’t any better at singing or playing than I was. What they did have was an open door to gigs where there was real money” (42). His trouble wasn’t a lack of talent but a lack of opportunity:

Truth was, that the guys who took my bands away had family connections to someone up the ladder in the chamber of commerce or town council or merchants associations. These groups were connected to different committees throughout the counties. The family connection thing made a strong impression, left me feeling naked. It went to the very root of things, gave unfair advantage to some and left others squeezed out. How could somebody ever reach the world this way? (43)

He would need a different strategy to continue pursuing his dream of becoming an artist and sharing his music with large (paying) audiences.

Bobby Zimmerman was demoralized but determined. He just needed some encouragement and guidance. “There was a lot of halting and waiting, little acknowledgement, little affirmation, but sometimes all it takes is a wink or a nod from some unexpected place to vary the tedium of a baffling experience” (43). This is the point in a mythic quest when the hero receives timely help from a mentor. Enter Gorgeous George.

Gorgeous George

I had heard of Gorgeous George, but, until I began researching this piece, I didn’t know much about him. Before bringing him out on stage for his moment in the Chronicles spotlight, let’s fill in some context so we can appreciate what Bobby Zimmerman saw when he locked eyes with the wrestler that night in 1958.

Most of my information comes from John Capouya’s engaging biography, with a subtitle worthy of his subject’s grandiosity: Gorgeous George: The Outrageous Bad-Boy Wrestler Who Created American Pop Culture.

Capouya paints a vivid portrait of George Wagner’s character Gorgeous George, simultaneously the most popular and most vilified wrestler of the forties and fifties:

Gorgeous George in all his vainglory remains a bizarre sight. The combination of those feminine robes and ornate hairdo with his masculine features […] is confounding and, perhaps because of that, strangely compelling. Not to mention hilarious. Back in the 1940s, however, for any man, let alone an athlete, to willingly present himself as a loud, perfumed dandy crossbred with a dowager, and a sissified coward to boot, was stranger still; nearly unthinkable. To Americans of that era, George and his Gorgeous ways were truly outrageous—just the reaction the wrestler wanted. (3)

Capouya acknowledges that gender transgression was central to Gorgeous George’s persona. The wrestler trampled across the predominant masculine ideals of post-WWII America: “Most American men in the postwar era hewed considerably closer to the ethos of machismo. In America’s idea of itself and the images entertainment provided […] this was a nation of conquering tough guys who’d fought and died in a just cause. If there were other ways of being a man, Americans didn’t seem to want to know about them” (223).

Flying in the face of these gender expectations, Gorgeous George offered a queer alternative: “Just as daring in his day, the gussied-up Human Orchid was also one of the first male celebrities to flaunt a sexually ambiguous, quasi-effeminate, vaguely gay persona, and to profit nicely from it” (8).

Gorgeous George played the part of villain in the melodrama of wrestling entertainment, and he played it fabulously. Audiences loved to hate him. He was the biggest draw in the sport, and his unconventional gender performances made him rich and famous.

Capouya argues that a big part of the wrestler’s appeal was the vicarious thrill he gave crowds by doing what they dared not: openly defying the rigid gender codes of the era. “In his business any strong reaction was a good one; homophobia was just another form of heat. Yet, amid the indignation the crowds worked themselves into over George’s taboo behavior, they admired his daring, too. A few onlookers may have been truly angry, but wider swaths of the postwar audiences enjoyed being startled by George in his certain, special ways” (224).

Gorgeous George also left a lasting impression on a variety of athletes, performers, and artists who admired and emulated his transgressive performances, prompting Capouya to hail him as “a forgotten father of our popular culture” (7). Muhammad Ali frequently credited Gorgeous George as inspiration for his showmanship, boasting about his beauty and greatness as effective forms of self-promotion.

