Dylan in Cincinnati: 2021 & 2023

Rough and Rowdy Ways Tour, Part 1

Earlier this month, Bob Dylan wrapped up the latest leg—and likely the final leg—of the Rough and Rowdy Ways Tour. [Spring 2025 update: Despite the announced end date, Dylan has decided to continue the RARW Tour beyond 2024.]

If you’re like me, most mornings began with a glance at boblinks to see what songs Dylan played the night before. While waiting for bootlegs to emerge (and Bennyboy’s impeccable remasters), my next move was to check my inbox for a field report from Flagging Down the Double E’s. No one did a better job of covering the RARW Tour than Rough and Rowdy Ray Padgett and his deputies across the globe.

Like many of us, Ray sometimes missed the variety and unpredictability of the old Never Ending Tour setlists. But RARW had its own rewards, as he pointed out in his 2023 Philadelphia concert review:

These days Bob Dylan is more predictable. But he is also something he often was not: Consistent. Every show is great. That would be an unimaginable sentence in many years past. Consistency has rarely been one of Dylan’s fortés; certainly not in the NET era. But for the entire Rough and Rowdy Ways tour […], I’ve never heard of a show where the general fan consensus was, “Well that one sucked.” I don’t think it’s that the peaks are higher. In almost any era, no matter how dire, some shows were sublime. Now, the baseline is higher. The entire spectrum of plausible show grades today ranges from like an A– to an A+.

Ray was there for the first RARW show in Milwaukee on November 2, 2021, and he attended the (presumed) last one in London on November 14, 2024. After the final show, Ray declared, “when the dust settles, the Rough and Rowdy Ways tour will be viewed as one of his great artistic achievements.” Hyperbole? I don’t think so. Ray makes a strong argument: “For three years he conducted a nightly experiment in the malleability of his own songs, stretching them and shifting them, reworking them radically over and over again. No matter what the setlist read on boblinks.com, no night was the same.”

The setlists varied little between Dylan’s first RARW concert in Cincinnati in 2021 and his second in 2023. Take a look for yourself.

When: November 9, 2021

Where: The Aronoff Center

Band: Bob Dylan (vocals and piano), Bob Britt (guitar), Charley Drayton (drums), Tony Garnier (electric and stand-up bass), Donnie Herron (steel guitar, electric mandolin, accordion), Doug Lancio (guitar)

Setlist:

1. “Watching the River Flow”

2. “Most Likely You Go Your Way (and I’ll Go Mine)”

3. “I Contain Multitudes”

4. “False Prophet”

5. “When I Paint My Masterpiece”

6. “Black Rider”

7. “I’ll Be Your Baby Tonight”

8. “My Own Version of You”

9. “Early Roman Kings”

10. “To Be Alone with You”

11. “Key West (Philosopher Pirate)”

12. “Gotta Serve Somebody”

13. “I’ve Made Up My Mind to Give Myself to You”

14. “Melancholy Mood”

15. “Mother of Muses”

16. “Goodbye Jimmy Reed”

17. “Every Grain of Sand”

The Aronoff show was only the sixth concert of the new tour. When Dylan returned to Cincinnati a couple years later for RARW concert #150 at the Brady Music Center, he played mostly the same songs in the same order.

When: October 20, 2023

Where: The Andrew J. Brady Music Center

Band: Bob Dylan (vocals, piano, and harmonica), Bob Britt (guitar), Tony Garnier (electric and stand-up bass), Donnie Herron (steel guitar, violin, mandolin), Doug Lancio (guitar), Jerry Pentecost (drums)

Setlist:

1. “Watching the River Flow”

2. “Most Likely You Go Your Way (and I’ll Go Mine)”

3. “I Contain Multitudes”

4. “False Prophet”

5. “When I Paint My Masterpiece”

6. “Black Rider”

7. “My Own Version of You”

8. “I’ll Be Your Baby Tonight”

9. “Crossing the Rubicon”

10. “To Be Alone with You”

11. “Key West (Philosopher Pirate)”

12. “Gotta Serve Somebody”

13. “I’ve Made Up My Mind to Give Myself to You”

14. “That Old Black Magic”

15. “South of Cincinnati”

16. “Mother of Muses”

17. “Goodbye Jimmy Reed”

18. “Every Grain of Sand”

And yet, for all the obvious similarities, the tagline on the poster proved true: “Things aren’t what they were . . . .” The Brady concert stretches, shifts, and reworks the songs from the Aronoff in fascinating and innovative ways.

My series on Dylan in Cincinnati examines his evolving performance art by concentrating on concerts in a single city over the span of his entire career. By placing the Aronoff and the Brady performances in conversation with each other, we can better appreciate the metamorphosis of Dylan’s RARW Tour into, in Ray’s words, “one of his great artistic achievements.”

Instead of treating the 2021 and 2023 concerts separately, I’ve decided to provide broad contexts for both and then go song by song, contrasting the different arrangements, performances, and receptions. I’m admittedly biting off more than I can chew in a single meal, so I’m going to split it into two courses. Part 1 will provide contexts for understanding the concerts and then cover the first eight songs. We’ll feast on the second half of the concerts in Part 2.

Contexts

Now that my study has made it up to the contemporary period, there is less need to explain the historical context behind Dylan’s recent shows. You remember—even if you’d rather forget. But I have future readers in mind, too, for whom these memories will have faded, or who did not live through our tumultuous times. So let’s roll back the calendar and revisit some events and experiences that broke our hearts, troubled our minds, and pricked our consciences in the months before the Rough and Rowdy Ways Tour began.

Any contextualization has to begin with Covid [aka COVID-19]. This novel coronavirus was first detected in the Wuhan province of China in December 2019 and rapidly spread across the globe. By the spring of 2020, the world was in the grips of a brutal pandemic. Hospitals quickly filled up beyond capacity, isolation measures ground routine life to a halt, and the death toll rose with alarming speed from the hundreds to the thousands to the millions.

We all took a crash course in virology and learned the medical jargon as we doomscrolled our way through lockdown. The capacity of this virus to spread through airborne transmission, its acute morbidity among the elderly and other vulnerable populations, and its unprecedented ability to mutate into treatment-resistant variants, all combined to make Covid one of the deadliest pandemics in human history.

Mass gatherings, such as concerts, were banned in an attempt to limit the contagion. As a result, the Never Ending Tour abruptly ended after a 31-year run. For the first time in decades, Bob Dylan did not perform in public in 2020. We now know that he was extremely active on multiple artistic fronts in 2020, but his rejuvenation took place away from public view, like a caterpillar in the chrysalis.

