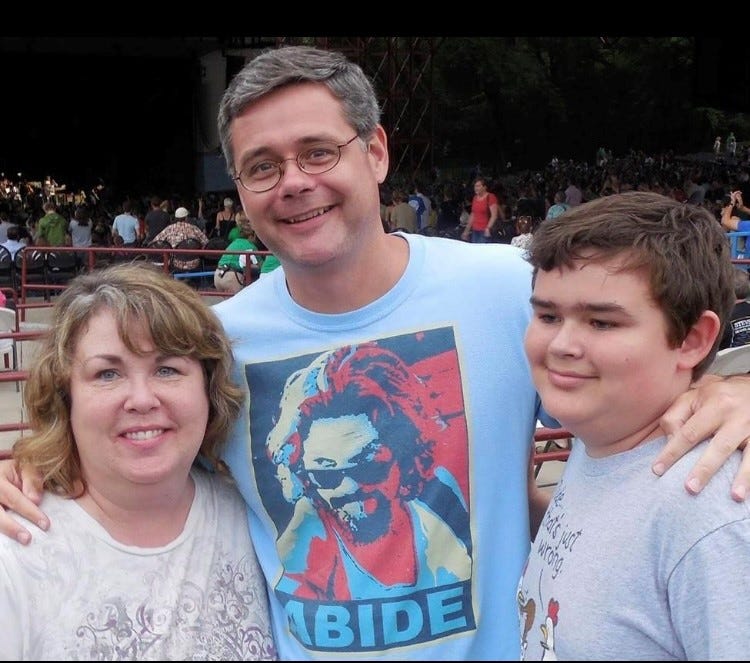

A hard rain fell all day on July 6, 2013, and the forecast was for it to continue through the night. Not a good omen for the very first Dylan concert I planned to attend with my wife Cathy and our 12-year-old son Dylan, named after you know who.

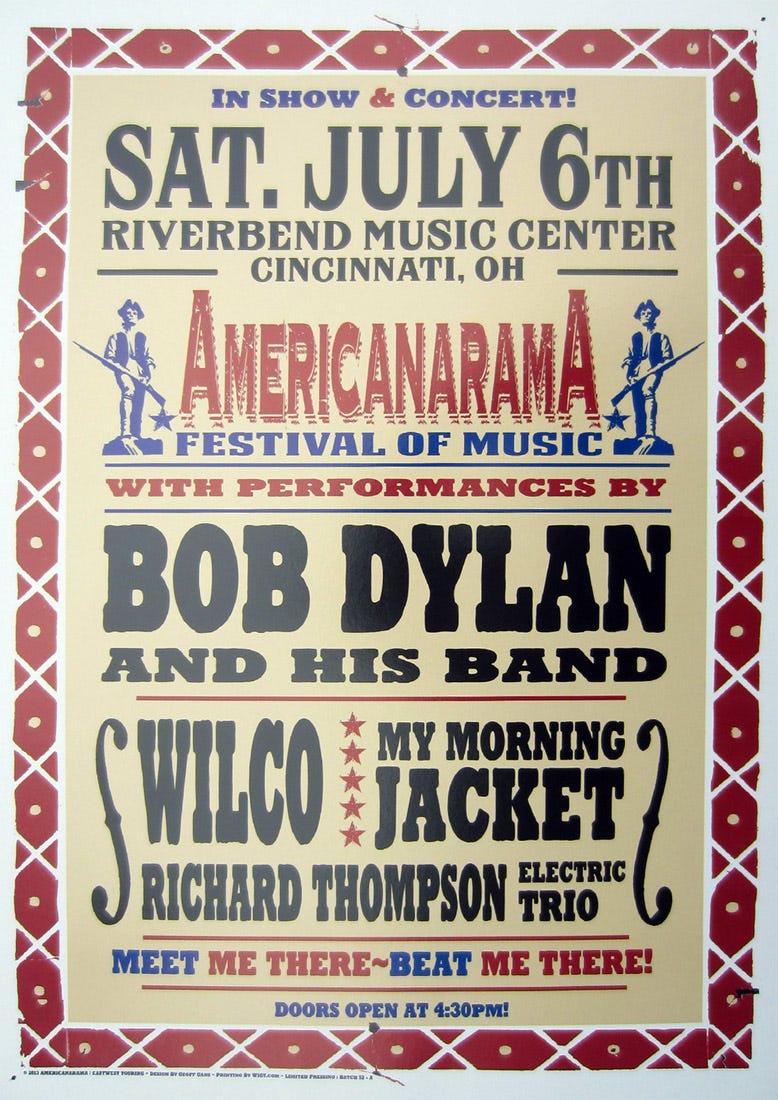

I wished I had shelled out the extra bucks for a comfy seat under the roof rather than a beach blanket on the soggy lawn at Riverbend Music Center. But instead I invested in three ponchos and, after waiting out a late afternoon downpour, we made our way to the venue. We missed the first (of three) opening acts—sorry Richard Thompson—but by the time we claimed our patch of grass (actually artificial turf), the skies had cleared. It turned into a lovely evening and one of the most special Dylan concerts I ever attended.

Dylan Context

The biggest development in Dylan world between his 2012 concert at PNC Pavilion and his return the following summer was the release of Tempest in September 2012. Even before it hit record stores and streaming services, the title prompted a flurry of speculation from Dylanologists that, like Shakespeare’s last play (sort of) by the same title (almost), this would be Dylan’s last album. Well, we got that wrong.

