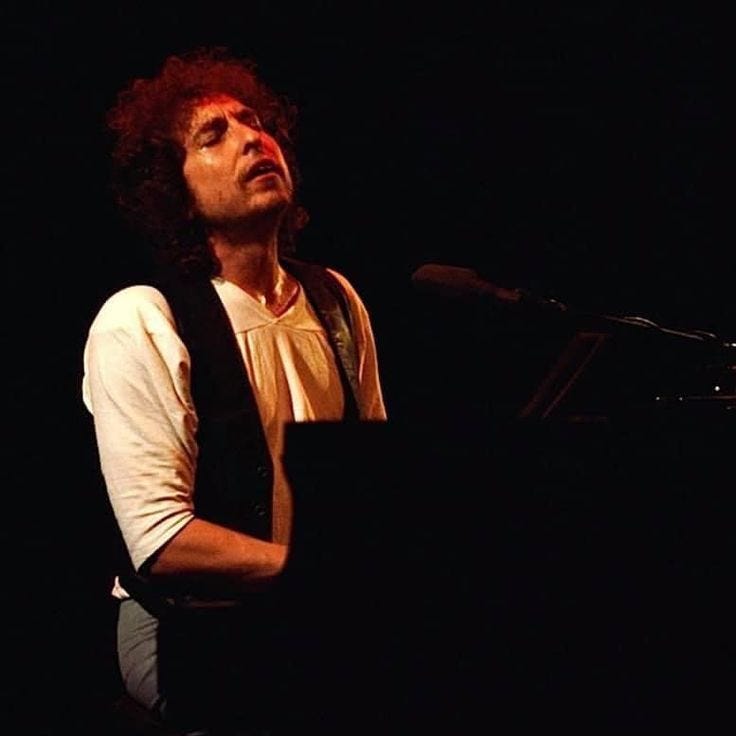

Dylan in Cincinnati: 2021 & 2023

Rough and Rowdy Ways Tour, Part 2

Laura Tenschert and Ray Padgett recently sat down for a recorded chat before the (supposed) final concert of the Rough and Rowdy Ways Tour. Reflecting back on the first RARW concert in Milwaukee in 2021, Ray tried to express the momentousness of the occasion:

There was a period, this seems like ancient history, but you didn’t know if Bob was going to tour again. You didn’t know if there were going to be tours again. Everything was—for the first time, my life was up for grabs, up in the air. And so being in that room, with those people, seeing him do these songs—nothing, nothing—no matter how good the show tonight is—nothing is going to top that emotionally for me.

I saw Dylan a week later in Cincinnati, and I completely agree with Ray. The first leg of the RARW Tour was unlike any other Dylan concert experience before or since, and that’s largely because of what we brought with us into the room.

In my first installment on the RARW concerts in Cincinnati, I frequently described the 2023 performances at the Brady Music Center as superior to those at the Aronoff Center in 2021. From a strictly musical standpoint, I think that’s fair. With time, practice, collaboration, and ingenuity, the band became much more proficient at playing these songs. However, as I’ve stressed throughout this series on Dylan in Cincinnati, concerts take place within contexts—where and when a performance takes place matters. These contexts make a huge impact on how songs are performed by artists and received by local audiences.

The ticket sales will tell you that about 2,500 masked and vaccinated concertgoers attended the Aronoff show, and about 4,500 attended the sold-out Brady show two years later. But those figures are misleading. They fail to account for all the ghosts in the room in 2021.

Dylan displayed a special talent for summoning up spirits on the RARW Tour, and those powers were especially potent on the first leg. You think you’re attending a concert, then he starts singing “Key West (Philosopher Pirate)” and “I’ve Made Up My Mind to Give Myself to You” and suddenly you find yourself at a séance. Dylan shook the dead from their slumber and set them swirling around like the room like a spectral snow globe.

Oh. I get it now. This. This is why he’s here.

The pandemic ended the Never Ending Tour, and Dylan could have taken this as a long-deferred sign from the universe to lay his burden down and retire. But then that dying voice within him started reaching out again, giving him new songs when the time was right, songs he needed to play, songs we needed to hear, “written in my soul from me to you.” These were messages that couldn’t be entrusted to the unreliable mediation of vinyl, tape, CD, or streaming services: they needed to be delivered in person. So he dusted off his walking shoes and headed down the road again. Guess the universe has other plans. Cincinnati here I come!

“Early Roman Kings” / “Crossing the Rubicon”

The first half of the 2021 and 2023 shows featured identical song selections. The first departure comes in the ninth spot of the setlist. In Fall 2021, that slot was occupied by “Early Roman Kings,” an old chestnut that Dylan had been trotting out regularly ever since its release on Tempest (2012). Like “Silvio,” that staple of the early NET years, “Early Roman Kings” is a song that fans wearied of long before Dylan did.

He must enjoy playing it, most nights, but that joy doesn’t really come across at the Aronoff. The energy is much lower in this rendition than in previous Cincinnati performances. The pace is slower than it needs to be, giving the song a plodding quality.

