Dylan Duets

Suzanne Vega

On May 2, 2025, forty years and a day after her self-titled debut record came out, Suzanne Vega released her excellent new album Flying with Angels. She remains best known for her hits “Luka” and “Tom’s Diner” (particularly the DNA remix) from her sophomore album Solitude Standing (1989). But she has had a very distinguished career since then, and we’ll be digging deeper into her impressive catalogue in this post.

Vega has been outspoken over the years about her influences, and she sometimes writes in direct response to specific singers or songs. For instance, check out “(I’ll Never Be) Your Maggie May,” her defiant reply to Rod Stewart’s “Maggie May” from her breakup album Songs in Red and Gray (2001). On the new album, listen to “Lucinda,” her loving homage to Lucinda Williams. The track that really catches my attention on Flying with Angels is her answer song “Chambermaid.”

Even before Vega sings a word, readers of Shadow Chasing will instantly recognize that the melody is lifted from Bob Dylan’s “I Want You.” Her lyrics reimagine his classic from the perspective of the chambermaid character:

Well, I return to the Queen of Spades

And talk with my chambermaid

She knows that I’m not afraid to look at her

She is good to me

And there’s nothing she doesn’t see

She knows where I’d like to be

But it doesn’t matter

Suzanne Vega’s “Chambermaid” is an ideal subject for my “Dylan Duets” series. As you may recall from the first installment on Gillian Welch & Dave Rawlings’s Woodland, this series focuses on intertextual duets. Basically, I put Dylan songs in conversation with others he influenced and consider what they have to say to each other.

In a fascinating 2014 interview with Robert Hilburn, Dylan explained how he sometimes meditates upon an old song until a new song emerges:

What happens is, I’ll take a song I know and simply start playing it in my head. That’s the way I meditate. A lot of people will look at a crack on the wall and meditate, or count sheep or angels or money or something, and it’s a proven fact that it’ll help them relax. I don’t meditate on any of that stuff. I meditate on a song. I’ll be playing Bob Nolan’s “Tumbling Tumbleweeds,” for instance, in my head constantly—while I’m driving a car or talking to a person or sitting around or whatever. People will think they are talking to me and I’m talking back, but I’m not. I’m listening to the song in my head. At a certain point, some of the words will change and I’ll start writing a song. (Hilburn 1343)

Vega uses a similar approach. In her interview for the American Masters documentary Lou Reed: Rock and Roll Heart, she reflects,

There are several people that I listen to when I want to get myself going, or when I want to feel inspired, or when I want to get myself in the frame of mind for writing songs. […] Leonard Cohen is one I listen to when I want a sort of emotional depth. Bob Dylan, I listen to when I want to feel that my mind is expanding in a certain way that it doesn’t normally do. And Lou Reed, I listen to when I want something to be focused and economical, and when I want to write about something that’s really difficult for me to write about because he uses very few words and he gets the story out right away.

At first I planned to concentrate exclusively on Vega and Dylan. However, as I immersed myself in her music and discovered her many thoughtful interviews and essays over the years, I decided to expand my scope from a duet into a quartet. I still want to put “Chambermaid” in conversation with “I Want You,” but the creative dialogue will be much richer if we invite Leonard Cohen and Lou Reed into the conversation.