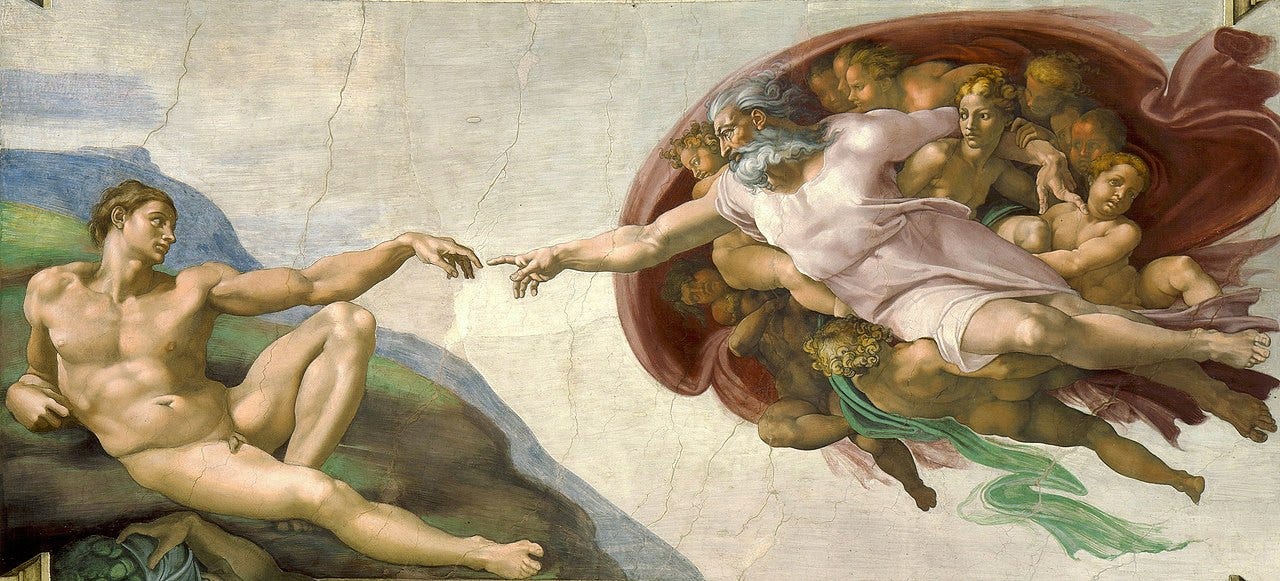

According to Ian Bell, “Tempest is one of the finest things he has ever done,” going so far (too far) to call it Dylan’s best album since Blonde on Blonde (520). In searching for worthy peers, Bell compares Tempest to “Picasso in his final years of raging turmoil, remaking Old Masters obsessively, mocking death, locked in a futile combat with age and libido” (520). Inevitably, late Shakespeare gets drafted into service, too: “In these songs the skies darken and the corpses pile up thanks to betrayal, fate, or because the artist is offering to do the job himself. Those who chose to see Dylan as Shakespeare’s Prospero got the wrong character. Lear would have been a better fit” (Bell 520).

Tempest is a strong batch of songs lyrically and musically, but Dylan’s vocals are as rough as they’ve ever been on any recording. I agree with Matthew Ingate, who points to much better performances of the songs in concert. He attended a 2013 show at the Royal Albert Hall where Tempest material featured prominently. “It is on the stage that Tempest is coming to life. The songs have a much greater looseness, spontaneity and a freedom to them now, compared to on the record” (Ingate 21). Riverbend ’13 lends further evidence to support this claim.

Dylan remained committed to delivering his songs live and in person through the Never Ending Tour, which passed the 2,500th concert milestone in the spring of 2013. Following a stint away from the band, Charlie Sexton rejoined the lineup on July 2nd in Memphis. He plugged the hole left by the abrupt and acrimonious departure of guitarist Duke Robillard. The Cincinnati show was only Charlie’s fourth gig back in the NET fold.

“Sexton”: that’s the word for someone who looks after a church, a sort of caretaker. The aptly named guitarist helped put Dylan’s house back in order. Sexton transitioned into the ensemble so seamlessly that you’d think he never left.

One thing that distinguishes the later NET from the early years is the relatively stable setlists. For a long time, you truly weren’t sure what you were going to hear Dylan play from one show to the next. By 2013, however, he trotted out the same songs in the same order most nights. Case in point: the Cincinnati setlist was exactly the same as his previous night in Noblesville, Indiana, and the show before that in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, and the one before that in Memphis, Tennessee. The wheels on the tour bus go round and round, but not the song selection. This pattern became so predictable that Clinton Heylin rechristened the NET as “the Never Changing Tour” beginning in 2013 (Double Life 726).

The biggest novelty of the year was the addition of several high-profile acts joining Dylan on the summer bill. Dubbed the “AmericanaramA Festival of Music Tour,” the bonanza included the Richard Thompson Electric Trio, My Morning Jacket, and Wilco, with our slugger batting cleanup. These were all heavy hitters accustomed to headlining their own shows. Their willingness to defer to the setup role testifies to their deep admiration for Dylan. Typically, I only make brief reference to the opening acts, but these guys deserve a bigger share of the spotlight.

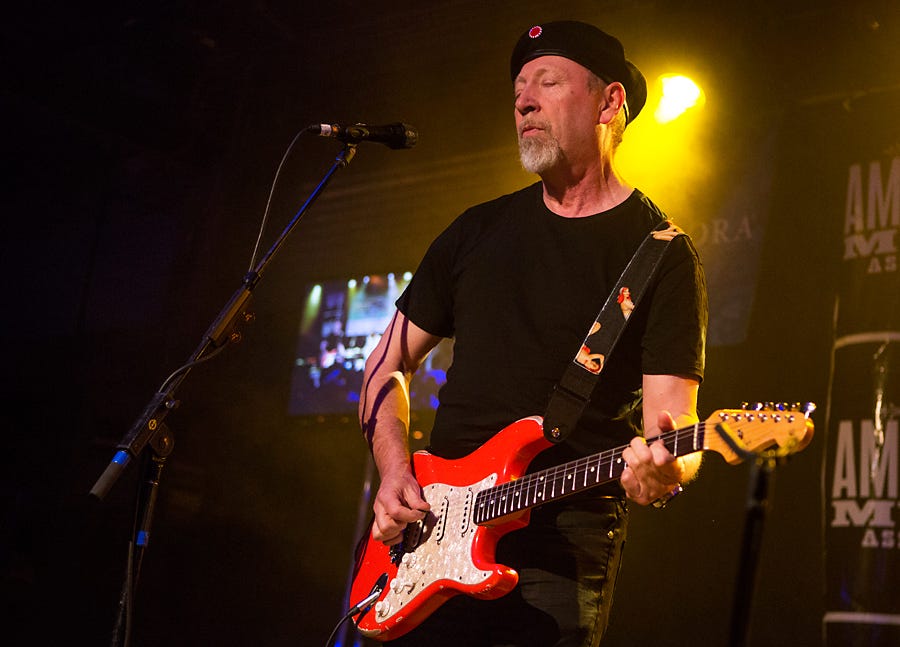

Richard Thompson has been covering Dylan songs since the sixties in his band Fairport Convention.