To be fair, the Aronoff audience doesn’t give him much to work with on this one. ERK depends upon a call-and-response connection with the fans. Unfortunately, Dylan only receives muted indifference from the Cincinnati crowd, taking a mid-concert siesta on this forgettable number. “If you see me coming and you’re standing there / Wave your handkerchief in the air.” Nope. Maybe some white flags of surrender waving on this one, but no Elvis-drenched hankies. “I ain’t dead yet, my bell still rings.” He’s ring-ring-ringin’ but ain’t nobody opening the door.

I was glad when Dylan replaced this Roman song in the 2023 setlist with an altogether stronger Roman song, “Crossing the Rubicon.” Julius Caesar has been much on Dylan’s mind of late, as Richard Thomas observes in his RARW album review for The Dylan Review. The Roman leader gets explicitly mentioned in “My Own Version of You”: “I pick a number between one and two / And I ask myself what Julius Caesar would do.” The title conceit of “Crossing the Rubicon” refers to Caesar’s fateful decision to cross the Rubicon River in northern Italy, effectively launching a civil war that would end the Roman Republic, usher in his dictatorship, and eventually lead to his murder in the Senate.

The band slinks into a sultry groove on “Crossing the Rubicon” at the Brady. It’s a slow burn, and they take their time heating up. Dylan takes long drags and exhales the blues in his vocals. His piano and Donnie’s steel guitar work in tandem to transform the Brady into a late-night juke joint.

After a languid, unhurried pace for the first half of the song, Dylan suddenly inserts a flamboyant flourish in the middle. At the 4:48 mark he starts pounding the keys with such ferocity that you’d think he was performing CPR on the piano. I hear this turbulence as the musical equivalent of crossing the Rubicon, as if Dylan and his comrades are following the footsteps of Caesar’s army as they splash across the caesura of the song. They’re marchin’ to the city, and the road ain’t long.

Some of the lyrics to “Crossing the Rubicon” are revised from the album. Consider this violent new verse:

Right or wrong, what can I say – what really needs to be said

I’ll spill your brains out on the ground – you’d be better off over there with the dead

Seen my time, maybe twenty years I been gone

I stood between heaven and earth, and I crossed the Rubicon

The singer threatens to send his enemies to the underworld, but he is headed that same direction. Having crossed the threshold of the Rubicon, the next border crossing lies just ahead on the horizon, passing from life, through death, into the afterlife.

For what it’s worth, this new verse seems to echo the song it replaced in concert. Compare “I’ll spill your brains out on the ground – you’d be better off over there with the dead” to “Early Roman Kings”: “I’ll strip you of life, strip you of breath / Ship you down to the house of death.” So many of the main characters in the RARW setlist issue overt or covert threats of violence. They pay in blood, but not their own.

“To Be Alone with You”

In my previous post, I argued that “I’ll Be Your Baby Tonight” is transformed into a murder ballad by virtue (or vice) of its positioning in the setlist, without requiring any substantial lyrical changes. Dylan goes much further to explicitly reimagine “To Be Alone with You” as a murder ballad. In its original form on Nashville Skyline (1969), it was an unequivocal love song. Not anymore. He first rewrote the lyrics for Shadow Kingdom, turning this honey-dripper into blood-curdler. You do not want to be alone with the singer of “To Be Alone with You.”

This crooner seems gentle enough at first. But when the full moon rises, he turns into a werewolf: “Well, I’ll hound you to death, that’s just what I’ll do / I won’t sleep a wink ’til I’m alone with you.” He is a fiend out of control: “Oh, what happened to me, darling? What was it you saw? / Did I kill somebody? Did I escape from the law?” He has evil in his heart and a malicious glint in his eye: “Well, my heart’s in my mouth, my eyes are still blue / My mortal bliss is to be alone with you.”

Diabolical for sure, though I can’t help but admire that clever line, “My eyes are still blue.” It serves simultaneously as a self-allusion [“Oh, where have you been, my blue-eyed son?” from “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall”] and as an allusion to Hank Williams’s “Why Don’t You Love Me (Like You Used to Do)” [“My hair’s still curly and my eyes are still blue / Why don’t you love me like you used to do”]. Earlier he sings, “They say night time is the right time,” another musical allusion, this time to Ray Charles’s “Night Time Is the Right Time.” The guy in this song is part Jack the Ripper and part Wolfman Jack. He uses love songs—his own and those of others—as bait to lure in his victims.

The singer has accomplices. At the Aronoff the band gives the stalker-singer a boost when his energies begin to flag. There’s an extended jam before the final verse where the band sounds tighter than at any point since “False Prophet.”

Britt and Lancio’s guitars are often kept on a short leash in the RARW songs. But on “To Be Alone with You” they are finally let loose, and it inspires Dylan toward a more forceful delivery in the final verse. It’s the musical equivalent of Dennis Hopper huffing poppers in Blue Velvet to fuel his creepy quest for Isabella Rossellini.