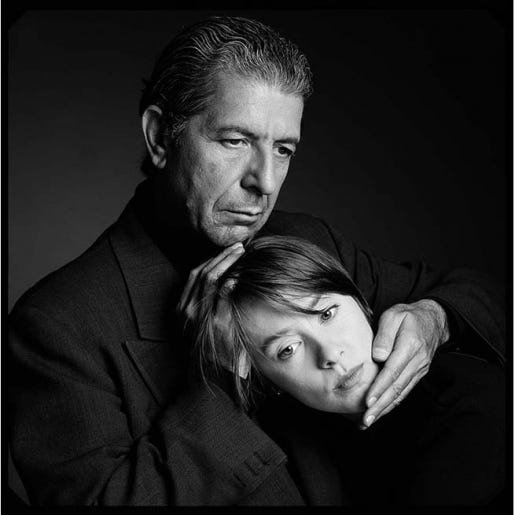

Leonard Cohen

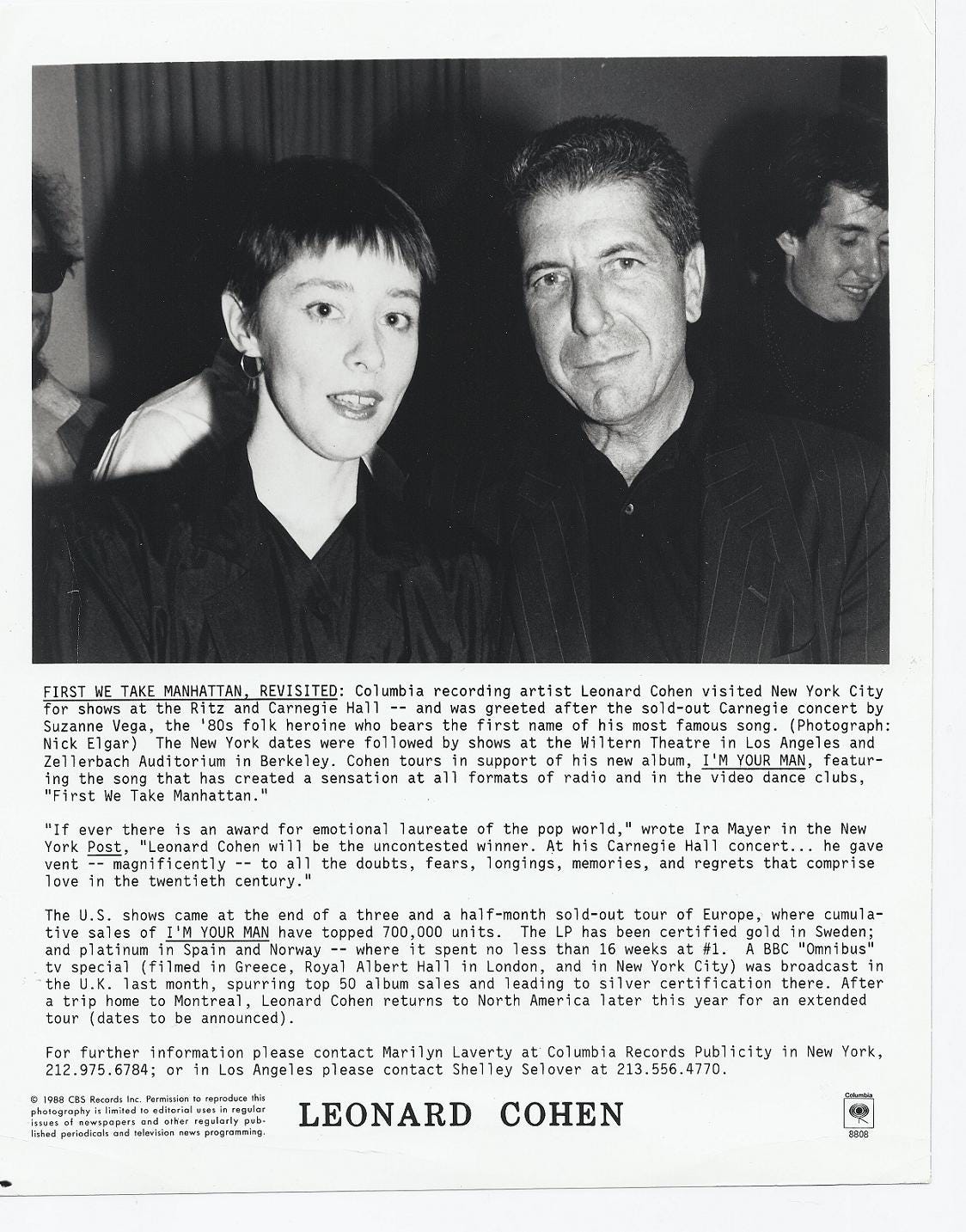

Anyone named Suzanne is destined to be a Leonard Cohen fan. As a kid growing up in East Harlem and the Upper West Side in the sixties, Vega was sometimes asked if she was named after Cohen’s “Suzanne” (she was not). She first heard the song by way of Judy Collins’s cover. When she finally bought Songs of Leonard Cohen at the age of 14, it was love at first listen. They met backstage a few times in the eighties, including in 1988 at Carnegie Hall.

She sang “Who by Fire” with him at the Juno Awards in 1991, when he was inducted into the Canadian Music Hall of Fame. She covered “Story of Isaac” for the 1995 tribute album Tower of Song: The Songs of Leonard Cohen. She sang “So Long, Marianne” with John Cale for Bleeker Street: Greenwich Village in the 60s (1999). She was also Cohen’s supporting act at Mercedes-Benz World in Weybridge in 2009.

Their most extensive public encounter came in the form of a wide-ranging 1993 interview. The conversation was arranged by her record label to promote her fourth album 99.9 F (1992). What emerges, however, is much more than a commercial to boost sales. Their talk ranges from interrogation to seduction, part therapy session and part rabbinical exegesis, laced with charming humor and acute self-awareness about the inherent absurdities of the celebrity interview.

“You have managed to make austerity extremely seductive,” Cohen declares. “There is a very seductive quality about your record, although nothing is given away, nothing is thrown away, nothing is revealed” (Passionate Eye 89). Hard not to hear an echo of Dylan’s “The Ballad of Frankie Lee and Judas Priest” in that last remark. Cohen later revises his assessment: “I think that you are revealing something. There’s something, in the most refined and abstracted way, flirtatious about the way you refuse to reveal anything” (Passionate Eye 90). Cohen knows flirtation. Near the end of the interview he offers this fevered description of 99.9 F: “I see this album as an exquisite, refined mating call of one of the most delicate and refined and concealed creatures on the scene. This is the mating call of concealment. This is how secrecy woos her lover” (Passionate Eye 117).

Read in isolation, the quotes above may sound like Leonard the Lothario on the prowl. But I actually think he’s onto something important, not just with respect to 99.9 F, but more broadly with Vega’s approach to songwriting. Secrets are at the heart of her most compelling songs, and she plays a game of hide-and-seek with the listener, allowing glimpses of what lies hidden before retreating behind a veil of concealment. Cohen approaches the subject delicately but persistently, circling in on the essence of Vega’s art:

Now I don’t mean to be tedious with this emphasis on this secrecy but not everybody writes every song about something that happens offstage, about something that is concealed, about a secret that is not told, not whispered. […] It’s a strong theme in the record, and that’s why I’m just poking around trying to find out what this is. Not what the secret is, but what your devotion to the secret is, and how it became in a certain sense the aesthetic irritation around which the pearl of the song formed. It’s something that seems to be very present in your psyche, this notion that there’s something to be concealed, something to be discovered, something not quite heard, something not quite understood, something glimpsed behind the veil. It seems to be there over and over again and forgive me for trying to uncover something which has been so deliberately concealed. (Passionate Eye 96-97)

If Cohen hadn’t become a poet and a singer, he could have made his living as a head-shrinker.