Thompson was honored by the invitation to join the AmericanaramA tour, and frankly grateful for the payday. He is rightly revered among folk aficionados, especially in the UK, but among American audiences he was the least well-known of the four groups on the bill. Therefore, he was assigned the unenviable task of running the first leg of a 5 ½ hour relay. He told Ray Padgett, “The only downside for us was we were basically opening the show, usually something like 5:30 p.m., when there were about 500 people in the arena. People slowly trickled in during our set. So our sets were a bit throwaway in that sense. But we had some fun. We did a lot of jamming with Wilco, who like that sort of thing.”

As I mentioned earlier, a rain delay forced me to miss Thompson’s opening set entirely. Luckily, I got to see him perform a couple songs with Wilco. He accompanied them on the sublime “California Stars,” penned by Woody Guthrie, and on “Sloth” by Fairport Convention.

I wish I could have been at the show in Clarkston, Michigan, eight days later to witness Dylan cover Thompson’s brilliant song “1952 Vincent Black Lightning.” Thompson wishes he could have been there, too. He was given no advance notice this was going to happen, so he had already hit the road for the next gig in Toronto. Ray asked Thompson about his reaction: “I think I read it on Facebook. Someone commented about it. I thought, ‘Well, I don’t really believe that. Why would Bob cover one of mine?’ When it sank in, I thought, ‘Well, that’s fantastic. I’ve covered 75 of his; he’s covered one of mine.’ I think that that’s the right ratio.”

Thompson never appeared onstage with Dylan during this tour, but he did have one offstage encounter. He told Ray, “Towards the end of the tour, I met Bob. He invited me to his bus, and that was very nice. He was very gracious and friendly. He said he was appreciative of the stuff Fairport had done with his songs. That was lovely.”

Jim James is frontman for My Morning Jacket. He is also a huge Dylan fan. He contributed a fantastic “Goin’ to Acapulco” with Calexico for Todd Haynes’s film I’m Not There. In 2014, he was selected by producer T Bone Burnett for the all-star team The New Basement Tapes. This project created and recorded new songs using abandoned Dylan lyrics from the Basement Tapes period. There’s an excellent film by Sam Jones documenting the project called Lost Songs: The Basement Tapes Continued.

James was stoked to join Dylan on tour, but it didn’t turn out the way he expected. He told Andy Greene of Rolling Stone: “The whole concept of the tour was supposed to be super collaborative. We were expecting to be sitting around the campfire with Dylan at two a.m. and go, ‘Let’s cover all of Desire tomorrow!’ We had all these pipe dreams.” James made little effort to conceal his disappointment: “Bob really wasn’t around. We never talked to him once. He does not hang, which is fine and understandable . . . or it’s kind of understandable. I don’t know.”

My Morning Jacket put on the most energetic set of the night at Riverbend ’13. The band hails from Louisville, less than two hours southwest of Cincinnati, so lots of rambunctious supporters made the trip up for the show. One of the highlights was when Wilco joined MMJ for an awesome cover of George Harrison’s “Isn’t It a Pity.” None of the other performers joined Dylan during his set in Cincinnati, nor vice versa, but this wasn’t always the case later in the tour. Further down the road, James and Jeff Tweedy joined Dylan on “Twelve Gates to the City,” “Let Your Light Shine on Me,” and “The Weight.” But Dylan wasn’t in the hangin’ and jammin’ mood yet at Riverbend.

You probably know Jeff Tweedy first for his early work with Jay Farrar on Uncle Tupelo and his phenomenal later work with Wilco.

As he reveals in his book Let’s Go (So We Can Get Back): Memoir of Recording and Discording with Wilco, Etc., Tweedy has turned to Dylan’s music at pivotal moments in his life. For instance, he sang “Forever Young” at his son Spencer’s bar mitzvah (231). He and sons Sammy and Spencer also sang “I Shall Be Released” at Jeff’s father’s deathbed minutes before the man died (249).

It’s interesting to contrast James and Tweedy’s respective reactions to Dylan’s aloofness. While James was clearly bummed that he didn’t get to socialize with the maestro, Tweedy admired Dylan’s focus on performing his songs rather than entertaining the entourage. Asked about his relationship with Dylan by Patrick Doyle of Rolling Stone, he replied,

We’ve talked a little bit, and I actually get a really warm feeling from him. I felt very inspired just being in the presence of somebody that has that few fucks to give about anything. There’s a lot of middle ground there between somebody like Bob Dylan and Paul McCartney, who totally gives it up every night for the people and the songs. But if I had to choose one to be more inspired by, it’s definitely on the more curmudgeonly asshole side of the spectrum.

Doyle countered that it could be frustrating to catch Dylan on an off night, but Tweedy wasn’t taking the bait:

I would think that he would think that you’re just frustrating [laughs]. It’s really what you bring to it—you’re bringing all of his other records and what you want him to do, and he’s bringing his passion for jump blues right now. He’s bringing his newest sets of fucking impeccably crafted lyrics, which are really astonishing. I don’t think people appreciate it, you know? He’s just curious. He’s just really still pushing and curious and, you know, people mistake [that] for phoning in and being withholding. I think it’s just the way he’s lived.

Jeff Tweedy gets it.

He was initially invited to take part in the New Basement Tapes but had to pull out after his wife became very ill. He told readers in a 2023 post to his Substack site Starship Casual: “I have a whole album of Dylan lyrics set to my tunes that might never come out.” Don’t hide them in your basement—release the tapes! I’ll give you the title for free: Tweedy & the Monkey Man.

In that same Starship Casual post, he shared a hybrid byproduct from the Dylan project, a lovely song called “White Wooden Cross.” He explained that “the music here was originally written to support one of the Dylan pages. But the words you’ll hear are mine. At some point I just liked the tune and was bummed I didn’t get to share it anywhere, so I wrote some new words. And to add yet another layer of cannibalistic song craft, most of these words were recast against different music on Ode to Joy.”