How ironic that, in a song about being alone, Dylan and his henchmen sound more together on “To Be Alone with You” than they have for much of the evening at the Aronoff.

The Brady performance rocks even harder. During a pause before the song begins, a fan yells out “We love you, Bob!” and others chime in with their agreement. Well, get ready to love him even more after this kick-ass “To Be Alone with You.”

The singer is a man on a mission, in hot pursuit of a woman who got away once but won’t elude him this time. The lyrics say he wants to be alone with her, but the clamorous musical accompaniment sends different signals. There’s a whole pack of hellhounds on her trail, howling and barking and raisin’ a ruckus.

The Aronoff performance was uneven, but at the Brady they’re in complete command from start to finish. Dylan leads the way with his piano, which sounds amazing! I’ve never heard him play the instrument with such unbridled delight. The whole band rises to his level and matches his zeal. We’re hearing this team play at the very top of their game, and we’re cheering like we’re next door watching the Bengals on a game-winning drive.

At the end of the song, Dylan acknowledges the warm response, “Why, thank you!” He knows they just nailed it. Woke ’em up with that one, eh boys?

In retrospect, I can appreciate something I didn’t notice at the time. “To Be Alone with You” is the end of something. Several songs in the RARW setlist have a sinister bent, providing a dramatic platform for macabre characters who growl threats as they stalk their quarry. Dark songs for dark times. But that’s only a part of the narrative.

Dylan guides us along a musical journey that passes through darkness but doesn’t end there. Having made the descent into the underworld and spent a season in hell, he charts a different course for the final trajectory of the dramatic arc. As you’ve figured out by now, the man knows how to construct a dramaturgically effective setlist. You can feel the wind shift as Dylan points his prow toward “Key West,” one of the most incandescent songs he’s ever written.

“Key West (Philosopher Pirate)”

The pulsing heart of the RARW setlist is the three-song sequence “Key West (Philosopher Pirate),” “Gotta Serve Somebody,” and “I’ve Made Up My Mind to Give Myself to You.” The first one really hit me hard the first time I heard it live. This beautiful meditation on mortality and immortality, passing over into “paradise divine,” had the tears rolling onto my mask. I was thinking mostly about my mother, who died of Covid earlier that year. But I was also conscious of being surrounded by others in the room going through the same experience, thinking of lost loved ones, communing with ghosts. Donnie Herron’s accordion sets the mood, and Dylan’s voice couldn’t be more moving. “I’m so deep in love I can hardly see.” Me too.

I’ve listened repeatedly to the bootleg, and whenever he delivers the line “Some people say that I’m truly blessed,” it breaks me up every time. There’s also a recurring guitar part, a descending five-note motif played by that Bob Britt, that I find enthralling. It’s the musical key to unlocking my heart in “Key West.” I was proud to learn from Tim Edgeworth that this signature guitar line made its first ever appearance in RARW concert #6 at Cincinnati.

Dylan has written a number of songs set in mythical realms. Even when they are modeled after real places, he elevates them into something grander. Think of the North Country, Desolation Row, the Lowlands, the Highlands, Mississippi, and now Key West. He turns the southernmost point of the U.S. into a metaphysical borderland, a liminal zone where life and death converge.

Listeners have noted the recurrence of assassinated leaders on Rough and Rowdy Ways: Julius Caesar, William McKinley, John F. Kennedy, Martin Luther King. “Key West” opens at McKinley’s deathbed: “McKinley hollered – McKinley squalled / Doctor said McKinley – death is on the wall / Say it to me if you got something to confess.”

President McKinley was shot in 1901, before radios were common and before the advent of broadcast news. Dylan is apparently referring to a radio listener years later hearing the song “White House Blues” by Charlie Poole and the North Carolina Ramblers, which begins: “McKinley hollered, McKinley squalled.” The source is unmistakable. “Roosevelt in the White House, he’s doing his best / McKinley in the graveyard, he’s taking his rest.” As Jim Salvucci observes in The Dylan Review,

Poole’s song cleverly tells the story not of McKinley’s life and assassination but of his final days lingering with the fatal consequences of two bullet wounds. Thus, when Dylan’s narrator states, “I heard all about it – he was going down slow / Heard it on the wireless radio,” he is not referring to the breaking news of McKinley’s murder but to hearing the song “White House Blues” itself playing on the radio.

Being a President from Ohio can be hazardous to one’s health. Three of them have died in office: Warren Harding died of a heart attack in 1923, William McKinley was shot in 1901, and James Garfield was shot in 1881. As a Civil War aficionado, Dylan probably knows that McKinley was the last veteran from that war to serve as President. Three nights before the Aronoff concert, Dylan played his only RARW show in Columbus. McKinley served two terms as Governor of Ohio, and his monument stands before the Ohio Statehouse in Columbus.

