In the first installment of this series, I established connections between Dylan’s early music and the values, challenges, and mystique of President John F. Kennedy. I touched upon several songs that responded to the animating issues of the era, considering how Dylan gave voice to the youthful zeitgeist of the 1960s. I also shared grief-stricken responses to the Kennedy assassination from Dylan and his musical peers. “He was America personified,” declared Peter Yarrow, “and to lose him was unthinkable” (Russo and Moses 341). Jackie Kennedy nurtured this larger-than-life image of her husband after his death, associating JFK with the Camelot myth and exalting the slain president as the fallen king of a bygone golden age.

We focused on overwhelmingly positive views of Kennedy in Part 1. Now let’s face the fact that plenty of people hated Kennedy. He barely won the 1960 presidential election, and Nixon supporters suspected electoral shenanigans in Texas and Illinois to snatch the victory. In his first year in office, he presided over the disastrous failed invasion of Cuba at the Bay of Pigs, eroding his relationship with the intelligence community and anti-Castro Cuban exiles. He prevailed in the nuclear brinksmanship of the Cuban Missile Crisis the following year, but he made powerful enemies of the U.S. military leadership who had counseled a much more forceful response. Among hardline reactionaries, Kennedy was despised for his support of civil rights reforms, and he was viewed as soft on Communism for his compromises with Khrushchev and Castro. Dylan riffs on some of these controversies in his banter with Alan Lomax after recording “Masters of War” in January 1963.

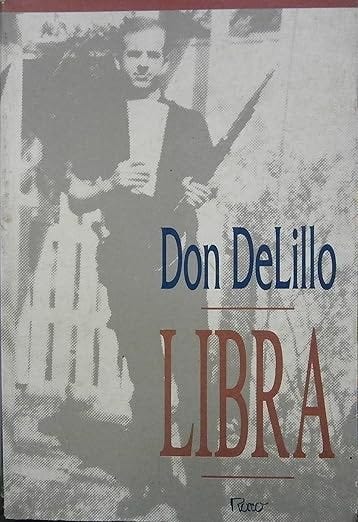

For those of us raised on the Camelot myth, it can be hard to fathom this hatred. In Libra, his novel about a conspiracy to kill the president, Don DeLillo lays bare the visceral revulsion felt by JFK’s detractors. “It’s not just Kennedy himself,” complains a character in Libra. “It’s what people see in him.”

We’re supposed to believe he’s the hero of the age. Did you ever see a man in such a hurry to be great? He thinks he can make us a different kind of society. He’s trying to engineer a shift. We’re not smart enough for him. We’re not mature, energetic, Harvard, world traveler, rich, handsome, lucky witty. Perfect white teeth. It fucking grates on me just to look at him. (DeLillo 67-68)

By the fall of 1963, JFK had become a marked man. Before his fateful trip to Dallas, he made a campaign visit to Miami on November 18. He was scheduled to have a motorcade there as well, but it was canceled after the Secret Service received a credible assassination threat. The threat came from a secretly recorded conversation on November 9 between FBI informant William Somersett and Joseph Milteer, a racist right-wing extremist in Miami. You can read the transcript from the National Archives, but it’s even more chilling to listen to the tape:

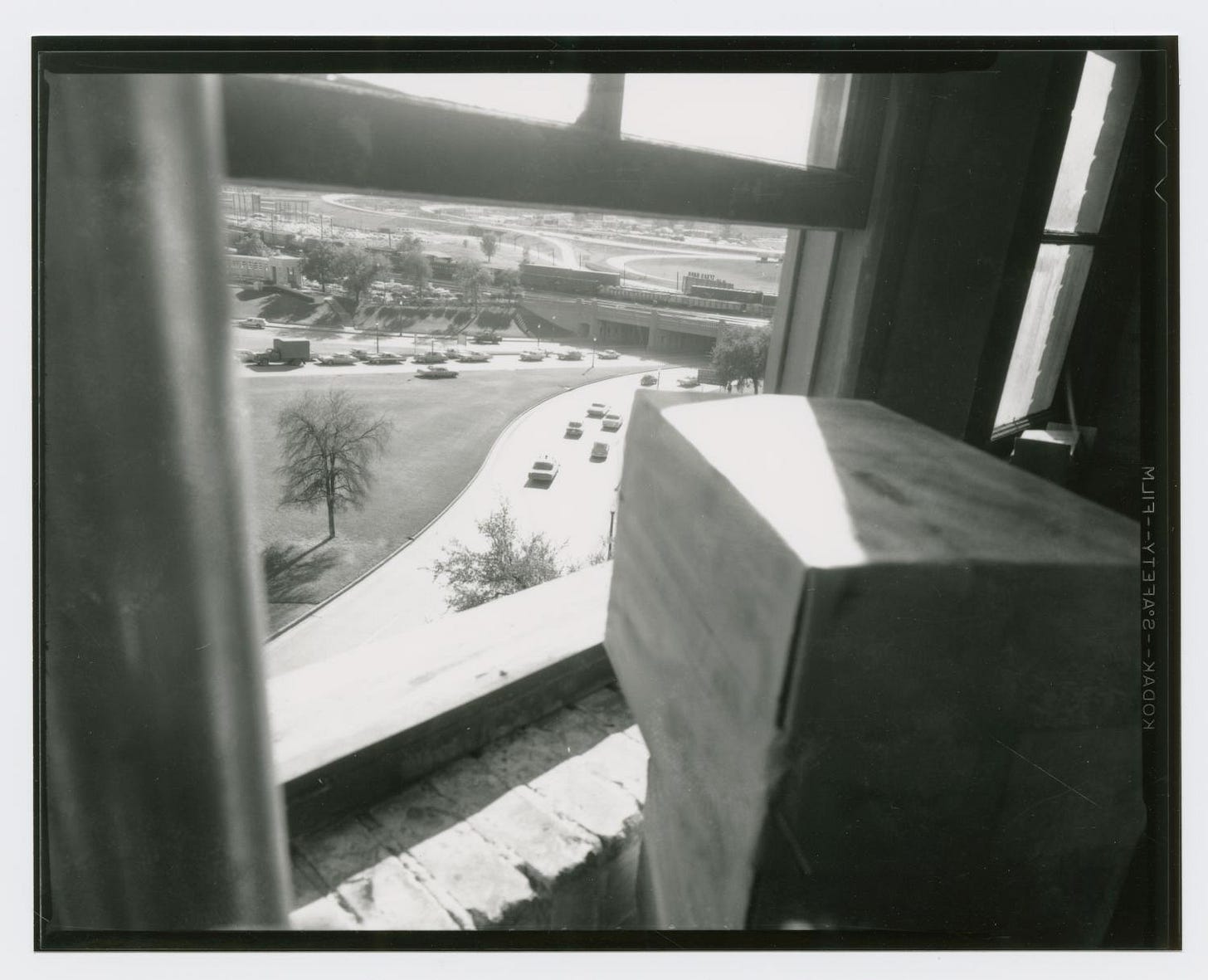

“The more bodyguards he has, the easier it is to get him,” Milteer brags. Somersett asks, “Well, how in the hell do you figure would be the best way to get him?” Milteer matter-of-factly replies, “From an office building with a high-powered rifle.” The informant point-blank asks, “They are really going to try to kill him?” Milteer confirms: “Oh, yeah, it is in the working.” Asked how he thought anyone could possibly get away with such a brazen act, Milteer calmly reassures Somersett: “They will pick somebody up within hours afterwards if anything like that would happen. Just to throw the public off.” Ominous anticipations of Dallas a fortnight later.