In his memoir, Tweedy vividly remembers his first encounter with the legend during the 2013 tour. Dylan casually acknowledged Tweedy one night on his way to the stage:

As they got to our door, I heard what sounded like a Bob Dylan impression: ‘Hey, Jeff, how’s it going, man? Good to see you!’ Bob had spoken to me. Without breaking stride. And I was left in his wake trying to play it cool, but I could feel all of the other folks around us looking at me. It was impossible to play it cool. ‘Dylan talked to me. Did you guys see that?!’ I immediately undid any credibility I had just accrued by being visibly rattled. I had to sit down. Later, when I had collected myself, I called Susie [his wife] to let her know Bob and I were already best friends. (263-64)

The real icebreaker came through their mutual acquaintance with Mavis Staples. Tweedy is very good friends with Staples, having collaborated with her several times and produced some of her recordings.

During the 2013 tour, he carried Cupid’s quiver back and forth between Bob and Mavis, who famously turned down his marriage proposal back in the early sixties. Tweedy recalls,

One of my other interactions on tour with Dylan had been him telling me to ‘Tell Mavis she should have married me!’ I told him I would, so I relayed the message to her and she asked me to remind him that she’s still available. When I saw him stage-side the next night, I told him what Mavis had said, and he laughed and said, ‘Yeah? I wish!’ Being a literal go-between in a playfully flirtatious conversation between Mavis and Bobby is probably the pinnacle of my career. I should probably hang it up. It’s not going to get better than that. (Let’s Go 265)

The Concert

When: July 6, 2013

Where: Riverbend Music Center in Anderson Township

Openers: The Richard Thompson Electric Trio, My Morning Jacket, and Wilco

Band: Bob Dylan (vocals, harmonica, guitar, and piano/keyboard); Tony Garnier (bass); Donnie Herron (violin, mandolin, banjo, and steel guitar); Stu Kimball (guitar); George Receli (drums and percussion); Charlie Sexton (guitar)

Setlist:

1. “Things Have Changed”

2. “Love Sick”

3. “High Water (for Charley Patton)”

4. “Soon after Midnight”

5. “Early Roman Kings”

6. “Tangled Up in Blue”

7. “Duquesne Whistle”

8. “She Belongs to Me”

9. “Beyond Here Lies Nothin’”

10. “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall”

11. “Blind Willie McTell”

12. “Simple Twist of Fate”

13. “Summer Days”

14. “All Along the Watchtower”

*

15. “Ballad of a Thin Man”

“Things Have Changed”

Dylan’s set begins with an ideal opener, “Things Have Changed.” He puts the audience on notice, effectively announcing this will not be some nostalgic golden-oldies hit parade. Things have changed. I love the jab, or maybe it’s just gentle ribbing, at whatever town he’s playing in that night: “This place ain’t doing me any good / I’m in the wrong town, I should be in Hollywood.” Say it ain’t so, Bob! There’s nowhere else you belong tonight but Cincinnati.

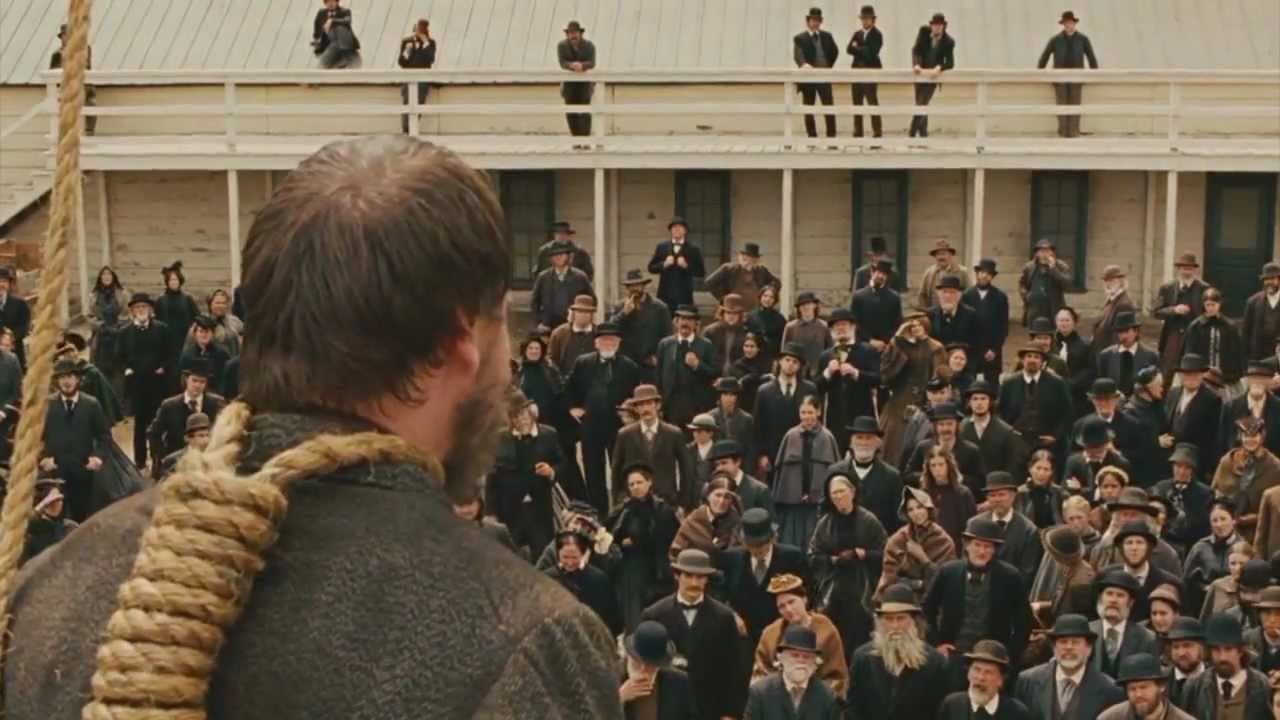

I really dig the guitar intro before Dylan walks onstage. It sounds like something from a spaghetti Western, the prelude heralding the arrival of a mysterious gunslinger. When the band launches into its hard-charging musical arrangement, you can practically hear the galloping hoofbeats of the posse in hot pursuit.