While we’re on the subject of murdered leaders, the U.S. President assassinated prior to McKinley was James Garfield, also from Ohio. There is a large statue of Garfield in downtown Cincinnati, only three blocks away from the Aronoff Center.

Everywhere one turned in 2021—outside the Aronoff and inside it—the shadow of death was lurking.

The Brady arrangement of “Key West” is strikingly different than the Aronoff. Once again, there’s just a lot more going on musically by 2023. Dylan is much busier at the keyboard, and though it sometimes sounds like noodling, at other times he finds a rhythm that he and his ensemble can work with. Britt and Herron in particular add a lot of sonic variety to “Key West.”

It’s a profound song lyrically, and that’s what Dylan highlighted at the Aronoff. Nothing wrong with that: it landed perfectly and was exactly what we needed to hear at the time. In the interim, however, after playing it scores of times around the globe, Dylan connected with “Key West” not just as a testament but as a song. Listen to the Aronoff version and you’ll hear a moving oration with musical accompaniment. Listen to the Brady version and you’ll hear a well-rehearsed band playing a damn fine song.

The most poignant moment in the Brady “Key West” was non-verbal. At the very end, Dylan plays the loveliest piano part. I’m glad that the audience had the collective good sense to keep quiet rather than drown it out with hooting and clapping. He utters the final line—“Key West is on the horizon line”—and then the other musicians go quiet, all except for Dylan on piano and Pentecost on hi-hat. Then the drummer fades away, too. Dylan’s playing slows down, and the melody begins to fall apart into disparate notes before concluding with a final flourish and a return of cymbals. The effect is entirely musical and yet visually evocative.

The image I get is of the singer walking toward the setting sun, leaving the land of light and joining the light itself, shedding his body to merge with the celestial. First the words cease, then the instruments peel away, then the solitary piano disintegrates into silence. The lyrics have prepared the way for this transition, but the music completes it. I shall be released.

“Gotta Serve Somebody”

The Aronoff “Gotta Serve Somebody” crackles and sparks with electricity. Dylan the dramatist recognizes the need to break up his more somber songs with up-tempo numbers. Between the head-bowing “Key West” and the heart-wringing “I’ve Made Up My Mind to Give Myself to You,” he gives us the hip-shaking “Gotta Serve Somebody.” This is the hardest rocker of the evening, and it sounds fantastic. Drayton finally gets to bang the hell out of his kit, and the guitarists crank up the volume after laying low in the last number.

“Gotta Serve Somebody” holds a place of distinction for Dylan. It’s the first track on his first born-again Christian album Slow Train Coming (1979). He gave it pride of place as concert opener during his gospel tours. And he won his first Grammy for performing this song. But it remained in his setlists for years because it’s such a dependably uplifting song to play live.

At the Brady in 2023, “Gotta Serve Somebody” successfully defends its hard rock title. The arrangement is somewhat different, downshifting during the verses so that Dylan’s voice doesn’t have to compete with the band at top volume. But in between verses every musician plays his instrument like he’s detonating a bomb.

Pentecost pounds harder than anyone on Dylan’s stage since George Receli. Britt, Lancio, and Garnier shred like they’re auditioning for the Ramones, while Dylan channels Jerry Lee Lewis circa 1957. He serves the Lord, yes, but this is Friday night, not Sunday morning—and there’s a whole lotta shakin’ goin’ on at the Brady on “Gotta Serve Somebody.”

“I’ve Made Up My Mind to Give Myself to You”

Many listeners have noted that the “You” in “I Made Up My Mind to Give Myself to You” could refer to God. But when Dylan sings it live, there’s no doubt that he’s referring to us: his live audience. He is declaring his devotion, renewing his vows, and so are we. You could really feel the love in the room throughout the RARW Tour during this song.

As with “Key West,” the pandemic context makes “I’ve Made Up My Mind” extra powerful. The crowd is more vocal in this performance than any other so far. We are reverential while Dylan is singing, not wanting to miss a word. But there are lots of ecstatic yelps at the end of each verse because what we’re hearing is just so-so-so good.

The emotions really welled up for me when he sang, “A lot of people goooooone, a lot of people I knew.” Dylan is giving voice to the unresolved grief in the room, but he’s also offering a deeply life-affirming commitment.

I’ve traveled all over from the mountains to the sea

I hope the gods go easy with me

I knew you’d say yeeeeeeesssssss – I’m saying it too

I’ve made up my mind to give myself to you

I’m saying it, too. In the days following the Aronoff concert, I made up my mind to write this book for you, Bob.

Fortunately, the traumatic conditions that prevailed in 2021 had improved significantly by 2023. Unfortunately, I can’t say the same for Dylan’s performance of “I’ve Made Up My Mind.”

The arrangement really hadn’t evolved much since 2021, and maybe that’s why Dylan’s relationship with the song didn’t sound as fresh and urgent in 2023. The performer and the audience felt so in tune with each other the first time, and the connection just wasn’t as strong the second time. Ah well. That’s how it goes with long-term relationships, right? For better or for worse, in sickness and in health, until death do us part.

