Dylan in Cincinnati: August 2012

On September 4, 2012, New York Times music critic Jon Pareles attended Dylan’s show at the newly renovated Capitol Theatre in Port Chester, New York. Pareles prefaced his review with this disclaimer: “A current Dylan concert is always a matter of shifting expectations. At first his voice sounds impossibly ramshackle, just a fogbound rasp. But soon, at least on a good night, his willful phrasing and conversational nuances come through.” Pareles accurately captures the state of the Never Ending Tour in the second decade of the 21st century. Your first reaction was to shake your head over the woeful condition of his voice. And yet, if you remained receptive, Dylan still arrived in your town bearing gifts, wrapped inside that fogbound rasp.

This was certainly the case a week earlier when Dylan played the PNC Pavilion, located near the northern banks of the Ohio River, on the outskirts of Cincinnati. Having listened to the bootleg many times, four performances stand out for what they illustrate about Dylan’s relationship with his songs and his audiences at this stage of his career. The songs I want to share with you from this 2012 concert—“Blind Willie McTell,” “Spirit on the Water,” “Ballad of a Thin Man,” and “Blowin’ in the Wind”—showcase Dylan’s 21st century performance strategies for drawing closer and fostering intimacy with his audience. In other instances, however, we can hear Dylan “splaying his anthems,” to borrow a phrase from my friend Rob Reginio, who adapted it from the poet Nathaniel Mackey.

In his excellent chapter for Erin Callahan and Court Carney’s book on setlists, Rob argues that Dylan does not treat his so-called anthems as sacrosanct. Many audience members approach these songs with nostalgia, but the performer does not. Instead, Rob asserts, Dylan’s approach is “to be vexed by the past, to feel a disquieting, spectral presence of the past, of vanished utopias, in the present” (134). I think you can hear a couple good examples of “splayed anthems” in this 2012 concert, where Dylan uses tactics of estrangement to maintain a critical distance from his old classics and from the audiences who adore them.

Dylan Context

Our favorite troubadour passed a notable milestone on March 19, 2012: the 50th anniversary of the release of Bob Dylan, his debut album. Later in September 2012 he released his 35th studio album, Tempest. Unfortunately, this was a couple weeks after his Cincinnati concert, so he didn’t play any new material this time through town. Not to worry: he returned the following summer to Riverbend and included several Tempest songs in that setlist.

Dylan brought the same band with him to Cincinnati’s PNC Pavilion as he did for the 2010 concert at NKU. Well, there was one marvelous addition—the McCrary Sisters! This gospel quartet came out for the encore to sing “Blowin’ in the Wind” with Dylan.

Readers of Shadow Chasing will fondly recall that Regina McCrary was a mainstay of the Queens of Rhythm backing vocalists during Dylan’s gospel years (1979-81), including his two concerts at Music Hall in 1981. The 2012 Pavilion concert was the first time she ever accompanied Dylan with her sisters. [They would eventually join him one more time, the following year at their home base of Nashville.] The quartet’s surprise appearance on this night in Cincinnati made for an extra special treat.

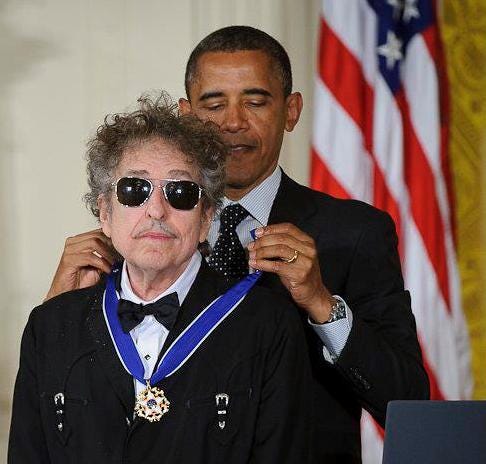

One other special distinction deserves mention. On May 29, 2012, President Barack Obama presented Dylan with the country’s highest civilian honor, the Presidential Medal of Freedom. The President concluded his induction remarks on a personal note: “There is not a bigger giant in the history of American music. All these years later, he’s still chasing that sound, still searching for a little bit of truth. And I have to say that I am a really big fan.”