There’s an outlaw theme in tonight’s setlist, and it’s established from the very first song. The singer is a gun-for-hire—or maybe he just plays one in the movies—and he’s finally come to the end of his rope: “Got white skin, got assassin’s eyes”; “Standing on the gallows with my head in the noose / Any minute now I’m expecting all hell to break loose.” You can practically see the scene as it would unfold on the big screen, with the killer being led up the scaffold steps to face the townspeople before meeting his maker. Or you can just look at the haggard old desperado on stage at Riverbend.

The gallows have always served a performative function. Yes, as a practical matter, the scaffold is elevated to accommodate the hanged person’s fall. But it’s also raised to afford a better view for the audience, assembled to participate in the spectacle of public execution (cf. “They’re selling postcards of the hanging”). No one needs to educate Bob Dylan about the ways in which a stage can feel like a scaffold, a site where the condemned man stands before an unruly crowd and is punished for his crimes. He has long identified with outlaws in his songs, and he knows all too well how it feels to be publicly rebuked by audiences as if they were his judge, jury, and executioner. He foregrounds the outlaw theme in “Things Have Changed,” setting the stage for shady characters doing dirty deeds in other songs to follow.

“Love Sick”

The anonymous taper for this show states that he was located in Section 200, Row I, just right of centerstage. Take note, future Riverbend bootleggers, because this is where you want to be. The pristine quality of this recording is showcased on the second song, “Love Sick.”

This song fits perfectly within Dylan’s late-career vocal range. His mike is turned way up in the mix, a wise decision for “Love Sick,” allowing him to sing low without being drowned out by the music. And what he has to say is all brooding menace. “Love Sick” is the first song on Time Out of Mind, an album deeply influenced by the murder ballad tradition. From the start, Dylan presents us with a psycho issuing threats under his breath. Woe to the woman being pursued by this jilted lover, stalking her through streets that are dead with blood in his eyes.

There’s a recurring guitar figure I find really evocative in this performance. It sounds to me like a clock chime. The subliminal effect is to mark the relentless passage of time. It reminds me of the prison speech from the deposed, incarcerated, and soon to be assassinated king in Shakespeare’s Richard II:

[…] Music do I hear?

Ha, ha, keep time! How sour sweet music is

When time is broke and no proportion kept!

So is it in the music of men’s lives. […]

I wasted time, and now doth Time waste me. (5.5.41-44, 49)

“High Water (For Charley Patton)”

Riverbend Music Center is named for its location at a bend in the Ohio River. The stage sits remarkably (hazardously?) close to the river.

When and where a performance takes place matters. Dylan sings from a stage erected on a flood plain that has been engulfed countless times by the same “high water” described in the song. Sure, “High Water” was a regular part of Dylan’s setlist at every stop on the summer tour. But it floats differently here. The strong brown god lurks right behind the stage, rising after a day of torrential rain, exerting a palpable presence, reminding everyone who’s boss.

Donnie Herron’s plucky banjo transports us down south and back in time, and Dylan’s vocals are alert and nimble, like he’s kayaking the rapids of this rushing river of sound.

“Love and Theft” is probably still the high-water mark of Dylan’s 21st century albums, though Rough and Rowdy Ways crested at similar heights two decades later. All of the L&T songs are densely packed with borrowings from an eclectic range of sources, none more so than “High Water (For Charley Patton).” Dylan piles up lyrical fragments like he’s stacking sandbags, trying in vain to fend off the flood.

Clinton Heylin spots allusions to Patton’s own “High Water Everywhere,” Clarence Ashley’s “The Coo Coo Bird,” Big Joe Turner’s Kansas City Here I Come, Wilbert Harrison’s “Kansas City,” Robert Johnson’s “I Believe I’ll Dust My Broom,” James Carter’s “Po’ Lazarus,” and the traditional “The Bald Headed End of a Broom” (Still on the Road 460-62). Scott Warmuth digs even deeper to uncover references to Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre, Daniel Decatur Emmett’s “De Boatman’s Dance,” Louis-Ferdinand Céline’s Castle to Castle, and Henry Rollins’s Now Watch Him Die and Art to Choke Hearts & Pissing in the Gene Pool.

Each verse provides a snapshot of desperation, featuring characters on the point of drowning, losing their livelihood and worldly possessions, barely keeping their heads above the rising tide of disaster.

In live performance, however, it’s easy to lose sight of the dire and dispossessed while bobbing on the sparkling waves of such buoyant music. The band does this cool thing at the end, after Dylan’s last verse, where they wind up and slow down like the song is finished—only to speed up and ride the rapids a little farther downstream. Then they do the same thing again, another fake-out, before finally ending for real. Translating this into the flood language of the song, it feels like they’re simulating the fits and starts of navigating a raging river, grasping at rocks and branches, getting snagged amid debris, then hurtling back into the fray.

“Soon After Midnight”

The fourth song is the first selection from Tempest. “Soon After Midnight” sounds so sweet, a melodic love ballad that reminds me of Floyd Cramer’s “Last Date.” Dylan sings,

I’m searching for phrases

To sing your praises

I’ve got to tell someone

It’s soon after midnight

And my day has just begun

Gee whiz, what a dreamboat, right? But pay close attention to the lyrics and you’ll find that the words gradually part ways with the music. Over the course of the song, the singer transitions from cajoling to intimidating, from heartwarming to bloodcurdling.

Ever since Dylan renewed his interest in the murder ballad tradition on Good as I Been to You and World Gone Wrong, he has included at least one murder ballad on every original album. You can usually spot it immediately because it sounds like an endearing moonlight serenade. But trust me: you do not want to be within reach of this singer under cloak of darkness.

The character Dylan inhabits in “Soon After Midnight” sounds like a pimp or a stalker, think Jack the Ripper or Mack the Knife, plucking fallen women like rose petals:

Charlotte’s a harlot

Dresses in scarlet

Mary dresses in green

It’s soon after midnight

And I’ve got a date with a fairy queen

He’s a patient stalker, a Big Bad Wolf on the hunt for his next Little Red Riding Hood: “I’m in no great hurry / I’m not afraid of your fury / I’ve faced stronger walls than yours.” The singer is willing to use violence to get what he wants and has done so before. “I been down on the killing floors,” he informs her, and he knows how to conduct business there:

They chirp and they chatter

What does it matter?