Slot #14 was typically reserved for standards from the American Song Book. Dylan chose “Melancholy Mood” for the Aronoff and “That Old Black Magic” for the Brady, songs he previously covered on Fallen Angels (2016). The performances are serviceable, and the interplay between Bob’s piano and Tony’s standup bass is particularly good on “That Old Black Magic.” But it’s hard to regard these tunes as anything more than appetizers before the final feast.

“South of Cincinnati”

Now we come to the most memorable moment of the 2023 concert, and probably my favorite single performance Dylan has ever delivered in Cincinnati. I’m all about context, so let me first situate this song in time and place.

As the RARW Tour stretched its legs, Dylan began introducing wildcard covers in his setlists. His selections initially leaned heavily upon the Grateful Dead and Dead-adjacent songs. During the fall of 2023, he expanded his repertoire with city-specific songs. For instance, he opened the first show in Kansas City with “Kansas City.” In St. Louis, he opened with “Johnny B. Goode” and closed with “Nadine,” both by native son Chuck Berry. He drew from the deep well of Chicago blues, opening in the Windy City with “Born in Chicago” and closing with “Forty Days and Forty Nights.” In Indianapolis he covered “Longest Days” by Hoosier hero John Mellencamp. But he didn’t follow the pattern every night, so you never knew what (if anything) you were going to get.

I followed these developments with growing anticipation, hoping he’d play a Cincinnati-flavored cover and speculating what it might be. Before introducing the band at the Aronoff in 2021, Dylan told the audience: “Thank you everybody. Nice to be here in Cincinnati. Home of King Records, one of the best labels ever really.” Would he play a King song for the Queen City? Maybe “Blues Stay Away from Me” by The Delmore Brothers? Or “Fever” by Little Willie John? Dylan’s beloved Hank Williams recorded some of his hits at Herzog Studios in Cincinnati. Might he grace us with “Lovesick Blues” or “I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry”?

I started to get excited after “That Old Black Magic” when I saw Dylan shuffling papers at the piano. Long gone were the cheat-sheets from the Aronoff, when he still needed prompts to remember the words to RARW songs. If he’s not ready to play “Mother of Muses,” then what’s he got up his sleeve? The mystery was soon revealed, and it was breathtaking.

If you ever get south of Cincinnati

Down where the dogwood trees grow

If you ever get south of the Mason Dixon

To the home you left so long ago

If you ever get south of the Ohio River

Down where Dixieland begins

If you ever get south of Cincinnati

I’ll be yours again

Listening to it again still gives me chills. Hearing the words “Cincinnati” and “the Ohio River” coming out of Bob Dylan’s mouth—while he’s on a stage in Cincinnati, only a stone’s throw from the Ohio River—just about makes me want to burst into tears of gratitude.

I didn’t recognize the song when I first heard it. Dylan concerts are now phone-free experiences, so the Yondr pouch prevented me from looking up details. I was trying to be fully present and bask in the glory of this hometown homage, but part of my mind kept scanning for clues. Who is this by? Cincinnati, Ohio River, Mason Dixon, Dixieland—oh wait, it must be Stephen Foster!

Dylan has covered Foster before, most memorably with his touching “Hard Times” on Good as I Been to You (1992). As I’ve written previously in Shadow Chasing, Dylan knows Foster’s work well. He claims the so-called “Father of American Music” as an artistic ancestor, and in The Philosophy of Modern Song he acknowledges the songwriter’s staying power. Dylan’s interview with Jeff Slate slyly reveals that’s he’s aware of Foster’s Cincinnati roots, where he penned some of his best-known songs like “Oh! Susanna” and “Nelly Was a Lady.” Even after Foster left the Ohio-Kentucky borderland, the region didn’t leave his imagination, as evidenced by “My Old Kentucky Home.” Listen to the state song of Kentucky and you’ll hear Foster crossing the same terrain as “South of Cincinnati.”

It turns out that a native Kentuckian wrote “South of Cincinnati.” The first thing I did after the concert was look up the song and discover that it’s from Dwight Yoakam’s debut studio album Guitars, Cadillacs, Etc., Etc. (1986). In his biography Dwight Yoakam: A Thousand Miles from Nowhere, Don McLeese labels “South of Cincinnati” as a “border song” and provides this effective description:

He sings the chorus from the perspective of a young woman whose boyfriend had left her to go north some fourteen years ago. She’s been waiting, perhaps without hope, for his return ever since. Even if he’d asked, she wouldn’t join him up there. For her, Kentucky is home. But if he ever decides to come back to his roots, she’ll be there for him. Biographically, Yoakam is the guy who left, but the conviction he brings to the sentiments of the song suggests that he knows Ohio can never be home in the way Kentucky was. (73)

“South of Cincinnati” sounds like a song Stephen Foster could have written, but it also sounds like a song Bob Dylan could have written. As a singer, Dylan invests the same yearning in “South of Cincinnati” that he expresses in his own best border songs about separation and loss, from “Girl from the North Country” and “Boots of Spanish Leather” to “If You See Her, Say Hello” and “Red River Shore.”