As if a global pandemic weren’t bad enough, other major sources of trauma and outrage roiled across the nation during the months preceding the RARW album and tour. Police killings of Black citizens has long been a systemic problem and moral disgrace in the United States. In the vast majority of cases these deaths have gone unpunished, and largely unnoticed beyond the families and communities directly impacted. However, in 2020 there were two such killings that were so egregious that they sparked mass protests across the country and beyond.

On May 25, 2020, Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin detained George Floyd by kneeling on his neck and back for 9 minutes and 29 seconds. We know the precise time because the encounter was filmed by bystanders on cell-phone video. Floyd died of asphyxiation. His final words were “I can’t breathe.” Video of Floyd’s murder quickly spread across social media. Large protests sprang up in Minneapolis in the immediate aftermath, and Black Lives Matter rallies were hastily organized across the country in the days following.

In his 2020 New York Times interview with Dylan, Douglas Brinkley asked the native Minnesotan for his reaction to Floyd’s murder, which just happened to take place the day after Dylan’s 79th birthday. “It sickened me no end to see George tortured to death like that,” a depressed Dylan told Brinkley. “It was beyond ugly. Let’s hope that justice comes swift for the Floyd family and for the nation.”

About a hundred miles from Cincinnati, Breonna Taylor was gunned down by Louisville police on March 13, 2020. Several plain-clothes officers were serving a search warrant after midnight when they forced entry into her apartment. Taylor’s boyfriend claims that he mistook the officers for intruders and fired a shot. The police responded with a barrage of gunfire. Five shots struck and killed Taylor.

By May 2020, after no charges had been filed against any of the officers involved in the shooting, protesters gathered outside the Louisville mayor’s office demanding justice. The rallying cry for these protests was “Say Her Name!” Breonna Taylor’s cause merged with that of George Floyd to fuel Black Lives Matter protests throughout the summer and fall.

Cincinnati was one of dozens of cities that held such rallies. The largest was on June 7, when several thousand protesters marched downtown from Fountain Square to the Hamilton County Courthouse—passing very near where Dylan would play at the Aronoff the following year. The week after the protest, a group of artists from the University of Cincinnati designed a giant Black Lives Matter mural for Plum Street downtown, directly in front of City Hall. The mural was completed in time for Juneteenth: June 19, 2020. On that same day, Bob Dylan released the album Rough and Rowdy Ways.

A very different protest movement gathered momentum that fall in the wake of the 2020 U.S. elections. Pandemic conditions led to the largest mail-in vote in election history. Authenticating and counting mail-in ballots is labor-intensive and time-consuming, so it took four days before the presidential election results became clear. The results were decisive: Joe Biden won the popular vote by over 7 million, and he won a substantial victory over incumbent President Donald Trump in the electoral college by a margin of 306 to 232.

Trump refused to concede defeat, insisting that Democrats rigged the election against him. Despite repeated court rulings which found no legal merit to his claims, he continued to peddle baseless conspiracy theories. Trump inflamed supporters with allegations of widespread voter fraud, spawning the “Stop the Steal” movement. In a last-ditch effort to overturn the results, he promoted a huge “Save America” rally in Washington, D.C., on January 6, 2021. This date was chosen to coincide with Congressional certification of Biden’s electoral victory.

After an inflammatory speech from Trump inciting his followers to fight back, a couple thousand demonstrators stormed the Capitol in an attempt to stop the certification. Rioters overwhelmed police, vandalized the building, and threatened members of Congress and Vice President Mike Pence. Six people were killed during the insurrection, but ultimately the certification was only temporarily disrupted. Congress reconvened hours later and confirmed the election results, officially declaring Joe Biden as the winner. He was inaugurated two weeks later as the 46th President of the United States.

Everyone who lived through these events remembers where they were on January 6th. I know I’ll never forget. My mother caught Covid in late December and her health rapidly deteriorated. She died on January 5, 2021. I was down in Tennessee helping prepare her funeral as the Capitol riot unfolded in Washington.

“We’ve all had too much of sorrow, now is the time for joy,” as Nick Cave wisely sings. Rather than brooding in idle despair, Dylan kept his hands busy with new creations during his time off the road. He did a lot of painting during the pandemic, as evidenced by his Retrospectrum exhibit that opened in 2021. He was also busy scribbling prose, as we discovered when he published The Philosophy of Modern Song in 2022.

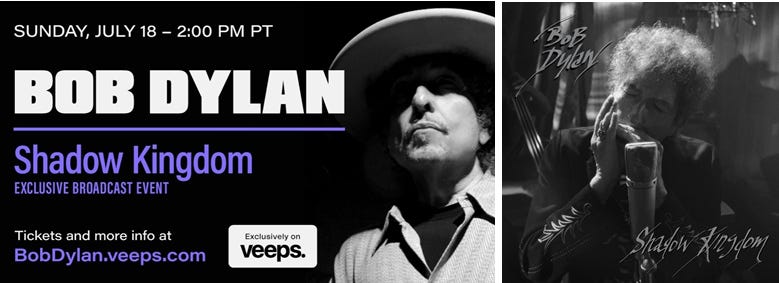

Touring was on indefinite hold, but that didn’t keep Dylan from reimagining his songs in new arrangements and strange settings. In the summer of 2021, Dylan teamed up with director Alma Ha’rel to record Shadow Kingdom: The Early Songs of Bob Dylan, a mysterious black-and-white film of him performing thirteen songs from the sixties through the eighties in the fictional Bon-Bon Club of Marseille (actually constructed on a soundstage in Santa Monica). The concert was available on-demand for a month through the Veeps streaming service, and it whet the public’s appetite for Dylan’s return to concert performance.

Dylan’s most important creation during this surprisingly fertile period was a magnificent collection of new songs. He hadn’t released an album of original material since 2012, and many speculated that the title of Tempest signaled it would be his last (cf. Shakespeare’s last play The Tempest). So it came as a shock when Dylan suddenly put out a new song in March 2020. “Greetings to my fans and followers with gratitude for all your support and loyalty across the years,” he tweeted. “This is an unreleased song we recorded a while back that you might find interesting. Stay safe, stay observant and may God be with you. Bob Dylan.”