Meanwhile, anti-Kennedy forces in Dallas mobilized for his visit. Robert Surrey, an associate of notorious demagogue Major General Edwin Walker, blanketed the city with wanted posters:

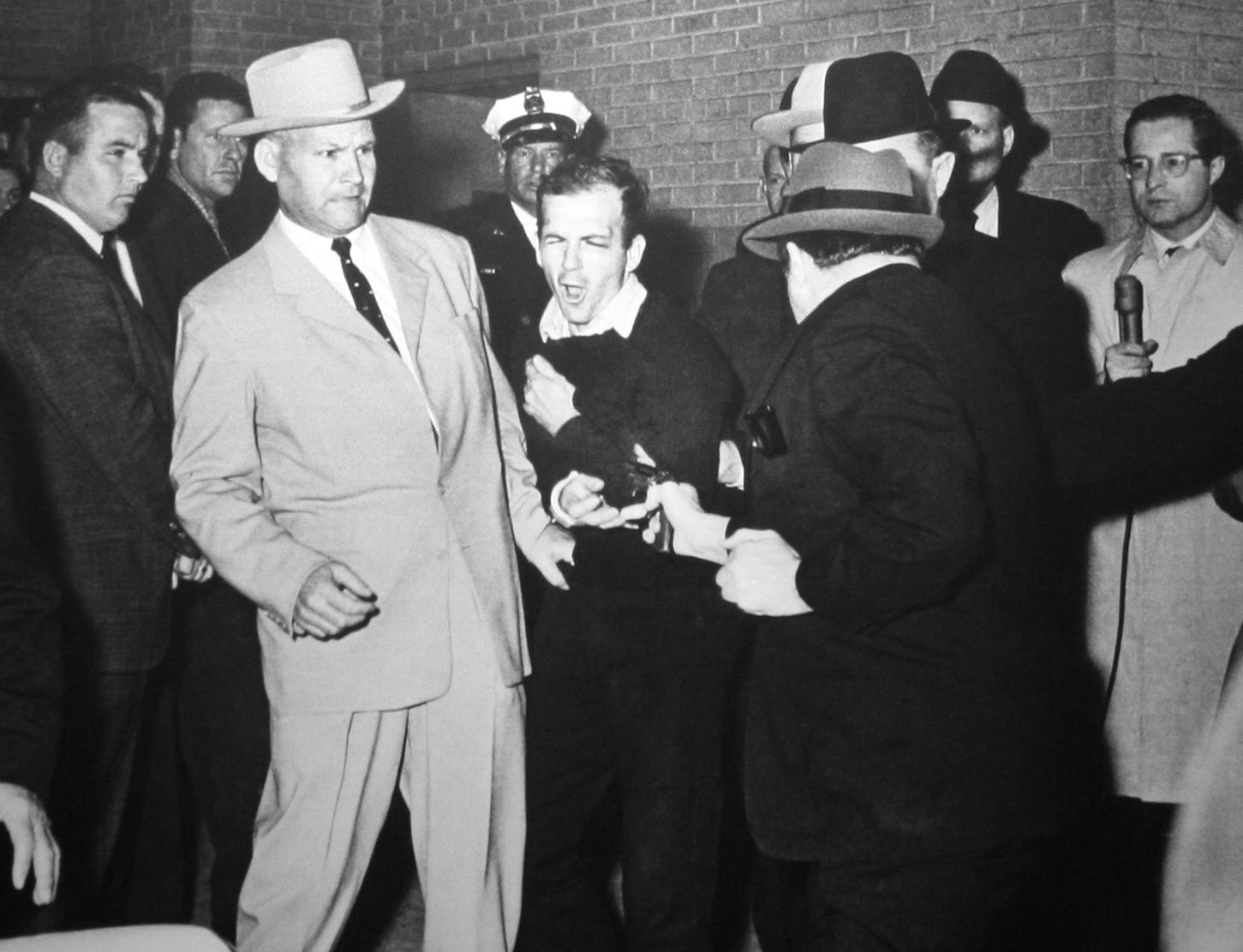

Granted, Milteer’s cocky assurances about an assassination plot may have been no more than a deranged fantasy. And the wanted poster for JFK’s treason may have been no more than inflammatory propaganda and wishful thinking. But the public execution of President Kennedy in Dealey Plaza was all too real. As Millteer predicted, a shooter was immediately arrested and charged as the lone assassin: Lee Harvey Oswald. Before he could ever stand trial for the murder, however, he was killed by Jack Ruby while in the custody of the Dallas Police Department. A stunned nation watched Ruby shoot Oswald on live television.

How did Bob Dylan react? In the first installment, we focused on his affinities for President Kennedy. But when he made his initial public comments about the assassination three weeks later, he shockingly expressed empathy instead for Oswald. Why would he do this? That’s the motivating question for this second installment.