They’re lying there

Dying in their blood

Two Timing Slim

Who’s ever heard of him?

I’ll drag his corpse through the mud

No need the read between the lines with taunts so brazen. He has apparently been sizing up his latest victim for some time, and now he’s got her within his clutches:

It’s now or never

More than ever

When I met you

I didn’t think you would do

It’s soon after midnight

And I don’t want no one but you

“Last Date” indeed! Of all the silver-tongued devils in Dylan’s dramatis personae tonight, the sicko in “Soon After Midnight” is simultaneously the most seductive and the most savage.

“Early Roman Kings”

The next song from Tempest is “Early Roman Kings.” Dylan sure does love this song, having sung it in concert over 600 times, beginning in 2012 and extending through his most recent tour. One of his chief attractions is clearly the line “I ain’t dead yet! / My bell still rings!” which always sparks cheers from the audience.

Dylan is a walking, squawking encyclopedia of song, but his repertoire also includes literary, mythical, historical, and theological sources of inspiration. In a 2015 interview for AARP Magazine, Robert Love asked Dylan what he would have done had he not become a musician. “If I had to do it all over again,” he reflected, “I’d be a schoolteacher—probably teach Roman history or theology.”

In his book Why Bob Dylan Matters and his follow-up essay on Rough and Rowdy Ways for The Dylan Review, Richard Thomas makes an irrefutable case for the importance of classical antiquity in Dylan’s work, particularly from Time Out of Mind onward. The allusions are often carefully concealed, but “Early Roman Kings” airs its tunic openly. Wouldn’t you know, the song’s most explicit classical quotation isn’t actually Roman but Greek. In the penultimate verse, Dylan sings, “I’ll strip you of life, strip you of breath / Ship you down to the house of death” Thomas explains: “The singer utters the taunt the Greek hero hurls at the Cyclops he has just blinded in Book 9 of the Odyssey. ‘Here was my parting shot,’ Odysseus tells Alcinous: ‘Would to god I could strip you / of life and breath and ship you down to the House of Death’” (257).

I have to credit my friend and colleague Tom Strunk, a Classics professor at Xavier University, for first opening my eyes to this side of Dylan. In his 2009 article, “Achilles in the Alleyway: Bob Dylan and Classical Poetry and Myth,” Tom traces Dylan’s use of Catullus, Horace, Vergil, and Euripides in songs spanning his entire career up to the point. Interesting side note: while I was wandering around Riverbend between sets, I ran into Tom and his family staked out on their own patch of hillside.

I don’t think Dylan uses classical references to look smart or to flash his credentials as the Bard of Hibbing. I suspect he does it because he finds instructive analogies between the ancient and contemporary worlds. The same characters, events, follies, corruptions, and catastrophes can be found today, tomorrow, and yesterday, too. The songs from Tempest remind us—from the Odyssey to the Passion, from the sacking of Rome to the sinking of the Titanic to the shooting of John Lennon—that, when it comes to human nature, things haven’t changed all that much.

Did you know that there’s an important early Roman connection to Cincinnati? In 1788, settlers established a town they called Losantiville in what is today Cincinnati. Fort Washington was built there in 1789, named after the recently inaugurated first President of the United States, George Washington. In 1790, the governor of the Northwest Territories, Arthur St. Clair, renamed the settlement Cincinnati after the Society of Cincinnati, a relief organization for Revolutionary War veterans and their families (St. Clair was president of the society). This group took its name from the Roman statesman, general, and farmer Cincinnatus [to be precise, Lucius Quinctius Cincinnatus (c. 519 – 430 BC)].

Cincinnatus was reluctantly lured out of retirement to lead the patrician army during a plebian revolt. After swiftly putting down the rebellion and securing the republic, he voluntarily resigned and returned to farming. This act is represented in the statue above by Cincinnatus holding the fasces of power in one hand and a ploughshare in the other. He was cited by President Washington as the perfect combination of civic leadership and personal humility. Washington followed this example, retiring after two terms and returning to his farm in Virginia.

I’m not suggesting that Dylan had Cincinnatus in mind for his song, which is populated by caricatures of decadence, both ancient and contemporary. Nevertheless, considering his passion for both the classics and American history, I bet Dylan would appreciate the Queen City’s cultural inheritance from this early Roman king.

“She Belongs to Me”

Simply beautiful. That was my reaction when I heard Dylan sing “She Belongs to Me” live at Riverbend ’13, and I felt the same way the first time I listened to the bootleg recording. Dylan gives a sensitive vocal interpretation of this love ballad from Bringing It All Back Home (1965), punctuated by some gorgeous harmonica that is greeted warmly by my hometown crowd.

It’s worth noting that Dylan is more than halfway through the concert before playing his first song from the 1960s. He is often pigeonholed as a sixties icon by fans, or a sixties relic by detractors, much to his annoyance. He chafes against the yoke, but for many years he was also responsible for tightening the harness. The numbers don’t lie. Prior to 2013, Dylan had played 16 concerts in the Cincinnati area. In 15 of them (all but 2007 at Taft Theatre), he played more songs from the sixties than from any other decade. Is it any wonder he continued to be associated first and foremost with the sixties? Methinks the voice of his generation doth protest too much.

As he advanced deeper into the new century, however, and as he continued to produce vibrant songs with subject matter and vocal range better suited to an older artist, Dylan featured recent material more and more. 2013 is a good example. Only 4 of Dylan’s 15 songs this evening were born in the sixties; by comparison, 7 were conceived after the turn of the century.

Furthermore, as I’ve been at pains to show throughout this series, even when Dylan plays his familiar songs from days of yore, he defamiliarizes them and keeps them fresh with new musical arrangements and radically different vocal performances. I could just stay at home and listen to records if I were only interested in the songs as originally written and recorded. What makes Dylan in live performance so interesting is that, not only do you not know what you’re going to get, but you don’t know how you’re going to get it.