Why release a song in 2020 about the assassination of President Kennedy in 1963? I think Nick Cave captures it best in The Red Hand Files:

At the heart of this seventeen-minute epic is a terrible event, the assassination of JFK—a dark vortex that threatens to pull everything into it, just as it did in the USA back in 1963. Whirling around the incident Dylan weaves a litany of loved things—music mostly—that reach into the darkness, in deliverance. As the song unfolds he throws down lifeline after lifeline, insistent and mantra-like, and we are lifted, at least momentarily, free of the event. Dylan’s relentless cascade of song references points to our potential as human beings to create beautiful things, even in the face of our own capacity for malevolence. “Murder Most Foul” reminds us that all is not lost, as the song itself becomes a lifeline thrown into our current predicament.

Dylan was only beginning to throw lifelines. He followed up “Murder Most Foul” with “I Contain Multitudes” in April and “False Prophet” in May. The latter release was accompanied by this teaser: “From the forthcoming album by Bob Dylan Rough and Rowdy Ways.”

Hallelujah! Rough and Rowdy Ways was hailed as an instant classic by fans and critics alike. Dylan was justifiably proud of this work and eager to deliver it directly to the people. He announced his return to the road in the fall of 2021 with the “Rough and Rowdy Ways World Wide Tour, 2021-2024,” showcasing his new songs with the kind of dogged commitment he hadn’t shown new work since the gospel tours of 1979-1980.

The RARW Tour continued to be anchored by Dylan’s trusty sidekick Tony Garnier. The bassist was the longest-serving member of the NET band, and he continued his indispensable contributions to Dylan’s performance art in this latest venture. As of the conclusion of the RARW Tour, according to bobserve, Garnier has played 3,374 concerts with Dylan. What an amazing partnership they’ve enjoyed for 35 years.

Multi-instrumentalist Donnie Herron also signed on for another tour of duty. He had been part of the NET since 2000. This latest batch of songs benefited mightily from Herron’s steel guitar, violin, and accordion, and Dylan leaned on him heavily for the evolution of the RARW sound. By the time Herron parted ways with the tour after the spring leg of 2024, he had become the third longest-serving musician in Dylan’s bands, behind only Garnier and George Receli.

Dylan welcomed back guitarist Bob Britt, who had joined the NET in the fall of 2019 before the pandemic euthanized the tour. The RARW Tour also included two rookie band members: drummer Charley Drayton and guitarist Doug Lancio. Both are seasoned musicians with impressive resumes, but neither had run the gauntlet on tour with Dylan before. By the way, Charley Drayton’s grandfather, Charlie Drayton, was a bassist who played with several big jazz acts and recorded multiple tracks at Cincinnati’s King Records.

The RARW Tour kicked off on November 2, 2021, in Milwaukee. A week later, the tour bus pulled up to the Aronoff Center in Cincinnati. Joined by my wife Cathy and our son Dylan, we masked up, stood in line, presented our vaccination cards, and filed into the plush auditorium to witness one of the most moving concerts I’ve ever attended. That said, the show certainly wasn’t flawless. There were some stumbles and miscues from a band still learning these songs and finding its groove after a long sabbatical from live performance.

Two years later and seven blocks south, I would make another pilgrimage to see Dylan on his return to Cincinnati at the Brady Music Center. They had figured out a lot by October 2023, and the Brady performance proved superior to the Aronoff in several ways, though it’s certainly not a competition.

One new player had joined the band in the interim. Jerry Pentecost replaced Charley Drayton on drums. Pentecost was playing with Old Crow Medicine Show when he got an offer he couldn’t refuse from Dylan. He played a memorable gig with Old Crow at Cain’s Ballroom in Tulsa during the “Dylan and the Beats” conference in 2022. Back in 2017, when the band was on their “50 Years of Blonde on Blonde” tour, they put on a great show at Cincinnati’s Taft Theater—the first venue Dylan ever played in the city. But nothing could top the Brady performance of 2023, and Pentecost was a crucial ingredient to the magic potion that night.

“Watching the River Flow”

It had been forever since most of us at the Aronoff had attended a concert. Dylan played a wonderful show at NKU in 2019, so in terms of normal calendar time he hadn’t been away from the region that long. But these weren’t normal times. So much had been packed into those two years that it felt more like two decades. We really didn’t know if we’d see Dylan or each other again. The anticipation was combustible, and you can hear it erupt in applause when Dylan walks out on stage. He’s back!

The star of the NKU show had been Dylan’s revitalized voice. The arrangements on the Rough and Rowdy Ways album are designed to showcase his voice, and that same principle extends throughout the RARW concerts. Fans have noted for years that it usually takes Dylan a couple songs to loosen up the old vocal chords and start singing at full strength. The typical 2021-2024 setlists factor physiology into the equation, giving Dylan a chance to get his juices flowing before introducing the first RARW song.

“Watching the River Flow” is more than a warmup exercise, however. The song was fifty years old when Dylan played it at the Aronoff, and yet the lyrics sound more relevant than ever. In the first verse, the singer plops down on a bank of sand and watches the river flow. Over the course of the song, people, trucks, birds—life—move past him, but he remains stuck in the same spot. The condition isn’t just physical, it’s also metaphysical, psychological, and emotional.

The singer in “Watching the River Flow” is not as despondent as Otis Redding in “Sittin’ on the Dock of the Bay,” but he’s not as content as John Lennon in “Watching the Wheels” either. He occupies an in-between state, what Matthew Arnold describes as “Wandering between two worlds, one dead / The other powerless to be born.” He’s not what he was, but he’s not yet what he must become. He is watching and waiting and preparing.

Back in 1971, this may have been a personal statement about Dylan’s self-imposed exile from the road, when he chose to stop touring for eight years and commit instead to nurturing his marriage and family. But in 2021, “Watching the River Flow” had much wider application. It felt emblematic of our collective, involuntary, stuck, in-between status during the pandemic. It’s a perfectly pitched opening statement for any concert, but especially for one situated in post-vaccination Covid, when we were cautiously beginning to creep out of hibernation, getting up from the riverbank and rejoining life’s flow—and going to Dylan concerts again.

When Dylan returned for his second RARW concert two years later, he was literally singing “Watching the River Flow” from a riverbank. The Brady is located on the banks of the Ohio River, with a lovely view of the Roebling Suspension Bridge (the architect’s rough draft for the Brooklyn Bridge).

Dylan’s voice was in fine form in 2023, but the standout feature was his piano. I’ve never heard him play better. Ever since he transitioned away from guitar to keyboards as his primary instrument in concert, he has often resorted to stiff-fingered plunking. Not tonight. He turned the Brady into his own honkytonk, nimbly playing cracker piano that earned cheers right from the start from an appreciative sold-out audience.