The ECLC Debacle

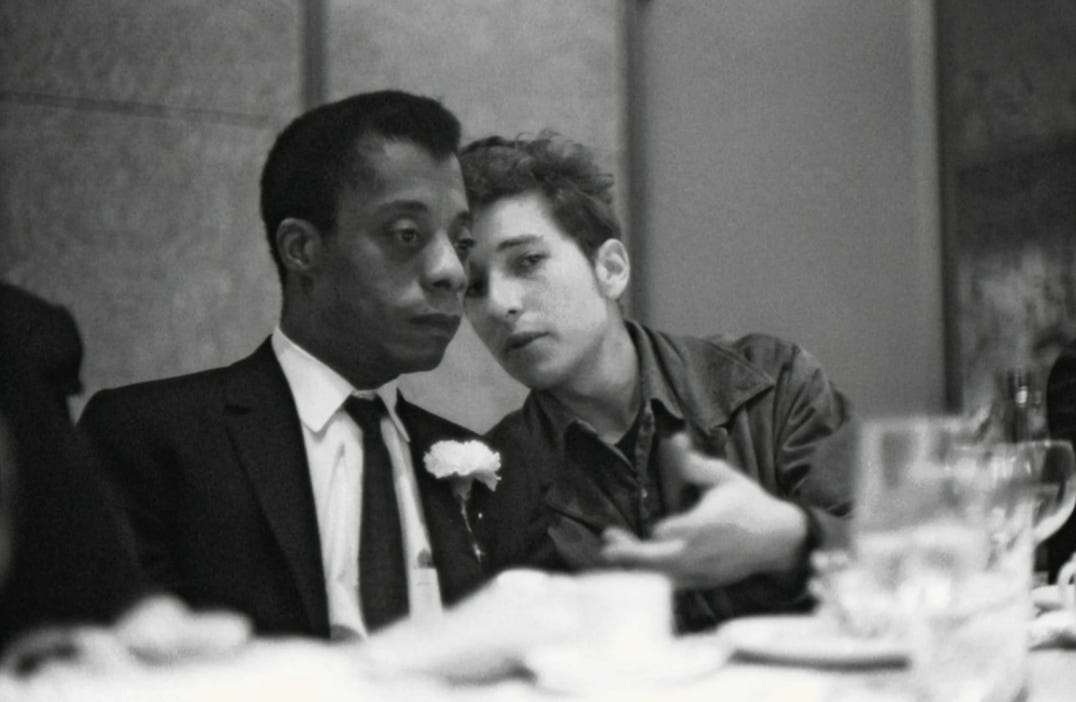

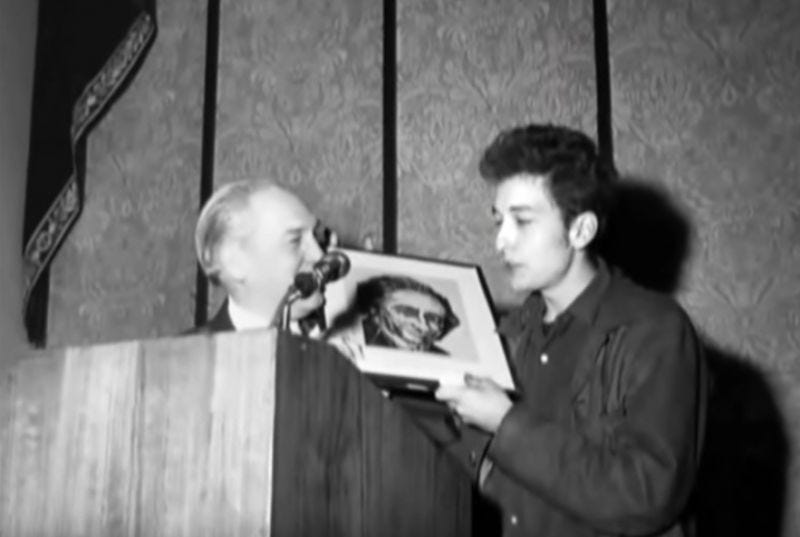

On the evening of December 13, 1963, the Emergency Civil Liberties Committee (ECLC) held its annual Bill of Rights banquet in the grand ballroom of New York City’s Americana Hotel. The celebration doubled as a fundraising dinner and awards ceremony. The previous year the ECLC had bestowed its Tom Paine Award on the philosopher Bertrand Russell, but in 1963 it chose a much younger and less conventional recipient.

Chairman Corliss Lamont explained the selection in a letter to the membership: “Bob Dylan has become the idol of the progressive youngsters today, regardless of their political factions. He is speaking to them in terms of protest that they understand and applaud.” Unfortunately, there wouldn’t be much understanding or applauding for Dylan that night after his provocative acceptance speech.

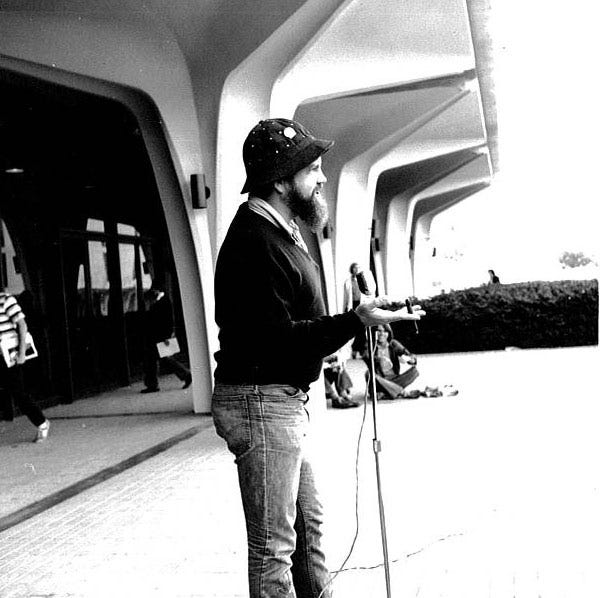

This episode is legendary in Dylan lore as an early example of his contentious relationship with audiences. He was out of his element at this formal ceremony and upset that his funky entourage wasn’t allowed into the banquet hall. He got drunk during dinner and was in a quarrelsome mood when he got up to accept the award.

After several (joking?) comments aimed at biting the hand that just fed him, he crossed the line by daring to identify with Kennedy’s alleged assassin. The disgusted crowd turned hostile and jeered him off the stage. So the story goes.

Now let’s dig down deeper. Here are the comments that got him in so much trouble:

I have to be honest, I just got to be, as I got to admit that the man who shot President Kennedy, Lee Oswald, I don’t know exactly where—what he thought he was doing, but I got to admit honestly that I too—I saw some of myself in him. I don’t think I would have gone—I don’t think I could go that far. But I got to stand up and say I saw things that he felt, in me—not to go that far and shoot. [Boos and hisses.]

You can boo but booing’s got nothing to do with it. It’s a—I just a—I’ve got to tell you, man, it’s Bill of Rights is free speech and I just want to admit that I accept this Tom Paine Award in behalf of James Forman of the Students Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and on behalf of the people who went to Cuba. [Boos and applause.]

Dylan may come across as combative, inarticulate, and tactless, but his impromptu remarks aren’t random nonsense. He situates Oswald within multiple revolutionary contexts. His blustery attitude is consistent with the generational conflict he dramatizes in “The Times They Are A-Changin’.” He identifies with young leftist radicals and expresses suspicion for old-guard liberals like those staring daggers at him that night in their fancy clothes and bald heads.