Vega accepts Cohen’s diagnosis, but then she deftly turns the tables on him, describing the mystery at the core of his own songs:

SZ: It’s become the way I prefer to work because there’s something beautiful in it to me. There’s something beautiful in presenting it that way with the whole mystery about it intact. I think the kind of writing that I always loved was the kind of writing that had all the complications in it and everything was not explained completely. You have to say the same thing about your own work. You don’t reveal everything, relationships are not always clear. There’s a lot of specific things that are hinted at and you fill in the rest with your imagination but you don’t come out and blurt out the sort of obvious arithmetic of it. You don’t come out and say, “Well, I loved you and you don’t love me,” although maybe you have said that.

LC: I say it over and over again, I thought.

SZ: Which is why I was attracted to your music at a very early age, it explained, to me it had the world the way I knew it. It didn’t try and make it simple, it didn’t try and clear it up for everyone. It kept it as murky as it actually is in life, and that to me is what I like about it. (Passionate Eye 97-98)

So what is this mysterious hidden secret? Another song from 99.9 F, “Bad Wisdom,” implies, but never confirms, that it is something of a violent and/or sexual nature:

Mother, the doctor knows something is wrong

’Cause my body has strange information

He’s looked in my eyes and knows I’m not a child

But he doesn’t ask the right question

The chorus weighs the cost for learning these harsh lessons at a very young age:

What price for bad wisdom?

What price for bad wisdom?

Too young to know too much too soon

Bad wisdom

Bad wisdom

In my opinion, the most interesting treatment of the theme on 99.9 F is “Rock in This Pocket (Song of David),” clearly influenced by Cohen’s “Story of Isaac.” My favorite version of “Story of Isaac” is on Leonard Cohen’s Live Songs (1973).

He prefaces this performance by announcing, “This is a song called ‘The Story of Isaac,’ and it’s about those who would sacrifice one generation on behalf of another.” Knowing that Cohen performed this song in Berlin less than three decades after World War II and the Holocaust lends extra gravitas to the song.

One of Cohen’s important creative decisions is to foreground Isaac’s youth:

Well, the door it opened slowly

My father he came in

I was nine years old

And he stood so tall above me

His blue eyes they were shining

And his voice was very cold

Cohen revisits the ancient tale of Abraham and Isaac, where the father is willing to sacrifice his only son. The song is written and performed in the context of the Vietnam War, as well as a series of bloody conflicts in the Middle East, and Cohen delivers “Story of Isaac” as a rebuke against the masters of war: “You who build these altars now / To sacrifice these children / You must not do it anymore.” It’s a political statement, but it’s more primal than that. In Cohen’s hands “Story of Isaac” becomes a howl of protest against the old, strong, and rich for exploiting, injuring, and killing the young, weak, and poor.

Vega shares Cohen’s anti-war principles, as evident from her choice to sing “Rock in This Pocket (Song of David)” at a Ukraine Benefit in 2022.

Obviously, Vega is familiar with Cohen’s most famous song about King David, “Hallelujah”: “Now I’ve heard there was a secret chord / That David played, and it pleased the Lord / But you don’t really care for music, do ya?” But “Rock in This Pocket (Song of David)” resonates most closely with “Story of Isaac” because both depict the clash of a vulnerable child against a ruthless adult. The song is told from young David’s perspective, confronting the seemingly invincible giant Goliath:

And what’s so small to you

Is so large to me

If it’s the last thing I do

I’ll make you see

The small thing Vega refers to is not just the rock but David himself. Note that the moment she dramatizes isn’t the climactic clash between the boy and the giant, but instead the modest prelude, when the child is tightening his grip on the rock and screwing his courage to the sticking place. Before the battle comes the inner resolve to resist—David ain’t gonna work on Goliath’s farm no more:

I might be out like a light

Extinguished in the throw

But I’ll hit my mark

And you’ll know

Because I’m really well acquainted

With the span of your brow

And if you didn’t know me then

You’ll know me now

You’ll know me now

In the interview with Cohen, the sage cuts straight to the heart of the acolyte’s accomplishment:

LC: Is this some idea of the David story?

SZ: Yeah, it’s some idea of it. It’s a very simple version of the story of David and Goliath. It’s the moment where he’s trying to get Goliath’s attention, you might say. Maybe Goliath in his mind is saying, well you’re too small. You’re just too small for me, I can’t even look at you because you’re too small. David is saying, well, it’s this small thing that can bring you down, that will cause your fall.

LC: The power of the small.

SZ: Yeah, the power of the small thing.

LC: You’ve mastered that, the power of the small. […]

SZ: The power of the small. The idea that small things have their own voice and their own will and their own life and their own dignity in the world—that is very often trampled on by people who feel they are bigger. (Passionate Eye 100-01)

Hidden child abuse, told from the victim’s perspective, a kid with bad wisdom searching for a voice and some dignity—these are also the primal subjects of Vega’s most famous song, “Luka.”

Lou Reed

Suzanne Vega spent a lot of time with Lou Reed. They first met when he interviewed her for an episode of MTV’s 120 minutes in 1986. During the eighties and nineties, they hung out in similar New York music circles and occasionally crossed paths. They got to know each other better during a 2009 trip to the Czech Republic. Vega has regularly covered Reed’s “Walk on the Wild Side” in concert, and she includes it on her live album An Evening of New York Songs and Stories (2020). In the latter years of Reed’s life, he and Vega became good friends, visiting each other’s summer homes as neighbors in East Hampton.