The whole band is in a great groove. New drummer Jerry Pentecost pounds out a more insistent rhythm than Charley Drayton laid down in 2021. The guitars are amped up, too, contributing to a notably bigger sound on this opening number. But Dylan’s dexterous and playful piano is the highlight, feeding off the energy of the Friday night crowd.

“Most Likely You Go Your Way (And I’ll Go Mine)”

Dylan & Company weren’t always in such a great groove. Exhibit A: “Most Likely You Go Your Way (And I’ll Go Mine).” This song is a weak link in both of the Cincinnati RARW concerts. The Aronoff performance is out of sync from the start:

Drayton establishes a steady foundation, but the other musicians are focused elsewhere. The bandleader isn’t pleased. He bangs on his keyboard, possibly trying to signal unspoken instructions. If so, the message is never decoded. Daddy’s mad and one of the kids is in trouble. The intro stretches out, as if Dylan is reluctant to begin singing until the band follows his conducting. But he eventually starts anyway because they don’t have all night.

During the bridge the music grinds to a halt entirely and Dylan sings solo. This is orchestrated, not accidental, but it’s still not very effective. With the musicians struggling to fire on all cylinders anyway, this technique of slowing down, nearly stopping, then speeding up again just makes them sound even more erratic. Don’t make me stop this car!

The joke practically writes itself: Dylan is going one way and the band is going another.

The Brady performance isn’t much better. The band sounds disjointed again, but in a different way than at the Aronoff.

The musicians lay back, putting primary emphasis on Dylan’s voice. That wouldn’t usually be a problem, but tonight it is, and the fault lies with the singer. His pace of delivery is jarringly uneven: speeding up, slowing down, inserting long pauses in the middle of verses that serve no purpose other than defying the band to follow along. He has some nice flourishes on the piano, but overall the song is a disappointment. I imagine that the guys on stage were eager to move away from this song and on to the main attraction.

“I Contain Multitudes”

The third slot is reserved for “I Contain Multitudes,” the opening track from Rough and Rowdy Ways. This is where the concert should snap into place. “I Contain Multitudes” is a great song. Dylan has been auditioning to play this part since his twenties, and now he finally sounds like a prophet on the mountaintop. The moment the band begins playing the identifiable opening chords, fans applaud with recognition and delight: this is what we’ve come to hear. Dylan stands with his microphone at centerstage, determined to perform the hell out of this RARW manifesto. That’s what got him through, and that’s what brought him here.

Unfortunately, this particular performance is star-crossed from the start. “Today and tomorrow and yesterday, too / The flowers are dying like all things do.” It’s a striking opening. Too bad that’s not what Dylan sings. At the Aronoff he flubs it: “Yesterday and tomorrow, yesterday too.” Oops. But that’s a small hiccup, nothing to fuss about. Dylan regains his stride and hammers home his vocals on the rest of the first two verses. The audience yelps its approval after each refrain.

Then comes the third verse, and things come unraveled. Go to 1:36 and hear for yourself.

Red Cadillac and a black moustache

Rings on my fingers that sparkle and flash

[Long pause]

Half my soul baby belongs to you

What happened? If you’re just listening to the bootleg, you probably assume that Dylan simply dropped a line. After all, this was only the sixth live performance of “I Contain Multitudes.” His printed lyric sheets were visible on the piano throughout the evening, and he clearly depended upon them at times to prompt his memory.

But that’s not what happened. Sitting six rows from the stage, I heard an audible pop and then silence. Sayonara, centerstage mike. Ever the consummate professional, Dylan quickly shifted back to the piano mike and resumed the song. It’s actually pretty impressive that he only missed one line. A masked crewmember darted out (everyone but the band members was masked that night), quickly fixed the problem, and the show went on. In his review on boblinks, Joe Hollon speculates that Dylan stepped on the microphone chord and unplugged it, and that sounds entirely plausible to me.

Okay, so the rider fell off his horse, but he quickly remounted. Crisis averted? Alas, no. The technical snafu distracted Dylan and broke his concentration. Listen to the fourth verse, beginning at 2:15.

I’m just like Anne Frank – like Indiana Jones

And them British bad boys the Rolling Stones

[No words for 28 seconds!]

I sing the songs of experience like William Blake

I have no apologies to make

No apologies needed—but those 28 seconds of dead air are excruciating. He seems lost up there. He was poised to perform this centerpiece song at centerstage, but instead he was forced to shuffle back behind the piano, and it throws him off. He needs his cheat-sheet to get back on track. It’s hard to watch.

This was supposed to be the triumphant opening salvo from the new album, and instead he’s firing blanks. The Aronoff “I Contain Multitudes” was probably the most banjaxed rendition of the entire tour. What a shame. From my vantage point in the audience, it was like watching a champion Olympic skater take a spill on his signature jump. He got through it—he finished the routine—but the effect was deflating. A very rough way to begin Rough and Rowdy Ways in Cincinnati.

You could chalk this moment up to benign causes: bad luck, unfamiliarity with the song, rusty stage mechanics after an extended break from performance. But it reminds me that, in the early days of the RARW Tour, there was a lot of chatter about Dylan’s physical condition. Looking back on it, I think the Covid climate of pervasive illness and death, where so many elderly people got sick and didn’t get better, made us hypersensitive to Dylan’s wellbeing in ways we weren’t accustomed to dwelling upon while enjoying a concert.

Local singer-songwriter and author Mike Roos attended the Aronoff show, and his concert review is dominated by concerns over Dylan’s health. Roos acknowledges the singer’s renewed vocal strength: “Dylan’s singing, particularly on the quiet RARW songs, was very moving, heartfelt and lovely. Some of the best singing he’s ever done, in my mind. It was frequently riveting.” But Roos worried that Dylan’s dependence on the printed lyrics suggested cognitive decline. He also sensed that the frontman was sometimes addled and leaned upon veterans Garnier and Herron to guide him along. Roos candidly reflects:

Which leads me to the most disturbing element of the show: Dylan’s stunningly frail physical presence. In the past, Dylan always took the stage with a swaggering confidence and arrogance, the air of a general leading his troops into battle. That was still there when I last saw him two years ago. But over the COVID break, the ravages of age have undeniably begun setting in. He is quite evidently an old man now, who needs to hold onto things for support. That seemed to be another reason for him not to venture far from the piano. He seemed very unsure of his footing and balance.

