Dylan and the Kennedy Assassination

Part 1, Roll on John

Amid the flurry of executive orders issued by President Trump in January 2025 was a mandate for the National Archives to release all documents related to the murders of John and Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther King, Jr. On March 18, another 63,400 pages were made public. The morning after the release, New York Times cultural critic A. O. Scott published a thoughtful essay reflecting on the legacy of distrust and paranoia surrounding these assassinations. Scott makes this compelling argument:

The truth is that nothing in the archives is going to dispel the fog of hypothesis, rumor and speculation that swirls around these killings. The assassinations of the 1960s — President Kennedy’s in particular — remain the source and paradigm of modern conspiratorial thinking, a style of argument to which the current president is passionately committed. Whatever details emerge now are unlikely to settle the ongoing debates, which are less about what happened in Dallas in 1963 (or Memphis and Los Angeles five years later) than about the character of the American state and the nature of reality itself.

I agree with Scott that President Kennedy’s assassination marked a major turning point in how Americans view their government. As he puts it,

Was Kennedy killed by the Mafia? By the C.I.A.? Was he an early, liberal victim of what modern conservatism has come to call the Deep State? A lot of people think so, and there may be unanswered questions hovering around his death. But there’s a thin line between skepticism and paranoia, between reasonable guesses and wild invention. The American imagination often gravitates to the far side of that line, and the Kennedy assassination was one of the shocks that pushed us over it.

Ever since that “dark day in Dallas – November ’63 / A day that will live in infamy,” Americans have lost faith in the government to tell them the truth. This phenomenon is most pronounced on the far fringes of the political spectrum, both left and right. But even large segments of the moderate middle believe that shadowy figures and nefarious forces operate behind the scenes as the driving engine of history. A paranoid character in Libra, Don DeLillo’s riveting novel about the Kennedy assassination, puts it like this: “There’s something they aren’t telling us. Something we don’t know about. There’s more to it. There’s always more to it. This is what history consists of. It’s the sum total of all the things they aren’t telling us” (321).

Subsequent events—from the Vietnam War to Watergate, from the Iran-Contra scandal to 9/11, and most recently the proliferation of Deep State conspiracy theories involving black ops, false flag operations, and election fraud—have only deepened the fog of paranoia. As Scott puts it, “The cumulative moral of these stories was that nothing was ever what it seemed, and that American institutions were warrens of treachery and deceit.”

The fallout from the Kennedy assassination isn’t merely political, it is existential. According to Scott, “It isn’t just that we disagree on the facts or what they mean; we lack a common definition of what a fact even is. Generalized mistrust of authority and expertise turns us into epistemological free agents, making up the world as we blunder through it. We’re just asking questions, doing our own search engine-optimized investigations, huddling in ad hoc Warren Commissions of our own devising.”

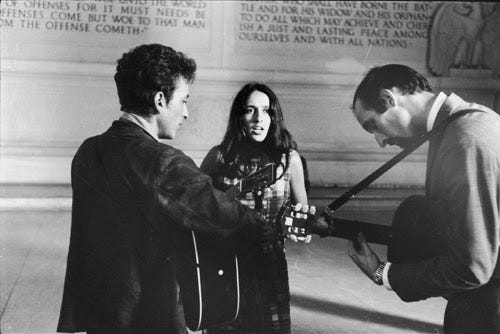

These are huge, thorny, fundamental issues—and Bob Dylan is right in the middle of it all. He emerged as a professional musician at the beginning of Kennedy’s presidency. JFK was inaugurated on January 20, 1961, and Dylan arrived in Greenwich Village just four days later. Dylan earned a reputation as the “voice of his generation” by writing and playing songs that commented on headline events of the era and took moral stands on civil rights, war, greed, political and judicial corruption. As different as they were in background, voice, appearance, and stature, Kennedy and Dylan shared a number of bedrock values. They spoke directly to young Americans in particular, challenging and inspiring them to make the country, the world, and the future better.

As Kennedy famously put it in his inaugural address, “And so, my fellow Americans, ask not what your country can do for you—ask what you can do for your country.” Or as Dylan put it, less famously but just as earnestly, at the end of his first protest song, “The Death of Emmett Till”: “But if all of us folks that thinks alike, if we gave all we could give / We could make this great land of ours a greater place to live.”

It all came crashing down on November 22, 1963, in Dallas, “the place where Faith, Hope and Charity died,” as Dylan later put it in “Murder Most Foul.” The young singer was deeply affected by the Kennedy assassination, but his views and allegiances had also become more complicated by then. He made his first public remarks about the Kennedy assassination in December 1963 during his acceptance speech for the Tom Paine Award. He had the gall to say he identified in certain respects with shooter Lee Harvey Oswald, and the appalled audience at the Emergency Civil Liberties Committee (ECLC) banquet booed him off the stage. As we’ll see in Part 2, however, there was more to that story than the drunken ramblings of a nervous beatnik.

Kennedy’s life and death have continued to impact Dylan in profound ways. His most direct confrontation with the Kennedy assassination came nearly six decades after the fact, when he released “Murder Most Foul” in March 2020, in the midst of a global pandemic and the tumultuous presidency of the conspiracy-obsessed Donald Trump. The song shows that the wounds inflicted in Dealey Plaza still haven’t healed, and they have left an indelible mark on Bob Dylan’s art.

I want to study that legacy with readers of Shadow Chasing in a three-part series on Dylan and the Kennedy assassination. This first piece will focus on views of Kennedy in the context of the sixties. The second will center upon the ECLC fallout and Dylan’s uneasy identification with Oswald. The final installment will be a deep-dive on “Murder Most Foul.”

