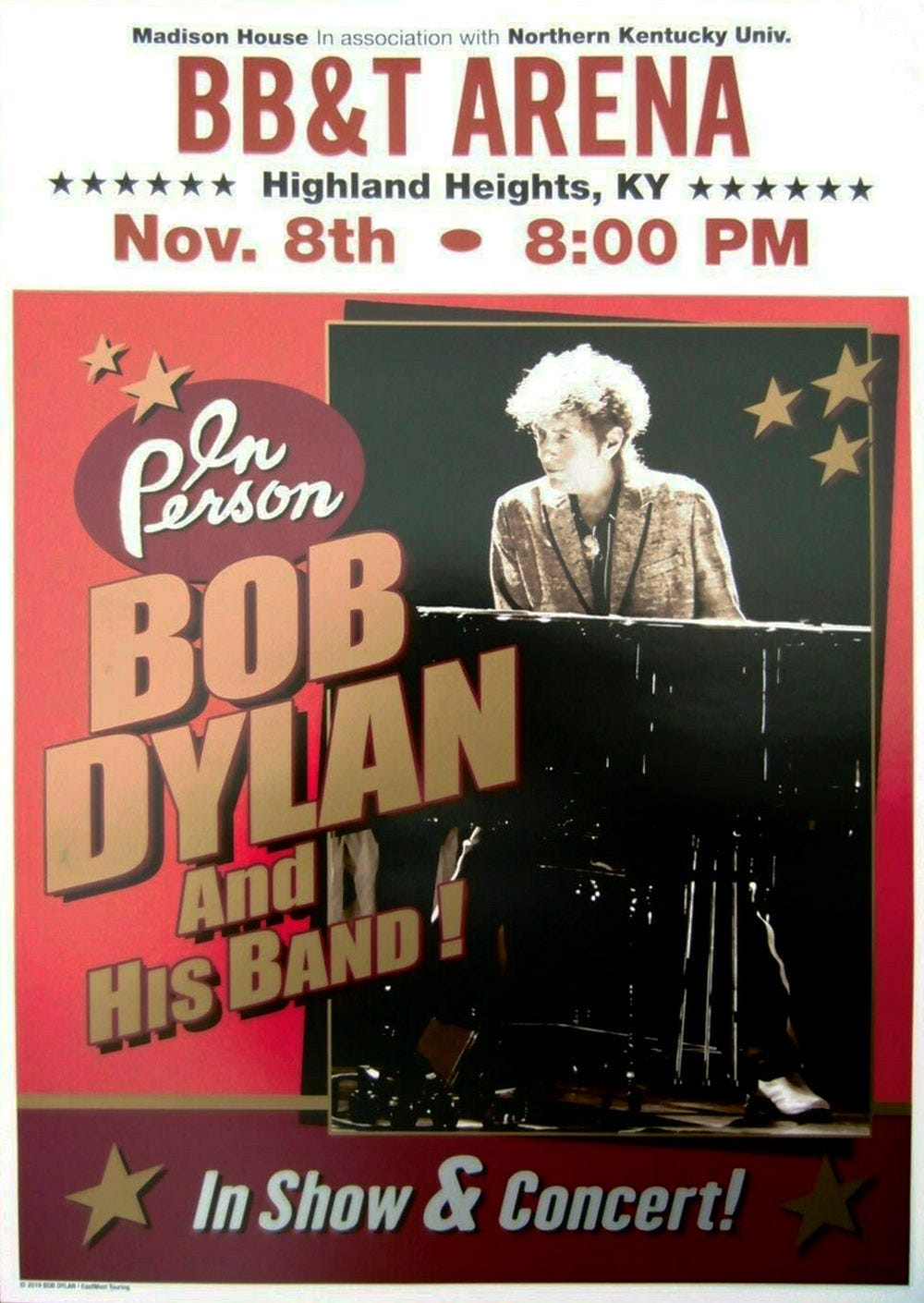

Between 2007 and 2013, Dylan played five concerts in Cincinnati. The Never Ending Tour continued to live up to its name, but it didn’t include a local stop for another six years. By the time Dylan returned for a concert at the BB&T Arena at Northern Kentucky University in Highland Heights, it was a very big deal to me because his work had begun to play an increasingly prominent role in my life.

Like many readers, I’ve been a Dylan fan since my teens. But I never found a professional outlet for that personal passion until I designed and taught a First-Year Seminar on Dylan at Xavier University in the fall of 2015. I have been fortunate to continue teaching his work regularly ever since. This ramped up study spilled over into my writing outside the classroom. I published my first article on Dylan in 2018, and his art has since become the central focus of my research, with several articles, chapters, a book on Time Out of Mind, and this Substack site. All of this had me looking at Dylan from a new perspective. “I got new eyes,” he sings in “Highlands.” I did, too, at Highland Heights in 2019.

I could see him more clearly than ever due to my vantage point—on the front row! Tickets went on sale at the box office on campus the day before they were released to the general public. I didn’t teach that morning, so I went straight down and was surprised to be the very first person there. I landed three tickets on Row A for myself, my wife Cathy, and our son Dylan. I mentioned in the last chapter that the 2013 concert was our first time seeing Bob Dylan together as a family. Our Dylan was only 12 then, but now he was a recent high school graduate and first semester freshman at Xavier—with zero interest in taking his dad’s FYS on his namesake! But he was interested in a front-row seat, not that we did much sitting.

The phone cops at BB&T Arena were out in force like a restless riot squad, so I have no pictures from the concert to share. Let this one substitute, from a senior dance earlier in 2019.

May his heart always be joyful, may his song always be sung.