Roos must be referring to a potentially scary moment during the concert. At one point as the band was transitioning between songs, Dylan drifted over to Tony to tell him something. In the process, he banged right into the standup bass and nearly took a tumble. I gasped and fretted that our unsteady hero might not be ready to be back on stage.

In retrospect, I think the unconventional lighting of the concert—emanating from below rather than above—may have been more responsible for Dylan’s disorientation than any mental fog or deteriorating motor skills.

Allegations of Dylan’s frailty are nothing new. “He is frail and pale and soft-spoken, a trifle guarded perhaps, but still open on any subject.” That was local music critic Dale Stevens’s impression during a backstage interview with 24-year-old Dylan before he played Cincinnati’s Music Hall in 1965. When 80-year-old Dylan returned to town, he brought his frail frame with him—one that has proven equal to the task of the touring grind for over six decades.

To be fair, aspersions against Dylan’s health were highly contested by some fans during that first leg back. For instance, Mike Smith adamantly disagreed in a post on Expecting Rain:

I saw the first two shows on this tour (from the 5th and 7th row, respectively) and I think all of the speculation that Dylan might be in poor physical health is both unfounded and distasteful. He was standing for the entirety of both shows for a full one hour and 40 minutes—even when he was behind the piano—and his singing was incredible. Yes, his appearance is more “stooped” than before, which is normal for an octogenarian. But it’s ridiculous to claim that he is trying to somehow prop himself up or steady himself by performing center stage and keeping one hand on top of the piano. Does anyone really think he would somehow fall over if his hand wasn't on the piano? Give me a break. He’s just a physically and socially awkward person who doesn't know what to do with his hands if he’s not playing a musical instrument.

As for Mike Roos, his ultimate reaction to the concert was bittersweet: “As beautiful as much of the show was, I left the auditorium saddened by the thought that I probably will not see Dylan perform again. He has set 2024 as the end of this tour, without declaring that this is any kind of a farewell tour. But it is hard to witness his frailty without wondering how long he can sustain a grueling tour like this.”

Thankfully, we no longer have to speculate. Not only did Dylan make it through the entire RARW Tour, but he seemed to gain strength along the way. Any initial worries some of us may have had at the Aronoff now seem unwarranted. As of November 2024, optimism runs high that Dylan isn’t retiring, just reloading for whatever comes next.

If you want aural evidence of Dylan’s growing power as a performer over the long haul, take a listen to “I Contain Multitudes” at the Brady in 2023.

The arrangement is quite different from the Aronoff, which hewed very closely to the album version. Pentecost’s drums are more prominent at the Brady. But the big addition is Donnie Herron’s steel guitar. It gives the song a languid quality, making me appreciate it for the first time as a love song. Evidently “I Contain Multitudes” contains multitudes. Dylan’s plaintive vocals are seductive, and his tinkling ivories add to the charm.

I felt sorry for Bob during this song at the Aronoff. He deserved a better RARW debut. It’s reassuring and uplifting to hear him redeem “I Contain Multitudes” at the Brady.

“False Prophet”

Dylan and his posse come galloping back on “False Prophet,” one of the strongest performances of the night at the Aronoff. I liked this song when Dylan first released it as a single, but I loved it even more in live performance.

The thumping heart of this song is transplanted from Billy “The Kid” Emerson’s “If Lovin’s Believing.”

Dylan builds “False Prophet” around the sassy, sultry blues lick originally played by Ike Turner, a musician who frequently recorded in Cincinnati at King Studios.

After an uneven start, the band totally locks in and suddenly sound like a unit that’s been playing together for years. You can hear it on the bootleg, but you could also see it in the theater. They were so in sync that they were rocking their heads and torsos in unison.

After an underwhelming first cut from RARW, it’s a boost to hear Dylan and mates build up a head of steam and charge through “False Prophet.” They are performing at full-strength, in complete command. The image I get is of a gunslinger riding into town, busting through the saloon door, spitting on the floor, and challenging all takers to a duel.

“False Prophet” is interesting lyrically, too. Dylan may be singing in character as a reincarnated Orpheus: “Hello Mary Lou – hello Miss Pearl / My fleet footed guides from the underworld.” But the song comes across as deeply personal as well: “I opened my heart to the world / And the world came in.” Sounds very Dylanesque, though I learned from Kees de Graaf that this is one of several quotations taken from Awakening Osiris, the Egyptian Book of the Dead. “I’m first among equals – second to none / I’m last of the best – you can bury the rest.” You’ll get no argument from me. There’s also a coy marriage of words and gesture in performance when Dylan vogues at centerstage and taunts: “What are you lookin’ at? – there’s nothing to see.” Playing hard to get? Ah, Bob, you greedy old wolf.

He turns in a solid performance at the Brady, too, though his singing doesn’t quite match the growling intensity of the Aronoff rendition.

Dylan’s vocals on “False Prophet” may be A– at the Brady, but the music is A+. The lads are really bringing it. At a few points during this song, they build and build and build until you expect them to blast through the roof. Everyone in the band pumps up the jam, but Pentecost’s drums and Dylan’s piano provide the most potent rocket fuel.

“When I Paint My Masterpiece”

In her chapter “‘Today and Tomorrow and Yesterday Too’: Time in Bob Dylan’s Work of the 2020s,” Laura Tenschert points out that “When I Paint My Masterpiece” is the one song that appeared in Dylan’s pre-pandemic setlists (he played it at NKU in 2019), and on Shadow Kingdom, and in the RARW setlists. As the opener on Shadow Kingdom, it effectively serves as a “mission statement,” as Laura put it in her Definitely Dylan podcast.

The song appears to be aspirational, looking forward to a future where the singer will produce his magnum opus. In another sense, however, the song is stuck on the threshold between the past and future, like its sister song “Watching the River Flow,” both produced by Leon Russell in 1971. According to Nina Goss, “When I Paint My Masterpiece” features “a man alone in a stalled present that can dissolve into a heroic past, and who looks within to an endlessly deferred future of pure self-completion, the impossible masterpiece” (163-64).

A heroic past can become the very obstacle that keeps one stalled in the present, unable to advance. Dylan knows a thing or two on this subject. No one has ever had higher expectations placed upon him as a singer-songwriter than the only person to ever win a Nobel Prize in Literature for the job. As he told Douglas Brinkley, “even if you do paint your masterpiece, what will you do then? Well, obviously you have to paint another masterpiece. So it could become some kind of never ending cycle, a trap of some kind.”