Dylan on Kennedy

As important as the president became for the musician, it’s odd that Dylan’s first overt reference to Kennedy in a song was totally trivial, basically an elaborate dick joke. In “I Shall Be Free” from The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan, he delivers this groaner:

Well, my telephone rang it would not stop

It’s President Kennedy callin’ me up

He said, “My friend, Bob, what do we need to make the country grow?”

I said, “My friend, John, Brigitte Bardot

Anita Ekberg

Sophia Loren

Country’ll grow!

This silly song is forgettable, but the album also contains more serious and memorable songs about the challenges confronting the country and the new presidential administration.

For instance, “Oxford Town” addresses James Meredith’s integration of the University of Mississippi in 1962, a move resisted by Governor Ross Barnett and only made possible when President Kennedy called in federal marshals to enforce the law. “Masters of War” is arguably Dylan’s angriest protest song. It’s a diatribe against the U.S. military industrial complex that President Eisenhower warned about in his farewell address and that Kennedy first crossed swords with in the Bay of Pigs fiasco of April 1961. The opening song “Blowin’ in the Wind” is a hopeful anthem that, under Kennedy’s leadership, Dylan’s generation might finally solve the intractable problems of racism, war, and injustice: “The answer, my friend, is blowin’ in the wind / The answer is blowin’ in the wind.” But the singer doesn’t always sound such an optimistic note.

The most artistically ambitious song on Dylan’s sophomore album is “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall,” inspired by the Cuban Missile Crisis. In October 1962, spy plane photos revealed that the Soviets had placed missiles in Cuba, giving the rival superpower easy striking capacity against the United States. Kennedy shared the news in an address to the American people, and a terrifying standoff ensued for several days.

Kennedy and his Russian counterpart Nikita Khrushchev eventually reached a negotiated de-escalation in which the Soviet missiles were public removed from Cuba (and American missiles were privately removed from Italy and Turkey). In the interim, however, the world came closer to nuclear war than it ever has before or since.

Dylan captures this terrifying experience and howls out a warning in the apocalyptic “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall.” In his 1963 interview with Studs Terkel, he denied that the hard rain in the song represented the black rain of nuclear fallout. According to Clinton Heylin’s A Life in Stolen Moments Day by Day, 1941-1995, Dylan debuted the song a month before the Cuban Missile Crisis (33). [Thanks to Mick Gold for pointing this out to me.] However, Dylan told a different story in his 1965 interview with Ray Coleman, asserting that the nuclear showdown in Cuba directly inspired the song:

I wrote it at the time of the Cuban crisis. I was in Bleeker Street in New York. We just hung around at night—people sat around wondering if it was the end, and so did I. Would ten o’clock the next day ever come? What was going to happen? Well, I wrote that song to the tune of “Buffalo Skinner.” An old cowboy song. It was a song of desperation. What would we do? Could we control men on the verge of wiping us out? The words came fast. Very fast. It was a song of terror. Line after line after line, trying to capture the feeling of nothingness. (158)

That guiding question—“Could we control men on the verge of wiping us out?”—inspired several songs on Dylan’s next album The Times They Are A-Changin’, written and recorded before the assassination, though not released until February 1964. As the title song boldly proclaims, Dylan viewed the generation struggle between the old and the young as the central conflict of the times.

Come mothers and fathers

Throughout the land

And don’t criticize

What you can’t understand

Your sons and your daughters

Are beyond your command

Your old road is rapidly agin’

Please get out of the new one if you can’t lend your hand

For the times they are a-changin’

Dylan was dubbed the “voice of his generation” because he expressed both the frustrations and the aspirations of the young, and because he was willing to speak hard truths to the old, rich, and powerful, forces with a vested interest in maintaining the status quo. “The Times They Are A-Changin’” puts politicians, propagandists, and parents on notice: get with the program or get out of the way. Roll up your sleeves or you’ll be rolling in your graves.

Kennedy was the youngest man every elected President of the United States. Born May 29, 1917—a Gemini like Dylan—he was also the first President born in the twentieth century. Dylan and his circle generally regarded Kennedy as on their side, even if he didn’t always move as quickly or go as far as they wanted. In his memoir Chronicles, Dylan paints a sympathetic portrait of Kennedy, albeit one refracted through the perspective of his mother:

John Kennedy, before he became president, when he was still a senator, had come up to Hibbing on the campaign trail but that was about six months after I left. My mother said that eighteen thousand people had turned out to see him at the Veterans Memorial Building and that people were hanging from the rafters and others were in the street, that Kennedy was a ray of light and had understood completely the area of the country he was in. He gave a heroic speech, my mom said, and brought people a lot of hope. (231)

Dylan may not have been in the Hibbing crowd, but he does affirm that he backed Kennedy: “If I had been a voting man, I would have voted for Kennedy just for coming there. I wished I could have seen him” (231). You might read that passage and think, “Wait, is Dylan saying that he didn’t even vote for Kennedy?” Yes, he is. But remember that the 26th Amendment to the Constitution, which lowered the voting age from 21 to 18, wasn’t ratified until 1971. So Bobby Zimmerman was too young to vote for Kennedy in 1960. In the meantime, Bob Dylan certainly found an outlet for expressing his views through songs.

Responses to the Assassination

I was born on January 4, 1970—I missed the sixties by five days! So I have no firsthand memories of the assassination and must rely on the accounts of others. Anyone who lived through that bloody day will remember where they were and how they reacted when they learned that President Kennedy had been killed. Many musicians in Dylan’s circle are on record with their responses, and these testimonies chronicles the disbelief, grief, outrage, confusion, and despair experienced across the nation and around the globe.