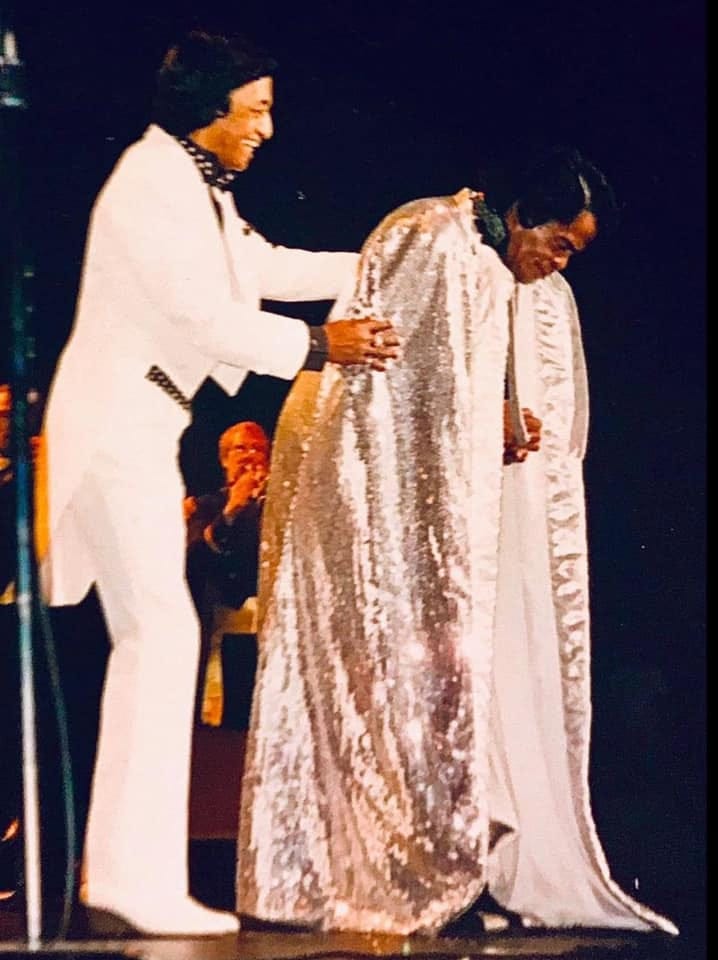

James Brown, the Godfather of Soul, took inspiration from Gorgeous George’s flamboyant wardrobe: “The capes I wear? That came from the rassler, Gorgeous George. Seeing him on TV helped create the James Brown you see on stage” (qtd. Capouya vii).

According to Capouya, “John Waters said it was Gorgeous George’s silly, scary gender-bending that led him to create his own bizarre characters, including those played by Divine, the wrestler-size cross-dresser who starred in Pink Flamingos, Female Trouble, and Hairspray” (8).

And then there is the influence on Bob Dylan.

“You’re making it come alive”