The songwriter may feel the pressure to constantly churn out masterpieces, but the performer has to let that all that go in order to express himself freely in the moment. You can hear what that freedom sounds like in his touching performance of “When I Paint My Masterpiece” at the Aronoff. He ambles through the song like a carefree tourist in Rome. His main musical companion is Donnie on violin, following the singer like a pack of wild geese.

Some of the revised lyrics land with particular poignancy in the midst of the pandemic. For instance, in the first verse he sings:

Got to hurry on back to my hotel room

Gonna wash my clothes, scrape off all of the grease

Gonna turn my back on the world for a while, lock the doors,

Stay right there till I paint my masterpiece

Sounds like an accurate depiction of lockdown, right? Imagine my surprise when I went back and realized that he was already singing these lyrics before the pandemic in 2019.

At the Brady in 2023, Dylan pares back the music during the first verse of “When I Paint My Masterpiece,” singing with solo accompaniment on piano. He retains the revised lyrics about turning his back on the world for a while. However, the other musicians join in on the second verse, and the character of the song changes completely. Now it sounds like a post-pandemic party. Isolation is over—come on over and let’s jam!

Dylan is once again much busier at the keyboard than he was at any point in 2021. Much of the song is a jaunty shuffle, but there are a couple breakdown sections where Dylan shows off his expert chops. How did he make this quantum leap forward as a piano player? The new arrangement of “When I Paint My Masterpiece” seems deliberately designed to give Dylan space for indulging his love of the instrument tonight. That boogie-woogie maestro Leon Russell would tip is hat and tap his boot for his old pal’s piano playing tonight.

“Black Rider”

For the sixth number, Dylan dials up his third song from Rough and Rowdy Ways. Frankly, “Black Rider” didn’t do a lot for me when I first heard it on the album. But Dylan wins me over with his live performances at the Aronoff and the Brady.

The musical arrangement in 2021 is bare bones—appropriate for Dylan’s grinning skull performance. Almost all of the emphasis is upon his voice—and why not? He sounds so chilling he could make pipes freeze.

The title figure is apparently an allegory for Death. More specifically, “Black Rider” derives from so-called “Demon Lover” folk songs, a tradition Dylan knows very well (cf. “House Carpenter”). The visual imagery associated with the RARW album and tour reinforce this “Death & the Maiden” theme.

Interpreted in this light, the singer presents the perspective of the husband [i.e., the house carpenter], trying to defend his wife against the irresistible charms of a supernatural rival. “Go home to your wife / Stop visiting mine,” the singer warns.

Is the husband the sole speaker in the song? The more I think about it, the more I’m convinced that there are two speakers in this song. The first three verses represent the husband’s perspective, but the final two represent the wife’s perspective.

She resists the Demon Lover’s advances and issues threats of her own: “Don’t hug me – don’t flatter me – don’t turn on the charm / I’ll take out a sword and have to hack off your arm.” If you’re like me, you can’t hear this line without immediately thinking of the ludicrous battle between King Arthur and the Black Knight in Monty Python and the Holy Grail.

Within the context of the song, however, the hugging, flattering, and charming of the Black Rider suggests that he’s physically putting the moves on his prey. The sexual menace is made more explicit in the next verse: “Black Rider Black Rider hold it right there / The size of your cock will get you nowhere / I’ll suffer in silence I’ll not make a sound.” Like the Black Knight, the Black Rider might lose more appendages if he doesn’t lay off.

This being Dylan, however, “Black Rider” presents something more complicated and ambivalent than a straightforward assault and abduction. He has written other original songs inspired by the Demon Lover tradition. Think of “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue” and “Man in the Long Black Coat”. Those songs combine fear and danger with taboo attraction. There’s something risky, potentially harmful, maybe even fatal for the woman who follows the Demon Lover or Black Rider. But there’s also something thrilling, alluring, and highly seductive about leaving one’s drab life, with all its social and religious restrictions and domestic duties, and running off instead with an illicit dark stranger.

After all, the woman (as I now hear it) already has one foot out the door:

Black Rider Black Rider tell me when – tell me how

If there ever was a time then let it be now

Let me go through – open the door

My soul is distressed my mind is at war

Whether it’s escaping from her husband’s home or crossing the threshold from life into death, she is sorely tempted to make her getaway, one way or another.

Two years later, the Brady “Black Rider” opens more or less identically with the Aronoff version. But the two arrangements part ways in the second verse.

The initial focus on Dylan’s vocal opens up, letting drums and guitar enter the fray. About midway through the performance, I swear I hear an echo creep in. Dylan already repeats the name “Black Rider Black Rider,” but I hear that doubling turn into a quadrupling with the echo effect. It’s subtle, but it’s there.

The crowd hoots and hollers early in the song, but they get extremely quiet as the performance unfolds. In real time, this might come across as disengagement or indifference. But here I think fans are picking up on the cool echo effect and don’t want to miss it. The reverb is faint, less pronounced than the echo effect in “Not Dark Yet” at the 2019 NKU concert. If there had been much crowd noise at the Brady, then this special effect might have gone undetected. Much like the Black Rider himself, this performance sneaks up on you.

“I’ll Be Your Baby Tonight”

After unleashing Black Death on the audience, Dylan inoculates us with “I’ll Be Your Baby Tonight.” Hey, if it was cheerful enough to brighten the dark mood of John Wesley Harding, then it should provide a nice palate cleanser after the arsenic-laced “Black Rider.” Dylan and the band reimagine this country crooner as a hard-driving rocker at the Aronoff.

For years this song has struck me as describing two lovers having a casual date night, taking their time with foreplay, knowing exactly where they’re headed but in no particular hurry to get there. Frisky but harmless, and mutually consensual. Think Bob and Sara with a babysitter in 1967 Woodstock.

But I just can’t get that Demon Lover out of my head. Is “I’ll Be Your Baby Tonight” still an innocent love song in 2023? Following on the heels of “Black Rider,” I’m not so sure. After hearing from the husband and the wife in the previous song, I think we get the seductive predator’s perspective in “I’ll Be Your Baby Tonight.”