Before we consider Oswald in depth, let’s unpack those references to Cuba and SNCC. Fred Bals has written an excellent piece on the ECLC kerfuffle for his Medium site. He expands upon Dylan’s references to “the people who went down to Cuba”:

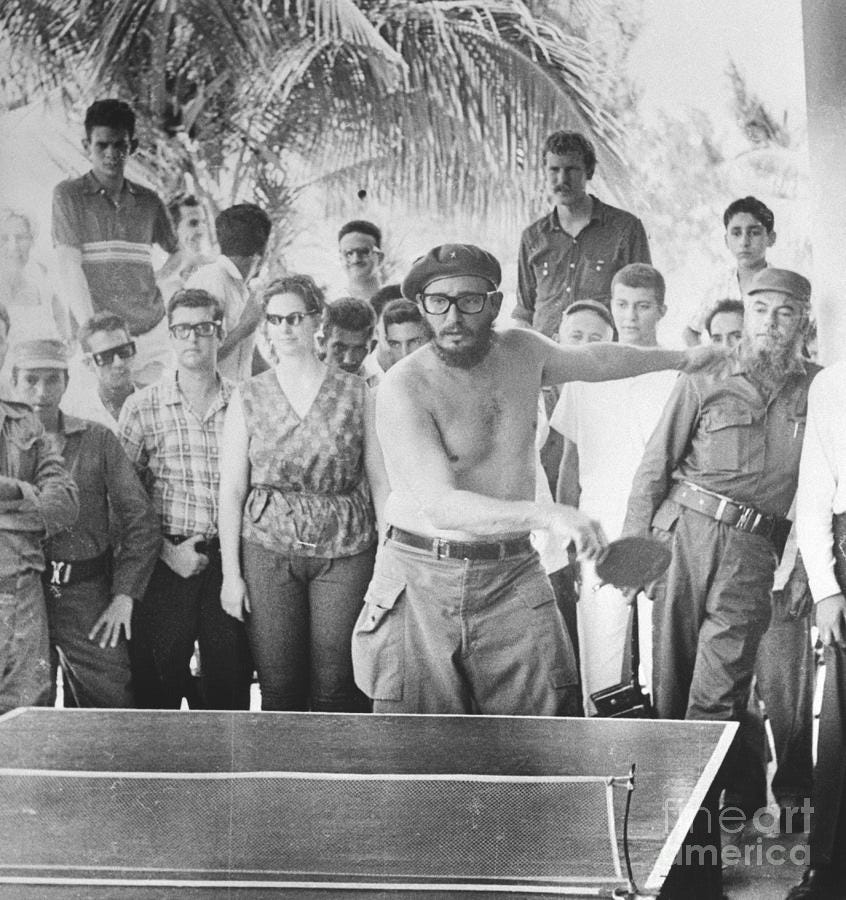

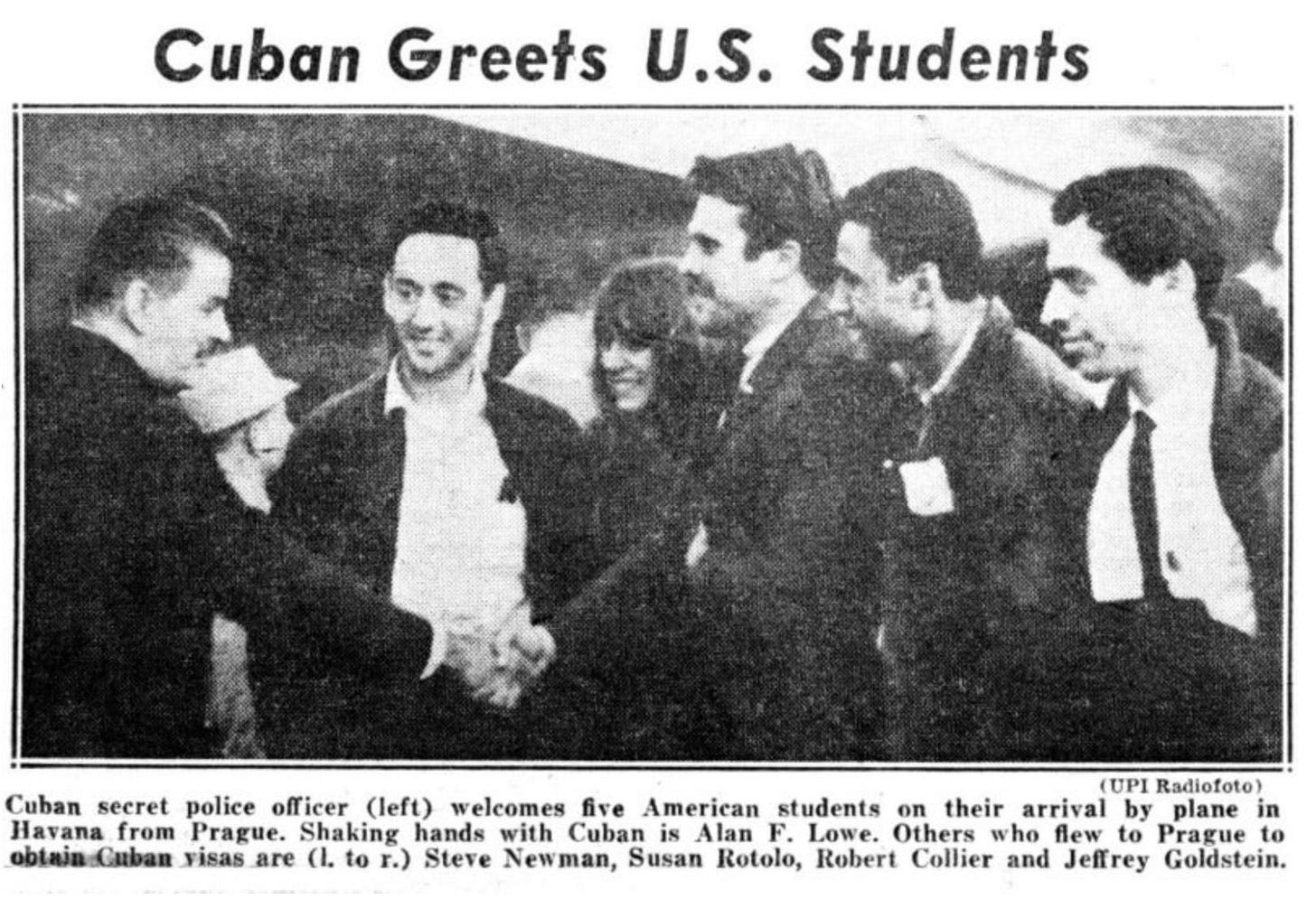

About nine months after the Cuban Missile Crisis, in June 1963, fifty-nine American students visited the island in direct defiance of the travel ban and were graced with a “surprise” visit by El Caballo, Fidel Castro himself, as they played table tennis at Varadero Beach. Perhaps Castro showing up shouldn’t have been a surprise, as the students’ all-expenses-paid trip was being funded by the Cuban Federation of Universities. On the U.S. side the trip had been organized by the Progressive Labor Movement (PLM) of New York City, a Maoist-leaning group that had split off from the Communist Party USA in the early `60s.