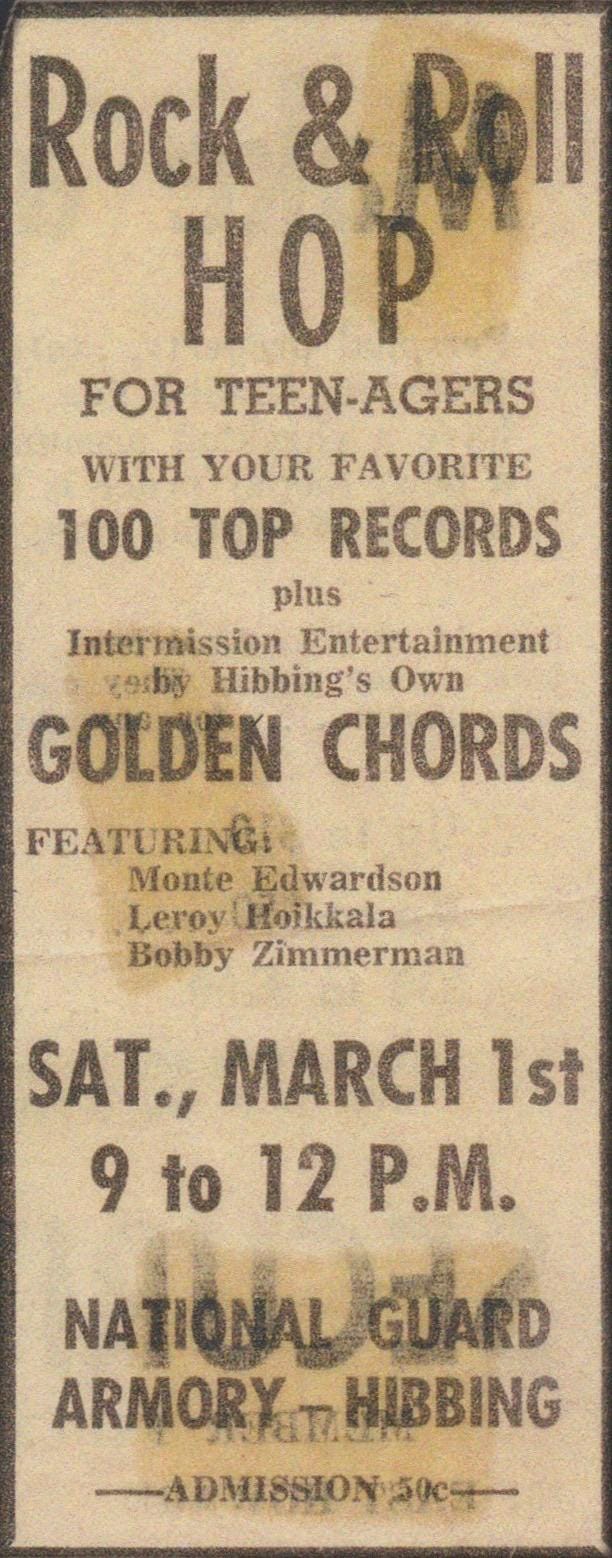

Dylan claims he received a pivotal piece of encouragement from Gorgeous George. “I was performing in the lobby of the National Guard Armory, the Veterans Memorial Building, the site where all the big shows happened—the livestock shows and hockey games, circuses and boxing shows, traveling preacher revivals, country-and-western jamborees” (43).

Dylan captures the startling effect of seeing Gorgeous George and his entourage suddenly appear in the audience:

I was playing on a makeshift platform in the lobby of the building with the usual wild activity of people milling about, and no one was paying much attention. Suddenly, the door burst open and in came Gorgeous George himself. He roared in like the storm, didn’t go through the backstage area, he came right through the lobby of the building and he seemed like forty men. It was Gorgeous George, in all his magnificent glory with all the lightning and vitality you’d expect. He had valets and was surrounded by women carrying roses, wore a majestic fur-lined gold cape and his long blond curls were flowing. (44)

“Suddenly” is one of Dylan’s favorite words in Chronicles. Again and again, the scenes he highlights are portrayed like religious epiphanies: bolts from the blue that abruptly alter the course of his life forever.

To hear Dylan tell it, you’d think the young hero had been blessed with divine intervention from flashing-eyed Athena herself:

He brushed by the makeshift stage and glanced towards the sound of the music. He didn’t break stride, but he looked at me, eyes flashing with moonshine. He winked and seemed to mouth the phrase, “You’re making it come alive.” (44)

You’re making it come alive.

Dylan admits that he may have imagined this message. But its impact on him was real, positive, and lasting nonetheless. “Whether he really said it or not, it didn’t matter. It’s what I thought I heard him say that mattered, and I never forgot it. It was all the recognition that comes when you’re doing the thing for the thing’s sake and you’re on to something—it’s just that nobody recognizes it yet. Gorgeous George. A mighty spirit” (44).

You’re making it come alive—what can that mean? You’re making the music come alive? You’re making this room come alive? You’re birthing a new self into existence, like Athena springing fully formed from the head of Zeus? Or maybe the tone is less Obi Wan Kenobi and more Mae West: “You’re making it come alive” as in “You’re turning me on! Why don’t you come up and see me some time? Is that a harmonica in your pocket or are you just glad to see me?” Maybe the “it” Bobby made “come alive” was curious George’s “poor little fool”?

The parallels with Dylan’s famous Buddy Holly story are unmistakable. These are twin pillars in his self-mythology, the origin story of how Bobby Zimmerman transfigured into Bob Dylan.

In 1958, the Hibbing teen was playing on stage and looked out into the audience. He received an unexpected, unlikely, inscrutable, transformative signal from a larger-than-life figure in the crowd, jolting him like a lightning strike and pointing the way toward his destiny.

In 1959, he experienced another epiphany, this time from the other side of the stage as an audience member. Gazing up at Buddy Holly performing in Duluth, the place of his birth, Bobby Zimmerman received a wordless transmission from the musician:

Something about him seemed permanent, and he filled me with conviction. Then, out of the blue, the most uncanny thing happened. He looked me right straight dead in the eye, and he transmitted something. Something I didn’t know what. And it gave me the chills. (Nobel Lecture)

This mystical experience with Buddy Holly validated and completed the message he received the previous year from Gorgeous George. It was the end of Holly’s journey and the beginning of Dylan’s quest:

I think it was a day or two after that that his plane went down. And somebody—somebody I’d never seen before—handed me a Leadbelly record with the song ‘Cottonfields’ on it. And that record changed my life right then and there. Transported me into a world I’d never known. It was like an explosion went off. Like I’d been walking in darkness and all of the sudden the darkness was illuminated. It was like somebody laid hands on me. (Nobel Lecture)

As a musician, it makes sense within the logic of self-mythology that Dylan should receive an oracle from the great singer and songwriter Buddy Holly. But why would a professional wrestler feature so prominently in his transfiguration? The connecting link between these influential mentors is performance, both musical and gendered, and the bond forged through performance between the performer and the audience.