Ohio/Kentucky Context

The adjacent states of Ohio and Kentucky had outsized influence on the national political scene during this period. In part we have the Electoral College to thank. For the benefit of readers outside the country, I should explain that the U.S. President is chosen by an arcane method involving the Electoral College, which assigns varying numbers of votes per state depending upon its population. The candidate who wins the most individual votes in each state wins the state’s full slate of electoral votes (Maine and Nebraska are exceptions, but let’s not get too deep in the weeds). The upshot is that the U.S. doesn’t really hold a single federal election for president every four years—it holds fifty state elections. This means that it’s possible to win the popular vote nationwide and still lose the presidency—just ask Al Gore in 2000 or Hillary Clinton in 2016.

The outcome in most states is assured long before the election takes place. Therefore, each presidential election is determined by only a handful of states that could plausibly swing either way. After many decades as a dependably Republican state, Ohio shifted into a swing state in the first decade of the 21st century. One of the linchpins to Barack Obama’s victory in 2008 was winning Ohio, a prize he would take home again nine weeks after Dylan’s 2012 concert in Cincinnati.

But it wasn’t all about electoral politics. Some of President Obama’s thorniest adversaries hailed from Ohio and Kentucky, too. He locked horns several times with Republican House Minority Leader, and later Speaker of the House, John Boehner.

Boehner is a native of Cincinnati and a graduate of Xavier University where I teach. Despite their sharp political differences, Boehner and Obama occasionally managed to work together semi-cordially, at least at first. As Obama writes in A Promised Land,

Boehner was […] an affable, gravel-voiced son of a bartender from outside Cincinnati. With his chain-smoking and perpetual tan, his love of golf and a good merlot, he felt familiar to me, cut from the same cloth as many of the Republicans I’d gotten to know as a state legislator in Springfield—regular guys who didn’t stray from the party line or the lobbyists who kept them in power but who also didn’t consider politics a blood sport and might even work with you if it didn’t cost them too much politically. (246)

Their relationship gradually soured as Boehner bent to the will of his right flank. Among the ungovernable radicals in his party, any bipartisan compromise with Obama was viewed as a cocktail of betrayal and cowardice. Boehner ultimately chose hemlock instead, stepping down from the speakership in 2015 before the end of Obama’s second term.

Mitch McConnell was an even bigger nemesis. Elected to the U.S. Senate in 1984, McConnell is the longest serving U.S. Senator in Kentucky history as well as the longest serving leader of the Senate Republican Conference. He notoriously made it his chief mission to deny President Obama a second term. Although that effort failed, his obstructionist tactics stymied much of Obama’s political agenda.

Obama reserves harsher words for McConnell in A Promised Land:

Short, owlish, with a smooth Kentucky accent, McConnell seemed an unlikely Republican leader. He showed no aptitude for schmoozing, backslapping, or rousing oratory. As far as anyone could tell, he had no close friends even in his own caucus; nor did he appear to have any strong convictions […]. But what McConnell lacked in charisma or interest in policy, he more than made up for in discipline, shrewdness, and shamelessness—all of which he employed in the single-minded and dispassionate pursuit of power. (245-46)

McConnell is less than a year younger than Bob Dylan. Given his adversarial relationship with the country’s first African American President, you may be surprised to learn that, as an undergrad at the University of Louisville, McConnell attended the March on Washington in 1963. Sort of. To be more precise, he was a congressional intern who witnessed the event from afar, too distant to hear MLK’s speech or Dylan’s performance. But hey, he was there.

The junior U.S. Senator from Kentucky was born in 1963. Rand Paul was part of a wave of Republicans elected in the 2010 midterm elections, and he quickly distinguished himself as one of the most outspoken firebrands for the so-called Tea Party movement.

Taking their name from the Boston Tea Party staged by nationalists in the buildup to the American Revolutionary War, these ultra-conservatives opposed Obama at every turn. Obama was reelected in 2012, but in retrospect the Tea Party seems a harbinger of things to come, laying the groundwork for a reactionary backlash which would result in the election of Donald Trump four years later.

Keep these shifting political crosswinds in mind as we make our way down to the riverside for Dylan’s 2012 concert at PNC Pavilion.