Dylan Context

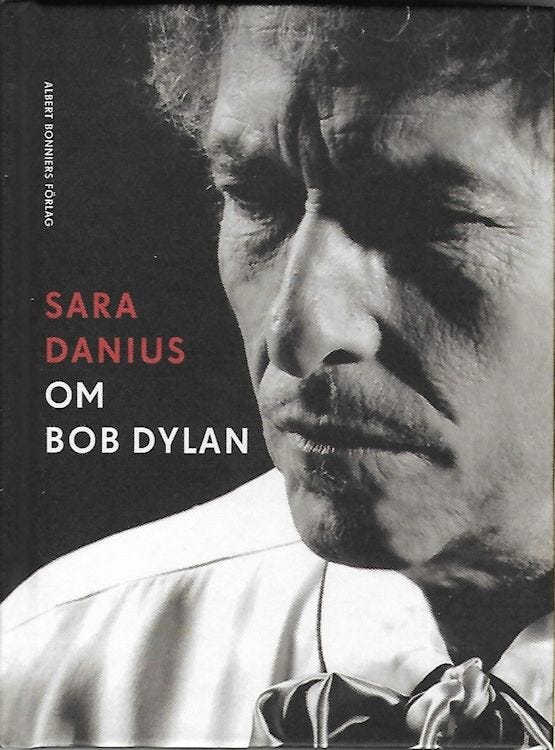

A lot happened in the Dylan universe between his Riverbend concert in 2013 and his return to Highland Heights in 2019. The biggest development happened off stage and out of the studio. On October 13, 2016, Professor Sara Danius, Permanent Secretary of the Swedish Academy, walked through a door in Stockholm and made a stunning announcement. She spoke first in Swedish then in English, but listen to them both so you can get hear the initial response the moment Pandora’s box opens:

The world’s most prestigious career achievement award in literature hadn’t gone to a U.S. author since Toni Morrison in 1993, and the Swedish Academy had never recognized a songwriter with the top honor. This unexpected selection placed him in a familiar position at the center of a storm of controversy. Opinion was sharply divided between those who found Dylan an inspired and deserving choice, and those who found him manifestly unqualified for this highest literary distinction.

Dylan himself was as surprised as anyone. It took him several days to issue any kind of statement on this dumbfounding development. We should remember his complicated history with awards. As recipient of the Tom Paine Award in December 1963, he was booed for his comments relating to Lee Harvey Oswald, which were perceived by the audience as sympathizing with President Kennedy’s assassination only a few weeks earlier. In the decades since, Dylan has amassed a sagging shelf full of prizes, but he remains perpetually wary of being claimed, categorized, beholden, or coopted by any institution in exchange for a gold cup or shiny medal.

He didn’t attend the Nobel Prize banquet, though he wrote a short but gracious speech read in absentia. He also skipped the official awards ceremony, sending his friend Patti Smith in his place, where she sang “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall” in his honor. Dylan eventually recorded a thoughtful reflection on the relationship of his art to literature and submitted it as his Nobel Lecture (a mandatory requirement for receiving the prize). Dylan walks a rhetorical tightrope in the talk. He acknowledges important literary influences on his work, but he ultimately rejects equating his songs with literature:

Our songs are alive in the land of the living. But songs are unlike literature. They’re meant to be sung, not read. The words in Shakespeare’s plays were meant to be acted on the stage. Just as lyrics in songs are meant to be sung, not read on a page. And I hope some of you get the chance to listen to these lyrics the way they were intended to be heard: in concert or on record or however people are listening to songs these days.

Speaking not only as a fan but also as a literature professor, I consider it a huge deal that Dylan was awarded the Nobel Prize. I regard it as worthy recognition for his colossal achievements. For those of us who teach and write about Dylan—often to the amusement of colleagues who shake their heads over our folly in placing a pop icon on such an exalted pedestal—the Nobel felt like a conferral of legitimacy for his art and, by extension, a validation of our efforts in studying it. His own attitude toward the honor was muted and ambivalent, so let me say unequivocally what he will never say for himself: Dylan damn well deserved the Nobel Prize in Literature.

Dylan kept his focus on performing songs rather than crowing about awards. In the interim between local concerts, the Never Ending Tour passed the 30-year and 3,000-concert milestones. The NET band experienced some turnover. Bob Britt, who had played on the Time Out of Mind recording sessions, took the place of guitarist Stu Kimball, a veteran of the NET band since 2004. Matt Chamberlain, former drummer for Pearl Jam, replaced George Receli, the NET drummer since 2002.

Somewhere along the way, Dylan discovered a passion for American standards, the kind of songs associated with Frank Sinatra. When Dylan gets into something, he goes all the way in. In short order he produced a trilogy of standards albums: Shadows in the Night (2015), Fallen Angels (2016), and his first three-disc album, Triplicate (2017). Standards formed the backbone of his live sets as well during this period. By the time he returned to the Cincinnati area in 2019, however, he had worked his way through and past this brief but intense preoccupation.

I don’t dislike Dylan’s standards albums, but I can’t say that I reach for them often. Needless to say, he has earned the right to love what he loves and play what he wants to play. He has proven adept over the years at winning us over through committed live performances, often converting skeptics into believers, or at least teaching us how to appreciate songs we initially resisted. One thing we must gratefully credit the standards period for is rejuvenating Dylan’s voice. The breath control, the careful attention to phrasing, the premium on singing within his range and in sync with a carefully orchestrated musical arrangement—all of these refined skills had an enormously positive impact on him as a vocalist. These benefits remained even after he put Sinatra back on the shelf and turned his attention back to original material.

Dylan hadn’t released any albums of new songs since Tempest in 2012. However, Columbia kept milking the cash cow, producing a steady revenue stream from the Bootleg Series: Another Self Portrait (2013); The Basement Tapes Complete (2014); The Cutting Edge, 1965-1966 (2015); Trouble No More, 1979-1981 (2017); More Blood, More Tracks (2018); and Travelin’ Thru, 1967-1969 (2019). It would be easy to take a cynical view of this marketing strategy, but the music business is a business, after all. To be fair, the hunger among fans for rare and unreleased recordings is ravenous, continuous, and genuine, not artificially manufactured by the Dylan machine. Hey, as long as they keep slopping it in our trough, we’ll keep gobbling it down and snorting for more.