The leader of the PLM was Phillip Abbott Luce. Dylan mentions him by name in a clumsy portion of the speech: “So, I accept this reward—not reward, award—in behalf of Phillip Luce who led the group to Cuba, which all people should go down to Cuba. I don’t see why anybody can’t go to Cuba. I don’t see what’s going to hurt anybody’s eyes to see anything. On the other hand, Phillip is a friend of mine who went to Cuba.” To provide further context, Bals notes, “As a consequence of the Cuba trip, Luce and ten other travelers, apparently those judged the most radical, were subpoenaed to appear before the House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC) just three months before the ECLC ‘Bill of Rights’ dinner.”

Dylan also dedicates the Tom Paine Award to James Forman of SNCC. This affiliation further stamped Dylan’s credentials as a young leftist radical. Bals explains:

The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) was created in 1960 as a counterpoint to the Kennedy administration’s ham-handed attempts to co-opt southern Black student activists into the Martin Luther King “go slow” top-down leadership philosophy of attaining civil rights. In contrast, the leaders of the SNCC wanted radical, albeit nonviolent, confrontations with the white power structure, led by grassroot activists. Needless to say, another way of differentiating the SNCC from King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference or the even older school NAACP was that the former’s membership was predominately young . . . young and impatient.

Dylan’s girlfriend at the time, Suze Rotolo, was even more plugged into leftist activism than Dylan. In fact, she was largely responsible for introducing him into those circles.

In her memoir, Rotolo captures the youthful energy of the movement: “The oppressive mentality of the Cold War still held sway over the culture, and everyone working to change the status quo, whether through the arts or in politics, was chomping at the bit. To be young and on society’s edge in those years made you feel you were standing at the crossroads of something important, energized for what was to come” (220).

Kennedy is often remembered for his youthful vitality. He was only 42 years-old when he became the youngest man ever elected President of the United States. But Castro was even younger, assuming control of Cuba at the age of 32. Dylan was only 22 when he accepted the Tom Paine Award. Rotolo turned 20 two days before the assassination. Lee Harvey Oswald was only 24 when he shot President Kennedy and was gunned down himself two days later.

Rotolo, Dylan, and their friends romanticized the Cuban Revolution and viewed it through the prism of youthful rebellion:

It was very exciting to listen to these friends talk about their trip to Cuba and recount the plans Castro had for his country, now free from the dictator Batista. A revolution carried out by a ragtag bunch of rebels hiding out in the Sierra Madre mountains was appealing to American kids engaged in the upheavals of the times. Youth culture was on the rise. Young people were angry and dissatisfied with the world as it was. (Rotolo 220)

By the way, a second group of young people defied the Cuban travel ban the following year, and Suze Rotolo was one of the leaders. She devotes an entire chapter of her memoir to recounting that experience, which included touring the country and meeting Fidel Castro and Che Guevara.

Corliss Lamont was in damage-control mode after the banquet debacle. In his letter the following week to members, he stressed Dylan’s youth. He didn’t attempt to justify every squawk from the upstart crow, but he did defend the kid’s First Amendment right to say it. Indeed, the committee and its award existed largely for that purpose, as Lamont stressed:

ECLC feels that it is urgent to recognize the protest of youth today and to help make it understood by the older generation. Walt Whitman and Woody Guthrie, the culture antecedents of Bob Dylan, were not appreciated by their society until they were very old. We think that it would be better to make the effort now to comprehend what Bob Dylan is saying to and for the youth. It is true that he is not as respectable as Lord Russell, the winner of last year’s award, but neither was Tom Paine, and our history is too full of disregard for important messages which were unrespectable at the time.

Dylan felt compelled to set the record straight with an open letter to the ECLC in verse form. He emphasizes that he is not sorry for what he tried to say at the dinner:

I do not apologize for myself nor my fears

I do not apologize for any statement which led

some t believe “oh my God! I think he’s the one

that really shot the president”

I am a writer as a singer of the words I write

I am no speaker nor any politician

an my songs speak for me because I write them

in the confinement of my own mind an have t cope

with no one except my own self. I dont have t face

anyone with them until long after they’re done

no I do not apologize for being me nor any part of me

That said, he concedes that he didn’t express his thoughts very well that night, and he attempts to clarify what he meant:

when i spoke of Lee Oswald, I was speakin of the times

I was not speakin of his deed if it was his deed

the deed speaks for itself

but I am sick

so sick

at hearin “we all share the blame” for every

church bombing, gun battle, mine disaster,

poverty explosion, an president killing that comes about

For a specific example of the “we all share the blame” sentiment Dylan reacts against, consider James Reston’s front-page editorial “Why America Weeps” in The New York Times, printed the day after the assassination. It begins:

America wept tonight, not alone for its dead young president, but for itself. The grief was general, for somehow the worst in the nation had prevailed over the best. The indictment extended beyond the assassin, for something in the nation itself, some strain of madness and violence, had destroyed the highest symbol of law and order. (Semple 177)

Why did Dylan have a problem with such calls for collective guilt? He struggles to explain:

it is so easy t say “we” an bow our heads together

I must say “I” alone an bow my head alone

for it is I alone who is livin my life

I have beloved companions but they do not

eat nor sleep for me

an even they must say “I”

yes if there’s violence in the times then

there must be violence in me

I am not a perfect mute

I hear the thunder an I cant avoid hearin it

once this is straight between us, it’s then an

only then that we can say “we” an really mean

it.... an go on from there t do something about it

To claim, as Reston does, that there is “some strain of madness and violence” in the nation (“we”) isn’t good enough for Dylan. He insists on distilling that impulse down to the personal level, confronting the capacity of each individual (“I”) for madness and violence. Don’t just look at the country and bemoan how we are collectively responsible for creating the conditions that made the assassination of the president possible. Look in the mirror and see your inner Oswald.

When Dylan sat down for a New Yorker interview with Nat Hentoff in June 1964, he was still steamed about the Tom Paine Award imbroglio. He felt unnerved by the basic contradiction between the ECLC’s mission and its swanky bourgeois banquet:

Inside the ballroom, I really got uptight. I began to drink. I looked down from the platform and saw a bunch of people who had nothing to do with my kind of politics. I looked down and I got scared. They were supposed to be on my side, but I didn’t feel any connection with them. Here were these people who’d been all involved with the left in the thirties, and now they were supporting civil-rights drives. That’s groovy, but they also had minks and jewels, and it was like they were giving the money out of guilt. (Hentoff 26)

What really pissed him off, however, was how misconstrued and unfairly maligned he was for his comments about Oswald:

I had to say something about Lee Oswald. I told them I’d read a lot of his feelings in the papers, and I knew he was uptight. Said I’d been uptight, too, so I’d got a lot of his feelings. I saw a lot of myself in Oswald, I said, and I saw in him a lot of the times we’re all living in. And, you know, they started booing. They looked at me like I was an animal. They actually thought I was saying it was a good thing Kennedy had been killed. That’s how far out they are. (Hentoff 26-27)

Even though the ECLC was in the business of defending individual liberties, and even though the dinner was ostensibly a celebration of the Bill of Rights’ protection of free speech, Dylan felt muzzled at the ceremony, only free to speak his mind when expressing gratitude to his benefactors: “The chairman was kicking my leg under the table, and I told him, ‘Get out of here.’ Now, what I was supposed to be was a nice cat. I was supposed to say, ‘I appreciate your award and I’m a great singer and I’m a great believer in liberals, and you buy my records and I’ll support your cause.’ But I didn’t and so I wasn’t accepted that night” (Hentoff 27).