The Concert

When: August 26, 2012

Where: PNC Pavilion in Anderson Township

Opener: Leon Russell

Band: Bob Dylan (vocals, harmonica, and piano/keyboard); Tony Garnier (bass); Donnie Herron (violin, mandolin, banjo, and steel guitar); Stu Kimball (guitar); The McCrary Sisters (Alfreda, Ann, Deborah, and Regina) (backup vocals); George Receli (drums and percussion); Charlie Sexton (guitar)

Setlist:

1. “Leopard-Skin Pill-Box Hat”

2. “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue”

3. “Things Have Changed”

4. “Tangled Up in Blue”

5. “Honest with Me”

6. “Blind Willie McTell”

7. “Tweedle Dee & Tweedle Dum”

8. “Spirit on the Water”

9. “High Water (for Charley Patton)

10. “Visions of Johanna”

11. “Highway 61 Revisited”

12. “Tryin’ to Get to Heaven”

13. “Thunder on the Mountain”

14. “Ballad of a Thin Man”

15. “Like a Rolling Stone”

16. “All Along the Watchtower”

*

17. “Blowin’ in the Wind”

“Blind Willie McTell”

“Blind Willie McTell” is one of Dylan’s greatest songs. If you’re like me, you knew this song was a masterpiece from the instant you first heard it on The Bootleg Series, Volumes 1-3, released in 1991. Apparently the only person who didn’t like what he heard was Dylan himself, who recorded it for the 1983 Infidels sessions but left it off the final cut, much to the bafflement of producer Mark Knopfler. [Sidenote: Knopfler was initially announced as the opener for the Pavilion concert, but instead Leon Russell filled in. Knopfler later joined the NET in October, and by November he was regularly joining Dylan’s band on guitar for a few songs, including a guest feature on “Blind Willie McTell” on November 9th in Chicago.] The song entered Dylan’s live rotation in 1997, and was eventually played in concert over two hundred times, including twice in Cincinnati; first at the largely forgettable 2007 concert at Taft Theatre, and again, memorably, at the Pavilion in 2012.

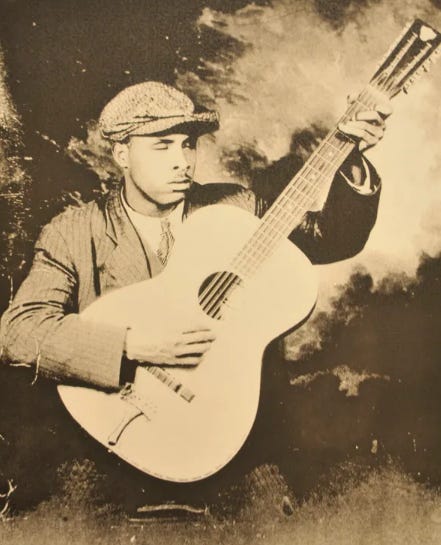

“Blind Willie McTell” contains multitudes. I’m an English professor, and this is a very teachable song, with multiple levels of meaning worth unpacking. It seems to be told from the perspective of a dying man—“I’m gazing out the window of the St. James Hotel”—which alludes to the two main musical sources of the song, “St. James Infirmary” and McTell’s “The Dyin’ Crapshooter’s Blues.”

Listening to the blues sends the singer back in time. He envisions traveling tent shows and prison chain gangs, he confronts the shameful legacy of slavery and the Civil War, and he conjures ghosts from the horrific Middle Passage across the Atlantic Ocean. In the process, Dylan connects his Jewish cultural roots with the music of the Deep South by way of shared suffering, from the Egyptian captivity to the slave trade abductions of West Africa.

Heavy stuff. But there is nothing depressing or ponderous about the buoyant music coming from the Pavilion stage in 2012:

The music slinks and saunters, punctuated by some thrilling harmonica by Dylan. The band takes a song cloaked in the pall of death and bound by the historical roots of the blues in slavery, and they breathe fresh life into “Blind Willie McTell.” As a writer and teacher, I’m accustomed to approaching it with reverence. But Dylan is having none of that tonight. Someone forgot to inform him that this song is supposed to be profound. He actually seems intent upon entertaining us with “Blind Willie McTell.” And he succeeds, as the Cincinnati crowd warmly attests.