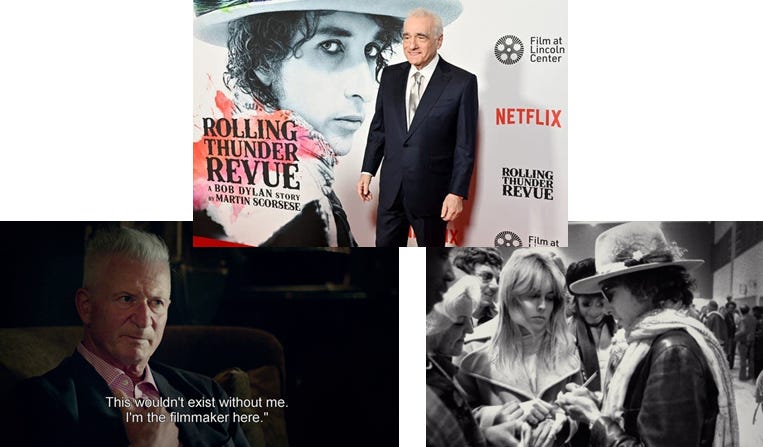

Beyond the Columbia deluxe sets, the most interesting Dylan release of the year was Rolling Thunder Revue: A Bob Dylan Story by Martin Scorsese, which premiered on Netflix in June 2019. The cunning title should have clued us in that the creative duo were up to something. Following their successful joint venture on the 2005 documentary No Direction Home, Scorsese teamed up again with the Dylan camp to assemble a film about the 1975 leg of the Rolling Thunder Revue. The results are often mesmerizing, particularly the restored high-quality footage of performances by Dylan and his illustrious tour mates.

The film received push back, however, for including a number of embellished and invented scenes, fictional characters, and doctored archival material. Some viewers felt like victims of a con game. Scorsese and Dylan were clearly co-bamboozlers in this scam, tricking the audience much like magicians or carny barkers hustling the suckers at an old-timey circus. I was thrown by these shenanigans at first, but I’ve come to appreciate the film as a cinematic correlative to the spirit of self-invention and fantasy at the heart of the Rolling Thunder Revue.

We’re almost caught up, but there’s one more major update to report. In 2016 Dylan sold his treasure trove of manuscripts, recordings, and memorabilia to the George Kaiser Foundation. This massive acquisition spawned three new entities: the University of Tulsa Institute for Bob Dylan Studies, designed to promote the study of Dylan’s work through public programming; the Bob Dylan Archive, where researchers can study the foundation’s private holdings for scholarly purposes; and the Bob Dylan Center, a magnificent museum which opened to the public in 2022, appropriately located right next door to the Woody Guthrie Center in the Tulsa Arts District. I was fortunate to present a paper at “The World of Bob Dylan Symposium” in the summer of 2019, the first international conference sponsored by the Institute, magnificently organized by the founding director, TU English and Comparative Literature Professor Sean Latham.

Cincinnati Context

As I wrote about previously, Ohio was a swing state for several election cycles in the early 21st century. After many decades as a Republican bastion at the state and federal levels, Ohio was suddenly in play for Democrats. Barack Obama carried the state in both 2008 and 2012, critical wins for securing the White House. The pendulum swung back the other direction in 2016. Donald Trump defeated Hillary Clinton by a comfortable 8-point margin in Ohio. Combined with slim victories in the traditional Democratic strongholds of Michigan, Wisconsin, and Pennsylvania, Trump won a shocking electoral college victory, despite the fact that Clinton received almost 3 million more popular votes.

This is recent enough history that most readers will not need reminding what the 2016 upset and the Trump presidency felt like. Supporters of his populist/nationalist MAGA agenda [Make America Great Again] were elated and bolstered by the unlikely triumph of the celebrity billionaire who had never held public office before winning the highest post in the land. Meanwhile, progressives were despondent. The U.S. had come so close to electing its first woman president only to falter at the finish line. To make matters worse, the electorate opted instead for a bully who proudly trumpeted bigotry and misogyny. With chants of “build that wall!” and “lock her up!” on one side of the barricades, and the increasing mobilization of the Black Lives Matter and #MeToo movements on the other side, the United States was divided by the most intense political/moral/existential disagreements since the 1960s.

Slouching toward Washington and waiting to be reborn, a local figure was beginning the metamorphosis that would lead him to play a prominent role in the national drama. On the outskirts of the Cincinnati metropolitan area, some thirty miles north of downtown, lies Middletown. This suburban enclave is the hometown of JD Vance. His current Ohio residence is in Cincinnati, where he and his wife Usha own a mansion in the neighborhood of East Walnut Hills.

You’ve all heard of him by now, but in 2019 he was primarily known as the author of Hillbilly Elegy: A Memoir of a Family and Culture in Crisis. Vance’s family hailed from the other side of the river in Kentucky. By the time he was born, they had relocated to Middletown, Ohio, in search of better job opportunities. The jobs went bust and so did the family, devolving into cycles of poverty and drug abuse. In his memoir, Vance lays bare his family’s struggles as a larger social critique of the various cultural crises plaguing Appalachia. His own journey took him far from his Middletown home: from serving in the Marines, to collegiate study at the Ohio State University and Yale Law School, to working as a law clerk in Washington and Kentucky, to a brief but lucrative career in the tech industry of San Francisco as a venture capitalist.

With Hillbilly Elegy atop the 2016 best-seller list, Vance was asked his views of Donald Trump, a cosmopolitan beneficiary of wealth and privilege who paradoxically elicited overwhelming support from disaffected Appalachian voters. At the time, Vance was highly skeptical, referring to candidate Trump in 2016 as potentially “America’s Hitler” who was “leading the white working class to a very dark place.” In 2017 he declared President Trump a “moral disaster.”

Unfortunately, like so many Republicans once critical of Trump, Vance changed his tune once he realized that his own political aspirations required fealty to the party’s strongman. By 2019, he had caught Trump fever, beginning his radical pivot from vocal critic to ardent champion. Vance actively courted favor with MAGA supporters and won endorsements from the movement’s leader. This about-face catapulted him into an Ohio senate seat in 2022 and selection as Trump’s vice-presidential running mate in 2024.

If Hillbilly Elegy is a case study in the crisis of Appalachian America, then the evolution of JD Vance might serve just as well as a cautionary tale for the crisis of the Republican party during its cultish thrall to Donald Trump. In short, tensions were roiling outside the arena when Dylan’s tour bus rolled into NKU in the palpitating red-state heartland.