Long before she got to know him personally, Vega was already a massive fan. As she writes in her touching tribute for The Times in 2013, the month after his death, “Lou Reed changed my life—artistically and actually.”

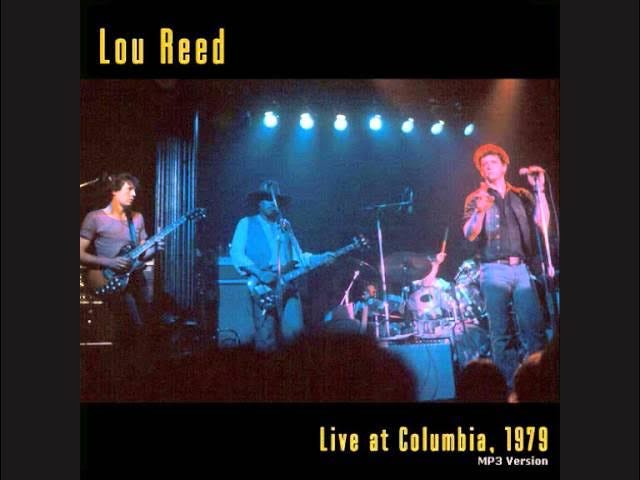

The epiphany came when she first saw him in concert at Columbia University in 1979. She was initially put off by his bizarre stage antics: “Lou threw lighted cigarettes at the audience, kissed his lead guitarist on the mouth, tied up his arm and simulated shooting up, abused the audience with profanity. They shouted that he was ‘an animal.’ He smacked over the mike stand repeatedly and two scared-looking roadies would run out and set it back up.”

Gradually, however, he began to focus more on the songs, and that’s when the lightning bolt struck: “Then I heard these lyrics: ‘Caroline says / As she gets up off the floor / You can hit me all you want to / But I don’t love you anymore.’ He was writing about real life, about abuse, in a way I had never heard before in a song. It altered me.”

“Caroline Says II” appears on Reed’s groundbreaking Berlin (1973). In Lou Reed: The King of New York, Will Hermes gives this concise distillation of the album:

The story Reed conjured was a tragedy based around a couple: Caroline, a drug-taking “Germanic Queen” who sleeps around with assorted characters (one of them “a Welshman”), and her partner, Jim, an abusive speed freak who would stay up “for five days” at a time, makes love “by proxy,” and evidently beats her “black and blue.” She loses her children, and in the end, she kills herself, slitting her writs on the bed the couple once shared. (Hermes 234)

Hermes makes it clear that Reed drew upon difficult personal experiences for the songs, particularly his relationships with Nico and then-wife Bettye Kronstad.

After her transformative experience seeing Reed live, Vega writes in her tribute, “I became obsessed with his work. I wanted to learn how to get some of that blunt truth-telling ability for myself. It wasn’t pretty, but it was powerful. I bought the Berlin album—I was listening to it on the Sunday afternoon in August 1984 I wrote the song ‘Luka.’”

Vega wrote “Luka” when she was only 25 years old, and if she’d never written another word her musical legacy would still be secure. It’s a masterpiece. The song tells the story of a child named Luka. He is clearly a victim of abuse, and yet no one in his building seems willing to acknowledge what is happening, let alone lift a hand to help or to make it stop.

My name is Luka

I live on the second floor

I live upstairs from you

Yes, I think you’ve seen me before

The first-person speaker is Luka. Vega poignantly puts listeners in the position of the building’s tenants, living behind closed doors, perpetuating the violence through their individual and collective silence.

If you hear something late at night

Some kind of trouble, some kind of fight

Just don’t ask me what it was

Just don’t ask me what it was

Just don’t ask me what it was

The music is deceptively upbeat, just like Luka tries to be. But his words make clear that he is poisoned with “bad wisdom.” Experience has taught him not to expect his situation to improve, and this child has no rock in his pocket:

They only hit until you cry

After that you don’t ask why

You just don’t argue anymore

Just don’t argue anymore

Just don’t argue anymore

Deny, repress, hide, keep quiet. This is how Luka survives. He’s young, but he’s no longer innocent or trusting. He knows the score. Adults hurt kids. Adults protect their own.

Yes, I think I’m okay

I walked into the door again

Well, if you ask, that’s what I’ll say

It’s not your business anyway

Luka may not protest or resist, but Vega does. By drawing attention to and sympathy for his plight, the song gives voice to the silenced child.

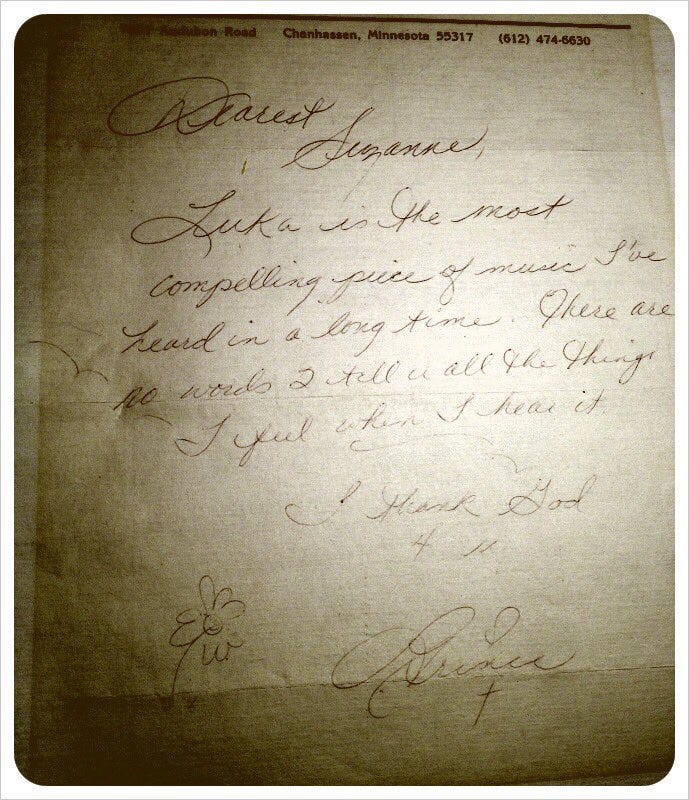

Prince was one of the brightest stars of the eighties, but he was humbled with awe by “Luka.” After his death in 2016, Vega shared on Facebook a beautiful note he sent her:

Dearest Suzanne,

Luka is the most compelling piece of music I’ve heard in a long time. There are no words 2 tell u all the things I feel when I hear it.

I thank God

4 u

Prince

In countless interviews over the years, Vega credits Reed for teaching her how to write “Luka.” “Caroline Says II” unlocked the door. Here is my personal favorite version of the song. This is from the film Lou Reed: Berlin, consisting of live performances of the entire album at St. Ann’s Warehouse in Brooklyn in 2006, intercut with scenes filmed by director Julian Schnabel. Reed is nearly overcome with emotion at times in this riveting rendition:

What did Vega learn from Reed? She has been trying to answer that question for three decades. Here is how she recently explained the impact of “Caroline Says II” on the podcast The Spark Parade:

This became a gateway into the world of Lou Reed. I began to go see him live all the time. I became kind of obsessed with him and his world, and what he was saying, and how he was saying it, and what he was doing. I felt I could learn from this, because my natural tendency as a songwriter is to be more metaphoric, or kind of allude to things. So watching him was a real master class in confrontation. Everything about Lou is forward-facing and confrontive. There’s nothing oblique or sideways about how he would approach an audience or a theme or a song or anything. I don’t know if there’s any metaphor in any Lou Reed song. All of it seems to be just like banging the truth on the head, and hitting you over the head with it as well.

Cohen taught Vega the mysterious allure that could come from concealing a hidden secret. Reed taught her an equally valuable songwriting lesson about the power of direct confrontation, dropping the shields of metaphor, deflection, and projection and standing nakedly vulnerable.

Vega honors Reed’s directness and vulnerability with a brave confession of her own. In her tribute essay, she shares a secret that she had hinted at for years but never explicitly revealed:

People have asked me for 30 years if “Luka” was based on my actual experience. I wrote that song out of my own experience with abuse. I spent the years from 1984 to 2009 in therapy—25 years—and, for me, that’s where those details of abuse, never actually voiced in the song, reside. I don’t talk about it otherwise. I never told Lou my story—I felt I didn’t need to and there was a kind of reserve between us that wouldn’t have allowed for that—but he helped me to give a voice to it.

Reed made a huge personal impact on Vega, but that’s largely a private matter. She has no obligation to put herself on the psychologist’s couch for every interview she agrees to do. She understandably prefers to keep the emphasis primarily on her songs and on Reed’s artistic influence. In The Spark Parade podcast, she sums up the two main songwriting lessons she learned from him:

One is that you can write about these violent situations. And the second one, that I thought was amazing and that he did with a lot of grace, was that although he was male, he could write from this female perspective with no self-consciousness. “Caroline says . . .,” and then he sings it, and you don’t even think twice about it. I think that gave me confidence to sing “Luka” from a male perspective, from a boy’s perspective. So those are the two takeaways from that song that ended up changing my life really. “Luka” was a turning point for my life and my career.

I’ve got a wild theory, so indulge me for a moment. In her new song about Lucinda Williams, Vega breaks the artist’s name down into constituent parts:

Luce is when she holds the light

Cinders what comes after

Holding both inside her soul

All the rage and laughter

I know that Vega has frequently said that Luka was the name of a kid who lived in her building. But I wonder if she was attracted to that name because it blends the song’s sources of inspiration:

Lou + Caroline = LouCa

Bob Dylan

Soon after Time Out of Mind was released, Suzanne Vega appeared on Charlie Rose to discuss the album, along with producer Daniel Lanois and New York Times music critic Jon Pareles. Rose was surprised when she said that she’d never met Dylan. “I mean, yes, he is a legend. But with people that I really love in my life, with songwriters that I really love, I listen to the records. I get what I want from their records. I don’t want to bother them. I don’t want to be in their face and, you know, talk to them about stuff.” At that point in 1997, she had only seen Dylan in concert once, and it was far from the epiphany she experienced with Lou Reed.

I saw him once live, but I didn’t stay. I left halfway through because, first of all, I didn’t have a seat. I was at the Beacon Theatre. I was being shuffled from one stair to the other, and I couldn’t hear. And it was enough, really, to see him. To see his hands, mostly, because he has beautiful hands. You can see that it was the same mercurial guy that he was before. But I wanted to hear the record, I wanted to hear the words, so that’s what I went home to do.