Burlesque

One of the most interesting things I learned about Gorgeous George from John Capouya’s biography is that the wrestler was influenced by burlesque and drag performers from the so-called “Pansy Craze” in 1930s New York.

At the drag balls gay men, stunningly transformed into the most exotic and outrageous women, would parade down a central runway. A panel of judges would declare one of them the most fabulous, the queen of the drag. Each contestant would take on a distinct and complete persona […] and a new identity. Just like George and the boys in their ring characters, the draggers reinvented themselves, and then performed with high drama. (Capouya 230)

The influence of drag and burlesque is more obvious in Gorgeous George than in Bob Dylan, who has never been as ostentatious with his gender performance as, say, David Bowie or Boy George. That said, on multiple occasions, Dylan himself has compared his performances to more risqué art forms. In 1997, he told David Gates: “I don’t think of myself in the high falutin’ area. I’m in the burlesque area” (1196). That same year at a London press conference, he observed: “Performing’s all the same. When you’re up on stage, and you’re looking at a crowd and you see them looking back at you, you can’t help but feel like you’re in a burlesque show” (1201).

By the time he mentioned burlesque again, at the 2001 Rome press conference, he laid emphasis less on objectification/exploitation, and more on the thrill one gives and receives from the audience: “The stage is the only place where I’m happy. It’s the only place you can be what you want to be. When you’re up there and you look at the audience and they look back then you have the feeling of being in a burlesque. But there’s a certain part of you that becomes addicted to a live performance” (1259).

As with his transformative epiphanies involving Gorgeous George and Buddy Holly, I think Dylan’s attraction to burlesque tells us something important about how he conceives of performance and the symbiotic relationship between the performer and the audience.

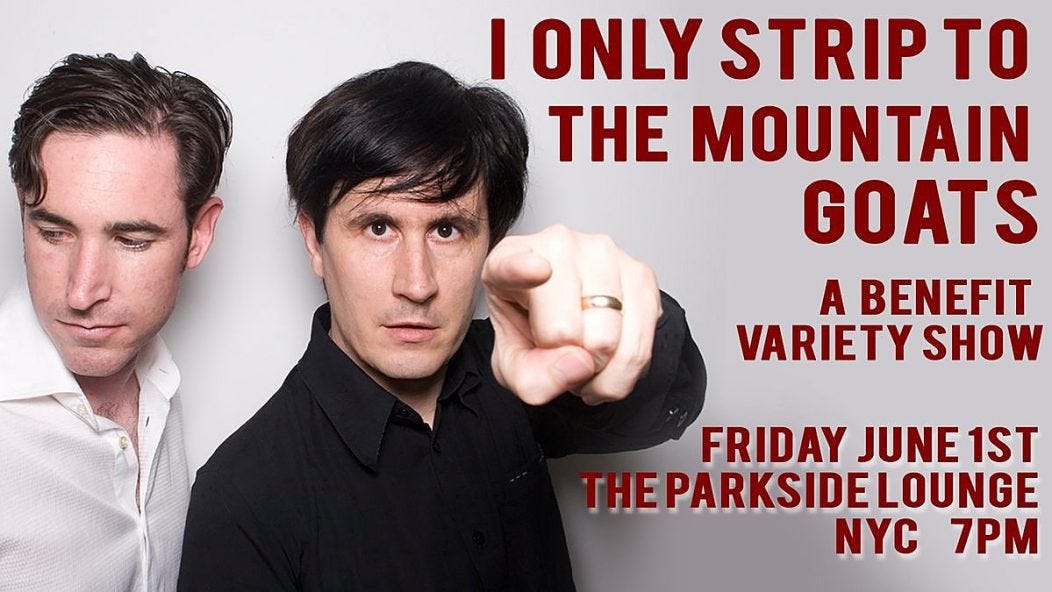

Let me make this link more explicit with an instructive analogy. The Mountain Goats are one of my favorite bands.