AmericanaramA tour mate Richard Thompson first made his mark in the sixties, too, and has remained consistently on the road ever since. He has some thoughtful reflections on how to stay connected with material written in one’s youth. In his 2021 memoir Beeswing: Losing My Way and Finding My Voice, 1967-1975, he muses,

To play a song like ‘Meet on the Ledge,’ written fifty years ago on my bed in my tiny room in Brent, for reasons I cannot remember, with a worldview that was understandably naïve, is curious. I am and I am not the same person. I have to forgive the author of the song for being youthful, but I salute some of his emotions he felt at the time, so I have to see what new emotions the song arouses in me, or I cannot sing it—music without emotion is a heinous crime, after all. So I restructure my approach to this piece, invest it with a layer of old man’s cod wisdom and weary insight, and it seems to work. (254-55)

My favorite part of that passage is “I have to see what new emotions the song arouses in me, or I cannot sing it—music without emotion is a heinous crime.” Take another listen to “She Belongs to Me,” considering its juxtaposition with other songs on the Riverbend ’13 setlist. My first reaction was “simply beautiful,” but now I’m not so sure. Music without emotion may be a heinous crime, but sometimes “old cod wisdom and weary insight” can make a straightforward love song start to sound like a crooked crime scene.

The singer is utterly captivated by an artist who has the power to alter reality, and not always for the better: “She can take the dark out of the nighttime / And paint the daytime black.” The Rolling Stones borrowed that image the following year in “Paint It Black.”

In “Paint It Black,” the singer hides his ominous intentions from the women he meets, but not from the listener: “I see the girls walk by / Dressed in their summer clothes / I have to turn my head until my darkness goes.” Was there always something sinister in the subtext of “She Belongs to Me,” too? The song’s placement alongside other creepy numbers in the Riverbend ’13 setlist draws its latent darkness to the surface.

A power struggle lies at the heart of “She Belongs to Me.” The mesmerizing woman inspires criminal behavior from her followers: “You will start out standing / Proud to steal her anything she sees.” Her lackeys end up on their knees, either in worship [“Bow down to her on Sunday”] or in frustrated desire [“But you will wind up peeking through a keyhole / Down upon your knees”]. And yet, paradoxically, the song’s title asserts possession and control: “She Belongs to Me.” Oh, does she? You could have fooled me. Most of the evidence points to her as the dominatrix and him as the submissive, her as the collector and him as the collected.

As with other songs from Riverbend ’13, we shouldn’t become so enamored by tender music and vocals that we ignore the ambivalence and animosity in the lyrics. The repressed resentment of “She Belongs to Me” sets up even more disturbing threats in the next song.

“Beyond Here Lies Nothin’”

The groove of “Beyond Here Lies Nothin’” is enticing, reminiscent of Santana’s “Black Magic Woman,” with lots of room for the guitarists to strut their stuff. The lyrics are sung by a Black Magic Man. This is another love ballad laced with hemlock.

My good friend Roberta Rakove focused on “Beyond Here Lies Nothin’” in an episode of the Freewheelin’ Rob Kelly’s Pod Dylan. She talked about the “ominous, possessive, dark feel” of the lyrics. As Roberta put it, the singer essentially says, “I can’t function without you. It has to be just you and me. And there isn’t anything else.” That’s how I hear it, too.

The singer declares in the first verse:

Well I love you pretty baby

You’re the only love I’ve ever known

Just as long as you stay with me

The whole world is my throne

Beyond here lies nothin’

Nothin’ we can call our own

In another context, this might sound harmless enough. However, when you put this guy in a lineup beside the other delinquents in the setlist, “Beyond Here Lies Nothin’” comes across as an ultimatum, suggesting the dire consequences if the woman ever tries to leave the singer.

“Beyond Here Lies Nothin’” is co-written with Grateful Dead lyricist Robert Hunter, and it’s the opening track of Together Through Life.

I can never hear this song without thinking of the album cover, featuring Bruce Davidson’s photo of lovers so entwined. Maybe that’s the “here” of the song—the backseat of this car, or the bed in a seedy motel, or the bathroom in an all-night diner, or the wall of a deserted back alley. Whenever and wherever these lovers wrap their bodies together is the only time and place that exists.

The singer sounds like a cousin of the creeper from “Soon after Midnight” when he sings:

I’m movin’ after midnight

Down boulevards of broken cars

Don’t know what I’d do without it

Without this love that we call ours

Beyond here lies nothin’

Nothin’ but the moon and stars

When he tells her “beyond here lies nothin’,” he is essentially declaring “she belongs to me.”

Once you’ve seen the ultraviolent psychosexual video directed by Nash Edgerton, it will permanently impact how you hear the song.

As you can see for yourself, it is severely twisted, involving abduction, punching, stabbing, and hit-and-run. The woman is tied up as a hostage at the beginning of the video, but by the end she manages to escape, only to madly return to him in the end. The video concludes with the two codependent sadomasochists locked in a kiss. Pretty messed up.

According to Richard Thomas, the song’s title comes from Tristia, the Augustan poet Ovid’s poems written during his exile from Rome. In Tristia 2.195-96, the poet claims, “beyond here lies nothing but chilliness, hostility, frozen / waves of an ice-hard sea” (Thomas 241). The sailing ships in the harbor in the final verse fit with this older setting. Maybe Dylan was already thinking ahead to (The) Tempest and the island exile of Prospero and Miranda. Forget Milan: beyond here lies nothing. While we’re on this path, I also get an Antony and Cleopatra vibe from the song. When Antony is offered news from home in the first scene, he has no interest. He only cares about being with Cleopatra: “Let Rome in Tiber melt, and the wide arch / Of the ranged empire fall! Here is my space!” (1.1.34-35).

Forget Rome: beyond here lies nothing. Cleopatra is Antony’s only queen, and her bed is his only throne. Needless to say, they end up loving each other to death. One assumes the same fate awaits Dylan’s couple in “Beyond Here Lies Nothin’.”

“A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall”

After leading a dubious cast of characters across the stage of his Cincinnati gallows, Dylan makes a very different journey with the next song, ascending the mountaintop for his most touching performance of the night, the sixties anthem “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall.” This song made the biggest impression on me in 2013, and its impact has only deepened with time.