Dylan’s vocals are raspy yet randy. This performance is seductive. The singer grinds with the stripper in the second verse: “Them charcoal gypsy maidens / Can strut their feathers well.” Dylan struts his way through this performance as if he’s a burlesque dancer himself. I’m not talking about his physical movements on stage; I’m talking about his coy, pouting, come-hither vocals. He inserts brief pauses through the delivery, as if he’s teasing us, winking before completing each line: “Them charcoal [pause] gypsy maidens / Can strut [pause] their feathers [pause] well.” Maybe nobody can sing the blues like Blind Willie McTell, but nobody can sing “Blind Willie McTell” like Bob Dylan. And tonight he sings like Josephine Baker dances.

The music works hand in rhinestone-studded glove with the vocals to accomplish this metamorphosis. After Dylan is done delivering the lyrics, listen to the outro. The band accentuates the bawdy saloon mood, replicating the singer’s pauses with multiple false endings. They stop, making you think the song is over, only to start back up. No broke-down engines here: the boys are revvin’ it up and rarin’ to go! There should be chorus girls in fishnet stockings high-kicking their way through the end of this song. Who knew that “Blind Willie McTell” could actually be sexy?

“Spirit on the Water”

Dylan turns on the charm with an irresistible “Spirit on the Water.” Despite originally appearing on an album titled Modern Times, the song sounds old-timey, a sweet shuffle that would fit well in a 1920s dance hall. What makes the song so appealing at the Pavilion is Dylan’s beguiling vocals. He already displayed his flirtatiousness in “Blind Willie McTell,” but “Spirit on the Water” is less about arousal and more about courtship. Anticipating later songs like “I’ve Made Up My Mind to Give Myself to You,” “Spirit on the Water” comes across as a love song to his audience.

When you first listen to the song on Modern Times, the singer seems to be pleading his case with the woman he loves, a woman who is tempted, but is still weighing her options. In live performance, however, there can be no doubt that Dylan is directing the song squarely at us, the people staring lovingly back at him on stage.

Been traveling by land

Traveling through the dawn of the day

You’re always on my mind

I can’t stay away

I’d forgotten about you—how could I?

But you turned up again

I always knew

We were meant to be more than friends

When you’re near

It’s just as plain as it can be

I’m wild about you, gal

You ought to be a fool about me

The song is tailor made for Dylan’s reunion with his devoted audiences in hundreds of towns across the globe. He has been traveling the world and maybe hasn’t passed this way in a while. But he’s so glad to see that we still care enough to come out and greet him, and he wants us to know that the feeling is mutual. He needs us like we need him:

Ha! Life without you

Wouldn’t mean a thing to me

If I can’t have you

I’ll throw my love into the deep blue sea

Hmm, will the Ohio River do? It’s within eyeshot of the Pavilion. But nobody is rejecting anybody’s love here tonight, Bob. He speaks for us both when he sings

When I’m with you

I’m a thousand times happier than I can ever say

What does it matter

What price I pay?

My favorite moment, where it’s so touchingly obvious that this serenade is a fully reciprocated declaration of love, comes at the end. The audience turns the monologue into a dialogue by inserting its response to his questions:

Dylan: You think I’m over the HILL?

Audience: No!!

Dylan: You think I’m past my prime?

Audience: No!!

Dylan: Let me see what you got

Audience: [Whoops and cheers]

Dylan: We can have a whoppin’ good time!

Audience: Yeah!!

If you followed the tour around, such exchanges might start to sound wearily predictable. But the majority of the Cincinnati audience probably hadn’t seen the man in years, which is why their exhortations sound so heartfelt and endearing. Dylan wears his heart on his sleeve here, so I will, too—I adore this performance of “Spirit on the Water”!

“Ballad of a Thin Man”

There’s nothing else quite like “Ballad of a Thin Man” in the Dylan canon. If you care enough about his art to read this newsletter, then I feel confident in predicting that you’ve listened to “Ballad of a Thin Man” a lot. Dylan has certainly played it a lot. According to bobserve, he has played it in concert 1,322 times, ranking it as his sixth most performed song. He has sung it nine times in Cincinnati, ranking it third behind “Like a Rolling Stone” (11) and “All Along the Watchtower” (10). So much for the numbers.

Now hear this: I have never heard Dylan sing “Ballad of Thin Man” like he does at the Pavilion in 2012—with an echo!