Ever since “Make You Feel My Love” from Time Out of Mind (1997), Dylan has delighted in sneaking in murder ballads disguised as love songs. Think “Moonlight” on “Love and Theft” (2001), “Beyond Here Lies Nothin’” on Together Through Life (2008), and “Soon After Midnight” on Tempest (2012). More recently, in The Philosophy of Modern Song (2022), he takes seemingly innocent love ballads by others and twists them into perverted tales of stalking, violence, and murder. For instance, when he listens to the dulcet tones of Eddy Arnold’s “You Don’t Know Me,” this is what he hears:

A serial killer would sing this song. The lyrics kind of point toward that. Serial killers have strangely formal sense of language and might refer to sex as the art of making love. Sting could have written this instead of “Every Breath You Take.” He’s watching her with another lucky guy. Not knowing where this happens makes you think that this could be happening totally inside the guy’s head, at least until he picks up that knife. (73)

Similarly, Dylan exposes a sinister subtext to Rosemary Clooney’s saccharine sweet “Come On-a My House”:

This is the song of the deviant, the pedophile, the mass murderer. The song of the guy who’s got thirty corpses under his basement and human skulls in the refrigerator. This is the kind of song where a black car rolls down the street, a window rolls down and a voice calls out, “Do you want to come over here for a second, little girl? I got some pomegranates for you and figs, dates, and cakes. All kinds of erotic stuff, apples and plums and apricots. Just come on over here for a second.” This is a hoodoo song disguised as a happy pop hit. It’s a Little Red Riding Hood song. A song sung by a spirit rapper, a warlock. (283)

Viewed through this disturbing lens, I begin to question the motives of the singer in “I’ll Be Your Baby Tonight.”

Close your eyes, close the door

You don’t have to worry anymore

I’ll be your baby tonight

Shut the light, shut the shade

You don’t have to be afraid

I’ll be your baby tonight

Be afraid—be very afraid! This sounds like another “hoodoo song disguised as a happy pop hit” sung by “a spirit rapper, a warlock,” or by the Black Rider himself. The woman addressed in this song would be far better off keeping the door open and the lights on. Or better yet—run like hell!

When Dylan alters the tempo and slows down the delivery of the final verse at the Aronoff, I’m convinced that this creepy interpretation isn’t just a figment of my twisted imagination. I’m picking up what he’s putting down. He’s performing the lurid growl of the Big Bad Wolf as he corners Little Red Riding Hood. “Kick your shoes off, do not fear / Pass that bottle over here / I’ll be your baby tonight.”

It sounds like Stanley Kowalski closing in on Blanche DuBois in A Streetcar Named Desire. She breaks a bottle and tries to fend him off, but he won’t be deterred: “Tiger—tiger! Drop the bottle-top! Drop it! We’ve had this date with each other from the beginning!” It’s soon after midnight and he don’t want no one but her.

There are a few minor lyrical changes in “I’ll Be Your Baby Tonight,” but none that can account for the song’s utter transformation in concert. The trick to this magic act is juxtaposition: the placement of one song in relation to other songs, creating new effects by making novel connections between them. In this case, call it guilt by association.

“I’ll Be Your Baby Tonight” becomes a murder ballad on the RARW Tour. Dylan puts a bunny into his top hat then, abracadabra, pulls out a rattlesnake.

The performance is more rambunctious in 2021 than in 2023. Personally, I prefer the rollicking Aronoff version. But the Brady rendition is more adventurous musically, and the more I listen to it the more it grows on me.

At first, Dylan presents the lyrics as a fervent vow of love directed straight at the audience. He will be our baby tonight. Then the band kicks into gear and delivers all the pizzazz that had previously been missing. When Dylan returns to the vocal, the mood shifts yet again. The earnest pleading is gone, replaced by a risqué come-on. The booze is kicking in and making the singer randy.

Ray Padgett offers this excellent description of the arrangement for “I’ll Be Your Baby Tonight” in the fall of 2023:

If someone told you a Dylan song had become a three-movement epic, practically prog-rock in its varied musical parts, would you ever have guessed that song would be “I’ll Be Your Baby Tonight”? It’s three songs now, really. The first half is basically solo piano, slow and stately. Then, halfway through, a big guitar riff shoves it into a high-speed jump. With no warning, it has gone from one of the quietest songs of the night to one of the loudest. But then, when Bob gets to the “mockingbird sail away” bit, it lurches to half-time as suddenly as someone pulling the emergency brake on a train. It’s a wild journey for such a seemingly simple song to go on.

A wild journey indeed, and not a simple song at all, after Dylan gives it the RARW treatment.

“My Own Version of You”

You don’t have to read between the lines to detect the ghoulishness in “My Own Version of You.” Dylan foregrounds it from the start:

All through the summers and into January

I’ve been visiting morgues and monasteries

Looking for the necessary body parts

Limbs and livers and brains and hearts

I’ll bring someone to life, that’s what I want to do

I’m gonna create my own version of you

The singer admits to being a grave robber, à la Victor Frankenstein, stealing body parts in order to assemble a new creature.

As listeners noticed immediately, this song sounds like an allegory of Dylan’s own creative process, snatching pieces of previous songs and cultural artifacts, suturing them together, and jolting them into new life. Of course, the pressure to keep producing masterpieces and to compete with his own legend must sometimes make Dylan, like Dr. Frankenstein, feel haunted by the monsters he has created.

Laura Tenschert points out that “My Own Version of You” is itself an example of a patchwork creation. She identifies allusions to both Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein and (oh, Bob!) the Cliff’s Notes to Frankenstein, as well as various musical, literary, theatrical, and cinematic references, and even Dylan’s own “Visions of Johanna” and “Solid Rock.” As Laura puts it,

What I love about ‘My Own Version of You’ is that it’s a song in which the subject matter is mirrored in the way the song is written. In other words, a story about an act of creation out of different parts is told in the form of a song fusing together bits and pieces from different sources. So we can see that the song tells us something about the creative process, about the journey towards the finished work.

I think of that phrase “a perfect finished plan” which Dylan sings in “Every Grain of Sand” [the closing song that we’ll get to in Part 2 of this installment]. But for Dylan the performer, a song is never finished, never fixed and final. Each night, he has to try and bring it back to life. So we can extend the metaphor to say that, with each live performance on the RARW Tour, Dylan reincarnated his own version of “My Own Version of You.”

He clearly relishes playing this diabolical character at the Aronoff, unveiling his most macabre vocals of the night.

I love the way the song crests in the final verse. Dylan pounds on the piano keys more forcefully as he raises the volume of his voice, practically panting with anticipation. This strikes me as the musical equivalent of the creature coming to life in Frankenstein’s laboratory.