The Concert

When: November 8, 2019

Where: BB&T Arena at Northern Kentucky University, Highland Heights, Kentucky

Band: Bob Dylan (vocals, guitar, harmonica, and piano); Bob Britt (guitar); Matt Chamberlain (drums and percussion); Tony Garnier (bass); Donnie Herron (violin, mandolin, and steel guitar); Charlie Sexton (guitar)

Setlist:

1. “Things Have Changed”

2. “It Ain’t Me, Babe”

3. “Highway 61 Revisited”

4. “Simple Twist of Fate”

5. “Can’t Wait”

6. “When I Paint My Masterpiece”

7. “Honest with Me”

8. “Tryin’ to Get to Heaven”

9. “Make You Feel My Love”

10. “Pay in Blood”

11. “Lenny Bruce”

12. “Early Roman Kings”

13. “Girl from the North Country”

14. “Not Dark Yet”

15. “Thunder on the Mountain”

16. “Soon after Midnight”

17. “Gotta Serve Somebody”

*

18. “Ballad of a Thin Man”

19. “It Takes a Lot to Laugh, It Takes a Train to Cry”

First Half

Even before the band arrives on the scene, it’s clear that this is going to be a different Dylan concert. The stage is illuminated by huge light fixtures from above and floor lamps from behind, evoking a Hollywood studio film set.

Stranger still, mannequins in fancy dress are positioned at the back of the stage. I’ve written elsewhere about Dylan’s dramaturgical instincts, but this is his most blatantly theatrical stagecraft to date.

What’s going on here? By placing lifeless mannequins on stage alongside live performers, Dylan may be using props to reenact the tension between Live vs. Dead which he highlighted in his Nobel Lecture. He also seems to be staging a conflict between Real vs. Fake. For an instructive analogy, consider Ray Padgett’s interview with the poet James Ragan on Flagging Down the Double E’s. Ragan and Dylan were both part of a cultural exchange program to the Soviet Union sponsored by Mikhail Gorbachev in 1985. The lineup also included Seamus Heaney, another future Nobel laureate. Ray includes this great photo, courtesy of Ragan:

One of the poems Ragan read on the tour was “The Tent People of Beverly Hills.” The opening lines refer to the same kind of clash I sense from Dylan’s stage décor in 2019:

Faceless on the Boulevard of Mirrors,

north along the flats of Rodeo Drive’s

stripped bald head mannequins,

they come treading on

the fears of high fashion,

tents on their backs

and on their cheeks the beach

black tar of tasteless chic.

Ragan’s vision of L.A. decadence—where rich celebrities brush past the dispossessed, throwing the bums a dime in their prime, checking their looks in boutique windows, visually and spiritually indistinguishable from the display mannequins—is perfectly compatible with Dylan’s first song at NKU, “Things Have Changed.” Come to think of it, once you allow this idea to take hold, you could easily imagine the song as the inner fantasy of a homeless person in Beverly Hills or Hollywood, fantasizing his way into the lives of passersby. Each verse is like a mini-movie where this California dreamer casts himself in a different starring role.

If you have been keeping up with Dylan in concert, you know that his primary instrument for many years has been keyboards, a move allegedly forced by arthritis. So it is quite striking to see Dylan come out playing guitar on “Things Have Changed.” The new drummer Matt Chamberlain provides a great polyrhythmic beat, reinforced by Tony Garnier’s locked-in bass and some surf-rock guitar that reminds me of Johnny Rivers’s “Secret Agent Man.”

The real story here is Dylan’s voice, which sounds notably better than it has in many years. The notorious rasp that crept in around the turn of the century and spread like kudzu has been beaten back, producing a vocal clarity not heard from Dylan in Cincinnati since the Bogart’s show twenty years earlier. He used to bleat and growl, but things have changed. From the front row, I could almost see the gleam in the singer’s eye, but any listener can hear the delight in his voice, especially on Bennyboy’s pristine remaster of the bootleg. Dylan sounds great tonight, and he knows it.

A noticeable recurring feature of this concert is the sound of musical cacophony before each song, like when the individual players in an orchestra tune up separately before coming together in unison to play a symphony. Although it may sound like random chaos, I’m certain that it’s an intentional and orchestrated effect in tonight’s performance. This is rehearsed chaos. It reminds me of a passage from James Baldwin’s “Sonny’s Blues,” one of the best pieces of writing about music I’ve ever read. Listening to Sonny play the blues, his brother reflects,

All I know about music is that not many people ever really hear it. And even then, on the rare occasions when something opens within, and the music enters, what we mainly hear, or hear corroborated, are personal, private, vanishing evocations. But the man who creates the music is hearing something else, is dealing with the roar rising from the void and imposing order on it as it hits the air. What is evoked in him, then, is of another order, more terrible because it has no words, and triumphant, too for that same reason. And his triumph, when he triumphs, is ours. (58)

Baldwin was a street preacher in his youth, and the scriptures continued to influence his writing throughout his life. In the description above, I hear echoes of Genesis, and that’s the same effect I get from the band’s calculated cacophony tonight. It’s not just musical, it’s cosmological: “In the beginning God created the heaven and the earth. And the earth was without form, and void; and darkness was upon the face of the deep. And the spirit of God moved upon the face of the waters. And God said, Let there be light: and there was light” (Genesis 1:1-3). Formless elements and sensations are summoned into existence from the deep, gathered together and quickened into harmonious order. Let there be music: and there was music. Let there be song: and there was song. And it was good.

You can hear an excellent example of this phenomenon in “Highway 61 Revisited.” The players are noodling willy-nilly at first like a stomped anthill, and then Chamberlain counts them off and bam! They’re all marching in the same direction, down in the groove.

Did someone mention Genesis? “God said to Abraham, ‘Kill me a son’ / Abe said ‘Man, you must be puttin’ me on”—the best hipster translation of the Abraham and Isaac story you’ll ever hear. “Highway 61 Revisited” sounds fantastic tonight! The band has a rollicking good time, and why not, with their frontman in top vocal form.