“Hard Rain” is framed as a conversation with Dylan singing both parts. “Oh, where have you been, my blue-eyed son? / And where have you been, my darling young one?” asks the parent. The child answers with a series of dreams or visions, cataloguing the wreckage of a world gone wrong and sounding the alarm about a gathering storm. “Hard Rain” is Dylan’s first apocalyptic song and probably still his best, warning about a cataclysmic reckoning, looming on the horizon and headed straight for us.

The prophetic child gets most of the lines, but on this particular night I found myself identifying more with the parent. The last time Dylan played “Hard Rain” in Cincinnati was at this same venue in 2000. In my chapter on that concert, I mentioned that this was the same year that Dylan lost his mother. In attendance that night was Patti Smith, with her son Jackson, in the same year that she lost her father. My son Dylan was also born in 2000. Now here I stood beside him in 2013, listening to his namesake perform this song to us. The parent-child connection was tugging at my heartstrings on the hillside of Riverbend that night.

I also thought back to the first time I saw Bob Dylan in concert, at Nashville’s Starwood Amphitheatre in 1989, on a stormy night that scared droves of ticketholders away. The ushers took pity on us grass-passers and let us sit in the empty seats under the roof. In retrospect I see it as the first act of generosity from a man who has given me so much that I named my kid after him. So many layers of time piled up in the strata of this mighty mountain of a song.

The sense of scaling a mountain is replicated sonically in the Riverbend ’13 arrangement of “Hard Rain.”

Listen to the interplay of Dylan’s voice with the music in the final verse of the song. He doesn’t have the volume or range he once had, and he was never Celine Dion to begin with. But he grasps each line he can still reach and hoists himself upward, climbing the musical scale like Moses up Mount Sinai—or, if you prefer, like a nimble old billy goat whose bell still rings.

And I’ll tell it

And think it

And speak it

And breathe it!

And reflect it

From the mountain

So all souls

Can see it!

The child of the song grows into a man right before our eyes.

At the same time, the blue-eyed septuagenarian on stage stretches across time and reconnects with the brash youngster who first delivered the song in 1963. Fifty years later, it also felt like old Dylan was reaching across the footlights, into the Cincinnati night and up the hillside, to connect with the hazel-eyed boy by my side at his first Dylan concert.

The thing about it is that there is the old and the new, and you have to connect with them both. The old goes out and the new comes in, but there is no sharp borderline. The old is still happening while the new enters the scene, sometimes unnoticed. The new is overlapping at the same time the old is weakening its hold. It goes on and on like that. Forever through the centuries.

--Bob Dylan to Mikal Gilmore in 2012

Works Cited

Bell, Ian. Time Out of Mind: The Lives of Bob Dylan. Pegasus Books, 2014.

Bootleg audio recording (LB-10894). Taper unknown. Riverbend Music Center, Cincinnati (6 July 2013).

Doyle, Patrick. “Jeff Tweedy on ‘Star Wars,’ Bob Dylan and Wilco’s Next LP.” Rolling Stone (19 August 2015), https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-news/jeff-tweedy-on-star-wars-bob-dylan-and-wilcos-next-lp-51978/.

Dylan, Bob. Official Song Lyrics. The Official Website of Bob Dylan.

https://www.bobdylan.com/.

Gilmore, Mikal. “Bob Dylan Unleashed.” Rolling Stone (27 September 2012). https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-news/bob-dylan-unleashed-189723/.

Greene, Andy. “Jim James on Touring with Bob Dylan: ‘He Does Not Hang.’” Rolling Stone (1 November 2013), https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-news/jim-james-on-touring-with-bob-dylan-he-does-not-hang-55679/.

Heylin, Clinton. The Double Life of Bob Dylan: Far Away from Myself, Vol. 2, 1966-2021. The Bodley Head, 2023.

---. Still on the Road: The Songs of Bob Dylan, Vol. 2: 1974-2008. Constable, 2010.

Ingate, Matthew. Together through Life: My Never Ending Tour with Bob Dylan. Troubador, 2022.

Kelly, Rob. “Pod Dylan #251: ‘Beyond Here Lies Nothin’ with Roberta Rakove.” Pod Dylan (11 March 2023), https://pod-dylan.castos.com/episodes/pod-dylan-251-beyond-here-lies-nothin.

Padgett, Ray. “Richard Thompson Recalls Bob Dylan Covering ‘1952 Vincent Black Lightning’—Ten Years Ago Today.” Flagging Down the Double E’s (14 July 2023),

.

The Rolling Stones. “Paint It Black.” Aftermath. London Records, 1966.

Shakespeare, William. Antony and Cleopatra. Ed. John Wilder. Arden Shakespeare Third Series. Bloomsbury, 1995.

---. King Richard II. Ed. Charles R. Forker. Arden Shakespeare Third Series. Bloomsbury, 2002.

Strunk, Thomas E. “Achilles in the Alleyway: Bob Dylan and Classical Poetry and Myth.” Arion: A Journal of Humanities and the Classics 17.1 (2009): 119-36.

Thomas, Richard F. Why Bob Dylan Matters. Dey St., 2017.

Thompson, Richard, with Scott Timberg. Beeswing: Losing My Way and Finding My Voice, 1967-1975. Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill, 2021.

Tweedy, Jeff. Let’s Go (So We Can Get Back): Memoir of Recording and Discording with Wilco, Etc. Dutton, 2018.

---. “White Wooden Cross (Demo).” Starship Casual (9 March 2023),

.

Warmuth, Scott. “Bob Dylan and High Water (For Henry Rollins).” Goon Talk (11 April 2011), https://swarmuth.blogspot.com/2011/04/bob-dylan-and-high-water-for-henry.html?q=high+water.

Graley I really loved this and thanks for the shoutout. I am all in on the Cincinnati series. There’s something fascinating about putting a geographic frame around a series of concerts and it makes me want to think back to our own Chicago experiences with this approach. I love the train wreck of Bob’s voice in this period and hearing it on Lovesick in particular was so good - a perfect fit for the song.

Beautiful essay. I could not make any of these shows for reasons big and small, and it was a real bummer at the time and certainly since then. These cuts sound great!