Dammit, there goes Dylan making me cry again! But I couldn’t help it. The artist I love most was giving the city I love most a precious gift—To Cincinnati, Love Bob. He had never played this song before in concert. I wish I could report that he never played it again, but in fact he regifted the song the next night in Akron. Alas! But in the moment, it was a singular treasure presented only for us in the room. By the following day, a contraband recording had leaked out on YouTube, and soon after a full bootleg of the concert was posted on Expecting Rain. Of course, my study depends upon these bootlegs, so I’m happy that the world gets to share the wealth. That said, I also loved those blissful few hours, before the pirate recordings and before two-timing Akron, when “South of Cincinnati” was a private bond shared only by Dylan’s band and 4,500 adoring fans at the Brady.

Had I understood what Dylan mumbled to the crowd after playing this special song, it would have saved me some googling. Now with the help of the bootleg I can make it out: “Thank you! Dwight wrote that. You know that. I think he wrote it for King Records that used to be here.” Of course, he didn’t write it for the long-defunct Cincinnati label, but it would have felt right at home in their discography, and it gives Dylan an excuse for one more local shout-out.

The King Records quip may not be random. As a dedicated student of American music, Dylan knows that King’s secret sauce was its eclectic mixture of musical styles, ranging from R&B and soul to country and bluegrass. This unusual combination is directly attributable to the studio’s location in Cincinnati, a popular destination or way station for both African American and Appalachian refugees during the Great Migration, looking for steady work in the industrial North and/or fleeing racial discrimination in the South.

“South of Cincinnati” personalizes these larger historical and socioeconomic phenomena. Dwight Yoakam didn’t need a professor or a textbook to teach him about the Great Migration. As McLeese notes, “The most important lesson kids learned in the schools of Pike County was that they needed to leave it far behind if they hoped for something better from life than a coal coffin” (21). Yoakam’s family moved from Kentucky to Ohio before he was two years old. For young Dwight, the challenge became how to get back down south. “He was a reasonably happy kid in a reasonably happy household. But the family missed Kentucky and had close ties to relatives there, so practically every Friday they’d pack up the car, hit the road, and travel south to Pikeville. Whenever they talked about ‘goin’ home,’ it was understood that ‘home’ meant Pike County” (22). Later in life, Yoakam used music as his road home.

The transplanted songwriter knows his song well before he starts singing. Those family trips back and forth from Columbus to Pikeville took the Yoakams repeatedly across the Ohio River—their Rubicon separating Kentucky and Ohio, South and North, Past and Present. Yoakam dramatizes the gulf separating the Southern woman, writing letters she’ll never send, from the Northern exile, sulking on a lonely Chicago barstool and longing for home. Dylan has been crisscrossing this territory his entire career. “South of Cincinnati” might just as well be called “Crossing the Ohio” or “Interstate 71 Revisited” or “Stuck Inside Chicago with the Pikeville Blues Again.”

“Mother of Muses”

I have come to think of the final three songs as the Prayer Trilogy. Dylan begins with “Mother of Muses,” a pantheistic prayer that invokes Mnemosyne (the goddess of memory and the mother of the muses), her daughter Calliope (the muse of epic poetry), and by extension Orpheus, son of Calliope and the greatest musician in ancient Greek mythology. He follows with a tribute to one of the deities of American music, Jimmy Reed, a guiding spirit for the electric blues. He then closes the concert with an overtly Christian hymn, “Every Grain of Sand,” which is part backward-looking confession and part forward-looking benediction.

“Mother of Muses” didn’t really do much for me when I first heard it on the RARW album. Dylan’s delivery struck me as too morose, and the lyrics were a little too white-savior-y for my tastes. Who would have expected the author of “John Brown,” “Masters of War,” and “Only a Pawn in Their Game” to be crediting all these white generals for making possible the accomplishments of Martin Luther King?

I am more intrigued by Dylan’s classical allusions. The opening line, “Mother of Muses sing for me” picks up right where he left off in the Nobel Lecture, invoking divine inspiration just as Homer does at the beginning of The Odyssey. In that regard, the song is a fascinating reflection on creation and legacy, concerns weighing heavily on Dylan’s mind in the years following his Nobel Prize in Literature. Laura Tenschert has wonderful meditations on this topic on Definitely Dylan, as does Richard Thomas in Why Bob Dylan Matters, and I’ve written about it myself on Shadow Chasing for my Underworld series.

Certain lines in performance really hit home at the Aronoff. I was particularly struck by Dylan’s final utterance: “I’m traveling light, and I’m slow coming hooooome.” What a powerful statement from an artist in his eighties, leaving it all on stage before crossing over to his final destination in the sweet by and by.