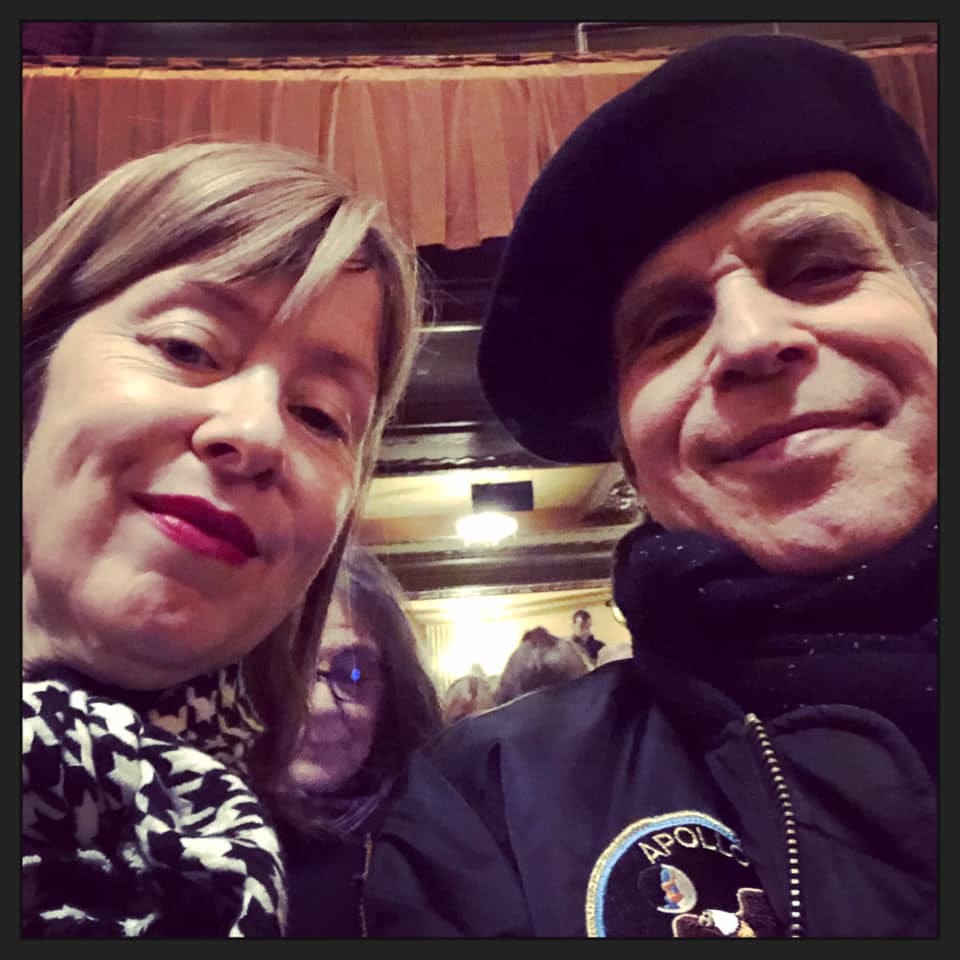

To this day, if Vega has ever met Dylan, I’ve found no evidence of it in my research. But I did come across a lovely photo of her and husband Paul Mills before a Dylan concert in 2019. Looks like she finally found a seat at the Beacon:

Even if she doesn’t know him personally, Vega is intimately familiar with Dylan’s music. In 2006, she wrote a piece for the New York Times called “The Ballad of Henry Timrod,” weighing in on the plagiarism charges swirling around Modern Times. She opens with full-throated praise: “I am passionate about Bob Dylan. As a songwriter, I find there is nothing like singing ‘It’s Alright Ma (I’m Only Bleeding.’ It is nearly eight minutes of cascading images, rich language and the coolest, most unexpected metaphors. My synapses light up in little fireworks, making connections they don’t get to make in ordinary life.”

In October 2015, Vega participated in a roundtable discussion at NYU titled “Does Bob Dylan Still Matter?” A year later, the Swedish Academy resoundingly answered this question in the affirmative, awarding Dylan the 2016 Nobel Prize in Literature. The Guardian ran a piece including several prominent women’s responses to this unexpected selection. Vega led off with an enthusiastic endorsement:

I am thrilled for Bob Dylan and I think it’s very appropriate that he’s being praised for the literary excellence of his work. The citation credits him with having created “new poetic expressions within the great American song tradition” and that’s exactly what he’s done. He’s not being honored as a musician but for the depth and breadth of his vision and the eloquence of the language with which he expresses it.

She goes on to say: “Dylan was a big influence for me. He opened up this incredible, imaginary world. I was nine or 10 when I first heard ‘Mr. Tambourine Man’ and I had a vision of him dancing ‘beneath a diamond sky with one hand waving free.’ It sounded so beautiful, so free. I thought that’s a world I want to be in.”

Vega’s most interesting artistic engagement with Dylan is her new song “Chambermaid.” In her conversation for the podcast Oldster, Vega told Allyson McCabe about the song’s genesis:

I was imagining this woman who was Bob Dylan’s chambermaid, the one that he goes to talk to in the song “I Want You.” And I was thinking, what would that have been like? Just imagine, who is this woman? I imagined her as having her own inner life. She wants to be a writer, but she’s cleaning hotel rooms for a living because sometimes you have to do that. So I was interested in this sort of mentor-disciple relationship between this chambermaid and Bob Dylan and how she studies him, and there’s a kind of intimacy in trying to get to know his mind. It’s not like, are they having an affair? Clearly, they’re not. But there’s this connection, and I liked it that she’s a chambermaid, but that she’s also a writer.

McCabe adds, “And you're giving her agency and subjectivity and a point of view that you don't necessarily think about when you hear him sing that song.” Vega agrees. In other words, “Chambermaid” is a bona fide answer song, in the feminist lineage of Gillian Welch’s “Here Stands a Woman” in response to Dylan’s “Just Like a Woman,” also from Blonde on Blonde (and discussed at length in my previous Dylan Duets piece).