For the fiftieth anniversary, Gus Russo and Harry Moses edited a collection called Where Were You?: America Remembers the JFK Assassination. That’s where I learned that, by pure accident, Peter, Paul and Mary were scheduled to perform in Dallas on November 22, 1963.

The group immediately canceled when they heard the news, and Peter Yarrow hopped in a car to get out of town as quickly as possible. He vividly recalls how traumatic the murder was for him and other young Kennedy supporters:

We adored JFK; we didn’t just admire him. He was more than a president, however esteemed and honored the term “president” might be. He was somebody who gave us hope, direction. He had a heart that we felt was embracing us all, and we loved him; we didn’t just admire him. […] JFK was in people’s hearts, their own flesh and blood. He was America personified, and to lose him was unthinkable. (Russ and Moses 341)

In another uncanny coincidence, Judy Collins found herself in the post-assassination epicenter of Washington, D.C., where she had club dates scheduled that week. She expresses the emotional devastation felt by those who looked up to Kennedy as a visionary leader:

By the night of November 22, we were crushed. It was over; we were done. This exciting, young, optimistic activist in a lot of ways—imaginative, artistic, articulate, stirring in his speeches, eloquent in his discussion, with an ability to move around in the world, help us not to be blown to pieces, and help us find our way—was gone. The feeling was devasting really. […] In the days immediately after the assassination, all performances, all shows, all joy it seemed were canceled. Everything stopped. It was like the world came to an end. (Russo and Moses 351)

Roger McGuinn of The Byrds spent the evening of November 22 rewriting the lyrics to “He Was a Friend of Mine.” Many readers of Shadow Chasing will be familiar with Dylan’s touching 1961 rendition of this folk song. McGuinn retained the title, refrain, and melody, but the new words repurpose the song as a eulogy for President Kennedy.

He was a friend of mine

He was a friend of mine

His killing had not purpose

No reason or rhyme

He was a friend of mine

He was in Dallas town

He was in Dallas town

From a sixth-floor window

A gunner shot him down

He died in Dallas town

The song ends: “Leader of a nation / For such a precious time / He was a friend of mine.”

The Byrds played “He Was a Friend of Mine” at the celebrated 1967 Monterey International Pop Festival, but that song didn’t make the cut into D. A. Pennebaker’s film. That’s probably because of David Crosby’s inflammatory introduction:

You know they’re shooting this for television. I’m sure that they’ll edit this out. I want to say it anyway, even though they will edit it out. When President Kennedy was killed, he was not killed by one man. He was shot from a number of different directions by different guns. The story has been suppressed. Witnesses have been killed. And this is your country, ladies and gentlemen.

At the end of the song, Crosby added: “Thank you. As I said, they will censor it I’m sure. They can’t afford to have things like that on the air.”

In Chronicles, Dylan doesn’t mention his response to the Kennedy assassination on the day itself. Instead, he shares his more mature reflections years later after he had become a husband and father:

Having children changed my life and segregated me from just about everybody and everything that was going on. Outside of my family, nothing held any real interest for me and I was seeing everything through different glasses. Even the horrifying news items of the day, the gunning down of the Kennedys, King, Malcolm X . . . I didn’t see them as leaders being shot down, but rather as fathers whose families had been left wounded. Being born and raised in America, the country of freedom and independence, I had always cherished the values and ideals of equality and liberty. I was determined to raise my children with those ideals. (114-15)

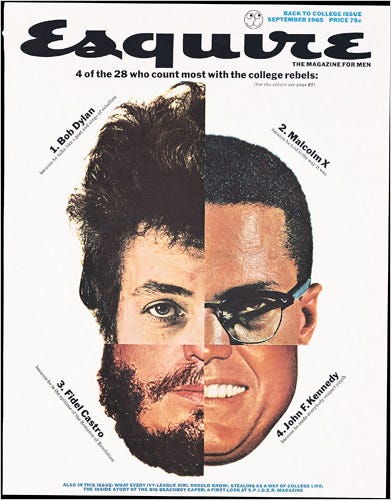

In that same chapter, Dylan rails against the unwelcome pressures that came with being anointed as some kind of sixties messiah. For example, he angrily recalls, “Esquire magazine put a four-faced monster on their cover, my face along with Malcolm X’s, Kennedy’s, and Castro’s. What the hell was that supposed to mean? It was like I was on the edge of the earth” (119).

It cannot have been lost on Dylan that, by the time that issue came out in September 1965, Kennedy and Malcolm X had both been killed and Castro had been the target of multiple assassination plots. In the documentary No Direction Home, Al Kooper recalls why he quit Dylan’s touring electric band in the fall of 1965:

I actually was frightened when I saw the tour itinerary and saw that we were going to play Dallas, where they had just killed the President. And I thought, “If they didn’t like that guy, what are they gonna think of this guy?” I didn’t want to be the analogy to John Connolly [the Governor of Texas who was shot in the front seat of Kennedy’s car]. I didn’t want to be the guy next to him.

The documentary also includes backstage footage from the 1966 tour of England, when a manager informs the singer that a death threat had been phoned into the venue. Dylan downplays the threat as a sign of the times: “Do they do this often? I don’t mind being shot, man, but I don’t dig being told about it.”