Dylan airs his grievances with Hentoff, but he tries to strike a more conciliatory note at the end of his verse-letter to the ECLC. He regrets hurting the group’s fundraising effort and offers to pay off his “moral debt” at any price. He closes by extending an olive branch:

I love you all up there an the ones I dont love,

it’s only because I do not know them an have not

seen them . . . God it’s so hard hatin. it’s so

tiresome . . . an after hatin something to death,

it’s never worth the bother an trouble

out! out! brief candle

life’s but an open window

an I must jump back thru it now

The fact that he sides with love over hate may have pacified some critics. But to my mind he sticks his foot in his mouth again. He invokes Macbeth’s soliloquy [“Out, out, brief candle! / Life’s but a walking shadow…” (5.1.24-25)]. So far, so good, if he’s lamenting the slain president’s short life and lighting a memorial candle. But then he turns it into joke: “life’s but an open window / an I must jump back through it now.” I guess that’s his cue to escape. Read within the context of the assassination, however, it comes across a bit too much like Oswald again, at the sixth-floor window of the Texas School Book Depository.

Oswald the Leftist

Dylan told Hentoff that the ECLC audience “had nothing to do with my kind of politics” and that he “didn’t feel any connection with them” (26) So what connection did he feel to Oswald? Let’s start back in Hibbing.

In Chronicles, Dylan describes his native region as a political hotbed: “The upper Midwest was an extremely volatile, politically active area—with the Farmer Labor Party, Social Democrats, socialists, communists. They were hard crowds to please and not too much for Republicanism” (231).

During a 2005 public discussion between Greil Marcus and Don DeLillo, Marcus shared a revealing anecdote, worth quoting at length, about the ardent socialist climate in Hibbing:

I was giving a reading in May, I guess, and a woman stood up in the audience, and she spoke with a great deal of outrage. She said, “People talk about Bob Dylan’s background as if they know something about it. But I went to Hibbing, and I was shocked by what I found.” She said, “People wonder about Bob Dylan emerging in the early sixties with these very strong and striking and visionary and poetic statements about the hell into which America was descending, as if this came out of nowhere.” And she said, “You go to Hibbing and you find poetry painted on the sides of warehouses. You find Trotskyist bars that have been there since the 1920s, where the arguments that were going on in the 1920s are still going on today.” She said, “There is an enormous socialist tradition. It is in fact in the northern part of the state of Minnesota that both the Socialist Party and the Communist Party began organizing, with a great deal of success, in the 1920s and the 1930s. They don’t have a Democratic Party in the state of Minnesota, they have the Democratic Farmer Labor Party, which was the result of a merger in the 1940s between, essentially, the Democratic Party and the Socialist Farmer Labor Party.” She said, “All of that is there in Hibbing, and no one wants to talk about it.”

While this account doesn’t mean that Bobby Zimmerman was himself a socialist, it does suggest that he breathed in the air of leftist activism long before he changed his name to Bob Dylan, found a girlfriend who worked for CORE, and made friends with young radicals like Phillip Abbott Luce and Jim Forman. It also helps explain his affinity for another scrawny white kid advocating on behalf of Communist Cuba.

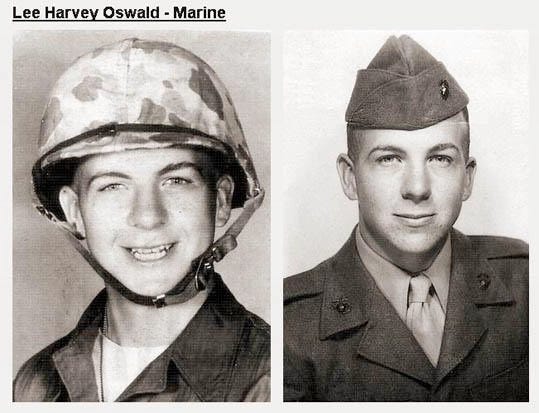

Lee Harvey Oswald grew up in a very different rebel tradition than Dylan. He and his brother Robert were both named after their father Robert Edward Lee Oswald, a distant cousin of General Robert E. Lee, the commander of Confederate forces in the Civil War. [Let this sink in: Kennedy is buried in Arlington National Cemetery, in land that was annexed from the estate of Robert E. Lee during the Civil War.]

Although he served in the Marines (1956-1959), he became so deeply disillusioned with American capitalist society that he renounced his U.S. citizenship and defected to the Soviet Union in 1959. He lived there almost three years, working in a factory in Minsk, eventually marrying and starting a family, and ultimately returning to the U.S. in 1962.

Oswald’s attraction to Marxism at a young age stemmed from his grinding poverty. He was further radicalized by the execution of the Rosenbergs as Communist spies in 1953. Peter Kihss’s first NYT profile of Oswald included a widely circulated interview conducted during his time in Moscow by journalist Aline Mosby. He explained his political beliefs to Mosby:

I’m a Marxist. I became interested about the age of 15. An old lady handed me a pamphlet about saving the Rosenbergs. I still remember that pamphlet about the Rosenbergs. I don’t know why. Then we moved to North Dakota and I discovered one book in the library, Das Kapital. It was what I’d been looking for. It was like a very religious man opening the Bible for the first time. I started to study Marxist economic theories. I could see the impoverishment of the masses before my eyes in my own mother. I thought the worker’s life could be better. I found some Marxist books on dusty shelves in the New Orleans library and continued to indoctrinate myself for five years. (qtd. Semple 42)

As Shadow Chasing readers will recall, Dylan was also outraged by the mistreatment of the Rosenbergs and wrote a song about them, “Julius and Ethel,” an outtake from Infidels.

Dylan’s leftist convictions were never as all-consuming as those of Oswald. The 22-year-old musician found a more positive, nonviolent outlet for expressing his social critiques than the 24-year-old dissident. Nevertheless, as Dylan read about Oswald’s background in the days following the assassination, he must have noticed resemblances in their political perspectives. One wonders if his recognition of those unsettling similarities played a part in Dylan’s choice to distance himself from his leftist affiliations after the Kennedy assassination.