Keeping with the trend so far, the Brady performance is more experimental musically. In 2023, “My Own Version of You” is faster paced and has way more swing. Pentecost’s drumming is more commanding than Drayton’s subtleties at the Aronoff. Herron plays an “ooooo” sound in the background throughout, adding to the ominous ambience. And Dylan conjures up some of his funkiest piano playing of the night, appropriate for the song that mentions Leon Russell by name.

Dylan reverses the order of “I’ll Be Your Baby Tonight” and “My Own Version of You” in 2023, but the “guilt by association” connection remains intact. “Black Rider” sets up a triangular relationship between the husband, wife, and seducer. In “I’ll Be Your Baby Tonight,” the Demon Lover closes in for the kill. In “My Own Version of You,” he revisits previous victims, robs their graves (looting much of pop culture in the process), and reassembles a new Bride of Frankenstein from the recycled parts—like a version touched for the very first time.

To be clear, I doubt that Dylan has thought nearly as much about this as I have. He probably just goes with his gut. Here are two new songs that tap into a similar dark vibe. It might be interesting to put an old love song in between them, either for variety’s sake or to see how the contrast creates cool effects. Good enough for him.

But not good enough for me! You take care of the creation and intuition, Mr. Dylan, and I’ll perform the post-mortem intellectual autopsy. Any way you slice it, these are three interesting songs to conclude the first half of the concert. However, viewed together as a grisly trilogy, they accrue extra layers of significance that I find super interesting. This is one of the rewards of studying Dylan as a live performer. He does very different things with the songs in concert than he did with them on the albums.

When Dylan sang “My Own Version of You” at the Aronoff, it was only the sixth performance ever. Advance forward to the Brady in 2023 and it was the 150th performance. Dylan and the band lived with these RARW songs for a couple years, and they no longer relied on cheat-sheets or road maps to get them where they’re going. They sound looser, more improvisational, and freer at the Brady. The album is a distant memory by 2023. The tour’s the thing that matters: bringing the song to life tonight, here, in this room for these people.

They still had many gifts left to bestow, and I look forward to sharing them with you in Part 2. In the first half of the concert, Dylan chose identical songs for both the Aronoff and the Brady concerts. In the second half, however, he played three different songs at the Brady, including possibly my favorite in the entire Dylan in Cincinnati series—“South of Cincinnati”! Stay tuned, and many thanks for your continuing interest and support.

Works Cited

Arnold, Matthew. “Stanzas from the Grande Chartreuse.” Poetry Foundation, https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/43605/stanzas-from-the-grande-chartreuse.

Bootleg audio recording. Taper jefft3881, remastered by Bennyboy. Aronoff Center of the Performing Arts, Cincinnati (9 November 2021).

Bootleg audio recording. Taper jefft3881, remastered by Bennyboy. Andrew J. Brady Music Center, Cincinnati (20 October 2023).

Brinkley, Douglas. “Bob Dylan Has a Lot on His Mind.” New York Times (12 June 2020). https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/12/arts/music/bob-dylan-rough-and-rowdy-ways.html.

Cave, Nick. Blog post on “Murder Most Foul.” The Red Hand Files 91 (April 2020), https://www.theredhandfiles.com/bob-dylans-new-song/.

---. “Joy.” Wild God. PIAS, 2024.

de Graaf, Kees. “Bob Dylan’s ‘False Prophet’ – An Analysis by Kees de Graaf.” Kees de Graaf (15 October 2020), https://www.keesdegraaf.com/index.php/253/bob-dylans-false-prophet-an-analysis-by-kees-de-graaf-part-1#alinea_234.

Dylan, Bob. The Official Lyrics. The Official Bob Dylan Website.

https://www.bobdylan.com/.

---. The Philosophy of Modern Song. Simon & Schuster, 2022.

---. Tweet (27 March 2020). X, https://x.com/bobdylan/status/1243389605451198465.

Goss, Nina. “‘What’s Going on in Your Show’: A Look at the Shadow Kingdom Setlist.” The Politics and Power of Bob Dylan’s Live Performances. Eds. Erin C. Callahan and Court Carney. Routledge, 2024, pp. 159-72.

Hollon, Joe. Concert Review. boblinks (9 November 2021), https://www.boblinks.com/110921r.html.

Padgett, Ray. “Two More Nights in Chicago.” Flagging Down the Double E’s (9 October 2023),

.

---. “Last Night in Philadelphia.” Flagging Down the Double E’s (20 November 2023),

.

---. “The Last Night, in London: A perfect finished plan.” Flagging Down the Double E’s (15 November 2024),

.

Roos, Mike. Concert Review. Michael Kim Roos (9 November 2021), https://mikeroos.com/2021/11/10/review-bob-dylan-at-the-aronoff-cincinnati-oh-11-9-21/.

Smith, Michael Glover. Post on “An Aging Bob on Tour.” Expecting Rain (26 November 2021), https://expectingrain.com/discussions/viewtopic.php?f=6&t=102121&hilit=aging#p2019239.

Stevens, Dale. “The Two Sides of Bob Dylan.” Cincinnati Post and Times-Star (9 November 1965): 22.

Tenschert, Laura. “Chapter 2: The Other Side of the Coin—The Myth and Mystery of Creation on Rough and Rowdy Ways.” Definitely Dylan (11 February 2022), https://www.definitelydylan.com/podcasts/2021/2/11/chapter-2-the-other-side-of-the-coin-the-myth-and-mystery-of-creation-on-rough-and-rowdy-ways.

---. “Shadow Kingdom: A Midsummer Night’s Dream.” Definitely Dylan (14 September 2021), https://www.definitelydylan.com/podcasts/2021/9/14/shadow-kingdom-a-midsummer-nights-dream.

---. “‘Today and Tomorrow and Yesterday Too’: Time in Bob Dylan’s Work of the 2020s.” The Politics and Power of Bob Dylan’s Live Performances. Eds. Erin C. Callahan and Court Carney. Routledge, 2024, pp. 173-90.

Williams, Tennessee. A Streetcar Named Desire. The Norton Anthology of Drama, shorter third edition. Eds. J. Ellen Gainor, Stanton B. Garner, Jr., and Martin Puchner. W. W. Norton, 2017.

Not sure how I missed this at the time, but just caught up and wow - this is a monumental achievement, and a wonderful document of the tour. Looking forward to diving into part 2 now

And I accidentally hit something that posted my comment before I was done. I hope that you - maybe with Ray? - do a book on the RAWR tour. It is so unique and it’s own work of art that we get to see as a dynamic venture. Think about it.