Paul Stookey remembers how discouraging the post-1963 period was for progressive activists, artists, and audiences who had been advocating for political change:

The impact of the Kennedy’s assassination, added to that of Martin Luther King and Bobby Kennedy, created a wall that shut out all the sunlight that had been coming in. To the extent that I was a progressive liberal, and aware now of that good that some political and community work could do, the obvious message to me, written on this wall created by these three assassinations, was: “Don’t do it. People who are get shot at.” I didn’t feel that so much in the music, but, boy, within a year’s time, it seemed like music stopped talking about those things we shared as a community and started saying, “Dance. Just get out and dance. Life is frivolous; it has no meaning, no purpose. Get out and dance. Dance, dance, dance.” For the next ten years our lives, with the exception of “Abraham, Martin, and John,” I didn’t hear any music that was deeply convincing or moving. (Russo and Moses 342-43)

It’s interesting that Stookey singles out “Abraham, Martin, and John” because that song served a beacon of hope for Dylan as well. Songwriter Dick Holler wrote it after the murders of Martin Luther King and Bobby Kennedy, connecting them with the earlier assassinations of Abraham Lincoln and John F. Kennedy. Dion turned the song into a hit in 1968. On 23 occasions, Dylan sang “Abraham, Martin, and John” as a duet with Clydie King.

After his born-again conversion to Christianity, Dylan insisted on exclusively playing gospel songs on his tours from the fall of 1979 through the spring of 1980, much to the consternation of many longtime fans. However, beginning with his November 1980 residency at San Francisco’s Warfield Theatre, he began reintroducing secular music into his setlists again. “Abraham, Martin, and John” was ideally suited for the purpose of reconnecting with audiences who had followed him since the sixties but were skeptical of his evangelical turn. The song functioned like a renewal of vows rooted in shared values from the Kennedy era.

Didn’t you love the things they stood for?

Didn’t they try to find some good for you and me?

And we’ll be free some day soon

It’s gonna be one day

It’s moving to hear this duet about fallen heroes whose faith, hope, and charity lived on despite their violent deaths. And it’s especially powerful to see it performed by a Black woman and white man sitting together at the piano bench, tinkling the ebony and ivory while singing their hearts out, like a physical manifestation of the harmony that the lyrics aspire toward. Their performance of “Abraham, Martin, and John” was particularly poignant on the final night of the residency, which just happened to fall on November 22, the 17th anniversary of JFK’s assassination. Check out this bootleg:

Notice the joyous responses from the San Francisco crowd. If Dylan was trying to reconcile with his estranged audience in 1980 by bringing their shared sixties spirit back to life, he succeeded magnificently.