The song begins with this snapshot bio:

I’m the great man’s chambermaid

I’ve seen where his hallowed head is laid

I revere the places he has stayed

And clean crumbs from his typewriter

Vega adopts the persona of Dylan’s servant. Her character is deferential, but there’s at least a hint of resentment in being relegated to such a menial position. “The great man” sounds less like a compliment than a dig muttered under her breath. The image I get is a maid cleaning up after one of Dylan’s all-night sessions at London’s Savoy Hotel in 1965 as captured in Dont Look Back. If that’s the revered chamber Vega has in mind, then she may also be invoking Dylan’s irreverent treatment of Joan Baez, dismissing her as an unwelcome distraction while he’s trying to give birth to his next brainchild.

The rest of the verse directly echoes lines from “I Want You”:

He is good to me

There’s nothing that he doesn’t see

And he knows where I’d like to be

But it doesn’t matter

These lines land differently coming from Vega than Dylan. The brash singer in “I Want You” tells the chambermaid that he’d rather be with her than with the Queen of Spades—does that make him the King of Spades?—but such an arrangement is simply impossible. When Vega’s chambermaid delivers these lines, however, I sense that where she’d like to be is at the writer’s desk rather than behind the vacuum cleaner. But it doesn’t matter.

In the second verse, Vega displays her familiarity with Dylan’s songs, effectively sweeping up crumbs from his typewriter:

On my day off I haunt the docks

Keep to myself, I go for walks

I just make sure the lock still locks

As my ship is coming in

Readers of Shadow Chasing will immediately catch these references. The woman haunting the docks recalls the man trying to track down his lover (a prostitute?) in “Simple Twist of Fate.” While Vega has us down by the docks, she also references Dylan’s “When the Ship Comes In.”

I’m intrigued by the line “I just make sure the lock still locks.” There is something potentially lurid in this image, making us wonder if the maid has to keep the door locked to thwart the advances of the King of Spades. As we’ve already seen in “Luka,” terrible things can happen behind locked doors. But that’s not really the vibe I get from “Chambermaid.” Maybe Vega is instead suggesting an image for privacy, a woman writer like Virginia Woolf who needs a room of her own. Thinking along these lines, Vega’s lock imagery seems to anticipate the sixth track on the album, “Lucinda,” with an allusion to Lu’s great song “Changed the Locks.”

I changed the locks on my front door

So you can’t see me anymore

And you can’t come inside my house

And you can’t lie down on my couch

I changed the locks on my front door

The bridge of “Chambermaid” is particularly interesting:

You want to know did I ever steal?

He never leaves anything out that’s real

I took nothing he would miss

But only once I stole a kiss

The chambermaid dodges the question about whether she ever stole anything from the great man, insisting that she never took anything he’d miss. What a Dylanesque evasion. This is deliciously ironic coming from a song that “borrows” so frequently and so freely from “I Want You” and other Dylan songs.

In the third verse the chambermaid dreams of rising above her status:

I used to pretend that I was queen

But over time I quit that scene

Costs too much to even dream

In that direction

Vega has plenty of Dylan queens to choose from. Along with the Queen of Spades in “I Want You,” there’s Queen Jane in “Queen Jane Approximately,” Queen Mary in “Just Like a Woman,” the Queen of Swords in “Changing of the Guards,” and many others—“All the old queens from all my past lives,” as he sings in “I Contain Multitudes.”

But Vega doesn’t have to depend upon Dylan for regal references. Her own oeuvre is full of queens, from the medieval ballad “The Queen and the Soldier” on her debut album, to her Tarot-based 2014 album Tales from the Realm of the Queen of Pentacles. Vega melts easily into the roles of both chambermaid and queen, alternating from one to the other, like a modern-day Cinderella before and after the stroke of midnight.

She concludes the third verse with these lines:

I think of comfort and of peace

I long for pleasure and release

Oh, how I wish the din would cease

I could do with some protection

I suspect that she’s subtly alluding to the prisoner seeking protection and release in Dylan’s “I Shall Be Released”:

They say ev’ry man needs protection

They say ev’ry man must fall

Yet I swear I see my reflection

Some place so high above this wall

I see my light come shining

From the west unto the east

Any day now, any day now

I shall be released

The fourth and final verse begins the same as the first, but then Vega gives us this clever twist at the end:

He often gives me sage advice

When I dream of him at night

He slips his pen into my hand

And says, “Don’t forget to write”

This is a wonderful image for muse-inspired art. The chambermaid depicts her hand as guided by her predecessor, as if he is working through her to help create new art. “Chambermaid” is the ultimate proof of this creative process, as Vega channels Dylan to create a song deeply indebted to him but also uniquely her own.

The chambermaid claims that “the great man” visits her in dreams. Apparently, Vega is also sometimes visited by her muses in dreams. As she recently told Shaun Curran of The i Paper, “I dream of certain people frequently. I dream about Bob Dylan. I used to dream about Sinead O’Connor back in the 90s. I dream about Lou Reed a lot. I don’t know why these people show up in my dreams, but I know there’s some sort of communion going on there.” In her interview for What Difference Does It Make?: 80s Music Podcast, Vega revealed that the inspiration for “Chambermaid” actually came from dreaming:

I guess it was an unconscious wish to break through this writer’s block. I had this dream, and I don’t even remember what the dream was, and I woke up with this thought in my mind: I’m Bob Dylan’s Chambermaid. And then I heard the song “I Want You” in the back. I thought, whoa, that was really interesting. So I came into my office and I thought, “Let’s go down this rabbit hole for an hour or so and see where it leads me.” I could see the room so clearly in my mind, this room that she was cleaning that belongs to Bob, but he’s not in the room. A lot of the details of her life are mine.