When he says he’s slow coming home, he ain’t kiddin’—this song is reaaalllly slooooowww. Honestly it would be fine with me if he sped it up. I’m not expecting “Like a Rolling Stone,” but I could have gone for an arrangement that gathered less moss than this slow-roller. “Mother of Mosses”? That’s basically my impression from the Aronoff.

The arrangement isn’t that different at the Brady, but my attitude toward “Mother of Muses” had improved by then. I was finally ready to receive the song as the prayer it was always meant to be.

Most of the emphasis is on Dylan’s voice and piano. If anything, the 2023 delivery is even slower than 2021. However, there is a nice musical interlude at the Brady, making space for the guitarists to stick their oars into these deep waters. Now I visualize Odysseus landing in Ithaca, disembarking on the shore, and climbing the final steps toward his long-awaited homecoming.

“Goodbye Jimmy Reed”

“Goodbye Jimmy Reed” serves multiple functions in the RARW setlist. It’s a musical commemoration in the vein of “Song to Woody” and “Blind Willie McTell.” It’s also a farewell: the song title and refrain literally say “goodbye.” But let’s not lose sight of the fact that, in performance, it’s a bluesy rocker. After the glacially slow “Mother of Muses,” the bandleader recognizes the need to warm the audience back up. Sounds like a job for Jimmy Reed.

The heat pulsing from “Goodbye Jimmy Reed” at the Aronoff is from the revival tent.

Dylan testifies that listening to Jimmy Reed is a religious experience. He opens, “I live on a street named after a saint / Women in the churches wear powder and paint / Where the Jews and the Catholics and the Muslims all pray.” But Dylan doesn’t need a synagogue, cathedral, or mosque to worship—the Aronoff or the Brady will do just fine. “Goodbye Jimmy Reed – Jimmy Reed indeed / Give me that old time religion, it’s just what I need.”

At this point in his life, there’s no meaningful distinction for Dylan between singing and praying. They’re all psalms. As he told Jon Pareles, “Those old songs are my lexicon and my prayer book. […] You can find all my philosophy in those old songs. I believe in a God of time and space, but if people ask me about that, my impulse is to point them back toward those songs.” The stage is his church, and Jimmy Reed is his Lord’s Prayer.

For thine is the kingdom, the power and the glory

Go tell it on the mountain, go tell the real story

Tell it in that straight forward puritanical tone

In the mystical hours when a person’s alone

Goodbye Jimmy Reed – Godspeed

Thump on the Bible – proclaim the creed

The arrangement of “Goodbye Jimmy Reed” is quite different at the Brady. The Aronoff version had a hallelujah gospel vibe. The Brady version moves the song into the honky-tonk. It’s a different kind of prayer, but no less fervent.

This performance features some of Dylan’s best barroom piano playing of the night. By the end he wriggles into a great groove with the Tony & Jerry rhythm section. Ray Padgett picked up on an echo I missed: “Blues fans noticed it seemed to be based on ‘Big Boss Man’ by—well wouldn’t ya know it—Jimmy Reed himself! I guess now it’s ‘Hello, Jimmy Reed.’” The Holy Ghost of Jimmy Reed would be well pleased with both the Aronoff and Brady worship services.

“Every Grain of Sand”

Dylan introduced “Every Grain of Sand” as the concert closer on November 5, 2021, in Cleveland. Four nights later, he concluded the Aronoff concert with a stunningly gorgeous performance of the song. He continued to send audiences home with this blessing for the rest of the tour, 225 RARW performances total. It came to feel like the entire live experience was directed toward this climactic final experience.

I had a few days of advance notice that he would probably be playing “Every Grain of Sand” at the Aronoff, but I still wasn’t prepared for how deeply it affected me.

It’s a complex song, and my reaction to it evolved over the course of the tour. “Every Grain of Sand” begins as a prayer for forgiveness: “In the time of my confession, in the hour of my deepest need / When the pool of tears beneath my feet flood every newborn seed.” He’s crying so much that his tears threaten to drown his seeds, making new growth impossible. What did he do that’s so bad? He compares himself to Cain: “Like Cain I now behold this chain of events that I must break.” One begins to wonder if his crime, to borrow the words King Claudius, “hath the primal eldest curse upon’t— / A brother’s murder” (Hamlet 3.3.37-38). And like Claudius, the singer struggles mightily to confess and atone for his sins.

Don’t worry—I’m not going to ruin “Every Grain of Sand” by turning it into another murder ballad. Not exactly. The enemy this singer fights is an internal one, the same doppelganger Dylan identifies in “Where Are You Tonight? (Journey Through Dark Heat)” [“I fought with my twin, that enemy within”] and “Jokerman” [“Staying one step ahead of the persecutor within”]. In “Every Grain of Sand,” he refers to it this way: “There’s a dyin’ voice within me reaching out somewhere / Toiling in the dangers and in the morals of despair.” It’s a battle between dueling selves, and only one can survive. Will the singer be dragged down by his evil twin and drowned in the pool of tears? Will he be shoved into the furnace and burned by “temptation’s angry flame”? Is he Cain or is he Abel? Is he damned or can he still be saved?