Camelot

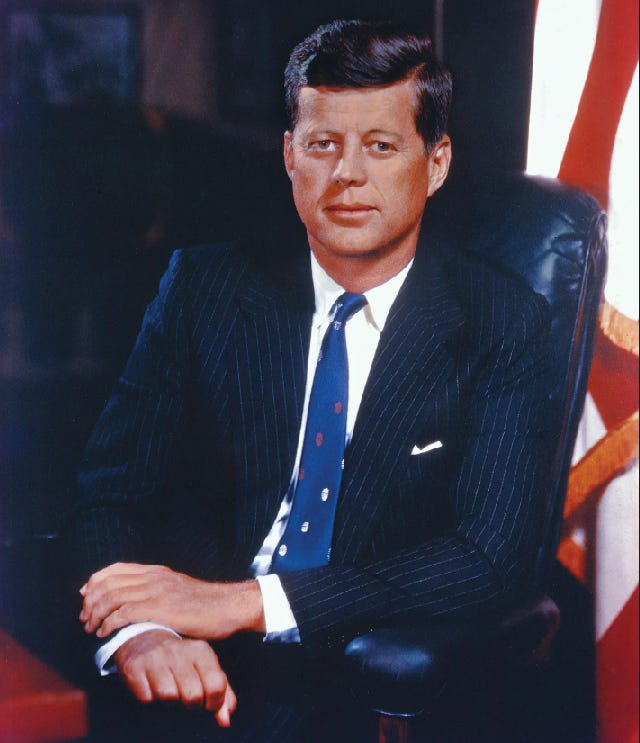

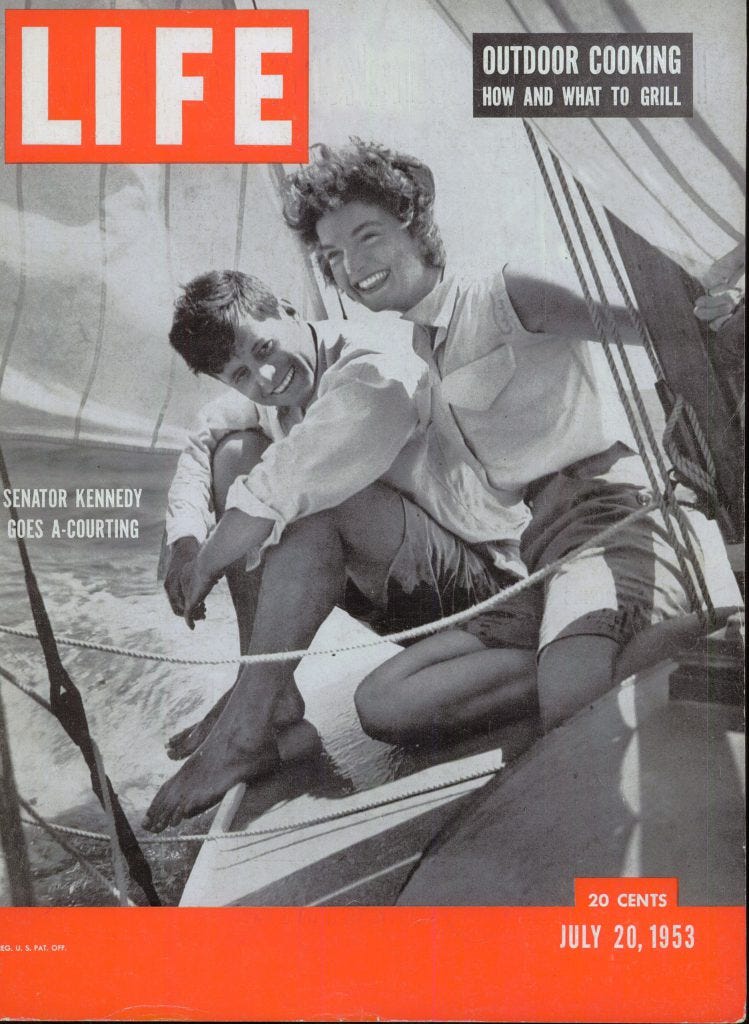

Dylan’s musical circle clearly loved JFK, and so did the camera. John and Jacqueline Kennedy—Jack and Jackie—were the most photogenic couple to ever occupy the White House, and the media took notice. Life was the most visually opulent magazine of the era, and its photojournalists regularly spotlighted the Kennedys. They married in September 12, 1953, in the same Newport, Rhode Island, which hosts the famous folk festival. But by then the celebrity couple had already graced the cover of Life:

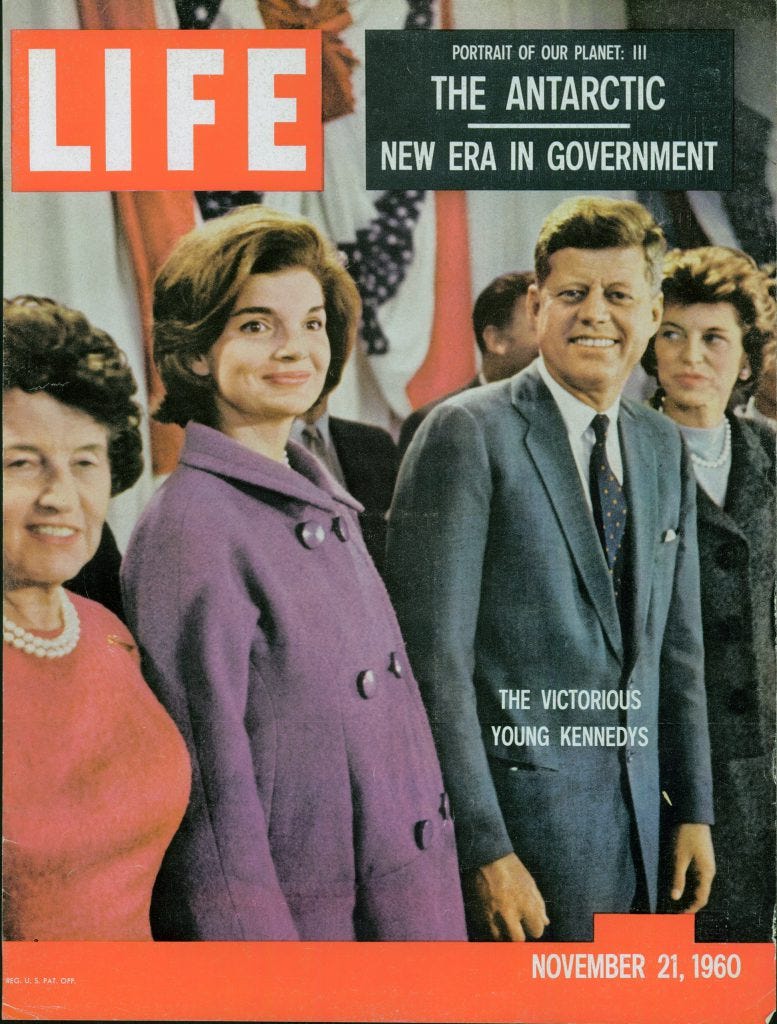

The beaming pair were also featured in the first issue after JFK’s election in November 1960:

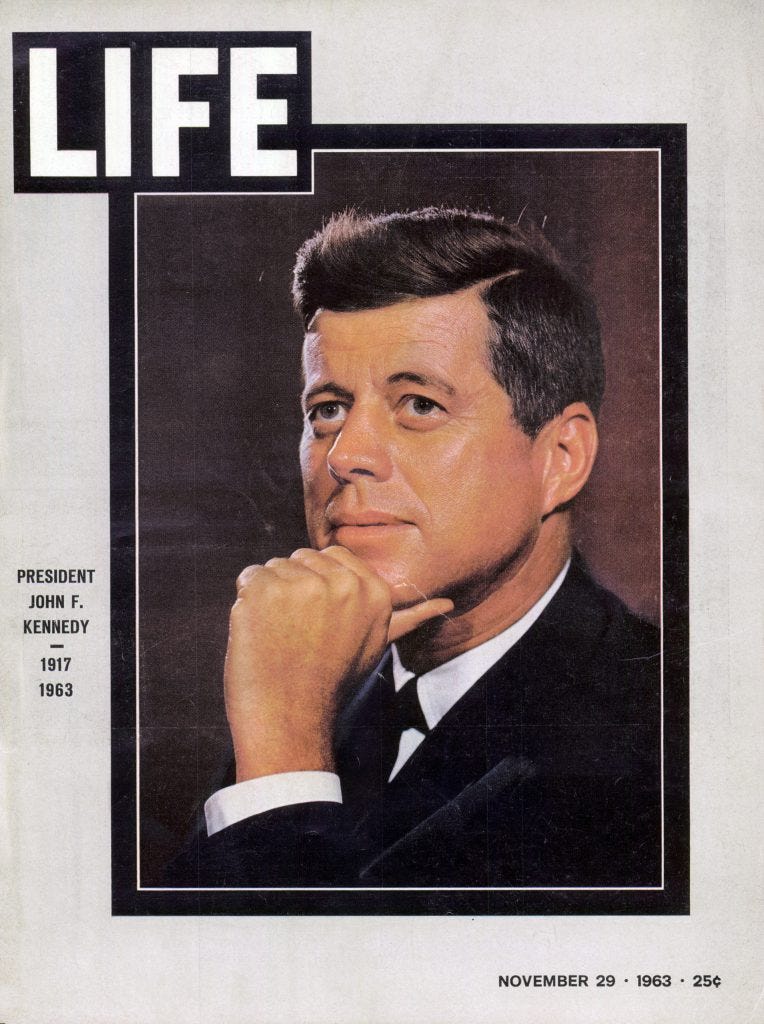

Like every other major news outlet, Life focused its coverage on Kennedy’s assassination in late November 1963, leading with this black-bordered photo:

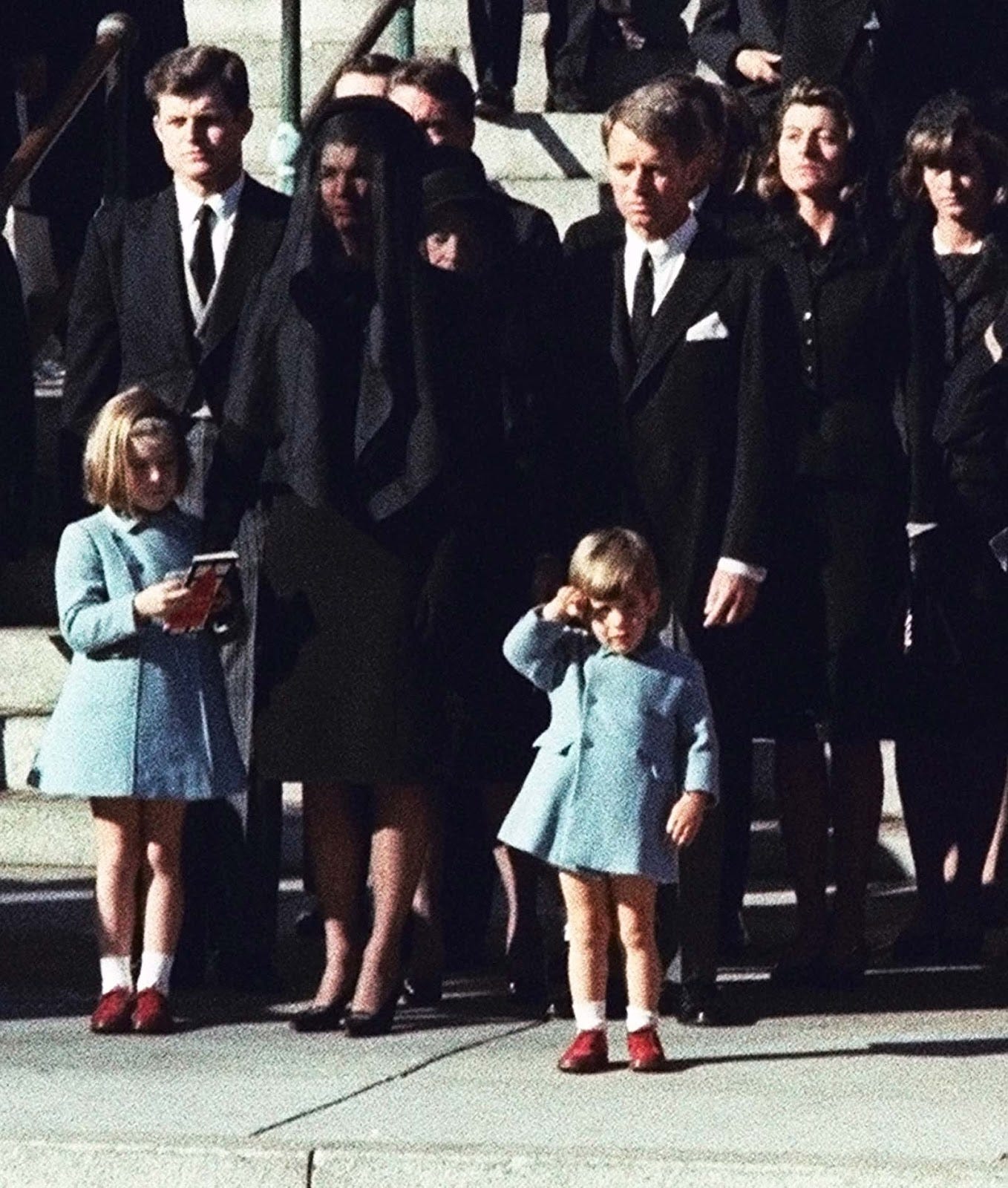

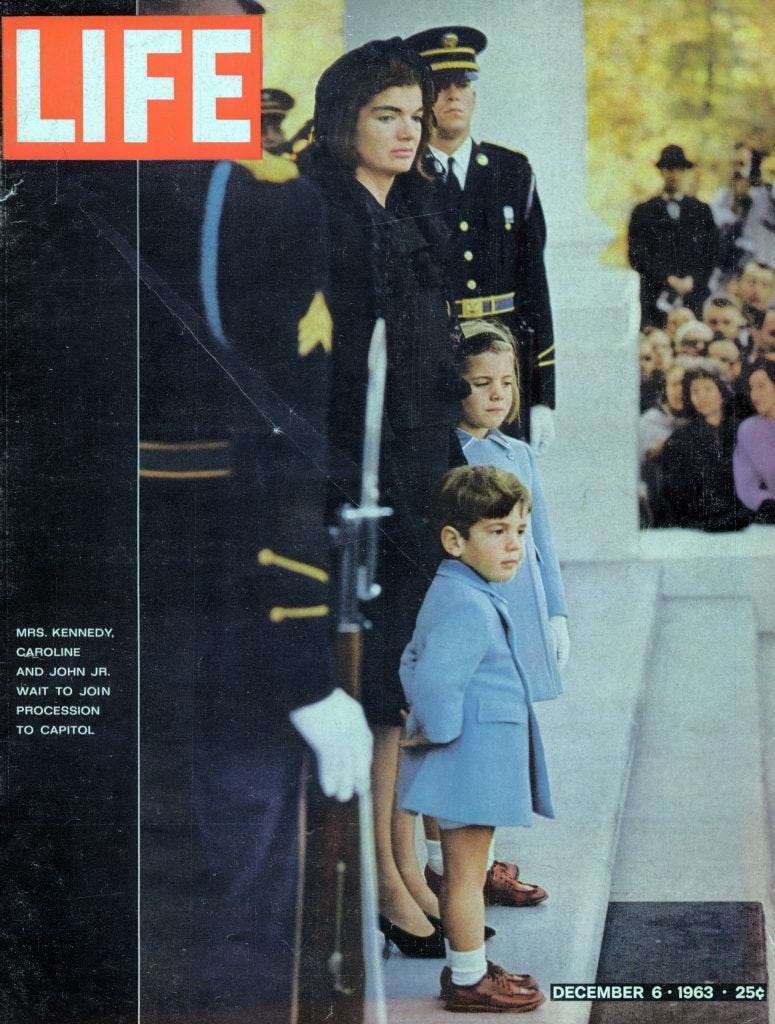

The next issue concentrated on Kennedy’s funeral, featuring this heartbreaking picture of his widow and children Caroline and John, Jr. (who turned three years-old the same day as his father’s funeral):

In “Murder Most Foul,” Dylan describes November 22, 1963, as “The day that they blew out the brains of the king.” The king? Kennedy was a democratically elected president, not a hereditary monarch. But the Kennedys were often viewed as a kind of American royalty. More specifically, JFK is often revered as an American King Arthur, and his thousand-day presidency is exalted like the golden age of Camelot.

If that sounds more like myth than history, that’s because it is. We can trace the birth of this legend back to Jackie Kennedy’s interview with Theodore White for the funeral issue of Life pictured above. She confides:

When Jack quoted something, it was usually classical, but I’m so ashamed of myself—all I keep thinking of is this line from a musical comedy. At night, before we’d go to sleep, Jack liked to play some records; and the song he loved most came at the very end of the record. The lines he loved to hear were: Don’t let it be forgot, that once there was a spot, for one brief shining moment that was known as Camelot.

This is not just some off-the-cuff anecdote. This is myth-making. To make certain her point isn’t lost on her interviewer, she spells it out: “There’ll be great Presidents again—and the Johnsons are wonderful, they’ve been wonderful to me—but there’ll never be another Camelot again.”

The widow is intent upon burnishing her dead husband’s legacy as the hero of the age. And she does a damn fine job of it, too. Who could fail to be moved by her description of Jack as a boy aspiring to achieve greatness?

Once, the more I read history the more bitter I got. For a while I thought history was something that bitter old men wrote. But then I realized history made Jack what he was. You must think of him as this little boy, sick so much of the time, reading in bed, reading the Knights of the Round Table, reading Marlborough. For Jack, history was full of heroes. And it if made him this way—if it made him see the heroes—maybe other little boys will see. Men are such a combination of good and bad. Jack had this hero idea of history, the idealistic view.

In case any readers missed the thesis statement, White reiterates it at the end of his piece: “Don’t let it be forgot, that once there was a spot, for one brief shining moment that was known as Camelot—and it will never be that way again.”

We might just as well quote Dylan’s elegy for another fallen hero named John:

Shine your light

Move it on

You burned so bright

Roll on John

Dylan knows a thing or two about myth-making, too. His book Chronicles is, among many other things, a brilliant work of self-mythology, drawing freely upon archetypes of the hero’s quest to shape his graced life as the stuff of legend and divine destiny. As Rebecca Slaman perceptively pointed out in a discussion with Laura Tenschert for Definitely Dylan, Dylan’s lyrics in the sixties are also saturated in the Camelot mystique, populated with kings and queens, princes and princesses, castles, towers, steeples, and “Once upon a time” fairy tales. Of course, Dylan may have absorbed this from his own childhood storybooks. But it may also reflect yet another influence from King John who presided over his formative musical years.

For all the romance of the Camelot myth, the brutal lessons of history teach us that kings often meet bloody ends. I think of the great speech from Shakespeare’s Richard II where the beleaguered king reflects upon the violent fate that awaits him:

For God’s sake, let us sit upon the ground

And tell sad stories of the death of kings—

How some have been deposed, some slain in war,

Some haunted by the ghosts they have deposed,

Some poisoned by their wives, some sleeping killed—

All murdered. For within the hollow crown

That rounds the mortal temples of a king

Keeps Death his court; and there the antic sits,

Scoffing his state and grinning at his pomp,

Allowing him a breath, a little scene,

To monarchize, be feared and kill with looks,

Infusing him with self and vain conceit,

As if this flesh which walls about our life,

Were brass impregnable; and humoured thus,

Comes at the last and with a little pin

Bores through his castle wall, and farewell, king! (3.2.155-70)

King Richard has a premonition that he will soon learn this lesson the hard way, that the myth is just a man, that the glorious leader is not made of brass impregnable but of weak flesh and fragile bone. Has there ever been a more graphic display of boring through the castle wall of a king’s mortal temple than the headshot captured on the Zapruder film?