I don’t listen to many podcasts outside of Dylan world, but I love I Only Listen to the Mountain Goats. This show is built around a series of fascinating conversations between John Darnielle, the frontman for the band, and Joseph Fink, best known for the podcast Welcome to Night Vale. Most episodes focus on a single song by the Mountain Goats, but they occasionally bring in special guests. In episode 209, the duo talks with burlesque performers Anja Keister (say that name out loud and smile) and Iris Explosion.

Anja produced multiple revues called I Only Strip to the Mountain Goats, and Iris performed in the inaugural show.

There’s an interesting exchange midway through the episode comparing live musical performance with burlesque. John reflects upon his approach in concert:

I think a lot about how performance isn’t for the performer, it’s for the audience. And that is liberating. I feel I get more and more out of performance by investing in that proposition. I’m not there to have fun. I’m there to do a thing. I have to be totally present for it to make the thing I do happen. But my focus is on give, not on receive. I’ve discovered over the years that the more I’m able to give without thinking of getting anything out of it, the richer the payback is at the end of the night.

Anja appreciates John’s point but also pushes back against it with respect to burlesque. She responds,

That’s interesting. I think that is a really great viewpoint, but I don’t know if that necessarily translates to burlesque all the time. Burlesque is such a baring of yourself that you can’t give it all to the audience because it becomes almost a co-dependent relationship.

Iris agrees: “It’s a tease. It’s a ‘strip tease.’ You have to withhold something, otherwise you have nothing to tease.” She adds, “It’s very interactive. There’s no fourth wall in burlesque. You are with the audience, and they are with you. You are not doing something at them, you are doing something with them.”

Joseph chimes in and mediates between the two positions: “My theory is that, no matter what it is, the best live stuff is stuff where it doesn’t feel like you’re watching something. It feels like you are a group of people all in a room experiencing something together. It’s less of a performance and more of an event that you all go through.”

Doesn’t that sound like your best experiences of seeing Dylan live in concert?

When Dylan compares his work to burlesque, I think this is primarily the dynamic he has in mind. It has to do with the performer’s intimate relationship with the audience, the result of revealing some things on stage while concealing others: a strip/tease. It’s also an exercise in mutual seduction between those on stage and off. After almost sixty years as a live performer, he has become an expert at harnessing the energy—in the moment and in the room—and feeding off it.

According to Chronicles, one of his earliest lessons in this art of performance came from the mighty spirit of Gorgeous George. Dylan has been making it come alive with his own mighty spirit ever since.

Works Cited

Capouya, John. Gorgeous George: The Outrageous Bad-Boy Wrestler Who Created American Pop Culture. HarperCollins, 2008.

Dylan, Bob Chronicles, Volume One. Simon & Schuster, 2004.

---. London Press Conference, Metropolitan Hotel (4 October 1997). Every Mind Polluting Word: Assorted Bob Dylan Utterances, ed. Artur Jarosinski (Don’t Ya Tell Henry, 2006), 1197-1213.

---. “Nobel Lecture in Literature.” The Nobel Prize (4 June 2017). https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/literature/2016/dylan/lecture/.

---. Rome Press Conference, De la Ville Inter-Continental Roma Hotel (23 July 2002). Every Mind Polluting Word: Assorted Bob Dylan Utterances, ed. Artur Jarosinski (Don’t Ya Tell Henry, 2006), 1259-63.

Fink, Joseph and John Darnielle. Episode 209, with Anja Keister and Iris Explosion. I Only Listen to the Mountain Goats (July 2019). https://www.nightvalepresents.com/ionlylistentothemountaingoats.

Gates, David. “Dylan Revisited.” Newsweek (5 October 1997), https://www.newsweek.com/dylan-revisited-174056.

Great stuff as always, Graley.Your piece brings to mind the Gorgeous George moment in I’m Not There (obviously riffing on Chronicles) as well as Cate Blanchett’s performance in the movie (obviously riffing on Dylan’s “androgynous” period). Your observations on burlesque and Dylan’s performances really have me thinking. Imagine being so influenced by burlesque yet not adopting any of the overt trappings of burlesque. (Or maybe we don’t have to imagine it since we can just witness Dylan).

When you described Gorgeous George's appeal in the beginning, I immediately thought of drag culture, and how iconic villain behaviour is celebrated– it's so interesting to see a mainstream example of this, and the impact it had on so many. This essay also deals with some topics I've been thinking about for my Denmark paper. I can't wait to hear yours, because these outtakes are already so good!