When the echo first started, I thought I must be imagining it, or maybe I had gotten hold of a faulty bootleg. Nope. Dylan’s crew rigged the audio system to play his voice echoing back at the end of most lines. It doesn’t happen immediately. Dylan sings the first verse straight through with no echo. But then he gets to the chorus and we hear:

You try so hard

But you don’t understand

What you’re gonna say

When you get home

Something is happening

And you don’t know what it is

Do ya! [Do ya!]

Mister! [Mister!]

Jones! [Jones!]

The audience, which has been pretty rowdy during much of this show, becomes hushed, concentrating on the unexpected effect, either in admiration or confusion or a combination of both. They lay back for much of the performance, contemplating the novelty, muttering the occasional “huh” or “wow” or “cool.” They don’t really snap out of it, remembering that audiences are meant to whoop and cheer, until the end when Dylan busts out his harmonica.

The effect is strikingly different from “Blind Willie McTell” and “Spirit on the Water.” This is an experiment in estrangement, akin to Bertolt Brecht’s alienation effect [Verfremdungseffekt] or what the Russian formalists called defamiliarization [ostranenie]. The lyrical content of “Ballad of a Thin Man” is already about the experience of alienation. The echo effect marries form with content, alienating the familiar song from the Jones-like fans who don’t know what’s going on here.

In his influential 1917 essay “Art as Technique,” Viktor Shklovsky observes, “If we start to examine the general laws of perception, we see that as perception becomes habitual, it becomes automatic” (2). He sees this sort of routine, mechanized thoughtlessness as the antithesis of true art. According to Shklovsky, “art exists that one may recover the sensation of life; it exists to make one feel things, to make the stone stony. The purpose of art is to impart the sensation of things as they are perceived and not as they are known. The technique of art is to make objects ‘unfamiliar’” (2).

This notion of defamiliarization influenced the German playwright Bertolt Brecht in his approach to theatrical performance. Brecht first explains Verfremdungseffekt [aka alienation effect, A-effect, V-effect] in the 1935 essay “Alienation Effects in Chinese Acting.” In this style of performance, “The artist’s object is to appear strange and even surprising to the audience. He achieves this by looking strangely at himself and his work. As a result, everything put forward by him has a touch of the amazing. Everyday things are thereby raised above the level of the obvious and automatic” (92).

I’m not saying that Dylan was familiar with Shklovsky and Brecht and intentionally employed their theories. [Though he’s on record in Chronicles (272-76) with his admiration for Brecht & Weill’s “Pirate Jenny,” and he was floored by the performance by Lotte Lenya, the premier purveyor of Brecht’s acting techniques.] What I am saying is that Shklovsky and Brecht provide a wider artistic context and vocabulary for appreciating how Dylan defamiliarizes and alienates “Ballad of a Thin Man” in his 2012 Pavilion performance.

In his 1940 essay “Short Description of a New Technique of Acting which Produces an Alienation Effect,” Brecht explains, “The A-effect consists in turning the object […] from something ordinary, familiar, immediately accessible, into something peculiar, striking and unexpected” (143). Peculiar, striking, and unexpected: that’s exactly how “Ballad of a Thin Man” struck each of us the first time we heard it—ooh, how creepy! With time and overfamiliarity, however, the song runs the risk of becoming tamed through repetition. Our reaction can become habitual and automatic. One jarring effect of the echo in 2012 is that it restores the song’s weirdness and wildness—it makes “Ballad of a Thin Man” strange again.

Dylan doesn’t overthink these things—but I do! He probably just heard the echo accidentally in rehearsal, thought it sounded cool, and asked the crew to include it in concert. Simple as that. Having listened to it repeatedly, however, it resonates strongly with me because it highlights fundamental issues about Dylan in performance. The echo alters his rapport with the audience, not drawing them closer this time, but distancing and displacing them.

One form of echo Dylan has long frustrated for his fans is the custom of singing along with our favorite songs. Normally, I’m all for this ritual. For example, some of my most ecstatic experiences at Springsteen concerts have come while belting out “Born to Run” in unison with thousands of fellow worshippers doing the Stations of the Boss. Now go and try this at a Dylan concert and see how far it gets you.