President Kennedy may have had a similar premonition. In his New York Times editorial the day after the assassination, James Reston recalled a recent appearance by JFK before a group of civil rights organizations. “He tolled off the problems that beset him on every side and then, to the astonishment of everyone there, suddenly concluded his talk by pulling from his pocket a scrap of paper and reading the famous speech of Blanche of Spain in Shakespeare’s King John” (Semple 179). That’s right: King John. Here’s the eerily prescient passage Kennedy read:

The sun’s o’ercast with blood: fair day, adieu.

Which is the side that I must go withal?

I am with both. Each army hath a hand,

And in their rage, I having hold of both,

They whirl asunder, and dismember me. (3.1.326-30)

Reston asks, “Did he have a premonition of tragedy—that he who had set out to temper the contrary violences of our national life would be their victim?”

I want to leave you with one more passage, this one from Kennedy himself. It comes from the speech he was scheduled to present that afternoon in Dallas but never got to deliver. The final paragraph gives me chills. It makes me sad for my country to see how far our current president falls short of the responsibilities of leadership set by high-minded predecessors like Kennedy. But it also makes me appreciate what strength and inspiration Dylan’s generation drew from the visionary leadership of JFK. Finally, it makes me wonder if Dylan was reading more than the book of Isaiah when he wrote “All Along the Watchtower.” Judge for yourself:

We in this country, in this generation, are—by destiny rather than choice—the watchmen on the walls of world freedom. We ask, therefore, that we may be worthy of our power and responsibility—that we may exercise our strength with wisdom and restraint—and that we may achieve in our time and for all time the ancient vision of peace on earth, goodwill toward men. That must always be our goal—and the righteousness of our cause must always underlie our strength. For as was written long ago: “Except the Lord keep the city, the watchman waketh but in vain.”

Works Cited

The Byrds. “He Was a Friend of Mine.” Turn! Turn! Turn! Columbia, 1965.

Coleman, Ray. Interview with Bob Dylan. Melody Maker (22 May 1965). Rpt. in Every Mind Polluting Word: Assorted Bob Dylan Utterances. Ed. Artur Jarosinski. Don’t Ya Tell Henry, 2006, 154-59.DeLillo, Don. Libra. New York: Penguin, 1988.

Dylan, Bob. Chronicles, Volume One. Simon & Schuster, 2004.

---. Official Lyrics. The Official Bob Dylan Website. https://www.bobdylan.com/.

Heylin, Clinton. Bob Dylan: A Life in Stolen Moments Day by Day, 1941-1995. Schirmer Books, 1996.

Marcus, Greil, and Don DeLillo. “Greil Marcus and Don DeLillo Discuss Bob Dylan and Bucky Wunderlick (2005).” Greil Marcus (17 October 2014), https://greilmarcus.net/2014/10/17/greil-marcus-and-don-delillo-discuss-bob-dylan-and-bucky-wunderlick-2005/.

No Direction Home. Dir. Martin Scorsese. Paramount Pictures, 2005.

Russo, Gus, and Harry Moses, eds. Where Were You?: America Remembers the JFK Assassination. Lyons Press, 2013.

Scott, A. O. “J.F.K., Blown Away, What Else Do I Have to Say?” The New York Times (19 March 2025), https://www.nytimes.com/2025/03/18/books/review/john-f-kennedy-assassination-conspiracy-theory.html.

Semple, Jr., Robert B, ed. Four Days in November: The Original Coverage of the John F. Kennedy Assassination by the Staff of The New York Times. St. Martin’s Press, 2003.

Shakespeare, William. King John. Eds. J. J. M. Tobin and Jesse M. Lander. Arden Shakespeare Third Series. Bloomsbury, 2018.

---. King Richard II. Ed. Charles R. Forker. Arden Shakespeare Third Series. Bloomsbury, 2002.

Tenschert, Laura. “‘Oh Mama!’: Women & Dylan with Rebecca Slaman.” Definitely Dylan (6 August 2023), https://www.definitelydylan.com/podcasts/2023/8/6/oh-mama-women-amp-dylan-with-rebecca-slaman.White, Theodore H. “For President Kennedy: An Epilogue.” Life (6 December 1963). John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, https://www.jfklibrary.org/asset-viewer/archives/thwpp-059-009#?image_identifier=THWPP-059-009-p0002.

It really is chilling to read the speech JFK didn't get to deliver – is it taking things too far to hear its echo also in the "watchman" that lays sleeping in "Tempest", the song that sits alongside "Roll on John"? Maybe it's a different watchman, just like he was singing about a different John, and just like Dylan insisted "Tempest" was totally different from Shakespeare's "The Tempest", but maybe the echoes are there nonetheless. What a beautiful, original, and relevant piece, Graley, thank you – your mind and your writing is inspiring as always, and I look forward to reading the next parts!

"They buy and they sell, they,ll destroy your city they,ll destroy you as well"

I very much want to go to Tulsa again ( I was there in 2019 and had the time of my life) but now I have second thoughts. There is actually a military menace in the Greenland case and many Europeans try to boykot anything American...