I’m reminded again of “Sonny’s Blues.” While watching his brother play at a club in the Village, the narrator finds Sonny’s playing tentative for the first couple numbers. Then he launches into a riff on “Am I Blue?,” and there’s a palpable shift in the band chemistry: “He seemed to have found, right there beneath his fingers, a damn brand-new piano. It seemed that he couldn’t get over it. Then, for awhile, just being happy with Sonny, they seemed to be agreeing with him that brand-new pianos certainly were a gas” (59).

I hear something similar in Dylan’s rapport with the NET band tonight and his evident joy in singing. He knows he’s got a damn brand-new voice at his disposal, an upgrade from the previous model. It’s a gas to sing when you’re doing it better than you have in years. Take it down Highway 61 or take it down University Drive to the BB&T Arena: these songs travel extremely well in the newly refurbished vehicle of Dylan’s voice.

The musical arrangement of “Simple Twist of Fate” is odd but interesting. It has a limping ragtime tempo with some nice fiddle fills from Donnie Herron. Dylan thrills the fans by breaking out his harmonica before and after the final verse.

His vocals sound pouty in an exaggerated sort of way, like he’s speaking to a small child or a dog [i.e., “Who’s a good boy? Are you a good boy? Yes, you are—oh yes you are!”]. You can especially hear it in his revised lines: “He found a note she’d left behind—what’d it say? / Said ‘You should have met me back in ’58 / We could have avoided this lit-tle sim-ple twist-of fate.’” Dylan has messed around a lot with the lyrics of “Simple Twist of Fate” through the years. Personally, I had never heard this final verse before tonight:

People tell me it’s a sin

That it’s wrong and wicked, too far down in

I still believe I let her get under my skin

Under my skin too late

I had another date

A date that couldn’t wait

Blame it on a simple twist of fate

What date couldn’t wait? Some date with destiny? With mortality? With the devil at the crossroads? Here the song extends beyond the one-night stand scenario typically associated with “Simple Twist of Fate,” reaching past the carnal toward the ineffable.

“Can’t Wait” is the first of four songs from Time Out of Mind, more than any other album in tonight’s setlist. Dylan’s soulful demo of this song (eventually released on Tell Tale Signs) is so different from the spooky album version on Time Out of Mind as to be essentially two different songs. The NKU ’19 performance is completely different than either of these versions.

The guitars and drums mark the limping gait of a wounded but persistent predator: think Verbal Kint morphing into Keyser Söze at the end of The Usual Suspects. Dylan pounds the beat with his vocal delivery, keeping time like an extra percussive instrument. It’s the perfect marriage of form and content for a song about a man pursuing his ex like he’s tracking prey. The stable setlists on this tour routinely slated “Simple Twist of Fate” and “Can’t Wait” in the fourth and fifth slots. This pairing creates a sense of narrative chronology, as if the jilted singer is dumped in “Fate” and then takes off after her in “Can’t Wait.” He goes directly from “a date that couldn’t wait” to issuing threats like a stalker:

I’m strolling through the lonely graveyard of my mind

Left my love with you somewhere back there along the line

I thought somehow that I would be spared this fate

But I don’t know, I said I don’t know how much longer I can wait

There’s a cool effect in “Can’t Wait” during the bridge. The musicians fall back to near silence and Dylan slows the pace to a near standstill, the tiger flexes his haunches and bares his fangs, preparing to pounce, as Dylan sings a cappella. “I’ve come to love-yooooou / And now we’re rolling through this stormy weeeeaaa-ther / I was dreamin’ of-yooooou / And all the pleasures we could roam togeeeeee-ther.” He’s showing off his improved singing skills, with the lung power to hold those notes like Caruso.

The second TOOM song of the evening is “Tryin’ to Get to Heaven.” As with “Can’t Wait,” the tune sounds completely different here than on the album.

Even on the relatively slow songs, Dylan’s glee is irrepressible tonight. His plink-plonk piano and Donnie Herron’s hopscotching violin crown this song with a red-clay halo. Like its sister song “Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door,” the lyrics of “Tryin’ to Get to Heaven” hint that the singer gets shut out of heaven, left knockin’ at the unopened pearly gates. The music in tonight’s performance, however, gives cause for hope. When the roll is called up yonder, Dylan will be there.

The first half of the concert concludes with the best-known track from Time Out of Mind, the hit song “Make You Feel My Love.” Even before Dylan utters a word, Herron already melts my heart with his violin.

“Make You Feel My Love” was made famous in covers by singers with more conventionally beautiful voices than Dylan, most notably Adele. I wasn’t a big fan of this song back in the day, but Dylan and Donnie win me over tonight. In my book on TOOM, I argue that “Make You Feel My Love” is a murder ballad masquerading as a torch song. I don’t detect any menace in the NKU ’19 rendition, however. The singer has his arm around his lover’s shoulder, not his hands around her neck.

Surely Dylan is addressing the song to the audience:

I could make you happy

Make your dreams come true

No, there’s nothin’ I wouldn’t do

Go to the ends of the earth for you

To make you feel my love

He sounds like a man who feels the love in the room, reciprocates it, and gives it expression, first with a beautiful vocal and then with an exquisite harmonica solo at the end. By 2019, Dylan had been on the road almost sixty years, delivering his music straight to the people. He has gone to the ends of the earth to make us feel his love. I was certainly feeling it in the room at NKU.

Second Half

Never content to stick with one mood for very long, Dylan begins the second half with a searing rendition of “Pay in Blood.”

There are a lot of lyrical layers to “Pay in Blood.” On one level, this is the song of an avenging killer. The singer is full of bluster: “I could stone you to death for the wrongs that you done”; “I’ll put you in a chain that you never can break”; “I got something in my pocket make your eyeballs swim / I got dogs that’ll tear you limb to limb”; “Come here I’ll break your lousy head.” It sounds like this bruiser has a list of his enemy’s body parts and is systematically checking them off as he pummels them one by one.

Other lines send a very different message, however, seemingly coming from the persecuted rather than the persecutor: “Nothing more wretched than what I must endure”; “Night after night, day after day / They strip your useless hopes away”; and especially:

How I made it back home nobody knows

Or how I survived so many blows

I been through hell, what good did it do?