But here is the most thrilling and uncanny part of the inspiration for “Chambermaid”:

There’s this whole idea of stealing. Like does she steal from him? No, she doesn’t steal from him, except this kiss. And then at the end, in her dreams, he gives her this pen and says, “Don’t forget to write.” That line was actually from a different dream with Lou Reed. I thought it was witty, so I used it as the final line of the Bob Dylan song.

I love this story so much! It sheds light on the alchemy of art, where the muses speak to the artist, and to each other, in the language of dreams and songs. It’s the responsibility of the artist to be open, vigilant, and prepared to receive the gift, whenever and however it arrives, and to transcribe the dialogue faithfully.

Vega’s independent record label is called Amanuensis Productions. I can never hear that word without thinking of a funny anecdote from Elvis Costello’s memoir Unfaithful Music & Disappearing Ink. Costello played a few shows with Dylan in October 2007. At one point, Dylan stopped by Costello’s tour bus and saw him working on a score for Twyla Tharp. The next time they crossed paths, Dylan brought up the topic again:

Bob said something sarcastic like “How’s that symphony going?” but then got sort of serious and said that he might want to write down some of his musical ideas one day.

I said all he needed was someone to transcribe them.

Only, I didn’t use the word “transcriber,” I used the fancy term “amanuensis.”

“Amanuensis! Amanuensis!” Now Bob was up on his toes and punching me in the arm. “I can’t believe you used ‘amanuensis’ is a sentence. You could ask twenty people and they wouldn’t know what ‘amanuensis’ meant.” (Costello 554-55)

Well, Vega knows what it means. In her conversation with Richard Julian for Grooveable Feast, she explained why she chose that name:

An amanuensis is a scribe. It’s someone who takes dictation. Basically, it’s like an old-fashioned word for a secretary. Amanuensis to me sounds really beautiful because when I write a song, and I’m in the flow of writing, sometimes it feels like I’m receiving dictation from some other source, some larger source. So I have a little logo with a sort of quill pen and my glasses and I’m taking it all down. I kind of liked it because a scribe was usually a servant back in the day. I thought it was very clever because, by establishing Amanuensis Productions, I get to own the masters. So I thought it was kind of funny because the servant gets to own the masters.

The dynamic she describes here perfectly captures the relationship between the chambermaid and the so-called great man. More broadly, it speaks to Suzanne Vega’s brilliant intertextual duets with Leonard Cohen, Lou Reed, and Bob Dylan, where the servant becomes the master.

Works Cited

Cohen, Leonard. Live Songs. Columbia, 1973

---. Songs from a Room. Columbia, 1969.

---. Various Positions. Columbia, 1984.

Costello, Elvis. Unfaithful Music & Disappearing Ink. Blue Rider Press, 2015.

Curran, Shaun. “Suzanne Vega: ‘I was the first woman to headline Glastonbury – I had to wear a bulletproof vest.’” The i Paper (9 May 2025), https://inews.co.uk/culture/music/suzanne-vega-first-woman-headlined-glastonbury-bulletproof-vest-3676363.

Dylan, Bob. Official Song Lyrics. The Official Bob Dylan Website.

https://www.bobdylan.com/.

Grooveable Feast. “Episode 1: Suzanne Vega (Pt. 1).” YouTube (21 October 2010),

.

Hermes, Will. Lou Reed: The King of New York. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2023.

Hilburn, Robert. “Rock’s Enigmatic Poet Opens a Long-Private Door.” Los Angeles Times (4 April 2004). In Every Mind Polluting Word: Assorted Bob Dylan Utterances, ed. Artur Jarosinski (Don’t Ya Tell Henry, 2006), 1337-43.

McCabe, Allyson. “Late Nite Radio #1: Suzanne Vega.” Oldster (24 April 2025),

.

Reed, Lou. Berlin. RCA Victor, 1973.

Rose, Charlie. “Time Out of Mind.” Charlie Rose (10 October 1997), https://charlierose.com/videos/13881.

Unze, Adam. “Suzanne Vega.” The Spark Parade (23 April 2025), https://www.thesparkparade.com/episodes/2025/4/25/suzanne-vega?rq=suzanne%20vega.

Vega, Suzanne. 99.9 F. A&M, 1992.

---. “The Ballad of Henry Timrod.” New York Times (17 September 2006), https://www.nytimes.com/2006/09/17/opinion/the-ballad-of-henry-timrod.html.

---. Flying with Angels. Cooking Vinyl, 2025.

---. “Leonard Cohen Interviews Suzanne Vega.” The Passionate Eye: The Collected Writing of Suzanne Vega. Avon Books, 1999, 85-117.

---. Lou Reed: Rock and Roll Heart. American Masters Digital Archive (12 July 1997), https://www.pbs.org/wnet/americanmasters/archive/interview/suzanne-vega/.

---. Solitude Standing. A&M, 1987.

---. “Suzanne Vega Remembers Her Friend Lou Reed.” The Times (2 November 2013), https://www.thetimes.com/world/us-world/article/suzanne-vega-remembers-her-friend-lou-reed-0xr95db5z99.

---. “Women on Bob Dylan.” The Guardian (16 October 2016), https://www.theguardian.com/music/2016/oct/16/women-artists-on-bob-dylan-nobel-prize.

What Difference Does It Make?: 80s Music Podcast. “Suzanne Vega, Chambermaid, and Bob Dylan.” YouTube (5 May 2025),

.

Great insights. Good writing. Thanks.

This is really great and a very interesting concept. Great stuff.