As Rob Reginio observes, “Dylan the songwriter has a knack for composing anthemic songs that people want and expect to sing along with, but Dylan the performer seems unnerved by people singing along with his songs and instinctively wants to alter his vocal delivery in order to discourage this call-and-response practice among his live audiences” (135). Dylan’s constantly evolving musical arrangements, combined with his idiosyncratic vocal stylings, make it difficult sometimes to even recognize his songs, let alone harmonize with them. He issues calls that resist response.

In refusing to pander to audiences’ desires to sing along with his classics, Dylan comes across to detractors as cantankerous and contrarian. But I don’t think the impulse comes from a place of antagonism. Dylan lives for live performance. He surely appreciates that the ticket-buying public has allowed him to pursue his vocation long past the age when other singers have been forced to retire for lack of popular interest. Audiences are his friends and patrons, not his enemies, as he gratefully acknowledges in songs like “Spirit on the Water.” He has no motive to wantonly piss us off.

But he owes even more to the songs themselves, and he honors that sacred obligation by keeping them fresh. The way he does that is by being as fully present in the moment as possible while singing them. As exhilarating as the group singalong can feel from our side of the footlights, consider it from the perspective of the guy on stage who repeats that experience night after night, a hundred times a year, decade after decade. How does it feel? It feels routine, unless you devise ways to disrupt the familiar patterns.

“Habit is a great deadener,” writes Samuel Beckett in Waiting for Godot (84). Dylan is engaged in an endless war against the narcosis of habit. The echo effect on “Ballad of a Thin Man” is just one novel way to jolt new life into an old classic. But it comes at a price.

The echo disorients and displaces the audience. “Oh my God, am I here all alone?” It kind of sounds like it, right? Dylan closes off the space normally reserved for audience response and fills it up with his own voice. He is both Narcissus and Echo. He opts for self-dialogue in place of an interaction with the dumbfounded listeners in front of him. “You hand in your ticket / And you go watch the geek.” The geek on the Pavilion stage doesn’t consume the heads of chickens: he gobbles up the song itself then hands his audience the bone.

“Blowin’ in the Wind”

If you’ve heard of this 2012 Cincinnati concert before, it’s because of the surprise appearance by the McCrary Sisters. If you weren’t lucky enough to be there, a fan did you the favor of shooting this video. It’s shaky and out of focus at times, but for the most part the visuals are decent and the audio impeccable. I hope you enjoy it as much as Tony Garnier, who beams with delight throughout the performance.

There’s a slow musical intro with audible humming from the sisters as they get the tempo down. They accompany Dylan with rhythmic oohs, then they come in strong with supporting vocals on the refrain: “The answer my friend / Is blowin’ in the wind / The answer is blowin’ in the wind.” This is not the grand gospel choir arrangement Dylan used in 1980. It’s comparatively subdued, but still poignant, a real soul stirrer. As the song progresses and the sisters get warmed up, they get more active, testifying that they’re filled with the holy spirit in this Sunday evening service. Then Dylan leaves his piano bench and joins the choir center stage for the climactic conclusion, letting his harmonica do the talking for him. Spirit on the water by the banks of the Ohio.

When Ray Padgett interviewed Regina McCrary for Flagging Down the Double E’s, he asked about the circumstances behind her appearances with Dylan at Cincinnati in 2012 and Nashville in 2013. She explained, “He came to town and he called me and told me he was coming. I said, ‘Do you still end your show with ‘Blowin’ in the Wind’?’ He said, ‘Yes.’ I said, ‘Well, my sisters and I are going to come up there and sing with you.’ He laughed and said, ‘Okay, come on.’” They apparently didn’t fit in time to rehearse beforehand. As she told Ray, “Like I said, when I first met him, that was one of the songs I remembered from way back. My sisters and all of us already knew that. We just showed up on stage and he trusted that we know what we were doing.” Indeed they did.

The concept of echo applies in different but interesting ways to the Pavilion performance of “Blowin’ in the Wind.” In “Ballad of a Thin Man,” Dylan essentially performed a disorienting duet with himself. Then in the concert closer “Blowin’ in the Wind” we encounter a variant echo. “The answer is blowin’ in the wind” feels like Echo x 4 answering Narcissus by repeating back his words. The sisters harmonize beautifully with each other, but not with Dylan, who darts away from harmony like a fly dodging a swatter. Nevertheless, the effect of these intermingling voices is fascinating, allowing this lucky Cincinnati crowd to hear a “Blowin’ in the Wind” unlike any other in 2012.