My conscience is clear, what about you?

Richard Thomas points out that multiple songs on Tempest contain allusions to Homer’s Odyssey, including the passage above from “Pay in Blood.” He cleverly connects these Odyssean references to the bust of Athena beside Dylan on stage. The Harvard Classics professor explains:

It is a river goddess, a likeness of a statue group of Pallas Athena (Minerva). The group is outside the Parliament building in Vienna—suggesting a connection between democratic Austria and the ideal Athenian democracy, of which Athena is the patron goddess. The same river goddess is on the cover of Tempest. Why? I would say because Dylan transfigured into Odysseus, the wandering survivor of so many blows, quite naturally has with him a statue associated with the goddess, has taken on as his divine patron. (259)

Thomas makes a strong case for Odysseus as a source for “Pay in Blood,” but I hear other echoes as well. The perspective seems split between two divergent voices, one from an outlaw and the other from a martyr. Or is it a single figure combing both traits—a martyred outlaw? Dylan views Jesus in precisely those terms, and it wouldn’t be the first time he has sung in first-person from that vantage point. When he declares, “The more I take, the more I give / The more I die, the more I live,” he adopts the language of someone sacrificing himself to save others.

Most suggestive of all is the refrain: “I pay in blood but not my own.” From an executioner’s perspective, it’s a threat: if there’s blood to be spilled, it will be yours, not mine. But the same phrase might also be uttered by a holy warrior, as when Jesus told his disciples: “Think not that I am come to send peace on earth: I came not to send peace, but a sword” (Matthew 10:34). From a martyr’s perspective, the refrain invokes the spiritual redemption of blood sacrifice. Many years after the crucifixion, in a letter to early Roman Christians, the apostle Paul described Jesus’ blood sacrifice this way: “But God commendeth his love toward us, in that, while we were yet sinners, Christ died for us. Much more then, being now justified by his blood, we shall be saved from wrath through him” (Romans 5:8-9).

As recently as his 2022 interview with Jeff Slate, Dylan avowed, “I’m a religious person. I read the scriptures a lot, meditate and pray, light candles in church. I believe in damnation and salvation, as well as predestination. The Five Books of Moses, Pauline Epistles, Invocation of the Saints, all of it.” You don’t have to turn to interviews, however, to find supporting evidence: you can hear it in songs like “Pay in Blood.” There are barriers to fully appreciating this song on the album Tempest, where Dylan’s vocals are so ragged that it sounds like someone slit his throat. However, with his pipes unclogged and those obstacles removed at NKU, we can devote undistracted attention to this richly complex song about a martyred outlaw.

Dylan builds upon this sacrificial theme in the next song, “Lenny Bruce,” a deep cut from Shot of Love. Before it became a staple of the fall 2019 setlist, Dylan had only played “Lenny Bruce” live eight times in the 21st century. Frankly, the general consensus since the eighties had been that this was a throwaway song better left forgotten, a maudlin piece of schlocky doggerel.

The song has its defenders, however, and the freshest take I’ve ever heard comes from my friend Harrison Hewitt, better known in the Dylan Twitterverse as Harry Hew. He delivered the best presentation at the “World of Bob Dylan 2023” conference, calling out critics for being blind and deaf to Dylan’s pervasive sense of humor. I encourage you to read his paper in The Dylan Review, or for the full effect watch the Tulsa presentation on YouTube.

Harry quotes a couple notorious lines from “Lenny Bruce,” such as “Never robbed any churches nor cut off any babies’ heads / He just took the folks in high places and he shined a light in their beds.” Haters who mercilessly mock the song’s outrageousness seem oblivious to the possibility that this may have been Dylan’s entire point. Harry shines a light on this dimwitted misunderstanding:

So let me get this straight: Bob Dylan writes a song about a funny, outrageous figure, the song is funny and outrageous—and I am supposed to believe this was an accident? That those lines strike you and I and anybody who’s ever heard them as funny, but Bob Dylan—in writing the song, in recording the song, in singing the song on stage over 100 times—it’s never occurred to him that those lines are funny?

Having teed up his argument, he pulls out his driver and crushes it down the center of the fairway:

I don’t believe that. I don’t believe that for a second. I believe Bob Dylan knew exactly what he was doing. He knew Lenny Bruce lived on a lightning bolt – that Lenny Bruce took extreme chances, showed extreme courage, had extreme failings. So Dylan honors him by writing about him using extreme language. The line Dylan has about killing babies; Lenny Bruce said: ‘If there were absolute freedom, people would run over babies and charge admission.’ Dylan is saying, ‘Yeah, but not you, Lenny. You were one of the good ones.’ The whole song is like that. Dylan not only praises Bruce, he praises him in the language that Bruce spoke. It’s a clever song, and I applaud Dylan for not folding under the weight of everybody who says it’s stupid, or that it’s at best unintentionally funny.

Nailed it, Harry! I’ll admit to being one of those listeners who cringed when I first heard the song on Shot of Love, but I was wrong and stand corrected.

Even before attending Harry’s talk in 2023, Dylan converted me with his NKU ’19 performance of “Lenny Bruce.” In that case, it wasn’t the humor that won me over so much as the pathos and the mirror dynamics of identification. He sets the song up effectively by first establishing the martyred outlaw figure in “Pay in Blood.” The musical arrangement of “Lenny Bruce” is sparse, treating the song as a funeral dirge, led by Dylan’s somber piano and plaintive voice as head pallbearers. If he is supposed to be embarrassed by this song, someone forgot to inform him. He sings it straight and true.

This rendition of “Lenny Bruce” is reminiscent of “Roll on John,” the closing song on Tempest, an elegy for his murdered friend/rival John Lennon. Dylan didn’t know Bruce as well as he knew Lennon. Speaking in first-person voice he recalls: “I rode with him in a taxi once / Only for a mile and a half, seemed like it took a couple of months.” It’s hard to detach this memory from the footage of Dylan and Lennon’s strung-out taxi ride in Eat the Document.