Oswald the Outsider

At a more basic level, Dylan’s identification with Oswald had less to do with politics than with their shared status as outsiders. Peter Kihss spoke with multiple people who knew the shooting suspect. According to Allen D. Graf, who served with Oswald in the Marines, he was a “lonely, introverted, aloof boy.” According to Mrs. Howard Green, wife of a Texas State Representative, he was “an introvert” (Semple 41).

“He was a clean-cut kid / But they made a killer out of him / That’s what they did.”

Oswald’s father died two months before Lee was born. His mother Marguerite relocated the family from New Orleans to Fort Worth, then briefly to the Bronx, before returning to New Orleans. The Southern transplant was bullied by classmates in New York and stopped attending school altogether. During this period, he was held for psychiatric evaluation at Youth House. There he was interviewed by counselor Evelyn Siegel, whose findings are in the Warren Report.

Siegel characterized young Lee as a “seriously detached, withdrawn youngster,” but added that there was “a rather pleasant, appealing quality about this emotionally starved, affectionless youngster which grows as one speaks to him.” It’s a description that might be applied to any number of alienated adolescents, like the James Dean character in Rebel Without a Cause which spoke so powerfully to young Bobby Zimmerman. In one particularly revealing observation, Siegel reported that Lee “feels almost as if there is a veil between him and other people through which they cannot reach him, but he prefers this veil to remain intact.” Surely that master of masks Bob Dylan could relate.

You may be surprised to learn that Oswald had artistic aspirations. Attempting to get his honorable discharge from the Marines reinstated, he wrote a letter in 1962 to the Secretary of the Navy John Connally. Yes, the same John Connally who won election as Governor of Texas the following year and was shot by Oswald (nonfatally) in the front seat of Kennedy’s limousine. Rather than copping to his Russian excursion as a defection, Oswald described himself to Connally as an apprentice writer: “a person who had gone to the Soviet Union to reside for a short time (much in the same way E. Hemingway resided in Paris)” (qtd. Semple 268).

This analogy with Hemingway may sound disingenuous, but there could be some truth to it. Appendix 13 of the Warren Report is a biography of Lee Harvey Oswald. As the commission learned, Oswald applied to Albert Schweitzer College in Churwalden, Switzerland, in March 1959. The application form asks about vocational interests, and Oswald answered: “To be a short story writer on contemporary American life.” On that same form he lists his favorite authors as Jack London, Charles Darwin, and Norman Vincent Peale.

While in Russia, Oswald kept a handwritten journal titled the “Historic Diary.” He also wrote a manuscript called “The Collective – Life as a Russian Worker.” After his return to the United States, he hired a stenographer to work on the latter manuscript but it was never published. Among Oswald’s many disappointments, he was a frustrated author. In the end, the sword proved mightier than the pen.

Half of DeLillo’s Libra is told from Oswald’s perspective. Anthony DeCurtis asked about this controversial decision in a 1988 interview with Rolling Stone. DeLillo explained his identification with Oswald: “I think I have an idea of what it’s like to be an outsider in this society. Oswald was clearly an outsider, although he fought against his exclusion. I had a very haunting sense of what kind of life he led and what kind of person he was” (DeCurtis 59).

Conservative columnist George Will branded Libra “an act of literary vandalism and bad citizenship,” in part because DeLillo had the audacity to imagine his way into Oswald’s experience. But the novelist defended his approach in ways that resonate strongly with Dylan’s art. DeLillo told interviewer Ann Arensberg:

The writer is the person who stands outside society, independent of affiliation and independent of influence. The writer is the man or woman who automatically takes a stance against his or her government. There are so many temptations for American writers to become part of the system and part of the structure that now, more than ever, we have to resist. American writers ought to stand and live in the margins, and be more dangerous. (45-46)

When Dylan told the flabbergasted ECLC audience “I saw some of myself in him” and “I saw things that he felt, in me,” he was approaching Oswald with empathy. In Folk Music: A Bob Dylan Biography in Seven Songs, Greil Marcus asserts that empathy is the cornerstone of Dylan’s art: “‘I can see myself in others,’ Bob Dylan said in Rome in 2001, speaking to a crowd of journalists, and if there is a key to his work from now back to its start, that may be it. The engine of his songs is empathy: the desire and the ability to enter other lives, even to restage and re-enact the dramas others have played out, in search of different endings” (5).

The Kennedy assassination, combined with the ECLC debacle, seem to be the dual impetus behind one of Dylan’s greatest songs of empathy: “Chimes of Freedom.”

Clinton Heylin points out that the Margolis and Moss manuscripts contain a brief poem from late 1963 that is clearly a precursor to the song:

the colors of Friday were dull

as cathedral bells were gently burnin’

striking for the gentle

striking for the kin

striking for the crippled ones

an striking for the blind (qtd. Heylin 177)

Heylin’s interpretation is on target: “The Friday in question, in the context of the other poems surrounding it, is unquestionably November 22, the day JFK got caught in a Texas shooting gallery” (177).

By the time Dylan debuted “Chimes of Freedom” in May 1964 in London, the opening had morphed into this:

Far between the finished sundown an’ midnight’s broken toll

We ducked inside the doorway as thunder went crashing

As majestic bells of bolts struck shadows in the sounds

Seeming to be the chimes of freedom flashing

On the surface, the song is about getting caught in a thunderstorm and scampering into a cathedral alcove to stay dry. But the palette Dylan uses to paint his panorama comes from the Kennedy assassination: the thunderous crashing of gunfire, the blinding flashes of media coverage, and the funereal tolling of mourning bells.

If Dylan ever deliberately set out to write an American anthem, “Chimes of Freedom” is it. The song’s scenario—waiting out a tempestuous night, darkness punctuated by violent crashes and flashes, anxiety and uncertainty over the outcome—mirrors “The Star-Spangled Banner,” written by Francis Scott Key during the bombardment of Fort McHenry in the War of 1812. “Chimes of Freedom” also invokes one of America’s most iconic symbols of freedom: the Liberty Bell.

In his 1964 interview with Hentoff, Dylan drew a sharp distinction between his new album and his previous work:

There aren’t any finger-pointing songs in here, either. Those records I’ve already made, I’ll stand behind them; but some of that was jumping into the scene to be heard and a lot of it was because I didn’t see anybody else doing that kind of thin. Now a lot of people are doing finger-pointing songs. You know—pointing to all the things that are wrong. Me, I don’t want to write for people anymore. You know—be a spokesman. (15-16)

Another Side of Bob Dylan announces Dylan’s departure from socially-engaged topical songwriting, and “Chimes of Freedom” is his farewell address. But he doesn’t use it to point the finger of blame as he had in previous protest songs. “Chimes of Freedom” is about what he loves, not what he hates.