“Every Grain of Sand” was the closing song on Shot of Love (1981), the third album in Dylan’s Christian trilogy. He was much more ambivalent by the end of that religious journey than he was at the beginning. In the first flush of born-again conversion, he was still thinking in terms of black-and-white moral certitudes: you can serve the Devil or you can serve the Lord. “Ya either got faith or ya got unbelief and there ain’t no neutral ground,” as he adamantly declared in “Precious Angel.” By the time he got to “Every Grain of Sand,” the path forward wasn’t nearly as clear, and the prospects for salvation were far less assured. He’s “hanging in the balance,” and the scales could still tip either way.

Forty years after the song’s release, those conditions of uncertainty and irresolution felt universal and more relevant than ever. “Every Grain of Sand” is the perfect closing song for the RARW Tour because it diagnoses the world Dylan releases us back into after the concert is over.

The arrangements and vocals for “Every Grain of Sand” are pretty similar in 2021 and 2023—until the very end. After singing the final verse, Dylan continues to play piano with his right hand, but with his left hand he pulls out his harmonica. Go to 5:28 and listen to the results.

Pentecost lays down a strong and steady beat, like he’s stacking every-grain-of-sandbags for Dylan to climb higher and higher upon. The rising emotional tide that this concert had been conjuring all evening finally crests over the Ohio River floodwall, crashes across the auditorium, and pours into the audience, drenching us all in communal bliss.

The words of “Every Grain of Sand” may leave the singer hanging in the balance, but Dylan’s divine harmonica communicates deliverance and release, like Gabriel blowing his trumpet to open the gates of heaven. Don’t knock, just walk on in.

As many other fans have noted, the end of an RARW concert is very emotional. Each time you see Dylan these days, you figure it’ll probably be the last. How long can he keep this up? If you’ve been following the tour at all, you know that “Every Grain of Sand” is the closer, no encores, and so this may well be the final song you ever hear him play live. Someday too soon, he’ll just be the twinkle from a distant star that burned out eons ago but still emits light. He’ll become the pirate radio signal. But for the moment—right here, right now—he stands before us, live and in the present, opening his heart and letting us in.

Works Cited

Bootleg audio recording. Taper jefft3881, remastered by Bennyboy. Aronoff Center of the Performing Arts, Cincinnati (9 November 2021).

Bootleg audio recording. Taper jefft3881, remastered by Bennyboy. Andrew J. Brady Music Center, Cincinnati (20 October 2023).

Dylan, Bob. The Official Lyrics. The Official Bob Dylan Website.

https://www.bobdylan.com/.

McLeese, Don. Dwight Yoakam: A Thousand Miles from Nowhere. University of Texas Press, 2012.

Padgett, Ray. “Rough and Rowdy Ways Tour Finale II: The Arrangements.” Flagging Down the Double E’s (9 April 2024),

.

Pareles, Jon. “A Wiser Voice Blowin’ in the Autumn Wind.” New York Times (28 September 1997). https://www.nytimes.com/1997/09/28/arts/pop-jazz-a-wiser-voice-blowin-in-the-autumn-wind.html.

Salvucci, Jim. “Bob Dylan and Wallace Stevens in Conversation.” The Dylan Review 3.1 (2021), https://thedylanreview.org/2021/07/25/bob-dylan-and-wallace-stevens-in-conversation/.

Shakespeare, William. Hamlet. The Second Quarto, 1604-05. Arden Shakespeare Third Series. Eds. Ann Thompson and Neil Taylor. Bloomsbury, 2006.

Tenschert, Laura. “Chapter 1: ‘Sing in Me, Oh Muse’: Rough and Rowdy Ways, the Nobel Prize & the Shaping of Bob Dylan’s Legacy.” Definitely Dylan (11 October 2020), https://www.definitelydylan.com/podcasts/2020/10/11/chapter-1-sing-in-me-oh-muse-rough-and-rowdy-ways-the-nobel-prize-amp-the-shaping-of-bob-dylans-legacy.

---. “‘Slow Coming Home’: Rough and Rowdy Ways Tour Finale (with Ray Padgett).” Definitely Dylan (24 November 2024), https://www.definitelydylan.com/listen/2024/11/24/slow-coming-home-rough-and-rowdy-ways-tour-finale-with-ray-padgett.

Thomas, Richard F. Why Bob Dylan Matters. Dey St., 2017.

---. “‘And I Crossed the Rubicon’: Another Classical Dylan.” The Dylan Review 2.1 (2020), https://thedylanreview.org/2020/06/12/and-i-crossed-the-rubicon-another-classical-dylan/.

Yoakam, Dwight. “South of Cincinnati.” Guitars, Cadillacs, Etc., Etc. Reprise, 1986.

Wonderful article. I loved to hear the contrast between TNT and RARW tours.