Contemplating Bruce’s legacy, Dylan identifies with the dead comic and social critic. He goes so far as to conclude: “Lenny Bruce was bad / He was the brother that you never had.” No offense, David Zimmerman! Dylan sees himself reflected in the mirror of Bruce. Both were raised in Jewish families but adopted stage names when they started plying their trades as performers [Lenny Bruce was born Leonard Alfred Schneider]. Both spoke harsh truths to power and paid high prices for their irreverence: “They said he was sick, ’cause he didn’t play by the rules / He just showed the wise men of his day to be nothing more than fools”; and “He fought a war on a battlefield where every victory hurts.” [Actually, at NKU ’19 he sings, “where every wound still hurts.”]

Dylan praises Bruce as a revolutionary and denounces his detractors for hounding him into an early grave. The song first appeared on the last album in Dylan’s Christian trilogy. In that context, Bruce comes across as a type of messiah and martyr, roles Dylan had long connected with. Shot of Love came out in 1981, the year Dylan turned 40, and the year after 40-year-old John Lennon was gunned down. Surely Dylan was aware that Bruce was also 40 when he overdosed in his Hollywood home on August 3, 1966.

Five days earlier, on the other side of the country, 25-year-old Bob Dylan crashed his motorcycle near his home in Woodstock. The mysterious details of that accident and the true extent of Dylan’s injuries have long been questioned. Some speculate that Dylan faked the accident, or severely exaggerated it, as an excuse to get off the road and kick his drug habit. Others claim the wreck was quite serious and potentially life-threatening. We’ll probably never know exactly what happened. But pause to consider that, if the grimmest accounts are true, then Bob Dylan and Lenny Bruce almost died within a week of each other in 1966.

Listening to the 78-year-old singer’s heart-piercing vocals over a half-century later at NKU, it’s tempting to imagine that Dylan had this morbid synchronicity in mind. Their shared taxi ride begins to resemble a slow boat for two on the River Styx. As he sings in the revised lyrics of the first verse:

Lenny Bruce is dead, but his ghost lives on and on

Never made it to the Promised Land, never made it out of Babylon

He was an outlaw, so sad but true

More of an outlaw than even he ever knew

The comic never knew how influential his legacy would be, but the singer knows. “I’ve already outlived my life by far,” Dylan would sing the following year on “Mother of Muses.” This longevity gives him the advantage of hindsight and long-range perspective. He anoints Bruce as a holy outlaw, one of several in Dylan’s catalogue, following in the lineage of Woody Guthrie’s “Jesus Christ.” In the original lyrics, Dylan rated Bruce as his superior, deferentially conceding that the renegade was “more of an outlaw than you ever were.” By 2019, however, the Nobel laureate and elder statesman was willing to acknowledge his fellow rank among the pantheon of artist-outlaws.

The Nobel Prize prompted Dylan to ponder his legacy, and the resurrection of “Lenny Bruce” in 2019 fits squarely within this process of self-reassessment and artistic stock-taking. The Nobel committee situated Dylan within the august company of the literary canon. Maybe he was flattered by the compliment, but he also seems to have been unnerved. The Nobel Prize was the latest and grandest example of Dylan’s work being misconstrued by supposed experts who fundamentally misunderstood it. This experience summoned up the ghost of the dead comic: “‘There must be some way out of here,’ said the Joker to the Thief.” Dylan has devoted a lot of energy in the ensuing years to correcting the record, redefining his proper peers as bold performing artists like Lenny Bruce.

“Early Roman Kings” makes for an interesting selection to follow “Lenny Bruce.” The singer declares, “I come to bury not to praise,” riffing on Mark Antony’s famous eulogy in Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar: “Friends, Romans, countrymen, lend me your ears: / I come to bury Caesar, not to praise him” (3.2.74-75). It’s an appropriate follow-up to Dylan’s funeral oration honoring a different kind of martyr, an American king of comedy.

In “Early Roman Kings,” he describes the debauchery of an empire in its death throes. Contemporary American peddlers and meddlers follow ancient Roman footsteps down the road to ruin, dragging the nation behind them like a sack of loot. Nero allegedly played his fiddle while Rome burned. Sexton and Britt play down-and-dirty blues guitar, signaling through the flames of Trump-era America. In tonight’s setlist, Dylan alternates between songs of sacrifice and songs of corruption, his right hand drawing back while his left hand advances across the black and white keys.

For the lucky thirteenth song of the evening, Dylan reaches back to “Girl from the North Country,” a song he had been playing for over fifty years. Listening to Donnie Herron’s lovely violin, you’d think it were 150 years old, a tune that would fit right at home on the soundtrack of Ken Burns’s The Civil War.

I adore “Girl from the North Country”—well, most of the time. But I find tonight’s arrangement less satisfying than usual. It’s . just . . so . . . damn . . . . slow. It sounds like a winter song taken too literally: Jack Frost tinkles the ivories like he has frostbite, and the melody advances at the speed of a glacier. Great song, but belabored performance. Can’t win ’em all.

We transition straight from the evening’s most forgettable performance to its most memorable: “Not Dark Yet.” This song is scary! Absolutely haunting. Dylan takes us from the frozen tundra of “North Country” to a guided tour of the inferno in “Not Dark Yet.”

This performance is what the dark night of the soul feels like. It puts me in mind of one of Gerard Manley Hopkins’s “terrible sonnets” that begins:

I wake and feel the fell of dark, not day.

What hours, O what black hours we have spent

This night! what sights you, heart, saw; ways you went!

And more must, in yet longer light’s delay.

With witness I speak this. But where I say

Hours I mean years, mean life. And my lament

Is cries countless, cries like dead letter sent

To dearest him that lives alas! away.

“Not Dark Yet” emanates from the dead letter office in the dungeon of hell. Dylan wrote it so fine, but he sings it even better.

The sound makes “Not Dark Yet” the most captivating performance of the night. There’s an echo effect on Dylan’s voice, used quite deliberately to magnify the singer’s mental torture. The echo conjures up images of a condemned man in solitary confinement, the words reverberating off the bare walls of his cell, or pinballing around his skull. The inner and outer prisons have become one and the same. Dylan’s phrasing is lethal, but he also expertly employs pauses, insuring that he doesn’t compete against his own voice. The spellbinding reverb ripples through the arena: “It’s not dark yet [yet, yet, yet] / [Beat] / But it’s gettin’ there.”