Dylan resigns the post of “voice of his generation,” but on his way out the window, he proclaims his enduring empathy for and solidarity with outsiders, outcasts, and outlaws. He did a fumblingly bad job of making this point in his ECLC speech. He proves much more adept at expressing himself through “Chimes of Freedom.”

Ring them bells: “Tolling for the rebel, tolling for the rake / Tolling for the luckless, the abandoned an’ forsaked / Tolling for the outcast, burnin’ constantly at stake.” Shine your light: “Flashing for the warriors whose strength is not to fight / Flashing for the refugees on the unarmed road of flight.” Dylan’s anthem is of a piece with “The New Colossus” by Emma Lazarus, spoken in the voice of Lady Liberty:

“Keep, ancient lands, your storied pomp!” cries she

With silent lips. “Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me,

I lift my lamp beside the golden door!”

“Chimes of Freedom” is no “Ballad of Lee Harvey Oswald,” but the arch-outcast’s silhouette is visible behind the song. Remember what Dylan told Hentoff: “I had to say something about Lee Oswald. I told them I’d read a lot of his feelings in the papers, and I knew he was uptight. Said I’d been uptight, too, so I’d got a lot of his feelings. I saw a lot of myself in Oswald, I said, and I saw in him a lot of the times we’re all living in” (26). In the song’s final verse, Dylan links arms with a disheveled cast of social pariahs seeking shelter from the storm. He might as well be describing a cathedral full of Oswald ghosts:

Tolling for the aching ones whose wounds cannot be nursed

For the countless confused, accused, misused, strung-out ones an’ worse

An’ for every hung-up person in the whole wide universe

An’ we gazed upon the chimes of freedom flashing

This concludes the second installment of the Shadow Chasing series on Dylan and the Kennedy assassination. I hope you have found it informative and illuminating so far, despite the very dark subject matter. We’ll plunge further into the darkness, and look for some glimmers of light, in the third and final installment on “Murder Most Foul.”

Works Cited

Arensberg, Ann. “Seven Seconds.” 1988. Rpt. in Conversations with Don DeLillo. Ed. Thomas DePietro. University Press of Mississippi, 2005, 40-46.

Bals, Fred. “Speechifyin’—Bob Dylan Meets Tom Paine at the ECLC Civil Rights Dinner.” Medium (5 May 2021), https://fredbals.medium.com/speechifyin-bob-dylan-meets-tom-paine-at-the-eclc-civil-rights-dinner-dc28313ec445.

DeCurtis, Anthony. “‘An Outsider in This Society’: An Interview with Don DeLillo.” 1988. Rpt. in Conversations with Don DeLillo. Ed. Thomas DePietro. University Press of Mississippi, 2005, 52-74.

DeLillo, Don. Libra. New York: Penguin, 1988.

Dylan, Bob. Chronicles, Volume One. Simon & Schuster, 2004.

---. “A Message from Bob Dylan to the E.C.L.C.” Corliss Lamont Website, https://www.corliss-lamont.org/dylan.htm.

---. Official Lyrics. The Official Bob Dylan Website.

https://www.bobdylan.com/.

---. “Transcript of Bob Dylan’s Remarks at the Bill of Rights Dinner at the Americana Hotel on 12/13/63.” Corliss Lamont Website, https://www.corliss-lamont.org/dylan.htm.

Hentoff, Nat. “The Crackin’, Shakin’, Breakin’ Sounds.” 1964. Rpt. in Bob Dylan: The Essential Interviews, ed. Jonathan Cott. Wenner Books, 2006, 13-28.

Heylin, Clinton. Revolution in the Air: The Songs of Bob Dylan, 1957-1973. Chicago Review Press, 2009.

Lamont, Corliss. Letter to Attendees of the ECLC Bill of Rights Dinner (19 December 1963), https://www.corliss-lamont.org/dylan.htm.

Lazarus, Emma. “The New Colossus.” Poetry Foundation, https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/46550/the-new-colossus.

Marcus, Greil. Folk Music: A Bob Dylan Biography in Seven Songs. Yale University Press, 2022.

--- and Don DeLillo. “Greil Marcus and Don DeLillo Discuss Bob Dylan and Bucky Wunderlick (2005).” Greil Marcus (17 October 2014), https://greilmarcus.net/2014/10/17/greil-marcus-and-don-delillo-discuss-bob-dylan-and-bucky-wunderlick-2005/.

Rotolo, Suze. A Freewheelin’ Time: A Memoir of Greenwich Village in the Sixties. Aurum Press, 2009.

Russo, Gus, and Harry Moses, eds. Where Were You?: America Remembers the JFK Assassination. Lyons Press, 2013.

Semple, Jr., Robert B, ed. Four Days in November: The Original Coverage of the John F. Kennedy Assassination by the Staff of The New York Times. St. Martin’s Press, 2003.

Shakespeare, William. Macbeth. Arden Shakespeare Second Series. Ed. Kenneth Muir. Bloomsbury, 1997.The Warren Commission Report. JFK Assassination Records. National Archives. https://www.archives.gov/research/jfk/warren-commission-report/toc.

Will, George F. “Shallow Look at the Mind of an Assassin.” The Washington Post (21 September 1988), https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/opinions/1988/09/22/shallow-look-at-the-mind-of-an-assassin/f8a4c3c6-8355-43c3-8a04-03d6588688e6/.

I just couldn’t stop reading… This is an amazing piece of research and insight. Fantastic!

I've actually read this part of your trilogy over a week ago, but it was late at night and I wasn't able to turn the thoughts I had into a coherent comment, so I'm revisiting these notes now.

It’s so fascinating that Dylan clarifies in his poem that he does not believe in collective guilt or collective responsibility, when he also wrote “Only A Pawn in Their Game” a song about blaming the racist structures rather than the individual shooter. Is the difference that Medgar Evers' assassination was a racially motivated hate crime? On a related note, I’m fascinated with the shift from “I see something of JFK’s killer in me” to the impersonal “they” in Murder Most Foul (especially after having just read the third part of your series). What do we make of that?

I’m sure this was intended, but I liked how your “Don’t just look at the country and bemoan how we are collectively responsible for creating the conditions that made the assassination of the president possible. Look in the mirror and see your inner Oswald.” mirrored JFK’s “Ask not what your country can do for you, ask what you can do for your country”.

The Tom Paine Award debacle has always me as such a pivotal moment in Dylan’s career, almost like the first and last time he made himself so vulnerable by explaining himself. It feels like his attitude towards public opinion of his person really shifted after that. Maybe it’s that after being confronted with a crowd without any hair on their heads, he made the conscious decision to grow younger: “I was so much older then, I’m younger than that now”.

Lastly, and I’m sure you knew this, but I just wanted to add that Dylan performed “Chimes of Freedom” during the Bill Clinton inauguration.

All three parts are excellent and insightful reads – thank you for writing them!