Isn’t Dylan always engaged in a duet with himself when singing his sixties anthems? Whether you’ve been listening to Dylan from the beginning of his career, or you entered the flow further downstream, chances are you first fell in love with his music through officially released recordings. Those are the versions you’ve heard the most, and even if Dylan goes out of his way to prevent you from singing along in concert, you still harbor that default version within.

If audiences were as fully committed to being in the moment as Dylan the performer is, then they’d check that baggage at the gate and simply accept the show in front of them for what it is, adopting the “NET consciousness” advocated by Lee Marshall (215). Fair enough, but easier said than done. In practice, the echo of that prior performance tends to linger as an internal benchmark against which all subsequent performances are judged.

As drama theorist Marvin Carlson puts it in The Haunted Stage, referring to a comparable effect for stage actors,

The recycled body of an actor, already a complex bearer of semiotic messages, will almost inevitably in a new role evoke the ghost or ghosts of previous roles if they have made any impression whatever on the audience, a phenomenon that often colors and indeed may dominate the reception process. […] Even when an actor strives to vary his roles, he is, especially as his reputation grows, entrapped by the memories of his public, so that each new appearance requires a renegotiation with those memories. (8-9)

Dylan invited the McCrary Sisters to join him on stage and seems to enjoy their presence and contributions. He doesn’t invite the ghosts of his former selves to accompany him, but their spectral aura is palpable just the same, echoing in the minds of many listeners, and there’s really nothing he can do to stop it.

Seeing and hearing Regina McCrary on stage with Dylan conjures up a specific set of echoes and specters for me from the 1980 Warfield residency in San Francisco. I studied this series of concerts extensively for Erin and Court’s setlist book, which in turn inspired my Dylan in Cincinnati project closer to home. The 1980 Warfield concerts marked an important turning point for Dylan, as he began reintroducing his pre-conversion material into concert and reintegrating those secular songs with his born-again songs. A high point each night came in the encore with a jubilant gospel arrangement of “Blowin’ in the Wind,” enhanced by the inspirational backing vocals of Regina McCrary and the other Queens of Rhythm. Here is a recording of the song from the final night of the residency on November 22, 1980:

Another standout moment most nights was a duet between McCrary and Dylan on the old folk song “Mary from the Wild Moor.” Here is the very first performance from November 12, with Regina on autoharp:

Should we take it for granted that the wind is blowing in a positive direction in “Blowin’ in the Wind”? It was certainly perceived that way by the civil rights activists who embraced the song as an anthem in the early sixties. But it’s interesting to set “Blowin’ in the Wind” alongside “Mary from the Wild Moor,” a song equally dominated by a strong gale, only this one leads to the death of an entire family “from the wind that blew across the wild moor.”

How about the 2012 Pavilion performance, transplanted to Cincinnati fifty years after Dylan penned his most enduring anthem? Does the song still herald hope for progress on the perennial problems of war and racism? I’d like the think so. The soaring voices of the McCrary Sisters help lift the song up, and the optics of Dylan and his band performing the song with a quartet of amazing African American singers reinforces the idyllic dream of integration and unity.

And yet.

Throughout this project, I’ve stressed that when and where a performance takes place matters. But I should also emphasize that when and where you listen to that performance matters, too. In this case, my response to “Blowin’ in the Wind” isn’t determined so much by its original 1962 civil rights context, nor even its 2012 context leading up to the reelection of President Obama. Instead, I’m preoccupied by the wreckage that has piled up in the dozen years since that milestone.

On November 4, 2008, the night Barack Obama was elected President, Dylan was playing in Minneapolis. Before launching into the concert’s final song, he briefly reflected upon the historical significance of the moment. “Me, I was born in 1941. That was the year they bombed Pearl Harbor. I’ve been living in a world of darkness ever since. But it looks like things are gonna change now.” Dylan and the band then performed “Blowin’ in the Wind.”