There’s wonderful interplay between Dylan’s voice and Donnie Herron’s pedal steel guitar. Dylan stands center stage: no piano, no guitar, no defenses, no apologies, no reprieves. The other musicians eventually join in, adding sonic layers and building intensity, but they’re in no hurry. They gather slowly like a dark coven, stirring their cauldron and casting a curse. “Something wicked this way comes” (Macbeth 4.1.45). The effect is as chilling as it is exhilarating. Simply put, “Not Dark Yet” at NKU ’19 is one of the best performances Dylan has ever delivered in the Cincinnati area.

Outlaws and martyrs, saviors and criminals, damnation and redemption, heaven and hell—you just know Dylan is gonna play “Gotta Serve Somebody.” This was the first song on Dylan’s first Christian album Slow Train Coming, the dependable opener during his gospel tours, and the song from that era with the longest road life. The 2019 lyrics are almost entirely rewritten from the 1979 original, but the basic premise of the refrain remains intact: “You gotta serve somebody / Yeah, serve somebody / Might be the Devil, might be the Lord / You gotta serve somebody.”

For much of tonight’s setlist, the pendulum swings back and forth between dark and light, slow and fast, infernal and divine. “Gotta Serve Somebody” perfectly encapsulates the dualism of the NKU ’19 concert. As for Dylan and his house, he serves the Lord. Nevertheless, he is a musical cartographer for both paths over the course of the concert, presenting characters who take the high road and those who take the low road (both the rough and the rowdy ways). He walks in their shoes and sings in their voices.

The final song of the evening is “It Takes a Lot to Laugh, It Takes a Train to Cry.” This is his only documented performance of the song in the Cincinnati area, though he might have played it at the November ’65 show. That Music Hall concert was part of Dylan’s first tour with a backing band after going electric at Newport in July 1965 with plugged-in performances of “Maggie’s Farm,” “Like a Rolling Stone,” and “Phantom Engineer”—which later became “It Takes a Lot to Laugh, It Takes a Train to Cry.” The song has proven a fertile source for titles, from Steely Dan’s debut album Can’t Buy a Thrill, to Substack superstar Ray Padgett’s Flagging Down the Double E’s.

John Spoor managed to sneak this video of the closer:

“It Takes a Lot to Laugh, It Takes a Train to Cry” is a bluesy grinder that plays to the strengths of the NET band. There’s a cool effect a couple of times where they all suddenly stop playing, then we hear a lone guitar lick, then answers from other players as the music starts picking up momentum again, as if the Little Engine Who Could temporarily got stalled before making it up the hill.

Dylan cries like a train whistle or a lonesome whippoorwill: “I wanna be your lover, baby / I don’t wanna be your booooossss.” Hey, you be whatever you wanna be! You’re the phantom engineer of this love train, Bobby, and we’re all on board. Dylan and mates strike the pose, drink in their well-earned ovation, and exit the stage, ready to ride the rails north to Akron for the next night’s show. Little did they suspect that there were only a few more stops before reaching the terminal station.

The fall of 2019 marked the final leg of the NET. Exactly one month later, on December 8, 2019, Dylan played his last NET concert in Washington, D.C. He didn’t foresee the end of this long run, and it didn’t happen voluntarily. The abrupt conclusion was forced by the global outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic. For the first time since 1985, Bob Dylan did not tour at all in 2020. With no forewarning or fanfare, the Never Ending Tour ended.

Dylan’s desire to make music and deliver it live to the people did not end, however. We will pick up the story in the next chapter with the beginning of the new Rough and Rowdy Ways Tour in 2021.

Works Cited

Baldwin, James. “Sonny’s Blues.” The Story and Its Writer, 6th edition. Ed. Ann Charters. Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2003, 38-60.

Bootleg audio recording (LB-14490). Taper unknown, remastered by Bennyboy. BB&T Arena, Highland Heights (8 November 2019).

Dylan, Bob. “Nobel Lecture in Literature.” The Nobel Prize (4 June 2017). https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/literature/2016/dylan/lecture/.

---. Official Song Lyrics. The Official Website of Bob Dylan.

https://www.bobdylan.com/.

Hewitt, Harrison. “How Long Can We Falsify and Deny What Is Real: Bob Dylan Is the Funniest Person Alive, and Why We Need to Talk About It.” The Dylan Review 5.1 (2023), https://thedylanreview.org/2023/08/26/world-of-bob-dylan-how-long-can-we-falsify-and-deny-what-is-real-bob-dylan-is-the-funniest-person-alive-and-why-we-need-to-talk-about-it/.

The Holy Bible. King James Version.

Hopkins, Gerard Manley. “I wake and feel the fell of dark, not day.” Poetry Foundation, https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/44396/i-wake-and-feel-the-fell-of-dark-not-day.

Padgett, Ray. “Poet James Ragan Remembers Touring the Soviet Union with Bob Dylan.” Flagging Down the Double E’s (25 July 2024),

.

Ragan, James. “The Tent People of Beverly Hills.” The Poetry of James Ragan, https://www.dorothyswebsite.org/2005Guestpoem_6.html.

Shakespeare, William. Julius Caesar. Arden Shakespeare Third Series. Ed. David Daniell. Bloomsbury, 1998.

---. Macbeth. Arden Shakespeare Second Series. Ed. Kenneth Muir. Bloomsbury, 1997.

Slate, Jeff. “Bob Dylan Q&A about ‘The Philosophy of Modern Song.’” Wall Street Journal (19 December 2022), http://www.bobdylan.com/news/bob-dylan-interviewed-by-wall-street-journals-jeff-slate/.

Thomas, Richard F. Why Bob Dylan Matters. Dey St., 2017.

Vance, JD. Hillbilly Elegy: A Memoir of a Family and Culture in Crisis. Harper, 2016.

"The notorious rasp that crept in around the turn of the century and spread like kudzu has been beaten back"

Great line