Gearing up for the 2012 reelection campaign, President Obama encouraged hope for progressive social change through his official campaign slogan “Forward.” But in hindsight we can perceive a drastic turn in the weather, a shift in the political winds blowing fiercely backwards, hellbent on undoing so much of that progress. Four years later, these winds would sweep Donald Trump into office, a belligerent blowhard nostalgic for a return to the past, not just to pre-Obama America but to pre-civil rights era America. No one could have anticipated those developments in August 2012, as the Cincinnati audience filed out to the parking lot after an extra special “Blowin’ in the Wind.”

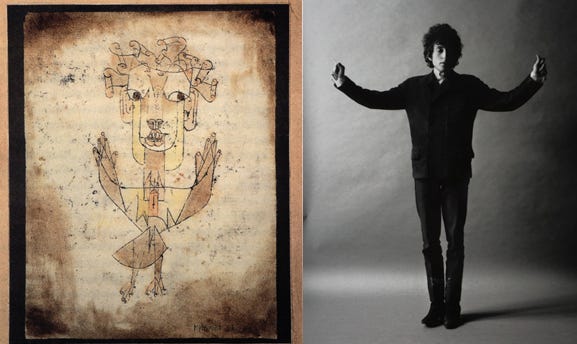

Listening to the 2012 performance now, and knowing what came after, puts me in a melancholy mood. I hear “Blowin’ in the Wind,” but I see the Angel of History. Gazing at a painting by Paul Klee, Walter Benjamin had a vision of an angel, splayed by history and blowin’ in the wind:

His face is turned toward the past. Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage and hurls it in front of his feet. The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing in from Paradise; it has got caught in his wings with such a violence that the angel can no longer close them. The storm irresistibly propels him into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows skyward. This storm is what we call progress.

Works Cited

Beckett, Samuel. Waiting for Godot. The Complete Dramatic Works. Faber and Faber, 1986. 7-88.

Benjamin, Walter. “On the Concept of History.” https://www.sfu.ca/~andrewf/CONCEPT2.html.

Bootleg audio recording (LB-7447). Unknown taper. Warfield Theatre, San Francisco, 12 November 1980.

Bootleg audio recording (LB-11304). Taped by Dogboy. Warfield Theatre, San Francisco, 22 November 1980.

Bootleg audio recording (LB-10357). Unknown taper. PNC Pavilion, Cincinnati, 26 August 2012.

Brecht, Bertolt. Brecht on Theatre: The Development of an Aesthetic. Trans. and ed. John Willett. Hill and Wang, 1964.

Carlson, Marvin. The Haunted Stage: The Theatre as Memory Machine. U of Michigan P, 2001.

Dylan, Bob. Chronicles, Volume One. Simon & Schuster, 2004.

---. Official Lyrics. The Official Website of Bob Dylan.

https://www.bobdylan.com/.

Marshall, Lee. Bob Dylan: The Never Ending Star. Polity, 2007.

Obama, Barack. A Promised Land. Crown, 2020.

Padgett, Ray. “Regina McCrary Talks about Singing Gospel with Bob Dylan.” Flagging Down the Double E’s (1 November 2021),

.

Pareles, Jon. “A Jovial Dylan Celebrates Reopening of Capitol Theater.” New York Times (5 September 2012), https://www.nytimes.com/2012/09/06/arts/music/a-jovial-dylan-celebrates-reopening-of-capitol-theatre.html.

Reginio, Rob. “Bob Dylan’s Splayed Anthems.” The Politics and Power of Bob Dylan’s Live Performances: Play a Song for Me. Routledge, 2024. 133-44.

Shklovsky, Viktor. “Art as Technique.” https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/arts/english/currentstudents/undergraduate/modules/fulllist/first/en122/lecturelist-2015-16-2/shklovsky.pdf.

Spoor, John. “Bob Dylan & The McCrary Sisters – Blowin’ in the Wind 26 Augustus 2012 PNC Pavilion at Riverbend Cin.” YouTube (1 January 2024).

I'm saving this as an end of Friday treat for myself, but I couldn't resist a quick glance and my eye alighted on an extraordinary sentence, one that magically encapsulates all that Dylan is about:

"Dylan is engaged in an endless war against the narcosis of habit."

Take a well-deserved bow, Mr Herren, for that line alone, far less the rest of this engrossing series.

Somehow, Graley, you make me care deeply about performances I never even would have known about otherwise. I go from ignorance and indolence to curiosity and enthusiasm. That, my friend, is defamiliarization.